#terry dennett

Text

What’s your story?

The Use and Abuse of Narrative

by Terry Eagleton

Forty years ago, Peter Brooks produced a pathbreaking study, Reading for the Plot, which was part of the so-called narrative turn in literary criticism. Narratology, as it became known, spread swiftly to other disciplines: law, psychology, philosophy, religion, anthropology and so on. But a problem arose when it began to seep into the general culture – or, as Brooks puts it, into ‘the orbit of political cant and corporate branding’. Not since the work of Freud, whose concepts of neurosis, the Oedipal and the unconscious quickly became common currency, has a piece of high theory so readily entered everyday language. The narratologists had given birth to a monster: George W. Bush announced that ‘each person has got their own story that is so unique’; ‘We are all virtuoso novelists,’ the philosopher Daniel Dennett wrote. What Brooks glumly calls ‘the narrative takeover of reality’ was complete.

It isn’t just that everyone now has a story; it’s that everyone is a story. Who you are is the narrative you recount about yourself. Whether the life history of someone forced into sex work reflects their true self, or whether self-narration might also be self-deception, are questions that seemingly don’t trouble this line of argument. What if someone tells contradictory stories about themselves? How do you decide which tales are true? You can’t resort to standards of evidence, coherence, plausibility and so on because these, too, are no more than a fable. Facts, Brooks argues, always come to us embedded in a narrative, which makes it hard to see how they can be used to verify or falsify it. The Russian commentator Margarita Simonyan says that all we have by way of truth is a host of competing anecdotes. This wouldn’t matter so much if Simonyan weren’t the director of the Kremlin’s TV channel. Reports that Vladimir Putin murders his opponents, according to this logic, are no more true or false than stories that he is the reincarnation of Peter the Great. If there is no way of adjudicating between conflicting accounts, those that are backed by the greatest muscle are likely to win out. Brooks rejects this ‘that’s just your story’ relativism, insisting on the difference between what actually happened and the way it is represented.

READ MORE

#literary criticism authors#writers#writing#branding#narrative#storytelling#political messaging#journalism#propaganda#plot#self authorship

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

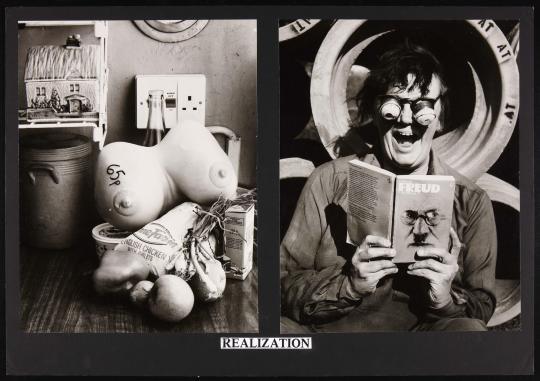

Photo by Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, 1981-92

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jo Spence: The Picture of Health?

___________________________________________________

In 1982, aged 48, photographer and activist Jo Spence was diagnosed with a cancerous tumour in her left breast. Half an hour after this initial diagnosis, she was unceremoniously informed by her doctor that she was to be treated by the surgical removal of her breast in its entirety. After contending with him, she was able to negotiate a lumpectomy surgery that, although minimised trauma to her body, meant she lost one third of her breast and was left scarred. Armed with her camera, Spence documented her treatment in the care of the National Health Service and her subsequent journey into holistic healthcare.

Spence collated her research and photography – often undertaken in collaboration with others – into an exhibition entitled ‘Picture of Health: alternative approaches to breast cancer’, which debuted at the Cockpit Gallery, London in January 1986.

Spence’s photographic rebellion against mainstream imagery rallied against the overarching narrative that, as breasts are solely for male enjoyment, breast cancer patients should focus on reconstructive surgeries or obtaining prostheses in order to be once more acceptable to the male gaze. Faith and Nygren deplore that ‘the experience of breast cancer is clearly influenced by the cultural emphasis on breasts as objects of male sexual interest and pleasure’.[1] Spence was also dismayed that the information pamphlets provided to breast cancer patients were ostensibly concerned with making what one has suffered socially acceptable; she notes advice was confined to ‘getting a prosthesis so your husband can go on loving you’ or ‘how to pretend you’re not ill to your family’. [2] The reality was, however, that approximately 20 per cent of patients still suffered severe anxiety, distress or depression one year after the removal of a breast, with intensive psychiatric therapy being required in 8 per cent of cases.[3]

By comparison, in a self-portrait featured in ‘The Picture of Health?’, Spence stands wearing only a motorcycle helmet and, in seemingly deliberate defiance, her lumpectomy scar is the focal point of the image. She displays the scarring from her surgery unashamedly, refusing to pander to the male gaze that dictates the breast is a mere ‘sexual decoration’ or to avoid making the patriarchal viewer uncomfortable. She wears a motorcycle helmet which, although adds a humorous touch of the bizarre to the photograph, also evokes the brutality of the cancer treatment that Spence has undergone. Women often suffer a ‘fear of not being accepted, loss of self-esteem, loss of sexual identity and loss of ‘femininity’ post mastectomy’[7] and here Spence’s image educates on the realities of orthodox breast cancer treatment, forcing us to address the trauma her body has undergone.

By Helen Walker - Postgraduate student in History of Art and Photography

________________________________________________________

[1] Faith and Nygren, ‘Breast Cancer: A Feminist View’, p.7

[2] Spence and Coward, ‘Body Talk?’, p.28

[3] Spence, ‘Body Beautiful or Body in Crisis’, p.12, quoting Patient Support Groups – the Mastectomy Association and the Breast Cancer Support Service (‘Cancer Care’, October 1985)

[4] J. Faith and A. Nygren ‘Breast Cancer: A Feminist View: Part II’, Off Our Backs, Vol.25, No.9 (October 1995), pp.6-7, p.6

#art#artist#photography#jo spence#photographer#feminist#feminist photography#feminism#collaboration#rosy martin#terry dennett#phototherapy#therapy#holistic health care#birkbeck#university of london#lecturer#socialist photography#radical photgraphy#feminist socialist#1970s movies#1908s#curator#curatorial#breast cancer#healthcare#empowerment#exhibtion#archive

