#2022 Russo-Ukrainian War

Photo

Kakhovka Hydroelectric Station // Ukraine

#Russia#invasion#invasion of ukraine#2022 russo-ukrainian war#russo-ukrainian crisis#russo-ukrainian conflict#russo-ukrainian war#war#conflict#ukraine#Kakhovka Hydroelectric Station#Kakhovka#Kherson#Kherson Oblast#russian troops#Kalashnikov#AK-74#AK-74M#rifle#carbine#GP30#grenade launcher#gunblr#milblr#military#armed forces#combat

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Much of the public discussion of Ukraine reveals a tendency to patronize that country and others that escaped Russian rule. As Toomas Ilves, a former president of Estonia, acidly observed, “When I was at university in the mid-1970s, no one referred to Germany as ‘the former Third Reich.’ And yet today, more than 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, we keep on being referred to as ‘former Soviet bloc countries.’” Tropes about Ukrainian corruption abound, not without reason—but one may also legitimately ask why so many members of Congress enter the House or Senate with modest means and leave as multimillionaires, or why the children of U.S. presidents make fortunes off foreign countries, or, for that matter, why building in New York City is so infernally expensive.

The latest, richest example of Western condescension came in a report by German military intelligence that complains that although the Ukrainians are good students in their training courses, they are not following Western doctrine and, worse, are promoting officers on the basis of combat experience rather than theoretical knowledge. Similar, if less cutting, views have leaked out of the Pentagon.

Criticism by the German military of any country’s combat performance may be taken with a grain of salt. After all, the Bundeswehr has not seen serious combat in nearly eight decades. In Afghanistan, Germany was notorious for having considerably fewer than 10 percent of its thousands of in-country troops outside the wire of its forward operating bases at any time. One might further observe that when, long ago, the German army did fight wars, it, too, tended to promote experienced and successful combat leaders, as wartime armies usually do.

American complaints about the pace of Ukraine’s counteroffensive and its failure to achieve rapid breakthroughs are similarly misplaced. The Ukrainians indeed received a diverse array of tanks and armored vehicles, but they have far less mine-clearing equipment than they need. They tried doing it our way—attempting to pierce dense Russian defenses and break out into open territory—and paid a price. After 10 days they decided to take a different approach, more careful and incremental, and better suited to their own capabilities (particularly their precision long-range weapons) and the challenge they faced. That is, by historical standards, fast adaptation. By contrast, the United States Army took a good four years to develop an operational approach to counterinsurgency in Iraq that yielded success in defeating the remnants of the Baathist regime and al-Qaeda-oriented terrorists.

A besetting sin of big militaries, particularly America’s, is to think that their way is either the best way or the only way. As a result of this assumption, the United States builds inferior, mirror-image militaries in smaller allies facing insurgency or external threat. These forces tend to fail because they are unsuited to their environment or simply lack the resources that the U.S. military possesses in plenty. The Vietnamese and, later, the Afghan armies are good examples of this tendency—and Washington’s postwar bad-mouthing of its slaughtered clients, rather than critical self-examination of what it set them up for, is reprehensible.

The Ukrainians are now fighting a slow, patient war in which they are dismantling Russian artillery, ammunition depots, and command posts without weapons such as American ATACMS and German Taurus missiles that would make this sensible approach faster and more effective. They know far more about fighting Russians than anyone in any Western military knows, and they are experiencing a combat environment that no Western military has encountered since World War II. Modesty, never an American strong suit, is in order.

— Western Diplomats Need to Stop Whining About Ukraine

#eliot a. cohen#current events#politics#ukrainian politics#american politics#warfare#strategy#tactics#diplomacy#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#war in afghanistan#vietnam war#ukraine#usa#toomas hendrik ilves

477 notes

·

View notes

Photo

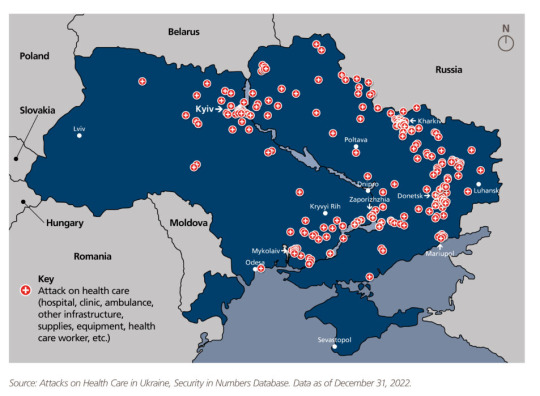

List of every bomb dropped on health care infrastructure in Ukraine by Russia in 2022

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

On war’s second anniversary, Ukraine’s scientific community mourns lost colleagues

As an expert on river ecosystems with the Institute of Hydrobiology, Shevtsova in the 1970s and ’80s traveled frequently for fieldwork to diverse locales including Poland, Iraq, and Libya—a rare privilege for a Soviet scientist. “She was a tiny woman, but always elegant. She was nicknamed ‘Hummingbird,’” Natalia Shevtsova says. At 75, long past the customary retirement age, Lyudmila Shevtsova joined the ecology faculty at National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. Up until the end, “she was still quite intellectually engaged with students and other faculty members. And so friendly—always smiling,” says ecologist Viktor Karamushka, who chairs the university’s Department of Environmental Studies.

Lyudmila Shevtsova wanted her granddaughters, like their mother, to follow in her footsteps and study hydrobiology. They demurred. “I told her I had another vision for my life,” says Daryna Gulei. But when Gulei, 28, phoned her grandmother on 27 December 2023 to say she would defend her Ph.D. in architecture the next day at Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture, “She was so happy! She read my dissertation twice, gave me some questions.” Gulei shared the good news of her successful defense the last time they spoke.

