Text

The Weight of the Inside of the Body

Saskia Hamilton, 1967–2023

Last week was Pongo Poetry Project's annual gala/fundraiser, Speaking Volumes, and during the event the guest poets—Arianne True, Shin Yu Pai, and Quenton Baker—were asked to name someone who was influential to their writing and their interest in poetry.

As the poets talked, I thought about Saskia Hamilton, who died this past summer at only 56. What a terrible loss.

It's both a blessing and a curse to be less extremely online than I once was.* On the one hand, social media can be corrosive; on the other hand, social media can help one stay on top of the news. I only heard about Saskia's death a few weeks ago, when I logged into Instagram for the first time in ages (somehow I'd missed the Times obit). I was, to put it mildly, super bummed.

Saskia was the first writing teacher I really looked up to—I took a workshop with her when she was at Kenyon between 2000–2001—and though we fell out of regular touch, I eagerly read her books as soon they were published.

In addition to being a talented poet and editor, Saskia was, more importantly when I was 20/21 years old, cool: she invited our workshop to her apartment in Mt. Vernon one night, and I drank a Grolsch; she grew up with Guy Picciotto of Fugazi (my favorite band!!!) & so knew the band well & we drove from Gambier to Carnegie Mellon to see them play one Saturday morning (something I've written about previously); when she taught at Kenyon she tended to wear lots of black, effortlessly; and when I was applying to grad school, she told me to stay in NYC and not decamp for Minnesota, advice I ignored. Maybe I shouldn't have?

The older I get, the more of my heroes I say goodbye to. The good news, amen, I suppose, is that their work remains, and with it some small part of them. Here's her poem "Zwijgen," from Corridor:

I slept before a wall of books and they

calmed everything in the room, even

their contents, even me, woken

by the cold and thrill, and still

they said, like the Dutch verb for falling

silent that English has no accommodation for

in the attics and rafters of its intimacies.

...

*Thanks to Musk & Zuckerberg—erstwhile combatants—for driving me from their respective websites.

Title taken from Saskia's poem of the same name, which opens her collection Divide These.

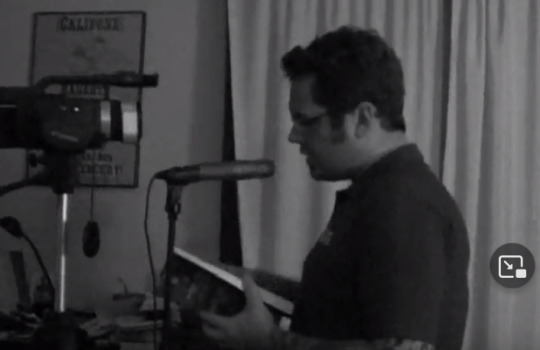

Header image of Fugazi, mainly Ian MacKaye here, playing "Waiting Room" during the CMU show. Here's the full (short) video from which the header screencap is taken:

0 notes

Text

Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

The old saying about teachers learning as much from their students as students learning from teachers is certainly true, but in my years of teaching I've encountered another truism* that's less frequently bandied about: the process of preparing to teach can be just as educational (if not broadly edifying) as teaching itself.

Case in point: the short video I found, when preparing for the final meeting of my recent Hugo House class, of Ed Yong discussing the role writers play in communicating science. Here's its juiciest quote:

Good science journalism is also an important corrective force; it's a wall that stands between the public and this huge amount of hype and misinformation and vested interests, and it's the tension between these two sides that informs the work that I do. Writing that reveals how incredible the world around us is, and that also calls out bullshit when it's necessary.

And here's the video:

youtube

What Yong is saying isn't new, but it is nice and succinct. And one could easily replace the phrase "science journalism" with any sort of nonfiction writing/storytelling/creative discipline; the point is the placement of the writer between the material being turned into a story and the audience for that story. It's the writer's—the interlocutor's—job to ensure that the story being told is both true to the material and to the audience. They serve both masters, so to speak.

Which brings me (as does so much these days!) to artificial intelligence. If indeed "90% of online content" will be AI-generated by 2025, then the role writers/interlocutors play will be even more important—they will ensure trust.

Sure sure, that 90% number feels both picked out of thin air and likely to cover all sorts of clearly-just-marketing-or-spam "content," but the point remains that AI will likely make human writers and human curators all the more important. As Patrick Nathan put it in his book Image Control, in "the rushing flow of commodities, a dialectical approach to the art we make and the relationships we forge is the rock in the river, the stick in the spokes."

Meanwhile, to underscore my point, The Atlantic recently reported that an enormous database of pirated books has been used to train several large language models. "Upwards of 170,000 books, the majority published in the past 20 years" are included in a dataset called "Books3," which includes "nonfiction by Michael Pollan, Rebecca Solnit, and Jon Krakauer" and "thrillers by James Patterson and Stephen King and other fiction by George Saunders, Zadie Smith, and Junot Díaz."

!!!

To which no less than Margaret Atwood responded thusly:

A former teacher of mine once said there was only one important question to be asked of a work of art: “Is it alive, or is it dead?” Judging from the results I’ve seen so far, AI can produce “art” of a kind. It sort of looks like art; it sort of sounds like art. But it’s made by a Stepford Author. And it’s dead.

...

Header image, Brueghel the Elder's "The Alchemist," 1558, ink on paper, via Wikimedia Commons.

Yes, the title is a reference to the Walter Benjamin essay.

*Speaking of truisms:

#Youtube#ai#articifial intelligence#chatgpt#writing#criticism#walter benjamin#margaret atwood#the atlantic

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't worry, Rickey.

You're still the best.

Tomorrow is already the final session of my Hugo House class on data storytelling, and gee whiz has it been great to teach in person again. It had been a while! I was pretty rusty for the first couple of weeks! The pandemic really did a number on time and being-used-to-in-person interactions, didn't it?

Regardless, it's been great to talk data shop with the class and, in the grand tradition of teachers everywhere, to foist my interests on them. Such as baseball!