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

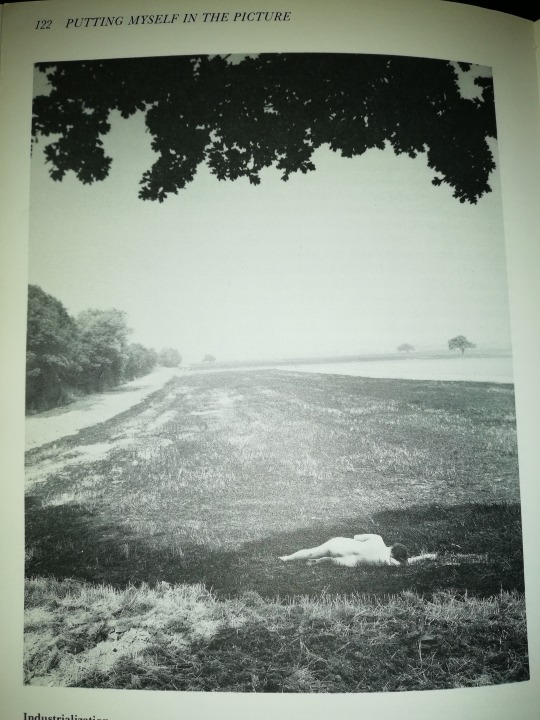

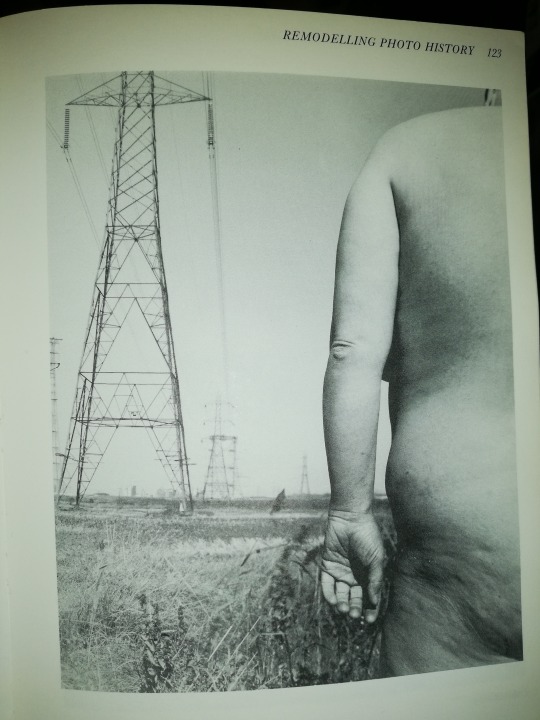

JO SPENCE & TERRY DENNETT. Remodelling Photo History (1982)

0 notes

Photo

Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, Final Project, 1991-92

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

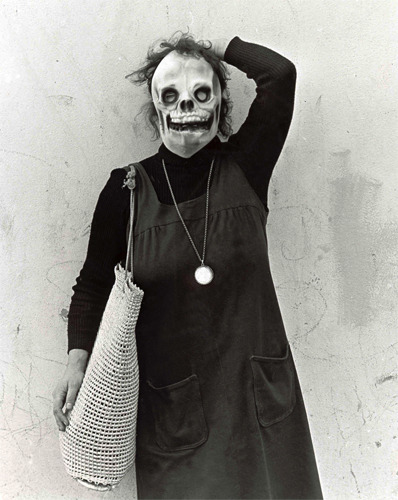

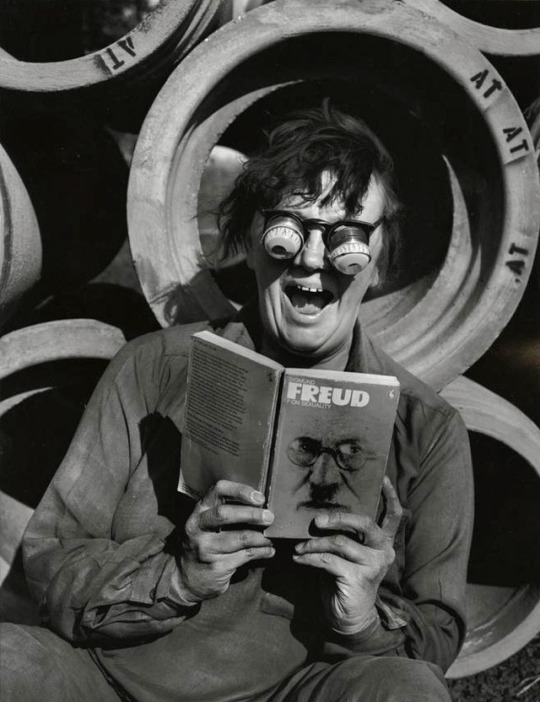

Jo Spence

Remodelling Photo History: Industrialization (1981–1982)

Black and white photograph

Collaboration with Terry Dennett

Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jo Spence, Untitled, from Libido Uprising (with Rosy Martin), 1989 © Terry Dennett and courtesy of the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

#jo spence#desire#red#self-portrait#photography#blood#english art#art#contemporary art#female artists#illness#drink all the sex there is#still die

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Source magazine article about Paul Hill/The Photographers Place Archive and others

What happens to a photographer's work when they are no longer around to look after it? Following some recent cases of national institutions accepting photographer's legacies Mark Bolland examines the prospects for the archives of prints and negatives they leave behind.

What happens to a photographer's work when they die and where do the photographs go? A cynic might say that in the UK the answer is probably 'nothing and nowhere', and they would be right, more often than not. However, the acquisition by the British Library of Fay Godwin's archive suggests that this bleak prognosis isn't always accurate and some other recent examples suggest that there is hope for those who expect archives of work by prominent photographers to find their way to national collections.

In the past the V&A have conscientiously collected work by Brandt and others, although they now concentrate on contemporary practitioners as it is considerably cheaper and they have not been able to purchase work at auction since the mid-90s for similar financial reasons. On the other hand, in the last few years Professor Paul Hill has taken the unusual step of enabling Birmingham Central Library to acquire his archive during his lifetime, and Edwin Smith's archive of 60,000 images and their copyright are now held by the Royal Institute of British Architects. Yet the record prices currently being paid for photographs and the expense and difficulty of preserving whole bodies of work, combined with a lack of policies or facilities on the part of many institutions, who are often further hampered by a lack of government support, mean that there are no guarantees about where a photographer's work will end up. This is an aspect of photographic practice in the UK that shows no evidence of coordination or strategy. To take two important figures in British photography as examples: this situation has meant that Jo Spence's archive is still looked after by her former partner Terry Dennett and Raymond Moore's archive was kept by his wife until she tried to dispose of it through an auction house. It is currently frozen in limbo due to a legal dispute.

Fay Godwin died three years ago and the British Library have now taken possession of about 11,000 of her photographs, contact sheets, negatives and letters. While she is mostly known for her poetic landscapes, Godwin also made many portraits of literary figures including Kingsley Amis, Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin. These and some accompanying correspondence between photographer and writers seem to have been instrumental in the decision to give the archive to the British Library, despite the fact that the National Media Museum in Bradford was trying to acquire the collection. Godwin's archive went to the British Library via the 'In Lieu of Inheritance Tax scheme' and is now the largest single collection that they hold. The 'In Lieu' scheme is run by the Museum Libraries and Archives Council (MLA) and is intended to save works of art of all kinds for the nation, by allowing estates to offset the value of their collections against tax. As John Falconer, Curator of Photographs at the British Library explains: 'The scheme accepts works of art or other collections and archives that are considered of national importance and the final destination of the items in question is decided by the MLA. The Godwin collection is the only archive that the Library has received via the route of the In Lieu scheme.' The MLA is the government's agency for museums, galleries, libraries and archives offering advice, support and resources. They are a non-departmental public body, sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. Launched in 2000, the MLA replaced the Museums and Galleries Commission and the Library and Information Commission and now has responsibility for the allocation of archives and collections via the 'In Lieu' scheme.Paul Hill at the Photographer's Place sorting through the Archive prior to Birmingham Library finalising its acquisition in 2005 - Courtesy Pete James, Birmingham Library and ArchivePaul Hill at the Photographer's Place sorting through the Archive prior to Birmingham Library finalising its acquisition in 2005 - Courtesy Pete James, Birmingham Library and Archive

