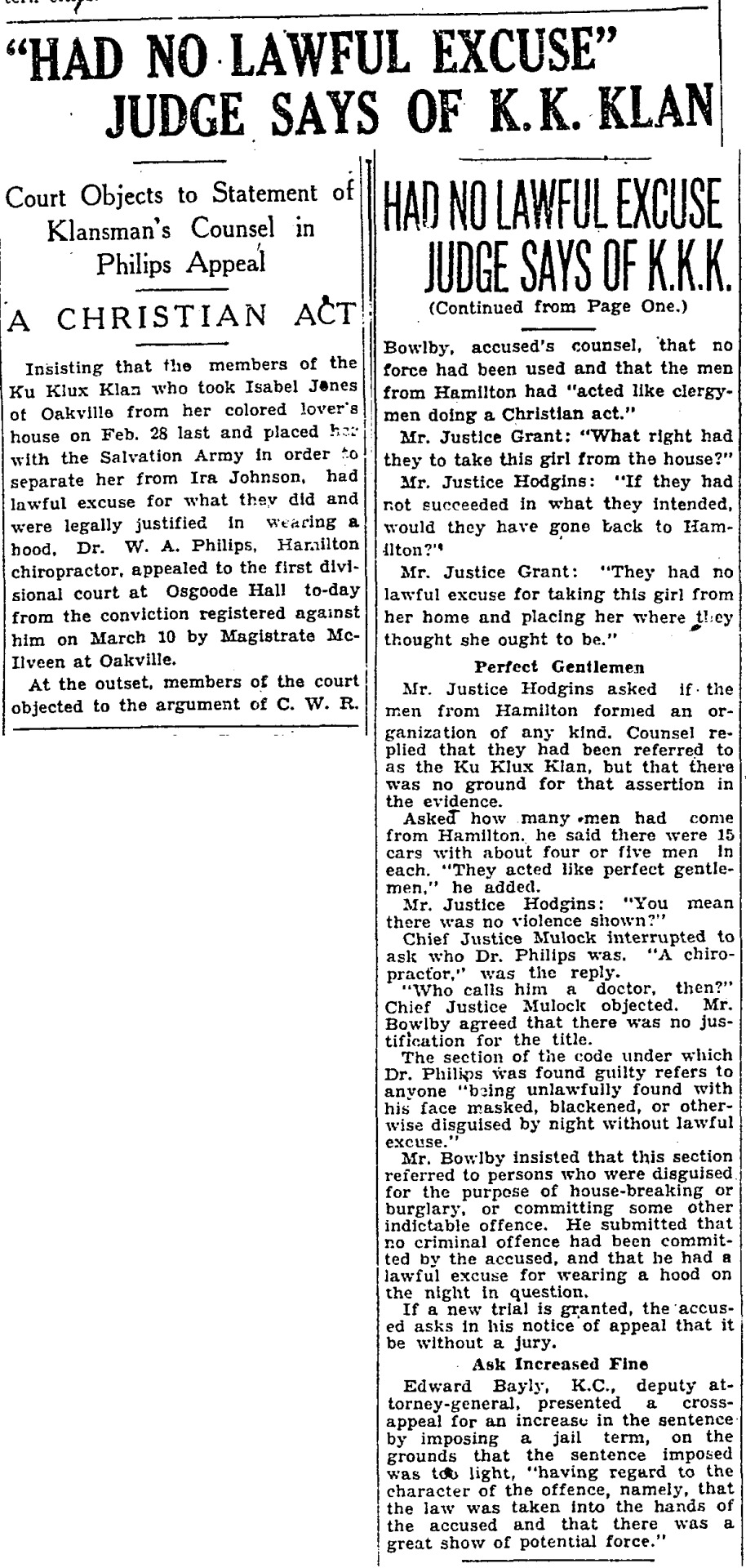

#klansman without hoods

Text

when I see people with these great big "x's" on I start thinking to myself and wondering do they not realize they are a big ass target all over their whole existence?

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Strings,” Moon Knight (Vol. 9/2021), #2.

Writer: Jed MacKay; Penciler and Inker: Alessandro Cappuccio; Colorist: Rachelle Rosenberg; Letterer: Cory Petit

#Marvel#Marvel comics#Marvel 616#Moon Knight vol. 9#Moon Knight 2021#Moon Knight comics#Moon Knight#Marc Spector#Reese#ach nO hahaha#Marc is already conflicted enough with “Jewish man running around fulfilling an Egyptian god’s mission” without adding the turmoil of#“Jewish man running around in what looks like a Klansman hood” to the mix#furthermore…it’s small but knowing that Marc can use chopsticks means a lot to me

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

“He’s a surprising figure. An avid environmentalist, fluent in Japanese and, in person, not the bitter old racist I’d expected but rather a jolly Mormon grandfather, bright eyed and chuckling, a Wind in the Willows character. Eric is even more unexpected. Tall and impassioned, he came to racism via hypnotherapy, of all things. He sells solar panels for a living and practises yoga. Together with his friends Matt and Nathan, who are also here at lunch, he runs an alt-right fraternity in Manhattan Beach. [...]

What unites Johnson and Eric is what they describe as 'the systematic browbeating of the white male’ [...]

For his part, Johnson’s racism was shaped in Japan. He grew up in Eugene, Oregon, a state founded as a white utopia, in a modest Mormon home, back before the LDS church gave black people the priesthood in 1978. But it was his two-year mission to Tohoku, Japan, that turned him. As he went from door to door, locals would opine on the greatness of white America. “They had an inferiority complex after the war, so we were treated like celebrities,” he says. 'Oh, it was just the funnest time!' A few years later, while working in Japan as an attorney, he wrote a book advocating the repatriation of all non-whites with appropriate reparations, because 'I thought America was going to collapse unless I did something.' When he returned to LA, he sent a copy to every congressman. [...]

'You’re a white supremacist with a black artist painted on your truck,' I tell him. And he flinches. 'That’s the meanest, most hurtful swearword there is. Just because I say different races have different strengths doesn’t mean I think I’m superior.' He doesn’t like 'racist' either. 'It’s a pejorative. I prefer ‘race realist’.'

'But it’s not my reality, Bill. I’m sticking with racist.'

'Well, OK. But people who embrace ‘racist’ are mad at everybody. I get along with people. You cannot function in Los Angeles without encountering other races, so I look for areas of similarity and agreement. It’s important to treat everyone with the highest respect on a micro level.'

On a macro level, however, darkness falls – multiculturalism is doomed, the different races will never get along, and our only hope is Balkanisation: separate territories for separate tribes. And whatever accelerates that transition is welcome, even racial strife. [...]

In the late 70s, the Klansman David Duke swapped his hood and robes for a suit and tie, and took white supremacy out of the cross-burning fields and into the boardroom. Mark Potok of the Southern Poverty Law Center describes the alt right in similar terms, as Racism 2.0, “a rebranding for the digital generation”. It’s a trendy reboot – “alt right” makes white supremacy sound like an art collective. And Eric, the kombucha Nazi, just takes it a step further – into the aisles of Whole Foods. He’s a locally sourced, wild-caught bigot high in omega-3s and antisemitism. It makes him more sinister in some ways, and more harmless in others. As Nazis go.

'Hmm, Nazi.' Like Johnson, he’s squeamish about terms. Warriors against political correctness can be awfully sensitive. 'It’s such a slur,' he says. But come on – he’s a Hitler apologist. ‘OK, fine,' he says. 'Just don’t say I’m a Buddhist, because I’m actually more into Norse and Celtic mysticism now.'

