Text

Number 8 from Stranger Things Proves why Marvel vs Capcom needs the X-Men back

Stranger Things 2 is pleasant — more enjoyable than its predecessor — but it doesn’t get interesting until Chapter 7: The Lost Sister.

Spoiler Alert — Eleven means Number 11. Like, there’s 10 more psychic experiment kids. In The Lost Sister, El travels to Pittsburgh to meet her long-lost older sister, Kali (No. 08). The story goes full-blown X-Men, and is all the better for it.

Stranger Things has long flirted with X-Men allusion. The first season was peppered with references to the comics of the 80s that the boys would loan each other. (X-Men may even explain some of Lucas’s hesitation to include Eleven in the party: the legendary Dark Phoenix run, in which the team’s most trusted telekinetic goes nuclear and starts snapping necks and swallowing planets, came out in 1980).. And of course, the whole naming-mutant-kids-by-number thing is instantly evocative of Weapon X — I wonder if, in season 3, we’ll meet No. 10, a hairy lil kid who heals super fast?

But The Lost Sister rockets past mere reference and into the realm of glorious, thematic homage. Kali and her hilariously 80s band of wasteoids remind Eleven that they have been rejected not only by friends and family, but by society as well. Kali and Eleven, and to an extent the rest of Kali’s gang, are abandoned due to their difference, or different due to their abandonment, and only here, now, in the ruined underbelly of the city, do they find some sense of belonging — “home.”

This theme is compelling, and carries with it the implication of actual emotional impact (rare for a series which often doesn’t try to hard to make the viewer feel actual feelings — the most we get is feeling slightly sorry for Steve as he realizes he won’t be together forever with this high school sweetheart). This is because “superpowered-runaway-kids” calls upon the deep cultural mythology given to us by the X-Men, with narrative markers that instantly signify the existence of deep, messy, and complex feelings about identity and society.

The Lost Sister shows us young people on the brink of womanhood, coming to terms with their own burgeoning power. “Your policeman… stops you from using your gifts?” Kali asks. “We’ll always be monsters to them.” Eleven nods. She knows it’s true.

The scene is sparse, now overwritten by virtue of the fact that it simply doesn’t need to be. Instantly, the storytelling device of “psychic kid” functions as metonym for any number of things — burgeoning sexuality, identity, deviance — and we can take the omnipresent (Police)Man to represent any number of things — fathers, or men in general, or our society at large.

It’s a conflict as old as time — or, in this form, at least as old as the 60s, when the X-Men debuted, and 70s, when Stephen King wrote Carrie. King, one of the central inspirations for Stranger Things, wrote in his 1980 novel Firestarter, “The pituitary gland… during early adolescence it dumps many times its own weight in secretions into the bloodstream. It’s a terribly important gland, a terribly mysterious gland… the change in the pituitary gland may be a genuine mutation.”

Floating throughout our pop culture consciousness is the understanding that teenagers are, in some sense, mutants. Aberrations. They yell and scream and shatter glasses and plates, sometimes with their minds and sometimes not. Their minds literally expand, unfold, flower, and their flowering necessarily threatens the natural order.

The natural enemy of the Psychic Kid is, of course, the (Police)Man. Again, parents, authority, the state — each seeks to instill order, where the Psychic Kid necessarily represents questioning and chaos. What makes these narratives compelling is that each person in the conflict attempts to abide by what they believe to be justice. How each character responds to violence, and attempts to instill justice, is influenced by their background and positionality.

When Kali and Eleven threaten mortal justice upon a man that once tortured them, we are forced to confront the same questions that youngsters always make us confront: What is right, and what is wrong? What is so important about the lives of the men who came before us, and the flawed world that it built, that it deserves to survive? Who am “I”? What is home? Is home the stifling place and people that raised me, or is home the people that celebrate me, make me feel safe and strong, think and look and act like I do?

^this dude is no Sally Yates

This subtext makes The Lost Sister arguably the best episode in the series, and elevates the story to new realms of commentary and emotionality. Moreover, it does so without hours of story. Instead, it creates tension through arranging characters with different interpretations of justice in concert together, through tropes of Psychic Kid and the (Police)men.

Marvel vs Capcom Infinite (MvCI), however, relies on 80+ minutes of cutscenes that ultimately lack that same inherent ideological tension.

MvCI, the latest in the venerable Vs fighting game crossover series has widely been regarded as a total disaster, even by its most devoted players and fans. While the mechanics of the game are sound, the game feels slick, shiny and hollow, and as evidenced by the outcry on comment sections across the internet, this hollow-ness is due, in large part, to the absence of the X-Men.

The game instead touts a sprawling story mode that attempts to flesh out how the characters interact and why they’re fighting. But thecinematics fail to accomplish what The Lost Sister does in 45 minutes (and especially, within their three minute conversation between Kali and Eleven), which is to evoke emotion-- again, emotion derived from divergent interpretations of justice. Marvel’s usually dynamic heroes here feel strangely one-note.

Pro-player-turned-game-designer Combofiend tried to minimize the absence of the X-Men in MvCI, dismissing characters as “functions.” But characters are characters, the building block to any powerful tale and the vehicle to any deep emotion. In fighting games especially, which function off a lack of structure and incessant fast-paced action, compelling characters are necessary to deliver some sense of story. Ironically, stories don’t create a story — characters do.

Players criticize the lack of character diversity in MvCI. This isn’t just a reference to their playstyles, though 20% of the characters being gun users is a bit boring. Rather, this critique extends to the characters themselves. Many characters in MvCI (Captain America, Winter Soldier, Chris Redfield) are, like Hopper, glorified (Police)Men. And I say this as a Captain America fan! But as a Cap fan, I recognize that Cap, like most characters is at his most compelling when he conflicts ideologically with others. Without the foreboding and subversive Magneto, or the volatile Phoenix, or the proud and powerful Storm, MvCI feels like a bunch of one-note, authority figure heroes clashing over nothing. The action is devoid of any drama.

Authority Figures vs Authority Figures Infinite

Simply seeing an X-Man on screen calls to mind all the aforementioned themes, themes that Stranger Things was able to inject into their story by including Psychic Kids. In a Versus series game, a game which earned its stripes through careful, loving representation of characters, the decision to not include some of Marvel’s most evocative characters feels absolutely stupid — a rejection of the powerful legacy that Marvel has helped create, a legacy that everyone else in media has learned to capitalize on. Now that Disney has acquired Fox — and in doing so, united the film rights for the X-Men with the rest of the Marvel Universe — Capcom has every reason to re-include the X-Men in MvCI, and no reason not to.

Unlike what Combofiend said, characters are not simply “functions.” They mean something. Scratching a cross on a bit of wood is instantly evocative. So too is including Wolverine in a piece of media. We’re not looking for just another drill-claw function, we’re hungry for someone whose very image brings with it questions, whose existence tells a story.

#article#editorial#marvel#capcom#marvel vs capcom#gaming#video game#x-men#stranger things#fox#disney#essay

0 notes

Text

Have you ever actually tasted bittersweet? (2016)

I love the little ways you trembled

I love the sideways ways we slept

0 notes

Text

And Then/That’s It

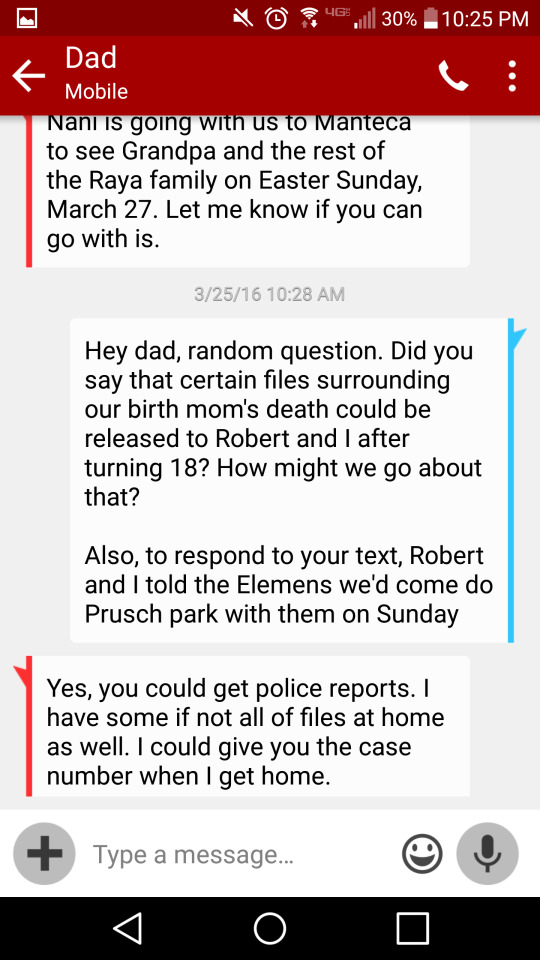

I recently asked my dad for help getting further information regarding my mom’s 1998 murder.