On 2 January, Gulei and her husband sped across Kyiv to the apartment building after her mother called to say they’d been hit. Dawn was breaking over a melee of firefighters, paramedics, and shaken residents. “I felt my grandmother close by,” Gulei says, and just then a paramedic emerged from the building carrying Lyudmila Shevtsova. Her body was riddled with shrapnel, and she had lost a lot of blood, but she was still breathing.

Natalia says her mother was fading fast and could not speak. “But it was clear she understood I was alive. I hope that gave her some comfort,” Natalia says. “Then my dear mother turned her head away, and died.”

#current events#science#academia#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#ukraine#russia#liudmyla shevtsova#volodymyr kozlovskyy#igor galkin

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine that someone—perhaps a man from Florida, or maybe even a governor of Florida—criticized American support for Ukraine. Imagine that this person dismissed the war between Russia and Ukraine as a purely local matter, of no broader significance. Imagine that this person even told a far-right television personality that “while the U.S. has many vital national interests ... becoming further entangled in a territorial dispute between Ukraine and Russia is not one of them.” How would a Ukrainian respond? More to the point, how would the leader of Ukraine respond?

As it happens, an opportunity to ask that hypothetical question recently availed itself. The chair of the board of directors of The Atlantic, Laurene Powell Jobs; The Atlantic’s editor in chief, Jeffrey Goldberg; and I interviewed President Volodymyr Zelensky several days ago in the presidential palace in Kyiv. In the course of an hour-long conversation, Goldberg asked Zelensky what he would say to someone, perhaps a governor of Florida, who wonders why Americans should help Ukraine.

Zelensky, answering in English, told us that he would respond pragmatically. He didn’t want to appeal to the hearts of Americans, in other words, but to their heads. Were Americans to cut off Ukraine from ammunition and weapons, after all, there would be clear consequences in the real world, first for Ukraine’s neighbors but then for others:

If we will not have enough weapons, that means we will be weak. If we will be weak, they will occupy us. If they occupy us, they will be on the borders of Moldova and they will occupy Moldova. When they have occupied Moldova, they will [travel through] Belarus and they will occupy Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. That’s three Baltic countries which are members of NATO. They will occupy them. Of course, [the Balts] are brave people, and they will fight. But they are small. And they don’t have nuclear weapons. So they will be attacked by Russians because that is the policy of Russia, to take back all the countries which have been previously part of the Soviet Union.

And after that, if there were still no further response? Then, he explained, the struggle would continue:

When they will occupy NATO countries, and also be on the borders of Poland and maybe fight with Poland, the question is: Will you send all your soldiers with weapons, all your pilots, all your ships? Will you send tanks and armored vehicles with your young people? Will you do it? Because if you will not do it, you will have no NATO.

At that point, he said, Americans will face a different choice: not politicians deciding whether “to give weapons or not to give weapons” to Ukrainians, but instead, “fathers and mothers” deciding whether to send their children to fight to keep a large part of the planet, filled with America’s allies and most important trading partners, from Russian occupation.

But there would be other consequences too. One of the most horrifying weapons that Russia has used against Ukraine is the Iranian-manufactured Shahed drone, which has no purpose other than to kill civilians. After these drones are used to subdue Ukraine, Zelensky asked, how long would it be before they are used against Israel? If Russia can attack a smaller neighbor with impunity, regimes such as Iran’s are sure to take note. So then the question arises again: “When they will try to occupy Israel, will the United States help Israel? That is the question. Very pragmatic.”

Finally, Zelensky posed a third question. During the war, Ukraine has been attacked by rockets, cruise missiles, ballistic missiles—“not hundreds, but thousands”:

So what will you do when Russia will use rockets to attack your allies, to [attack] civilian people? And what will you do when Russia, after that, if they do not see [opposition] from big countries like the United States? What will you do if they will use rockets on your territory?

And this was his answer: Help us fight them here, help us defeat them here, and you won’t have to fight them anywhere else. Help us preserve some kind of open, normal society, using our soldiers and not your soldiers. That will help you preserve your open, normal society, and that of others too. Help Ukraine fight Russia now so that no one else has to fight Russia later, and so that harder and more painful choices don’t have to be made down the line.

“It’s about nature. It’s about life,” he said. “That’s it.”

#current events#warfare#politics#russian politics#american politics#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#russia#ukraine#usa#volodymyr zelenskyy#ron desantis#nato

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

#україна#ukraine#war in ukraine#russian invasion of ukraine#ukrainian genocide#russo ukrainian war#food shortage 2022#food shortages

337 notes

·

View notes

Text

#european politics#europe#ukraine#ukrainian crisis#russo ukrainian war#imperial russia#russia#2022#adam something#vladimir putin#fuck putin#memes#shitpost#war#maps

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s been nearly eight months since Russian President Vladimir Putin sent troops and tanks over the border into Ukraine, and a lot has changed in that time. Ukraine has shown itself to be a far more robust military force than pretty much anyone predicted. Talk has changed from wondering how long Ukraine could hold out to how much territory it can retake — and to when and how the war will end.

But it’s still hard to imagine how Putin’s war on Ukraine will conclude. Does Putin even have an endgame? If he really wants to control Ukrainian territory, why does he seem so bent on destroying it?

To get insights into these questions, I reached out to Fiona Hill, one of America’s most clear-eyed observers of Russia and Putin, who served as an adviser to former President Donald Trump and gained fame for her testimony in his first impeachment trial. In the early days of Russia’s war on Ukraine, Hill warned in an interview with POLITICO that what Putin was trying to do was not only seize Ukraine but destroy the current world order. And she recognized from the start that Putin would use the threat of nuclear conflict to try to get his way.

Now, despite the setbacks Russia has suffered on the battlefield, Hill thinks Putin is undaunted. She sees him adapting to new conditions, not giving up. And she sees him trying to get the West to accede to his aims by using messengers like billionaire Elon Musk to propose arrangements that would end the conflict on his terms.

