Text

Untitled by Linda Lee

A family of six sits huddled in the waiting room, the dim fluorescent lights above them flickering on and off, on and off. The clock on the wall indicates that they have been waiting for four hours now. Their mother is in the surgery room, and her life is in the latex gloved-hands of surgeons crowding around her.

A young woman with tangled hair leans against the counter of the receptionist. Her eyes frantically fly over a stark white document, her pen shaking over the health insurance section. She glances back at her three-year-old son who pauses between heaving coughs to smile in her direction. The receptionist stares at the woman over her glasses and motions to the clipboard impatiently.

At the same time, a clean-cut older man sits in his office. The furniture is well-polished, and his oak desk remains spotless, save for a plain folder in the center. It’s the monthly report from one of the hospitals under his management. With an annoyed sigh, he glares at the low figures and the sharply descending slope of the hospital’s share values. He presses a button on the phone on his desk and utters a terse order. No more costly procedures, and simpler cases that involve prescription medication. Increase the revenue without any drastic increases in cost.

This is the dichotomy that surrounds healthcare. The mission to save lives and improve the well-being of the community is held back by the profit-model and the focus to create a successful business. When human lives are mixed with corporate greed, we start to lose the focus on what healthcare truly means. Patients are not commodities with increasing or decreasing value. Every life weighs the same, whether it’s a child coming in with a cold or a grandfather with terminal cancer.

Who are we to attach a price tag on life? How has it become the norm to turn away those in need? In order to continue, healthcare must be equipped with a sustainable business model as it is necessary for the sake of the field. However, this mentality has begun to corrupt the primary purpose of medicine, and business is threatening to take greater precedence over sustaining life. Before anything else, healthcare is a service, and its identity as a service of helping others is what separates the field from any other corporate institution.

As aspiring doctors, pharmacists, surgeons, nurses, and other future devotees to the industry, we must not lose this identity that connects us. We must not forget the first and foremost mission of healthcare even when bogged down with the logistics and finances of working for a hospital. A doctor or nurse is often the first impression that a patient’s family encounters when entering a hospital, and our faces can be who they depend on for help. More than simply treating a patient, those in healthcare have a responsibility to uphold their hospital’s mission and reassure the pained hearts of the families of patients. This is why we are more than a business. This is what it means to serve others.

Every patient file, every prescription, and every discharge has a story. The cumbersome paperwork accompanying each discharge is a happy ending of a healthy patient, a relieved family, and a better life. The file objectively stating biographical information and physical data may be a patient who resisted going to the hospital because he did not want to burden his family with the medical bills. We cannot understand the scope of every patient’s circumstances, so we must do the next best thing. We must help them all we can and always remember why we choose to follow this field.

0 notes

Text

“Reading Medical Memoirs: A Personal Essay About My Thesis” by Jon Galla

This past year, I wrote my senior thesis about medical memoirs. Despite its academic intention, the topic came out of a largely personal question that has plagued me since I began my pursuit toward medicine: what does it mean to write about other people, and why do we choose to read stories that display moments of vulnerability and intimacy? Let me tell you a story:

The genesis of this question starts from my own perspective as a premedical student in a humanities concentration. I would often find myself in conversation with an unwitting friend or stranger who would ask me about many of the physician-writers of our time: Atul Gawande, Oliver Sacks, Abraham Verghese, the list is never-ending. I did not know how to respond to these bizarre requests. Of course, I would give a smile and a nod. Sometimes I would even add a brief, yet hopelessly vague interjection on the matter at hand. “I love him! Especially when he talks about the old man with a heart attack.” Replace ‘heart attack’ with ‘Parkinson’s’ for Sacks; ‘Parkinson’s’ with ‘AIDS’ for Verghese. Author Unknown? ‘Cancer.’

Upon coming up with this formula, I realized that there was something rather common to these narratives. We read about other people out of curiosity, and perhaps, illness arouses a curiosity within us that goes beyond the everyday. Though we may focus on the stories of those affected by illness, what happens on the other side? When you think about it, it seems strange to think that one profession would have such an allure but not others. Rarely do we see best-selling memoirs of other professions gain such prominence. This manifests in other ways too. Turn on your TV, and you will be hard-pressed not to find a medical drama broadcast in the next few hours. Grey’s Anatomy, Code Black, ER. Alarms go on and off, and medical personnel fly through hallways and dark, crowded rooms illuminated by the blue light of a monitor as a code is called. I never understood why on television, medicine happens in a dark room filled with adrenaline--the perfect setting for a needle stick, or another simple mistake.

Yet I am not alone in this deep seated suspicion of medical dramas. My mother is the perfect example of this. An avid fan of Grey’s Anatomy, she is enthralled by the chaos and emotion on screen. “Obviously this is fake,” she always says to me. “That doesn’t mean it isn’t fun to watch.” We turn to the classic dilemma of the arts. For some people, art becomes life. But for others, life becomes art. The quest for realism is at the center of almost all medical memoirs and related works that I read for my thesis, and the consequences for this realism was the path I followed in my research. But for a moment, I will make space for what that realism is, and what it means to me.

~

“What is it really like to be a doctor?” I said to myself, flipping through the pages of Being Mortal.

“Am I going to think this way in 10 years? Am I going to lose a part of myself?”

~

Realism is present in the moments when the narrative does not run as expected. Realism is what haunts us when we read about the man who slowly loses his vision and has nothing to say, only tears. It is when we are faced with the painfully mundane.

