Text

“The course at LFS gave me the confidence to go out and write and to get commissioned”

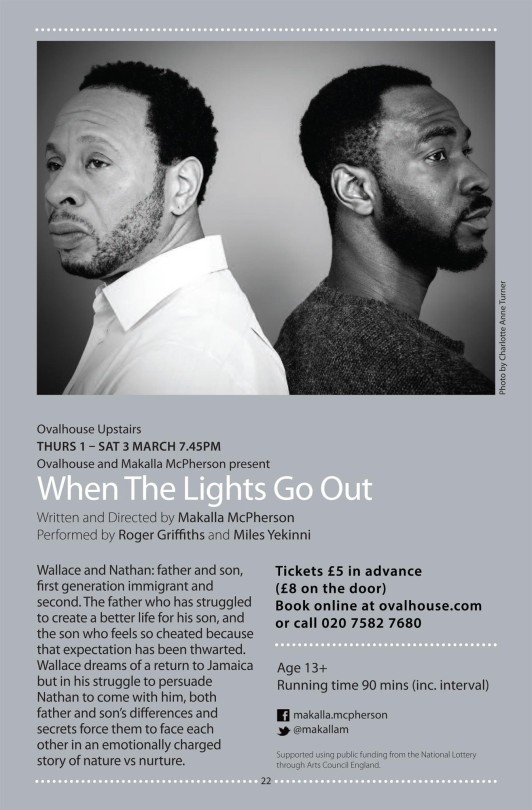

Makalla McPherson, who graduated from MA Screenwriting in 2016, will debut her first play, When the Lights Go Out, at London’s Ovalhouse theatre in March this year. Makalla, who is originally from London but now lives in Kent with her two children, wrote and directed the play after several years as a self-taught director who started out making music videos and progressed to short films and TV drama. Having originally enrolled on the MA Filmmaking program, she transferred to Screenwriting after being ‘blown away’ by one of previous Head of Screenwriting Brian Dunnigan’s lectures. She talked to us about the play’s themes, making the move from screenwriting to theatre, finding the confidence to write and what she learnt from her time at LFS.

Sophie McVeigh: What’s been happening for you since you graduated?

Makalla McPherson: Well, I’ve just done a four-month job for the BBC directing a children’s drama called Apple Tree House which will be txing this summer. Then, I got this commission for my play, so I’ve just been working on redrafting the script because we’re going into rehearsals mid-February.

S.M: Who was the play commissioned by and how did you go about getting the commission?

M.M: The Arts Council and the Ovalhouse theatre. I approached Ovalhouse initially about the play. They read it and got back to me and said they were interested and would support me getting funding through the Arts Council. They also provide a lot of in-kind support so it was an amalgamation of both the Arts Council and Ovalhouse.

S.M: How did you approach writing a play rather than a screenplay?

M.M: Ultimately, I just believe you’re creating characters and I think the principals are all the same when it comes to story and characters. The format’s different because you’re talking about stage versus screen. I read some plays and I read a lot about plays, and then I just decided to write my own.

S.M: What is When the Lights Go Out about?

M: It’s about a father and son – a son who wants to live his own independent life, a son that’s done everything right. He’s been to school, college and university, got all good grades, ticked all the boxes, but yet struggles to find work and find his place and identity in society. It’s exploring connection and communication. The son is just your typical person trying to move out of the parent’s house and find his feet. Then you’ve got the father, who has immigrated from the Caribbean and now wants to go back, but he’s brought up his son on his own and is worried about leaving him here in London. So, it’s a play about two men that live together and have grown up together, but yet they can’t connect, they can’t talk. Their perceptions of the world are different. And through Nathan, the son’s struggle to find his identity, he ends up having a breakdown. I was very much interested in exploring mental health within black men. That was one of the triggers for me with writing this play and the main theme that goes across it. I know quite a few men who have suffered and I wanted to know why. From my research, a lot of mental health problems in the black community, especially with men, is because they feel oppressed in a white man’s society. Whether that’s schooling, policing, education, work, housing … It could be a number of things. I wanted to explore that, but also it looks at generational differences, because the dad is almost 60 and the son’s 28. They come from completely different mindsets and have different generational perceptions of life. There’s also a bit of poetry, which was the way that I interpreted the son’s psychosis. It’s a play about people, ultimately, which hopefully covers a little bit of humour, sorrow and reality.

S.M: What did you gain from your time at LFS that helped you?

M.M: The confidence to write, because that’s something I was lacking massively. I’ve got dyslexia and I always liked writing, but it’s never something I’ve had the confidence to do. I thought, “That’s not me, I’m no Stephen King, I’ll leave that to the professionals.” But I do like creating stories as a director, and I have loads of stories going on in my head, so I think what that course did for me is to make me believe that I could do it and give it a go. I mean, I’m 11 drafts into this script and I started writing it as soon as I finished the course, so it’s been more than a year. And I think just learning how to create stories and characters. Even just the basics – the three-act structure, that sort of thing. And knowing that your first draft is not supposed to be a masterpiece. Before, I never would have got to 11 drafts. I probably would have just started the first few pages and given up. So, I think just knowing that masterpieces don’t come from one draft, that they are work. Even the best of writers rewrite, and like they say, writing is rewriting. It was Brian’s course at LFS that gave me the confidence to go out and write, and I’ve managed to get it commissioned. So, even if I never write again. I’ll thank LFS for that!

S.M: What’s coming up next for you?

M.M: In an ideal world we want to take the play to other theatre houses – bigger ones, as well. Only time will tell as to whether that’s going to be possible, but it’s nice to know, when you’re stuck in a room scrutinising your work that you’ve actually had the opportunity to have people come out and see it. I’ve got another play in my head, and a short film, so we’ll see whether those materialise! I’ve often pondered whether I’ll go back to my feature script that I wrote at LFS. Also, obviously, I direct, so finding my next directing job. I’ve got some meetings in the New Year. So, watch this space.

S.M: When is the play released?

M.M: March 1st, 2nd and 3rd at Ovalhouse theatre. Come down and check it out! The best £5 you’ll ever spend.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“I know that I’ve got a purpose on this Earth and I’m being used to fulfil it”

Ghanaian in origin, born in Ivory Coast and brought up in London, filmmaker and London Calling Plus winner Koby Adom ended up at London Film School after a chance series of events brought about by a single tweet. He talks to Sophie McVeigh about representing the worlds he comes from, avoiding categorisation and how LFS changed his life.

Sophie McVeigh: When did you graduate from London Film School?

Koby Adom: I graduated last July with my short House Girl. It’s set in Accra, Ghana, where I’m originally from, and it’s a story of a girl from the UK going home to Ghana for the first time. She experiences a “house girl”, and what that is, which is a young female domestic worker, like a maid. In Ghana, in some households, the treatment isn’t the nicest - it’s almost borderline slavery. So, I’m exploring that modern-day slavery theme and the African diaspora as well. This is obviously a global issue, but I’m tackling the topic using Ghana because that’s where I’m from. I’d like to encourage fellow Ghanaians to lead the way in tackling this issue, and then begin a chain reaction globally.

S.M: How did that relate to your background?

K.A: I was actually born in Ivory Coast, which is next to Ghana on the coast of West Africa because my dad was working there. I’m 27 and I’ve probably lived in Ghana for about a year and a half in my life. The majority of the time, my upbringing was here in London. I moved quite a lot until I got to about eight, but from 1998 forwards it was strict London.

S.M: What inspired the film and made you want to write it? Had you experienced anything similar with the culture shock of going back home?

K.A: Definitely, the culture shock was a definite factor. One thing I did know was that I wanted to shoot my graduation film in Ghana. When I was in 2nd, 3rd and 4th term, I was watching all these international students making their films back home in some beautiful landscapes, and I thought “Well, I’m not going back to my block to go shoot a film that everyone’s seen before!” (laughs) I wanted a different landscape, and I hadn’t been to Ghana at this point since about ’98, so 15 years. I remember, I went to Ghana in my second year of LFS just to look around and see what it was. I lived there, like I said, when I was younger, but it’s different now. It’s very modern, very westernised, which I didn’t know. So, I went there and reconnected with the land itself. It’s just a beautiful place and I made up my mind that I was definitely shooting in this country. The story itself came from something my mum told me, which was quite a dated account, and to be fair I didn’t stick to what actually happened. I know the full story, which I’m planning to make into a feature, but I just got a really small narrative from that to make a short. It was more of an exploration of the situation. I wanted to show people Ghana, and show them the topic. I wanted people to have more of an education on that matter and make up their own mind.