When my brother and I discovered the truth, when I was 10, we were told the case was not entirely “closed,” that the killer, upon killing himself, left behind a note that implicated the existence of an accomplice. That note was something that the police would release to me and my brother upon turning 18. Until then, Dad said, it was a “cold case.”

I’m 23 now. 18 came and went for Robert and I and we never once discussed going to the police. Partly because college, I think, kept us so busy, and saying goodbye to our first loves for what we thought was forever… we had little else on our minds. Partly, I think, because we didn’t discuss it much, with dad, mom or anyone. Mostly with mom, which both was and wasn’t odd. But also I think because, for me at least, I couldn’t tell if it was real.

Apparently many stories I remember from that time, from 5 to 10 years old, aren’t real– or so my mom says. I made them up. I can see that. I’ve always liked having good stories to tell. So, I wasn’t sure if the whole thing, about the suicide note and the 18 years old, was something I dramatized, to give some sense of presence to the whole case, and thereby agency to myself, to one day being able to interact with my mom’s murder on an adult scale. Cuz the story definitely smells dramatic. It does. It reeks.

But I live in San Jose now. I feel strong, now. As strong as I ever have. And, yeah, “adult.” So I figured, with only a few months guaranteed living here, I might as well look into it.

I texted my dad.

It was weird. All I wanted was a name, a phone number. Do I call San Jose Information or San Benito Sheriff’s Office? Coroner’s or Record’s? That’s it. Not some whole big thing. But these “files.” I felt like I’d seen them before. And didn’t really need to see them again.

Dad was so weird about it. He was. He kept asking me when I wanted the “files.” I kept saying “whenever.” I figured just one autopsy report with a case number on top to give to the cops would be good enough.

I went up to Berkeley Friday night, hung out with Robert and Chase and Tito at Tito’s place, then with Eugenio, then finally, with Robert, at home, at Dad’s.

I woke up early Saturday, hid in Nani’s room til Dad and everyone left the house. Mom called. She was surprised to hear I was in Berkeley, since I’d been spending Saturday mornings in San Jose to go to free therapy my job had offered.

“Do you talk with your therapist about your girl problems?”

“That’s actually her specialty, so yeah, all the time! It’s really great.”

“Does she tell you that you keep choosing these terrible girls because you’re depressed and self sabotaging?”

“No, she actually has a theory that I am drawn to hyper-emotional and somewhat involved, dependent women and relationships because of the complete emotional distance and abandonment by the other women in my life.”

It’s not fair to say, even if it’s true. I know my mom’s wincing on the other side. The phone’s quiet.

“Richard–”

“That wasn’t fair to say. Well– it was, but– I mean, she wasn’t even really talking about you. Really she simply identified that having a mom who chose a life of drugs over her kids– then, y’know, died– must’ve been really hard for me. And just, the little she knew about you, the little I had shared, folded into that.”

“What have you shared about me!”

“Nothing!”

“Rich…I tried, Rich!”

“I know!”

“You were just very hard for me. Some things about your personality, I just couldn’t deal with. Not now, though. Now, you’re just rude, and don’t do what I tell you, and think you’re smarter than everyone.”

“… That’s what you hated about me then when I lived with you!”

“No, no, no! Well, yes. But also, you were very… anxious. I’m talking about when you were really little. I guess… cuz of everything you’d, you know, been exposed to. But you were very anxious. Like, sometimes you would just shove your entire fist in your mouth, just because you didn’t want to speak–”

“No… no, no no. You– you keep saying that and it’s– it’s not…! Whatever.”

“What? What’s not?”

“I’ve told you. Dozens of times, I’ve told you, like… I, I’ve said so many times, that’s not why I did the fist thing. I did it because a character in Grease, which I watched literally every day as a kid, did it, and I mimicked it, cuz I thought it was such an odd and like, interesting gesture. That’s it. And I’ve said this, repeatedly.”

“No… no, this was waaay back, when you were 3 or 4, like–”

“Yes, I know, and like I said, I was watching Grease. Every. Day. You know? It’s… I have an active memory of this.”

“Ok. Ok. Well… whatever.”

By the time I come downstairs Dad is gone. Robert, Nani and I spend the rest of the day chilling back at Chase’s. God, we had fun! N64 Pokemon spinoff games and Pokken and Wii U Party. Then dad texted:

So we went. But instead of everyone seated around the table, there was just cold meat on a plate and thick stiff corn cakes, Marisa upstairs putting the kids to bed and Dad who knows where. I remarked to Robert that it was stupid.

“Why.”

“Cuz– I dunno, when you get invited over ‘for dinner,’ I guess the expectation is, like, dinner. Like all together. Like I dunno why we had to come back for this.”

“Whatever.”

Robert and I heat up some more meat and eat. Then he heads to the living room and lays down on the couch while I sit. Eventually, little Johnny, my youngest brother, comes downstairs with his mom, Marisa, whining for food. She produces a plate she’d hidden away somewhere for him, mini corn cakes and veggies and some soy protein instead of the meat my brother and I ate. She goes back upstairs for some reason and I cut up some meat for Johnny, who smiles.

Dad comes in.

“Do you want those files now?”

“Uuuh, sure.”

He’s loud. He clunks into the laundry room and comes back with a padded manila envelope. On the back is a sticker:

RICHARD AND RHODA GOLDMAN SCHOOL OF PUBLIC POLICY

UC BERKELEY

Richard Raya

____ Martin Luther King Jr Way

Berkeley, CA

I blink, and smile at the folder. Seeing it is a trip. It’s like a time fold, like hearing those facts– Oxford is older than the Aztec Empire. Cleopatra lived close to the present day than to the construction of the pyramids.

1998. It always feels like there’s a before and an after, a here and a not-here. Before was San Jose, and living with my grandparents, and Dad with a cholo moustache, and no Leah, and after 1998 is Mom dead, and Dad as an intellectual, an auditor, and Leah as Mom, and life in Berkeley.

But that’s not how it actually was, was it? They were concurrent. They were both alive. Both my moms were alive. Dad was well on his way to getting custody even before Mom died, and we already lived in Oakland, and…. And it was just a trip. To think of all that. All happening at once. My dad, the grad student, the father, the guardian of two motherless children, the up-and-coming radical, the boyfriend to Leah the future lawyer, my future mother. A total trip.

He opens up the envelope and shakes it out over the table, among the shredded corn, among spilled cold meat. Folded newspapers clippings and grainy online article printouts spill out. Across the table Johnny gurgles happily.

“This is everything I could find about it,” says Dad, rifling through the papers, splaying then stacking them like a 12 year old who just learned how to shuffle cards. “Most of these articles aren’t really online anymore, nothing is really online cuz that’s just not how they did things at the time, you know? But, there’s this… and this…”

I blink. Some of the articles I recognize from my own late night research. Some of the documents I recognize from files Mom inexplicably has. But many are new to me. And some don’t seem to be police,court, or news documents at all, just simple typed black text on white printer paper.

“My own personal notes,” Dad says, not looking up from the table but anticipating the question. He turns over more papers, and I see his handwriting– so like my own, loopy, blue– scrawled across news articles, post its, the inside of manila folders. “I wrote all these, you know– years ago– just for myself, you know… it was all sort of shorthand, I guess, but if you wanted, I could sit down with you, help you sorta decipher, y’know, what I wrote—”

“It’s OK. I think I can figure it out.” I picture dad typing up his notes on the family desktop, the same Mac we used to play Reader Rabbit and Math Blaster. When did he have the time to do all this? Who did he talk to about this?

“I just wanted to find some information,” he says, loud, fast, still fingering the papers. “For you guys. We didn’t know anything. I wanted to tell you and Rob something, you know, give you some information, just cuz—cuz I felt you deserved to know. I did. That’s just me. I did.”

I tune him out. It’s hard to listen, plus, I can tell he’s not really talking to me. His voice is high, tinny and

tight. He’s not really pausing for breath, he doesn’t stop flipping around the papers. He talks and talks and talks. He reshuffles the papers, flips them over, flips them back, rifles through. Pages flip by—tiny type on government-pink paper… faded green ink from a direct printout of an online article, the layout unmistakably clunky and 90s… a grainy picture of a man’s face, white dude, late 20s, dark hair in a close crew cut.

