Text

Short Story: A Voice from the Ashes

A Voice from the Ashes

A Short Story by Qader Moradi

Translated from the Farsi by Daud Razawi

Everywhere I looked, that man’s face appeared before my eyes. In the streets and bazaars, everywhere I thought he was following me. When I looked at passersby, I searched for him – a man who walked with wooden crutches, legs amputated above the knees, wearing dirty, white cloths covered with dry bloodstains and a turban resting in circles around his neck.

This strange, frightening man never left me alone, not even in my sleep. Everywhere he was with me. I tried to get rid of him but to no avail. He was with me everywhere and talked to me at all times. He would not leave me in peace. He mumbled something close into my ears – vague and repetitious.

I thought of finding him, talking with him and begging him to leave me alone. I wanted to tell him that I am innocent; I am not guilty, that I had done nothing wrong. But I could not find him.

The first time I saw him was in the new wood sellers’ bazaar in our city. And I found him in my room that night. I ran away from him and did not see him again, or maybe I saw him once more.

That night, the scream of a woman awoke me. It was in the middle of the night. I aberrantly got up. The room was dark. I struggled to find the light switch. But before I could find the switch, the shrieking sound of a bullet broke the silence of the night, and the women’s screams and cries filled the night.

I wanted to find the light. I was afraid. Maybe someone shot somebody in the street. But what happened to the light switch? I noticed that the wood heater in my room was lit. Perplexed, I gazed at the heater. My whole body overcame with fear. How could the heater turn itself on? For many days I was alone. I hated the sight of the heater, although my room was cold, I did not want to turn it on.

Fearfully, I looked at the flames inside the heater. Several times I rubbed my eyes to make sure I was awake. But I was awake, and the heater was on. The flames of the fire inside the heater shined through the tiny holes and the reflections danced on the rug. The burning wood crackled making frightening sounds.

My heart rate and shivering of my body increased. Again, I wanted to find the light, when the man’s voice instantly startled me.

“Don’t be afraid… don’t be afraid.”

I quickly gazed at the heater. I could not believe my eyes. The stranger was inside my room, standing next to the heater. I jumped and almost screamed, “Who are you?”

The man’s turban rested in circles around his neck. He said softly, “Don’t be afraid.”

He was disabled with his legs amputated above the knees and stood with crutches under his arms. I did not know what to do. Maybe he intended to kill me. I thought to escape. But then to my surprise, I noticed that the man was crying.

I found the light switch. I turned it on and looked at him. His face seemed familiar. I might have seen him somewhere before. I could not remember where I had seen him.

I hastily asked him, “Who are you?”

Maybe he was not dangerous. Maybe he was in danger and had come to my place for safety.

He cried and did not answer my question. His clothes were white but dirty, with stains of dried blood. From next to the heater, he took a piece of the wood, looked at it and cried. His tears ran down his face. Seeing him crying reduced my fear. Then I recognized him. He was the man I had seen in the wood sellers’ market. My head spun. I became fearful again. That day when I was buying wood, he was looking at me from a distant. I had thought, maybe he has mistaken me for somebody else.

Maybe he wanted to kill me. I wanted to tell him that he has mistaken me for somebody else.

But the man cried, showed the wood in his hand to me and said, “Did you know that this piece of wood came off the window of our house?”

With this question, I felt like he had hit me with that wood on my head. This wood piece is from the window of his house! Now, I understood what he was saying. He had come to take revenge. The wood pieces from his house were burning in my heater. I felt that I was in a very dangerous situation. I had to escape anyway I could. I should not pay attention to his cries. Maybe he was insane. Crazy people do not think logically. It was clear that he was going to kill with this piece of wood. Fearful and with a jittery voice I said, “But I have bought the wood.”

The stranger laughed – he laughed loud like an insane man. Then angrily he screamed, “I know you have bought them! I know. But do you know that the piece of wood is from my house?”

And then he started crying again. He wiped his tears on his sleeves. He took another piece of wood from the heater, cried more and said, “Oh God. Oh my God. My house…the bookshelf of my son…the blood of my six-year-old daughter is dry on this piece of wood. Oh my dear God…my house…our house…our house…our house fell on us. You don’t know we were under the rain of bullets. In a second my family disappeared. I don’t know if the earth cracked and took them or did they fly to the skies, but they were not there. Everywhere I look for them…my wife, my little daughter, my son, my legs, the crib, the shelves, and the doors. You don’t know where they are? Huh? No. You just warm up your room with the wood. Ah, what a pleasant warmth they give to your room!”

And he started laughing aloud, scary laugh. I knew he was not insane. His words did not sound crazy. Laughter and cries, anger and outrage were mixed in his voice.

I said again, “But I bought these woods.”

And then I ran out of the room. I was afraid he might have a gun or a knife with him. I could hear him still laughing and screaming. I did not wait anymore. I ran out of the house and into the street until my foot hit a rock. And I fell on the ashes on the road.

I heard the man’s voice in my ears. The voice came from the ashes, it gave me a shiver. The voice cried, “Run! Run! Burn! Burn! Burn!”

I quickly got up and ran again. The man with the crutches followed me. I ran and ran, but the voice of the man was with me, inside my ears. It was as if the man without feet was in my head, in my ears, sitting there and talking to me. He was crying and laughing a nervous laugh. He was angry. He was screaming, repeating himself.

“What a world we live in. Parents give their children axes to break wood. The doors and the windows of the houses ruined by the war to sell them in the wood market. You do not know this. You just buy the wood to warm up your room with them. The pieces of wood, the broken doors and windows go on the scales and are being sold and bought. The woods from people’s windows and doors, from their picture frames, some already burned by the fire of guns and bombs. It is people’s lives and memories that go up on the scales and being bought and sold. These woods carry the memories of happy families, their laughter. Don’t worry. I cannot catch you. You see, I do not have feet to run. They took away my feet and gave me these wooden crutches instead. You think I am crazy, don’t you? You know it was my father’s house. On every piece of this wood, I see the memories of my past life. I hear from them the laughter of my daughter. See that wood? It was from the family’s old crib. Yes, run! Run away from the wood, from the smell of my kids. I smell my old house in this wood. I passed your street when I smelled my house. The smell came off of the wood you were burning. I came to see my house, my kids and my past life. I came to feel the comfort of my old home from these pieces of wood. Have you ever had a house? Have you ever felt calm and comfort it gives when at the end of a long day you come home? I need these pieces of wood. Regardless of how much they cost. I will buy them back. I will keep them with me to see the last signs of my past life, the last signs of my children – the peacefulness of home. Oh, God. Oh, God.”

I stood at the side of the street and saw crowds of women and children passing by. They were poorly dressed and looked injured. Their head and faces were wrapped in bandages. Their clothes had dried bloodstains. They were saying something. They were screaming and crying. The earth was shaking. The moon in the corner of the sky was shaking. The stars were shaking. The women and children had pieces of wood in their handpieces of wood taken off of windows and doors, of closets and shelves and of old cribs.

They were chanting, "Our homes, our homes!”

They were moving the wood pieces in the air. I was afraid. I ran to another street. And I found myself near the wood market. The moonlight lit the market. The market was busy. There were hundreds of poor women and children, hundreds of carts, hundreds of scales, hundreds of guns, hundreds of buyers, and hundreds of sellers. And there was wood, wood all over the place, pieces of wood half burned, dried with bloodstains. The people’s faces were dusty. Wood pieces were going up, the scales and money were changing hands.

“Look, look, how they buy and sell my life and burn it! You run. Yes, you must run.”

Suddenly, the man without feet came from the crowd of the market. He ran towards me and attacked me with his crutches. I felt a sharp pain in my head and screamed. I woke up. I turned on the light and looked at the heater. Everything was in place. The room was filled with a frightening silence. Even the sounds of the guns and the bombs outside had been reduced. Maybe that night the war had ceased.