It’ll come as no surprise that someone who’d rather be called a Nazi than a Buddhist has a strange story to tell. Originally from a well-off white suburb of Chicago, he moved to Las Vegas to pursue music. Then one day, in the gym of his condo building, he met a guru figure we’ll call Frank. A spiritualist and businessman, Frank introduced Eric to New Age mysticism and Japanese Buddhism. And it was under Frank’s guidance that Eric moved to LA to study hypnotherapy and began a career giving readings and tarot shows at a psychic bookshop. Frank, he says, was his “mentor and best friend”. But then Eric took a turn. He radicalised himself. He left the New Age life, finding it too feminine, and spiralled down a sinkhole of conspiracy theory. He and Frank have been estranged ever since. Frank is black.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ON NOVEMBER 3, 1979, a caravan of neo-Nazis and Klansmen fired upon a communist-organized “Death to the Klan” rally at a black housing project in Greensboro, North Carolina. Five protestors died—four white men and one black woman—and many more were injured. Fourteen Klansmen and neo-Nazis faced murder, conspiracy, and felony riot charges. Although three news cameras captured the identity and actions of the Klan and neo-Nazi shooters, all-white juries acquitted the defendants in state and federal criminal trials. A civil suit returned only partial justice. The Greensboro confrontation heralded a paramilitary white power movement mobilized for violence, and also revealed a legal system broadly unprepared to convict its perpetrators.1

The shooting at the Greensboro rally was the logical extension of post–Vietnam War paramilitary culture and a series of increasingly violent clashes between the fractious radical left and the nascent white power movement. Sharing a common story of the Vietnam War, disparate Klan and neo-Nazi factions united around white supremacy and anticommunism, and sustained the groundswell by circulating and sharing images, personnel, weapons, and money. In 1979, North Carolina Klansmen had recently discovered a new leader in David Duke. His Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (KKKK), gaining momentum nationwide, had just secured a local foothold in an area with a long tradition of Klan activity and with other active Klan factions. In February, Duke himself came to Winston-Salem to screen Birth of a Nation. The 1915 film depicts Klansmen as heroically saving the South—embodied by white women threatened by interracial sex—from the ravages of blacks and northern carpetbaggers during Reconstruction.2

While neither the post–Vietnam War KKKK nor the white power movement was primarily southern, the film’s invocation of the lost Civil War had particular resonance in North Carolina. For the South, the Vietnam War was not the only American defeat at play in the popular imagination, nor the only war that needed to be reengaged. Indeed, one illustration published in the Alabama-based KKKK newspaper White Patriot portrayed a Confederate veteran standing in formation with a Vietnam War–era Green Beret and a third man wearing a Klan hood.3 At the time of Duke’s visit in 1979, the KKKK showed signs of a southern membership surge as well as openness to new alliances: people wearing Nazi armbands, for instance, attended an exhibit of Klan artifacts at a county library in Winston-Salem.4

At the same moment, an attack waged by Invisible Empire Knights of the Ku Klux Klan upon black civil rights marchers in Decatur, Alabama, modeled a Klan strategy of forming armed caravans to carry out violence.5 The Decatur altercation wounded four black demonstrators and resulted in a local ordinance prohibiting guns within 1,000 feet of public demonstrations. The Invisible Empire responded by driving a caravan of vehicles past the mayor’s house: “If You Want Our Guns, Come and Get Them,” one sign read. The local police chief made no arrests, unsure if the ordinance applied to a moving caravan of cars. The Invisible Empire, helmed by Bill Wilkinson, famously didn’t get along with several other Klan factions. Nevertheless, an increasing circulation of newspapers and other printed ephemera had begun to link these groups, and articles about the Decatur clash appeared in Klan and neo-Nazi publications as well as in the mainstream press. The incident foreshadowed the caravan of Klansmen and neo-Nazis that would gun down protestors in Greensboro months later.6

In July 1979, local members of the Federated Knights of the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party arranged another screening of Birth of a Nation. This time they chose a community center in the small, working-class town of China Grove, North Carolina, about sixty miles from Greensboro.7 Members of the Workers Viewpoint Organization (WVO)—which soon changed its name to the Communist Workers Party (CWP)—organized a rally and march in protest. A hundred self-proclaimed communists as well as black community members stormed the community center, armed with clubs. While Klansmen and Nazis stood on the porch with shotguns, a few policemen managed to keep the groups from attacking each other. The Klansmen retreated into the building as protestors damaged the structure and burned a Confederate flag.8

The scene was remarkably similar to the final sequence in Birth of a Nation, in which the southern family hides in a small cabin as the town is, as the intertitles say, “given over to crazed negroes … brought in to overawe the whites.” As the “black mob” and the carpetbaggers wreak havoc in town, tarring and feathering Klan sympathizers and attempting to force an interracial marriage, those in the cabin are trapped, hopelessly besieged, until a large cadre of robed Klansmen rescues them, accompanied by the strains of Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries.”9

No such rescue party appeared in China Grove. Klansmen experienced the protest as a direct attack. The women huddled in the bathrooms as the men defended the building, vowing revenge. Several Klansmen would later study photographs of the China Grove demonstrators to choose whom to “beat up” in Greensboro on November 3. In the moments before the fatal shooting, a news camera would capture neo-Nazi Milano Caudle murmuring “China Grove” as he drove past the demonstrators, evoking that earlier clash just before the shooting began.10

The CWP, on the other hand, saw China Grove as a success. A Maoist Communist group that advocated political violence, the CWP was largely composed of young, earnest white and Jewish outsiders, many from New York. Several had left jobs as doctors at Duke Hospital to unionize textile factory workers in nearby Greensboro, choosing the town because of its low unionization and the persistent problem of brown lung disease acquired from inhaling cotton fibers. The group also included black activists long involved with the local civil rights movement. While the WVO / CWP claimed a long alliance with the black community in Greensboro, it was a complicated relationship characterized by misunderstanding. Black residents would later express their frustration that the CWP had turned their neighborhood into a site of confrontation without their consent. WVO / CWP leaders claimed China Grove as a victory, ignoring the fears of future violence the confrontation had raised for many group and community members. Following several other Maoist and radical left groups nationwide, the CWP took the official position that organizing against the Klan required aggressive confrontation. They mobilized against what they called a southern Klan resurgence, and against the impact such a movement might have on unionizing and racial cooperation.11

The Klan was, indeed, in the midst of a major membership surge. According to watchdogs, the Klan had been 6,500 strong in 1975 but by 1979 had increased to 10,000 active members plus an additional 75,000 active sympathizers. Duke, at the peak of his popularity on the talk-show circuit, boasted that the KKKK had doubled its membership between March 1978 and March 1979. A Gallup poll, furthermore, showed that the number of people with favorable opinions of the Klan rose from 6 percent in 1965 to 11 percent in 1979.12

While the local community and national press perceived people on both sides of the Greensboro confrontation as dangerous and violent extremists, they also remained deeply engaged in the anticommunism of the Cold War. The Greensboro community, including local media, saw the Klansmen as local boys defending the status quo and the communists as anarchist outsiders who came to town to make trouble. The communists, with their openly revolutionary agenda, were understood as traitorous, radical, and dangerous in a way that Klansmen were not.

The Greensboro shooting was the culmination of almost two years of intense antagonism and repeated clashes between white power groups and the radical left. In July 1978, Tom Metzger, Grand Dragon of the KKKK in California, encountered left-wing opposition when the Maoist Progressive Labor Party (PLP) and Committee Against Racism (CAR) tried to forcibly prevent Metzger’s Klan from screening Birth of a Nation in an Oxnard, California, community center. According to the KKKK newspaper Crusader, the communists had come to the screening prepared for a fight: “PLP / CAR put over nine police in the hospital, swinging lead pipes rolled in Challenge newspapers.” The Los Angeles Times reported that forty leftist demonstrators had charged the community center, wielding clubs, bottles, and pipes. Police arrested thirteen demonstrators for incitement to riot, assaulting police officers, carrying concealed weapons, and refusing to disperse. Between 180 and 300 more demonstrators—characterized by local police as “mostly Mexican-Americans”—remained on the street, shouting “Death to the Klan, Death to the Klan!” One Klansman, blindsided by a protestor’s lead pipe, suffered a broken nose and lost teeth, according to police. Three law enforcement officers and four demonstrators also sustained serious injuries, and seven more policemen reported minor wounds.13

Similar incidents across the country showed rising tension between the left and the nascent white power movement. In August, leftists attacked neo-Nazi Michael Breda in Kansas City as he was giving a radio interview—twelve to fifteen men with clubs and pipes broke into the radio station and beat Breda and another member of his group, the American White People’s Party. Although the attack lasted less than a minute, Breda and two radio station employees suffered significant head and shoulder injuries. A member of the International Committee Against Racism and the Revolutionary Communists Progressive Labor Party—iterations of CAR and PLP—took credit for the beating. Breda told the Los Angeles Times that the same thing had happened during a Houston radio interview.14

The next summer, Klansmen gathered in Little Rock, Arkansas. They intended to stage a counterdemonstration to some 1,200 to 1,500 mostly black men and women protesting the rape conviction of a mentally disabled black man. The event stirred memories of the civil rights movement: Little Rock had seen some of its most tumultuous moments around the integration of the city’s Central High School in 1957, when federal troops were called in to keep order. As the Chicago Tribune reported of the 1979 march, “To preclude violence … state and city officials sent in extra men and firepower, including 230 state troopers, a full platoon of Alabama National Guardsmen, two armored personnel carriers, and police from surrounding communities armed with AR-15 semiautomatic rifles and pump-action shotguns.” This intense armament foreshadowed another burgeoning paramilitary culture in the escalating militarization of civilian policing.15

