#ōe

Text

Juzo Itami

- A Quiet Life

1995

#Juzo Itami#Jûzô Itami#A Quiet Life#静かな生活#伊丹十三#Japanese Film#1995#Kenzaburo Oe#Kenzaburō Ōe#島本美知子#大江健三郎

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Nobel prize-winning novelist and essayist Kenzaburō Ōe, who has died aged 88, made his name as a cult author for Japan’s rebellious postwar youth. His early fiction – titles such as Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids (1958), Seventeen (1961) and J (1963), peopled with juvenile delinquents, political fanatics and subway perverts – gave voice to an alienated generation who witnessed the collapse of their parents’ values with the defeat of the second world war. His wartime childhood fed a lifelong pacifism, and his scourging of resurgent militarism and consumerism. Yet his decisive rebirth as a writer came through fatherhood.

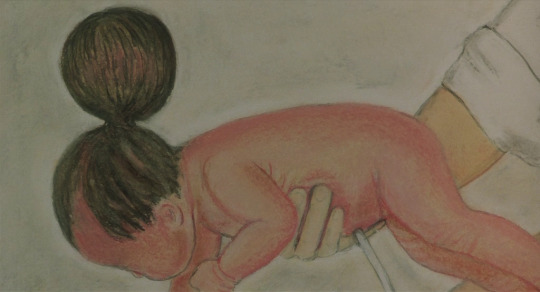

When Ōe was 28, his first child, Hikari, was born with a herniated brain protruding from his skull. Surgery risked brain damage, and doctors urged Ōe and his wife, Yukari, to let the infant die – a “disgraceful” time, he later wrote, that “no powerful detergent” could expunge. Then also working as a journalist, Ōe fled to report on a peace rally in Hiroshima. His encounters with hibakusha (atomic-bomb survivors) and doctors there convinced him his son must live – a moment he saw as a “conversion”. As he told me in Tokyo just after his 70th birthday “I was trained as a writer and as a human being by the birth of my son.”

The imaginative link between his stricken son and the survivors of nuclear fallout and military aggression – the personal and the political – is Ōe’s most profound literary insight. Intolerance of the weak to the point of euthanasia has historically presaged militarism – in imperial Japan as in Nazi Germany. Ōe’s lifelong commitment to Hikari (nicknamed “Pooh” after AA Milne’s bear) inspired a unique cycle of fiction whose protagonists are fathers of brain-damaged sons – often named Eeyore – and pervades his literary vision.

His conversion was reflected in a volume of essays, Hiroshima Notes (1965), and the novel A Personal Matter (1964), whose antihero Bird takes refuge in alcohol and adultery until he resolves to rescue his newborn “two-headed monster”. Its translator John Nathan thought it the “most passionate and original and funniest and saddest Japanese book I had ever read”. Ōe’s masterpiece, The Silent Cry, in which the narrator and his violently rebellious brother (both facets of the author) clash over family history, was published in 1967. These novels, published in English translation in, respectively, 1969 and 1988, brought Ōe the international recognition that culminated in the 1989 Prix Europalia and 1994 Nobel prize for literature.

His Nobel lecture, Japan, the Ambiguous and Myself, was a rejoinder to the 1968 Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata, who had lectured on Japan, the Beautiful and Myself. Ōe spoke of a Japan, after its “cataclysmic” 19th-century modernisation drive, vacillating between Europe and Asia, western modernity and tradition, aggression and human decency – a polarisation he felt as a “deep scar” from which he wrote to free himself.

The novelist Kazuo Ishiguro told me Ōe was “fascinated by what’s not been said” about Japan’s wartime past. Believing the writer’s role to be akin to a canary in a coalmine, he assailed that reticence head on. “Did the Japanese really learn anything from the defeat of 1945?” he wrote in a 50th anniversary foreword to Hiroshima Notes. Although nuclear atrocity, and the drive to rebuild Japan as a cold-war ally, encouraged a sense of victimhood, one of the neglected lessons, for Ōe, was that his parents’ generation were not just victims but aggressors in Asia.

Ōe was born in Ose, a remote mountain village of Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands. His father was killed in 1944, and his mother saw a flash in the sky when far-off Hiroshima was bombed. Ōe was 10 when Emperor Hirohito surrendered in 1945 and robbed Ōe’s generation of their innocence. All that had seemed true became a lie. Fear and relief as US jeeps rolled in with the allied occupation of 1945-52 created a lasting ambivalence. Ōe, who later campaigned against US military bases in Okinawa, said: “I admired and respected English-speaking culture, but resented the occupation.”

His family were driven out of their banknote-paper business by currency reform. At Tokyo University in 1954-59, where he studied French, his country accent made Ōe feel an outsider, but a 1957 novella (translated as Prize Stock in the collection Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness), in which a boy’s friendship with a black American PoW is destroyed by war, won him the Akutagawa prize for best debut, at 23. Inspired by Rabelais’ grotesque realism, Sartre’s existentialism and an American tradition from Huckleberry Finn to Catcher in the Rye, he created antiheroes who courted disgrace in their disgust at civilisation. His assault on traditional values extended to the Japanese language. Nathan noted a “fine line between artful rebellion and mere unruliness”.

At his home in a quiet Tokyo suburb, visitors could not fail to be struck by his humility and self-deprecating humour. As he amiably recounted meeting Chairman Mao in Beijing in 1960, with his “Giant Panda cigarettes”, Ōe mimed smoking them with relish. Just as striking was his devotion to family. He married Yukari, the daughter of the prewar film director Mansaku Itami, in 1960, and Hikari, the first of their three children, was born in 1963. Although Hikari’s condition circumscribed his father’s life, it also enlarged it. It was through their relationship that Ōe grasped the “role of the weak in helping avoid the horrors of war” (the subject of a fictitious musical) and the “wondrous healing power of art”.

Hikari’s rare talent for identifying birdsong was spotted when he was six. Despite autism, visual impairment, epilepsy and learning disabilities, he had perfect pitch and became a renowned composer – the joint subject of Lindsley Cameron’s book on father and son, The Music of Light (1998). Yet in novels by Ōe such as Rouse Up, O Young Men of the New Age! (1983) – the title from William Blake – it is not Eeyore’s talent that is redemptive but the innocence he incarnates. Confronting parental ambivalence about the maturing sexuality of their children, that novel reveals fear of the vulnerable to be a projection of the darkness within ourselves.

Ōe’s post-Nobel novels could be large and, for some, unwieldy. The doomsday cult in Somersault (1999) resembled Aum Shinrikyo, perpetrators of the 1995 Tokyo subway gas attack, but the trauma of an apocalyptic leader renouncing his twisted faith harked back to the war. The Changeling (2000) fictionalised Ōe’s friendship with Juzo Itami (his wife’s brother). The director of the cult comedy Tampopo (1985), and a 1995 film adaptation of Ōe’s novel A Quiet Life (1990), Juzo died after falling from the roof of his office building in 1997, five years after his face was slashed by yakuza gangsters whom he had ridiculed on screen. In Death By Water (2009), Ōe’s alter-ego Kogito (the name a wry nod to Descartes) strives to write a novel about his father’s death.

Yet it is for the “idiot son” cycle that Ōe may most vividly be remembered. “I believe in tolerance,” Ōe said, and how the innocent “can play a role in fighting against violence”. After 1945, he felt strongly, Japan should have “stood up with the weak … the weak are a value in themselves.”

