#mary of woodstock

Text

↳ Historical Ladies Name: Mary/Marie/Maria

#mary of woodstock#mary of waltham#mary of guelders#mary of burgundy#mary tudor#mary of guise#mary i of england#mary queen of scots#marie de medici#mary princess royal#mary of modena#maria theresa of spain#mary ii of england#maria theresa#marie antoinette#mary of teck#my gifs#creations*#historicalnames*#historyedit#efoor

451 notes

·

View notes

Photo

♛ Daughters of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile

⤷ and some of their famous descendants

#historyedit#eleanor of england#joan of acre#margaret of england#mary of woodstock#elizabeth of rhuddlan#edward i#eleanor of castile#edward iv#richard iii#katherine parr#anne boleyn#henry v#mary queen of scots#perioddramaedit#gifshistorical#perioddramasource#women in history#history#my edit

416 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Mary and Elizabeth also saw their influence fade, in part because their brother's attention was normally focused on the advice of his favorites,and in part simply because they were less frequently at court. Mary continued to use her connection to the king when it benefited Amesbury - in appeals to the Pope, or in disputes between the priory and the abbess of its motherhouse at Fontevraud. And, though she was less often at court, Mary still exercised the special freedoms of movement she had always enjoyed - once her estates had been confirmed by her brother, she continued to travel to her manors, including Swainston on the Isle of Wight, where she held a sizeable house with a great hall brightened by large Gothic windows, that had been built in the thirteenth century by the Bishop of Winchester. Increasingly her energy, however, seems to have been expended in raising, educating, and safeguarding as much as she could the daughters of her sisters and nieces, including Elizabeth de Clare, Eleanor de Bohun, Joanna de Monthermer (who joined the priory at Amesbury as a fully professed nun), and Joanna Gaveston. The last of these died young while living at Amesbury, as did Mary's half-sister, Princess Eleanor, daughter of Queen Marguerite."

Daughters of Chivalry: The Forgotten Princesses of King Edward Longshanks, Kelcey Wilson-Lee

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

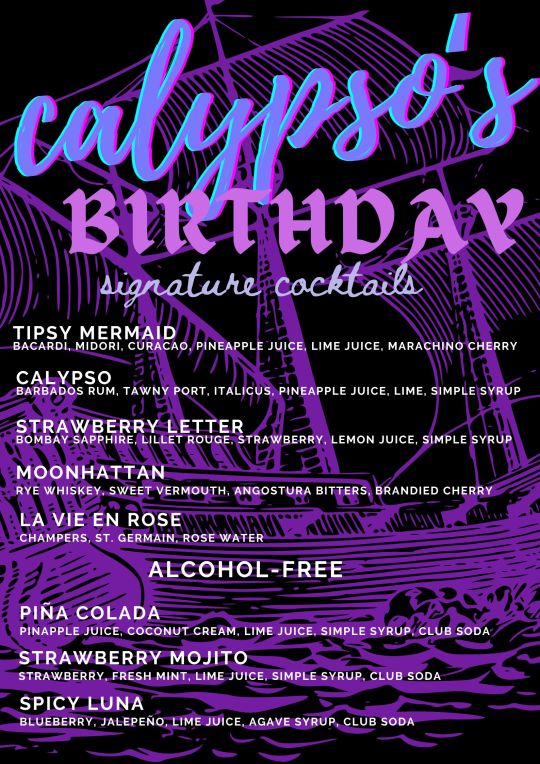

CALYPSO'S BIRTHDAY cocktails... This June Pride Month at Pearl Moon in Woodstock NY (Date TBC, will be announced in the next 24 hours). There will be dancing to an Our Flag Superfan Playlist, prizes for costumes and furthest traveled, and so so many inside jokes. Get your costumes ready and come geek out with us!

#ofmd#our flag means death#renew as a crew#renew our flag means death#renew ofmd#steddyhands#izzy canyon#gentlebeard#tealoranges#polycule#vico ortiz#jim jimenez#oluwande boodhari#samba schutte#taika waititi#rhys darby#stede bonnet#con o'neill#blackbeard#anne bonny#mary read#gay pirates#edward teach#woodstock#upstate ny#upstate new york#catskills

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Marriage of Henry of Lancaster and Mary de Bohun (1380/1)

From: Chronicles of England, France and Spain and the Surrounding Countries, by Sir John Froissart, Translated from the French Editions with Variations and Additions from Many Celebrated MSS, by Thomas Johnes, Esq; London: William Smith, 1848. *

