#peter lorre magazine

Text

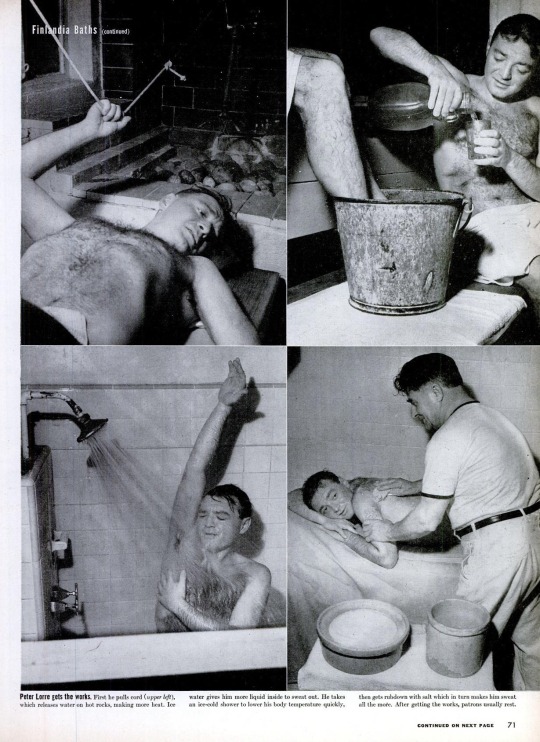

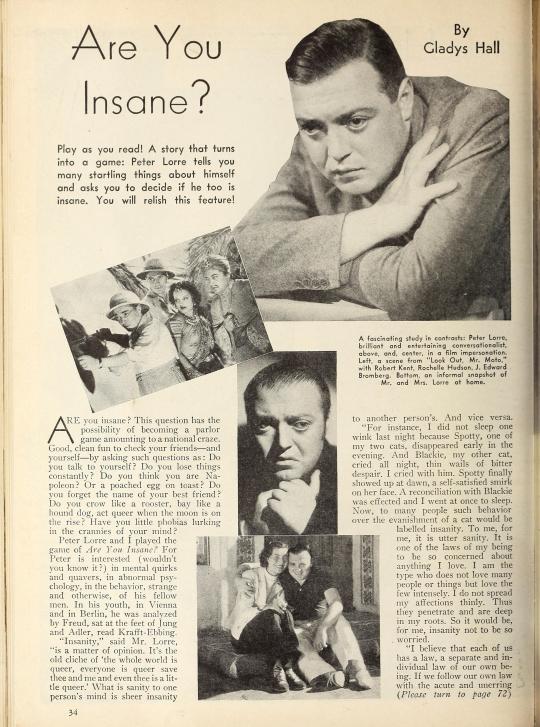

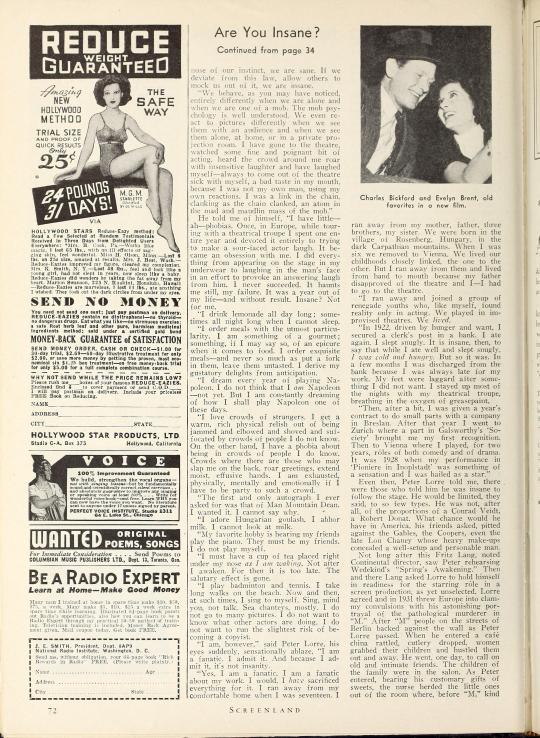

Peter Lorre: "Are You Insane?" [Article]

"I am a fanatic," said Peter Lorre, his eyes suddenly sensationally ablaze. "I admit it…I am a fanatic about my work. I would, I have sacrificed everything for it."

I can see those eyes, hear his voice. Oh, Gladys, you lucky interviewer! Here’s the fun, multi-paged read from the January 1938 edition of Screenland magazine:

"He did not want to put on the garb of the pathological horror man and never take it off."

"I take long walks on the beach. Now and then, at such times, I sing to myself…Sea shanties, mostly."

Download here to spare your eyeballs:

Peter Lorre Are You Insane Page 1

Peter Lorre Are You Insane Page 2

Peter Lorre Are You Insane Page 3

Screenplay Table of Contents - January 1938

#peter lorre#long walks on the beach#sea shanties#love this man#and stop calling him a horror actor#peter lorre article#peter lorre magazine

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review: Casablanca

The film has a peculiar magic to it, and because of its pace the richness of its sense of detail often goes unnoticed.

by Jeremiah Kipp

December 13, 2008

Photo: Film Forum

y the time we arrive at Rick’s Café Américain, a certain paranoia and vivacity has been set—and then comes romance, in the form of piano player Sam (Dooley Wilson) and his rendition of “It Had to Be You” as the camera makes a slow dolly toward him through the bustling crowd and wafts of cigarette smoke. It’s easy to fall into the rhythms of Casablanca, long before the appearance of the star-crossed lovers and their damaged idealism, or most of the great character actors who populate the world of Michael Curtiz’s film make their presence felt—such as Sydney Greenstreet’s bemusedly sinister Signor Ferrari and Peter Lorre’s nervously sweaty Ugarte.

The film has a peculiar magic to it, and because of its pace the richness of its sense of detail often goes unnoticed. Audiences make generalizations about Casablanca because of how all those little particulars add up. Film lovers discuss it with a starry look in their eyes, as if they were describing their first kiss or a lost love, because something in the film touches them, perhaps its theme of dignity and decency, of rediscovered idealism. Men seem almost instinctively drawn to Humphrey Bogart’s Rick because he’s a man of integrity, while women seem to dig him because he’s a man of mystery.

There’s also something else to Rick, and it’s visible in his hangdog face. When we first see him he’s playing chess by himself, and the light picks up on a small glimmer of spittle on his lips. Bogart was always a sputtering actor, which made him so great as a B-movie villain cowering for his life before getting shot to death by the hero. But his sudden stardom revealed something incredibly human, and as such relatable, about him. He seemed more like a real man than, say, the frequently idealized characters played by Errol Flynn. The fact that Bogart was a movie star says a lot about his particular charisma—the kind that’s earned by an actor who’s paid his dues and figured out who he is. Rick is his own man, and like those refugees at the start of the film who watch a plane fly above Casablanca, his life experience is written on his face.

Rick is first seen with his back turned to a local who’s had too much to drink. “Rick, where were you last night?” the man says, to which Rick replies, “That was so long ago, I don’t remember.” Even though there’s no overt sex in Casablanca, it’s constantly implied. When Rick orders his bartender to take a girl home in a cab, he asks him to come right back. In the scenes between Rick and Captain Renaud (Claude Rains), the men talk about women as if they were baubles to be admired, then dropped. Renaud also fawns over his friend with the most extravagant, slightly ironic hero-worship, and in a classic line from the film, Rains’s classy, debonair captain tells Ingrid Bergman’s Ilsa Lund that if he were a woman, he’d also be in love with Rick.

