#ruhr uprising

Photo

Members of the Red Ruhr Army during the Ruhr uprising, 1920

#weimar republic#weimar era#rote ruhrarmee#red army#ruhr uprising#german history#germany#rote armee#deutsche geschichte#ruhrgebiet#socialism#communism

136 notes

·

View notes

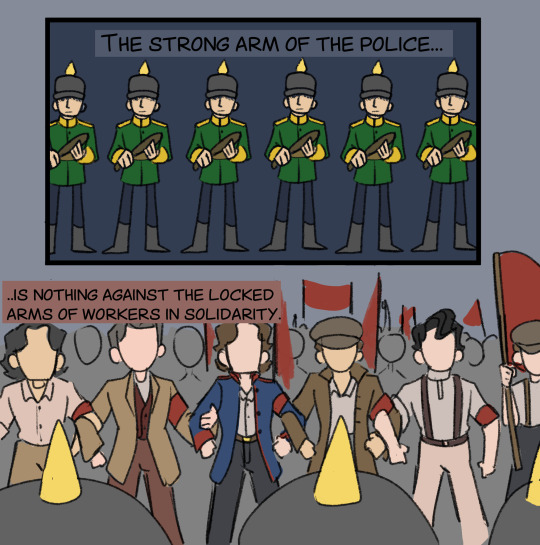

Text

An event from the story known as the Ruhr Uprising of 1876. Brandt and other groups rose against the Kaiser, only to be utterly crushed. This led to his exile in England.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

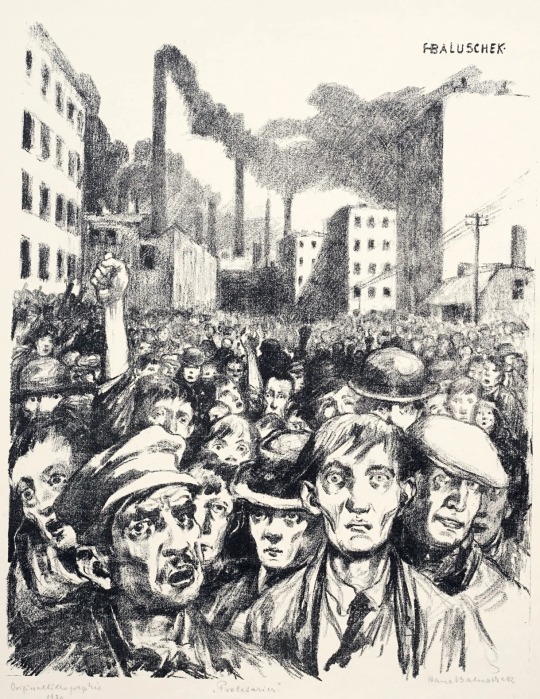

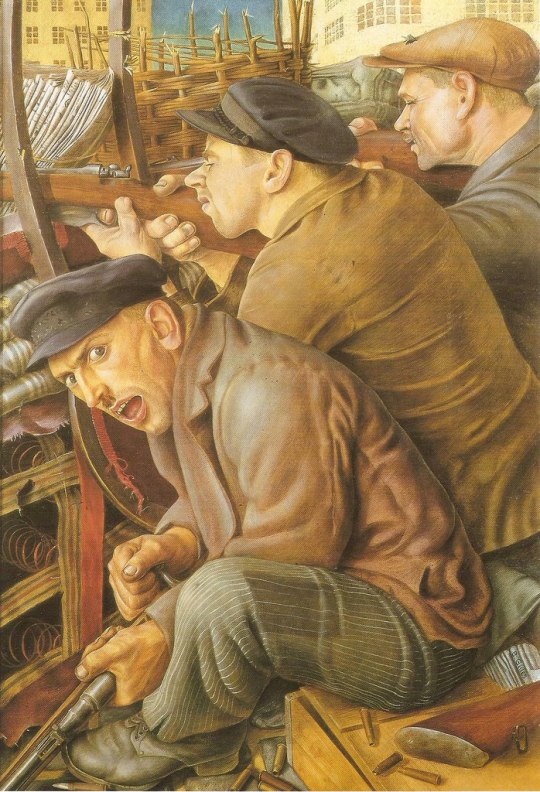

Proletarier (Proletarians), 1920,

Hans Baluschek (1870, Breslau/Wroclaw - 1935, Berlin),

Lithograph, 34 x 27 cm, private collection.

Source: MutualArt

(This may be about the Ruhr Uprising in March 1920.)

0 notes

Text

Events 5.16

946 – Emperor Suzaku abdicates the throne in favor of his brother Murakami who becomes the 62nd emperor of Japan.

1204 – Baldwin IX, Count of Flanders is crowned as the first Emperor of the Latin Empire.

1364 – Hundred Years' War: Bertrand du Guesclin and a French army defeat the Anglo-Navarrese army of Charles the Bad at Cocherel.

1426 – Gov. Thado of Mohnyin becomes king of Ava.

1527 – The Florentines drive out the Medici for a second time and Florence re-establishes itself as a republic.

1532 – Sir Thomas More resigns as Lord Chancellor of England.

1568 – Mary, Queen of Scots, flees to England.

1584 – Santiago de Vera becomes sixth Governor-General of the Spanish colony of the Philippines.

1739 – The Battle of Vasai concludes as the Marathas defeat the Portuguese army.

1770 – The 14-year-old Marie Antoinette marries 15-year-old Louis-Auguste, who later becomes king of France.

1771 – The Battle of Alamance, a pre-American Revolutionary War battle between local militia and a group of rebels called The "Regulators", occurs in present-day Alamance County, North Carolina.

1811 – Peninsular War: The allies Spain, Portugal and United Kingdom fight an inconclusive battle against the French at the Albuera. It is, in proportion to the numbers involved, the bloodiest battle of the war.

1812 – Imperial Russia signs the Treaty of Bucharest, ending the Russo-Turkish War. The Ottoman Empire cedes Bessarabia to Russia.

1822 – Greek War of Independence: The Turks capture the Greek town of Souli.

1832 – Juan Godoy discovers the rich silver outcrops of Chañarcillo sparking the Chilean silver rush.

1834 – The Battle of Asseiceira is fought; it was the final and decisive engagement of the Liberal Wars in Portugal.

1842 – The first major wagon train heading for the Pacific Northwest sets out on the Oregon Trail from Elm Grove, Missouri, with 100 pioneers.

1866 – The United States Congress establishes the nickel.

1868 – The United States Senate fails to convict President Andrew Johnson by one vote.

