#juneteenth celebration week

Photo

“Summertime and Christmas. That’s when I have her. Been that way for seven years. When she’s not in school, she’s with me. Then at the end of the summer I bring her back to her Mom’s house in Florida. Those drop-offs are the worst; I almost miss my flight every time. I wait until the last possible second to call my uber for the airport. I hug her, say goodbye, put my stuff in the car. Then I always gotta come back again and get my last kiss. Always, always. That uber ride sucks. That plane ride sucks. Cause I know I’m not going to see her for a few months. On the wall in my closet we keep track of her height. And every time she comes back, she’s grown like two inches. That’s a lot. That’s a lot I don’t see. But she knows she can call me for whatever, which she does. And whenever she’s here she gets to be the CEO of our lives. She’s not a dictator or anything. But she’s the president. I’m the people. When she says we go, we go. She wants to go to the pool, we go to the pool. She wants to go to the beach, we go to the beach. We came here today for the Juneteenth celebration. Been planning it for two weeks. I’m supposed to be at work today, but I took off early. There’s a bouncy house and face painting and all kinds of good stuff. But she didn’t want to do any of it. We stayed for two minutes. And now we’re back to feeding the animals; same thing we do every day.”

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

PRIDE MONTH CELEBRATION WEEK ☆ Day 1: Film / @creatorsofcolornet EVENT 15: Juneteenth

↳ MOONLIGHT (2016) dir. Barry Jenkins

#moonlight#moonlightedit#filmedit#lgbtedit#pmcw#ccnet#ccnetevent#filmgifs#tuserdana#userk8#userrobin#userkd#userjasmine#userriah#underbetelgeuse#userannalise#userairam#^#1k

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Freedmen Seek Their Fair Share of Billions of Dollars in Federal Aid and Why We Should Care/Rise UP and Support Them

By Eli Grayson

Eagle Guest Writer

Eli Grayson is a Creek Citizen and unabashed supporter of the Freedmen descendants of the 5 Civilized Tribes and the 1866 Reconstruction Treaties.

This past week, we celebrated our Nation’s 244th year of Independence with family and friends over BBQ and fireworks, we should all stop to reflect on its significance, particularly in light of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.

The protests that have swept the country by those outraged over the death of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and far too many others, most of whose names have not garnered national attention, has sparked a long-overdue National dialogue about the treatment of Black Americans in the United States, a reckoning with this country’s past, the many vestiges of slavery that continue today, and what we as a country can and must do to address racism. [It also reminds ALL of us that we have a long way to go.]

Not only have the egregious deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery led to a growing chorus of voices calling for criminal justice reform, it has prompted many to reflect upon racism in both its subtle and overt forms today. It has prompted many to learn about events long celebrated by Black Americans such as Juneteenth (even the NFL recently recognized Juneteenth as an official holiday). And it has prompted many to consider what steps we as individuals, and as a society, can take to affirmatively address it. Here in Oklahoma, attention has focused on Black Wall Street and the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

Well known is the U.S. Government’s abhorrent treatment of Native Americans, which included abrogation of countless treaties, appropriation of land, and forced removal to Western territories, including what is today Oklahoma.

Less well known, however, is the fact that the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole Nations – collectively known today as the Five Civilized Tribes – enslaved Africans. Like Southern plantation owners, they bought and sold slaves and treated them as chattel property. Indeed, slaveholding was such an integral part of the daily life of these tribal nations that each entered treaties with the Confederate States of America in 1861 to ensure its continuance.

Many Americans recently learned for the first time about the meaning and significance of Juneteenth, when nearly all remaining slaves in the United States and its territories were freed – a full 71 days after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox on April 9, 1865 to Union forces led by General Ulysses S. Grant.

Enslaved Africans of Indian Territory

This was not the case for the enslaved Africans of Indian Territory. Even after Lee’s surrender, and even after General Granger read his Orders, the enslaved Africans of Indian Territory were kept in bondage.