It’s astonishing when Bergman materializes some 30 minutes into the film, after Ugarte has whimpered for his life and been shot dead, and Rick has proclaimed that he “sticks his neck out for no one” and came to Casablanca “for the waters.” The shot that first captures the glamorous Bergman doesn’t call attention to itself, or highlight her in the frame, and yet we can’t take our eyes off her. It’s strange, because the shot is very wide, the dress she wears is plain, and she looks nervous and hesitant. How can a woman be so luminous when she’s moving her face back and forth like a deer transfixed by car headlights? When the audience finally sees Ila in close-up, sitting at a table in Rick’s Café with her husband, Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid), her face is somewhat round, her eyes are sharp, and her voice has a certain breathless quality. Bergman, like Bogart, captivates us because of that ineffable thing we call presence. In this moment, the audience instantly understands Rick and Ilsa through the actors’ faces.

If audiences are to admire Rick and Bogart, then we’re meant to adore Ilsa and Bergman. Victor is set up as a great freedom fighter, yet he feels more like an abstract idea or plot point, not unlike the letters of transit that allow people safe passage out of Casablanca. Ilsa, like Rick, is a full person, with vulnerability in her eyes and a magnetism to her presence that goes beyond gauzy lenses and classical three-point lighting. Naturally they’re drawn to one another. She has a lot of big moments in the film, but a lot of small ones too that are just as memorable, such as that tiny, mischievous gleam in her eyes when she asks Sam to play some of the old songs.

There are, of course, the close-ups of Rick and Ilsa when they see each other for the first time as Sam plays “As Time Goes By,” but there’s also the furtive glances that they throw at one another before their eyes flicker back to the table, as they sit chatting about precedents being broken with Victor and Renaud. Casablanca is about striving for something meaningful. But it’s also a tale of sacrifice in the name of greater good, set in a world of shadows, booze, cigarette smoke, and memories. The love story at its center of allows heroes to tap into something special within themselves, and if they lost it in Paris, somehow they got it back in Casablanca. The film is all of those things at once, but it’s also about these people, these faces, and all the little moments between them. It reminds us that when we’re in relationships, we learn more about who we are reflected in others, and when we go to the movies, the great ones can do the same thing.

Score:

Cast: Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, Peter Lorre, Dooley Wilson Director: Michael Curtiz Screenwriter: Julius J. Epstein, Philip G. Epstein, Howard Koch Distributor: Warner Bros. Running Time: 102 min Rating: NR Year: 1942 Buy: Video, Soundtrack

#Humphrey Bogart#Ingrid Bergman#Paul Henreid#Claude Rains#Conrad Veidt#Sydney Greenstreet#Peter Lorre#Dooley Wilson#Michael Curtiz#Michael Curtiz Screenwriter: Julius J. Epstein#Philip G. Epstein#Howard Koch#Warner Bros.#Jeremiah Kipp#Casablanca#Slant Magazine

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Actors including Katharine Hepburn, Tallulah Bankhead and Peter Lorre discuss strategy at the home of Lawrence Tibbett. From an August 21, 1939 LIFE magazine article about a threatened AF of L strike.

(source: LIFE archives)

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

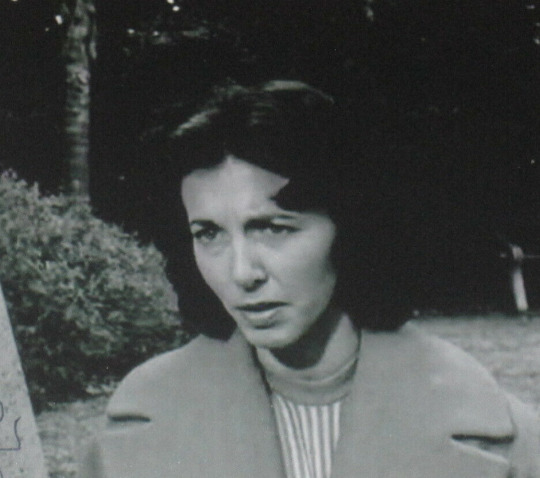

My next door neighbor appeared in nearly nine thousand old time radio shows in the late 1930s, the 1940s, and the 1950s.

According to a 1946 issue of Time Magazine, she had already appeared in almost three thousand different radio shows by 1946.

She was a regular on programs like The Whistler, Escape, Sam Spade, the Phil Harris - Alice Fay Show, the Alan Young Show, Phillip Marlowe, and Suspense. She starred with Peter Lorre in a radio series called Mystery in the Air. She was in most episodes of the Harold Lloyd Comedy Theater. And she was in the original radio pilot of Dragnet. She did well over one hundred shows just for Jack Webb alone.

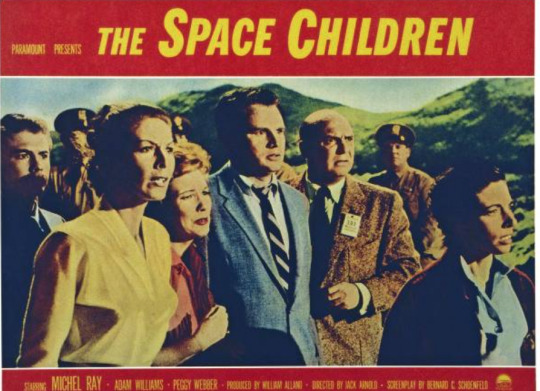

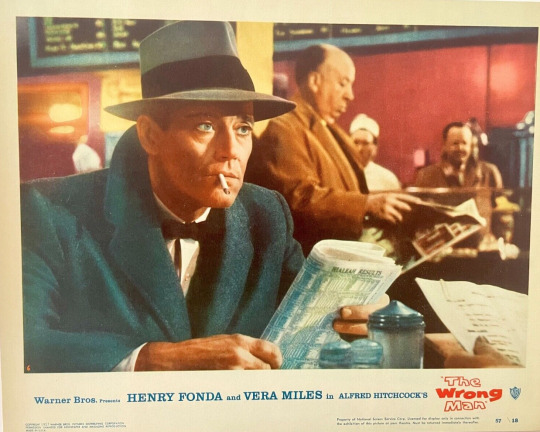

In the movies she appeared with Orson Welles in Macbeth (1948), acted alongside Henry Fonda in Alfred Hitchcock's The Wrong Man (1956), and she starred in two campy monster movies: The Space Children (1958) and the Screaming Skull (1958).

She knew and worked with Lauren Bacall, Humphrey Bogart, Errol Flynn, Vincent Price, Charlie Chaplin, Lionel Barrymore, Lew Ayres, Basil Rathbone, Nigel Bruce, Kirk Douglas, Henry Fonda, Arch Oboler, Carlton E. Morse, Norman Corwin, Rod Serling, and Jim Backus to name a few.

She started in television before it even existed - way back in 1939 - acting regularly on the experimental station located above the Hollywood sign: Station W6XAO.

She is still alive and doing well. By random coincidence, I happen to live right beside her in Hollywood. We hang out all the time.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

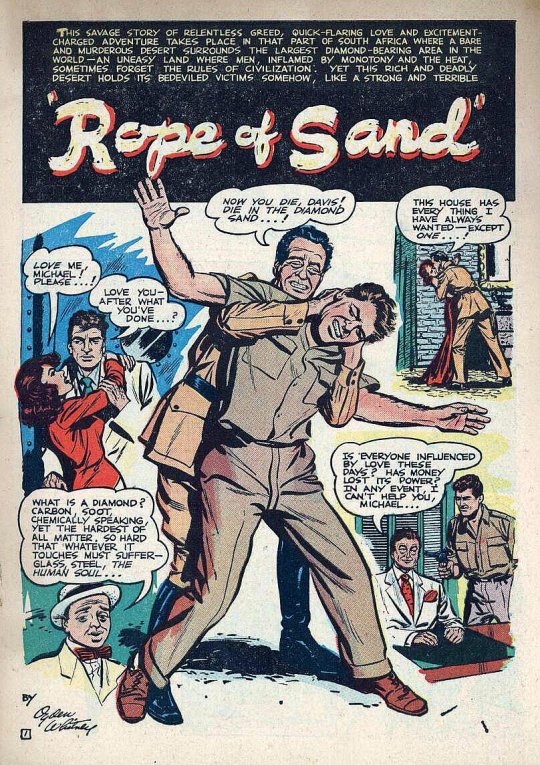

First page from Movies Thrillers # 1 (and only) from Magazine Enterprises, 1949. Adapting the film Rope of Sand. Which was about blood diamonds.