Medical memoirs allow readers to embrace the realism absent in medical dramas. They allow us to take in the sorrow of a failing heart, the joy of delivering a baby, and more importantly, all the moments in between, hopelessly ambiguous and void of a higher meaning. Thinking back to my mother, I wonder how she could compare medical memoirs to medical dramas and what purpose each serves.

As realism takes hold, we find ourselves reading about actual people. These are the questions that had animated me for the past year. Why would we choose to read and write about those who are vulnerable? Whose stories deserve to be told, and whose deserve to be protected from public knowledge? There are no simple answers. Reading the works of gifted physician-writers, I realized that many of these authors felt uncomfortable about how they shared their patients’ stories. Anything but lightly made, the decision to write about actual, vulnerable people reflects a higher cause of which an exposure of privacy is a risk worth taking.

Reflecting back on my work, I wonder what holds for my own vulnerability and how I share it. Writing this very essay provoked a process of self-reflection that I had not engaged with in a long time. I do not know who I will be in five or ten years, let alone whom I will care for. Will I feel differently about people’s right to feel represented and understood? Or will I become one of the very people I criticize, writing to the public about “interesting cases” with greater resemblance to a freak-show than an educational opportunity? We must make our own choices, vulnerable or not.

0 notes

Text

"Starry Night” by Evelyn Wong

To tread the last step of the four-mile hike toward Mount Hollywood’s summit for the first time is truly surreal.

For many, it is an iconic feat—an item one would cross off on a bucket-list when visiting California as a tourist. For me, it is home. Below lies the city in which I was born and raised, preparing to blanket itself in the growing darkness; above, the same ornament-like stars that made their debut above Gatsby’s mansion.

Something about the tranquilizing view reminds me of Gatsby’s endeavor to reach his dreams, compelling me to acknowledge my own. Closing my eyes, I imagine the night sky as a living, breathing character in a Hemingway novel, with deep hues of blue swirling through a sea of black—and yet lighter blues racing through the scene with the swooshing sound of the winds. The stars shone brightly, searing cracks in the seemingly indestructible atmosphere, allowing us to admire their immeasurable beauty.

It is in these moments when I dream of having conversations with the great artist Vincent van Gogh on the rue du Palais, listening to the master himself describe the blues and violets and greens of the night sky. Luminous surfaces are pulsating with the liveliness of interior light, seeing his brushstrokes of Cafe Terrace at Night vibrating with the same sense of excitement that he experienced while creating his works.

I would imagine his words as his brushstrokes raced across the canvas: “There’s so much more to this world than the average eye is allowed to see,” he would say, as the directors of “Doctor Who” envisioned. “I believe, if you look hard, there are more wonders in this universe than you could have ever dreamt of.”

Walking through Harvard College as a student for the first time, I often wonder which of my peers would soon become the next Van Gogh or Galileo.

Why is there such a negative connotation to the labels “crazy,” “strange” and “misunderstood”? I believe that “insanity” is the name often given to those who attempt to be rational in an insane world. After all, who determines what sanity is, anyhow?

Taking Metros to Downtown Los Angeles in my hometown, many of those whom I have grown up with are often intimidated by those we label “severely disabled” or “mentally handicapped.” We don’t think twice about their situation—in the long rides along the Gold or Green Lines viewing these individuals from behind glass barriers, we never imagine life through their eyes.

What would we think if we realized that they’ve seen the same images in the starry night sky as Van Gogh did from his asylum room at Saint-Remy-de-Provence?

Many often forget that individuals with “different” views are humans, too--as social beings, we tend to ostracize those who do not think or act like everybody else. It is easy to forget that within the shadows of Harvard College live those who are mentally afflicted, afraid to make themselves known for fear of being left out. Unless the challenge of dealing with mental illness directly affects us, our own family members, friends and peers, the plight of those who struggle to make their sanity known in a “mad world” seems utterly unreal. Only when our parents and grandparents are afflicted with depression or conditions such as schizophrenia and dementia do we repeatedly tell ourselves that the ones who raised us couldn’t possibly be insane.

But the demons that afflict them are the same fiends that terrorize the men, women and children on the streets—not only in Los Angeles but in Cambridge and around the world. The only difference may be that those we scorn are the ones who don’t have a home to return to.

Our school community stigmatizes mental health as well—in the shadows of Harvard lie the faces struggling to conform, wishing they wouldn’t be exposed for fear that they would be perceived as crazy.

Not all of these shadows are invoked with hallucinations or the stigma often attached to what we call “mental health issues”; they simply see the world differently from the rest of us—and if we took the time to walk around in their skin for a while, we’d realize that there’s a Van Gogh in every one of us.

Starry Night, along with the great works of the Impressionist and Surrealist artists, helped me realize that the visions that often plague our minds with uncertainty and discomfort aren’t insanity—for many, many individuals, those dreamlike images with melting clocks and distorted figures are very much a reality.

And though they may be different, each of our minds is just as beautiful as any other. Label me a hopeless romantic, but I’m waiting for the moment when one of the shadows of Harvard Yard or Widener Library wins a Nobel Peace Prize for quantifying turbulence, or being globally recognized for creating the next artistic masterpiece.

