#tableskills

Text

Homebrew Mechanic: Meaningful Research

Being careful about when you deliver information to your party is one of the most difficult challenges a dungeonmaster may face, a balancing act that we constantly have to tweak as it affects the pacing of our campaigns.

That said, unlike a novel or movie or videogame where the writers can carefully mete out exposition at just the right time, we dungeonmasters have to deal with the fact that at any time (though usually not without prompting) our players are going to want answers about what's ACTUALLY going on, and they're going to take steps to find out.

To that end I'm going to offer up a few solutions to a problem I've seen pop up time and time again, where the heroes have gone to all the trouble to get themselves into a great repository of knowledge and end up rolling what seems like endless knowledge checks to find out what they probably already know. This has been largely inspired by my own experience but may have been influenced by watching what felt like several episodes worth of the critical role gang hitting the books and getting nothing in return.

I've got a whole write up on loredumps, and the best way to dripfeed information to the party, but this post is specifically for the point where a party has gained access to a supposed repository of lore and are then left twiddling their thumbs while the dm decides how much of the metaplot they're going to parcel out.

When the party gets to the library you need to ask yourself: Is the information there to be found?

No, I don't want them to know yet: Welcome them into the library and then save everyone some time by saying that after a few days of searching it’s become obvious the answers they seek aren’t here. Most vitally, you then either need to give them a new lead on where the information might be found, or present the development of another plot thread (new or old) so they can jump on something else without losing momentum.

No, I want them to have to work for it: your players have suddenly given you a free “insert plothook here” opportunity. Send them in whichever direction you like, so long as they have to overcome great challenge to get there. This is technically just kicking the can down the road, but you can use that time to have important plot/character beats happen.

Yes, but I don’t want to give away the whole picture just yet: The great thing about libraries is that they’re full of books, which are written by people, who are famously bad at keeping their facts straight. Today we live in a world of objective or at least peer reviewed information but the facts in any texts your party are going to stumble across are going to be distorted by bias. This gives you the chance to give them the awnsers they want mixed in with a bunch of red herrings and misdirections. ( See the section below for ideas)

Yes, they just need to dig for it: This is the option to pick if you're willing to give your party information upfront while at the same time making it SEEM like they're overcoming the odds . Consider having an encounter, or using my minigame system to represent their efforts at looking for needles in the lithographic haystack. Failure at this system results in one of the previous two options ( mixed information, or the need to go elsewhere), where as success gets them the info dump they so clearly crave.

The Art of obscuring knowledge AKA Plato’s allegory of the cave, but in reverse

One of the handiest tools in learning to deliver the right information at the right time is a sort of “slow release exposition” where you wrap a fragment lore the party vitally needs to know in a coating of irrelevant information, which forces them to conjecture on possibilities and draw their own conclusions. Once they have two or more pieces on the same subject they can begin to compare and contrast, forming an understanding that is merely the shadow of the truth but strong enough to operate off of.

As someone who majored in history let me share some of my favourite ways I’ve had to dig for information, in the hopes that you’ll be able to use it to function your players.

A highly personal record in the relevant information is interpreted through a personal lens to the point where they can only see the information in question

Important information cameos in the background of an unrelated historical account

The information can only be inferred from dry as hell accounts or census information. Cross reference with accounts of major historical events to get a better picture, but everything we need to know has been flattened into datapoints useful to the bureaucracy and needs to be re-extrapolated.

The original work was lost, and we only have this work alluding to it. Bonus points if the existent work is notably parodying the original, or is an attempt to discredit it.

Part of a larger chain of correspondence, referring to something the writers both experienced first hand and so had no reason to describe in detail.

The storage medium (scroll, tablet, arcane data crystal) is damaged in some way, leading to only bits of information being known.

Original witnesses Didn’t have the words to describe the thing or events in question and so used references from their own environment and culture. Alternatively, they had specific words but those have been bastardized by rough translations.

Tremendously based towards a historical figure/ideology/religion to the point that all facts in the piece are questionable. Bonus points if its part of a treatise on an observably untrue fact IE the flatness of earth

#homebrew mechanic#d&d mechanics#research#tableskills#tabletop inspiration#dm tip#dm advice#exposition

462 notes

·

View notes

Video

Feed on chicken tenders in your car.... Only if you Savage tho #carnivore #fuckvegetarians #Savagelife #tableskills #nohands #fangs

0 notes

Text

Tableskills: Making a Game of It

Recently I learned a bit of an unspoken truth that I'd brushed up against in my many years of being a dungeonmaster that I'd never seen put into words before: If you want to liven up whatever's going on in your adventure, figure out a way to engage the players in some kind of game. It's simultaneously the best way to provide a roadblock while making your player's victories feel earned.

This might seem redundant, since you're already playing d&d but give a moment of thought to exactly what portions of d&d are gamified. Once you learn your way around the system, it becomes apparent that D&D really only has three modes of play:

Pure roleplay/storytelling, driven by whatever feels best for the narrative. Which is not technically a game, nor should it (IMO) be gamified.

