Text

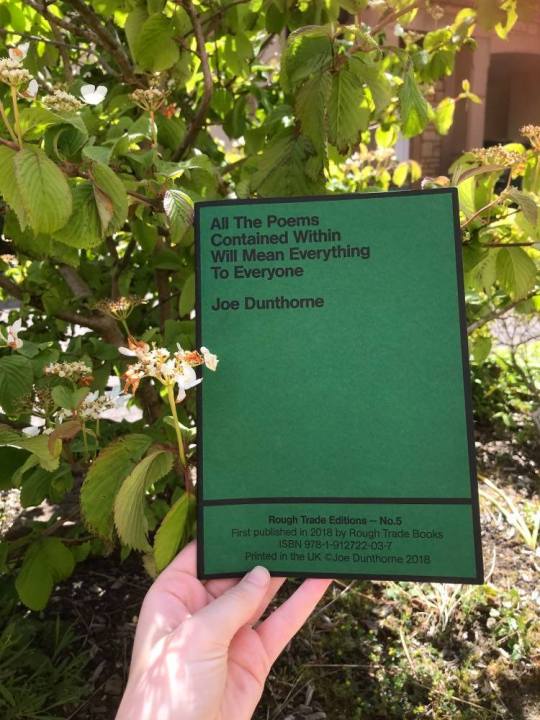

(REVIEW) All The Poems Contained Within Will Mean Everything To Everyone, by Joe Dunthorne

Is it fiction, is it poetry, is it truth — what are the rules here? Kirsty Dunlop tackles the difficult, yet illustrious art of the poet bio in this review of Joe Dunthorne’s All The Poems Contained Within Will Mean Everything To Everyone (Rough Trade Editions, 2018).

Whenever I read a poetry anthology - I hope I’m not the only one - I go to the bios at the back before I read the poems…it’s also a really strange thing when you publish a poem…you brag about yourself in a text that is supposed to sound distant and academic but is actually you carefully calculating how you’ll present yourself.

> It’s the middle of a night in 2019 and I’m listening to a podcast recording from Rough Trade Editions’ first birthday party at the London Review Bookshop, and this is Dunthorne’s intro to the reading from his pamphlet All The Poems Contained Within Will Mean Everything To Everyone (2018). As I lie there in that strange limbo space of my own insomnia, Dunthorne’s side-note to his work feels comfortingly intimate because it rings so true (the kind of thing you might admit to a friend over a drink after a poetry reading rather than in the performative space of the reading itself). Like Joe, and yes surely many others, I am also fascinated by bios - particularly because I find them so awkward to write/it makes me cringe writing my own/this is definitely the kind of thing you overthink late at night. Bios also function as this alternative narrative on the margins of the central creative work and they do tell a story: take any bio out of context and it can be read as a piece of flash fiction. When we are asked to write bios, there is this unspoken expectation that we follow certain rules in our use of language, tone and content. Side note: how weird would it be if we actually spoke about ourselves in this pompous third person perspective irl?! Bios themselves are limbo spaces (another kind of side note!) where there is much left unsaid and often the unsaid and the little that is said reveals a lot. Of course, some bios are also very, very long. Dunthorne’s pamphlet plays with this limbo space as a site of narrative and poetic potential: prior to All The Poems, I had never read a short story actually written through the framework of a list of poet bios. The result is an incredibly funny, honest and playful piece of meta poetic prose that teases out all the subtle aspects of the poet bio-sphere and ever since that first listen, I can’t stop myself re-reading.

> This work is an exciting example of how formal constraints in writing can actually create an exhilarating sense of narrative liberation. I see this really playful, fluid Oulipo quality to the writing, where the process of using the bio as constraint is what makes the rollercoaster reading experience so satisfying as well as revealing a theatrical stage for language to have its fun, where the reality of our own calculated self performance can be teased out bio by bio. The re-reading opens up a new level of comedy each time often at the level of wordplay. I’ll maybe reveal some more of that in a wee bit.

> It’s a winding road that Dunthorne takes us on in his narrative journey where the micro and the macro continually fall inside each other. So perhaps this review will also be quite winding. Here is another entry into the text: we begin reading about the protagonist Adam Lorral from the opening sentence, who we realise fairly quickly is struggling to put together a ground-breaking landmark poetry anthology. His bio crops up repeatedly in varying forms:

‘Adam Lorral, born 1985 is a playwright, translator and the editor-publisher of this anthology.’

‘Adam Lorral is a playwright, translator and the man who, morning after morning, stood barefoot on his front doorstep […]’

‘Adam Lorral is a playwright, translator and someone for whom the date Monday, October 14th, 2017 has enormous meaning. Firstly Adam’s son started smiling.’

The driving circularity of this repetition pushes the narrative onwards, whilst the language is never bogged down: it hopscotches along and we can’t help but join in the game. Amidst a growing list of other characters/poets- that Adam may or may not include in this collection he seems to be pouring/ draining his energy into, with just a little help from his wife’s family money- tension begins to build.

> Although Adam is overtly the protagonist in the story, to my mind it is, in fact, Adam’s four-week-old son who is the real heroic figure. Of course this baby doesn’t have a bio of his own but he does continually creep into Adam’s (he’s another side note!). He comes off as the only genuine character: there is no performance, no judgement, he just is. Adam is continually amazed by his son’s mental and physical development which is far more impressive than the growth of this questionable anthology. The baby is this god-like figure, continually present during Adam’s struggles, with the seemingly small moments of its development taking on monumental significance. Adam might try to immerse himself fully in this creative work but the reality of his family surroundings will constantly interrupt. This self-deprecating, reflective tone led me to think about how Dunthorne expansively explores the idea of the contemporary poet and artist identity through metanarrative. In Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2016), he writes ‘There is embarrassment for the poet – couldn’t you get a real job and put your childish ways behind you?’ In a recent online interview with the poet Will Harris[1], when asked about his own development as a writer, he spoke about how the career trajectory of a poet is a confusing phenomenon and I’ve heard many other poets speak of this too: there are perhaps milestones to pass but they are not rigid or obvious and, of course, they are set apart from the milestones of more ‘adult’, professional pursuits. I think Dunthorne’s short story accurately captures this confusion around artistic, personal and intellectual growth and the navigation of the poetry community, through these minute, telling observations and the rejection of a simplistic narrative linearity. The story doesn’t make any hard or fast judgements: like the character of the baby, the observations just are. Sometimes, it feels like this project could be one of the most important aspects of Adam’s life (it might even make or break it) and we are there with him and at other moments it seems quite irrelevant to the bigger picture, particularly as the bios get more ridiculous. Here, I just have to highlight one of the bios which perfectly evokes this heightened sense of a poet’s importance:

Peter Daniels’ seventh collection The Animatronic Tyrannosaurus of Guadalajara, is forthcoming with Welt Press. He will not let anyone forget that he edited Unpersoned, a prize-winning book of creative transcriptions of immigration interviews obtained by the Freedom of Information Act, even though it was published nearly two decades ago. His poetry has been overlooked for all previous generational anthologies and it is only thanks to the fine-tuned sensibilities of this book’s editor that has he finally become one of the chosen. You would expect him to be grateful.

> Okay…so I said above that there weren’t hard or fast judgements; maybe I should retract that slightly. The text definitely doesn’t feel like a cruel critique of poets generally (its comedy is too clever for that) but, yes, there are a fair few judgements from Adam creeping into those bios. I am so impressed with the way in which Dunthorne is able to expertly navigate Adam’s perspective through all these fragments to create this growing humour, as the character can’t help inserting his own opinions into other poets’ bios. Of course, we are also able to make our own judgements about Adam and his endearing naivety: shout out here to my fave character in the story, Joy Goold (‘exhilaratingly Scottish’) who has submitted the poem, Fake Lake, to the anthology. Hopefully if you’re Scottish, you can appreciate the comedy of this title. Adam Googles her and cannot find any trace of her, which feels perfect…almost too good to be true.

> Dunthorne plays with cliché overtly throughout the text. You could say all the poets in this story are exaggerated clichés but that certainly doesn’t make them boring: it just adds to the knowing intimacy that, yes, feels slightly gossipy (which I can’t help but enjoy). For example, there is the poet who has:

[…] won every major UK poetry prize and long ago dispensed with modesty […] Though he does not need the money he teaches on the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His latest collection is Internal Flight (Faber/FSG). He divides his time between London and New York because they are both lovely.