0 notes

Text

“Take it on faith” by Rory Sullivan

One hundred years ago we didn’t know about DNA knew only

that somehow life creates itself anew meeting different eyes

across generations imagine not knowing how you were built

Transcription Translation occurring regardless needing no

conscious approval heeding no questions every cell a test tube

full of mystery and perhaps divine intervention to keep the species

alive to struggle and write and learn of what molecules we are made

0 notes

Text

“Intrinsic Contingency Plan” by Rory Sullivan

This is a story about sacrifice,

The wounded body recognizing not-self

The necessity of defense against invaders

From the outside world

In the time of a blink,

Receptors bind chemokines,

Call neutrophils from the blood –

The most noble of cellular warriors.

So fervent in battle that they consume enemies whole,

Though in the frenzy the heroic neutrophil too must lay down

His sword to preserve the veined, thumping integrity of life

Leaving lacerated skin weeping cellular debris in solidarity

The valiant neutrophil has not parted with life in vain –

When the infection has passed, the body is whole again.

0 notes

Text

“Hippocrates” by Rory Sullivan

Hippocrates said the body is at the juncture of four rivers,

Multi-colored fluids endowing hot and cold, wet and dry

Hippocrates said that each body has its own unique temperament,

When the body falls ill it needs only to have the rivers realigned,

Flowing fresh and true under the skin

The physician purges polluted blood and bile,

And by the arts of his hands earns fame in the eyes of the gods

0 notes

Text

Narravitas: Volume 2 (2018)

We are pleased to present our second volume of work! Our published authors have a wonderful selection of poetry, personal narrative, essays.

We have a personal essay on thesis writing by Jon Galla, an opinion essay on profit and humanism by Linda Lee, a creative narrative about the connection between art and mental health by Evelyn Wong, and three poems on the beauty inherent to medicine and science by Rory Sullivan.

Thank you everyone for another wonderful year and volume of published work. We will post updates about future directions later this summer.

0 notes

Text

Join Narravitas!

Interested in health and medicine? Ever wanted to explore medicine from the perspective of storytelling and writing? Then join or write for Narravitas! Our first issue was published over the summer, here, on Tumblr!

Please fill out our general interest form by Wednesday, September 27. We are excited to meet our new writers and editors!

0 notes

Text

Finding Susan Sontag: Her Work, Metaphors, and Legacy; by Jonathan Galla

When I began thinking about how to write around the idea of Narrative Medicine, I couldn’t help but turn back to what brought me here: to this field of illness, of narratives, of where the disease meets the written page as easily as it meets the patient’s body. I immediately thought of Susan Sontag, that tour de force writer-critic who redefined how we think about the mythologies of illness. In finding Susan Sontag, we see how life and literature do not have simple barriers. This essay explores how narrative medicine has grown from its initial understandings, through the lens of one of its prolific inspirations, and the legacy of her writing and activism.

*

Perhaps, a proper introduction to the practice of narrative medicine comes not from a clinician, or a student, but an outsider: one who does not have intimacy with the medical system or its hierarchies, a person who instead captures the experience of illness itself. Thus, I introduce Susan Sontag, author of Illness as Metaphor, “The Way We Live Now,” and many other groundbreaking texts on the relationship between illness, language, and experience. She was not just a writer, but also a figure who has heavily influenced activism and medical practice after her death. A truly international figure, she wrote not only in the US, but dabbled considerably in Parisian intellectual circles and was widely read and translated around the world. As an activist, Sontag spent a significant time writing and practicing her activism in Sarajevo, where she directed a production of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot amid the constant threat of snipers during the civil war (1). Certainly, one could point to the many aspects of her legacy in the present humanities, but one that has often gone overlooked is how she challenged our understandings of illness through her own experiences: most notably, that of cancer.

Cancer was no stranger to Sontag: she was diagnosed once in the 1970s and again in the early 2000s, culminating in a ruthless struggle that took her life (2). This journey, as individualized as it was in her suffering, was one she ultimately chose to share. Her partner, the famous photographer Annie Leibovitz, graphically documented the final moments of her battle with cancer. One can easily find the images online, if not in her large folio-sized autobiographical photobook: Annie Leibovitz, A Photographer’s Life, 1990-2005. I leave you not with the ominous images themselves, but their resonances: just as Sontag famously wrote On Photography without images, so illness transcends the written page, the photograph, or any medium that circumscribes its wrath.

Pre-cancer shot: Susan is lying comfortably on a sofa in their long island house, looking in health with black hair and an intense stare.

Shot one: her long hair with the signature white lock is gone; in place is a jet-white barber’s cut.

Shot two: bedridden, Susan is loaded from the tarmac onto a charter plane headed for New York, her final resting place.

Final shot: a handsewn panorama of the no longer living. She is laid out next to the hearth, arms folded but the marks of a violent death left untouched. Her arms are bruised, and the body looks cold and pale in the light. No one is left untouched by death, the photograph whispers with its art of intimation.

To those familiar with Sontag’s work, her choice to allow these images to proliferate bear no discrepancy with her life’s work to understand, document, and humanize pain. As a public intellectual, she sought to bring the common experience of illness into critical or literary analysis, most notably in her book Illness as Metaphor, published shortly after her first bout of breast cancer. In Illness as Metaphor, Sontag describes the intimate connection between illness and everyday language. Sontag writes of the banality of comparison everyday life to the disease, slowly losing its weight in the imagination with overuse and misapplication. Most importantly, she described not the experience of illness--an experience we all come to know--but how illness metaphors have been appropriated into society: the ‘cancers on our society,’ the ‘plague’ of annoyances. She wrote, “My subject is not physical illness itself but the uses of illness as a figure or metaphor. My point is that illness is not a metaphor, and that the most truthful way of regarding illness—and the healthiest way of being ill—is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking” (3). For Sontag, metaphoric thinking is not the antidote, but the very poison to experience.