Tactical combat with a robust rules system, the most gamelike aspect.

A mostly light weight skills based system for overcoming challenges that sits between the two in terms of complexity.

The problem is that there's quite a lot of things that happen in d&d that don't fall neatly into these three systems, the best example being exploration which was supposed to be a "pillar" of gameplay but somehow got lost along the way . This is a glaring omission given how much of the core fantasy of the game (not to mention fantasy in general) is the thrill of discovery, contrasted with the rigours of travelling to/through wondrous locations. How empty is it to have your party play out the fantasy of being on a magical odyssey or delving the unknown when you end up handwaving any actual travel because base d&d doesn't provide a satisfying framework for going from A to B besides skillchecks and random encounters (shameless plug for my own exploration system and the dungeon design framework that goes with it).

The secret sauce that's made d&d and other ttrpgs so enduring is how they fuse the dramatic conventions of storytelling with the dynamics of play. The combat system gives weight and risk to those epic confrontations, and because the players can both get good at combat and are at risk of losing it lets them engage with the moment to moment action far more than pure narration or a single skill roll ever could.

I'm not saying that we need to go as in depth as combat for every gamified narrative beat (the more light weight the better IMO) but having a toolbox full of minigames we can draw upon gives us something to fall back on when we're doing our prep, or when we need to improvise. I've found having this arsenal at hand as imortant as my ability to make memorable NPCs on the fly or rework vital plothooks the party would otherwise miss.

What I'd encourage you as a DM to do is to start building a list of light weight setups/minigames for situations you often find yourself encountering: chase scenes, drinking contests, fair games, anything you think would be useful. Either make them yourself or source them from somewhere on the web, pack your DM binder full of them as needed. While not all players are utterly thrilled by combat, everyone likes having some structured game time thrown in there along with the freeform storytelling and jokes about how that one NPC's name sounds like a sex act.

A quick minigame is likewise a great way to give structure to a session when your party ends up taking a shortcut around your prepared material. Oh they didn't take that monster hunter contract in the sewers and instead want to follow up on rumours about a local caravan? The wagon hands are playing a marble game while their boss negotiates with some local mercahnts, offering to let the party play while they wait. The heroes want to sail out to the island dungeon you don't have prepped yet? Well it looks like the navigator has gone on a bit of a bender, and the party not only need to track them down but also piece together where they left the charts from their drunken remembrances as a form of a logic puzzle.

Artsource

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tableskills: Creating Dread

I've often had a lot of problems telling scary stories at my table, whether it be in d&d or other horror focused games. I personally don't get scared easily, especially around "traditionally horrifying" things so it's hard for me to recreate that experience in others. Likewise, you can't just port horror movie iconography into tabletop and expect it to evoke genuine fear: I've already spoken of being bored out of my mind during the zombie apocalypse, and my few trips into ravenloft have all been filled with similar levels of limp and derivative grimdark.

It took me a long time (and a lot of video essays about films I'd never watched) to realize that in terms of an experience fear is a lot like a joke, in that it requires multiple steps of setup and payoff. Dread is that setup, it's the rising tension in a scene that makes the revelation worth it, the slow and literal rising of a rollercoaster before the drop. It's way easier to inspire dread in your party than it is to scare them apropos of nothing, which has the added flexibility of letting you choose just the right time to deliver the frights.

TLDR: You start with one of the basic human fears (guide to that below) to emotionally prime your players and introduce it to your party in a initially non-threataning manor. Then you introduce a more severe version of it in a way that has stakes but is not overwhelmingly scary just yet. You wait until they're neck deep in this second scenario before throwing in some kind of twist that forces them to confront their discomfort head on.

More advice (and spoilers for The Magnus Archives) below the cut.

Before we go any farther it's vitally important that you learn your party's limits and triggers before a game begins. A lot of ttrpg content can be downright horrifying without even trying to be, so it's critical you know how everyone in your party is going to react to something before you go into it. Whether or not you're running an actual horror game or just wanting to add some tension to an otherwise heroic romp, you and your group need to be on the same page about this, and discuss safety systems from session 0 onwards.

The Fundamental Fears: It may seem a bit basic but one of the greatest tools to help me understand different aspects of horror was the taxonomy invented by Jonathan Sims of The Magnus Archives podcast. He breaks down fear into different thematic and emotional through lines, each given a snappy name and iconography that's so memorable that I often joke it's the queer-horror version of pokemon types or hogwarts houses. If we start with a basic understanding of WHY people find things scary we learn just what dials we need turn in order to build dread in our players.

Implementation: Each of these examples is like a colour we can paint a scene or encounter with, flavouring it just so to tickle a particular, primal part of our party's brains. You don't have to do much, just something along the lines of "the upcoming cave tunnel is getting a little too close for comfort" or "the all-too thin walkway creaks under your weight ", or "what you don't see is the movement at the edge of the room". Once the seed is planted your party's' minds will do most of the work: humans are social, pattern seeking creatures, and the hint of danger to one member of the group will lay the groundwork of fear in all the rest.