He is survived by Yukari, and their children, Hikari, another son, Sakurao, and a daughter, Natsumiko.

🔔 Kenzaburō Ōe, writer, born 31 January 1935; died 3 March 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You’re right about this being limited to me, it’s entirely a personal matter. But with some personal experiences that lead you way into a cave all by yourself, you must eventually come to a side tunnel or something opens on a truth that concerns not just yourself but everyone. And with that kind of experience at least the individual is rewarded for his suffering. Like Tom Sawyer! He had to suffer in a pitch-black cave, but at the same time he found his way out into the light he also found a bag of gold! But what I’m experiencing personally now is like digging a vertical mine shaft in isolation; it goes straight down to a hopeless depth and never opens on anybody else’s world. So I can sweat and suffer in that same dark cave and my personal experience won’t result in so much as a fragment of significance for anybody else. Hole-digging is all I’m doing, futile, shameful hole-digging; my Tom Sawyer is at the bottom of a desperately deep mine shaft and I wouldn’t be surprised if he went mad!"

― Kenzaburō Ōe, A Personal Matter

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cent’anni

trascorsi

avendo i fiori come casa.

Questo mondo

era davvero il sogno d’una farfalla.

Ōe no Masafusa

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

„I’m the one who’d like to send a telegram, AM RATHER IN TROUBLE—but addressed to whom?“

Kenzaburō Ōe, A Personal Matter

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Death cuts abruptly the warp of understanding. There are things which the survivors are never told. And the survivors have a steadily deepening suspicion that it is precisely because of the things incapable of communication that the deceased has chosen death. The factors that remain ill defined may sometimes lead a survivor to the very site of the disaster, but even then the only thing clear to anyone concerned is that he has been brought up against something incomprehensible.

The Silent Cry by Kenzaburō Ōe

0 notes

Text

get peachy

dal han. 한달

lee ‘sol’ soyi. 이서이

chorong mai. 마이초롱

ōe rie. 大江理恵

machi ‘namra’ na. 나남라

tian ming. 田明

lucky hour

roman ‘romyoung’ jo. 조롬영

baek gowon. 백고원

hong ‘jey’ jeyeol. 홍제열

manor

nang reheon. 낭레헌

romeo ‘ryurae’ jo. 조류래

jang haseul. 장하슬

the eve

cherry theory

nowhere girls

plum. 프럼

deer. 디어

ego. 이고

don’t know what to do with them yet

mischa ‘doona’ yang. 양두나

bae sohee. 배소히

nang jaehyeon. 낭재현

nang ruhyeon. 낭루현

#names#mischa ‘doona’ yang.#lee ‘sol’ soyi.#chorong mai.#ōe rie.#roman ‘romyoung’ jo.#baek gowon.#hong ‘jey’ jeyeol.#dal han.#romeo ‘ryurae’ jo.#choi sohee.#machi ‘namra’ na.#tian ming.#nang reheon.#nang jaehyeon.#nang ruhyeon.#jang haseul.#plum.#deer.#ego.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Shiodome: I can make Takeshiba moan like a girl

Oosaki: *looks up from the corpse to stare at him*

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rozkosze złego smaku

Czyli jak błagamy, żeby zrobić z nas idiotów, po czym klaszczemy i jak głupcy się cieszymy.

Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#365 dni#Abdulrazak Gurnah#Blanka Lipińska#dobry gust#Dorota Kotas#gust#Hiromix#Hiroshi Sugimoto#klasa społeczna#klasy społeczne#klasyfikacja#kultura#kultura niska#kultura wysoka#Lipińska#Motojirō Kajii#Ōe Kenzaburō#Olga Tokarczuk#Pierre Bourdieu#promocja złego gustu#promocja złego smaku#przemyślenia#smak#socjologia#społeczeństwo#Tokihiro Sato#zły gust#zły smak

1 note

·

View note

Text

Juzo Itami

- A Quiet Life

1995

#Juzo Itami#Jûzô Itami#A Quiet Life#静かな生活#伊丹十三#Japanese Film#1995#Kenzaburo Oe#Kenzaburō Ōe#渡部篤郎#Atsuro Watabe#Hinako Saeki#佐伯日菜子#大江健三郎

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kenzaburō Ōe, “The Silent Cry: A Novel”, 1967.

Kenzaburō Ōe, “The Silent Cry: A Novel”, 1967.

Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972) 川端 康成 “The Old Capital” 古都 , 1987 was a Japanese novel by the Nobel laureate; and, was the topic of an earlier blog post.

Here I present: Kenzaburo Oe, “The Silent Cry”, 1967 which was a Japanese novel by the Nobel laureate.

The book consists of thirteen (13 unnumbered) chapters, that have titles. The “table of contents” of the book is shown BELOW.

The first…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

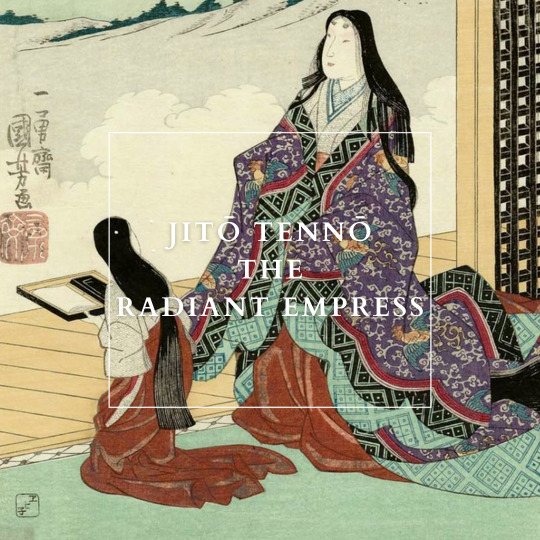

Japan's third empress regnant, Empress Jitō (645-703) was a powerful and effective ruler. Shrewd, bold and clever, she walked in the footsteps of empresses Suiko and Saimei and prevailed against all odds.

A troubled youth

Jitō was the daughter of Prince Naka no Ōe, the son of empress regnant Saimei. The year she was born, her father killed a minister in front of his mother, leading to her abdication.

Jitō’s maternal grandfather committed suicide three years later, having been wrongly accused of plotting against Prince Naka no Ōe. Jitō’s mother, Ochi, died of grief. Jitō was thus placed in her grandmother's care and raised by the former empress.

At age 12, she was married to her paternal uncle, Prince Ōama, who was 27. Jitō was a reserved person with a brilliant intelligence and much liked by the court. She was curious, open-minded and studied Chinese literature. The death of her grandmother in 661 pained her greatly. In 662, Jitō gave birth to her only child: prince Kusakabe. Her father then ascended took the throne as Emperor Tenji in 667.

Succession struggle

The question of Emperor Tenji’s succession soon arose. The sovereign favored Jitō’s half-brother, Prince Ōtomo, but Prince Ōama had his own ambitions. He and Jitō left the court, waiting for an opportunity to strike.

Ōtomo indeed succeeded Tenji, but Ōama revolted against him soon after with Jitō's support. When they arrived at Ise province, she dressed in male clothes and personally addressed the troops. She also worked on tactical plans. As Ōama left to leave an offensive in Ōmi province, Jitō took command of the troops stationed at Ise. She had indeed volunteered to defend the shrine dedicated to the sun Goddess, Amaterasu.

