#ocean warming

Text

By Julia Conley

Common Dreams

April 25, 2023

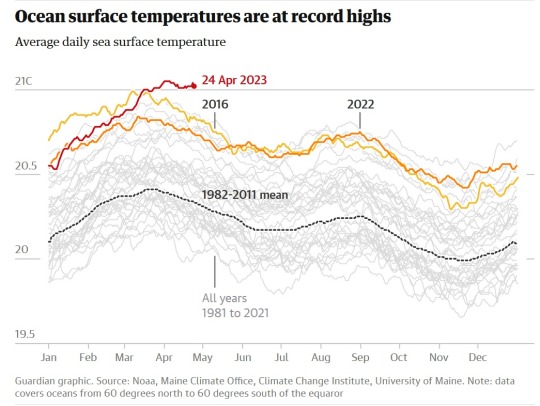

Scientists are so alarmed by a new study on ocean warming that some declined to speak about it on the record, the BBC reported Tuesday.

"One spoke of being 'extremely worried and completely stressed,'" the outlet reported regarding a scientist who was approached about research published in the journal Earth System Science Data on April 17, as the study warned that the ocean is heating up more rapidly than experts previously realized—posing a greater risk for sea-level rise, extreme weather, and the loss of marine ecosystems.

Scientists from institutions including Mercator Ocean International in France, Scripps Institution of Oceanography in the United States, and Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research collaborated to discover that as the planet has accumulated as much heat in the past 15 years as it did in the previous 45 years, the majority of the excess heat has been absorbed by the oceans.

In March, researchers examining the ocean off the east coast of North America found that the water's surface was 13.8°C, or 14.8°F, hotter than the average temperature between 1981 and 2011.

The study notes that a rapid drop in shipping-related pollution could be behind some of the most recent warming, since fuel regulations introduced in 2020 by the International Maritime Organization reduced the heat-reflecting aerosol particles in the atmosphere and caused the ocean to absorb more energy.

But that doesn't account for the average global ocean surface temperature rising by 0.9°C from preindustrial levels, with 0.6°C taking place in the last four decades.

The study represents "one of those 'sit up and read very carefully' moments," said former BBC science editor David Shukman.

Lead study author Karina Von Schuckmann of Mercator Ocean International told the BBC that "it's not yet well established, why such a rapid change, and such a huge change is happening."

"We have doubled the heat in the climate system the last 15 years, I don't want to say this is climate change, or natural variability or a mixture of both, we don't know yet," she said. "But we do see this change."

Scientists have consistently warned that the continued burning of fossil fuels by humans is heating the planet, including the oceans. Hotter oceans could lead to further glacial melting—in turn weakening ocean currents that carry warm water across the globe and support the global food chain—as well as intensified hurricanes and tropical storms, ocean acidification, and rising sea levels due to thermal expansion.

A study published earlier this year also found that rising ocean temperatures combined with high levels of salinity lead to the "stratification" of the oceans, and in turn, a loss of oxygen in the water.

"Deoxygenation itself is a nightmare for not only marine life and ecosystems but also for humans and our terrestrial ecosystems," researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said in January. "Reducing oceanic diversity and displacing important species can wreak havoc on fishing-dependent communities and their economies, and this can have a ripple effect on the way most people are able to interact with their environment."

The unusual warming trend over recent years has been detected as a strong El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is expected to form in the coming months—a naturally occurring phenomenon that warms oceans and will reverse the cooling impact of La Niña, which has been in effect for the past three years.

"If a new El Niño comes on top of it, we will probably have additional global warming of 0.2-0.25°C," Dr. Josef Ludescher of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research told the BBC.

The world's oceans are a crucial tool in moderating the climate, as they absorb heat trapped in the atmosphere by greenhouse gases.

Too much warming has led to concerns among scientists that "as more heat goes into the ocean, the waters may be less able to store excess energy," the BBC reported.

The anxiety of climate experts regarding the new findings, said the global climate action movement Extinction Rebellion, drives home the point that "scientists are just people with lives and families who've learnt to understand the implications of data better."

Read more.

