#steven pressfield

Quote

The opposite of fear is love - love of the challenge, love of the work, the pure joyous passion to take a shot at our dream and see if we can pull it off.”

Steven Pressfield, Do the Work

#quotes#steven pressfield#do the work#love over fear#inspiration#passion#dream#challenges#for the heart#important

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We're never alone. As soon as we step outside the campfire glow, our Muse lights on our shoulder like a butterfly. The act of courage calls for infallibly that deeper part of ourselves that supports and sustains us.

- Steven Pressfield

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

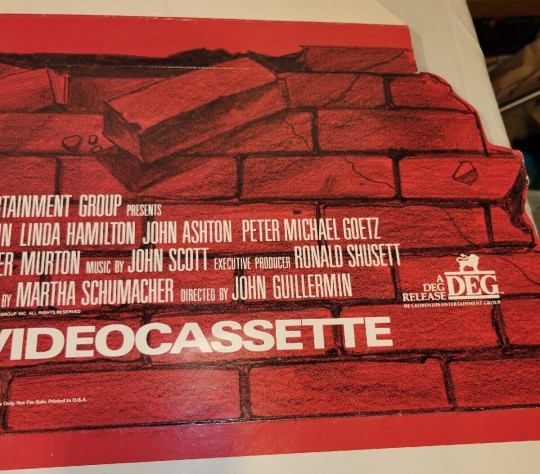

#King Kong Lives#John Guillermin#Charles McCracken#Ronald Shusett#Steven Pressfield#Merian C. Cooper#Edgar Wallace#80s

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

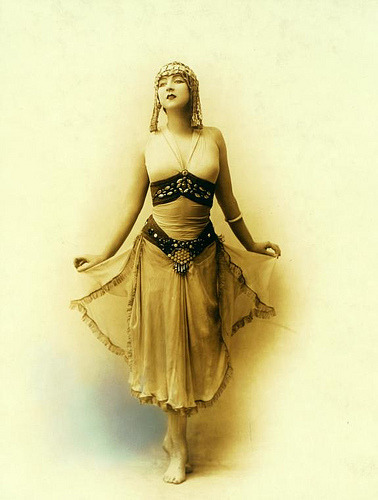

Ruth St. Denis, ca. 1912 :: Ruth St. Denis in costume for dance created and performed at one performance only in honor of Dr. Anna Shaw at the McAlpin Hotel.

[From the New York Public Library]

* * * * *

It is one thing to study war and another to live the warrior's life.

— Telamon of Arcadia, mercenary of the fifth century B.C.

A professional schools herself to stand apart from her performance, even as she gives herself to it heart and soul. The Bhagavad-Gita tells us we have a right only to our labor, not to the fruits of our labor. All the warrior can give is his life; all the athlete can do is leave everything on the field. The professional loves her work. She is invested in it wholeheartedly. But she does not forget that the work is not her. Her artistic self contains many works and many performances. Already the next is percolating inside her. The next will be better, and the one after that better still.

The professional self-validates. She is tough-minded. In the face of indifference or adulation, she assesses her stuff coldly and objectively. Where it fell short, she'll improve it. Where it triumphed, she'll make it better still. She'll work harder. She'll be back tomorrow.

The War of Art by Steven Pressfield

[via "alive on all channels"]

#dancers#costume#NYPL#Ruth St. Denis#performance#The War of Art#Steven Pressfield#Telamon of Arcadia#alive on all channels#warrior life#quotes#discipline#practice

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"This man has conquered the world! What have you done?"

The philosopher replied without an instant's hesitation, "I have conquered the need to conquer the world.”