Art by Ogden Whitney

Nice quote from the Peter Lorre character.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

FNF Donation Drive giveaway!

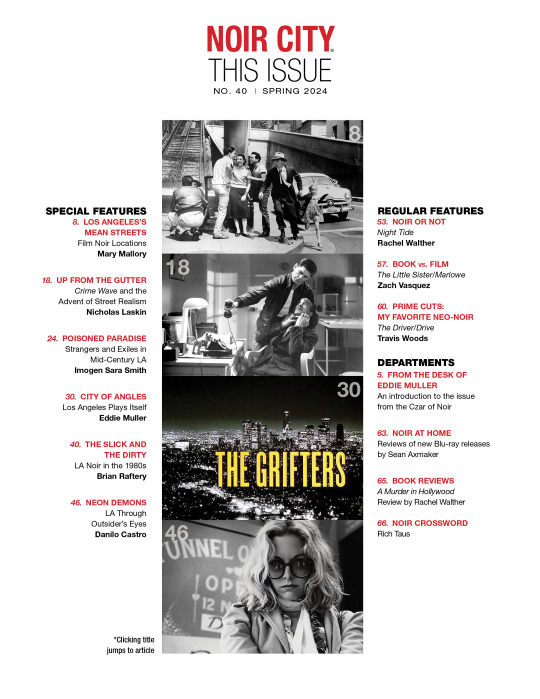

For a chance to win five NOIR CITY Magazine digital back issues — #2, #16, #19, #24, #25 — sent via WeTransfer file transfer service to your email address, donate $20 or more to the FNF between now and May 3. Your name will be entered in a random drawing. Three winners will receive the issues.

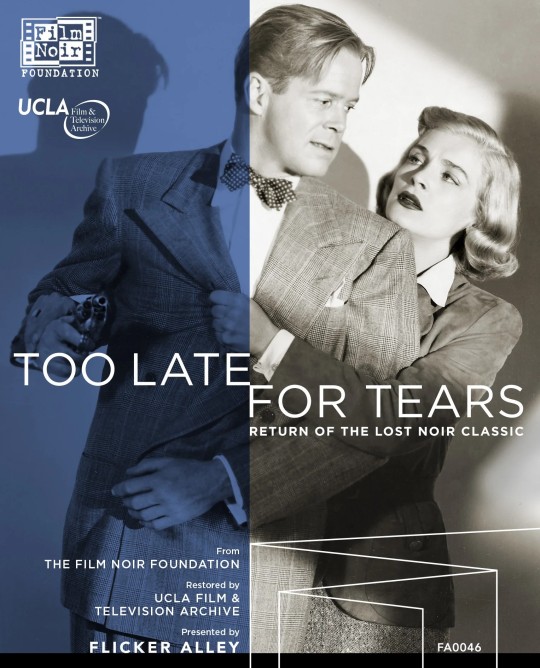

And, for a donation of $50 or more, a winner in a random drawing will receive Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray/DVD releases of two FNF restorations — Too Late for Tears (1949) with Lizabeth Scott and Dan Duryea and Trapped with Lloyd Bridges and Barbara Payton. Special features produced by the FNF included on each Blu-ray/DVD.

All winners will be announced Monday, May 6, on the FNF's news page.

Everyone who donates $20 or more and signs up on our e-mail list, will automatically receive the digital version of NOIR CITY e-magazine for a year! The current issue, our 40th, is concerned exclusively with Los Angeles. We explore the city in the classic noir era and in neo-noir films from the 1960s right up to today. It's a deep dive into cold, dark waters.

Your donations help the FNF locate, restore, and exhibit films that, without our intervention, would be lost forever.

Already a NOIR CITY subscriber? We have drawings for you too!

For $20 donations: three winners in random drawings will receive five NOIR CITY Magazine digital back issues— #2, #16, #19, #24, #25— sent via WeTransfer file transfer service to their email addresses. Two separate $20 donors will receive either the Criterion release DVD of Mulholland Drive (2001) or the FNF restoration Blu-ray/DVD of Too Late for Tears (1949).

For $65 donations: one winner in a random drawing will the Criterion release Blu-ray of Devil in a Blue Dress (1995) starring Denzel Washington, Stranger on the Third Floor (1940) with Peter Lorre, a copy of Eddie Muller’s Gun Crazy: The Origin of American Outlaw Cinema, and illustrator Graham Chaffee’s To Have and To Hold from Fantagraphics.

For $120 donations, continuing the Los Angeles theme, one winner in a random drawing will receive a Blu-ray of Harper (1966) starring Paul Newman; a DVD of The Grifters (1990) with Angelica Huston, John Cusack, and Annette Bening; and the Criterion Blu-ray release of Double Indemnity (1944). We’ll also include an FNF copy (opened) of Cutter’s Way (1981) on a double bill with the non-LA/non-noir Chilly Scenes of Winter (1979) with Gloria Grahame.

For a shot at any of these goods, make your donation to the FNF between now and May 1. Your name will be entered into the random drawings for your donation amount. All winners will be announced on Monday, May 6, on the FNF’s news page.

#film noir foundation#noir city magazine#film restoration#trapped#mulholland drive#eddie muller#too late for tears#los angeles#los angeles noir