S.M: What’s the reception been like to the film and how has the festival circuit gone?

K.A: It’s been so good. It got into the London Short Film Festival, and a really cool festival in Nigeria called the Africa International Film Festival, and that was a big celebration of film. They put me into a really nice hotel and there was a closing ceremony with dancing and singing and glamour! It screened on four different continents. With festivals it can be about what boxes you tick as well as how good the film is, so I took it as a compliment that I got into some good festivals but not as many as I anticipated, simply because I’ve made a film that no one can categorise. And I love that! It’s not an African film that’s just based on the suffering of Africans. I’m not interested in that. I’m not interested in going to a place and complaining, you know? Obviously, the film is quite dark in parts, but there are parts where we show how beautiful Ghana is, there are some jokes as well. The auntie whose house we go to lives in a big house, bigger than anyone’s from my area in London. There is that side in Ghana, there are affluent societies. Don’t get me wrong, poverty is there. In Accra, the capital city, you see little kids hawking on the road, but I like to give a complete account of things. I feel like, in the main stream, a lot of people like to give very one-sided accounts of things, and it’s very frustrating when you’re from that background and you know there are so many more layers to offer.

S.M: Do you think that affected how it was received, because people were expecting to see a different story?

K.A: For sure. It was definitely a revelation for people. That’s feedback that I got quite lot – people said they’d learnt so much. Not solely based on the fact that Ghana’s not just poor people, but more the story itself – to understand that this actually goes on in 2017. There’s a class system in Ghana, and rich people can treat the poor people even worse than what you’ve experienced in your own country. It’s an interesting thing to examine, but I have to underline that the film isn’t saying that Ghana’s all like that. It’s just showing that that is there. Not all stories about black people are about slavery or gangsters. I’m from an area of London where you’d expect everyone to end up in jail, whereas I’ve got a friend who is doing extremely well in the corporate world and making a lot of money, I know people doing insanely well in the music industry, I know people in film from my area doing big, big things. People do really well in these areas, and let’s try and celebrate the people who make the right decisions as well, rather than focusing on the people who don’t and making it seem like if you go to these areas someone’s gonna come and stab you. It’s not the case!

S.M: Can you tell me a bit about London Calling Plus, which you’ve just been awarded?

K.A: London Calling is a scheme under Film London – they’ve got London Calling and London Calling Plus. It’s for emerging filmmakers who have some footprint in the industry and have got something to show for their career, to push them into a more professional surrounding. It’s almost like the next step in your career to making you the next best thing! A leg up with money, with crew, in terms of people watching your film, you have a spotlight. London Calling Plus is for Black and Ethnic Minority (BAME) filmmakers. You submit a treatment or script for the idea that you want to make with Film London and you have to write a director’s statement. And then you have to say who your team is. The producer I’m working with, Joy Gharoro-Akpojotor, who produced House Girl as well, submitted the script to Film London and we got shortlisted. The film we’ll be making is called Haircut and, like with House Girl, I’m examining something which I think is known to the masses in a one-sided way. I’m going in again with the camera and I’m gonna give you a full picture of what goes on. It’s set in an Afro-Caribbean barber shop in South East London, and it’s basically exploring what the barbershop is in such communities. They’re not just a barbershop, they’re so iconic. People go there to socialise, for therapy, for all sorts of reasons, not just to cut your hair. So much happens there and there’s so much conflict. I decided to choose something that may happen in a typical South-East London barbershop. The logline is “A middle aged barber has to keep the situation calm when a desperate teenaged drug-dealer holds up the shop at gunpoint.” It explores motives, and it adds the story behind what happened, rather than reading the news and seeing a black kid and thinking that he’s the devil himself. That just doesn’t help anyone. I’m not justifying it, but let’s offer human accounts. How do we stop these things from happening rather than demonising people? I’m from that background, I’ve seen it first hand and I know people personally that have made good and bad decisions and I’ve seen the results. We need to start taking people’s situations into account. PTSD is a huge thing in such communities. You can’t imagine what people go through, on a psychological and emotional level, to the point where they’re so vulnerable now, that that vulnerability is covered up with violence. The system is really difficult. If you come from nothing, to get out of nothing is enough to send you crazy. At the end of the day, I’m from that kind of background and I’ve gone to London Film School, but it’s because I’ve always been someone who looks for opportunities. I’m a Christian, and I feel like that’s got a big part to play in it, because God has led me to the right place at the right time. When I came to the London Film School I saw a whole new world that I was interested in, and some of what I came from had no interest for me. Slowly but surely, I started letting go of some of the negative interests which came with my neighbourhood, and that allowed me to learn new things in my new environment. I love the area that I grew up in, and it will always be my home, but I also want to explore different things, meet new people, dress differently, go to different places. I guess, if more people had that knowledge and support, and it wasn’t so difficult to leave behind the bad decisions and come to good ones, then more people would. So, what am I doing with Haircut? I’m going to these people and I’m taking a camera there with me, and I’m showing you an example of someone from such an area and what he has to deal with. I understand the slots that films like this can be put in, you can call it a hood film, call it what you like. But at the end of the day, the story’s not about the gun.

S.M: How are you casting it?

K.A: I’ve got a really good casting director, Isabella Odoffin, who my producer put me in touch with. She’s casted for films like Pan, '71, etc. We’re using half and half, professional and non-professional actors. I’ve chosen somebody for the protagonist already but I’m not gonna give it away! We’re looking at some very talented up-and-coming black actors. The one thing that I like about this project, as a whole, is that it’s a black story told by black people. I’ve got a mixed crew as well, but it’s about that visibility – black people making black films, telling our stories.

S.M: What led you to study at LFS?

K.A: I went to university straight away - in terms of education, I’ve always been on time! I graduated from Brunel in 2011, where I studied Communication and Media. At college, that’s when I really started editing and shooting and stuff and I really loved it. It was a whole different world to me, it kept me out of trouble and it had all my focus. That was all I wanted to do. At Brunel, it turned out there weren’t many modules to do with film, so I invested in a DSLR and I started taking pictures and using it for video as well. I started shooting commercials and music videos, doing that kind of stuff. And then … I wanted to know my purpose. I’ve always wanted to know what my purpose on Earth was, so I really explored myself quite a lot. I was a DOP at that stage and I was reading a book on film lighting, training myself. There was a quote in the book from Alan Daviau, who shot E.T, and I quoted it on Twitter. Then, some people called Master’s POV - which is a conference in LA - tweeted me back and said, “Alan Daviau’s gonna be here in January, you should come!” I thought that was some sort of sign. I didn’t @ anybody, but they found me. I told my dad I wanted to go, and he helped me out with some money. I went by myself and that was the turning point for me. I met huge people – Robbie Greenberg, who shot Free Willy, I met Alan Daviau … But the big person that I met, for me, was a guy called Karl Walter Lindenlaub. He’s a German DOP, and I asked him, “This whole film world, I’m learning so much and I want to be a part of it. Do I have to come to LA?” He asked where I was from. I was one of the only black people there, and I was from London, so I stuck out like a sore thumb. He said, “London is the film hub of Europe. You live in the film capital of Europe – so start there. Don’t go running anywhere. Apply for film school.” I didn’t have a clue about it, so I came back and Googled ‘Film Schools in London’ and the London Film School came up! I looked at the website and my soul just took to it straight away. I didn’t want to go anywhere else. I didn’t even bother applying anywhere else. You had to write a three-minute script, so I wrote a script called 3 Minutes, about the last three minutes on Earth. I’d never written a script at that stage, but I applied and I got in.

S.M: What did you get out of your time at London Film School?

