#sylvia plath juvenilia

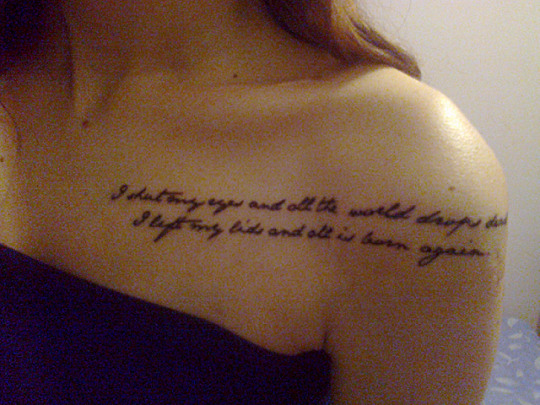

Photo

Via @annenoodle on Twitter

...

MAD GIRL’S LOVE SONG

A Villanelle

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my lids and all is born again.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

The stars go waltzing out in blue and red,

And arbitrary blackness gallops in:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I dreamed that you bewitched me into bed

And sung me moon-struck, kissed me quite insane.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

God topples from the sky, hell’s fires fade:

Exit seraphim and Satan’s men:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I fancied you’d return the way you said,

But I grow old and I forget your name.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

I should have loved a thunderbird instead;

At least when spring comes they roar back again.

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

–Sylvia Plath, written 1954, in: The Collected Poems, 1981

#sylvia plath#Mad Girl's Love Song#sylvia plath tattoos#mad girl's love song tattoos#sylviaplath#arm tattoo#tattoos#sylvia plath quotes#Sylvia Plath poetry#The Collected Poems#sylvia plath juvenilia#literary tattoos#poem tattoos

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

my extravagant heart blows up again

Sylvia Plath, Collected Poems: Juvenilia; from ‘Circus in Three Rings’

350 notes

·

View notes

Text

_______________________________________________

Book Review

Title: Plath: Poems

Author: Sylvia Plath

Compiler: Diane Wood Middlebrook

Everyman's Library Pocket Poets Series

No. of Pages: 256

ISBN: 9780375404641

Synopsis:

Sylvia Plath’s tragically abbreviated career as a poet began with work that was, in the words of one of her teachers, Robert Lowell, “formidably expert.” It ended with a group of poems published after her suicide in 1963 which are, in the nakedness of their confessions, in their black humor, in their ferocious honesty about what people do to one another and to themselves, among the most harrowing lyrics in the English language—poems in which a magnificent, exquisitely disciplined literary gift has been brought to bear upon the unbearable. In these transfiguring poems, Plath managed the rarest of feats: she changed the direction and orientation of an art form.

_______________________________________________

What did I think of the book?

Plath: Poems by Sylvia Plath

My rating: ⭐⭐ 2 of 5 stars

This is the first time I’ve read works from Sylvia Plath, I’d never even heard of her name before finding this book in the bookstore. Her poetry was complex and rhythmic, and explored many different subjects. They had me thinking hard at times about what was happening in her life, and what was going through her mind when she wrote them.

I enjoyed the first few sections of poems from Juvenilia to 1958 compared to the rest of the book. Many of the poems after 1958 were really difficult for me to grasp and understand, and became harder and harder as the pages went on; it almost had me giving up reading this one. By the section of 1963, the poems changed a bit in style, and they became more enjoyable to read again.

At the back of the book, there is a section of notes on some of the poems, which I’m very grateful for as these helped my understanding hugely. However, I wish these were at the front of the book so I could have read them first before diving into this poetry collection.

Favorite poem/s:

Spider, page 38-39

Fiesta Melons, page 37

Two Lovers and a Beachcomber by the Real Sea, page 21-22

Epitaph in Three Parts, page 23-24

Mussel Hunter at Rock Harbor, page 65-68

Words, page 234

What drew me to this book?

It was the smallest poetry book on the shelf with just PLATH across the cover. It intrigued me.

Stars:

2/5 because some of the poems were a miss for me, and many I couldn’t understand. Unfortunately, one of the pages was misprinted in my copy, so some of the longer lines were cut off.

View all my reviews

#booklr#poetblr#book review#poetry review#sylvia plath#poetry#poetry collection#poetry and poems#book blog#books#bookish#bookworm#books and reading#book photography

0 notes

Text

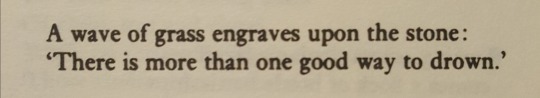

Sylvia Plath, from The Collected Poems of Sylvia Plath; "Epitaph in Three Parts"

368 notes

·

View notes

Text

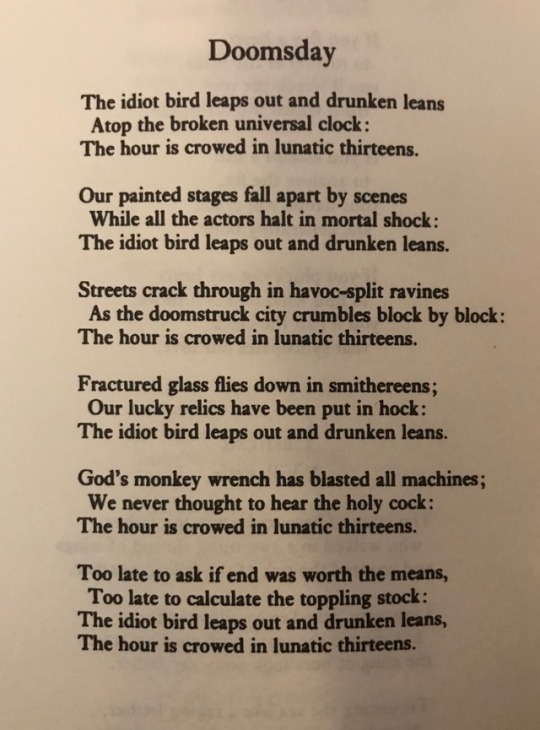

doomsday - sylvia plath

#juvenilia is valid i want to see how making the poems WORKS#WHYS THIS SHAKESPEARE’S JC HOURS#poetry#sylvia plath#beeps

26 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Time is a great machine of iron bars

That drains eternally the milk of stars.

Sylvia Plath, The Complete Poems: Juvenilia

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Lovers and a Beachcomber by the Real Sea

Cold and final, the imagination

Shuts down its fabled summer house;

Blue views are boarded up; our sweet vacation

Dwindles in the hour-glass.

Thoughts that found a maze of mermaid hair

Tangling in the tide's green fall

Now fold their wings like bats and disappear

Into the attic of the skull.

We are not what we might be; what we are

Outlaws all extrapolation

Beyond the interval of now and here:

White whales are gone with the white ocean.

A lone beachcomber squats among the wrack

Of kaleidoscope shells

Probing fractured Venus with a stick

Under a tent of taunting gulls.

No sea-change decks the sunken shank of bone

That chucks in backtrack of the wave;

Though the mind like an oyster labors on and on,

A grain of sand is all we have.

Water will run by; the actual sun

Will scrupulously rise and set;

No little man lives in the exacting moon

And that is that, is that, is that.