Because it's broadly popular, filled with wacky stories (see Ellis, Dock), and is our most data-driven sport, baseball is an excellent data storytelling teaching tool.

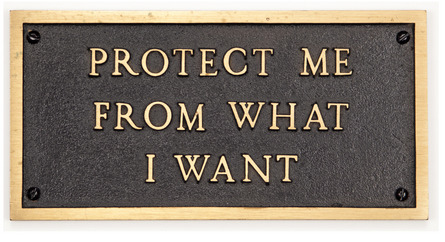

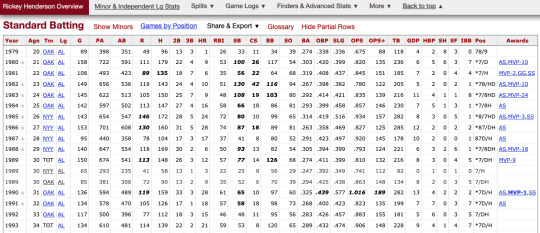

One of the first exercises I did with my class was very simple—we examined two players' lifetime stats, namely Rickey Henderson's and Von Hayes's, and looked for stories therein. There was no number crunching or anything, just numbers. Like so:

Rickey Henderson

Von Hayes

Granted, I'm a baseball nerd, so the idea of looking at rows of stats and seeing which (if any) stories jump out sounds like fun to me. To wit: Henderson is the all-time leader in both stolen bases and times caught stealing, which tells you much about his appetite for risk.

And Von Hayes, who mainly played for the Phillies and whom I met when I was kid (hence his inclusion) had a much shorter, less illustrious career shortened by injury. That leads one to wonder about how he dealt with disappointment, what his career might have looked like otherwise, etc. etc.

Number-induced navel gazing aside, being able to see stories in numbers, or at least the beginnings of stories, is a useful skill to cultivate in such a data-driven time. After all, life is weather, life is data (to butcher James Salter). And, huh, what on earth was Rickey up to in 1989??

Maybe Robert Angell's brief, masterful "Rickey," from The New Yorker, can tell us:

"Everything about him made you wince and gasp at the same time. How does a major-league ballplayer, for instance, end up playing for nine different teams, while also rejoining his first team, the Oakland Athletics, four times?"

...

The title of this post is borrowed from a Rickey Henderson quote which may be apocryphal but I choose to believe that it isn't. He supposedly muttered this to himself in Seattle, just after striking out. The man did refer to himself in the third person frequently.

Header image of Rickey stealing second via Wikimedia Commons.

Rickey Henderson and Von Hayes stats via Baseball Reference.

PS: Here's Rickey hitting a home run in his first at-bat as a Mariner. He was 41 at the time. Just spectacular.

youtube

#baseball#data#data storytelling#rickey henderson#writing craft#data analysis#data driven#mlb#oakland athletics#philadelphia phillies#von hayes

1 note

·

View note

Text

Charlie Foxtrot

The last few news cycles have been packed, so it's understandable if you missed the Biden administration's recent decision to send cluster munitions—also known as cluster bombs—to Ukraine.

I'm not alone in disagreeing with this decision; The New York Times editorial board noted that cluster munitions are not "a weapon that a nation with the power and influence of the United States should be spreading."

What, then, are these things? And why are some people (myself included!) so opposed to the use of cluster munitions?

Briefly, cluster munitions are "any of a number of weapons systems which ... deliver clusters of smaller explosive submunitions onto a target," according to the Convention on Cluster Munitions. They have a "propensity to leave behind large numbers of unexploded remnants which exact an even greater indiscriminate toll amongst civilians."

The weapons we're sending to Ukraine contain 88 "bomblets" in each round, and each "bomblet has a lethal range of about 10 square meters, so a single canister can cover an area up to 30,000 square meters (about 7.5 acres), depending upon the height it releases the bomblets."

This is obviously bound to cause harm after the war is over. How much harm is the question—tracking mine and cluster-munition injuries is difficult, and the data are poor.

The Global Burden of Disease doesn't include separate causes for mine or munition-related injuries/deaths (they're lumped under "conflict and terrorism"), and the ICD-10 doesn't even include a code relating specifically to cluster munitions; Y36.81, "explosion of mine placed during war operations but exploding after cessation of hostilities," comes closest.

Nonetheless, even if the data are poorly classified and/or underreported, land mines, cluster munitions, and other "explosive remnants of war" (ERW) clearly constitute an ongoing threat.

Stats: during the Vietnam War, the US military dropped more than 250 million cluster munitions, of which 9 to 27 million unexploded submunitions remain. And according to the Landmine & Cluster Munition Monitor, "since global tracking began in 1999 the Monitor has recorded more than 122,000" casualties due to land mines and/or ERW.

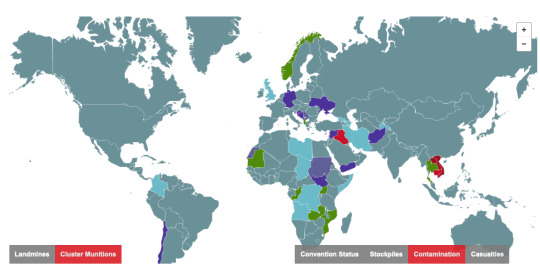

Here, from the same organization, is a map showing current (2018) cluster munition "contamination" around the world. Red and dark red = bad.

To put the harm cluster munitions cause in more human terms, here's a picture of farmers from Vietnam who were injured by leftover bomblets.

Of course, not everyone agrees that the US shouldn't send Ukraine cluster munitions.

Turkiye began sending Ukraine cluster munitions earlier this year, and Russia has been using them against Ukraine for some time, as the Washington Post's Max Boot points out:

Boot's use of the term moral equivalence—even if he's denying that there is one in this case—brings to mind Noam Chomsky's characteristically forceful take on the phrase:

"Moral equivalence is a term of propaganda that was invented to try to prevent us from looking at what the acts for which we are responsible ... I reject that reasoning."

Perhaps a simpler way to look at this whole clusterfuck is: two wrongs don't make a right. Take it away, Barrett Strong.

youtube

...