K.A: It changed my life. It turned it upside down. You go in thinking you know everything, and then you realise you don’t know anything. It taught me to let go of what I think I know, even in my general life. I made a documentary, the first thing I ever directed, Deborah’s Letter, in the 3rd term. When we were getting the end of term crits, I was listening to the tutor give feedback and I thought, “You don’t know my sister!” (because it was about her). But he made such good points, and what he told me in third term has carried me through everything I’ve made since. “When you watch films you look at the information on the screen, not what they say, but what they do - the data that they’re giving you, that you’re observing yourself and that relates to you.” That helped me to cut things out that I thought had to be there just because I’d shot it - to tear things down and streamline it. That helped me with my grad film, it’s helping me now with Haircut. And LFS is based on that – putting that foundation in you so that you’re so confident when it comes to filmmaking that you can just focus on being creative. You know how to make a film with your eyes closed. They put you through your paces, and every term is intense. You learn really quickly, and you’re actually making films, over and over again until you know what to do without thinking. It’s an inclusive course, as well – I’ve done sound, I DOP’d, I camera operated, I directed. You learn everything, and you meet some great people while you’re there that give you great advice. The teachers are people that have been there and done it, so they give you that confidence. LFS has made me the filmmaker that I am right now.

S.M: Did you work with other LFS students on House Girl?

K.A: My DOP was Mark Kuczewski, who was in my class. The co-producer was Aegina Brahim, the editor was Julian Smith. We all started LFS together and it was really cool going to Ghana with them and showing them “my country”, in inverted commas because I was kind of a stranger myself. But it was really cool getting them involved.

S.M: Your films cover quite diverse issues, such as disability, spirituality, class, sexual and domestic abuse, but you seem to mainly tell them from a female perspective. Is there a reason for that?

K.A: I connect with women really easily, simply because I grew up living with my mum and my two sisters, so I was always around women. I live with my dad now, and my dad’s always been around, but growing up the only time I was around males was when I went out with my friends or my dad. Predominantly it was just women, so maybe I listened to their stories and wanted to put that on screen. I don’t think that was on purpose, but the type of subject matter was, for sure. I always wanted to do social commentary and say something about society – to shine a light on these things that people hear about but don’t know about. Let me share some knowledge!

S.M: So, what’s next for you? Will the support from Film London allow you to work full time on developing Haircut?

K.A: There’s not really money to pay myself, so I’m still balancing life. I’m a Christian and I base everything I do on that. I wake up in the morning and somehow I get fed – I don’t know how but it happens! I know that I’ve got a purpose on this Earth and I’m being used to fulfil it, so I’m totally comfortable. I don’t look at all the stresses, I don’t look at the difficulties. I ignore those things because I know that, when push comes to shove, there’s a lot of glory to come. Off the back of Film London and Haircut I’m working on a feature film as well, that’s been developed through a scheme called Modern Tales, which is so cool. I’m developing my feature with them, and they literally just take apart the idea and then piece it back together. It puts your product in a place where you’re ready to go to investors and ask for some money. I’ve got the confidence now to pitch it – you definitely have to mention Modern Tales, that changed my life as well, man! (laughs) I had an industry day with them last week and we were pitching our ideas to some really big execs. It puts us straight in front of the people that matter, which is amazing. It’s such a good opportunity, just to be there and see it and know how it feels. The feature explores similar themes to Haircut – it’s not a proof of concept, exactly, but it’s exploring the themes that I’m going to transfer into the feature. So, next year, fingers crossed, a feature and a short. That’s my aim. I know it’s very ambitious, but I’ve always been ambitious. I went to shoot a film in Ghana, you know? Everything else is easy! (laughs)

Watch House Girl and Koby’s other work at: https://www.kobyadom.com/

1 note

·

View note

Text

LFS provided the creative environment and network of mentors and peers who helped me find my voice, and taught me to trust it.

Monica Santis graduated from the London Film School in 2016, and her graduation film ‘Hacia el Sol’ (Towards the Sun) is currently touring the festival circuit, the highlight of which has been a double win in her home town at the Academy award-qualifying Austin Film Festival. Following a recent screening and nomination for Best Editing at London’s Underwire Festival, we caught up with Monica while she was back in town to talk about making a film about unaccompanied migrants in Trump’s America, why we need festivals like Underwire now more than ever, and what it’s like when your producer is also your Mum …

Sophie McVeigh: Could you explain the story behind Hacia el Sol?

Monica Santis: It’s about a 12-year-old girl named Esmerelda who has recently been placed at a shelter for unaccompanied immigrant children in Texas, and the film is about how she reclaims her voice through her artwork in the midst of the looming threat of deportation. She’s gone through a very traumatic border crossing and we see her confront her scarring past and take the first steps towards healing. She’s a girl whose voice has been silenced by violence, so she doesn’t open up because she’s traumatized. This was my graduation film, shot in Austin, my home town, and I got to work with a fantastic local cast and crew, and I brought several key LFS crew members because I love them and we work really well together, so I wanted them to be a part of this journey with me. My first AD was Andres Salas who is extremely hardworking, talented, and so positive. He has a great attitude, so I knew he would take on the challenge of running a set with up to 100 extras at one time! I’ve got to give a major thanks and congrats to the entire production team for working hard to coordinate that scale of a shoot. My DOP was Zeta Spyraki, and she was so grounded, disciplined, and creative. It was so special to work with a strong woman; Zeta is a true leader and artist and I loved collaborating with her. The film’s camera operator was the wonderful Mark Kuczewski, who directed ‘Happy Anniversary’, the first AC was Stephen Glass, the gaffer was Sebastián Lojo and the sound recordist was Heikki Simppula … so all phenomenal filmmakers. I was truly blessed to have a lot of talented fellow LFS students/friends there! I co-wrote the script with Elie Choufany, who is an alum of the LFS Screenwriting program (Cohort 9). We met my first year at LFS, and we just clicked and became really good friends and collaborators. We had worked together on several LFS course exercises, so we had developed a good working relationship and I admire him as a writer. I was so lucky to work with a cast and crew who poured their heart into this film.

S.M: What inspired the story and why did you want to make it?

M.S: In 2015, I visited a shelter for unaccompanied minors who had been placed there after being detained by border patrol on the United States-Mexico border. I went with an organization that runs shelters throughout Texas/Arizona—their aim is to reunify kids with their family members in the USA and provide humanitarian services. The shelter supplies housing, educational courses, legal representation, medical attention and emotional support. Their goal is to provide a home-like environment. I was moved by the sense of community and support from both children and adults. The majority of the kids are fleeing violence in their home countries and are desperately trying to reunify with family in the USA and seek refuge. As I sat and spoke with kids and shelter staff, I was particularly moved by stories about healing. A majority of children had survived an extremely traumatic border crossing and encountered violence and abuse along the perilous way. It broke my heart and motivated me to write this story; what I observed truly stirred me into action. I observed how a lot of children were in limbo as they waited - waiting to see what the uncertain future holds for them, waiting to hear from family, waiting for good news, waiting and anticipating bad news. I wanted to explore the point of view of a girl who had recently arrived, and I wanted to take the audience on an emotional journey with her as she takes her first steps towards integration and healing---in doing so, I wanted to humanize and create compassion around the immigration debate, which is being heavily politicized in the US. I wanted to shed light on a resilient community of children who deserve our support and deserve to feel safe.

S.M: What made you choose art as a way to tell Esmerelda’s story?

M.S: I remember walking through one of the shelters, and I thought that it would look bleak like the horrible detention centers that I’ve seen in the media. But it didn’t. It popped with color. There were murals, decorations and artwork that kids had drawn adorning the walls. I paused and looked at a drawing that caught my eye - a ten-year-old girl had drawn a beautiful, colorful hummingbird and she had written ‘May joy find you wherever you are.’ And I thought, my God, in the midst of all of this, all the struggle, the fear about an unknown future, this girl had drawn something really beautiful and hopeful. I thought, where is she now? What’s her story? Is she ok? I hope she’s safe, I thought. As I observed and connected with staff at the shelter, they told me heartbreaking stories of kids enduring physical and emotional abuse, of survival and facing death, of kids almost dying in the desert, running away from human traffickers, and crossing the border alone which appears in the film at one point in the drawing reveal sequence. We incorporated these details into the story. Since film is a powerful visual medium, I thought the drawing process would be therapeutic for Esmeralda’s initially withdrawn character, and that the drawings could speak for her.