Their joint efforts led to their success. Ōama ascended the throne in 673 as emperor Tenmu, with Jitō becoming his co-ruler.

The radiant empress

Jitō was very influential in court matters. This was reflected in the choice of Tenmu's heir. He could have chosen his son by another woman, Prince Ōtsu, as his heir, but chose Jitō’s son, Prince Kusakabe, instead.

As Tenmu died in 686, Jitō took the matter in hand. She declared Ōtsu guilty of treason and forced him to commit suicide. She then organized grandiose funerals for her husband and wrote poems expressing her grief.

Oh, the autumn foliage

Of the hill of Kamioka!

My good Lord and Sovereign

Would see it in the evening

And ask of it in the morning.

On that very hill from afar

I gaze, wondering

If he sees it to-day,

Or asks of it to-morrow.

Sadness I feel at eve,

And heart-rending grief at morn—

The sleeves of my coarse-cloth robe

Are never for a moment dry.

Her son died in 689. Since her grandson was too young to rule, Jitō became empress regnant.

She reformed the country, establishing a strong central power and surrounded herself with capable ministers. In 689, she enacted a mandatory code for all local governors. In 690, she launched a population census.

She reformed the army, improving the recruitment conditions and the troops' training. A protector of the arts, she also actively participated in the propagation of Buddhism. Poetry became more refined during her reign. One of her poems was later included in the popular Hyakunin Isshu anthology:

The spring has passed

And the summer come again

For the silk-white robes

So they say, are spread to dry

On Mount Kaguyama

Jitō made her predecessors' objective of replacing the tribal system with a strong central power a reality. Her rule was synonymous with a degree of stability that neither her father nor husband were able to reach. She can be regarded as one of the true founders of Japan’s imperial monarchy. The empress was also fond of travels. In 692, she undertook a trip symbolic trip to Ise province, strengthening her authority and gaining the support of the local people.

The empress indeed took advantage of the Shinto rituals and the image of the sun Goddess to reinforce her legitimacy and used the links between the deity and the imperial family. Such was her prestige that Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, one of the greatest poets of his time, compared her to a goddess.

The retired empress

Jitō’s grandson, Monmu (r. 697-707) was ready to take the throne. She stepped back as Daijō Tennō (or “retired emperor”), becoming the first sovereign in Japanese history to assume this title. The power was in reality still in her hands. The Taihō Code was promulgated in 701, reforming governmental administration as well as administrative and penal law. This was only made possible by the reforms enacted during her reign.

In 702, she went through another tour of inspection of the eastern provinces and bestowed gifts and court ranks on the local officials and leading farmers. Jitō died in the first month 703 and her ashes were interred in her husband's tomb.

Here's is the link to my Ko-Fi if you like what I do! Your support would be greatly appreciated.

Further reading:

Aoki Michiko Y., "Jitō Tennō, the female sovereign",in: Mulhern Chieko Irie (ed.), Heroic with grace legendary women of Japan

Souyri Pierre-François, Nouvelle histoire du japon

#history#women in history#women's history#women's history month#japan#japanese history#powerful women#herstory#historyedit#7th century#queens#historyblr#historical figures#japanese prints#japanese art

115 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Katsushika Hokusai, Poem by Gon-chūnagon Masafusa (Ōe no Masafusa), from the series One Hundred Poems Explained by the Nurse (Hyakunin isshu uba ga etoki), 1821

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

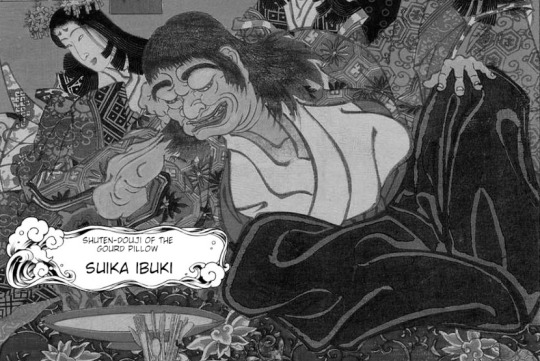

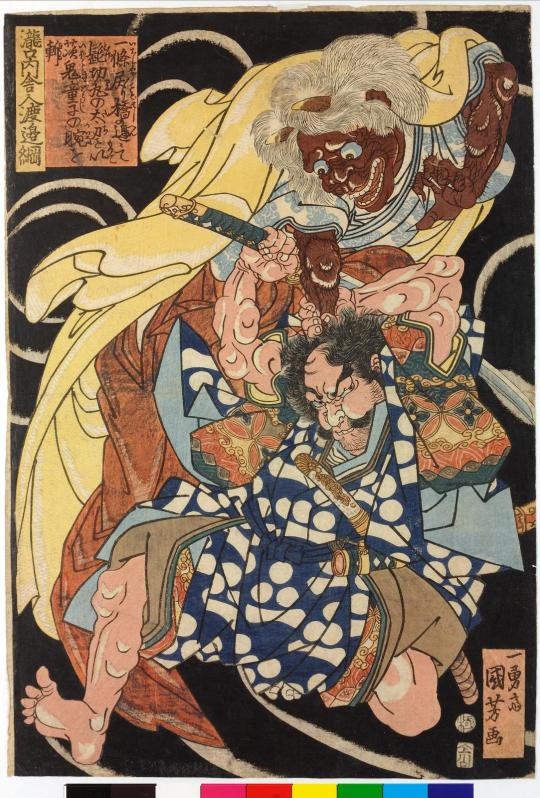

Demon king, demigod, drunkard, dōji: exploring the archetypal oni, from Ōeyama to Lotus Eaters

By popular demand, I wrote an article covering the background of Shuten Dōji and his underlings, and how it influenced Suika’s character and the idea of the Four Devas of the Mountain in Touhou. It was initially scheduled for last month, but I’ve experienced unplanned delays.

Read on to learn if you want to learn what Suika has to do with Yamata no Orochi and Mara, if it’s true that oni never lie, and more. I will also explain why making your own fourth Deva of the Mountain is entirely fair game and anyone telling you otherwise is wrong about the source material which inspired ZUN.

The article contains some spoilers for WaHH and a number of other Touhou installments, so proceed with caution if that might be an issue for you.

Ōeyama, or Shuten Dōji: origins

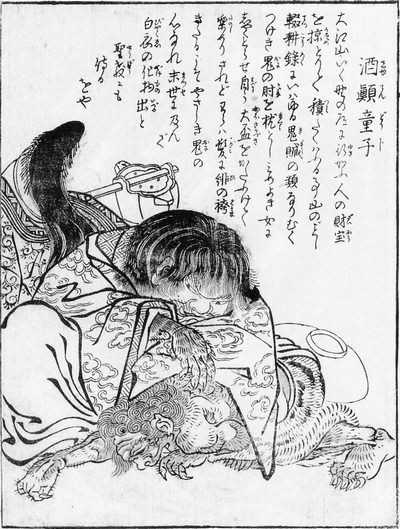

Shuten Dōji, as depicted by Sekien Toriyama in Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki (wikimedia commons)

It perhaps seems a bit silly to start this article with an inquiry into the identity of Shuten Dōji (酒呑童子, “wine-loving youth” or something along these lines). After all, while Touhou characters are often based on obscure figures, Suika is hardly an example of that category. Shuten Dōji is arguably THE archetypal oni, known even to people with limited familiarity with Japanese mythology and folklore. And yet, the matter is nowhere near as clear cut as it might seem at first glance. From a certain point of view, Shuten Dōji might not even exactly be an oni, strictly speaking.

