Photo

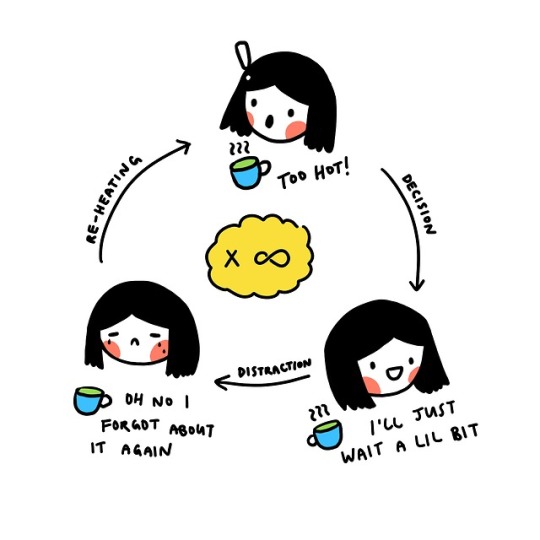

Haven’t posted here in ages. Here is gif I made for Monday mornings!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the Light We Cannot See: Thoughts

All the Light We Cannot See (Anthony Doerr)

To be honest, I wasn’t enthralled by this book—I didn’t connect deeply with any of the characters, and the descriptions (while sometimes charming or even captivating) were a bit overwrought and distracted from the characters’ emotions. That said, the multiple plot strands did flow together well, and the ending was bittersweet and reflective. I really, really wish that I felt a deeper attachment to the characters. I don’t know what it was—their situations were realistically grave, and their backgrounds sufficiently illustrated. But I just didn’t feel the pull.

Here are a few passages and descriptions that I enjoyed:

“Silence is the fruit of the occupation; it hangs in branches, seeps from gutters. Madam Guiboux, mother of the shoemaker, has left town. As has old Madam Blanchard. So many windows are dark. It’s as if the city has become a library of books in an unknown language, the houses great shelves of illegible volumes, the lamps all extinguished.”

“At midmorning Volkheimer orders them to park in the Augarten. The sun burns away the fog and reveals the first blooms on the trees. Werner can feel the fever flickering inside him, a stove with its door latched. Neumann One, who, if he were not scheduled to die ten weeks from now in the Allied invasion of Normandy, might have become a barber later in life, who would have smelled of talc and whiskey and put his index finger into men’s ears to position their heads, whose pants and shirts always would have been covered with clipped hairs, who, in his shop, would have taped postcards of the Alps around the circumference of a big cheap wavery mirror, who would have been faithful to his stout wife for the rest of his life—Neumann One says, ‘Time for haircuts.’”

“To shut your eyes is to guess nothing of blindness. Beneath your world of skies and faces and buildings exists a rawer and older world, a place where surface planes disintegrate and sounds ribbon in shoals through the air. Marie-Laure can sit in an attic high above the street and hear lilies rustling in marshes two miles away. She hears Americans scurry across farm fields, directing their huge cannons at the smoke of Saint-Malo; she hears families sniffling around hurricane lamps in cellars, crows hopping from pile to pile, flies landing on corpses in ditches; she hears the tamarinds shiver and the jays shriek and the dune grass burn; she feels the great granite fist, sunk deep into the earth’s crust, on which Saint-Malo sits, and the ocean teething at it from all four sides, and the outer islands holding steady against the swirling tides; she hears cows drink from stone troughs and dolphins rise through the green water of the Channel; she hears the bones of dead whales stir five leagues below, their marrow offering a century of food for cities of creatures who will live their whole lives and never once see a photon sent from the sun. She hears her snails in the grotto drag their bodies over the rocks.”

“What mazes there are in this world. The branches of trees, the filigree of roots, the matrix of crystals, the streets her father re-created in his models. Mazes in the nodules on murex shells and in the textures of sycamore bark and inside the hollow bones of eagles. None more complicated than the human brain, Etienne would say, what may be the most complex object in existence; one wet kilogram within which spin universes.”

“He thinks of the old broken miners he’d see in the Zollverein, sitting in chairs or on crates, not moving for hours, waiting to die. To men like that, time was a surfeit, a barrel they watched slowly drain. When really, he thinks, it’s a glowing puddle you carry in your hands; you should spend all your energy protecting it. Fighting for it. Working so hard not to spill one single drop.”

“People walk the paths of the gardens below, and the wind sings anthems in the hedges, and the big old cedars at the entrance to the maze creak. Marie-Laure imagines the electromagnetic waves traveling into and out of Michel’s machine, bending around them, just as Etienne used to describe, except now a thousand times more crisscross the air than when he lived—maybe a million times more. Torrents of text conversations, tides of cell conversations, of television programs, of e-mail, vast networks of fiber and wire interlaced above and beneath the city, passing through buildings, arcing between transmitters in Metro tunnels, between antennas atop buildings, from lampposts with cellular transmitters in them, commercials for Carrefour and Evian and prebaked toaster pastries flashing into space and back to earth again, I’m going to be late and Maybe we should get reservations? and Pick up avocados and What did he say? and ten thousand I miss yous, fifty thousand I love yous, hate mail and appointment reminders and market updates, jewelry ads, coffee ads, furniture ads flying invisibly over the warrens of Paris, over the battlefields and tombs, over the Ardennes, over the Rhine, over Belgium and Denmark, over the scarred and ever-shifting landscapes we call nations. And is it so hard to believe that souls might also travel those paths? That her father and Etienne and Madam Manec and the German boy named Werner Pfennig might harry the sky in flocks, like egrets, like terns, like starlings? That great shuttles of souls might fly about, faded but audible if you listen closely enough? They flow above the chimneys, ride the sidewalks, slip through your jacket and shirt and breastbone and lungs, and pass out through the other side, the air a library and the record of every life lived, every sentence spoken, every word transmitted sill reverberating within it.”

0 notes

Text

Sunday Sketching: Thoughts

Sunday Sketching (Christoph Niemann)

This was a fun, quick read—I am continually amazed by Niemann’s creativity and impeccable ability to draw connections between seemingly unrelated concepts. I’m inspired by his habit of bringing art and the “real world” together, from sketching the New York marathon (while running) to turning everyday objects into witty pieces of art.

It’s a very visual book, with Niemann’s artwork supporting almost every page, so these quotes are only half of what is there:

“Being busy is a great excuse for not asking yourself where you are going.”

“I had been happy with every aspect of my career, but you always have to change direction while things are good.”

“Enjoyment is not part of the job description, and any artist worth his salt loves to complain about the difficulty of the creative process—which begs the question: If it’s so terribly agonizing...

... why become an artist in the first place?

The gateway drug is not creating art, but experiencing art: seeing a painting, reading a book, or listening to music that expresses something that you always knew, but were never aware of. Having the whole world explained (or even better, turned upside down) just by looking at a few works on a piece of paper is the greatest thrill I know.

If experiencing art is so amazing, how great must it be to actually MAKE this stuff?

And that’s how they lure you into art school.”

“Every athlete, every musician practices every day. Why should it be different for artists?”

“Likes and shares sound like impact when in reality they often just represent superficial affirmation of a spiffy drawing or a cute idea.

I’m very doubtful about the power of art to change the world. Its inherent simplification makes it much better suited to preach to the converted or offend a political opponent than to bring about real social or political change. If I get a thousands likes for a drawing to save a rare animal, who’s the beneficiary: mother earth or my artistic ego?

But even if my work can never stop a tyrant or global warming, I inevitably contribute to how our world is perceived.

Here’s an uncomfortable question: If I believe in equality, and my personal and professional environment is actually very diverse, why do 90 percent of my cartoons feature middle-age white men?”

“This is a drawing I did for the New Yorker about people being shockingly uneducated in financial matters. The idea behind it employs a standard technique: Take visual cliché (the piggy bank, which represents financial matters) and give it a small twist (put a coin in its mouth instead of the slot in its back).

The person in the drawing should represent all people. Statistically there are more women than men in the United States. If I want to visualize people, shouldn’t I draw a woman instead of a man?