The next day I gave all the wood pieces to the grocer in my street, but the nightmare would not leave me in peace. The voice of the man was in my ears everywhere I went. I could not go to the wood market anymore, not even to the grocer in my street. I could not see the ashes anymore. So, I moved from that neighborhood.

One morning in the early spring when the weather was still cold, and the night before it had snowed, I went for a walk. The unseasonable snow and storm had ruined all the blossoms, making everybody grieve.

I passed the cemetery that was at the end of our street. I saw some passersby bending over a dead body. It was the body of a man without feet. His crutches were lying next to him. His turban rested in circles around his neck. His clothes were dirty and covered with dry bloodstains. The night dogs had eaten his face. He was shot. And he held some pieces of wood in his arms. They were blue and looked like they came from windows and shelves. No one knew him or knew why he had the wood pieces.

I became frightened. I looked at the cemetery and saw a lonely tree with all its blossoms withered.

About the Author

Qader Moradi was born in Balkh Province in 1958 and grew up in Faryab province. He completed high school and studied journalism in Kabul. He was a teacher and reporter for Bakhtar New Agency. In 1990, his first collection of short stories was published in Kabul. He was forced to leave Kabul in 1994 because of the Islamist destruction of the city. He currently resides in Holland.

Story Summary

Qader Moradi portrays a scene from the 1990s civil war led by the various Islamist factions who destroyed Kabul, killed thousands of its citizens, and physically and mentally scarred thousands more. Moradi threads a tapestry of trauma and memory in this haunting story.

The narrator, engulfed by guilt, is relentlessly pursued by the phantom of a deformed man whose ravaged life mirrors the war-torn landscape. The wood, once a source of warmth, now burns with the sounds of lost homes and families. It's a chilling indictment of how conflict turns the remnants of ordinary lives into commodities and curses.

Moradi wields stark imagery, contrasting the beauty of unseasonal snow with the grotesque fate of the man who clutches fragments of his former world. Through this dissonance, the story conveys the physical horrors of war and its enduring psychological toll.

This story brings to mind the tales my mother heard in her neighborhood of Murad Khani in old Kabul. Her elders, including grand uncles and grand aunts, narrated frightful echoes in the night—battles bursting with the sounds of clashing swords, people in chains, and cries bellowing from the narrow alleyways. These stories seemed to originate from the turmoil of the late 1800s.

Moradi's short story replaces the weapons of the old with modern fighting tools. However, the restless spirits of our collective past continue to roam and haunt the living today.

This translation, by Daud Razawi, was first published in the October 2004 issue of Aftaab Magazine.

April 23, 2024

0 notes

Text

Short Story: The Fragrance of the Rain-Soaked Earth

The Fragrance of the Rain-Soaked Earth

By Qader Moradi

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad

Renna stood on the flat roof of the house, staring over the worn-out wall's edge. Viewing the green fields and tall trees filled her with joy. Everything seemed fresh and new to her. The scent of the rain-soaked earth stirred an unfamiliar sensation within her.

The moist mud-brick domes of the houses appeared anew to her as if she noticed them for the first time. The spring air carried her emotions and imagination to far-off, magical lands, giving her a strange yearning.

However, the fear and dread that had taken root in the corner of her heart stopped her from finding peace. Despite understanding she had defied Rahman Bai's orders today, she attempted to drive away her fear of him.

She heard a whisper, "Renna, finish the rug. The tourists are waiting."

She knew that if Rahman Bai found out she had not worked on the rug today and scaled onto the roof, another frenzy would follow. As always, Rahman Bai's senseless anger would flare up, and he would mercilessly thrash her. Renna knew this all too well, but she was ready to take any beating this time. She no longer wanted to live fearing Rahman Bai's crazed wrath.

Renna didn't want to be terrified of Rahman Bai anymore. She didn't want to miss such lovely weather and the sight of blossoming trees and lush green fields. Living like this for a moment was worth everything. She imaged Rahman Bai's protruding belly, thick fleshy neck, and bloodshot eyes. She felt that she wasn't afraid of him today.

A smile crept onto her lips. Rahman Bai seemed small and powerless to her. In her heart, she whispered, "Let him do whatever he wants."

She forced the thoughts of Rahman Bai.

After many years, it was as if her feelings and fantasies, like butterflies, had been liberated from captivity. They flew to mysterious lands of emotions, filling her ill and forlorn body with an unrecognizable happiness. Being removed from these beauties saddened her. Her past returned.

Six months had passed since the severe and persistent coughs had been taking her life away. These days, she spewed blood and phlegm. Glancing at herself in the mirror, she astonished herself with her reflection of how fast she had lost her freshness and spirit in her father's house. She was terrified to look at her sunken cheeks and dark-circled eyes. She examined herself more finely and drifted into thought.

A great sadness weighed on her heart. She would hear the same mouthpiece again at such moments, bellowing: "Renna, finish the rug. The tourists are waiting."

She would have to go to the rug-weaving loom, but her illness and persistent coughing prevented her from weaving the rug perfectly.

Plunging into her bed and coughing from the intensity of the pain, she would twist and turn in pain and become weak, calling out to her mother in a high-pitched voice. But no one came to her help. Just as she stared absently into space, without control, tears glided down her thin, gaunt cheeks.

She had a yearning rooted in her heart. She wished to release herself from rug weaving and Rahman Bai's torture. She imagined her as a free bird, but with clipped wings, grounded to weave rugs forever.

Now, she saw herself as a bird flying with wings amidst the lush fields and blooming trees. She flew to wherever her heart desired. She felt happy. She thought she shouldn't taint life's unmistakable and captivating moments with painful memories.

The sun, the pleasant spring air, and the scent of rain-soaked earth aroused a peculiar feeling. For the first time, she felt the charming taste of fleeting, exciting moments of life. She no longer wanted to die young, she was no longer afraid, and she no longer wished to return to the rug-weaving loom. But the past memories returned continuously, breaking her heart.

Her past was dim and stifling, like the room where she wove rugs or the stable where she milked Rahman Bai's dairy cows. She didn't want to think about it. Today, after many years, she felt that she had emerged from a moonless well and saw a glow. She didn't want to spoil these sweet, pleasant beats with bitter memories.

Renna's father would take her rugs to the market and return with pocket money, happily shouting: "Everyone treasured them! The tourists were dazzled, dazzled…"

Two years ago, when she turned fifteen, they fetched her from her father's home to Rahman Bai's. Renna entered a new life among Rahman Bai's old women and young girls collection. Life took on a different shade.

Rahman Bai roared: "You shameless woman! I didn't get you for free. I paid money… money!"

He squawked: "I've already sent three of my wives to the graves, and I'll send you there too…"

With his buddies and in high spirits, he laughed and announced aloud, "Learn from me…pleasure…and money."

He puffed his chest, "At a high cost, I hire a rug-weaving girl. She weaves rugs, and her price is covered after six months, with the rest being my profit."

His friends laughed, and Rahman Bai gloated with pride, affirming: "If one dies, I'll take another rug-weaving girl. Do you understand, a little girl…another fourteen-year-old rug weaver…"

Everyone chuckled. Rahman Bai joined in and blissfully shouted, "Learn from me, from me."

Many times, Renna overheard these exchanges from behind closed doors. Rahman Bai's other three wives and all his elderly and young daughters were aware of these talks, but they pretended ignorance. They were scared of Rahman Bai's wrath.

Fear had become a regular partner in Renna's life. She was afraid of Rahman Bai, his wives, his daughters, and even the servants. She was terrified of everything and everyone. She had no one to confess her sadness to. A world of dread and loneliness trapped her.

But today, Renna felt different for the first time in a long time. She felt a sense of independence and hope. She believed she could escape the clutches of fear and loneliness and lead a different, better life.

