#library lending

Note

Hiay! You've mentioned that you're putting your audiobooks on Libby - do you mind sharing how that works for you as the author? How much does your cut differ per checkout vs per purchase?

(only if, of course, you care to share!)

So the way library lending and payment works for authors is that libraries will often pay 2x3 times what a single copy is worth in order to add it into their catalogue.

So for example with the audiobook, the customer price is set to $24.95 via Audible, but the library pays something like $40 for it. I probably should have set it higher, but I also want to incentivize libraries to buy copies so that more people can listen to it.

After that, depending on the country (not all libraries work the same) I receive a small payout every time the book is checked out. It’s not much, literal pennies in some cases, but if a book is popular enough it can add up.

Obviously, I earn more from outright individual sales, but I’m also fortunate enough that my readers are hugely supportive when it comes to getting their libraries to order my stuff and then actually follow through with checking it out. My Overdrive checks are my third highest earner each month after Amazon and Payhip. I think last month's earnings from library lending was 100-ish dollars, which is nothing to sneeze at in the slightest.

I won’t know what my earnings will look like from the audiobook via lending services until people start checking it out, but if it’s like the ebook it’ll likely fluctuate a lot and net a small amount of money each month until interest dies out.

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big Media’s lobbyists have been running a smear campaign trying to paint the Internet Archive as a greedy big tech operation bent on stealing books—which is totally absurd. If you’ve ever used the WayBack Machine, listened to their wonderful archives of live music, or checked out one of their 37 million texts, it’s time to speak up. On March 20, everyone is showing their support for the Internet Archive during oral arguments.

Here's how you can help:

The Internet Archive is our library, a massive collection of knowledge and culture accessible to anyone with an internet connection. Don't let greedy publishers burn down the next Library of Alexandria!

And if you're absolutely certain you don't use or need the Internet Archive, take a look at their projects first, you might be surprised. Those are all at risk too.

#internet archive#open library#libraries#digital lending#digital rights for libraries#digitalrightsforlibraries#hachette v internet archive

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

In Defense of Library Lending

In Defense of Library Lending

Kyle K. Courtney

The chair of Library Futures defends controlled digital lending, the practice at issue in a key copyright case.

The Hachette v. Internet Archive case has been in the press lately following the parties’ filing of summary judgment motions. But the case is not about the end of copyright as we know it, as Copyright Alliance CEO Keith Kupferschmid implied in his July 18 PW Soapbox,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

my mom: hey, you should give one of your advance copies of your novel to the neighborhood library so that you'll know they have at least one copy once the book's out

me: hang on, let me look it up just in case they already ordered one, wouldn't that be cool, haha

they, uh.

they preordered 21 copies.

granted, it's the entire library system for a large city area (ETA: and for towns kind of vaguely surrounding that), but still!

705 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#welp we made it to Last Week Tonight#libraries#public libraries#American libraries#banned books#censorship#that said i do appreciate how they highlighted that public libraries lend all kinds of useful things not just books#groomer discourse bullshit#in which people who don't read books are mad that people might read books about things they don't like#like queer people existing#or BIPOC demanding justice and human rights#and so they want to talk to the manager#tumblarians#librarians#library workers#BookLooks#Moms for Liberty#a.k.a. Assholes with Casseroles#a.k.a. Klanned Karenhood#John Oliver#Last Week Tonight#Youtube

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

When is a library not a library? When it’s online, apparently

"If you buy a physical book, you are allowed to sell or lend it because of a legal principle known as the “first sale doctrine,” which gives the owner of a (physical) object the right to dispose of that object in whatever way they wish, regardless of copyright. The Archive argued that the same principle should protect the sale or lending of a legally purchased digital copy, pointing out that all the copies of books it lent out had previously been acquired lawfully by libraries.'...

The Internet Archive’s lawyers also pointed to a Supreme Court decision, from the nineteen eighties, ruling that using a Sony Betamax video-cassette recorder to make a copy of a TV show was fair use. The Archive argued that its digital copies of print books similarly “improved the efficiency of delivering content to one entitled to receive the content” in a way that didn’t “unreasonably encroach on the commercial entitlements of the rights holder.” "

#fair use#first sale doctrine#your VCRs#your DVR#You're right to record a TV show to watch later#controlled digital lending#digital libraries#libraries#archiving#preservation#digital preservation#the internet archive#internet archive#copyright abuse

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

#columbo#season 1#death lends a hand#the squad after gettin kicked out of the library for making too much noise

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

So glad to finally see some momentum building to push back against ebook pricing models for libraries. I wish it didn't take huge libraries throwing around "we have millions of dollars" to give us any hope of change, but such is life.