The literary connection may well have been a factor in deciding the destination of the Godwin archive, as the British Library photography collection mainly consists of 19th century work, most notably a large selection of work by the pioneering WHF Talbot, and is, by its own admission, 'weaker for the modern period' and generally only seeks 'to acquire material which builds on its existing strengths.' By contrast, the National Media Museum has actively sought to acquire such collections but this task is increasingly difficult in what Greg Hobson, Curator of Photographs at the NMM, describes as a 'climate where the perceived value of photography is so high'. Apart from the photography market he also cites concerns common to many such institutions, such as space and staffing, that prevent the NMM from taking whole archives 'simply because they are donated'. All of which means that many precautions must be taken before donations can be accepted: 'We have to be confident that the work is culturally valuable in the context of our collection, in relatively good condition and with provenance in particular in relation to ownership and copyright.' That the Godwin and Edwin Smith archives meet all these criteria, but still did not end up in Bradford, only proves how difficult and uncertain the process of acquiring someone's archive can be, especially in the UK.

In the absence of strong governmental support, and usually without strict or organized policies, UK institutions are reliant on photographic collections simply landing in their laps. This seems to be exactly what happened in 2007, when Penelope Smail, daughter of painter, photographer and designer Curtis Moffat, 'generously gave his extensive archive' to the V&A. In fact it was no accident that the Moffat archive went to the V&A. Moffat was an American who lived in Britain for nearly twenty years and his first wife had consulted Cecil Beaton about what to do with the remains of the studio Moffat left behind in London when he returned to America, and Beaton had suggested the V&A. Astonishingly, the V&A have almost no acquisition budget, but they do have the facilities and are well equipped to administer such donations. The Moffat collection is now being sorted and archived, and highlights of the collection were showcased at the exhibition Curtis Moffat: Experimental Photography and Design 19231935 that ran from August 2007 to April 2008. Moffat was an interior designer and society photographer as well as an interesting experimental photographer who collaborated with Man Ray, and his archive contains over 1,000 photographic prints and negatives as well as press cuttings, scrap books and ephemera. And, as in the case of Godwin, it seems that things outside photography to some extent dictated the destination of this collection: Moffat's status as a 'pivotal figure in Modernist interior design' proved key to the V&A's acceptance of his legacy, just as Godwin's literary connections were instrumental in dictating the fate of hers.Paul Hill at the Photographer's Place sorting through the Archive prior to Birmingham Library finalising its acquisition in 2005 - Courtesy Pete James, Birmingham Library and ArchivePaul Hill at the Photographer's Place sorting through the Archive prior to Birmingham Library finalising its acquisition in 2005 - Courtesy Pete James, Birmingham Library and Archive

Cases such as the legacies of Godwin and Moffat suggest the lack of a national strategy and initiative on the part of some major institutions. The Tate is vague on such issues but is in the process of compiling an acquisitions policy, and the National Archives, based at Kew, only holds material from government departments, so they have lots of photographic material but not always by recognized photographers, although there are examples: Cecil Beaton, for one, was employed by the Ministry of Information during World War Two and these photos now reside at Kew. All of which tends to make the destination of a photographer's work something of a lottery once they are no longer around to take charge. Perhaps attempting to circumvent this problem, Professor Paul Hill sold his archive to Birmingham Central Library (BCL) in 2004. But again there is more to the collection than just one person's photos. Hill's collection includes work by Strand, Weston, Brandt and others, as well as photos documenting the lectures and workshops at The Photographer's Place, the study centre Professor Hill and his wife established in 1976 at their home in Bradbourne, Derbyshire. The Photographer's Place was the first permanent residential photography workshop in the country, and hosted numerous international photographers during its twenty year existence in itself enough for a valuable and interesting archive. However, Pete James at BCL suggests that it was not the big names or just the Photographer's Place archive that interested them in Hill's collection; rather it was the completeness of a collection which contains all sorts of books, ephemera and documents that provide a 'complete picture of one person's working life in photography' at a key moment for British photography and photography education. Hill was also judicious in his choice of institution; BCL has the only national collection of photography in a public library with over two million items in its collection and has been recognized by the MLA and awarded 'designated' status by them. This means that the collection has national and international significance as a library or archive. Only 38 collections have been 'designated' nationally in 28 institutions.Paul Hill, Enoch Powell and Bubble Gum Boy, Wolverhampton, 1970 - Paul Hill / Photographers' Place Archive, Birmingham Library and ArchivePaul Hill, Enoch Powell and Bubble Gum Boy, Wolverhampton, 1970 - Paul Hill / Photographers' Place Archive, Birmingham Library and Archive

There are, of course, examples of British institutions actively acquiring work by British photographers, of which the V&A's close ties to Bill Brandt is perhaps the best known. Having first bought 26 of Brandt's nudes in 1965, the V&A bought 201 more photographs by Brandt in 1978. Various others have been given as gifts since his death in 1983, and in 2003 they acquired two albums from 1928-39 compiled by Brandt's first wife containing some 400 photographs, mainly his early experiments.Paul Hill sorting through the Archive - Courtesy Pete James, Birmingham Library and ArchivePaul Hill sorting through the Archive - Courtesy Pete James, Birmingham Library and Archive

Such enthusiasm is rare though, and the haphazard ways in which the destinies of photographer's archives are decided has led one photographer to attempt to tackle the issue. Jem Southam has been making enquiries about this for three or four years now, meeting with a wide range of people connected to photography and discovering that there are 'no plans, no clear thinking and no policies' to deal with this in the UK. He suggests that the clearest example of how little interest people have taken in this issue in British photography circles can be highlighted by a comparison between the varying fortunes of two photographic legacies. One comes from the English Landscape photographer James Ravilious son of the artist Eric Ravilious who took over 80,000 images of rapidly disappearing rural life in Devon from the early 1970s until his death in 1999. The other is the American pioneer of colour landscape photography, Elliot Porter. Porter's estate was bequeathed to the Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas where it is housed in a centre that cost 25 million dollars; while Ravilious' legacy, although it is being properly looked after, is currently awaiting a permanent home in North Devon Records Office.The Paul Hill Archive on arrival at Birmingham Library - Courtesy Pete James, Birmingham Library and ArchiveThe Paul Hill Archive on arrival at Birmingham Library - Courtesy Pete James, Birmingham Library and Archive

Southam is putting together a research group to attempt to ensure that the same thing doesn't keep happening. Examples of how legacies are handled in the United States, where these things seem to be much better organized, may point to some answers. As may other fields, such as literature, where there is already an acceptance of the various issues, be they legal or practical, that institutions with an interest in archives of historical significance cannot ignore much longer. Jem Southam's research and Paul Hill's example suggest that it is not just institutions that must start taking more responsibility when it comes to legacies, but also photographers and artists themselves, who's job it is to organize their own work during their lifetime so that it is useful, useable and manageable when they are gone. Perhaps greater awareness of such issues on the part of institutions and practitioners will ultimately lead to not just to better practices, but also to a UK equivalent of the University of Arizona's Centre for Creative Photography, which houses over fifty archives by Adams, Weston, Callahan, Winogrand and other luminaries of US photography. This though, is a long way off.