Header image via Wikimedia Commons.

Cluster bomb victims' hands also via Wikimedia Commons.

Etymology bonus: the term "clusterfuck," in the sense of "bungled or confused undertaking" or "fuckup," arose as military slang during the Vietnam War.

When referring to a clusterfuck over the radio, or in the presence of parties they'd rather not curse in front of, members of the military would instead refer to something as a "Charlie Foxtrot," hence the title of this piece.

0 notes

Text

Speaking of Endings

A truism of writing in the digital age is how little time people spend on any page, and how infrequently they read (or even scroll) to the end. Stats: 35% of readers leave pages without scrolling at all, 45% who load an article/page leave within the first fifteen seconds, and most people only view the top of a given page. But also, super interestingly, readers who make it below the fold tend to stick around.

Which brings to me endings.

Endings have always struck me as the most important part of a piece of writing, after (maybe?) the title & lede. It's the ending that sticks with the reader and leads to rereading & reexamining. And of course endings, outside of writing, can color how you think of an entire experience.

A famous example from poetry is the final line of James Wright's "Lying in a Hammock in William Duffy's Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota," in which the ending turns the entire bucolic-before-the-last-line poem on its head. Here are the last seven lines (from a thirteen-line poem):

To my right,

In a field of sunlight between two pines,

The droppings of last year's horses

Blaze up into golden stones.

I lean back, as the evening darkens and comes on.

A chicken hawk floats over, looking for home.

I have wasted my life.

Oof.

Then there are the sorts of endings that the generally intense post-punk band Protomartyr excels at, the ending that everything builds toward. This sort of songwriting—writing for the end—may be the most defining characteristic of their new album Formal Growth in the Desert, the band's sixth full-length.*

A good example of this is "Polacrilex Kid," a song named after one of the ingredients in nicotine gum that includes the lyrics "keep the hate in your mouth / buy it drinks / keep it fed." The last two minutes of the song, in which Protomartyr's singer Joe Casey shifts from shouting to almost crooning the lines "can you / hate yourself / and still deserve love?" are particularly devastating.

youtube

Likewise, the last minute of "We Know the Rats" is the reason I keep coming back to that song. I actually don't love the first ~2 minutes of the WKtR; my main criticism of the Formal Growth in the Desert overall is that a number of the songs seem to stutter at the start before settling into themselves.

Nonetheless, boy oh boy does "We Know the Rats" ever settle into itself: "so collect those tears / and wash your face / the house is empty / but the work remains."

youtube

Finally, there's Kevin Prufer's new collection of poetry, The Fears**, which is forthcoming from Copper Canyon. I've yet to finish reading the book, but so far Prufer's endings are masterful. They're also exactly the sort of endings I was praising above, the kind that lead to reexamination.

Here, to close, are the final few lines of "A Body of Work," which seems an apropos way to end a post about endings.

For instance, I am alive, right here,

in the middle of my poem, having had, perhaps,

too much to drink. One comes, eventually,

to the certainty that one’s body of work

is nothing like another man’s progeny, being

made of language, which can only veer

toward emptiness as years become empty space.

For instance, hello? I am calling out to you,

folded here between the pages

of generations. You don’t know me, but once

I was particulate and alive. Now what am I?

...

*Protomartyr rips; they may be my very favorite band of all time.

**I'll absolutely be writing about The Fears at length elsewhere, soon. Stay tuned.

Top photo of Protomartyr via the UT Connewitz Photo Crew's flickr.

Speaking of endings, RIP Cormac McCarthy and Rick Froberg.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Where There's Smoke

A few years ago, I contributed to a World Bank report about the costs of air pollution. Though the project was interesting, and everyone I worked with was brilliant, at the time air pollution wasn't something I thought about frequently. And if and when I did think about air pollution, I considered it much less of an immediate concern than, say, gun violence.* It didn't feel urgent.

But then I experienced my first truly bad smoky Seattle summer** and I began thinking about air pollution, specifically PM2.5, extremely frequently. Being shut in the very hot indoors without air conditioning in the middle of the summer because the outdoors smells like a campfire and because it hurts to breathe...will do that.

As unpleasant as the Northwest's air was, and though it produced many a sensational headline, it remained a regional issue for much of the U.S., something the West and largely/only the West really experienced. And as such, it was easily ignored.

Then last week's northeastern airborne toxic event (to borrow DeLillo's term) took place. Now—or at least for a while!—we're all thinking about air pollution!

Better late than never. Per the State of Global Air map below, much of the world has been living with unacceptably high levels of PM2.5 in the air for years now (note that these are 2019 data, the most recent year for which data are available).

In the same year, "particulate matter" was the second-highest risk factor for health burden globally, higher than smoking. Of course, 2019 was four years ago; one can only wonder how things have progressed since.

For more, read Mike Brauer's Think Global Health piece today on wildfire smoke. "This new normal will worsen before it improves, so the challenge is to adapt to the reality of fire smoke and minimize its health impacts." Sigh!

...

*I was also preoccupied with the astounding prevalence & growth of so-called high-income health issues (i.e., non-communicable diseases). In 2016, for example, the leading global cause of disease burden was cardiovascular diseases.

**in 2017. 2018 was also rough.

Top image of Tom Petty, playing "himself" in The Postman, via Vanity Fair. Here's the unforgettable scene where he meets Costner's character:

youtube

Air quality screenshot, which wasn't even the peak AQI number (!!!) for NYC, from AirNow. Grim PM2.5 map from State of Global Air 2020. Also, apropos:

youtube

#the postman#air pollution#pm2.5#public health#airborne toxic event#don delillo#think global health#smokey bear#Youtube

0 notes

Text

GPT on Graham

One of the nice, nice but frustrating, things about being a book reviewer and having friends at various publishers is that they're always sending me books, either in the hope that I'll review said books or to keep me in the loop or because my friends are simply cool, etc. Which is great! Being sent books is spectacular! But it can also be frustrating because I don't always—often?—have time to read everything I'm sent, let alone to pitch reviews to publications & then actually write about the books I'm sent.