I was in charge of ebook and e-audio purchasing for a small library several years ago, and can remember when they started phasing out their "one copy/one user" perpetual licensing model for popular titles. It seems the leasing model has only gotten more predatory since I left that role. Back in my day we could choose to pay a little less (but still a lot, maybe $30) for the metered access licenses, and the OC-OU licenses were the really extortionate ones but hey, as long as they continue to host that title on their platform your patrons can access it.

#librarian#libraries#public libraries#support libraries#library#public library#ebooks#digital lending#digital publishing

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

I miss Overdrive sooooo much. It was so great to have a library app that didn't crash randomly, was easy to navigate, allowed you to customize the UI, remembered where you were in your book, had decent sound quality for audiobooks, had notifications that worked, and so many other things that they just didn't bother to build into the replacement app.

#this is an anti libby blog#not because the concept is bad but because its a massive downgrade from the perfectly functional thing they had before#i will be contacting my library and asking them to terminate their relationship with the company#and focus on an in house digital lending program instead

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

do Reed's people do audiobooks and stuff also

Oh I got another ask about this and yeah! They do! It’s actually how Reed and Val meet up again after the big blowout. By that point vox and Val are a team up (velvet isn’t around yet) so when Reed sets up a meeting as a representative of the Stacks to do some business on Voxs internet it takes place at one of Val’s classier night clubs in the vip suite.

While Reed isn’t an overlord at this point he does have hella connections and the rumors of how safe the stacks are is spreading. So Val and Vox are both inclined to make a deal with the mysterious owner of the stacks.

But then the representative shows up and it’s fucking Reed???? Like to put this into Val’s l perspective: fifteen years ago your sorta boy toy was a hooker who enojoyed nothing so much as hedonism and now he’s somehow the vice president of a very powerful corporation??? Even though you were pretty sure he was dead-dead cause your hacker boyfriend couldn’t find him anywhere!

So for once it’s Val’s turn to blue screen lol.

#yrz has a lending library of digital and audio books cause they can’t be stolen stolen.#it’s not free but it’s basically chump change for hell#so pretty much everyone in pentagram city has it#and it’s starting to spread to the other rings :)#it makes Yrz a metric fuck to. of money per year btw#and more as hellborn authors start negotiating for more access#all the authors are paid fairly of course#you've got questions we've got answers#hazbin au

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Internet Archive, Misinformation & the Problem of Digital Lending

I am in the embarrassing situation of having reblogged a post with misinformation. Specifically, the "Save the Internet Archive" post featuring the below image and its associated link to a website called "Battle for Libraries".

The post claims that the recent lawsuit the IA faced threatened all IA projects, including the Wayback Machine, which is not true. The link to a petition to "show support for the Internet Archive, libraries’ digital rights, and an open internet with uncensored access to knowledge" only has one citation, which is the internet archive's own blog.

After looking for more context, I found that even articles published from sources I trusted didn't seem to adequately cover the complexity of what is going on. Here's what I think someone who loves libraries but is hazy about copyright law and the digital lending world should know to understand what happened and why it matters. I am from the U.S., so the information below is specifically referring to laws protecting American public libraries. I am not a librarian, author or copyright lawyer. This is a guide to make it easier to follow the arguments of people more directly invested in this lawsuit, and the potential additional lawsuits to come.

Table of Contents:

First-Sale Doctrine & the Economics of E-books

Controlled Digital Lending (CDL)

The “National Emergency Library” & Hachette v. Internet Archive

Authors, Publishers & You

-- Authors: Ideology v. Practicality

-- Publishers: What Authors Are Paid

-- You: When Is Piracy Ethical?