0 notes

Text

JO SPENCE: WORK (PART 1 & 2)

PART 2

“The Picture of Health?“

“I realized with horror that my body was not made of photographic paper, nor was it an image, or an idea, or a psychic structure… it was made of blood, bones and tissue. Some of them now appeared to be cancerous. And I didn’t even know where my liver was located.“

- serija fotografija koja prati njezino putovanje kroz bolest i liječenje

“Cancer Shock, Photonovel“

- Kao odgovor na dijagnozu raka, Spence je proizvela diarističku seriju fotografskih snimaka koji su objedinili dokumentaciju i efemere u pokušaju da se kreću po složenim osjećajima bijesa i straha te da se bave pitanjima kontrole, prava pacijenata i alternativne terapije.

“Photo therapy”

- kroz ovu seriju fotografija Rosy Martin i Spence započinju svoju fototerapiju

- Martin i Spence stvorili su alat za osobnu terapiju, proizvodeći rad koji je subjektu omogućio kontrolu nad njihovim imidžom i predstavljanje vlastitih teških, često prethodno neizrečenih osjećaja i ideja.

- Surađujući i mijenjajući se, osoba pred kamerom bila je i subjekt i autor slike.

- nizom različitih serija; Spence je radila kroz niz osobnih povijesti i trauma, poput odlaska u bolnicu i osjećaja da je infantilirana -> njezin odnos s majkom i osjećaj napuštenosti dok je bila evakuirana tijekom rata i njezine emocionalne korijene prema obrascima prehrane.

-proširila Spenceovo ispitivanje i dekodiranje seksualnosti, obitelji i klase

- Spence je nastavila raditi na foto terapiji sa brojim drugim kolaboratorima/ terapeuta:

Libido Uprising (1989) is a series of photo therapy works produced with Rosy Martin and Spence’s partner David Roberts

Narratives of Dis-ease: Ritualised Procedures (1988–89) is a series of works produced with psychotherapist, Dr Tim Sheard

Cultural Sniper (1990), produced by Spence and David Roberts

“The Crisis Project: Scenes of the Crime”

- kolaborirala je sa Terry-jem Dennettom sve do svoje smrti

“ At an everyday level the work was also the result of having to confront a life-threatening illness and encountering the many taboos which surround the cancer patient. These twin poles then brought about a double ‘crisis of representation’ which we as photographers have continually tried to address. “

“‘Scenes of a Crime’ uses two genres: legal record photography (documentation of the scenes of a crime) and staged photography“

“The Final Project

“ Jo felt we should begin to tackle the question of aging and mortality. Her diagnosis of leukemia led us to formulate a final project based upon the notion of mortality and possible death. Initially, Jo thought of it as a ‘final’ project because it was going to be her last work in photography. It would include documentation of her treatments as well as photo theatre and photo therapy sessions on mortality and approaches to death in different cultures.During her second illness, photo therapy proved emotionally difficult, so a more allegorical approach evolved. The Final Project was our last collaborative project, and it also included David Roberts, who technically assisted her.“

“Untitled by Terry Dennett “

Jo Spence on a ‘good day’ shortly before her death, photographing visitors to her room at the Marie Curie Hospice, Hampstead

“Hospice Diaries“

- One of Jo Spence’s major personal projects was the documentation of her everyday life, the good and the bad.

- For this purpose she developed ideas gained through her studies of three genres — the family album, life writing and scrapbooking to create what she called a workbook, a cheap A3 news cutting books filled with photographs and commentary. She put these books together on an almost weekly basis from the 1980s when she got cancer till a few days before her death in the Marie Curie hospice in 1992.

the Workbook is both a personal and private work and a public anthropological document designed to survive the death of the author.

“Metamorphosis“

- Metamorphosis uses another older technique called ‘flip printing.’ The image is printed both ways (right-side up and upside down, reversed) and joined together. This can be pre-visualised by placing a mirror at right angles across an image so that both the image and its reflection slowly merge

- Metamorphosis is also a one-of-a-kind series produced after Jo’s death in accordance with our previous discussions about pre and post-death collaboration

- ideja je nastala prema ideji Jeremy-ja Benthama

0 notes

Text

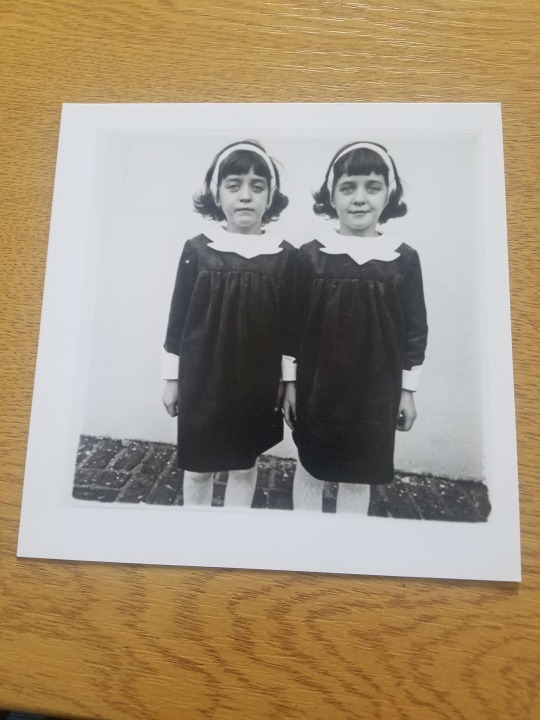

Week 4: Misbehaving Bodies + Portraits

In Class Photo Response

I believe that this is a portrait as its main focal point is of two people, guiding the viewer directly to their faces. Their emotions are clearly depicted and described throughout the photograph through the black and white coloring composition. The tone of this photo is unsettling, due to the hazy, strange look the girls have in their eyes. This coloring option presents a photograph back in time, possibly resembling a specific time period (50s-70s). Lighting also contributes to the overall setting and emotional tone of the photograph as it is hard to distinguish throughout the picture and adds to the drab feeling. The posture of the children conveys they are getting their picture taken my their parents/guardian, where the twin on the left is not so thrilled compared to her sister. While the background is simply a white wall, and there is no clear object present within the middle distance, the twin girls are in the foreground.

