#masterofrecords translates

Text

The Ravages of Time episode 6

After so long, it's finally here! This was a lot of work for something that maybe two and a half people will read, but I had a lot of fun with it and am ridiculously proud of everything I've learned working on this.

Episode 6

I say Lü Bu is not human

Lü Bu, courtesy name Fengxian, was a famous general of the late Eastern Han dynasty, a skilled horseback archer and a brave and experienced warrior.

Lü Bu was appointed a Registrar by the Bingzhou governor Ding Yuan [1], but later killed him and became Dong Zhuo’s sworn son [2], acting as the official in charge of the imperial palace security, then grew suspicious of Dong Zhuo, and killed him with the help of the Minister over the Masses Wang Yun [3]. He then tried to join Yuan Shu [4], but was refused, and instead turned to Yuan Shao [5], only to again be met with suspicion, and later joined Zhang Yang [6]. After that, Lü Bu and Cao Cao opposed each other for two years. Lü Bu was also occasionally allies, occasionally enemies with Liu Bei, creating the story of Lü Bu shooting the halberd [5].

On the third year of Liu Xie’s third reign (should be around 199 CE), after Lü Bu defeated Liu Bei and Xiahou Dun [6], Cao Cao personally went on a campaign against him. There was a rebellion in Lü Bu’s forces, and he was defeated and taken prisoner. Cao Cao had Lü Bu executed.

---

Readmore here because there are so many notes...

[1] Ding Yuan – a warlord who was summoned to Luoyang alongside with Dong Zhuo to assist in the power struggle against the eunuchs, but arrived slightly later. According to the Records of the Three Kingdoms, he was originally from a poor family and rose to power through his bravery and sense of responsibility. Just like Lü Bu, he was a skilled rider and archer.

[2] Sworn son – typically translated as “adopted son”. However, I wanted to dive a little deeper into the nature of their relationship – see this post on the matter.

[3] Wang Yun – a Han dynasty official and politician known mostly for his part in Dong Zhuo’s murder. That was the height (at the time he was the Minister over the Masses – one of the three highest posts in Han dynasty) and the end of his career – within a few months, he was assassinated by Dong Zhuo’s followers in Chang’an.

[4] Yuan Shu – a Han dynasty warlord with an admittedly long and curious biography that won’t all fit here – besides, he’ll be an active participant in the events I assume will make it into the donghua. For now, after Dong Zhuo fled Luoyang, Yuan Shu came into the possession of the Imperial Seal, given to him by his subordinate Sun Jian.

[5] Yuan Shao – another Han dynasty warlord and another active participant in the Late Han politics. He and Yuan Shu did not have a good relationship, partially due to the circumstances of Yuan Shao’s birth. Now this is where things get complicated. English Wikipedia will tell you that he was Yuan Shu’s half-brother, but that’s… not really known, and under the circumstances, I don’t think any certain claims can be made. Yuan Shao was the son of a servant, and later adopted by Yuan Shu’s uncle Yuan Cheng who had no heirs (he is referred as just Yuan Cheng’s “son”, and if you’ve read the “sworn sons” post, looks like it was one of those relationships that gave him the family name and the right to inherit). Either way, despite the shady circumstances of birth, his status was higher than that of Yuan Shu’s, which didn’t stop Yuan Shu from claiming Yuan Shao wasn’t a “true” Yuan when they had disputes. Family.

[6] Zhang Yang – this Han dynasty general didn’t die by Lü Bu’s hand, but he was murdered by a subordinate a few years later while trying to help Lü Bu in his struggle against Cao Cao. He was described as a brave warrior, but wasn’t as involved in court politics as Yuan Shu or Yuan Shao. From what I’ve read in his biography, it almost sounds like politics was happening to him and not the other way around – he was mostly kept out of real power by the people in charge, even when they recognized his talents and contributions.

[7] The story of Lü Bu shooting the halberd is a famous story from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Basically a feat of unmatched marksmanship, but more on that later.

In chapter 16 of the novel, Lü Bu gets caught between two opposing forces of Liu Bei and Ji Ling (Yuan Shu’s general). Ji Ling, who had helped Lü Bu previously, was threatening Liu Bei, and Liu Bei, despite the reservations of his allies, decided to turn to Lü Bu for help. Not wanting to directly oppose Ji Ling and yet also not wanting him to win and gain more strength, Lü Bu called the two of them to his camp to settle things. While Liu Bei was eager to reach a peaceful solution, Ji Ling was intent on fighting. Finally, Lü Bu asked for his halberd, had it set in the ground 150 paces away and made a deal with the two that if Lü Bu could shoot the small blade from a bow, they’d leave peacefully. Certain that the task was impossible, Ji Ling agreed, Lü Bu shot the halberd, and thus the matter was temporarily resolved.

Now, just to put things into perspective, 150 paces is… a lot. To the best of my knowledge, during Han dynasty that would have been around 200 meters (650 feet) (even more if we assume the early Ming dynasty measurements of the time of the writing, that would be about 240 meters (790 feet)). Just… that’s an insane distance for archery. In modern Olympic archery (with the fancy bows and equipment), the largest distance for a recurve bow is 70 meters (230 feet). In traditional archery competitions, I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything over 40 meters (130 feet), and the typical distance is 20 meters (65 feet).

I don’t have a conclusion for this, really. Although Lü Bu is typically depicted with a halberd, there’s a reason one of his main defining characteristics is that he was an excellent archer. Of course, this is a fictional tale, but it certainly goes to show how Lü Bu was perceived.

[8] Xiahou Dun – one of Cao Cao’s trusted generals, nicknamed “one-eyed Xiahou” after he lost his eye to a stray arrow some time in the late 190’s. In historical records he is described just as a loyal and humble warrior as well as thoughtful administrator who kept the needs of the common folk in mind. The Romance of the Three Kingdoms really leaned into the whole one-eyed general thing though, describing him yanking the arrow (shot by Lü Bu in this version) out and eating his eyeball.

And now onto episode spoilers!

The song Xiao Meng sings before Dong Zhuo is unfortunately a song written for the show, since Xu Lin is a fictional character, and isn’t an actual old poem. Not sure if Guanshan Road there refers to a specific road, I haven’t been able to find a name for anything period-appropriate, so it could have just been a generic reference to a path through a mountain pass.