First-Sale Doctrine & the Economics of E-Books

Libraries are digitizing. This is undisputed. As of 2019, 98% of public libraries provided Wi-Fi, 90% provided basic digital literacy programs, and most importantly for this conversation, 94% provided access to e-books and other digital materials. The problem is that for decades, the American public library system has operated on a bit of common law exhaustion applied to copyright known as first-sale doctrine, which states:

"An individual who knowingly purchases a copy of a copyrighted work from the copyright holder receives the right to sell, display or otherwise dispose of that particular copy, notwithstanding the interests of the copyright owner."

With digital media, however, because there isn't a physical sale happening, first sale doctrine doesn't apply. This wasn't a huge problem back in the early 2010s when most libraries were starting to go digital because the price of a perpetual e-book license was only $14 -- about the price of single physical book. Starting in 2018, however, publishers started limiting how long a single e-book license would last. From Pew Charitable Trusts:

"Today, it is common for e-book licenses from major publishers to expire after two years or 26 borrows, and to cost between $60 and $80 per license, according to Michele Kimpton, the global senior director of the nonprofit library group LYRASIS... While consumers paid $12.99 for a digital version, the same book cost libraries roughly $52 for two years, and almost $520 for 20 years."

Publishers argue that because it's so easy to borrow a digital copy of a book from the library, offering libraries e-book licenses at the same price as individual consumers undermines an author's right to license and profit from the exclusive rights to their works. And they're not entirely wrong about e-book lending affecting e-book sales -- since 2014, e-book sales have decreased while digital library lending has only gone up. The problem, they say, is that e-book lending is simply too easy. Whereas before, e-book sales were competing with the less-convenient option of going to the library and checking out a physical copy, there is essentially no difference for the reader between buying or lending an e-book outside of its cost.

Which brings us to the librarians, authors and lawmakers of today, trying to find any solution they can to make digital media accessible, affordable and still profitable enough to make a livable income for the writers who create the books we read.

Further Reading:

1854. Copyright Infringement -- First Sale Doctrine

The surprising economics of digital lending

Librarians and Lawmakers Push for Greater Access to E-Books

Publishing and Library E-Lending: An Analysis of the Decade Before Covid-19

Controlled Digital Lending (CDL)

Controlled digital lending is a legal theory at the heart of the Internet Archive lawsuit that has been proposed as one solution to the economic issue with digital media lending. This quick fix is especially appealing to nonprofits like the IA that are not government, tax-funded programs. Where many other solutions, like a legally enforced max price on e-book licensure for public libraries, would not apply to the IA, CDL would essentially be manipulating copyright law itself as a way to avoid e-book licensure altogether and would apply to the IA as well as public libraries.

Essentially, proponents of CDL argue that through a combination of first-sale and fair use doctrine, it can be legal for libraries to digitize the physical copies of books they have legally paid for and loan those digital copies to one person at a time as if they were loaning the original physical copy.

It is worth noting that the first-sale doctrine protecting physical media lending at public libraries does not cover reproductions:

“The right to distribute ends, however, once the owner has sold that particular copy. See 17 U.S.C. �� 109(a) & (c). Since the first sale doctrine never protects a defendant who makes unauthorized reproductions of a copyrighted work, the first sale doctrine cannot be a successful defense in cases that allege infringing reproduction.”

This is where fair use comes in, which allows some flexibility in copyright law for nonprofit educational and noncommercial uses. Because the IA and other online collections are nonprofit organizations, proponents of CDL argue that they are covered by fair use so long as their use of CDL follows very specific rules, such as:

A library must own a legal copy of the physical book, by purchase or gift.

The library must maintain an “owned to loaned” ratio, simultaneously lending no more copies than it legally owns.

The library must use technical measures to ensure that the digital file cannot be copied or redistributed.

While this model first earned its name in 2018, it has been practiced by a number of digital collections like The Internet Archive’s Open Library since as early as 2010. It is important to know that controlled digital lending has never been proven officially legal in court. It is a theoretical legal practice that has passed by mostly unchallenged until the Internet Archive lawsuit. This is partially due to the fact that before releasing their official CDL statement in 2018, the IA had been honoring Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) takedown requests of books in CDL circulation, which authors claim they are not always responding to or honoring anymore. The legality of CDL essentially depends on a judge's interpretation of current copyright law and whether they see the practice as an infringement, which would set a precedent for similar cases moving forward.

There are, however, U.S. court decisions that have rejected similar cases, like Capitol Records v. ReDigi, which argues that digital files (in this case, music files) cannot be resold without copyright holder’s permission on the grounds that digital files do not deteriorate in the same way that physical media does, implying that first sale doctrine doesn’t apply to digital media.