1874 – A flood on the Mill River in Massachusetts destroys much of four villages and kills 139 people.

1877 – The 16 May 1877 crisis occurs in France, ending with the dissolution of the National Assembly 22 June and affirming the interpretation of the Constitution of 1875 as a parliamentary rather than presidential system. The elections held in October 1877 led to the defeat of the royalists as a formal political movement in France.

1888 – Nikola Tesla delivers a lecture describing the equipment which will allow efficient generation and use of alternating currents to transmit electric power over long distances.

1891 – The International Electrotechnical Exhibition opened in Frankfurt, Germany, featuring the world's first long-distance transmission of high-power, three-phase electric current (the most common form today).

1916 – The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the French Third Republic sign the secret wartime Sykes-Picot Agreement partitioning former Ottoman territories such as Iraq and Syria.

1918 – The Sedition Act of 1918 is passed by the U.S. Congress, making criticism of the government during wartime an imprisonable offense. It will be repealed less than two years later.

1919 – A naval Curtiss NC-4 aircraft commanded by Albert Cushing Read leaves Trepassey, Newfoundland, for Lisbon via the Azores on the first transatlantic flight.

1920 – In Rome, Pope Benedict XV canonizes Joan of Arc.

1925 – The first modern performance of Claudio Monteverdi's opera Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria occurred in Paris.

1929 – In Hollywood, the first Academy Awards ceremony takes place.

1943 – The Holocaust: The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising ends.

1943 – Operation Chastise is undertaken by RAF Bomber Command with specially equipped Avro Lancasters to destroy the Mohne, Sorpe, and Eder dams in the Ruhr valley.

1951 – The first regularly scheduled transatlantic flights begin between Idlewild Airport (now John F Kennedy International Airport) in New York City and Heathrow Airport in London, operated by El Al Israel Airlines.

1959 – The Tritons' Fountain in Valletta, Malta is turned on for the first time.

1960 – Theodore Maiman operates the first optical laser (a ruby laser), at Hughes Research Laboratories in Malibu, California.

1961 – Park Chung-hee leads a coup d'état to overthrow the Second Republic of South Korea.

1966 – The Chinese Communist Party issues the "May 16 Notice", marking the beginning of the Cultural Revolution.

1969 – Venera program: Venera 5, a Soviet space probe, lands on Venus.

1974 – Josip Broz Tito is elected president for life of Yugoslavia.

1975 – Junko Tabei from Japan becomes the first woman to reach the summit of Mount Everest.

1988 – A report by the Surgeon General of the United States C. Everett Koop states that the addictive properties of nicotine are similar to those of heroin and cocaine.

1991 – Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom addresses a joint session of the United States Congress. She is the first British monarch to address the U.S. Congress.

1997 – Mobutu Sese Seko, the President of Zaire, flees the country.

2003 – In Morocco, 33 civilians are killed and more than 100 people are injured in the Casablanca terrorist attacks.

2005 – Kuwait permits women's suffrage in a 35–23 National Assembly vote.

2011 – STS-134 (ISS assembly flight ULF6), launched from the Kennedy Space Center on the 25th and final flight for Space Shuttle Endeavour.

2014 – Twelve people are killed in two explosions in the Gikomba market area of Nairobi, Kenya.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Occupation of the Ruhr, Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Begins

Occupation of the Ruhr, Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Begins

To explore these themes, check out the complete films showcased in this video here: 100 Years – Occupation of the Ruhr https://www.britishpathe.com/workspaces/df699ffd537d4e0c74710ad015dfd64d/vJRkcrfG 80 Years – Casablanca Conference https://www.britishpathe.com/workspaces/df699ffd537d4e0c74710ad015dfd64d/lQgWn0SB 70 Years – Tito Becomes President of Yugoslavia…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Proletarians of the Red Ruhr Army in Westenhellweg, Dortmund during the Ruhr uprising 1920.

The Red Ruhr Army was an army of between 50,000 and 80,000 left-wing workers, mostly communists, but also anarcho-syndicalists and some left socdems.

After calling a general strike on 14 March, the Red Ruhr Army defeated the Freikorps and regular army units in the area and started the uprising. The government sent in regular and paramilitary forces, killing an estimated 1,000 workers and suppressing the revolt.

While the bourgeoisie feared a Marxist uprising, 300,000 mine workers supported the Ruhr Red Army. The strikers took over Düsseldorf, Elberfeld, and Essen, and soon had control over the whole Ruhr area.

It was the largest armed workers' uprising in the nation's history, and ran from 13 March to 2 April, 1920, in Germany's most important industrial area. The workers were reacting to the Kapp Putsch, an effort by right-wing forces in March 1920 to overthrow the elected government.

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

German Communist Red Artillery fighters load a trench mortar during the uprising in the Ruhr, March-April 1920.

#Marxism#German revolution#Weimar Germany#Ruhr uprising#Red Ruhr Army#KPD#KAPD#socialism#communism#photos

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

people talk about the killing of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebenecht by Freikorps paramilitary soldiers acting on behalf of the Social Democratic government of Weimar Germany but i feel like something that also needs to get mentioned in those discussions is that about a year later the Kapp Putsch happened which was an attempted coup lead by ultranationalists, militarists, fascists, monarchists, the Freikorps and other far-right groups who wanted to overthrow the Weimar Republic and establish an antirepublican dictatorship which would abrogate the Treaty of Versailles and seek to reestablish German military dominance and aggression..

The coup was defeated and nothing like that would ever happen again in Germany but compared to the more famous Beer Hall Putsch of Hitler the Kapp Putch was a much more serious threat and the government was even forced to flee from Berlin. Anyway the way the coup was defeated is the Social Democrat government reached out to the radical left and they put aside differences and organized the largest general strike in German history and one of the largest in European history which paralyzed the economy and caused the coup attempt to lose steam and flounder thus saving the republic for the time being.

Anyway in the heavily industrialized Ruhr Valley the workers continued to strike not feeling satisfied with the concessions given in the aftermath of the failure of the coup attempt. The Ruhr workers belonged primarily to radical left political organizations but were otherwise ideologically diverse with some areas being social democratic, some communist and some anarchist. Negotiations between the government and workers broke down in large part due to the actions of the military (which largely supported the coup at least with officers) opening fire on workers despite orders from the government to the contrary. This resulted in the workers renewing a call for a general strike and the Social Democrat government in Berlin reacted by asking their former enemies of the Freikorps (who had been given generous amnesty) to go in and put the workers under control so the factories and mines can revert to their private owners and this happened in an extremely bloody manner with mass killings and summary executions. So basically just barely a year after fears about the Freikorps were literally validated in that they attempted to overthrow the republic (which they had always proclaimed as illegitimate and never engaged in good relations with) the government still employed them to crush a worker’s uprising immediately afterwards.