Steven Pressfield

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

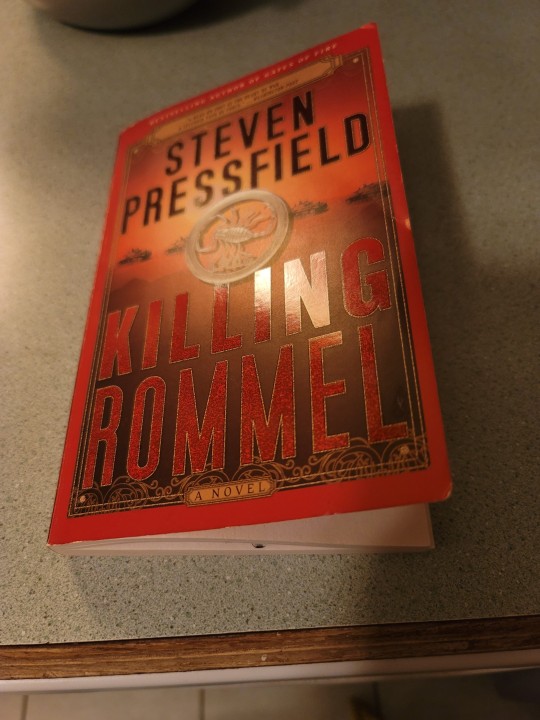

I'm rereading Killing Rommel for the second time this year. I have a problem.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

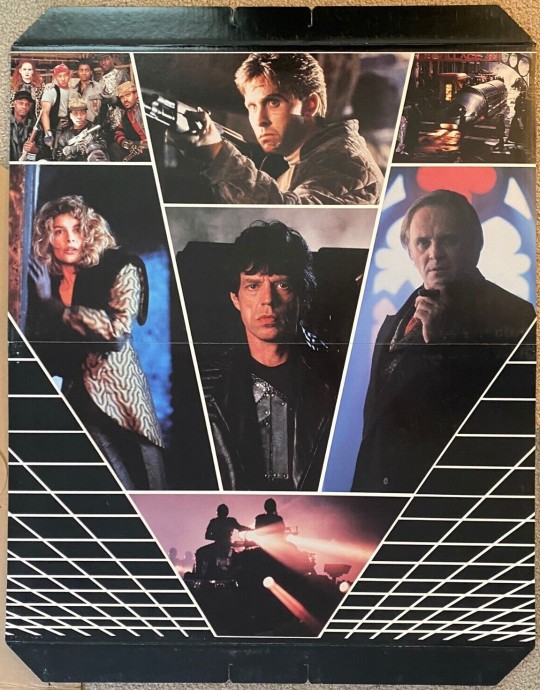

#Freejack#Emilio Estevez#Mick Jagger#Rene Russo#Anthony Hopkins#Geoff Murphy#Robert Sheckley#Steven Pressfield#Ronald Shusett#Dan Gilroy#90s

20 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Self-doubt can be an ally. This is because it serves as an indicator of aspiration. It reflects love, love of something we dream of doing, and desire, desire to do it. If you find yourself asking yourself (and your friends), 'Am I really a writer? Am I really an artist?' chances are you are. The counterfeit innovator is wildly self-confident. The real one is scared to death.

Steven Pressfield, The War of Art, p. 39

#quotes#steven pressfield#the war of art#self-doubt#aspiration#ambition#love#desire#writing#creativity#fear#artists#imposter syndrome

25 notes

·

View notes

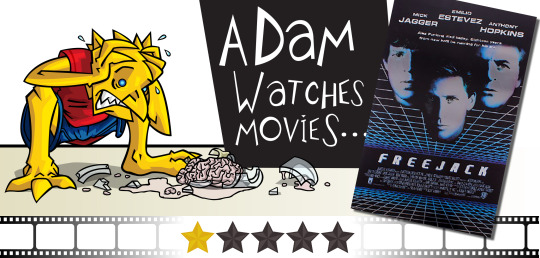

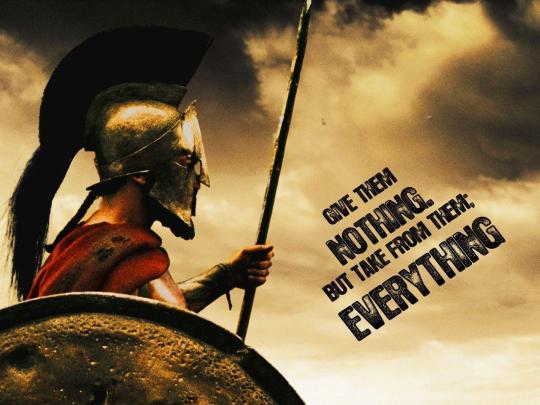

Photo

“Spartans were the first to show us how to live, and how to die.” ― Julius Caesar

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE MAGIC OF MAKING A START

Concerning all acts of initiative (and creation) there is one elementary truth, the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would not otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one's favour all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance which no man would have dreamed would come his way. I have learned a deep respect for one of Goethe's couplets: "Whatever you can do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, magic, and power in it. Begin it now.