What Sontag ultimately argued was that disease, as metaphor, inherently takes on a moral context through its equivocations. The phenomenon she traces is not only a moral dilemma, but harmful to how illness is interpreted and understood. Indeed, humanity has a capacity to trace illness with superstition, from the ‘miraculous starvation’ of female saints in the middle ages to relatively recent hypothesis of a ‘cancer-prone’ personality. Yet this appropriation of the illness metaphor weakens the gravitas of illness experiences, depriving them of their proper significance at best, stigmatizing and demeaning the ill at worst. These ‘ills of society,’ rather than defining social problems, cast judgment on those individuals who are ill, leaving greater questions unresolved.

Sontag’s line of thinking has started a legacy in how we think about disease and its languages. When someone is ‘battling’ cancer, why do we use that word, and what are the implications of the exchange in meaning between disease and war? Certainly, when one ‘loses’ their battle against a disease, it is hard not to wonder if those who won have any superiority, be it due to their genetic hand of cards or biological chance, or something more sinister: their ability to pay for the latest and greatest life-extending treatment, the environmental variables (read: pollution, geography, living in the ‘right’ neighborhood) that lead to the disease being a worse.

Of course, the debate continues, and still I have no answer as to why someone ‘loses’ and another ‘wins,’ dichotomies notwithstanding. But medicine is not about winning or losing--it’s about healing, the easing of the body and spirit. When metaphor dances a dangerous dance with illness, morality soon creeps into the picture. Without an impartiality of language, nobody wins from the inequity that follows.

*

Today, Narrative Medicine (capitalization intended) does not exist merely as an edgy experiment by writers like Sontag, nor is it a rebellion against the medical establishment, psychiatric institutions, or the common past suspects of indignity of the medical system. It is an everyday approach to best understanding a patient’s chief complaint, an economic alternative to the standardization of charts, Electronic Medical Records, and the endless quantification of the patient’s condition.

Are we returning to the past? An era in which a country doc writes out notes in a dusty workbook and pulls an aspirin out of a mason jar? Not quite. Comical as it could be, narrative medicine exists in a contemporary field of medicine, and importantly, a contemporary understanding of what narratives are--how they exert themselves not only in the medical world, but also our lives and society more broadly. As a future physician, I constantly ask myself what kind of doctor I hope I will become, and who else will work around me. In essence, this marriage of medicine and narratology seeks to acknowledge the limits of diagnostic tools: the chart, the physical exam, the narrative of illness.

Sontag left an indelible impression on the field, and indeed, there is something to be said for how clinicians and researchers think about language in their practice. What does it mean to understand someone’s story when their language is not the same as your own, coming through the translation of an interpreter? What if someone lacks the knowledge base to use that very language? How do clinicians work with marginalized communities to not only aid their understanding, but empower community health by acknowledging their language and narratives? Narrative Medicine, in its wide reaching arc across disciplines, certainly has learned and continues to learn from the ability of language to mediate and transform our understanding of disease, care, and the human condition.

Burns, John. “To Sarajevo, Writer Brings Good Will and ‘Godot.’” The New York Times. August 19, 1993.

Wasserman, Steve. “Author Susan Sontag Dies.” Los Angeles Times. December 28, 2004.

Sontag, Susan. “Illness as Metaphor.” The New York Review of Books. Jan 26. 1978.

0 notes

Text

"Invasion” by Aurora Sullivan

Sometimes the strands snap leaving us at loose ends

Sometimes it can’t be fixed

Sometimes the cell keeps dividing without realizing there’s something missing

Lacking one miniscule piece of origami

The cell stops picking up anybody’s telephone calls

It pursues immortality

By giving birth to endless identical daughters

Each generation a little more deranged

They colonize,

Grow their own veins,

Sew and reap corruption

It will take a war to see them overthrown,

To redraw the borders and limits,

To bring order to the chaos left behind

0 notes

Text

“Heredity” by Aurora Sullivan

Every moment, we triumph over

The inevitability of decay, feeling life as circular,

Frenetic chromatin winding and unwinding

Generating the pieces of what we think of as ourselves

We are clumps of atoms colliding,

Tottering through improbable into factual

Carefully, according to genetic blueprint

Assembled by glorious profusion of cellular apparatus

We announce ourselves eukaryotic with novel

Temerity and confounding complexities,

Capable of building skyscrapers but never

Given to stop wondering why

0 notes

Text

Untitled Dialogue, by Ziyad Ziko McLean and Andre Sanchez

Physician:

We usher new life into the world

nurture the growth of little boys and girls

deliver the sick from death’s door to wholeness once more.

Even with all the good we bring forth

faith always takes control at the final door.

And tests our efforts forevermore.

Years and years have had their toil

and the kid in us would not recognize what stands before

because of the things we can’t do, the lives we can do nothing for.

To fulfill the recovery of the sick

is to sometimes take an occupation

as the messenger from death’s door.

Some illnesses you can’t stop,

you present the news to the family and their heart stops

And as you search for an answer in yourself you ask:

“But what am I good for?”