I am leaving out a fair bit of this bio because I don’t want to take away some of the joy of simply reading this text in its entirety but it is one of many tongue-in-cheek observations that feels very accurate and over-the-top at the same time (I feel like everyone in the poetry community knows this person). It is also even more knowing when you consider that Dunthorne actually has published a collection with Faber, O Positive (2019), a totally immersive read that also doesn’t shy away from poking fun at its speaker throughout. I always like seeing the ideas that repeatedly crop up in a writer’s work and explorations of calculation and cliché are at the forefront of this collection. I keep thinking of this line from the poem ‘Workshop Dream’:

We stepped onto the beach. The water

made the sound: cliché, cliché, cliché.

Interestingly, there is this hypnotising dream-like quality to O Positive - with shape shifting figures, balloonists, owls-in-law – in contrast to the hyper realism I experienced in the Rough Trade pamphlet. However, like All the Poems, in O Positive, we’re always one step inside the writing, one step outside, watching the poem/short story being written. It’s this continual sensation of being very close to failure and embarrassment/cringe. (I can also draw parallels here between Dunthorne’s exploration of this theme and the poet Colin Herd who speaks so brilliantly about the relation between poetry and embarrassment- see our SPAM interview.) Failure is just inevitable in this narrative set up. It makes the turning point of the narrative- when it arrives- all the funnier:

As Adam typed, he hummed the chorus to the Avril Lavigne song–why d’you have to go and make things so complicated?–and smiled to himself because he was keeping things simple. Avril Lavigne. Adam Lorral. Their names were a bit similar. He was looking for a sign and here one was.

> If it isn’t clear already, this is a story that I could continually quote from but to truly appreciate the work, you should read it in its beautiful slim pamphlet format created by Rough Trade Editions. For me, the presentation of this work is as important as the form: this story would have a different effect and tone if it was nestled inside a short story collection. I think a lot of the most exciting creative writing right now is being published by the innovative small indie presses springing up around the UK. Recently I listened to a great podcast by Influx Press, featuring the writer Isabel Waidner: they spoke about both the value of small presses taking risks with writers and the importance of recognising prose as an experimental field, rightly recognising that experimental work often seems to begin with, or be connected to, the poetry community. Waidner’s observation felt like something I had been waiting to hear…and a change that I had noticed in writing being published in the last few years in the UK. I could mention so many examples alongside the work of Rough Trade Books: Waidners’s We are Made of Diamond Stuff (2019), published by Manchester-based Dostoyevsky Wannabe, Eley William’s brilliant Attrib. and Other Stories (Influx Press, 2017), the many exciting hybrid works put out by Prototype Publishing, to name just a few. There is also a growing interest in multimedia work, for example Visual Editions, who publish texts designed to be read on your phone through their series Editions at Play (Joe Dunthorne did a brilliant digital-born collaborative text with Sam Riviere in 2016, The Truth About Cats & Dogs, I would highly recommend!). But this concept of combining the short story with a pamphlet format, created by Rough Trade Books as part of their Rough Trade Editions’ twelve pamphlet series, feels particularly exciting to me and is a reminder of why I love the expansive possibilities of shorter prose pieces. Through its physical format, we are reminded that this is a prose work you can read like a series of poems without losing the narrative tension that is so central to fiction. The expansiveness of the reading possibilities of Dunthorne’s short story also reminds me of Lydia Davis’s short-short stories. Here’s one I love taken from The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis (Penguin Books, 2009):

They take turns using a word they like

“It’s extraordinary,” says one woman.

“It is extraordinary,” says the other.

You could read this as a sound bite, an extract from an article, a writing exercise or a short story, the possibilities go on; there is a space created for the reader and consequently it encourages the unravelling of re-reading (which feels like a very poetic mode to me). Like Davis, Dunthorne’s work also highlights how seemingly simple language can be very powerful and take on many subtle faces and tones. I think short forms are so difficult to get right but when you encounter all the elements of language, tone, pacing, style, space, tension brought together effectively (or calculatingly as Dunthorne might say), it can create this immersive, highly intimate back-and-forth play with the reader.

> All The Poems Contained Within Will Mean Everything to Everyone. The title tells us there is a collection of poems here that are hidden: the central work has disappeared leaving behind the shadowy remains of the editor’s frustration and the marginalia of the bios. We feel the presence of the poems despite not actually reading them. The pamphlet’s blurb states that this: ‘is the story of the epiphanies that come with extreme tiredness; that maybe, just maybe the greatest poetry book of all is one that contains no poems.’ The narrative, as well as making fun of itself, also recognises that poetry exists beyond the containment of the poems themselves: it can be found in the readings, the performances, the politics, the drafts, the difficulties, the funding, the collaboration, the collectivity, the bios.

> A friend of mine recently asked me: Where are all the prose parties?…And what might a prose party look like? We were chatting about how a poetry party sounds much cooler (that’s maybe why there’s more of them). I think prose is often aligned with more conventional literary forms, maybe closed off in a way that poetry is seen to be able to liberate, but I think Dunthorne breaks down these preconceptions and binaries around form and modes of reading in All The Poems. I want to be at whatever prose party he’s throwing.

[1] University of Glasgow’s Creative Conversations, Sophie Collins interviewing Will Harris, Monday 4th May 2020 (via Zoom)

~

Text: Kirsty Dunlop

Published: 10/7/20

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

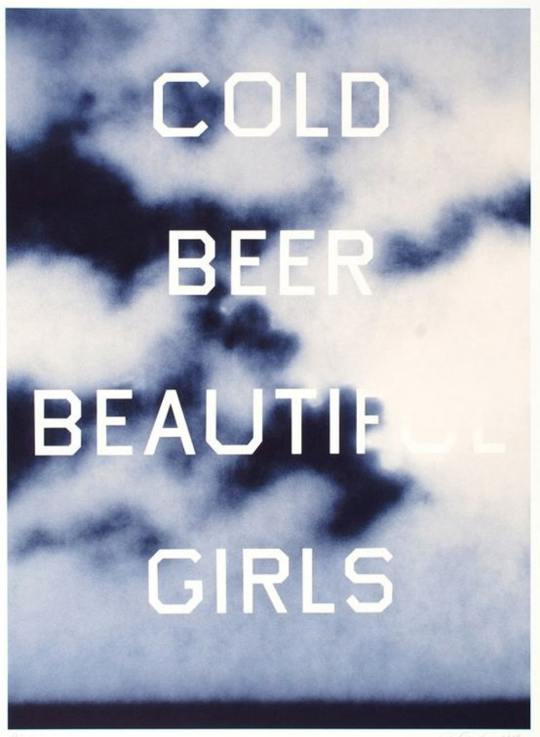

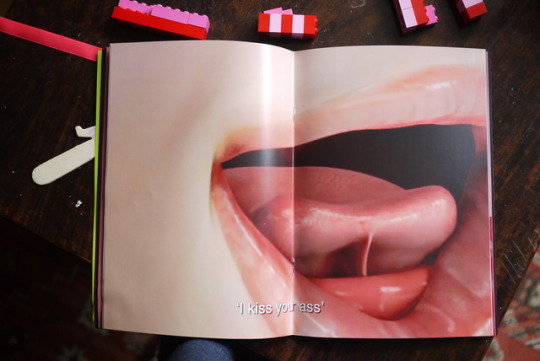

(REVIEW) Old Food, by Ed Atkins

Jon Petre takes a hearty bite out of Ed Atkins’ Old Food (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2019), musing on the transfiguration of consumption and disgust into a carnivalesque prose poetry of mastication, food prep and Dadaist stylistics.

> There’s nothing worse than food cooked badly, is there? On our street we used to have sleepovers at a friend’s house. His parents couldn’t cook for shit. To this day I recoil to think of breakfast at his, which was always lukewarm beans, underdone toast and grey sausages, their skins thick and resistant to slicing, the meat inside limpid and oozing water. You’re more likely to remember an awful meal, I think, than a decent or just an average one. You remember consumption when it’s disgusting.

> Bad food sticks in the memory as well as the throat. It takes you back: a glimpse of grey sausages and I’m a twelve-year-old snob again. The opening scene of Ed Atkins’ Old Food (2019) strikes a similar chord:

Spring finds medium son just on the

floor. Looks maybe six? evil, holds

the red plastic-handled table knife in

a small right fist, fishes a slice from

the open bag of bad read with a left.

> What follows is a slightly sickening description of buttering bread with ‘crumb-stuck margarine’, margarine on the foil lid, margarine glistening on the kid’s skin and an old sock where it’s smudged in the food-prep process. It’s such a specific, carefully observed scene, with all the detail of a memory. The speaker destabilises the workaday and familiar (buttering bread, being awake before your mum at the weekend) and makes it an uncanny, vaguely gross and alien process. And that’s just for starters: welcome to Old Food.