The sun shined brightly, the birds sang happily, and the flowers bloomed as gems. For Renna, the entire world smiled at her. She breathed deeply in fresh air, and energy flowed through her veins.

She knew she had to do something, that she had to change her life.

Unsure what to do or where to begin, she knew she couldn't stay. She had to break free from the chains that tied her and discover her own way.

She pretended she hadn't heard and behaved as if nothing had been said. But Renna's mind bore to those exchanges, particularly after the illness and coughs that had woven into the lives of all Rahman Bai's women and girls, shaking the branches of their youthful spirit. Like them, Renna's youth was robbed.

Once again, tears welled up in her eyes as she remembered another sore memory. She couldn't overlook her newborn child's death last year because of Rahman Bai's beatings.

She gazed again at the lush green fields—the sun's warmth soothed her illness and exhaustion. The world seemed attractive and stunning. Again, she thought she shouldn't taint life's captivating moments with painful memories. She no longer wanted to die young. She was no longer afraid. She yearned to glide from the rooftop like a bird, flying in the clouds and reaching faraway lands. But she knew she couldn't.

Unconsciously, she looked at her fingers, the bluish dye of her bones visible. The threads of the rugs she wove caused her sore nails to become gnarled and bloody. She saw herself as a clipped-wing, mutilated bird.

She looked at the sky, fascinated by the clear blue color and the white threads of the clouds. She craved to fly, to spread her wings and soar among the clouds. The world seemed beautiful and alluring to her. She saw everything in tints of green, everything in flowering. The fragrance of rain-soaked earth stirred a mysterious longing. She didn't know what she wanted but felt uneasy and restless. Her heart murmured, and a rousing excitement rushed through her veins. Renna wanted to do something, but she didn't know what. Suddenly, a voice surprised her.

Rahman Bai's angry voice growled inside the courtyard, shattering her fragile daydreams. "Where is Renna? Renna…”

A woman answered, "We don't know where she went. We have no idea."

Rahman Bai asked, surprised, "You don't know? Why don't you know? Find her!"

He then shouted a couple more times, "Renna! Renna! Where did you go, Renna!"

Renna knew what was expected of her. She remained still. Ignoring Rahman Bai's shouts, she stared off into the distance. The hollering didn't stir an inch of fear. The warm sun rays brought the lush green fields and flowering trees to life. She didn't want to lose these precious and pleasant moments. She wished to remain in this form until her last breath, with the butterflies of her imagination gliding freely to unknown lands of hopes and feelings overflowing her with this lovely, unspoken desire.

Rahman Bai continued, "Find Renna! She needs to finish the rug. The tourists are waiting for it."

Renna had always hated the word "tourists." She had never seen them but heard that they were rich outsiders. She sensed she was in this miserable condition because of the tourists. In her heart, she cursed the tourists: the hell with them.

Her head spun, and she realized she could no longer stand. Rahman Bai continued to shout and scream. The rhythmic clacking of looms could be heard from inside the houses. Rahman Bai's elderly women and young girls had returned to their looms.

Renna sat down quietly on the rooftop and leaned against the wall. She coughed a couple of times, spitting up phlegm and blood. She covered her eyes, imagining the foliage and flowers. The heat of the sun tickled her ill body. Everything appeared like lush green fields and trees in full bloom. Everywhere smelled of sun-kissed blossoms and the azul sky. Multicolored butterflies fluttered everywhere. She found herself in the white clouds of the sky. The scent of rain-soaked earth stirred a mystifying sensation, drawing her to unknown lands and a delightful feel.

Abruptly, she heard Rahman Bai's raging, furious voice nearby, "You shameless woman, what are you doing here?"

Renna understood the situation. She didn't move, not even open her eyes. She decided to remain in her colorful and lyrical dreams. She thought that opening her eyes would once again drop her from the sky's white clouds into a dim, stifling well.

Rahman Bai's heavy kicks showered down on her head and body a moment later. Rahman Bai's screams reached a crescendo. He bombarded like a madman, screaming and hollering. Like birds with broken wings, the women and girls gathered mutely and mournfully, watching Rahman Bai and Renna on the nearby rooftops.

Renna squirmed under Rahman Bai's kicks. She had decided not to open her eyes to him. Her heart couldn't bear to see his cruel mug and bloodshot, terrified eyes again. She squirmed under Rahman Bai's heavy boots like a bird with broken wings.

The cauldron of Rahman Bai's rage and madness boiled over. Like a ferocious and wild animal, he growled, attacked, kicked, pulled Renna's hair, and flung her about.

But Renna's eyes never opened. She felt closer to the sweet scent of rain-soaked earth, to the lush green fields and the fragrance of blossoms, to the unknown and mysterious lands, and Rahman Bai grew even more angry.

He hollered and said, "The tourists are waiting… the tourists… you had to finish the rug, you shameless woman, the rug… the rug…"

And Renna said to herself, "Curse the rug, curse the tourists," and inhaled the scented rain-soaked earth.

- - -

About the Author

Qader Moradi was born in Balkh Province in 1958 and grew up in Faryab province. He completed high school and studied journalism in Kabul.

He was a teacher and reporter for Bakhtar New Agency. In 1990, his first collection of short stories was published in Kabul.

He was forced to leave Kabul in 1994 because of the Islamist destruction of the city. He currently resides in Holland.

- - -

Summary of this Short Story

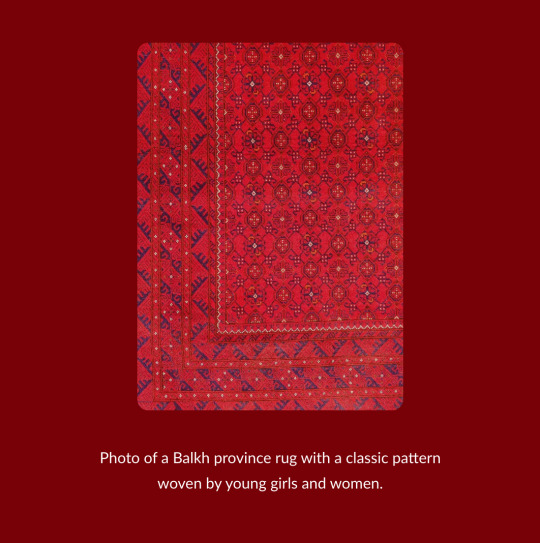

In his short story "The Fragrance of the Rain-Soaked Earth," Qader Moradi offers a tragic look at the lives of oppressed women exploited in sweatshop weaving compounds within his native northern provinces of his youth.

He focuses on Renna, a teenager robbed of her adolescence, child, health, and spirit under the ownership of a cruel weaving master. Yet, one morning, veering into the vista of lush tall grasses, trees, and flowers, this spring beauty awakens Renna's soul, stirring dreams of escape.

She longs to soar into the clouds and distant lands, but knowing her circumstances, she understands her wings are clipped – a familiar metaphor in Farsi literature (پرو بالم شکسته). Unable to escape, Renna clings to her dreams, seeking solace in the season's beauty even when struck violently.

Writer Mohammad Hossein Mohammadi summarized Moradi's frequent themes: his characters seek a way out into dreams in the face of unbearable circumstances. "The Fragrance of Rain-Soaked Earth" reflects this theme, with even the simple scent of rain becoming a pathway to defiance against her cruel reality.