A book from Nara simply titled Ōeyama ("Mt. Ōe") offers a detailed account of Shuten Dōji’s origin. His father was not a man or a demon, but rather a mountain god, Ibuki Daimyōjin (伊吹大明神). That’s not all, though - according to a local belief, Ibuki Daimyōjin was actually Yamata no Orochi. How does that even work? Contrary to the more widespread tradition, the inhabitants of the area around Mt. Ibuki from the Muromachi period onward believed that Orochi survived his confrontation with Susanoo and hid in the mountains.

That’s actually not even the most unusual variant tradition about Orochi. A widespread belief through the middle ages was that he eventually managed to redeem himself, becoming a divine dragon (shinryū, 神龍) residing in the dragon palace under the sea. In that capacity, he was sometimes associated with emperor Antoku, with the latter even claimed to be his reincarnation, for example in a local legend associated with the Atsuta Shrine, preserved in the noh play Kusanagi. In esoteric Buddhist doctrine Orochi was sometimes perceived as a local manifestation (suijaku) of the buddha Yakushi - much like Susanoo was.

Ichijō Kaneyoshi in his Nihon shoki sanso (1455–1457) went into yet another direction, presenting the snake as identical with the naga girl from the Lotus Sutra. Apparently, he specifically means the version of her from Shaku Nihongi… who is identified there as Susanoo’s wife, down to being equated with Kushinadahime (this was not unusual in itself - Susanoo was equated with Gozu Tennō based on similar character, so it was sensible for their wives to be seen as analogous). This effectively created a scenario where Susanoo married his nemesis.

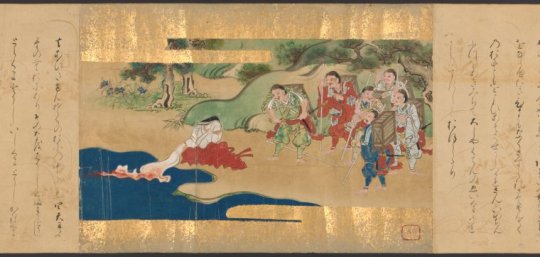

A Japanese depiction of the naga girl offering a jewel to the Buddha, as described in the Lotus Sutra (wikimedia commons)

Anyway, back to Shuten Dōji. According to Ōeyama, Ibuki Daimyōjin, before he even came to be known under this name, fell in love with the daughter of a local feudal lord, Sugawa. He started visiting her at night and she as a result eventually became pregnant. The identity of the visitor was unknown to her father, and out of frustration and fear that nefarious supernatural forces might be involved he eventually contacted various religious officials to perform exorcisms. Needless to say, Ibuki Daimyōjin was less than thrilled, and decided to display his divine wrath through rather conventional means: Sugawa was struck by illness. He once again summoned various Buddhist monks and onmyoji, this time to attempt to heal him. They concluded that the disease will disappear if the deity who caused it is properly honored, and established formal worship of Ibuki Daimyōjin, which apparently did indeed help.

Sugawa’s daughter eventually gave birth to Ibuki Daimyōjin’s child. The child started to cause problems at the age of three: his love of alcohol manifested for the first time, earning him the moniker of Shuten Dōji. By the time he was ten, his misdeeds were too much for his family to bear with and his grandfather decided to send him to Mt. Hiei to become a novice (chigo). The monastic lifestyle didn’t really change much though, and Shuten Dōji continued to drink. Eventually he managed to convince three thousand monks (sic) to drink with him and to join him in an “oni dance” during which everyone put on masks representing demons. The festivities lasted seven days. When Shuten Dōji woke up afterwards, he realized his mask had fused with his face, and he was no longer able to take it off. The other participants fled out of fear of his new form.

Shuten Dōji’s Mt. Hiei career was subsequently cut short by Saichō, the founder of the Tendai school of Buddhism. After learning what happened, he prayed to the buddha Yakushi and to Mt. Hiei’s protective deity Sannō Gongen to banish Shuten Dōji. It's worth pointing out that presenting young Shuten Dōji and Saichō as contemporaries is basically standard, and pops up in multiple legends. There are variants where Kūkai, the founder of Shingon, plays a similar role instead, to. They actually lived some 200 years before the other historical figures who appear in Shuten Dōji narratives, but this is not an oversight. It is a given that a partially divine being would live for much longer than a human.

A Heian period portrait of Saichō (wikimedia commons)

As a result of Saichō’s success, Shuten Dōji had to flee. He tried to return to his grandfather’s residence, but this was no longer an option for him. He temporarily hid on Mt. Ibuki, but eventually left for Mt. Ōe, where he finally became a veritable "demon king".

The reason why Shuten Dōji was rejected by his family is that he was recognized as an “oni child” (鬼子, onigo). In the folkloric sense, this term refers to supernatural beings which are nonetheless partially human by birth. Not necessarily part oni, though. Another well known onigo, Sakata no Kintoki, was the son of a yamauba, for instance.

However, Yanagita Kunio noted that this term also referred to children born with teeth (a real, though very uncommon phenomenon), who were believed to turn into oni - much like how Shuten Dōji did. He states that especially before the Edo period this lead to cases of child abuse or outright murder. In some cases sending the child to become a member of Buddhist clergy was seen as a remedy. For example, a twelfth century monk named Jōjin in a letter relays that he suggested this to the mother of such a newborn. It is not hard to see that Ōeyama likely consciously references this custom.

The other origin of Shuten Dōji

Yet another tradition is preserved in a variant of the standard Shuten Dōji tale which switches the location of his demise from Mt. Ōe to Mt. Ibuki: here Shuten Dōji is not just any demon, but a manifestation of Mara. As in, the opponent of the Buddha and demon king of the sixth heaven, not some other accidentally similarly named figure.

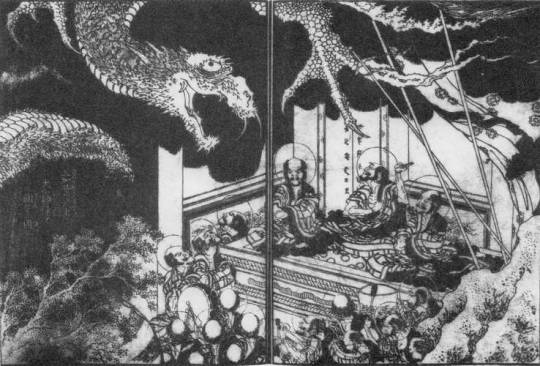

Mara, as depicted by Hokusai in Shaka-goichidai-zue (wikimedia commons)

It is presumed that this portrayal of Shuten Dōji might be tied to medieval Japanese traditions pertaining to Mara. They might sound unusual today: he was both a “demon king” (魔王) obstructing enlightenment, as expected, but also a jinushi (地主), or “landholder deity”. From the Buddhist point of view, jinushi were ambivalent figures: on one hand, their presence was responsible for bestowing specific locations with holiness. On the other hand, they could resist Buddhism as demonic forces, and had to be subjugated or converted to prevent that. Mara was the ultimate jinushi, the king of the world as a whole. A role already attributed to him in earlier Buddhist sources was basically adjusted for this framework.