But how will that affect the intended meaning? Is the message still ‘Everyone is stupid,’ or does it change to ‘Women are stupid’?

I sense there is still bias in the media: A man in a funny drawing will be perceived as a person, whereas a woman will be perceived as a woman. When I choose to draw a man, I’m trying to prevent readers from misunderstanding the image.

Then again, my illustrations are often published in large magazines, so I kind of am The Media. I ask myself if—despite my good intentions—I perpetuate an antiquated world view.”

“This might be the most important skill you can have as an artist: Open your mind as wide as you can and check out every connection between any two elements. Most of these experiments yield nothing, but somewhere in this ocean of meaningless gibberish, something might click.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Crossroads of Should and Must: Thoughts

The Crossroads of Should and Must (Elle Luna)

This book came to me at exactly the right time. Or maybe any time would have been the right time—because I feel like this crossroads of Should and Must has been following me for years, and will continue to pester me as long as I avoid making a choice. Elle Luna, the author, was a designer herself, and I guess I got to reading this book both through divine movement and through a desperate searching for what I want my life to become.

My next step is to dig a little deeper into my Must, so that I can really define what it is. I know that seeing other artists launch their creative projects makes me come alive. I care about education, I care about representation, and I care about expressing our full range of emotions. How will all of these tie together, and integrate with my professional life?

It was a bit difficult to format these excerpts because the book is part painting and part text, but here’s an attempt to capture some of my favorite quotes:

“All too often, we feel that we are not living the fullness of our lives because we are not expressing the fullness of our gifts.”

“Bill Moyers:

Do you ever have the sense of... being helped by hidden hands?

Joseph Campbell:

All the time. It is miraculous. I even have a superstition that has grown on me as a result of invisible hands coming all the time—namely, that if you do follow your bliss you put yourself on a track that has been there all the while, waiting for you. And the life that you ought to be living is the one you are living. When you can see that, you begin to meet people who are in your field of bliss, and they open doors to you. I say, follow your bliss and don’t be afraid, and doors will open where you didn’t know they were going to be.

- Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth”

“There are two paths in life: Should and Must. We arrive at this crossroads over and over again. And every day, we get to choose.

Should is how other people want us to live our lives.

It’s all of the expectations that others layer upon us. Sometimes, Shoulds are small, seemingly innocuous, and easily accommodated. ‘You should listen to that song,’ for example. At other times, Shoulds are highly influential systems of thought that pressure and, at their most destructive, coerce us to live our lives differently.

When we choose Should, we’re choosing to live our life for someone or something other than ourselves. The journey to Should can be smooth, the rewards can seem clear, and the options are often plentiful.

Must is different.

Must is who we are, what we believe, and what we do when we are alone with our truest, most authentic self. It’s that which calls to us most deeply. It’s our convictions, our passions, our deepest held urges and desires—unavoidable, undeniable, and inexplicable. Unlike Should, Must doesn’t accept compromises.

Must is when we stop conforming to other people’s ideals and start connecting to our own—and this allows us to cultivate our full potential as individuals. To choose Must is to say yes to hard work and constant effort, to say yes to a journey without a road map or guarantees, and in so doing, to say yes to what Joseph Campbell called ‘the experience of being alive, so that our life experiences on the purely physical plane will have resonance within our innermost being and reality, so that we actually feel the rapture of being alive.’

Choosing Must is the greatest thing we can do with our lives.”

“‘What am I in the eyes of most people—a nonentity, an eccentric, or an unpleasant person—somebody who has no position in society and will never have; in short, the lowest of the low. All right, then—even if that were absolutely true, then I should like to show by my work what such an eccentric, such a nobody, has in his heart.’

- Vincent van Gogh”

“Removing Should is hard and time-consuming. Because in order to remove it, we must first understand it, get to know it—intimately. We need to know each Should’s origins, how it got there, and when we first began to integrate it into our decision-making. Look for recurring patterns, and choices—both little and big—that are affected. How often do we place blame on the person, job, or situation when the real problem, the real pain, is within us? And we leave and walk away, angry, frustrated, and sad, unconsciously carrying the same Shoulds into a new context—the next relationship, the next job, the next friendship—hoping for different results. But so long as we leave Should unexamined, the pattern repeats. And while running from Should certainly sounds easier and more pleasant, we must get to know Should if we want to release its invisible grip from our everyday decision-making.

If you’re ready to get to know your Shoulds, you can. Here’s one way.

Grab a piece of paper, and make a list of the Shoulds you hold on to by completing the sentences from the previous page. You can add more and repeat them if you want. Listen to what comes up first and write it down without thinking too much. Even if it doesn’t make sense right now, it contains a grain of truth worth capturing.

Look at your list one by one, and ask the following three questions:

Where did you come from?

Are you true for me?

Do I want to keep holding on to you?

List of sentences:

You should never ___.

You should always ___.

You should know better than to ___.

You should not ___.”

“‘If you can see your path laid out in front of you step by step, you know it’s not your path,’ Joseph Campbell said. ‘Your own path you make with every step you take. That’s why it’s your path.’”

“The very notion of having a calling—that you must have one—can be a nonstarter. It feels overwhelming. How do I find it? Daunting. What if it changes over time? Oppressive, even. Does everybody have one?

Thinking that your Must will appear, fully formed, is like believing you can write a book by wishing and thinking. But doing one small thing, daily—pick up the pen, write a paragraph, make a list of words—that is how your Must will appear.”

“Look within.

Must is always with you, wherever you are, whatever you’re doing. Must is you. Sometimes, Must can feel really far away, but it will never leave you. You just might not see it yet.

If you had one day to pursue some idea, activity, or project, what are three things that come to mind first?

Things you do just for fun: ____ ____ ____

Something a friend does that you feel envious about: ____

Things you do when you’re procrastinating: ____

Fantasies: ____

An activity that gives you chills: ____

Sights, smells, sounds, or sensations that give you butterflies in your stomach...”

“When we discover our Must, the brain’s most primal, protective center gets alarmed. The riot gear is called forth. Defense mechanisms go up. Because choosing Must raises very real and scary questions.

If I want to choose Must, when do I start?

How might I find more time in my day?

How long is this going to take?

How will I pay rent?

Do I have to quit my job?

What if I can’t grow within a company that I love? What then? Will I let people down? (but everyone is counting on me.)

How might I create a safe space to explore within my existing reality?

What if I try to find my calling and I don’t find it?

Do my ideas matter?”

“What if doing what I love doesn’t pay?

If you want to get by on this planet, you must make money.

If you have obligations or a family or a mortgage, you must make more money. If doing what you love doesn’t pay the bills, then you must find another way to make money. Period. Being able to pay your bills can create the temporal and mental space to find your calling.

A job, a career, a calling.

The author T. S. Eliot was also a banker. Another writer, Kurt Vonnegut, sold cars. One of the greatest composers of our time, Philip Glass, didn��t earn a living from his calling making music until he was forty-two. Even as his work was premiering at the Met, he worked as a plumber and renewed his taxi license, just in case.

You might have a nine-to-five job while you pursue your calling on nights and weekends. Or you might focus on your calling full-time and make a living from it. There are many options to choose from, and there is dignity in all work. Just because you have a job to pay the bills does not make it dirty. And just because you want to find your calling does not mean you need to quit your job. You get to play with these three types of work and decide what’s right for you and your life.”

“So long as you keep your eye on your Must and optimize your time and energy to sustain it as best you can, you can continue to adjust and experiment with how you make money.

Maybe you’ll get paid to do what you love. Or maybe you’ll take a job where the hours are clearly defined, the work isn’t too exhausting, and you have energy to pursue your Must on nights and weekends.

But what you don’t want is to take a job that was intended to pay the bills and suddenly, you don’t have time to explore your passion, you’re too tired to step into that which you were put on this earth to do. And if, for some awful reason, you forget that money is a game, a make-believe concept that some people invented, you could be led back into the complex layered world of Should. And here, the loss isn’t a financial one. You are the cost. Is it worth it?”