So like, I think that sorta thing is just relevant to mention since it contextualizes the whole notion that Hitler came to power because “the left kept infighting” because the commies were craaazy to not like the Social Democrat when really this shit has actual causes that don’t simply reduce to temperament.

426 notes

·

View notes

Text

Known as “Freddy” to colleagues in England, as “Fritz” to friends in Berlin, but only as “our own correspondent” to readers of the Manchester Guardian, Voigt always went straight to where the story was, even if the story might imperil his life.

Within months of arriving in Germany, while covering the Ruhr miners’ uprising in Essen, he was kidnapped by rogue Reichswehr officers who accused him of being a spy, stood him against a wall and peppered the space around his head with bullets. His write-up of the incident, which named the officer who maltreated him and described the squalid conditions of other prisoners, earned him an official apology from the German chancellor.

His 1926 exclusive on a covert collaboration between the Reichswehr and the Soviet Red Army brought the German government to collapse. Other journalists would have known of the secret deal, which was common knowledge among European intelligence agencies, just as they would have known that making it public risked being sent to prison for treason in Germany. They decided not to publish. Voigt did.

Most important of all, while living through and reporting on this tumultuous and disorientating decade in European history, Voigt managed to keep a steady eye on the most important story on his patch – the rise of nazism – realising soon it wasn’t one to which he could afford to give the “both sides” treatment.

2 notes

·

View notes

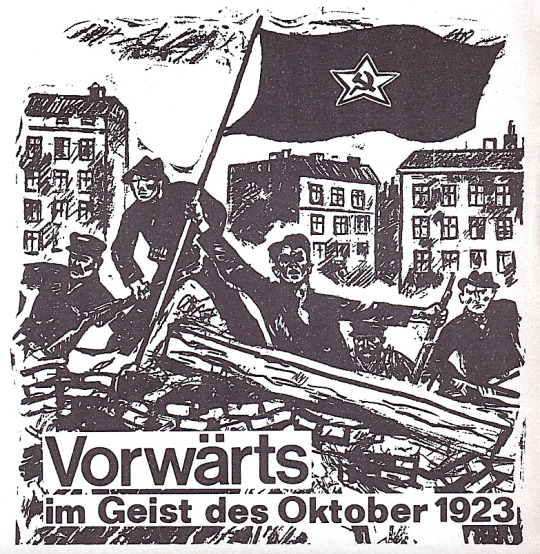

Photo

The ‘German October’

“In late July, what amounted to a wait-and-see approach was superseded by a policy of preparing for the ‘German October’. On 9 August, after the ECCI had received reports detailing the depth of the revolutionary crisis in Germany, Stalin convened a meeting of the Russian Politburo. Then, on 12 September, the Cuno government fell – and with it the policy of resisting the Franco-Belgian occupation – amidst a wave of strikes in which the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands had played a significant role. The ‘German October’ now seemed to be a real possibility, even reviving hopes of world revolution.

At the series of meetings which ensued, the Russian Politburo drew up a plan for revolution and then, in the forum provided by the ECCI, consulted the French and Czechoslovakian parties, in addition to the KPD leadership, to which Thälmann now belonged. At one of the secret sessions in late September, the French delegate, Cachin, expressed anxieties about how a de facto alliance with German nationalism in a ‘revolutionary war’ against France would impact on his party’s supporters. Trotsky’s reply was that, ‘It is too early for sleepless nights over the Ruhr. The point is to firstly take power in Germany […] everything else will derive from that’.

The Ruhr, however, was not to be to the launch pad for the ‘German October’; revolution was to be ignited using the ‘united front’ tactic in central Germany.68 According to Moscow’s plan, the KPD would enter ‘workers’ governments’ in Saxony and Thuringia. These were the locations where the party had ‘tolerated’ left SPD administrations throughout 1923, enabling the Proletarian Hundreds – which were to fight as armed units in the anticipated civil war – to operate legally at a time when they were banned by the right SPD-led Prussian government. A general strike with left SPD support would then be declared and this would signal the armed uprising.

Yet, even now, differences over tactics continued to shape the responses of the KPD leadership. During the discussions in Moscow, Thälmann expressed reservations about the revolutionary potential of Brandler’s ‘united front’ policy. He spoke against Brandler’s assessment of the influence of the left SPD and the likelihood of their supporters coming over to the side of revolution, and he questioned the value of entering regional Diets in order to procure arms. The latter was the key issue. While Brandler had stated that there were 250,000 men organised in the Proletarian Hundreds, Thälmann stressed that they were largely unarmed and, thus, militarily useless.

The success of the German revolution would, therefore, depend on Soviet intervention. In early October, shortly before his return to Hamburg, Thälmann concluded: ‘The party is not ideologically and politically prepared for the most important matter of the revolution, the civil war’.

Initially, developments proceeded without complication as the KPD entered the Saxon and Thuringian governments in mid-October. Then, on 20 October, the new Reich government under Chancellor Gustav Stresemann, which included SPD Ministers, declared a state of emergency, passed political power to the military and dispatched troops into central Germany to depose these ‘workers’ governments’. The KPD and its Soviet advisers, who had relocated to Dresden, were left to improvise a response in a fast-moving and unanticipated situation.

That evening, the leadership and its Soviet advisors resolved to use a meeting between Communist and left SPD activists, which was scheduled for the following day, ostensibly to identify the level of support for a general strike protesting the actions of the Reich government. Their actual aim was to assess the readiness of the proletariat for the German revolution. But the outcome of the so-called Chemnitz Conference’ was negative. Speaking for the SPD, the Saxon Minister of Labour, Georg Graupe, refused to countenance an immediate general strike and, instead, proposed setting up a commission of both parties to decide on what action to take. This, according to the 140 weimar communism as mass movement KPD’s leading theoretician, August Thalheimer, gave the revolution a ‘third-class funeral’.

The Hamburg Rising

Despite Thälmann’s reservations in Moscow about the prospects for a successful ‘German October’, the only attempted uprising in 1923 took place in Hamburg. It was based on an initially effective military-technical plan, especially when compared with the uncoordinated ‘March Rising’ of 1921, and took the city’s police force by surprise – despite the KPD’s public trumpeting of the coming revolution.