The jinushi version of Mara originated among proponents of the imperial court and mainstream Buddhist institutions, but it curiously also gained traction among the opponents of these structures. Mara became somewhat of an anti-establishment icon more than once, essentially. A legend links him with (in)famous rebel Taira no Masakado (who you may know from SMT) for this reason.

Masakado, as depicted by Kunichika Toyohara in Sen Taiheiki Gigokuden (wikimedia commons)

Other similar examples are also known. A local legendary figure from the Tsugaru peninsula in modern Aomori prefecture, Tsugaru Andō (津軽安藤), who after a failed rebellion fled to Hokkaido, was proudly described as a vassal of Mara by local officials who claimed descent from him. Prince Sutoku, a banished opponent of emperor Go-Shirakawa, swore a vow to become like Mara. Oda Nobunaga famously referring to himself as the “demon king of the sixth heaven” in a letter to Takeda Shingen is likely another example.

Reportedly a related belief that praying to the jinushi version of Mara can spare one from conscription persisted as late as the early 20th century, though generally he belongs to the realm of “medieval myths” which faded with the ascent of a new system of values in the Meiji period, in which the early imperial chronicles were favored. Even though it is largely forgotten today outside of specialized scholarship, there is much more to this Mara tradition. It led to the development of one of my favorite Japanese myths with no popcultural reception, but you will have no wait a few more weeks to learn more.

It has been argued that behind the identification of Shuten Dōji and Mara might reflect a historical event of the sort which led to associating the latter with figures such as Masakado. In other words, that Shuten Dōji in this case might be less a demon and more a demonized form of some opponent of imperial or religious authorities.

It has been argued that the Ibuki version was the result of combining an original oral narrative, a precursor of the textual versions we are familiar with today, with the memory of the death of a certain Kashiwabara Yasaburō, a bandit leader, in 1201. It has in fact been argued that even the mt. Ōe version might simply be a particularly fabulous reinterpretation of a punitive mission against bandits robbing and murdering travelers. Such rationalist explanations are not exactly new - Ekken Kaibara already argued in the Edo period that the legend of Shuten Dōji must have been the reflection of the downfall of a real bandit who perhaps wore the mask of an oni while committing robberies.

It’s important to bear in mind to not go overboard with this speculation, though. Ultimately the Mt. Ibuki version has a more pronounced religious character than other variants in general: Shuten Dōji’s nemesis Raikō’s is identified as a manifestation Bishamonten or Daiitoku Myōō (in the latter case, Bishamonten and the three other heavenly kings correspond to his four retainers), emperor Ichijō with Miroku (Maitreya), and Abe no Seimei, who plays a minor role in vanquishing the demon, with Kannon.

These equations reflect the idea of honji, or “true nature” of Buddhist figures, who were believed to take various guises through history to help people reach nirvana, for example these of local deities or historical figures. The best known example of application of this doctrine in Japanese Buddhism is obviously the historical phenomenon of honji suijaku, which was focused specifically on kami.

A Kasuga mandala representing the correspondences between Buddhist figures and local kami (source; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The legend of Shuten Dōji

Regardless of which mountain is identified as the residence of oni, and of whether the dramatis personae are identified with Buddhist figures or not, the plot of the various versions of the legend of Shuten Dōji surprisingly does not vary all that much. While it is reasonably well known, I figured it won’t hurt to summarize it here anyway, especially since the information above should make it possible to view it from many new angles.

The oldest surviving version, Ōeyama Ekotoba (“Illustrations and Writing of Mt. Ōe”), presumably based on preexisting oral sources, comes from the fourteenth century, specifically from the Nanbokuchō period. However, the story only reached the peak of its popularity a few centuries later, in the Edo period. This was a part of a broader phenomenon: preexisting tales about warriors matched the sensibilities of the new ruling classes and were kept in circulation by them, but eventually they also became a part of urban popular culture. Many adaptations were produced, including noh plays and ukiyo-e. To put it very colloquially, the heroic warriors and demon quellers from the previous periods became the Edo period counterpart of contemporary superhero media. This is a genuine comparison employed in scholars, for clarity, not a joke.

As remarked by Bernard Faure, the most widespread version is basically framed as if it was a tabloid story from the Heian period. In 995, young women (and in some versions men too) disappear whenever a particularly violent storm occurs, and nobody knows how to stop it. Not even the power of Buddhist exorcisms is enough. Seeing as in the portrayed time period that was pretty much the universal solution to supernatural problems, this is a big deal.

Abe no Seimei (right) in the Fudo Rieki Engi (wikimedia commons)

This is a source of distress for a certain official, Ikeda Kunikata (or, in some version, Kunitaka), whose only daughter is among the kidnapped women. He decides to seek the help of the Heian period superstar Abe no Seimei, arguably the most famous onmyoji in history. Alternatively, the expert contacted is a certain Muraoka no Masatoki, who to my best knowledge is a fictional character and doesn’t appear anywhere outside of some variants of this tale.

Either way, thanks to this intervention it is possible to identify the culprit as a demonic being residing on Mt. Ōe (or alternatively on Mt. Ibuki). In one of the versions featuring Seimei he specifically identifies him as a tenma (天魔), “heavenly demon” - a term commonly used to refer to tengu (as ZUN does in Touhou) and to servants of Mara (overlapping if not identical categories, really; stay tuned for a future article exploring this).

However, onmyoji arts are not enough to stop the crisis; all Seimei can guarantee is that Kunikata’s daughter will survive, but he has no way to confront the demon directly. Kunikata therefore decides to bring the case to the attention of the emperor, Ichijō. He holds a meeting with various ministers, who note that in the past a similar case was solved by Kūkai (recall his already mentioned association with Shuten Dōji). However, there are no monks of equal skill left, so his feat cannot be repeated.

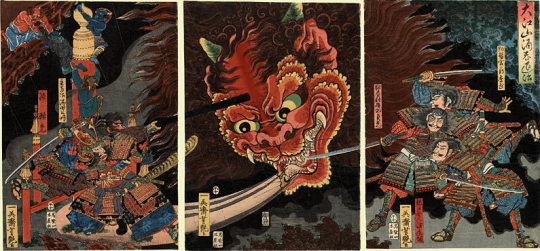

It is then concluded that the only way to end the demon’s reign of terror it is to send the strongest warrior they were aware of, Minamoto no Yorimitsu (Raikō) and his four retainers, Watanabe no Tsuna, Sakata no Kintoki, Taira no Suetake, and Tairi no Sadamitsu, on a mission to kill him. Raikō is also assisted by Fujiwara no Yasumasa (Hōshō) and his anonymous attendant, but these two never gained much prominence as characters in this narrative. Additionally, in some versions other figures from the same period - Taira no Muneyori, Minamoto no Yorinobu (Raikō’s younger brother) and Taira no Korehira - are namedropped as potential candidates considered by the emperor, but they all reportedly decline to partake out of fear.