S.M: Had you started working on the film before the current administration came into power, and do you think it’s had more resonance with audiences as a result of Trump’s presidency?

M.S: Story development and principle shooting took place during the Obama administration, but as we entered post production, and as the election fervor was gathering momentum, yes, I changed my approach because of Trump’s anti-immigrant, racist campaign rhetoric. I thought, should I discuss deportation very directly? Do we call out the monster or do we examine that in a more subtle way? But then I decided to insert the word ‘deportation’ in post because I saw that Trump was probably going to be the next president. To clarify, the Obama administration deported thousands of people, but Trump has run a campaign that cruelly depicts immigrants as the ‘other’, ‘the rapists’, ’the bad hombres’, and he has used that fear to stir up his supporter base. It’s a scary time in the US for undocumented kids/families, and I remember sitting with James Hynes, the film’s sound designer, and we just looked at one another somberly and said ‘yep, the word deportation needs to be included because it’s a palpable fear now that’s going to get worse’. In the festival circuit, during Q and As, we’ve had really good discussions where people are genuinely distraught and had no idea that thousands of kids were fleeing violence at immigration shelters. Generating this discussion about immigration is important because we’re talking about vulnerable kids, so actively creating awareness, compassion and understanding has become more crucial than ever now.

S.M: Was this your mom’s first time producing?

M.S: She had helped me produce a couple other smaller scale short films – as an independent filmmaker, you can’t help but get everyone you know on board in some capacity! (laughs) So, she had helped before and she’s a strong business woman; she’s CEO of a company, so she’s very on it! Those management and leadership skills came into great use, and she deeply cares about the kids at the shelters and knows the topic well, so she was outstanding. We learned a lot together throughout the process. I think she finally understands why I would be exhausted at the end of every shoot (laughs). She was super-Mom, always making sure plenty of food was provided and she recruited a huge amount of extras so I was really impressed. She did a really amazing job, especially for her first big producing role. I love my mom, she’s the best.

S.M: Has she been on the festival circuit with you?

M.S: She’s extremely busy, but we went to the Austin Film Festival screenings together which was great and a very moving experience for both of us. Zeta, Elie, and I got to attend the world premiere at Palm Springs ShortFest together which was truly awesome and memorable. Elie then flew in for the Austin Film Festival. Karen Garcia Cruz, the phenomenal leading actress, and her sister, the super talented Daniela Garcia Cruz, who plays Maria the new girl, got to watch the film with their whole family and with a full house at AFF. The screening was sold out, so that was a special day for all of us. We won the Jury Award for Narrative Student Short and the Hiscox Audience Award for Narrative Student Short at AFF. We won twice which was amazing – the best a student film could hope to do there. It means that people truly connected with Esmeralda’s story, and I am so grateful to the AFF jury, programmers, and audiences that supported us. What a surreal and truly wonderful experience. I’m so proud of our team.

S.M: Did it mean even more considering it’s your home town?

M.S: Yes! My heart was just so full. My passion for film grew there. The Austin film community helped develop my creativity, and to win at AFF was such an honour. I used to go to their screenings and dream about being a part of it someday. ‘Towards the Sun’ is still on the festival circuit now. We just got into another really great festival that I can’t announce yet! We still have a couple to hear back from, so stay tuned - some that are in US border states, which I’d love to screen at since I feel like audiences would particularly understand and connect with the story. I’d really like to be there to generate discussion and help create awareness about the plight of unaccompanied minors, so fingers crossed.

S.M: Could you tell me a bit about your background before you ended up at London Film School?

M.S: I’m first generation in the States, so my mom immigrated from Peru and my dad immigrated from Chile. I’m proud of my South American roots, and I was born and raised in Austin, Texas. I worked at the Austin Film School for several years as the Director of Outreach and it further sparked my passion for filmmaking. While I was there I helped develop the Cine Joven: Filmmaking in Spanish program for young filmmakers. I met a lot of talented kids, and I’ve always been an advocate for children’s rights so after working with them, I followed that interest and my interest in US-Latin America international policy and decided to attend The George Washington University Elliot School of International Affairs to get my Masters in Latin American & Hemispheric studies, focusing on anthropology, sociology and history. My thesis capstone project had to do with researching/creating awareness about human/child trafficking in Puerto Rico. I went into it thinking I might want to go work for the State Department or Unicef, and I respect everyone who went that route, but then I missed writing creatively. I watched a lot of documentaries about human rights while I was at GW, and I realized how powerful films are and I wanted to make an impact that way. So, I went back to filmmaking and joined the Documentary Film Institute at George Washington University. I learned a great deal there, and I’m still in touch with peers and the amazing mentors who jumpstarted my return to filmmaking. From there I thought I really needed to catch up and get more technical training because I was making a big career change. So, while I was visiting a friend in London, I immediately fell in love with the creative energy of the city, so I started researching film schools and found LFS. I loved LFS’s mission, and I highly respected the filmmakers that have come out of LFS, so I applied and was so happy to get in. I really liked this idea of organically finding your voice, getting to try out different roles and shooting on film stock. So I thought, ok, let me give this a whirl. It was the best decision I’ve ever made because the amount of personal and creative growth I experienced during my time at LFS was just amazing.

S.M: How did you find adapting to life in London, coming from sunny Texas?

M.S: It’s a little drearier, obviously, but I didn’t mind it! I did miss my family, but thankfully I was able to make friends quickly. I openly embraced London, and I really loved the creative, bustling lifestyle here. I felt an instant click from the moment I landed, and I miss the film community here obviously, hence why I try to come back so often!

S.M: What’s the most important thing you learnt at LFS?

M.S: LFS provided the creative environment and network of mentors and peers who helped me find my voice, and it taught me to trust that voice. It brought out a confidence in me, towards the end there especially, that I didn’t know I had and that I was searching for. Being supported by teachers and peers that love the craft as much as I do created a strong sense of community to collaborate and grow with. I loved analyzing and being exposed to new films, styles, techniques. As a result, I was able to expand my mind, really open my heart and put it into the work. That invaluable network of storytellers/collaborators continues to inspire me, and I truly cherish the LFS community.

S.M: Your background has obviously had a lot of influence on the kind of stories you want to tell, but did you find that the people you met at LFS also had an impact on how you tell them?

M.S: Yes, I was constantly learning from my teachers and peers. I loved the fact that LFS is so international, and I wanted to meet people with different perspectives and different backgrounds but with a similar passion for filmmaking. I wanted to meet and learn from fellow story tellers from all over the world. That was a big selling point for me and why I chose to apply to LFS, because I value diversity. I found it incredibly enriching.

S.M: You’ve recently screened Hacia el Sol at Underwire in London, which is a festival that promotes the work of female filmmakers. Do you think it’s even more important, given the current climate, that we have these kinds of festivals?

M.S: Yes, definitely. The patriarchy is real and we gotta take it down! The industry is extremely unequal, and women have been systemically undervalued and denied the same opportunities that men get; women deserve representation and to have their voices amplified. At the opening screening at Underwire, I heard someone say something to the effect that, as a woman, it’s important to remember that you have a right to claim your space in the filmmaking industry. To be honest, I got chills. It was a good reminder that we don’t have to make ourselves small, we can claim that space and demand respect. I felt such a surge of empowerment, and I felt so happy that Underwire exists, because they’re creating a space to recognise, support, encourage and celebrate female filmmakers. By the way, we need more female directors and DPs! It was so inspiring to be at festival screenings with up to 80% women in attendance; I felt so honored to be in solidarity with such talented women. When there’s an unequal power dynamic and when abusive men like Harvey Weinstein exist, I believe festivals like Underwire are crucial in helping bridge that inequality gap and creating a safe space for women to learn and grow.

S.M: Do you think that had an influence on the atmosphere at the festival, coming so soon after what’s been happening in Hollywood?