Two months later, some forty members of Metzger’s Klan met to discuss “illegal aliens and Vietnamese boat people and communists and other things” in Castro Valley, California. Thirty chanting and stone-throwing CAR members stormed the meeting to break it up. The Klan swiftly responded with a fifteen-man contingent armed with clubs and plywood shields, dubbed the “Klan Bureau of Investigation.” Sheriff’s deputies broke up the fight, which resulted in only one minor injury. The speed of the Klan response showed both an escalation from the Oxnard confrontation the previous year and the expansion of group activities throughout California. Although Metzger had militarized his operation as early as 1974 through the Klan Border Watch and other activities, the California KKKK was now regularly prepared for violent confrontation at public events.16

As violence came to the fore of the movement, distinctions among white power factions melted away. Klansmen and neo-Nazis set aside their differences, which had been articulated largely by World War II veterans with strong anti-Nazi feelings, as the Vietnam War became their dominant shared frame.17 White men prepared for a war against communists, blacks, and other enemies. As one Klansman said just after the China Grove altercation, “I see a war, actual combat, eventually between the left-wing element and the right wing.”18

Klansmen and neo-Nazis united against communism at the same moment that elements of the left fractured and collapsed under the pressure of internal divisions and government infiltration. In Greensboro, for instance, the CWP competed locally with the Revolutionary Communist Party and the Socialist Workers Party. The members of each group refused to speak to each other and more than once came to blows while attempting to unionize the same textile mill.19

In contrast, white power activists bound by paramilitarism also developed a cohesive social movement managed through intimate social ties. Intermarriages connected key white power groups, and Christian Identity and Dualist pastors provided marriage counseling. White power activists, who often traveled with their families, stayed at each other’s homes and cared for each other’s children. They participated in weddings and other social rituals and depended on others in the movement for help and for money when arrested. They founded schools to teach their ideas. The Dualist Mountain Church, for instance, hung Nazi flags and performed cross-burnings, but also held “namegivings,” weddings, “consolamentum” ceremonies for the sick, and last rites.20

In September 1979, two months before the Greensboro shooting, about 100 neo-Nazis, National States’ Rights Party members, and Klansmen of various groups convened in Louisburg, North Carolina. Leroy Gibson, convicted in 1974 of two civil-rights-era Klan bombings, organized the meeting. Gibson, who claimed twenty years of service in the Marine Corps, said that 90 percent of his faction, the Rights of White People, was composed of veterans. Gibson described paramilitary training and free instruction for local high school students. Harold Covington, leader of the National Socialist Party of America, spoke of Nazi paramilitary training camps in two North Carolina counties. “Piece by piece, bit by bit, we are going to take back this country!” he said, holding aloft an AR-15 semiautomatic rifle.21 A rope noose was strung from a tree outside the lodge “for purely inspirational purposes,” as Klan Grand Dragon Gorrell Pierce told an Associated Press reporter.22 Many activists attended the meeting heavily armed.

Participants called the rally the first North Carolina meeting of Klansmen and neo-Nazis, although the groups had begun cooperating as early as February. Activists understood how World War II affected relations between their groups. “You take a man who fought in the Second World War, it’s hard for him to sit down in a room full of swastikas,” Pierce said. “But people realize time is running out. We’re going to have to get together. We’re like hornets. We’re more effective when we’re organized.” Pierce argued that urgent threats—particularly communism—required Nazis and Klansmen to band together.23 They named their coalition the United Racist Front and pledged to share resources.

Shifting from the openly segregationist language of the civil rights era to a discourse in which anticommunism was used as an alibi for racism, Klansmen spoke publicly of race as a secondary concern. “The one thread that links all Klan factions and other extreme right-wing groups such as Nazis is hatred of communists,” one Associated Press article reported just after the shooting. “Blacks, they say, are pawns of communism, and integration is merely one salvo in the communist battle to destroy the United States.”24

This strategy drew on a long history of Klan rhetoric that intertwined racial equality, communism, labor organization, immigration, anti-imperialism, and internationalism as threats to the “100 percent American” nationalism early Klans sought to defend. Such ideas were linked not only in Klan rhetoric but also on the left. In Alabama, for instance, the Communist Party attempted in the 1930s to mobilize the same groups targeted by Klan vigilantism and harassment. Communists called the Jim Crow South an oppressed nation, pushed for black self-determination, decried lynching, and defended black men accused of rape. They organized for shorter workdays, better labor conditions, and the right of tenant farmers to engage in collective bargaining. Those who opposed communism in the South—not only the Klan, but many southerners—explicitly associated communism with free love, assaults on the family and on the church, homosexuality, the idea of white women becoming public property, and the threat of interracial sex. In this way, communism and unionization were seen as threats to the white supremacist racial order, which the Klan purported to defend.25

In the days before the Greensboro shooting, the men who would join the caravan papered the North Carolina city with posters of a lynched body in silhouette, hanging from a tree. Part of the caption read “It’s time for old-fashioned American Justice.” (Four years later, the same language and graphic would appear on a poster for Posse Comitatus in the Midwest. The Posse would use the Klan graphic in 1983 to encourage its members to stockpile guns and ammunition in preparation for white revolution. The flier promoted its own circulation: “Reprint permission granted,” it read. “Pass on to a friend.”)26

When the Klan and Nazi caravan drove to Greensboro on November 3, its members expected to wage war on communists. The CWP prepared for confrontation as well, anticipating the brawling that had characterized such clashes in previous years. Several communists wore hard hats. Others armed themselves with police clubs and sticks of firewood. Some brought small guns to the demonstration, though these were mostly left in locked cars.27

But the United Racist Front in North Carolina, following the movement at large, had outfitted itself as a paramilitary force. White power activists brought three handguns, two rifles, three shotguns, nunchucks, hunting knives, brass knuckles, ax handles, clubs, chains, tear gas, and mace. Roland Wayne Wood, a neo-Nazi who had served as a Green Beret in Vietnam, had a tear gas grenade, possibly stolen from nearby Fort Bragg; he wore his army boots. They had packed several dozen eggs for heckling and “a .22 cal revolver as fresh as the eggs—a receipt for its purchase was with it.” This implied that the Klansmen and Nazis armed themselves particularly for the November 3 confrontation, with plans to use the guns. They also had two semiautomatic handguns and an AR-180 semiautomatic rifle, a civilian version of a military assault rifle. The Vietnam War’s guns and uniforms framed this attack, much as the war’s narrative framed the larger movement.28

Significantly, although the Vietnam War had also impacted the left, the militarization of the left never matched that of the paramilitary right, in part because of the right’s cultural embrace of weapons and in part because of the matériel and active-duty personnel that the white power movement continued to draw from the U.S. Armed Forces. Veterans led leftist groups like the CWP, continuing a legacy of protest and armed self-defense begun by veterans of color who participated in civil rights, armed self-defense, and other left movements after homecoming. In Greensboro, one of the CWP leaders, Nelson Johnson, was a local black activist who had fought in Vietnam. While some on the left advocated radical activism in the name of anti-colonial self-determination, however, many wavered on the use of violence.29

On the sunny Saturday morning of November 3, 1979, CWP members arrived in Greensboro’s Morningside Homes, a black housing project, to stage their widely publicized “Death to the Klan” demonstration. Three television news crews arrived. At a rally preceding the march, protestors—along with a number of children wearing red berets—milled around the intersection, singing protest songs and burning a Klansman in effigy. While the group expected confrontation during the march, they did not expect it at the rally. And, due to a series of command decisions and miscommunications, local police had not provided on-site protection, but instead stationed their cars and personnel several blocks away.30

Meanwhile, Klansmen and Nazis convened at a member’s home and talked about “getting into some fistfights” with the communists. Caudle showed people a military machine gun and told them he could get more for $280 each. Spurred on by Eddie Dawson, a longtime Klansman and sometime FBI informant, they grabbed guns and formed a caravan of cars. They intended to picket the march, taunting and throwing eggs, but they also brought the guns and planned to use them if necessary. As Klansman Mark Sherer would later testify, “By the time the Klan caravan left … it was generally understood that our plan was to provoke the Communists and blacks into fighting and to be sure that when the fighting broke out the Klan and the Nazis would win. We were prepared to win any physical confrontation between the two sides.”31