> Old Food began life in 2017 as an art installation at the Martin-Gropius Bau in Berlin. I didn’t see it. From what I gather from videos, images and reviews online, animation formed a central part of the exhibition. In Atkins’ films, hyper-realistic people gorged themselves on food, eating and dying in some nightmarish uncanny universe. Old Food became infamous for a CGI shit sandwich that was full of tiny babies. In one film, a creepy child jerkily crosses the room and plays the piano as a storm rages outside. This book, elegantly published by Fitzcarraldo Editions in their signature blue French-flapped style, distils that visual exhibition into a verbal form: a fatty lump of consumption and disgust rendered into prose poetry.

> The speaker, or speakers, takes us through a series of meals and mealtimes. I felt like I was reading someone’s hardscrabble childhood, picturing Lord of the Flies children foraging for herbs and thieving cast-offs in a violent dystopia. But it feels wrong to ascribe Old Food such a linear narrative. No, Old Food is a carnival. A parade of savage mealtimes, a festival of overindulgence and late-capitalist excess. It is a meditation on the strange ways that consumerism has chewed up our animal instincts of desire and consumption.

> Old Food is narrated in second-person, and I was transfixed by the ‘we’ of the speaker: ‘We used to cut most everything with fridge-cold clammy chicken’, ‘we’d cut parachute silk / with skate wings’, ‘We became happy brutes’. For whom are they speaking? Are they carnal and transgressive as a collective, or is the speaker hiding in a crowd from individual responsibility? Vaguely troubling, rarely elucidated.

> Like artistic composition, food prep is both destructive and creative – taking a dozen bitty parts from a dozen separately whole things and making a composite other whole-thing whose wholeness depends entirely on how well it’s made, how well done-it is, how refined your taste is. Like art, food sounds mad. In its twisty language and wordplay, Old Food resembles some of the best Surrealist poetry (I won’t name names, taste being subjective) as well as the Futurists’ Manifesto of Futurist Cuisine (1930). The Futurists fetishized elaborate eating rituals as a way to cement ideas of nationalism and the supremacy of masculine desire. (they tried to ban pasta because it’d stop Italians from being uber-mensch.) Old Food comes out closer to Dada – sure food can be art, but it’s still full of shit!

> Words are chopped up and blitzed into paste, disassembled and reconstituted to suit the speaker’s palate. Peanut butter on bread is measured in ‘knifefuls’, zucchini is ‘scabbed’ in Tempura, and the ‘hot long release’ of pissing in a field sounds like ‘the frying pan sizzle’. This is poetry for a nation in turmoil, where even the language around who we are a nation and what is normal has started to go off. Old Food brings us down to its level.

> A roasted goose has ‘opened [its] legs’ for cooking; filling the bird’s cavity with stuffing is to ‘engorge to torture’. Eating has forever been synonymous with sex, but Old Food doesn’t take any prisoners – cooking juices are like body fluids, feasting is fucking, and so on. Sex, violence and eating – are all the same desire, Atkins suggests, carnal impulses that poetry is always better for embracing.

> Yet there is a tinge of desolation to all this gluttony and lust, no matter how fun. Old Food’s epigraph is from Georges Bataille: being formless, we may as well imagine it as ‘something like a spider or spit’. There is no grand narrative behind eating three meals a day until you die. Imagine every meal you’ve ever eaten, the good and the bad, the Wotsits and the Wellingtons, the slurped oysters and the Daddies’ sauce and, no matter how delicious or well-prepared they were, it’d all be the same in a vast, Sisyphean heap. There’s horror between those buns.

> ‘What’s at stake with this sandwich?’ the speaker asks, and the answer is desire itself: which desires we’re willing to admit to, which inhibitions we’re willing to shed. Whether it’s food or sex, someone is trying to sell us a fantasy of consumption; to think of either as sacred is absurd, Atkins seems to say, and in Old Food we’re better off revelling in the shit than swallowing it.

There used to be justice rather than

I don’t know chocolate eggs. There

used to be rallying cries’d rather than

just a rich man suppressing belches at

you. There used to be an unopened box

and an open front door.

> By revelling in the shit, with its imagery of disgust and vocabulary of consumption, Old Food makes a stink about the sourness of our sex and food after late capitalism’s had its way with it. It’s credit to Atkin’s talent as an artist that he can move between visual art and prose poetry without seeming to lose his bite. If Old Food is like Surrealist poetry, then it is because you can enjoy the poetry as much for its puns as its absurdist critique of late capitalism. And for all the Bataille and nihilism, Old Food is a reminder that consumption is fun. Forget health cleanses and behaving yourself in public. What’s wrong with wanting crisp sandwiches and dirty sex?

~

Text: Jon Petre

Published: 7/7/20

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

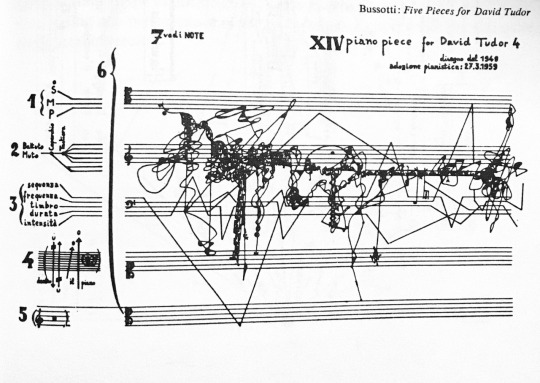

(SPAM Cuts) The Noughties, by Dom Hale

Attending to the poetics of lightspeed capital, everyday internet phenomenology and aesthetic refusal, Mau Baiocco explores Dom Hale’s ‘The Noughties’, a poem taken from Hale’s debut collection Scammer (forthcoming, the 87 Press).

> On February 1 a long poem, ‘The Noughties' drops into my inbox. 'I appear / to have failed to purge / my poem of evil' it reads roughly at the halfway point, '502 Bad Gateway / nginx / The literal just lost to me / Nostalgics / for toujours.' ‘The Noughties’ was first circulated as part of Dominic Hale's early 2020 edition of the file/pamphlet Scammer and at 44 pages takes up half of its contents. It is an experiment in serial and durational writing initially taking place between July 2018 and July 2019. Its form as well as composition are fragmentary, with short lines of unevenly indented text cascading down text boxes, an appearance that on the page bears a superficial resemblance to code, but when read aloud has all the jutting immediacy and scattered rhythms of something that cannot be compiled as a program or finished. And though I will attempt to trace questions around the relation between the internet, politics and poetics as they arise in ‘The Noughties’, a new and unprecedented arrival on something that might appear done to death (the ~internet~ poem), it should be noted from the outset that this poem is avowedly provisional, open to alteration and as much a mechanism of response to other poets and events as it is a finished work. Sitting down to appraise it, almost as a private inquiry, feels like refusing some of the poem's own motivations. If ‘The Noughties’ is about anything, it is about exchanges and modulations to be made outside the formal circuits of publishing, the commodity and ultimately capitalism. When read live—as I was lucky to witness twice in 2019—the poem is delivered at a rapid and at times overwhelming speed, straying far from considered intonation and 'poet's voice' but in an oppositional mode long explored by various poets such as Verity Spott, Tom Raworth or Peter Manson. Its text is a camaraderie, in all the inviting and indulging senses of the word.

> To admit the internet into history is to arrest the entirety of its internal logic, its drive towards immediacy and delivery of information on request—or even before we request or begin a search engine lookup, as algorithms quietly dispense tailored content, autoplays and preempt any personal vicissitudes we might have at a given moment. As being online ceases to be a specific activity and becomes the very basis of our lives (and dramatically more so following Covid-19), the internet takes on a phenomenology identical to encountering everyday life: the external world, its colours, the weather, a sentiment, an object. Our words for being online can paint an entire life-world as it is really being experienced. I couldn’t stand it, the internet was so annoying today. This transparency is only superficial: what appears to be truly memoryless, debugged and free of glitches is owed primarily to the quiet labour of developers, data centre workers and content moderators—industries rife with overwork, exploitation and even trauma at the exposure to daily streams of violence and hate. Behind every phenomenal seamlessness is a world of labour and agency that has been wrested away from the internet’s users and makers. This is far from the resource that would remake the public sphere, the heroic age of the developer-hacker-blogger-writer. At some point in our lifetime a transition occurred between accessing a resource and living through its infrastructure. Had it happened any more dramatically we would rightly call it a revolution on par with any other that came before it, with political and interpersonal consequences no less significant than those of any other revolution.