In 2019, the Authors Guild, a group of American authors who advocate for the rights of writers to earn a living wage and practice free speech, pointed out this court case in an article condemning CDL practices. They also argued that not only does CDL undermine e-book licensure (and therefore author profits off e-book sales), but it also would effectively shut down the e-book market for older books (the market for copyrighted books that were published before e-books became popular and are only being digitized and sold now). The National Writers Union has also released an “Appeal from the victims of Controlled Digital Lending (CDL),” that cites many of the same complaints.

Further Reading:

U.S. Copyright Office Fair Use Index

Position Statement on Controlled Digital Lending by Libraries

FAQ on Controlled Digital Lending [Released by NYU Law’s Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy]

Controlled Digital Lending Is Neither Controlled nor Legal

Appeal from the victims of Controlled Digital Lending (CDL)

FAQ on Controlled Digital Lending [Released by the National Writers Union]

The "National Emergency Library" & Hachette v. Internet Archive

While the Internet Archive is known as the creator and host of the Wayback Machine and many other internet and digital media preservation projects, the IA collection in question in Hachette v. Internet Archive is their Open Library. The Open Library has been digitizing books since as early as 2005, and in early 2011, began to include and distribute copyrighted books through Controlled Digital Lending (CDL). In total, the IA includes 3.6 million copyrighted books and continues to scan over 4,000 books a day.

During the early days of the pandemic, from March 24, 2020, to June 16, 2020, specifically, the Internet Archive offered their National Emergency Library, which did away with the waitlist limitations on their pre-existing Open Library. Instead of following the strict rules laid out in the Position Statement on Controlled Digital Lending, which mandates an equal “owned to loaned” ratio, the IA allowed multiple readers to access the same digitized book at once. This, they said, was a direct emergency response to the worldwide pandemic that cut off people’s access to physical libraries.

In response, on June 1, 2020, Hachette Book Group, HarperCollins, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House filed a lawsuit against the IA over copyright infringement. Out of their collective 33,000 copyrighted titles available on Open Library, the publishers’ lawsuit focused on 127 books specifically (known in the legal documentation as the “Works in Suit”). After two years of argument, on March 24, 2023, Judge John George Koeltl ruled in favor of the publishers.

The IA’s fair use defense was found to be insufficient as the scanning and distribution of books was not found to be transformative in any way, as opposed to other copyright lawsuits that ruled in favor of digitizing books for “utility-expanding” purposes, such as Authors Guild, Inc. v. HathiTrust. Furthermore, it was found that even prior to the National Emergency Library, the Open Library frequently failed to maintain the “owned to loaned” ratio by not sufficiently monitoring the circulation of books it borrows from partner libraries. Finally, despite being a nonprofit organization overall, the IA was found to profit off of the distribution of the copyrighted books, specifically through a Better World Books link that shares part of every sale made through that specific link with the IA.

It worth noting that this ruling specifies that “even full enforcement of a one-to-one owned-to-loaned ratio, however, would not excuse IA’s reproduction of the Works in Suit.” This may set precedent for future copyright cases that attempt to claim copyright exemption through the practice of controlled digital lending. It is unclear whether this ruling is limited to the National Emergency Library specifically, or if it will affect the Open Library and other collections that practice CDL moving forward.

Further Reading:

Full History of Hachette Book Group, Inc. v. Internet Archive [Released by the Free Law Project]

Hachette v. Internet Archive ruling

Internet Archive Loses Lawsuit Over E-Book Copyright Infringement

The Fight Continues [Released by The Internet Archive]

Authors Guild Celebrates Resounding Win in Internet Archive Infringement Lawsuit [Released by The Authors Guild]

Relevant Court Cases:

Authors Guild, Inc. v. Google, Inc.