As the caravan of cars approached, a news camera zoomed in, refocusing on a Confederate flag license plate. The protestors took up the chant: “Death to the Klan, death to the Klan.” People in the caravan screamed racial slurs. A young black man yelled, “Get up,” beckoning at the Klansmen and Nazis in the cars. A black demonstrator hit a car with a stick as it accelerated at him; the car swerved wildly at the demonstrators. A teenage white girl shouted from one of the cars, calling the protestors “kikes” and “nigger-lovers.” In a pickup truck, Sherer, smiling, hung out of the front window and fired the first shot in the air, with a powder pistol. The air turned heavy with blue smoke. Another Klansman fired, also pointing his shotgun in the air. Sherer fired twice more, claiming later that these shots hit the ground and a parked car.32

A young Klansman yelled into the CB radio, “My wife’s in one of those cars!”33 Klansmen and neo-Nazis climbed out of the vehicles and ran toward the intersection. The groups met, fighting with fists and sticks.34 CWP member Sandi Smith screamed for someone to get the children out of the way; a black woman, eight months pregnant, lost her balance and fell while trying to run away, her legs pelted with birdshot.35 CWP member Jim Waller retrieved a fellow protestor’s shotgun from a parked car, pulled it up, and aimed it at Klansman Roy Toney. They struggled, and the gun fired twice.36

As the shots continued, a few communist protestors reached for their handguns. Caudle climbed out of his powder-blue Ford Fairlane and walked calmly around to the trunk, from which he distributed shotguns, rifles, and semiautomatic weapons to six men. One of these men, Klansman Jerry Paul Smith—a cigarette dangling from his lower lip—dropped one knee to the ground, a gun in each hand, as he fired into the panicking crowd. Others took aim and shot, over and over. One gunman, a survivor remembered, passed up a clean shot at a white woman in order to kill Sandi Smith, a black woman, instead.37 Klansman Dave Matthews, firing buckshot, would later recount, “I got three of ’em”;38 neo-Nazi Roland Wayne Wood, who had a 12-gauge pump shotgun, would claim, “I hit four of the five that were killed and wounded six more.”39 Three minutes after the first shot, twelve Klansmen and neo-Nazis, including Jerry Paul Smith, Wood, Matthews, Harold Flowers, Terry Hartsoe, and Michael Clinton, climbed into a yellow van and drove away. The police didn’t arrive until the gunfire had subsided and the yellow van had fled the scene. By then, five protestors lay dead or mortally wounded; as many as seven more protestors and one Klansman were injured, and damage to the Morningside Homes community would reverberate across generations.40 The dead included Cesar Cauce, shot by a .357 Magnum in the neck, heart, and lungs. Michael Nathan had “half his head shot off.” Jim Waller lay dead with fifteen bullets in his body. Bill Sampson was shot in the heart; Sandi Smith was shot between the eyes. Paul Bermanzohn, who survived, was shot twice in the head and once in the arm. He underwent major brain surgery and spent the rest of his life in a wheelchair.41

Despite the threats and altercations leading up to the clash, the shooting took Greensboro by surprise. A town of textile mills, rapidly developing Greensboro had a reputation for progressivism but low rates of unionization. The city prided itself on its civil rights history—the Woolworth’s of the first lunch counter sit-in of the civil rights movement, in 1960, would become a designated landmark downtown. Greensboro’s civil rights record, however, turned on a “progressive mystique” that placed a premium on civility, consensus, and paternalism. While protestors experienced a notably lower level of violence in the Carolinas than in the Deep South, North Carolina was still a stronghold of civil-rights-era Klan activity.42

The Greensboro shooting briefly garnered national attention, making Time, Newsweek, and the front pages of several major papers including the Boston Globe, Miami Herald, New York Times, and Times-Picayune. President Jimmy Carter ordered an investigation into Klan resurgence on November 5, and his press secretary announced that a special unit of twenty-five FBI agents had been assigned to the case. Also on November 5, however, the Iran hostage crisis took the front page and held it for some fourteen months. Greensboro became a strange aside, lost in the inner pages of national newspapers.43

But within the white power movement, Greensboro served to energize activists. A few months later, Metzger’s KKKK organized another march in Oceanside, California. Local police had to separate Klansmen from counterprotestors, who shouted “Death to the Klan!” as both sides threw rocks and bottles. Klansmen kicked and beat one member of the Revolutionary Socialist League until blood covered his head and face.44 As they marched, wielding bats, the Klansmen sang a song to the tune of “Sixteen Tons” that lauded the altercation in Greensboro and ended with the refrain, “If the Nazis don’t get you, a Klansman will.”45 The U.S. Department of Justice marked 1979 as a particularly violent year, noting that serious Klan violence had increased 450 percent.46

The movement drew on anticommunism to classify that violence as self-defense. Klansmen and neo-Nazis involved in the November 3 shooting almost uniformly invoked the Vietnam War to justify their actions. As Klansman Virgil Griffin—the Imperial Wizard of the Invisible Empire KKKK, who had brought a semiautomatic handgun to the November 3 march47—said in a public statement long after the shooting:

I think every time a senator or a congressman walks by the Vietnam Wall, they ought to hang their damn heads in shame for allowing the Communist Party to be in this country. Our boys went over there fighting communism, came back here and got off the planes, and them … that they call the CWP was out there spitting on them, calling them babykillers, cursing them. If the city and Congress had been worth a damn, they would’ve told them soldiers turn your guns on them, we whupped Communists over there, we’ll whup it in the United States and clean it up here.48

Griffin saw the Vietnam War not only as a war between nations but also as a universal, man-to-man conflict between communists and anticommunists. He had tried three times to enlist, he said, but doctors declared him unfit for duty because of his asthma. Griffin’s Vietnam War, real to him, was in the realm of a popular narrative. Within that story, he equated all antiwar protestors with the CWP and all veterans with the Klan.49

Michael Clinton, a Klansman who rode in the yellow van on November 3, had a good record of army service, his wife told a reporter. He was drawn into the Klan because of its anticommunism and its paramilitarism. And the wife of caravan member Harold Flowers, the only Klansman injured on November 3, expressed her anticommunism as a common view: “Everybody has concerns.”50

Following the shooting, the local district attorney’s office pressed charges against all fourteen of the Nazis and Klansmen who had been arrested after the melee. Charges included four counts of first-degree murder, one count of felony riot, and one count of conspiracy.

The defendants called upon the Vietnam War story to raise money for their defense. Several of the men from the caravan posed for a photograph in front of the local Vietnam War memorial. The signed photo circulated in the Thunderbolt under the heading “Dangerous Communists Killed” and was reprinted in other white power publications. In an attempt to raise money for the defense and awareness for their cause, the photo also appeared in the Talon, a white power periodical that made its way—free of charge—to prison inmates.51

Trial proceedings began on August 4, 1980, and from the outset reflected the entrenched racism of the North Carolina judicial system. The allowance of peremptory challenges—dismissal of jurors without explanation—meant that the defense could easily select an all-white jury. With fourteen people on trial, the defense had a total of eighty-four peremptory challenges to use at its discretion: defense attorneys dismissed fifteen black jurors for cause and another sixteen peremptorily. This system so clearly produced racially biased juries that North Carolina would abolish it in 1986.52 In this case, it ensured a jury sympathetic to the defendants.

