#pacific northwest geology

Video

44 Tidal Channels—Skagit River Delta 4:3 ratio, 7200x5400 pixels, no text by Washington DNR

Via Flickr:

Tidal channels in the expansive Skagit River Delta in Skagit County. Image by Daniel E. Coe, Washington Geological Survey Other versions of this image: High-resolution 16:9 ratio image with text High-resolution 16:9 ratio image without text High-resolution 4:3 ratio image with text Learn and see more: WGS Lidar page The Bare Earth lidar story map Washington Lidar Portal You may use this image for any purpose, commercial or non-commercial, with or without modification, as long as you attribute us. For attribution please use ‘Image from the Washington Geological Survey (Washington State DNR)’ if it’s a direct reproduction, or ‘Image modified from the Washington Geological Survey (Washington State DNR)’ if there has been some modification. For more information, see the linked Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license.

#lidar#washington geology#washington geological survey#washington dnr#geology#geomorphology#pacific northwest#pacific northwest geology#wa100#lidar art#cartography#maps#map#high resolution#hi-res#flickr#nature

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some moody forest shots from Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon (Oct. 2021).

#oregon#photography#not geology#pacific northwest#forest#clouds#aesthetic#cozycore#mount hood#cascade mountains#pnwonderland#pnw vibes#pnwexplored#pnw#pnw photography#original photography#original photography on tumblr#lensblr#nikon#my photography

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jagged

What do you think about my pic?

#Mt Bailey#Mount Bailey#shield volcano#Cascade Range#Oregon#Pacific Northwest#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#countryside#forest#woods#summer 2023#geology#rocks#nature#flora#photo of the day#Douglas County

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Point Lobos, California

#point lobos#Point Lobos State Reserve#california#Visit California#pacific ocean#Pacific Coast#pacific northwest#cmt photography#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#nature photography#landscapes#landscape photography#geology#rocky coastline

975 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Tell a Friend Friday!

Please enjoy this photo I took of Wy'east (Mt. Hood) a few years ago on a backpacking trip on Section G of the Pacific Crest Trail.

Then tell someone you know about my work–you can reblog this post, or send it to someone you think may be interested in my natural history writing, classes, and tours, as well as my upcoming book, The Everyday Naturalist. Here’s where I can be found online:

Website - http://www.rebeccalexa.com

Rebecca Lexa, Naturalist Facebook Page – https://www.facebook.com/rebeccalexanaturalist

Tumblr Profile – http://rebeccathenaturalist.tumblr.com

BlueSky Profile - https://bsky.app/profile/rebeccanaturalist.bsky.social

Twitter Profile – http://www.twitter.com/rebecca_lexa

Instagram Profile – https://www.instagram.com/rebeccathenaturalist/

LinkedIn Profile – http://www.linkedin.com/in/rebeccalexanaturalist

iNaturalist Profile – https://www.inaturalist.org/people/rebeccalexa

Finally, if you like what I’m doing here, you can give me a tip at http://ko-fi.com/rebeccathenaturalist

#Wy'east#Mt. Hood#Oregon#Pacific Northwest#PNW#backpacking#through hiking#hiking#nature#nature photography#mountain#Cascade Mountains#landscape#landscape photography#Tell a Friend Friday#volcano#geology#PCT#Pacific Crest Trail

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Basalt, Palouse Falls State Park, Washington, 2016.

#landscape#geology#basalt#canyon#palouse falls state park#franklin county#washington state#2016#photographers on tumblr#pnw#pacific northwest

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

had a field trip this weekend to the coast ⚒️

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

#2655

“I Am Cascadia”

I am the battle of Thunderbird and Whale.I am the fierce daughter of Gaia.I am a sister of the Ring of Fire, along with Mariana, Sunda, and Atacama.I am the mother of mountains, of Tahoma and Lawetlat’la.I am Cascadia.