Authors Guild, Inc. v. HathiTrust

Capitol Records v. ReDigi

Authors, Publishers & You

This is where I’m going to be a little more subjective, because each person’s interpretation of events as I have seen has depended largely on their characterization and experience with the parties involved. Regardless of my own ideology regarding accessibility of information, the court ruling seems to be completely in line with current copyright law and precedent. Ironically, it seems that if the Internet Archive had not abandoned the strict rules regarding controlled digital lending for the National Emergency Library, and if they had been more diligent with upholding those rules with partner library loans prior to the NEL, they may have had a better case for controlled digital lending in the future. As is, I agree with other commentators that say any appeal the IA makes after this point is more likely to damage future digital lending practices than it is to save the IA’s current collection of copyrighted works in the Open Library. Most importantly, it seems disingenuous, and even dangerously inaccurate, to say that this ruling hurts authors, as the IA claimed in their response.

The IA argues that because of the current digital lending and sales landscape, the only way authors can make their books accessible digitally is through unfair licensing models, and that online collections like the IA’s Open Library offer authors freedom to have their books read. But this argument doesn’t acknowledge that many authors haven’t consented to having their works shared in this way, and some have even asked directly for their work to be removed, without that request being honored.

The problem is that both sides of this argument about the IA lawsuit claim to speak for authors as a group when the truth isn’t that simple.

Authors: Ideology v. Practicality

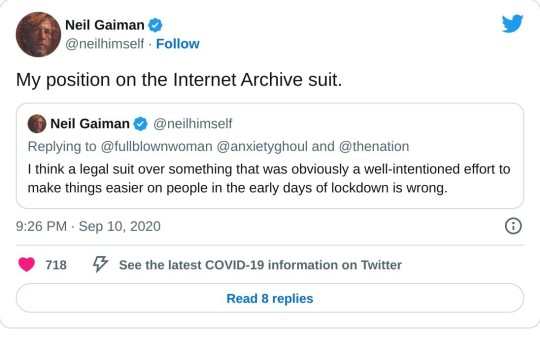

Those approaching the case from an ideological point of view, including many of the authors who signed Fight for the Future’s Open Letter Defending Libraries’ Rights in a Digital Age, tend to either have a history of sharing their works freely prior to the lawsuit (ex: Hanif Abdurraqib, who had published a free audio version of his book Go Ahead in The Rain on Spotify before Spotify began charging for audiobooks separately from their music subscriptions) or have alternative incomes related to their writing that don’t stem directly from book sales (ex: Neil Gaiman, who famously works with multiple mediums and adaptations of his writing).

In these cases, the IA lawsuit is framed as an ideological battle over the IA’s intention when releasing the National Emergency Library.

Many other authors, including a large number of smaller names and writers early in their careers, take a much more practical approach to the lawsuit, focused on defending their ability to monetarily profit off their works. This is by no means a reflection of their own ideology surrounding who has the right to information and whether libraries are worth protecting. Instead, it is a response to the fact that these authors love writing, and they simply would not be able to afford to continue writing in a world where they do not have the power to stop digital collections from distributing their copyrighted work without their consent. These include the authors, illustrators and book makes working with the Author’s Guild to submit their amicus brief in Hachette v. Internet Archive.

These authors claim that controlled digital lending practices cause significant harm to their incomes in the following ways:

CDL undermines e-book licensing and sales markets, as most consumers would choose a free e-book over paying for their own copy.

CDL devalues copyright, meaning authors have less bargaining power in future contract negotiations.

CDL undermines authors ability to republish, whether as a reprint or e-book, out of print books once their publisher has ceased production. This includes self-publishing after the rights to their work have been returned to them.

CDL removes the income from public lending rights (PLR) that authors receive from libraries outside of the U.S. which operate on different lending and copyright standards.

The amicus brief provides first-person anecdotes from authors, including Bruce Coville of The Unicorn Chronicles, about how the rights to backlisted books, or books without an immediately obvious market, make up a huge portion of their annual salary. Jacqueline Diamond cites reissues of out-of-print novels as what kept her afloat during her breast cancer treatment.

It is worth noting that according to the Author’s Guild, some authors who originally signed Fight for the Future’s open letter defending the Internet Archive have even retracted their support after learning more about the specific lawsuit, including Daniel Handler, who writes under the pseudonym Lemony Snicket. The confusion stems from the use of the term “library” by both the Internet Archive and Fight for the Future. While authors overwhelmingly support public libraries, online collections like the Internet Archive don’t always fit the same role or abide by the same regulations as tax-funded public libraries. Sandra Cisneros, author of The House on Mango Street, has written the following:

“To this day, I am angry that Internet Archive tells the world that it is a library and that, by bootlegging my books, it is simply doing what libraries have always done. Real libraries do not do what Internet Archive does. The libraries that raised me paid for their books, they never stole them.”