Humphry, earl of Hereford and Northampton, and constable of England, was one of the greatest lords and landholders in that country; for it was said, and I, the author of this book, heard it when I resided in England, that his revenue was valued at fifty thousand nobles a-year. From this earl of Hereford there remained only two daughters as his heiresses; Blanche the eldest, and Isabella** her sister. The eldest was married to Thomas of Woodstock, earl of Buckingham. The youngest was unmarried, and the earl of Buckingham would willing have had her remain so, for then he would have enjoyed the whole of the earl of Hereford’s fortune. Upon his marriage with Eleanor, he went to reside at his handsome castle of Pleshy, in the county of Essex, thirty miles from London, which he possessed in right of his wife. He took on himself the tutelage of his sister-in-law, and had her instructed in doctrine; for it was his intention she should be professed a nun of the order of St. Clare***, which had a very rich and large convent in England. In this manner was she educated during the time the earl remained in England, before his expedition into France. She was also constantly attended by nuns from this convent, who tutored her in matters of religion, continually blaming the married state. The young lady seemed to incline to their doctrine, and thought not of marriage.

Duke John of Lancaster, being a prudent and wise man, foresaw the advantage of marrying his only son Henry, by his first wife Blanche, to the lady Mary: he was heir to all the possessions of the house of Lancaster in England, which were very considerable. The duke had for some time considered he could not choose a more desirable wife for his son than the lady who was intended for a nun, as her estates were very large, and her birth suitable to any rank; but he did not take any steps in the matter until his brother of Buckingham had set out on his expedition to France. When he had crossed the sea, the duke of Lancaster had the young lady conducted to Arundel castle; for the aunt of the two ladies was the sister of Richard, earl of Arundel, one of the most powerful barons of England.**** This lady Arundel, out of complaisance to the duke of Lancaster, and for the advancement of the young lady, went to Pleshy, where she remained with the countess of Buckingham and her sister for fifteen days. On her departure from Pleshy, she managed so well that she carried with her the lady Mary to Arundel, when the marriage was instantly consummated between her and Henry of Lancaster. During their union of twelve years, he had by her four handsome sons, Henry, Thomas, John and Humphrey, and two daughters, Blanche and Philippa.

The earl of Buckingham, as I said, had not any inclination to laugh when he heard these tidings; for it would not be necessary to divide an inheritance which the considered wholly as his own, excepting the constableship which was continued to him. When he learnt that his brothers had all been concerned in this matter, he became melancholy, and never after loved the duke of Lancaster as he had hitherto done.^

Notes:

* Johnes notes that this is from "only one of [his] mss. [manuscripts] and not in any printed copy". Chris Given-Wilson (Henry IV, Yale University Press, 2016): "This story comes from a variant manuscript of Froissart's chronicles used by Johnes, but subsequently destroyed by fire."

** Johnes: "Froissart mistakes: their names were Eleanor and Mary." Presumably, Johnes then corrects their names for the rest of the narrative?

*** Jennifer C. Ward (translator and editor), Women of the English Nobility and Gentry: 1066-1500 (Manchester Medieval Sources, Manchester University Press, 1995): "This is probably a reference to the convent of the Minoresses outside Aldgate in London where Isabella, daughter of Thomas and Eleanor, later became a nun."

**** Ward: "Joan de Bohun, Mary’s mother, was the sister of Richard FitzAlan, earl of Arundel." Given-Wilson argues the role Froissart assigns to Mary's aunt was actually played by Joan.

^ The veracity of Froissart's account has tended to be questioned, with some historians generally concluding there was probably some truth, mostly revolving around the falling out between John of Gaunt and Thomas of Woodstock over the marriage. The secretive nature of it is almost certainly untrue, given Gaunt had received a royal grant for Mary's marriage. Given-Wilson:

Froissart claimed that ‘the marriage was instantly consummated’, but this was precipitate. He also got several other details of the story wrong, such as calling the two sisters Blanche and Isabel and saying that it was their ‘aunt’ who carried Mary away from Pleshey, but the essentials of his story are corroborated by other sources and undoubtedly correct. Countess Joan was complicit in the plot, presumably hoping to give her daughter a life outside the convent. She probably commissioned a pair of illuminated psalters for the marriage.

The psalters were probably made by the de Bohun-sponsored workshop at Pleshey, one of Woodstock's principle residences. It's possible, presumably, that Joan commissioned them after the wedding but if they were commissioned before/finished by the time of the wedding, it's hard to imagine that Woodstock's household were entirely unaware that a move was being made to marry Mary to Henry.