—Farhad Azad, April 21, 2024

- - -

Caption: Photo of a Balkh province rug with a classic pattern woven by young girls and women.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

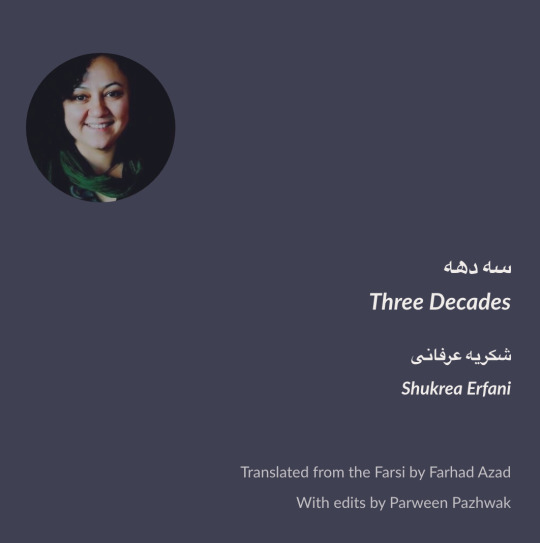

Three Decades

سه دهه

Three Decades

شکریه عرفانی

Shukrea Erfani

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad

With edits by Parween Pazhwak

At the age of ten

به پسر سیاهچردهی همسایه

the neighbor’s dark-skinned son

که برایم از دکان سر کوچه

who from the alley’s corner store

خوراکیهای خوشمزه میدزدید

thieved delicious treats for me

قول ازدواج دادم

I promised him I would marry him

در بیست سالگی از خانهی پدرم

At the age of twenty in my father’s home

که مردی محترم بود

who was a respectable man

نمازهای طولانی میخواند

who prayed for long stretches

و شبها از کنار زنش به بستر من میخزید

and at night, veered from his wife’s side to jump into my bed

گریختم

I fled

در سی سالگی آنقدر از خواندن شعرهای فروغ

at the age of thirty from reading so much of Frough’s poetry

و تحمل زمستانهای لجوج مسکو خسته بودم

and the enduring the brutal cold Moscow winters

که به سیم آخر زدم

that I reached my limits

و خودم را به دست قاچاقچیهای انسان سپردم

and I surrendered myself to human smugglers

تا به جایی ببرندم

to take me somewhere

که آسمانش همیشه آفتابی باشد

with perpetual sunshine

ده شبانه روز تمام کشتی مان در طوفان جان میکند و نمیرسیدیم

for ten days and nights our ship wrestled for its life in a storm

میبینی؟

Do you see?

درست هر ده سال یکبار

Exactly every ten years

اشتباه بزرگی

a grave mistake

مسیر زندگیام را به بیراههی دیگری کشانده است

has astrayed my life’s path another route

در این میان البته

in between, perhaps

کارهای احمقانهی دیگری هم کرده ام

I’ve done frivolous things as well

عاشق شدم مثلا

For one, I fell in love

ادبیات خواندم

I studied literature

به پوچی انقلابها دل بستم گاهی

At times I entangled myself in hopelessness revolutions

آلوده کردم خودم را به سرگیجهی شراب و سیگار

I soiled myself in drinking and smoking cigarettes

و بیوقفه

and without a break

بدون آنکه

without even

هیچ وقت به روی خودم بیاورم دردش را

acknowledging the pain to myself

سینه به سینهی زندگی ایستادم

I stood directly facing life

جنگیدم و هر بار به سختی شکست خوردم.

I fought and every time I lost.

حالا اما

Yet now

در آستانهی چهل سالگی

on the threshold of my forty birthday

در لحظهی آن اشتباه بزرگ دیگر

in the moment of making another grim mistake

هنوز

still

این خون شوم بیتاب را دوست دارم

I love this restless, fated blood

هنوز دلم میخواهد

my heart still wants it

بتازد در من

to flow through me

و هر روز زخمیتر از روز پیشم کند!

and make me more wounded than the day before!

- - -

Shukria Erfani's poem charts a soul's restless course. Each decade seeps into the next, and every choice is a lingering ghost. Love, rebellion, the stinging memory of escape—still, that relentless pulse throbs on, a wound demanding its due.

With the cold clarity of approaching forty, a painful truth emerges. There is beauty in this ceaseless struggle, a discordant symphony in the fight she never sought yet continues to wage.

—Farhad Azad

April 16, 2024

- - -

Shukrea Erfani, born in 1978 in Qaharbagh District, Ghazni province, grew up as a refugee in Iran and graduated university with a degree in literature.

Erfani has published two volumes of work با زبان تنهایی The Language of Solitude, and اندوه ما جهان را تهدید نمیکند Our Sorrow Doesn’t Threaten the World.

She currently resides in Australia.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

They buried Qahar Asi with his poems

They buried Asi with his poems

By Rahmatullah Begana

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad

Kabul's weather offered a mild respite on a somber autumn day, the city holding an unusual calm. No fighting erupted, and not a single rocket pierced the sky, a stark contrast to the usual barrage. It was September 28, 1994.

People tentatively emerged from their homes, children resuming their playful pursuits. We longed for a break, a departure from the usual war-ridden bedlam. The people huddled in their corners. As the sun dipped low, Qahar Asi approached us.

Due to the intense conflict in Kabul's Microrayon sectors, Asi, freshly returning from Iran, had left his home and now lived with his in-laws in Karte Parwan. We also lived in Karte Parwan. On September 28, Asi appeared on our doorstep, inviting us for a stroll.

We invited Asi inside, but he declined. With some reluctance, my brother Azizullah Ima and I finally ventured out with Asi.

The people of Kabul had quarantined themselves due to the rocket strikes and fighting. Aside from a few desperate souls, no one dared venture beyond their doorways.

Asi's insistence on an outing filled me with dread. Intuition warned of impending unease that day, yet I remained blind to the unfolding events. Asi led us away. Before long, he began reciting poetic verses from his earlier days.

We immersed ourselves in the warmth of prose and poetry alongside Qahar Asi. He recited his verses, each carrying a wealth of tales and portrayals. It was as if he sensed that these were the concluding hours of his life, eager to share his newly composed verses with his audience and friends.

Asi turned the pages where he had penned his poems, his enthusiasm radiating as he retrieved one poem after another from his shirt pocket, reading them gracefully and eloquently.

"Kabul, O Kabul,

the gushing blood from your throat,

how does the earth hold it without pain?

Who will lift your shredded coffin towards the sun?"

Asi carefreely recited his verses as the distant echoes of rockets reached our ears. For the first time, genuine fear gripped me. Though we had grown accustomed to the explosions, the rockets seemed to be heading straight for us.

We walked a considerable distance, returning from the Bagh Bala area as the explosions grew louder. Undeterred by the danger, Asi continued to recite in his woeful yet magnetic voice.

"These words aren't for the harsh autumn wind

these words aren't for the boulders

these words aren't for the eroded, lofty slopes.

the mountain has its sorrow,

the river has its sorrow,

the grove has its sorrow,

sorrows that destroy them"

Asi continued his passionate storytelling, and the explosions were ongoing. I suggested we veer from the main road close to the Kart-e Parwan intersection, away from danger, towards the narrow lanes nestled against the high hill.

In those days, the narrow lanes were lined with single-story mud homes, and only a few people moved about.

Kabul's ongoing war had ravaged the electricity and water systems. We had access to running water one day out of the week and electricity on just a handful of days.

Our journey continued alongside Asi's recitations. At a communal fountain, men gathered water, kids played marbles in the middle of the alleyway, and some children sought refuge, playing with dolls by the wall.

Asi recited verses with fervor. Due to my worry, I couldn't fully comprehend my friend's words. My brother and I trailed by his side.

The autumn wind carried Asi's voice, rising and falling with his recitation. I was nearing our home and eager to arrive quickly, yet time stood still. Our legs felt heavy, defying our attempts to move faster.

Seconds stretched, heavy with danger, as time ticked towards a catastrophic event. Three friends walked unknowingly towards it.

Yet we pressed on, but time remained stagnant. And then, from behind, the calamity that followed trapped us in the alleyway, forever altering our lives. No longer were we whole individuals. We were labeled the wounded and martyred.