Further Reading:

Amicus Brief [Submitted by the Author’s Guild]

Fight for the Future’s Open Letter Defending Libraries’ Rights in a Digital Age

Joint Statement in Response to Fight for the Future’s Letter Falsely Claiming that the Lawsuit Against Internet Archive’s Open Library Harms Public Libraries [Published by the Author’s Guild]

Copyright: American Publishers File for Summary Judgment Against the Internet Archive

Publishers: What Authors Are Paid

Some of the commentators I’ve seen are disgruntled specifically with the publishers suing the Internet Archive, and I will say that many of these complaints are valid. The four publishing companies behind the lawsuits (Hachette Book Group, HarperCollins Publishers, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House) are not known for the stellar treatment of their authors and employees. With the HarperCollins Publishers strike ending only a month before the IA lawsuit ruling, many readers are poised to support any entity at odds with one or more of the “Big Five” publishers. In this particular case, however, the power wielded by these publishing companies was used in defense of author’s rights to their works, for which The Authors Guild and other similar creator groups have expressed gratitude.

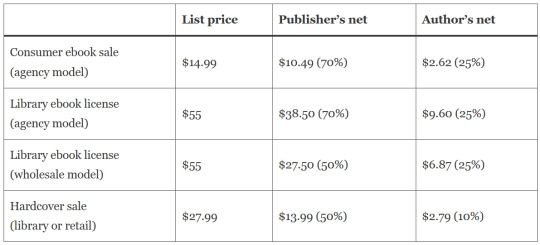

When it comes to finding solutions to the digital lending problem in general, it is important to understand what and how authors are paid for digital copies of their work. Jane Friedman has created the graphic below displaying the industry standards for the Big Five publishers. You can read more about agency and wholesome models here.

As you can see, authors and publishers alike benefit from e-book library licensure when compared to individual e-book sales, especially when you consider the time limits on library licensures. But advocates of this licensure model argue that the high prices for e-book licensure are designed to make up for the lost sales in e-books. While library goers buy more books than book buyers who don’t visit the library, the copies they buy typically vary by format. For example, a reader may borrow an audiobook from the library, decide they like it, and purchase a physical copy for their collection. While readers may buy a physical copy of a book after reading a physical library copy, they are unlikely to buy a digital copy after readying a digital library copy, making e-book lending a replacement for e-book buying in ways that physical lending doesn’t fully replace physical book purchases.

What ISN’T accounted for in this graphic is self-publication and what is known as a right of reversion. Depending on the wording of their contract, an author can request their publication rights be returned to them if the work in question is out of print and no longer being published. The publisher can then either return the work to “in print” status or return the rights to the author, who can then self-publish the work. In these cases, the 5-15% profit they would have made off their traditionally published book becomes a 35-70% profit as a self-published book. This is why authors are particularly frustrated with the IA’s argument that it is perfectly legal and ethical to release digital copies of books that are no longer in print. Those out-of-print works are where many authors earn their most reliable, long-term income, and they provide the largest opportunity for the authors to take control of their own works again and make fairer wages through self-publication.

The most obvious answer to this is that if authors are being the ones hit hardest by library and digital lending, then it is the publishers that need to treat their authors with better contracts. The fact that some authors are only earning 5% of profits on hardcover copies of their books (whether those are being sold to libraries or individuals) is eye opening. Alas, like the “we shouldn’t have to tip waiters” argument, this is much easier said than done.

Further Reading:

What Is the Agency Model for E-books? Your Burning Questions Answered

What Do Authors Earn from Digital Lending at Libraries?

You: When Is Piracy Ethical?

There are number of contributing factors to Tumblr’s enthusiasm for pirating. We are heavily invested in the media we consume, and it is easy to interpret (sometimes accurately) copyright as a weapon used by publishers and distant descendants of long-dead authors to restrict creativity and representation in adaptations of beloved texts. There are also legitimate barriers that keep us from legally obtaining media, whether that is the physical or digital inaccessibility of our local libraries and library websites, financial concerns, or censorship on an institutional or familial level. In fact, studies have found that 41% of book pirates also buy books, implying that a lot of illegal piracy is an attempt at format shifting (ripping CDs onto your computer to access them as MP3 files, for example, or downloading a digital copy of a book you already own in order to use the search feature).