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

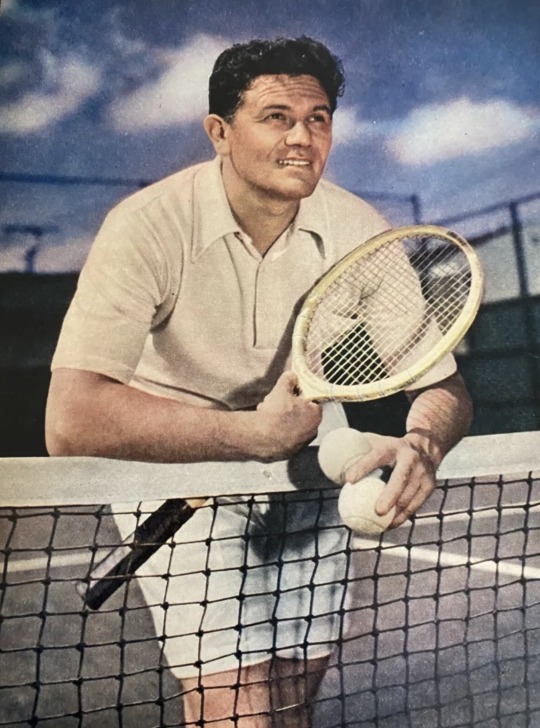

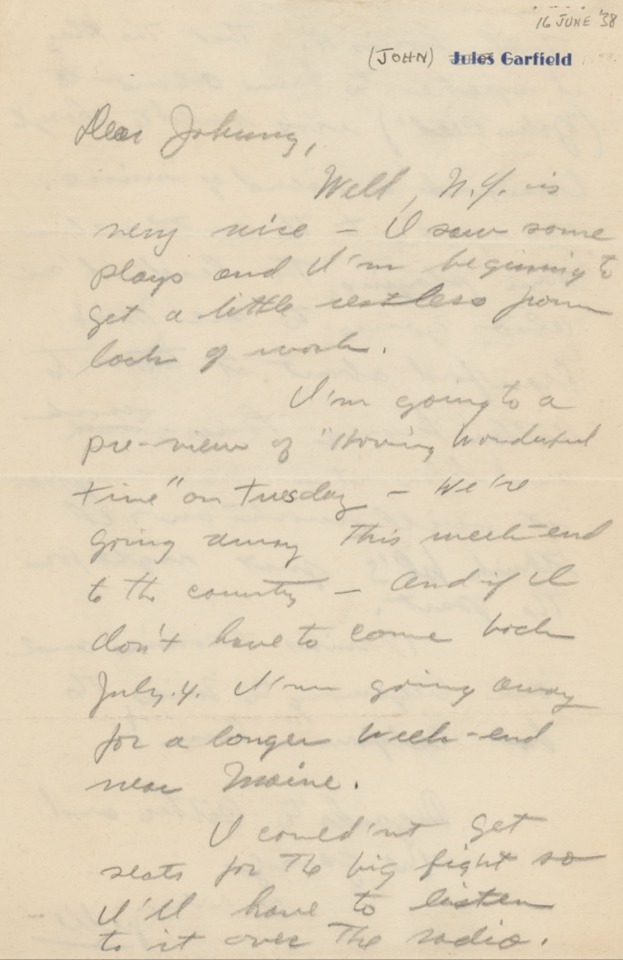

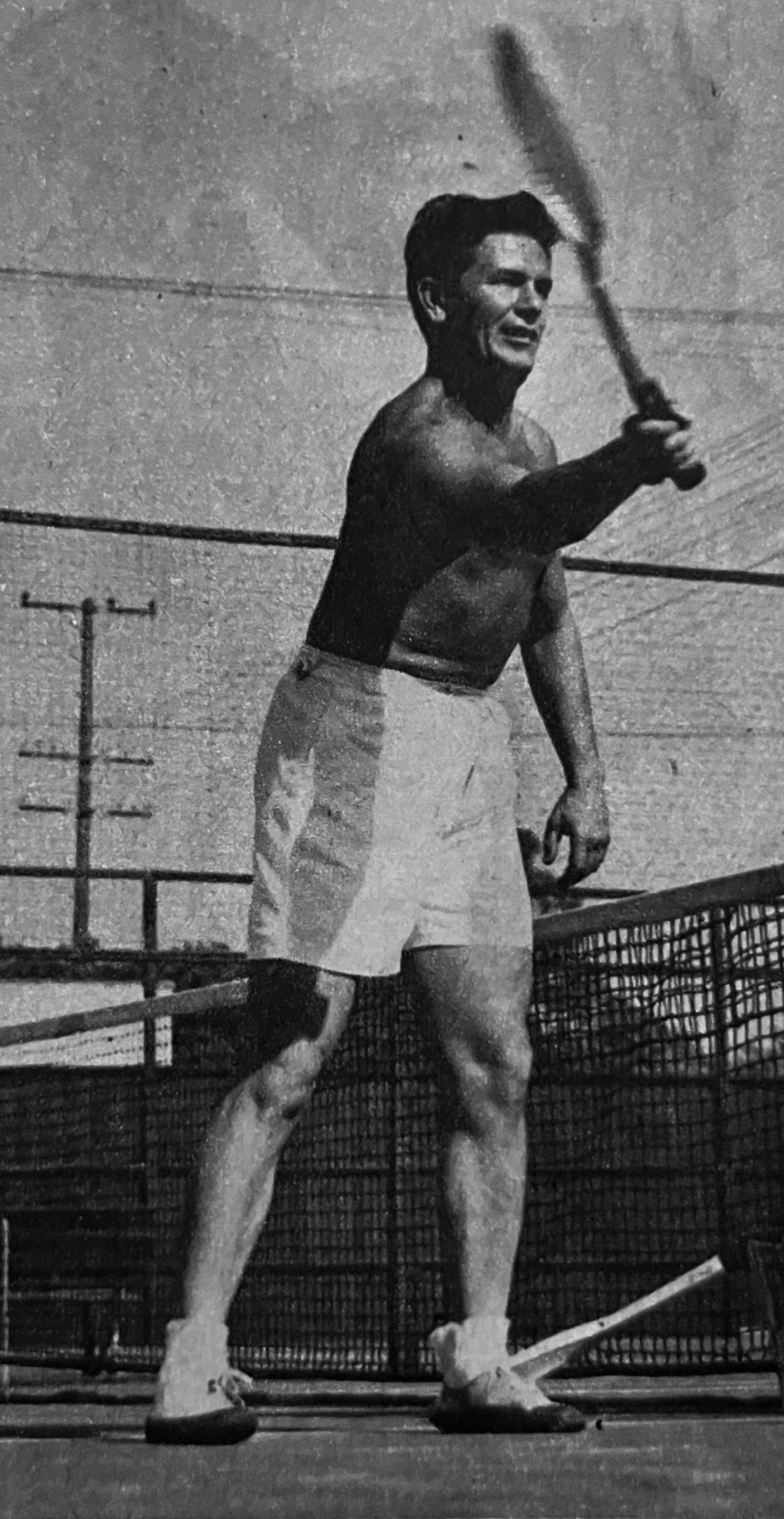

Tennis Anyone?

Not sure which movie magazine or when this is from but it’s pretty fabulous. It seems that Julie loved to play tennis.

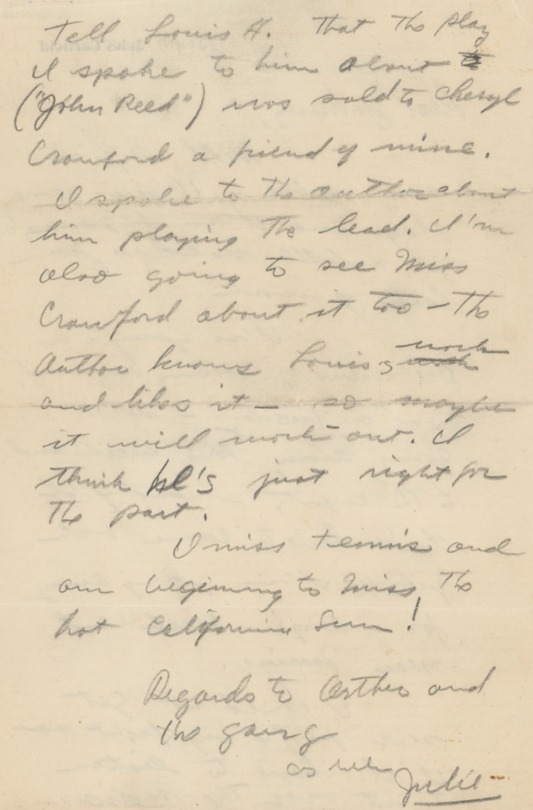

Recently a handwritten letter penned by Julie was auctioned. He has a line in there about tennis. It’s on his personal letterhead, postmarked June 16, 1938.

Letter to Johnny Moreno: "Well, N.Y. is very nice—I saw some plays and I'm beginning to get a little restless from lack of work. I'm going to a pre-view of 'Having Wonderful Time' on Tuesday—We're going away this week-end to the country—and if I don't have to come back July 4, I'm going away for a longer week-end near Maine. I couldn't get seats for the big fight so I'll have to listen to it over the radio. Tell Louis H. that the play I spoke to him about ('John Reed') was sold to Cheryl Crawford a friend of mine. I spoke to the author about him playing the lead. I'm also going to see Miss Crawford about it too—the author knows Louis's work and likes it—so maybe it will work out. I think he's just right for the part. I miss tennis and am beginning to miss the hot California sun! Regards to Arthur and the gang."

Julie in candid footage at the Beverly Hills Tennis Club.

Clowning with Peter Lorre and Richard Conte.

It was also known that Julie had a weak heart and written that he played several sets of strenuous tennis not long before he passed away. It was at a time when he was under tremendous pressure from HUAC and being blacklisted in Hollywood.

One-handed wallop!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

In this, our 2023 Halloween Special, we're featuring Peter Lorre in Mystery In The Air's adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe's "The Black Cat" and a spooky song by Content Abnormal's own Buddy Keys!

Read Content Abnormal magazine issue #6 HERE!