Everything fused, and Asi fell silent. We, along with the little boys and girls of the alley, crashed to the ground, enveloped in dust and blood. Asi's recitation seemed to mingle with the cries of the wounded children as their voices choked the alley.

After a few seconds, as the dust and debris rose from the ground, I realized the absolute silence that had settled over Asi and Ima. Only my voice remained—a voice of sorrow, pain, separation, lament, despair, and hopelessness.

I couldn't understand what had happened, what catastrophe had befallen us, why we lay on the ground, covered in dust and blood. I was utterly bewildered and stunned!

The situation in this alley stood deeply sorrowful and heartbreaking. Yet, no one realized that a talented poet of verses had fallen, covered with soot and blood.

Liberty itself had fallen, lifeless and without support. No one reached out to help, for it no longer needed a hand. The dead and wounded littered the alleyway, and Asi— the voice of unwavering freedom— had also been silenced, deprived of life. Young men from the alley rushed to help, taking us to the hospital. The relatives cried and wailed loudly.

Asi and Ima lay still beside the blue-tinted gutter— people supposed they were martyrs. I begged the young men to help my brothers! They explained another vehicle would transport them and urged me to hurry due to my severe bleeding. Ima and Asi rested a short distance from me, motionless and silent.

The young men in the alley lifted me and took me to Abu Zaid, the nearest and the only private clinic in Kabul, in the Kart-e-Parwan neighborhood. When Ima and Asi arrived at the general hospital, the clinic staff mistook them for dead and placed them in the morgue.

I was in better condition than they were. A large piece of debris had struck my right leg, breaking the shin bone. A doctor at the clinic wrapped my leg with a bandage to slow the bleeding.

He said, "We can't do anything more here. You must transfer yourself to a government hospital."

The sky darkened, yet the sound of piercing rockets continued. An ambulance transported me to the government hospital. Memories of my mother's illness and death filled me in this familiar hospital, where I first saw Ahmad Zahir, the famous singer—days of hoping for my mother's recovery had been spent in its rooms and corridors.

But this time, a different tragedy had brought me here. Even as my condition remained poor as I entered the large hall and corridor, countless stretchers overflowed, leaving no standing room and crowding the space with the wounded and dead.

The young doctor looked familiar. He addressed the people who had brought me, "There is no space for beds here. Take your patient to the Wazir Akbar Khan hospital."

I recognized him and asked, "Are Asi and my brother among the wounded?"

He recognized me, too, and gently removed the white cover from my brother's bare body. "Don't worry, he is receiving treatment now," he reassured me.

Seeing my brother's face, I relaxed momentarily but remained deeply worried. My eyes searched for Asi. Once again, I joined the wounded on an ambulance ride to the Wazir Akbar Khan hospital.

On the way, a girl with eyes closed died silently as other children moaned in pain. One of these teenagers repeated: "O God, what sin have we committed that we are torn into pieces like this?"

The streets were empty. We quickly reached the hospital. As they removed me from the vehicle and placed me on a stretcher, many worries filled my mind. What had happened? Would Asi and Ima receive treatment?

The pain in my leg intensified. They carefully lifted my broken leg with both hands and took me to the hospital's surgical operations department. At 9:00 pm, I entered the operating room without my family present or a blood supply.

Before I passed out, a doctor who was busy operating on a patient asked his colleague, "What was the news at 8 o'clock?"

The second doctor replied, "Is there anything else in this country besides stories of pain and sorrow? Did you hear that the young poet—I'm talking about Qahar Asi— was martyred in today's rocket attack!"

"With God, we belong, and to him, we shall return," I thought to myself. Hearing this news, despair and hopelessness washed over me so vigorously that I could only remain silent and suppress my grief.

Asi's stories, laughter, passion, vitality, life, and poetry flashed through my mind. I said goodbye to everyone in my imagination. I didn't think I could survive this struggle alongside him. Seconds later, I passed out.

After the surgery, which took about two hours, according to Dr. Mozef, I struggled to regain consciousness due to extreme anemia. Death lingered close by. I felt as though I was hanging upside down from my feet.

My fight between life and death raged for more than seven hours. Finally, my condition began to improve slightly. I opened my eyes in the morning to a dark room with only the faintest dawn light filtering through the curtains. I couldn't remember anything.

Confused, I tried to understand why I was in this situation to no avail. I felt no pain, only the effects of severe anemia and the intense side effects of anesthesia, which slurred my words.

I felt people hovering over me, but my eyes wouldn't focus properly. I couldn't understand where I was! The silence puzzled me. Then, I recognized the dimmed hospital lights and the faint glow from outside.

I surveyed my surroundings; everything seemed strange, black and white. Seeing the IV stand confirmed my location. But none of my companions from the ambulance or the neighborhood kids, Ima and Asi, shared this space.

I remained in the hospital for days. Once I recovered somewhat, I went to visit Asi's mother. Upon my arrival, her distress intensified. She is a wise and kind woman who sees me as a reminder of her lost child, her young son who died too soon – a reminder of her son's untimely passing and the enduring pain she bears. Even though 26 years have passed since Asi's martyrdom, she still mourns and weeps as she did in the early days of Asi's death.

Asi's mother lost her composure at seeing me and began to cry. Everyone relived the great sorrow of the poet's death for a few moments.

I said, "Mother, I wish I had died instead of Asi."

She replied, "My child, you are the reminder of my son, and I sense Asi in you. May God grant you longevity and virtue."

I asked, "What happened to the poems from the day of Asi's incident?"

Mubin, Asi's brother, who was sitting with his mother, answered, "We buried Asi with his clothes and poems."

May the memory of my dear and beloved friend and companion, Abdul Qahar Asi, be cherished!

- - -

On September 26, 2020, the digest "8 AM" published Rahmatullah Begana's lamentable words, marking 26 years since Qahar Asi's voice fell silent. Begana's memory paints a dour portrait of Kabul in the autumn of 1994, a city choked by smoke and despair, where the relentless rhythm of rockets tore through the fragile silence. It was amidst this symphony of destruction that lives shattered, and so too, a poet's pen.

Begana's words weave an intimate tapestry of his friend and poet, Qahar Asi. He paints Asi's final moments with heartbreaking clarity, showing how even as the world crumbled around him, Asi clung to the lifeline of his poetry, his lyrics a defiant chorus against the descending darkness.

Though Asi was cruelly taken, his legacy blazes a defiant trail against oblivion. His poems are not merely words but searing echoes of a people's wounds, dreams, and resilience—beacons that will continue to light the path for generations to come.

—Farhad Azad

April 13, 2024

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wasef Bakhtari on Layla Sarahat Rushani’s collection of poems “From Stones and Mirrors”

Wasef Bakhtari on Layla Sarahat Rushani’s collection of poems “From Stones and Mirrors”

This is an excerpt from Wasef Bakhtari's (1943-2023) forward of Layla Sarahat Rushani's collection of poems "From Stones and Mirrors" (از سنگ ها و آینه ها).

The land of poetry, especially its poetry, is one of the most challenging tasks, and how many heads and pens have struggled and broken on this path.

However, Layla Sarahat Rushani is one of those who has never taken even half a step to be discussed. This is not only my word; many of her poetry enthusiasts agree. I add that she has taken this approach not only out of modesty and humility but also because she believes in the power of her poetic talent and authenticity.

She reads, composes, and writes silently. She is aware of the ability to accept beauty and create beauty in the Farsi language's words and the musicality of the juxtaposition of words in a stunning language. Those who have burned the midnight oil know what a great price must be paid for this understanding.

I see Layla Sarahat Rushani's path, which begins with Rabia Balkhi and connects to Forough Farrokhzad. I see the drops of blood that have oozed from the blisters of her feet of contemplation in treading this path and have settled on the stones and pebbles.