M.S: I think it must have. This was my first time at Underwire so I can’t compare, but I felt that beautiful feminist warrior spirit in full force. In line with the #metoo movement, there were a lot of women fearlessly speaking their truths and sharing their stories on screen. One of the filmmakers at the festival noted how it’s important for women to feel more empowered to just express themselves freely, not be perfectionists as society has conditioned many to be, and just say what you’ve got to say! That spirit of speaking your truth and being your authentic self was really shining through at screenings and in discussions.

S.M: What are you working on at the moment?

M.S: Right now, I’m working on a short script from a similar world to Towards the Sun, so another kid’s perspective in a shelter. And then I’m slowly developing the idea of a feature length story within that world, about unaccompanied minors. That’s in early stages of development, and otherwise I freelance edit. I edited a short documentary that’s currently in the festival circuit called ‘An Uncertain Future’, which was directed by Chelsea Hernandez and Iliana Sosa, produced by Firelight Media and Field of Vision, which is Laura Poitras’s production company. So that was a really cool experience as an editor, to be getting notes from Laura Poitras! I learned a lot!

S.M: Was editing a skill you learnt at LFS?

M.S: I began learning on Final Cut Pro at the GW Documentary Film Institute. LFS gave me many opportunities to edit, and I learned a great deal from the amazing teachers in the editing department. I edited in terms one through three, but I learned the most in term 3 when I edited ‘How We Are Now’, directed by Andrea Niada. Since there’s so much footage to work with in documentary, the editing process was a true lesson in how to craft the story through the edit.

S.M: What’s your process as a writer? How do you balance your work and your time to be creative?

M.S: I’m actually in the writing process right now. It can be tricky to fit everything in, so I make sure to write something every day, whether that’s a line or a scene. I try to make sure I keep the inspiration flowing, because writers’ block can happen so easily! I aim to find that kernel of inspiration and make sure that I’m constantly reminding myself why I’m telling a certain story. When things get hard, I remind myself what the heart of the story is and that motivates me to keep going.

Keep up with Hacia el Sol’s progress on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/HaciaElSolFilm/ and Twitter: https://twitter.com/HaciaElSolFilm and watch the trailer: https://vimeo.com/226004442

1 note

·

View note

Text

“LFS is just this mixture of people that brings this energy which holds in its center cinema itself” - Jiajun (Oscar) Zhang

Jiajun (Oscar) Zhang (above third left) graduated from the MAF program this year and has recently taken part in the Asian Film Academy, which takes place every year in Busan in South Korea.

AFA, similar to the Berlinale Talent Campus and Serial Eyes programmes, is “an educational program hosted by Busan International Film Festival, Busan Film Commission and GKL Foundation to foster young Asian talents and build their networks throughout Asia.” Over the past 12 years, 289 alumni from 31 countries have taken part, along with world-renowned directors such as Béla Tarr, Jia Zhangke, Hou Hsiao-hsien and Lee Chang Dong, participating in a program which includes short film production, workshops and special lectures. The two short films completed by attendees are then officially presented at the Busan International Film Festival.

We spoke to Oscar having just completed the programme to find out how he found his way to London Film School, what he learnt from his time here and at AFA, and where he’s headed to next…

Sophie McVeigh: Could you tell me a little bit about your background before coming to LFS?

Oscar Zhang: I was born in China, in Shanghai. It’s a big city and I was interested in cinema since I was 14,15 years old. As a lonely teenager I naturally got drawn into cinema, like a lot of us! Then I studied at university, a media subject, and I started making short films at that point. That got me started... travelling to small festivals around the world, and I thought, wow, this is really a career that I could do. After that I started working as a commercial director, to make a living for about two years. I got really tired of it, so I thought maybe it was time to stop. By that time, I was working with a bunch of guys who had studied in London and came back to China, and they told me there was a good film school called the London Film School. They said if I wanted a change of atmosphere I should consider going there.

S.M: What made you want to come to Britain, over say the US or schools in Asia?

O.Z: I guess because a lot of my friends, they’d graduated from UK universities and they came back and worked in the industry. I was living with a bunch of older boys at the age of 18, 19, and they were telling me about life in the UK every day, so it seemed natural for me to go there.

S.M: How did you find adapting to life in London when you first arrived?

O.Z: It’s super different to Shanghai, the system and how everything works, and my English wasn’t perfect when I arrived. I couldn’t understand all of the classes at first. That’s what I most regret because I realised the stuff I missed could have been very important! But later on, it got better and better and I started to get the most out of it, lecture-wise and making friends.

S.M: Did you always want to specialise in directing?

O.Z: So, at LFS we have six terms and we make films each term, but you have to pitch to be a director. I was kind of lucky, I did five times directing out of six terms. I think I optimised my chances in school as a director! So, I think I can call myself a major in directing (laughs). I was always writing my own scripts too for all those terms.

S.M: Can you tell us a bit about your graduation film, which has been chosen to screen in the Showcase in December?

O.Z: It’s a film that’s actually inspired by one of my colleagues in my class. She’s from Taiwan and she’d been living in Shanghai all her life. The political situation between Taiwan and mainland China is kind of sensitive. There’s actually 800,000 immigrants in my city but they don’t have a proper identity. So, what I heard from this girl, she was complaining to me one day as we were walking in Covent Garden, just chatting. She said, “I don’t know what to do when I go back to China, because I grew up there, but they don’t really want me for any jobs when they see my identity as a Taiwanese. It’s hard for me to get a working certificate, but if I go back to Taipei I don’t have any friends there so it’s gonna be hard as well. I’m really in a state of limbo.” That inspired me to make a film focused on a character like that. So, my main character is a teenage Taiwanese girl working in Shanghai. She’s living with her family and there’s an emotional story around the relationship between her, a teacher and a younger boy. This was the film I submitted to get accepted to the AFA (Asian Film Academy).

S.M: Can you tell us a bit more about that?

O.Z: It’s a selective group that takes part for one month and it’s like a platform. You have the most prestigious directors in Asia. All the candidates are from Asian countries, it’s one or two candidates from each country, and they select 24 people and you make two short films there and attend a bunch of lectures. They will be in this sort of Busan Film Festival family from that moment, so you get to be part of it and to submit your film later. There’s also a pitching session to pitch our first feature script idea. Luckily, I got the first prize for that so they’re sending me to LA next year for further pitches to producers and stuff like that. The film I pitched was one of the ideas that I submitted with my application to LFS. It was an idea that had been in my head for a long time which focuses on contemporary Chinese society issues. One thing I liked the most about the experience was that it’s this dream like place, that gathers all the filmmakers from across the region. And the moment you leave the platform after spending almost a month with all these people sharing the same kind of dream… at one point, I felt like all of these people had been like a family before, you know - a filmmakers’ family just like the people I met at LFS. We belonged to the same unknown planet, and were sent to this world to create something. But then, after we die or before we were born, we would be always together, as a family, and we would meet each other in that place after death, a place that belongs to all worthy filmmakers. That’s the kind of crazy dream idea I got after this emotional experience there!

S[4] .M: Are the issues in contemporary Chinese society something that you’re focusing on at the moment in your filmmaking?

O.Z: Yeah, in a way I am doing that. But, at the same time, as I look at all the films that I’ve done, including the ones at LFS, I realise that most of them aren’t really about social issues that much. They are in the background, but I was mainly interested in relationships between people rather than the hardcore social issues.

S.M: What did you like about living in London?

O.Z: It was just party after party (laughs). I met a lot of people that I thought were strange at first, in terms of my culture, but as it went on I realised they were very interesting and inspiring. Not just people from Britain, actually, I was influenced by people from all over the world. It’s just this mixture of people that brings this energy which holds in its centre cinema itself. This kind of turned me into a hardcore cinephile! That was the most life-changing event that’s ever happened to me. And the BFI (British Film Institute) as well. The BFI is the place me and my cohort mostly slept (laughs). We went there very early in the morning and we came out after the last screening finished, when we didn’t have classes. You don’t have to buy tickets, it’s free. Me and my colleague actually collected the tickets and there were hundreds of them. I think we made our school fees back! The films they screened there were invaluable.

S.M: What was the most important thing that LFS taught you?

