#pat califa

Text

[“When I first came out as a lesbian in 1971, identity politics were so pervasive that this modality didn’t even have a name; it was simply the sea in which every queer sank or swam. One of the key assumptions of identity politics is that we can reveal in one grand social drama of coming out the absolute inner core of truth that makes up one’s “real self.” Coming out is seen as a process like peeling away the layers of an onion or the petals of an artichoke. Identity politics also assumes that your political allies will have to be people who share your identity because nobody else could understand your oppression or really be committed to fighting it; that people who share some aspects of your sexuality but not others are either afraid to come out or traitors to the cause; that it’s not possible for someone to change the way they label themselves without being dishonest or cowardly.

Now I see queer politics quite differently. I know from personal experience that I can’t trust somebody just because their sexual preferences or their gender identity resembles my own. I know we can make allies who are indignant about injustice even if it does not impinge directly upon their own lives. I see coming out as a lifelong process that proceeds as I become ready to understand and accept aspects of myself which bear lessons I need to learn at different points in my life. Each new coming out does not recreate me as a whole new person; I think some people view it this way, but this is crazy-making and too compartmentalized for me. It’s more like being able to see each and every spoke of the wheel that makes up my being, or like opening up and furnishing another new room of my soul.

I wonder what coming out would be like if we were not forced into these defensive positions of tribal loyalty and us-them thinking. What if we could say to a friend who was embarking on a new coming out, “I love you, and so I must also love this new aspect of yourself. Because I care about you I want to know more about it. Let’s both learn from this.” Instead, what usually happens is a great deal of indignation, betrayal, and rejection. I think this is because a person who is coming out threatens the identities of former acquaintances, partners, and coworkers. If someone else’s identity can be fluid or change radically, it threatens the boundaries around our own sense of self. And if someone can flout group norms enough to apply for membership in another group, we often feel so devalued that we hurry to excommunicate that person. This speaks to our own discomfort with the group rules. The message is: I have put up with this crap for the sake of group membership, and if you won’t continue to do the same thing, you have to be punished.

We seem to have forgotten that the coming-out process is brought into being by stigma. Without sexual oppression, coming out would be an entirely different process. In its present form, coming out is reactive. While it is brave and good to say “No” to the Judeo-Christian “Thou Shalt Nots,” we have allowed our imaginations to be drawn and quartered by puritans. I believe that most of the divisions between human sexual preferences and gender identities are artificial. We will never know how diverse or complex our needs in these realms might be until we are free of the threat of the thrown rock, prison cell, lost job, name-calling, shunning, and forced psychiatric “treatment.”

I do not think human beings were meant to live in hostile, fragmented enemy camps, forever divided by suspicion and prejudice. If coming out has not taught us enough compassion to see past these divisions, and at least catch a vague glimpse of a more unified world, what is the use of coming out at all? I have told this story, not to say that anybody else should follow me or imitate me, but to encourage everyone to keep an open mind and an open heart when change occurs. The person who needs tolerance and compassion during a major transformation may be your best friend, your lover, or your very self. Bright blessings to you on the difficult and amazing path of life.”]

patrick califa, from layers of the onion, spokes of the wheel, from a woman like that: lesbian and bisexual writers tell their coming out stories, 2000

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

of course there's a difference between historical terfs (cf. janice raymond and friends) and the professional transphobes funded by christians nationalists that we have today but don't act like there was no correlation at all and dworkin and rich would be trans allies nowadays. you're embarrassing yourself...

radfems been calling butch lesbians and transmasc people "self-hating women" since radical feminism existed. search "sex wars" on google scholar. this sex-negative and anti-butch period of radical feminism is well documented by Jack Halberstam ('Female Masculinity' (1998)), Pat Califa (cf 'Public Sex: The radical culture of radical sex' (1994)) and Gayle Rubin. like, in general, listen to transmasc people who've been there back in the days.