Raikō and Kintoki, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

Preparations started with prayers in Sumiyoshi, Kumano, Kasuga and, in some versions, Hie shrines. They did not go unanswered. Raikō and his retainers subsequently encounter a group of shugenja (mountain ascetics) who turn out to be the manifestations of the deities they paid honor to: Sumiyoshi Myōjin, Kumano Nachi Gongen, Hachiman (here addressed as a bodhisattva) and, if the Hie shrine is included in a given version, Sannō Gongen. They explained that to safely enter the fortress of Shuten Dōji, Raikō and his men must disguise themselves as shugenja (that’s because the legendary first shugenja, En no Gyōja, famously had an entourage of demons). They also provide him with supernatural wine. They state the oni will inevitably drink it due to their fondness of alcohol, only to end up poisoned as a result. In some versions they vanish afterwards, but in others they continue to accompany Raikō.

The protagonists then encounter a woman washing blood stained clothes. In some versions she is described as elderly, and states she has lived for 200 years as a servant of Shuten Dōji. In the most widespread Edo period version, she is young and says she was only kidnapped a year earlier, though.

Encounter with the woman washing bloody clothes (NYPL Digital Collections)

Regardless of her age, she reveals some additional information about Shuten Dōji, though that also varies depending on the version. In some, she explains that he looks like a human during the day, but takes the form of an oni at night. His human form is specifically that of a dōji, literally “child”, but we’ll get back to the full context of this term later. In any case, I think it's safe to say the shape and size changing is where Suika'a ability came from.

In another variant, the woman warns the heroes that Shuten Dōji is enraged by Abe no Seimei’s actions, as the onymoji apparently figured out in the meanwhile how to keep the people of Kyoto safe by employing a number of shikigami (a standard part of his repertoire).

There are no further stops on the journey, and shortly after the encounter with the woman of variable age Raikō and his men enter the mountainous land of the oni. Especially in the older versions, it’s a place completely out of this world, with all four seasons occurring at once. Once they enter the fortress located there, they instantly encounter Shuten Dōji… and ask him for a place to stay for the night.

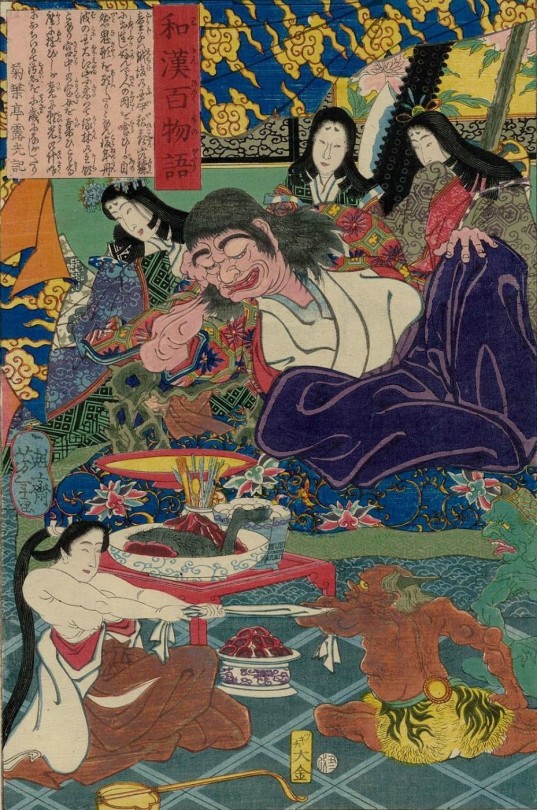

Distinctly human-like Shuten Dōji, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka in One Hundred Ghost Stories from China and Japan (LACMA; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Rather unexpectedly, he instantly agrees. He then tells them about his past; this largely a shorter version of the legend already discussed earlier, though with nothing predating the Mt. Hiei section mentioned. We also get a specific date for his arrival on Mt. Ōe, 849. This doesn’t last long, though, and soon he invites the protagonists to partake in a feast with him. This is obviously not a regular party, and while the individual versions can be more or less graphic, it is clear that the oni are consuing the flesh and blood of their captives.

Despite various horrific sights, Raikō maintains composure. He uses the opportunity the feast presents him with to offer Shuten Dōji the sake he received from the three (or four) deities earlier. As expected, Shuten Dōji gets drunk, and leaves to rest in his chamber.

The other oni continue to party. In some versions, some of them try to approach the protagonists by disguising themselves either as a group of courtly ladies or as a dengaku troupe, but Raikō’s glare is so intense they quickly relent. Eventually all of the oni give up on attempting to engage with the alleged ascetics and end up drunk.

That’s when the heroes decide to free their captives. These obviously include the women from Kyoto. However, as it turns out, Shuten Dōji’s rampages actually extended beyond Japan, to India and China, though only captives from the latter area actually appear. Multiple versions additionally mention that one of the prisoners was a young acolyte of the Tendai abbot Ryōgen, who was protected by assorted deities. This doesn’t really come into play in any meaningful way, though. Once everyone is freed, the heroes draw their weapons and enter Shuten Dōji’s chamber.

Sleeping Shuten Dōji (National Museum of Asian Art; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The protagonists finally witness Shuten Dōji's oni form. He is five jō (around fifteen meters) tall, has fifteen eyes and five horns. His head and torso are red, his right arm is yellow, his left arm is blue, his right leg is white and his left leg is black. This might be a reference to the five elements. Alternatively, he could be described as entirely red, which might either be yet another way to reference his love of alcohol, as in the case of the shōjō, or an indication he was comparable to a “plague deity” (疫神, ekijin).

The manifestations of the deities from earlier show up again, this time to hold Shuten Dōji in place so that Raikō can strike. He cuts off his head, but to his shock it rises into the air and starts talking.

Confrontation between the heroes and the floating head of , as depicted by Yoshitsuya Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

Shuten Dōji actually mocks the heroes: “How sad, you priests! You said you do not lie. There is nothing false in the words of demons.” Needless to say, his final words are pretty directly referenced in Touhou. Oni, at the very least, claim they do not lie. Mileage of course varies, though.

ZUN is not the only author drawn to this element of the legend. It would appear that even the Japan Oni Cultural Museum has advertised itself with the words “there is nothing false in the words of demons” in the past. As noted by Noriko T. Reider, emphasizing this apparent honesty (or naivete) sometimes serves as a way to make oni sympathetic or even relatable for modern audiences.

However, it's worth noting that in the noh version, Raikō pushes back against Shuten Dōji’s words, and points out even the claim oni do not lie is a lie. He has a point, considering some versions outright establish oni capture their victims by disguising themselves as people close to them, imitating their voices. It probably also should be pointed out that in Konjaku Monogatari, oni are said to be scary precisely because they can tell apart right and wrong.

Anyway, oni ethics aside, it turns out that to kill Shuten Dōji for good, one has to gouge out his eyes. Once that is accomplished, Raikō's mission is finally complete. After killing the other oni, the protagonists take the head with them to Kyoto. Obviously, they also take the freed captives with them. The young women return to their families, and the Chinese men head for the coast to find a ship which could take them home. They promise to let the emperor (the Chinese one, for clarity; that would be Zhenzong of Song in 995) about Raikō's heroism.

In the versions where the woman washing clothes was elderly, rather than simply one of the young captives, on the way back the protagonists learn that she has passed away in the meanwhile, since her lifespan was unnaturally extended by Shuten Dōji. Once he died, so did she.

Transport of Shuten Dōji's head to Kyoto (NYPL Digital Collections)

Before the head can enter the capital, a purification ritual has been performed. Abe no Seimei thankfully knows how to do that. Thanks to him, all the relevant authorities can examine it. The emperor decides it will be best to store it in the treasure house of Uji. This location pops up in multiple legends. The severed heads of the two other equally famous malign entities, Ōtakemaru and Tamamo no Mae, were also stored there according to legends focused on them, in addition to various Buddhist relics and mundane treasures.