–The Collected Poems (Juvenilia 1952-1956), 1981

***

Because 12 more hours and I’m off on vacation! :)

#sylvia plath#sylviaplath#two lovers and a beachcomber by the real sea#The Collected Poems#sylvia plath poems#poetry#vacation#juvenilia

37 notes

·

View notes

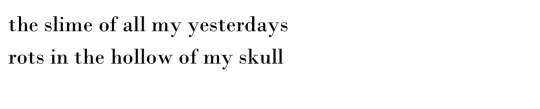

Quote

the slime of all my yesterdays

rots in the hollow of my skull

Sylvia Plath, from The Collected Poems, Juvenilia, “April 18”

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mad Girl’s Love Song

"I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my lids and all is born again.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

The stars go waltzing out in blue and red,

And arbitrary blackness gallops in:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I dreamed that you bewitched me into bed

And sung me moon-struck, kissed me quite insane.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

God topples from the sky, hell's fires fade:

Exit seraphim and Satan's men:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I fancied you'd return the way you said,

But I grow old and I forget your name.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

I should have loved a thunderbird instead;

At least when spring comes they roar back again.

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)"

- Sylvia Plath, Poesía completa (Juvenilia). Ed. Bartleby, 2009

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Candice L. Wuehle, “And I a smiling woman:” Sylvia Plath’s Unheimlich Domesticity, 11 Plath Profiles 1 (2019)

Doppelgängers, living dolls, monstered speakers, and alien landscapes populate the corpus of Sylvia Plath’s writing from her juvenilia to her posthumously published Ariel poems.1 It is apparent from the poet’s undergraduate thesis, “The Magic Mirror: A Study of the Double in Two of Dostoyevsky’s Novels,” that Plath was absorbed by the psychoanalytic underpinnings from which the concept of the uncanny was birthed.2 In her thesis, Plath argues that Dostoyevsky’s characters have “attempted to exclude some vital part of their personalities in hopes of recovering their integrity. This simple solution, however, is a false one, for the repressed characteristics return to haunt them in the form of their Doubles” (Coyne). Plath’s articulation of “repressed characteristics” is certainly informed by Sigmund Freud’s 1919 essay, “The Uncanny,” in which Freud analyzes E.T.A. Hoffman’s short story “The Sandman” in order, ultimately, to argue that a “return of the repressed” is at the root of uncanny affects.’

Significantly, the Germanic origin of the adjective “uncanny” (“unheimlich”) springs forth from the space of the domestic, ergo, the domain of the feminine. Likewise, Plath’s use of uncanny affects functions as a tool the poet frequently employs to interrogate cultural constructs regarding “femininity,” particularly in relation to the domestic sphere, motherhood, and objectification of the female body. While Plath was already a well-known figure throughout the English literary scene due to appearances on the BBC and in various publications, Frances McCullough argues that the poet reached cross-continental renown in the years between the posthumous publication of Ariel in 1964 and American publication of The Bell Jar in 1971 due to the influence of the Woman’s Movement, which politicized the contents of Plath’s work written in an era that was “pre-drugs, pre-Pill, pre- Women’s studies” (9). Plath biographers Anne Stevenson and Linda Wagner- Martin agree with McCullough’s reading; Stevenson claims Plath as “a heroine and martyr of the Woman’s Movement” (Two Views of Plath 1994) while Wagner-Martin states, “Like Friedan’s 1963 The Feminine Mystique” Plath’s Ariel and The Bell Jar were “both a harbinger and an early voice of the Woman’s Movement” (Two Views of Plath 1995). However, in spite of Plath’s unique significance to first wave feminists, little attention to the manner in which the poet persistently frames issues central to the Women’s Movement as uncanny have been considered.3 Several scholars, such as Kelly Marie Coyne, in her recent article, “The Magic Mirror”: Uncanny Suicides, from Sylvia Plath to Chantal Ackerman and Judith Kroll in her 1978 biography, have examined Plath’s work through the lens of the uncanny. Indeed, these critics also take their point of departure from Plath’s undergraduate thesis, however, they do not expand their analysis of her work beyond the concept of the “double” or “döppelganger” to consider the many other aspects of the Freudian uncanny present in her poetry. Coyne offers an interesting analysis of the double from a queer studies perspective, ultimately arguing that, “Plath—in doubling on both the extradiegetic and intradiegetic levels of [her] work—propose[s] a queer liminal space that siphons and ultimately expels repressed uncanny desire, allowing for both self-sustainability and personal integrity” (1). My own reading of the Plathian uncanny (specifically in relation to the döppelganger) orients itself first from Luce Irigarary’s conceptualization of the döppelganger: “Within herself,” Irigaray argues, “she is already two—but not divisible into ones” because female desire “does not speak the same” singular “language as male desire.” Rather, it is “diversified” and “multiple” (100). Like Irigarary, my reading insists that to express female desire is always to speak the language of the uncanny, therefore, not even a “queer liminal space” possesses the ability to “expel uncanny desire”; rather, to speak of female desire and the female experience is to always be speaking in Plath’s depictions of motherhood, domestic labor, and media representations of femininity as uncanny, monstrous, alien, and otherwise “creepy,” therefore, provides crucial insight into both the poetics of Sylvia Plath as well as the manner in which Plath’s use of the uncanny comes to serve as a synecdoche of a much larger cultural discourse.

Via an etymological investigation regarding that which constitutes the homelike (“Heimlich”) as “belonging to the house, not strange, familiar, tame, intimate, comfortable, homely, etc.” (2), Freud locates the home at the center of the unfamiliar, stating, “The word Heimlich exhibits one which is identical with its opposite, unheimlich. What is Heimlich thus comes to be unheimlich” (3). The Freudian uncanny is thus the familiar, which has been estranged through repeated repression. What I have termed “the Plathian uncanny” manifests itself as a return to the (quite actual) home, whose constraints Plath’s speakers wish to outright reject, but are compelled by cultural forces, legal restraints, and/or historic precedent, to repress. In “The Applicant,” for example, Plath presents a furious satire of a job interview:

First, are you our type of person?

Do you wear

A glass eye, false teeth or a crutch,

A brace or a hook,

Rubber breasts or a rubber crotch,

Stitches to show something’s missing?... (1-6)

In these lines, Plath presents the gaze of the (male) interviewer as one which views the “ideal” woman (“our type of person”) as incomplete and inherently repressed. This repression generates an uncanny mode (as displayed quite literally by Plath as a body outfitted with artificial parts) that presents the domesticated female body as a site of contested cultural and psychological memory. In “The Big Strip Tease: Female Bodies and Male Power in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath,” Kathleen Margaret Lant emphasizes the extreme power the female body poses in Plath’s poetry, arguing that the poet’s frequent recourse to bodily imagery “... reveal[s] Plath's conviction that undressing has become for her a powerful poetic gesture, and in these poems it is the female speaker who finally disrobes— and here she attempts to appropriate the power of nakedness for herself” (630). Lant further elucidates the connection between power and subjectivity, adding, “Plath does not simply contemplate from the spectator's point of view the horrors and the vigor of the act of undressing; now her female subject dares to make herself naked, and she does so in an attempt to make herself mighty” (630). It is significant, then, that the “mighty” power of uncanny representations in Plath’s late poetry are often generated by transformations and conflations of the speaker’s body with cultural or historical artifacts; in “The Other,” the speaker’s own blood becomes “an effect, a cosmetic” (line 30) while the speaker’s body in “Fever 103o” boldly transitions into “a pure acetylene/ Virgin” (46-47).4 In this way, the body itself becomes an unheimlich vessel which functions to question, contest, and, ultimately, protest normative ideals regarding female subjectivity.

This essay will begin by considering the poetry and prose of Sylvia Plath from a Kristevian perspective in order to illuminate the manner in which Plath confronts and destabilizes the “borders” which confine the domestic space and domesticized body. A close reading of “Lady Lazarus” will examine the way in which Plath constructs a speaker who performs this destabilization by weaponizing the abject via a repetition compulsion which emerges and replays a repressed past. Through further consideration of Lady Lazarus as an uncanny actor who replays a past appropriated from other tragedies (i.e., the Holocaust and the Lazarus Myth), I argue that Plath emphasizes gender differences in the act of remembering in order to perform the uncanny and give voice to the silenced, or, abjected.