#transmasc history#terf#anti transmasculinity#transandrophobia#trans#trans history#adrienne rich#andrea dworkin#pat califa#gayle rubin#jack halberstam#radfem#tirf#butch lesbian#butch male

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

i love being a man w a vagina i fucking love it

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

fic commentary/notes for the year you thought you were dying.

trying this thing where i do fic commentaries here instead of on dreamwidth since most of my recent dw posts will be private now.

influences:

there was this BL titled "my 40-year-old prostitute" in english or something like that that a mutual from twt recommended. look, it was good. im so fucking serious. the yaoi art was beautiful and sexy and it started out so well with compelling characters. but the translators ceased uploading translations by just chapter 2 in 2020 on [redacted] site. which effectively meant the premise never left me for months and i was so sad.

joke's on me tho all of this really became serious after i wrote tumblr ficlets of 1418 hooker au in response to some fun ask prompts in the summer, which are in my fic tag somewhere.

some quotes from more influences:

"It’s obvious that the range of people who sought out sex for money would change dramatically in a kinder, gentler world. [...] Sex work would also attract stone butches of all genders and sexual orientations—people who want to run the fuck but are not interested in experiencing their own sexual vulnerability and pleasure. Often these people are the most adept at manipulating other people’s experiences. They are more objective about their partners’ fantasies and do not become distracted by their own desires, since their needs to remain remote and in control are already being fulfilled. - pat califa, 1994, 2000

"You. What will you let yourself become for me?" - dorothy allison, her thighs, 1992.

the essay "her thighs" is about lesbian power play and so influential to me. i think dorothy allison is a very powerful writer and i love her poetry.

this is an allison excerpt from jane ward's the tragedy of heterosexuality:

i kept this in mind too while i was writing manuela's short backstory.

the process:

i wanted crazy thangs with the structure. i wanted most of the sexual intimacy to be revealed much later to the reader, after we go through mostly the companionship aspect of the service -- which i realise now is not crazy but a boring approach and would really change the story so i didnt do it.

sex pollen fic done this way is my fave tho. helenish wrote this sga fic called This Gun for Hire with sex amnesia in it where everyone is in denial in the aftermath about the kind of sex that was repeatedly happening. there are other fic examples (can't quite remember or have bookmarked) where the denial and delusion is so completely off the charts with a character in trying to get through the aftermath of the event without a freaky sex trope involved.

so i wondered if i could pull off that kind of blurriness and denial in the structure for a character who KNOWS what is happening but thinks they're still straight and will die straight lmao. but fernando in this story is just jaded, retiring and isn't cripplingly repressive.

the notes from my word tracker doc that i had to do to be able to write long fic. i laugh at this every time:

my projected word count for this was 20k, which was so off lmfao.

i put off getting them to have sexy fun in italy at one point because i didn't know yet what emotional point they needed to get to and what grounds they'd be on then. i wrote a bit of a very different scene to lead up to it, but then scrapped it. and then i wrote the auction night and the morning-after scene. tension and conflict (without having to use miscommunication as the necessary crutch) is always one of my most favorite things to write about so i was so glad i got to this point LOL. the payoff of reaching a compromise and then an emotional release later is so rewarding to me! i love that shit

emotionally i just knew i needed it to be like the mindy nettifee poem i grabbed the fic title from.

figuring out how to write lance in this fic was really hard ngl since i went into the story almost blind. cofi made me realise this blind spot when i showed her an early wip and i was like hold awn.... if i wasn't sending @strulovic broken drafts and doing lanceology consultations with her, i wouldn't have gotten anywhere in the story.

alonso being a divorcee irl is so important to each and every one of my agendas thank god for the gay uncle. i did a lot of google searching to be able to write fernando's approach to sex and relationships outside of the job. i knew what i wanted to take away, like the difficulties with intimacy that former workers have had, and still have after the industry sometimes. fernando scrubbing his hands clean at lance's place after the auction despite not having sex with the auction client, his views on wanting the sex with his ex-wife and other exes to be "acceptable and proper" in contrast to whatever he's done for work, and how the internalised homophobia warps this for him while he tries to play the gentleman with lance in italy (and lance being able to read through him and understand that fernando DOES want to fuck him nasty ‼️ though lance doesn't understand the extent of fernando's issue with it). there are also accounts where sex work gave a worker the experience, space and autonomy they needed to slowly heal from prior traumatic and/or abusive experiences. the research was very interesting.

relied on music A LOT. an honorary ldr song [hears collective groaning] that didn't get included in the fic playlist was Love song. lance was in that passenger seat beside fernando in their sleek '67 restored fiat on the way to umbria wishing and wishing to get railed.