#peter lorre#mystery in the air#edgar allan poe#the black cat#harry morgan#henry morgan#radio#classic#otr#horror host#frankentyner#the crew#halloween 2023#halloween#halloween special#buddy keys#dracula's castle#hell michigan#the return of doctor x#humphrey bogart#suspense#the inner sanctum#creeps by night

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Out of curiosity I looked up Peter’s name in one of the history magazine sites to see if there was anything posted. We do love to remember anyone who made it big and usually on birthdays and deaths. I did find this one article that is being constantly repeated that’s about Casablanca.

But what caught my eye is… they got the name wrong…

You see a lot of Hungarian actors just ‘muricanized their names.

Lukács Pál -> Paul Lucas

Várkonyi Mihály -> Victor Varconi

Kertész Mihály -> Michael Curtiz

Y’all get the jist. There are a few exceptions, and Peter Lorre is one of them, but I guess someone didn’t do a quick Google search, because this is how we got very real Hungarian actor Lőrincz Péter (they even added it as cz to be extra). The thing is I have no idea where they got that from, because when I tried to look it up I only kept finding the same article, but on different sites and strangely enough one German site…

I also doubt that this is a Ernst Lubitsch situation where we just really liked Lubitsch for adapting a lot of works from Hungarian writers into film that we started calling him Lubitsch Ernő.

Anyway I guess it’s from an alternate timeline where everything is the same Peter just has a big bushy mustache or an evil goatee or something.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Serial Killers: The Reel and Real History

“Serial killing, contrary to popular belief, was not a product of the twentieth century. The figure of the serial killer in American culture has been noted as far back as the American Revolution, with the Harpe brothers of 1790s Tennessee possibly falling into the category. Such a lengthy genealogy, however, misses the fact that the serial killer, as a phenomenon, became popular in cinema, in films that explored killing in graphic and unique ways on-screen.

But American gothic literature and other earlier forms do provide a necessary background for reading the serial killer as a particular instantiation of American gothic. The gothic writings of Edgar Allan Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne, especially, prefigure this phenomenon by pointing to the darkness within protagonists who struggle with fractured psyches and personal damnations, leading them towards murder and the macabre.

Unlike European gothic excess, where ruins and dark secrets lead to terrible acts of depravity and murder, often as a response to Catholicism and repression, American gothic turns inward: serial killers in fiction and film tend to be the product of deeply destructive psychological fractures: madness that masquerades just below the surface of everyday normalcy.

Serial killers act out impulsive and buried desires that have been unleashed – recalling the split gothic self of Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde (1886) or Edgar Allan Poe’s unreliable murderous narrators in ‘The Black Cat’ (1843) and ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ (1843) – filtered through a ferocious, destructive individualism, spawning countless screen and literary imitators.

This rooting of the serial killer as a psychological product of ‘cultural damage’ or ‘wound culture’, as Mark Seltzer describes, is an important feature if we are to claim modern serial killer cinema as a product of American fascination with violence, excess and psychological trauma. This psychological trauma also serves as a larger allegory for the nation.

Through the history of cinema, we have witnessed the evolution of the serial killer, from folk tales to news coverage of real murderers, towards the contemporary valorization of the serial killer as a form of celebrity in the American popular imagination. Monsters have moved from the margins to the centre of our world, and it is through the collapse of these boundaries, previously separating them from us, that serial killers have become distorted mirrors of ourselves.

Serial killers regularly feature as a form of the Other that lies just beneath the facade of the normal in our world. The terror of their aesthetic normalcy, of blending in, is central to understanding their invisibility. Yet serial killers on-screen, much like other filmic monsters such as the zombie and vampire, have evolved beyond their earlier perceived fixed states; unlike these monsters, serial killers have always worked from within society itself, and hide their chimeric faces amongst the crowd.

The fixation on the psychological is thus foundational to the modern, cinematic serial killer. The image of, and psychologized concept of, the modern American serial killer is largely shaped by the notorious figure of Ed Gein from Plainfield, Wisconsin. Gein’s case, which came to light in 1957, included cannibalism, necrophilia, skinning his victims, grave robbing and decorating his home with body parts of the deceased; it is still figured as a shocking account of desecration and sexual perversion nestled within a small rural farming community.

Gein’s case featured in Life magazine (2 December 1957), complete with pictures of his filthy home, bringing the case to national attention, and it subsequently became inspirational for numerous screen depictions of serial killers. Gone was the suggestive European strangeness of Hans Beckert (Peter Lorre), from Fritz Lang’s M (1931), and his ilk; American serial killers were now found and made in the homeland of Middle America.

Though Gein was certainly not the first American serial killer since the inception of cinema – H. H. Holmes is believed to have committed at least thirty murders in his gothic ‘Murder Castle’, a labyrinthine hotel which housed unsuspecting visitors to Chicago’s World’s Fair in 1893 – Gein remains, without doubt, the most influential on contemporary film.

He has become ‘multiply interpretable’ (Sullivan 2000: 45) and unfixed, repeatedly cited, re-imagined and revisited as the touchstone in serial killer narratives for its shocking and abject content. While Gein was a partial inspiration for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Silence of the Lambs, to which we will return, perhaps the most famous fictional adaptations inspired by his case are Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel, Psycho, and its 1960 screen adaptation of the same name, directed by Alfred Hitchcock.

Bloch’s novel and Hitchcock’s film both explore psychological trauma and murderous insanity through motel manager and taxidermist Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), an outwardly odd but passive man subject to the whims of his demanding, neurotic mother. That ‘mother’ and Norman are revealed to be one and the same ties Psycho very closely with contemporaneous thought on psychosexual dysfunction, expressed here as a violated and consumed psyche, and murderous impulses.

Beyond the psychological, Psycho is also the most infamous American film to align serial killing with a psychotic break from reality into a realm of fantasy and consumption, a pairing that finds its material echo in the proliferation of serial killer cinema. Alongside the post-Psycho rise of the slasher film of the 1970s and other representations of excess, serial killer cinema came to dominate in later years by sequelization, commodification and blatant imitation.

As Brian Jarvis notes, there are numerous types of serial killer films, which cross-pollinate into other film genres, which ensure their endurance: Serial Killer cinema has many faces: there are serial killer crime dramas (Manhunter (1986), Se7en (1995) Hannibal (2001)), supernatural serial killers (Halloween (1978) Friday the 13th (1980), Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)), serial killer science fiction (Virtuousity (1995), Jason X (2001)), serial killer road movies (Kalifornia (1993), Natural Born Killers (1994)), . . . postmodern pastiche (Scream (1996), I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997)) and even serial killer comedies (So I Married an Axe-Murderer (1993), Serial Mom (1994), Scary Movie (2000)) . . . the serial killer has also become a staple ingredient in TV cop shows (like CSI and Law and Order) . . . (Jarvis 2007: 327–8)

Serial killers are now so ubiquitous as to be commonplace within multiple genres; indeed, they may even feel clichéd or tired as a metaphor for American malaise. Yet, there is something distinctly uncanny about their generic endurance and destructive individualism that is wholly bound to the foundations of the American imagination.

Thus, following Psycho, popular serial films of the mid to late twentieth century have linked psychological disturbances, murderous sexual desires and consumerism run amok; these connections give rise to at least a cursory understanding of the direct connection between what is represented as the serial killer’s compulsive desire to kill again and again, and the larger culture that pours over the minutia of the killers’ lives, their methodologies, and victims’ wounds and corpses.

Seltzer notes, ‘Serial killing has its place in a culture in which addictive violence has become a collective spectacle, one of the crucial sites where private desire and public fantasy cross’ (Seltzer 1998: 253). However, the source or drive of this compulsion has varied substantially on screen from 1960, from sexual deviance to expressions of psychosexual rage, social and economic exclusion, and political and cultural articulations on greed and consumption, through to representations of class, intellect and taste.