The trick here is not to over commit, which is the mistake most ttrpgs make with horror: actually showing the monster, putting the party into a dangerous situation, that’s the finisher, the punchline of the joke. It’s also a release valve on all the pressure you’ve been hard at work building.

There’s nothing all that scary about fighting a level-appropriate number of skeletons, but forcing your party to creep through a series of dark, cobweb infested catacombs with the THREAT of being attacked by undead? That’s going to have them climbing the walls.

Let narration and bad dice rolls be your main tools here, driving home the discomfort, the risk, the looming threat.

Surprise: Now that you’ve got your party marinating in dread, what you want to do to really scare them is to throw a curve ball. Go back to that list and find another fear which either compliments or contrasts the original one you set up, and have it lurking juuuust out of reach ready to pop up at a moment of perfect tension like a jack in the box. The party is climbing down a slick interior of an underdark cavern, bottom nowhere in sight? They expect to to fall, but what they couldn't possibly expect is for a giant arm to reach out of the darkness and pull one of them down. Have the party figured out that there's a shapeshifter that's infiltrated the rebel meeting and is killing their allies? They suspect suspicion and lies but what they don't expect is for the rebel base to suddenly be on FIRE forcing them to run.

My expert advice is to lightly tease this second threat LONG before you introduce the initial scare. Your players will think you're a genius for doing what amounts to a little extra work, and curse themselves for not paying more attention.

Restraint: Less is more when it comes to scares, as if you do this trick too often your players are going to be inured to it. Try to do it maybe once an adventure, or dungeon level. Scares hit so much harder when the party isn't expecting them. If you're specifically playing in a "horror" game, it's a good idea to introduce a few false scares, or make multiple encounters part of the same bait and switch scare tactic: If we're going into the filthy gross sewer with mould and rot and rats and the like, you'll get more punch if the final challenge isn't corruption based, but is instead some new threat that we could have never prepared for.

Art

338 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DM Tip: Better Loot

Treasure is ubiquitous in D&D, it’s presumed to be one of the default motivations, if not the only motivation behind many adventures, despite the fact that very little thought has been put into the systems by which the DM generates the treasure and the party plays around with it. After nearly two decades of being a DM I can’t count the number of times I’ve made a treasure horde and handed it out to the players while feeling as if the fun game we had been playing had suddenly been put on pause.

It took me a while to realize that this was because unlike combat ( the favourite child among d&d’s many subsystems) very little attention had been made to making loot feel good at any stage of the process whether it was down to the mechanics or even the presentation.

While below the cut I’m going to get into systems about easier ways to generate treasure, rebalanced magic item prices, and how to get your players in on the fun, for now I want to focus on this element of presentation when it comes to handing out loot.

Here’s some of my findings, in no particular order:

Just like combat has “ Roll initiative” and “how do you want to do this?”, handing out loot should have codified phrases to indicate that the party is entering into a specific period of game time. It’s a ritual that will not only get them excited but have them in the right kind of headspace required for absorbing new information. The phrases I’ve been using are “ You spill out your plunder across the table/dungeon floor and there you find_____” and “With that sorted, you pack away your spoils, and return to the adventure at hand”

I completely ignore art items/gems, they’re a neat idea for flavor but they slow things down at every turn ( coming up with them during loot generations, players recording them) and are almost always junked for gp at the first possible opportunity. The exception to this is valuable trade goods/collectors items, which I mention being worth X gp in value but worth MORE if the party can find an associated merchant ( as a questhook)

GP comes first, followed by the names of the items and a brief as possible physical description. Players can ask questions generally on what items do but either have to call dibs then or divy them up on their own time. Listening to the dm dispassionately read out the stats of an item is boring as hell, only eclipsed by the dm describing the indepth LOOK of various items and then asking the party to roll checks to identify/figure out of the items work. Speed in divvying loot keeps the momentum of the game going and you want to tap into the “OOOH, SHINY” impulse of your players before their eyes glaze over.

I HIGHLY suggest keeping a party doc with the stats of all your items copy/pasted into it. Divide the doc up by characters/in the cart, so your party can always remember where shit was. Ask one organized player to be the one to keep track of the party doc and share it with the others. Call them “quartermaster” they’ll love that shit.

Unless the item in question needs to be used immediately “ It’ll be in the party doc” is your answer when they ask for stats. Update the partydoc after session so your group can have the whole week to look at it and get used to things between sessions. Gearing up with new loot is just as much homework as leveling up a character, and is best done away from the table.

After you’re done checking out the treasure generation rules below, also be sure to check out my systems on handling shopping trips, making identifying items more interesting, and managing party wealth. I’m sure you’ll find something there that can help improve your game.

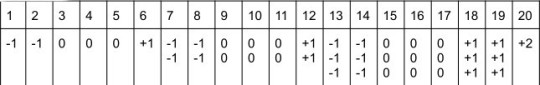

The magic item chart to rule them all

Figuring out a better way to generate magic items was actually pretty simple once I had all the pieces in place, though it took me a many attempts to realize what I actually wanted in such a system:

It had to be simple and time saving, requiring the least amount of math/chart references as possible

it had to be relevant at every level accommodating to 3rd party material

d&d already divides items and adventuring parties into tiers, and the game already allows lower level parties the chance at finding items that outstrip their tier.