> The critical internet poem, the post-internet long poem, the always-online poem has to account for such a revolution: the gap from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0. It has to account for it as a real event where political and affective possibilities were seized by the powerful and online spaces sequestered and rerouted into sites of economic capture. Hale's 'sorry for cross-posting / stupidly nostalgic for the fucking noughties' is poised at the aftermath of this revolution, speaking back to the first decade of the 2000s through a relentless clash with the proper names for corporations and individuals (Bezos, Cuadrilla, G4S, Bill Gates, Northern Rock, etc) who have shaped the current world we inhabit. Arrayed against them is a belated deference to modes of grassroots management of online spaces (apologies for the cross-post), the ability to render these spaces malleable via creative interventions (forking), techno-utopian dreams that cross with play ('Snorlax used Snore! / Sustainable day') and the metabolic ease and abundance of 'We / eat as we go'. And yet, we are constantly reminded that to move from the past to the present means being carried by a 'katabatic wind'—a ceaseless descent that finds its origins at every point of the noughties and carries us on through to today. These winds, the matter of the skies as an invisible mover, figure prominently in ‘The Noughties’, and they are our guide through the fragmenting online landscapes of the decade since. When the winds reverse they end up 'hoovering / up the teleologies'; ecological catastrophes such as wildfires are seen congealing 'under the / pearling cumulus'. Like the financial flows and exchanges that pervade the poem, winds can go unnoticed until they collapse upon themselves or crash against lives that mean to resist them. These moments are revelatory of a whole structure at once: 'A sky’s a style' or 'A sky’s a clause', the grammar which shapes our political and expressive possibilities is loaded with toxic fumes, global and intimate as weather. It all lays open for contestation.

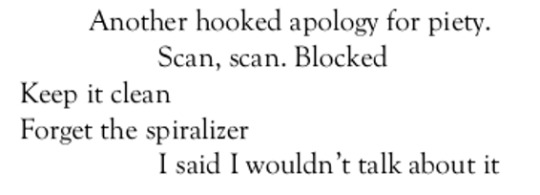

> In comparison to the fast-moving streams of text, riffs on information and broken data that surround it, a sort of speaking self appears in ‘The Noughties’. The ‘poet himself, as part of as part exposed nervous receptor, part digestor and regurgitator’ as Alex Grafen has written on Scammer’s companion pamphlet/pre-release Addons. It is often rueful, self-castigating and circuitously arrived at. It appears regularly in the guise of a comment or interjection. A distance from the surrounding text—set aside by line breaks and Hale’s deft play with sentential clauses—makes space for simultaneous ironic detachment and sincere observation. This wouldn't be unfamiliar to anyone who spends a lot of time on the internet; it is after all a very common affective position to speak from online. Other forms of internet speech feature in the poem too: textspeak, emoticons, emojis, etc, but my own response settles on moments where this voice appears, as if a remainder of pre-technological communicability:

> Perhaps what makes them stand out is that they are so often addressed and imperative. The imperative falls in line with a poetics of refusal figured in Anne Boyer's essay No, from which Hale draws the epigraph, 'Sometimes our refusal is in our staying put.' Perhaps the commitment to speaking and interjecting works out as a refusal to speechlessness. But this persistence paradoxically discloses very little: it would rather not talk, not participate, go back over itself. On the other hand it may coax a life out of life; its speech becomes more a sort of 'negative silence' which to Boyer is 'the negative’s underhanded form of singing', speaking while not speaking and asking when not asking. I think these gestures of refusal also gain a specific valence within a long durational work such as ‘The Noughties’. From the outset the poem aims to figure as a text of life, a response born from the everyday. This specifies the refusal as a sort of refusal to the everyday temporality out of which it arises, a refusal of the working day or even a refusal to work: 'I will never / be fulfilled by any kind of work.' This is seen more clearly still as the poem develops and the specificities of the decade—war alongside economic boom, proliferation of websites, technologies and interfaces to enact one's self-presentation to the world, to give voice to our newly minted online selves—begin to add up. The voice threatens to drop out entirely:

> In these lines poetry is pitted against the ability to survive the everyday economies of making ends meet. It signals a larger background of sustenance, a whole undisclosed sphere which undergirds the year-long writing of the poem yet cannot be easily verbalised. The gloss we can give to the gap between this sphere and ‘The Noughties’’s own enactment is a no, a refusal to make the link between the circuits words take on page and those of the background out of which they emerge. There is a doubleness to 'now, now', shading over to both 'no, no' but also that the poem must return to its present elaboration, the site of its self-recognition. Reading this gap as a refusal opens the possibility that the poem's own dynamics—the very rhythms it falls into, its very online texture—can militate against the extension of working life into non-working life. 'Hacking', so often the trite word for unauthorised access into systems and circuitry, springs to mind here, but in its older meaning. A sort of choppy relentlessness abounds in ‘The Noughties’, where two types of ‘work’—that of the poem and that of the post-internet working day—extend into one another, bristling at the seams and unveiling oppositions where we could have forgotten there were any.

> In Sleep-Worker's Inquiry, an anonymous text published on the communist journal Endnotes, a tech worker begins to dream in code, coming upon problems raised by their working life and solving them in their sleep. The worker asks if this is meaningfully different from their everyday waged work: 'When I find myself observing myself sleep-working, I observe myself acting in an alienated way, thinking in a manner that is foreign to me, working outside of the formal labour process through the mere spontaneous act of thought.' Self-estrangement has always been an aesthetic resource of the avant-garde, but its possibility always corresponded with the availability of leisure and other types of 'free' time. When our estranged selves are also signed up to the imperatives of production, what spaces are left for the creation of social alterities, dream worlds and landscapes where we do not come under those same imperatives? As technologies extend the working day by making us become forever available to our jobs, as the everyday labour of self-making on social media becomes collated and valorised as data which accrues its owners stock value to be exchanged on the market, distance from any economic activity becomes impossible. It becomes inchoate as the speaker’s voice in ‘The Noughties’, refusing as it proceeds.

> But I find that as I fixate on this voice of refusing, I almost forget that what makes ‘The Noughties’ so enticing to read and pick up is the heaving pile-up of dead data, outmoded imperatives and pithy renderings of cultural touchstones we would rather forget. 'What is this ‘dick chainy’ / and where can I get one?' To hold all these together, to attend to this conflagration of material is also to remember that, profoundly, the noughties were a fucking awful decade, with an enormous amount of political and cultural dead ends that the poem (happily) fails to enumerate. If the noughties represented the smirk of capital at history's end, ‘The Noughties’ enacts its degradation into our modes of present living. But we hold on to our imperatives, to care, to refuse and somehow make a world otherwise.

~

‘The Noughties’ is taken from Scammer, Dom Hale’s forthcoming collection from the 87 Press. You can watch Hale perform extracts at The Roebuck, London last year:

youtube

Text: Mau Baiocco

Published 3/7/20

0 notes

Text

(REVIEW) The Baudelaire Fractal, by Lisa Robertson

Gloria Dawson explores the refractive, highly seductive sensorium and aesthetic rapture of Lisa Robertson’s new novel, The Baudelaire Fractal (Coach House Books, 2020)

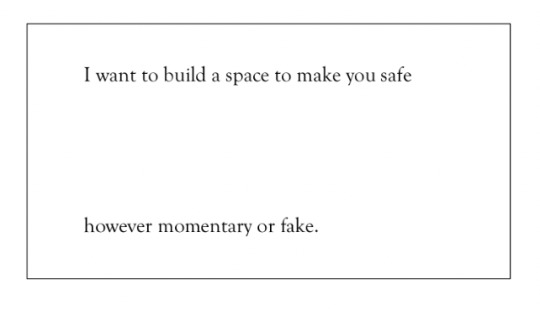

> I am deeply and highly seduced by this book, in which the narrator, Hazel Brown, a form of Lisa Robertson herself, recalls her becoming as a girl who wants to write, who does write, and along the way realises that it is true that she is the author of everything Baudelaire ever wrote. This is a strange conceit (to my mind also a very poetic jab at the whole conceit of a conceit) that provides a sort of architecture, but isn’t integral to the one-way direction of a plot. This conceit remains a conceit; a true one, but never, as in a conventional novel, a fact. The clue of this book is in the name; it’s fractal, there is no conclusion, the villain and hero is the girl, Hazel Brown, and her desires.

> My desire for perfumes is a curiosity which I have kept in check due partly to a sort of leftwing ascetism, and partly just lack of spare cash. But during the pandemic, two friends have sent me scents, and so it’s not surprising that one of the aspects of the book I experienced most strongly is the narrator’s relationship to perfume.