“There are two types of money—Must-Have and Nice-to-Have. Must-Have money is a solid, fixed number that we do not want to risk not having. We will not be able to focus on our Must if we are worried about not being able to eat. This number is often smaller than you might assume. At its most basic, it includes food and shelter.

Nice-to-Have money is extra, above-and-beyond money. Too often, we confuse Nice-to-Have money with Must-Have. Just because something is valuable doesn’t mean that we need it. It will always be nicer to have more Nice-to-Have money.”

“Time is the second perceived stumbling block to Must.

‘I’ll make time after things settle down at the office...’

‘... when the kids are off to school...’

You make time for what you want.”

“We all have a net of obligations and time constraints—both real and imagined. The most effective way to find you Must is to find ten minutes. Because while running away from all of your obligations to focus uninterrupted on your Must for months sounds romantic, the harder, trickier, and more sustainable way is to make shifts every day within your existing reality. To integrate, not obliterate.”

“Must needs solitude.

Solitude is how we quiet the voices, the incessant chatter. It’s how we create the necessary calm, empty spaces. Vision needs solitude. Leadership needs solitude. Courage needs solitude. Because when our choices evolve from an internal place of sure-footed, rooted knowing, we become resilient, emboldened, and focused.”

“‘Every morning upon awakening, I experience a supreme pleasure: That of being Salvador Dalí, and I ask myself, wonderstruck, what prodigious thing will he do today, this Salvador Dalí.’

- Salvador Dalí, painter”

“Must is a choice you make every single day. Today. Tomorrow. Again and again. Must.

It is constant effort and hard work—and inexplicably life-affirming—to honor who you are, what you believe, and why you are here. To choose Must is the greatest thing you can do with your life because this congruent, rooted way of living shines through everything that you do. Your sacred space and daily efforts will become even more sacred. You will build a beautiful world for your Must. And over time, it will be tempting to stay forever in this magical place that you’ve created, never to return to the everyday world again. But the complete and ultimate journey requires that you return, share your Must, and in so doing, lift the lives of others.”

“After building apps and websites that were available on phones anywhere for anyone, I couldn’t shake the feeling of solitariness that I had about making art. Unlike design, painting didn’t involve user research, and there was no target audience to keep in mind. It was just me, in a room, alone, making art. My concern grew.

When does this intersect with the rest of the world?

Must feels inherently selfish at first. But when you choose Must, you inspire others to choose it, too. When you follow Must every day, you impact not only what you create for your work, but also who you become in your life. This is how your work and your life become one and the same. When you choose Must, what you create is yourself. It is a body of work. As you change, so too does the work. As you grow, so too does the creation.”

“‘Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.’

- Howard Thurman, philosopher”

“If you believe that you have something special inside of you, and you feel it’s about time you gave it a shot, honor that calling in some small way—today. If you feel a knot in your stomach because you can see the enormous distance between your dreams and your daily reality, do one thing to tighten your grip on what you want—today. If you’ve been peering down the road to Must but can’t quite make the choice, dig a little deeper and find out what’s stopping you—today. Because there is a recurring choice in life, and it occurs at the intersection of two roads. We arrive at this place again and again.”

0 notes

Text

The War of Art: Thoughts

The War of Art (Steven Pressfield)

The back cover of this book reads, “Steven Pressfield shows readers how to identify, defeat, and unlock the inner barriers to creativity.”

I started reading The War of Art because my friend told me it was one of his “life-changing books.” I’m still processing everything in the book, but it might turn out that way for me too: Some parts of the book spoke so deeply to me that they’ve actually changed my mind about the kind of art I want to make. Of course, no one person can describe the experience of all artists, but there are still messages that resonated intensely with me and made me question my daily assumptions. Some of the things I need to think about coming out of this book:

How do I “turn pro” with my art?

What things in my life cause Resistance? How will I overcome them?

What kind of art do I want to make? Rather than pandering to an audience, what is the message in my heart that I need to pour out, even if I were the last person on Earth?

Why am I making my art? Who is it for? How can I make my art an offering to God?

Here are some especially memorable passages:

On the Resistance and our genius:

“Late at night have you experienced a vision of the person you might become, the work you could accomplish, the realized being you were meant to be? Are you a writer who doesn’t write, a painter who doesn’t paint, an entrepreneur who never starts a venture? Then you know what Resistance is.... To yield to Resistance deforms our spirit. It stunts us and makes us less than we are and were born to be. If you believe in God (and I do) you must declare Resistance evil, for it prevents us from achieving the life God intended when He endowed each of us with our own unique genius. Genius is a Latin word; the Romans used it to denote an inner spirit, holy and inviolable, which watches over us, guiding us to our calling. A writer writes with his genius; an artist paints with hers; everyone who creates operates from this sacramental center. It is our soul’s seat, the vessel that holds our being-in-potential, our star’s beacon and Polaris.”

On using Resistance as a compass:

“Like a magnetized needle floating on a surface of oil, Resistance will unfailingly point to true North—meaning that calling or action it most wants to stop us from doing.

We can use this. We can use it as a compass. We can navigate by Resistance, letting it guide us to that calling or action that we must follow before all others.

Rule of thumb: The more important a call or action is to our soul’s evolution, the more Resistance we will feel toward pursuing it.”

On Resistance never going away:

“Henry Fonda was still throwing up before each stage performance, even when he was seventy-five. In other words, fear doesn’t go away. The warrior and the artist live by the same code of necessity, which dictates that the battle must be fought anew every day.”

On sabotage:

“When a writer begins to overcome her Resistance—in other words, when she actually starts to write—she may find that those close to her begin acting strange. They may become moody or sullen, they may get sick; they may accuse the awakening writer of “changing,” of “not being the person she was.” The closer these people are to the awakening writer, the more bizarrely they will act and the more emotion they will put behind their actions.

They are trying to sabotage her.

The reason is that they are struggling, consciously or unconsciously, against their own Resistance. The awakening writer’s success becomes a reproach to them. If she can beat these demons, why can’t they?

Often couples or close friends, even entire families, will enter into tacit compacts whereby each individual pledges (unconsciously) to remain mired in the same slough in which she and all her cronies have become so comfortable. The highest treason a crab can commit is to make a leap for the rim of the bucket.”

On procrastination:

“Procrastination is the most common manifestation of Resistance because it’s the easiest to rationalize. We don’t tell ourselves, ‘I’m never going to write my symphony.’ Instead we say, ‘I am going to write my symphony; I’m just going to start tomorrow.’

The most pernicious aspect of procrastination is that it can become a habit. We don’t just put off our lives today; we put them off till our deathbed.

Never forget: This very moment, we can change our lives. There never was a moment, and never will be, when we are without the power to alter our destiny. This second, we can turn the tables on Resistance.

This second, we can sit down and do our work.”

On the unhappiness caused by Resistance:

“What does Resistance feel like?

First, unhappiness. We feel like hell. A low-grade misery pervades everything. We’re bored, we’re restless. We can’t get no satisfaction. There’s guilt but we can’t put our finger on the source. We want to go back to bed; we want to get up and party. We feel unloved and unlovable. We’re disgusted. We hate our lives. We hate ourselves.”

On freedom:

“It may be that the human race is not ready for freedom. The air of liberty may be too rarefied for us to breathe. Certainly I wouldn’t be writing this book, on this subject, if living with freedom were easy. The paradox seems to be, as Socrates demonstrated long ago, that the truly free individual is free only to the extent of his own self-mastery. While those who will not govern themselves are condemned to find masters to govern over them.”

On self-doubt and love:

“Self-doubt can be an ally. This is because it serves as an indicator of aspiration. It reflects love, love of something we dream of doing, and desire, desire to do it. If you find yourself asking yourself (and your friends), ‘Am I really a writer? Am I really an artist?’ chances are you are.

The counterfeit innovator is wildly self-confident. The real one is scared to death.”

On love:

“Resistance is directly proportional to love. If you’re feeling massive Resistance, the good news is, it means there’s tremendous love there too. If you didn’t love the project that is terrifying you, you wouldn’t feel anything. The opposite of love isn’t hate; it’s indifference.