The official subtitles are a bit unclear in the part of Dong Zhuo’s speech where the dragon appears, because the translation… doesn’t feature a dragon? It goes something like, “A ruler will be revered by thousands of people wherever he goes. The real ruler is in our hands right now!” The actual words are more like, “Wherever he goes, he will be a dragon revered by thousands of people. This true dragon is now in our hands.”

(Additionally, having finally got around to reading at least the very beginning of the manhua, I actually get why sleeping with Dong Zhuo is absolutely not an option for Xiao Meng. It’s completely omitted in the donghua, but in the manhua Xiao Meng is in fact a eunuch.)

Pretty sure the instructor of the Imperial Guards Yuan Tai is a fictional character.

I had the funniest reaction after reaching the scene of Xiao Meng refusing Dong Zhuo, because that was the first time I fully realized the fake name is Diao Chan. The legendary beauty Diao Chan. And then I went back and rewatched episode 2. And indeed, Xiao Meng is sent to Wang Yun, Minister over the Masses, and I completely missed it then, too busy agonizing over Lü Bu’s halberd and the timelines.

It hasn’t really come up in previous notes, because it’s a fictional story used in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, but there, part of the reason for the disagreements between Lü Bu and Dong Zhuo is a woman named Diao Chan (often stylized as Diaochan), Wang Yun’s daughter.

Actually, Diao Chan as Lü Bu’s wife appeared in previous stories, too, the depictions ranging from a woman completely unaware of the surrounding conspiracies to a femme fatale. But I think it was the Romance of the Three Kingdoms that established her connection to Wang Yun and sets Diao Chan as Dong Zhuo’s concubine that Lü Bu falls in love with.

Obviously that’s not what happens in The Ravages of Time, but that story was still clearly a source of inspiration. Though now I have to wonder, with Xiao Meng exposed, will Wang Yun’s involvement in the story change, or will they gloss over that part completely?..

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 50 (I know I can count on you)

<< First <Previous || Chapter 50 || Next >>

Master post

Okay, not to be That Person, but if general Qiu smiled at me like that, I’d probably go ham, too. This panel is definitely going in the inspirational folder (what can I say, I’m sucker for praise). And that marks 50 chapters translated! Maybe not too much, but a big milestone for me. Here’s to many more translations to come!

Once again, thank you to @lupintraduction for their help with this chapter!

(Also also, if you like what I do here and would like to chat or see more of the stuff I do, like perhaps bits of Tang dynasty research that never make it into the translator’s notes because there’s a lot, or maybe even glimpses of the Pathfinder games I run, my main blog is over at @masterofrecords and hopefully will become more populated soon)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

On sworn fathers and sons

As I was translating the card for episode 6 of The Ravages of Time, I came across a conundrum. The relationship between Dong Zhuo and Lü Bu is typically translated into English as “adopted father and son”, but I feel like that’s a bit misleading. It is a similar concept to the “sworn brotherhood”, with the classic example being Liu Bei, Guan Yu and Zhang Fei, but it isn’t as easily adapted into English language and Western culture.

I suppose it’s tempting to try and push a square peg into a round hole and try to find similarities between the concepts we are accustomed to and the ones we see in different cultures – I readily admit I’ve done that myself, even in the translations for The Ravages of Time, albeit for a very minor character. This approach has its merits, and certainly makes the media more accessible to the wider audience. But I think it’s at least fun and at most quite helpful to try and figure out what it really means, especially for the cases where the differences become important.

Even just looking into the history of specifically the Three Kingdoms era, there are many kinds of relationships that are distinctly different from one another, with regards to if the people involved changed surnames, had inheritance rights, as well as how they were regarded by their peers. They are all typically translated into English as “adoption”, which automatically loses some of the context provided by the specific term.

Looking into a dictionary, there are quite a few terms that can be translated as “adopted son” into English. They don’t all mean the same thing, and while some are much more likely to turn up in various media, I’m going to go over all that I’ve come across one by one. That said, there is some debate on how these terms are meant to be used and sometimes the meaning is a bit muddled even in the writings of native speakers.

I will include the more literal meanings of the terms here, mostly for convenience of referring to different words without overloading this post with Chinese characters or pinyin.

义子 [yì zǐ] – lit. “sworn/righteous” son. This is probably the most common one and the one used for Lü Bu regarding Dong Zhuo. The character 义 is also the one used in “sworn brother”, and generally “sworn son” can mean the child of a sworn brother/sister. While there are some rituals involved in recognizing someone as a “sworn son”, it is not a legal process but rather a folk tradition and therefore did not give the right to inherit.

Since “sworn sons” were often adults (like in Lü Bu’s case, for example), it wasn’t uncommon for someone to enter such a relationship specifically for the perks of getting a talented heir/powerful patron.

To better illustrate the relationship between Lü Bu and Dong Zhuo, I’ll once more turn to Records of the Three Kingdoms andBook of Later Han (the passages are almost identical in both chronicles, and I used both sources to make the translation more accurate; that said, I found the Book of Later Han version slightly easier to understand in most places) and their description of Lü Bu’s decision to kill Dong Zhuo in a conversation with Wang Yun.

"From the start, Minister over the Masses Wang Yun had a close relationship with Lü Bu, having received him kindly. After Lü Bu came to Wang Yun, he complained how Dong Zhuo had tried to kill him several times. At the time, Wang Yun and the Vice Director of the Imperial Secretariat Shisun Rui were plotting against Dong Zhuo, so he offered Lü Bu to join them. Lü Bu said, “When we’re like father and son?” Wang Yun said, “Your surname is Lü, you are not his flesh and blood. Today he didn’t have time to worry about your death, what do you mean by father and son? When he threw a halberd, did he also feel like you’re father and son?” Lü Bu then agreed to kill Dong Zhuo himself, as is described in Dong Zhuo’s biography. Wang Yun gave Lü Bu the title General of Spirited Strength [1], granted him the Insignia [2], made him a Three Dignitaries Equal [3], and gave him the Wenxian county."

[1] General of Spirited Strength – uh. Look. I kind of went with the poetic feel, but just for reference, this has been translated by Moss Roberts as “General Known for Vigor-in-Arms” and by Charles Henry Brewitt-Taylor as "General Who Demonstrates Grand and Vigor Courage in Arms"

[2] Insignia – it’s kind of… a symbol of (usually military) power? Like, you have this thing, you can command/execute/etc. people even if you technically shouldn’t have the right to do so. They were usually granted temporarily for a particular mission.