Absolutely no effort should be spent generating items wroth random amounts of gp when players are going to instantly sell them.

Which led me to this thing of elegance:

To generate a hoard of items, roll a single set of dice (1d4, 1d6, 1d8, 2d10, 1d12, 1d20) and compare the numbers rolled against the chart above. Every 0 represents an item relevant to the party’s adventuring tier ( so a lvl 1-5 group would get common, lvl 6-10 group would get uncommon and so on). +1s represent an item of a grade above, -1s represent an item of a grade below. I had to invent a tier below common, but d&d already has rules for “trinkets” as fun but mechanically useless items that were easy to adapt.

After I’ve got a string of -1s, 0s, and +1s, it’s only a matter of comparing them against whatever list/books I’m using to supply items. For sake of ease, I’ve got multiple google docs where I’ve sorted my collection of 3rd party and homebrew items by rarity and theme, but if you don’t hoard material like I do you don’t have to worry about that.

New Magic Item Prices

having several thousand GP worth of wiggleroom for high level items helps no one, so instead we’re going with a base 5 system that’ll guide us through the rest of this doc. These prices are meant as an absolute baseline for things like crafting and haggling down to, as well as determining the value of non-magical rewards later on.

Trinket: 10 , Common: 50 , Uncommon: 250 Rare: 725 , Very Rare: 3625 , Legendary: 18,125

Having a concrete price also lets you use my chart to generate raw GP in coinage: too many items cluttering up your list? run out of ideas? convert the leftover item slots into thier price in GP and worry no more.

Other Uses for the Chart:

If you’re the type to run magic item shops ( and you should), using a set of dice to generate treasure is a great way to pick out the inventory. Most shops are going to be at common rarity, but for major shops the party is going to return to over several levels, I do a new inventory drop every 5 levels.

Since Overthinking d&d is my passion, I was caught up in weighing the value of treasure that was scattered throughout the dungeon vs treasure that was all in one place. The former encouraged the party to explore (which is the entire reason for going into a dungeon) but risked the party missing out on important rewards if they didn’t figure out a clue or feel like fighting a particular beast. The latter felt like a proper reward for overcoming a gauntlet of challenges, but encouraged players to race to the end. The answer was to do both, One hoard at the end of the dungeon, one scattered around in nooks and crannies for the party to discover on their own. That meant that a party could count on almost doubling their plunder if they explored the content I’d made for them... which is exactly where I want them to be.

Frequently my parties will do a bit of unexpected looting I haven’t planned for: They’ll pick through the ruins of a destroyed town looking for salvage, harvest alchemical components from a garden of feywild flora I’ve only intended as set decoration, or load up a cart with the contents of a bandit armoury and hit the market with it. I want to reward players for taking the initiative, but I always feel like raw gold is too flat a prize and I don’t like making up stuff on the spot. My system offers a solution: every time they do that they get a stack of loot ( graded common to very rare, based on who or what it is they’re looting). When they hit the market, they can cash in any number of loot stacks for the roll of 1 dice, scaling up. If they hit 7, they get to roll the full array and get themselves a loot drop. This is always done in the aftermath of a session, so that I have time to tell them what they’ve won. ( 5 stacks of loot is worth 1 of the next grade up and visa versa). I similarly let my players attach a wishlist to this loot drop ( vague things like “ healing potions” or “ I’d like a new spell focus” to guide my search through my item lists.

#the loot overhaul#dm tips#dnd#treasure#tableskills#dungeons and dragons#d&d#5e#dm advice#dm tip#dm tools#writing advice#homebrew#homebrew mechanic#shopping#loot#magic item

597 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tableskills: The Proactive DM Voice

One of the most fundamental lesions I learned over the course of becoming a great DM was that it was my job to push the story forward, not my players. When I was younger I was terrified of taking any agency upon myself for fear of railroading my group, thinking that my job was merely to read out prepared text and design a playground for my players to explore as they saw fit. Needless to say, no matter how much planning i did or how big I made my campaign world it never made my party any more energized, instead bleeding out their attention until they became listless and the group/campaign dissolved.

Once I made the change to DM driven play, things changed almost instantly. My once distracted players became excited collaborators, looking to steer the runaway engine that was my narrative. Where as before they were directionless, having infinite shallow options, they were now focused on the road ahead of them, trying to dodge upcoming hurdles while reacting to the unexpected ones.

This change took some getting used to, but became most evident in how I narrated my games, cutting down on extraneous calls for rolls, chaining together scenes until a big finale at the end of the session, using my infinite power as narrator to push receptive players into interesting situations that progressed both the story and their character arc. Over time I began to think of these changes and a bunch of others as “proactive DM voice”, a skill that I think players and dungeonmaters alike could benefit from learning.