ALMOST FORGOT TO INCLUDE: ferrari to mclaren 2.0 fernando was the print here. he keeps the ferrari depression beard ofc.

truly not an overstatement, i think this fic was what made writing smth as long as this quite enjoyable and bearable for me. dare i say fun! haha

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

today was very good :) skipped work to go to the gerber/hart book sale which was fun, and i learned that you can check things out of their library so i got childlike life of the black tarantula (!) the sophie horowitz story (!!) and the indelible alison bechdel (!!!!!!!!!). went and checked out the leather archives and finally got to read a bit of pat califa's erotica which i've been soooooo curious about since i saw bloodsisters. and then i went and smoked and read on nell's porch in the sun <3

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

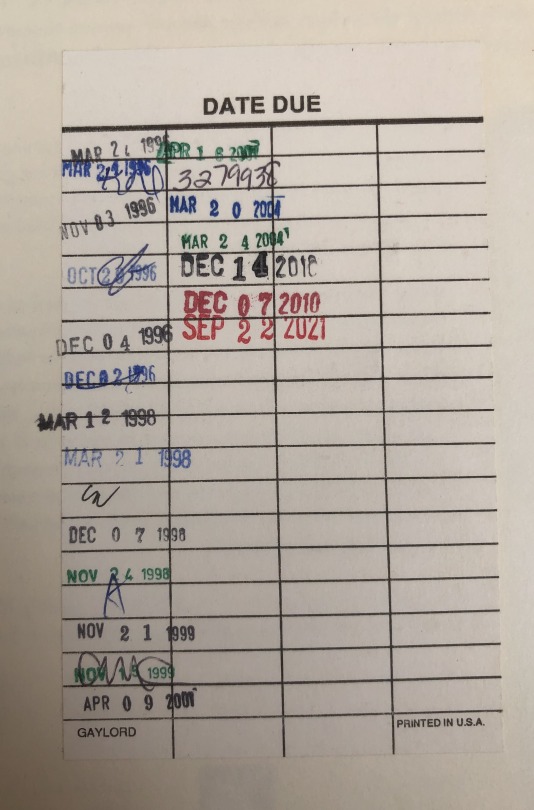

When people got out my copy of Pat Califa’s Public Sex from Florida’s Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University

1 note

·

View note

Text

Queers/libfems hate on radical feminism but proudly put queer theory on a pedestal like it didnt produce some of the most pro-pedophilica arguments. If you're going to hate one, you better damn well critique the other.

0 notes

Note

@perfina reading books by trans people is what made me see through their sexist and homophobic ideology. Big thanks to my professor for making us engage with Julia Serano, Tobi Meyer-Hill, Susan Stryker, and Pat Califa. Just insane misogynists.

would love to know the shit you learned from some of them as only two sound familiar to me 👀

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

sick sick sick

The Art of Cruelty is a book by Maggie Nelson which is about things that are, in the words of the author, not nice. Shouldering aside the semantic ambiguities of defining exactly what is meant by ‘cruel’, the book leans heavily on a sense of knowing it when it is seen. An instinctive feeling of revulsion, followed by a certain compulsion to investigate further. An unwillingness to break the gaze because of what the viewer feels, in spite of whatever they might believe. The works under discussion here seem intended to leave their audience feeling like the unhappy student quoted here, with reference to a controversial novel by Brian Evenson: ‘I feel like someone who has eaten something poisonous and is desperate to get rid of it.’