Misbehaving Bodies Exhibition

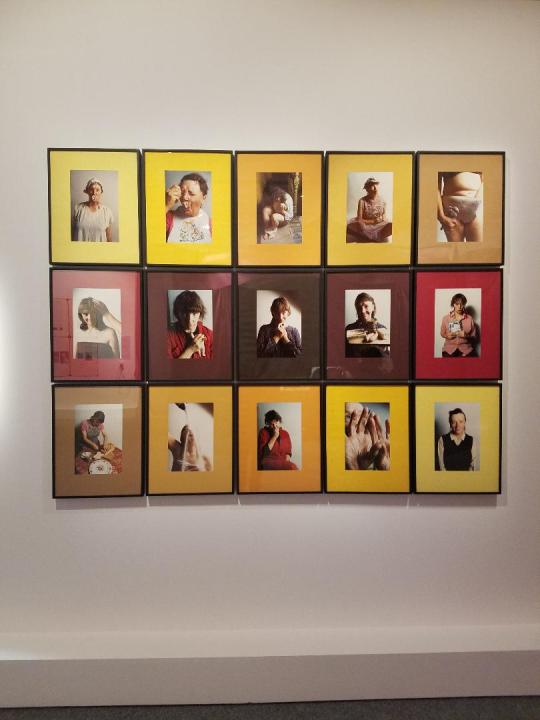

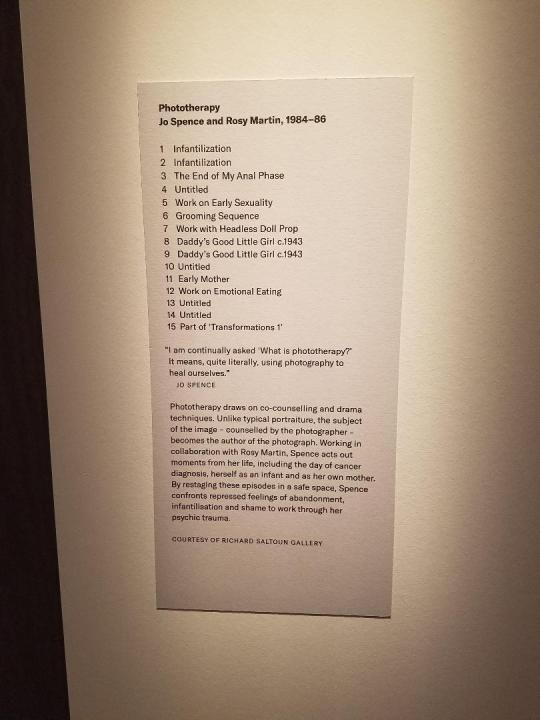

Phototherapy

Jo Spence and Rosy Martin

1984-86

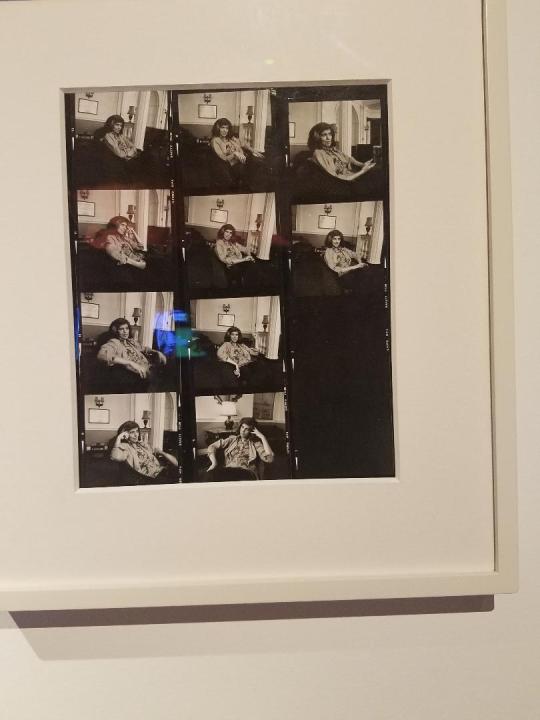

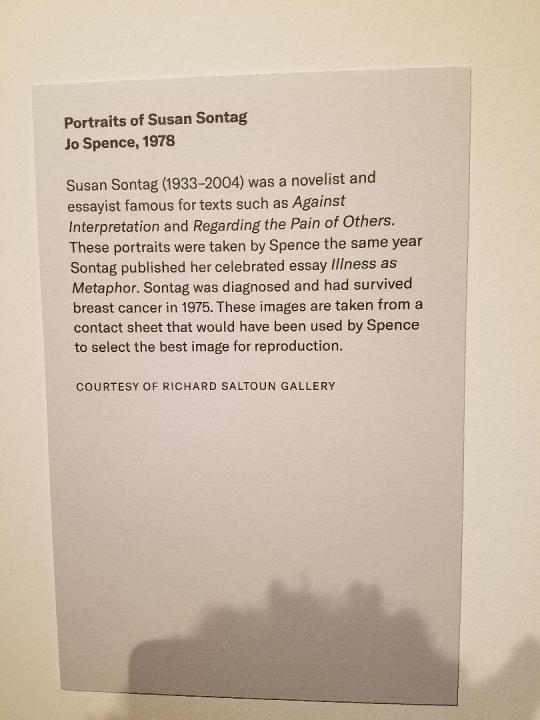

Portraits of Susan Sontag

Jo Spence

1978

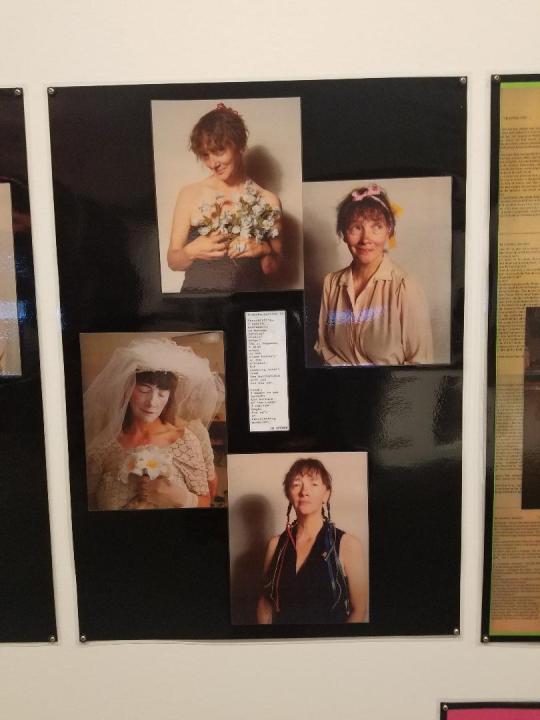

The Picture of Health?

Jo Spence, Terry Dennett, Maggie Murray, & Rosy Martin

1982-86

Jo Spence and colleagues emphasize the internal struggles that cancer patients experience throughout their lives before cancer, during treatment, and the complexities of living with the disease. I believe she is trying to target the hidden emotions those with untreatable diseases have to highlight the joys of life and distance herself from her cancer.

I consider these pieces to be portraits, because viewers truly experience the focal point (Jo Spence) through the stages of cancer. We get to focus on her varying emotions, making each shot unique to her various experiences. She is usually the subject of the photograph, keeping the viewer glued to her.

Spence’s work is highly effective in developing a sense of the emotional toll cancer plays throughout her life. The different facial and body expressions shown in “Phototherapy” and “The Picture of Health?” pinpoint how she lives with cancer and why her life was important to document. I develop a relationship with her without exchanging any dialogue, because through the use of visuals, she tells a story. With this in mind, Spence’s honest and “raw” displays of her cancer via her photographic techniques exude an unapologetic message of the realities that many people have to face.

Captions

Each photo is given a name, presumably cognizant of the moments she’s experienced with the disease. This provides meaning to understand what she was going through. She confronts her inner demons and insecurities by reliving these moments.

Knowing that one of Spence’s idols shared an experience with her, makes the motivation behind this photo more fulfilling.