In an alternate version, the head never reaches the imperial court. Raikō and his retainers encounter the bodhisattva Jizou, who tells them it is too impure to be shown to the emperor, and suggests burying it. The location selected, a hill on the northwestern limits of the city, came to be known as Kubizuka (首塚), literally “head tumulus”. Shuten Dōji actually came to be enshrined there as Kubizuka Daimyōjin (首塚大明神), and in this divine guise developed an association with learning and ailments of the head.

The Kubizuka shrine in 2019 (wikimedia commons)

There is yet another variant tradition about the final fate of Shuten Dōji: after his death he became a vengeful spirit, and then turned into a tsuchigumo, just to be defeated by Raikō and his retainer Tsuna for a second time.

Raikō and Tsuna battling tsuchigumo, as depicted in Tsuchigumo no Sōshi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

Interestingly, it has been argued the tale of Shuten Dōji was at least in part based on that of the tsuchigumo Kugamimi no Mikasa (陸耳御笠), who resided on Mt. Ōe according to Tango Fudoki Zanketsu (丹後風土記残欠). The tale is not preserved fully, though, so all we know for sure other than the location is that the hero opposing him was Hikoimasu no Miko (日子坐王), a stepbrother of emperor Sujin (he is also attested in other sources). A second tsuchigumo, Hikime (匹女) is successfully defeated, but the fate of Mikasa is left unspecified in the surviving sections. This obviously makes further comparisons difficult. The topic of tsuchigumo cannot be dealt with here due to space constraints, but I promise I will return to it in a future article.

The supporting cast of Shuten Dōji

Shuten Dōji in his human form and his oni henchmen (NYPL Digital Collections)

Something that requires further discussion is the matter of the underlings of Shuten Dōji, since it is a topic directly relevant to Touhou. You might have noticed I actually avoided referencing them in any meaningful capacity in the summary of the legend. That’s because they actually do not play a major role. There also wasn’t any consistent view regarding their number or names. However, the version which came to be standard in the Edo period lists four of them - an obvious mirror of Raikō and his entourage. As a matter of fact, both groups even share the same moniker, Four Heavenly Kings.

This idea predates the Edo period, though. An earlier variant based on picture scrolls created by Kanō Motonobu already lists four servants of Shuten Dōji: Gogō, Kiriō, Ahō, and Rasetsu (yes, an oni named Rakshasa). However, two additional oni at his service are also listed, Kanakuma Dōji and Ishikuma Dōji. They are described as his personal guards, and as, well, dōji. It is clear the term is used in a literal sense here - they are said to look like “overgrown adolescents”. Two different subordinates are mentioned in another picture scroll: Kirinmugoku (麒麟無極) and Jakengokudai (邪見極大). However, they do not receive any characterization, or even physically appear in the narrative. Shuten Dōji shouts their names when he is about to die, and the very assumption that he’s referring to his oni subordinates is conjectural. The same version states that there were at least ten oni in the fortress so it’s not like it’s an implausible assumption.

The group of four oni returns in the standard Edo period version, where their names are Hoshikuma (“Star-bear”) Dōji, Kuma (“Bear”) Dōji, Torakuma (“Tiger-bear”) Dōji and Kane (“Iron”) Dōji. There’s also a fifth oni who is not a member of the group of 4, but shares the same naming pattern, Ishikuma Dōji. He actually gets a handful of lines, though they do not really provide him with much of a character beyond establishing he likes sake, that he eats humans, and that he is loyal to Shuten Dōji. Kane Dōji also gets a single line… explicitly alongside Ishikuma and multiple other nameless oni, though, and it boils down to announcing they will go down fighting because without their leader they no longer have a place to go.

Defeat of the oni (NYPL Digital Collections)

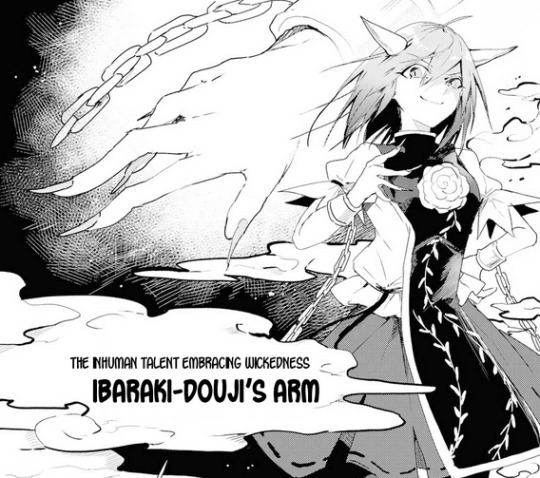

Ibaraki Dōji: Shuten Dōji’s only equal?

Watanabe no Tsuna battling Ibaraki Dōji (wikimedia commons)

A further unique case is that of Ibaraki Dōji, who actually acquired some fame as an individual character, and today is sometimes cited as an example of an oni equally archetypal as Shuten Dōji.

Despite being portrayed as a close associate of Shuten Dōji, Ibaraki Dōji to my best knowledge isn’t counted among the Four Heavenly Kings in any version. The character of the connection is evidently more nebulous. I know an assertion that a tradition presenting Ibaraki Dōji as Shuten Dōji’s wife is attested is repeated as fact on wikipedia and various at least semi-credible websites, but there is never a citation provided, and no version of the narrative covered in articles and monographs I have access to includes such an element. I am not claiming it is impossible, though I do feel the fact it doesn’t come up in any paper or monograph discussing either figure I have access to doesn’t mention to might indicate it’s either a recent reinterpretation or a very obscure local variant. Note this is not meant to be an argument against any Touhou ships.

What I can say with certainty is that Ibaraki Dōji’s gender is actually a matter of occasional academic dispute. In the versions of the basic Shuten Dōji narrative which mention this oni, he is pretty firmly male. However, he is said to be capable of taking the form of a woman. Noriko T. Reider argues that on this basis it can be effectively assumed that at the very least this specific oni can be considered genderless or capable of freely changing their gender, though she tentatively extrapolates this ability to oni in general.

While Ibaraki Dōji’s gender changing adventure is technically its own legend, a reference to it was incorporated into the basic Edo period version of the Shuten Dōji narrative. During the feast, the latter mentions in passing that the former, his trusted ally, lost his arm in a fight with Watanabe no Tsuna during one of their Kyoto raids, after failing to abduct him while disguised as a woman. He clarifies that the arm was later recovered, but not particularly many details are provided.

The rivalry between Tsuna and Ibaraki Dōji subsequently comes into play after Shuten Dōji’s death, when the protagonists are about to exterminate the other oni. Ibaraki charges him and they two fight without a clear winner for a while, until Raikō intervenes and kills the oni. I would argue that despite him being responsible for dealing the killing blow, it is Tsuna who should be considered Ibaraki’s nemesis, though. Interestingly, at some point ZUN considered featuring a character based on him in Wild and Horned Hermit (source). That obviously did not come to pass, though.

Tsuna already fights an oni in Heike Tsuruginomaki, and many other variants of the story were written subsequently, with the noh play Rashōmon being the most famous. Curiously, the oldest version makes no reference to Shuten Dōji, and the oni actually resides on Mt. Atago, but by the Edo period the two were regarded as allies operating from Mt. Ōe.