[3] Three Dignitaries Equal – someone who isn’t one of the Three Dignitaries (included Minister over the Masses – Wang Yun himself, Minister of Works and Defender-in-Chief; also known as the Three Dukes), but has all the rights of one.

(This has nothing to do with the sworn sons thing, but Shisun Rui’s title literally means “charioteering archer” despite being an administrative rather than a military position. I just think that’s neat.)

养子 [yǎng zǐ] – another common one, lit. “raised/supported” son. One difference between the “sworn son” and “raised son” is in the actual act of raising – while the sworn son is typically of age, a “raised son” is a child and needs to be looked after. In modern society, this is the word used for what we would typically consider as official adoption or fostering, and comes with full inheritance rights (the legal translation seems to be fostering, but, uh, I’m not a lawyer).

That said, the word had existed for much longer than the modern legal system; so in the more historical context this would be a bit more muddled and sometimes used almost synonymously to a “sworn son”, just with a bit more legal rights.

One famous historical example of a “raised son” is Liu Feng, who was adopted by Liu Bei. At the time, Liu Bei didn’t have a heir, but later, after his biological sons were born, he stopped regarding Liu Feng as highly as before, eventually leading to mutual resentment and Liu Bei blaming Liu Feng for Guan Yu’s death and sentencing him to death (or, more accurately, ordering Liu Feng to kill himself). Even before that though, Liu Bei’s heir was announced to be his son by blood, Liu Shan.

干儿(子)[gān ér (zǐ)]- a “nominal” son, also sometimes translated as “godson”. Is usually used as a complete synonym for “sworn son” or “raised son”, but I believe is a bit more modern and appeared with the decline in the usage of “sworn son”.

契子 [qìzǐ] – lit. “contract” son. A dialect variant of “nominal son” used in Hakka Chinese. Some Chinese-English dictionaries seem to give the meaning as “adopted son” by default, but in Chinese-Chinese encyclopedias I don’t seem to see it for dialects other than the Hakka varieties – I might be wrong though.

寄子/儿 [jìzǐ/ér] – lit. “entrusted/dependent” son. That’s the one that was probably the most confusing for me. For one, it’s used to describe a similar relationship in Japanese culture. I suspected it might be a less-used spelling of “succeeding son” (see later) – the pronunciation is the same, and some of the descriptions of the terms match – but the online consensus seems to be that “dependent son” is more synonymous to “nominal son”. Unfortunately, the search for specifics is made difficult by the existence of a Japanese manga of the same title.

假子 [jiǎzǐ] – lit. “false/fake” son. It can be used as a synonym for the previous variants, or for a son of a previous husband/wife, and seems to carry a negative undertone, sometimes used to express dislike of the person it refers to or the fact that he’s not considered by the speaker to be a “real” child of the family. In the examples I’ve seen it’s only ever been used by outsiders, not by the people actually involved.

嗣子 [sìzǐ] – lit. “inheriting” son, can confusingly also mean an heir, an official son from a wife rather than a concubine. This refers specifically to someone who is going to inherit after a person, and I believe is somewhat limited to nephews. Gaining this status meant severing the legal connection with your own parents and becoming, for all intents and purposes, your uncle’s son.

祧子 [tiāozǐ] – lit. “picked” son. Unlike the “inheriting son”, didn’t need to sever ties with their original family and didn’t need to call the uncle “father”. A bit less formal than “inheriting son” but allowed one to be counted as a member of both families essentially.

继子 [jìzǐ] – lit. “succeeding” son, similar to the previous ones, but even less strict, with this relationship not being limited to nephews. Sometimes also refers to sons of ex-husbands/ex-wives.

螟蛉/螟蛉子/蛉子 [mínglíng/mínglíngzǐ/míngzǐ] – lit. “corn earworm” (or the larvae of a bunch of insects – you know what, this isn’t a biology post, whatever. You get the point). It’s a metaphor coming from an ancient misunderstanding of how they propagated. Basically, some wasps often use the larvae to store eggs (and later as food for the hatched eggs), but people used to think that wasps didn’t have children of their own and instead “adopted” the earworms. Is used as a synonym for “sworn son” or “raised son”.

微子 [wēizǐ] – lit. something like… “a little bit” son? Used to refer to the son not from the legitimate wife. Mostly this refers to the first ruler of the Song dynasty, and I’ve never come across its “illegitimate son” meaning, much less the “adopted son” given in some dictionaries. (Fun fact for Weil specially: since the “子” character means “particle” as well as “son”, 中微子 is how neutrino is spelled.)

This is all the options I’ve found! Some are very niche or even questionable, but I wanted to be thorough and cover all the possibilities one might come across in various Chinese media.

To finish this off, with so many different ways to take a child into the family, there is also a distinct word to describe children of one’s own blood – 亲子 [qīnzǐ].

At the end of the day, especially in historical context, I think it’s important to remember that many of the relationships described above were not codified, or were only partially codified. The specific dynamic relied on the interpretation of a particular person, and as we’ve seen with some of them, could even be revoked at any moment when it no longer suited the needs of the individuals involved.

I hope this was helpful!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: Well, now that I'm finally done with episode 6 of The Ravages of Time, things should go faster on the next one.

Episode 7: Contains poetry, Records of the Grand Historian, references to the Bible and Buddhist organizations.

Me: ...ah.

#masterofrecords translates#that one's also going to be fun#i'm actually done with the translation itself but both adapting it to english and searching for references for the notes#is going to be Fun#have not been able to find a professional translation of this specific poem#and not even sure where to start looking up the buddhist assassins but i'll figure it out

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ravages of Time episode 1

Oooookay, I did a thing.

Well, not yet – so far I’ve done 3/16 of a Thing, but I think that’s enough to start posting it.

As I have mentioned several times on this blog, I’m watching “The Ravages of Time” donghua. There are official subs, but they don’t cover everything – notably, song lyrics and the cards with background information at the end of each episode remained a mystery. I like mysteries and I like digging into Chinese history. I’m sure you can figure out my problem.

The thing is that some of those cards are abridged versions of excerpts from ancient chronicles. Most of these texts have no English translations available. Those are hard to translate, even for professionals (which I am far from) – as you’d expect from over a thousand year old books.