Patient:

I

have come to know

that my days are fleeting,

my flower weakens

as an immortal chill nears,

the fruit of life

now sour, far from ripe,

remains constantly out of my reach,

and yet

the flowers glow with a brighter hue,

my love grows with each day anew

knowing that I will soon be due,

And as my stem bends

I will return to the Earth

once again.

0 notes

Photo

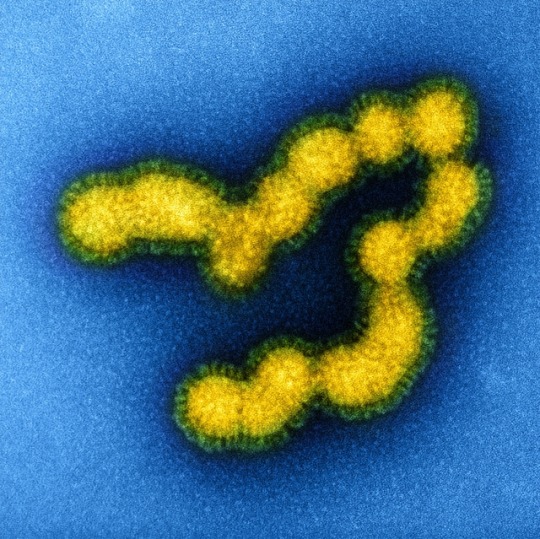

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of negatively stained SW31 (swine strain) influenza virus particles. Credit: NIAID

0 notes

Text

Gary Taylor, by Julie Ngauv

The first time I listened to Dr. Gary Taylor’s story was at a seminar on a sunny Monday morning in mid-July. He was seated with several other panelists, all from a variety of backgrounds; each bearing stories from their own journey with cancer. As they spoke, my heart grew heavy—there was a single common thread in every story: each panelist advised us as future physicians and researchers, imploring us to never forget to see a patient as a whole person, to never become jaded and lose sight of why we were pursuing these specific dreams.

The second time I listened to Dr. Taylor’s story was a Thursday evening in the midst of winter. We sat in a bustling Starbucks, and introduced ourselves to each other. He had a kind, smiling face; his voice compassionate and thoughtful. He was an internist and gerontologist specializing in addiction medicine, he told me, but “out of practice for nine years this month.” He had practiced medicine at Carney Hospital in Dorchester for 23 years, but had to stop to care for his wife in 2008, shortly after she was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. “I never quite made it back,” he explained, “it was the first time in my life that I wasn’t in school or working.”

A few years after his wife’s passing, in 2015, he decided to run the Boston Marathon—something he had done before and wanted to do again. In training for it, he decided that he might as well get a physical. His doctor performed a standard prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, which Dr. Taylor had been getting regularly “since his forties,” because his father had had prostate cancer. His levels of PSA had more than doubled—1.9 to 4.9. Thinking it was a fluke, the test was repeated a few more times, but the results remained stable. Dr. Taylor visited a urologist, who doubted that the results pointed to cancer, insisting on treating him for prostatitis instead—something he didn’t have. He tells the rest of his story without missing a beat, “We finally got around to doing a biopsy, and the biopsy showed that I not only had prostate cancer, but fairly aggressive prostate cancer.”

“Devastated,” is the one word that he would use to describe his reaction. “Absolutely devastated… It completely blew me away. I was convinced that the biopsies were going to be negative. I could not believe that they were positive, like—are you serious!? I really knew I was in for a fight.”

Cancer is just as much of an emotional battle as it is a physical one, and as with any battle, it cannot be fought alone. At first diagnosis, even a personal understanding of one’s own current condition is difficult to come to. Many times, patients struggle, searching for a specific cause, needing someone, something, anything to accept blame—sometimes even themselves.

“I remember I talked to an oncologist friend of mine, and I will never forget what she said. ‘Everybody gets something. It’s your chance to get sick. Why not? You’re human like everybody else… these things are going to happen if you live long enough.’” He valued the sentiment greatly. “She was right; a lot of people get cancer. Just because you’re a doctor doesn’t mean that you’re immune from things like that. But I really did become a doctor to live a better life, to really take better care of myself, so I felt like I had done a bad job in many ways… I still got cancer, but I knew that it wasn’t my fault. It was just one of those things.”

One of his biggest frustrations with prostate cancer was that there was no standard of care, and, so far, studies haven’t produced any conclusive evidence on which of four treatment options (surgery, radiation, hormonal, and the less-interventional choice of “watchful waiting,” in which a patient opts instead to consistently monitor the cancer for signs of progression) for prostate cancer is more preferable. “Prostate cancer is probably the type of cancer that requires the most in terms of education of the patient. You really have to be educated. You really have to know what you’re getting yourself into.” There was nothing close to adequate research available in aiding his decision.

Dr. Taylor is quite passionate about someday rectifying this—when I asked about the message he would most like to convey, he spoke again of research. Research was key, he insisted. Lack of sufficient research comparing different types of prostate cancer treatment made it necessary for him to get multiple opinions from various doctors, making it very difficult to decide on the steps that he would take going forward. He emphasized that this would most likely have made it impossible for the average person who lacked the medical connections that he had a physician. With this, and his experiences as a black man practicing medicine, he insisted that people—“especially African Americans!”—get involved as subjects of research studies. Elaborating, he said:

“Research has been a sore subject for us for many, many decades, and we’ve been treated like guinea pigs and disrespected. But now things are different… I would encourage people to get involved in research, because we need to find more answers about this. One of the reasons we know very little about it is because there’s not very good studies, and so we need more people to be available to do that. I must tell you, that’s a different view than what I had when I was a doctor. I truly felt that African Americans in particular should not be involved in research, because I felt like we were subjected to things that we perhaps shouldn’t have been, and the care was worse, you know, in many ways… but that’s just not true anymore. Everything is now standardized; you get baseline labs and everything, and you actually see more providers when you’re [in a study] than when you’re not… I think it’s something people should do, rather than look at other types of medicine like alternative care.”

