#Bernard Malamud

Photo

#my photo#books#book#bookshelf#decor#reader#read#John D. MacDonald#Charles McKay#Gregory Macguire#Bernard Malamud#photography#s20#photographers on tumblr

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Natural (1984). A middle-aged unknown comes seemingly out of nowhere to become a legendary baseball player with almost supernatural talent.

More than anything, this movie is just kind of silly. It lacks narrative tension, is overly long, and doesn't work as an underdog story given his obstacles are entirely external to him. He never really fails - rather just has opportunity taken away from him - and that makes it not really for me. Still, Robert Redford is always watchable, and Glen Close is always welcome. 4/10.

#the natural#1984#Oscars 57#Nom: Supporting Actress#Nom: Score#Nom: Art Direction#Nom: Cinematography#barry levinson#Bernard Malamud#roger towne#Phil Dusenberry#robert redford#glenn close#robert duvall#kim basinger#1910s#1930s#sports#america#american

5 notes

·

View notes

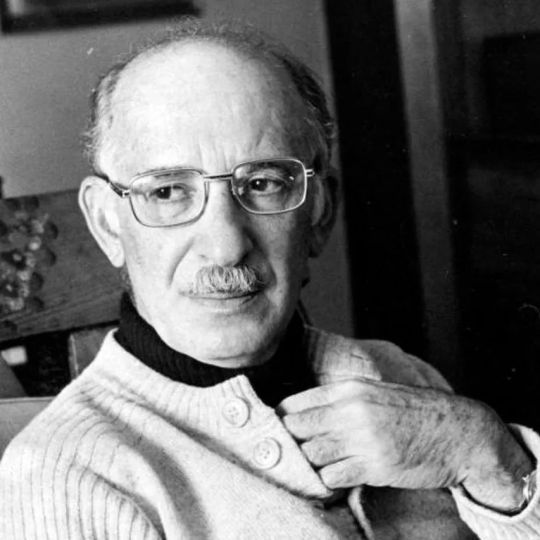

Photo

On This Day in New York City History March 18, 1986: Brooklyn born Jewish American author and educator Bernard Malamud (April 26, 1914 – March 18, 1986) passes away at the age of 71.

Malamud was the author of such works as the Fixer (Pulitzer and National Book Award for Fiction winner,) the Assistant, the Magic Barrel and arguably his most famous work the Natural. The Natural tells the tale of former standout and aging ballplayer Roy Hobbs, which was adapted to the screen starring Robert Redford.

Malamud is considered to be among the best Jewish American authors of the 20th Century alongside such authors as Philip Roth, Saul Bellow and Joseph Heller.

#BernardMalamud #JewishAmericanHistory #TheNatural #TheFixer #TheMagicBarrel #NewYorkHistory #NYHistory #NYCHistory #BrooklynHistory #LiteraryHistory #Literature #History #Historia #Histoire #Geschichte #HistorySisco

https://www.instagram.com/p/Cp7nbI2uC9k/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#Bernard Malamud#Jewish American History#The Natural#The Fixer#The Magic Barrel#New York History#NY History#NYC history#Brooklyn History#Literary History#Literature#Books#Libros#Livres#History#Historia#Histoire#Geschichte#HistorySisco

0 notes

Link

Robert Redford é um prodigioso lançador de basebal, porém uma tentativa de assassinato atrasa a progressão da sua carrreira. Aparece já de meia idade numa equipa sem grandes ambições desportivas e entupida em esquemas de apostas. O treinador desconfia do reforço, devido à sua idade, e acaba por adiar a sua estreia para uma ocasião em que a equipa estava em queda, e o lançador se lesiona. Redford rapidamente abandona o papel anónimo, para se tornar o protagonista da equipa, e levar, por fim, a equipa à conquista. Uma relação amorosa perturba o seu desempenho, a presidência pede para ele deixar a equipa perder, e é uma amiga de infância que surge, e lhe dá alento para vencer.

0 notes

Text

Bernard Malamud: The Assistant (1957)

#Bernard Malamud#assistant#literature#time 100#inmigrant#jewish#grocery#jonathan rosen#brooklyn#farrar straus and giroux

1 note

·

View note

Note

Do you have any favorite books written by jews that you think are really cool/worth reccomending?

Just a few of my favourite off the top of my head, in no particular order:

"Up Up and Oy Vey" - by Simcha Weinstein. Non-fiction.

"Wrestling with God and Man"- by Rabbi Steven Greenberg. Non-fiction.