Luckily, most cards only reference the chronicles and are written in modern Chinese.

Most references in these cards are for “The Records of the Three Kingdoms” and occasionally to “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms” – a fictionalized version of the same events – and “The Book of the Later Han” which describes the events and personas of the period predating the Three Kingdoms (Dong Zhuo rose to power in 189 and was dead in 192 (sorry for the almost 2000-year-old spoilers), while the Three Kingdoms period officially started in 220).

Episode 1

T/N: The original title for the manhua/donghua is “Fiery Phoenix Scorches the Plains”

Scorched plains afterword:

“The Records of the Three Kingdoms”, one of the Twenty-Four Histories [1], written by the West Jin dynasty historian Chen Shou, records the events of the Cao Wei, Shu Han and Eastern Wu states of the Three Kingdoms period, presented as a series of biographies and dynastic histories, and is considered the most famous of the Early Four Historiographies [2].

If you persevere and finish reading “The Records of the Three Kingdoms”, you will find that “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms” has many fabricated events.

In fact, almost none of the literary works about the Three Kingdoms period are based on real historical records.

Each author’s perspective leads to their art being created in their own versions of the Three Kingdoms.

– Mou [3]

[1] dynastic histories from remote antiquity until Ming dynasty

[2] Those include The Records of the Grand Historian, The Book of Han, The Book of the Later Han, The Records of the Three Kingdoms

[3] I’m assuming referring to Chen Mou, the author of “The Ravages of Time” manhua

---------

“The Ravages of Time” is also very much fabricated. A lot of the main characters are made-up, for one; but even regarding the general events of the story, a lot of it couldn’t have happened the way it did. (I still love the donghua though! Not to mention that there is a looong history of historical fiction in China that plays very loose with historical events. See “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms” again. This is in no way a criticism on my part, I just think this stuff is even cooler when you know the history.) I’ve come across some pretty interesting stuff on these events while researching for these translations, so I might include that in the posts for the relevant episodes. At least, I will for this episode!

Putting this under the read more for spoilers of things that happened 2000 years ago.

The prologue has the narrator describe a man with the surname Cao fearing people with the character “horse” in their name. The surname Cao is that of Cao Cao; surname Sima contains the character for “horse”. Sima Yi, indeed, was the one who had Cao Cao’s descendants lose the throne and be executed.

I’m not sure how accurate the dream is supposed to be – it is, after all, a dream. Either way, I have found no indication that Sima Yi’s death was in any way violent or memorable, or that his last years were marred by any particular madness or cruelty. He did have dreams he found disturbing in those last years when he fell ill – but they were relatively harmless ones of his political rivals being celebrated. So, if it is meant to be prophetic, it is fictional.

Remnant army also doesn’t seem to be based on any real organization.

Dong Zhuo entered Luoyang in 189. At that time, Sima Yi would be about 10 years old. Along with his older brother Sima Lang (around 18) and the rest of his family he lived in Luoyang; they only moved to Henei after Dong Zhuo started making plans to relocate to Chang’an. Due to that fact, the entire Henei storyline is understandably fictional.

Xu Lin is a completely made-up character. Whatever, he dies in the very first episode. Same for Zhao Xian (Liaoyuan Huo’s “adopted father”).

We briefly see Sima Yi’s younger siblings playing ball. Sima Yi was the second of eight brothers, nicknamed “Eight Das” because all of their courtesy names ended with the same character (Zhongda for Sima Yi, Boda for Sima Lang).

#masterofrecords translates#the ravages of time#i knoooow that i promised aquarium stuff#i fell down a rabbit hole i'm sorry#i spent so many hours translating dong zhuo's biography blurb

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ravages of Time episode 5

Well, it's been... a while. Had some questions regarding Tang dynasty administrative division and that made me come back to this episode's translation.

Next one is in the works, but might take a while. There are some things I want to focus more on for Lü Bu's episode and those might end up growing into their own separate post, lol

Episode 5

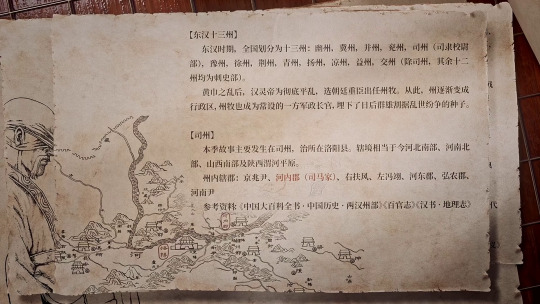

Thirteen provinces of Eastern Han dynasty

In Eastern Han period, the whole country was divided into 13 provinces: Youzhou, Jizhou, Bingzhou, Yanzhou, Sizhou (under the military rule of the Colonel Director of Retainers), Yuzhou, Xuzhou, Jingzhou, Qingzhou, Yangzhou, Liangzhou, Yizhou, Jiaozhou (apart from Sizhou, all 12 provinces were governed by a provincial governor).

After the Yellow Turban Rebellion [1], thoroughly suppressed by the Emperor Ling of Han [2], the governors were assigned by the imperial court. Since then, provinces gradually became administrative divisions and the governors also became permanent military commanders, sowing the seeds for future power struggles.

Sizhou

In the period depicted in the story, the local government in Sizhou was located in the Luoyang county. Its area of jurisdiction corresponded to present-day south of Hebei, south of Shanxi and the plains of Wei river in Shaanxi. The province was divided into counties: Jingzhao magistrate, Henei county (home of the Sima family), West Fufeng, East Fengyi, Hedong county, Hongnong county, Henan magsitrate.

Reference material: “The Encyclopedia of China – History of China – Western and Eastern Han administrative Division”, “The List of Offices”, “The Book of Han – geography section”

[1] The Yellow Turban Rebellion, also translated as Yellow Scarves Rebellion was a peasant revolt that happened in the late Han dynasty. It started in 184 CE and wasn’t fully suppressed until 205 CE, although the main uprising only lasted until 185 CE. This rebellion is also the opening event of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

While the uprising was caused by the government corruption, diseases, natural disasters and poor crops, it must be noted that it was also a Taoist sect – the leader of the rebellion, Zhang Jue, was widely known as a healer and sorcerer, and he and his brothers originally garnered supporters through their religious beliefs.