> Sillage is the degree to which a perfume’s scent lingers in the air when worn. It is a unit of time; like a radioactive particle’s potency, it decays by its own particular degrees. I see in Robertson a refraction of Baudelaire’s prose poem, ‘Invitation to A Voyage’, where a queasy luxury is subtly undermined by the impossible identification of persons and political regimes with that luxury: ‘Those treasures, that furniture, that luxury, that order, those perfumes, those miraculous flowers, they are yourself.’ In the chapter ‘Scent-Bottle', framed partly through a bottle of Estee Lauder’s ‘Youth-Dew’, a gift from her grandmother, the narrator recalls:

Always now the thought of the perfume in its cheap fluted glass

bottle with gold paper label brings me back to that shitty room, its

darkness, the blue typewriter on the folding table, the bad linoleum,

these traits a carapace camouflaging a small freedom that gently

expanded inside me like a subtle new organ, an actual muscular organ

born of my own desire for what I took to be an impossible and

necessary language. Its sillage was an architecture.

Unlike Baudelaire, Robertson’s parataxis is without luxury. Even the perfume, or at least its carapace, is cheap. The scent of the clauses following that list is typical of the way in which Robertson’s sentences breathe into a form that branches whilst still following its line into a direction of freedom (a small freedom, a freedom that is/like an organ, organ developing its matter), a direction of desire. And then in five words; a proposal and also a proposition. Follow me again into a conceit. The dissipation of scent as a unit of time, imprecise but unmistakable, turns up later in the descriptions of the avoidance or impossibility of both cleanliness and its aesthetic. If the poet stinks, Hazel Brown tells us (and she did), ‘the poem must stink’ too.

Even reading the diary now I seem to detect the long sillage of

acrid barks and herbs unctuously covered by vanilla, so that I am

unsure whether years ago some amber drops of the viscous liquid

actually penetrated the paper or whether my imagination produces this

perfume as an insistent and elaborately feminine base note of reading.

Nadar said of the young Baudelaire that he poured drops of musk oil

from a small glass vial onto his red carpets when he entertained his

friends in his baroque apartment at the Hotel Pimodan. I had entered

the musky sillage. The deepening life of reading was now the

transmission of an atmosphere, a physiology of pleasure and its

refusal or its augmentation by the several ghost-senses that moved

between the phrases of a text.

Here is a blossoming of that tight conceit — ‘Its sillage was an architecture’ — nestled and unravelling at a different point in time in the narrative; a long sillage indeed. I love Robertson’s unwavering mistrust of luxury and cleanliness, the authoritarian identification of cleanliness with moral purity which is more insistently satirized in Baudelaire. Yet despite his critique, Baudelaire, as Hazel Brown knows, was as weak to luxury as the next man or girl, and in reweaving a Baudelairean narrative, Hazel Brown as Baudelaire as Robertson can reveal her own desires and undoings. Returning to ‘The Scent Bottle’, the chapter ends in a luxurious apartment that Baudelaire may have coveted and wrought, in which the narrator is informally employed as a housemaid-childminder:

Those tight rooms first exposed me to the domesticity and decor of

wealth and the erasures and contradictions it masked. Everywhere there

was damage. In the rooms filled with rarity and the dullness of

familial hatred and jealousy, in the now-forgotten password spoken to

the armed soldiers at the school, in the prying glance of the

concierge, in the horrible statues of shoeshine boys, all of these

things functions of varying scales of imposed and policed positionings

of superiority, I thought I could intuit the whole sadistic spectrum

of the political world. It was heavy with grief. This sensation was

not aesthetical; it was the enforced affect of the sex of a political

economy, of masked histories of colonialism, of the ugliness of

wealth.

Before we can grasp the scent of these judgements (‘the whole sadistic spectrum of the political world... the enforced affect of the sex of a political economy’), the jagged line of Robertson’s fractal rhetoric is at work on another plane; the erotics at work in the work of following a realisation of an apprenticeship, a vocation for the matter of writing:

My dream of grace, the difficult ideal I struggled towards in sex

and in paintings, my unformed language for this feeling that was

trying so mawkishly to become a life, would have nothing to do with

what passed for luxury. But it couldn’t be anchored by sadness either.

I felt sure that beauty could only be slovenly and that love also

could only be a slut.

Re-recalling moving through Paris and its political economy, and following the line of her pen from the censuring of Baudelaire’s ‘anachronous embrace of the baroque’, Hazel Shade reaches yet another conclusion-opening.

There could be no aesthetics of ambivalence in Second Empire Paris;

capital’s tenure permitted sincerity only. The sincere subject was

governable. But beneath the city was another city, a place where

monstrosity could find its double.... this other city was even more

potently a linguistic city, a gestural city, a city released from

certain texts by their readers, as a sillage is the release of an

alternate time signature by the perfumed body. No perfume, no syntax,

no flower can be definitively policed.

Perfume can be liberation, an ‘alternate time signature’, a grace caught in fractal moments. It takes the courage of this book not to dissolve or just be mute in the apprehension of everything that you can touch and know that putting you together it undoes you. Towards the end of the book, the narrator, sometimes dis-guised as Lisa Robertson, re-reads a favourite essay, Emile Benveniste’s ‘The Notion of Rhythm in Its Linguistic Expression’. Robertson’s reflection upon what moves the writer is for me a close summary for the work of this book. It touches again on how clothes and styles, as well as perfume, can be a vital form of our thinking, being, becoming.

Form is a gestural passage that we can witness upon a garment in

movement, a face in living expression, or in the mobile marks of a

written character as it is traced by the pen. Rhythm, an expression of

form, is time, but it is time as the improvisation that moves each

limited body in play with a world. Not necessarily metrical or

regular, it’s the passing shapeliness that we inhabit. It both has a

history and is the history that our thinking has made.

I want to spend many hours tracing the rapture of this book, as well

as its seductions. Rapture; to be seized but also to be possessed by

joy; seduced: to be drawn aside but also led astray, wholly fractal,

line by line into the story’s willing and willed disintegration.

[With many thanks to Andy Spragg for the editorial comments, and to all the friends I talked about this book with! None of our work is ever done alone.]

The Baudelaire Fractal is now available to order via Coach House Books.

~

Text & Image: Gloria Dawson

Published: 30/6/20

0 notes

Text

(HOT TAKE) Notes on a Conditional Form by The 1975, part 2

In the second instalment of a two part HOT TAKE (read part one here) on The 1975′s latest LP, Notes on a Conditional Form (Dirty Hit, 2020), Scott Morrison ponders the tricksterish art of writing about music, before riffing on the history of the album as form, questions around genre, nostalgia and a sense of the contemporary, not to mention that saxophone solo and why Stravinsky would love this album.

Dear Maria,

> How pleasant it feels to begin a review with a note to a friend.

> Shoutout/cc:/@FrankO’Hara – I always liked his idea to write a poem like it’s addressed to just one other person. It strikes me as interesting to begin a piece of criticism in the same way. So, this is the mode I will try to inhabit throughout.

> As I read your words, and pondered, and learned, I was caught in the twin state of delighting each time you hit upon something already identified in my own thoughts – some of which I will expand upon here - and equally delighted every time you wrote something I could or would not. Such is the joy of conversation.

> I suppose in this preamble between speakers, which keeps up the pretence of our characters conversing - which will, inevitably, lapse as the form of this review gives way to a longer, more oneiristic, probably, onanistic, possibly, enquiry into the album (an act impossible in real conversation, by the way, imagine, imagine someone actually speaking for this long, how boring and alienating that would be, and yet that is usually what criticism is). Anyway, before all that, to help set the scene, I should mention a few ‘real world’ details. All of which happened either online, of course, or in isolation, because that, as you mention, is the real world now, during the violent interlude of Covid-19.

> I was delighted – that word again, repetitions and patterns begin anew already – to be asked to write this review. Firstly, because, like you say, I am a fan of The 1975. But also, because I am a writer and I am a musician and I am trying just now to forge a new mode of writing about music, one that can be both analytical (technically, socially, historically) and expressive (personally, lyrically, emotionally). And, most of all because I have always been, at best, suspicious, and, at worst, dismissive, of album reviews.

> I wrote, in our Messenger chat, ‘I usually find music reviews unhelpful’, which makes me sound like a bit of a dick, really. But what I meant is, what I meant is.

> There’s a saying I think about a lot, as the aforementioned writer and musician who writes about music: ‘writing about music is like dancing about architecture’ (Martin Mull, Frank Zappa, or Elvis Costello, or any of the other people that sharp quote is blurrily misattributed to.)

> Incidentally, I would love to see a dance about architecture. But sometimes I think the sentiment of the statement is true. Will writing about music always be missing the point? Will it, through words, ever really be able to get to the essentially wordless essence of music? But I am a writer. And I am a musician. And I like writing about music. (Incidentally, I like making music about writing less). Yet I do feel there is some truth to the saying, I guess. Twists and turns. Try again. Here is another way of saying what I am trying to say.