“The guy who did it, he tried to say, it was in self defense… it took them a while to identify the body as hers, because around the time there was this little girl that went missing, around that time–”

“I know.”

“Christina Marie—”

“—Williams, I know.”

“She went missing walking her dog—”

“I know.”

“Anyway. At first they thought the body they found, might be hers…”

He shuffles back through to the picture of the white guy and stops, folds papers back over it as quick as he can—which isn’t that quick—and looks back at me.

“Had you ever seen a picture,” he asks, “of the guy who… the murderer?” He bites into the word. Murderer.

“I mean… not until today, like, a few minutes—”

“Hooooo, Rich,” he says, shaking his head, looking back at the table again. “This… this is gonna be a lot to handle, man, reading all this…”

“I know.”

“His picture’s in here.”

“I know.”

“Have you ever read the police report?”

“You mean the coroner’s report?”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah—”

“Cuz there is some… it’s graphic. It’s pretty graphic.”

“I know.”

“You read this?”

“Yeah.”

“Where?”

“Mom showed me.”

“Your mom showed you?”

“Yeah.”

“You read this?”

“Yes.”

He pulls out the pink coroner’s report, then pushes it back into the stack. He hands me the whole stack—then takes it back.

“It’s graphic, Rich.”

“… I know.”

He thumps his index finger on his folder full of files. “There are still some images in here that I can’t get out of my head, that come to me in the dark, graphic things I’ll never forget.”

I think. Why is he warning me? I’ve read this before, or at least think I have—a surgical slash, lengthwise, along the entire torso? Or was it multiple stab wounds, to the front and back. A body partially decomposed. Detrophagic deterioration from squirrels, birds. I knew all that. Remembered all that. Or… I think I did. Why is he trying to scare me?

“I know.”

“You know?”

“Yes.”

“OK.” He looks at me, eyes a little wide and a little wet, smiling his little smile. It’s the same face he made when he thought Robert was lying to him about having sex in the back studio, the same face he made as he chuckled his way through me saying I wanted to stay at Mom’s house through the end of senior year of high school.

He strides past me, loud, into the living room, where Robert lay belly-down on the couch, thumbing his phone. Hearing Dad walk in, he buries his head in pillows.

“Rob.”

Nothing.

“Rob.”

“What.”

“Robert.”

“What?”

“Can you hear me?”

“What.”

Dad stands straight, as tall as he can, and thumps his folder once more. “I’m giving some files regarding your birth mom’s death to Richard–”

Robert speaks into the pillows. “OK.”

“And I just wanted to make sure you knew.”

“I knew.”

“You knew?”

“Yes.”

“How.”

“Cuz I heard you.”

“You heard me?”

I step forward, a little snort, a little smile. “Yes, Dad, we were just over here, not that far away, not hard to hear—”

Dad takes another step toward Robert. “I wanted to make sure you had the chance to look at them, before I gave them to him.”

“No.”

“No?”

Robert shakes his face deeper into the pillow.

“You don’t wanna look at these?”

I’ve been looking at Robert, but now I look at Dad’s back, brow furrowed. I suppress a snort. What?

“Nope. Can’t.”

“What?” Dad does his little wrinkled-forehead-smile again.

“Can’t.”

Dad’s smile widens to his canines, he steps in again. “You can’t?”

“Nope.”

“Why?”

“Cuz I can’t.”

“Why—”

“Dad!” I say. I take four steps forward, stand between the couch and him. “It’s ok.”

Dad tilts his head, his little fucking smile face frozen. “It’s ok?”

“Yes.” I reach my arm out, for the files.

“… OK…” He looks from Robert, to me, to Robert. He walks back toward the kitchen, pauses. “You gonna look at them now? Here?”

“Probably not,” I say, still standing by the couch.”

“You going to Chase and Tito’s?”

“Probably.”

“OK. Bring those files back, when you’re done.”

“Sure.”

He retreats. Robert turns his face toward me, keeps his eyes at my knee level. I bow my head.

“Hey,” I say. “I’ll probably head out. Tito’s, maybe Amy’s—maybe just home cuz I got work tomorrow. Cool?”

“Yeah.”

“OK.”

I take the files and leave.

Next morning, I’m at work, some B.S. career development shit—the kids don’t have school so we’re all crowded in the office downtown, doing some dumb fucking salary management seminars. But before and after lunch there’s “free work time,” so I go alone to the room with the little tables behind the kitchen and sit in the corner.

I take out the files.

People drop in, every few minutes. They ask about law school, or try to crack a joke while their lunch microwaves. I look up, smile, but then snap my head back to the files. Other co-workers even come in and sit at my table, eat their food and laugh loudly, but I stay reading. Stay quiet. Soon, they leave.

The pages are stuck together in weird ways, dog-eared and paper-clipped. That must be why, as I flip through, I don’t happen upon the picture of the man. I don’t end up looking at the coroner’s report.

I look at the articles, though. And I read dad’s notes. And I laugh, and shake my head. I lean back and rub my eyes.

Dad is so fucking stupid. Mom too, for letting him get way over his head. She’s a lawyer, damn it, she should’ve known better…

Dad wrote a summary of his meeting with Undersheriff Curtis Hill. I think back to when Dad had yammered on and on last night, to when I’d tuned out—Dad had mentioned that Curtis Hill was acting “like a big guy,” tough, like a big shot because his small county finally had some action. He said Hill gave him the runaround. Maybe it was because Dad was acting like a melodramatic macho man. Maybe it was because, as became clear through even reading Dad’s own notes, that there really wasn’t shit Hill could do for him.

Dad wanted access to the suicide note, for some reason— “for us,” he wrote on his paper. Wanted to unravel some big fuckin mystery. Hill informed him that was impossible, a) as the note was under the purview of law enforcement in Arizona, where the murderer had fled to by car before killing himself, alone, in a parking lot, with a single bullet to the head, and b) because the note was being held as classified evidence given the possibility of accomplices still being at large. Not wanting to compromise potential further arrest and prosecution, law enforcement refused to let certain information go public—standard. Yet Dad still seemed miffed that they wouldn’t release the info to him as “the boys’ guardian.”

Hill also informed Dad about the 20 year statute on criminal cases, noting that the case would stay “open” at least that long. Dad must’ve taken that to mean… well, I don’t know what he thought that meant. But what he told us our entire life was, again, over dramatic and factually inaccurate.

Yes, Robert and I could access evidence about the case when we were 18, but so could Dad, as well, or anyone, really—provided the case was closed. Or, even if it remained unsolved, we could all access it as soon as the 20 year statute period expired. Which means that if Dad really wanted to emphasize some age where the truth would be revealed to Robert and I it really should’ve been 25, not 18.

None of it mattered at all, though, because from what I could piece together from the articles, the case was pretty cut and dry. By 1999, Dad himself had already collected articles noting that two other San Benito county residents had been charged with aiding the murderer in disposing of the body. There was even mention of a third potential accomplice, some 19 year old girl, who the murderer had confessed to but then later told that it was all some story made up to “test her loyalty.” Weird shit, but nothing that had anything to do with what happened to our mom, and why. Law enforcement, both in Arizona and here, seemed pretty satisfied that they had found out just about everything they could about the matter. Which means the cases are probably closed. Which means all those years Dad worked to keep a secret from us, all those years he sat stewing believing only his precious sons could unlock the truth upon turning men—he could’ve just called up now-Sheriff Hill and went to read the damn note himself. Or, even if it somehow was still open, all we had to do was wait two years, til 2018, and then we could look at as much evidence as we wanted.

I laugh to myself. The sound, echoing off the yellow walls, makes the tiny room sound hollow. I run my hands through my hair. This is it? This is all there was to it? The past 18 years. This is all it’s been? There was no “mystery” here, not really—even the contents of the note itself seemed known, cuz that’s how the police were actually able to track down the confirmed accomplices. It took me, some kid who won’t even go to law school til next fall, about 30 minutes of my lunch break to set everything straight, to interpret all dad’s files with some modicum of clarity. I know mom could’ve figured it all out in a second. In a snap. Had dad been so obsessed with this case, with our birth mom’s death, with being the star of some sordid little narrative, that he’d kept his cards that close to his chest, that he hadn’t thought to ask his lawyer wife for help? Or did mom just not care?