At 5am on 23 October, members of the party’s Ordnerdienst – the militarily-trained inner core of the Proletarian Hundreds – stormed police stations in the city’s suburbs, rapidly overpowering seventeen of twenty-six of them, in order to seize firearms. These units then took up position on rooftops, inside buildings and behind barricades. At the same time, Combat Groups (Kampfgruppen) had gone into the night with the intention of obstructing the arrival of reinforcements by blocking arterial roads and intercity railway lines, cutting telephone cables and dividing the city by occupying bridges over the river Alster. The expectation was that once the city’s working-class suburbs had been taken, the insurgents would move on the city centre in concentric circles, drawing with them wider popular support.

After returning from Moscow in early October, Thälmann’s was main role was political: he was responsibility for the agitation which aimed to bring about a mass movement.

Over the course of almost three days, the Hamburg KPD – with limited numbers of firearms and at most a few hundred insurgents – fought a losing battle against some 6000 well-armed members of the city’s police, which drew on military reinforcements, and 800 members of the SPD’s combat organisation, Republik. By the end of the uprising, more than 100 were dead, seventeen of them police officers, and several hundred more – many of them passersby – were wounded. Had the Hamburg KPD not carried out the leadership’s order to ‘retreat’, there would have been a massacre of party activists.

Although there had been significant support for the rising among the residents of Eimsbüttel, Barmbek, and Schiff bek – which marked the epicentre of events – it remained a putsch without wider support in the workforce, even in the giant shipyards. A dockers’ strike, which began on 20 October, resolved the following day to call a general strike when workers became aware that the military had been sent into central Germany, but this was stalled by the SPD-led trade union leadership in Hamburg. The KPD’s support in the local unions and the high levels of animosity towards the actions of the SPD Ministers in the Reich government had not turned into support for revolution.

Despite the more recent availability of secret communist documentation – in addition to police records and party circulars – it remains very much easier to reconstruct the specific events that took place than the internal-party dynamics that allowed them to happen. The most likely interpretation is that it grew out of a confusion of central and local party responses to a series of unanticipated circumstance. Since the fall of the Cuno government in September, the KPD had been placed on a nationwide state of readiness for the German revolution.

In early October, a political committee was set up in Wasserkante, in which Urbahns was the political leader, (probably) Gustav Faber was responsible for organisation, and Rudolf Hommes liaised with the Military-Political Directorate (Oberleitung) responsible for north-western Germany. The latter was headed by Albert Schreiner and his Soviet military advisor, General Moishe Stern. Urbahns then travelled to the Chemnitz Conference as the district’s representative. However, in the expectation that the left SPD would adopt Brandler’s call for a general strike, some twenty-five to thirty couriers were dispatched nationwide with the message that the uprising was anticipated to take place no later than Tuesday 23 October.

Hermann Remmele was the courier sent to Kiel – the port town which began the November Revolution five years before – in order to investigate reports that it offered the best prospects for widening the revolution. But he stopped in Hamburg for talks with the regional military and political leadership. Here, he was persuaded that Hamburg presented the better option and, laying too much emphasis on the likelihood of a resolution in support of a general strike in Saxony, stressed that the party must be ready to ‘launch the attack’ within ‘one or two days’. Remmele then travelled on to Kiel, where he received the telegram to postpone events.

In Hamburg, confusion reigned: the uprising was launched in the belief that that military intervention against the ‘workers’ governments’ in central Germany and the strike in the docks marked the moment to begin, and once launched, the uprising was not so easy to call off, especially after the party’s military units had gone underground.

A number of accounts attribute personal responsibility to Thälmann for this bloody fiasco, as he was the highest official present at the time the decision was taken. His motivation is explained in terms of a lust for political power: expunging the competition of party rivals, above all Hugo Urbahns. Yet, none of the documentation states more than his political involvement in events – and these were events clearly under the command of the party’s military-technical apparatus and its Soviet advisors. At a meeting of the leadership held in Berlin as the rising was still underway in Hamburg, the topic was not any breach of discipline by Thälmann and the Hamburg leadership, but rather whether some form of assistance should be given to them. The final decision, in the words of the Solomon Lozovsky, who chaired the meeting, was: ‘If one does not come to the aid of Hamburg that is not a betrayal. We sacrifice a division to save an army’.”

- Norman LaPorte, “The Rise of Ernst Thälmann and the Hamburg Left, 1921-1923.” in Weimar Communism as Mass Movement 1918–1933. Edited by Ralf Hoffrogge and Norman LaPorte. Part of the Studies in Twentieth Century Communism Series. Chadwell Heath: Lawrence & Wishart, 2017. pp. 138-142.

The image is actually from the cover of Roter Morgen, a Maoist newspaper, which published a history of the Hamburg uprising in October 1969.

#hamburg#wasserkante#kommunistische partei deutschlands#world revolution#armed uprising#deutsches oktober#hamburger aufstand#left opposition#comintern#ultraleftism#proletarian hundreds#shipyard workers#putschism#spd#weimar germany#weimar republic#communists#communism#general strike#academic quote