Sadly, it was not until the Five Tribes of Indian Territory entered Treaties with the U.S. Government on March 21, with the Seminole Nation, on April 28, with the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations, on June 14, with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and on July 19, with the Cherokee Nation in 1866 – more than a year after Lee’s surrender – were these slaves granted freedom, tribal citizenship, and equal interest in the soil and national funds.

Each of these treaties (collectively known as the Treaties of 1866) contained provisions freeing the slaves and an express acknowledgement that the U.S. Constitution was, and shall remain, the Supreme Law of the land. Notably, there was no mention of tribal law or sovereignty insulating these slave holding tribes from full compliance with the U.S. Constitution, which includes all the Civil War reconstruction amendments.

Today, we find ourselves at a turning point in society. Similar to the country as a whole, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations must take this seminal moment to carefully examine their slaveholding past, their prior allegiance with the Confederacy, enshrined through Treaties entered in 1861, and how they can make amends by fully adhering to both the letter and spirit of the 1866 Reconstruction Peace Treaties.

Congressional legislation

The three House bills are H.R. 2, the Invest in America Act, which includes $1 billion for the Native American Housing Block Grant Program to create or rehabilitate over 8,000 affordable homes for Native Americans on tribal lands; H.R. 6800, the HEROES Act, which includes $6 billion for housing and community development to respond to the Coronavirus; and H.R. 5319, the Native American Housing and Self-Determination Reauthorization Act (NAHASDA), which would authorize $680 million in grants to tribes in the first year and grow to $824 million in the fifth and final year.

Why is this important and why should you care? NAHASDA was originally passed by Congress in 1996 to address poor housing conditions in Indian country and last re-authorized in 2008. It is a flagship Federal law for Native American tribes and the vehicle through which approximately $650 million flows annually to the tribes. In Oklahoma, the Five Civilized Tribes receive more than $62 million annually in direct grants for housing and community development projects. These grants are based on a formula that takes into account various factors including the number of tribal members. Notably, these grants are supported by taxpayers.

For the 2021 Fiscal Year, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which is responsible for administering NAHASDA, has informed the Five Civilized Tribes that they can expect to receive $62,223,462. Thus, nearly 10 percent of all NAHASDA grant funds will go to just these five tribes. By any measure, this is a significant sum, particularly when you consider that there are approximately 573 federally recognized tribes in the United States today, according to data from the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs. And, the final amount will be even greater as Congress has (appropriately) increased the amount of funds for NAHASDA far above the amounts requested by this Administration, including an appropriation of $825 million for this Fiscal Year.

Oklahoma Tribes receive millions in housing aid

Native American Tribes also receive other competitively awarded grants from HUD through a program known as the Indian Community Development Block Grant program. The Choctaw Nation was recently awarded $900,000 to rehabilitate 60 single-family homes while the Cherokee Nation received the same sum to construct a community building, which will house the Early Head Start program. The Chickasaw Nation was awarded $900,000 to construct a youth center in Ardmore, Oklahoma that will provide a safe and clean place for activities and services for Chickasaw tribal youth while the Muscogee (Creek) Nation will use its $900,000 award to construct a facility on the campus of the College of Muscogee Nation. The facility will include space for exhibitions and a lecture hall. These are worthy projects and it is vital that all those in need, including Freedmen descendants, can benefit.

Why Freedmen are concerned

Now if you have read this far, you must be thinking this is great news for these five tribes. And indeed, it is. However, for the Freedmen who are de facto members of the tribe, they may never see a dime of these funds if history is any guide.

Steps such as conditioning or denying the issuance of Citizenship Cards to Freedmen descendants, as well the disenrollment of Freedmen as tribal citizens, is what first led Congress in 2008 to include language in the NAHASDA re-authorization bill to link the receipt of NAHASDA housing grants to compliance with the treaty rights and benefits conferred on the Freedmen through the 1866 treaties.