"The Red Tent"- by Anita Diamant. Biblical fiction.

"The Chosen"- by Chaim Potok. Novel.

"My Name is Asher Lev"- by Chaim Potok. Novel.

"The Secret Chord"- by Geraldine Brooks. Biblical fiction.

"Where the Wild Things Are"- by Maurice Sendak. Children's book. Holds a special place in my heart because my Grandmama used to read it to me all the time as a kid and she would do different voices for the different characters and it always makes me think of her.

"Man's Search for Meaning"- by Viktor Frankl. Memoir.

"The Fixer"- by Bernard Malamud. Novel.

"Ecclesiastes"- by King Solomon. Book in the Tanakh.

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ever-talking double of the Rothian pantheon is a Jew. Jewish talkiness may be an artifact of theology (arguing with God), an effect of history (wheedling with Cossacks), a residue of Talmudic practice, or the product of psychoanalysis (“say everything”). Whatever the source, there is “inside each Jew,” as one character puts it in Operation Shylock, “so many speakers! Shut up one and the other talks.”

The irrepressible talker is mobilized by Roth against any notion of Jewish wholeness or authenticity, of being oneself, at home in the world. The authentic Jew is the fantasy of the Zionist and the anti-Semite alike. Both get a platform in the “Judea” and “Christendom” chapters of The Counterlife, in which they reduce the Jew to a singular, univocal self. Purged of ambiguity and uncertainty, that Jew has only one destiny: to vacate his diasporic premises and go back to where he belongs, the land of his ancestors, where he will stop talking so much, or at least in so many voices.

Roth’s defense of the double against Jewish reductionism and Zionist certainty is also, in a way, the upshot of Arendt’s strictures about the doubling of the self. The fact that “I am inevitably two-in-one,” she writes, “is the reason why the fashionable search for identity is futile and our modern identity crisis could be resolved only by losing consciousness.” The search for a grounding identity—Jewish or otherwise—necessarily finds its terminus in the stasis of a unified self, unable to carry on a conversation even with itself. Down such a path, she suggests, lies death. [...]

Roth and Arendt turn the double into a figure of satire and irony, using its destabilizing comedy to deprive that house of its foundations. Roth’s most fanciful double is Anne Frank. In The Ghost Writer, the young Nathan Zuckerman, like the young Roth, has written a story that earns him the accusation of being a self-hating Jew. His accusers include his parents and Judge Wapter, a family friend and respected leader of Newark’s Jewish community. Desperate for exoneration, Nathan makes a pilgrimage to the home of an esteemed and elderly Jewish writer (modeled on Bernard Malamud) who lives in the Berkshires with his wife. There, Nathan meets the writer’s assistant, Amy Bellette. As the evening goes on, the form of Nathan’s redemption takes shape: Amy is really Anne Frank, and Nathan will marry her. What better guarantor of his Jewish credentials? He imagines returning to New Jersey and the conversation with his parents that will ensue:

“I met a marvelous young woman while I was up in New England. I love her and she loves me. We are going to be married.”

“Married? But so fast? Nathan, is she Jewish?”

“Yes, she is.”

“But who is she?”

“Anne Frank.”

According to Bailey, Roth originally wrote the Bellette character as if she were, in fact, Anne Frank. But that simple application of the reality principle prevented him from finishing the book. It was only when he realized that Bellette had to be a fantasy Anne Frank—a fictitious double, conjured from Nathan’s head—that Roth was able to find the comedy in, the meaning of, the story: how an agonistic writer could turn himself into a nice Jewish boy by marrying the nicest Jewish girl that ever lived, how the most sacred figure of the Holocaust—and the Holocaust itself—could be used to resolve the most profane family romance.

Corey Robin, "Arendt and Roth: An Uncanny Convergence"

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

A List Of Quotes I've Been Given During My Writing Classes That Make Writing Sound Like Psychological Warfare

A: Author Clarence B. Kelland was once asked how he had managed to write an estimated 10 million words in 61 years. He replied, “I get up in the morning, torture a typewriter until it screams, then stop.” On getting started, author Bernard Malamud remarked, “The idea is to get the pencil moving quickly.” Author P.G. Wodehouse said, “I just sit at the typewriter and curse a bit.”

B: “The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.”—Mark Twain

C: “Most days, writing simply requires work ethic, discipline, clarity, focus, time. Other days . . . it will demand absolutely everything of you.”—Christy Hall

D: Ernest Hemingway once remarked that he rewrote the beginning of his novel, The Sun Also Rises, 50 times. “What were you trying to get right?” his interviewer asked. Hemingway shook his head. “Just the words,” he said. “Just the words.”