#climate change#global warming#ocean warming#ocean acidification#deep ocean currents#degradation of ecosystems#ocean deoxygenation

966 notes

·

View notes

Text

“So I was pleasantly surprised when I met the leaders of Running Tide earlier this month. Far from having a hippie-dippie-ish enthusiasm about kelp, they spoke like engineers, aware of the immense scale of carbon removal that stands before them. While much of Running Tide's science remains unvetted, the researchers seem to be thinking about all the right problems in all the right ways—approaching carbon removal as an organization-level problem rather than a one-off process.

At its core, carbon removal is “a mass-transfer problem,” Marty Odlin, Running Tide’s CEO, told me. The key issue is how to move the hundreds of gigatons of carbon emitted by fossil fuels from the “fast cycle,” where carbon flits from fossil fuels to the air to plant matter, back to the “slow cycle,” where they remain locked away in geological storage for millennia. “How do you move that?” Odlin said. “What’s the most efficient way possible to accomplish that mass transfer?” The question is really, really important. The United Nations recently said that carbon removal is “essential” to remedying climate change, but so far, we don’t have the technology to do it cheaply and at scale.

Odlin, who comes from a Maine fishing family and went to college for robotics, founded Running Tide in 2017 on the theory that the ocean, which covers two-thirds of the planet’s surface, would be essential to carbon removal. At least for now, the key aspect of Running Tide’s system is its buoys. Each buoy is made of reclaimed waste wood, limestone, and kelp seedlings, materials that are meant to address the climate problem in some way: The wood represents forest carbon that would otherwise be thrown out or incinerated, the limestone helps reverse ocean acidification, and, most important, the kelp grows ultrafast, absorbing carbon from the land and sea. Eventually, the buoy is meant to break down, with the limestone dissolving and the wood and kelp drifting to the bottom of the seafloor…”

#climate change#climate crisis#carbon removal#solarpunk#carbon sequestration#ocean warming#kelp#ocean acidification#ocean ecology#carbon cycle

539 notes

·

View notes

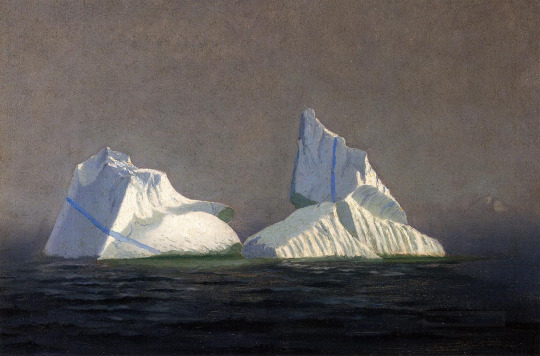

Photo

William Bradford - Arctic and maritime paintings of polar ice, icebergs and the North Pole. Alas… another fast vanishing world.

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Underwater Climate Refuges: Designing Technological Sanctuaries to Protect Marine Biodiversity from Warming

As our oceans face unprecedented warming due to climate change, the urgency to protect marine biodiversity has reached a critical point. With ecosystems and species at risk, innovative solutions are emerging to preserve our oceans’ richness for future generations. Among these transformative ideas are underwater climate refuges—cutting-edge technological sanctuaries designed to shield marine life…

View On WordPress

#3D Printing#autonomous robots#climate change#climate change action#conservation#coral bleaching#coral reef restoration#eco-friendly#ocean conservation#ocean ecosystems#ocean health#ocean warming#sustainability

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heat stress from global heating could lead to impaired vision and increased deaths of pregnant mothers and their unborn young, Australian researchers say

Octopuses could lose vision and struggle to survive due to heat stress by the end of the century if ocean temperatures continue to rise at the projected rate, a new study has found.

While previous research has suggested octopuses are highly adaptable, the latest research found heat stress from global heating could result in impaired eyesight and increased deaths of pregnant mothers and their unborn young.

The researchers said loss of vision would have significant ramifications for octopuses as they are highly reliant on sight for survival. About 70% of the octopus brain is dedicated to vision, and it plays a crucial role in communication and detecting predators and prey.

Researchers exposed unborn octopuses and their mothers to three different temperatures: a control of 19C, 22C to mimic current summer temperatures, and 25C to match projected possible summer temperatures in 2100.

Octopuses exposed to 25C were found to produce significantly fewer proteins responsible for vision than those at other temperatures.