Plath’s Unhomelike Home

The Heimlich/unheimlich distinction applies even more pointedly to the “home” of the female body itself. Plath’s female “I”/eye is much like Hoffman’s monstrous “Sandman” who is “without eyes” and instead is possessed of “ghastly, deep, black cavities instead” (90).5 Plath’s speaker both experiences the world as uncanny and is herself an uncanny actor within it. This generates a doubled sense of dis- ease in Plath’s work; because the speaker is often a “living doll” (“The Applicant”); a “little toy wife” (“Amnesiac”); or a collection of assembled, inanimate parts, “My head a moon/ Of Japanese paper” (“Fever 103o”) who witnesses the world as a series of events rife with uncanny atmosphere, the rhetorical situation in which these poems exist is itself disembodied.

Even more troubling, however, is the implication that the female body is never “whole” in terms of consciousness or corporeality. Rather, it functions as a liminal site at which the real and the unreal not only meet, but merge. This merger situates the Plathian body as neither a subject nor an object, but rather as a Kristevian abject who/which "preserves what existed in the archaism of pre-objectal relationship, in the immemorial violence with which a body becomes separated from another body in order to be" (Kristeva 10). A resistance to a patriarchal symbolic order that attempts to position the speaker as only a mother, wife, or sexual object generates much of Plath’s uncanny tension. Liz Yorke also analyzes Plath’s work from the lens of French feminist thought in Impertinent Voices: Subversive Strategies in Contemporary Women’s Poetry to argue that what is shocking in Plath’s work is her readiness to “enter into the fields of semantic danger of her own rage, anguish, and desire” (37). In other words, Plath’s speakers demonstrate symbolic and semantic risk via utterances that serve to 1.) Position the reader as the audience of an uncanny experience in which the concept of “femininity” is made uncanny due to a sense of “intellectual uncertainty” (The Uncanny 7) and disease. This gesture forces the reader to consider female experience as inherently othered. The speaker is thus situated in a liminal space in which she recognizes that which is her own (her Heimlich body in its sexual and maternal capacity) yet is simultaneously made unrecognizable via the utterance that makes the body unrecognizable to itself (a toy, a corpse, a living doll). This gesture resonates with Kristeva’s assertion that the abject marks the moment of individual psychosexual development when the self is separated from the mother in order to distinguish a boundary between "me" and "(m)other" (Felluga 3). Plath’s uncanny representation of motherhood and the domestic space emphasize the “me” and “(m)other“ in order to suggest her speaker exists in the liminal space which “does not respect borders, positions, rules” (Kristeva 4).

The stage of the unhomelike home in which much of Plath’s Ariel era poetry takes place thus becomes the zone through which borders are stretched and interrogated. In one of the poet’s final poems, “Balloons,” a mother surveys her children as they play with party balloons that have “Since Christmas...lived with us.” This traditionally cheerful scene takes on an alien, if not horrific, quality. The balloons have, from the poem’s first stanza, been described as an animate “they” who “live” as “oval soul- animals,” yet they quickly become the “queer moons we live with/ instead of dead furniture!” The balloons are, unlike the furniture, not “dead” (they seem to move of their own volition and respond to sensation by “shrieking” and “delighting”), and yet despite the act that they “live,” the balloons are not quite alive. A balloon becomes, rather, a portal to “a funny pink world” that the children “may eat on the other side of it” and the iconic scene of small children playing with red and green balloons in the days following a holiday becomes a space in which even a child can contemplate a world beyond the world they currently inhabit. Importantly, it is the very act of “living” alongside the uncanny balloons that illuminates their liminal quality and pressurizes the idea that the border space between worlds actually becomes more available the closer it exists to the known. In other words, it is because the balloons have become Heimlich that they must now also be unheimlich, and it is because of the conflation of their familiar status as (dead) objects of domestic celebration with their aura of humanness that they come to represent the repressed.

Plath’s work repeatedly demonstrates the transformation of the familiar to the terrifying as a response (or resistance) to the discovery of an institutionally, politically, spiritually, or culturally imposed boundary. In Plath’s semi- autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar, Esther Greenwood (Plath’s fictional manifestation of herself) famously states:

I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn't quite make out. I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn't make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet. (77)

This passage enacts a double-death; first, of Esther, whose indecision prevents her from eating and second, of the fruit itself, which must be eaten before they “wrinkle and go black.” For many readers, this passage simply evokes the uncertainty of youth.

However, it also serves as an excellent example of the psychic entrapment exposure to “borders, positions, rules” (Kristeva 4) produces in Plath’s speakers. The very familiar ideas of “a husband and a happy home and children,” becoming “a famous poet” or “brilliant professor” or “editor” or traveling the world each become terrifying because to choose one means to repress the rest and to choose none means the death not just of the self, but of the opportunity to have a self.

Plath’s later poetry, especially “Lady Lazarus” and “Daddy,” accepts the impossibility of attempting to balance the unstable psychic economy displayed in Esther Greenwood’s lament. In each of these poems, Plath presents her speaker as a woman who has “made the choice” to be a wife, a daughter, or a sexual object and thus repressed her desire for other choices. This repression reemerges as a dangerous (and dangerously uncanny) protest against the very conditions that manufactured it. That which has been repressed returns as a monstered woman who has the power to destroy the borders that have abjected her; through conflations of time, bodies, identity, and the border between death and life, Plath’s speaker weaponizes her own abjection. Consider, for instance, the speaker’s address to her dead father in “Daddy”:

At twenty I tried to die

And get back, back, back to you.

I thought even the bones would

do.

But they pulled me out of the

sack,

And they stuck me together with

glue.

And then I knew what to do.

I made a model of you,

A man in black with a Meinkampf

look

And a love of the rack and the

screw.

And I said I do, I do.

So daddy, I’m finally through.

The black telephone’s off at the

root,

The voices just can’t worm

through. (58-70)

Once the speaker herself is disassembled and “stuck” back “together with glue” she enters the liminal/abjected space that reveals to her that she has the power to reconstruct her dead father in a shocking conflation of a Nazi/husband in lines, such as the flatly end-stopped “And then I knew what to do.” (sec. 13, line 3) The repressed father reemerges, then, in this uncanny figure, which Plath’s speaker can confront via her own uncanniness. It is the marriage (“And I said I do, I do.”) of monster (“me together with glue”) to monster (“I made a model of you”) that grants her access to the origin (“the root”). In essence, Plath’s speakers are monstered, alien, or uncanny because they are a chimera of remnants (the husband, the wife, the Nazi, the bones, and the glue) housed within a (physically and temporally) present body.

The terrifying quality of Plath’s speaker is not merely that she is a zombie-like figure who eternally reemerges and replays a repressed past in order to destabilize limits, but that she replays a past which was never known to begin with. As in “Daddy,” images, symbols and even languages that are outside Plath’s own realm of psychic identity frequently emerge in order to evoke the uncanny. Critics, such as Irving Howe, Arthur Olberg, and Susan Gubar, have noted Plath’s frequent recourse to Holocaust imagery and identification with Judiasm is, to say the least, an odd point of identification for a white, middle-class, Unitarian-raised woman from Massachusetts. In order to further analyze how the schism between the appropriated collective memory of other races and religions and the individual and highly confessional memory of Plath’s speaker functions, this essay will consider how “gender differences in the act of remembering” (Hirsch and Smith 4) that which was repressed generate a version of the uncanny that is unique to Plath. This distinctively Plathian uncanny merges the poet’s own psychic sense of that “which is familiar and old—established in the mind and which has become alienated from the self only through the process of repression” (217) with a larger cultural psyche of whom the speaker identifies with in defiance of cultural, historical, or social borders, positions, or rules.