More recently, a near superhero status has been conferred onto twenty-first century serial killers through a highly problematic code of ‘morality’, which allows them to operate and thrive amongst the masses as near guardians of justice. That serial killers are hugely popular in film is unsurprising – those who cross moral boundaries are more interesting and appealing on-screen than those who strive to defend and delimit them.

The fiction of presenting an embodiment of evil – one that looks like us – contains enormous narrative appeal, and acts as a framing device by which we encounter, experience and eventually contain the psychological or consumerist cultural threat (temporarily) through a filmic frame. Contrary to the majority of film representations of serial killers in American cinema, real serial killers have been documented by reporters, psychologists and biographers as bland interfaces, rather than the monstrous figures we imagine.

The banality of real-life serial killers in the face of such terrible deeds is in itself uncanny, as we desire the binary equivalence that they must be wholly different and separate from us, entirely other in some capacity, in order to act out in such extreme and violent ways. As Nicola Nixon notes:

The real . . . Gacys, the real Bundys or Dahmers, unlike the charismatic gothic killers of, say, Thomas Harris’s recent fiction, are deeply dull and blandly ordinary . . . it is precisely their ordinariness, their characteristic of ‘sounding like accountants’ and being employed in low-profile ‘unexciting’ jobs like construction/contracting, mail sorting, vat mixing at a chocolate factory that makes their crimes seem all the more shocking. (Nixon 1998: 223)

The conjunction between the real-life serial killers who dominated media in the 1970s and 1980s and film representations of charismatic figures and their shocking crimes all becomes blurred when an uninteresting, and distinctly un-cinematic, blank central figure is unmasked – the killer must be made visually interesting yet abject in order to match the gravity of his crimes and transgressions. Abhorring the narrative vacuum that reveals the true banality of evil, serial killers on-screen must present some depth and command attention if they are to contain, reflect or represent our collective cultural fears.

Gothic monsters in fiction tend to mask their nightmarish selves by exuding charm, intellectualism and depth to lure unsuspecting victims. This is the fictive construct projected onto serial killers, which in turn contributes to their on-screen appeal, in that ‘gothic paradigms allow for the creation of a compelling narrative and consequently the generation of character and plot out of “bland ordinariness” and incomprehensible randomness’ (Nixon 1998: 226).

- Sorcha Ní Fhlainn, “Screening the American Gothic: Celluloid Serial Killers in American Popular Culture.” in American Gothic Culture

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

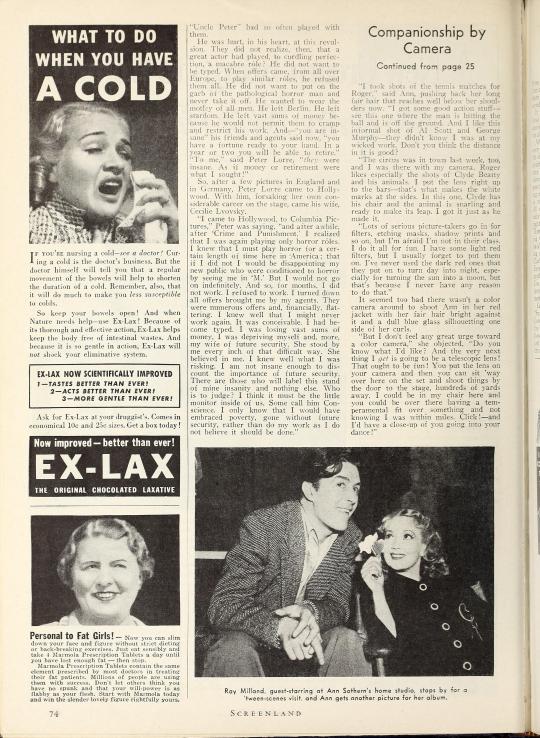

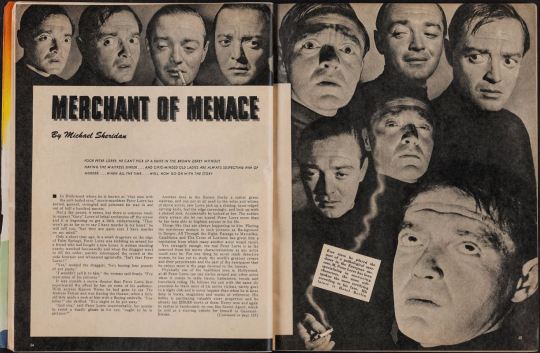

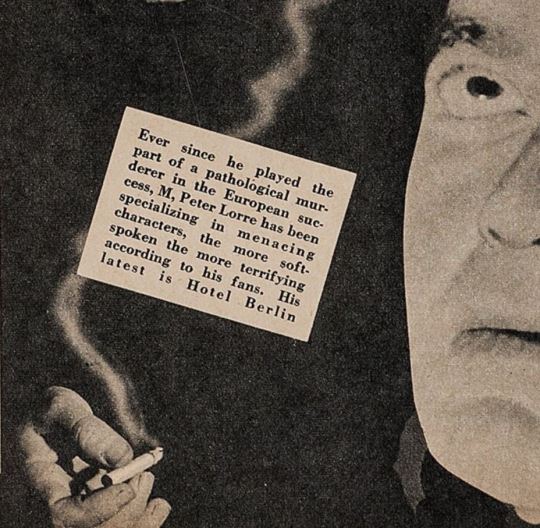

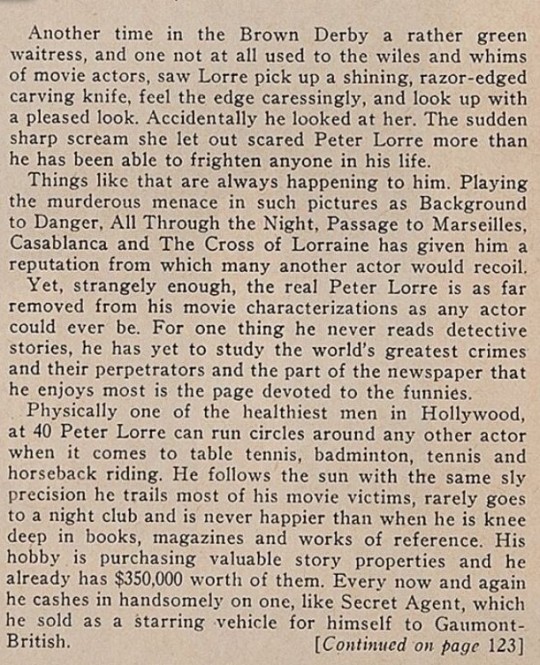

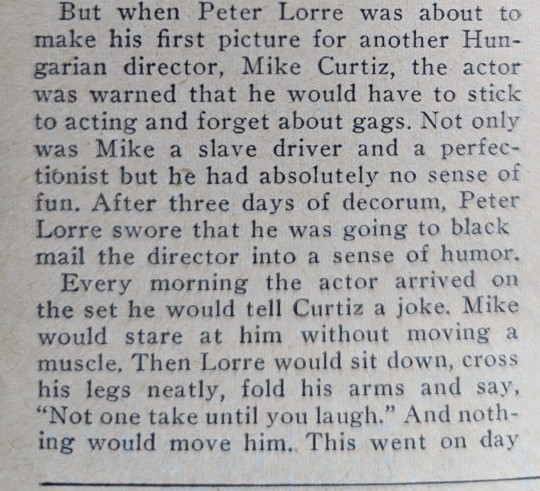

Peter Lorre: Merchant of Menace

Article from "Motion Picture" magazine, February 1945, by Michael Sheridan.

Keep scrolling past the cut to see close-ups of the delectable images - most (all?) of which seem to be from this photoset (and, sidenote, does that change anything about our dating of it?) - PLUS the full article that includes such gems as:

"Gory Lorre"

Calling Humphrey Bogart "Bogartburger" and wishing he could call Edgar Bergen "Bergenburger"

An underground Hollywood legend about his knife collection

The assertion that Peter rarely goes to nightclubs, preferring to "follow the sun with the same sly precision he trails most of his movie victims."