1 note

·

View note

Text

Top 10 Favorite places in Germany in order of which Iv seen them: 1 - Englisher Garten and Hoftgarten in Munich These gardens are one of my top favorite places in Germany because they create the feeling of being in another land outside of the city. Entering from the Hoftgarden or Court Garden, the visitor is transported to an ordered garden shaped with trimmed hedges forming spaces of grass that point toward the temple in the center. A piano plays while the view of the inner city castle is in the background. From there the English Garden comes into view with the "Harmless" statue greeting you. The motto of the park, as the first park in the continent built and dedicated to the public, is for the leisure and betterment of people to relax and mediate on their life. Designed in the style of an English Landscape Garden, clumps and belts of trees over rolling meadows form an open picturesque landscape modeled after the quality of landscape paintings. When the meadows are especially tall and then trees start to look more like an open forest than a scattering, the gardens take on a particularly enchanting feel like that in Alice and Wonderland. 2 - Riemer Park in Munich Riemer Park intrigued me for its community integration and the concept of "green fingers" that extend out into the residential areas. The community is planned with green spaces, playgrounds, and gathering spaces interwoven with impervious areas. This brings people together so that residents have places to meet each other and stormwater can be properly managed. Parking for cars is directed underground or in a parking structure near public transportation to encourage use of trains and subways instead. The area is walkable with small shops integrated with the housing developments. The park itself used to be a former airport which was completely flat, but was redesigned with "sunken gardens", continued play spaces, and an artificial hill built from the gravel excavated to create a swimming lake. The water in the lake is purified by wetlands and people can swim among fish and ducks. A planted hill overlooks the lake. 3 - Petuel Park in Munich Petuel Park was special for its goal of connecting two communities together. The green space was created by directing vehicular traffic in a tunnel underneath the park so pedestrians can access the new space. However, the effects of this improved landscape increased the price of the residential areas around it, which can lead to gentrification and an expulsion of the people the park was originally designed for. The park itself is cute and filled with little pocket spaces of varying atmospheres and activities such as playgrounds and gardens. 4 - Nymphenburg Palace in Munich The "Palace of the Nymphs" was a Baroque summer residence designed for the House of Wittelsbach when they ruled Bavaria. The castle and gardens are designed with a strong central axis that symbolizes power. A canal with symmetrical planting extends about a mile out from the castle into the landscape and visitors would approach along this walkway. This axis continues behind the castle in the garden. The garden was designed first in an Italian style, then transformed into the French style, and then later into an English garden by Sckell. Sckell did not complexly reconstruct the entire park, but rather overlaid the English garden style while preserving certain baroque elements. This is seen with the use of parterres in the design and hedges lining trees to separate the ordered gardens from the wild. However it still has a strong English garden style that can be seen with winding trails that make their way into clearings in the forest and a monopteros or Greek/Roman temple that rest in an island in a body of water. Ancient structures such as these are popular in the English garden style as they harken back to a past time. They are also beautiful, idealist features that transport you to an Arcadian landscape. This effect is created in the landscape by cutting off views to the palace and placing the monopteros so that it is visible between the trees. Artificial ruins are also used in the English style garden of palace Nymphenburg. These differ from the monopteros in that they are not built as clean, strong looking structures but are built purposefully weathered and falling apart. This is supposed to give the structure a romantic feel and mimic the passing of time to remind the viewer life is ephemeral. 5 - Castle of Benrath in Düsseldorf The pink castle, pleasure palace, of castle of Benrath is a baroque palace built for elector Karl Theordor and his wife who stayed in it all but 1 night. Painted a bubblegum pink, this palace is larger on the inside than it appear outside because it was built under fear of an uprising. The gardens of the castle of benrath follow a main axis that leads to a circular clearing with a long open channel extending in several directions. This is because the gardens were used as hunting grounds made by carving paths out of the existing forest, so that when deer wandered into the clearing they could be shot from a distance from any side. It is also another display of power over nature in the form of order and symmetry which was common of the dominant gardening style at the time. 6 - River Emscher in Dortmund The river emscher smells because it was formerly used as a open surface sewage canal. Measures have been taken to clean it up with re-wilding efforts in the 1990s after the mining and steel industries collapsed in the Ruhr region after World War II. Underground sewars are also finally being built now that the ground is more stable. Despite the smell and the unsafe quality of the water, the river emscher is becoming beautiful again due to efforts to create parks and bike routes along its path though cultural wheat fields that sparkle gold. 7 - Landshaftpak Duisburg Nord in Dortmund This is a park designed around a former steel plant after its abandonment. It is part of an effort to connect post industrial landscapes in Germany in the form of parks. It truly captures a unique atmosphere in with its enormous rusted metal structures that visitors can climb. Beautiful gardens are planted over areas with polluted soil that is sealed away with concrete. The park also highlights 4th nature, or ecological succession in a man made environment. 8 - Tiergarten Park in Berlin While Berlin has many cultural hotspots, political monuments, government buildings and embassies, and war memorials, I enjoyed the Tiergarten park because it touched many of these landscape features. The park is large and rest snugly with the Brandonberg Gate, wraps around the Victory Column, grazes the holocaust memorial, and touches both east and West Berlin. The park also has a long history. In the 1500s it was used as a hunting grounds for the elector of Brandenburg. This hunting habit shrank though as the city grew and the hunting land decreased to accommodate city growth. This soon began to transition into a forest park that connected to the city palace. Eventually in 1740, the gardens opened up to the public. In 1818, Peter Lenne transformed the baroque style gardens into a English style garden. The gardens were severely damaged in World War II, with 80-90% of the trees being destroyed. Tree donations were made to the park so it could be replanted and restored. 9 - Sanssouci Palace in Potsdam This magnificent palace was built under the French baroque style and means "without worry". It was the summer residence for Frederick the Great of Prussia among other Prussian rulers. Designed in the Rococo style, similar to the Baroque but with more delicate ornamentation, many C-shell shapes can be seen inside and outside the castle. The gardens are designed with a romantic ideal between man and nature, and both the goddess of garden fruit Pomona and the goddess of flowers Flora can be seen in the form of statues. Grapes were grown in the terraced vineyards behind the palace and many exotic fruits were grown in the greenhouse that would he served to guests as a surprise. Frederick had wanted both art and nature to be united, so he wanted both practical fruit gardens and ornamental flower gardens. Aside from being one of the most beautiful estates I had seen here, it also encompassed a variety of different styles since it was remodeled under various successors. It the gardens it includes a Chinese temple, a Roman bathhouse, and fake ruins that gives visitors the romantic illusion of "the passing of time". Many statues of Greek gods and goddesses such as Apollo god of art and Venus goddess of love can be found indoors and outdoors to enhance the feeling of carefree playfulness and mystique. Because Frederick was considered an enlightened authoritarian ruler, his palace was built with a marble thinking study that he would invite famous philosophers to do that he could receive their opinions. 10 - International Garden Exhibition in Keinbergpark in Berlin With the motto "an ocean of colors", the IGA in Berlin this year revitalized an underused green space and is bringing millions of visitors to the new space. International landscape architects and designers have collaborated to create different parklets with water features, urban designs, and traditional gardens. The "Gardens Around the World" showcase traditional gardens from countries such as Japan, Korea, and Middle Eastern countries. The park also showcases a plant exhibit, a bobsled ride, and an air gondola that transports users from one part of the park to another. In the end, while I saw many places in Germany that I loved, I am also aware I missed more than I got to see. After this first trip to Europe, I would definitely come back here again.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Standing on the sidewalk doesn’t work

I got into an argument today, after hearing that the official white house website, less than 24 hours after the inauguration of Donald Trump, shut down the following pages: LGBT, Equal Pay, Women in STEM, Health Care, and Civil Rights. They also disabled petitions from WeThePeople, one of the largest petition sites we have. I pointed out that five states have already passed laws attempting to criminalize and/or discourage disruptive protests. My opponent informed me that such people should be thrown in jail for disrupting her daily life with their grievances. I could not believe my ears. First of all, the issues that are being protested are worthy goals - preserving our civil rights and our environment. Second of all, non-disruptive protest can be effective sometimes, but with as far gone as we are right now, standing on the sidewalk with our signs isn’t going to work. We need to block roadways, to strike, to disrupt everyone’s precious routine. If you let them take away that right, then next they’re going to take away our right to stand on the sidewalk. And they will slowly but surely begin to chip away at our liberties until we have none left and we wonder what has happened to them. We have a right to demand redress from those in power, and to raise our voices when they are not being heard. We have a responsibility to all of humanity to make sure that we stand up for what is right, no matter what. We will fight, and yes, we will disrupt your silly little routines to preserve our planet and our rights. You think our fight is petty, you think it’s whiners and crybabies who don’t know what the real world is, pick up a goddamned history book and educate yourself.