“Putin plays the egos of big men, gives them a sense that they can play a role. But in reality, they’re just direct transmitters of messages from Vladimir Putin,” Hill says.

But while Putin appears to be doubling down in Ukraine, the conflict poses some real dangers to his leadership. He has identified himself quite directly with the war, Hill notes, and he can’t afford to look like a loser. If he begins to lose support from Russian elites, his hold on power could slip.

The West has come a long way since February in understanding the stakes in Ukraine, Hill says, but the world still hasn’t totally grasped the full challenge Putin is posing. Putin must be contained, Hill says, but that won’t happen unless and until international institutions established in the wake of World War II evolve so they can contain him. And that conversation is only just beginning.

“This is a great power conflict, the third great power conflict in the European space in a little over a century,” Hill says. “It’s the end of the existing world order. Our world is not going to be the same as it was before.”

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

REYNOLDS: The war clearly hasn’t gone as Putin originally intended. How has Putin reacted to his setbacks and how do you think his mindset is evolving?

HILL: Whenever he has a setback, Putin figures he can get out of it, that he can turn things around. That’s partly because of his training as a KGB operative. In the past, when asked about the success of operations, he’s pooh-poohed the idea that operations always go as planned, that everything is always perfect. He says there are always problems in an operation, there are always setbacks. Sometimes they’re absolute disasters. The key is adaptation.

Another hallmark of Putin is that he doubles down. He always takes the more extreme step in his range of options, the one that actually cuts off other alternatives. Putin has often related an experience he had as a kid, when he trapped a rat in a corner in the apartment building he lived in, in Leningrad, and the rat shocked him by jumping out and fighting back. He tells this story as if it’s a story about himself, that if he’s ever cornered, he will always fight back.

But he’s also the person who puts himself in the corner. We know that the Russians have had very high casualties and that they’ve been running out of manpower and equipment in Ukraine. The casualty rate on the Russian side keeps mounting. A few months ago, estimates were 50,000. Now the suggestions are 90,000 killed or severely injured. This is a real blow given the 170,000 Russia troops deployed to the Ukrainian border when the invasion began.

So, what does Putin do? He sends even more troops in by launching a full-on mobilization. He still hasn’t said this is a war. It remains a “special military operation,” but he calls up 300,000 people. Then, he goes several steps further and announces the annexation of the territories that Russia has been fighting over for the last several months, not just Donetsk and Luhansk, but also the territories of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia.

Putin gives himself no way out except to pursue the original goals he had when he went in, which is the dismemberment of Ukraine and Russia annexing its territory. And he’s still trying to adapt his responses to setbacks on the battlefield.

REYNOLDS: At this point, if he’s so adaptive, do you think he has an endgame?

HILL: In his mind, I think Putin still thinks he’s got more game to play. His endgame is to go out of this war on his terms. What we’re seeing right now, with the annexations and the big speech that he made on September 30th is very clear. He sees this conflict as a full-on war with the West, and he still is adamant on removing Ukraine from the map and from global affairs.

It’s also clear that he has no intention whatsoever of giving up Donetsk and Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, as well as Crimea, which he’s already taken and already declared as part of Russia for time immemorial.

REYNOLDS: Why does Putin want all that territory? Does he want the symbolism of having restored an important part of the Russian Empire, reestablishing this mythological Novorossiya, taking back lands that Russia seized from the Ottoman Empire? Or does he really want to rule this part of modern-day Ukraine in concrete, practical ways?

HILL: It’s actually both of those things. They are inextricably linked. You mentioned this idea of Novorossiya, “New Russia.” I think most people have forgotten that he used this term in 2014. Back then, the Kremlin triggered the war in Donbas as part of an effort to regain control of the territories of Novorossiya that were first annexed from the Ottoman Empire by Catherine the Great back in the late 18th century.

There wasn’t really a lot of settlement there then, and that’s how we got Potemkin villages — Prince Grigory Potemkin took Catherine on a carriage ride through her new dominion and they created fake villages, with peasants brought in to wave at the empress as she went by.

We have this same issue now — what and who is Putin presiding over? Even Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s press secretary, recently admitted that Russia hasn’t quite worked out the borders of the annexed areas yet, because the Ukrainians have been pushing back. The question of what Russia actually controls beyond all the symbolism of annexation is still a major question.

REYNOLDS: If Putin wants Ukrainian territory so badly, why is he raining down such destruction on civilian areas and committing so many human rights abuses in occupied areas?

HILL: This is punishment, but also perverse redevelopment. You cow people into submission, destroy what they had and all their links to their past and their old lives, and then make them into something new and, thus, yours. Destroy Ukraine and Ukrainians. Build New Russia and create Russians. Its brutal but also a hallmark of imperial conquest.

REYNOLDS: And it’s how they did it in the 18th century.

HILL: Exactly. Putin would love to control the territory. But control involves actually having people on your side. And that is really a big question. We’ve seen in all of these territories, Russia shipping people out or detaining them, from entire families and children to teachers, administrators and local police, and then proxy citizens sent in from Russia itself.

Putin’s initial goal when he launched the invasion was the collapse of central Ukrainian authority, the imposition of a puppet government in Kyiv, and all local governments swearing allegiance to Moscow, probably with some political commissar-type proxy leaders put in place around the country — the kind of thing that we saw happening in 2014 in the Russian-occupied territories of Donetsk and Lugansk and Crimea. But of course, that didn’t happen. So the problem that Putin has is controlling people in these territories rather than playing his own version of Potemkin villages.

REYNOLDS: We’ve recently had Elon Musk step into this conflict trying to promote discussion of peace settlements. What do you make of the role that he’s playing?