O.Z: I think I’d divide it into two parts. The tutors that I encountered were two or three of the most important in my life. They were there back in the day of the early British film movement. Their experience, their knowledge, the insights they gave me – they gave me a lot, and they opened me up, to put it simply. For example, one of the tutors would show Westerns films, like the films of John Ford that I would never have touched because Westerns are nothing to do with my culture, I was super not interested in Westerns! But he analysed the film and the way he turned it into a useful strategy for us to learn as directors was just very precious for me. The tutors were great. The other part is that I learnt the most from my colleagues at the school. I had the luck to have the best cohort I’ve ever seen! We were a big bunch, 36 or something of us from 30 different countries, but strangely we bonded very well together. They were all very passionate people. We would go for drinks and not stop talking about film. When we graduated some of us were still working together and making films together. After leaving I’ve visited three different countries to meet LFS colleagues. I guess I learnt my life’s lesson from these people.

S.M: Do you think that international influence has had an effect on your filmmaking?

O.Z: Absolutely. One of my colleagues, Keenen and I were talking about what the next wave is going to be – you know there was French New Wave, Italian Neo-Realism, all this. So, we were thinking, what’s gonna be the next one? And he told me what’s going to happen is that it’s not going to be regional waves anymore, it’s going to be a global one. As you can see, how the internet brings us together, how this school brings us together. We are really becoming a world family, this film society. And as we experienced in the school, when I make a film I would have 15 non-Chinese people on-board and we worked perfectly fine. So that enabled me to think about being a global filmmaker. My next feature project, I was thinking it will be collaborating in Korea, I’ve got something else that I’ll shoot in London, another in Malaysia… so that’s what the school brought me, the courage to become a filmmaker that will make films globally.

S.M: What are your plans for the coming year?

O.Z: Me and some other colleagues have decided to meet regularly somewhere and make small independent film that really don’t cost very much. The next one we’re going to do is in Seoul, South Korea, next year. At the same time, I will work on scripts both for indie films and the Chinese film industry. I’ll be in the US for a year at some point. At the moment, I’m really into super low-budget shoots. Anywhere I go, I have my camera and sound-recording equipment. We’ve got a cohort in the States, so we’ve been talking about working together there.

S.M: What advice would you give to someone who’s been accepted to LFS, to help them make the most of their time here?

O.Z: I think the reason why we were a very conscious cohort was that we had good tutors who told us the truth and kept us sober. My most critical advice is, in any circumstance, be aware of your work and always reflect on that. We are here in film school to learn. Open your heart to a lot of things. And also, don’t rush your career. In my experience it’s better to wait and perfect your skills than rush into stuff.

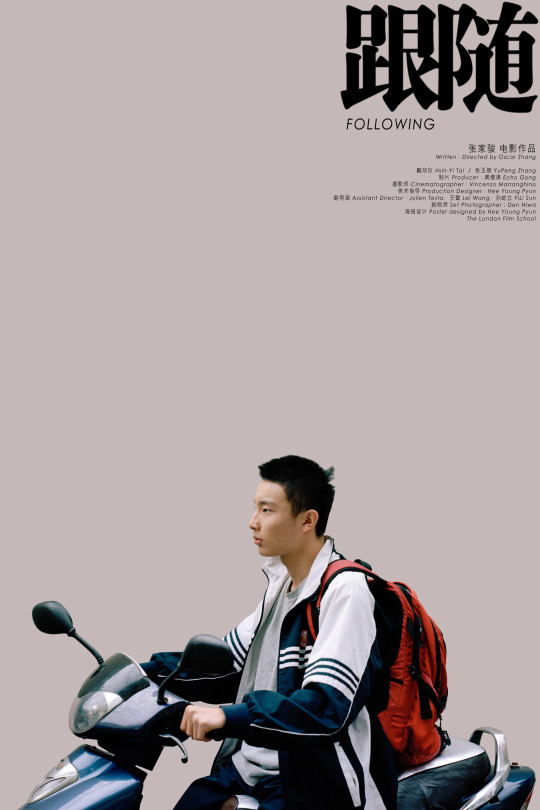

FOLLOWING (27:11 mins, 2017)

Writer-Director: Zhang, Jiajun

Producer: Gong, Yingqing

Production Designer: Pyun, Heeyoung

Cinematographer: Marranghino, Vincenzo

Assistant Director: Testa, Julien

Camera Assistant: Walsh, Paisley

Sound Editor: Chim, Terence

Interview: Sophie McVeigh | Photos: Annual Show by Katie Garner, Group Selfie by Putri Purnama Sugua, Film Poster of FOLLOWING

#bfi#french new wave#italian neo-realism#korean film#filmschool#busan film festival#afa#asian film academy#bela tarr#jia zhangke#hou hsiao-hsien#lee chang dong#chinese film market#hollywood#londonfilmschool#film directing#westerns#international

0 notes

Text

INTERVIEW with Newcastle-based and one-of-a-kind filmmaker: Benjamin Bee

Writer/Director Benjamin Bee graduated from London Film School in 2015 and moved back to his home town of Newcastle Upon Tyne, where he’s continued to hone the unique brand of personal- tragi-comedy which has seen his films screened at some of the world’s biggest film festivals and attracted the likes of Mike Leigh to his Crowdfunding videos. Ben turns his own life story into art, and it’s not hard to see why – within minutes of meeting him I’d been told an anecdote involving an axe, a crazed lunatic and a carton of banana milkshake. Below is the publishable version of Ben’s take on the North-South divide, his time at LFS and what it is that makes his ‘bonkers’ stories so universal.

S.M: Can you tell me a bit about your life before applying to London Film School?

B.B: I left school in Newcastle when I was 14 without any qualifications, and then I went to an access to college course. They did photography and had an old, broken VHS video camera, and with the people that I met there we started making comedy, stupid little films. They were unscripted, and weirdly I used that to get into the University of Westminster to do Contemporary Media Practice. That was in 2002, and then at the end of that course I made a short film called The Plastic Toy Dinosaur, which was produced by Rob Watson who’s an NFTS producing grad who’s doing really well now. I didn’t have a clue what I was doing, I wrote it when I was 21 and I directed it when I was 22. I moved back to Newcastle and started working in a bar, but I hated it and I was miserable and the only thing I realised I had was this short film. I didn’t know about anything, I didn’t even know Cannes or Sundance existed.

So, I just started entering it in places that I found and one of them was the BBC3 New Filmmaker of the Year Award. There were tons of submissions and they selected it down to the last ten. It was actually a really good year – Alice Lowe had written and starred in one of them, and Sean Conway had a film as well, he writes for Ray Donavan now. It was nice because people started to screen the film and it seemed like they liked it and it resonated with audiences, but I still had no idea what I was doing and I was incredibly naïve. I mean, seriously dyslexic and had the reading and writing age of an 8-year-old. Not going to school probably didn’t help. So, I was kind of lost. I started working a theatre box office and I worked, like, 60 hours a week and tried to save money. And then I saw a Skillset bursary advertised. I’d always looked at LFS but I couldn’t afford the fees, but eventually after I’d saved some money from my job I applied and I got the bursary.

S.M: What did applying for that involve?

B.B: It’s based on previous work and it’s means tested so you basically have to be poor and talented, or at least fake them into believing that you have some form of talent (laughs). I think I had something to say, coming from a slightly different background, and all my stories are weirdly personal. You go in front of a panel and when I got called back I literally cried like a small child. And then I went to LFS! It was interesting and difficult and there were people from so many different walks of life. I learnt the craft of filmmaking – I tried to eat up everything.

The most important thing for me was the people – you’re surrounded by people who are really passionate about film. It’s two years surrounded by people who’ll put a lot of effort in, and I met a lot of people who had a lot of fun making films that I’m really proud of. I did a film called Step Right Up when I was there, which was my Term 4 exercise. We had 36 minutes of film stock to make a nine-minute film and it was screened at 40 film festivals. We got long-listed for the BAFTA, which means we were down to the last 10 or 15, which had never been done before by a fourth term film. It was huge.

S.M: What do you think it was about that film that made it so successful?