#mary de bohun#henry iv#jean froissart#joan de bohun countess of hereford#eleanor de bohun duchess of gloucester#thomas of woodstock duke of gloucester#john of gaunt#primary source#froissart's chronicles

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

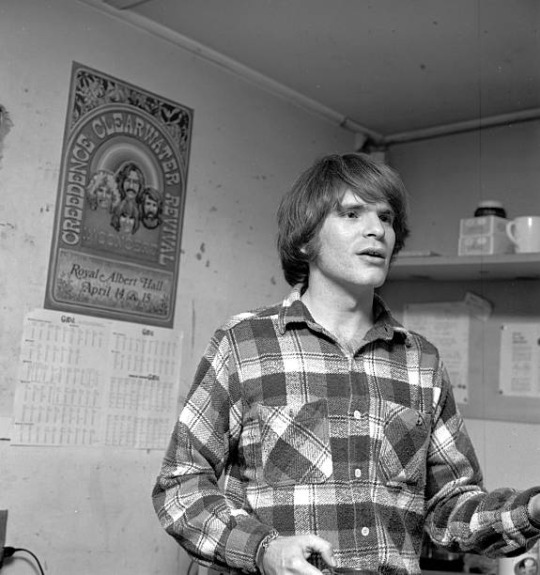

John Fogerty

#john fogerty#creedence clearwater revival#ccr#1960s#1970s#music#fortunate son#green river#proud mary#musicians#woodstock#black and white

113 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via GIPHY)

#giphy#love#music#peace#70s#60s#1960s#1970s#hippie#bohemian#hippy#woodstock#1970#1960#world peace#bellbottoms#hippie girl#mary engelbreit#maryengelbreit

79 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Princess Elizabeth was assigned the queen’s lodgings and so had a presence, privy, withdrawing and bedchamber. At first she was refused a cloth of estate in her presence chamber–both an insult and another of the multitude of ambiguities that continued to surround her situation. Guards were stationed in her watching chamber, with more in the king’s chambers at the other end. An ancient royal manor wasn’t an ideal place to confine anyone because the queen’s rooms had several staircases and many windows: Elizabeth’s jailer complained that only three doors could be securely locked. As a consequence, additional guards were stationed around the building and on the rising ground surrounding the house.

Thurley, Simon, Houses of Power, The Places That Shaped the Tudor World.

#woodstock palace#marian#did mary have a cloth of estate until late 1533? i assume so#that must have stung bcus even fitzroy had one (altho without arms...)#simon thurley

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Black Prince had received the best education available. He was taught by the scholar and astrologer Dr Walter Burghley, and was expected to excel as the future King of England. This served him well for he gleaned a sense of his own majesty from an early age: at seven he was even accoutred with his own suit of armour. Whilst his parents were in Flanders, the year before John of Gaunt's birth, the Prince opened Parliament on behalf of the King.'

Before he was ten, the Prince led an elite entourage, greeting the envoys of the Pope at the gates of the City of London (in the fourteenth century London was still encased inside a large defensive wall, with around seven gates that allowed access from north to south of the City).

Aged ten, the Prince represented his father as the head of state, and even served as head of the realm whilst Edward Ill was in Antwerp around the time of John of Gaunts birth. Thrust onto centre stage, the Black Prince's ability to work the crowd came from ample experience at a young age in the public eye. Alongside his glittering public image, the Black Prince managed extensive land and property in Cheshire and Cornwall, overseeing local administration, and cultivating loyalty from his tenants.

When John of Gaunt lived with his brother he was expected to learn the skills required for leadership military and domestic. This period of fraternal bonding forged an enduring closeness between the two boys, despite the ten-year age difference between them.

The military victories of Prince Edward were legendary. He went on to be the hero of Poitiers, and his reputation was that of a chivalrous prince, albeit an arrogant one. During the Battle of Poitiers, the Black Prince captured the French King, John II. That night, he served his royal captive on bended knee as a page.

Isabella Plantagenet, born two years after the Black Prince and named after the dowager Queen, was equally as indulged by Edward Ill as her older brother. She ran up vast debts due to her extravagant lifestyle. (…) She eventually fell in love with, and married, one of the King’s hostages from Poitiers, Enguerrand de Coucy, a French aristocrat. During the war, Councy (…) refused to fight for either England or France.