HILL: It’s very clear that Elon Musk is transmitting a message for Putin. There was a conference in Aspen in late September when Musk offered a version of what was in his tweet — including the recognition of Crimea as Russian because it’s been mostly Russian since the 1780s — and the suggestion that the Ukrainian regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia should be up for negotiation, because there should be guaranteed water supplies to Crimea. He made this suggestion before Putin’s annexation of those two territories on September 30. It was a very specific reference. Kherson and Zaporizhzhia essentially control all the water supplies to Crimea. Crimea is a dry peninsula. It has aquifers, but it doesn’t have rivers. It’s dependent on water from the Dnipro River that flows through a canal from Kherson. It’s unlikely Elon Musk knows about this himself. The reference to water is so specific that this clearly is a message from Putin.

Now, there are several reasons why Musk’s intervention is interesting and significant. First of all, Putin does this frequently. He uses prominent people as intermediaries to feel out the general political environment, to basically test how people are going to react to ideas. Henry Kissinger, for example, has had interactions with Putin directly and relayed messages. Putin often uses various trusted intermediaries including all kinds of businesspeople. I had intermediaries sent to discuss things with me while I was in government.

This is a classic Putin play. It’s just fascinating, of course, that it’s Elon Musk in this instance, because obviously Elon Musk has a huge Twitter following. He’s got a longstanding reputation in Russia through Tesla, the SpaceX space programs and also through Starlink. He’s one of the most popular men in opinion polls in Russia. At the same time, he’s played a very important part in supporting Ukraine by providing Starlink internet systems to Ukraine, and kept telecommunications going in Ukraine, paid for in part by the U.S. government. Elon Musk has enormous leverage as well as incredible prominence. Putin plays the egos of big men, gives them a sense that they can play a role. But in reality, they’re just direct transmitters of messages from Vladimir Putin.

REYNOLDS: Putin is very comfortable dealing with billionaires and oligarchs. That’s a world that he knows well. But by using Musk this way, he goes right over the heads of [Ukrainian President Volodymyr] Zelenskyy and the Ukrainian government.

HILL: He is basically short-circuiting the diplomatic process. He wants to lay out his terms and see how many people are going to pick them up. All of this is an effort to get Americans to take themselves out of the war and hand over Ukraine and Ukrainian territory to Russia.

REYNOLDS: You have compared Putin’s invasion of Ukraine to Hitler’s invasions of other countries in World War II, of Czechoslovakia, of Poland. Do you still see it that way? Do you think that Putin has become Hitler-like in how he thinks of himself and how he seeks territory?

HILL: Yes, but also like Kaiser Wilhelm in World War I as well. Look, exactly 100 years before Putin annexed Crimea in 2014, in 1914, the Germans invaded Belgium and France and World War I was fought as a Great Power conflict to eject Germany from Belgium and France. And World War II in Europe, of course, was a refighting territorially of many of the outcomes of World War I.

Part of the problem is that conceptually, people have a hard time with the idea of a world war. It brings all kinds of horrors to mind — the Holocaust and the detonation of nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the dawning of the nuclear age. But if you think about it, a world war is a great power conflict over territory which overturns the existing international order and where other states find themselves on different sides of the conflict. It involves economic warfare, information warfare, as well as kinetic war.

We’re in the same situation. Again, Putin invaded Ukraine in 2014, exactly 100 years after Germany invaded Belgium and France — and just in the same way that Hitler seized the Sudetenland, annexed Austria and invaded Poland. We’re having a hard time coming to terms with what we’re dealing with here. This is a great power conflict, the third great power conflict in the European space in a little over a century. It’s the end of the existing world order. Our world is not going to be the same as it was before.

People worry about this being dangerous hyperbole. But we have to really accept what the situation is to be able to respond appropriately. Each war has been fought differently. Modern wars involve information space and cyberspace, and we’ve seen all of these at play here. And, in the 21st century, these are economic and financial wars. We’re all-in on the financial and economic side of things.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has turned global energy and food security on its head because of the way Russia is leveraging gas and oil and the blockade Putin has imposed in the Black Sea against Ukrainian grain exports. Russia has not just targeted Ukrainian agricultural production, as well as port facilities for exporting grain, but caused a global food crisis. These are global effects of what is very clearly not just a regional war.

Keep in mind that Putin himself has used the language of both world wars. He’s talked about the fact that Ukraine did not exist as a state until after World War I, after the dissolution of the Russian Empire and the creation of the Soviet Union. He has blamed the early Soviets for the formation of what he calls an artificial state. Right from the very beginning, Putin himself has said that he is refighting World War II. So, the hyperbole has come from Vladimir Putin, who has said that he’s reversing all of the outcomes territorially from World War I and also, in effect, World War II and the Cold War. He’s not accepting the territorial configuration of Europe as it currently is.

What we have to figure out now is, how are we going to contend with this?

REYNOLDS: China and India, Xi Jinping, Narendra Modi, and other world leaders who have not exactly been with West on this — how do you think their views of what Russia is doing is changing?

HILL: This is another global dimension. Just before the invasion, at the Beijing Olympics, we had Xi Jinping and Putin standing in seeming solidarity, talking about a limitless partnership, and Xi Jinping being very explicit in terms of Chinese opposition to the expansion of NATO and the role of NATO in the world. Clearly, at that point, Xi and China didn’t expect that Vladimir Putin’s special military operation would turn into the largest military action in Europe since World War II. Now, Xi Jinping is leery about showing any kind of diminution of his support for Vladimir Putin and Russia, since that would suggest he made a major miscalculation in lending Putin support. We haven’t seen Xi repudiating Putin and Russia directly. But we’ve certainly seen some signs of concern. At a meeting in Central Asia around the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Putin himself acknowledged that China had concerns. We’re pretty sure at this point that the Chinese also don’t like Vladimir Putin’s nuclear saber rattling in the context of the war in Ukraine, because that destabilizes the larger strategic balance globally, not just in Europe.