A lot of the notable people of the Three Kingdom period (like Liu Bei, Cao Cao, Sun Jian) make an appearance in that period assisting the suppression of the rebellion, and these events set the stage for the later unrest, as many regions assembled their own military forces to fight the uprising and the government’s control of the provinces weakened.

[2] Emperor Ling of Han (Liu Hong) – the emperor during whose reign the Yellow Turban Rebellion happened. A distant cousin of the previous emperor who died without leaving a son, he ascended the throne at the age of 12, and his reign saw a rise in the power of eunuchs who dominated the government. His death kicked off the events shown in the donghua.

Spoilers time!

The soldiers of the Guandong Coalition are made-up, but the first two generals they are assigned to (Han Fu and Gongsun Zao) are real people who served under the Yuan family, although Gongsun Zao turned against Yuan Shao by the end of his life). The third general mentioned, Qiao Mao, also participated in the campaign, though I think he wasn't affiliated with the Yuans.

But this isn't what you're here for. You want to know if Yuan Fang is real or not.

He's not.

As for Sun Shu, well, this one's somewhat real (although as usual, heavily fictionalized). It is known that Sun Jian had daughters, although their names aren't known. One of them later married Liu Bei, but I don't know if that happens to Sun Shu in the manhua... The other two are basically only known by who they married. My bet would be on the one who married Liu Bei though, since she was somewhat known for being fierce and a troublemaker.

I'm also not sure if the move to Chang'an was as secret as is depicted, but this is something that I think was about as dramatic as is shown in the donghua. Dong Zhuo did ransack the imperial mausoleums as well as rich households and he did burn down the city after leaving it. Anyone opposing him - before or during the move - were disposed of, and many civilians died. Even if the banquet scene likely didn't happen, I think it was cool shorthand for the events in Dong Zhuo's court leading up to the move.

#the ravages of time#masterofrecords translates#man i need to make a proper masterpost already had trouble finding episode 4 on my blog

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ravages of Time masterlist

These translations are multiplying, so I guess it's time to organize them.

Episode 1 (Introduction)

Episode 2 (Dong Zhuo)

Episode 3 (Liu Bei)

Episode 4 (Luoyang)

Episode 5 (Provinces)

Episode 6 (Lü Bu) | On sworn fathers and sons

#the ravages of time#masterofrecords translates#also fixed the formatting of the older posts#because episode 6 has too many notes for the asterisks

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ravages of Time episode 2

Oh this is… a fun one. For you, not for me, because “The Book of Later Han” doesn’t exist in an English translation. There are some excerpts out of order included in the Zizhi tongjian (Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Governance), but the relevant chapters from that have also not been translated into English, as far as I can tell. So. Uh.

I did my best with the notes available on ctext and my own knowledge; this translation is obviously less reliable than actual professional translation (like Liu Bei’s biography excerpt I will post for episode 3), but hopefully it will still provide some context. Again, I just want to impress that as far as I can tell, some parts of this excerpt have never been translated into English, and so my ability to compare notes was limited.

That said, the Dong Zhuo entry in Rafe de Crespigny’s “A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23-220 AD)” is at least partially based on “The Book of Later Han” and has been invaluable in helping me make sense of the donghua card, as has been the baidu article on Dong Zhuo that is written in much simpler language than a Han dynasty chronicle.

I’m going to suffer similarly on episode 13, I believe – the ones before are either only referenced from historical records (and seem to be modern Chinese, though I haven’t yet had the chance to take a proper look), or have translations available. Zhao Yun’s biography, however, has not been translated from what I’ve seen.

Episode 2

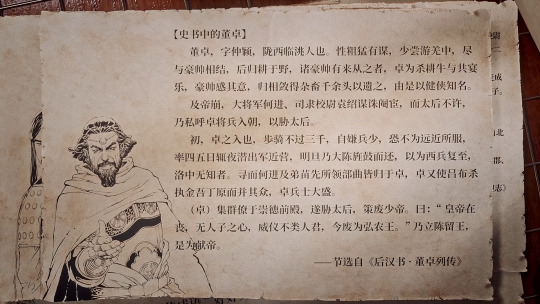

[From historical records on Dong Zhuo]

Dong Zhuo, courtesy name Zhongying, was born in Lintao county in Longxi Commandery. He had a fierce and resourceful character, in his youth spent time among the Qiang [1] and befriended many distinguished people [2]. After he returned home, many followed him, and Dong Zhuo had a lot of livestock slaughtered for a grand feast with them. His guests were impressed, and upon return, gathered a thousand heads of cattle to give him, acknowledging him as a great swordsman.

After the Emperor’s death, General-in-Chief He Jin and his subordinate officer Yuan Shao conspired to kill the eunuchs, but the Empress Dowager resisted, so He Jin ordered Dong Zhuo to bring the troops to the capital to threaten her.

When Dong Zhuo arrived, his foot and horse troops only numbered three thousand. That was too little, and in order to , Dong Zhuo for four or five days had the troops exit the camp every night, only to make a big show of them entering the next morning so Luoyang would think his army was getting reinforcements.

Dong Zhuo than took control of He Jin and his younger sworn brother Miao’s troops [3]. He also convinced Lü Bu to kill the imperial guard Ding Yuan [4]. Dong Zhuo’s army grew significantly.

Dong Zhuo gathered the officials in front of the Palace and threatened the Empress Dowager into deposing the Emperor Shao [5]. He said: “The Emperor is in mourning and has no heart, he is not fit to be the Emperor. Remove him to be the Prince of Hongnong.”

– excerpt from “The Book of Later Han” – Biography of Dong Zhuo

[1] Qiang – ethnic group from northwestern Sichuan

[2] distinguished people – not necessarily nobles, from what I understand, but usually people in power, could refer to rebel leaders or tribal chiefs, for example. I ran into a bit of a cursed loop with this word – one of the sentences used to showcase the usage of it on baidu was… the very same sentence from “The Later Book of Han” I was trying to figure out.

[3] This abridged version kinda… skips the moment He Jin and He Miao die. He Jin was killed by the eunuchs, while He Miao was killed by He Jin’s faction for sympathizing with the eunuchs. Politics.

[4] Lü Bu was Ding Yuan’s protege, but looks like that’s not mentioned in Dong Zhuo’s biography.