How can one become the daughter of Ferdowsi without this passionate but rewarding journey? She filled the cell of Bayhaqi (10th-century Ghaznawi poet) with color in the solitude and isolation of old age and house arrest, gave Saadi a cup of water in the Nizamiyah of Baghdad, and finally laid her head on Parwin's lap and combed Forough's disheveled hair and shared her heart with Emily Dickinson and Anna Akhmatova. Also, from Nima's "neighbor," she "heard" the "words" of careful listening, a success that few in our country have achieved.

The result of this painstaking effort is that today, her poetry is one of our country's highest forms of poetry. Her continuous work, full of the fragrance of honesty, sincerity, and love, in composing and singing the hoopoe of the city is a journey to the shore of culture, which this submarine will soon reach. It will become clear that it has been the ideal city for great poets. I still consider poetic imagination and enlightenment a level of the poet's soul.

The shy little girl I saw years ago in the house of the [slain] poet Sarahat Rushani [Layla's father], who was as tall as the small saplings that he had planted with his own hands and who played youthful games and plucked the leaves of the saplings, has now grown up, and her poetry has become a tree, much more immense than those saplings that have become trees in her house, and has added jeweled trunks to the forest of Farsi poetry.

This is the same Layla Sarahat Rushani, our sister, who shares our heart and the language of our generation and the generations to come. This is the same Layla Sarahat Rushani, one of the master poets of our time, with the nobility of a saint, hardworking, humble, and herself.

The announcement of the publication of Layla Sarahat Rushani's third book of poetry, with the clarity of the sun and the eloquence of the spring rain, sends a message to the lovers of poetry: I am the shadow of the hand and the bearer of thought, a powerful speaker and poet in this word's full depth and breadth.

—Wasif Bakhtari

Kabul - 15th of Farwardin 1375

Kabul - 6th of April 1996

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad, spring 2024

1 note

·

View note

Text

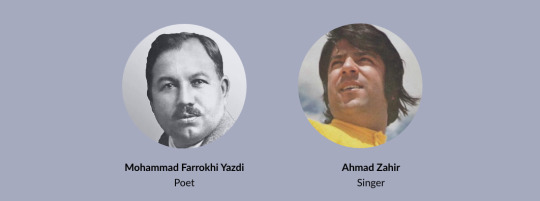

شب چو در بستم |As the night embraced me tightly | احمد ظاهر | Ahmad Zahir

شب چو در بستم

As the night embraced me tightly

آواز احمد ظاهر

Song by Ahmad Zahir (1946-79)

شعر محمد فرخی یزدی

Poem by Mohammad Farrokhi Yazdi (1889-1939)

شب چو در بستم و مست از می نابش كردم

As the night embraced me tightly, and I lost myself in its pure wine

ماه اگر حلقه به در كوفت جوابش كردم

If the moon tapped at my door, I paid no heed

غرق خون بود و نمیمرد ز حسرت فرهاد

Drenched in blood and not dying like the longing of Farhad

خواندم افسانه شيرين و به خوابش كردم

I recited the sweet legend and immersed myself in its dream

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad, with edits by Parween Pazhwak

Spring 2024 | بهار ۱۴۰۲

* The phrase “sweet legend” is a play on the word “shirin,” which literally means “sweet.” It also refers to the story of Princess Shirin and the sculptor Farhad, as told in the “Shahnameh,” “Khosrow and Shirin” and folk tales.

With his soulful voice, Ahmad Zahir brings to life the verses scribed over a century ago by Mohammad Farrokhi Yazdi.

As the sun sets and darkness envelops the land, Ahmad Zahir finds solace in the twilight. With the virtuous wine of the night, he begins to recite the age-old story of Farhad and Shirin. It's a tale of undying love and heartbreaking tragedy passed down through generations.

Farhad, the legendary sculptor, pours his heart and soul into carving steps out of the rocky cliffs, hoping to win the hand of his beloved Shirin. His determination knows no bounds as he toils day and night, driven by his unwavering love.

But fate has other plans. Just as Farhad nears the completion of his monumental task, tragedy strikes. A cruel deception orchestrated by his rival shatters his world as false words reach Farhad, telling him of Shirin’s death.

In a moment of despair, Farhad takes his own life— he stabs his chest with the sculptor's chisel and throws himself off the steep cliff. It's a tale of love and sacrifice, dreams crushed and hearts broken.

Yet, despite the tragedy, Farhad's story resonates through the ages, inspiring countless souls to pursue their dreams against all odds.

In two lines of the poem, Ahmad Zahir's voice carries the weight of this timeless tale. His songs are not just poetry—they reflect his heartache, a bittersweet reminder of the fragility of love and the inevitability of loss.

As a child listening to Ahmad Zahir's cassette tapes, I eagerly listened to this song and awaited hearing my name. With excitement, I would exclaim, "He sang my name!" It was a moment of sparkling magic. Many years later, I still feel the same.

Mohammad Farrokhi Yazdi (1889-1939) was a writer and political activist who played a significant role in creating the Iran Constitutional Revolution (1905-11), which included the establishment of the parliament in Iran. He also published the political journal Storm, which he used to criticize the totalitarian regime of Reza Shah (r. 1925 – 1941). Unfortunately, he was arrested and executed in a Tehran prison.

The singer, born seven years before the execution of the poet, met the same fate at the age of 33, alas cowardly masked by the Khalq oppressive regime as a “car accident” near Salang, north of Kabul.

For centuries, these neighboring regions have shared a tragic commonality as is today: the dogmatics’ noose hunts free-thinkers.

Although their breaths may have been extinguished, their art lives on because true art is ardent and eternal.

—Farhad Azad

March 29, 2024

0 notes

Text

Sounds of an Era: Kabul Music 1970s

youtube

ظاهر هویدا

Zahir Howaida, accordion

نسیم

Nasim, tabla

The tabla and accordion paired together was a trademark sound of the 1960s-70s Kabuli “amateuri” movement, music performed by nonhereditary artists.

This improvised piece by Zahir Howaida (1946-2012) and Nasim (1945? —2011) carries the sound and musical style of that bygone era.

— Farhad Azad

0 notes

Text

Jalil Zaland’s “The Sad Flame”

Jalil Zaland’s “The Sad Flame”

by Farhad Azad

Jalil Zaland, جلیل زلاند, was a leading vocalist of Radio Kabul رادیو کابل. In the 1950s, along with a handful of vocalists and songwriters, he ushered the first wave of modern urban music.

Zaland was also a distinguished composer for Kabuli and Iranian artists.

The song “The Sad Flame” stands out from his illustrious catalog of accomplishments. The legendary Ahmad Zahir احمد ظاهر adored Zaland’s voice and this song which he sang on several occasions.

The left-winged political writer and poet Sulaiman Layeq سلیمان لایق penned the lyrics. Zaland perhaps composed this piece himself. This audio recording is from Radio Kabul.

The Sad Flame

By Sulaiman Layeq

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad

ای شعله ی حزين

O' this sad flame

ای عشق آتشين

O' this fiery love

ای درد واپسين

O' this final pain

اين شور توست يا که جنون سرشکها

Is this your passion or tears of madness

يا شعر من که ميدهدم سوز جاودان

Or the poem that I offer shall eternally burn

شبهای بیشمار پهلوی جویبار در صحن کوهسار

Countless nights beside the stream amongst the mountains

دیگر نبویمش

I shall no longer smell her fragrance

شبها نجویمش

I shall no longer search for her in the night

رازی نگویمش

I shall no longer tell her my secrets

تا در فراق و ناله و درد و شکنجه ها

In separation and tears and pain and torment

آهسته طی کنم ره خاموش رفتگان

I wander towards the departing path

پهلوی کهسار

Next to the mountains

در پای آبشار

Under the waterfall

بر روی سبزه زار

In the meadows

بر پا شود قیامت بوس و کنارها

The kisses and embraces have ended

اما ز ما گسسته بود عمر ها عنان

Our lives torn

شاید که سالها

Perhaps in years to come

لرزان ستاره ها

The glistening stars

مهتاب پاره ها

The waxings of the moon

در آسمان صاف و بالای ابرها

In the clear sky and above the clouds

تابد فراز شهر و نباشد ز ما نشان

The city shall shine ,or there will be no hint of us

—Written on June 13, 1959 in Kabul, Afghanistan

Read and listen to Sulaiman Layeq’s Clouds Upon Mountaintops performed by Ahmad Zahir.