It is a book about the visual arts, performance, poetry and film, clearly informed by many of years of study and teaching. But it’s also a book about a writer struggling to account for her feelings of fascination/repulsion towards some of our society’s most startling artistic productions. It suffers from a certain surfeit of ambition: it struggles to pin down exactly what a ‘cruel’ work of art is, beyond a tendency towards shock or violence, either in its expression or representation. And at times it is hard to detect a thesis; sometimes the thread of the argument is lost in a blizzard of quotation. Yet it’s exactly this lack of polish, this sense of awkward self-remonstrance, that makes the book so endearing.

It takes the work of Antonin Artaud as its starting point, and specifically his term ‘The Theatre of Cruelty’. Derived from his book The Theatre and its Double, this was an approach to performance outlined in stark, boldly abstract terms: ‘Everything that acts is a cruelty…It is upon this idea of extreme action, pushed beyond all limits, that theatre must be rebuilt…’. Founded in the abolition of concepts like ‘performers’ and ‘audience’, Artaud’s actual performances were startling, violent works, and rarely executed properly in his lifetime; his work was difficult, and he suffered terribly from mental illness. Nelson’s contention is that he was an artistic failure, though his theories were highly prescient.

Some, but not all, of the other artists presented here fall into that category too; interesting to read about, but in execution alienating, dull or confused. Like Artaud they seem against theory in principle, yet were it not for theory their reputation would have vanished. I can’t muster any interest in the works for which Chris Burden became notorious, for example — filming himself crawling half-naked over broken glass, or being shot in the arm — but perhaps that says more about our current over-exposure to violence than it does the value of his actions.

The book somehow manages to be both sprawling and narrow in its interests: it covers a vast range of material, but it rarely steps outside the kind of thing which we might find in a well-stocked university library. Today there are vast swathes of Western culture that might fittingly be described as ‘cruel’, but which are barely touched upon here. Violent sports, video games, graphic novels, horror fiction, pornography, pop music and mainstream movies all seem to fall outside the book’s purview. This is fair enough, of course; though to me it seems like a decision prompted by inherent value judgements that ends up limiting the expressive range of the writing.

The films of Ryan Trecartin, for example, are praised to the skies for their remarkable expressive qualities — ‘a riotous exploration of what kinds of space, identity, physicality, language, sexuality, and consciousness might be possible once leaves the dichotomy of the virtual and the real and behind, along with a whole host of other need-not-apply boundaries’ — but this, combined with the compulsion to quote from other approving authority figures, ends up telling the reader very little about what it is like to actually experience these films.

Despite the fact that Trecartin seems to have been lauded by establishment art critics, it seems to me that most of his influences most of them have very little to do with established art. It’s as though Warhol were described only in terms of his brushwork and printmaking, with no mention of contemporary trends in media production. It’s bizarre to encounter Trecartin’s work after reading this; for me it’s shot through with the kind of hyperactive, unsophisticated viral culture that circulated in the earliest days of the internet, and it seems odd to pretend these influences don’t exist because they have everything to do with play and little to do with art.

Nelson’s approach is unashamedly highbrow, and she’s lightly scathing about the lack of value she finds in current approach to pop culture criticism:

‘I’m not saying there’s no fun or value or necessity in this work anymore; maybe there’s more than ever. I’m just saying that for me, personally, it feels like a dead end. The cultural products now seem designed to analyse themselves, and to make a spectacle of their essentially consumable perversity.’

There’s a lot to agree with in this statement — god knows what Nelson would make of Game of Thrones — but it’s also a nice illustration of the novel’s typically enjoyable one-two stylistic punch. First the brusque avowal of a position; then a light-hearted refusal of it; followed by a final, definitive statement of intent. It’s the old cliche about ‘I’m not saying / I’m just saying’ — yeah, actually you are saying exactly that thing you’re not saying. If this were an academic paper, surely only the third sentence would be permissible. This is typical of the author’s bobbing and weaving throughout here — it makes for an entertaining, conversational read, but at times it’s difficult to unpick exactly what we are supposed to take home.

The effect is a little like sitting in on a seminar with a group of funny, opinionated, well-read people who have not yet decided ‘how to feel’ about something that has affected them greatly. But perhaps the idea that we have to reach a definitive position on ‘how to feel’ about everything is itself the problem.