“One of them is a structural protein found in high abundance in animal eye lenses to preserve lens transparency and optical clarity, and another is responsible for the regeneration of visual pigments in the photoreceptors of the eyes,” Dr Qiaz Hua, a recent PhD graduate from the University of Adelaide’s School of Biological Sciences and the study’s lead author, said.

continue reading

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tornado Quest Top Science Links For October 28 - November 4, 2023 #science #weather #climate #hurricane #health

Greetings everyone. Thanks for stopping by. With a few weeks left in the Atlantic and Pacific hurricane season I will continue with hurricane preparedness information that you’ll find helpful. There are other interesting reads this week, so let’s get started.

There’s a joke in here somewhere. “China’s spy-hunting campaign has a new target: ‘Illegal’ weather stations.”

In our warming planet,…

View On WordPress

#china#climate#climate change#climate crisis#climatology#disasters#drought#drought monitor#earth science education#education#emergency kit#environment#health#hurricane#hurricane preparedness#hurricane safety#meteorology#natural disasters#ocean warming#public health#science#science education#us drought monitor#weather

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ocean

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

#sustainable#environmental justice#south pacific#pacific islander#pacific islanders#climate activism#climate heal#climate action#global boiling#oceans#sea life#sealovers#ocean warming#coral#water is life#water#ocean conservation#wildlife

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Melting ice in the Arctic.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read the article.

127 notes

·

View notes

Link

Excerpt from this story from Inside Climate News:

The slowdown of a key ocean current could release methane that is frozen in layers of organic seabed sediments along some of the world’s coastlines, a new study shows.

Cold temperatures and high pressure on sea floors currently sequester about one-sixth of the world’s methane, a potent but short-lived greenhouse gas, in an ice-like form called methane hydrate, or clathrates. Sudden thawing of those clathrates could result in a surge of methane emissions that would spike the planet’s fever. The new research, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that some of the shallower layers in the Atlantic Ocean could be more vulnerable than previously thought to warming that could release that methane, and that such events have happened in the distant past.

The trigger for such warming and thawing, according to the study, is a large inflow of fresh, frigid water from melting Arctic ice, which can disrupt the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Current, a slow ocean heat pump, pushing cold water in the Arctic deep down and southward, and warm water to the surface and northward.

Temperature, density and salinity contrasts drive the pump. But in recent decades, the influx of water from rapidly melting Arctic ice, especially the Greenland Ice Sheet, appears to be weakening the current, which could warm the ocean at depths of 300 to 1,300 meters to destabilize methane hydrates buried 20 to 30 feet deep in the seabed.

It’s happened before, said University of California, Santa Barbara climate scientist Syee Weldeab, who led the detailed analysis of ocean and coastal conditions in the Gulf of Guinea. The study covers a 500-year slice of time during the Eemian Age, about 125,000 years ago.

The global average temperature was about 1 to 2 degrees Celsius warmer than now, due to changes in the amount of sunlight reaching Earth. The new study’s analysis of trace elements in the shells of ancient ocean microorganisms shows that was enough to free some methane from its icy state, he said.

The main message of the study is that researchers need to consider temperature changes greater than they are currently looking at, Weldeab said, due to the possibility of unexpected feedbacks that can magnify warming like changing currents or methane releases brought on by higher temperatures.

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Temperatures in the Mediterranean are going up 20% faster than the global average, with sea level rise expected to exceed 1m (3.3ft) by 2100. Rising temperatures mean that arrivals from warmer oceans can survive in increasingly large areas of the Mediterranean, where just a few decades ago the waters would have been too cold for them. Where native species are already under pressure from intensive fishing, invasive species can expand all the more readily.

Aïda Delpuech, ‘The crab invading the Mediterranean Sea’, BBC

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ocean Warming Hits New High

A recent paper (Cheng et al. Adv. Atmos.Sci., 2024) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00376-024-3378-5 produced an alarming piece of information: in 2023 the ocean heat content of the upper 2000 metres of the Earth’s ocean was 15 + 10 ZJ greater than the same in 2022. What that means is the Earth’s oceans absorbed 1.5 times 10^22 Joules more in one year. That is real global warming. The…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

El Niño's prolonged presence in Mexico's Pacific waters intensifies global warming, elevating hurricane risks. Coral reefs face unprecedented bleaching, with 80-100% loss. Ocean warming disrupts bacterial processes, posing threats to coastal areas.

0 notes