0 notes

Text

Conversation with Menosh Zalmai on her book Ode to Qahar Aasi

Conversation with Menosh Zalmai on her book Ode to Qahar Aasi

By Farhad Azad

Aftaab Magazine

In her forward to Ode to Qahar Aasi, a collection of translated poems, Menosh Zalmai writes, "Aasi's poems give me a sense of belonging and connection to the land and people; we were made to leave but never forget."

Published in 2018, the book is a collection of Qahar Asi's unique poems, spanning his early works to his later period. It is available for purchase online.

The first translated poem is "And..." (و...), the ending poem in Asi's last book while he was alive, From the Island of Blood: Elegies for Kabul (1993, Association of Writers Press, Kabul).

The poem speeaks of grieving soul that seeks consolement. The poet asks the little cuckoo bird nested by his home to open its wings and fly because his heart is sorrowful, the breeze to stir because he is breathless, the tree to comfort him because he is restless, and the spring to arrive and sing because he is impatient.

All of that, while the city he loved so dearly is under a rain of death by rockets and bullets. These effusive verses voice the grief of many generations cast by half a century of conflict and tyranny.

Intrigued by her collection of translated poems, I asked Menosh Zalmai to share her thoughts about her book—she did so generously.

She commented on the subject of her favorite poem, "This is a rather difficult question for me because I truly love Qahar Aasi's poems. From his ghazals [odes] to his char-baitis [quatrain].

One of my all time favorites is his ghazal اگر ميشد كه دردم را برايت گريه ميكردم [Where it possible to speak of my pain to you]. Mainly because it highlights our human limitations of expression.

Language falls short in conveying the range of emotions we feel as human beings and in this poem, he so beautifully laments that. If I could, I would...I wish I could. I believe this is a universal feeling. I admire the nuance with which he weaves this poem."

Zalmai acknowledged the lack of translated works in English by contemporary Farsi writers, "I think it's another impact of war and displacement on us. Losing social capital and language is one of the more devastating effects of war, poverty, invasions, and exile. It is hard to write and publish when your first priority is to put food on your table. It is also difficult to learn the language and immerse yourself in it, when you are displaced as a diaspora and have unintentionally lost touch with cultural nuances. It is unfortunate and something that deeply pains me."

Readers have responded enthusiastically to the book and its translation.

"The reception has been heartwarming and I am grateful. I love that despite barriers, diaspora youth and folks want to stay connected with their language, culture and roots. Goes to show that no matter how much they try to destroy us, we will always find a way to survive."

This work is a delightful rarity, a gift for anyone interested in contemporary Farsi poetry written by one of the most important poets of the end of the last century. Despite the uncertainty and war of the time, the poet expressed love and perseverance with unequivocal conviction.

One of my favorite translated lines from the book is filled with notes of unbounded romance vestiges of green valleys and the beauty of spring with a loved one:

آرامش باغ گل به گیسو زدنت

آشـــوب بهار شــانه بر مــو زدنت

برنامه زنده گی سخن های خوشت

سر نامه عشق خـــم بــه ابرو زدنت

Serenity in a meadow; you pinning flowers to your hair

Chaos in spring: You putting a comb through your hair

Life's proposition: Your exquisite words

Love's caption: The arch of your eyebrows

It would be wonderful if Menosh Zalmai could publish another translated collection of Asi's poems—as it would be a valuable contribution to the world of literature.

Purchase the book on Amazon

0 notes

Text

امروز نوبهار است Spring has arrived today

امروز نوبهار است

Spring has arrived today

استاد محمدحسین سرآهنگ

Ustad Mohammad Hussain Sarahang (1924-83)

شعر بیدل

Poem by Bedil (1642-1702)

امروز نوبهار است ساغر کشان بیایید

Spring has arrived today, come with a lifted wine goblet

گل جوش باده دارد تا گلستان بياييد

In hue of wine the flowers stir, come to the garden

Recorded in Kabul, circa 1970s

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad, Spring 2024

= = =

Happy Now Roz نوروز پیروز to all our readers!

As a special gift, we offer you a timeless song by the late master of Kabul’s Kharabat, Ustad Sarahang (1924-83), a devoted follower of the esteemed poet Bedil (1642-1702).

This poem beautifully heralds the arrival of the spring equinox, a moment cherished by our ancestors across generations.

The poet beckons you to join him in the garden, bringing an empty goblet to be filled with the flowing wine.

Amidst the vibrant blooms, reminiscent of the colors of wine itself, let us revel in the joy of renewal and new beginnings.

—Farhad Azad

March 19, 2024

0 notes

Text

افسوس کـه عشق پاک Sadly your pure love | Ahmad Zahir

افسوس کـه عشق پاک

Sadly your pure love

آهنگ احمد ظاهر

Song by Ahmad Zahir (1946-79)

افسوس کـه عشق پاک تو رنگ هوس گرفت

Sadly your pure love took the color of desire

آتش به جان این ثمری زودرس گرفت

The flame hasty reached the soul of this fruit

دانی امید زندگیام بود عشق تو

You know the hope of my life was your love

رفتی و عشق و آنچه به من داد پس گرفت

You left and took back the love you had given me

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad, with edits by Parween Pazhwak.

= = =

Over twenty years ago, I met an acquaintance of Ahmad Zahir, who owned a charming restaurant in Alameda Marina in Northern California. He told me that he had known Ahmad Zahir for the last two years of the singer's life.

He spoke about the curfew imposed on Kabul during the monstrous Khalq regime, how Ahmad Zahir packed his friends in the car and attempted to purchase the last racks of kabobs, tipping the kabob seller's apprentice wads of cash—his friends would heavily protest. Ahmad Zahir would say we should help others in need.

"When you hear his private recordings," he said, "you think there are many people with him, but there were just four or five of us. We would eat and drink, and he would sing with his powerful voice. So powerful, without a microphone, the windows would rattle! He would continue into the night until dawn."

These stories provide a glimpse of a man whose voice is heard worldwide, every hour, day and night. Yet so little of his story is written. What we have are petite fragments of oral history from those few who remain with us today.

For me, this song افسوس کـه عشق پاک ("regretfully your pure love") has a unique place for all those who have lost a love— and we are left with is a bitter emptiness.

The contemporary poet Liala Zaray wrote, "I truly believe there's an Ahmad Zahir song for every feeling."

I wholeheartedly believe she is right because his songs are genuine art that mirror reality.

He never recorded this particular song on the radio Kabul or private labels, and the composition and poet are still unknown to me.

One can possibly hear Nainawaz's roaring voice in the background on the track. Was he the composer?

When I listen to this song, I imagine traveling through time to one of these cloistered evenings. Ahmad Zahir, Kabul's evening nightingale, sings until the first light, and then the winged nightingales carry his place in the garden to rouse the flowers from their slumber. The dew, the tears of the night from his sorrowful lyrics, gingerly fall from the soft petals.