B.B: I make comedies and they’re personal. I’ve never really struggled with getting films into festivals because I don’t try to make arduous bulls**t. It’s personal, and also I’m not the most masculine man but I know lots of masculine men who do have feelings, and everybody has a shared experience of feelings and pain so there’s nothing that makes even the most masculine, awful guy not sensitive. A lot of my films are about paternal bonds or absent father figures, because my dad left and he was an utter c***. So, I’ve got a lot of things like that, that kind of resonate.

My new one’s about something that genuinely happened, which was when my dad left when I was five and my mum decided to take me and my brother out of school and take us to Metroland, which is a theme park in Newcastle. My brother went on the dodgems but I was too little, so I had to go on the merry-go-round. It was amazing, and I was on a big white horse going round and round. Every time I’d come round I’d see my mum just stood there in floods and floods of tears, and then I’d go past her, and I could see my brother having the best time ever. That’s an analogy for my relationships with my siblings! I think if you say things that are deeply personal then they’re always going to do much better than things that aren’t you. When I started in term one and term two, I started trying to make stuff to look more “intelligent”, and then I realised that it wasn’t making me at all happy. So, by term four I made something ridiculous and by graduation I made a film called Sebastian which was a horror comedy which was also a bit nuts.

S.M: Was it always your plan to go back to Newcastle after graduation?

B.B: The day I handed my grad film in I went for a meeting to direct a pilot taster for Baby Cow, Steve Coogan and Henry Normal’s company. I got that, and I brought Yiannis (Manolopoulos, fellow LFS student and cinematographer) in, it was written by a friend of mine, Dan Mersh, who was also in Step Right Up, Plastic Toy Dinosaur, Sebastian and Mordechai. And that was really good because I got to meet Henry Normal, who was the managing director of the company. He’d written the Royle Family, Mrs Merton, he’d produced some of my fave TV shows, including the Mighty Boosh … He loved it. but Channel 4 didn’t pick it up. Then I moved back to Newcastle, in 2015, and broke my ankle running for a train! I was in a cast for over a year.

Then I applied to the Jewish Film Fund for my film Mordechai, I’m not actually Jewish but the film’s subject is. It’s doing really well, it’s got into Palm Springs, BFI London Film Festival, and various others. It’s about these identical twins, one of which has left the community and one of whom has stayed at home. There’s an ultra-orthodox community in Gateshead and it’s quite insular and interesting. So, I developed a story about, what if one of them had left and then had to come home for a reason? The dad dies and the other brother comes home and he has to go and pick him up. They’ve got very different life choices – one brother’s dressed in black and the other turns up wearing tie-dyed hippy shit. He’s still Jewish but in his own way. Mordechai is really happy and charming and Daniel, who stayed at home, is a bit more down-trodden and miserable. Then Mordechai drops dead and Daniel makes the decision to body swap and becomes Mordechai and goes to his own funeral. It comes out the end quite positive but it’s also quite emotional!

S.M: You work a lot with producer Maria Caruana Galizia – is she someone you met through LFS?

B.B: No, she’s from Malta. She moved to Newcastle after living in Scotland for a while (I think), and there’s very few producers here. I met her at a networking event – she liked something I’d made, I liked something she’d made and we just decided to try and apply for stuff. She’s fu***ng awesome, super talented and incredibly hardworking. Also, she puts up with me…

S.M: Do you find that being based up in Newcastle has its pros and cons?

B.B: It really does. The benefits are that you can shoot anywhere for dead cheap but crewing’s impossible because every good member of crew’s doing Vera or The Dumping Ground. There’s swings and roundabouts. It’s beautiful, and has a better quality of life but there is definitely a massive divide. All the work’s in London, all the agents are there.

S.M: Do you manage to make a living out of the work you’re doing at the moment?

B.B: I’m a very cheap human being. It’s difficult when you start out because a lot of the stuff that you’re doing, like the shorts, aren’t going to make any money unless you start winning prize money. I’m at the stage now where it’s a little bit easier because I can apply for funding for development from the BFI etc. That’s what I’m applying for at the moment. I’m doing a project with Henry Normal, a documentary on him and his poetry. I’m also just finishing Metroland and I’m really, really happy with it, but I’ve got no idea how it’s going to go down ‘cause it’s a bit mental.

S.M: How did you get Mike Leigh to appear in the crowdfunding promo?

B.B: He pops up in it, and basically the whole joke is that the film’s kind of like Weekend at Bernie’s, but imagine Weekend at Bernie’s if it was directed by Mike Leigh. You see the door open and it’s Mike Leigh going “Ben, can you stop phoning and emailing me and if you give me another copy of Weekend at Bernie’s …” (laughs).

I sent him an email going, “Hi Mike! Creative England are insisting that I do Crowdfunding and I really don’t wanna do it, so instead of making a video in which everybody’s positive, I want to make a video where everybody’s really negative about the experience.” He said yes without questioning it for a second… When I shot the video with Mike it was me, Yiannis and Eoin Maher, who did Filmmaking at LFS as well, and Mike who was just really hilarious. It was a lot of fun. Mike’s always been incredibly kind and supportive. He’s got a really good sense of humour. It’s the thing I love about his work to be honest.

S.M: Have you found it cathartic making such personal work based on your own life?

B.B: Unless you’re very good at what you do, this is just my advice, you can hide everything but what you do has to at some point be personal and resonate. Deconstruct any movie ever, like every movie Wes Anderson ever made is basically about his father walking out on his family, even though you don’t always realise it. It’s all about masculinity. It’s that thing that all your faults are your strongest features. I definitely find it therapeutic and I definitely think you deal with stuff. Spielberg says that it’s the only job where you get paid for therapy. I think that’s a great quote because it’s true in a way. Especially if you can’t afford therapy!

S.M: What do you think was the most important thing that LFS taught you?

B.B: The main revelation was that, whenever anybody goes into anything, doesn’t matter if it’s school, college or university, everybody comes in with a competitive nature that they’re going to be the best. Being competitive with yourself and wanting to make the best work is amazing, that’s the best way to be. But anybody else, whether they’re a director or whatever, should be your friends and your peer group, people that will help you. You basically have a support network with other filmmakers. That was really helpful, because it felt like you had a cheerleading squad and you could also do it for other people and you’d be really grateful. And that’s the industry – you’re not really in competition because nobody’s going to make the same film as you. You learn that very quickly at LFS because there’s people making such different work and you can really appreciate it. Then those people can come and work and collaborate on something you’re making, and you make something different and everybody learns from each other. Definitely the international vibe really helps as well. I was one of very few Brits and that was really nice, because obviously in Newcastle it’s mostly just people from there. In my term I had Yiannis from Greece, Pauline who was French, Rodrigo who was Mexican, Habib who’s American … it was really nice. I enjoyed it. Everybody’s great! Working with happy, positive people who feel comfortable in a nice environment is what makes the best work. And I think that’s what comes from having so many passionate people at LFS. It was a life-changing opportunity.

#mike leigh#filmmaking#weekendatbernies#filmstudies#wes anderson#creativeskillset#lfsorguk#gateshead#newcastle#steve coogan#babycow#metroland#sundance#rob watson#sean conway#dyslexia#london#bfi#jewish film fund

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Students are the purest fuel for the film industry and it’s great to be around them” - Heads of Screenwriting, Sophia Wellington & Jonathan Hourigan

Sophia Wellington and Jonathan Hourigan have been popular tutors for many years at London Film School (LFS), so it was no surprise when they were chosen to fill Brian Dunnigan’s considerable shoes when he left this year after 12 years as Head of Screenwriting. We chatted to them about their new shared role, what they love about LFS and how they’re continuing its legacy.

S.M: Could you tell us a little bit about your background before working at London Film School?

Sophia Wellington: I got into film, I think like a lot of people, by accident. I had a temporary job at the BBC, at Television Film Studios, Ealing (TFS) and then whilst I was there I started to follow the camera crew around and went every weekend for about four weeks, going on set and just talking to them. And then, from doing that, I got onto a course at the BBC where I trained in technical production and on studio cameras. I then became a camera assistant on film cameras and then in the cutting room. My training was mainly technical and, as I say, by accident, but that’s how I started. Then, when Avid became very popular, I made that switch to development and worked in development and production as a freelancer, working with writers. And the rest is history!