Here Spence highlights the importance of coming to grips with your illness and not idolizing it. Instead of portraying herself as a victim, she displays herself as strong and able to get through it, but also remaining aware of the harshness cancer brings to the patient.

I believe that the meaning behind this exhibition is to display the realities that people with cancer and any other debilitating disease face during their everyday lives. Coming to terms with disease, whether it be through reliving moments, relating to and developing relationships with others who share the same experiences, or internalizing the harshness of not knowing how long you’ll live, is an eye opening moment, allowing viewers to understand how trauma influences life decisions.

Portrait

Inspiration

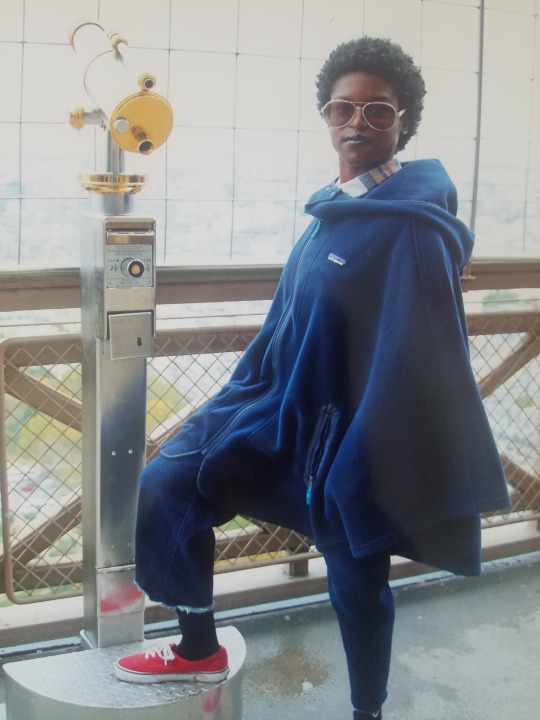

I enjoy the use of objects and background in this photograph. The darkness leads the viewer straight to the woman’s face, which is highly contrasted against her surroundings.

My Portrait

Here, I wanted to mimic the same pose and overall expression that the woman portrayed. She gives off a smug look that looks distant. I focused primarily on the composition and objects in this photo, because they provided the most context for the emotional mood of the photo. I did not like the use of black and white, so instead used color to emphasize the importance of the environment and details of the objects around me. The dirt on my shoes and the light reflecting from the telescope provide extra detail. The simplicity of this photo is what draws me to it. It does not display much, which allows for the viewer to construct their own story, which was the highlight I wanted to portray.

0 notes

Text

Jo Spence

Photographer, writer and self-styled 'cultural sniper' Jo Spence at Tate Britain PATRIZIA DI BELLO

Lecturer Patrizia Di Bello discusses the inspiring and influential work of photographer Jo Spence Rosy Martin and Jo Spence undertaking a photo therapy session using childhood portraits from their family albums Rosy Martin and Jo Spence undertaking a photo therapy session using childhood portraits from their family albums © Jo Spence, courtesy Terry Dennett and Richard Saltoun Gallery, London The first photograph I took after I finished college was of the cover of a book, Putting Myself in the Picture by Jo Spence, the British photographer, writer and ‘cultural sniper’ – as she described herself. It was the late 1980s, ‘re-photography’ was in and Roland Barthes had long declared the death of the author, but I still wanted to pay homage to the texts that were crucial to what I was thinking about photography. Her work had had a big impact on me while I was a student. It taught me how even the most simple and natural photographs are affected by the cultural and economic circumstances in which they are taken and circulated. Her way of working in collaboration with other people, and annotating old photographs into new meanings, made me realise how all images are in some way a collaboration, involving not only sitters and photographers, but also the people who will go on to include them in albums, publications or displays, talk or write about them, and decide to pass them on or throw them away.

Other women artists put themselves in the picture using photography – Ana Mendieta, Annette Messager, Helen Chadwick and Cindy Sherman are just a few examples – but Spence’s work has a raw, hard-hitting simplicity that stands out, perhaps because it was made not for art but to change the world, even if through education rather than revolution.

The photographs she produced with Terry Dennett (a former partner and longterm collaborator) and Rosy Martin are still compelling for their liberating disregard of the preoccupation with beauty, elegance, or just ‘cool’ that is ever-present in photographic culture. The courage with which they confront fears and contradictions in relation to embodied sexual identity and our desires as workers and consumers is almost alarming. They make us question boundaries between the personal and the political, the private and the public, and the extent to which we can ever be in control of our body, our image, or ourselves. The commitment involved in these collaborations is almost palpable, a way of living and working embedded in a wider political and feminist project whose urgency seems only intensified by Spence’s heightened awareness of her own mortality. Yet even as they address the most serious of themes – unemployment, oppression, illness – the images can still be funny and playful.

Rosy Martin and Jo Spence undertaking a photo therapy session ‘Rosy and I begin a photo therapy session in which we examine the silences and absences of our school photos.’ – Jo Spence © Jo Spence I met her a few times, most memorably when she invited me to her home so I could show her my portfolio. She had been one of the external examiners where I studied for a degree in photography, and it is probably thanks to her that I graduated with first-class honours. As someone who had first tried (and failed) to get into college with a portfolio of ‘family photographs’ taken by other people, I too was interested in exploring political and photographic autobiography. Spence was immensely generous with her time and advice – which, with the arrogance of youth, I mostly disregarded. Her influence was crucial, however, when I became more interested in writing than taking pictures. It was while looking at her reworking of the family album that I first wondered about its history as a women’s genre, a curiosity that eventually resulted in my first book, Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England. As I discovered, writing history can also be a way to add new meanings to old photographs.

Recently, Dennett donated to Birkbeck (where I now teach history of photography) a collection of books and journals that had belonged to both him and Spence. As new students delve into Spence’s work, I once again discover just how inspiring and empowering it can be, not just as history, but as a means to understand the present in ways that make us less passive towards our circumstances.

Photographs by Jo Spence are on display at Tate Britain.

Patrizia Di Bello is a lecturer in history and theory of photography in the department of history of art at Birkbeck, University of London. With thanks to Rosy Martin and Terry Dennett.

SEE ALSO

Tom Wood Bottlenose Chelsea Reach (from Looking for Love) 1985 TATE ETC We are here: Photographing Britain David Campany , Nigel Shafran , Homer Sykes , Martin Parr , Anna Pavord , Viktor Kolár , Kathryn Hughes , Brett Rogers and Tessa Codrington

To coincide with Tate Britain’s photographic survey of Britain’s social history, Tate Etc. asked a selection of writers, curators and ... Jo Spence, ‘The Highest Product of Capitalism (after John Heartfield)’ 1979 BP Spotlight: Jo Spence BP spotlight: Jo Spence display at Tate Britain Monday 19 October 2015 – Autumn 2016

0 notes

Photo

From Remodelling Photo History, Photo by Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, 1979-82

277 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photography & Politics

In the publications Photography/Politics: One (1979) and Photography/Politics: Two (1986), Jo Spence as part of Photography Workshop sought, through an expansive definition of the titular terms, to address interferences between photography and politics across the history of the medium. Through also focusing on the role of institutions, and particularly as financing entities, the editors and contributors demonstrate the multifarious ways that we are unconsciously subject to the camera’s and photography’s power. While our consciousness of this potential may be comparatively better understood in today’s photographically saturated and occasionally more sceptical cultures, pondering on the revelations of Photography/Politics proves nonetheless instructive.