That is why the efforts of House Financial Services Committee Chairwoman Maxine Waters, D-California, to fight on behalf of the Freedmen of all Five Civilized Tribes is so vital.

The committee she chairs oversees HUD and is responsible for periodically re-authorizing NAHASDA. A bi-partisan bill introduced in Congress last December would re-authorize NAHASDA. However, unlike the 2008 legislation, which contained language to prevent the Cherokee Nation from denying Cherokee Freedmen under the Act, the bill introduced by Rep. Denny Heck and co-sponsored by Reps. Scott Tipton (R-Colorado), Ben Ray Lujan (D-New Mexico), Tom Cole (R-Oklahoma), Deb Haaland (D- New Mexico), Don Young (R-Arkansas), Rep. Gwen Moore (D-Wisconsin), and Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-Hawaii), does not contain any protections for the Cherokee Freedmen nor the Freedmen of the other Civilized Tribes. Similarly, the version introduced in the Senate last week is devoid of such protections for the Freedmen.

Disturbed by the pattern of denying benefits to Freedmen, Chairwoman Waters is seeking assurance that descendants of Freedmen are not denied NAHASDA funds received by the Tribes. The Descendants of the Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes have been working to include language that would ensure that the Freedmen of all Five Civilized Tribes receive taxpayer funded NAHASDA benefits. A similar effort advanced by former House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank was successful and helped to ensure that Cherokee Freedmen received NAHASDA benefits. And in case, any question whether such protections were needed, one look only to the fact that HUD held up NAHASDA funds to the Cherokee Nation for noncompliance.

Native Americans keep fight against Freedmen

Given the harsh treatment of Native Americans at the hands of whites, one naturally would expect these Five Tribes and their supporters and defenders to be more sensitive to the plight of Freedmen who today make up more than 200,000 descendants.

The reality has been quite the opposite.

Despite knowing all this, tribal leaders and their supporters and defenders continue to maintain that such language is not needed and further argue that such language infringes upon the sovereign rights of ALL Native American tribes.

Both arguments could not be further from the truth.

Language ensuring that the Freedmen have access to federal housing benefits is urgently needed for the very reason that Freedmen have routinely been denied NAHASDA benefits for years. And let’s be clear – language we are seeking does not apply to ALL tribes, but rather only to the Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes.

And it does not stop at NAHASDA benefits. Freedmen have been denied tribal citizenship, benefits, and the right to vote as well. Regarding sovereignty, these are federal taxpayer dollars – as such, the federal government and, by extension, its American citizens, have a vested interest in ensuring that all tribal members, including Freedmen, benefit from the funds appropriated pursuant to NAHASDA.

If tribes feel so strongly about their sovereign right to continue to discriminate against Freedmen through denial of federally funded benefits, they can opt to refuse the funding, which would then be redistributed to other tribes. Indeed, it is the height of hypocrisy for any of the Five Civilized Tribes or their supporters to makes these arguments as they count the Freedmen when it comes to the allocation of federal housing grants from HUD yet turn around and deny those very same Freedmen from receiving such benefits.

Freedmen are equal, lawful Tribal citizens

And don’t be mistaken. While Freedmen should be treated as equal citizens under the respective 1866 Treaties, the language we are seeking to include in each of these three bills carefully avoids this ensuring Freedmen receive taxpayer housing and community development benefits on the same terms and conditions as their Native American sisters and brothers.

Indeed, in many instances, these truly are their sisters and brothers given the extensive intermixing of Freedmen and By Blood tribal members over the years. Ironically, this has resulted in some members of a family being considered by the Five Tribes as Indian and therefore citizens of the Tribe while other family members being considered by the tribe as non-Indian and therefore like black sheep.

Yet every time we make a further legislative concession and are led to believe that we are close to a final agreement on language, the Tribes and their supporters and defenders move the goalposts. Sound familiar? Yes, a sensitive issue. The Freedmen only seek to ensure that the Five Civilized Tribes comply with the Treaties of 1866.