For the African American community in particular, as Dr. Taylor stressed, research became synonymous with abuse, lack of rights, and pain—well-known cases include Henrietta Lacks’s immortalized cell line (she gave no consent to have her cells used for scientific research), and the sickeningly unethical Tuskegee syphilis experiment, though there are undoubtedly many more.

The first time I heard Dr. Taylor speak, I recall sitting, my pencil hovering above my notebook, wanting to write something of substance down, but hesitating. What could I write to capture these people’s stories? I wrote a few bullet points:

importance of hope

empathy, sensitivity, cultural understanding

The words I carried from that day were different—these lives were filled with the unfathomable, days to which “walking a mile in their shoes” could never be applied. The story of a doctor being diagnosed with cancer was something that struck me most. Somehow, it captured a bitter tinge of irony. That day felt so far away when I sat down to hear his story again; this time asking him questions instead of being a passive listener in an audience of researchers. I had brought the very same notebook, this time carefully turned and folded to a page of questions, and a clean page upon which to write his answers.

I asked him the question that had remained in my mind all of those months: “You mentioned in the panel that you had to come to terms with being in a patient’s role instead of being in a doctor’s. Can you speak to that?” He nodded, conceding the lessons he learned from his time in a patient’s shoes, ones that he came to realize could be filled by anyone, really. He talked about being a physician, being the one to make decisions, then about being a patient, having to trust, rely, and listen. “It was tough, you know, because I knew the language… so I knew what they were saying, so I really had to try to refrain from going to the library and looking stuff up. I didn’t do that very well.” In a more reflective tone, he continued, “You know, I’m not sure that’s the best way to do things… I’m a doctor, but I can’t become a cancer specialist specializing in prostate cancer overnight, nor can I do it in a year or two.”

Still, he returned to the library day after day—researching every single thing his doctors mentioned, even when he was meant to be researching other topics. He continued challenging them and asking question after question. It was difficult to adjust to the change of not being in control, he explained. A doctor’s job is difficult because she has to lead, to decide. A patient’s job is difficult because he has to trust. “They knew more than I did, and they were going do the right thing.”

Although his diagnosis devastated him, he didn’t let it defeat him. “I thought I was too young… [though] I was determined to beat it, if I could.” He spent a few months gathering opinions from his colleagues through the Boston area, and finally decided to undergo a radical prostatectomy, undertaken by a friend of his who was a surgeon. It was a difficult experience, but one that he felt was necessary, and one that he eventually recovered from. The surgery was successful.

Eight months later, in June of 2016, he experienced a “chemical relapse.” Just like in the initial test that led to his diagnosis, his PSA levels had increased to a concerning amount—which should not have been the case following the removal of his prostate. This “indicated that there was residual disease somewhere,” causing him to need to undergo both radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Over the course of his treatment, he spent a lot of time in and around hospitals—something he was already accustomed to from his training and during his time in practice, but now his experiences were different. “Hospitals are very cold… I don’t know, I felt like a fly in soup.” He often didn’t tell hospital staff that he was a physician—this caused his comments on his own care to elicit incredulous reactions. “Some people were taken aback by it… people would look at me like I had 12 heads, like ‘What are you doing, trying to tell me my business?’ and stuff like that.” Trying to avoid the sensation of being “a number… just one more person to see,” Dr. Taylor chose to pursue his care at local hospitals.

“I felt more at home there. They’re different hospitals with different goals, and I appreciate the homeyness of the community hospital. I felt like I was getting good care. When I went to the bigger hospitals, I felt lost. I felt like I was just a cog in the wheel. I mean, there’s a lot more layers of healthcare in the larger hospitals… Some people like that, I’m just not one of them. I just like the more hands-on experience of having a doctor, and an NP or PA that I can really sit down and talk to.” His friends were critical of his choice, urging him to go instead to Mass General or Brigham and Women’s. “They were really upset with me; that I didn’t do that. The doctor that I went to—he trained at the Brigham, he’s a very good doctor, and I know that doctors in the community tend to see more, sometimes, than doctors at big hospitals, so that’s why I went that route… [though] I did get second opinions at the big hospitals. I definitely went and got second opinions.”

Being so distinctly in a patient’s shoes is not an experience doctors often encounter. Of course, everyone has their basic annual physicals, but really living the reverse of the patient-doctor relationship—filling the patient’s shoes—is something that is not often encountered. What could possibly be learned by such an experience? Humility, Dr. Taylor insisted. “I’m a lot humbler than I’ve ever been before, that’s for sure. I think I have a new understanding of the patient-doctor relationship.” The importance of listening, of reading between the lines. “It’s amazing how little things really help—how important it is to listen. I’ve always had a good relationship with my patients—I thought I did, but I’m a lot more aware of things. I’m a lot more aware of things people don’t say. I lean into things a lot more. I think I’m more compassionate.”