Stupid. Stupid stupid stupid stupid stupid. Dumb. 18 years thinking this was the case to end all cases, the mystery of mine and Robert’s life. And any one of us could’ve open and shut this thing, the entire time. Nothing was hidden; closure was right there in the daylight, easy to find if only we had cared enough to look. And now, here I am—I can call Hill right now, if I want to, and put to rest the last little piece of mystery in our lives.

I don’t, though. Because here’s what I’m realizing: I don’t really give a shit. Neither does Robert, I’m sure. I don’t know that we ever have.

Everyone wanted it to be some big story. My mom’s murder—everyone needed it to be this drama. That’s why everyone wanted it to be Christina Marie. The news, even some pop stars at the time, all sounding off on the discovery of the body. They needed it to be this big, juicy thing—they needed this fucking story. And when it turned out to be some drug addicted, oft-unemployed, fat Mexican woman, instead of some beautiful little girl, they tried to keep it interesting. She left behind kids! The killer’s fled the state! There might be accomplices!

Dad, too, spinning some web for himself to get lost in, some conspiracy that only he and his intrepid man-children had some hope of solving. Mom, too, in her own way, always treating me and Robert like we’re broken.

I get it though. My parents were so young, when it happened. They were kids.Kids taking care of kids. They didn’t know what to do. How to feel. They were stupid. To keep going, they had to tell themselves stories. About our mom. About us.

The reality is those stories aren’t true. None of them are. The reality is that there really is no “story” there, at all.

Robert and I—our mom died. Her killer—he died. That’s it.

So what. So what if we never read the note. So what? Hell, so what if there is some unknown, fourth accomplice? Who cares? What, they’re gonna go to jail? Me and Robert will kick their ass? Who cares? No accomplice killed our mom.

And honestly, believe the dude, that to some extent it was self defense. Reports indicate he had recent lacerations on his body as well, consistent with being attacked with the very knife he used to kill our mom. I knew my mom. We all did. I really don’t doubt that, high and angry, knife in hand, she tried to hurt that guy. She made him fear for his life.

I’m ok with that. It reminds me… Last August, when I first moved back in with my grandparents, my grandpa—my birth mom’s dad—and I drove around San Jose, looking to buy me my first car. Driving home we talked about his oldest son, my uncle Moochie. Moochie is undoubtedly an asshole. We laughed, commiserated, fell silent for a bit. Our car crested Tully’s final hill, paused, for a bit, hot in the San Jose sun. My grandpa chewed his toothpick. Squeezed his eyes. Said:

“Yeah, we weren’t the best parents. Messed up. Our kids… do some bad things. Moochie… your mom. But… They’re bad, yeah. But I don’t think bad things should happen to someone, just cuz they’re a bad person.”

The killer, yeah, he was a bad person. Or did bad things. But so did my mom. So do all of us. Finding some sense or semblance of “justice…” that won’t bring her back, won’t fix anything. Throwing someone else in jail, hurting someone else—that won’t heal me or Robert.

And that’s the thing—I don’t think we even need healing. Need anything more to become whole. Because me and Robert? We’re good people. Good people. Not good like, so good we’re not “bad.” Cuz everyone is. But good, like, we have a lot, a lot of love. The way everyone can, if they try. My brother and I—we take care of our family, look after our little brothers. We’re nice. When someone’s in trouble, we help them, put our own time, bodies and reputations on the line, like when as a kindergartener I fought a sixth grader who was beating us up after school, like how despite the car crushes, the stealing and the drug use, Robert never stopped sticking up for Mateo. When kids bullied us, or bullied our little brothers, we don’t just use our fists, we use our words, our hearts, like when that one kid at that stupid little park near our house was hitting Nani, and I took him aside to talk to him about how important his choices were, and Robert sat with the other kids in a circle, talking in a low voice, making sure they were ok. We make friends for life. When those friends leave us, we don’t let heartbreak turn to anger. We stay open. We take them back, like how I still was ready to be Lawson’s best friend after she told me she never trusted me, like how Robert, after flying across the country to visit a girl, and seeing her spend the night with another man, didn’t take it personally, let her go.

Much as it might be hard for the parents and friends and family and therapists and social workers throughout our life to believe, me and Robert are good. We’ve dealt with it, and grown. We’re good fucking people…! And no one taught us to be this way. Not even Dad, really, and sure as hell not Mom. We taught ourselves. If there’s any story here, then that’s it.

Wasn’t worthless, getting those documents from Dad, though it may’ve been more trouble than it was worth. But I found some cool things. Found out, in an eerie non-coincidence, they had the same middle name, those two missing women: Candelaria Marie Elemen and Christina Marie Williams. Also found out that my mom, who I always remembered as tallest in the family was, according to the coroner, only 5’4”. Turns out she was small. Just like the rest of us.

There’s no “end” to this story. There’s nothing left to seek, or need, or find. I just want to go back to my mom’s grave, sometime soon—just the two of us, Robert and I. Lay on the grass, quiet. Watch the jets go by in that clear blue sky. And then that’s it. That’s it.

0 notes

Text

Dive (2015)

Let’s go walk

On that gentle beach

Where nobody is allowed to go

Let’s leave footprints

In the grey sand

And never let them wash away

Let’s find each other

In the lodge

Let’s remind each other

How we are warm

0 notes

Text

Wednesday (2015)

Leaving home at dusk the moon was gold

and low and fat over Grand

cut through silver mist

Walking back the sky is black

and the moon

high and cold

bathes bright snow blue

I feel this cold in my shins

still bruised from your box spring

and along the back of my ribs where

If I had guts

I’d tattoo your name

0 notes

Text

My Removal As Editor-In-Chief: How The Administration Failed Students

Originally published in The Mac Weekly on April 10, 2015

Earlier this semester I was removed from my elected position as editor-in-chief of The Mac Weekly by the administration for False Information and Failure to Comply. My final semester at Mac quickly became my most difficult — I felt abandoned by the people and the place that had nurtured me, that I had learned to love and that, I thought, loved me back. I was cast out from a group which I had grown and grown with since my first year here and The Weekly lost the leadership and experience of both myself and the fall editor-in-chief.

I wish to echo sentiments expressed in the Weekly’s courageous and powerful staff editorial published on March 6 — that the removal negatively impacted the paper, that the structures that facilitated this occurrence are outdated and exclusionary, and that viable solutions to prevent this from happening again exist, and can and should be implemented as soon as possible.

Throughout the semester I’ve been asked by friends, acquaintances and my Conduct Board itself if I sincerely thought I could “get away with it” — if I believed that somehow I might, despite administration objections, assume my position as editor-in-chief. That the administration might never “find out,” that I might escape unscathed.

My answer has always been no. As early as last August I knew that me becoming chief would invite conflict. Yet simultaneously, I have always felt as if I had no choice but to assume chiefship regardless. I was trapped.

Like every other editor-in-chief, I was elected democratically by the editorial staff of The Mac Weekly. Granted, I ran unopposed, but this is often the case in chief elections — the process more so indicates the approval of the staff of its chief. The integrity of this process is what I assume is referred to by the Weekly’s title as “Macalester’s independent student newspaper since 1914.” None may be made chief against their will, and none may helm the Weekly without the staff’s consent. I was thus the only one who could be chief.

And yet, as a student worker, I am eligible only to receive a certain amount of money from and work a capped amount of hours for the school. There is a stipend for the editor-in-chief, a stipend which, in order to receive, I would need to quit the Mellon Fellowship, in which I’d been working on a research paper since my sophomore year. Through the fall chief, I corresponded with the administration to discuss our options (I felt more comfortable and confident using the fall editor as mediator since, when I attempted to discuss similar pay conflicts between being a Mellon Fellow and an RA my sophomore year, I was unable to even secure a face-to-face meeting).

I volunteered to be chief for free. I was told this was impossible. We tried to ascertain the nature of the stipend money, who it belonged to, where it came from, and if the Weekly could liquidate it into resources for the Weekly as a whole, perhaps to purchase snacks for staff or add more pages in color. Again, we were told this was impossible. Through it all I never quite understood why.

The fall chief, ineligible for work study, exceeded the hours-worked-cap by being chief and a TA all at once, receiving two paychecks from the school. The administrators admitted that, while this technically broke the rules, they would allow it. Similar situations occurred across campus, for example, in the case of paid positions with WMCN. But in the case of me, a student actually eligible for work study, it wasn’t allowed. It was forbidden.