Lets look at an example, lifted from one of the very first modules I ever ran: The party stands at the edge of a tremendously large fissure, and has to lower themselves a hundred or more feet down to a ledge where they’ll be ambushed by direrats. You could run this in a rules literal sense: reading out the prepared text then waiting for the party to come up with a solution, likely dallying as they ask questions. Have them make athletics checks to descend the ropes, risk the possibility of one of them dying before the adventure ever begins. Then you do it two or three more times as they leapfrog down the side of the canyon, wasting what was perhaps half an hour of session time before you even got to any of the fun stuff.

Or you could get proactive about it:

Securing your ropes as best you can, you belay over the side of the fissure, descending down in a measured, careful pace aiming for the most stable looking outcrop of rock, still a hundred or so feet above the canyon’s base. A few minutes and about two thirds of the way through your decent [least athletic PC] looks like they’re struggling, their hands are coated in sweat and they can feel unfamiliar muscles burning in complaint. I need [PC] to make me an athletics check

Rather than waiting for the players and the dice to make a story for me, I took the extra step in my prep time to think of something interesting that might happen while they’re venturing through this section of the map. I specifically designed things so that happenstance wouldn’t kill off one of my heroes, but they might end up damaged and in a perilous situation should the fates not favour them that particular moment.

Likewise, this planning has let me prepare a number of different angles that I could use to prepare the next scene: with an injured player ambushed by multiple rats while their allies dangle a few rounds away or with the party saving their friend and descending together, too much of a threat for the rats to tackle all at once, leading them to stalk the party through future encounters.

This is already getting a bit long, but for those interested in more ways you can adopt a proactive DM voice, I’ll give more examples under the cut

A lot of people talk about “the Mercer effect” new people getting into d&d and begin disappointed that the group they’re playing with aren't like critical role. A lot of creators have talked about how to combat the Mercer effect, but regardless of props or budget, I think the greatest difference between your average d&d table and what you see on shows like Critical role, Adventure Zone, or Dimension 20 is the fact that in those streamed games EVERYONE at the table is using a proactive voice, where as it seems to be a skill that most players and dms never pick up on.

Think about it this way, nearly every streaming show is made up of professional entertainers: Voice actors, comedians, people who understand that time is a finite resource and a lack of momentum can kill their performance. That’s why listening to them play is such a treat, everything they say or do is designed to cut down on dithering and give the greatest comedic or dramatic punch in the shortest amount of time.

You start doing the same when you start using a proactive voice at your table, leaving all the unfun number crunching and arbitrary restrictions aside in favour of telling jokes or modulating the dramatic tension, a habit that your party will pick up over time as you maintain it, which will lead to snappier play and more getting done in a single session.

Momentum is key: you always want to be pressing forward towards the meat of your session, towards the next fun npc or dramatic setpiece, and as such you need to give your party the idea that they’re rolling towards a destination. The trick is that after a few plot relevant bits of setup, this destination is almost always a bad one, and if the party doesn’t act on the opportunities you’ve given them, they’re they’re going to end up hurdling towards disaster.

After your party has had their fun ask “ Is there anything you want to do before____?” rather than “ is there anything you want to do?” This gives your party a sense of urgency and forces them to act on their priorities, rather than waiting for them to decide and letting all the tension bleed out.

Be Obvious: you want players to know who and what within a scene is a means for gaining forward narrative progress, so whenever you narrate, be sure to add a liberal dose of scene hooks in with your background description.

The reason that players dither is because they’re not sure what the expectations for a scene are or what they can do: Try to end every one of your descriptions with a prompt for action from your players, restating the problem they’re facing, a few options that they might use to solve it, a reminder of what might happen if they fail. This also helps get past some players who’ve been trained by anxiety bad dms to expect a trap everywhere.

When in doubt, cut it out: unless you have interesting material prepared for a scene, it’s a good idea to skip over a length of time and get to the next bit of content. There’s no reason to detail a party’s night of sleep in the inn after the first night, nor days of travel that aren't particularly dangerous or exceptional. Move them forward unless you feel like one of your players wants to use their downtime as a backdrop for RP

Just let them do it: One of the quickest ways to speed up your game and get things flowing is to cut out extraneous rolls: if your party figures out who the mystery killer is or identifies the type of monster the villagers only saw a hint of, don’t have them roll to see if their characters figured it out. The same goes for solving a puzzle, or correctly suspecting something might be trapped. Instead give them a gold star for being clever little goblins and move on, rather than locking crucial plot development behind a dc. I take any excuse I can to GIVE my party information, relating it to their character backstory or their time spent in a certain region. Not only does it make things faster, it makes them more immersed.

They need to be allowed to mess up: When you cut down on extranious rolls, it means those left behind are important, and need to have consequences. The same goes for the party’s decisions, which need to have real and lasting consequences (good or bad). The first time the party realizes they dropped a plot hook and someone they knew suffered for it, they’ll suddenly understand their responsibility to the world they’re adventuring in and the story they’re a part of.