Steven Pressfield, The War of Art

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#the war of art#steven pressfield#quotes#he gets a pass because he really was a marine#but the war epigraphs are a bit much for normal writers lmao#villains

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Freejack (1992)

While I didn't enjoy this film, that doesn't mean you won't. No matter what I say, the people involved in this project did it: they actually made a movie. That's something to be applauded. With that established...

I was under the impression that Freejack has some sort of cult following and that a number of people consider it a film that’s “so bad it’s good”. I need to reconsider my sources. Dull, contrived and predictable, I won’t remember a thing about this movie within a week.

Just as Alex Furlong (Emilio Estevez) is about to crashnhis car, he is stolen from the year 1991 and transported to 2009 (!). In this futuristic dystopia, people from the past who were about to die - and therefore wouldn't be missed - have their minds wiped and replaced with that of clients who pay top dollars for a new body. Now on the run from mercenary Victor Vacendak (Mick Jagger), Alex searches for his girlfriend Julie (Rene Russo), but can he trust a woman who hasn’t seen him in 18 years?

You might spot a major hole in this premise but to give Freejack credit, it explains why the 1% of 2009 need to steal bodies from the past. To me, this only makes the movie worse. If there were holes in the future tech or logic of this 1992 action thriller (I think that’s what it’s supposed to be), it might stand out. Currently, the only noteworthy aspect of Freejack is the cast. Why Mick Jagger as the honor-bound mercenary? Why Anthony Hopkins as Julie’s boss (who definitely isn’t up to something)? I guess you can have fun pointing out the art direction’s obsession with jacks (not the car kind, but the metal thingies you grab after bouncing a rubber ball on the ground). Does that sound worth the time you’ll spend bored?

The film is full of missed opportunities. Alex is an ace Formula One driver. He's only goes on a single high-speed car chase. The idea of being displaced in time also doesn’t get mined as much as it should. There is merit to the concept if you put some thought into the plot. It seems neither director Geoff Murphy nor writers Steven Pressfield, Ronal Shusett or Dan Gilroy had any ambition to do so.

There’s little else to say about Freejack. It’s an unremarkable picture. The most interesting thing about it are it’s then-futuristic 2009 setting, trippy & dated special effects and seemingly random cast in a lame film. (February 9, 2018)

#Freejack#movies#films#movie reviews#film reviews#Geoff Murphy#Steven Pressfield#Ronal Shusett#Dan Gilroy#Emilio Estevez#Mick Jagger#Rene Russo#Anthony Hopkins#Jonathan Banks#David Johansen#1992 movies#1992 film

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

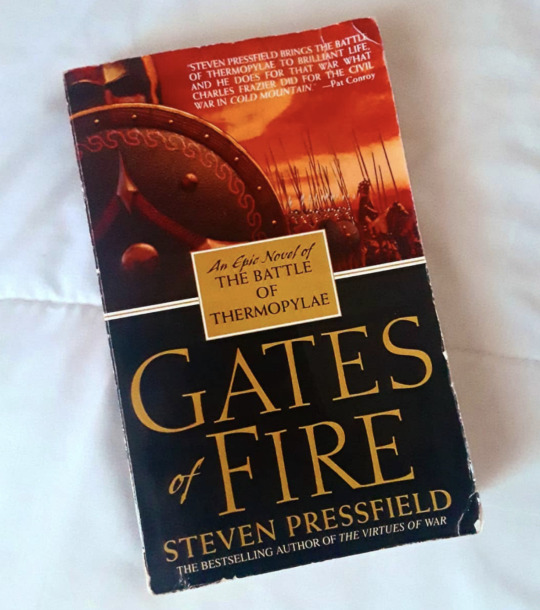

Treat Your S(h)elf: Gates of Fire by Steven Pressfield (1998)

At Thermopylae, a rocky mountain pass in northern Greece, the feared and admired Spartan soldiers stood three hundred strong. Theirs was a suicide mission, to hold the pass against the invading millions of the mighty Persian army.