Princess Joan was five years older than John of Gaunt, followed by William of Hatfield who died in infancy, and was subsequently buried in York. His death was followed by the birth of another prince, Lionel, who would grow to be the giant of the Plantagenet family, an improbable seven feet tall according to chronicler John Hardyng. After John, came four younger surviving siblings: Edmund, Mary, Margaret and Thomas, filling the royal nursery.

Aged fourteen, Edward's ‘dearest daughter' Joan left England to marry Pedro of Castile, cementing an Anglo-Castilian alliance crucial to Edward's military agenda. As her ship drew into the harbour at Bordeaux, her retinue were unaware of the horror they were about to face: the relentless and devastating Black Death now spreading quickly throughout Europe. The royal party fled to Loremo, a small village in ordeaux, but the Princess could not outrun the disease. Joan died unwed on I July 1348, with no family around her. His sister's death had a lasting impact on John of Gaunt; in 1389 he endowed an obit - an intimate religious service - for her at the Cathedral of St André at Bordeaux, where she was buried.”

Carr, Helen. The Red Prince.

#plantagenet dynasty#plantagenets#house of plantagenet#edward iii#plantagenet#John of Gaunt#Edward the black prince#Isabella Plantagenet#Mary Plantagenet#Joan Plantagenet#Margaret plantagenet#Thomas of Gloucester#Thomas of Woodstock#Lionel of Clarence#Lionel of Antwerp#Lionel Plantagenet#John#John Plantagenet#Philippa of Hainault

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trainwreck Woodstock '99 is one of the best documentaries that netflix has put out

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

↳ the children of Edward III & Philippa of Hainault (that survived infancy)

(requested by anonymous)

#edward iii#philippa of hainault#edward the black prince#isabella of england#joan of england#lionel of antwerp#john of gaunt#edmund of langley#mary of waltham#margaret of england#thomas of woodstock#english history#house plantagenet#*requests#my gifs#historyedit#creations*

387 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Prince Noir de Marie Fauré

Le Prince Noir de Marie Fauré (©DR)

Tout le monde, surtout dans le Sud-Ouest, connait le Prince Noir. On ne compte plus les auberges, les restaurants, les lieux où a dormi le Prince. Et nous ne parlerons pas ici des forteresses censées lui appartenir, une des plus célèbres étant le « château du Prince Noir », le château de Blanquefort. Mais d’où vient ce surnom et cette célébrité ?

Le bel…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

"However, the same ties that bound most royal women together, also set them apart from Mary. The disparity cannot have escaped the regular acknowledgment of the nun, for whom daily life centered around one constant home, whose life could never involve children or husbands, and whose travel was necessarily limited. If the gulf between their experiences occasionally made Mary feel isolated from her sisters and other relatives, the feeling was never so great that the nun refused an invitation to join court and renew her association as an intimate member of the royal family. Perhaps she felt her position, free as it was from the usual expectations on royal women, was the more desirable one - certainly she never sought out opportunities, which would have been open to her, to embrace the challenge of life in a foreign land and transfer to Fontevrault, as her grandmother had intended."

Daughters of Chivalry: The Forgotten Princesses of King Edward Longshanks, Kelcey Wilson-Lee

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Ontario Slowly Recovers From Flu Epidemic,” Kingston Whig-Standard. January 18, 1933. Page 1.

----

At Present the Number Afflicted With the Disease Is Placed at Between 25,000 and 50,000

----

20 DIE OF PNEUMONIA

----

Northern Section of Province Is Suffering Worst Now — New Outbreaks — Peak Is Believed Past

----

TORONTO, Jan. 18 — Ontario slowly but surely is recovering from a mild influenza epidemic which in the past few week has spread across the province, The most conservative estimate today placed the number of afflicted at present at between 25,000 and 50,000, while at least twenty persona have died from pneumonia which followed the epidemic.

Accurate count of the present cases is impossible, doctors declared today, since many persons have either fought off the effects white continuing at work, or remaining at home had "doctored" themselves to recovery.

The northern section of the province is suffering worst at present. At Callander, nine miles from North Bay, and the surrounding Township of Himsworth, 200 cases are reported while other outbreaks were reported from Gowganda and the mines north of Elk Lake. Between five and ten per cent of Sault Ste. Marie's 18,000 residents are affected although the peak is believed past.

Ottowa health officials declared there were a "large number" of casts in that city but preferred not to make an estimate.

No schools are closed at Windsor, and the Illness was believed on the wane in that area. Three deaths on the Sarnia Indian Reserve were recorded but conditions in that area were now nearly normal. The same condition prevailed at Chatham and Woodstock. School attendance was lower than usual in the latter city but is now becoming normal.