[5] Emperor Shao – Liu Bian

Once more, read more for 2000-years-old spoilers!

Liu Bian is depicted as a child here, but it is likely he was 17 when Dong Zhuo came. Admittedly, "The Book of Later Han" contradicts itself on this in different chapters - he could be 13.

As you can see from the above excerpt, Yuan Shao was... very much there when it happened. In fact, he and Dong Zhuo had a discussion about deposing Liu Bian in favor of Liu Xie - and Yuan Shao was against it. In the end, Yuan Shao left the city and Dong Zhuo had to be persuaded not declaring him a wanted man.

A massacre did happen, but that was before Liu Bian was deposed, it seems.

You might be wondering about Lü Bu's weapon - I certainly was. It is a ji (戟) - sometimes translated as a spear or a halberd. This is how historical ji typically look like:

This, however, is how Lü Bu is often depicted.

It seems to be a later modification? It's actually a bit confusing, in all honesty, but it's definitely used in modern martial arts. Regardless, the donghua continues the tradition of depicting the Sky Piercer this way.

In general, Lü Bu is quite a legendary character, in part thanks to his depiction in "The Romance of the Three Kingdoms". There are a lot of legends about him that we might or might not see later in the donghua, so I'll save them for now. I'll just say that his horse - Red Hare - is almost equally famous, to the point where it was said "Among men, Lü Bu; Among steeds, Red Hare."

I'm not sure if the numbers of murdered ministers and other officials has any basis; if they do, I haven't been able to find any indication of that. Dong Zhuo did use his power to have some officials executed; and there was a massacre beforehand where along with the eunuchs, many young men in the palace were killed, but the massacre depicted in the donghua seems to be greatly exaggerated.

The Sima family was indeed caught in Luoyang at the time of these events. It also seems to be true that Sima Lang was at some point arrested. His escape, however, was far less dramatic - he bribed his way out.

As for the first encounter with the legendary trio of sworn brothers - I'll leave that for the next time, when I will present to you the excerpt from Liu Bei's biography.

#the ravages of time#masterofrecords translates#stupid tumblr deleted the first version of my notes and i'm grumpy#but yes! here it is!#i finished the rough first draft of the translation for ep4 so this can come out

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ravages of Time episode 3

So at the end of this card it says “excerpt from “The Records of the Three Kingdoms” – biography of Liu Bei. “The Records of the Three Kingdoms” does have a Liu Bei chapter, but it is titled “Biography of the Former Lord” (and in the translation below he will be addressed as such, according to the original source as well as the text on the card in the donghua). There is, however, a computer game titled “The Records of the Three Kingdoms, Biography of Liu Bei”. As you can imagine, that made my search a little more complicated than it had to be.

“The Records of the Three Kingdoms” has never been fully translated into English, but there were plans to do so, that were regrettably discontinued. Still, William Gordon Crowell, who was working on the project, kindly made the otherwise unpublished completed parts of the translation public, along with his translator’s notes.

The donghua card presents an abridged version of the opening paragraphs of the chapter; I took the liberty to edit Dr. Crowell’s translation to fit the card text as well as for general readability or to bring them in accordance with the terminology I use in my other translations. I have omitted most of the notes except for the explanation on Liu Bei’s looks; I suppose the details on geography and personas mentioned there will be of little interest to most, but if you want to know more, I encourage you to look into the full translation – it is available for free and easily googlable.

Episode 3

From historical records on Liu Bei

The Former Lord was surnamed Liu and had the given name of Bei and the courtesy name Xuande. He was a native of Zhuo prefecture in Zhuo commandery, and he was the descendant of a son of Emperor Jing of the Han, Prince Jing of Zhongshan [Liu] Sheng.

The Former Lord's grandfather Xiong and his father Hong served in provincial and commandery offices. Xiong was recommended as filially pious and incorrupt, and he rose to become prefect of Fan in Dong commandery. When the Former Lord was young, he was left without a father. With his mother he wove mats to make a living. In his youth, when the Former Lord would play beneath a tree with other small children from his clan, he would say, “I must ride in this feather-covered chariot. His uncle Zijing said to him, “Don't talk so foolishly! You'll bring destruction on our house!”

When he was 15, his mother sent him to study. With his clansman Liu Deran and Gongsun Zan of Liaoxi he became a disciple of the former grand administrator of Jiujiang commandery, Lu Zhi who was from the same commandery. Liu Deran's father, Yuanqi, frequently gave the Former Lord material support. Yuanqi's wife said, “Each has his own family. How can you regularly do this?” Yuanqi replied, “This boy is in our clan, and he is an extraordinary person.”

The Former Lord did not enjoy studying. He liked dogs and horses, music, and dressing in fine clothing. He was 7 chi 5 cun (173 cm) tall, and his hands hung down to his knees. He was able to look back and see his own ears [1]. Humble before good people, he did not manifest his happiness or anger in his look. He enjoyed associating with braves, and in his youth he fought and hung out with them. The great merchants from Zhongshan, Zhang Shiping and Su Shuang, had riches of several thousands in gold. They sold horses, and they made a circuit through Zhuo commandery. They happened to see Liu and were struck by him, so they presented him with much money and wealth. With this, the Former Lord was able to assemble a group of followers.

At the end of the reign of Emperor Ling, the Yellow Turbans rose up, and every province or commandery called up righteous armies. The Former Lord led his adherents, and under Colonel Zou Jing attacked the Yellow Turban bandits with distinction. He was appointed commandant of Anxi.

– excerpt from “Records of the Three Kingdoms” – Biography of Liu Bei

[1] These physical idiosyncrasies were thought perhaps to be signs that Liu Bei had been destined to be ruler. Miyakawa Hisayuki has suggested that this description of the large ears and long arms may show the influence of Buddhist iconography from the sutras that had recently arrived in China. The size of Liu's ears, at least, appears not to have been a literary invention, for Lü Bu referred to him as the “big-eared boy.” “Looking back” and being able to see his own ears perhaps means they could be seen with his peripheral vision. The “braves” were ruffians with a code of honor, albeit one at odds with officially sanctioned moral values. Generally viewed by the government as potential threats to the social order, they were often considered heroes by the populace.

And into the spoilers we go!