The all-white jurors were all Christian and therefore likely to be fundamentally opposed to communism, understood in 1979 as a threat to any organized religion and, in the South, tinged with the threat of race mixing. Jurors repeatedly voiced anticommunist rhetoric. Foreman Octavio Manduley, who had fled Fidel Castro’s Cuba in the 1960s, spoke frequently to the press about his strident anticommunism, allegedly telling a reporter that the CWP was like “any other Communist organization” and needed “publicity and a martyr.” He implied that the CWP had staged the November 3 altercation with the intention of getting one of its members killed in order to bring attention to its cause. His view resonated with a summary presented in the Thunderbolt: “The hitch came when they got more martyrs than they intended.” The Thunderbolt also reported that Manduley called the Klan “a patriotic organization.”53

Manduley quickly became a favorite of the white power movement, held up as an example of white, anticommunist, first-wave Cuban immigration. Slain CWP member and fellow Cuban Cesar Cauce, on the other hand, was painted as “a pro-Castro enemy agent” of questionable whiteness. Cauce had come to the United States later than Manduley; the Thunderbolt claimed Cauce was “on the first boatlift of so-called refugees. Fidel Castro used the boatlift to empty his prisons and insane asylums of thousands of undesirables to further destabilize America for his planned communist overthrow of the U.S. Government in the future.” This passage conflated Cauce’s arrival with the 1980 Mariel boatlift, which Castro had indeed used to move inmates to the United States. The white power focus on immigrants as communists and as threats to whiteness was a thread that connected the Greensboro shootings to the Klan harassment of Vietnamese refugees on the Texas Coast.54

Although later proceedings would cast doubt on whether Manduley had really expressed views that the Klan was “patriotic” and the neo-Nazis were “strongly patriotic,” at least one juror did make those comments.55 Other jurors and potential jurors expressed sympathy with the defendants or distrust of the CWP. One prospective juror said of the gunmen, “I don’t believe that they were guilty of anything but poor shooting.” Another said of the slain, “I think we are better off without them.”56 One juror, the wife of a sheriff’s deputy, commented after the not-guilty verdict, “I’m really worried about the spread of communism.”57 A man who was chosen as an alternate juror said he believed that it was less of a crime to kill a communist than to kill someone else. According to the Thunderbolt, another juror “stated that the communists got themselves in too deep when they challenged the Klan to attend their ‘Death to the Klan’ rally.… The Klansmen were simply the superior marksmen.”58

Those responsible for the prosecution of the gunmen also reportedly expressed prejudice. Even district attorney Mike Schlosser drew connections between peacetime communist protestors in North Carolina and communist soldiers abroad; when asked by a reporter about his ability to objectively prosecute the Klan and neo-Nazi gunmen, Schlosser referenced his own experience fighting in Vietnam and added, “And you know who my adversaries were there.” In another public comment, Schlosser reportedly said that the Greensboro community felt the CWP members got what they deserved.59

Besides the anticommunism that framed the proceedings, the state trial failed to take into account the role of two government informants who had foreknowledge of the Greensboro shooting and may have actively incited the altercation. Neither prosecution nor defense called them as witnesses. Two other key witnesses against the white power activists also refused to testify because of their fear of reprisal, surrounded as they were by a paramilitary and demonstrably lethal white power movement.60

Public distrust of the CWP mobilized sympathy for the white power gunmen. Furthermore, CWP members repeatedly undermined their chance at what justice the court could offer. Several of the women widowed on November 3 confounded the Greensboro community when, instead of weeping or grieving, they stood with their fists raised and declared to the television cameras that they would seek communist revolution.61 Days after the shooting, an article appeared in the Greensboro Record that was titled “Slain CWP Man Talked of Martyrdom” and implied that the CWP had foreknowledge of the shooting and that some planned to die for the cause. This damaged what little public sympathy remained. In language typical of mainstream coverage, the story described the CWP as “far-out zealots infiltrat[ing] a peaceful neighborhood.” Even two years later, when the widows visited the Greensboro cemetery and found their husbands’ headstone vandalized with red paint meant to symbolize blood, they would not be able to effectively mobilize public sympathy.62

Community wariness of the CWP’s militant stance only increased after the CWP held a public funeral for their fallen comrades and marched through town with rifles and shotguns. The fact that the weapons were not loaded hardly mattered: photographs of the widows holding weapons at the ready appeared in local and national newspapers. In the public imagination, these images inverted the real events of November 3, when a heavily armed white power paramilitary squad confronted a minimally armed group of protestors. The defendants, depicted as respectable men wearing suits in front of the Vietnam War memorial, stood in stark contrast to the gun-toting widows.63

National and local CWP members took up a campaign of hostile protest of the trial itself. The day before testimony began, the CWP burned a large swastika into the lawn of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms director, and hung an effigy on his property with a red dot meant to convey a bullet wound. In the trial itself, CWP members refused to testify, even to identify the bodies of their fallen comrades. CWP widows who shouted that the trial was “a sham” and emptied a vial of skunk oil in the courtroom were held in contempt of court. Although the actions of the widows may have “shocked the court and freaked out the judge,” as the CWP newspaper Workers Viewpoint proudly reported, the widows’ “bravery” didn’t translate as such to the Greensboro community.64 Even those who may have sympathized with the CWP after seeing the graphic footage of the shooting soon found that feeling complicated by the group’s contempt for the justice system, however problematic that system was.

With the CWP widows refusing to tell their stories, attorneys for the defendants built a self-defense case by deploying two widely used white power narratives: one of honorable and wronged Vietnam veterans, and the other of the defense of white womanhood. The defense depended on the claim that CWP members carrying sticks had threatened Renee Hartsoe, the seventeen-year-old wife of Klansman Terry Hartsoe, as she rode in a car near the front of the caravan. Terry Hartsoe testified that he could see the communist protestors throwing rocks at the car and trying to open the door. Such a statement can be seen as alluding to the threat of rape of white women by nonwhite men, a constant theme throughout the various iterations of the Klan since the end of the Civil War.65 White supremacy has long deployed violence by claiming to protect vulnerable white women.

To bolster the claim that the CWP had started the fight, and that the Klansmen and Nazis had acted in self-defense, attorneys called an expert witness from the FBI. Based on the locations of the news cameras that had recorded the altercation, he said, he could pinpoint the origin of each shot with new sound-wave technology. Using this new and insufficiently tested method—later broadly discredited—he testified that the CWP had fired several of the first shots. In other words, the defense convinced the jury that the CWP had started the fight. However, under North Carolina law, the claim of self-defense should have been limited to defendants free from fault in planning or provoking a confrontation. Even had the CWP fired first, the Klansmen and Nazis intended to incite a fight, and had planned it in advance. Their armament alone, and the receipts that showed the timing, indicated as much.66

Meanwhile, some defendants showed little or no remorse for the five deaths and numerous injuries that resulted from the shooting. Defendants testified at the trial that members of the white power movement had displayed autopsy photographs of the CWP victims at a Klan fundraising rally on September 13, 1980. Jerry Paul Smith had obtained copies of the autopsy photos, as well as photos of the dead and mutilated victims taken just after the shooting, from the office of one of the defense attorneys. Smith said someone had displayed the photos at the Klan rally without his knowledge, and that he asked for them to be put away when he saw them.67

The jury spent long hours watching the footage of the shooting—forward, backward, and in slow motion—and witnessed the raw violence of the event. However, jurors heard nothing of the Klan’s use of graphic photographs of the victims for fundraising; they were out of the courtroom when this information came to light. Prosecutors argued that the “jury should hear the testimony, saying it shows the Klansmen acted with malice and have no regrets about the deaths of five Communist Workers Party members,” but the judge disagreed. The jury deliberated without accounting for the continuing violence manifested in the circulation of those images, including profiting from the photographs of the wounded, mutilated, and dead. Such action recalled a long history of circulating lynching photographs. The white power movement was using the pictures to raise money not only for the defense of the “Greensboro 14” but also for acquiring weapons to use in future violent actions—including a projected race war.68

On November 17, 1980, the jury arrived at a unanimous not-guilty verdict after six days of deliberation and twelve major votes. Surprised Klansmen and neo-Nazis wept. The verdict was a national news story. Saturday Night Live even ran a sketch depicting the opening day of “Commie Hunting Season.” The performance received little laughter and scant applause from the live studio audience, and NBC received 150 phone complaints that it was offensive. Perhaps the accuracy of the sketch, despite its overwrought redneck accents and heavy-handed satire, rendered it humorless. The basic point, that a court had effectively condoned the intentional killing of communists, rang true.69

After the acquittal, the white power movement amplified its praise of the Greensboro 14. The Thunderbolt reported at length that the men showed courage during the long trial, from praying and singing “God Bless America” in jail to their heroic homecoming. Family, neighbors, and fellow Klansmen cheered for Smith when he returned home, where “he proudly wore a [Confederate States of America] belt buckle and flew the Confederate flag over his house. One neighbor … remarked: ‘I’ve said all along they ought to pin a medal on those boys.’ ” A journalist reported that Smith’s “feelings toward blacks have softened, partly because of black prisoners he met in jail.” His alleged contrition didn’t last long. Two days later, Smith crashed his car after exchanging gunshots with an unknown person.70

Smith had testified in court that, after a blow to the head, he had no memory of firing into the crowd in Greensboro with a gun in each hand. But he soon traveled to Texas to recount the shooting as a guest speaker at a rally of Klansmen mobilizing against Vietnamese refugees. By 1984, members of the movement could buy a ninety-minute interview of Smith on audiocassette, in which he retold the shooting in detail. The story he allegedly didn’t remember became his currency and celebrity within the movement.71