The more Resistance you experience, the more important your unmanifested art/project/enterprise is to you—and the more gratification you will feel when you finally do it.”

On professionals and amateurs:

“Aspiring artists defeated by Resistance share one trait. They all think like amateurs. They have not yet turned pro.

The moment an artist turns pro is epochal as the birth of his first child. With one stroke, everything changes. I can state absolutely that the term of my life can be divided into two parts: before turning pro, and after.

To be clear: When I say professional, I don’t mean doctors and lawyers, those of ‘the professions.’ I mean the Professional as an ideal. The professional in contrast to the amateur. Consider the differences.

The amateur plays for fun. The professional plays for keeps.

To the amateur, the game is his avocation. To the pro it’s his vocation.

The amateur plays part-time, the professional full-time.

The amateur is a weekend warrior. The professional is there seven days a week.

The word amateur comes from the Latin root meaning ‘to love.’ The conventional interpretation is that the amateur pursues his calling out of love, while the pro does it for money. Not the way I see it. In my view, the amateur does not love the game enough. If he did, he would not pursue it as a sideline, distinct from his ‘real’ vocation.

The professional loves it so much he dedicates his life to it. He commits full-time.

That’s what I mean when I say turning pro.

Resistance hates it when we turn pro.”

On Pressfield’s daily life:

“I wake up with a gnawing sensation of dissatisfaction. Already I feel fear. Already the loved ones around me are starting to fade. I interact. I’m present. But I’m not.

I’m not thinking about the work. I’ve already consigned that to the Muse. What I am aware of is Resistance. I feel it in my guts. I afford it the utmost respect, because I know it can defeat me on any given day as easily as the need for a drink can overcome an alcoholic.

I go through the chores, the correspondence, the obligations of daily life. Again I’m there but not really. The clock is running in my head; I know I can indulge in daily crap for a little while, but I must cut it off when the bell rings.

I’m keenly aware of the Principle of Priority, which states (a) you must know the difference between what is urgent and what is important, and (b) you must do what’s important first.

What’s important is the work. That’s the game I have to suit up for. That’s the field on which I have to leave everything I’ve got.

Do I really believe that my work is crucial to the planet’s survival? Of course not. But it’s as important to me as catching that mouse is to the hawk circling outside my window. He’s hungry. He needs a kill. So do I.”

On already being a pro:

“All of us are pros in one area: our jobs.

We get a paycheck. We work for money. We are professionals.

Now: Are there principles we can take from what we’re already successfully doing in our workaday life and apply to our artistic aspirations? What exactly are the qualities that define us as professionals?

1) We show up every day. We might do it only because we have to, to keep from getting fired. But we do it. We show up every day.

2) We show up no matter what. In sickness and in health, come hell or high water, we stagger in to the factory. We might do it only so as not to let down our co-workers, or for other, less noble reasons. But we do it. We show up no matter what.

3) We stay on the job all day. Our minds may wander, but our bodies remain at the wheel. We pick up the phone when it rings, we assist the customer when he seeks our help. We don’t go home till the whistle blows.

4) We are committed over the long haul. Next year we may go to another job, another company, another country. But we’ll still be working. Until we hit the lottery, we are part of the labor force.

5) The stakes for us are high and real. This is about survival, feeding our families, educating our children. It’s about eating.

6) We accept remuneration for our labor. We’re not here for fun. We work for money.

7) We do not overidentify with our jobs. We may take pride in our work, we may stay late and come in on weekends, but we recognize that we are not our job descriptions. The amateur, on the other hand, overidentifies with his avocation, his artistic aspiration. He defines himself by it. He is a musician, a painter, a playwright. Resistance loves this. Resistance knows that the amateur composer will never write his symphony because he is overly invested in its success and overterrified of its failure. The amateur takes it so seriously it paralyzes him.

8) We master the technique of our jobs.

9) We have a sense of humor about our jobs.

10) We receive praise or blame in the real world.

Now consider the amateur: the aspiring painter, the wannabe playwright. How does he pursue his calling?

One, he doesn’t show up every day. Two, he doesn’t show up no matter what. Three, he doesn’t stay on the job all day. He is not committed over the long haul; the stakes for him are illusory and fake. He does not get money. And he overidentifies with his art. He does not have a sense of humor about failure. You don’t hear him bitching, ‘This fucking trilogy is killing me!’ Instead, he doesn’t write his trilogy at all.”

On the payoff of going pro:

“Remember what we said about fear, love, and Resistance. The more you love your art/calling/enterprise, the more important its accomplishment is to the evolution of your soul, the more you will fear it and the more Resistance you will experience facing it. The payoff of playing-the-game-for-money is not the money (which you may never see anyway, even after you turn pro). The payoff is that playing the game for money produces the proper professional attitude. It inculcates the lunch-pail mentality, the hard-core, hard-head, hard-hat state of mind that shows up for work despite rain or snow or dark of night and slugs it out day after day.”

On Resistance and enthusiasm:

“Resistance outwits the amateur with the oldest trick in the book: It uses his own enthusiasm against him. Resistance gets us to plunge into a project with an overambitious and unrealistic timetable for its completion. It knows we can’t sustain that level of intensity. We will hit the wall. We will crash.

The professional, on the other hand, understands delayed gratification. He is the ant, not the grasshopper; the tortoise, not the hare. Have you heard the legend of Sylvester Stallone staying up three nights straight to churn out the screenplay for Rocky? I don’t know, it may even be true. But it’s the most pernicious species of myth to set before the awakening writer, because it seduces him into believing he can pull off the big score without pain and without persistence.

The professional arms himself with patience, not only to give the stars time to align in his career, but to keep himself from flaming out in each individual work. He knows that any job, whether it’s a novel or a kitchen remodel, takes twice as long as he thinks and costs twice as much. He accepts that. He recognizes it as reality.”

On order:

“When I lived in the back of my Chevy van, I had to dig my typewriter out from beneath layers of tire tools, dirty laundry, and moldering paperbacks. My truck was a nest, a hive, a hellhole on wheels whose sleeping surface I had to clear each night just to carve out a foxhole to snooze in.

The professional cannot live like that. He is on a mission. He will not tolerate disorder. He eliminates chaos from his world in order to banish it from his mind. He wants the carpet vacuumed and the threshold swept, so that Muse may enter and not soil her gown.”

On excuses:

“The amateur, underestimating Resistance’s cunning, permits the flu to keep him from his chapters; he believes the serpent’s voice in his head that says mailing off the manuscript is more important than doing the day’s work.

The professional has learned better. He respects Resistance. He knows if he caves in today, no matter how plausible the pretext, he’ll be twice as likely to cave in tomorrow.

The professional knows that Resistance is like a telemarketer; if you so much as say hello, you’re finished. The pro doesn’t even pick up the phone. He stays at work.”

On preparation:

“I’m not talking about craft; that goes without saying. The professional is prepared at a deeper level. He is prepared, each day, to confront his own self-sabotage.

The professional understands that Resistance is fertile and ingenious. It will throw stuff at him that he’s never seen before.

The professional prepares mentally to absorb blows and to deliver them. His aim is to take what the day gives him. He is prepared to be prudent and prepared to be reckless, to take a beating when he has to, and to go for the throat when he can. He understands that the field alters every day. His goal is not victory (success will come by itself when it wants to) but to handle himself, his insides, as sturdily and steadily as he can.”

On external feedback:

“The professional cannot allow the actions of others to define his reality. Tomorrow morning the critic will be gone, but the writer will still be there facing the blank page. Nothing matters but that he keep working. Short of a family crisis or the outbreak of World War III, the professional shows up, ready to serve the gods.

Remember, Resistance wants us to cede sovereignty to others. It wants us to stake our self-worth, our identity, our reason-for-being, on the response of others to our work. Resistance knows we can’t take this. No one can.”

On going pro being a decision:

“There’s no mystery to turning pro. It’s a decision brought about by an act of will. We make up our mind to view ourselves as pros and we do it. Simple as that.”