For instance, we learn that ways we are presented and present ourselves to the camera are often already determined by internalised modes of seeing, behaving and image-making through our exposure to portrayals in the media and advertising. Uncomfortably at times, the combinations of writing and images in the two volumes of Photography/Politics uncover the habits of presentation we willingly if unwittingly repeat as a consequence of playing photographic subject to a camera. How do we learn these behaviours?

For one example, consider the difference between school portraits of Spence and her collaborator Rosy Martin available here. On our right, Spence holds a shot of a decontextualized head for our inspection, whereas Martin presents us with a posed and staged picture of the studious pupil, Rosy, pencil in hand. What control did the figures in these ostensibly innocent pictures of schoolchildren have over their photographed selves? And why did ways of staging UK school portraiture evolve like this in the years intervening between Spence’s and Martin’s photographs? What modes of self-presentation might these photographic experiences have inspired in the two young subjects?

Well before an image is processed and re-presented for consumption, decisions of selection and editing lie at the core of how we behave with and for the camera. What props, what pose? When this picture is looked at in future, what past do you want it to tell that you had? Most photographs—and especially family, domestic and commercial ones—have been informed by a preference for demonstrating our better or aspirational selves, in which we must acknowledge the social purpose of photographs to both record and generate an aspiration. Spence and her collaborators sought to work against this grain and in that hoped that their audiences would be better placed to engage with and take photographs of themselves and others.

By Christie Johnson - History of Art with Photography

#artist#photography#photographer#jo spence#terry dennett#rosy martin#phototherapy#feminist photography#feminist#feminism#collaboration#therapy#birckbeck#politics#photography and politics#university of london#socialist photography#radical photography#activist#activism#feminist socialist#activist photography#curator#curatorial#free images#postgraduate

0 notes

Photo

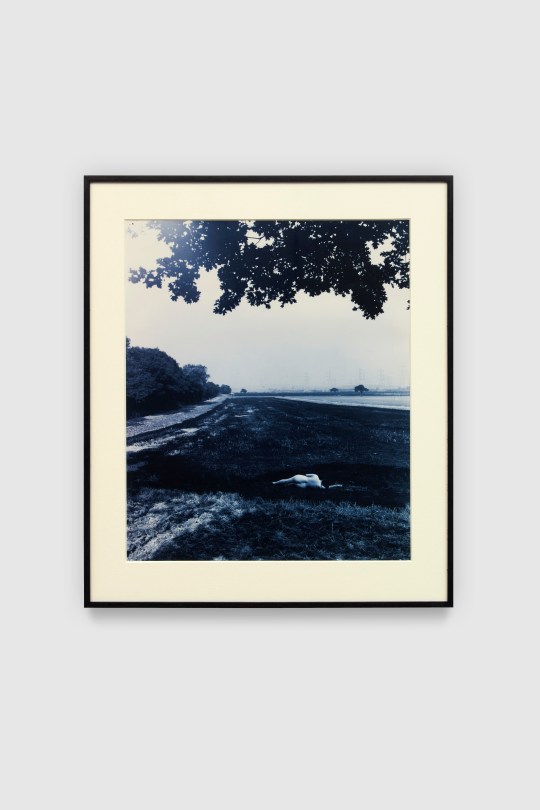

The Final Project ['End Picture' Floating], Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, 1991-1992

In this work, Jo Spence and Terry Dennett are trying to portray someone’s life slipping away, like death is slowly sinking to the bottom of a swimming pool, watching as the surface of the swimming pool slips away in much the same way life gets murkier and farther away as death approaches. I consider this work a portrait because it captures how the artist was feeling about her approaching death. It tells us about who she is and paints a picture of her feelings, something I think is characteristic of portraiture. Seeing a lot of her work together made me more reflective on life and death and what it means to be truly alive. It made me ponder the feebleness of life and gave me a deeper appreciation for living in the present as we do not always know what is before us. This photo helps convey that the subject is on the brink of life and death through the use of blur in the photo, never fully bringing into focus the image. Having the subject pose in a pool also shows that she feels almost out of control, just floating along with the slight current the same way she is dazed and currently floating through life. The caption of this photo stated that this picture was created by merging two separate photographs Pence took, giving it that murky look. This made me see the picture as a combination of her current emotions with her previous feelings from when she was younger, indicating her reflection on her entire life as she prepares to die.

*********************************************************************

Dying Under Your Eyes, Oreet Ashery, 2019

With her video documenting her father’s descent into disease, illness, and death, it can be seen that through this project she was trying to tell people to appreciate those we love and our own lives while we are still alive, to not let life pass us by without ever fully living. I would consider this to be a portrait because it explains to the viewers the inner workings and emotions behind of her parents’ lives, especially in her father’s last years. It offers insight to who they are as people, something I personally believe is a main function of portraits. Seeing her work together has the effect of showing how chaotic life is, a series of ups and downs and unexpected turns. These videos convey that despite his illness and approaching death, her father fought to his last breathe to live life to the fullest and fully take advantage of everything this world has to offer. This will to live, this fullness of life, shows that he approached death with a sense of knowing that this was not the end of his story, just that the next chapter was about to begin. After reading the artist’s caption of the video in which she stated that care and mourning were also a focus of the motion picture, it can be see that she also wanted to reflect how death affects those who live on after our loved ones pass away, that mourning can begin before death and is lasting.

*******************************************************************

I believe the overall message of the exhibition was that our human bodies are so fragile and that while we can in no way totally escape the hardships of physical ailment, there is beauty in death and in leaving a lasting mark on those around you, who you are and everything you believe not just disappearing once your heart stops beating. This message was influenced by the display of the exhibition, each piece being displayed in an almost first-person point of view, making each message more personal and providing more emotional impact on the viewer. It was displayed in a manner that was very raw, open, and real, making it feel more like someone’s feelings you were experiencing than just a picture or words on a page. It made you examine the artists’ feelings in the context of yourself, giving one great insight to their own mortality whether they are young or old, healthy or sick.

0 notes

Photo

Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, Final Project, 1991-92

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

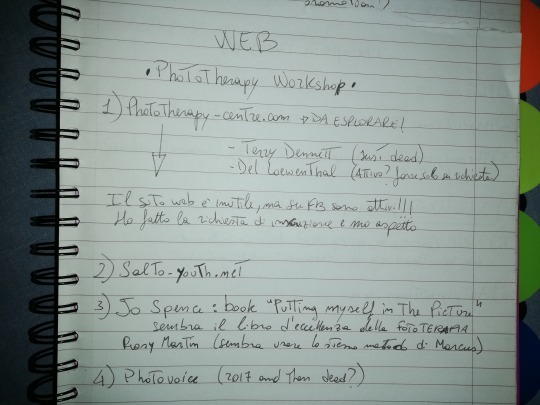

3.03 (6.20 h) Web research on: Phototherapy workshop

The second step of my research it has been focused on the web surfing.