Indeed, the white power movement took the acquittal as a green light for future action. The Aryan Nations organ Calling Our Nation ran photographs of neo-Nazis in Detroit marching with signs reading “Smash Communism: Greensboro AGAIN.” To some, the trial stood as one battle won in a global war against communism, the same war they had fought in Vietnam. As Klansman and defendant Coleman Pridmore remarked: “This is a victory for America. Anytime you defeat communism, it’s a victory for America. The communists want to destroy America, to tear it down, and they should be tried for treason.”72

The Greensboro case went to trial again on January 9, 1984, this time under civil rights laws in federal court. Although an appeals court blocked a court-ordered federal investigation into “charges of high-level government involvement” under the Ethics in Government Act, this time the court did allow investigation into the role of government informants who provoked or failed to prevent the altercation.73 The FBI and ATF had long used undercover agents in attempts to arrest members of fringe groups on both left and right, and would continue to do so in the years that followed. However, the 1971 end of COINTELPRO made it illegal for undercover operatives to act as agents provocateurs or to initiate or incite violence. The first man in question, Eddie Dawson, was a longtime Klansman who had occasionally reported information to the Greensboro Police Department and FBI. The second, Bernard Butkovich, was a career ATF agent working undercover.74

According to three neo-Nazis and one Klansman, Butkovich—posing as a trucker interested in the movement—had foreknowledge of the Greensboro caravan and did not report it to other agents, his superiors, the FBI, or local law enforcement. He allegedly suggested several illegal activities, encouraging people to get equipment used to convert weapons to fully automatic function and suggesting the assassination of a rival Klan leader. Group members also said Butkovich advised white power activists to harbor the November 3 fugitives after the shooting. The Klansmen and Nazis didn’t take any of his suggestions. Butkovich defended his actions—with the support of his superiors in the ATF—by saying that these statements were necessary to establish him as a credible member of the group for future intelligence-gathering purposes. Butkovich had met Covington and Wood at a White Power Party rally in Ohio in June 1979, but his wire had gone dead, failing to record a lengthy section of their meeting.75

Eddie Dawson, on the other hand, actively worked to plan and provoke the November 3 clash. Dawson gave speeches to fire up the Klansmen and Nazis to protest the CWP rally, according to Klansman Chris Benson’s later trial testimony. And police knew that Dawson was bringing the Klan to confront the CWP. They knew the Klansmen had eggs and planned to heckle, and that they had guns. They knew Virgil Griffin was involved, that he had “a hot head with a short fuse,” and that he frequently carried weapons.76

Dawson obtained a copy of the CWP parade permit prior to November 3 and so he knew where to find the communists. That day, he urged the caravan members to hurry to the CWP rally. At the same moment, the Greensboro Police Department ordered two officers on an unrelated call away from the neighborhood, and sent the rest of the force to lunch. As a result of this sequence of events—as well as prior confrontations between the CWP and the local police that had led the latter to decide that officers would protect the demonstration from afar—no police officers were on the scene when the shooting began.77

The evidence in the federal trial clearly established that the earlier claim of self-defense could not stand. As one prosecutor noted, the Klansmen and Nazis “fired 11 shots before any shot was fired in return,” by which point they had wounded several people. Mark Sherer, who had by then quit the Klan, testified that Griffin had planned to incite a race war in North Carolina and that Smith had experimented with making pipe bombs. Butkovich had overheard a Klansman say the explosives would “work good thrown into a crowd of niggers,” but had failed to mention bombs in his ATF paperwork. Sherer now indicated that the Klansmen and Nazis fired the third and fourth shots, which had been attributed to the CWP by faulty sound analysis in the state trial.78

Despite substantial evidence to discredit the claim of self-defense—and despite the full cooperation and testimony of the CWP—the federal trial exonerated the Klansmen and neo-Nazis a second time. Prosecutors sought to prove that by shooting and killing them, the Klansmen and neo-Nazis denied the CWP members their civil rights for reasons of race. To make this case, the jury instructions specified, the prosecution had to show that race was the “substantial motivating factor” behind the violence. The defense countered that the Klansmen and neo-Nazis acted on political, not racial, motives. They were, as they had said repeatedly, trying to defend the United States from communism. And since the connection between anticommunism and racism in the ideology of white power activists went unexplained, the Klansmen and neo-Nazis walked free again in April 1984.79

The third and final trial began in March 1985. In a civil suit, the CWP widows and eleven injured demonstrators sought monetary damages from the Klansmen, the neo-Nazis, Dawson, Butkovich, the Greensboro Police Department, the City of Greensboro, the State Bureau of Investigation, the FBI, the ATF, and more. The judge dismissed several of these defendants, including the federal agencies that had sovereign immunity, and also dismissed a number of unknown “John Does” because charges against them were too vague. The case went to trial with sixty-three defendants.80

Attorneys for the plaintiffs called seventy-five witnesses over eight weeks; the defense lasted four days. In the most dramatic moment of the trial, former Klansman Chris Benson testified that he had previously lied in court because he feared retaliation. Benson had been the second-highest-ranking Klansman in the Greensboro caravan, and in earlier trials had maintained that the CWP demonstrators provoked the violence. Now he said that white power activists had intended to provoke a confrontation. In cross-examination by Klansmen and Nazis representing themselves, Benson “said he had particularly feared the ‘underground Klan,’ which he described as a paramilitary group that would ‘carry out acts to intimidate people.’ ” Benson named members of the paramilitary Klan, including co-defendant Dave Matthews, and added, “I saw Mr. Matthews shooting at people in Greensboro who were running away from him.”81

Benson, reformed and contrite, stood in stark contrast with most of the other defendants. On the first day of the trial Roland Wayne Wood wore “an olive drab T-shirt with the phrase ‘Eat lead, you lousy red’ printed next to an image of a man in camouflage fatigues spraying automatic weapon fire.” Because Wood chose to represent himself in the civil trial, he wore the shirt in court while acting as a part of the U.S. justice system.82

Despite compelling evidence, the jury, which this time included one black member, delivered only partial justice. In June 1985, it found some of the absent policemen and some of the white power gunmen—Dave Matthews, Jerry Paul Smith, Roland Wayne Wood, Jack Fowler, and Mark Sherer—jointly liable for one of the five deaths and two of the many injuries. Significantly, the only death found wrongful was that of Michael Nathan, the only one of the five people killed who was not a card-carrying CWP member. It might be wrong to shoot bystanders, the decision confirmed, but there was nothing wrongful about gunning down communists. The City of Greensboro paid the full amount of the settlement, covering the costs for Klansmen and neo-Nazis.83

Once again, the white power movement took the settlement payment as endorsement of violent action. As Klansman and Thunderbolt editor Ed Fields wrote in his 1984 personal newsletter, “We must increase activity while we are still free—while juries made up of God fearing White people will free our street activists such as in the Greensboro case.”84 Louis Beam, too, saw Greensboro as a success for the movement. In a film of Beam’s paramilitary camps in Texas circa 1980, he told the camera, “When the shooting starts, we’re going to win it, just like we did in Greensboro.”85

The Greensboro shooting had the effect of consolidating and unifying the white power movement. Most directly, caravan participant Glenn Miller would use the shooting to leverage state leadership in the North Carolina Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, which would soon change its name to the White Patriot Party, uniform its members in camouflage fatigues, and march through the streets by the hundreds. In his increasingly revolutionary Confederate Leader, Miller expressed pride about the shooting even six years afterward.86 A veteran who served two tours in Vietnam as a Green Beret, Miller used paramilitary camps to prepare his new white army for race war, recruited active-duty soldiers, and obtained stolen military weapons. Soon he would align his force with the white power terrorist group the Order.87

The idea of worldwide struggle against communism also aligned the Greensboro gunmen with antidemocratic paramilitary violence in other countries. Thunderbolt, for instance, called it “very strange” to hear President Ronald Reagan “pleading for money to send to guerillas” fighting against communists in Nicaragua and El Salvador when “right here in America we have a clear case of White Christian family men being shot at by communists who returned fire in a perfect case of self-defense.”88 To the movement, there was little difference between white power gunmen at home and paramilitary fighters who worked to extend U.S. interventions abroad.