Tribal Nations’ actions throw shade on BLM

Lastly, the Five Civilized tribes cannot have it both ways. They cannot on the one hand claim they are victims of discrimination and participate in BLM rallies yet discriminate against Freedmen by denying them suffrage and other rights of tribal citizenship under the guise of sovereignty.

And we are under no illusion that fighting this battle for justice and equality will not remain a challenge. The Five Civilized Tribes have wielded their extensive influence amongst the Nation’s 573 tribes to frame the debate and shape the position of the National tribal organizations in Washington, whom the Members of Congress look to when writing laws that affect the tribes. Adding to the challenge is the fact that the Five Civilized tribes have deployed their sizable resources to contribute to key Members of Congress with the dual purpose of keeping Americans in the dark about their slaveholding past and ensuring that these legal protections for Freedmen never see the light of day in Congress.

But just like our Nation, it is time for the Five Civilized Tribes to stand up and confront their past by taking immediate and affirmative steps to ensure that all descendants of Freedmen receive the federal housing benefits.

This they can do by supporting legislation being courageously advanced by Chairwoman Waters that would require the Five Civilized Tribes to both comply with their Treaty obligations of ensuring access to benefits for Freedmen and report on their compliance to Congress.

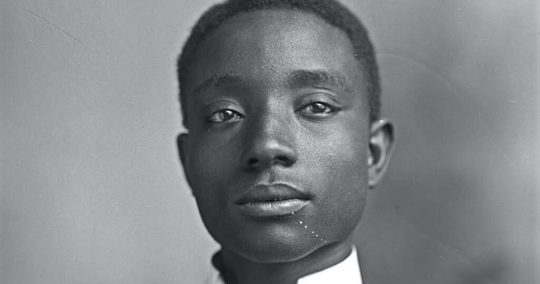

Featured Image (Top), Buck C. Franklin, Nashville, Tennessee, 1899, Calvert Brothers Studio Glass Plate Negatives Collection, The Tennessee State Library and Archives Blog

#Black Lives Matter for Freedmen Descendants of the Five Civilized Tribes#Black American Freedmen#Freedmen#indians#slavery

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Juneteenth Valid Babes🖤 To celebrate Juneteenth I created 8 swatches of My Black Is Beautiful Art.

*Please don't re-upload or claim as your own*

-If you come across any problems don't hesitate to reach out. Enjoy☺

-F𝚎𝚎𝚕 𝚏𝚛𝚎𝚎 𝚝𝚘 𝚝𝚊𝚐 𝚖𝚎 𝚜𝚘 𝙸 𝚌𝚊𝚗 𝚜𝚎𝚎 and share♡

PUBLIC

Public 07/03🖤 Join me on Patreon to get 2 week early access to my builds, sims, cc + more. Thank you so much for your support♡

Youtube | TikTok | Instagram | Tumblr | Amazon Storefront

#Prettyvalidgames#the sims 4 art#the sims 4 build#the sims 4 buy#ts4 cc#ts4 build#ts4 urban cc#the sims 4 urban cc#black simmer#urban simmer#Download my cc#juneteenth#happy juneteenth#my black is beautiful

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

so what's everybody working on recently?

we got upcoming summer (or winter!) solstice, I know there's folks who celebrate the Aphrodesia in the next couple weeks, just had Juneteenth in the States, it's Pride month, what's poppin?

making art? divining? planning rituals? grieving, celebrating? making offerings? what's up??