I tried to google some keywords and analyze and study the results.

Using “Phototherapy workshop” at first try, the web dragged me into a huge amount of information I didn’t believe it was possible to find. I for sure found lots of material to use for my dissertation proposal, but also as a reference to understand the field I am studying.

The very first result that came up was https://phototherapy-centre.com/ , a very well done website commissioned by Judy Weiser, who seems to be the most influential american pioneer of the use of photography in psychotherapy.

This is the list of the menu’ sections:

Therapeutic Photography (info about the difference between therapeutic photography and phototherapy)

Related Techniques (such as video therapy, painting and so on)

Who is Doing What, Where? (in here we can find a HUGE list of names from people of all over the world who make use of photography in their art therapy practice, having access to their personal data, website and events)

Related Websites/Webpages (other pages related to phototherapy)

Weiser Bio & Publications (in here we can get the full list of Judy Weiser’s pubblications and her bio)

PhotoTherapy Blog (in here Judy updates the readers about the event she runs, posting images from her workshops, lectures or other kind of event she finds relevant for the blog)

PhotoTherapy Archives ( Judy Weiser is currently working to organize, catalogue, and digitize the PhotoTherapy Archives to allow easier public access to its wealth of history and information on an ongoing basis into the future, and at no cost to users)

More Information (in here we can find more historical information about phototherapy and also related dissertations and thesis)

Facebook Group (the Facebook group is closed to the public, probably for privacy issues, therefore I sent the request to be accepted)

“PhotoTherapy techniques are therapy practices that use people’s personal snapshots, family albums, and pictures taken by others (and the feelings, thoughts, memories, and beliefs these photos evoke) as catalysts to deepen insight and enhance communication during their therapy or counselling sessions (conducted by trained mental health professionals), in ways not possible using words alone.”

Reading through the website and going to every single name one by one in the section who is doing what? where? There have been 2 names that caught my attention specifically: Terry Dennett and Del Loewenthal.

“Terry Dennett, London, England, (now deceased) is a long-time Photographic/Political Activist who for many years collaborated with Therapeutic Photography Pioneer Jo Spence (now deceased). Terry is the Curator of the “Jo Spence Memorial Archive” in London, England, through which he continues to assist students and others world-wide who are interested in Spence’s unique kind of therapeutic photography (which she first called “photo-therapy” and later both “camera therapy” and “autobiographical photography”)”

Del Loewenthal, London, England, is the Director of “The Research Centre for Therapeutic Education” at the University of Roehampton, where he has a Chair in Psychotherapy and Counselling and is Convener of an MSc and doctoral programmes. Del’s publications include being the Editor for both the book “Phototherapy and Therapeutic Photography in a Digital Age” and the special issue of the European Journal of Psychotherapy and Counselling on “Phototherapy and Therapeutic Photography”. Del has researched the use of PhotoTherapy techniques in working with young people aiding management development and developing the emotional learning of prisoners. He also trains counsellors, psychotherapists and art psychotherapists in PhotoTherapy techniques. He is the lead partner in Grundtvig’s EU-funded “Phototherapyeurope in Prisons” Project, which aims to develop the use of phototherapy within EU prisons in promoting the emotional learning and well-being of prisoners. This includes the setting up of a post-training database through which trainee practitioners can input evaluations of their use of phototherapy, enabling data to be collected on the impact of the training and the use by practitioners in prisons, a five-day training programme and the October, 2014 Conference “Phototherapyeurope in Prisons and Elsewhere” in London

It is king of shocking to see how many Italian people are actually into phototherapy and how little it is actually known or thought in school about this practice. It will something I will inform myself better about, for sure.

Meanwhile, I will put this website in pause and I will carry on with the research. Overall I can definitely say that it is a very useful website full of information ready to be used as support or reference. I will get back to it for my dissertation proposal writing.

Carrying on with the research, the second website I found interesting it is https://www.salto-youth.net/:

SALTO-YOUTH stands for Support, Advanced Learning and Training Opportunities for Youth. It works within the Erasmus+ Youth programme, the EU programme for education, training, youth and sport.

What is SALTO-YOUTH?

SALTO-YOUTH is a network of six Resource Centres working on European priority areas within the youth field.As part of the European Commission's Training Strategy, SALTO-YOUTH provides non-formal learning resources for youth workers and youth leaders and organises training and contact-making activities to support organisations and National Agencies (NAs) within the frame of the European Commission's Erasmus+ Youth programme and beyond.

This website it does not seem to be as important as the previous one, but it is interesting the fact that it sponsors trainings in photographic art to enhance creativity.

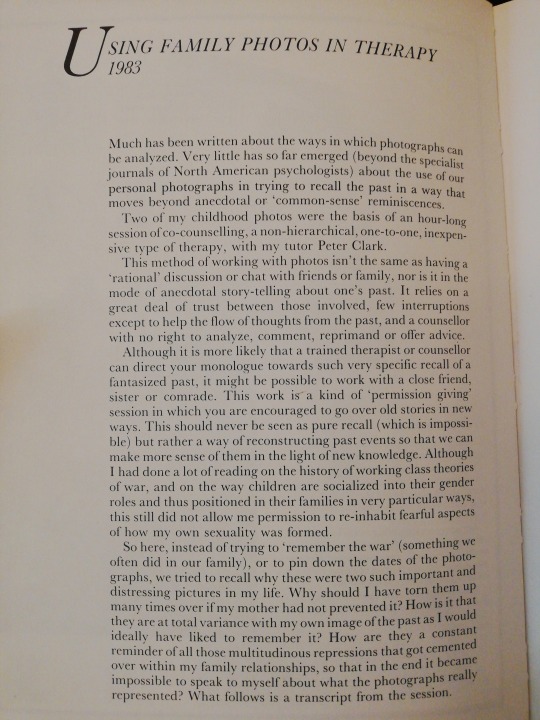

The third result I found it was a suggestion of Jo Spence book “Putting myself to picture”. This is a book I borrowed from the library during a random research for my dissertation and it looks like being one of the anthem books about the role of photography in therapy. In the book is also mentioned Rosy Martin, who seems to practice phototherapy as Marcus does, so I believe it would be a good idea to do more researches about her and her techniques.

The last useful result I found it was the website https://photovoice.org/, which promotes photography for social change.

Our vision and mission

PhotoVoice’s vision is for a world in which everybody has the opportunity to represent themselves and tell their own story

Our mission is promote the ethical use of photography for positive social change, through delivering innovative participatory photography projects. By working in partnership with organisations, communities, and individuals worldwide, we will build the skills and capacity of underrepresented or at risk communities, creating new tools of self-advocacy and communication.

Why photography?

Photography is a highly flexible tool that crosses cultural and linguistic barriers, and can be adapted to all abilities. Its power lies in its dual role as both art form and way to record facts.It provides an accessible way to describe realities, communicate perspectives, and raise awareness of social and global issues.Its low cost and ease of dissemination encourages sharing and increases the potential to generate dialogue and discussion.

It seems to be a pretty useful website where to look for info about photography in society and its alternative use, so I will keep it in mind as a reference source to look up to when in needed of information.

0 notes