Harold Covington, an American Nazi Party Leader and veteran who claimed to have been a mercenary soldier in Rhodesia, did not participate in the Greensboro caravan, but sent several of his men to the skirmish. Shortly before the shooting, Covington wrote a letter to the Revolutionary Communist Party, which he mistook for the CWP. “Almost all of my men have killed Communists in Vietnam and I was in Rhodesia as well,” he wrote, “but so far we’ve never actually had a chance to kill the home-grown product.”89 Covington, who saw himself as a person who killed communists—he killed them abroad and he intended to kill them at home—showed how violence at home and anticommunist interventions abroad would link white power organizing with a network of mercenary soldiers who waged war in Central America and beyond.

Katherine Belew, Bring the War Home

295 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Open Letter to His Cop Father

My hope is to make clear, maybe for the first time, my perspective on a variety of points of contention between you and me, not so that we can reconcile them necessarily, but so that I won't feel the need to tiptoe around you any more. Addressing this problem I have with codependency and self-censorship has been my task ever since I left my ex, and I think you yourself would agree that in the last year and a half, I have become much more vibrant and present than I ever was as the kowtowed ghost who let his controlling girlfriend dictate the terms of his existence. In the following letter I strove to be unsparing, but only for the sake of clarity. I don't hold any resentment towards you. I want to take ownership of my own role in our dynamic so that we can move into the future, unencumbered.

A few months ago, you and I argued over my career with regard to the classes I plan on taking for my Masters in library science. After we'd each calmed down, you said that you were only suggesting I keep my options open, as we'd both noted that the future of public libraries, and indeed social services generally, is uncertain at best and possibly doomed. You merely meant to suggest that I look into classes that would prepare me for information career opportunities in the private sector, in the probable case that public libraries no longer exist in the future.

At the time I didn't want to argue any more, and I agreed that you had made good points. I would keep my options open. What you didn't understand, however, was that I only grew "defensive" about my plans after I thought I presented them as exactly what you claimed to be suggesting—that is, I would look into a variety of library and information science related fields while keeping my focus, somewhat idealistically, on public libraries. But then you interjected, as you so often do, with all the reasons why my plan might not be such a great idea. Had I considered the uncertain future of public libraries? (Of course I had.) Wouldn't a librarianship at a prestigious museum be a more stable and lucrative career? (Maybe, but nothing's a safe bet.)

Because I stood my ground, because I intend to fight for what I believe in while I still can, you accused me of being 'defensive.' There's always an underlying tension between us, you said, which is something I don't deny. Why do I always seem resentful? you asked. You accused me of only viewing you as a resource to draw on without any care for you as my father, a totally unfair and manipulative thing to say of your son who followed you and your other son for a decade, watching you coach his brother’s baseball team, without him; your son who desperately wished his father understood his art and literature recommendations, but knows they'll usually go unheeded; your son who, despite knowing what his father did to his mother, and resenting that his father won't speak with his mother at all, still loves his father.

You can't seem to recognize sometimes that your mistakes could have had any effect on the way you and I relate, and I think you think any antagonism between us is me blindly rebelling, an absurd image to have of me, the most docile black sheep any flock has ever had. To be clear, what causes the tension between us is a feeling in me that I won't even be heard if you've previously decided you're in the right. So rather than speak up, I generally keep my mouth shut, which is not healthy for me, nor is it productive of the kind of relationship I'd hope to have as an adult with my father.

You would prefer that I not stake my future on public librarianship, because you would not do that. Therefore, I shouldn't do that. I don't care whether you disagree with me. Ultimately, none of this letter is about convincing you of anything. What I want to address is that I have never felt like my voice would be heard, by you or anyone, really, which is in part a result of having my perspective so often subjected to critical (over)analysis from you, as in our argument over public libraries. Or, it’s a result of having my enthusiasm mocked anytime you and my brother didn't appreciate something I did. 2001: A Space Odyssey is a masterpiece of American art, and you Philistines didn't watch more than 15 minutes of it, but to this day you make fun of me for wanting to watch it with you.

When we had disagreements over any supposed transgression on my part, you quickly dropped the pretense towards being a concerned parent to assume your interrogation persona, with me the guilty-until-proven-innocent suspect. One of the oldest tricks to get someone to fess up is asking the same question several times, forcing the suspect to repeat their story. Any time you seemed suspicious I wasn't answering your questions straight, it would be "You sure? Positive? Nothing else?" The only thing missing was the aluminum chairs and the spotlight in my face. All disagreements were structured this way, with you above, already having the answers, and me below, forced to acquiesce to the judgement presumed. Attempts to defend myself when I felt I was unfairly accused were met with the reprimand to not "talk back," something I've internalized deeply, corrosively, finding myself drawn, in friendships and in love, to those who shout me down or laugh me out. As a result, my natural cowardice and timidity have festered for years.

You have long urged me, since childhood, to be more assertive, less passive, to stop "playing the victim," and these were not unfair or inaccurate criticisms. Like Kafka with his father, none of this is to say I blame you for the effect you've had on me and my inability to speak up. I was a timid child, easily influenced by social pressure and a need for approval, most especially from you. From my child's view I was enamored of what you seemed to represent, which I suppose is unremarkable, as sons and fathers go. Perhaps also unremarkable of fathers and sons is how elusive your approval seemed to be. There was never outright disapproval of me from you, and I always knew you "supported" me. But let's not pretend like we at times did not and do not appear alien to one another. Which is normal, healthy, so long as it's accepted, because we’re separate people, but the trouble fathers and sons get into is they each seek validation from the other—the father struggles to impose his own standards on the son and see his progeny flourish as so judged by the standards imposed, and the son seeks to establish himself as his own person, separate but unable to escape the looming shadow of his father, the son's primary model for what a person is.

One instance where I probably tried to voice an objection to your discipline, an instance where I knew the gravity of the issue you wanted to convey but disagreed that what I'd done deserved such a strong reprimand from you, was when I drew a Klansman in my notebook, being the bored and doodling 8th grade boy that I was, watching a documentary about the Klan in history class. I wasn't approving of the Klan by drawing a man in a pointed hood, but to your credit, you saw an opportunity to make clear the need to take seriously the violence and oppression that African-Americans have faced in this country, and to never trivialize symbols of that violence and hatred. (Fatefully, I was similarly firmly scolded by my mom when she saw a swastika in one of my notebooks, which is when I learned my Polish grandmother escaped the Nazis as a small child in the belly of a freight ship, traumatized by the sight of dead stowaways floating past her, and this after the death of her brother at the hands of fascist thugs.)

When the black community today raises the cry "Black Lives Matter," what they want is a reckoning from American society for the way that black life has historically been deemed disposable. Africans were ripped from their mother country, brutalized on a treacherous trans-Atlantic voyage, and sold off in a land where the climate and environment were entirely alien, their various languages as unintelligible to one another as to their masters. They were subjected to centuries of horrific slavery, whippings, rape, and familial rupture. Any who managed to escaped their bondage risked dogged, murderous pursuit by slave patrols. The de facto opponents of slavery won a civil war and slavery was abolished, and for another century black people were terrorized with lynchings by whites (who were never prosecuted), all while being denied economic opportunity and treated as less-than-second-class citizens in public spaces, not to mention suffering a complete lack of political representation. It wasn't until 1968 that the political rights of African-Americans were codified into federal law, but the mere granting of rights does nothing to address the long term devastation wrought on the black community, which built this country for free, this country that so long denied them not only equal rights and opportunity, but denied them their humanity. And to this day, black people go murdered, in broad daylight, in their cars, or while they sleep, both by the police and by others, without justice. "Black Lives Matter" needs to be said because American society does not seem to acknowledge that black life matters, despite America's lofty ideals for itself as a place of equal protection under the law. If black lives matter, then all lives matter, but not all lives matter until black lives matter.

Saying "Blue Lives Matter" is to be presented with that history, turn it around and say "Yeah, well what about us cops?" No one chooses to be black; all cops choose to be cops. If you want the profession of policing to have the respect you demand people give it, then cops should be aware what they're signing up for: a thankless, demoralizing job that answers to the public, and not the other way around. To say "My job is hard so we matter too!" when, after centuries of oppression, the black community says, "Our lives matter!" is a gross exercise in bad faith. This is why "Blue Lives Matter" is offensive, utterly bankrupt beyond the expression of resentment towards an imagined enemy. American society has no doubts about the value of the lives of police officers. What easier way is there to bring the full force of the American justice system, with a swift investigation and aggressive prosecution, than to murder a cop? The justice system has time and again demonstrated the societal value of police officers' lives. The same can not be said of black lives, which is why "Blue Lives Matter" is far more trivializing of the racism still faced by black people in America than some 13-year-old kid's drawing of a Klansman.