Give your party regular breaks: While it’s important to maintain a steady momentum, sometimes it’s a good idea to let your party wander a bit, especially if you’re about to head into a longer section of action like a dungeon delve or a mystery. Give them an idea when this time will end (a crowning event at a festival, the king’s courier will get back to them in about three days, bad weather rolling in) and then ask if there’s a special way they’d like to spend their time. This designated space to goof off or go on tangents is actually the best way to get stuff out of your more RP shy players, as they’re often self conscious about taking the spotlight away from others.

I hope this gives you what you need to start making the switch over to proactive Dm voice, but if you want more inspiration pay attention to some liveplay artists, especially those who know they’ve got a limited amount of time on camera to get things done. Imitation is not only the sincerest form of flattery, it’s also one of the best ways to improve your skills.

#tableskills#dm tips#DM advice#DM tools#dm toolbox#narration#voice acting#critical role#dimension 20#taz#Dungeons and Dragons#dnd#dm starterpack

838 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DM Tip: Being a better Storyteller

I talk a lot on this blog about constructing better stories, but I frequently forget to talk about what I call “Tableskills”, those parts of the DM’s craft that are less about formulating plots and laying out narratives than they are relating those narratives to the people around the table. The thing is, teaching tableskills is a lot harder than just suggesting ideas about stories that could be told, as every DM or prospective DM has their own particular type of storytelling that they’ll grow into as they master the art. As such, there’s no hard and fast rubric I can pass down, only the things that have improved my own performances over time.

The basics: The DM Narrator Loop

I’ve been playing d&d for well over two decades now, and I’ve never heard the DM’s art summed up any better than this video by VOX: Describe, Decide, Roll.

You as the DM Describe what situation the party is in and ask them what do they do next ( in a very leading tone, pulling them forward or offering them direct choices)

The players Decide among themselves what they’re going to do, with clarifying input as needed.

If anything needs to be decided by dice, you Roll and figure out the outcome, then you snap right back to the descritption phase.

Keep doing this and your party will be guided along your storiy at a steady clip while having a lot of fun. Keep rolling to when it’s really important, and you’ll be doing just fine.

All Killer No Filler

The most basic trick I’ve learned for tabletop storytelling is asking yourself “ what’s the most interesting thing that could happen this session “ and then telling a story abouthow the party gets from where they are to where that interesting thing happens. Sometimes that interesting thing kicks down their door and forces them to react, other times it doesn’t quite happen on time, and you need to elude to the fact that it’s about to happen next time they play. Sometimes your players will take the initiative upon themselves to make interesting things happen, ranging from deep roleplay moments to taking an unexpected narrative turn and throwing all your plotting out the window. Learn to love when this happens, but don’t rely on it. Players should be given the spotlight when they stand up and take it, but that doesn’t mean you should shove them on stage before they’re ready.

Because you’re running a live session and thus have limited “screen time” in which your interesting thing might happen, you should focus on scenes that push the party forward, building narrative momentum while offering the party a chance to break off and do their own thing. “Does anyone want to do anything before we X” and variations of it is your best ally here, as including a pending time limit spurs the party to act before circumstances change while also giving them a direction to fall back on when they don’t want to make a decision. This is where radically open world/hands off DMs fail, because the players showed up expecting to be part if a story rather than entirety making their own fun while a friend if theirs silently chides them for not pretending to be an elf good enough. TLDR: Always be moving towards something interesting happening inside the session, but never be afraid to detour when it looks like your party is going to do your job for you.

Economy of Information

I often have a problem with expressing my ideas to other people because I either trip over myself trying to get out all the data required at once, or I leave people hanging because I presume they can infer what comes next. Naturally this is a trait I’ve had to train out of myself when I’m being a dungeonmaster and I did that by studying a bit of cinematography. Movies are not subtle about how they want you to feel at any given moment: If the audience is supposed to be on edge, the surroundings are eerie and the music is discordant, if you’re supposed to like a character they'll either be reminiscent of a wholesome archetype or the camera will deliberately show them doing something nice. Don’t sweat the details when you’re describing a scene or doing background world building, paint in wide strokes and then fill in the details as necessary. Likewise, don’t let your scenes dawdle, bake in a reason why the scene is going to end before too long and use that as a ticking clock to spur your party into action.

When in doubt, be a Cartoon

As gritty as some people like their tabletop roleplaying, at the end of the day it’s just a big game of pretend, and in my experience the best way to tap into my player’s emotional base is to engage the sense of play they’ve been fostering since they were kids. Unsure how to describe something? Picture how it’d look in a disney movie and your word-picture will come across clearer in your player’s minds. Not yet confident enough to RP a nuanced NPC? Overact like a caricature of who you’re pretending to be, and you’ll suddenly have a lot more wiggle room to play with. However gritty some people profess to like their tabletop gaming it’s all a big game of pretend in the end, and the way you engage your party’s emotional core is by appealing to that sense of play they’ve been holding on to since they were a kid.