The administration demanded someone be paid for editor-in-chief. I was ineligible to be paid. Yet I was the only one chosen to be chief by the allegedly independent paper. It was a triple bind. The only way forward, the fall chief and I decided, was to let the administration continue sending checks to the fall chief while I performed the duties I had been elected to do. Within a month the fall chief and I were subsequently stripped of our titles and barred from the Weekly, even from entering the office.

What do these rules, and this outcome, mean for student voices at Macalester? Time and again, throughout this saga, the editor-in-chief stipends were touted as a means of making it easier for students “of a certain background” to serve as chief. In practice, however, it has done the opposite.

As it is now, the pay system surrounding editor-in-chief forces any student receiving work study to, for the one semester they will act as chief, quit their other on-campus job. By the time they are a junior or senior, eligible to assume the role of chief, many work study students have worked their way into higher level jobs not easily left behind. Would an RA be expected to leave their community behind midway through the year should they be elected chief?

The Mac Weekly operates as a public forum for the community. As its leader, the editor-in-chief plays a large role in making that discourse accessible to the public. What does it mean that the editor-in-chief is, most likely, not a work study student? What does it say about what types of student perspectives are represented when the editor-in-chief can never be an RA or a Mellon Fellow?

The fall chief and I have long been aware of The Mac Weekly’s diversity problem. Our staff, like Macalester itself, is largely white and upper-middle class. Over the summer the fall chief and I met with DML staff to brainstorm ways our paper could be more accessible, equitable and inclusive, leading us to institute inclusive writing policies, revamp interview training, and assign “beat reporters” to the DML and other areas of campus. I���ve heard firsthand from many that the paper has done a better job of making more students feel included this year. Before my removal, I could foresee the Weekly someday turning into an inviting space for a wider array of students.

Not so anymore. I am a Mellon Fellow — an award aimed specifically at students of color. What does it say to younger/prospective students of color and students eligible for work-study that the first editor-in-chief who holds both of those identities was removed by the administration? It’s not a good look.

The sad irony in all of this is that I’m not even poor. Both my parents are homeowners and went to graduate school. Is our wealth gap here so dizzyingly deep that I am the first chief this has happened to, that even I, who in many ways have been groomed my entire life to assume a leadership position such as this, was deemed ineligible?

The application of these rules, although by the book, are also the most tangible examples of structural exclusion I have ever personally encountered — especially when contrasted with the lax enforcement of these rules for, among other students, the fall chief, who did not receive work-study.

Coming face to face with exclusionary structures is especially painful at Macalester. We all know that institutions are clumsy, impersonal and cold. And yet, institutions are composed of individuals. In this tight community, we know the faces of those individuals well. Through my roles as an RA, a speaker for This Matters at Mac, a member of Lectures Coordination Board and my participation in many orgs and events, I came to feel a great warmth for the individuals in the administration. That warmth has faded, however, as time and time again, over the past eight months I’ve felt dismissed, confused and severely unsupported by the administration, even as I struggled to find a way to make my role as chief permissible (again, I volunteered to do it for free). This has been, by far, my coldest spring at Macalester.

I’ve felt alone. I’ve felt bitter. I’ve considered many things — among them never leaving my room, and writing or speaking about this journey. I’ve felt like giving up on Macalester — on making it understand me, and finding a way to understand it. Yet still I write.

It is true that to give up on one’s community is sometimes an act of survival. But, if I’ve learned one thing through my struggles, personal, professional and academic, it is that to resign ourselves to accepting an unhappy home is in a sense a derogation of our own self-love. We always deserve respect and a chance to make our communities a better place.

Macalester’s students deserve the best independent paper possible, and The Mac Weekly deserves the administration’s support in creating that paper. As long as these exclusionary rules and stipends exist, such a paper remains impossible.

No one becomes chief for the money. We become chief because we love our peers, love telling the stories of our community. The fall chief and I interviewed editors-in-chief, past and present — none of us did it for the money. So why not do away with the stipend entirely? If the administration still feels the need to incentivize quality performance, why not make the chiefship something done for credit, or something akin to an internship? Why not give the Weekly a real staff advisor? If, as I was told by the administration, a student needs that stipend in order to act as chief, they could then apply to receive that stipend much the same way students on work study can apply for a paid internship.

Obviously there are logistics that’d need to be sorted out, but the Weekly, as the paper published by and for the students, can definitely be a special case. Perhaps more directly linking the editor-in-chief role with the internship program can provide greater clarity and oversight to the role as opposed to the messy and murky web of rules that govern it now.

The year is drawing to a close. Major players, both in the student body and in the administration, will soon be leaving Macalester. But I don’t want this issue to die. I know that the stellar staff of the Weekly will continue to ask the hard questions. I hope that those students and administrators of tomorrow will arrive next year willing to tackle this issue. Macalester needs a student paper it can count on, and the Weekly staff need to know that is respected by the administration — that the Weekly’s leaders won’t be plucked from its ranks mid-semester, that they can be trusted to do the jobs they have been chosen and trained to do.

Right now, Mac, we don’t look too good. We champion engagement and diversity, and yet our newspaper — a publication that can perhaps best represent our ideals to the outside world — has fallen victim to discriminating and unclear practices. If we change, we can be so much better; not just free of scandal but an institution that embodies its values, that produces graduates not weary, but proud.

But we can’t let this type of practice continue. We can’t have a paper whose will is overridden by administrative bureaucracy. We can’t keep taking our most passionate students, students who burn to share their unique light with their community through making bonds and telling stories, and freezing them out in a great, white cold.

0 notes

Text

Cycle Brake (2015)

After dinner we help your parents clear the dishes then split– you hold me by the hand, tight, and lead me back upstairs to your room. You shut the door behind us.

It’s the same room you’ve had since you were little. You’ve never lived anywhere else, except for when your dad was on sabbatical and the whole family went to Germany. You were 9, I think.

The blanket, and the desk with your computer and schoolbooks and pictures of your friends, are red. The walls and carpet are blue. Your headboard is soft, and patterned with rose vines, dotted with faded red and green petals.

You have a dimmer, and turn the lights down low. The blanket deepens to blood red, the headboard to black on white. It’s impossible to read the titles of all your books.You guide me to your bed, and we flop down, bouncing, messing up the covers. You pin me on my back, and I laugh. You smile, then clamber over me to your bedside table; you take your lighter from your pocket and light the candle. Vanilla.

“It’s crazy that your parents are so chill,” I say, propping up on my right elbow to watch you light the candle. “To just let me hang out here like this.”

“Yeah,” you say, shrugging. You lean your back against the headboard, and look out the window at the moon, which is blue and huge. “I think it’s cuz my sister had a high school boyfriend, and my parents saw it wasn’t the end of the world. Like, they see there’s nothing to fear.”

“That’s awesome.”

“Yeah.”

I scoot to the head of the bed and sit next to you. I pull my legs up in a triangle, and rest my hands on my knees. You sit cross legged.

I look around your room, breathe in your candle some more. I love it. Seeing where, and how, you grew up. Something about it electrifies me, as much as I’m electrified when you show off your tan, Cali-girl skin in jean shorts and your royal blue top. There are pictures of your parents on your desk. Post-It notes to yourself on your computer. To the left, by the door, a floor length mirror, taped up with pictures of your friends making duck faces at the camera.

And on the floor by the mirror, my backpack. I breathe a little quicker, and it’s hard in this vanilla heat. I remember the condoms in my backpack.

We’ve been trying for about a month now. I can’t stay hard. It’s hard to keep you wet. No matter how much I kiss your breasts, or lap between your legs.

There’s something, about the nerves— we just can’t do it. We’ve strained and grunted and pushed and groaned and nothing. We skip school after lunch to try at my house, frantic before my mom or grandma might come home, and at the place you’re housesitting, feeding family friends’ cats, we roll around on the carpet— and nothing. Afterward, every time, we both hurt, and you’re sore. But we scan beneath us for the telltale drops of blood. And nothing.

I’m sore too. From track, from biking up and down the Berkeley Hills to your house, high over the city by Indian Rock, and from thrusting, thrusting, all the time, trying to break into you. My back and my butt and my tris and my arms, sore; and the pimples on my chest, swollen from the blood pumping through my body every day, burn. I don’t want to think about it.

“My parents fsho wouldn’t let me do that,” I say, still looking at my backpack and not you. “Have someone over.”

“Have me over.”

“I mean— anyone.”

“They think you’re at Tito’s right now?”