Some examples:

As one of the four mounted heralds of the Suffrage Parade on March 3, 1913, lawyer Inez Milholland Boissevain led a procession of more than 5,000 marchers down Washington D.C.'s Pennsylvania Avenue. The National American Woman Suffrage Association raised more than $14,000 to fund the event that became one of the most important moments in the struggle to grant women the right to vote — a right that was finally achieved seven years later.

As a nascent union, the United Auto Workers, formed in 1935, had a lot to fight for. During the Depression, General Motors executives started shifting work loads to plants with non-union members, crippling the UAW. So in December 1936, workers held a sit-in at the Fisher Body Plant in Flint, Michigan. Within two weeks, about 135,000 men were striking in 35 cities across the nation. Although the sit-ins were followed by riots, the images of bands playing on assembly lines and men sleeping near shuttered machines recall the serene strength behind the movement that solidified one of North America's largest unions.

Even though African Americans constituted some 70% of total bus ridership in Montgomery, Ala., Rosa Parks still had trouble keeping her seat on Dec. 1, 1955. It was against the law for her to refuse to give up her seat to a white man, and her subsequent arrest incited the Montgomery Bus Boycott. One year later, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court's decision that made segregated seating unconstitutional. Parks was known thereafter as the "mother of the civil-rights movement."

After the death of pro-democracy leader Hu Yaobang in mid-1989, students began gathering in Beijing's Tiananmen Square to mourn his passing. Over the course of seven weeks, people from all walks of life joined the group to protest for greater freedom. The Chinese government deployed military tanks on June 4 to squelch the growing demonstration and randomly shot into the crowds, killing more than 200 people. One lone, defiant man walked onto the road and stood directly in front of the line of tanks, weaving from side to side to block the tanks and even climbing on top of the first tank at one point in an attempt to get inside. The man's identity remains a mystery. Some say he was killed; others believe him to be in hiding in Taiwan.

494 B.C. -- The plebeians of Rome withdrew from the city and refused to work for days in order to correct grievances they had against the Roman consuls.

1765-1775 A.D. -- The American colonists mounted three major nonviolent resistance campaigns against British rule (against the Stamp Acts of 1765, the Townsend Acts of 1767, and the Coercive Acts of 1774) resulting in de facto independence for nine colonies by 1775.

1850-1867 -- Hungarian nationalists, led by Francis Deak, engaged in nonviolent resistance to Austrian rule, eventually regaining self-governance for Hungary as part of an Austro-Hungarian federation.

1905-1906 -- In Russia, peasants, workers, students, and the intelligentsia engaged in major strikes and other forms of nonviolent action, forcing the Czar to accept the creation of an elected legislature.

1917 -- The February 1917 Russian Revolution, despite some limited violence, was also predominantly nonviolent and led to the collapse of the czarist system.

1913-1919 -- Nonviolent demonstrations for woman's suffrage in the United States led to the passage and ratification of the Constitutional amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote.

1920 -- An attempted coup d'etat, led by Wolfgang Kapp against the Weimar Republic of Germany failed when the population went on a general strike, refusing to give its consent and cooperation to the new government.

1923 -- Despite severe repression, Germans resisted the French and Belgian occupation of the Ruhr, making the occupation so costly politically and economically that the French and Belgian forces finally withdrew.

1920s-1947 -- The Indian independence movement led by Mohandas Gandhi is one of the best known examples of nonviolent struggle.

1933-45 -- Throughout World War II, there were a series of small and usually isolated groups that used nonviolent techniques against the Nazis successfully. These groups include the White Rose and the Rosenstrasse Resistance.

1940-43 -- During World War II, after the invasion of the Wehrmacht, the Danish government adopted a policy of official cooperation (and unofficial obstruction) which they called "negotiation under protest." Embraced by many Danes, the unofficial resistance included slow production, emphatic celebration of Danish culture and history, and bureaucratic quagmires.

1940-45 -- During World War II, Norwegian civil disobedience included preventing the Nazification of Norway's educational system, distributing of illegal newspapers, and maintaining social distance(an "ice front") from the German soldiers.

1940-45 -- Nonviolent action to save Jews from the Holocaust in Berlin, Bulgaria, Denmark, Le Chambon, France and elsewhere.

1944 -- Two Central American dictators, Maximiliano Hernandez Martinez (El Salvador) and Jorge Ubico (Guatemala), were ousted as a result of nonviolent civilian insurrections.

1953 -- A wave of strikes in Soviet prison labor camps led to improvements in living conditions of political prisoners.

1955-1968 -- Using a variety of nonviolent methods, including bus boycotts, economic boycotts, massive demonstrations, marches, sit-ins, and freedom rides, the U.S. civil rights movement won passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

1968-69 -- Nonviolent resistance to the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia enabled the Dubcek regime to stay in power for eight months, far longer than would have been possible with military resistance.

1970s and 80s -- The anti-nuclear power movements in the US had campaigns against the start-up of various nuclear power plants across the US, including Diablo Canyon in Central California.

1986-94 -- US activists resist the forced relocation of over 10,000 traditional Navajo people living in Northeastern Arizona, using the Genocide Demands, where they called for the prosecution of all those responsible for the relocation for the crime of genocide.

1986 -- The Philippines "people power" movement brought down the oppressive Marcos dictatorship.

1989 -- The nonviolent struggles to end the Communist dictatorships in Czechoslovakia in 1989 and in East Germany, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in 1991.

1989 -- The Solidarity struggle in Poland, which began in 1980 with strikes to support the demand of a legal free trade union, and concluded in 1989 with the end of the Polish Communist regime.

1989 -- Nonviolent struggles led to the end of the Communist dictatorships in Czechoslovakia in 1989 and in East Germany, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in 1991.

1990 -- The nonviolent protests and mass resistance against the Apartheid policies in South Africa, including a massive international divestment movement, especially between 1950 and 1990, brings Apartheid down in 1990. Nelson Mandela, African National Congress leader, is elected President of South Africa in 1994 after spending 27 years in prison for sedition.