For India, this has been a nightmare, frankly, and they’ve been trying to straddle the fence and figure out a balance. They don’t want to get on the wrong side of the United States or Ukraine, or Russia, and they just don’t really know quite what to do. Nonetheless, Prime Minister Modi has said explicitly to Putin, look, this is a time for peace, not war. And being much more outspoken on the issue of the conflict than perhaps some might have anticipated. That’s not insignificant.

Once we get past the party Congress in China, we should watch how the Chinese-Russian relationship plays out. China would be instrumental in signaling to Putin how far he can go in terms of pursuing his endgame.

REYNOLDS: Let’s talk about the situation inside Russia. Do you think Putin was surprised by the wave of protests that followed his announcement of what he called a partial mobilization? Or was he expecting that?

HILL: Yes, he was expecting pushback which is why he called it partial when it’s really a stealth full mobilization. The goal is to try to get the military up to full strength and get everybody he possibly can. The problem is that all these new forces are not battle ready. Many have had minimal military training. It’s very clear that most of them are going to be used as cannon fodder.

Putin’s responding not just to the setbacks on the battlefield, but to setbacks in the information war in the domestic arena. He’s getting pushback from the party of war. We have to remember there were nationalists since the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s who wanted to retake Ukraine, not just Crimea, and reabsorb all the Russian-speaking territories. People in the cohort around Putin have pushed the invasion of Ukraine for some considerable period of time, and he has to keep them on his side. They are not satisfied. They want Ukraine dismembered.

The shock, perhaps, is how many Russians have fled the mobilization. Although Russian authorities have been going to the borders to forcibly conscript people lining up to leave, they still haven’t taken the step of closing all the borders off. Putin and the Kremlin are aware that they would get a massive backlash if they did. We’ve already seen violence in Dagestan and other places where ethnic minorities have borne the brunt of recruitment. I think they are very, very aware that they’ve got to leave a safety valve open because otherwise there might be more protests, and more violence in response to the mobilization.

REYNOLDS: If there are more protests and more violence, does that pose a threat to Putin as leader? How weak or vulnerable is Putin’s position right now?

HILL: Back to the Soviet period, there were tens of thousands of violent protests across the Soviet Union over the years. This didn’t lead to the disintegration of the Soviet Union because of severe repression. It was something messy they had to deal with. They decapitated the opposition, and that’s what Putin’s done. Russia is back to the USSR. Opposition leader Alexei Navalny is in isolation in a penal colony. The repressive capacity of the government is pretty significant. They’ve been taking thousands of people off the streets and putting them in jail. I think Putin feels he can decapitate any organized opposition. He has to just be careful to control the sheer number of opposition protests, which is, again, why they’re keeping the safety valves open.

Putin knows Russian history. World War I did lead to mass protests. The defeat in the Russo-Japanese War earlier in the 1900s also led to mass protests that got out of hand and discredited the czarist system. All of this could discredit him. So, there is some real risk. What he’s making sure of is that there’s no one who could lead these protests and make them coalesce.

If you think back to when Navalny was poisoned in 2020, he was out in the Urals region and Siberia, pulling together opposition groups at a time when there were many protests going on in Russia. He was poisoned because he was getting some traction.

Nonetheless, the mobilization chips away at Putin’s popularity because people feel that they’ve got no hope. They’re no longer able to watch the war on their TV screens and switch it off and forget it’s happening. They’re forced to confront it. Support for the war was already fairly passive, but active support for the war is declining and support for Putin himself will decline as well. And he’s got to keep placating the hardliners. So, he’s got to take extreme actions.

You’re going to start hearing more and more stories of people who’ve gone to the front completely unprepared and got killed. That will reduce tolerance for the special military operation. If that happens, it could impact Putin’s standing among the elite. He’s been pretty much unassailable as long as he’s been the only really truly popular politician in Russia. But if he starts to look like a loser, then he no longer seems infallible. He’s no longer the strongman and arbiter of the system. Although elites are invested in him and his system, there may eventually come a point where people start saying, “maybe somebody else, Vladimir Vladimirovich, maybe somebody else might handle the system better.” It could start with the hardliners trying to push themselves forward.

That’s why, again, we see him doubling down. He’s got himself in a corner in the war and in a corner domestically at home. He has made himself the face of this war in Ukraine. His September 30th speech basically said it’s his war, his annexation, his Russia. And so, everything will fall on him if it falls apart.

REYNOLDS: In the autocratic system that Putin has built, he has to stand for election every so often even though it’s mostly window dressing. But it periodically renews his legitimacy. One of those years is 2024. Is he facing a deadline? Does he need to look like he’s won this war by 2024?

HILL: One would think so. In 2024, the reelection has to be in the early part of the year. So, we’ve got a year and a few months in the Russian political calculations to start to prepare for this and ensure that it all goes smoothly. That was why Putin wanted to get the quick victory in Ukraine well out of the way. Ukraine started in February and March of 2022, because February and March of 2024 will be election time.

I’m sure Putin thought he would have been unassailable with a quick, victorious war. Ukraine would be back in the fold and then probably after that, Belarus. Moldova as well, perhaps. There would have been a reframing of the next phase of Putin as the great czar of a reconstituted “Russkiy mir” or “Russian world.”

If Putin had succeeded at that, maybe he could have found himself in a position where he could have begun to delegate some power to others.

Just this past week, on October 7th, Putin turned 70. He’s in that age when people are asking, does he die in office? There are lots of questions about succession. 2024 is very much an inflection point for the system.

REYNOLDS: Do you feel like Ukraine is on course for a military victory and what would that mean to the Russian side?

HILL: Ukraine has already had a great moral, political and military victory. Russia has not achieved the aims of its special military operation. But I think Putin is obviously hoping that now, with all of the nuclear saber-rattling, threats of nuclear Armageddon, deploying Elon Musk and others to convey his messages, that basically he can take the territory that he’s got and get recognition of that. And then he hopes that he will be able to put pressure back on Ukraine. He’d still like to see the Ukrainian political system crumble away. He’d like to get somebody as leader of Ukraine who is personally loyal to him. Putin hopes that he’ll still prevail, that he’ll find other ways of getting what he wanted when he went across the border in February.