Shuijing villa - Shuijing means bright, can be used in the sense of a person's brilliance. Literally means "bright as a mirror". The villa here refers specifically to a mountain villa.

I'm afraid there isn't much I can say about the Liu Bei and his companions in the context of the coalition against Dong Zhuo. It is for sure known that they participated in the campaign, but that's about it. The Romance of the Three Kingdoms popularized some fictional events of it, like the 3-vs-1 fight of the trio against Lü Bu, but I'm not sure if those will be included in this donghua. Liu Bei is described as a cunning tactician though, so I can imagine the donghua scenes happening.

Still, I'll give a bit more background info on all three. Liu Bei, Guan Yu and Zhang Fei are probably the most famous example of sworn brothers. Around the time of the Yellow Turban rebellion (more on that on another episode) they gave the famous oath in the peach garden - or at least, so the legends and "The Romance of the Three Kingdoms" say. The actual chronicles only mention the three were "as close as brothers", but the idea is still firmly ingrained in the collective conscious. There are even temples dedicated to the three of them - lit. called "Temples of the Three Righteous".

The above text only mentions he helped his mother make straw mats, but in the cut part shoes are also mentioned; as such, Liu Bei is sometimes worshiped as a god of shoemakers.

Largely thanks to the novel, Liu Bei is commonly regarded as an example of a benevolent and humane ruler, because of the author's preference for him. Considering that The Ravages of Time is mainly considering Sima Yi's point of view (and Liu Bei and Sima Yi will later lead rivaling kingdoms) I was actually rather surprised by the rather sympathetic portrayal of him in the donghua.

Still, while Liu Bei's political decisions and ruling philosophy can be discussed at length, there is no doubt that his choice of companions caused him trouble more than once.

Liu Bei was considered the eldest of the three brothers; the second was Guan Yu (courtesy name Yunchang). His life has been even more glorified than Liu Bei's - and since the Sui dynasty (581-618) he's been considered a deity. In fact, to this day, he is worshiped both in Buddhism and Taoism, as well as respected in other philosophies and religions, to say nothing of the Chinese folk tradition.

Still, despite this truly overwhelming veneration from pretty much all the following dynasties, the records say that despite his righteousness, he was "unrelenting and conceited", which proved to be his downfall..

Finally, the third brother was Zhang Fei (courtesy name Yide), whose main shortcomings - his quick temper and brutality - are the things he's most well-known for, and in a lot of ways he can be seen as the opposite of Guan Yu. While there are accounts of him composing poetry in the middle of the battle, it is by far overshadowed by his cruelty towards his soldiers and the fights he got into, sometimes dragging his sworn brothers into trouble as well.

(Just to complete the picture, yes, Zhang Fei is also sometimes worshiped along with Guan Yu.)

Regardless of all that, both Guan Yu and Zhang Fei were regarded as mighty warriors "worth a thousand men", as well as loyal followers of Liu Bei's.

---

Some final thoughts - it definitely feels like the story is playing up the future main players to keep the cast a little more manageable and maybe to put the more recognizable faces in early. Also the extra drama! It's definitely fun, so I'm not complaining XD

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have so much stuff to do that actually choosing what takes priority has been an impossible task recently, so I'm using a d12 to decide what to do, and today it seems very intent on making me go mad from the amount of Ancient China in my brains.

Started off by comparing Lü Bu's biography in different versions of the Records of the Three Kingdoms and the Records of the Later Han, on to comparing ranks of two slightly obscure Tang dynasty officials and now I'm translating chapter 141 of WCL and there's. A flashback to the Imperial Court.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I remember opening the next chapter of White Cat Legend last week, seeing the amount of (very formal!) dialogue and the titles I needed to look up and deciding that... maybe I can take a week off translations, actually.

But now I'm finally making my way through it and it's delightful - General Lang scheming is always enjoyable, and as much as Censor Lai is an asshole I adore his character (precisely because he's such a manipulative asshole - it's entertaining), so watching them go head-to-head, in the most polite and formal language I've had to translate in a while... chef's kiss.

(I'll have to think hard on how to adapt it into English best, but that's a headache for later.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, so we're a little behind on Ravages of Time, but finally watched episode 8 and I'll admit, I feel quite happy about clocking who Seven is quite a bit before the end of the episode. I love how they introduced him! Very on brand.

(Is it obvious that Zhuge Liang aka the Crouching/Sleeping Dragon is my favorite from the Three Kingdoms era? He's probably the one I read about most of all the non-Tang dynasty people)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ravages of Time episode 4

I started on this episode thinking “oh, this is going to be an easy one – it’s just a little about the city, nothing bad”. I was halfway through the first paragraph when I realized I’ll need a ton of notes to explain what all these words mean… Editing and writing the notes and fact-checking everything took me ages, haha. So. Buckle up, this is gonna be a long one, I’ll probably put the notes under the read more this time so as not to clutter everyone’s dashes.

Before getting into the translation proper, I must note that there doesn’t seem to be a lot of consistency between different sources on how to translate some terms and names here. I’ll be using the terms I like best or a literal translation if I haven’t found an established one.

Additionally, a lot of dates for the early period aren’t precise (with the uncertainty being sometimes measured in centuries) due to the lack of written sources.

Episode 4

Luoyang

Commonly shortened to “Luo”, formerly known as Luoyi and Luojing.

As the place of origin of Ancient Chinese culture, the city has great importance. It was located in the middle of the territory of Ancient China, between the Nine Provinces [1]. Over more than 5000 years of history, 13 dynasties held their capitals there. The Xia dynasty Erlitou, Yanshi Shangcheng, Eastern Zhou dynasty capital ruins, the ancient city of Han and Wei dynasties, the Sui and Tang Luoyang city were the five great capitals lined along the Luo river, known together as the “Five Capitals of the Luoyang Basin” [2], a sight rarely seen in the world. The Longmen grottoes, the Grand Canal and the Silk Road – three sites and six locations of World Cultural Heritage are situated there [3].

– excerpt from the website of the Luoyang prefecture of the People’s Republic

“Beautiful Luoyang – essential facts”

Eastern Zhou royal capital

In 1046 BCE, after Western Zhou dynasty formed, a city was built in Luoyang. The Duke of Zhou built Chengzhou and the city wall on the northern bank of the Luo river. In 1960s Western Zhou precious bronzeware was unearthed, containing inscriptions saying that the King of Zhou [4] “was the first to move his home to Chengzhou.”