It’s all too easy, as physicians, to become jaded and view patients solely as conditions to be solved, to be healed, and then to be released—not people. These sentiments echoed the words that I had heard from the other panelists that morning long ago, but in a different perspective—this was the perspective of someone who had lived both ends of the same interaction. Someone who knew how simple it was for one to assume one knew everything, but whom also experienced the receiving end of that arrogant and knowing look. “I’m less cocky than I was before—when I was a young doctor, I just thought that I knew everything... Now, the older I get, the more I realize that I know very little… So it’s important to really understand—there’s still a lot that’s not known.”

Words have power, both in interactions, and as descriptors. Dr. Taylor chooses not to refer to himself as a cancer survivor. “I’m not so sure I survived cancer—it still can come back. I like to think of myself as a warrior, rather than a survivor.” In terms of names, cancer may be the perfect one for the disease. It’s something that encompasses every aspect of a person’s life. As cells divide endlessly and relentlessly, the cancer spreads, entangling even thoughts—forcing them to confront questions of life, and the meaning of death. Even afterwards, one can never really be sure that it is gone, and cancer’s shadow lingers in the sacrifices made and in the time spent fighting. “It did change my life a lot. When they told me about the things I would have to live with if I survived this cancer, I had to think—do I really want to live? Do I really want to go this route? I decided I really did want to live.”

“Every day I wake up, and I thank my higher power—whom I choose to call God—I thank Him for giving me another day. And I really believe that… I try to cherish every single day. And you know, I try to enjoy myself. I try not to dwell on what I’ve lost. I don’t let it bother me. I just look for other ways to keep myself happy, joyous, and free.”

0 notes

Photo

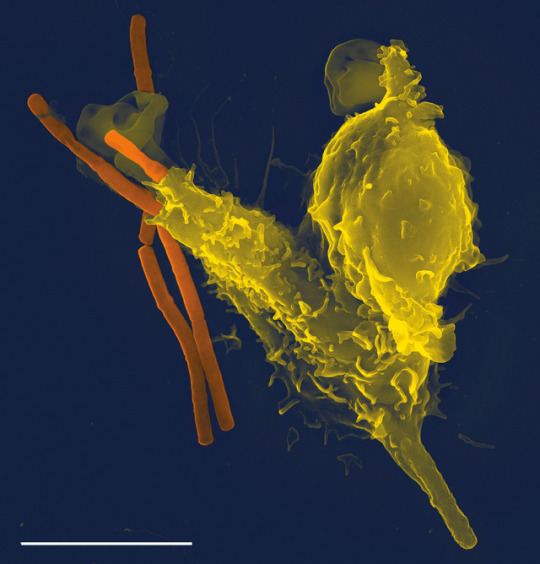

"Neutrophil engulfing Bacillus anthracis". PLoS Pathogens 1 (3): Cover page. DOI:10.1371.

0 notes

Text

“5pm in the hospital” by Aurora Sullivan

The mothers are thinking of ordering dinner,

Looking out the portholes to see if storms are gathering

Breathing a sigh of relief at the empty sky

The mothers are pushing strollers up and down the hallways,

The babies cry every time they stop moving.

The mothers are cracking jokes with the nurses and sanitizing their hands

They are turning quickly away from the bathroom mirrors

The mothers are singing and reading books and praying,

Visiting the gift shop for the hundredth time

The mothers are only screaming internally

The mothers are tired of pizza,

The mothers are calling their own mothers on the telephone,

Saying “tell me what to do,”

The mothers are snatching sleep in gulps punctuated by whispers,

Chasing dreams of smiling babies and a good cup of coffee

0 notes

Text

Listening to the Surgeon General, by Nicole Kim

On November 28th, 2016, then Surgeon General and Harvard College alumnus Vivek Murthy took center stage at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy Forum of the Institute of Politics. Moderated in a discussion by renowned Harvard health economics professor Amitabh Chandra, Murthy addressed the many issues currently facing American health, including the opioid crisis, gun violence, as well as the harmful stigma that surrounds them. About halfway through his talk, he gave advice for college students, especially those pursuing a career in medicine, in searching for solutions to these issues. He warned, “science can’t explain everything,” for a crucial aspect of understanding a problem is rooted in the artistic way through which people express themselves. “Storytelling in medicine often gets sidelined to science.”

What is narrative medicine? In fact, it is the very “sidelining” to science Murthy articulated, the artistic expression necessary for the creation of health solutions in present day. It is a novel medical approach that specifically recognizes the value of people’s narratives in the diagnosis, research, and treatment of illness, a holistic strategy accounting for the relational and psychological features inherent in physical disease. By treating the patient as an individual entity rather than a collection of isolated symptoms, narrative medicine aims to encourage creativity and self-reflection in the physician.

As a freshman in college, taking introductory math and science courses, the idea of narrative medicine was quite intriguing. A pre-medical student myself, I felt fairly knowledgeable about medical narratives and novels, having read the best-selling works of Oliver Sacks, Atul Gawande, and other physician-authors throughout high school. However, as Murthy succinctly stated, solutions to the health issues of our time cannot be solved with purely scientific methods, an idea that heavily influenced my taking of social science and humanities focused classes, such as medical ethics and sociology. It is the recognition of this fact, the necessary consideration of unquantifiable factors often less apparent, that drives a holistic education despite the inherently technical and quantitative nature of medicine.