On the mystery that arises from work:

“Why have I stressed professionalism so heavily in the preceding chapters? Because the most important thing about art is to work. Nothing else matters except sitting down every day and trying.

Why is this so important?

Because when we sit down day after day and keep grinding, something mysterious starts to happen. A process is set into motion by which, inevitably and infallibly, heaven comes to our aid. Unseen forces enlist in our cause; serendipity reinforces our purpose.

This is the other secret that real artists know and wannabe writers don’t. When we sit down each day and do our work, power concentrates around us. The Muse takes note of our dedication. She approves. We have earned favor in her sight. When we sit down and work, we become like a magnetized rod that attracts iron fillings. Ideas come. Insights accrete.

Just as Resistance has its seat in hell, so Creation has its home in heaven. And it’s not just a witness, but an eager and active ally.”

On working and providence:

“Concerning all acts of initiative (and creation) there is one elementary truth, the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would not otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favour all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance which no man would have dreamed would come his way. I have learned a deep respect for one of Goethe’s couplets: ‘Whatever you can do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, magic, and power in it. Begin it now.’

—W. H. Murray, The Scottish Himalayan Expedition”

On what the Self believes:

“4) The supreme emotion is love. Union and mutual assistance are the imperatives of life. We are all in this together.

5) God is all there is. Everything that is, is God in one form or another. God, the divine ground, is that in which we live and move and have our being. Infinite planes of reality exist, all created by, sustained by and infused by the spirit of God.”

On doing what the Ego hates:

“The instinct that pulls us toward art is the impulse to evolve, to learn, to heighten and elevate our consciousness. The Ego hates this. Because the more awake was become, the less we need the Ego.

The Ego hates it when the awakening writer sits down at the typewriter.

The Ego hates it when the aspiring painter steps up before the easel.

The Ego hates it because it knows that these souls are awakening to a call, and that that call comes from a plane nobler than the material one and from a source deeper and more powerful than the physical.”

On why hierarchy is fatal:

“For the artist to define himself hierarchically is fatal.

Let’s examine why. First, let’s look at what happens in a hierarchical orientation.

An individual who defines himself by his place in a pecking order will:

1) Complete against all others in the order, seeking to elevate his station by advancing against those above him, while defending his place against those beneath.

2) Evaluate his happiness/success/achievement by his rank within the hierarchy, feeling most satisfied when he’s high and most miserable when he’s low.

3) Act toward others based upon their rank in the hierarchy, to the exclusion of all other factors.

4) Evaluate his every move solely by the effect it produces on others. He will act for others, dress for others, speak for others, think for others.

But the artist cannot look to others to validate his efforts or his calling....

In the hierarchy, the artist faces outward. Meeting someone new his asks himself, ‘What can this person do for me? How can this person advance my standing?’

In the hierarchy, the artist looks up and looks down. The one place he can’t look is that place he must: within.”

On being a hack:

“I learned this from Robert McKee. A hack, he says, is a writer who second-guesses his audience. When the hack sits down to work, he doesn’t ask himself what’s in his own heart. He asks what the market is looking for.

The hack condescends to his audience. He thinks he’s superior to them. The truth is, he’s scared to death of them or, more accurately, scared of being authentic in front of them, scared of writing what he really feels or believes, what he himself thinks is interesting. He’s afraid it won’t sell. So he tries to anticipate what the market (a telling word) wants, then gives it to them.”

On bringing forth what is inside of us:

“Instead let’s ask ourselves like that new mother: What do I feel growing inside me? Let me bring that forth, if I can, for its own sake and not for what it can do for me or how it can advance my standing.”

On the difference between territory and hierarchy:

“How can we tell if our orientation is territorial or hierarchical?

One way is to ask ourselves, If I were feeling really anxious, what would I do? If we would pick up the phone and call six friends, one after the other, with the aim of hearing their voices and reassuring ourselves that they still love us, we’re operating hierarchically.

We’re seeking the good opinion of others.

What would Arnold Schwarzenegger do on a freaky day? He wouldn’t phone his buddies; he’d head for the gym. He wouldn’t care if the place was empty, if he didn’t say a word to a soul. He knows that working out, all by itself, is enough to bring him back to his center.

His orientation is territorial.

Here’s another test. Of any activity you do, ask yourself: If I were the last person on earth, would I still do it?

If you’re all alone on the planet, a hierarchical orientation makes no sense. There’s no one to impress. So, if you’d still pursue that activity, congratulations. you’re doing it territorially.”

On offering our work to God:

“When Krishna instructed Arjuna that we have a right to our labor but not to the fruits of our labor, he was counseling the warrior to act territorially, not hierarchically. We must do our work for its own sake, not for fortune or attention or applause.

Then there’s the third way proffered by the Lord of Discipline, which is beyond both hierarchy and territory. That is to do the work and give it to Him. Do it as an offering to God.

‘Give the act to me.

Purged of hope and ego,

Fix your attention on the soul.

Act and do for me.’

The work comes from heaven anyway. Why not give it back?

To labor in this way, The Bhagavad-Gita tells us, is a form of meditation and a supreme species of spiritual devotion. It also, I believe, conforms most closely to Higher Reality. In fact, we are servants of the Mystery. We were put here on earth to act as agents of the Infinite, to bring into existence that which is not yet, but which will be, through us.

Every breath we take, every heartbeat, every evolution of every cell comes from God and is sustained by God every second, just as every creation, invention, every bar of music or line of verse, every thought, vision, fantasy, every dumb-ass flop and stroke of genius comes from that infinite intelligence that created us and the universe in all its dimensions, out of the Void, the field of infinite potential, primal chaos, the Muse. To acknowledge that reality, to efface all ego, to let the work come through us and give it back freely to its source, that, in my opinion, is as true to reality as it gets.”

On the artist’s duty:

“Are you a born writer? Were you put on earth to be a painter, a scientist, an apostle of peace? In the end the question can only be answered by action.

Do it or don’t do it.

It may help to think of it this way. If you were meant to cure cancer or write a symphony or crack cold fusion and you don’t do it, you not only hurt yourself, even destroy yourself. You hurt your children. You hurt me. You hurt the planet.

You shame the angels who watch over you and you spite the Almighty, who created you and only you with your unique gifts, for the sole purpose of nudging the human race one millimeter farther along its path back to God.

Creative work is not a selfish act or a bid for attention on the part of the actor. It’s a gift to the world and every being in it. Don’t cheat us of your contribution. Give us what you’ve got.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I haven’t been posting much art here (go to my instagram: @petrichorate for much more frequent art updates!), but figured I would start putting up a little more on my blog... mainly reserving my blog for reading notes and thoughts though :)

0 notes

Photo

I eventually turned this into a repeating pattern, but I also like the centerpiece of flowers on a simple pink background :) flowers for a busy afternoon!

0 notes

Text

Little Fires Everywhere: Thoughts

Little Fires Everywhere (Celeste Ng)

I feel like Little Fires Everywhere is like a trap of sorts—it draws you in quickly, under the pretense of some light entertainment, and then hits you hard with moments of intense poignancy and frustration. I wanted to read more books by Asian American authors this year because I wanted to come to terms with my identity as a Chinese American. I needed to understand how I had been approaching that part of myself, and also to hear the stories of other people who had gone through the same thing—especially if those experiences were sometimes shameful, terrifying, or filled with guilt, as mine have often been. It wasn’t until college that I started being proud of my heritage; there are still moments when I unfortunately feel ashamed of that part of myself, or somehow feel lesser than those around me. But I’ve also started to appreciate the unique beauty of being Asian American—the amazing resilience and reflection I’ve received by being part of a culture that is complex, and contradictory, and somehow immensely messed up and exquisite at the same time.