The interesting thing is that copyright law in the U.S. has a specific loophole to allow for legal format shifting for accessibility purposes. This is due to the Chafee Amendment (17 U.S.C. § 121), passed in 1996, which focused on making published print material more available to people with disabilities that interfere with their ability to read print books, such as blindness, severe dyslexia and any physical disability that makes holding and manipulating a print book prohibitively difficult. In practice, this means nonprofits and government agencies in the U.S. are allowed to create and distribute braille, audio and digital versions of copyrighted books to eligible people without waiting for permission from the copyright holder. While this originally only applied to “nondramatic literary works,” updates to the regulations have been made as recently as 2021 to include printed work of any genre and to expand the ways “print-disabled” readers can be certified. Programs like Bookshare, Learning Ally, and the National Library Service for the Blind and Print-Disabled no longer require certification from a medical doctor to create an account. The Internet Archive also uses the Chafee Amendment to break their Controlled Digital Lending regulations for users with print disabilities. While applications of the Chafee Amendment are still heavily regulated, it is worth noting that even U.S. copyright law acknowledges the ways copyright contributes to making information inaccessible to a large amount of people.

Accessibility is not the only argument when discussing the morality of pirating. For some people, appreciation for piracy and shadow libraries comes from a background in archival work and an awareness how much of our historical archives today wouldn’t exist without pirated copies of media being made decades or even a century ago. But we have to be more careful about the way we talk about piracy. Though piracy is often talked about as a victimless crime, this is not always the case, and each one of us has a responsibility to critically think about our place in the media market and determine our own standards for when piracy is ethical. In some cases, such as the recent conversation surrounding the Harry Potter game, some people may even decide that pirating is a more ethical alternative to purchasing. Here are a few questions to consider when deciding whether or not to pirate a piece of media:

Have you exhausted all other avenues for legally purchasing, renting or borrowing a copy of this media?

Is the alternative to pirating this media purchasing it or not reading/referencing it at all? If the former, how are you justifying the piracy?

Who is the victim of this particular piracy? Whether or not you think the creator(s) deserve to have their work pirated, you need to acknowledge there is someone who would otherwise be paid for their work.

If every consumer pirated this media, what would the consequences be? Would you be willing to claim responsibility for that outcome?

If you got this far, thank you so much for reading! It is genuine work to try and understand the complexity behind every day decisions, especially when the topic at hand is as complicated as the modern digital lending crisis. Doing this research has changed the way that I understand and interact with digital media, and I hope you have found it informational as well.

Further Reading:

Panorama Project Releases Immersive Media & Books 2020 Research Report by Noorda and Berens

The Chafee Amendment: Improving Access To Information

National Center on Accessible Educational Materials

National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled

Books For People With Print Disabilites: The Internet Archive

Bookshare

Learning Ally

#Internet archive#IA lawsuit#digital lending#libraries#digital libraries#open library#controlled digital lending#national emergency library

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

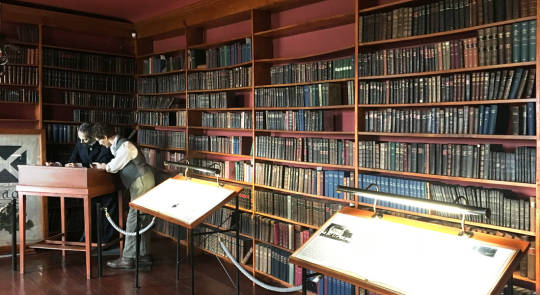

On November 1st 1756 the Wanlockhead Miner’s Library was established, the second oldest subscription Library in Scotland and indeed Europe.

It was only the second subscription library for working people to be founded anywhere in the World. It was closely modelled on the first, the neighbouring Leadhills Library, founded over ten years earlier in 1741.

Throughout the mid eighteenth and nineteenth centuries libraries like Wanlockhead flourished, it is one of the few remaining examples of a phenomenon which was once found throughout Scotland. That of the community (or subscription) library. A community library is really a sort of club. Members can join upon payment of an entry fee and afterward pay a yearly subscription. Money raised in this way was mostly fed back into the purchase of stock and gradually a permanent library is accumulated.