> Music reviews make me hate adjectives. And I love adjectives. But often commercial reviews – for dozens of reasons, many of them valid, most of them related to that capital prefix – become attempts to describe a sound, invariably an artist’s ‘new sound’, again related to that capital prefix. Often, the goal is to generate press, to entice people to listen – or not – and so feed the music industry and the market. And to describe these new sounds, adjectives are piled-up like car crashes. Trying to describe a sound at any great length is, I think, ultimately fated to fail. Adjectives, up to a point, can provide greater and ever-more strident clarity. But, after a certain point – that appears very quickly in most pop reviews - saturation point is reached, and the clarity disappears, and we are left very far away from the music we were originally trying to pile word upon word to reach. ‘Nothing Revealed / Everything Denied’, you might say, if you were into foreshadowing. Which I am (obviously).

> So, I suppose, to continue thinking out loud (in silence, at my keyboard) I am interested in writing around music. Not describing the sounds (‘Let sounds be themselves’, says John Cage, whispering in my memory’s ear), but I am interested in writing that can tease out some of the ideas in and around the music and extend them in new directions. That, I think, is a different and interesting kind of dance worth attempting.

> We understand a review, then, as this kind of dance: as a record of the reviewer’s experience of listening to a record, which will accept that it will largely take as its subject the listening, and not the record. Even better if it’s a dialogue between two. So, here’s what I think about the album.

*

> Ok, before I talk about the album, actually, I would like to talk about a book. I hope that’s alright. There is no objective correlation between the album and the book except the proximity in time in which I experienced them. Let’s get that out of the way at the very beginning. The book has nothing to do with the album. But it does have something to do with how I heard it.

> The book is called An Experiment with Time. I mentioned this to you once already over Zoom. It was written in 1927. My copy belonged to my grandfather, in fact, and his writing – and so his pen and then his hand and then his whole vanished being – appeared occasionally at marginal or pivotal points throughout the text. That was part of what I liked about it, I guess.

> The book – which I allowed Wikipedia to tell me only after I had pushed my way through it – is regarded as an imaginative curiosity, but one which science has never taken seriously. That’s fine for me, because I am far more familiar, fluid and fluent in the language and implications of the imagination that I am of science.

> The book, broadly in two halves, sets out in its first strange span experiences of premonitions in dreams. That will give you the idea of the kind of science book it is. The second half is an attempt at a logical, philosophical, and occasionally mathematical explanation of Time that can account for these premonitory fissures.

> It posits that, in addition to the three dimensions of space (height, breadth and depth, I suppose), that time is a fourth dimension in our universe. I’ve heard that said, but I never really got it before. I do now, and it is very beautiful, because it begins to make me imagine, how, like a sculptor, I can ply, fold and shape with this new dimension. You can imagine how this might be useful to a musician, music being an art that can only exist through time.

> Anyway, the book then goes on to posit that a fourth dimension in which something can be observed to travel (our consciousness), must necessarily imply an observer in a fifth dimension to observe that travel, and then one in a sixth dimension, and so on, ad inifitum, infinite regress, serial time.

> I confess this somewhat surpassed the boundaries of my metaphysics (and/or silently slipped over my head), but the image of the infinite regress has stayed with me, the clickanddrag of old Windows windows ossified and pulled to leave twisting, spiralling trails; the gold-tipped rhythm of tenement window embrasures, repeating, far off, clickanddragged up a hill (hints and twists of Escher), on my daily walks.

> Wikipedia later told me that an infinite regress is a shaky ground on which to base a philosophical proof. Again, this is fine for me: I am a bad philosopher, because I am not competitive, and so this does not bother me very much.

> The infinite regress is a beautiful image, with lots of possibility in it for further imaginings, and it entrances me. So, keep this idea of serial observers and the limitless extension it implies close, please (foreshadowing again, you’re welcome).

*

> I will switch now, briefly, too briefly, from critic to fanboy (I contain multitudes, etc.).

> Notes on a Conditional Form as an album title made me smile a smile that was very close to a wince or wink. Classic Matty, was probably the thought that came next. You have already summarised dastardly, dear, endearing, calamitous Matty, so I will move on assuming that, Matty Healy, yeah, I know.

> Back to the critic. The conditional form, in this review has already been (drumroll, eyeroll) music reviews themselves. See part one.

> Now I would like to take the album as the form in question – not this album, but albums generally, as this album is an exploration of the album form. The Album, capitalised.

> Albums have become normalised. But let’s play dumb for a moment – one of the cleverest things we can do - and we’ll see that albums are anything but inevitable, especially in the boundless age of streaming.

> Before this, albums used to be defined as collections with physical bounds. The capacity of a CD; before that, a length of magnetic tape; before that, the edge of a vinyl, a shellac, a wax cylinder. That about takes us back to the start of recorded audio media, I think.

> After Edison’s initial, waxy curiosities, albums began - like most things we love and hate - as a product. The form of the album was a circle. The music was a line. The edge of the line was the end of time. Marcel Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs, as a fun aside. And, as another, did you know that there’s a funny B-plot in all of this to do with Beethoven. (It’s always to do with fucking Beethoven.) Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony became the arbitrary marker for the desired length of the CD. It had never before been possible to fit the symphony onto a single, uninterrupted piece of media. And so, the B-plot goes, this is why the standard CD holds the amount of time that it does.

> Anyway, regardless of who shaped them, physical recorded media have, since their staggered births, profoundly shaped culture. Pop songs, especially singles, are still 3 and a half minutes long because that was the maximum amount of time that could be squeezed onto a 78, in the shellac days. Time was short and simple then, seemingly.

> Notes on a Conditional Form is 81 minutes long. It had 8 singles leading up to it, released over a span of ten months. Clearly, physical boundaries and marketing timelines, are not being treated in the usual way. You could just release singles forever now. But the fact this ended up as an album shows some belief in the concept beyond the physical and, yes, the commercial. Let’s press on, look elsewhere.

> Since we’ve started talking about classical music – ok, since I started talking about classical music – I’d like to dwell there for a moment, because there are foreshadows of The Album, conceptually speaking (and this album specifically) several layers up, several parenthesis ago, criticism as serial digression, in classical music.

> Collecting songs as albums was a favourite pastime of the Romantics, early emos. @FranzSchubert, @ClaraSchumann, @JohannesBrahms – there’s another B-plot in that trio if you want to look it up, by the way. Also, Clara Schumann is overlooked, like all female composers, because the classical music world is deeply patriarchal. It’s important to say that whenever we can.

> Anyway, the Romantics did not develop the album as a physical form – the only available recording medium at that time was sheet music, which they did sell in a big way, actually. But really, they helped develop the album as a conceptual form. They collected a group of shorter songs to make a larger statement – Schubert especially. In the 19th century, this was known as a song cycle, a lovely phrase, that makes me think of cycling through meadows, which I have done more than usual recently, as part of my state-sanctioned exercises, though the meadow was in fact an overgrown golf course, and no less lovely for it.

> Schubert’s Die Winterreise is a classic example of the song cycle – and another example of the emo-Romantic - a cycle of poems set to music that take the listener on a journey over time. Sound familiar? Albums. Song cycles. Song spokes. Meadows. Grasses and wildflowers. Meandering journeys.

> Anyway, here we finally return to Notes on a Conditional Form. Collecting songs together allows for an exploration of ideas that can evolve or expand over time – a Brief Inquiry, you might say. Art as a tool of investigation. Process. And this album certainly does that. You already touched on some of the ideas in the album: the climate crisis, the Anthropocene, digital communication, social unrest, calls to action, my favourite lyric on that theme, while we’re here:

Wake up, wake up, wake up, we are appalling

And we need to stop just watching shit in bed

And I know it sounds boring and we like things that are funny

But we need to get this in our fucking heads-

> You explore these ideas well so I will not pursue them more for now. Thank you!

> The other effect of collecting songs – or anything together – is that it gives birth to form. (Gasp, he said the title of the movie!)

> Yes, collecting things together as an album is what creates the form in all senses of the word – physical, commercial, conceptual. Form, pure form, is not the things, or the arrangement of the things, but the relationship between the arranged things. Glimpsing this is like getting a delicious glimpse of time as a fourth dimension. As I may have already let slip, I am very interested in time. And so, I am naturally interested in musical forms, which can only be apprehended through time, with time, thanks to time – thank you, time. We don’t often say that.

*

> This is where I will, at last - god, imagine I had been speaking at you this whole time - this is where I will at last get into the main topic of this review. The remarkable form of this album.

> Wait, sorry, one more thing before I do. A really quick one. As well as time, musical form also needs contrast. For sections to appear as distinct, and thus for us to clearly apprehend the difference between them, and thus get a glimpse of Form, they must contrast with one another, for how else would we apprehend change, notice borders, know we are somewhere else. (An interesting digression here is process music, which I love dearly, and which has an entirely different relationship with form. Look it up, if you like.)