The book is actually at its most entertaining when it is at its most incomplete. The sequence following the quote above departs entirely from its format and switches into the author’s reaction to the billboards advertising a horror movie that suddenly appeared around Los Angeles in 2007:

‘…you call to complain, disliking the sound of your Tipper-Gore-esque voice. You hang up and start worrying about the free-speech implications of your protest, so you turn to Noam Chomsky and ponder hard questions about manufactured consent and the meaning of free speech in an everything-is-owned-or-for-sale world, then to Jurgen Habermas, to ponder the meaning of public space is an everything-is-owned-or-for-sale world…So you wonder how to tell what emanates from where, and how you might balance your visceral outrage against the Captivity emanations with your deep veneration of writers from Sade to Jean Genet to Dennis Cooper to Heather Lewis to Pat Califa to Benjamin Weissman, and ask yourself if you can keep resting on some quasi-nostalgic and most certainly elitist (but not-wholly-without-significance) between high and low art, or the value of the complex and essentially private written word versus that of the mass marketed, in-your-face media image…’

It goes on for another page or so like this. And this model of throwing up endless little questions that it doesn’t stop to answer is essentially the model pursued for the rest of the book. It models exactly the author’s own frustrations with the cul-de-sac of pop culture criticism previously expressed; but it makes no attempt to find a new model, nor does it entirely escape the same trappings. What is this if not making a spectacle of an essentially consumable perversity?

And yet this is the closest the book comes to a clear picture of the current predicament of anyone who would try to write about the most extreme examples of culture. A little learning is a dangerous thing; the weight of critical theory in this field is so considerable that it ends up stifling the original reaction which brought you to it in the first place. But that is worth preserving — and so, perhaps, is the associated confusion.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“Why not identify as bi? That’s a complicated question. For a while, I thought I was simply being biphobic. There’s a lot of that going around in the gay community. Most of us had to struggle so hard to be exclusively homosexual that we resent people who don’t make a similar commitment. A self-identified bisexual is saying, ‘Men and women are of equal impor- tance to me.’ That’s simply not true of me. I’m a Kinsey Five, and when I turn on to a man it’s because he shares some aspect of my sexuality (like S/M or fisting) that turns me on despite his biological sex.

There’s yet another twist. I have eroticized queerness, gayness, homo- sexuality – in men and women. The leatherman and the drag queen are sexy to me, along with the diesel dyke with greased-back hair, and the femme stalking across the bar in her miniskirt and high-heeled shoes. I’m a fag hag.

The gay community’s attitude toward fag hags and dyke daddies has been pretty nasty and unkind. Fag hags are supposed to be frustrated, traditionally feminine, heterosexual women who never have sex with their handsome, slightly effeminate escorts – but desperately want to. Consequently, their nails tend to be long and sharp, and their lipstick runs to the bloodier shades of carmine. And They Drink. Dyke daddies are supposed to be beer-bellied rednecks who hang out at lesbian bars to sexually harass the female patrons. The nicer ones are suckers who get taken for drinks or loans that will never be repaid.

These stereotypes don’t do justice to the complete range of modern faghaggotry and dyke daddydom. Today fag hags and dyke daddies are as likely to be gay themselves as the objects of their admiration.

I call myself a fag hag because sex with men outside the context of the gay community doesn’t interest me at all. In a funny way, when two gay people of opposite sexes make it, it’s still gay sex. No heterosexual couple brings the same experiences and attitudes to bed that we do. These generalizations aren’t perfectly true, but more often than straight sex, gay sex assumes that the use of hands or the mouth is as important as genital-to-genital contact. Penetration is not assumed to be the only goal of a sexual encounter. When penetration does happen, dildos and fingers are as acceptable as (maybe even preferable to) cocks. During gay sex, more often than during straight sex, people think about things like lubrication and ‘fit’. There’s no such thing as ‘foreplay’. There’s good sex, which includes lots of touching, and there’s bad sex, which is nonsensual. Sex roles are more flexible, so nobody is automatically on the top or the bottom. There’s no stigma attached to masturbation, and gay people are much more accepting of porn, fantasies, and fetishes.