Narrative medicine is being pioneered by individuals like Rita Charon, executive director of the Program in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University Medical Center. With both an M.D. and professorship in clinical medicine as well as a Ph.D. in English, she defines herself as one who came to medicine as a “lifelong reader” [1]. However, she realized she did not know much about stories as a doctor early in her career, and instead went to the Columbia University English department to ask, “Could you teach a doctor about stories and how they work?” The department joined her in the idea that specialized, narratological knowledge could do some good in the world, particular in the field of medicine. Charon defines narrative medicine as simply “clinical practice fortified by the knowledge of what to do with stories.” It is not just having a sense of story, but rather also being able to recognize when someone is telling you a story, and being able to receive all of it, especially details left unsaid. What then matters is how one interprets, honors, and is moved to action by these elements.

Through her novel and TEDx Talk, both entitled “Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness,” Charon has recounted examples in which narrative medicine has changed the way she conducts clinical medicine. For example, most doctors usually acquaint themselves with new patients by asking a seemingly infinite list of symptom-related questions: what hurts, where it hurts, to what extent does it hurt? Instead, Charon begins by stating to patients: “I will be your doctor, and so I need to know a great deal about your health, your body, and your life. Please tell me what I need to know about your situation.” Simply sitting and absorbing what is said, without the distraction of typing or note-taking, she realized that what patients yearned for most was an audience, someone to eager to listen to the detailed and profound accounts of themselves they were equally eager to give. Some patients were perplexed when given the opportunity to speak, while others broke down in tears with gratitude.

The novel approach of narrative medicine is considerably relevant, for there exist many effective, yet economical ways to teach the skills needed to enhance the clinical experience to all types of health care professionals. These techniques are at most a basic understanding of reading, writing, storytelling, and listening, skills often overlooked by medical schools and other sources of preparation for careers in health. Once this knowledge is disbursed, all that is left is the effort and unrelenting determination of the physician, nurse, or other to practically implement changes that will positively impact their patients, and hopefully improve their outcomes as well.

What are the most pressing issues facing health care systems today, and how do we reform them? This is the million dollar question, something that academics, experts, and Congress having been trying to address for decades. Many blame the rising cost of care, rooted in an uncontrollable, hasty proliferation of medical technology over time. However, as shown by the many ineffective proposed solutions of present day, meaningful change cannot be incurred by means as scientifically based as the technologies that created the problem.

For instance, patient safety standards have seen improvements as a result of methods specifically catered to individual patient interests and characteristics. Peter Pronovost of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine spearheads CUSP (Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program) and TRIP (Translating Evidence Into Practice), programs that address doctor-nurse culture and norms to maximize efficiency while minimizing harm [2]. The success of Pronovost’s efforts are evidence of the importance of the intricate interpersonal relationships that form the basis of administrative efficiency in day to day care. Instead of attacking the problem with complex, costly technology, Pronovost used the knowledge of such a toxic health professional hierarchy, and used additional knowledge and research of how to break down this hierarchy to formulate a solution. This is narrative medicine.

Narrative medicine has distinctive implications in the field of cancer, an area characterized by a wide range of symptoms, courses of illness, and often variability and volatility in regard to recovery and success of treatment. The multifaceted nature of cancer parallels its equally nonspecific definition, “an uncontrolled division of abnormal cells in a part of the body.” Man’s knowledge of the disease is likewise considerably limited. Solutions are almost invariably specific, so what steps does one take in order to tackle a broad problem? Rather, it becomes necessary to utilize patient stories to individualize treatment and uncover the subtle nuances that could ultimately determine a patient’s fate. As medicine has increasingly seen in recent years, specialized therapies tend to engender success over general ones.

In her TEDx Talk, Charon champions the idea that “illness exposes,” that in the presence of disease, there is little to nothing either physically or psychologically separating doctor and patient. In a time of a patient’s extreme vulnerability, narrative medicine can help make this special connection endure by revealing the deepest, most profound truths, creating a lasting relationship effectual in all aspects of life. It can allow patients to come to terms with death and dying, as physicians can urge them to see death not as a failure of modern medicine, but rather as an external, inevitable outcome we as humans must ultimately accept. A novel entitled Being Mortal by physician-author Atul Gawande speaks of this psychological complexity and its implications in end-of-life care [3]. He stresses that the ultimate goal is not a good death but a good life all the way to the very end, that palliative care and the medicalization of aging, frailty, and death can unnecessarily prolong life. Through the new framework of meaning of narrative medicine, we can hopefully avoid these types of situations.

Surgeon General Murthy ended his talk at the Institute of Politics with some valuable insight. Rather paradoxically, he said, in an increasingly connected and networked world, we as individuals are becoming ever more divided and compartmentalized. By recognizing the essence of the aggregate, it is possible to bridge inherent variance and dissimilarity to form a comprehensive whole. Narrative medicine allows us to do just that, in the extremely impactful context of great potential: the beneficence of saving and significantly prolonging life.

Endnotes

[1] Charon, Rita. "Honoring the Stories of Illness." TEDxAtlanta. Sep. 2011. Lecture.

[2] Pronovost, Peter J., and Eric Vohr. Safe Patients, Smart Hospitals: How One Doctor's Checklist Can Help Us Change Health Care from the inside out. New York: Hudson Street, 2010. Print.

[3] Gawande, Atul. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2017. Print.

#surgeon general#narrative medicine#harvard#vivek murthy#atul gawande#rita charon#narrative#medical humanities

0 notes