Case in point: Jorie Graham's latest collection of poetry, To 2040, which was recently published by Copper Canyon Press. Maybe ChatGPT can help?

Though I haven't finished formulating my thoughts about the book, so far its themes are similar to those present in Graham's work since 2008's Sea Change, i.e., worries about climate change, technology, and the anthropocene writ large. Here are the opening lines of "Translation Rain" from To 2040:

I am writing this in code because I cannot speak or say /

the thing. The thing which should be, or I so wish /

could be /

plumbed fathomed disinterred from this silence, this ever thickening /

silence through which, once, the long thin stalks & stems, first

(Quoting Jorie Graham is difficult since so many of her lines are enjambed, and because right-aligned lines bedevil online text editors.)

So with both my backlog & Graham's hesitation about technology in mind, I wondered: what might ChatGPT have to say about her work? Nothing about To 2040, of course—because of how it was trained, the tool has "limited knowledge of world and events after 2021" according to OpenAI. Nonetheless, asking ChatGPT about Jorie Graham's work, of all technophonbic-leaning writers, strikes me as particularly...poetic. I don't know whether she'd be amused or offended. Both?

Here's ChatGPT's first go, in response to "write 100 words about Jorie Graham's poetry":

Jorie Graham's poetry is a captivating exploration of language, consciousness, and the intricate threads that weave through our lives. Her verses shimmer with a remarkable blend of intellectual rigor and emotional resonance, challenging readers to engage with complex themes and ideas. Graham's language is lush and evocative, creating vivid images that dance across the page. Her poems often grapple with existential questions, probing the boundaries of identity and the nature of time. Through her profound insights and lyrical craftsmanship, Graham invites us into a world where language becomes a conduit for profound introspection, offering a glimpse into the mysterious depths of human experience.

Not too bad, but the prose is overly purple for my taste, and my dude really could have gone easier on the adjectives. What then, I wondered, would ChatGPT have to say about Graham's work in fewer words? Here's "write 50 words about Jorie Graham's poetry":

Jorie Graham's poetry is a lyrical exploration of the human experience, blending intricate imagery with philosophical depth. Her words unravel the complexities of existence, delving into themes of time, memory, and our connection to the natural world. Through her evocative language, Graham invites readers to contemplate the profound mysteries of life.

Better, but still a bit flowery and overly broad. We're getting there.

Last but not least, "write 25 words about technology in Jorie Graham's poetry":

Jorie Graham's poetry embraces technology's paradoxical nature, exploring its power to connect and isolate, to illuminate and obfuscate, revealing its complex impact on human existence.

Well done, ChatGPT—this is the best yet, if only because you've managed to describe AI's impact, at least in the early going: "to illuminate and obfuscate." Which also sounds like poetry's impact? Indeed, brevity is the soul of wit.

...

Header image via Dall-E 2, generated by entering the prompt "painting of a robot typing after henri matisse," which was inspired by Matisse's "The Violinist at the Window" and Graham's "The Violinist at the Window, 1918" from Sea Change. The stunning opening lines of which read:

Here he is again, so thin, unbent, one would say captive—did winter ever leave—no one / has climbed the hill north of town in longer than one can remember—something hasn't / been fully loaded—life is blameless—he is a stem—& what here is cyclic, we would so

0 notes

Text

At a Distance

Some* records simply demand to be listened to on headphones, including Bill Orcutt’s Music for Four Guitars, which I’ve recently gotten into.

I’m a few months behind—MfFG was released in September 2022**—and I’ve only listened to the album a handful of times, but hoo boy has it been love at first sight. MfFG is one of those works of art that is both excellent and, just as importantly, is inspirational in its excellence.

What do I mean by that? Well, the art that I think of as inspirational is the sort of art that makes one want to go out and make art of one’s own (or at least write reviews on one’s blog). How exactly one defines art-that-is-excellent-and-inspirational vs. art-that-is-simply-excellent is harder to define, and may in fact be entirely subjective, but I’ll just say that the art that inspires me tends toward the difficult and/or the meditative, which MfFG definitely is. It’s difficult and meditative.

MfFG is a collection of short, two minute-ish songs that’s clearly descended from minimalist compositions like Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians (note the titles), albeit with a harder, electrified-guitar edge, as if Glenn Branca had snuck into a Reich ensemble.

That makes sense, because much of Orcutt’s work—going back to his time in the noise group Harry Pussy*** (yes, that was their name), a band New Noise Magazine described as “truly intimidating and strange”—has been atonal and aggressive, not the sort of music you’d put on for company. Which makes Music for Four Guitars that much more compelling, since it’s downright melodic and soothing compared to Orcutt’s earlier output. Sure, a touch of the caterwauling and feedback that marks Orcutt’s work is there, though not as stridently as before.

And this progression is part of what I find inspiring about the record. That and the transporting music, of course. Given the degree to which I’ve been grappling with and/or thinking about writer’s block, I’d say I’m on the hunt for inspiration. Have I been experiencing “a stress reaction that paralyzes the ability to put thoughts into words” as Canadian Family Medicine defines writer’s block? Uh, maybe? Regardless, work like Orcutt’s MfFG is eminently welcome. Experiencing the art of other artists can be just as pleasurable as creating art oneself.

...

*All records?

**Orcutt, who is quite prolific, already has another record coming out. Jump On It releases 4/28 and is “a collection of canonical, mature acoustic guitar soli to contrast against the fractured downtown conceits of previous acoustic releases.”

***Here’s footage of Harry Pussy playing in 1997. Proceed at your own risk.

youtube

Additional notes:

Header image of Orcutt via the Del-Uks Flickr photostream.

Title of this blog post is taken from the song of the same name from MfFG.

Here’s a live performance of the entirety of Music for Four Guitars! It rules!

youtube

0 notes

Text

Panic & Neglect

Last month, IHME colleagues and I published a story in Think Global Health about how spending on global health, specifically spending to prevent pandemics, has been marked by periods of “panic and neglect,” to use a now-popular World Bank phrase.