(Lady) Lazarus: Cultural Memory and Gender

Marianne Hirsch and Valerie Smith’s “Feminism and Cultural Memory” provides a valuable lens through which to consider Plath’s poetry in regard to the role “the female witness or agent of transmission” plays in memory construction. Hirsch and Smith expand Paul Connerton’s concept of the “act of transfer” to examine the way in which “dynamics of gender and power” are manifested in cultural memories mediated through a female speaker.6 Plath’s persistent presentation of the female speaker as a site of objectification and abjection suggests, then, that to be a woman engaged in the act of remembering is always to mediate the past through the lens of abjection that proposes a permanent slippage between the self and the other. As Arthur Oberg points out, Plath’s late poems, “Daddy,” and its companion piece, “Lady Lazarus,” both incorporate a “movement” which “is at once historical and private; the confusion in these two spheres suggest the extent to which this century has often made it impossible to separate them” (146). Interestingly, Oberg’s analysis of “Daddy” and “Lady Lazarus” omits a consideration of the “historical and private” dichotomy present in these poems as one that is distinctly mediated via the gendered perspective of a suburban white woman. However, his observation that Plath presents these “two spheres” as inextricable suggests that Plath’s speaker’s consciousness of her own status as a housewife is actually quite mimetic of the blurred boundary between the real and the unreal which constitute uncanniness.

Indeed, Plath’s anxiety regarding her domestic status was not unique to the poet; a mere seven days after Plath committed suicide in Primrose Hill, Betty Friedan articulated many of Plath’s central frustrations in The Feminine Mystique. In A Strange Stirring: The Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960’s, historian Stephanie Coontz details the powerful reaction American middle-class women had in response to Freidan’s opus. Within the first months of publication, Friedan received hundreds of letters from women who believed The Feminine Mystique had saved their lives (xx). Friedan recognized the private disappointment of the housewife as well as the deep shame generated by “the silent question—is this All?” (Friedan 1). Presciently, Plath’s work strives to create a grammar with which to address “the problem that has no name” (Friedan 63).

While Freidan clarifies the separation between the public and private spheres in order to argue that the public sphere generated social and political injustice, which served to silence the private sphere, Plath revels in the blurring of the spheres in an attempt to disrupt both. A consideration of the extreme emphasis on gender (specifically in regard to domesticity, motherhood, and the body), which Plath uses to stress “historical and private spheres” further illuminates the manner in which these poems invest themselves in uncanny remembrance. As Hirsch and Smith note, “cultural memory is always about the distribution of and contested claims to power. What a culture remembers and what it chooses to forget are intricately bound up with issues of power and hegemony, and thus with gender” (6). As scholars such as Christina Britzolakis and Susan Gubar have highlighted, “Lady Lazarus” is a complex and fascinating consideration of the relationship between gender and the manner in which secondary memory frames power relations.

“Lady Lazarus” perceives itself retroactively from its first line, “I have done it again.” This declarative, abruptly end-stopped statement emphasizes the performative quality of this dramatic monologue while simultaneously insisting that the moment of performativity is past—it is already “done.” Immediately, a temporal dislocation is established that distances the poem itself from the speaker and the speaker’s recollections. The title of the poem, of course, compounds this sense of dislocation through its allusion to Lazarus of Bethany, the saint whom Christ restored to life four days after his death. While the raising of Lazarus is typically associated with rebirth and the power of Christian belief to triumph over death itself, Plath subverts the traditional reading of this story by assigning Lazarus not just a different gender, but also the title of “Lady.” In this way, Plath forces a reconsideration of the idea of resurrection through the lens of gender and class in order to present this miracle not so much as “re/birth” or “re/surrection,” but rather as a re/inscription or re/impression that is itself a form of repetition compulsion. In Freud and the Scene of Trauma, John

Fletcher provides a useful analysis of the relationship between the uncanny and repetition compulsion:

Freud shifts the emphasis away from the content that is being repeated, with its combination of alien and the déjà vu, to the sheer fact of repetition itself. The uncanny feeling proceeds not from the return of the once familiar but no longer recognized in itself but from what that retention testifies to: the activity of autonomous—daemonic— inner compulsion-to-repeat independent of the content of what is repeated. (320)

In light of Fletcher’s analysis, it is especially significant that Lady Lazarus characterizes her resurrection, ironically, in the diction of commercial media because this particular medium heightens a sense of automated repetition. Like a “jingle,” which makes noise by clattering against itself repeatedly, Lady Lazarus’ resurrection testifies to the compulsion to repeat for the sake of repetition. She sarcastically disregards her “theatrical comeback in broad day” as a context-rich event and is decidedly scornful of the idea that her second birth is “A miracle!”

On the contrary, she claims that her new living body is only a “sort of walking miracle,” which, upon further examination appears to be more akin to an anti-miracle; a monstrous amalgam of the possessions of Holocaust victims. Indeed, it is this very conflation of life and death that generates the intellectual slippage that signifies the uncanny and positions Lady Lazarus as the personification of uncanniness (and, in the same vein, positions the uncanny as the anti-miraculous). We read that Lady Lazarus is resurrected not as a human, but as human form composed of inanimate objects:

...my skin

bright as a Nazi lampshade, My right foot

A paperweight,

My face a featureless, fine Jew linen. (4-9)

While the repetition (and, as many critics have argued, appropriation) of the tragedy of the Holocaust assigns Lady Lazarus’s monologue a distinctly traumatic texture, I would argue that this is not actually a traumatic remembrance, but an uncanny one. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud asserts that trauma manifests itself indirectly through intrusive “remembrances” which have not yet been incorporated into the psyche of the sufferer (7). Trauma scholar Cathy Caruth adapts Freud’s initial theory to a study of literature in order to suggest that intrusive phenomena or unabsorbed affects (and their subsequent effects) cause a trauma survivor’s life narrative to exist in a non- linear narrative that, until recovery from the traumatic event, is contextually “dehistoricized” from the survivor’s own life. It is not until the “unclaimed experience” of the trauma itself can be recalled that a trauma survivor can create a context for the previously unexplained text she has survived, but not yet incorporated into her recollection of personal history (Caruth 2-5). The structure of uncanny remembrance does, in many ways, act as a “double” of the structure of traumatic remembrance; both undergo a period of latency prior to the reincorporation of a memory. However, while the traumatic structure is the incorporation of memory that has been repressed as the result of an external event which could not be understood by the survivor in its moment of impact (i.e., “shellshock”), the uncanny structure is the reincorporation of an internal repression which has always been a component of the psyche and therefore understood on some level, but which has been, critically, repressed or erased. Caruth’s notion of dehistoricization is therefore rendered somewhat inapplicable if Lady Lazarus is considered an uncanny actor instead of a trauma survivor. Subsequently, the implications of this poem in regard to the manner in which traumatic history itself relates to gender and power dynamics becomes significant.

“Lady Lazarus’” disturbing gesture of prosopopoeia (in which victims speak, impossibly, from inside the gas chamber) is conflated with an erotic burlesque performance in order to suggest that Plath’s speaker has a distinctly gendered sense of incorporeality. Lady Lazarus’ tone shifts from boastful to horrific to triumphant as her strip tease reveals not flesh, bone, or even corpse, but the space from which her decomposition took place. She begins her de-materialization with the curious pronouncement, “soon, soon the flesh/ the grave cave ate will be/ at home on me.” The flesh, which has already decomposed (or been “eaten” by the cave), impossibly returns—significantly, it returns to “home,” or the Heimlich. Via the dissolution of the female flesh, Plath has ingeniously constructed a scene in which the process of objectifying the body of Lady Lazarus becomes indistinguishable from the process of abjectifying the body of Lady Lazarus. Lady Lazarus manifests her rage at “the peanut-crunching crowd” who shove “in to see/ them unwrap me hand and foot” in the unveiling of her new form (referred to as “The big strip tease.”) by historically situating (first via the Lazarus Myth and then via the Holocaust) the performance of being a “Lady.”