Part of me worries that writing this is futile, that you'll see this as another instance of me "talking back," i.e. saying what challenges your airtight prosecutor's argument. Another part of me thinks what I’m saying resonates with your bedrock American and Catholic values. After all, I had to get my principles from somewhere. But if this doesn't move you, I will rest well knowing that at the very least I'm not shutting myself up any more, and that I'll finally be coming to you as a man and not as your child, facing you squarely, head no longer bowed.

I love you.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The chickens come home to roost, circa late 90s, early 00s. A long post about Jimmy Kimmel being cancelled.

So hi there. I’m in my 30s now, but 16-20 years ago, American media was at a different point in race relations.

We’d just come off of a really hostile 90s. To call someone black had become to call them, “colored,” and you got lambasted, dragged, shamed and chided for not using the term African American. To use ‘black,’ and ESPECIALLY, ‘blacks,’ you were considered the same sort of out-of-touch or openly intolerant example of America’s hostility to black people that we associate someone using the word ‘colored’ for, today.

“It’s AF-RI-CAN A-MER-I-CAN!” They’d yell at you, to remind you every syllable whenever you wanted to reference race in a discussion. Contrast with ‘white.’ This got so ingrained in our vocabulary on penalty of reputation loss for performative wokeness that people just hair-twitch started calling black people african-american whether they were american or not. That’s the root of that bit of stupid, by the way.

But sometime around 1998 to 2001 there was a renaissance in culture and media. The cold shower of using the wrong term went away. The spread and popularity of rap across suburban and rural America and more integration and interactions across groups, as well as just aging out of the sour and bitter taste of the 90s race riots, meant different groups felt more comfortable just fucking around together with banter and jokes. Without someone inherently assuming it came from a place of societal or historical prejudice.

You still could not and would not just flash around the N-word with a hard R, but uh. Young mixed groups of friends got dangerously comfortable letting their white friends use ‘nigga.’ White people did not just suddenly start using it thinking that was okay. Older people that’d lived through when that word was only ever uttered by ignorant or hateful people, whether black or white, discouraged young people from doing that even in jest. During the 00s, that was a generational divide. “The N-Word is a no-no and if I catch you doing it, I’ll beat you up.” Vs. “The N-Word is a no-no and if you’re caught doing it, I might lose my son.”

But the teenagers and early 20-somethings were like, “Oh get with the times, Grandpa! It’s not the 60s-80s anymore! We’re all hip-hop and integrated now!”

Which was not 100% true but if the folks popularizing hip-hop and performing had too big a deal with white fans using the words, they were quiet about them while making their money.

Anyway. That brings us to Comedy Central’s contribution.

Comedy Central started airing stand-up comedians. Race topics got popular. They were ALWAYS popular, but that topic and the people doing it got received to a new generation. It became more socially acceptable to laugh about and be light hearted about. It was diverse, it was inclusive, and it established that such things were okay to talk about freely, in the proper context.

In essence, the days of Cousin Karen and Becky using every opportunity to shame you on behalf of, “our shameful history” every time someone said something like “blackened chicken,” were over. And people were fucking happy for it.

More loose and relaxed attitudes about race jokes, especially, ESPECIALLY when liberal people made them, of any color, was something of a privilege that they reserved only for liberal whites or non-whites of any political denomination. You could say nigger if you were a George Carlin, but not if you were a conservative comedian, since that was synonymous with the George W. Bush type school. The old yee-haw twiddle-banjo XXX jug sippin’ white hood wearing klansman type. It was as much bait to make conservative people upset they weren’t on the list of people that could acceptably say it as much as it was about comradery and acceptance among minority groups. N-Word passes were very common.

And if you were wealthy and liberal enough, entrenched enough with, “the right causes and cultures,” then you could write them for yourself. Whether or not they were validated by black society.

Comedy Central has never made the fact it is/was a largely liberal organization a secret. It served as a place to give black, Asian and Jewish people a soap box and podium to perform and tell their jokes. From The Man Show, to Tough Crowd with Colin Quin, to Crank Yankers, to Chappelle Show, to Mind of Mencia, to the Sarah Silverman Show. That entire decade saw a lot of race based comedians doing shit that they knew at the time was wrong, but, “Hey, we’re living in the future. It’s a different time and a different culture. We’re over it so much that we’re doing it ironically, so it’s okay.”

Well. Here we are, 16-22 years into the future. And much the way the synth keyboard sounded like the future in the 80s, now synth keyboards just sound like the 80s. A whole new generation of 12-18 year old kids see those shows and performs, at least the white ones, as just as archaic and aged and out-of-touch as the comedians from the 1980s to the 1950s and 1920s. Just representing the same, racist expressions and examples of a white supremacist society that took the liberty of upholding that age old mainstay of American media and entertainment; minstrel shows, blackface and making fun of black people.

Even back then I knew there was no such thing as a safe N-word Pass. You use the word nigger even jokingly among friends, you’re tricking yourself into thinking using that word for entertainment won’t come back to bite your ass someday. Doesn’t matter how liberal, progressive or whatever you are, you are not allowed that close.

And we can see exactly this coming to pass now that Jimmy Kimmel is being retroactively cancelled as a scapegoat and example of, “a more privileged and insensitive time.” The illusion that if you were just progressive and liberal enough, on, “the right side of history,” voted for the right people, your heart was in the right place, you believed in the right things, then you could avoid being cancelled since you were doing it ironically.

He’s not even being judged as an individual. Just an extension of the times and people he represents. A piece of prop and furniture of a bygone era, not even a person. When they talk about his ‘crimes’ for being an insensitive and casually racist/sexist person, it’s not about whether he’s changed or not. It’s about whether what he did makes him require ‘proper punishment’ now.

No matter how hard he cries or how much his friends like Adam Carolla insist they were just jokes, or meant in good fun, or that there was no malice behind them, or that they were in mockedy of true bigots, or not intended as real blackface but just absurdism, the fact he did those at all is enough to de-person him. And once condemned, they expect a very specific kind of restitution now.

In the past they used to use social pressure and introduce this sort of thing to you by grooming you. Suggesting ways to, “come good for the crimes of your ancestors.” Or “personal racism.” Mostly by donating your real estate, money and future earnings/income to black charities and black organizations that specialize in blackness. But they only would suggest doing something indirectly. That indirect way where they wouldn’t actually specify what they wanted, just chide you for not doing something specific without telling you what it is.

Now they come out and say: “Give up your property, give up your money, shut up, sit down, sit at the back of the bus, you deserve this.” They don’t just string you along and try to get you to volunteer, “what you could do for your crimes.” Because too many people would stop short of that and just flog themselves, mourning how the past was dead and they couldn’t go back to save anyone.

When what they wanted from the start was people submitting to their ideology, donating land, real estate and labor to black separatism.

Kimmel is being made an example of to normalize this cancelling, and cancelling of any institution or body that gave people like Kimmel, Carolla, Silvermann, Quinn, etc. a voice and platform. And saying because of it, those organizations (Comedy Central) owe restitution to the black community. Saying they are responsible and must own up to their responsibility, and come good.

Except they want them to come good in the form of blank checks and unending acknowledgement that the past cannot be undone until they, themselves, the perpetrators, are undone. or owned by the victims.

There IS no way to apologize. There is no way to wipe the sins away. There is just death or being killed. Even losing everything you have won’t fix the problem, because the perpetrator still exists. And they want you feeling like you’re perpetually obligated to work to right a wrong you voluntarily perpetrated against an entire people.

Kimmel tried to go straight after his Man Show days. He accepted the indoctrination at face value and believed it was progressive and the proper way forwards. He cleaned up his image and act. He agreed to other peoples terms. He played ball on their principles.

And now he’s bring dragged and judged by them for clout and sacrificed to make a point.

You can expect a bunch of famous white comedians (Jewish and otherwise) getting the boiling kettle and expectation to publicly apologize for their “racism and privileged bigotry,” next. And judged harshly as an example of their racist, white supremacist era, if they do not. Any admission of guilt or wrongdoing in the past, and they’ll expect you to hold yourself accountable to their belief the only proper way to repent is to advantage black people.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watchmen: My favorite show of 2019

Now that I’ve watched HBO’s Watchmen in its entirety, I can safely say that it is by far my favorite show I’ve seen this year. The more I think about it though, the less it seems to offer a coherent statement about vigilantism, power and violence the way the original graphic novel did. I don’t think this makes it any less clever, bold or satisfying to watch, but Watchmen is more interested in playing with the weight and drama of themes than actually expressing a clear, useful thesis about them.