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everyday Poetry - “If your train’s on the wrong track, every station you come to is the wrong station.” Bernard Malamud

#photography#photographers on tumblr#original photography on tumblr#happiness#quotes#daily calm#art#living

36 notes

·

View notes

Quote

- In un paese malato ogni passo verso la guarigione è un insulto per quelli che campano della sua malattia.

Bernard Malamud, L'uomo di Kiev

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

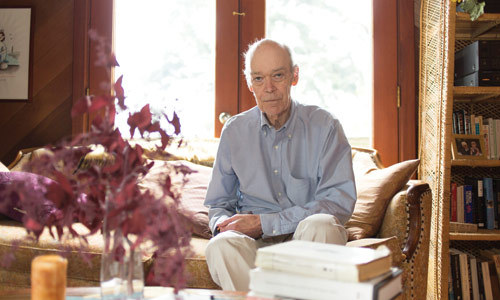

Although he was acclaimed as a travel writer, Jonathan Raban, who has died aged 80, disliked the term. He agreed with his fellow writer Bruce Chatwin, who famously turned down the Thomas Cook award, that the term was too limiting. He said he found it an “open form”, which was perfect for him because “I write between genres anyway”. When asked why, unlike Chatwin, he accepted the Cook award twice, he said: “I was hungry for prizes.”

He was also hungry to travel, to get away from his roots. The leaving of Britain formed a crucial part of much of his writing, even as he sailed around the island in Coasting (1986). The heart of his work was set on water; his writing mirrors the movement of the sea, its calm with turmoil always lurking beneath, taking you along with it, hiding and revealing. He mixes literary sources and knowledge with the people and places encountered on his journey; he’s less exotic than Chatwin, less caustic than Paul Theroux, but all of it comes in service to his real journey, within himself, escaping into travel. “Wherever I was, I felt like an outsider,” he said, and it is a feeling that permeates his writing, though he was drawn to America, a land of immigrants: the freedom of adjusting to this new world, and its contrasts with his old, became a major theme.

What he was escaping was the English world into which he was born, in Hempton, Norfolk. He was three when he first met his father, the Rev Canon J Peter CP Raban, an army captain returning from the second world war. He grew up in various parish postings, and his father came to represent “the Conservative party, the army, the church, the public school system in person”. It was his mother, Monica (nee Sandison), who “taught me to read, which was my one proficiency”.

He despised boarding school, to which he was sent at five, and eventually studied English at Hull University, where he organised a library committee in order to meet Philip Larkin, notoriously adept at avoiding students. They discussed novels and jazz, but never poetry. He married a fellow student, Bridget Johnson, in 1964. After graduating he taught English and American literature at Aberystwyth, then at East Anglia; he was captivated by American writers, particularly Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud and Philip Roth, and published a study of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn.

In 1969, he moved to London as a freelance writer, on the recommendation of Malcolm Bradbury, falling into the last hurrah of the Grub Street era, reviewing while living in the basement of the house shared by the poet Robert Lowell and the writer Lady Caroline Blackwood, after his marriage ended. His experience of Larkin and Lowell led to another book of literary criticism, The Society of the Poem. He joined the circle that emerged around the New Review magazine, in Soho’s Pillars of Hercules pub, and in 1974 published Soft City, a mix of personal memoir and London observation that became an early example of “psychogeography”.

His first travel book, Arabia Through the Looking Glass (1979), took a modern orientalist view of the area reminiscent of Charles Doughty’s Travels in Arabia Deserta and other classic travel writing on the Middle East. Old Glory (1981) was his first book set in the US, taking a skiff down the Mississippi River from Minneapolis to New Orleans. It recalls his study of Huckleberry Finn, blending the approaching age of Ronald Reagan into his inward experiences with America’s own eccentricities, and was a success on both sides of the Atlantic. Jan Morris called it “the best book of travel ever written by an Englishman about the United States”.

His first novel, Foreign Land (1985), follows an eccentric expat Englishman, George Grey, who leaves the Caribbean to return home, much to the consternation of his daughter, and sail a just-bought boat around Britain. Raban recapitulated the story himself in Coasting, in which he sails around the country, which, as the Falklands war erupts, seems an increasingly insular island nation. The book marks the perfecting of his classic English voice, that of the friendly faux-bumbler whose self-deprecation is itself a form of humble-brag, which has served British humour from Arthur Marshall to Bill Bryson; it made him a neutral sort of observer to Americans he met.