While ours wasn’t the first piece on this topic (check out these Google search results / we did, ahem!, cite new estimates), I’ve been thinking about the phrase “panic and neglect” a lot over the past few weeks. Namely how applicable it is to so much more than spending and health.

The two words do indeed go together nicely, as a sort of non-aural onomatopoeia, insofar as panic can lead to neglect of the thing that caused panic in the first place, thus leading to additional panic, then more neglect, ad infinitum.

Which is a Freudian way of viewing a psychological—or in the case of the TGH article, a social-psychological—response to shocks and stress; per Freud, repression is pushing “pathogenic experiences ... out of consciousness.”

But there’s another, possibly more sympathetic, way of viewing the panic-neglect duality: that we have simply too much to pay attention to. As an MIT paper points out, working memory has

a severely limited capacity: we can only hold a few thoughts in our consciousness at once. In other words, the surface area of our mental sketchpad is quite small. This limitation is obvious whenever we try to multitask, such as when we attempt to talk on the phone while writing an email, and it is why using our mobile phones while driving increases accident risk, even if we are using a hands-free set.

What’s more, maybe the “neglect” in P&N can perhaps be an overly judgmental way of describing what’s happened, given the negative connotations of the word. The etymology of “neglect” supports this, as it comes from the Latin neglegere, “not to pick up.” Nothing inherently negative about not picking something up, right?

So perhaps instead of referring to the (calm?) post-panic period when one, or one’s society, is relieved to no longer be panicking about the thing one was panicking about as “neglect,” we should call it...forgetting. Or per Freud, something like “repression.” Suppression? Omission? Deliberate inattention in favor of things that require immediate attention?

The thing, as Joe Dieleman and Angela Micah and I noted in Think Global Health, is that repression/neglect/etc. can have disastrous consequences indeed when the thing being shall we say ignored is as big as *getting ready for another pandemic.* The moral of the story then, I suppose, is that one should pick one’s battles when it comes to not thinking about the thing one was panicking about. So maybe neglect the weeds in your garden, but not the exotic coronaviruses lurking in wet markets.

...

P.S. If you’ve read this far, you deserve some plague-Python. I feel happy!

youtube

Header image via Wikimedia Commons. Body image via the Wellcome Collection.

0 notes

Text

What’s the Frequency, Kenneth?

Currently, I’m reading Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation, which is based on his 1969 BBC series of the same name, the subtitle of which—and this is important—is A Personal View by Kenneth Clark.

The series, when it aired, was a hit; millions of people in the UK and US watched a British man with jumbled yellowed teeth and a refined accent share his “personal view” of basically the entire history of Western civilization and art, in pursuit of a definition of civilization, which he never quite pins down. Millions of people watched this! Can you even imagine!

I mean, I definitely can, because I went and bought Clark’s book after watching much of the series. But I’m not a typical TV viewer (to wit: my wife and I watch a lot of Gardener’s World, which is a balm for the busy brain.)

For sure, Clark’s overview of art and history—as impressively erudite as it is—is flawed in the extreme. In addition to taking a myopic Western-only view of history, Clark’s views are generally old fashioned. For example, “Clark is outrageously committed to the “great man” approach to history and to the concept of genius,” writes Morgan Meis in his essay about the series for The New Yorker.

But to focus only on its warts does a disservice to Civilisation, because the series (and book, which improves on the series in ways) are just a delight. It’s a pleasure to experience Clark’s deep knowledge of art history—he was a museum director by twenty-seven—and his, ah, arrogance lends the proceedings a certain panache. Clark makes lots of proclamations. And his language throughout is direct in the manner of the best proclamations. For one, he describes Giovanni Santi, Raphael’s father, as “a silly old creature...the sort of obliging mediocrity who is always welcome in courts.” And here’s his description of Rome:

...a city of weight, a city that is like a huge compost-heap of human hopes and ambitions, despoiled of its ornament, almost indecipherable, a wilderness of imperial splendour, with only one ancient emperor, Marcus Aurelius, above ground in the sunshine through the centuries.

That’s the stuff. Clark’s writing is so bold that the book frequently astonishes. And what a run-on of imagery! We could all learn a bit from Kenneth Clark’s writing. Again: millions of people watched this. Millions!

In closing, here’s the opening of the first episode of Civilisation. Shows just don’t begin they way they used to (with 1.5 minutes of severe organ music and zero talking).

youtube

...

Header image, of a picture of Clark and a painting based on it by Charles Sims, via Wikimedia Commons.

Now here’s some bonus R.E.M.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phoning It In

The fifth episode of the new season of The Crown starts with a 1989 phone call between Prince Charles and Camilla Parker Bowles, which conversation eventually led to a media frenzy—dubbed “Camillagate” or, ah, “tampongate”—after it was recorded by an amateur radio operator, who then sold his recording of the call to the press.

Per its (second) nickname, the conversation between Charles and Camilla was indeed intimate. But I was more interested in the part of the conversation The Crown recreates: at the beginning of their call, Charles asks Camilla to listen to a speech he’ll be giving on the state of the English language.

Here’s some of their exchange:

Charles: If we want to produce the next generation of great writers, we must use our education system to protect what is surely our greatest national export, the English language. Which, like any language, is so much more than a collection of words. It is a means of building bridges between people of different backgrounds, cultures, and generations.

What do you think?

Camilla: I think it's brilliant. I think you could go further. Our language is like an endangered species that needs to be protected. It's a scandal the way we're letting it be slaughtered.

(as far as I can tell, this is the real speech this exchange is based on)

Though the tone of Charles’s (actual) speech is extremely patrician—which is to be expected, given the speech’s source—he makes some points with which I agree, or least points that resonate with things I’ve been thinking about lately. Specifically when he says “[i]f we do not communicate effectively with one another, then we create confusion and lose our way.”*

This is hardly groundbreaking stuff, but lately I’ve been thinking about overuse of language, specifically how overuse of terms and phrases renders them essentially meaningless. More than meaningless, really; the more you say a word, the more it can become little more than a sound. Kevin kevin kevin kevin kevin kevin.