I am the place where continents collide, heavy oceanic crust drawn inexorably beneath the looming bulk of western North America. I have existed for two hundred…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#oregon#terroir#soil type#wine grape#viticulture#soils#volcanic#jory soil#loess soil#windbourne soil#marine sedimenteary#geology#rocks#washington#pacific northwest#wine#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

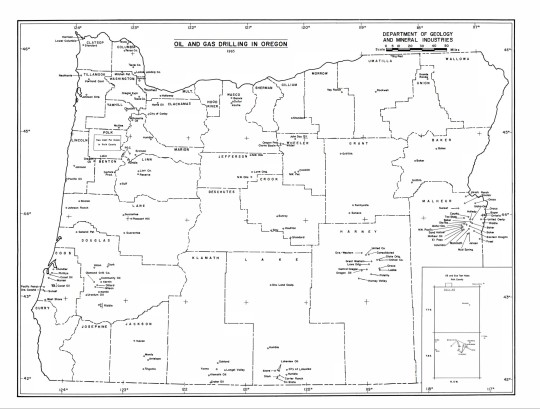

Oil and Gas Exploration of Harney Valley - 1909 to 1960

Exploration for oil and gas occurred in roughly a 50 year time period.

#harney county#harneycounty#burns oregon#oregon#eastern oregon#oregonoutback#oregon outback#oil#exploration#the great pnw#the pacific northwest#the old west#geology#oil and gas

0 notes

Text

watching this geology professor on youtube explain how the cascade mts in the us pacific northwest are going to go away eventually and become ghost volcanoes in 10 million years when the plates shift and their access to magma is cut off, and i just. love the way he’s detailing all these effects as if he and some of his viewers are in fact going to be around in 10 million years to see it. “yes we’re going to lose the cascades and the volcanism will stop - but then we’ll have new problems when we get our own version of the san andreas fault, just like california. and the cascades are going to leave some really great granite to climb on!” ok good? i’ll look forward to that?

#something something geology sure gives you a perspective on time i think#anyway i have been learning information for hours now i love plate tectonics <3 and glaciers <3#and the particular type of guy who gets so excited about all this and becomes a professor about it#geography things#cascades#skravler

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

Second Beach (Olympic National Park, Washington state) on a foggy morning. March, 2019.

#olympic peninsula#olympic national park#washington state#photography#pacific northwest#not geology#my photgraphy#pnwexplored#original photography#landscape photography#washington#pnw#pnwonderland#pnw photography#pnw vibes#fog#beach#forest#shoreline#the coast#west coast#original photography on tumblr#original

728 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Horizon

What do you think about my pic?

#Newberry National Volcanic Monument#Deschutes National Forest#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#countryside#geology#nature#flora#Deschutes County#USA#summer 2023#Oregon#Lava Flow#bush#tree#rock#Pacific Northwest#photo of the day#What do you think about my pic?#impressive landscape#grass#forest#fir#pine#woods

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

watching an incredibly good and tragically unfinished youtube documentary series explaining the geology of the pacific northwest following along the path of I90

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have been wondering, since I plan to one day grow a sustainable food forest with lots of native plants, the thought of soil came up. Is there an important role to nutritionally poor soil? I ask because to my knowledge, some plants prefer certain soils and nutritionally light soils can be found in nature. I know this won't apply everywhere, but I do know there are plants adapted to at least tolerate deficient soil. When I tried looking this up I mostly got resources about crops in relation to nutritionally deficient soil.

@localcustard - Good question! So it's not so much that the poor soil plays a particular role, as the other way around--certain plants have adapted to growing in poor soil or other harsh conditions.

One example would be pioneer species, like certain mosses, ferns, grasses, various annuals, etc. that are able to colonize recently disturbed areas that may not have very good soil. Even later arrivals like early succession shrubs and trees may be able to handle poor soil. Generally these plants are able to subsist with fewer nutrients than other species. Many of them are nitrogen fixers, meaning they cooperate with soil bacteria that draw nitrogen from the air and turn it into a form that is more accessible to plants. Often the plants will have nodules in their roots or other tissues where these bacteria live; the bacteria get a safe place to live and access to sugars the plant makes through photosynthesis, and the plants get crucial access to nitrogen.