> Anyway, for our purposes now, musical form requires contrast. This could be achieved in many ways: traditionally, it was done with different melodies or harmonies; but it could be done with volume, instrumentation, tempo, texture etc. etc.

> The main way that this album delineates its striking – and, to my mind, for what it’s worth, unique and new – form, how it creates its contrast, is using all of the above tricks, but, even more so, by contrasting styles/genres. This was immediately what struck me and thrilled me about this album, and it’s kind of funny – for me as the annoying writer, perhaps less so for you, the reader, I mean listener – that it’s taken me 2,534 words to mention it. This I think is the brilliance of this record. This is why we can call it not just contemporary, but new.

> The 1975 have always been shifting, but never like this. This album contains, sometimes literally right next to each other: punk, orchestral music, UK garage, Americana, shoegaze, folk, dancehall, 80s power ballads – and, of course, pop, whatever that means. Stravinsky became famous for sharp juxtapositions of distinct musical blocks. He would fucking love this.

> I messaged you, after my first listen, to say that the album reminded me of one of Sophia Coppola’s soundtracks. That was an instinctive, emotional response, but, having thought about it, I can now demonstrate the reason for the similarity. The stylistically varied end products are similar to one another because the methodology is similar: soundtracks select music practically to achieve emotional affects. Soundtrack albums use music as a tool to heighten ideas that lie elsewhere, in their case, in the filmed scenes they accompany. If you believe Matty Healy, this is also what The 1975 do. They use beauty, in whatever style or genre they find it:

‘Beauty is the sharpest tool that we have - if you want someone to pay attention, make it beautiful’.

> What do you make of that, @Keats? No, really, I would love to know.

> I think this is a remarkable musical strategy, that requires flexibility, knowledge and skill. That there is such a high level of all these things in the band is what allows it the strategy to be successful.

> I would like to pause here and consider the implications of this strategy on a personal, social and cultural level.

*

> Musical genre and personal identity have been as fused for as long as pop music has existed. This could be a trick of the market, or it could be a need of the individual psyche, or both. I think there is some truth in theory that in the increasingly widespread absence of God – by which I mean organised religion – people need to find both a guide for their metaphysics and morals, and a structure for their community, as these are some of the most effective tools we have discovered for constructing our Selves, making sense of our lives and the world. Art can provide the guide for many people. It also provides community. These communities, collections – albums? - of political, moral and aesthetic views, then become subcultures.

> Until very recently, subcultures were fixed. ‘Hardcore till I die’, ageing ravers, old punks. Interestingly one never really sees ageing emos. But that’s a subject for another essay.

> This, I think, is perhaps what is so striking here: musical genres are normally culminations (or roots, depending on how you look at it) of lived sub or counter cultures. These usually result from a fixed viewpoint about life and society, shared by the individuals that comprise them. The individuals identify with what the music says, how it is presented and how it looks as much – or perhaps even more - than how it sounds.

> Before now, it would have been shocking to imagine a band switching effortlessly from one style to another – this occasionally happens over the course of a career, between albums, but almost never in the same album itself - because it would feel like a betrayal, if we accept that bands and styles represent fixed ways of life and viewpoints and that neither lives nor viewpoints can change. Which, obviously they can. And which, obviously, they do, nowadays, with increasing speed, @Coronavirus.

> Matty’s appearance is a perfect demonstration of this. Minging Matty, Hearthrob Matty, Matty in vintage jeans, in a skirt, in a pinstripe suit. If we accept the old association of musical style/subculture and the clothing/uniform each produces, what would the ideal garb of a The 1975 listener be? A screen. A real, working search engine, fused with their body.

> Previously, the model was that bands had ‘influences’ which they ‘blended’ to create a ‘new’ sound. Here, The 1975 don’t really focus on blending sounds at the level of individual songs: the blend, boldly, happens at the level of the album. If the album is like a soundtrack, it is the soundtrack to the algorithmic age of effortless consumption of media.

> And I would like an examination of that idea to be the final track on this album. I mean, review. I mean conversation.

*

> The 1975 are inseparable from recorded media. Not just their own, but recorded media from the past. They are not able to invoke and inhabit this startling panoply of styles, to my knowledge, because they have studied in individual places or with masters of each craft or tradition – they are able to do it because they, like us, are able to consume recordings of these styles, and they, like us, have done so all their lives.

> When The 1975 invoke these styles, they are not evoking a tradition, or a way of doing things, or even seeing things. They are invoking personal memories of experiencing recordings, encountering media. We can take a look at a few examples of this.

> Let’s start with the classical stuff. The orchestral interludes do not sound like they are written by classical composers, or even composers of film soundtracks - the use of orchestration is different. It sounds, to my ear, like acoustic instruments playing what were originally MIDI parts. Which, I imagine, is what happened. That would usually be called bad orchestration. I am not interested in saying that. I am slightly interested in the effect of getting classical musicians, with their classical training, to play music written by people without classical training on a computer. What are the implications of writing for the flute as a soundfont, rather than a person, instrument or tradition?

> And what is the significance of placing an orchestra, playing instrumental compositions, on a pop record. These are not backing arrangements in an existing pop song, as we commonly encounter; nor are they classical arrangements of a pop song (see Hacienda Classical et al).

> These are standalone orchestral compositions on a record that also includes shoegaze, UK garage, two-step, Americana, punk. What, then, is the significance of this? The instruments, I believe, are being chosen less for their own sonic timbres, and more for their social or cultural timbres. I will try to explain this thought.

> Matty has often spoken about ‘Disneyfication’; he said he wanted ‘The Man Who Married a Robot / Love Theme’ on A Brief Inquiry into Online Relationships to sound like a Disney movie. What does that mean? It means, I think, he wants it to sound like old movies, childhood, nostalgia. The orchestra is a sinecure for the ‘symphonic’, the cinematic, the dramatic; the orchestra is used like a banjo, which is, elsewhere on the album, used to conjure the exoticism of Americana as heard by someone listening to it in the UK, to paraphrase Matty’s words.

> The stylistic references in the album are as much references to media as much as they are to music. Disney: orchestral sounds, likely filtered and wobbled through VHS cassettes. The orchestra, already made symbolic by its association with movies, made a double symbol, a reflection of a shadow, being invoked through the original sound not really for this sound but for our associations with it. The banjo invoked as both an instrument of yesteryear and over there. The music constructs frames of otherness to facilitate wistfulness, longing, memory.

> The chart success of ‘If You’re Too Shy (Let Me Know)’ is that it’s a modern bop that sounds like 80s bangers. Its artistic success is that it contrasts the feeling of halcyon safety created by its imitation of 80s bangers (experienced for millennials usually as triumphant climaxes in movies, jubilant moments on oldies stations), and rubs this up against some of the disturbing parts of the present: the angst of online relationships, nudity with people you don’t know and have not and may never meet. This is a simple but highly effective juxtaposition.

> ‘Bagsy Not In Net’ does this too: a quotidian, painful experience of childhood (not wanting to play in goal in a football game), expressed as a yearning and grand orchestral statement. This is true, too, of ‘Streaming’. This is pop music Pop Art: the contemporary quotidian expressed in the language of an old tradition and invested with the significance of an Art it simultaneously questions the power and validity of.

> And, to linger on ‘If You’re Too Shy’ for just a little longer, what is the meaning of a saxophone solo in pop music in 2020? It is symbolic: a shortcut, practically a meme. Saxophone solos exist in a present in contemporary jazz - they are a living history making new futures. But saxophone solos almost always only exist in pop music as ghosts (careless whispers) of the past. This particular sax solo is so euphoric to us less because of its musical content and more because of the emotions we have learned to associate with sax solos through other media.

> The final, most perfect example of this, of everything I have been getting at, really, is the UK garage references. These are themselves references to artists like The Streets, and Burial, who, themselves, were referencing the primary records of UK garage which they (The Streets and Burial) never experienced in clubs, but as recordings. And The 1975 experienced these recordings of recordings. Layers and layers of reference. And here, abruptly, we find ourselves back at the opening image of the infinite regress.

> At times, this album wants to express the present moment back at itself, and so prompt reflection and action. The fright of the zeitgeist. In this we can include Greta Thunberg, ‘People’, and the overtly socio-political statements on the album. I hope these tracks will be successful. In the future, they will take on the significance of historic artefacts: preserved truths from a vanished time, fixed and rich, like amber.

> But there are long swathes of the album, that do not have this intent, and which will, I believe, have a different longevity. These are the (often wordless) lyrical sections: the abstract, the vague, the instrumental sections – in all senses of the word. Records of the individual imagination listening to another individual imagination listening to another individual imagination. What will these tracks become in time, in Time?