Little Fires Everywhere managed to pack so much about Asian American-ness, motherhood, and self identity into a seamless narrative. I remember messaging a friend at the beginning of the novel that “it was entertaining, but seems like just a light read. I kind of expected it to push more on Asian American issues.” But the more I read, the more I realized that there were lessons interwoven throughout the story that could only have been learned through intense, real experiences. I love how Ng describes the “sureness” possessed in children from wealthy and established families—a feeling I always got from my childhood friends who lived in houses with kitchen islands in nice neighborhoods, but that I never felt I held inside myself. I love how Ed Lim, the lawyer, reflects on the difficulty of finding books and dolls that his daughter can relate to—it’s something I noticed in all my picture books about kids with curly golden hair, and it’s something I am actively working on because I don’t want my future daughter or son growing up without characters who look like them.

Here are some parts I thought were particularly memorable:

On stealing from people who don’t notice:

“She had cried all the way to Lafayette, where they would stay for the next eight months, and even the prancing china palomino she had stolen from the girl’s collection gave her no comfort, for though she waited nervously, there was never any complaint about the loss, and what could be less satisfying than stealing from someone so endowed that they never even noticed what you’d taken?”

On the “sureness” or efficacy felt in people from established families:

“Even the younger Richardsons had it, this sureness in themselves. Sunday mornings Pearl and Moody would be sitting in the kitchen when Trip drifted in from a run, lounging against the island to pour a glass of juice, tall and tan and lean in gym shorts, utterly at ease, his sudden grin throwing her into disarray. Lexie perched at the counter, inelegant in sweatpants and a tee, hair clipped in an untidy bun, picking sesame seeds off a bagel. They did not care if Pearl saw them this way. They were so artlessly beautiful, even right out of bed. Where did this ease come from? How could they be so at home, so sure of themselves, even in pajamas? When Lexie ordered from a menu, she never said, ‘Could I have...?’ She said, ‘I’ll have...’ confidently, as if she had only to say it to make it so. It unsettled Pearl and it fascinated her.”

On covering up naïveté with “bookish wisdom”:

“She could see the similarities between these two lonely children, even more clearly than they could: the same sensitive personalities lurking inside both of them, the same bookish wisdom layered over a deep naïveté.”

On the ability of wealth to draw you away from the problems you want to solve:

“Of course she understood why this was happening: they were fighting to right injustices. But part of her shuddered at the scenes on the television screen. Grainy scenes, but no less terrifying: grocery stores ablaze, smoke billowing from their rooftops, walls gnawed to studs by flame. The jagged edges of smashed windows like fangs in the night. Soldiers marching with rifles past drugstores and Laundromats. Jeeps blocking intersections under dead traffic lights. Did you have to burn down the old to make way for the new? The carpet at her feet was soft. The sofa beneath her was patterned with roses. Outside, a mourning dove cooed from the bird feeder and a Cadillac glided to a dignified stop at the corner. She wondered which was the real world.

The following spring, when antiwar protests broke out, she did not get in her car and drive to join them. She wrote impassioned letters to the editor; she signed petitions to end the draft. She stitched a peace sign onto her knapsack. She wove flowers into her hair.”

On parents and touch:

“Parents, she thought, learned to survive touching their children less and less. As a baby Pearl had clung to her; she’d worn Pearl in a sling because whenever she’d set her down, Pearl would cry. There’d scarcely been a moment in the day when they had not been pressed together. As she got older, Pearl would still cling to her mother’s leg, then her waist, then her hand, as if there were something in her mother she needed to absorb through the skin. Even when she had her own bed, she would often crawl into Mia’s in the middle of the night and burrow under the old patchwork quilt, and in the morning they would wake up tangled, Mia’s arm pinned beneath Pearl’s head, or Pearl’s legs thrown across Mia’s belly. Now, as a teenager, Pearl’s caresses had become rare—a peck on the cheek, a one-armed, half-hearted hug—and all the more precious because of that. It was the way of things, Mia thought to herself, but how hard it was. The occasional embrace, a head leaned for just a moment on your shoulder, when what you really wanted more than anything was to press them to you and hold them so tight you fused together and could never be taken apart. It was like training yourself to live on the smell of an apple alone, when what you really wanted was to devour it, to sink your teeth into it and consume it, seeds, core, and all.”

On regrets:

“‘Most of the time, everyone deserves more than one chance. We all do things we regret now and then. You just have to carry them with you.’”

On the lack of good Asian representation in toys for kids:

“But there was no doll with black hair, let alone a face that looked anything like Monique’s. Ed Lim had gone to four different toy stores searching for a Chinese doll; he would have bought it for his daughter, whatever the price, but no such thing existed.

He’d gone so far as to write to Mattel, asking them if there was a Chinese Barbie doll, and they’d replied that yes, they offered ‘Oriental Barbie’ and sent him a pamphlet. He had looked at that pamphlet for a long time, at the Barbie’s strange mishmash of a costume, all red and gold satin and like nothing he’d ever seen on a Chinese or Japanese or Korean woman, at her waist-length black hair and slanted eyes. I am from Hong Kong, the pamphlet ran. It is in the Orient, or Far East. Throughout the Orient, people shop at outdoor marketplaces where goods such as fish, vegetables, silk, and spices are openly displayed. The year before, he and his wife and Monique had gone on a trip to Hong Kong, which struck him, mostly, as a pincushion of gleaming skyscrapers. In a giant, glassed-in shopping mall, he’d bought a dove-gray cashmere sweater that he wore under his suit jacket on chilly days. Come visit the Orient. I know you will find it exotic and interesting.

In the end, he’d thrown the pamphlet away. He’d heard, from friends with younger children, that the expensive doll line now had one Asian doll for sale—and a few black ones, too—but he’d never seen it. Monique was seventeen now, and had long outgrown dolls.”

On the frustration of people finally recognizing problems that you have always known about through real experience and not research studies:

“‘What about other books, Mrs. McCullough? Any other books with Chinese characters?’

Mrs. McCullough bit her lip. ‘I haven’t really looked for them,’ she admitted. ‘I hadn’t thought about it.’

‘I can save you some time,’ said Ed Lim. ‘There really aren’t very many. So May Ling has no dollars that look like her, and no books with pictures of people that look like her.’ Ed Lim paced a few more steps. Nearly two decades later, others would raise this question, would talk about books as mirrors and windows, and Ed Lim, tired by then, would find himself as frustrated as he was grateful. We’ve always known, he would think; what took you so long?”

On what Asians are “allowed” to be in society:

“Men like him, the article would suggest, weren’t supposed to lose their cool—though it was never specified whether ‘like him’ meant lawyers or something else entirely. But the truth was—as Mr. Richardson recognized—that an angry Asian man didn’t fit the public’s expectations, and was therefore unnerving. Asian men could be socially inept and incompetent and ridiculous, like a Long Duk Dong, or at best unthreatening and slightly buffoonish, like a Jackie Chan. They were not allowed to be angry and articulate and powerful. And possibly right, Mr. Richardson thought uneasily.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A reimagining of the story of Persephone and Hades, inspired by the classical myth and Chinese folktales. Especially after reading Ken Liu’s The Paper Menagerie (a beautiful collection—it really pierced me to the core about my relationship to my culture and my family) I’ve been looking into Chinese folklore lately. I love the legends of the huli jing (fox spirits that transform into beautiful women) and the nian (mountain beasts who appear every new year), and I wanted to draw them into a story somehow!

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Phew! I have a huge backlog of illustrations that I’ve posted on my Instagram but not here. In any case, it’s summer! That means sunshine and dresses every day :)

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It’s the end of my time at IDEO 😢 I learned a ton here about what I need to improve to push my design work to the next level, how process can change the way we collaborate and think of ideas, and how important it is to share thoughts frequently and with lots of people! As a semi-ironic, semi-super-genuine parting reflection, I'm leaving a little doodle of some of the new phrases I picked up during the last few months here... Now for a short break before the next big adventure!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lincoln in the Bardo: Thoughts

Lincoln in the Bardo (George Saunders)

The weirdest thing happened the day after I finished Lincoln in the Bardo. When I got into my car, the radio started playing—I was about to switch to my own playlist when I heard someone say "George Saunders." The program was a re-run by KQED, an interview or lecture with George Saunders about his first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo. His journey of writing the novel is in itself a fascinating story (but you can look it up elsewhere). During the program, the interviewer mentioned that they were talking on the very same day that Willie Lincoln died years and year ago—so the day of the interview was actually the day the events in the book take place. Listening to the program, coincidentally starting at the same time I began driving, on the day right after having finished the book (after having had it on my to-read list for many months), was just... bizarre.