Six Die in London

Six persons died in London during the past two weeks from pneumonia developing from the 'flu. Fears of an outbreak were dispelled by more favorable reports. Health officiate did not believe conditions were worse than in previous years.

School attendance at Kitchener was picking up and the mild epidemic occasioning no alarm at that point. Two were dead at Galt but again conditions were regarded as normal.

No definite estimate of the cases was available at Stratford but unofficially it was believed 3,000 persons were ill. Two deaths were reported from the district, but there were few cases among children.

As was the case in other communities, no estimate could be made for Toronto where it is known thousands of citizens were suffering from the mild type of flu.

#toronto#influenza#influenza epidemic#seasonal flu#epidemic histories#anti-pandemic acts#ontario ministry of health#public health#north bay#sault ste. marie#timmins#windsor#ottawa#woodstock ontario#chatham#london ontario#stratford ontario#great depression in canada

0 notes

Text

It was Gaunt who arranged Henry's marriage. The object of his attentions was Mary, the co-heiress to Humphrey de Bohun, earl of Hereford, Essex and Northampton, who had died at the age of thirty in January 1373, leaving no sons, two underage daughters, and a very substantial inheritance. The elder daughter, Eleanor (born in 1366), was married to Gaunt's brother, Thomas of Woodstock, earl of Buckingham, probably in 1374. What now happened to Mary (born in 1369–70) was naturally a matter of considerable interest to Buckingham. As long as she remained single, the entire Bohun inheritance would fall to him; were she to marry, he would be obliged to share it with her husband. Inconveniently, other duties now deflected his attention. On 3 May 1380, he indented with the king and council to lead an expedition to Brittany with a retinue of 5,000 men. During the following two months he did what he could to ensure that the Bohun patrimony did not slip from his grasp during his absence: on 8 May he obtained a royal grant of the custody of Mary's share of the inheritance during her minority; on 22 June Eleanor came of age and Thomas performed his fealty to the king for his wife's share of the lands. Shortly before leaving he even took the precaution of bringing Mary to stay with her sister at Pleshey castle (Essex), where he arranged for her to be instructed by nuns with the intention that she should join the order of St Clare. According to Froissart, ‘the young lady seemed to incline to their doctrine, and thought not of marriage’.

Hopeful of having ensured the integrity of his inheritance, Buckingham shipped his troops to Calais and, on 24 July 1380, set out with his army on a campaign from which he would not return for nine months. No sooner had he done so than Gaunt made his move. Three days after his brother's crossing, he secured a royal grant of Mary's marriage, ‘for marrying her to his son Henry’, and shortly after this induced her mother, Joan countess of Hereford, to spirit her away from Pleshey and take her to Arundel, where the young couple were rapidly betrothed. They were married on 5 February 1381 in a service held at Countess Joan's manor of Rochford (Essex). The connivance of the king and council, who would have been aware of the blow this inflicted on Buckingham, is a measure of the financial and political leverage Gaunt exercised in Richard II's minority government. Gaunt attended and presented Mary with a ruby, as well as paying for the festivities; Henry's sisters, Philippa and Elizabeth, each gave their new sister-in-law a goblet and ewer. The king and Edmund earl of Cambridge (Gaunt's younger, and Buckingham's older, brother) may also have been there, for ten royal minstrels and four of Cambridge's minstrels received gratuities from Gaunt for enlivening the proceedings. There was nothing hasty or clandestine about the wedding.

Chris Given-Wilson, Henry IV (Yale University Press, 2016)

#mary de bohun#henry iv#joan de bohun countess of hereford#john of gaunt#elizabeth of lancaster countess of huntingdon#philippa of lancaster queen of portugal#thomas of woodstock duke of gloucester#richard ii#historian: chris given-wilson#rebecca holdorph argues for an earlier wedding date iirc#also 'induced' joan to 'spirit' mary away? i don't think you could induce joan to anything she didn't want to#(ask john holland how he knows)#froissart's account of the wedding is problematic (refer to previous post) it presents the marriage as#a struggle for custody of mary between gaunt and woodstock - mary - the stolen bride - is effectively property in the narrative#(and the perspective of other women are ellided beyond the 'aunt' who abducted her who is presented as solely wanting to please gaunt)#(and the perspective of the other child/minor in the story - 13 yr old henry)#it's possible that mary did want to be a nun but it's also possible that froissart is fictionalising her perspective

7 notes

·

View notes