REYNOLDS: So to some extent, the biggest thing that Putin wants right now is to get Zelenskyy out. He wants somebody more pliant.

HILL: That’s exactly what he wants. And I’m sure he feels that he might still get that. I mean, everything that he’s doing is an effort to discredit Ukraine and Ukrainians and Zelenskyy.

Ukraine has the right to choose their own leadership. But Putin will try to manipulate this whichever way he can. He’ll keep trying to soften the battlefield beyond Ukraine, keep on trying to poison attitudes internationally against Ukraine.

REYNOLDS: Along those lines, what do you make of the fact that some Americans, primarily in the Trump wing of the Republican Party and some Fox News personalities, are expressing doubts about how much support the United States should direct to Ukraine? Is there something about this conflict that you don’t think they understand?

HILL: This goes back to the point I tried to make when I testified at the first impeachment trial against President Trump. There’s a direct line between that episode and now. Putin has managed to seed hostile sentiment toward Ukraine. Even if people think they are criticizing Ukraine for their own domestic political purposes, because they want to claim that the Biden administration is giving too much support for Ukraine instead of giving more support to Americans, etc. — they’re replaying the targeted messaging that Vladimir Putin has very carefully fed into our political arena. People may think that they’re acting independently, but they are echoing the Kremlin’s propaganda.

REYNOLDS: What do you think is the right response from the West if Putin does detonate some sort of nuclear weapon, either as a demonstration or something else?

HILL: What Putin is trying to do is to get us to talk about the threat of nuclear war instead of what he is doing in Ukraine. He wants the U.S. and Europe to contemplate, as he says, the risks that we faced during the Cuban Missile Crisis or the Euromissile crisis. He wants us to face the prospect of a great superpower war. His solution is to have secret diplomacy, as we did during Cuban Missile Crisis, and have a direct compromise between the United States and Russia.

But there’s no strategic standoff here. This is pure nuclear blackmail. There can’t be a compromise based on him not setting off a nuclear weapon if we hand over Ukraine. Putin is behaving like a rogue state because, well, he is a rogue state at this point. And he’s being explicit about what he wants. We have to pull all the diplomatic stops out. We have to ensure that he’s not going to have the effect that he wants with this nuclear brinkmanship.

Putin is also making it very clear that to get what you want in the world, you have to have a nuclear weapon and to protect yourself, you also have to have a nuclear weapon. So this is an absolute mess. Global nuclear stability is on a knife edge.

But again, this is not about strategic issues. This is not an issue of strategic stability. This is Vladimir Putin pissed off because he hasn’t got what he wanted in a war that he started. It’s another attempt to adapt to the battlefield.

REYNOLDS: Can this war end in a way that would be satisfying for the West and with Putin remaining as Russian leader? Or is this the beginning of a revolution that’s going to be very messy and dangerous?

HILL: It’s unlikely this ends in any satisfying way. You need every side willing to compromise, and Putin doesn’t want to compromise his goals.

Any compromise is, in any case, always at Ukraine’s expense because Putin has taken Ukrainian territory. If we think about World War I, World War II or the settlements in many other conflicts, they always involved some kind territorial disposition that left one side very unhappy.

There is not going to be a happy or satisfying ending for anybody, and it’s also not going to be happy or satisfying for Vladimir Putin either, honestly.

REYNOLDS: It is striking to me that of all the conflicts that Russia has been engaged in since Putin became president, that none of them have been resolved with any kind of a peace settlement. They just have been fought to stalemate.

HILL: There’s not any good outcome I can see come out of this. What’s incumbent upon us is to figure out is how to constrain Russia’s ability to put Ukraine under pressure again in the future or invade again. If there’s any interim freezing of battle lines, make sure that they’re not recognized as official. Maybe we can contemplate some international receivership. We’ve had many of these different formulations in the past for disputed territory. We have to ensure, again, that Ukraine can always defend itself and make it impossible for Putin to break out of constraints and do this again.

But that still leaves you with lots of questions about the future relationship with Russia, the future configuration of any European security institutions. How do we reconfigure ourselves internationally to deal with this? The United Nations has proven to be in dire need of an overhaul. The United Nations has been a major player in this conflict. The secretary-general has been heavily involved investigating war crimes and pressing resolutions. But the United Nations has shown itself inadequate because of the configuration of the Security Council and the veto. Everybody’s talking about how to address this.

REYNOLDS: It occurs to me that there’s a kind of reckoning coming for NATO. With Finland joining, that adds a long direct border between NATO and Russia. With the new union between Belarus and Russia, there’s going to be another NATO border between Poland and Belarus. Considering the fact that NATO’s already getting a line across Europe that it’s going to have to defend, should NATO consider membership for Ukraine?

HILL: This is also going to be a big issue, right? There are so many people out there who still look at Ukraine as a proxy war. Many of the people trying to push Ukraine to surrender are basically those who believe that the United States or NATO is somehow using Ukraine in a proxy war with Russia.

We’re not in a proxy war with Russia, just like we weren’t in a proxy war with Germany during World War I when we were trying to get German forces out of France and Belgium. It wasn’t a proxy war either when we were trying to get Germany out of Poland and all the other places that it invaded in Europe during World War II. We are trying to help Ukraine liberate itself, having been invaded by Russia.

This whole proxy war debate deprives Ukraine of agency. But, if we talk about Ukraine being part of NATO at this particular moment, it will simply feed into this flawed discussion. It will detract from the essence of what this war is, which is Russia trying to seize Ukrainian territory.

Russia believes NATO is simply a cover for the United States in Europe. I think it should be very clear right now with Finland and Sweden wanting to join that this is not the case at all. Finland and Sweden did not apply to NATO before, they have now because NATO is focused on ensuring common collective security and defense, and Russia has put all of Europe at risk.