This is something to especially watch in corporate or institutional writing, where hard word limits + complicated ideas can combine to make buzzwords, jargon, and shorthand attractive. Which is all well and good until the buzzwords begin to mean less & less through overuse.

Which can be through no fault of one’s own. For example, perhaps what you’re writing about really is unprecedented, but others might also have ideas about what is unprecedented and so are using the word unprecedented ad nauseam until it seems we’re all writing in shorthand and lo! you’ve basically written a longer version of the lol nothing matters gif.

(Below: an icon, not a snack box)

I’m clearly not the only person thinking about this; Atlassian, on its official blog, published a story titled “6 examples of corporate jargon you should stop using now,” while The Spectator recently published a piece on the overuse of “iconic,” which includes this lovely example, emphasis mine:

When Virgin was still running the Euston to Liverpool line, a friend heard the onboard hospitality manager on the tannoy apologising to everyone in first-class that ‘due to supply issues beyond our control, we have run out of Virgin’s iconic complimentary snack box’.

To close, here’s another speech, from the Scottish play:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

...

*Charles also said that “ours is the age of miraculous writing machines but not of miraculous writing,” which brings to mind the recent ChatGPT excitement.

Header image of then-Prince Charles and President Nixon—who no doubt shared a dislike of having their conversations taped—via Wikimedia Commons.

Icon image, Saint Andrew, Greek 14th century, via the Walters Art Museum. The Walters is a gem. An...icon...even.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Trash! (data)

That I think about trash often isn’t news. But I’ve been thinking about trash more often than usual because our cross-country move into a fixer of a house has meant that we’re dealing with both the detritus of moving—empty cardboard boxes, the handful of broken things that broke during the move, the larger handful of things that should never have been moved at all—as well as the trash that accumulates when one fixes up a house. It’s shocking, really.

As such, I’ve made a couple of trips to Seattle’s South Transfer Station, where residents can drop off trash of all sorts. In my case, it’s been lots of recycling—mixed paper and moving boxes, all of the bulky things that would never fit in our bin. And the South Transfer Station, as the photograph above attests, is quite the place. It’s huge, its smell is amazing, and now I’m thinking about writing something long about trash.

I’ve written about trash in the past—I find it an endlessly fascinating topic, in part because trash is so endless—but now I’m thinking about writing something truly long about it. Maybe a book. I don’t know.

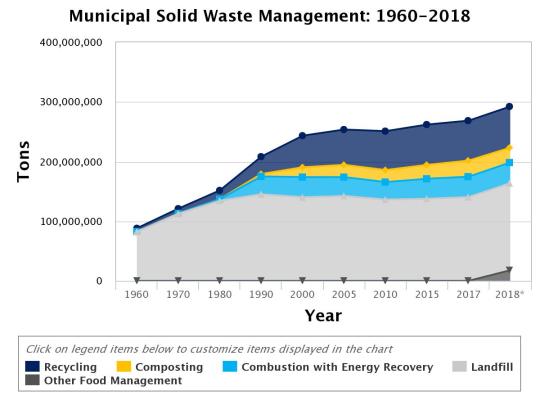

See, trash is interesting on a number of levels. First, there’s so much of it—see the chart below from the EPA re: the growth of trash between 1960 and 2018; the U.S. alone produces roughly 300 million tons each year—and its reach is so wide.

How wide? Well, ah, global. Trash, and plastic trash in particular (the worst kind!), may feel like a particularly American issue, but per Our World in Data the United States isn’t even in the top ten countries for per capita plastic waste per person per day; Kuwait leads that pack.

And there’s so much trash-related data out there, despite trash being gross and something we tend to want to forget about, that the storytelling possibilities offered by trash (data) are really rich. Again from the inimitable Our World in Data, another figure. This chart, as its title handily confirms, shows the share of plastic waste that makes it to the ocean, by country, in 2019.

But really, much of why I’m thinking about writing about trash in a sustained, ahem, book, ahem, way is because of the people. Per BLS data, nearly 500,000 people work in waste management in the United States (an industry with a market size in the tens to hundreds of billions), and I can’t help but wondering what their stories are. And not just the folks driving trash trucks, but everyone else working in their recondite and quasi-hidden—either by design or by quiet societal agreement—industry.

So to close, here are two images from a series of photographs by Shann Thomas that were commissioned by the city of Seattle.

“Barry Scheeler: Smooth Operator, South Transfer Station”

And here’s another, more representative of the portraiture in the series.

“Rosa Leifi, Disposal Crew Chief, South Transfer Station”

...

Header photograph of Seattle’s South Transfer Station taken by yours truly. Other photographs by Shann Thomas via the Seattle Public Utilities 1% for Art Portable Works Collection.

Here’s the etymology of “trash”; its origins might be in the Old Norse tros for “rubbish, fallen leaves and twigs.”

Now here’s an apropos Modest Mouse song.

youtube

0 notes

Text

Ars Poetica

Noah Eli Gordon, 1975-2022

Briefly: I was shocked to hear of the sudden death of the poet Noah Eli Gordon recently. He was so young, and was by all accounts vibrant. His death is a real loss.

Though I haven’t closely followed his work in a while, NEG’s poetry loomed large while I was in graduate school, back when I was keenly interested in the prose poem. I have a well-worn copy of his Novel Pictorial Noise lying around somewhere, and used the video below of NEG and Joshua Marie Wilkinson reading from their 2007 book Figures for a Darkroom Voice in many, many classes since I first came across it.

youtube

A comfort, I suppose, is that NEG’s art will live on; that art outlasts artists is part of what makes it worth making, and is an argument for engaging in individual forms of creation (i.e., writing poetry) vs. group work, like say building a bridge, even if individual creation is often impossibly difficult. But that doesn’t make losing artists any easier.

At any rate, here’s NEG + a crowd of fellow poets reading from his book The Source. Requiescat in pace.

youtube

...

Header screenshot via this video of NEG reading “A New Hymn to the Old Night” from his book A Fiddle Pulled from the Throat of a Sparrow.