And, most importantly, there is no intention to ‘cure’ anybody. I know that a gay man who has sex with me is making an exception and that he’s still gay after we come and clean up. In return I can make an exception for him because I know he isn’t trying to convert me to heterosexuality.

I have no way of knowing how many lesbians and gay men are less than exclusively homosexual. But I do know I’m not the only one. Our actual behaviour (as opposed to the ideology that says homosexuality means being sexual only with members of the same sex) leads me to ask questions about the nature of sexual orientation, how people (especially gay people) define it, and how they choose to let those definitions control and limit their lives.

During one of our interminable discussions in Samois about whether or not to keep the group open to bi women, Gayle Rubin pointed out that a new, movement-oriented definition of lesbianism was in conflict with an older, bar-oriented definition. Membership in the old gay culture consisted of managing to locate a gay bar and making a place for yourself in bar society. Even today, nobody in a bar asks you how long you’ve been celibate with half the human race before they will check your coat and take your order for a drink. But in the movement, people insist on a kind of purity that has little to do with affection, lust, or even political commitment. Gayness becomes a state of sexual grace, like virginity. A fanatical insistence on one hundred percent exclusive, same-sex behaviour often sounds to me like superstitious fear of contamination or pollution. Gayness that has more to do with abhorrence for the other sex than with an appreciation of your own sex degenerates into a rabid and destructive separatism.”]

pat califa, public sex: the culture of radical sex, 1994, 2000

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

In de bijbel van de S.M. leersien The Leather man’s Handbook II van Larry Townsend krijgt de S.M. fantasie nauwelijks aandacht

In de bijbel van de S.M. leersien The Leather man’s Handbook II van Larry Townsend krijgt de S.M. fantasie nauwelijks aandacht

In de bijbel van de S.M. leersien The Leather man’s Handbook II van Larry Townsend krijgt de S.M. fantasie nauwelijks aandacht

Dat werk van Townsend voor beginners zowel als gevorderden in de homosexuele S.M. sien is ook sterk gericht op de Amerikaanse S.M. sien en die is heel anders dan de Europese situatie.De lesbo S.M. activiste Pat Califa geeft de fantasie wel een grote rol in het essay dat…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

I've been examining some of the myths that I've heard from other lesbians about butches. Some of these rules made sense back in the '50s. But I think we need to evaluate our stereotypes and make some new rules for role-playing. It's time to bring butch/femme into the '90s, or we'll never get what we're jonesin' for.

Real butches are supposed to be born, not made. And real butches are supposed to know how to make love to other women automatically, without instruction. This pair of myths sets butches up to compete with one another instead of being able to teach, support, or help each other. It also makes many of us extremely brittle about our act in the bedroom. A partner who asks us for something specific can make us nasty and defensive.

If you're really butch, you're never supposed to wear women's clothes. You're supposed to hide your female body, especially in bed. If you are a liberated butch, you might take your shirt off, but a surprising number of butches still leave all of their clothes (including their boots) on during sex.

These structures are bosed on the idea that there is something shameful and inherently helpless about women's bodies. Butches (especially if they are identifiable as such during childhood) get told a lot that they are failures as women. We're told that we're ugly and clumsy. We're often threatened with violence or abuse because "somebody needs to show you you're really just a girl." In addition to receiving these negative messages from the outside, many butches have their own uneasy feelings about being born into the wrong body.

Pat Califa, “Butch Desire.” Included in Dagger: On Butch Women. 1994.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“Coming out was very lonely. I had very few friends. Most of the adult lesbians I knew were alcoholics, chronically unemployed, prone to violence, self-hating, apolitical, closeted, cliquish. Lesbians hated each other. If you found a lover you stopped going to the bar because you could not trust other lesbians; they would try to break up your relationship. My first woman lover went into the military, where she turned in other lesbians so she would not be exposed. One of my dyke friends got a job as a supervisor in a cabinet-making company and refused to hire lesbians because, she said, they were unreliable employees who were disliked by the other workers. The only thing that seemed worse to me than the apolitical lesbian community I came out in was the strangulation of pretending to be straight. I came out only because I could not go back; there was no place for me to stand in the het world. I was driven out.