As these plants die, the nitrogen still stored in their tissues disseminates into the soil, making it accessible to later-succession plants that cannot fix nitrogen themselves. A good example is the red alder tree (Alnus rubra), a common first-succession tree here in the Pacific Northwest. It is a nitrogen fixer, and paves the way for later-succession conifers in many forests here. Historically timber companies have sprayed alders with herbicides when they pop up a few years after a clearcut because they didn't want the alders competing with the young Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) (or whatever trees the timber people replanted with) for resources. However, more recent research shows that the conifers grow better when the alders are allowed to grow, in part due to the nitrogen, as well as connections through the soil microbiome (more about that in a minute.)

Another example of plants living in poor soil is plant communities that are adapted to harsh environmental conditions. One of my favorite examples is the plant community that lives on serpentine soil in the Klamath Mountains in southwest Oregon and northern California. Soil is made partly of organic material from various decaying life forms, but it is also composed of minerals from eroded rock. This means that the qualities of the bedrock below the soil has a big influence on soil composition.

Serpentine soils (which may also include other ultramafic rocks) generally are low in nitrogen, calcium, phosphorus, and other essential nutrients plants need. On the other hand, they frequently have high levels of iron, and often have a lot of magnesium, and heavy metals like nickel and chromium. Plants adapted to serpentine soils have had to evolve ways to deal with these additional toxins as well as a deficit of nutrients. Add in that serpentine soils are commonly found in places with harsh weather conditions and erosion, such as the Klamaths, and there's not much opportunity for the organic portion of the soils to build up. All of which means the plants native to the Klamath region are able to handle those poor soil conditions that would kill other plants.

So what does this mean for habitat restoration? Native plants are already adapted to the soils they evolved on for thousands or even millions of years. Some restorers actually discourage amending the soil where you're planting because aggressive invasive and other non-native plants will take advantage of the additional nutrients and out-compete the native species. Many native plants will grow just fine in amended soil; you just need to make sure to prepare to do some weeding as well. But it does mean that if your natural soil type has low in certain nutrients, you don't need to necessarily amend with those nutrients in order to make your native plants happy.

For myself, if I am starting native plants in pots I will give them a good 50-50 soil-aged manure mix to give them a good head start, and add a little into whatever hole I plant them in in the ground later on to give them a chance to adapt to the new soil. I still have to do a lot of weeding, but that's because I've chosen not to just totally annihilate all the non-natives with herbicides before planting. I also live in a fairly rural area with young, sand-based soil that is pretty close to its original form, so planting native species found in my area already goes pretty well as long as I'm also respecting each plant's need for sun, water, wind exposure, etc.

What you might consider is getting your soil tested to see what's in there. Often in places that have been changed over to agriculture, housing, and other development for many years, the soil has been significantly changed from its original form. It doesn't mean that you can't plant in soil that is heavily altered, but it's at least good to know, if you're going to amend the soil at all, what's already abundant and what's scarce.

Finally, I want to add in a quick note about the soil microbiome. Well-established soil has multiple layers of microorganisms, fungi, and other living beings in it, with different communities at different depths. Many of these will be species that native plants have interrelationships with (for example, mycorrhizal fungi that share nutrients with plants through the mycelium-root matrix.) When I am planting I try to disturb the soil as little as possible; rather than turning over an entire area of soil, I only dig where I'm going to be planting starts and other established plants so that the soil microbiome surrounding that hole can recolonize where I've disturbed it through planting. That soil microbiome is crucial to a plant's ability to handle poor soil, because it helps the plant to access what nutrients are available.

If you want to dive in deeper, a couple books relevant to the topic at Geology and Plant Life: The Effects of Landforms and Rock Types on Plants by Arthur R. Kruckeberg, and Savannas, Barrens, and Rock Outcrop Plant Communities of North America by Anderson, Fralish, and Baskin. Both are academic-level texts so they aren't casual reading, but they have a lot of good information relevant to how geology affects soil, to include nutrient-poor soils.

#localcustard#plants#botany#soil#ecology#gardening#habitat restoration#geology#permaculture#nature#naturecore#rocks#stones#serpentine#minerals#PNW#pacific Northwest

142 notes

·

View notes

Photo

View Across the Snake River to Whitman County, Clarkston, Washington, 2022.

#landscape#river#hills#geology#power lines#railroad#clarkston#asotin county#whitman county#washington state#2022#photographers on tumblr#pnw#pacific northwest

27 notes

·

View notes