I shrug. “It’s my dad’s week right now. I dunno what he thinks. If he texts, yeah– I’ll probably tell him Tito’s, or something.”

I look down to my knees. I feel you shuffle about next to me; cross legged must not be comfortable.

“Why do you hate your dad so much?”

I look at you. You’re looking at me. You have a heart shaped face; bisecting it is your nose, long, almost like a squashed, inverted heart itself, tapering into your forehead and parting, like a delta, at the bottom. On either side of your nose, close to its bridge, your little almond sliver eyes are uncannily large.

“What?” I say.

“Your dad.”

“I don’t hate him—”

“Everytime you talk about him, you get so angry.”

“I do?”

“It’s pretty obvious.”

I snort and smile. You keep looking at me. I look out the window.

“I don’t hate him. I… am just sad.”

“… Do you hate Marisa?”

“Maybe.”

“You can’t hate someone just because they’ve had an easy life,” you say. Your voice is loud, almost too loud, I feel, for this grainy dark bedroom. “That’s not fair. It doesn’t make sense.”

“Well I don’t hate her for that,” I say. “I don’t think I really even hater her. I just am so confused as to why my dad would go for her. Well— not confused.”

“What do you mean?”

“Look,” I say. “From what I know about my mom— my birth mom— she was wild. Just galloping around San Jose, doing drugs and cussing out her parents… and, I dunno, writing poems and shit. And my mom, Leah, you know— she’s scary, right? She did law school and school for public policy at once, decided to adopt and raise two kids even though her dad just died…”

“Yeah…”

“To me, both my moms, both the women my dad has married before Marisa, seem like such warriors. And then Marisa? 10 years younger, country-clubbing Boston white girl? Who he seems too afraid to argue with cuz it’d hurt her feelings? It’s like… what the fuck. I just don’t get it.”

From downstairs I hear water, and voices. I think your sister is down there, maybe with her boyfriend. They turn on the radio. It sounds like sad ranchera. I keep forgetting your sister speaks Spanish. I can’t understand the words— they’re too far away— but I slide down the headboard to press my chest to the bed, try let the accordion vibrate up into my heart.

“Why do you need to understand why he loves her,” you ask. You stay sitting upright and look down on my face. “Why is that up to you?”

I blink. “It’s not,” I say. “But… I just wish I understood. Cuz to be honest I wonder if I do know the reason he’s with her. But the reason makes me sad.”

“The reason being…”

“I bet he’s tired. Divorced twice? One of his exes is dead? After the life he’s had? I bet that guy is ready to just not be alone. To be… taken care of, I guess. And if that means him being less… intense? Less confrontational, less… engaged… awake… then I think he’s ready to take that step. But it just saddens me. Cuz he taught me and Robert so much, about how to, you know, think, and fight, and feel. And he told us stories… read to us every night from his illustrated copy of The Hobbit from the 70s… I want to show you that book, it’s super cool.”

You smirk, but close your eyes. I continue.

“But yeah. He doesn’t read that to Nani. Hasn’t read him that, or The Chronicles of Prydain. And, I know Marisa wants kids… if and when they do have them, he won’t give those stories to those kids either. And will I relate to them? They’ll have a different mom, and kinda a different dad. So… yeah. All that kinda makes me sad, and angry, for my brothers and for him. His softening.”

I look up at you. Your eyes are open again, and you’re still smirking. You slide down to my level. The music from below resonates through our ears, hot and red; sitting so close together by this candle makes heat wrap around us like a towel.

“But you don’t like your mom, either,” you say. “Marisa never puts up a fight, but all your mom does is criticize. Marisa’s too soft. Leah’s too hard.”

I swallow, nod. “Yeah.”

“You just hate them both. Wish Candy was still alive, and your dad was still with her.”

“No.” I look at the ceiling, then away, at your closet to the left of your bed. My body follows, and I turn my back on you.

I breathe in, then out.

“No. I definitely don’t. For how much I hate her, my mom has made me. She’s the reason I can read and write and argue— she’s the reason I’m so bored in school. She’s probably the reason Dad and us stayed in Berkeley. What if we never had her? Where’d I be— San Jose? Still living with my grandparents? Not, not planning past high school— would I be doing drugs? Who fucking knows?”

Two tears pool in my eyes. I grit my teeth. I keep staring into the dark of your closet. Not at you.

But then I spin around to look you in the eyes and say:

“Of course I wish she was still here. I wish that every single day. But she’s not, and, and— I just can’t think that way. Won’t think that way. Obviously it hurts but it’s also made me me, and, and— I just can’t think that way about the past. I can’t. I won’t.”

I turn away again. Clench my jaw, and my fists. I try not to tremble, and try not to let the tears fall. They do. I don’t breathe in, and don’t breathe out; I try not to let the tears fall.

“I’m sorry.” you say.

I hold my breath. Downstairs, your sister laughs. She changes the station. I recognize the slow, synthy intro, By Your Side, Sade.

“I’m sorry,” you say. “I shouldn’t have said that. I know how you feel.”

I cough out a sob. You must know I’m crying now. I feel your hand on my back, and you scratch, slow, up and down, through my shirt. Another sob tumbles out.

“You… do?”

“Yeah. About Nick.”

I turn, tearless. I’ve never heard you talk about him, at least not willingly, and especially not to me. All I know about him I’ve heard from your friends in apologetic whispers.

“About… him?”

“Yeah,” you nod, and sniff. “Sometimes I hate how much I cared about him.”

I nod, encouraging. You’re laying on your side, head resting on clasped hands, eyes cast to the ceiling. You continue.

“How much I still do care about him.”

I stop nodding.

“How I still worry that something might happen. To him. And that it might be my fault. Even now… here, with you… I worry. And then, of course, I hate that I worry. Because he’s lied so many times. And I fell for it. every time. I really thought that he was going to die. And that it’d be my fault. And then just ended up feeling like a fool.”

My breathing speeds up, I reach for your face with my left hand but you catch it, clasp it tight, and keep talking, keep looking up and away.

“And he probably will keep telling those lies. And maybe one day it won’t be a lie. But I’m trying… to not let that… control me? And not feel like his life is my responsibility.”

“It isn’t—”

“But here’s the thing. As much as I know I can’t let myself be pulled into that. I also know I can’t hate how much I cared about him. For him and about him. Right? Cuz, what was I supposed to do. What am I supposed to do? I did what I thought I could, what I thought was right, and I can’t let some… bad… experiences… make me hate that part of myself?

“Because,” and you look back to me, “if I hated that, and thought I was stupid, then I’d have to think I was stupid for wanting to risk caring about… someone…. for caring about you.”

I’m silent. I look to your hand holding mine. The flame has slid down the wick and now burns from deep within the candle, instead of a pure orange flame the room now dances in a filtered dark gold. Vanilla fills my lungs.

“It’s the same with my dad,” you say.

I furrow my brow. “How?”

“How old is your dad?”

“Just hit 40.”

“Right. My dad is almost twice your dad’s age.”

“Right…”

“And I can’t stop thinking about how he’ll die. Like, we all die…. but he will die. It’s just a fact. And I… feel… so scared. And so selfish. And angry. Like, he won’t stop smoking. He won’t stop eating pie and red meat. And I’m like, do you want to live? Do you want to see me get married? Have a kid? Or are you ok leaving me and mom and Beth alone?”

You’re not looking at me either, but at our hands, as well. I run my thumb across your knuckles.

“But then I remember,” you say. “To breathe. And I remember: you can’t change people. And you can’t change the past. And things will happen. What’s gonna happen will just happen. And that fear… it’s… natural? Right? But also… it can’t… hold us back.”

You look into my eyes. We’re holding our hands. It’s sweltering in the room now but our bodies have inched so close. Your eyes shining, I can’t tell if you’re crying or not. I can’t tell if I am either.

“That fear can’t hold us back.”

You kiss me, and neither of us closes our eyes. You shift your weight, rise; swing one leg over me and straddle me, put your hands on my shoulders like you did when we first came into the room, laughing.

“I’ve never heard you talk about those things.”

“Yeah.”

“I’m surprised… usually, you seem afraid. Those things… are scary.”

“There’s no reason for us to be afraid of our past,” you say. “We don’t have to be ashamed. What we’ve done. Where we’ve been. Crying… we should be able to talk about those things that scare us. To look at them, share them… It’s ok.”

I tuck my fingers beneath your chin and cup your mouth to mine. We kiss. We kiss, deep, and your hands leave my shoulders to lose themselves in my hair. I run my fingers up along your legs, rest them on your hips.