> There is something ethereally delicious about the thought of people in the future coming across people in the past’s nostalgia of another past, now three links distant to their present, compoundly insubstantial, glittering, compelling. Fifth, sixth, seventh dimensions - serial nostalgias.

Notes on a Conditional Form is out now and available to order.

~

Text: Scott Morrison

Published: 26/6/20

#review#reviews#album review#music criticism#music review#Scott Morrison#The 1975#Maria Sledmere#Matty Healy

0 notes

Text

(HOT TAKE) Notes on a Conditional Form by The 1975, part 1

In the first instalment of a two part dialogic HOT TAKE of The 1975′s latest album, Notes on a Conditional Form (Dirty Hit, 2020), Maria Sledmere writes to musician and critic Scott Morrison with meditations on the controversial motormouth and prince of sincerity that is Matty Healy, the poetics of wrongness, millennial digression and what it means to play and compose from the middle.

Dear Scott,

> So we have agreed to write something on The 1975’s fourth studio album, Notes on a Conditional Form (Dirty Hit/Polydor). I have been traipsing around the various necropoli of Glasgow on my state-sanctioned walks this week, listening to the long meandering 80-minute world of it, disentangling my headphones from the overgrown ferns, caught between the living and dead. Can you have a long world, a sprawling fantasia, when ‘the world’ feels increasingly shortened, small, boiled down to its ‘essentials’? Let’s go around the world in 80 minutes, the band seem to say, take this short-circuit to the infinite with me. I like that; I don’t even need a boat, just a half-arsed WiFi connection and a will to download. I’m really excited to be talking with you, writing you both about this; it’s an honour to connect our thoughts. I want writing right now to feel a bit like listening, so I write this listening. When my friend Katy slid into my DMs on a Monday morning with ‘omg the 1975 album starts with greta?????????’ and then ‘what on earth is the genre of this album ?!’ I just knew it had to happen, this writing-listening, because I was equally alarmed and charmed by the cognitive dissonance of that fall from Greta’s soft, yet urgent call to rebel (‘The 1975’), into ‘People’ with its parodic refrain of post-punk hedonism that would eat Fat White Family on a Dadaesque meal-deal platter ‘WELL, GIRLS, FOOD, GEAR [...] Yeah, woo, yeah, that’s right’. Scott, you and I went to see The 1975 play at the Hydro on the 1st of March, my last gig before lockdown. I’d been up all night drinking straight gin and doing cartwheels and crying on my friend’s carpet, and the sleeplessness made everything all the more lush and intense. Those slogans, the theatrical backdrops, the dancers, the lights, the travellator! Everything so EXTRA, what a JOURNEY. And well, it would be rude of me not to invite you to contribute to this conversation, as a thank you for the ticket but also because of your fortunate (and probably unusual) positioning as both a classically trained musician (with a fine-tuned listening ear) and fervent fan of the band (readers, Scott messaged me with pictures of pre-ordered vinyl to prove it).

> It seems impossible to begin this dialogue without first addressing the FRAUGHT and oft~problematic question of Matty Healy, the band’s frontman, variously described as ‘the enfant terrible of pop-rock’ and ‘outspoken avatar’ (Sam Sodomsky, Pitchfork), ‘enigmatic deity’ (Douglas Greenwood for i-D), ‘a charismatic thirty-one-year-old’ and ‘scrawny’, rock star ‘archetype’, not to mention ‘avatar of modern authenticity, wit, and flamboyance’ (Carrie Battan, The New Yorker). ‘Divisive motormouth or voice of a generation?’ asks Dorian Lynskey with (fair enough) somewhat tired provocation in The Guardian, as if you could have one without the other, these days. ‘There are’, writes Dan Stubbs for The NME, ‘as many Matty Healys here as there are musical styles’. So far, so postmodern, so elliptical, so everything/yeah/woo/whatever/that’s right. Come to think of it, it makes sense for The 1975 to draft in Greta Thunberg to read her climate speech over the opening eponymous track. Both Matty and Greta, for divergent yet somehow intersecting reasons, suffer the troublesome, universalising label of voice of a generation. Why not join forces to exploit this label, to put out a message? I’ve always thought of pop music as a kind of potential broadcast, a hypnotic, smooth space for desire’s traversal and recalibration. More on that later, maybe. What do you think?

youtube

> You can imagine Matty leaping out of a cryptic, post-internet Cocteau novelette (if not then straight onto James Cordon’s studio desk), emoji streaming from his fingertips like the lightning that Justine wields in Lars von Trier’s film Melancholia (2011); but the terrifying candour of the enfant terrible is also his propensity to wax lyrical on another (bear with my clickhole) YouTube interview about his thoughts on Situationism and the Snapchat generation. It feels relevant to mention cinema right now, if only in passing, because this album is full of cinematic moments: strings and swells worthy of Weyes Blood’s latest paean to the movies, but also a Disneyfication of sentiment clotted and packed between house tracks, ballads and rarefied indie hits. Nobody does the interlude quite like The 1975. Maybe more on that later, also.

> Where do I start though, how to really write about this, how to attain something like necessary distance in the space of a writing-listening? Matty Healy, I suppose, like SPAM’s celebrated authorial mascot, Tom McCarthy, poses the same problem of response: how to write about an artist whose own critical commentary is like an eloquent, overzealous and self-devouring, carnivorous vine of opinion?

> Now, let’s not turn this into a discussion about who wears pinstripes better (we can leave that to readers - these are total Notes from the Watercooler levels of quiche). There seems to be this obsession with pinning (excuse the pun) Matty down to a flat surface of multiples: a moodboard, avatar, placeholder for automatic cancellation. He’s the soft cork you wanna prod your anxieties through and call it identity, you wanna provoke into saying something bizarrely, painfully true about life ‘as it is now’. Healy himself quips self-referentially, ‘a millennial that babyboomers like’. I don’t really know where to start really, not even on Matty; my brain is all over the place and I can’t find a critical place to settle. I’m lost in the fog and the stripes, some stars also; I haven’t even washed my hair for a week. Funnily enough, in 2018 for SPAM’s #7 Prom Date issue I wrote a poem called ‘Just Messing Around’ where the speaker mentions ‘pinning my eye to the right side / of matt healy’s hair all shaved / & serene’ and you don’t really know if it’s the eye that’s shaved or the hair, but both I guess offer different kinds of vision. Every time I google the man, IRL Matty I mean, I am offered a candied proliferation of alluring headlines: ‘The 1975’s Matty Healy opens up on his beef with Imagine Dragons’, ‘The 1975’s Matty Healy savagely destroys Maroon 5 over plagiarism claims’. Perhaps the whole point is to define (or slay?) by negation. Hey, I’ll write another poem. The opening sentence comes from Matty’s recent Guardian interview.

Superstar

I’m not an avocado, not everyone thinks

I’m amazing. That’s why they call me

the avocado, baby was a song released

by Los Campesinos! in 2013, same year

as the 1975’s debut. In the am

I have been wanting to listen

and Andy puts up a meme like

‘The 1975 names their albums stuff like

“A Treatise on Epistemological Suffering”

and then spends 2 hours singing about

how hard it is to be 26’ and I reply

being 26 IS epistemological suffering

(isn’t that the affirmative dismissal

contained in the title, ‘Yeah I Know’)

I mean only yesterday I had to ask

myself if it’s true you can wish on 11:11

or take zinc to improve your immune system

or use an expired provisional license

to buy alcohol

like why are they even still asking

I thought indie had died

after that excruciating Hadouken! song called ‘Superstar’

which was all like You don’t

like my scene / You don’t

like my song / Well, if you

Somewhere I’ve done something wrong

it seems a delirious, 3-minute scold

of the retro infinitude

of scarf-wearing cunts with haircuts, and yeah

sure kids dressed as emos

rapping to rave

is not the end of the world, per se, similarly

I had to ask myself is there a life in academia

is there a wage here

or there, like the Talking Heads song

And you may ask yourself, well

How did I get here?

Good thing I turn 27 next month

Timothy Morton often uses the refrain,

this is not my beautiful house

this is not my beautiful wife

to refer to those moments

you find yourself caught in the irony loop

and that’s dark ecology

the closer you are

the stranger it feels like

slice me in half I’ll fall out

with more questions

you can plant in the soil

like a stone or stoner,

just one more drag of

does it offend you, yeah?

will I live and die

in a band Matty sings

the sweet green

meat of my much-too-old

-and-such-youthful experience

of adding healthy fat

to conference dialogue, like

‘Avocado, Baby’ was released

on a record called No Blues

I believe a large automobile is hurtling

towards me now

in negative space

and the driver is crooning Elvis

and reciting my funding conditions

and everything feels like

there aren’t not still people

who believe the new culture

of content is a space ‘over there’