In the first year of King Zhou Ping’s rule (770 BCE), the capital was moved to Luoyi (near modern-day Luoyang in Henan Province) [5], marking the beginning of the Eastern Zhou dynasty. The residence of the rightful ruler, called the Eastern Zhou royal capital, extended from the south of modern Mouth Mang to the north of the Luo river, where the Luo and Jian rivers converged. Since the 1950s the excavation of the Eastern Zhou capital city revealed the astonishing scope of the city, precise planning, exquisite construction. It is of great importance to the study of the development of Ancient Chinese capitals.

[1] Nine Provinces – the territorial divisions of ancient dynasties, also commonly refers to China of that period as a whole (the Xia and Shang dynasties period – around 2000-1000 BCE)

[2] The Five Capitals of the Luoyang Basin – over the centuries, the locations of the cities moved a little, but they all remained on the northern (sunny) bank of the Luo river. They include:

Erlitou – a bronze age (Xia dynasty – XXI-XVII centuries BCE) site where the remains of an ancient capital were found. Erlitou is the modern name of the nearest village; the city’s original name was most likely Zhenxun.

Yanshi Shangcheng (lit. Yanshi market) – an early Shang dynasty (XVI-XI centuries BCE) city. A lot of the finds from the site seem to be related to rituals or craft like pottery and bronzeware.

Eastern Zhou dynasty capital ruins – elaborated in the next paragraph, but I’ll just offer the dates for Easter Zhou: 771-256 BCE.

The ancient city of Han and Wei dynasties – again just dates, the fun parts are (or will be, I assume) in the donghua. Han (206 BCE - 220 CE) and Wei (220-266). This is the period of the donghua. “But what about the Three Kingdoms?” you might ask – Wei dynasty is one of those three kingdoms, the one where Luoyang was situated.

Sui and Tang Luoyang city – not particularly relevant for this card since it’s in the distant future. Sui (581-618), Tang (618-907). I’m not very knowledgeable about Sui, but it’s worth noting that during the Tang dynasty the capital traveled between Chang’an and Luoyang. The main capital was in Chang’an for the majority of the period, and it was the largest city of the country (about a million people), while Luoyang was known as the “Eastern Capital”. However, during Empress Wu’s reign the capital was fully moved to Luoyang.

[3] three sites and six locations – I believe refers to the Grand Canal and the Silk Roads having to multiple protected locations, most outside of Luoyang. After analyzing the maps on the UNESCO website for ages, I think there are 4 locations from the Silk Roads complex in Luoyang.

Longmen Grottoes – also Longmen caves or “Dragon’s gate grottoes”, are a complex of artificial caves carved in the limestone on both sides of the Yi river, containing over a hundred thousand of buddhist statues, and is considered one of the finest examples of buddhist art. Most are dated to Tang or Northern Wei dynasties. Was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list as “an outstanding manifestation of human artistic creativity”.

Grand Canal – a unique waterway system going from Beijing in the north to Zhejiang province in the south. It was constructed over multiple centuries from V century BCE. It connects all five main waterbasins of China, and “represents the greatest masterpiece of hydraulic engineering in the history of mankind”. Notably, the pound locks were invented to make navigation between differently elevated portions of the canal easier and safer. The total length of the canal is almost 2000 km and some portions of it are still used for transportation.

Silk Road – probably the most universally known one, this is part of the ancient roads network going from Luoyang/Chang’an to the West. The UNESCO site includes various cities, palaces, temples, tombs and various other locations built along that route across many different cultures and eras. “These interaction and influences were profound in terms of developments in architecture and city planning, religions and beliefs, urban culture and habitation, merchandise trade and interethnic relations in all regions along the routes.”

[4] Duke of Zhou or King of Zhou? Those are two different people. The King of Zhou, judging by the date, should refer to the first king of the Western Zhou dynasty, King Wu. The Duke of Zhou was his younger brother Dan, who was heavily involved in the establishment of the new dynasty (and frankly left a much bigger impression on history). This is all from a time when the rulers of the country were referred to as kings – the title of the emperor won’t appear until the establishment of the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE.

[5] The act of moving capitals was what led to the dynasty becoming “Eastern Zhou” instead of “Western Zhou”, even though the ruling family remained the same (though – as it tends to be – there was a power struggle involved). Zhou Ping is also the reason why the dynastic name of Wu Zetian’s rule was Zhou dynasty – she claimed ancestry from Zhou Ping’s youngest son.

----------------

Spoiler time! Well, not really, because most of this episode is fighting... but I still have things to say!

"It should be the Kuaiji army of Sun Jian from Jiangdong". Jiangdong - lower Yangtze area, Kuaiji - Kuaiji commandery, conquered by Sun Jian's son a few years before the events of the donghua

Unlike a lot of secondary characters, both Hua Xiong (Dong Zhuo's general) and Huang Gai/Uncle Huang (from Sun Jian's army) are real people. (Meaning you don't have to worry about Huang Gai for another... say, ten years). Not much is known about them except that they did indeed take part in the conflict between Dong Zhuo and the coalition.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally sat to translate White Cat Legend episode 4.

I'm gonna be here a while, huh?

The beginning of the episode is so confusing, and I haven't even yet got to the parts that I remember being bad. Like holy shit. This is challenging me on par with translating songs.

(I'm also beginning to regret the decision to bring over "catty lord" from the season 1 subs… It feels a bit too lighthearted in English for what's happening.)

Why am I googling middle school physics searching for the right word.

Never mind wikipedia article about artillery is my friend

Never mind again I still don't know how to word it in English

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Very, very low-energy day today (hence no WIP this time), but I did get some translations done.

I'm in for a fun time getting the author's notes ready for ch103... Can't believe I've never had to explain what jainghu is before, and a refresher on what a yaoguai is is also probably in order because ch15 was... uh... more than two years ago. Oof. Also the context of the new chapter might benefit from a more full explanation on various demonic entities and difference between them...

Oh well, future me problems!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: Oof, I managed to solve the Problem I've been puzzling over since last Friday! I deserve a break from work, let's go translate the fun WCL extra to relax

The WCL extra: Puns in a religious context

#masterofrecords translates#i do have every intention of having this extra translated on time#but it keeps surprising me

0 notes