Significantly, this particular historicization of performance is what assigns this poem its uncanny structure; the speaker is not incorporating the Holocaust or the Lazarus Myth as a part of her own individual memory, rather, she is conflating it directly with her repressed psyche in an act that generates the chimeric Lady Lazarus. Paul Breslin questions Plath’s conflation of myth and reality, asking “...did she fear that the experiential grounds of her emotions were too personal for art unless mounted on the stilts of myth or psycho-historical analogy” (110)? Breslin’s reading of “Lady Lazarus” as a confessional poem in which the poet fears that “the experiential grounds of...emotions” are inherently artless seems to miss the point insofar as Lady Lazarus’ (not Plath’s) “experiential grounds” are presented not so much as “too personal” for the speaker, but for the speaker’s audience. Lady Lazarus’s audience, composed first of “Gentlemen, ladies,” then “Herr Doktor, Herr Enemy” and finally “Herr God, Herr Lucifer” is possessed of an increasingly patriarchal gaze that Lady Lazarus counters with a body which is weaponized by the uncanny conflation of her “psycho-historical” composition. The final five stanzas of “Lady Lazarus” perform a dynamic movement in which the speaker rapidly shifts her presentation of her cultural importance from inanimate yet cherished object to an enraged and murderous reincarnation of her own objectification.

Lady Lazarus begins her transformation with the statement:

I am your opus,

I am your valuable,

The pure gold baby (66-68)

thereby asserting her belief that her body is the grand scale creation (“opus”) of the patriarchal figures she is addressing. Furthermore, she recognizes her worth as a creation is entwined with a certain lack of personal history or identity; the nature of the opus is its triply asserted “purity.” Plath’s use of the word “pure” is, in this context, itself a psycho-historical conflation of the idealization of the virginal female body and the racial policy of the Third Reich. Plath complicates her speaker’s objectified status with the dramatically enjambed line break between this stanza and the next,

That melts to a shriek.

I turn and burn.

Do not think I underestimate

your great concern.(69-71)

The final image of an inanimate “pure gold baby” is gruesomely brought to life in the moment of its murder. This stunning turn is mimetic of the poem’s controlling Lazarus motif; in both instances, the repressed can only emerge from its uncanny status (as living dead or golden baby) through an act of great violence.

In the next two stanzas, we read that this emergence first manifests itself as a palpable nothing, which then transforms into pure symbol:

Ash, ash—

You poke and stir.

Flesh, bone, there is nothing

there—

A cake of soap,

A wedding ring,

A gold filling. (72-77)

While Lady Lazarus was once a compilation of body parts arranged in the shape of a strip tease performer or a construct of beliefs about feminine virtue (an “opus”), the violence of being “poked and stirred” has transformed her from a resurrected body/ideology to nothing at all. The “cake of soap, “wedding ring,” and “gold filling” emerge from the fire as doubly uncanny objects. In one respect, they are uncanny simply because they conceal their horrific origins in the trappings of the familiar. But, more directly to my point concerning gender difference in the act of remembering, these objects symbolize domesticity, marriage, and beauty (respectively).

It is, of course, imperative to observe that Plath has selected these specific objects because they merge the idealized markers of femininity with the repurposed bodies of Holocaust victims. This merger insists that, for Plath, to be female is to be objectified, but more importantly, to be objectified is always to also be abjectified. In Powers of Horror, Kristeva explains, “refuse and corpses show me what I permanently thrust aside in order to live. These body fluids, this defilement, this shit are what life withstands, hardly and with difficulty, on the part of death. There, I am at the border of my condition as a living being (3).” To some degree, we can read that Plath’s speaker has “permanently thrust aside” her own subjectivity in order to “theatrically” project that which only “feels real.” The severe juxtaposition between these object’s double connotations has been deemed appropriative by many critics, question “the poet’s ‘right’ to Holocaust imagery” (Young 133). While some scholars have questioned Plath’s ethics, others have questioned her sense of poetic scale, such as Irving Howe, who argues that, “it is decidedly unlikely” that the conditions of Jews living in the camps “was duplicated in a middle-class family living in Wellesley, Massachusetts, even if it had a very bad daddy indeed” (12-13). It is at the juncture of these two critiques (one which suggests Plath’s identification is unethical and the other which suggests it is overwrought) that complex issues of gendered memory begin to emerge and a consideration of the manner in which the uncanny presents itself as the mode by which the repressed makes itself apparent becomes salient to our understanding of Plath’s controversial use of prosopopoeia and allusion.

“Dying is an art”: Performing the Uncanny

For Plath, the uncanny took on a political potential precisely because it is an aesthetic divorced from ethical matters; it inherently privileges being present—or, bringing to the surface that which has been repressed—over all other considerations. The political potential of the uncanny (to disturb an idealized version of the female body; to make monstrous the object of the gaze; to question norms regarding motherhood and domesticity) is founded in its ability to articulate a history of which its speaker has not participated, but rather articulated as emblems of her own circumstances. In this way, Plath’s uncanny aesthetic has a radical capacity to disturb, or even rupture, the continuous, cohesive, and widely accepted historical narrative that instances of the uncanny necessarily place in doubt because its very essence is to resist comprehension. The political potential of the uncanny therefore rests in an ability to bring what is incomprehensible, unacceptable, or taboo to the center of conscious; quite actually, the uncanny gives voice to the dead.7

The Lazarus myth, on one hand, is a seemingly clear analogy for the repressed in the sense that Lazarus represents that which is repressed and dead to us, ergo, his resurrection signals a clear return to the repressed. Lazarus, as one risen from the dead, is both dead and alive in an exemplification of the slippage which is the fundamental hallmark of the uncanny. However, I argue that, although he is arisen from the dead, Lazarus of Bethany would not be classified by Freud as an uncanny actor at all. On the contrary, Lazarus would be considered quite canny according to Freud’s definition, which stresses “intellectual uncertainty”8 as the hallmark of an uncanny experience. Within its Biblical (and canonical) context, the Lazarus narrative is given prominence because it is emblematic of Christ’s power “over the last and most irresistible enemy of humanity—death” (Tenney). Rhetorically, the Lazarus Miracle is an act of witnessing intended to deny the ambiguity of death, therefore refusing the concept of the living dead. In other words, although Lazarus is arisen from the dead, he is defined by the miraculous certainty of his life. The Lazarus Myth, then, is decidedly canny because there is no question or uncertainty whatsoever regarding the narrator’s reliability. Rather, to witness the Rising of Lazarus is to experience the total certainty of faith itself.