0 notes

Text

Women of the World / Take Over

If the Supreme Court’s unbelievable decision to overturn Roe vs. Wade has a silver lining—and really, I’ve been looking for one, failing mostly, but looking—it’s that it’s reminded me of the Jim O’Rourke song “Prelude To 110 Or 120 / Women Of The World,” from his 1999 album Eureka (”Women of the World” is actually a cover, but more on that later). Eureka is a spectacular album that I should listen to more often.

The record’s opening track, “Women of the World” is a fantastic, understated song that begins with a folksy picked guitar before the strings arrive and then O’Rourke starts singing, in his quiet voice, as soft as a blanket, “Women of the world / take over / because if you don’t / the world / will come to an end / and it won’t take long.” Those lines, and only those lines, are repeated many times across the song’s 8-minute-plus playing time, which is just fine (O’Rourke does harmonize with himself). The song doesn’t need more than those lines. They’re true. Here goes:

youtube

As mentioned, O’Rourke’s version of “Women of the World” is a cover: the song originally appeared on Ivor Cutler and Linda Hirst’s 1983 record Privilege. Their song is remarkably different from O’Rourke’s version, and not just because Cutler is an Irish vocalist and opera singer: their version is much more dour, and includes the spoken word line “men have had their shot / and look at where we’ve got.” Which again, is true.

And sure, maybe I prefer O’Rourke’s version of the song, but maybe Cutler and Hirst’s more, ah, straightforward and serious version, with its minimal organ instrumentation, is more appropriate for the time we’re living through. We haven’t got long.

youtube

...

Header image taken by yours truly; it’s a sign someone left at City Hall after the protests in Philadelphia on Friday

0 notes

Text

(Back to) The Well

I recently published a review of Matmos’s latest record, Regards / Ukłony dla Bogusław Schaeffer, in The Quietus and it didn’t strike me until I’d written the article that I’ve now published four pieces about Drew Daniel and Martin C. Schmidt’s music.

To wit: so far I’ve reviewed Matmos’s 2019 album Plastic Anniversary, wrote about their enormous 2020 record The Consuming Flame on this blog, and I interviewed Drew Daniel about his 2020 solo/The Soft Pink Truth album Shall We Go On Sinning So That Grace May Increase?

How I became something of a Matmos (and I guess avant-garde-adjacent electronic music?) specialist is simultaneously bewildering and unsurprising. Unsurprising, because I’ve long had a proclivity to, once I discover an artist I like, dig into everything they’ve ever made.

Matmos is hardly the first artist I’ve done this with, nor is my “well, I like this one thing, so why not try EVERYthing” behavior restricted to music. A generous view of this tendency is that I’m a curious completist who focuses on the work of specific artists because the more of their work I’m exposed to, the better I understand their craft. An ungenerous view would be that I’m a bit of a wimp when it comes to new things and/or that I’m incurious. It’s probably both!

Anyhow, here’s a bit from the new review:

Regardless of their sonic inspirations, Matmos records always sound like Matmos records. Which isn’t a criticism of Regards as it is a feature of Matmos’s work. The polyrhythms, the blips and the bloops, and the droning string-like sounds that aren’t strings but instead are Matmos playing with objects and effects , they’re all there. And Regards/Ukłony dla Bogusław Schaeffer unfolds like previous Matmos albums, insofar as its first half is more fun than its second. Matmos records can be seen as a reverse mullet: party up front, business in the rear.

The new record is very good, and weirdly fun in the specific way Matmos records are weirdly fun. It also ends with a suite of highly ambient music that is similar to how Plastic Anniversaryclosed, with wind and water and the world; Regards is, to my ear at least, Matmos’s most abstract album yet.

To close, here’s “Flashcube Fog Wares,” one of the more abstract (and noise music-y) tracks on the album.

youtube

...

Header image via Wikimedia Commons.

0 notes

Text

Ideas of Others

Color me both frustrated and unsurprised: a few days ago, The New Yorker published a long interview with one of my very favorite people on earth, Werner Herzog. This being the New Yorker, and this being Herzog, the article was of course required reading, and I may or may not have yelped with pleasure when I first saw the link. But then I started to read it, and this humdinger of a sentence was...the second sentence in the piece:

During quarantine, he finished two films: a documentary called “The Fire Within: A Requiem for Katia and Maurice Krafft,” about a pair of French volcanologists; and another, “Theater of Thought,” about neurotechnology and artificial intelligence. Both are forthcoming.

Why, you might ask, would this frustrate me? Well, and I’ve written about this before, my getting-there-but-still-not-done book about surviving suicide includes a chapter about none other than...Katia and Maurice Krafft. So it’s frustrating to hear that Werner Herzog of all people—the guy who made Fitzcarraldo and Grizzly Man and Happy People, among so many others!—and a dude whose work I **quote in said as-yet-unpublished-but-finished chapter** is making a film about the Kraffts. Sigh! I knew I should have finished this thing earlier.*

Then again, running into others with similar ideas should hardly be new for any artist—the sometimes (frequently?) false lure of originality is as much a part of artistic production as is rejection.**

So why should finding out that one’s ideas might not be as original as one thought sting, sorta? Aside, of course, from our innate desire to be special?

The eighteenth century British poet and writer Edward Young, in his (admittedly wordy, but it was written in the 1750s, so c’mon) “Conjectures on Original Composition,” might have an answer why:

Originals are, and ought to be, great favorites, for they are great benefactors; they extend the republic of letters, and add a new province to its dominion: imitators only give us a sort duplicate of what we had, possibly much better, before; increasing the mere drug of books, while all that makes them valuable, knowledge and genius, are at a stand. The pen of an original writer, like Armida’s wand, out of a barren waste calls a blooming spring: out of that blooming spring an imitator is a transplanter of laurels, which sometimes die on removal, always languish in foreign soil.

To which I can only respond with a nod, a shrug, and an image of perhaps the most famous tortured-artist print, Durer’s Melencolia I.

...