Moving to San Francisco improved things somewhat. There was more public lesbian space there—six bars instead of one. But it did not alleviate the loathing with which my family viewed me. Nor was San Francisco in the early seventies any sort of gay utopia. We had no gay-rights law, queer bashing was a frequent event, and everyone had lost at least one job or been denied a place to live. It was a relief to be surrounded by other lesbian feminists, but only to a point. Bar dykes and feminists still had contempt for one another. Feminism rapidly became a way to reconstitute sexual prudery, to the point that it seemed to me that bar dykes were actually more accepting of and knowledgeable about the range of behavior that constituted lesbianism. In the bars or in the women’s movement, separatism was pretty much mandatory, if you didn’t want to get your ass kicked or be shunned. Separatism deteriorated into a rationalization for witch hunts in the lesbian community rather than a way for women to bond with one another and become more powerful activists. The lesbian community of that decade did terrible things to bi women, transgender people, butch/femme lesbians, bar dykes, dykes who were not antiporn, bisexual and lesbian sex workers, fag hags, and dykes who were perceived as being perverts rather than über-feminists. We were so guilty about being queer that only a rigid adherence to a puritanical party line could redeem us from the hateful stereotypes of mental illness and sexual debauchery.

What did I gain? I came a little closer to making my insides match my outsides, and that was no small blessing. The first time I met other dykes I recognized a part of myself in them, and knew I would have to let it out so I could see who I was. For a time, being a lesbian quieted my gender dysphoria because it made it possible for me to be a different kind of woman. That was an enormous relief.

For a long time, I hoped that by being strong, sexually adventurous, and sharpening my feminist consciousness, I could achieve a better fit between my body and the rest of me. Lesbianism was a platform from which I could develop a different sort of feminism, one that included a demand for sexual freedom and had room for women of all different erotic proclivities. I had a little good sex and discovered that I was not a cold person, I could love other people. It was as a lesbian that I began to find my voice as a writer, because in the early days of the women’s movement, we valued every woman’s experience. There was a powerful ethic around making it possible for every woman to speak out, to testify, to have her say. But there were always these other big pieces of my internal reality that lesbianism left no room for.

The first big piece of cognitive dissonance I had to deal with, in my second coming out, was S/M. I date my coming out as a leather dyke from two different decisions. One was a decision to write down one of my sexual fantasies, the short story that eventually became “Jessie.” At the time I wrote the rough draft of that story, I had never tied anybody up or done anything else kinky. I was terribly blocked as a writer. I kept beginning stories and poems that I would destroy. I have no idea if they were any good or not. My self-loathing was so intense, my inner critic so strong, that I could not evaluate my own work.

So I decided to write this one piece, under the condition that I never had to publish it or show it to another person. I just wanted to tell the truth about one thing. And I was badly in need of connecting with my own sexuality since I was in the middle of what would be a five-year relationship with a woman who insisted we be monogamous, but refused to have sex with me. So I wrote about dominance and submission, the things I fantasized about when I masturbated that upset me so much I became nauseated. Lightning did not strike. As I read and reread my own words, I thought some of them were beautiful. I dared show this story to a few other people. Some of them hated it. Some of them were titillated. Nobody had ever seen anything like it before. The story began to circulate in Xerox form, lesbian samizdat. I found the strength to defend my story when I was told it was unspeakable or wildly improbable.

In October of 1976, I attended a lesbian health conference in Los Angeles and went to a workshop there about S/M. In order to go to a workshop, you had to sign a registration sheet. I was harassed by dykes who were monitoring this space to see who dared sign up for that filthy workshop. On my way, I had to walk through a gauntlet of women who were booing and hissing, calling names, demanding that the workshop be canceled, threatening to storm the room and kick us all out of the conference. The body language and self-calming techniques I had learned when I had to deal with antigay harassment on the street came in very handy, but how odd it was to be using those defenses against the antagonism of other dykes. Their hatred felt like my mother’s hatred. I am so glad I did not let it stop me.