The founding of a library suggests that there were high levels of literacy amongst the local population. The ability of the miners to read and write can be traced back to the village school which was established by the Duke of Bucchleuch in the eighteenth century and a teacher was employed to teach local children.

The Society has a fascinating history for example it amassed a collection of around 3,717 books by 1925, although only around 2572 or around two-thirds are housed in the library today.

Having ceased to function as a working library in the early 1930s the fate of the book collection and society archives appeared sealed. However, having been looked after by villagers for a number of years, the preservation and promotion of the collection became a fundamental aim of Wanlockhead Museum Trust when it was formed in 1974. The Miner’s Library collection itself became a ‘Recognised Collection of National Significance’ in 2008. A survey of its archives was recently added to the National Records and Archives of Scotland Register.

In addition to gaining this official recognition, the Museum was also awarded £40,000 by Museums and Galleries Scotland which was used to research and promote the collection.

More about the Leadhills Museum and the library here

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's a Google Maps crowdsourcing mutual aid networks, mask blocs, air filtration donation organizations, air purifier lending libraries and other resource groups. There are over 250 groups and continuously being updated. Please contact them to submit a pin.

Here is the URL for ease of memory recalls: covidactionmap.org

For updates you can follow COVID Action Map here:

Twitter

Instagram

Apologies for excessive tagging, but wanted to make sure the post is easily discoverable by anyone on Tumblr.

#mutual aid#Google Maps#COVID-19#COVID#SARS-CoV-2#mask up#mask bloc#air filtration#donation groups#lending libraries#We Keep Us Safe#community defense#community resistance#culture of resistance#community building#community solidarity#COVID is not over#dual power#counterpower#mutual aid groups#COVID mutual aid groups#COVID mutual aid networks#mutual aid networks#pandemic solidarity#COVID solidarity#clean air orgs#clean air revolution#clean air organizations#COVID actions#COVID action

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the best thing ever and also ooh Mission Impossible 2.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyways, if you support the Internet Archive and the Lending Library has been an important part of your life, discovering new books and authors you otherwise never would have had access to due to a lack of a local public library, especially if you then went on to purchase your own copies after borrowing from the library, go up-vote the post in r/murderbot , people are trying to claim the Internet Archive is selling scans of books (?????) and "stealing from authors" by..... loaning out used books one at a time.

anyways literally all the of the Murderbot books on the Lending Library are currently being borrowed now, which means at least five different people are now reading the series and are about to get hooked! And do you know what people do when the love a book series? they buy books

Funniest thing about the anti-Internet Archive crowd is they literally acknowledge that people who read books at the library first are more likely to go out and spend money on buying personal copies, but somehow, magically (sarcasm), the IA is magically exempt from this effect.

The Internet Archive is totalllllly not how I discovered that some of my favorite childhood authors have a dragon-riding series, (Wyrmeweald, by Chris Riddell and Paul Stewart, creators of the Edge Chronicles!) , or the Beauty and the Beast novelization, or the Quantum Leap books, or the Babylon 5 novels, or even just any random book I come across while browsing the Open Library.

edit: oh and here's to make it even easier, here's the links if you want to read them yourself!

note, it's probably going to take awhile for them to be available again, with how popular they are!

1st Murderbot book: All Systems Red

the 2nd: Artificial Condition

the 3rd: Rogue Protocol

the 4th: Exit Strategy

the 5th chronologically: Fugitive Telemetry

the 6th chronologically: Network Effect

(The 7th book, System Collapse, which came out a few months ago, hasn’t been donated yet.)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

For those of you who use the Internet Archive, you may have heard that something terrible happened yesterday. A lower court ruling said that they couldn't keep scanning and loaning books! Although they plan to appeal the ruling, and while their current stock appears to be safe for now, I think we need to find a way to make sure we can still read those books (many of which are rare or out-of-print) in a place where the law won't be able to find us, at least for a while. I know how risky this would be, but unless and until the Internet Archive prevails, I don't want to lose those books. However, in order to do this, I'm going to need a lot of help, since I don't really know how to do this sort of thing. Are you with me.

#internet archive#digital libraries#controlled digital lending#piracy#book piracy#share this on twitter#i do realize how extreme this sounds#but i won't lose access to those books

68 notes

·

View notes