S.M: You’d taught before, in Singapore?

S.W: I did, but actually the first place that I taught was at the LFS. Like a lot of people in the industry, I thought that once you get to a certain level in your work it’s really important to try and give back. So, I was a mentor here in 2004 and then started as a feature development tutor, around 2005-6. I did that for a year or so and then went to Singapore and taught full time. New York University has a film school in Singapore, Tisch Asia, and I taught there for eight years. It’s a long time to be away from the UK industry, but it was really useful to be in Asia. The training that I got in Singapore made me aware of the different film industries, but also how universal stories can be and should be, and how to approach them and ways of storytelling. When I left Singapore, I came back to work at LFS.

Jonathan Hourigan: I was interested in photography when I was a teenager, my uncle was a photographer and taught photography at West Sussex College of Art and Design. I remember going to a screening there one afternoon and I saw The Spirit of the Beehive, projected on a scratchy 16mm print, literally onto a white sheet stretched onto a wall. And that was the moment I vividly remember thinking, “Oh, that looks like an interesting thing to do, I don’t want to take photographs, I want to do something about making movies.” Then I went to university and did an academic degree, and was interested in the cinema but didn’t really know how to get going. I got very interested in a French director called Bresson and I got in contact with him and showed all his films in London, as you couldn’t see them otherwise, and it just happened that as I was finishing university he was making a film. So, I went and worked with him in Paris for a year, and I came back and thought, “Well, I’m not very enterprising and I know that about myself, so I’ve got to go to film school.” I’ve got very clear views on why you should come to film school, and having come back to the UK after working with Bresson in France it took me a few years to get around to making a film to get me into the National Film School. I went there for several years, then left the National where I studied direction, tried to set things up and I just found I started to get work script reading and got more and more interested in writing. So, I started to write, and do some teaching around that and in fact, Sophia introduced me here at LFS. I was a mentor at some point around 2003-4, just before she went away (to Singapore) and I think I probably inherited her feature development group. I took an opportunity that was too good to say no to, which was to replace Sophia! And the rest is history. I teach here, a little bit elsewhere, and carry on writing as well.

S.M: This is the first year that you’ve both taken over from Brian Dunnigan, who’d headed the MA Screenwriting program for 12 years. Why did you decide to share the role?

J.H: We’ve both worked here for a number of years and feel very loyal to the place. We’re very interested in the way the school works – there aren’t many conservatoire film schools left. We worked with Brian but also with a very good group of other visiting lecturers, and we felt there was something really powerful about that group. When the opportunity came up because Brian was leaving, and the school was looking for a new head of screenwriting, we thought it would be a great opportunity to step up and do something different, slightly change our focus. Job sharing allows us both to share the challenges of doing this job which is great, but also to carry on doing other things so that we’re out in the industry as well.

S.W: I completely agree. I think that from our time here, at the school, we’ve got a commitment to it. We think it works really well, and we’ve got a great core of tutors. And so, when Brian left, there was the risk of somebody new coming in and changing it, or whether we could step up and protect what we have and continue it. And so, I think that for both of us that was a big part of it – trying to continue this great legacy and this great team, and make it as good as it could be. The job share, I think, is really important because this is such an industry facing course, and it allows us to keep links with the industry and with outsiders. There’s a lot of work to do here, and being full time it’s possible just to focus very much on the teaching and the students, which is important, but at the end of the year they do have to go out into the industry. Our connection with the industry allows us to be mindful of that at all times – that not only are we teaching students to be as good writers as they can be, but in a year’s time they’ve got to go out into the industry. We have to make them aware of and prepare them for it, and this job share offers, I think, the best opportunity to do that.

S.M: Has it been a case of taking the baton from Brian and carrying on more or less the same, or are changes afoot?

J.H: As we said, we’ve always felt there’s something very special about the structure of the course and about this school, and so you want to preserve a lot of what’s going on. But we’ve changed a number of things. We’ve got some new tutors involved, because we’re not now doing so much of the frontline teaching ourselves. We do the Work and Research Journal in a slightly different way than has been the case in the past, although funnily enough in a way that’s an evolution that’s in keeping with the rest of what we’re doing. We’re now doing the journal in group sessions, which of course replicates the very powerful feature development group model, and it seems to be working well. It’s a change but it’s in keeping with what’s been going on. But there haven’t been any major ruptures with the past.

S.W: I don’t think there needed to be. The way that the course was run was excellent and incredibly strong. With the two of us, it now means that there’s a little bit of fresh energy, because I would say that we are aware of different challenges facing the course and the industry. So, we have to be mindful about how we’re going to deal with those. One of the challenges that we’re dealing with is, of course, the popularity of writing for mediums outside of the big screen – for television and other areas. And whereas our focus is very specifically on writing a feature script, we’ve also got to see how we can address a changing industry and make sure that our writers have the skills that can transfer into these other areas, while still ensuring that we have given them the best teaching possible. So, while there are no major changes, we are very aware of new challenges and spending a lot of time thinking, “How can we tweak areas here and there to make sure we can face these challenges?”

S.M: Having both worked and studied in a variety of different film school environments around the world, what do you think is special about London Film School?

J.H: In terms of the school, the non-specialisation is really powerful, having graduated from the National myself where you specialise right from the beginning, I think it’s a really interesting comparison. You see people who embrace it and make a strong decision to come here because they really want to experience that whole range of roles involved in making a film. On this course in particular, I think the thing that’s impressive is how collaborative people are. Students are developing their own ideas, about which they are passionate, but there’s a very powerful sense of collective purpose and that they can all flourish equally and so therefore there’s real benefit in supporting one another. Not in a complacent way, because support is often by giving robust challenges, but I think that’s really powerful, that sense of collective identity. They make very different work, but there’s a real sense that they’re a group. They stick together and help one another. It’s impressive.

S.W: Just to go off that, of course, it’s a one-year course. All the other courses I’ve been on have been over two years, so this is incredibly intense and much tighter, by virtue of being one year. We do encourage a lot of that learning and development to come from fellow students, not just from the tutors. Compared to the other film schools I’ve been at, which worked incredibly well for what they did, I think that the way that this course is organised and how we work within small groups and the really great student to teacher ratio allows everybody to be incredibly supportive of each other. It forces a strong community during the year that they are studying here, and it also creates a very creative environment where they are getting feedback, not just from tutors, but from each other. They understand that that’s what they’re supposed to do. So, I think that’s one of the real strengths for writing here. Writing is such a solitary profession, I think it’s fantastic that they start their learning in understanding that, actually, it can be more collaborative. You can get support from others. This is a different way of doing it, it’s not just about locking yourself in a dark room and writing, it’s actually about being supported by other people. That’s a very strong ethos of the school and one of the things that makes it unique.

S.M: How does the school prepare people for life after film school?

J.H: You’ve got to prepare people for moving out and working independently, and it’s a real challenge. We send them out, hopefully, with the capacity to generate good ideas, a lot of powerful transferrable skills as writers, a set of relationships with other writers, the people who teach them and the filmmakers up the road. And, of course, the film industry in London, so a world of agents, producers, other writers who hopefully come through the school and who they meet on their journey through here. The thing that’s impressive in comparison with when I was at film school is that students also come with a lot more enterprise. We don’t have to work that hard to talk to them about preparing for life after film school. I was talking to some of the current cohort, who are only four weeks in, and they’re already thinking about that. They’re more and more proactive and thinking about how they’re going to make themselves employable, without compromising the educational and creative work that they’re doing here. I think that’s impressive.

S.W: It’s always a challenge, preparing students for the industry, and we can talk about the schedule that we have here, the industry guests that we bring in and the fact that all of the tutors are visiting lecturers who work in the industry. So, every bit of their teaching is informed with their industry experience. The students are surrounded by, and their teaching is done by, industry people. For all film schools, leaving is challenging. It’s like being kicked out of the nest, but we provide them with the tools and the skills to get out there and to fly! The other challenge is always to provide them with the confidence to believe that they have those skills.