Day after bloody day they withstood the terrible onslaught, buying time for the Greeks to rally their forces. Born into a cult of spiritual courage, physical endurance, and unmatched battle skill, the Spartans would be remembered for the greatest military stand in history–one that would not end until the rocks were awash with blood, leaving only one gravely injured Spartan squire to tell the tale….

- Steven Pressfield, Gates of Fire (1998)

This is one of my favourite books on war I’ve ever read. I took my dog-eared copy with me last year when I went with ex-military veterans friends to climb Olympus and hike around Greece. One of the places we stopped was Thermopylae - where you can still bathe in the hot springs as the ancient Spartans and Athenians did before their monumental battle with the Persians. The very recent death of the last king of Greece, King Constantine II of the Hellenes, made me think of my trip to Greece last year and of one of the books I read on that trip. I thought I might share some of my rambling thoughts I had written down at the time, and also since then, about the retelling of one historical turning point in our western civilisation that has now entered into myth.

In 1998 was the year Frank Miller’s iconic comic graphic novel 300 about the the Battle of Thermopylae – where a tiny Greek force led by 300 Spartans held out for three days against an immense Persian invasion in 480BC - was published to great critical acclaim. Zack Snyder highly stylised slick film version of Miller’s 300 defied audience and studio expectations when it stormed the box office with Spartan-like ferocity back in 2007. Its mix of ancient history, comic-book iconography and sound-bite dialogue immediately found its way into the verbal and visual lexicon of contemporary pop culture; but things could have been very different. In 1998 Miller’s publication overshadowed the publication of Steven Pressfield’s more conventional historical novel, Gates of Fire, took its name from the eponymous battlefield, Thermopylae (referred to in 300 as ‘the hot gates’).

Pressfield, an ex-Marine soldier, had worked as a screenwriter creating disposable action-movie scripts for the likes of Steven Seagal and Dolph Lundgren in the late 1980s and early 1990s before writing his first novel, The Legend of Bagger Vance, which was adapted into the Will Smith film of the same name. It too won critical acclaim and was a huge best seller. George Clooney’s film production company bought the rights and David Self (screenwriter of 13 Days and Road to Perdition) was brought in to adapt it. Bruce Willis was dying to be in it and iconic director Michael Mann signed on the direct it. Instead the film went into development hell before Snyder’s film stole a march on Mann’s version to come out first in 2007.

As a Classicist and ex-veteran I found Both Miller’s comic graphic novel and Snyder’s film a severe guilty pleasure. But I have to say I found reading Steven Pressfield’s brilliant novel deeply satisfying on many more levels.

The book I remember well as an American special forces chap I knew out in Afghanistan gave it to me to read because I was complaining I was fast running out of things to read between missions. I loved it.

Like a good officer I passed the book along to others in my corps - rank and file - and within a month or two it had been passed around a fair bit. It led to endless arguments about the Greeks and the Western way of war in and out of the cockpit with my brother/sister aviators and crew as well other officers and the men.

For the soldiers on the ground the book felt more visceral. As a fellow brother British infantry officer said the depictions of phalanx warfare raised his blood pressure at how well he and his men could relate. I never felt more Spartan than I did I sitting on my arse baking in the sun of Afghan red dust mornings. We all related to this story one way or another - the sand, sweat, blood, feelings of combat, and thoughts of mortality.

Most book reviewers loved the book. “Does for (Thermopylae) what Charles Frazier did for the Civil War in Cold Mountain’, enthused author Pat Conroy. The New York Times praised the book’s ‘feel of authenticity from beginning to end.’ Author Nelson DeMille admired the ‘mastery, authority and psychological insight.’ Sarah Broadhurst, in The Bookseller, particularly wanted to recommend the book to women: “ Although it has a male feel to it, it will appeal to both sexes, as my two readers and I can testify. In fact, it is a great example of the rebirth of the historical novel, which I am sure is on its way.” Where people quibbled, it was usually about the violence of some of the descriptions, or on small errors of fact. The Times called it ‘a story of blood, biffing and bonking, thigh deep in blood, terror-piss and entrails’ but acknowledged that ‘their heroism still makes the hairs at the back of the neck bristle’. The Times Literary Supplement sniped at Pressfield for confusing two different Greek cities called Argos, and for what it called ‘phallocentric discourse’, but also called the book ‘a monument to the important twentieth-century art of pace.’

The novel stands out in the way it makes everything come alive from the soldiers' training, the scenes of actual battle, and most particularly the scenes after or between battles. The discussions of fear, and of how officers and soldiers should behave are particularly poignant and also felt very real to those of us who have experienced war first hand. What I found pleasantly surprising was how well written it was with its very strong portrayals of women as secondary characters. With nearly all military books women are often relegated to the background but here I found some of the strongest depictions of women in this genre. The women don't fight in the battles, yet are courageous and compassionate, intelligent and influential.

Many readers will be familiar with the broad strokes of the story of the battle. But it’s worth recapping here for those that don’t. In 480 BC, King Xerxes lead a Persian army of between one and two million into Greece. The Spartan King Leonidas lead 300 Knights and some 700 Thespaian allies to the narrow pass at Thermopylae, in order to hold the Persians back as long as possible. They proceeded to hold the pass for 7 days. These 300 Spartans died to a man defending the pass against a force of over a million and the epitaph provided to them by the poet Simonides, "Go tell the Spartans, stranger passing by, that here obedient to their laws we lie", is perhaps the most famous in history. Their example rallied and inspired all of Greece and eventually the Persians were defeated in the naval battle at Salamis and on land at Plataea.

The story is told from the point of view of its narrator Xeones of Astakos, a helot, a slave of the Spartans, and has his own conflicted feelings about Spartan society. He is taken, wounded, before Xerxes, and asked to explain “who were these foemen, who had taken with them to the house of the dead ten or, as some reports said, as many as twenty for every one of their own fallen?” In Xeones’ own words, therefore, we get the story of his life; from when his own city is destroyed, to when he comes to Sparta as a slave, to the time when he finally comes to stand beside the Spartiate in the fateful battle. As the sole survivor among the Spartans, Xerxes wishes Xeones to tell his story to the Persian court historian Gobartes. Xeones starts with the tale of how he came to Sparta. As a youth, his village of Astakos is destroyed and his family slaughtered, but he and the cousin he loves, Diomache, escape. As they wander the countryside, Diomache is raped by soldiers and Xeones is crucified after stealing a chicken, although Diomache saves him from death. Thrown into despair, because his hands are so damaged that he can never wield a sword, Xeones heads off by himself to die. But he experiences a visitation from the Archer god Apollo Far Striker and realizes he can still wield a bow. When Diomache, who is also distraught after being violated by the soldiers, takes off, Xeones heads to Sparta where he hopes to join the army.

The middle section of the book, which is at a much slower pace, deals with his life in Sparta and the training techniques used by the Spartans to create what was one of the most formidable fighting forces the world has ever seen. Eventually he becomes the squire of one of the 300 knights who are chosen for Thermopylae.

The final section, on the battle itself, depicts wholesale slaughter accompanied by acts of ineffable courage. It also relates two of the great lines of all time. When Xerxes offers to spare the Spartans lives if they will surrender their arms, Leonidas is reputed to have snarled, "come and get them." And upon being told that the Persians have so many bowmen that the cloud of arrows would blot out the sun, one of the Spartans says, "good, then we'll have our battle in the shade."

Pressfield being an ex-Marine grunt himself gives a very convincing grunt’s-eye-view of the battle and of Spartan society to create a fantastically blood pumping engaging tale. Pressfield sets himself the task of explaining Spartan culture to us in all its glory, humour, brutality and philosophy. To do so, he draws on his personal experience as a US infantryman, as well being strongly versed in Classics. The result is a fascinating tale, on one level a war story written with great pace and excitement, on another a ruminative tale of man’s capacity for honour, heroism, and self-sacrifice.

As a Classicist (since confirmed by Pressfield in many interviews) he makes excellent use of the ancient historical sources (such as they are). The most useful sources seem to be Herodotus first, his pages about the battle. Plutarch’s Lives of various Spartans — Lycurgus, Agesilaus, Lysander, etc - can be discerned strongly as the section of his Moralia called Sayings of the Spartans and Sayings of the Spartan Women. Xenophon of course was the best contemporaneous eyewitness to real Spartan society. Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, the Cyropaedia and even the Anabasis greatly help Pressfield pepper history with authentic detail. Diodorus’ version of the battle added the thought of the night raid (which The 300 Spartans also had) and Pressfield takes that from him. Pressfield has said that he didn’t consult recent archaeology, other than going to Sparta myself and checking out the ruins of Artemis, Orthia and so forth.

But still huge gaps remained. This is where Pressfield the ex-Marine and the well educated novelist come together. There was much detail that he needed to consciously to make up and make it sound plausible and even true. For instance, the concept of phobologia, the Science of Fear. That’s completely invented, yet Pressfield, as a Marine veteran, absolutely felt certain the Spartans, like every other warrior race, must have had something like that, a religious-philosophical doctrine of warfare understanding the principles of their culture, probably a sort of cult-like initiatory situation.

Pressfield in one interview admitted that the speech that Alexandros recites holding his shield — “This is my shield, I bear it before me into battle, etc.” — was a fictional invention based upon his own experience in the US Marine Corps, where Marines recite, “This is my rifle. There are many other like it, but this one is mine, etc.” Another huge fictional detail that he made central to the story was the prominence of the squire in hoplite battle. Again he based this on pure instinct and common sense. He thought the relationship must be much like that of a professional golfer to his caddie. Pressfield firms believes that the bonds formed between man and batman in the course of bloody warfare must have been intimate on a level second only to husband and wife, and maybe more intimate. The ancient sources make nothing of this, because they just passed it over as obvious, but I fully agree with Pressman. It’s an inspired insight. The fact that squires and armour bearers voluntarily stayed to die at Thermopylae says volumes. (Also a squire was the perfect fly-on-the-wall narrator, like Midshipman Byam in Mutiny on the Bounty.) Further I could not imagine that squires would stand idly by, watching their men fight. They must have served as auxiliaries, not only dashing in and out of the field evacuating the wounded, but getting in their blows as light infantrymen whenever they could. I suspect that, as prominent as Pressfield made their roles in Gates, if we could beam ourselves back and witness actual ancient battle, the part of the squire/auxiliary was even bigger than one might imagine.

The book then is not merely about the immortal stand at Thermopylae but delves into the Spartan lifestyle, how they achieved such military cohesion, how they viewed themselves and the world, what made them willing to march off to a suicide mission — it’s one thing to find oneself in such a situation, it’s quite another to jockey to be chosen for it, to know days ahead of time that this is it, you’re heading to your death and to do it unflinchingly. It’s about what binds men together in a group — what makes them willing to die for others. I think Dienekes’ thoughtful analysis of fear and how the opposite of fear isn’t bravery but love, tells it all. Love of a messmate, a family, a city.

Indeed as Pressfield shows the spartans would carry their shields on the left side of their body which allowed them to cover the blind spot of the warrior fighting next to them. Commanders would arrange it so that family members and friends were placed next to each other within the formation. The belief was that warriors would be less likely to abandon their comrades if they were fighting next to someone they deeply cared about. Love conquers fear.

Now the story isn’t perfect, there are some pacing issues when the plot seems to go extra slow, and there are time jumps that can feel a bit awkward. Some periods of our main protagonist’s life, that would be interesting, are just skipped.

In my opinion, the book balances fiction and facts quite nicely, not making the Spartans some over the top super heroes, like the movie “300” did.

The thing that I liked the most is the whole theme of the book: honour, the duty to your city and people, and the strength of the mind. The Spartans didn’t see war as a fun way of killing people, it was an inevitable fact of life. They didn’t kill fear, they learned to embrace it, keep it locked until the very last moment.

Now it’s a bit harder to judge characters in a book like this because some of them are based on real people and some of them are fictional. But what I will say is that these people feel real, grounded to the situation they are in.

I was very taken by the portrayal of Leonidas, the Spartan king who commanded at Thermopylae. One of the most stirring speeches in the book is addressed to Xerxes, the King of Persia, and contrasts Xerxes with Leonidas: "I will tell His Majesty what a king is. A king does not abide within his tent while his men bleed and die upon the field. A king does not dine while his men go hungry, nor sleep when they stand at watch upon the wall. A king does not command his men's loyalty through fear nor purchase it with gold; he earns their love by the sweat of his back and the pains he endures for their sake….”

I also appreciated the inclusion of the women of Sparta — no shirkers themselves. They would be the first ones out shaming the men into doing their duty for their city (and that’s what it was all about for these people — the survival of the city first) if that was what was needed. I have to say I shed a tear when Leonidas confessed his criteria for selection of the 300. So much is said about Spartan men but the women kicked ass in a time and place where women were almost never seen and certainly never heard from. The first female Olympic champion was a Spartan princess called Kynisca, in 392 BC. She was also the first woman to become a champion horse trainer when her horses and chariot competed and won in the Ancient Olympic Games. Twice.

Arete is in some ways the most powerful character in the book. She is very well written. She just popped forth, full-grown from the brow of Zeus. I liked her a lot. Whether or not Sparta was a “good” place for women I can’t say. Certainly it would be fascinating as hell to beam back there and see, for real, how they lived and what they were like. It seems likely Pressfield drew inspiration of Arete from Plutarch’s Sayings of the Spartan Women. These, if you’ve ever read them, are unbelievably hard-core. For example, here’s one: A messenger returns from a battle to inform a Spartan mother (Plutarch gives her name but I’ve forgotten it) that all five of her sons have just perished honourably fighting the enemy. She asks this only: “Were we victorious?” The courier replies yes. “Then I am happy,” says the mother and turns for home. Here’s another: A messenger returns from another battle to tell another mother that one of her sons has been killed, facing the enemy. “He is my son,” she says. Her other son, the messenger continues, is still alive but ran from the enemy. “He is not my son,” she replies. Pressfield doesn’t see Arete quite that hard-core but certainly someone tough as nails who imbibed the Spartan mythos even more than the men and lived it. Pressfield admits in one of his interviews that this was all instinct, he could be wrong, but itt just was what felt right to him.

Before I had gone through Sandhurst after university I didn’t really condone crude language or lewd humour but it’s one of the ways that my stint in the army and especially out on a battlefield deployment changed me a little. I confess that I loved the sometimes crude humour - they’re soldiers in a time of war and you do or say whatever will get you through. Battle (especially foxhole) humour has a dark gallows feel and it’s entirely acceptable and authentic - just ask any veteran of any war. The battle descriptions are graphic - very graphic but not much worse than what’s in the Iliad. And we are talking about a battle in which thousands died by sword, spear, arrow and other various messy methods.

I also enjoyed how the book has a pleasing prose aesthetic that imitates the style of Homer. For the non-Classicist it may take a little bit of getting used to and slow down their reading but it sounds melodious to the ear.

Overall Pressman gives us a pulsating story in which the characters are not either super evil villains that cartoonishly want to “take over the world” or superheroes that can’t make mistakes. The author doesn’t take a side in this story, war is war, and people are people. They make mistakes, get angry or jealous, they do bad things in the name of good and vice versa. The book is not about good and evil, it’s about how different people and cultures understand the order, stability, good and even our minds and dreams. The enemies here aren’t some sort of Oriental magic freaks from far away lands, they are just men made in flesh and blood. Sure wanting to control more land or have more people serving them, but that’s everyone I know in the history of rise and fall of civilisations.

Was the Spartan defence of the Hot Gates worth it?

Clearly, yes. Cultures, if not civilisations, are nearly always rubbing up against each other and even clashing where they can’t bridge differences. I think Pressfield has it right when he said, “What the defence meant to me was this: its significance was metaphorical rather than literal. We are all in a battle that will end with our deaths and, like the Spartans at Thermopylae, we know it. The question is how do we deal with it. They answered by being true to their calling, to their brothers and sisters, and to their ideals. Early in the book there’s a passage where the Persian historian is narrating; he’s speaking of King Xerxes and his interest in the fallen Spartans. Xerxes says of them: “He knew they feared death, as all men. By what philosophy did their minds embrace it?”

In two of my favourite passages, Pressfield has his protagonist explain why sacrifice is so beautiful to the Greeks (or to anyone who has honour), "In one way only have the gods permitted mortals to surpass them. Man may give that which the gods cannot, all he possesses, his life”. This is a very profoundly moving insight.

Pressfield goes further and tries to answer a much deeper question as to why men fight and perhaps this is where it’s the ex-Marine and not the novelist in Pressfield who is talking, "Forget country. Forget king. Forget wife and children and freedom. Forget every concept, however noble, that you imagine you fight for here today. Act for this alone: for the man who stands at your shoulder."

Amen to that.

At the end of the book, I would have probably stranded there fighting side by side with them against the Persians. Because at that point, they were my friends, comrades, and heroes. It was when I put the book down that I realised that I already had the humble privilege of serving with my fellow brother and sister officers and soldiers of whom all were comrades, many were friends, and a few were unspoken heroes.

Does the battle of Thermopylae provide any lessons to us?

That is harder to discern because it depends on what values we already hold dear. Sparta was a small, compact, basically tribal society where every citizen (forgetting about the helots for the time being) was vitally needed and where warfare was hand-to-hand and absolutely communal, with your own brothers, uncles, father and friends fighting beside you, so if you acted the coward, there was no hiding it. The modern world of anonymity, mass culture, commercialism, shamelessness, indulgence of sensual desires, worship of money couldn’t be farther. The Spartan society is like a culture from the moon.

On an individual and interior basis, I think, can we take lessons that might help us. Self-discipline, loyalty, grit, hard work, perseverance, honour, humility, respect, and compassion.

On a societal level Spartans were not selfish and didn’t worship the cult of individualism as we do today. It was all about the group. In our age when civil strife, economic hardship, and effects of a unrelenting pandemic erode our trust in our political and civil institutions and set neighbour against neighbour because of the political or religious beliefs they might hold, the only thing we have left to fall back on is just our individual selves. It’s every man for himself. The Spartans would balk at such selfish individualism. The strength (and ultimately the effectiveness) of the Spartan phalanx was encapsulated in the “next man up” approach. If a warrior was injured or killed on the outer edge of the formation, the next man behind them would step up and take their place. The integrity of the group’s formation was protected at all costs, because without the strength of the phalanx to protect them, each man on had little chance of surviving the battle on his own. In a real sense, they had each other’s backs. They had the cohesion of a collective spirit. They were in it for each other together.

It’s not a bad thing in this day and age to be a little bit “spartan,” don’t you think?

#treat your s(h)elf#book#review#book review#reading#gates of fire#steven pressfield#sparta#thermopylae#persia#leonidas#xerxes#society#culture#antiquity#classical#greece#war#warfare#special forces#british army#US marines#battle#soldiers#arete#women#afghanistan#civilisation#TYS

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

»Danger is the greatest when the finish line is in sight. It is the point, Resistance knows we’re about to beat it. It hits the panic button. It marshals one last assault and slams us with everything it’s got. […] Be wary at the end.«

~ Steven Pressfield - The War if Art ~ Resistance is most powerful at the finish line

#steven pressfield#th war of art#resistance is most powerful at the finish line#coffee and books#book quotes#need the reminder#on the finish line writing my newest book#it fights me with teeth and claws#boat writes a book#again#writers on tumblr#german writing

1 note

·

View note

Text

#146 | The pro without success yet

(image from here)

After various odd jobs for over a decade, Steven Pressfield got his professional writing job for a movie called King Kong Lives. He and his partner were confident the movie would be a hit when they finished. They invited everyone they knew to the premiere and rented next door for overflow in case too many people showed up.

But barely anyone did. The magazine Variety wrote a…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The part we create from can't be touched by anything our parents did, or society did. That part is unsullied, uncorrupted, soundproof, waterproof, and bulletproof.

– Steven Pressfield, The War of Art

0 notes