This last close-up is so you can read the inset better - and also I love how they made sure to get at least one burning cigarette in this spread:

Okay, now for the print!

The above shots and these first three images are from a partial copy found on the internet. The rest are from the magazine I tracked down. As such, my copy is creakily old and faded and I took pictures of it with my phone, not scanned (eep!) - but hopefully you can still read it.

And as always, take all Peter Lorre articles with a major side-eye...

"I don't think I would be at ease in such company."

If he really said that, that's a riot!

#peter lorre#Merchant of Menace#peter lorre magazine#peter lorre article#that man looks gorgeous even in print#and with all his faces#peter lorre photoset#merchant of menace

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

STRANGER ON THE THIRD FLOOR (1940) – Episode 142 – Decades Of Horror: The Classic Era

“The only person who ever was kind to me was a woman. She’s dead now.” Wait. What? Join this episode’s Grue-Crew – Chad Hunt, Daphne Monary-Ernsdorff, Jeff Mohr, and guest host Dirk Rogers – as they witness the brilliance of Peter Lorre highlighted by the dark stylings of cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca in Stranger on the Third Floor (1940).

Decades of Horror: The Classic Era

Episode 142 – Stranger on the Third Floor (1940)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel!

Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content!

https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

ANNOUNCEMENT

Decades of Horror The Classic Era is partnering with THE CLASSIC SCI-FI MOVIE CHANNEL, THE CLASSIC HORROR MOVIE CHANNEL, and WICKED HORROR TV CHANNEL

Which all now include video episodes of The Classic Era!

Available on Roku, AppleTV, Amazon FireTV, AndroidTV, Online Website.

Across All OTT platforms, as well as mobile, tablet, and desktop.

https://classicscifichannel.com/; https://classichorrorchannel.com/; https://wickedhorrortv.com/

An aspiring reporter is the key witness at the murder trial of a young man accused of cutting a café owner’s throat and is soon accused of a similar crime himself.

Director: Boris Ingster

Writers: Frank Partos (story & screenplay by); Nathanael West (uncredited)

Music by: Roy Webb

Cinematography by: Nicholas Musuraca

Art Direction by: Van Nest Polglase

Wardrobe: Renié

Special Effects by: Vernon L. Walker (special effects)

Selected Cast:

Peter Lorre as The Stranger

John McGuire as Mike Ward

Margaret Tallichet as Jane

Charles Waldron as District Attorney

Elisha Cook Jr. as Joe Briggs

Charles Halton as Albert Meng

Ethel Griffies as Mrs. Kane, Michael’s landlady

Cliff Clark as Martin

Oscar O’Shea as The Judge

Alec Craig as Briggs’ Defense Attorney

Otto Hoffman as Police Surgeon

Emory Parnell as Grilling Detective in Dream Sequence (uncredited)

Herb Vigran as Reporter Who Wins Cardgame (uncredited)

Bobby Barber as Giuseppe (uncredited)

Stranger on the Third Floor inhabits the creepier side of, shall we say horror-adjacent, film noir. In fact, some experts argue that it is the first example of that dark genre, later to be labeled film noir. It’s a nightmare-influenced murder mystery featuring Peter Lorre chewing on all the scenery he can. Boris Ingster directs Stranger on the Third Floor with all the style that feels as if it could have been an early Val Lewton production. Yup, it’s Hollywood expressionism, RKO-style. This film is worth the watch, even if only for two 7-minute scenes: the nightmare sequence and the interaction between The Stranger (Lorre) and Jane (Margaret Tallichet).

If you have the urge to view this early example of noir filmmaking (or is it “proto-noir?”), and decide for yourself if it is truly horror-adjacent, Stranger on the Third Floor is, at the time of this writing, available to stream from archive.org or PPV from iTunes. There is also a Warner Brothers DVD available if physical media is your preference.

For more Peter Lorre goodness, check out these episodes of Decades of Horror: The Classic Era:

M (1931) – Episode 113

MAD LOVE (1935) – Episode 81

TALES OF TERROR (1962) – Episode 92

THE COMEDY OF TERRORS (1963) – Episode 75

Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror: The Classic Era records a new episode every two weeks. Up next in their very flexible schedule, as chosen by Daphne, will be Diabolique (1940, Les Diaboliques), the French classic directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot, based on a novel by Boileau-Narcejac.

Please let them know how they’re doing! They want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: leave them a message or leave a comment on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel, the site, or email the Decades of Horror: The Classic Era podcast hosts at [email protected]

To each of you from each of them, “Thank you so much for listening!”

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Text

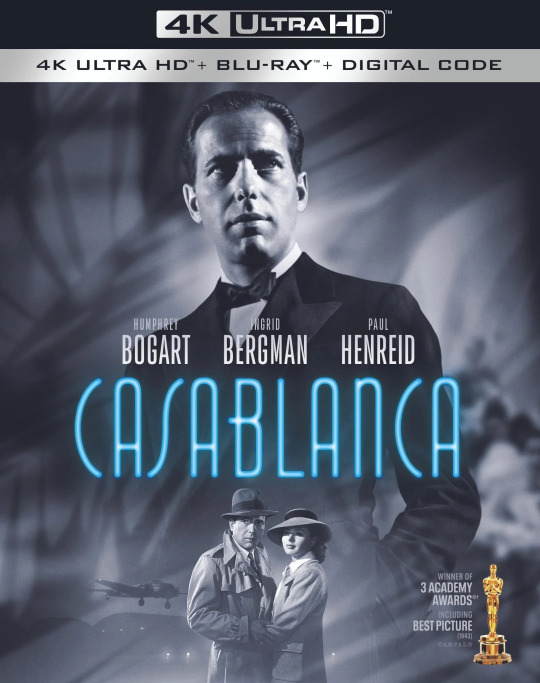

Review: Michael Curtiz’s Casablanca Gets 80th Anniversary 4K UHD Blu-ray Edition

It may be without any new extras, but Warner’s 4K UHD release of Casablanca features a strong enough A/V presentation to make the set worthy of your double dip.

by Jeremiah Kipp & Derek Smith

November 10, 2022

By the time we arrive at Rick’s Café Américain, a certain paranoia and vivacity has been set—and then comes romance, in the form of piano player Sam (Dooley Wilson) and his rendition of “It Had to Be You” as the camera makes a slow dolly toward him through the bustling crowd and wafts of cigarette smoke. It’s easy to fall into the rhythms of Casablanca, long before the appearance of the star-crossed lovers and their damaged idealism, or most of the great character actors who populate the world of Michael Curtiz’s film make their presence felt—such as Sydney Greenstreet’s bemusedly sinister Signor Ferrari and Peter Lorre’s nervously sweaty Ugarte.

The film has a peculiar magic to it, and because of its pace the richness of its sense of detail often goes unnoticed. Audiences make generalizations about Casablanca because of how all those little particulars add up. Film lovers discuss it with a starry look in their eyes, as if they were describing their first kiss or a lost love, because something in the film touches them, perhaps its theme of dignity and decency, of rediscovered idealism. Men seem almost instinctively drawn to Humphrey Bogart’s Rick because he’s a man of integrity, while women seem to dig him because he’s a man of mystery.

There’s also something else to Rick, and it’s visible in his hangdog face. When we first see him he’s playing chess by himself, and the light picks up on a small glimmer of spittle on his lips. Bogart was always a sputtering actor, which made him so great as a B-movie villain cowering for his life before getting shot to death by the hero. But his sudden stardom revealed something incredibly human, and as such relatable, about him. He seemed more like a real man than, say, the frequently idealized characters played by Errol Flynn. The fact that Bogart was a movie star says a lot about his particular charisma—the kind that’s earned by an actor who’s paid his dues and figured out who he is. Rick is his own man, and like those refugees at the start of the film who watch a plane fly above Casablanca, his life experience is written on his face.