Follow the Fun

It took me a while to realize that “fun” was like oil in the engine of any d&d game, and that the primary job of the storyteller was ensuring that it was properly circulating throughout the session. Not enough fun? whole thing grinds to a halt and playing feels like pulling teeth. Too many sessions like that and a campaign falls apart. It takes a bit of practice as a DM, but try to be attentive for when fun “bleeds out” of your campaign. Players beating their head against a puzzle? Skip it, try a different sort of puzzle next time. Someone doesn't’ enjoy shopping trips? give em something to do while the rest of the party is perusing. Combat bogging everyone down? Experiment with techniques to make it snappier. Keep up this mindset and your games will be pumping along like a precision engineered machine.

Fail Faster

I’ve listened to this video so many times I could probably repeat it as liturgy. Just like any performance art, the main metric for advancement is realizing where you’re doing poorly and then figuring out ways to improve upon them. Sooner you figure out what you’re doing on and why, the sooner you can try out ways to fix them, and the sooner you can find things that works. Take on an experimental attitude towards your own works, if something is hard: find a way around it that works for you.

#prompt postage#DM advice#dnd#dungeons and dragons#adventure#5e homebrew#homebrew adventure#dm tips#dm tools#dungeon master tips#tableskills#storytelling#dm starterpack

702 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Daily Adventure Prompts Masterpost

After several years of running this blog, it’s become more and more evident that I need some central reference where people can access all my different DM advice posts, important tags, and ongoing series. Sharing my ideas with people and helping to improve the art and craft of being a dungeonmaster was always the point of DAP after all, and its of no help to anyone if the answers to important questions are buried under a hundred or more pages of my rambling.

To that end, I present this post as an ever expanding catalogue of my thoughts. Something that you can page through at your leisure in hopes some of my hardwon lessons will be of use to you.

DM Advice: The go-to tag for all my rambling on how to improve your d&d game, with some highlights presented here,

My Process

Getting Organized

Basics of Campaign writing

Railroading & Rollercoasters

The “more than you can chew” universal d&d story structure

Ghosts on the Horizon: not getting bogged down with overplanning

Mapmaking 101

Writer’s Block

Better Random Encounters

Better Loredumps and Exposition

Writing Adventures to Make your party care about your world

Series of Interest

The DM Starterpack: Focused on first timers or those who want to re-learn d&d from the ground up this series of posts is intended to give you an idea how to come up with a campaign concept, write a first adventure, run a session zero, and slowly pivot into running a larger campaign.

Tableskills: While a lot of my work focuses on how you can write better stories, these posts talk about being a better storyteller focusing in on the performance art of DMing.

Mechanics: On the flipside, sometimes you need to put on your game designer hat and focus in on ways to make the underlying engine of the game run more smoothly to better facilitate fun and storytelling.

How to Run...: there are certain types of adventure that need more thought put into them then the average monsterhunt or dungeon delve, and so I wrote a series of articles to not only help you write/design them but to pull them off at your table.

Wilderness Exploration

Heists

Naval Combat

Infiltrating a fancy party

Mystery

Airship Adventures

Political Intrigue

Mythology style epic labours

The Loot Overhaul: A series of posts where I focus in on different aspects of d&d’s treasure and item

An overhaul to player wealth & The Economy

Better Loot & Treasure Hoard generation

A case for magic item shops & Item focused treasure hauls

Shopping trips & Group Inventory Management

Making Identifying & Attuning to Items interesting

Crafting Overhaul pt 1: Weapons & Armour

Crafting Overhaul pt 2: Magic & Consumables

Monsters Reimagined: My ongoing delve into d&d’s bad monster lore and how it can be improved. Sometimes it’s because a cool monster is just underwritten, sometimes its because how they’re used in the narrative just doesn’t make sense, sometimes its because there’s decades or even centuries old pro-genocide talking points that we need to unpack.

Footnotes on Foes: For those topics that don’t warrant a full “monsters reimagined” but I still want to give my take on. Fun stuff in there, especially with lesser known monsters that could use a revamp.

Heavy Topics: Where I deepdrive on the nuance of particular topics, ranging from uncomfortable touchstones in history that are important to my writing to sensitive subjects that you’ll want to discuss with others around your table.

Bad Opinions: Sometimes a take so awful lands in my inbox that I need to hold it up infront of my audience and perform a vivisection. Its part media study, part bloodsport.

Dungeon Design: An attempt to do what the creators of the game have put off for decades (despite being half of the title) and actually provide a coherent framework for step by step dungeon design. After nearly twenty years of banging my head against a wall, it finally seems to have worked.

Planescape: Where I try to add cool new (or revamped) destinations to the tapestry of d&d’s multiverse.

Special mention to “Why I don’t use the Great Wheel Cosmology” as it underscores a lot of my overall problems with d&d’s cosmic lore and its weird moralistic claims.

Deities: A collection of new/overhauled gods focusing on making them represent ideals that people would actually believe in as an embodiment of ideals and narrative themes.

How to use the divine in your game: a story first view of how to use faith, religion, and gods in your campaigns aiming for things more subtle and thematic.