But anyway. Lincoln in the Bardo. The format of the novel is complicated, with fictional voices, real voices, historical and ghostly, all intertwined in a narrative that changes style every few paragraphs. In the interview, Saunders mentioned that the book was really difficult to read, so difficult (and different from his short stories) that he's received countless complaints and angry rants from readers who gave up halfway through. But he also said that if you persist, the book will teach you how to read itself—and the ending is that much more moving for having gone through the journey with the characters.

The book itself—it was beautiful, supremely empathetic, and hopeful. In general, I find Saunders's science fiction-oriented short stories fascinating but less personally interesting, and I felt the same way throughout much of Lincoln in the Bardo. But by the very end of the book, I was deeply touched by the characters—ghostly or not—and amazed at how Saunders can spin so many temperaments and personas into existence, all with backgrounds that both repulse and invite sympathy.

I think what this book did the most for me was create an overwhelming appreciation for everything—the “things of the world” that I hardly notice but that make me cry when I think about how lovely it is to have them around. Saunders himself explained the main question of the novel as “How do we live and love when we know that everything we love must end?” I’m still trying to work through that question (not that I think I will find a very thorough answer to it at all).

Here are a few excerpts I found particularly moving or interesting:

On the difference between the importance we place in a person versus what their fate might be:

“The terror and consternation of the Presidential couple may be imagined by anyone who has ever loved a child, and suffered that dread intimation common to all parents, that Fate may not hold that life in as high a regard, and may dispose of it at will.

(In “Selected Civil War Letters of Edwine Willow,” edited by Constance Mays.)”

A monologue from Willie Lincoln (the style is so moving):

“Mother says I may taste of the candy city Once I am up and about She has saved me a chocolate fish and a bee of honey Says I will someday command a regiment Live in a grand old house Marry some sweet & pretty thing Have little ones of my own Ha ha I like that All of us will meet in my grand old house and have a fine I will make the jolliest old lady, Mother says You boys will bring me cakes Round the clock While i just sit How fat I will be You boys must buy a cart and take turns wheeling me around ha ha

Mother has such a nice way of laughing

We are on the third stairstep Stairstep Number 3 That has three white roses on it Here is how it goes from Stairstep Number 1 to Stairstep Number 5 in number of white roses: 2, 3, 5, 2, 6

Mother comes in close Touches her nose to mine This is called “nee-nee” Which I find babyish But I still allow it from time to”

Bevins’s observations on beautiful earthly things and experiences:

“My goodness, I thought, poor fellow! You did not give this place a proper chance, but fled it recklessly, leaving behind forever the beautiful things of this world.

And for what?

You do not know.

A most unintelligent wager.

Forgoing eternally, sir, such things as, for example: two fresh-shorn lambs bleat in a new-mown field; four parallel blind-cast linear shadows creep across a sleeping tabby’s midday flank; down a bleached-slate roof and into a patch of wilting heather bounce nine gust-loosened acorns; up past a shaving fellow wafts the smell of a warming griddle (and early morning pot-clangs and kitchen-girl chatter); in a nearby harbor a mansion-sized schooner tilts to port, sent so by a flag-rippling, chime-inciting breeze that causes, in a port-side schoolyard, a chorus of childish squeals and the mad barking of what sounds like a dozen—

(roger bevins iii)”

Vollman and Bevins in Lincoln’s body, feeling Lincoln’s thoughts about Willie’s dead body and the Civil War:

“Broken.

Pale broken thing.

Why will it not work. What magic word made it work. Who is the keeper of that word. What did it profit Him to switch this one off. What a contraption it is. How did it ever run. What spark ran it. Grand little machine. Set up just so. Receiving the spark, it jumped to life.

What put out that spark? What a sin it would be. Who would dare. Ruin such a marvel. Hence is murder anathema. God forbid I should ever commit such a grievous—

(hans vollman)

Something then troubling us—

(roger bevins iii)

We ran one hand roughly over our face, as if attempting to suppress a notion just arising.

(hans vollman)”

Vollman in Lincoln’s body, more thoughts on death:

“Lord, what is this? All of this walking about, trying, smiling, bowing, joking? This sitting-down-at-table, pressing-of-shirts, tying-of-ties, shining-of-shoes, planning-of-trips, singing-of-songs-in-the-bath?

When he is to be left out here?

Is a person to nod, dance, reason, walk, discuss?

As before?

A parade passes. He can’t rise and join. Am I to run after it, take my place, lift knees high, wave a flag, blow a horn?

Was he dear or not?

Then let me be happy no more.

(hans vollman)”

Just a beautiful passage, Bevins experiencing Vollman’s thoughts:

“As soon as tomorrow, if I can only recover, I will have her. I will sell the shop. We will travel. In many new cities, I will see her in dresses of many colors. Which will drop to many floors. Friends already, we will become much more: will work, every day, to ‘expand the frontiers of our happiness’ (as she once so beautifully put it). And—there may be children yet: I am not so old, only forty-six, and she is in the prime of her—

(roger bevins iii)”

A description of positive Judgement passed:

“A tremendous set of diamond doors at the far end of the hall flew open, revealing an even vaster hall.

I perceived, there within, a tent of purest white silk (although to describe it thus is to defame it—this was no earthly silk, but a higher, more perfect variety, of which our silk is a laughable imitation), within which a great feast was about to unfold, and on a raised dais sat our host, a magnificent king, and next to the king’s place sat an empty chair (a grand chair, upholstered with gold, if gold were spun of light and each particle of that light exuded joy and the sound of joy), and that chair was intended, I understood, for our red-bearded friend.

Christ was that king within; Christ was also (I now saw) that seated prince/emissary at the table, in disguise, or secondary emanation.

I cannot explain it.

The red-bearded man passed through the diamond doors in his characteristic rolling gait and the doors closed behind him.

Never in my nearly eighty years of life on earth had I experienced a greater or more bitter contrast between happiness (the happiness I felt even glimpsing that exalted tent, from such a great distance) and sadness (I was not within the tent, and even a few seconds without seemed a dreadful eternity).”

A beautiful collective remembering of lovely moments in life:

“We now recalled—

(hans vollman)

All instantaneously recollected—

(the reverend everly thomas)

Suddenly, I remembered: the showing up at church, the sending of flowers, the baking of cakes to be brought over by Teddie, the arm around the shoulder, the donning of black, the waiting at the hospital for hours.

(roger bevins iii)”

More Bevins, more beautiful observations:

“And there was nothing left for me to do, but go.

Though the things of the world were strong with me still.

Such as, for example: a gaggle of children trudging through a side-blown December flurry; a friendly match-share beneath some collision-tilted streetlight; a frozen clock, bird-visited within its high tower; cold water from a tin jug; toweling off one’s clinging shirt post-June rain.

Pearls, rags, buttons, rug-tuft, beer-froth.

Someone’s kind wishes for you; someone remembering to write; someone noticing that you are not at all at ease.

A bloody roast death-red on a platter; a hedgetop under-hand as you flee late to some chalk-and-woodfire-smelling schoolhouse.

Geese above, clover below, the sound of one’s own breath when winded.

The way a moistness in the eye will blur a field of stars; the sore place on the shoulder a resting toboggan makes; writing one’s beloved’s name upon a frosted window with a gloved finger.

Tying a shoe; tying a knot on a package; a mouth on yours; a hand on yours; the ending of the day; the beginning of the day; the feeling that there will always be a day ahead.

Goodbye, I must now say goodbye to all of it.’

Bevins, on naming things and loving them and losing them:

“None of it was real; nothing was real.

Everything was real; inconceivably real, infinitely dear.