Plath’s own version of the Lazarus myth, on the contrary, ruptures the continuous, highly canonical narrative presented in the Gospel of John via a reframing of the myth told from the voices of those who have been historically silenced and, subsequently, reincorporated into archival memory. Plath’s Lady Lazarus is, rather, an apocryphal speaker who asserts her own version of history told from the unstable zone of repressed memory. To return to Hirsch and Smith’s “Feminism and Cultural Memory,” Lady Lazarus serves as “the female witness or agent of transmission” who actually comes to perform the archive in which “dynamics of gender and power” are made manifest. Vast components of this archive are, however, unavailable to Lady Lazarus because they have not been incorporated into the collective memory and, therefore, lack the social, historical, and cultural structures that could contextualize those memories and, indeed, provide the vocabulary necessary to articulate them. As mentioned earlier, Plath utilizes an uncanny poetic technique in order to express that “which is familiar and old— established in the mind and which has become alienated from the self only through the process of repression” (The Uncanny 217). Plath’s uncanny poetics stress the particularly gendered nature of this self-alienation in several ways: 1.) Her use of prospopoeia conflates the objectified female body (grotesquely separated into pieces by the audience’s gaze) with pieces of Holocaust victim’s repurposed bodies in order to suggest that gaze itself transforms the body into a material, inanimate object whose crisis can be articulated only via the voices of the victims of genocide, who have themselves been made objects. 2.) While Plath’s use of prospopoeia frames the always gendered experience of being the object of the gaze through the historically canonical (and accepted) experience of survivors, her use of allusion frames her private experience as a suicide survivor through allusions to commercial culture, the Bible, and the atrocity of the Holocaust. These allusions combine to create an impossible amalgamation which suggests that the repressed elements of Lady Lazarus’ psyche can only resurface as a monstrous collage which borrows pieces from the history of others in order to write the history of her own alienation. It is important to note that in her biographical references to her three suicide attempts, Plath is acutely self- aware that she is suffering from repetition compulsion. I have already discussed the first line of the poem (“I have done it once again.”), in which Plath establishes the poem’s temporal dislocation; this line also immediately establishes the speaker’s awareness that she is to be denatured and yet, are regarded as triumphs to the speaker, who victoriously states:

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well. (42-22)

Freud originally developed his theory of the phenomenon of repetition compulsion in his 1914 essay, “Remembering, Repeating, and Working-Through” as a pattern wherein an individual interminably repeats patterns of behavior that were established during a period of trauma in earlier life. It is clear that Plath’s speaker is repeating the trauma of a suicide attempt and, in fact, she goes so far as to provide a timeline (we learn that “One year in every ten” an attempt is made; that the first attempt occurred at the age of ten years old; the second at twenty; that the speaker is “only thirty”; and, finally, that Lady Lazarus is monologizing the third of “nine times to die”) which further articulates the sense that the speaker is highly aware of her compulsion to repeat.

This compulsion is, in fact, an orchestrated performance. It is this quality of orchestration and performativity that transitions Lady Lazarus’ compulsion to repeatedly reenact her suicide attempt from a traumatic memory structure to an uncanny one. Freud again revisits the concept of repetition compulsion in The Uncanny (five years after its original inception) in order to suggest that the uncanny is also the result of an event that has been superseded in one’s psychic life and therefore serves as a reminder not of a suppressed external event, but a repressed internal event. The repressed internal event of “Lady Lazarus” does not, in fact, seem to be the speaker’s suicide attempts; we read, via the total recall and articulation with which the attempts are conveyed, that these suicide attempts are fully incorporated into the speaker’s psyche. Rather, the speaker seems to have repressed the very constructs (of history, commerce, and religion) that have combined to assign her a gendered identity.

Lady Lazarus’ sense that nothing is every truly erased, forgotten, or lost via repression becomes uncanny precisely because the events that she has repressed emerge as the memories and experiences of others via her use of allusion and prosopopoiea. As Maurice Halbwachs, who developed the concept of collective memory, has suggested, memory is one of the elements of our social architecture that binds us to one another (22-49). Halbwachs’ foundational principles of memory theory, combined with Caruth’s previously mentioned trauma theory, suggests that the traumatic memory is that which both binds and refuses to be past. To position this within its psychoanalytic context, a collective is bound by the event that contains so much force its trace refuses to fade or be erased from the collective’s historical or narrative understanding of history. In this way, then, “Lady Lazarus’” speaker’s inability to convey her trauma without borrowing from events such as the Holocaust or the Lazarus Myth in order to articulate her rage at constructs of gender indicates a larger cultural amnesia and repression. Trauma historian Judith Herman points out that a traumatic event can only come into consciousness once a political event (such as a war, election, etc.) has occurred which provides culture with the language to articulate the conditions of the trauma. The trauma that “Lady Lazarus” seeks to articulate, however, predates the language provided by the Women’s Movement and therefore must co-opt the language of other tragedies in a gesture which bears the uncanny marker of a psychic economy which has gone bankrupt; which must use currency which is not its own.

“Like air”: The Monstrous Nothing

In the last two stanzas of “Lady Lazarus,” the reader once again witnesses a violent rebirth of the speaker. Unlike the resurrections that have played out in the poem’s previous twenty-six stanzas, this final act of transmogrification appears to have produced a new result. Lady Lazarus emerges as a sort of monstrous feminine figure to deliver a message of warning to yet another conflation of history, myth, and religion in the address:

Herr God, Herr Lucifer

Beware

Beware. (78-80)

One is reminded, here, of Plath’s similar gesture in the poem “Daddy,” in which the speaker addresses her father: “ used to pray to recover you/ Ach, du // In the German tongue, in the Polish town...” It seems that in the moment of direct articulation or confrontation with the systems that have repressed the speaker, she must borrow the language (“tongue”; “Herr”) of the oppressor themselves to make herself understood. However, Plath begins to signal towards an inversion of this incorporation of oppressor to oppressed in the above stanza’s rhyme scheme. Just as the hard rhyme of “Herr” with the repeated “Beware” sonically9 indicates to the reader that the oppressive forces have, quite actually, become a part of Lady Lazarus��� language, the poem’s final stanza suggests that the uncanny archive from which Lady Lazarus has expressed herself throughout the poem has now been weaponized and is capable of not just incorporating, but devouring, the oppressor:

Out of the ash

I rise with my red hair

And I eat men like air. (81-83)

Enraged, Lady Lazarus rises from nothing (the “ash” of the crematoria) with the ability to, in turn, regard the constructs that have degraded her as nothing (“air”).

By the end of the “Lady Lazarus,” Plath has transitioned genres: what was once horrifically uncanny is now only horrific. A differentiation of the uncanny from the horrific is necessary here. While the uncanny often displays elements of the horrific (such as feelings of fear, dread, repulsion, and terror) the horrific is founded in a “fear of the unknown” (Lovecraft). The uncanny, conversely, is founded in a fear of the reemergence of that which was once known, but has been forgotten. Lady Lazarus is horrific when she emerges to “eat men like air,” but, importantly, the texture of intellectual uncertainty which was prominent in her previous manifestations is now gone. She “rise[s]” with her “red hair” as a fully recognizable woman; this last line is the poem’s first presentation of Lady Lazarus as analogous to an incarnation of Plath herself that is not conflated with death. The autobiographical detail, “red hair,” directs the reader towards a corporeal, intellectually certain rendering of Plath as woman (not a woman/corpse or woman/myth).

This moment is also significant in the larger context of Ariel’s highly symbolic color scheme. As Eileen M. Aird points out, “The world of Ariel is a black and white one into which red, which represents blood, the heart and living is always an intrusion” (85). The color red’s significance to Ariel’s symbolic order is perhaps best articulated in “Tulips,” a poem in which the speaker emerges from the white, sterile world of the hospital to the vivid, living world represented by the tulips by her bedside. In the following passage, we read red as both the marker of life and the marker of that which cannot be attained:

And I am aware of my heart: it

Opens and closes

Its bowl of red blooms out of

sheer love of me.

The water I taste is warm and

salt, like the sea

And comes from a country far

away as health. (60-64)

The reemergence of red in “Lady Lazarus,” signals that the speaker is no longer only an observer of “a country far away as health,” but a citizen of it. In accordance with the larger world of Ariel, Lady Lazarus’ red hair indicates that she is no longer speaking in an uncanny voice via a return to the repressed as symbolized by personification of the dead, but that she is now speaking in the horrific voice of a woman who has returned to her own body to “eat men like air.”