— Farhad Azad

March 16, 2024

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

گل می گذرد In the blink of a blossom

گل می گذرد

In the blink of a blossom

فرزانه خجندی

Farzaneh Khojandi

ای رشک سرور، ای دسته نور

The envy of delight, the cluster of light

ای در بر من وی از همه دور

You, in my embrace, and far from others

از آن سوی دل، از آن سوی جان

From both rims of the heart and soul

پیدا و نهان چهچه بزنی

You gently tap, visible and invisible

گل می گذرد، گل می گذرد

In the blink of a blossom

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad

with edits by Parween Pazhwak

= = =

The poem conveys a true connection with a loved one, her "cluster of light”— the poet speaks of a blessed experience gently grazing her soul and heart, but the moment rapidly fades like a bed of seasonal flowers (گل می گذرد).

Farzaneh Khojandi, born on November 3, 1964, in Khujand, Tajikistan, is a noted poet with several published books, and her works have been translated into various languages worldwide.

These lines are from Farzaneh Khojandi's collection "Poetry, Restore Me Once More," published in 2014.

Farzaneh Khojandi's collection "Poetry, Restore Me Once More," published in 2014.

See available copies

0 notes

Text

The High Fortress of Kabul

The High Fortress of Kabul

By Farhad Azad

Painting of the Bala Hissar by Sir Keith A Jackson (1840).

The Bala Hissar (بالا حصار), which translates to "high fort," is the oldest fortification situated in Kabul. It was home to the rulers of Kabulistan from the 5th century AD, most likely built by the Hephthalites, until the reign of Amir Sher Ali Khan in the 1870s.

It also served as the residence of Babar Shah (1483–1530), who established the Mughal Indian Empire during the early 1500s. In his memoir, "Baharnama," he documented his life experiences and quoted the Timurid prince and ruler of Herat Badi' al-Zaman Mirza (بدیع الزمان میرزا):

بخور در ارگ کابل می، بگردان کاسه پی در پی

که هم شهر است و هم دریا، هم کوه است و هم صحرا

Drink wine in the castle of Kabul and send the cup round without pause

For Kabul is mountain, river, city, and plains in one. *

Over three hundred years later, the invading British army partially destroyed the fort, which was soon abandoned. Amir Abdur Rahman (r. 1879-1901), who the British installed as an agent monarch, constructed a new center of power, the present day Arg of Kabul. During the 1900s, the national army was stationed in the lower part of Bala Hissar.

I had a unique opportunity in 2002 to explore the upper portion of the fort. While hiking around the area, I encountered a tank manned by two timid soldiers. The graffiti in Farsi written on the side of the tank read چشم بد دور ("ward off the evil eye”).

From the top of the towers, one could appreciate a breathtaking panoramic view of Kabul, which was still in ruins from the proxy war of the previous decade waged by the Islamist factions.

The fort remains an important archaeological site. In 2020, the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) began restoring the walls at the site. The fort was set to be excavated by the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan. It is unknown if any further progress was administered since the announcement.

* Translation from Annette Beveridge’s translation of the “Babur-Nama” (London, 1921)

0 notes

Text

نمیدانم چه بنوازم! I do not know what I should compose!

نمیدانم چه بنوازم!

I do not know what I should compose!

قهار عاصی

Qahar Asi

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad

With edits by Parween Pazhwak

نمیدانم چه بنوازم

I do not know what I should compose

نمیخواند به اندام فریبای غزل، سازم

It does not harmonize to a ghazal’s deceptive sculpted body

نمیدانم چه بنوازم

I do not know what I should compose

بلای استخوان سوز جدایی

the bone-chilling pain of separation

راه وا کرده ست بر جانم

has unlocked a path into my soul

نه سر از پای میفهمم

I do not know my condition

نه راه از چاه میدانم

nor do I know the passage from this hollow

به عنوان کدامین درد

from which guise of pain

بیتابی خود را

my relentlessness

در سرودی رنگ پردازم

shall I color a hymn

نمیدانم چه بنوازم

I do not know what I should compose

- - -

I came across these lines from my first book of Qahar Asi poems, ''آرمان'' (Desire), which I had gathered back in the late 1990s.

These lines hold a certain mystique in that one can assume that the poet's creative spark has momentarily gone astray for the lyrics of a song to emerge in the form of a ghazal, the form commonly used in the Kabuli ghazal compositions.

In the 1980s, radio singers sang his words, but now, a yearning for a lost love permeates his verses. And yet, ink pours forth from his pen as he endeavors to shape a lyrical format. Alas, the "relentlessness" and "bone-chilling pain of separation" still linger.

— Farhad Azad

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Majrouh's Midnight Traveler prologue (continued)

Midnight Traveler

prologue (continued_

By Sayd Bahodine Majrouh (1928-88)

English translation from Serge Sautreau's French translation from the original Farsi

At dawn,

every household had fled.

No tumult, no disturbance, neither the city nor even

its echo from the deepest in the soul.

I was drowned, oh silence!

The path in the night seemed to glow

and now the day offered

the gaping and mute and black mouth

of a cave.

Thus opened the doors of night.

Clarity, an unknown day that reveals itself

We live in a strange world: below me, the plain

burning, thorns, and brambles crossed

overnight.

Not far, the bed of a torrent, dry

from the origins, a fossil snake

through the rockeries.

Black mountain ranges, frozen,

in serried ranks, straddled the horizon.

And, very close,

the dark entrance, the worry

of the cave.

Silence, petrified the world, suspense —

and plain, rocks, mountains, a dark mouth, everything

seems to be holding its breath as if in expectation

of who knows what is imminent, inhuman,

irremediable.

Silence - deep silence.

And calm – intense calm.

Just before

the cataclysm.

- - -

In this passage from the Midnight Traveler, Majrouh vividly describes a land descending into darkness, haunted by monstrous beings reminiscent of Shahnamah tales.

These creatures, dwelling in caves, seek dominance over the people.

In essence, Majrouh foresaw a future where glorified, Western-supported Islamists would spread their draconian vision (“inhuman, irremediable”), casting an eternal darkness with no dawn in sight.

Tragically, Majrouh was assassinated as he opened the door of his home in 1988 by henchmen of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

0 notes

Text

Dust خاک

خاک

Dust

نوذر الیاس

Noozar Elias

در شبی توفانی

On a turbulent night

باد و باران بیابانی

the desert wind and rain

خواهد برد

دانهها مان را

shall carry away our seeds

سوی کوهستان

toward the mountains

تا بروید جنگل

to grow into a forest

از دل هیبت کوه

in the grandeur heart of the mountain

تا بجوشد خورشید

where the sun boils

از تۀ غربت سنگ

from the harsh depths of exile

تا بماند انسان

for a human to remain

بر بلندای زمین

on the summit of the earth

جاویدان.

eternally.

۱۳۶۳

1984

This piece is from Noozar Elias’ 1997 collection of poems, “In the Middle of the Night” از میانۀ شب published by Expanded Freedom Publishers, Toronto, Canada.

Painting circa 1600s school of Herat

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad, summer 2023

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

سوخته لالهزار من

My tulip garden has perished

سوخته لالهزار من

My tulip garden has perished

استاد محمدحسین سرآهنگ

Ustad Mohammad Hussain Sarahang (1924-83)

شعر بیدل

Poem by Bedil (1642-1702)

سوخته لالهزار من رفته گل از کنار من

My tulip garden has perished, the flower has departed from my side

بی تو نه رنگم و نه بو، ای قدمت بهار من!

Without you, I have no hue, no scent, o’ my hoariness spring!

In 1981, there was a concert at the Goethe-Institut (گويته انستيتوت أفغانستان) in Kabul. A film crew from Radio-TV Afghanistan (رادیو تلویزیون ملی افغانستان) heard about the event and recorded it. This concert may have been the last public film recording of Ustad Sarahang, who was facing health problems then. He passed away in 1983.

Translated from the Farsi by Farhad Azad, Aftaab Magazine

2 notes

·

View notes