*Not that my not publishing my work before Herzog’s film comes out really matters, because my work is hardly in competition with Herzog’s (ha!). But the point re: frustration re: “I did it first, ugh, man!” stands.

**And really, how much art is produced alone? Sure, in the silence of one’s mind, it happens alone there, but it takes a village to publish any book, or exhibit and publicize and sell any work of art, et cetera. “No man is an island entire of itself; every man / is a piece of a continent, a part of the main.”

...

Thanks to Wikimedia for the amazing picture of Herzog et al. (come for Herzog, stay for Donald Sutherland and Brad Dourif‘s hair) posing during the press tour for the poorly received 1991 film Scream of Stone, which is “about a climbing expedition on Cerro Torre.”

Here’s the trailer. It’s dramatic!

youtube

Melencolia I image via the Met.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lives of Others

There are a few lines from Jorie Graham’s poem “Nearing Dawn” (from her 2008 collection Sea Change) that have been going through my head, quasi-accurately of course, for the better part of a decade.*

Here they are, emphasis mine. I’ve replicated the breaks as faithfully as possible:

great sands behind there, the pharaohs, the millennia of carefully prepared and buried

bodies, the ceremony and the weeping for them, all

back there, lamentations, libations, earth full of bodies everywhere, our bodies,

some still full of incense, & the sweet burnt

offerings, & the still-rising festival out-cryings—& we will

inherit

from it all

nothing—& our ships will still go,

I’ve been thinking about these lines lately for a number of reasons, mostly because an old friend recently experienced a terrible loss. But also because it’s now April, and therefore almost the thirteenth (!) anniversary of my mother’s death. I first read Sea Change shortly before my mom died, and the idea of the earth being “full of bodies everywhere” particularly struck me then, as it’d become obvious her illness would soon run its course.

The thing is, Graham’s lines are entirely accurate—over the entire course of human history, far more people have died than are currently alive. Indeed, according to the Population Reference Bureau “about 117 billion members of our species have ever been born on Earth”; the current world population is somewhere around 8 billion.

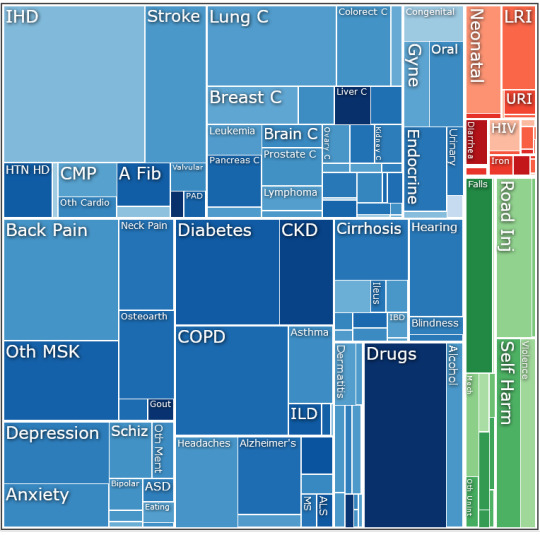

This is both grim—the world really is filled with the dead; the world is more the dead’s than it is the living’s—and unbelievable, given how complicated and rich the interior of one’s life generally seems. And it’s not like understanding the living, and what ails them (below is a figure showing causes of disability-adjusted life years in the US in 2019) is easy.

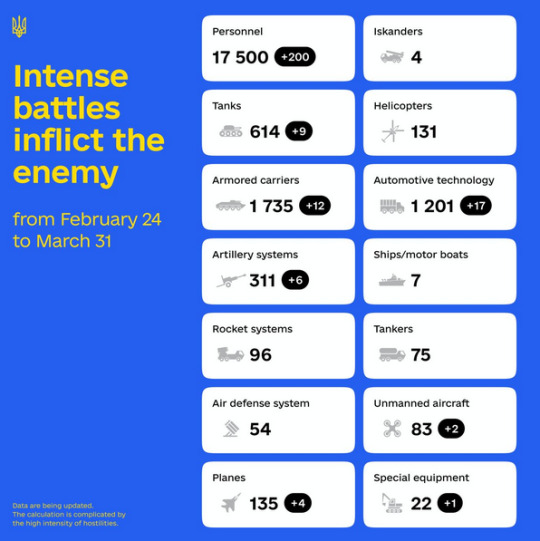

For a more timely example of “numbers and life and boggling complexity and thinking of the dead is weird, whoa,” here’s the March 31 update on Russian troop and equipment losses from the Kyiv Post (via Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense).

Though these numbers may well be inflated—the Russian casualty figures published by the US and NATO are markedly lower—the point makes itself. Even inflated, these are astounding numbers for a weeks-old war, and for the violence and stories they imply; for example, many tanks have a crew of three; when tank crews are killed, they’re often killed in terrifically violent ways, by shrapnel and explosive shock waves and fire.

So what is one to do with these competing, or at least jostling, ways of seeing the world? I don’t know that there’s a good answer, because living often entails holding jostling things in one’s head simultaneously. Perhaps Mother Teresa’s way of looking at it—”If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.”—is a sound approach.

Anyhow, here’s some more poetry, from Ashbery’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror”:

Tomorrow is easy, but today is uncharted.

Desolate, reluctant as any landscape

To yield what are laws of perspective

After all only to the painter’s deep

Mistrust, a weak instrument though

Necessary. Of course some things

Are possible, it knows, but it doesn’t know

Which ones. Some day we will try

To do as many things as are possible

And perhaps we shall succeed at a handful

Of them, but this will not have anything

To do with what is promised today, our

Landscape sweeping out from us to disappear

On the horizon.

...

*To put “highbrow poetry going through one’s head for years and years” in perspective, I’ve also had the A-Team theme song in my head since my early twenties. Dun dun dun, dun dah dun dun dun.

youtube

Header image, “L’Intrigue” by James Ensor, 1890, oil on canvas, via Wikimedia Commons. Treemap image via GBD Compare. Russian losses image via Twitter. Mother Teresa quote via the The New Yorker article I read yesterday (thanks, TNY!)

4 notes

·

View notes