Interestingly, a consideration of Plath as an artist consciously evoking elements of horror positions her much more directly as a precursor to movements of political art during the 1970’s which were directly in dialogue with the Women’s Movement. In The Feminist Uncanny in Theory and Art Practice, Alexandra M. Kokoli considers the work of the visual artists in order to define and explore the political power of uncanny representations of femininity.10 Kokoli argues:

Feminine writing takes place when the culturally repressed return with a vengeance, when the long censored and (presumed) impossible erupts into language and the world, throwing it into ‘chaosmos.’ [...] in which witches and female monsters are not merely reclaimed but reimagined as symbols of resistance and even revolutionary agents. (1-2)

A consideration of Plath’s own “Lady Lazarus” as a “female monster” birthed from an uncanny archive positions Plath’s speaker as an agent of destruction who can speak the culturally and politically “impossible.” This consideration also removes Plath from her long-held position as a “confessional” poet primarily invested in the speaker’s interiority. Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of the Plathian uncanny, however, is the promise that the monstered speaker is “the same, identical woman” as the confessional speaker who began the poem. Perhaps it is the insistence that for Plath, female interiority is itself alien, eerie, and by nature, repressed, which is the most horrific element of her poetry.

Footnotes

Jo Gill offers a comprehensive overview of the manner in which Plath’s treatment of themes regarding “the process of transformation, translocation and even dislocation” (43) develop throughout the poet’s career. Gill considers representations of both natural and artificial environments, ranging from physical transformation to alien dislocation beginning in Plath’s juvenilia and ending with her posthumous Ariel poems. Likewise, Mary Lynn Broe provides a psychoanalytic interpretation of subjectivity in Plath’s early and mid-career poetry that considers the fragmentary nature Plath’s speaker’s psyche.

“The Magic Mirror: A Study of the Double in Two of Dostoyevsky’s Novels” was submitted as a component of Plath’s Special Honors in English at Smith College in 1955.

Plath biographer Frances McCullough argues that the poet reached cross-continental renown in the years between the publication of Ariel in 1964 and The Bell Jar in 1971 due to the influence of the Woman’s Movement, which politicized the contents of Plath’s work written in an era that was “pre-drugs, pre-Pill, pre- Women’s studies” (9). Anne Stevenson and Linda Wagner-Martin concur with McCullough’s reading; Stevenson claims Plath as “a heroine and martyr of the Woman’s Movement” (Two Views of Plath 1994) while Wagner-Martin states, “Like Friedan’s 1963 The Feminine Mystique,” Plath’s Ariel and The Bell Jar were “both a harbinger and an early voice of the Woman’s Movement” (Two Views of Plath 1995).

Notably, Marilyn Boyer considers the body in “The Disabled Female Body as a Metaphor for Language in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar” by utilizing a mixture of feminist and disability studies (with an emphasis on theories provided by Julia Kristeva and Jacques Lacan) in order to examine “The mind/body connection, or more pointedly, its dis-connection” (199) in The Bell Jar.

...

Hirsch and Smith define an “act of transfer” as “ an act in the present by which individuals and groups constitute their identities by recalling a shared past on the basis of common, and therefore often contested, norms, conventions, and practices. These transactions emerge out of a complex dynamic between past and present individual and collective, public and private, recall and forgetting, power and powerlessness, history and myth, trauma and nostalgia, conscious and unconscious fears or desires. Always mediated, cultural memory is the product of fragmentary personal and collective experiences articulated through technologies and media that shape even as they transmit memory” (5).

It is notable that Plath chooses to “give voice to the dead” not via a spectered medium, but via the risen dead (or, the zombie). In this way, Plath again stresses the idea of the body as an object separate from its own subjectivity; she is also able to further emphasize the abject nature of the rotting corpse.

Freud builds his definition of the uncanny upon Ernst Jentsch’s 1906 essay, “On the Psychology of the Uncanny,” in which Jentsch argues the uncanny occurs when there is intellectual uncertainty as to whether or not a being is animate or inanimate. Jentsch considers the “The Sandman’s” uncanny doll, Olympia, to be the signifier of the uncanny. Freud extends this consideration of the animate/inanimate binary, arguing that in uncanny literature, the uncanny becomes apparent when the reader themselves experiences intellectual uncertainty regarding whether or not the events related by the narrator are real or imagined.

Christina Britzolakis considers the sonic elements of the Ariel poems for their departure from Plath’s earlier narrative strategies of subject-based dislocation in favor of poetic strategies reliant on sound sense and “oral/aural, incantatory element[s] at the level of language” (170).

In particular, Kokoli examines the work of Judy Chicago, Faith Wilding, and Robin Weltsch.

Works Cited

Breslin, Paul. “Sylvia Plath: The Mythically Fated Self.” The Psycho-Political Muse: American Poetry Since the Fifties. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Broe, Mary Lynn. The Protean Poetic: The Poetry of Sylvia Plath. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1980.

Caruth, Cathy. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, narrative and history. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Connerton, Paul. How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Coontz, Stephanie. A Strange Stirring: The Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s. New York: Basic Books, 2011.

Coyne, Kelly Marie. “The Magic Mirror”: Uncanny Suicides, from Sylvia Plath to Chantal Ackerman. Georgetown University, PhD Dissertation. 2017.

----“The Many Faces of Sylvia Plath.” Literary Hub. 27 Oct. 2017, http://lithub.com/the-many-faces-of-sylvia-plath/ Accessed: 23 February 18.

Curry, Renée R. White Women Writing White: H.D., Elizabeth Bishop, Sylvia Plath, and Whiteness. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000.

Aird, Eileen M. From Sylvia Plath: Her Life and Work. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1973.

Annas, Pamela J. A Disturbance in Mirrors: The Poetry of Sylvia Plath. New York: Greenwood Press, 1988.

Britzolakis, Christina. Sylvia Plath and the Theatre of Mourning. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999.

Boyer, Marilyn. “The Disabled Female Body as a Metaphor for Language in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar.” Women's Studies, 33.2, 2004, 199-223. Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Chiacgo: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Freud, Sigmund. Beyond the Pleasure Principle. W. W. Norton & Company; The Standard Edition, 1990.

----The Uncanny. New York: Penguin Classics, 2003.

----“On the Sexual Theories of Children.” London: Read Books Limited, 2014.

----Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through. London: Hogarth Press, 1958.

Betty Friedan. The Feminine Mystique. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997 The Cambridge Companion to Sylvia Plath, edited by Jo Gill. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Felluga, Dino Franco. Critical Theory: the Key Concepts. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Fletcher, John. Freud and the Scene of Trauma. New York: Fordham University Press, 2014.

Gubar, Susan. “Prosopopœia and Holocaust Poetry in English: Sylvia Plath and Her Contemporaries.” The Yale Journal of Criticism 14.1, 2001, 191-215. Halbwachs, Maurice and Lewis A. Coser. On Collective Memory. University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Herman, Judith. Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

Hirsch, Marianne and Valerie Smith. “Feminism and Cultural Memory: An Introduction.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28.1, 2002, 1-19.

Howe, Irving. “Letter to the Editor.” Commentary. 1974.

Irigaray, Luce. The Sex Which is Not One. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Kroll, Judith. Chapters in a Mythology: The Poetry of Sylvia Plath. New York: Harper Colophon Edition, 1978.

Kokoli, Alexandra M. The Feminist Uncanny in Theory and Art Practice. Camden: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016.

Lant, Kathleen Margaret. “The Big Strip Tease: Female Bodies and Male Power in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath.” Contemporary Literature, 34.4, 1993, 620–669.

Lovecraft, H.P. Supernatural Horror in Literature. The Palingenesis Project (Wermod and Wermod Publishing Group), 2013.