We kiss. You press down on to me, your legs, long, squeeze mine; your breasts, heavy, weigh on my chest, and your hair, thin, soft, encircles my face. I know nothing but you.

Our clothes fall away like feathers, line the floor around your red bed. The candle is nearly out but the moon is high, and nearly full, and all we see are outlines, glinting silhouettes. The sweat tracing your shoulder is silver, the low light overhead bathes us in dark gold.

Above me, your face, your breasts like two crescents. You move. Your hips, flowing over me, through our underwear feeling out my stiff ridges, like the way the Bay’s placid tide licks at the Marina rocks. You pull me up and I guide you forth, then back, then to me again. We kiss.

“Should we…” you say.

“I don’t know.”

“I want to.”

“Ok. Do you have…?”

You nod. In one motion you step from me off the bed, to your dresser by the closet. Light blue. You slide open the top drawer, start tossing out socks and underwear, burrowing, rooting. I watch you. Your smooth back in the half light, you balanced on your toes, your thin, strong ankles. You’re a dancer.

You shut the drawer, wave a small blue square at me. A Lifestyles condom. We both smile, and you hold my gaze. You bite your lips. Your thumb flirts with the waistband of your underwear– and then you push them down, your smooth legs grazing past each other as you step out.

I suck in air, blow it out. Realize my breath is even. That I’m full of light.

You straddle me once more. Kiss every one of my abdominals. I flex, and thrust forward, so you can pull my boxers off over the swell of my butt. We put the condom on together.

And you position just above where I am, hard and tall. I feel your heat.

“Nothing…”

And you breathe out, as I do.

“To be…”

And you lower yourself on to me. Smooth.

“Oooooh…”

Our eyes are bright, and wet. Your breasts bob, in time, buoyed by my hands. You push at my shoulders, scratch at my collarbone. You roll into me, again and again, hips cascading down over mine.

And we hold each other. My arms encircle your back. You bite at my neck. I kiss just below your ear. Your hips, rolling. Mine, rising in waves. No seams. No rhythm. Just smooth. Same. Near.

I come all at once. I rush against you, in you. Waves. Like ocean in a shell my moans fill your ear.

I hold you. You hold me, too.

*

I lay in your bed with arms out like wings. Waiting for you to come back from the bathroom. I sit up, turn, straighten the blanket, rearrange the pillows. Pause.

Across your pillows, white with dark roses, and your sheets, white and soft like felt, are smears of red. I wipe at my back. My fingers come away red. The pimples on my shoulders, my back, long blistering and full, must have burst.

Before I can clean the sheets the door opens. You come in, loosely covered in your red robe. Your toes, nails adorned with chips of black, pad across your blue carpet.

“You ok?” I ask.

“Yeah…” you look at me. Your head is tilted. “I’m bleeding.”

I start. “Do you hurt?”

You shake your head at me. Smile.

“No.”

*

It’s 1 am. I’m just biking home. I’m smiling. I want to see my brothers. I know they’ll still be up, eating cereal, watching Supernatural, while the dogs snooze at their side and Dad and Marisa lay in silence upstairs.

I take one last look at your house as I roll down Shattuck, then make a right on Los Angeles, then a left, and I brake at the top of Mariposa.

I balance my bike. Squeeze tight on the brakes. Wind rushes up over the hills, hugging the roads’ curves. It’s cold– but I’m wearing my jean jacket, and beneath that, the hoodie you let me borrow to keep me warm. It’s red, and smells of you. Vanilla, and your floral perfume that never seems to fade, and something wholesome and sweet with a sour hint, like powder, or bread.

I breathe in. I let go.

Brakes and ground fall away, and I tumble into the shadows, and tree trunks whizz on by, and I let the darkness pull me, glide down like easy, and my bike’s tires hum smooth, cutting half circles across empty streets I go, shoulders light and free of shame and lungs hope high and full of truth toward home I go like blue on down the mountain.

*

Home, eating cereal on the couch. Nobody awake.

My brother comes downstairs.

“Sup..”

“Hey man!”

“You’re bleeding.”

“What?”

Robert gestures to my chest. I look down.

My white v-neck is ruined. Splotchy red, blooming out in a radial from my clavicle. Every single one of my chest pimples, knobby and hard for weeks, has burst. Popped.

“What’s that from?”

“My-- my chest.”

“Hurt?”

I shake my head, smiling a bit. “Nah.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ferguson: Destroy Fear, Infiltrate The System With Love, Fire

Originally published in The Mac Weekly, December 5 2015

It is clear that the enemy is racism. But, especially in these instances of killings by police, the vehicle of the enemy is misunderstanding and the engine is fear. This is what makes the killings not only possible but actually legal.

If we are to focus our energies on one thing, if we are to identify one central kernel, one core crux, of the recent killings, it is this fear—massive, old, nearly alive itself, pulsing with insidious hatred and thriving off of ignorance and xenophobia. A fear designed to keep us separate, scattered, alone.

In the grand jury proceedings Darren Wilson said that Michael Brown seemed as powerful as Hulk Hogan, that “it” (Brown) appeared like a demon. What other than the compounding effects of fear-mongering narratives could make a boy who refused to join football—because he was afraid to hit people—appear demonic and unstoppable, could instill in an officer, an adult trained in hand-to-hand and firearm combat techniques, a “reasonable fear” of an unarmed, twice-shot teenager dozens of feet away?

It is the same fear, the same stories, the same ability to dehumanize black people, that resulted in the multiple officers beating Rodney King to describe a “Hulk-like” strength, that gave George Zimmerman reason to believe he needed to “stand his ground” and slay Trayvon Martin, that gave our country the mythology of the superhuman, hyper-sexual, hyper-aggressive Black predator that lurks in the shadows of our communities and seeks to destroy our way of life. It is a fear that at least nine of 12 jurors were able to intuitively tap into and thereby believe that there was insufficient doubt to even hold a trial to determine that Wilson could reasonably fear for his own life. This same perception of Black people’s monstrosity let the jurors on Joe Pantaleo’s grand jury decide that the force used that killed Eric Garner was warranted, even necessary.

This is the fear, the distancing, the demonizing, that allowed policemen to report the shooting of 12-year-old Tamir Rice as the killing of a black man “around 20” years old.

This fear is an old and powerful enemy, and has been around since the birth of our nation—in fact, it was instrumental in it, was created to justify to our first citizens the inhumane treatment of African slaves, of indigenous peoples, of Asian immigrants. Ideologies of fear and dehumanization slithered serpentlike into the very legal and systemic fabric of the country. To deny this is not only expose a deep naïveté but also to be complicit in a system that hinges upon racial and other hierarchies, as well as demonstrate a severe lack of empathy on the part of those whom the system rewards.

We must remember that we are not alone, and we must value the work that has been done, that is currently being done, and that will be done.

Within the system, we can focus on these “reasonable fear” clauses. In all honesty they’re bullshit. What is reasonable fear to someone who has been raised on “thuggish” black men being humiliated on nightly news and on Cops? Does a system that allows “reasonable fear” to be determined by such a mindset result in “equal protection” for Black people, especially without necessitating the scrutiny of an actual goddamn trial? No. Let’s get rid of it.

But there is work to do outside the system as well—what moral imperative demands that people excluded by the law must submit to and preserve it? The very problem is that what has been happening to communities of color, Black communities specifically, is correct under the system.

There is no reason to be satisfied with laws written neither by nor for the people, nor to respect a social order which condones the racist marginalization of certain communities and bodies. A system that rules that the taking of Black lives based on dubious fear is not just. A system that allows Darren Wilson to literally profit from the killing of Michael Brown, from the dollars of citizens so twisted by fear, ignorance and overt bigotry that they laud him for getting rid of “another thug” or “gang-banger,” is not just. In high school, I had multiple classmates in my AP classes who claimed to not be racist yet confessed to crossing the street when a Black person approached on the same sidewalk “just to be safe.” A system that produces young people like this and then commends them as the “best and brightest” is not just—it has failed utterly.

It is a structurally unsound system, rife with hypocrisy and double standards, riddled with the sickness of prejudice, rotten to its core, reeking with histories of subjugation. We have seen how the system treats Black and Brown people. It is in many senses safer to avoid entering such a crooked house and to do work outside of it, operating from the margins and envisioning a new world to build.