Outer Gods: For when you want to get lovecraftian

Religion is the tag I use to talk about the concept of both faith as a theme in writing, as well as how the organized religion serves as a worldbuilding tool

Adventures by Type: not a comprehensive list

Press Start: Opening adventures for those who want a solid start for future campaigns or adventures

Campaigns: For those who’d like a larger story framework to play with

Adventure Compendium: If you’d like a lot of ideas on the same theme

Dungeon: Need I say More?

Monsterhunt: Facing off against a powerful enemy that has some tricks

Villain: In both Quantity and Quality

Player Home: Every party needs a place to rest their head

Ally: They’re here to help, usually

Patron: Benefactors of the shady and non shady verity

Mystery: Put your Sleuthing Hat on

Thief: Time to steal something

Faction: Larger groups the party can join

Adventures by Environment

Lowland

Swamp

Field

Desert

Wasteland

Highland

Cave

Mountain

Forest

Seaside

Ruin

Settlement

Village

Town

City

373 notes

·

View notes

Note

My youngest sibling has a couple overlapping friend groups who have tried to play a few D&D games over Discord, but they've all given up as in-character arguments became out-of-character, or elements of a character backstory or adventure have triggered negative responses from one or more players, and it eventually broke up each game. I love D&D and have wanted to play with my youngest sibling for a while, and have offered several times to DM a few sessions for them and their friends, but they're hesitant as their experiences have been colored by these incidents. So I wanna ask: what advice do you have for keeping tempers cool, keeping IC interactions from harming OOC interactions, and preventing story or character decisions from becoming uncomfortable, offensive, or triggering?

DM Tip: Can't we All just Get Along?

I think there's two elements at play here, the first is whether these people should even be playing as a group to begin with, and the second is a matter of table moderation.

First let's address the former: It's the sad truth of our hobby that not everyone can play together, personalities clash, expectations differ, and sometimes the vibe just isn't there. There's no shame in that, and part of coming into your own as both a player and a DM is realizing what sort of group you'd like to have and taking steps to find one. This is one of the many reasons I don't play in store games, because for me the true magic of the game is only possible when I have the right alchemical balance of players around my table. For me, No D&D is better than bad D&D, so I am exceptionally choosy with what games I do end up playing in and will drop a game the second I determine it isn't for me. I encourage you all to have this exact same mentality, as it will lead to a higher degree of enjoyment to be had by all.

Second, lets talk about fights at the table: It has been a long, long time since I've had anything resembling open player conflict while I was running a game, and I credit that to a decision I made well over a decade ago that I wasn't going to be the sort of DM you heard d&d horror stories about. Instead, I dedicated myself to ensuring that the people around my table were going to have the best time possible, which is the only real metric of success a DM can really have.

To do this, you need to be utterly open and utterly heartless when you sense conflict arising at your table. Someone doing something that makes another player uncomfortable? Quash it, right then and there, and tell everyone why you did it. Person getting overly heated or demanding and bringing everyone down? Call a time out, get some snacks, and talk it through. Player have their feelings hurt? Pause, check in with them emotionally, assure them that it's alright to step away, then continue on.

Like any relationship, a d&d group only works when the participants are invested in eachother's wellbeing, and take that into consideration when determining their own actions. People who don't care about how they affect others are problem players, and problem players need to either be corrected or ejected for the health of the group.

Here's some things you can do at your table to avoid conflict:

Use Safety tools: A lot of people have said it a lot more eloquently than me, but there are lots of resources available to help you and your group manage the stresses that might come up during play.

Writer's room it: when describing what d&d is, I literally always start with "It's a collaborative storytelling game", despite the fact that most people forget about the collaborative part. The campaign isn't just the DM's story to tell, and the players should be given a chance to stretch their authorial power when it comes to deciding what happens. This goes double for moments of conflict, when one of the players feels the actions of another might ruin the story for them. When these sorts of things happen, zoom out, talk to your players about what's going on and what their take on current events is. This change in perspective will often let a player go from feeling that they were personally wronged, to seeing this setback as something they can use to further the story. Do not hesitate to use bribery saying: " if you're ok with your character taking a loss here, something good will happen to you later on." This advice obviously doesn't apply to anything that might violate a player's personal boundaries, which you should simply not let happen.

Say No: D&D, when done right can be one of the most intimate and cathartic experiences imaginable, to the point where it's recognized as a therapeutic tool. On a more casual level, people are there to enjoy themselves and in both instances Players shouldn't have to contend with assholes who get a kick out of ruining their fun. You as the DM are invested with the authority to let things happen/not happen, from whether or not you actually play to whether an action your players decide to take is canonical to how the story proceeds. Don't indulge the asshole, if someone does something that makes people uncomfortable, don't narrate them doing it up until one of the players gets triggered.

Encourage them to be open: everyone at the table needs to be fully up front with how they're feeling, and if one person's not enjoying themselves, you should stop. Players likewise need to be open about their own feelings so as to not get them confused with how the characters might be feeling. It's fine if your characters argue, but only if the players signal that they're cool for that level of antagonism happening in game.

Art

#prompt postage#tabletop inspiration#table skills#dm toolbox#dm tip#dm tools#dm advice#dm tips#dm starterpack#tableskills

212 notes

·

View notes