Rick is first seen with his back turned to a local who’s had too much to drink. “Rick, where were you last night?” the man says, to which Rick replies, “That was so long ago, I don’t remember.” Even though there’s no overt sex in Casablanca, it’s constantly implied. When Rick orders his bartender to take a girl home in a cab, he asks him to come right back. In the scenes between Rick and Captain Renaud (Claude Rains), the men talk about women as if they were baubles to be admired, then dropped. Renaud also fawns over his friend with the most extravagant, slightly ironic hero-worship, and in a classic line from the film, Rains’s classy, debonair captain tells Ingrid Bergman’s Ilsa Lund that if he were a woman, he’d also be in love with Rick.

It’s astonishing when Bergman materializes some 30 minutes into the film, after Ugarte has whimpered for his life and been shot dead, and Rick has proclaimed that he “sticks his neck out for no one” and came to Casablanca “for the waters.” The shot that first captures the glamorous Bergman doesn’t call attention to itself, or highlight her in the frame, and yet we can’t take our eyes off her. It’s strange, because the shot is very wide, the dress she wears is plain, and she looks nervous and hesitant. How can a woman be so luminous when she’s moving her face back and forth like a deer transfixed by car headlights? When the audience finally sees Ila in close-up, sitting at a table in Rick’s Café with her husband, Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid), her face is somewhat round, her eyes are sharp, and her voice has a certain breathless quality. Bergman, like Bogart, captivates us because of that ineffable thing we call presence. In this moment, the audience instantly understands Rick and Ilsa through the actors’ faces.

If audiences are to admire Rick and Bogart, then we’re meant to adore Ilsa and Bergman. Victor is set up as a great freedom fighter, yet he feels more like an abstract idea or plot point, not unlike the letters of transit that allow people safe passage out of Casablanca. Ilsa, like Rick, is a full person, with vulnerability in her eyes and a magnetism to her presence that goes beyond gauzy lenses and classical three-point lighting. Naturally they’re drawn to one another. She has a lot of big moments in the film, but a lot of small ones too that are just as memorable, such as that tiny, mischievous gleam in her eyes when she asks Sam to play some of the old songs.

There are, of course, the close-ups of Rick and Ilsa when they see each other for the first time as Sam plays “As Time Goes By,” but there’s also the furtive glances that they throw at one another before their eyes flicker back to the table, as they sit chatting about precedents being broken with Victor and Renaud. Casablanca is about striving for something meaningful. But it’s also a tale of sacrifice in the name of greater good, set in a world of shadows, booze, cigarette smoke, and memories. The love story at its center of allows heroes to tap into something special within themselves, and if they lost it in Paris, somehow they got it back in Casablanca. The film is all of those things at once, but it’s also about these people, these faces, and all the little moments between them. It reminds us that when we’re in relationships, we learn more about who we are reflected in others, and when we go to the movies, the great ones can do the same thing.

Image/Sound

Warner Bros. has always rolled out the red carpet for Casablanca before on home video, so it’s no surprise that this 4K UHD release is top-notch. The image quality on their 2012 Blu-ray was already fantastic, but this new transfer gives a noticeable boost in contrast, particularly in the moodier interior scenes in Rick’s Café Américain, where the blacks are now deeper and the varying shades of gray are more clearly defined. There’s also tighter grain levels, which means that there’s new depth and dimensionality to the image. The audio is also flawless, with a well-balanced and robust mix that greatly benefits Max Steiner’s legendary score.

Extras

The extras on this two-disc special edition, all ported over from Warner’s 2012 release, are included on a separate Blu-ray disc in order to maximize the bit rate of the film on the 4K disc. Most noteworthy are the two nicely complementary audio commentaries, one by film critic Roger Ebert and the other by film historian Rudy Behlmer. Ebert and Behlmer each discuss Casablanca’s historical context, behind-the-scenes drama, and the actors’ backgrounds, as well as provide expert critical analysis, and without undue redundancy.

Also included are a pair of feature-length documentaries on Michael Curtiz and Humphrey Bogart that provide in-depth overviews of their respective careers and struggles with the studio system. In another, shorter documentary, Casablanca’s rocky production is the focus. Also stressed is the fact that this was just one of 50 films that Warner Bros. released in 1942, and that no one at the studio or any of its stars expected it to be so acclaimed.

The remaining extras are more bite-sized, including a brief intro to the film by Lauren Bacall, a slick puff piece called “A Tribute to Casablanca,” deleted scenes, outtakes, and an interview with Bacall and Bogart’s son Stephen Bogart and Ingrid Bergman’s daughter Pia Lindstrom, who discuss the enduring legacy of the film. Lastly, there are audio-only features of the scoring stage sessions and a 1947 Vox Pop radio broadcast and a handful of Looney Tunes shorts.

Overall

It may be without any new extras, but Warner’s 4K UHD release of Casablanca features a strong enough A/V presentation to make the set worthy of your double dip.

Score:

Cast: Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, Peter Lorre, Dooley Wilson Director: Michael Curtiz Screenwriter: Julius J. Epstein, Philip G. Epstein, Howard Koch Distributor: Warner Bros. Home Entertainment Running Time: 102 min Rating: NR Year: 1942 Release Date: November 8, 2022 Buy: Video

#Casablanca#Slant Magazine#Jeremiah Kipp#Derek Smith#Humphrey Bogart#Ingrid Bergman#Paul Henreid#Claude Rains#Conrad Veidt#Sydney Greenstreet#Peter Lorre#Dooley Wilson#Michael Curtiz#Philip G. Epstein#Howard Koch#Warner Bros. Home Entertainment#4K UHD#Julius J. Epstein

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In some rather seedy-looking one-star hotel on the Belgian coast

SECRET SQUIRREL, in a moment of contemplation over a bottle of Spa water: Morocco, does it not seem obvious just how women of A Certain Class attract espionage types like us like the proverbial bees to honey?

MOROCCO MOLE, in his best Peter Lorre goloss: And how obvious indeed ... let alone wondering whether such ideas come from as you described them just now. Would they happen to involve certain "girlie" magazines?

SECRET SQUIRREL: I wonder myself, Morocco, whether you actually read such nonsense, to begin with ... after all, such magazines have such delusional ideas about women, to begin with--

[Whereupon some woman of A Certain Class arrives in their hotel room and--I will have to leave to your imagination how this goes from here, even with Spa water as the beverage of choice.]

#hanna barbera#secret squirrel and morocco mole#vignette#one-star hotel#belgian coast#spa water#spa monopole#imagine what follows#hannabarberaforever

0 notes

Photo

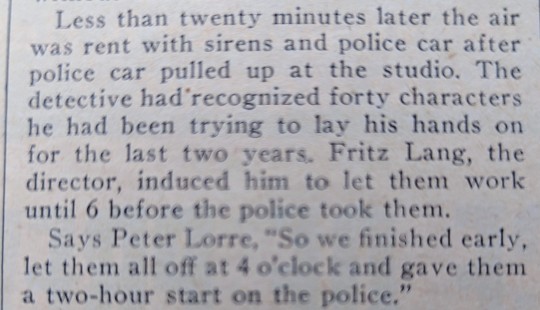

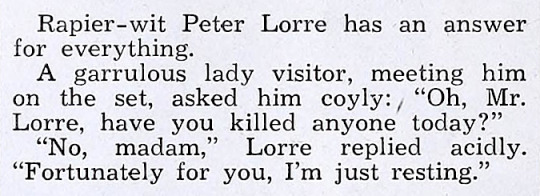

Photoplay, September 1948

#peter lorre#magazine: photoplay#year: 1948#decade: 1940s#type: gossip items and anecdotes#writer: erskine johnson#ph vol. 33 no. 4 48

52 notes

·

View notes