1991 -- The noncooperation and defiance defeated the Soviet “hard-line” coup d'état in Moscow.

1996 -- The movement to oust Serbia dictator Slobodan Milosevic, which began in November 1996 with Serbs conducting daily parades and protests in Belgrade and other cities. At that time, however, Serb democrats lacked a strategy to press on the struggle and failed to launch a campaign to bring down the Milosovic dictatorship. In early October 2000, the Otpor (Resistance) movement and other democrats rose up again against Milosevic in a carefully planned nonviolent struggle.

1999 to Present -- Popular protests of corporate power & globalization begin with Seattle WTO protest in Seattle, 1999. This is what set the trend for the Occupy movement which is still alive.

2001 -- The “People Power Two” campaign, ousts Filipino President Estrada in early 2001.

2004-05 -- The Ukranian people take back their democracy with the Orange revolution.

2010 to Present -- Arab Spring nonviolent uprisings result in the ouster of dictatorships in Tunisia and Egypt and ongoing struggles in Syria and other Middle Eastern countries.

And if you’re curious how Trumps rise to power parallels that of Adolf Hitler and the rise of fascism in Germany, please see the following links:

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/dec/01/comparing-fascism-donald-trump-historians-trumpism

http://www.alternet.org/election-2016/paul-krugman-uncovers-chilling-parallels-among-trump-fascism-and-fall-roman-republic

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/a-scholar-of-fascism-sees-a-lot-thats-familiar-with-trump

any more questions?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not Weimar America, But Dark Times All the Same

There’s a scene in Christopher Isherwood’s novel Goodbye to Berlin where the author goes to visit Bernhard Landauer, the owner of a prosperous department store in Germany. The year is 1933 and Bernhard shows Christopher a vicious message he’s received, threatening to kill him and all his fellow Jews. Bernhard shrugs this off but Christopher insists he go to the police: “The Nazis may write like schoolboys,” he says, “but they’re capable of anything. That’s why they’re so dangerous. People laugh at them, right up to the last moment…”

Here in America, it’s been easy to laugh at those who have threatened political violence over the past four years, and even at those who have carried it out. Their rogue’s gallery can look like something out of a campy video game: ninja-like black masks who run through the streets LARPing revolution? Mostly white college students screaming “black lives matter”? I still haven’t figured out exactly what a boogaloo boy is supposed to be. Even after the horror in Charlottesville, the white supremacists yodeling about “the Jew” on their way back from the latest Wolves of Vinland potluck come off as more sad than dangerous. It’s easy to laugh at these people, to dismiss them as dorks and thumbsuckers; it’s easy to laugh until it isn’t, until your cities are burning, until you look down and realize you’ve been dancing on a volcano.

So it’s gone in America today. Our fraught and volatile political climate has even led some to compare us to the Weimar Republic that Isherwood was chronicling. The term “Weimar America” has come into usage, popularized by writers like TAC‘s own Rod Dreher. Just as in pre-Nazi Germany, these thinkers say, America’s streets are now roiled by unrest perpetrated by extremists who have no respect for mediating institutions and view violence as just another necessary means of political expression. The left is mostly responsible for this chaos, though the right has also gotten involved, at Charlottesville, in Kenosha and Minneapolis, and in Portland where rioters shot and killed a Trump supporter last weekend. There are other similarities too: hedonism, decadent elites, the so-called center falling away.

Certainly illiberal left-wing militants clashing with illiberal right-wing militants is a portent right out of the 1930s. And certainly, too, as Michael Davis has pointed out, if society’s traditional elements feel threatened by bullies, they’re more likely to unite behind a bully of their own, a Hitler or a Franco. There are also parallels between America and Weimar at the ideological level. One of the aptest descriptions of Weimar, attributable to the academic Finlay McKichan, is that it was “a republic nobody wanted”—and since its ideologues didn’t want it, they didn’t hesitate to look beyond it, to dream of an abstract and supposedly stronger polity. Likewise have some American thinkers come to see their own republic as indefensible and sickly. On the left, this strand has existed for decades, mostly among Marxists who see the United States as too capitalist and imperialist. On the right, it can be found among the postliberals, who view our Enlightenment roots as withered and who, at their edges at least, long for a monarchy or a Catholic integralist state.

These schools are on the rise among intellectuals, but they’re also hardly representative of America today. Outside of the ivory tower and Twitter, few Americans deplore their founding or want to see their nation radically overhauled. The recent Democratic and Republican conventions, star-spangled affairs in their own ways, were evidence enough of that. Contrast that to the Weimar Republic, whose very formation was opposed by powerful societal factions (including the military). Demonstrating the lack of public buy-in, before the Weimar constitution was even signed, Bavaria broke away and formed its own socialist state. Two years later, right-wing forces under Wolfgang Kapp briefly overthrew the government; three years after that, Hitler tried something similar in Munich with the Beer Hall Putsch.

In Goodbye to Berlin, Bernhard says to the author, who is English, “You, Christopher, with your centuries of Anglo-Saxon freedom behind you, with your Magna Carta engraved upon your heart, cannot understand that we poor barbarians need the stiffness of a uniform to keep us standing upright.” That might seem like an amusing observation today, given the paltry state of the German military, but it also gets at an important truth about the British and their American cousins. Even if we now seem to be coming apart, even if our Overton Window is widening, we have centuries of liberal democratic practice behind us, civic traditions and attitudes that can’t just be rolled up like a carpet. These have weathered chaos before and may yet again. They’re at least still sticky enough that even in these frenzied times, we don’t have rogue bands of Freikorps roving the streets, frequent uprisings by communists, regular assassinations of politicians.

One reason for this is yet another important distinction between America and Weimar Germany: we are not an economic basket case. Though it briefly stabilized during the mid-1920s, Weimar was for much of its existence plagued by unemployment, as well as hyperinflation, which debauched the Reichsmark. This was a result of both war debt and promiscuous money printing by the government, which under the Treaty of Versailles owed steep reparations to its former World War I enemies. This economic debilitation became intertwined with civic grievance: the treaty was viewed as a national humiliation, and all the more so after Germany defaulted on its payments and French and Belgian troops occupied its industrialized Ruhr region as punishment. Such deprivation and wounded pride further discredited the government and drove people to the margins, as they sought sweeping answers to sweeping problems. The result was a political scene that, by the early 1930s, was dominated by Nazis and communists.