These and all things started as nothing, latent within a vast energy-broth, but then we named them, and loved them, and, in this way, brought them forth.

And now we must lose them.

I send this out to you, dear friends, before I go, in this instantaneous thought-burst, from a place where time slows and then stops and we may live forever in a single instant.

Goodbye goodbye good—

(roger bevins iii)”

0 notes

Text

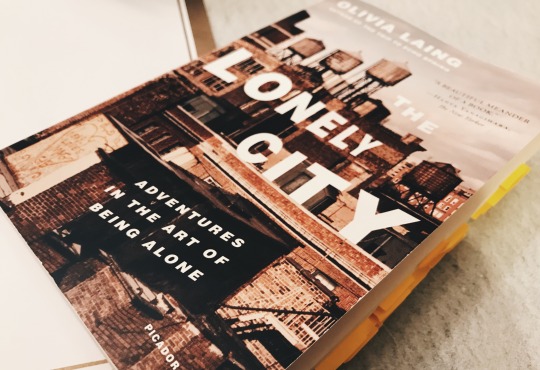

The Lonely City: Thoughts

The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone (Olivia Laing)

I had been wanting to read this book for two years, without really knowing what it was about. I devoured anything and everything dealing with loneliness—I longed to take in other people's experiences, to read declarations and stories and tell-alls that would help me feel like I wasn't alone in my aloneness. Thus began the long and boring saga in which I half-heartedly tried to reserve the book through Stanford's library system every six months or so, which for some reason never came through.

Now, years later and in a state of general contentment in terms of my relationships with other people, I feel much less compelled to read things about loneliness (this is interesting and Laing brings this up in her book—the amnesia of emotion that comes with getting less lonely, and even the active aversion and rejection of hearing about other people's loneliness after you yourself have left it behind). Still, I'm broadly interested in all stories about people's emotions, so after spotting this book in the Chicago IDEO office, I decided to pick it up and finally give it a read.

And this book was so much more than what I had expected—The Lonely City isn't just an essay about loneliness, or even a collection of memories and observations about loneliness. It opened my eyes to ideas and topics I had never thought about—the ways that machines can serve as both lubricant and barrier to the outside world, the underlying sentiment and fear behind the reactions to the AIDS epidemic, the role that physical contact plays in a person's development and connection to those around them. I learned a lot about the four artists that Laing write about—and she does an almost inconceivably thorough research job, describing how she digs through archives and even boxes of physical artifacts from the artists' lives. In particular, I feel much... closer (?)... sympathetic (?) to Andy Warhol and David Wojnarowicz—not because I feel similar to them, or had an upbringing at all comparable to theirs, but because their work and their words helped me understand them in a new light (the notes below add some detail to the parts that particularly spoke to me).

The language of The Lonely City itself is quite flowery, and sometimes I think Laing makes statements that are a little too dramatic (and maybe not as supported by the exposition as I would want). But overall, her research and the sprinkling of her own stories and memories throughout the book make for an engrossing read—she brings the artists and their work to life.

Here are a few excerpts that I wanted to save:

On being lonely in cities:

“Imagine standing by a window at night, on the sixth or seventeenth or forty-third floor of a building. The city reveals itself as a set of cells, a hundred thousand windows, some darkened and some flooded with green or white or golden light. Inside, strangers swim to and fro, attending to the business of their private hours. You can see them, but you can’t reach them, and so this commonplace urban phenomenon, available in any city of the world on any night, conveys to even the most social a tremor of loneliness, its uneasy combination of separation and exposure.”

On the unique mental map of a city each inhabitant creates:

“Loneliness, I began to realise, was a populated place: a city in itself. And when one inhabits a city, even a city as rigorously and logically constructed as Manhattan, one starts by getting lost. Over time, you begin to develop a mental map, a collection of favoured destinations and preferred routes: a labyrinth no other person could ever precisely duplicate or reproduce.”

On being preoccupied and not responding to someone else’s loneliness:

“When I read those lines, I remembered sitting, years back, outside a train station in the south of England, waiting for my father. It was a sunny day, and I had a book I was enjoying. After a while, an elderly man sat down next to me and tried repeatedly to strike up conversation. I didn’t want to talk and after a brief exchange of pleasantries I began to respond more tersely until eventually, still smiling, he got up and wandered away. I’ve never stopped feeling ashamed about my unkindness, and nor have I ever forgotten how it felt to have the force field of his loneliness pressed up against me: an overwhelming, unmeetable need for attention and affection, to be heard and touched and seen.”

On how hard it is to remember what being lonely feels like when you aren’t lonely anymore:

“He felt that in addition to it being unnerving in its own right—he writes of it as something that ‘possessed’ people, that is ‘peculiarly insistent’; ‘an almost eerie affliction of the spirits’—loneliness inhibits empathy because it induces in its wake a kind of self-protective amnesia, so that when a person is no longer lonely they struggle to remember what the condition is like.

‘If they had earlier been lonely, they now have no access to the self that experienced the loneliness; furthermore, they very likely prefer that things remain that way. In consequence they are likely to respond to those who are currently lonely with absence of understanding and perhaps irritation.’”

On large and small intimacies:

“If you are not being touched at all, then speech is the closest contact it is possible to have with another human being. Almost all city-dwellers are daily participants in a complex part-song of voices, sometimes performing the aria but more often the chorus, the call and response, the passing back and forth of verbal small change with near and total strangers. The irony is that when you are engaged in larger and more satisfactory intimacies, these quotidian exchanges go off smoothly, almost unnoticed, unperceived. It is only when there is a paucity of deeper and more personal connection that they develop a disproportionate importance, and with it a disproportionate risk.”

Andy Warhol on followings:

“‘At the times in my life when I was feeling the most gregarious and looking for bosom friendships, I couldn’t find any takers so that exactly when I was alone was when I felt the most like not being alone. The moment I decided I’d rather be alone and not have anyone telling me their problems, everybody I’d never even seen before in my life started running after me... As soon as I became a longer in my own mind, that’s when I got what you might call a “following”’”

Andy Warhol on his tape recorder:

“‘I didn’t get married until 1964 when I got my first tape recorder. My wife. My tape recorder and I have been married for ten years now. When I say “we,” I mean my tape recorder and me. A lot of people don’t understand that... The acquisition of my tape recorder really finished whatever emotional life I might have had, but I was glad to see it go. Nothing was ever a problem again, because a problem just meant a good tape and when a problem transforms itself into a good tape it’s not a problem any more.’”

On the balance between being private and exposing too much:

“Intimacy can’t exist if the participants aren’t willing to make themselves known, to be revealed. But gauging the levels is tricky. Either you don’t communicate enough and remain concealed from other people, or you risk rejection by exposing too much altogether: the minor and major hurts, the tedious obsessions, the abscesses and cataracts of need and shame and longing. My own decision had been to clam up, though sometimes I longed to grab someone’s arm and blurt the whole thing out, to pull an Ondine, to open everything for inspection.”

On society’s role in perpetuating isolation:

“People pick up on these perceived markers of abnormality. They sidestep the street mutterer and shun the former criminal, isolating them if not submitting them to actual violence. What I am trying to say is that the vicious circle by which loneliness proceeds does not happen in isolation, but rather as an interplay between the individual and the society in which they are embedded, a process perhaps worsened if they are already a sharp critic of that society’s inequities.”

On the “smearing” that comes with large crowds and events:

“I thought it would be cheering to stand in a crowd, but it wasn’t, not really. Looking at my photos from that night I think that what I was in search of was a sensation of smear, of the collapsing boundaries that come with festivity or intoxication. All my pictures are blurred; they all show a whirl of bright objects colliding in space.”

On masks and the burden of having to look appealing:

“I bitterly regretted not having bought a mask in Party City: a cat face or Spider-Man. I wanted to be anonymous, to pass through the city unseen; not invisible exactly, but concealed, my pained, anxious, all too declarative face hidden from view, relieved from the burden of needing to look unconcerned, or worse, appealing.”

Laing puts it the best, on the “non-consensual beauty pageant of femininity”: