Text

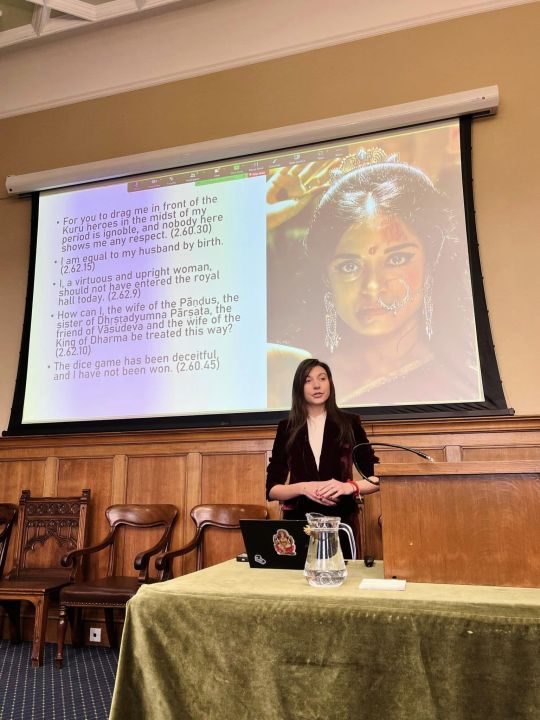

a joy to present my PhD work at the School of Divinity [Edinburgh] yesterday on my first research panel 😊 i talked about the gendered politics inscribed in the body of Draupadī, the Mahābhārata's heroine. i argued that it is significant that a text such as the Mahābhārata, which holds so much religious, cultural and spiritual weight, includes the story of a sexually assaulted woman, and, moreover, one of divine origin, because it offers women subjected to gendered violence the opportunity to unearth psychological comfort in Draupadī's story, and the opportunity to shed shame and fears of impurity rooted in varied internalisations of social or religious messages. through the prism of shared experience, the trauma is voiced and processed, which percolates in the social stratum, where, by claiming and reimagining Draupadī's symbol, women ask for and enact socio-political change. i am exploring this movement in my thesis. ❤️🔥

astounding to listen to & learn from the presentations of the colleagues who shared the panel with me, and to engage with the work differently during the q&a portion; openings to approach the work differently, freshly, in ways i wouldn't be prone to without external stimulus.

thank you @ishitahp for the photos & video! 🫶

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

honoured and very excited to share that i will be presenting the progress i have made with my research at Edinburgh University's School of Divinity, at a panel organised by EDI tomorrow, on the 29th of february! my presentation is entitled "The Gendered Politics Inscribed in the Body of the Mahābhārata's Draupadī". ❤️🔥 this will be my first research panel! 😊

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

on writing as an act of transcendence

the beautiful image is a painting of Sarasvatī that belongs to a set of sixty which chronologically depict a tale told in the Mahābhārata (as well as in the Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa and in the Śrīmad Devībhāgavata), that of King Hariścandra. this painting is one of two beginning the set, and it depicts the invocation of Sarasvatī, the Goddess of knowledge, speech and poetry, who is invoked as the flow of (and to flow the) words and wisdom of the telling. Gaṇeśa is invoked, as well.

in a seminar i recently went to, we discussed sacred texts, and the invocation of Gods & Goddesses in their openings - the muse in the Illiad, the deities in the Sanskrit texts etc. it made me reflect on writing as an inherently transcendental act. as in, it is not you who writes (or creates etc). it is being written through you, and it is therefore futile to take ownership for it.

as a 'writer', i oftentimes read my work and feel as if it was written by someone else. of course, my biases seep in (in editing, especially), but if i fully connect, the experience is that of it being written through me, and not by me.

i understand the invocation of the muses and Goddesses to reflect, in part, this understanding: that the act of creation subsumes and transcends the self or ego, even if only momentarily. that in creating, we tap into and open pathways within that we usually do not access customarily, when we are so entrenched in our sense of self that the energy can only flow in one way (that of sustaining our identity and the patterns which construct it). in creating, the energy can be freed to flow in new or in more ways. this is how i understand the surrendering to the muse or to one's art that is so lauded by poets. 🦢

#mahabharatam#mahabharata#mahabharat#writing#ganesha#saraswati#sarasvati#goddess#muse#devi#writer#poetry#poem#poet#sanskrit#hariscandra#indian art#hindu art#hinduism#hindu#hindu mythology#religion#itihasa#sanatandharma

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Draupadī by Yarlagadda Prasad! due to its highly erotic themes, the book caused outrage when it came out (and still continues to cause rifts to an extent). Dr. Prasad's expressed intention for this book is to explore one particular lore related to Draupadī, which is that her incarnation and marriage to five men were a boon of Śiva gifted to her to satiate her erotic desires, which she couldn't satiate in a prior life.

while i personally don't resonate with this lore (not out of moralistic sensibilities, but because i prefer to view the epic from the standpoint of cosmology), i admire Dr. Prasad's intention and appreciate the bold exploration of the Mahābhārata's eroticism (which exists in the Sanskrit epic as well, although not very explicitly).

in recent years, there has been a new literary opening to the erotic in Mbh retellings, and i personally would enjoy seeing more of it. for me, there is no need for puritanism when approaching such a great & all-encompassing epic.

#mahabharata#mahabharat#draupadi#panchali#sanskrit#itihasa#shiva#erotic#eroticism#mahabharatam#hinduism#hindu literature#yarlagadda lakshmi prasad#yajnaseni

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

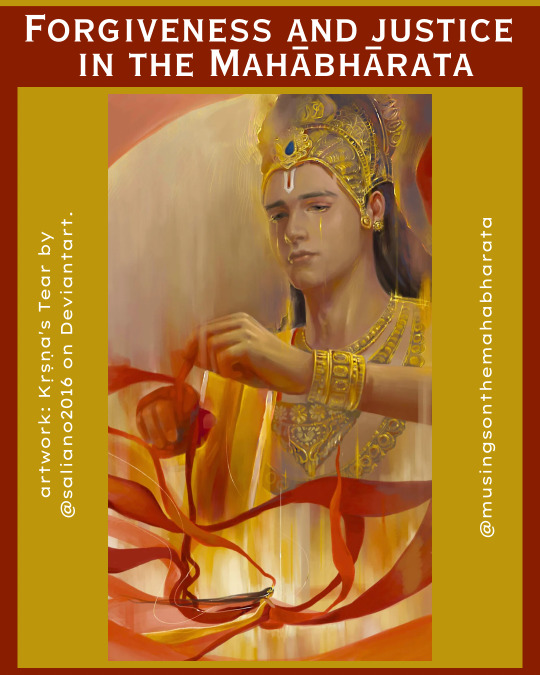

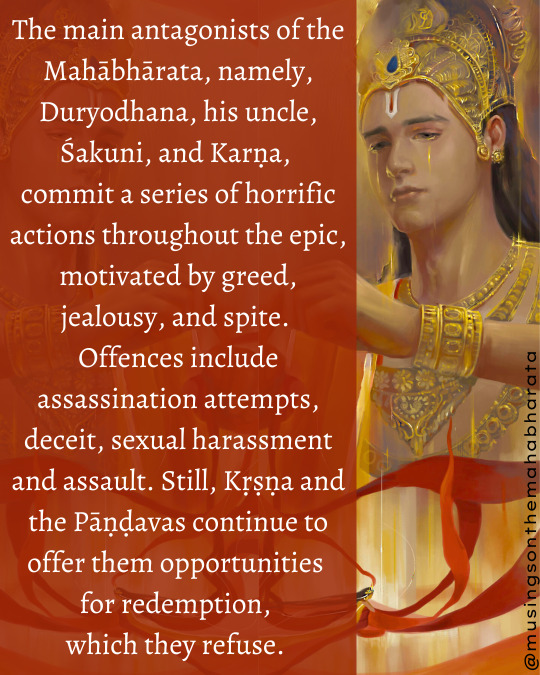

Forgiveness and Justice in the Mahābhārata

The main antagonists of the Mahābhārata, namely, Duryodhana, his uncle, Śakuni, and Karṇa (yes, if antagonists are to be named, Karṇa is one per the Critical Edition and per Kṛṣṇa’s comments) commit a series of horrific actions throughout the epic, motivated by greed, jealousy, and spite. Offences include assassination attempts, deceit, sexual harassment and assault. Still, what I love is that Kṛṣṇa and the Pāṇḍavas continue to offer them opportunities for redemption, which they refuse. The war comes to be, justice is delivered, and all the Kauravas perish. However, by finding their end, they find redemption in relative terms, and, as we learn in the last parva, all proceed to svarga, or to heaven.

First, I find it significant to underline that the characters are not passively forgiven and welcomed into svarga. As they refuse to redeem themselves, they are forgiven only AFTER justice is delivered and they are made to take responsibility for what they have done, and after direct action is taken against their misdeeds. Forgiveness or compassion are therefore not passive in this context. I would maintain that what is underlined here is that forgiveness and love do not imply blindness to another’s harmful behaviour; on the contrary.

Second, I highlighted that their redemption occurs in relative terms, because, at the level of the Absolute / Consciousness, there is nothing to be redeemed as there is no fracture, only flow; however, as Ādyashanti teaches, the relative concomitantly and paradoxically very much exists in the container of its own laws.

Of course, the cosmology of the war is much more complex than this and is neither an act of punishment nor one of revenge; I would say it is more of a re-establishment of equilibrium in the relative playing field.

I think this is beautiful to ponder on. No matter how far they fell into cruelty and dejection, they found redemption. Indeed, Draupadī herself as Śrī forgives Aśvatthāmā after justice is delivered, who commits the most gruesome crime there is per Kṛṣṇa (that of killing a child).

And, so can we, can't we? Redeem ourselves and make amends for our cruelties and for our mistakes. Take action when action is needed. And rest in “redemptive love” (another beautiful coinage by Ādya. I love him so much 😊 )

IG: @musingsonthemahabharata

#mahabharata#itihasa#mahabharatam#hinduism#mahabharat#sanskrit#draupadi#krishna#hindu art#religion#pandavas#dharma#sanatandharma#adharma#kauravas#karna#duryodhana#kurukshetra#dharmakshetra#hindu mythology#adyashanti#bhagavadgita

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

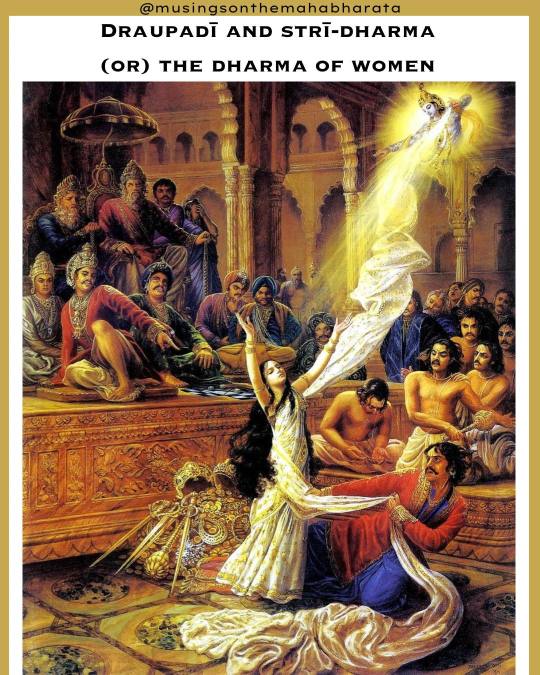

Draupadī and the Dharma of Women

"Strī" translates from Sanskrit as "woman", while "dharma" is a complex principle with manifold meanings, in this context bearing the significance of "duty"; in simple terms, it refers to an individual conduct that contributes to harmony in a greater framework, be it societal or cosmological.

Draupadī is lauded in the Critical Edition of the Mbh several times as being the epitome of strī-dharma, of the dharma of women. (2.62.20; 2.63.25-30; 2.64). Interestingly, she is most intensely praised as such after she angrily (yet elegantly!) questions the men of the royal court and demands justice, being anything but meek and demure. I would argue that this showcases that in the Mahābhārata voicing oneself and standing up for oneself are considered responsibilities belonging to the dharma of women.

To nuance this even more, Eknath Easwaran, an eminent translator of the Bhagavadgītā, highlights that, etymologically, the term "dharma" can be traced back to the root 'dhri', which means 'to support, hold up, or bear'; "dharma" therefore translates as "that which supports", and Draupadī's conduct therefore supports both society and cosmology.

In the Sanskrit Mbh, Kṛṣṇa does not appear in the sabhā (royal hall) at the time of Draupadī's attempted disrobing, and no direct mention of him is made during this episode. In a conversation with Dr. Brian Black, a Mbh researcher whom I had the honour to have as my MA supervisor, we talked about the implication of this, which is that Draupadī's adherence to strī-dharma appears to be that which shields her. A question that could arise here could be whether there is a contradiction between the Critical Edition and modern renderings of the Mahābhārata, with Draupadī being shielded by her dharma as opposed to by Kṛṣṇa.

For me there is no contradiction.

Kṛṣṇa in the Bhagavadgītā establishes himself as 'the eternal dharma' (14.27); and so, Kṛṣṇa is all dharmas, including strī-dharma. We tend to associate Kṛṣṇa with a fully-fledged incarnation; but he is beyond that. I would maintain that, as the divine principle, he exists in Draupadī's consciousness and in her actions as dharma (and not only!). The latter renditions, for me, in which he is physically there, only bring forth in tangible projections the internal process extending Draupadī's consciousness.

You can find me on IG: @musingsonthemahabharata.

Painting: Jadurani Dasi, 1986.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something I find fascinating about the Critical Edition of the Mahābhārata is that the characters sporadically move from addressing Kṛṣṇa as an embodied mortal (as their friend, cousin, son-in-law etc) to addressing him as the Godhead; as Viṣṇu, as the Supreme Being, and as Īśvara. The succession of change between the modes of address can sometimes even happen on the same page, at a distance of a few lines. The veil is lifted, and the characters see through Kṛṣṇa’s illusion, and, through that, they become immersed in the nature of Reality; the veil promptly drops back, and God is lost. An argument for this could be that the divine modes of address are interpolations, a theory being that Kṛṣṇa became identified with Viṣṇu only in later renditions of the Mahābhārata. While this could be true at the level of historical analysis of the epic, for me, there is a subtler teaching encased here: how all of us, without exception, glimpse into the nature of Reality as we move through life, yet we perpetually proceed to return to becoming engrossed in the superimpositions we project upon Reality; and the dance continues. From Truth to dream, from dream to Truth. It is quite endearing, really. What committed and imaginative dreamers we are!

Adyashanti once talked about how one inadvertently glimpses truth; it is, after all, inescapable as it is our nature; the trick is not forgetting / losing the glimpse.

Gorgeous artwork of Kṛṣṇa: Awedict.

#mahabharata#krishna#mahabharat#mahabharatam#gopala#govinda#adyashanti#nonduality#non dualism#non duality#avatara#hare krishna#krishna consciousness#hinduism#hindu art#awedict#bhagavad gita#vishnu#ishvara#bhakti#hindu mythology#itihasa#sanskrit#hindu#gopal

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kṛṣṇa and Draupadī Discuss Karma

One of my favourite interpolations from modern tellings of the Mahābhārata is a conversation between Draupadī and Kṛṣṇa that occurs after Draupadī's sexual assault and attempted disrobing by the Kauravas.

Clutching his feet, Draupadī sobs: "Govind, why? Why did this happen to me? What sins did I commit? I am reaping the fruit of which actions of mine?”

Picking her up and caressing her hair, Arya tells her: "What happened was neither because of your ‘bad’ karma, nor did you reap the fruit of your past actions. It was the Kauravas who reaped the fruit of their past actions by engaging in such a grave misdeed. Sakhī, this is the meaning of karma."

"But I am the one experiencing agony, Govind."

"Then relinquish it, Sakhī. Although what happened was not the result of your 'bad' karma, the way you transform following these events will be your karma."

This is such a beautiful and profound exchange which offers rich nuances to the teaching of karma. Oftentimes, when events we perceive as terrible happen to us, we create a story of unworthiness around them; we wonder if we are being punished, if the root cause is our evilness, if God or the universe are rejecting or dooming us. A question that rests on these lines that is often asked would be the common: “why do bad things happen to good people”. A first layer to this, in my view, is a deconstruction of 'bad' and 'good' as solid concepts. The second layer is the understanding that any event 'just' happens aleatorily, rises and falls, and karma is not a simplistic cause-effect reaction.

Karma encapsulates, in my understanding, the ingrained patterns held within us through which we act, react, and process the world around us and the events that occur in our lives. There is freedom from karma in finding new ways of reacting, engaging, processing.

Finally, a significant teaching encased in this interpolation is that the way someone treats us, ultimately, is a reflection of their karma (ingrained patterns), and not a reflection of our ingrained patterns. We cannot control another's patterns, but we can aim to understand and rewire ours accordingly.

The magnificent art: @beauty_of_art_aditi.

#mahabharata#mahabharat#krishna#draupadi#sakhi#sakha#govind#govinda#hare krishna#mahabharatam#itihasa#hinduism#hindu art#yajnaseni#panchali#mahabharat star plus#hindu#hindu mythology#karma#spirituality#shri#teaching#freedom#mahabharata art#raksha bandhan#religion#sanskrit

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

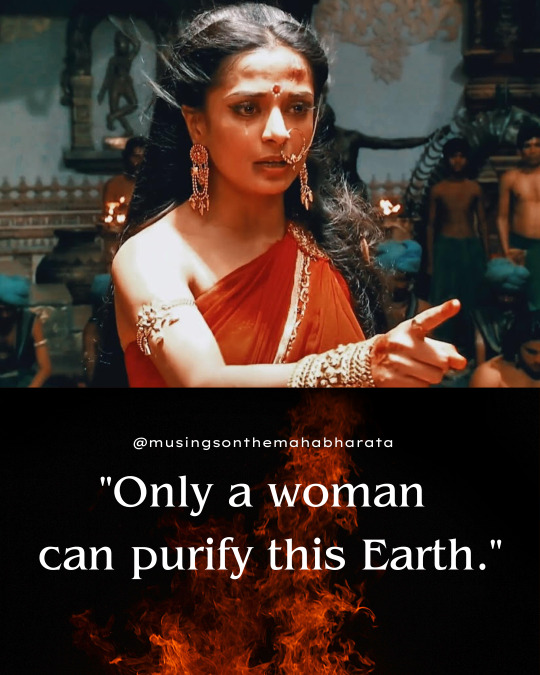

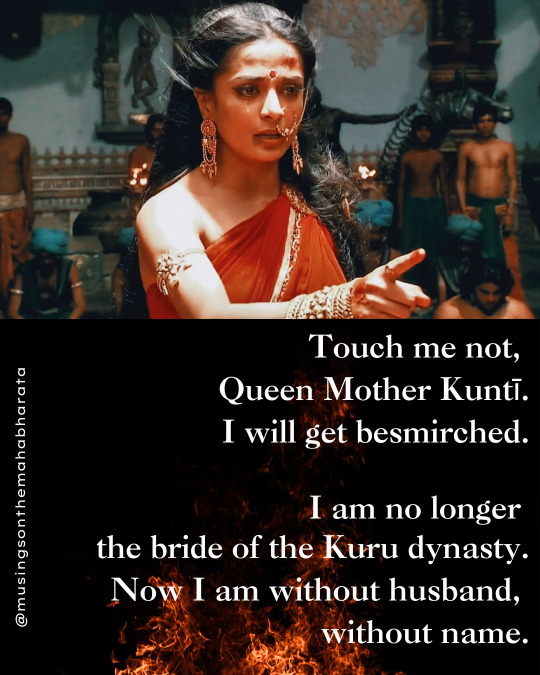

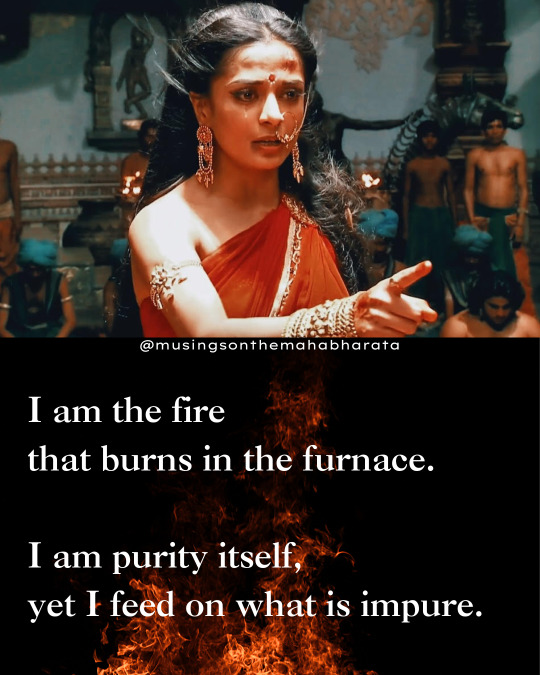

excerpt from an audio-translation I worked on with a colleague of mine; we translated Draupadī's imposing speech as rendered in modern Mahābhārat retellings. Draupadī utters this speech after she is dragged to the royal hall by her hair, and is assaulted & sexually harassed by the men of the Kuru dynasty. she renounces her status as a wife; in the Sanskrit Mbh, symbolically, by refusing to tie her hair again, while in modern renderings, explicitly, by directly renouncing her husbands who passively watched her humiliation.

in this sequence, Draupadī curses the Kurus. the curse bears similarities across the Sanskrit & modern tellings; that just as she bled in the sabhā (royal court / hall), so will all the men bleed on the battlefield, and just as she wept with her hair untied, so will their women cry before their corpses with their hair dishevelled (tied hair was the marking of a wife / bride, untied hair, of a widow).

photo: Pooja Sharma as Draupadī. Pooja is my Draupadī.

#mahabharata#mahabharat#mahabharatam#mahabharata art#pooja sharma#mahabharat star plus#sabha#draupadi's disrobing#draupadi#yajnaseni#hinduism#hindu mythology#itihasa#sanskrit#goddess#shakti#kauravas#kuru dynasty#krishna#sanatana dharma#religion

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

new Mahābhārata reads! 🖤 gift from my amazing supervisor, Dr. Naomi Appleton. 🫶

*Hanuman's Tale is by

Philip Lutgendorf.

#mahabharata#hinduism#itihasa#krishna#mahabharatam#mahabharat#religion#sanskrit#hindu art#draupadi#ramayana#hanuman#phd#phd diary#phd journey#phd student

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

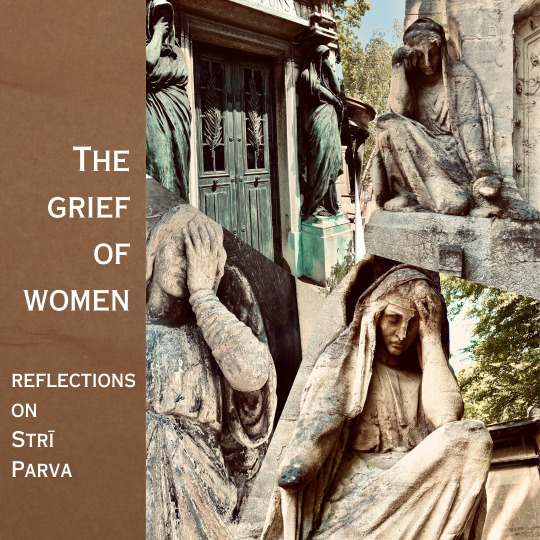

spent today absorbed in the père lachaise cemetery, and one of the things i was struck most by was seeing the many sculptures of female figures towering over tombs: almost all tearful or in distress. it made me think of Strī Parva, “The Book of Women” from the Mahābhārata, which exclusively focuses on portraying women’s grief and tears, who break upon seeing their men & sons slaughtered on the battlefield in the aftermath of the war. one of the distressed female characters, queen Gāndhārī, lashes out at Kṛṣṇa and accuses him of murder, declaring that he could have stopped the war as he is both omniscient & ever-powerful.

Kṛṣṇa rejects her blame and retorts that he cannot override the cosmic laws. he himself is subjected to them; the massacre was ordained, no one is exempt from death, and the cycle of life is definitive.

my understanding of this exchange is: he is not telling her that she should not grieve or that her grief is “wrong”; he merely offers her the opportunity to place it in a larger context and to use her distress to understand deeper herself as well as the web of nature / existence / cosmology. there is no one to blame or resent or victimise; life unfolds as is. and,

even what we understand as ‘negative’ feelings therefore can be utilised as a stimulus for self-reflection. i myself have spent a lot of time simmering in grief without considering what it could teach me, so this particular scene is very profound for me.

and, how beautiful is Kṛṣṇa’s revelation that he himself is subjected to the cosmic laws once incarnated! will elaborate on this in a future article or post 😊

*my retelling of this dialogue is not based exclusively on the critical edition but also on its variations, as this is one of the instances in which i find referring to multi-versions valuable.

photos: some of my favourite sculptures seen in the cemetery!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

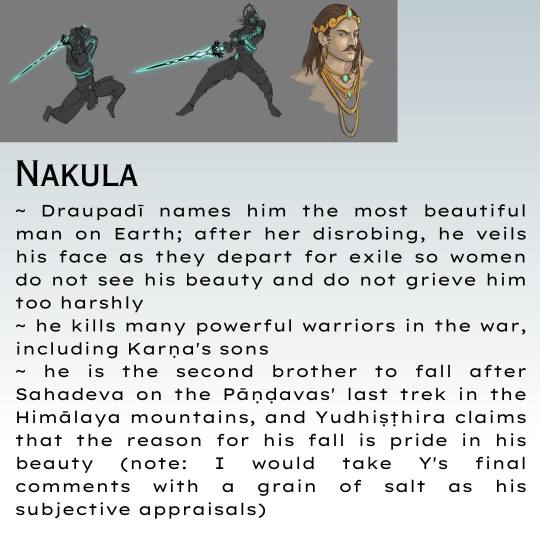

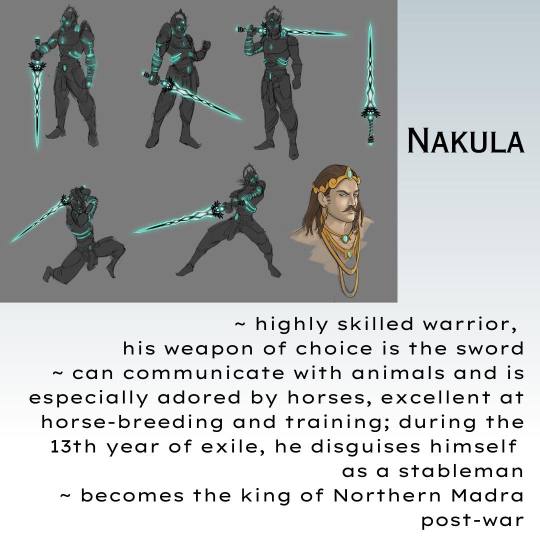

main characters from the Mahābhārata, part V: Nakula & Sahadeva! to me, they are the unsung Pāṇḍavas. not much is known about them mainstream-wise as opposed to the other three brothers - which is unfortunate as they are such interesting characters! i compiled my favourite (and, in my opinion, most fascinating) facts about them in this series, such as:

Sahadeva, the youngest of the brothers, has the gift of sight, which he gains at Paṇḍu's funeral by eating a piece of his corpse that was carried by ants

Nakula can communicate with animals and is especially adored by horses. Draupadī names him the most beautiful man on Earth; after her disrobing, he veils his face as they depart for exile so women do not see his beauty and do not grieve him too harshly

& many more!

artwork credit: Vamchi Vams. (sadly, not much art has been created of them either!)

#mahabharata#mahabharat#mahabharatam#vamchi vams#pandu#nakula#ashwini twins#sahadeva#itihasa#sanskrit#hinduism#hindu art#draupadi#pandavas#yudhisthira#yudhisthir#bhagavad gita#religion#phd#phd thesis#veda#bheema

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

check out this stunning futuristic Mahābhārata art by Vamchi Vams!

the tendency with modern Mbh-inspired artwork is for it to still adhere to 'traditional' / historic conventions and for these to be seen as more 'accurate' renderings, but, especially with the war books (parvas), i'd maintain that one needs only to skim-read to see that the futuristic artwork most likely is a more 'accurate' representation of how the war is said to be fought. it would not be an exaggeration to claim that the astras (supranatural weapons imbued with mantras) used by warriors such as Arjuna, Karṇa & Aśvatthāmā functioned like nuclear weapons. i personally adore futuristic Mbh artwork because in my opinion it enlivens the epic & grounds it in our present as a timeless dynamic work and not as an ancient lifeless poem.

i do wonder if it is the inescapable archaic tone of 99% of the Mbh translations from sanskrit (which my dear friend Avi Sato pointed to me once & now i can't unsee!) that which contributes to this overall impression that traditional renditions * must * be more accurate. perhaps. i for one would love to see a truly futuristic translation and interpretation of the Mbh (both in literature & in film / TV) that also follows the narrative thread faithfully. might take it upon myself.

#mahabharata#mahabharat#mahabharatam#vamchi vams#hindu art#mahabharata art#krishna#govinda#gopala#hare krishna#haribol#arjuna#karna#pandavas#kurukshetra war#ashwatthama#itihasa#religion#sanskrit#bheema#yudhisthira#nakula#sahadeva#kurukshetra#hinduism#hindu mythology

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

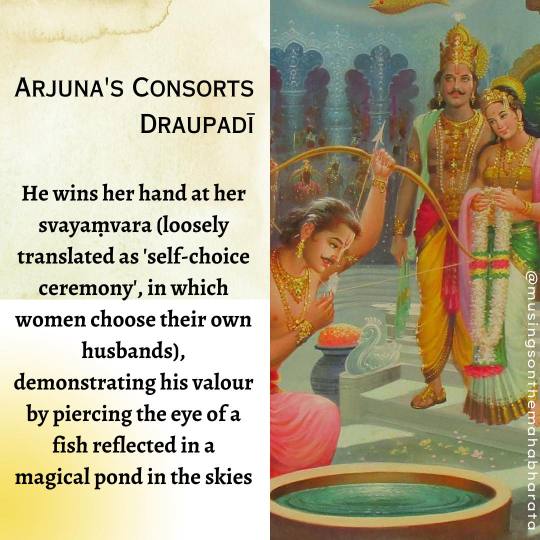

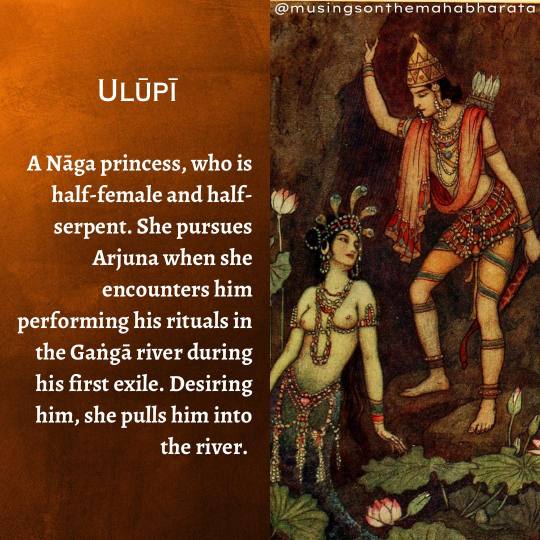

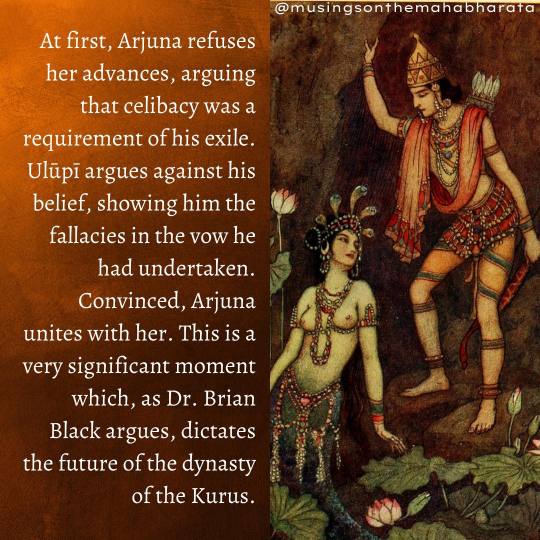

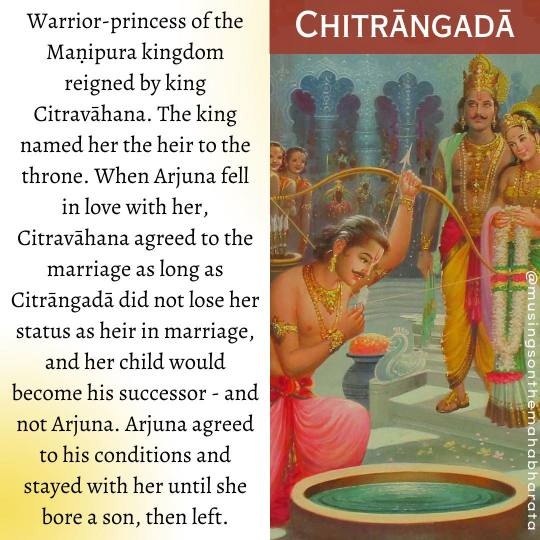

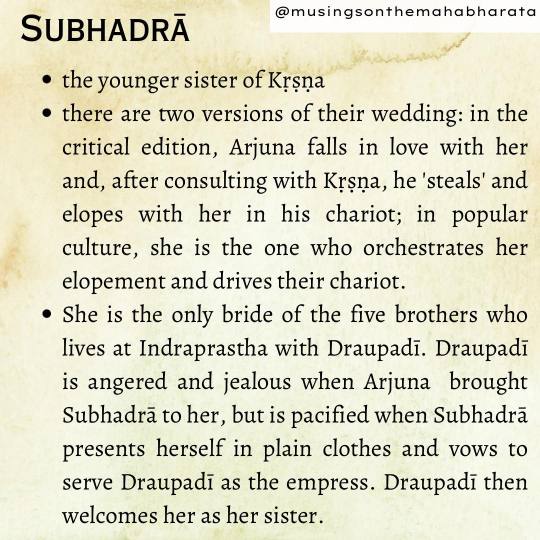

Arjuna's consorts!

#mahabharata#mahabharat#arjuna#arjun#mahabharatam#itihasa#sanskrit#hinduism#hindu art#phd#phd student#phd thesis#subhadra#draupadi#ulupi#chitrangada#bhagavad gita#bhagavadgita#krishna#yajnaseni

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

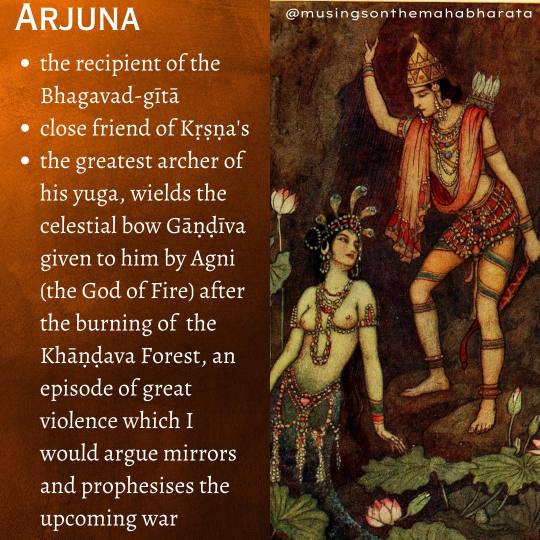

101 on Gāṇḍīvadhārī Arjuna, Maheṣvāsa Dhanañjaya.

he is perhaps best known as the recipient of the Bhagavadgītā and as a highly skilled warrior, but i find that he is often presented one-dimensionally in popular culture, and his well-rounded & complex, captivating nature is overlooked;

handsome, dark and curly-haired, Dhanañjaya (my favourite name of his!) is playful, assisting Kṛṣṇa in his exploits, in which they dress together as women and beguile all who encounter them;

brave and well-schooled in the laws of dharma, he concomitantly does not conceal his love for violence in episodes such as the burning of the Khāṇḍava forest, in which he delights in the unleashed carnage;

such an exciting hero - more below! and this barely scratches the surface!

#arjuna#arjun#mahabharat#mahabharata#mahabharatam#pandavas#krishna#dhananjaya#govinda#gopala#partha#vijaya#khandava#bhagavadgita#bhagavad gita#hinduism#hindu art#giampaolo tomassetti#kunti#hindu#religion#phd#phd thesis#phd life

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

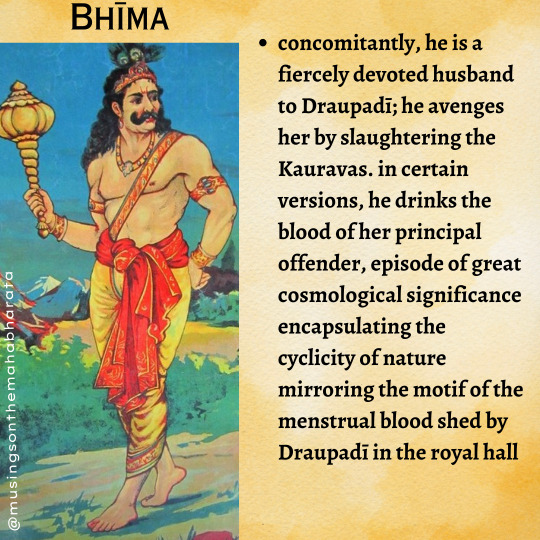

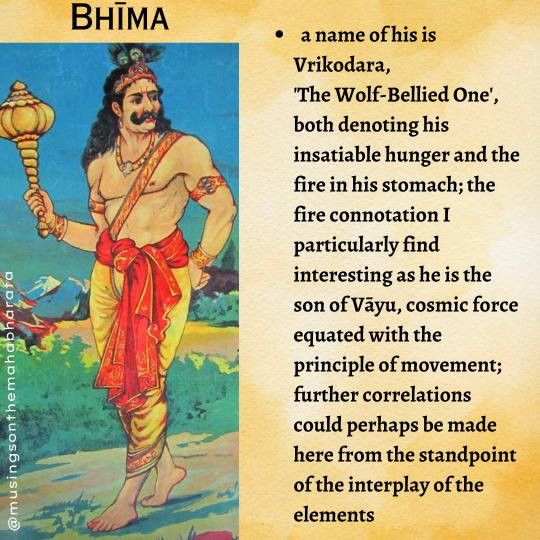

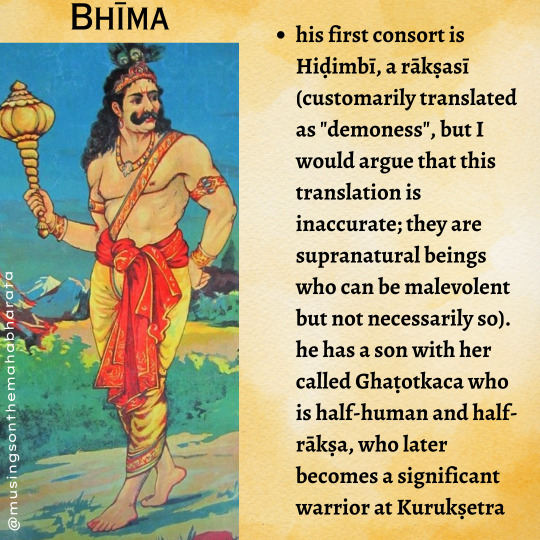

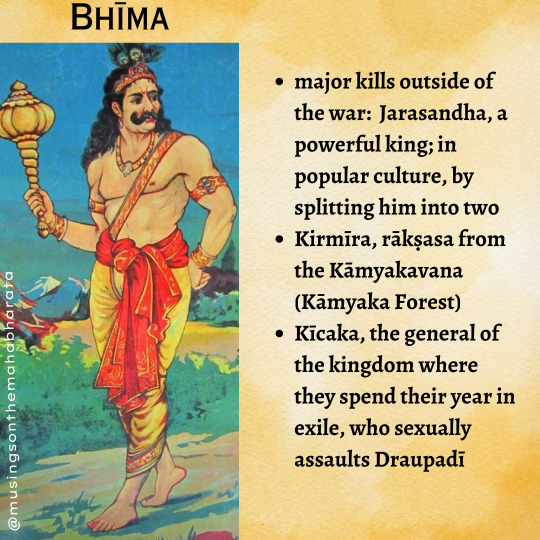

the formidable Bhīma! 🤍 impulsive, strong and quick-tempered as well as fiercely devoted to Draupadī, he avenges her by slaughtering the Kauravas. in certain versions, he drinks the blood of her principal offender, episode of great cosmological significance encapsulating the cyclicity of nature mirroring the motif of the menstrual blood shed by Draupadī in the royal hall. how i adore him so!

you can find my Mbh tidbits on IG here: @musingsonthemahabharata 🤍

artwork: Gita Press Mahābhārata, 1968 | Ravi Varma Press

#mahabharatam#hinduism#spirituality#religion#bhima#bhim#bheema#bheem#mahabharat#mahabharata#hindu art#pandavas#draupadi#itihasa#krishna#sanskrit#sanatandharma#yajnaseni#kurukshetra war

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

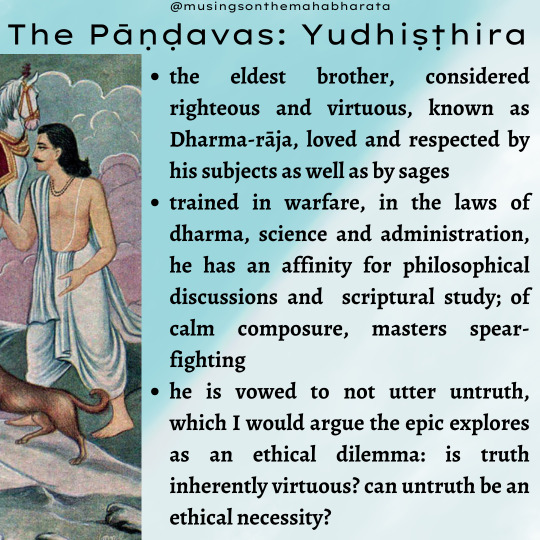

part II of the main characters from the Mbh series: Yudhiṣṭhira! i focused on a few significant themes related to his character which i want to expand on either in my videos or in my papers.

⚜️Yudhiṣṭhira is vowed to not utter untruth, which i would argue the epic explores as an ethical dilemma: is truth inherently virtuous? can untruth be an ethical necessity?

⚜️ Alf Hiltebeitel's take on the fateful dice match being a reflection of cosmological dynamics of cyclical renewal and destruction, connoted with the advent of the Kali yuga prophesised in scenes set in svargaloka with the Goddess Śrī, the principle of fortune and prosperity, who later incarnates as Draupadī, who, in this, becomes the pillar of Yudhiṣṭhira's empire

*Hiltebeitel also explores the game as entity possession (not in the orthodox sense) - more on this later!

book: Hiltebeitel, A. (1990). The Ritual of Battle: Krishna in the Mahābhārata. Albany, United States: State of New York University Press.

⚜️ meeting the Kauravas in heaven; the antagonists entering heaven, i would argue, points to the inexistence of solid concepts of 'right' and 'wrong'; each character had their part to play in the Mbh, beyond morality, righteousness and evilness, which are fluid concepts

⚜️ painting from the illustrated Mbh published by Gorakhpur Geeta Press.

#mahabharata#mahahabharat#mahabharatam#hinduism#spirituality#yudhishthir#yudhisthira#hindu#religion#sanskrit#itihasa#literature#alf hiltebeitel#krishna#scholar#phd#phd life#phd thesis#hindu mythology#draupadi#shri

14 notes

·

View notes