I see current NATO expansion as a kind of an interim step, a way station to thinking more broadly about how we configure ourselves after Ukraine.

You know, there’s also talk about making Ukraine a “giant Israel,” making Ukraine completely self-sufficient for its own security, as, frankly, Finland was before. I think we have to have an open discussion about all of this and not be fixated on one aspect or another.

REYNOLDS: In other words, even if Ukraine wins the war for its territory, even if Putin is somehow constrained or deposed, we’re still at the very beginning of a rethinking of the international order that those outcomes are not going to solve.

HILL: Yes. We’ve also had the impacts of COVID. We’ve got a climate crisis, which should be evident to everybody by now. There are so many things that we need to contend with, and we’ve only got the skeleton of an international system.

Putin is holding the whole world hostage. We’ve got so many things that we have to deal with. I understand why the Global South is so frustrated with all of this: “While you’re fighting this war in Ukraine over the same kind of territorial disputes you guys have been having for a hundred years now, we’re dying here from disease and climate change. Our countries have flooded. We’re starving and you guys are expecting us to help you solve this?” The United Nations system is breaking down, as [António] Guterres, the secretary-general, has said over and over again. All the alarm bells are going off. And Vladimir Putin is behaving as if it’s the 1780s all over again.

REYNOLDS: So we need a new or a revamped global order to address the whole problem?

HILL: That’s obvious. So how do we do it? A lot of people don’t find the idea of a revamped United Nations very popular. I can just imagine some of my former colleagues groaning loudly. We definitely need a slimmed-down version.

But we do need international institutions to deal with the magnitude of the problems that we’re facing. It’s ironic that Elon Musk, the man who has been talking about getting us to Mars should be Putin’s messenger for the war in Ukraine, when we’re having a really hard time getting our act together on this planet. But it’s glaringly obvious to ordinary people that we need to do so. Time is not on our side.

#us politics#news#politico#2022#fiona hill#us foreign policy#Maura Reynolds#russia#valdimir putin#ukriane#volodymyr zelensky#russo ukrainian war#imperial russia#world news#world politics#european politics#european union#elon musk#world war 1#world war 2#Novorossiya#starlink#Xi Jinping#china#Narendra Modi#india#nato alliance#united nations#finland#sweden

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mariupol Offensive // Donetsk People's Republic

#2022 Russo-Ukrainian War#Russo-Ukrainian War#Russo-Ukrainian Crisis#Russian invasion of ukraine#invasion of ukraine#invasion#Mariupol#Mariupol Offensive#May Offensive#April Offensive#Russian Forces#Donetsk People’s Republic#DPR#Siege of Mariupol#Russian Naval Infantry#Naval Infantry#Alexey Kudenko#AK-12#AK-74#Kalashnikov#Azovstal#BMD#BMD-4#Donetsk#gunblr#milblr#armed forces#Donetsk Oblast

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the terrible winter of 1932–33, brigades of Communist Party activists went house to house in the Ukrainian countryside, looking for food. The brigades were from Moscow, Kyiv, and Kharkiv, as well as villages down the road. They dug up gardens, broke open walls, and used long rods to poke up chimneys, searching for hidden grain. They watched for smoke coming from chimneys, because that might mean a family had hidden flour and was baking bread. They led away farm animals and confiscated tomato seedlings. After they left, Ukrainian peasants, deprived of food, ate rats, frogs, and boiled grass. They gnawed on tree bark and leather. Many resorted to cannibalism to stay alive. Some 4 million died of starvation.

At the time, the activists felt no guilt. Soviet propaganda had repeatedly told them that supposedly wealthy peasants, whom they called kulaks, were saboteurs and enemies—rich, stubborn landowners who were preventing the Soviet proletariat from achieving the utopia that its leaders had promised. The kulaks should be swept away, crushed like parasites or flies. Their food should be given to the workers in the cities, who deserved it more than they did. Years later, the Ukrainian-born Soviet defector Viktor Kravchenko wrote about what it was like to be part of one of those brigades. “To spare yourself mental agony you veil unpleasant truths from view by half-closing your eyes—and your mind,” he explained. “You make panicky excuses and shrug off knowledge with words like exaggeration and hysteria.”

He also described how political jargon and euphemisms helped camouflage the reality of what they were doing. His team spoke of the “peasant front” and the “kulak menace,” “village socialism” and “class resistance,” to avoid giving humanity to the people whose food they were stealing. Lev Kopelev, another Soviet writer who as a young man had served in an activist brigade in the countryside (later he spent years in the Gulag), had very similar reflections. He too had found that clichés and ideological language helped him hide what he was doing, even from himself:

I persuaded myself, explained to myself. I mustn’t give in to debilitating pity. We were realizing historical necessity. We were performing our revolutionary duty. We were obtaining grain for the socialist fatherland. For the five-year plan.

There was no need to feel sympathy for the peasants. They did not deserve to exist. Their rural riches would soon be the property of all.

But the kulaks were not rich; they were starving. The countryside was not wealthy; it was a wasteland. This is how Kravchenko described it in his memoirs, written many years later:

Large quantities of implements and machinery, which had once been cared for like so many jewels by their private owners, now lay scattered under the open skies, dirty, rusting and out of repair. Emaciated cows and horses, crusted with manure, wandered through the yard. Chickens, geese and ducks were digging in flocks in the unthreshed grain.

That reality, a reality he had seen with his own eyes, was strong enough to remain in his memory. But at the time he experienced it, he was able to convince himself of the opposite. Vasily Grossman, another Soviet writer, gives these words to a character in his novel Everything Flows:

I’m no longer under a spell, I can see now that the kulaks were human beings. But why was my heart so frozen at the time? When such terrible things were being done, when such suffering was going on all around me? And the truth is that I truly didn’t think of them as human beings. “They’re not human beings, they’re kulak trash”—that’s what I heard again and again, that’s what everyone kept repeating.