The details are otherwise generally similar across all of the sources. Raikō sends Tsuna on an errand. He encounters a woman on the Modoribashi Bridge in Kyoto, but as soon as he offers to take her with him she turns into an oni. Thinking quickly, he cuts off the creature’s arm, which is enough to make them flee. He keeps the severed limb as a trophy. Some time later, he is visited by an old woman who he assumes is his aunt... but who turns out to be the same oni, who uses a brief moment of confusion to recover the arm and fly away.

Transformed Ibaraki Dōji, as depicted by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (wikimedia commons)

The legend of Ibaraki Dōji was evidently reasonably popular in the Edo period, and could even be utilized to comedic ends. One example is an Edo period satirical pamphlet, Thousand Arms of Goddess, Julienned: The Secret Recipe of Our Handmade Soup Stock, written by Shiba Zenkō and illustrated by Kitao Masanobu. Here the one-armed Ibaraki Dōji is one of the figures interested in leasing one of the now detached additional arms of the Thousand-Armed Kannon, who has apparently fallen in dire straits (“business slumps are inevitable, even for a Buddha”, comments the narrator, alluding to the financial conditions of the 1780s). As we learn, after making a purchase Ibaraki is disappointed by the lack of hair, and promptly hires a craftsman to add it:

Original translation by Adam L. Kern; reproduced here for educational purposes only. I am not responsible for the typesetting.

In my recent Ten Desires article I’ve already discussed the oni of Rashomon as a character in legends about Yoshika no Miyako, which I won’t repeat here. It will suffice to say that this conflation effectively made Ibaraki a penchant for poetry and fine arts, and that it indirectly put him in the proximity of the pursuit of immortality. Whether this is why ZUN made Ibaraki’s counterpart a wannabe immortal (“hermit”) is difficult to ascertain, but it does not strike me as impossible.

The oni of Rashomon actually appears in at least one more legend which similarly portrays him as an enthusiast of the arts, though to my best knowledge this one never came to be reassigned to Ibaraki Dōji. It is centered on a famous biwa player, Minamoto no Hiromasa, who has to resolve the case of mysterious theft of an instrument from the imperial palace. As you can expect, it is revealed to specifically be an exceptional biwa, which bears the name Genjō. Hiromasa surveys the city in hopes of finding it, and eventually hears its distinct tones while passing near the Rashomon gate. He quickly realizes an oni is playing it. He politely asks if he can have it back, since it’s a treasure of the imperial court… and the oni eagerly obeys, thus bringing the story to a happy end. However, we are told Genjō acquired supernatural qualities in the aftermath of the theft, and only played when it felt like it, as if it was a living being.

There is a variant which reveals that the oni of Rashomon was in fact the ghost of Genjō’s original maker, a craftsman from India. In this version, Abe no Seimei has to intervene to recover it, and the oni only agrees to return it after being promised a night with a woman he fell in love with who resembles his deceased wife. There is no happy ending here, though, as the woman’s brother convinces her she needs to kill the oni. She fails, and meets such a fate herself instead. It seems that the reader’s sympathy is actually supposed to be with the oni in this case.

Conclusions, or why you should make your own Deva of the Mountain

Obviously, there is nothing novel or clever about stating that the two figures this article is focused on, Shuten Dōji and Ibaraki Dōji, correspond to Suika and Kasen respectively. You can learn that from the official media itself, after all. Funnily enough, it seems this might have been even more blunt, judging from unused ideas for referencing the legend to an even greater degree in WaHH, with the defeat at Mt. Ōe as the explanation why oni reside… well, elsewhere (source). Granted, it would also be a disservice to ZUN to say he only created anime girl versions of the classic oni. He effectively created his own versions of both Shuten and Ibaraki - for every similarity between the irl background I’ve described and Touhou, there is also something brand new. That is part of what makes Touhou compelling, I would argue.

Naturally, the fact that the group Kasen and Suika belong to is referred to as the Four Devas of the Mountain shows clear inspiration from the Edo period version of the original legends. However, Suika and Kasen are counted among the four, which is obviously an innovation. Additionally, while Yuugi is naturally named after Hoshikuma Dōji, who you were able to meet earlier, save for the name she is effectively a fully original character. Her ability references the Analects of Confucius, rather than anything directly tied to Shuten Dōji. And, on top of that in all honesty, she has more character than any of the additional oni appearing in the real legends. ZUN, as far as I am concerned, created a more than worthy addition to the classics.

What about the much discussed fourth deva? I think it’s safe to say that in the light of the discussed material there simply isn’t a single most plausible option. As I stressed already, there’s no consistent group of oni appearing alongside Shuten Dōji, and it cannot be said that the Edo period version is clearly what should be treated as true in Touhou. ZUN picked what he liked from many versions.

For what it’s worth, so far all of the oni forming the Four Devas are based on those who share the moniker of dōji, so that’s the closest we have to a theme. As I already said earlier, this term can be simply translated as “child” (or “lad”, though I think a gender neutral option is more apt since we are talking about Touhou here, ultimately). However, it has a more specific meaning when applied to supernatural beings. In this context it refers to a category of ambiguous figures characterized by “vitality, (...) hubris, and (...) unpredictability”, as well as fondness of violence, as summarized by Bernard Faure. Shuten Dōji, and by extension his underlings, are obviously the dōji par excellence. However, the term could also be applied to benevolent, or outright divine beings. That, however, goes beyond the scope of this article.

I personally think despite the possible dōji theme the fourth slot will never be filled, ultimately. ZUN likes leaving gaps in established groups - there are types of tengu which were a part of the background for well over a decade, for instance. I think these are left as paths to make ocs with an instant excuse to interact with canon characters. Despite ZUN’s generally pro-fanwork stance I do not think I’ve ever seen anyone make this point.

As far as I am concerned, the conclusion is clear: it’s entirely fair game to invent characters to fill the empty spot. There’s even a solid case to be made for reinventing oni from other legends as members of the Four Devas - remember that much of Ibaraki Dōji’s character was borrowed from a nameless oni from a legend about the Rashomon gate, as I discussed last month.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Michael Daniel Foster, The Book of Yokai. Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore

Adam L. Kern, Thousand Arms of Goddess, Julienned: The Secret Recipe of Our Handmade Soup Stock, written by Shiba Zenkō and illustrated by Kitao Masanobu (translation and commentary), in: An Edo Anthology: Literature from Japan’s Mega-City, 1750–1850

Keller Kimbrough and Haruo Shirane (eds.), Monsters, Animals, and Other Worlds. A Collection of Short Medieval Japanese Tales

Irene H. Lin, The Ideology of Imagination: The Tale of Shuten Dōji as a Kenmon Discourse

Michelle Osterfeld Li, Human of the Heart: Pitiful Oni in Medieval Japan in: The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous

Noriko T. Reider, Shuten Dōji: "Drunken Demon"

Idem, Japanese Demon Lore

Idem, Seven Demon Stories from Medieval Japan

also check out the scans of an amazing Shuten Dōji picture scroll from the NYPL collection here!

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Squarcia

la notte di quest’effimero

mondo di dolore:

ben invidiabile cosa,

la luna che sorge dai monti.

Ōe no Masafusa

4 notes

·

View notes