After publishing a memoir, For Love & Money: A Writing Life, he moved to the US, his journey across the Atlantic in a container ship told in Hunting Mister Heartbreak: A Discovery of America (1990), and, crucially, a poignant leaving scene that reflects the end of his second marriage, to the London art dealer Caroline Cuthbert.

He settled in Seattle, where in 1992 he married his third wife, Jean Lenihan; their daughter, Julia, was born in 1993. He continued travelling – Bad Land: An American Romance was set in Montana, dealing with the difficult dreams of immigrants to the beautiful but harsh Big Sky country. But his next book was perhaps his finest. Passage to Juneau (1996) is nominally another boat trip, on Alaska’s Inside Passage, a man leaving his wife and daughter for his travel. But midway through the trip, he returns to England, where his father is dying and his family has gathered. It is a travelogue of the writer’s mid-life implosion; he returns to finish his journey only to be greeted by his wife announcing she and his daughter are leaving him.

He remained in Seattle to concentrate on the joint care of his daughter. His 2003 novel, Waxwings, takes its butterfly title from Nabokov’s Pale Fire: “I was the shadow of the waxwing slain / By the false azure of the window pane.” Drawing on Bad Land, it is the story of an expat Hungarian-British man, in the dot.com boomtown that is Seattle, with an American wife, and an illegal Chinese immigrant worker who begins reconstructing his house. Raban was a distant relative of Evelyn Waugh, and the book recalls Waugh’s Men at Arms, where the social whirl does not stop for the newly launched war. My Holy War (2006), about the 9/11 attack and the US invasion of Iraq, was almost a companion piece.

In 2006 he published his third novel, Surveillance, in which a journalist tracks down a reclusive writer who has been kept hidden by his publisher lest he destroy the credibility of his Holocaust memoir. Its prime concern is the many-faceted ambiguity of liberty in the war on terror. “The world changed,” he said. “It didn’t change with 9/11. It changed with the Patriot Act, with the homeland security measures and the war on terror.”

His 2010 collection, Driving Home, is an eccentric mix of literary criticism, tales of great sea voyages, the state of the US in the 21st century and the mix of people he meets along the way, even as he remained in Seattle. A 2011 essay in the New York Times, The Getaway Car, detailed a drive down the Pacific coast to take Julia, now 18, to university at Stanford, outside San Francisco. Later that year, Raban suffered a massive stroke, which left one side of his body paralysed and confined him to a wheelchair. He continued writing, primarily for the New York Review of Books. It seemed an ironic fate for a writer who saw his journeys as “a means of escape, freedom and solitude, I could be happy … in a way I couldn’t be at home”. Yet he had always travelled through literature, and through his writing. And now he had a different sort of freedom in his daughter, which perhaps allowed him to address his own escape in his last book, to be published this autumn, a memoir titled Father and Son.

Julia survives him.

🔔 Jonathan Raban, writer, born 14 June 1942; died 17 January 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

(you don't have to publish the ask but make sure it's anonymous) please please please don't worry about the anon I think it might be the same person who made a harrass discord group...of course it's good to acknowledge wrongdoings of creators but it doesn't make anyone obligated to stay away from fandom. If you don't support the racist mess that happened it's totally fine if you stay in arcana fandom. Don't worry.

of course, of course. I'm not feeling pressured to leave the fandom right now don't worry about that. I know seeing it can cause a bit of anxiety, and for a little while it did make me feel anxious, I recalled why I wanted to write a lot of the fanfics I make in the first place, I didn't like how they wrote Muriel's ending, and I didn't like how they represented him a lot, so I wanted to make something that fit the image I had of him instead.

Anyways, I was much more curious about the note they made about the problems with Julian being a bird or the various bird motifs and that being antisemitic. I was wondering how or why that was the case, as when I tried searching it up I wasn't really able to find any definite explanations, so I was wondering if they could point me to a resource or something on the topic. I've heard that a merge between an owl and a human can often be antisemitic especially when that owl is presented as an almost demon-like entity with feathers forming horns like that of a great horned owl, and their beak being presented as a large hooked nose. That much, I do understand, but I'm unclear if it applies to the wider range of birds as well, or not.

In my initial search I found a story called Jewbird written by Bernard Malamud, an American-jewish author, and while it serves as the allegory of antisemitism not only coming from outside but inside as well, the nature of the intelligent bird being representative of an older more traditional Jewish individual (according to another source who were likely more able to draw the parallel than I was), presents him as a human-merged with bird individual and the whole point of the text seems to present it as the pure opposite of being antisemitic.