— Ukraine and the Words That Lead to Mass Murder

#anne applebaum#ukraine and the words that lead to mass murder#current events#history#politics#russian politics#sociology#psychology#communism#warfare#totalitarianism#propaganda#holodomor#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#russia#ukraine#viktor kravchenko#lev kopelev#vasily grossman#kulaks

263 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thermal anomaly hotspots in Ukraine from February to July 2022 as sensed by MODIS.

by CascadiaMac

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

why (and i cannot stress this enough) the fuck is a country whose soldiers beheaded a prisoner of war on camera permitted to remain a member of the UN, let alone a permanent member of the UN Security Council. jesus fucking christ.

#toaster thoughts#serious post#violence tw#dismemberment tw#war tw#united nations#russia#ukraine#russo ukrainian war#russian invasion of ukraine (2022)#i want to break something. fuck man

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wagner Group mercenaries marched 800 kilometers across Russia, shot down planes and helicopters, took over a regional military command, provoked a panic in Moscow—troops dug trenches, the mayor told everyone to stay home—and then stood down. Yet in a way, the strangest aspect of Saturday’s aborted coup was the reaction of the people of Rostov-on-Don, including the city’s military leaders, to the soldiers who arrived and declared themselves to be their new rulers.

The Wagner mercenaries showed up in the city early Saturday morning. They met no resistance. Nobody shot at them. One photograph, published by The New York Times, shows them walking at a leisurely pace across a street, one of their tanks in the background, holding yellow coffee cups.

Yevgeny Prigozhin, Wagner’s violent ex-con leader, posted videos of himself chatting with the local commanders in the courtyard of the headquarters of Russia’s Southern Military District. Nobody seemed to mind his being there.

Outside, street sweepers continued their work. Early in the morning, a few people came to gawk, but not many. After Russian President Vladimir Putin gave a panicked speech on television, comparing the situation to 1917 and evoking the ghost of civil war, one man pushing a bicycle was filmed berating the Wagnerites and telling them to go home. The troops laughed him off. But later in the day, more people showed up, and the atmosphere grew warmer.

People shook their hands, brought them food, took selfies. “People are bringing pirozhki, apples, chips. Everything there in the store has been bought to give to the soldiers,” one woman said on camera. In the evening, after Prigozhin had decided to stand down and go home (wherever home turns out to be), he drove away in an SUV with crowds filming him on their cellphones and cheering him on, as if he were a celebrity leaving a movie premiere or a gallery opening. Some chanted “Wagner! Wagner!” as the troops emerged into the street. This was the most remarkable aspect of the whole day: Nobody seemed to mind, particularly, that a brutal new warlord had arrived to replace the existing regime—not the security services, not the army, and not the general public. On the contrary, many seemed sorry to see him go.

The response is hard to understand without reckoning with the power of apathy, a much undervalued political tool. Democratic politicians spend a lot of time thinking about how to engage people and persuade them to vote. But a certain kind of autocrat, of whom Putin is the outstanding example, seeks to convince people of the opposite: not to participate, not to care, and not to follow politics at all. The propaganda used in Putin’s Russia has been designed in part for this purpose. The constant provision of absurd, conflicting explanations and ridiculous lies—the famous “firehose of falsehoods”— encourages many people to believe that there is no truth at all. The result is widespread cynicism. If you don’t know what’s true, after all, then there isn’t anything you can do about it. Protest is pointless. Engagement is useless.

But the side effect of apathy was on display yesterday as well. For if no one cares about anything, that means they don’t care about their supreme leader, his ideology, or his war. Russians haven’t flocked to sign up to fight in Ukraine. They haven’t rallied around the troops in Ukraine or held emotive ceremonies marking either their successes or their deaths. Of course they haven’t organized to oppose the war, but they haven’t organized to support it either.

Because they are afraid, or because they don’t know of any alternative, or because they think it’s what they are supposed to say, they tell pollsters that they support Putin. And yet, nobody tried to stop the Wagner group in Rostov-on-Don, and hardly anybody blocked the Wagner convoy on its way to Moscow. The security services melted away, made no move and no comment. The military dug some trenches around Moscow and sent some helicopters; somebody appears to have sent bulldozers to dig up the highways, but that was all we could see. Who will respond if a more serious challenge to Putin ever emerges? Certainly the military will think twice: Perhaps a dozen Russian servicemen, mostly pilots, died at the hands of the Wagner mutineers, more than died during the failed coup of 1991. Nobody seems particularly bothered about them.

One day after this aborted coup, it is too early to speculate about Prigozhin’s true motives, about what he was really given in exchange for standing down, about where Putin really spent the day on Saturday—some say St. Petersburg, some say a dacha in Novgorod—or about anything else, really. But the flimsiness of this regime’s ideology and the softness of its support have been suddenly laid bare. Expect more repression as Putin tries to stay in charge, more chaos, or both.

#current events#politics#russian politics#psychology#sociology#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#russia#yevgeny prigozhin#vladimir putin#wagner group

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

Germany: we can't give Ukraine our Leopard 2 tanks because uuuhhh we have to ask NATO first.

Poland: we asked and NATO says you're a poser bitch.

Germany:

Lithuania: bitch.

Estonia: bitch.

Latvia: bitch.

Romania: bitch.

Slovenia: bitch.

Czechia: bitch.

Canada: bitch.

UK: bitch.

US: bitch.

Turkey, actively selling NATO equipment: bitch.

#ukraine#the great russian humiliation of 2022#russian invasion of ukraine#russo ukraine war#russo ukrainian war#nato#bruh we fucking see you#YOU TOO ERDOGAN#france staying suspiciously quiet

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

A developer of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. was killed in action near Bakhmut, Ukraine.

youtube

Rest in peace fellow nerd 😢

7 notes

·

View notes