When I got home from that workshop, I knew that I was not the only one. Not only were there other lesbians who fantasized about sadomasochism, there were women who had done these things with each other. I decided to come out again. If there were other leather dykes in San Francisco, they had to be able to find me, so I had to make myself visible. This meant that I often did not get service at lesbian bars, or I was asked to leave women-only clubs and restaurants. I was called names, threatened, spit at. I got hate mail and crank calls. But I also found my tribe. And because I had already experienced my first coming out, I knew we were not going to be an ideal, happy family. I could be more patient with our dysfunctions, and see them as the result of being scared, marginalized, kicked around. Being a leather dyke took me another step closer to dealing with my gender issues. I could experiment with extreme femme and extreme butch drag; take on a male persona during sex play. I gave up separatism because I needed to take support from any place where it was available. Gay men already had a thriving leather culture, and I wanted to learn from them. I also wanted to have sex with them. It still wasn’t okay as far as lesbian feminism was concerned to be bisexual, to be transgendered, but I could bring those folks into my life and make alliances with them. I could defend them in print. There was even more good sex, and people who loved me and received my love despite the fact that it was dangerous for us to show ourselves to one another. I faced my sexual shadow, and she bowed to me and then danced beautifully in profile against the white walls of my consciousness. My writer’s voice was unlocked.”]

pat califa, from layers of the onion, spokes of the wheel, from a woman like that: lesbian and bisexual writers tell their coming out stories, 2000

#pat califa#bi literature#lesbian literature#trans literature#history stuff#gender stuff#terra preta

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“The fact that my body has become a source of at least as much misery as pleasure has paradoxically made it easier for me to stop calling myself a lesbian and use the term bisexual instead. I just don’t have the energy any more to hold up facades. Back in 1971, I initially told people I was bisexual, but discovered this meant that straight people saw me as a heterosexual who occasionally dabbled in not-very-serious sex with “other girls,” while gay people saw me as a dyke who hadn’t come all the way out of the closet yet. Nobody trusted me, and nobody would dance with me. In 1980, when Sapphistry was about to be published and my first article about lesbian S/M appeared in The Advocate, I said in that article that if I had a choice between being marooned on a desert island with a vanilla dyke or a leather boy, I would take the boy. I got an extremely irate phone call from Barbara Grier, owner of Naiad, the company that was going to publish Sapphistry, informing me that they did not publish books by bisexual women, and if that was what I was, she would yank the book. Already in the midst of a firestorm about being public as a sadomasochist, I acquiesced, and delayed this coming out by another twenty years. I became “a lesbian who sometimes has sex with men.”

I still think this is a valid category, and remain unconvinced that the most important thing you can know about someone’s sexuality is the preferred gender of their partner. But today I’d rather not argue about it. I need to keep things as simple as possible. Bisexual people are still being excluded from the gay community’s cultural and political life. And I find myself being personally affected by that exclusion. It hurts me and makes me angry in a way that it would not, I think, if I were not on some level affiliated with bisexuals. I would rather stand with a group of people who don’t expect me to turn myself into a pretzel to explain what makes my dick get hard. This doesn’t mean I think it’s wrong or passé to be a Kinsey 6. But I do think a quest for purity of any sort is almost always morally dangerous.

Being more open about having sex with men has brought my own gender dysphoria to the fore. When I put my body up against a male body, what I notice is how hard it is for me to feel connected to my own flesh. Even more important has been the experience of loving someone who is a female-to-male transsexual (FTM), my domestic partner, Matt Rice. I knew Matt before he transitioned, and it has been such a positive change for him. By taking testosterone and getting chest surgery, he not only allowed himself to become and live as a man, he became a much better person—kinder, more patient, happier, sexier, sweeter. (Although he still won’t suffer fools gladly.) The fact that Matt has managed his transition with this degree of success gives me hope that I might be able to find a less distressing place for myself. I expect, like any other coming out, this will have its shitty aspects. But I think it will also create a greater sense of freedom and comfort.”]

pat califa, from layers of the onion, spokes of the wheel, from a woman like that: lesbian and bisexual writers tell their coming out stories, 2000

110 notes

·

View notes