Of course, I can see the possibility of it, that he was presented as a bird in order to subvert the initial expectations and stereotypes, in the same way that Maus by Art Spiegelman does, but I would still like to be better able to understand the bird-antisemitism connection. Does it apply to specific birds? What kind of bird-like representation causes issue? Would the image of birds flying freely over the sky be considered problematic imagery? Why and how? is it the caged bird that is problematic? Why and how? Is there any possible way that this birdlike imagery can spread into other spaces and cause issue? Should Julian never be given feathered wings, regardless if you're creating a bird image or not? is his bird familiar problematic as well??? this is like telling someone unfamiliar with racism against African-american individuals that cotton is not good to them without telling them about the whole history about slavery and cotton picking, leading them to believe that they just take issue with the material of shirts or something.

I know I probably sound kinda nit-pickey, but I am genuinely curious and would love to avoid making any antisemitic mistakes when including Julian and Portia in my works. I wish to avoid this all the time, of course, but most especially now, as discussion on Palestine has spurred a lot of antisemitism due to the cultural genocide from Israel. And while it's clear that what Israel is doing, it's also clear that not all Jewish individuals support that, even though some news groups or people talking about it frame it as if it is.

Of course I'm open and eager for discussion on the other LIs as well and the intricacies of their problematic representation and how that must be handled corrected or re-framed, especially since in the early more.... hostile days of this fandom, I tended to stick to Muriel's route since I hadn't played the other routes in a while/all the way through so I'm a little unaware of all the other characters' misrepresentations (so if you're mentioning Muriel I probably have heard about and considered that one before—this man does not leave my brain lmao)

I can see the possible issues on Nadia being constantly represented as domineering failing to recognize softness in her (which I belive, though correct me if I'm wroing, is about dark skinned women being seen as violent and tough instead of soft or kind), and Asra being represented through Orientalism (mystic, but lesser other with messy foreign traditionalistic magic that must be corrected through the western logic and science—this partly originated in ancient greece so not entirely western as in America)

But yeah, I'm just really curious about it, cause my initial search only brought up news articles about people apologizing for being antisemitic, or the history of antisemitism. Rather than some of the various possible forms of antisemitism or it's possible relation to birds.

#answering asks#the arcana#I put it in the tags on that one post sorry. You probably didn't see because you didn't want to scroll through the hate post#and that's fair#but yeah I'm here for research purposes & to remember and learn from the mistakes of the others in the past.#Anonymous#julian devorak#portia devorak#nadia satrinava#muriel#muriel the arcana#Muriel of the kokhuri#antisemitism#lit analysis

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Becky Beasley’s art is nothing if not autobiographical. In a text accompanying her latest show, “H.S.P. (or Promising Mid-Career Woman),” the British artist alludes to her own depression and drinking. The initials, we’re told, stand for “highly sensitive person,” and the display is described as a “coming-out exhibition.” In 2020, she received a late diagnosis of autism. She also identified herself as progesterone intolerant, and her life experiences—“I was an odd ball, a bit weird, unusual. I was also called unstable, needy, obsessive, demanding, intense, scheming, a monster, a witch”—made belated sense. The primary constituents of “H.S.P.” are photographs, ceramics, and fabric, and that all of these can be classed as “sensitive surfaces” is no accident. Here, Beasley is avowedly owning, even embracing, the capacity to be strongly imprinted.

Beasley produces objects, photographs and texts which are typically informed by a deep engagement with literature — specifically in the past ten years certain writings of William Faulkner, Herman Melville, Bernard Malamud and Thomas Bernhard— and historical research.

https://www.francescaminini.it/artist/becky-beasley/

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lakshmi Kapoor

"...we are all terribly alone no matter what people say."

~Bernard Malamud

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Revision is one of the true pleasures of writing. I love the flowers of afterthought.

Bernard Malamud

#scriptwriting#screenwriting#amwriting#writing#writingquotes#writingadvice#writing quotes#writing advice

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bernard Malamud On Writing

Authors’ reflections on the craft of writing from my curated collection of literary quotes. Discover insights and inspiration for your writing at RolandoAndresRamos.com

View On WordPress

#amwriting#Craft#Inspiration#Quotes#Stories#Storytelling#Writer#Writers#Writerscommunity#WritersonWordpress#Writing#writingcommunity#writinginspiration#writingtips

6 notes

·

View notes