Protests and public disobedience are powerful forces that effect change in the public consciousness, and we must support them. A die-in at Rockefeller Center or halting the BART system in the Bay may not melt the stony heart of the most ostrich-headed Americans, but it still does valuable work in activating the hearts and minds of Americans. If even one individual is inspired by the willingness with which demonstrators risk their lives under tank treads and hard batons, if politicians see that the only way to curry favor from their constituencies is to take heed of the voices crying out in anguish, and even if businesses recognize that in order to survive under youthful new paradigms they must support anti-racist causes, then demonstrations have succeeded in, little by little, shifting the tide of an America mired under centuries of racist legacies.

Beyond public demonstration, though, and beyond working to renovate our intentionally myopic system, I believe that anything and everything we do can and should be leveraged toward the awakening of the minds and hearts of mainstream America. I look at us passionate youth and see the next generation of chain-breakers and story-makers, the heroes on the front lines of the battle for the souls of Americans that are taught nothing but stereotypes and fear (remember, Martin Luther King Jr. was only 26 during the Montgomery Bus Boycotts).

The war on the bodies and spirits of people of color delivers its finishing blows in our justice system, yet it is a war prepped and fought in schools, in the market, and in the media as well. We can focus our energies on every front of this war.

The plight of people of color (Black people specifically) has always and continues to place those communities in a constant state of emergency in this country. In the fight for peace, respect and understanding, we carry both the curse and privilege of being drafted into the cultural wars, fighting for the protection of our communities. Our personal projects no longer belong to ourselves only but everyone we love and care for.

State-paid killers of people of color walking free drives home to me every day that our socially-conscious personal endeavors are not only commendable or assistive to a larger social landscape, but in a very real way vital to the preservation of lives of Black and Brown people.

If as a journalist you can create stories that show the multiplicity, complexity and integrity of communities of color, you must run them; it is a matter of life and death.

If you are an economist you not only should, but must, devote your considerable powers to understanding how we can create a just, equitable, and caring economic landscape, for it is truly a matter of life and death.

If you work within the justice system you must find ways to uphold and enforce laws equally and justly, and improve transparency and trust for communities of color; it is quite literally a matter of life and death.

If you have the talent to create art that forces America to confront and understand the humanity of Black people, you must, for in the aggregate it is a matter of life and death (if you can write a film or book in which characters must confront the tragedy of not only Black men but Black women and trans* people killed by whites and police, you must write it; it is a matter of life and death).

You must educate yourself and use your voice to educate those closest to you, in that way virally spreading the knowledge of truth about the humanity of your fellow human beings, Black and Brown communities, for the ability to empathize and stand in solidarity with oppressed peoples is a matter of life and death.

Remember—racism is a disease upon our world, one that takes the lives of people of color and fractures the humanity of whites. To survive, racism requires the shriveling of our empathy, our ability to understand the pain of our neighbor, our capacity to understand, to touch one another, to love. The antidote to that is the destruction of fear by the spreading of knowledge. By knowing you, we better understand, by understanding we can no longer fear. Perhaps then our Black and Brown loved ones will no longer be seen as demons.

0 notes

Text

Agave Americana (2014)

Last August, while I was home for a few weeks between the end of my Mellon Fellowship and the beginning of my junior year of college, I took a plant out of the ground in the front yard at my mother’s house.

“Ah, dang! That– that spiky plant? That cactus? Man,” my dad said, bouncing up and down and back and forth, slightly, his radiant little baby in his arms and his blond third wife beside him. “Man. I… I loved that plant, man. Y’know? So distinctive. I… yeah. I mean. I remember it. I liked it. Whatever– she’s paying you though? That’s cool. That’s cool.”

He was right. It was a distinctive plant, a cool blue green, starkly beautiful and without flowers, symmetrically ridged with serious spikes. Its leaves were broad and slightly concave, ending in blue-brown spires that flexed skyward. It kind of looked like a blooming onion.

The plant had been there as long as I could remember. We moved into that house, that duplex on MLK Jr Way, when I was five or six, when I started going to school in Berkeley. Eventually we left that house, but my dad retained ownership of the property. My mom’s dotty mom continued to live on the top floor, even after the divorce, and college kids lived in the bottom. Eventually, though, children and college and campaigns conspired to strap my dad for cash, and my mom, after her second divorce, was lookin to move back into a smaller place. In the true Raya way, my dad gave her the ex-family discount, and deeds were exchanged, the college kids were booted, and me, Robert and Nani now got to split time between our dad’s place, dogs and in-laws and community barbecues, and our childhood home, where project Leah-Wilson-Renovation was well underway.

To me, the plant had always seemed old, even when I was just getting used to it. Already massive when we first moved in, still now equal to me in height, I always felt that it was older than the house, maybe even older than Berkeley. Nearly a year later, during my time in México, I saw the plant again. I learned it was a maguey, specifically, agave americana. I learned that the maguey was a powerful plant, an ancient plant, a desert entity the old ones knew to love and respect. I learned the agave had the power to produce beautiful yellow petals, that when it blooms in full force it can produce a flower 25 feet tall– that agave bloom just once before dying, that if blossoming is staved off, if the stem is cut before flowering, a thick honey forms in the heart of the plant, that this honey gave the ancients a drink of magic and power, pulque.

Then, though, we knew none of this, knew that my mom and my mom alone owned the house, and that the agave did not fit within her vision: “No, no, no, I don’t like it, it’s too much. Get rid of it.”

Normally, I’d hafta to do that shit for free, but my mom, in that way of hers, noticed and respected, without understanding or empathy, the strange tenderness I had toward the plant, and offered me $40 bucks for my services. I wanted to refuse, but back at Mac I was learning just how much rent and milk and cereal and a girlfriend cost. Even then, I might have said no, but my mom made it clear this was an offer of love, that if I didn’t do it she’d call workers to come by first thing next morning. I guess we figured that it was better for me, and my dad, and the plant, if I was the one to destroy it, rather than strangers. This way, at least, I could spend some time with it, and get some money into the bargain. Besides, what else was I gonna do with my time? My friends all had jobs, full time, and, after college and my new girlfriend and everything else I’d done, I was no longer welcome at that specific house in the hills where I’d been spending all my free time since I was 17– indeed, even wandering the streets and sloping curves of Berkeley as I loved to do seemed too great a risk at this point. So I agreed to exhume the agave.

I lugged out from the rotting grey wooden shed along the fence in the backyard the tools my Grampa Lee left my mom– the long, dark, rusty hatchet, the pickaxe, the flat reddish shears. As I walked back to the front, dragging half my weight in iron, I noticed another memento of Grampa Lee, the large piece of driftwood he found that looked like a hippocampus, sitting in its own corner of the yard. Out of the two features in the yard that captured my imagination as I child, the wood got to stay and the maguey had to to go, even though there was room for both. I shrugged, already kinda panting. Made sense, I suppose.

I took off my outer shirt and, after a pause, took off my tank top as well, exposing my ruined chest and back. Crusty scars and fresh eruptions of acne dotted my flesh, which itself was paler than I would’ve liked after years enduring Minnesotan winters. Thankfully, my belly was more or less flat after a summer of intermittent push-ups and sit-ups, though nowhere near as lean and rippled as it was in high school. My biceps, however, rolled about reassuringly beneath my skin as I hefted the axe, and this heartened me, and I smiled. I had been hoping to catch some rays and pick up a last minute tan (in fact, hopes of regaining my old color just in time for back-to-school were a big part of accepting the job), but, glancing at the lukewarm sky while blanketed in the shade of the grey duplex, I clicked my mouth in disappointment; didn’t look like it was gonna happen. Oh well. I kept my shirt off anyway, hoping the open air and sweat would do some good for my complexion, and got to work.

I had forgotten what it was like to get lost in something other than doubt or memory. Despite the sad and sanguine nature of my work, I found myself grunting in pleasure as I struggled with my old friend, the maguey, firing on all cylinders, body, mind and spirit striking in harmony. I first used shears, and even the pickaxe, to hack at the leaves, which in our struggle seemed to warp and curve, rearing and appearing even more monstrous than usual. After about an hour, the longest and most inhibitive leaves littered the floor, broken spines tinkling across the brick path, and I swapped out weapons, picking up the shovel. I tossed the leaves into the compost bin and got to work on the packed, gravelly earth surrounding the plant’s base.

(If I had known about the maguey then, if I had known anything, I would have saved the leaves, and built a pit in the earth, and made a smokehouse with the leaves and smoked goat meat, or the head of a cow, and we could’ve grubbed on barbacoa, but this was then, and I didn’t know anything, and I threw the leaves away.)