McCollough, Frances. “Introduction.” The Bell Jar. New York: Harper, 1971.

Miller, Ellen. “Philosophizing with Sylvia Plath: An Embodied Hermeneutic of Color in ‘Ariel’". Philosophy Today, 46.1, 2002, 91-101

Tenney, Merril C., Kenneth L. Barker & John Kohlenberger III, ed. Zondervan NIV Bible Commentary. Nashville: Zondervan Publishing House, 1994.

Oberg, Arthur. Modern American Lyric: Lowell, Berryman, Creely, and Plath. New Brunskwick: Rutgers University Press, 1978.

Plath, Sylvia. Ariel: The Restored Edition. New York: Faber & Faber, 2010.

Stevenson, Anne. Two Views of Plath’s Life and Career—By Linda Wagner-Martin and Anne Stevenson. Modern American Poetry, 1994. Web. 26 February 2018.

Wagner-Martin, Linda. Two Views of Plath’s Life and Career—By Linda Wagner-Martin and Anne Stevenson. Modern American Poetry, 1995. Web. 26 February 2018.

Yorke, Liz. Impertinent Voices: Subversive Strategies in Contemporary Women’s Poetry. Abingdon: Routledge, 1991

Young, James. “’I may be a of a Jew’: The Holocaust Confessions of Sylvia Plath.” Philological Quarterly, 66.1, 1987, 127-147.

#sylvia plath#poetry#analysis#uncanny#unheimlich#lazarus myth#the holocaust in literature#cultural memory#gender#the monstrous feminine#julia kristeva#abjection#literature

1 note

·

View note

Photo

via Flora The Bookish Witch on Pinterest

...

MAD GIRL’S LOVE SONG

A Villanelle

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my lids and all is born again.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

The stars go waltzing out in blue and red,

And arbitrary blackness gallops in:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I dreamed that you bewitched me into bed

And sung me moon-struck, kissed me quite insane.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

God topples from the sky, hell’s fires fade:

Exit seraphim and Satan’s men:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I fancied you’d return the way you said,

But I grow old and I forget your name.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

I should have loved a thunderbird instead;

At least when spring comes they roar back again.

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

–Sylvia Plath, written 1954, The Collected Poems, 1981

#sylvia plath#Mad Girl's Love Song#sylvia plath tattoos#mad girl's love song tattoos#sylviaplath#chest tattoo#sylvia plath quotes#The Collected Poems#sylvia plath juvenilia#tattoos#literary tattoos#poem tattoos

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sylvia Plath, Collected Poems: Juvenilia; from ‘April 18’

TEXT ID: the slime of all my yesterdays rots in the hollow of my skull

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

'There is more than one good way to drown.'

Sylvia Plath, Collected Poems: Juvenilia; from 'Epitaph in Three Parts'

268 notes

·

View notes

Photo

via Twitter @LeapGilead

(Please don’t forget to also like the picture there)

ADMONITION

If you dissect a bird

To diagram the tongue

You'll cut the chord

Articulating song.

If you flay a beast

To marvel at the mane

You'll wreck the rest

From which the fur began.

If you assault a fish

To analyze the fin

Your hands will crush

The generatihg bone.

If you pluck out the heart

To find what makes it move,

You'll halt the clock

That syncopates our love.

--Sylvia Plath, in: The Collected Poems, Juvenilia 1952-1956, 1981

#sylvia plath#tattoos#sylvia plath tattoos#sylviaplath#literary tattoos#admonition#sylvia plath poetry#sylvia plath poems#sylvia plath quotes#sylvia plath juvenilia#The Collected Poems#juvenilia#arms#arm tattoo

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Submitted by Gabriel Dominato (https://www.facebook.com/lit.dominato)

Done in Maringá/PR, Brazil on 27 October 2018, Sylvia Plath’s 86th birtday! ❤

I love love looove it! And Gabriel is wonderful! ❤

***

Mad Girl’s Love Song

A Villanelle

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my lids and all is born again.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

The stars go waltzing out in blue and red,

And arbitrary blackness gallops in:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I dreamed that you bewitched me into bed

And sung me moon-struck, kissed me quite insane.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

God topples from the sky, hell’s fires fade:

Exit seraphim and Satan’s men:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I fancied you’d return the way you said,

But I grow old and I forget your name.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

I should have loved a thunderbird instead;

At least when spring comes they roar back again.

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

--Sylvia Plath, written 1954, The Collected Poems, 1981

#sylvia plath#submission#Mad Girl's Love Song#The Collected Poems#legs#sylviaplath#tattoos#literary tattoos#sylvia plath tattoos#mad girl's love song tattoos#sylvia plath juvenilia

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! Do you have any quotes whose descriptions are just really beautiful or figurative?

"Oh yes, skin black. Very black. So black that only a steady careful rubbing with steel wool would remove it, and as it was removed there was the glint of gold leaf and under the gold leaf the cold alabaster and deep, deep down under the cold alabaster more black only this time the black of warm loam."

— Toni Morrison, from 'Sula'

"...but the rain / Is full of ghosts tonight, that tap and sigh / Upon the glass and listen for reply,"

— Edna St. Vincent Millay, The Harp-Weaver; from 'xlii'

"Nothing compares to your hands nothing like the green-gold of your eyes. My body is filled with you for days and days, you are the mirror of the night, the violent flash of lightning. the dampness of the earth."

"You are here, intangible and you are all the universe which I shape into the space of my room. Your absence springs trembling in the ticking of the clock, in the pulse of light; you breathe through the mirror."

— Frida Kahlo, from The Diary of Frida Kahlo, tr. Barbara Crow de Toledo & Ricardo Pohlenz

"The sight filled the northern sky; the immensity of it was scarcely conceivable. As if from Heaven itself, great curtains of delicate light hung and trembled. Pale green and rose-pink, and as transparent as the most fragile fabric, and at the bottom edge a profound and fiery crimson like the fires of Hell, they swung and shimmered loosely with more grace than the most skilful dancer."

— Philip Pullman, from 'Northern Lights'

"Often when I imagine you / your wholeness cascades into many shapes. / You run like a herd of luminous deer / and I am dark, I am forest."

— Rainer Maria Rilke, Book of Hours: Love Poems to God; from ‘Du kommst und gehst. Die Türen fallen’, tr. Anita Barrows & Joanna Macy

"My right hand unfolds rivers / around you, my left hand releases its trees, / I speak rain, / I spin you a night and you hide in it."

— Margaret Atwood, from 'Power Politics'

"Once I wounded him with so / small a thorn / I never thought his flesh would burn / or that the heat within would grow / until he stood / incandescent as a god; / now there is nowhere I can go / to hide from him: / moon and sun reflect his flame."

— Sylvia Plath, Collected Poems: Juvenilia; from ‘To a Jilted Lover’

"She wore a gown the colour of storms, shadows and rain and a necklace of broken promises and regrets."

— Susanna Clarke, from 'Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell'

"…him pressing against / me, his lips at my neck, and yes, I do believe / his mouth is heaven, his kisses falling over me / like stars."

— Richard Siken, Crush; from 'Saying Your Names'

"Flower after flower is specked on the depths of green. The petals are harlequins. Stalks rise from the black hollows beneath. The flowers swim like fish made of light upon the dark, green waters. I hold a stalk in my hand. I am the stalk. My roots go down to the depths of the world, through earth dry with brick, and damp earth, through veins of lead and silver. I am all fibre. All tremors shake me, and the weight of the earth is pressed to my ribs. Up here my eyes are green leaves, unseeing."

— Virginia Woolf, from 'The Waves'

And a song: 'Pale September' by Fiona Apple

190 notes

·

View notes