America, needless to say, has nothing that even approaches this. Our economy is bleeding at the moment thanks to coronavirus restrictions, but it doesn’t compare to Weimar’s protracted woes, and while our national debt is a disgrace, there is no hyperinflation to speak of, at least not yet. We will have to deal with all this eventually, of course, and rehabilitating our economic fundamentals ought to be a priority once the coronavirus recedes. Cannonball a full-scale and long-term economic meltdown into our current political waters and you could very well set off a tidal wave. But right now, all things considered, I would respectfully disagree with the Weimar America characterization. The differences are too stark, and given the potency of the metaphor, that ought to matter.

But if we’re not Weimar, then what are we? One of my favorite books about the Civil War is This Hallowed Ground by Bruce Catton. Published in 1955, it begins in the year 1856 with the Bleeding Kansas crisis and the caning of Senator Charles Sumner by Congressman Preston Brooks. Catton writes:

Angry words were about the only kind anyone cared to use these days. Men seemed tired of the reasoning process. Instead of trying to convert one’s opponents it was simpler just to denounce them, no matter what unmeasured denunciation might lead to. …He had not been trying to persuade. No one was these days; a political leader addressed his own following, not the opposition. Sumner had been trying to inflame, to arouse, to confirm the hatreds and angers that already existed.

We may not be Weimar, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t dark clouds gathering on our horizon.

The post Not Weimar America, But Dark Times All the Same appeared first on The American Conservative.

0 notes

Text

Nazi Politics (Part 2): WW1 and the Aftermath

In August 1914, cheering crowds gathered in the town squares to celebrate the outbreak of war. The Kaiser declared that he recognized no parties, only Germans. The spirit of 1914 became a symbol of national unity - just as Otto Bismarck was a nostalgia point for a strong, decisive political leader. But Germany lost the war.

The peace terms were no worse than Germany had planned to impose on others, but they were extremely harsh. Huge financial reparations were demanded for Germany’s occupation of Belgium & northern France (it would have taken until 1980 to pay); the navy & air force were disbanded; the army was restricted to 100,000 men; all modern weapons (such as tanks) were banned; territory was lost to France and Poland.

The war destroyed the international economy, and it took three decades to recover. International economic co-operation was impossible, because of the national economic egotism of the new Eastern European states.

Germany had paid for the war by printing money: they had planned to back it by annexing French & Belgian industrial areas. Now they couldn’t meet the reparations without raising taxes - and no government would do that, because their opponents would have accused them of taxing the Germans to pay the French. So the government began printing money again.

This, of course, led to inflation. Huge inflation. Reparations had to be paid in gold and goods, and at this rate of inflation, they would never manage it.

In January 1923, French & Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr, and began to seize industrial assets & products. In response, the German government announced a policy of non-cooperation. This caused a rapid drop in the mark against the dollar. By December, one American dollar was worth 4 million million marks. If it kept on, Germany would suffer a total economic collapse.

But the inflation was stopped. A new currency was introduced. Passive resistance to the Ruhr occupation ended, and the troops withdrew. Payment of reparations resumed.

But the inflation had fragmented the middle classes, and no political party was able to unite them. There were huge job losses because of the economic re-shuffle: from 1924 onwards, millions of people were unemployed. Businesses resented the government’s failure to help, and began to look for alternatives.

For the middle classes, the inflation had increased the cultural & moral disorientation they were already suffering. The “excesses” of modern culture in the 1920′s made it worse - jazz & cabaret in Berlin; abstract art; atonal music; experimental literature.

There was political disorientation, too. The Second Reich had collapsed and the Kaiser fled into exile. In November 1918, the Weimar Republic had been created. It had a modern constitution, female suffrage and proper representation.

But Article 48 of the constitution gave the independently-elected President wide-ranging emergency powers to rule by decree. The first President was Friedrich Ebert (a Social Democrat), and he used Article 48 extensively. His successor was F-M Paul von Hindenburg - he was a strong monarchist with no strong commitment to the constitution. He also used Article 48 extensively - and he contributed to the Republic’s downfall.

After WW1, a culture of political violence developed. The Steel Helmets were radical right-wing veterans. Younger men, too young to fight in the war, tried to live up to the heroic deeds of the veterans by fighting at home.

The war had caused major political polarization. Communist revolutionaries were on the left; many radical groups emerged on the right. The Free Corps were right-wing armed bands, used by the government to put down Communist & far-left uprisings in Berlin and Munich (1918-19). In 1920, the Free Corps attempted a coup d’état in Berlin, which led to a far-left armed uprising in the Ruhr. In 1923, there were more left- & right-wing uprisings

1924-29 were relatively stable, but even so, at least 170 political paramilitary members were killed in street fighting. In the early 1930′s, injuries & the death rate increased sharply - 300 were killed in March-March 1930-31. Political tolerance was gone, replaced by violent extremism.

During the mid-1920′s, moderate-centre & liberal-left parties lost huge numbers of votes. The threat of Communist revolution dropped, and the middle classes moved further & further right-wing. Parties supporting the Weimar Republic never had a parliamentary majority after 1920.

The Republic was also undermined by the justice system, who were biased in favour of right-wing assassins & insurgents who claimed patriotic reasons for their violence; and by the army, who remained neutral, but became more & more resentful at the Republic’s failure to repudiate the Versailles restrictions.

German democracy hadn’t been doomed from the beginning. But the 1920′s made sure that it had no chance to establish a secure footing.

#book: the third reich in power#history#military history#ww1#occupation of the ruhr (1923)#germany#nazi germany#weimar republic#france#belgium#wilhelm ii#otto von bismarck#friedrich ebert#paul von hindenburg#steel helmets#free corps#treaty of versailles#communism

0 notes

Photo

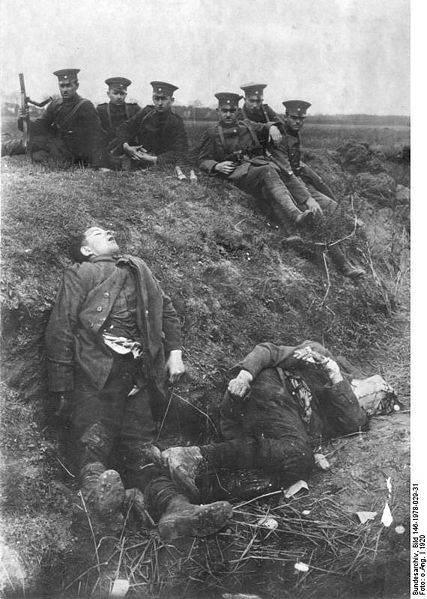

Ruhr Battle (1930) by Barthel Gilles

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

4 notes

·

View notes