#I like to focus this blog on people who do stuff#and the stuff that they do#and the entities they do the stuff with/for#as opposed to aesthetic images and/or lists of things they COULD be doing#this includes me#the stuff I do and the entities I do stuff with/for#and things that help me keep focus on that#trying to keep passive reblogging to a minimum#let's get inspired!!!#seasonal rhythms#personal#failing at tumblr

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Choices June Challenge Prompts

Nature

Vacation | Staycation

Hike | Walk (or run)

Ski | Skate (ice or roller)

Boating | Fishing

Cycle | Surf

Garden | Forest

Beach | Mountain

Sunshine | Rain

Honeysuckle | Rose (any flower)

Long days | Long nights

Summer | Winter

Food

Berries | Lemon

Watermelon | Tomato

Pineapple | Peach

Cook | Bake

Picnic | Gala

Cupcake | Donut

Ice cream | Chocolate

Salad | Cake

Cocktails | Mocktails

Folklore

Midsummer night's dream | Fairies

Zodiac signs | Birthstones

Romance | Fantasy

Myths | Superstitions

Stories | Poems

Love | Loathing

Happenings

Proposals | Weddings

Global Day of Parents | Children's Day

World Environment Day | Solstice (summer or winter)

Father's Day | Juneteenth

International Yoga Day | National OOTD Day

World Music Day | Social Media Day

National Selfie Day | National Kissing Day

Pride Month | Pet Appreciation Week

For national or world days, the fanwork doesn't have to focus on the day itself; the theme of that day or celebration will be enough.

Check out the submission guidelines here.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Other Events During Solarpunk Aesthetic Week

What? You mean to say there's other stuff going on during Solarpunk Aesthetic Week?

Yes! While we didn't want to clash with the usual hosting time for Solarpunk Action Week, it's impossible to host an event without other things also going on! Let's highlight just a few other things that are happening this week, so they can maybe inspire some of what you do for Solarpunk Aesthetic Week!

Pollinator Week 2023 actually takes place June 19th - 25th just like our event!

"Pollinator Week is an annual celebration in support of pollinator health that was initiated and is managed by Pollinator Partnership. It is a time to raise awareness for pollinators and spread the word about what we can do to protect them. The great thing about Pollinator Week is that you can celebrate and get involved any way you like! Popular events include planting for pollinators, hosting garden tours, participating in online bee and butterfly ID workshops, and so much more."

Feel free to check their site here to learn more! Maybe make some pollinator-inspired art and take some biodiversity-boosting actions to celebrate!

Juneteenth/Juneteenth National Independence Day is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans, celebrated on the anniversary of an order proclaiming freedom for slaves in Texas on June 19th 1865 (two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued). You may see and hear of public readings, street fairs, cookouts, parades, and more celebrating this event in the US--especially since it was officially declared a federal holiday in 2021, meaning its an official day off from school and work for many people now.

Always, but especially on this day, consider the important role and contributions of African Americans and other Black groups have had and will continue to have on history, punk spaces, and the present and future of Solarpunk!

Summer Solstice is June 21st in the Northern Hemisphere, marking the official beginning of the summer season! This day symbolizes the zenith of the sun's position in the sky, and the longest day of the year.

We're called Solarpunks for a reason! And coinciding with this date was totally purposeful on our parts. Let the sun inspire your works--whether it be thinking up solar panel concepts, painting a sunny meadow scene, or just imbuing your work with the bright and blazing energy of our brightest star, go forth and create!

Winter Solstice is also June 21st in the Southern Hemisphere, marking the official beginning of the winter season! This day symbolizes the death and subsequent rebirth of the sun, and is the shortest day and longest night of the year.

When we visualize Solarpunk, we tend to think of bright and sunny spring and summer days, with lush green growth all around. But what would Solarpunk look like in the fall and winter? Let's start talking about it, changing up our color palettes and creating! And if it's wintertime for you right now, tell us about how you're solarpunking even in the colder months!

World Music Day, also known as Fête de la Musique, takes place on June 23rd and celebrates the universal language of music. This day originated in France in 1982, aiming to encourage both amateur and professional musicians to showcase their talents in public spaces, while also providing free access to concerts and performances for the public. This observance promotes the importance of music in society and celebrates its cultural diversity.

Music often plays a major role in people's lives today, and I see it being no different in a Solarpunk future. Whether you're writing up song lyrics or making chill beats, or listening and contributing to our collaborative Solarpunk playlist, or anything music related--let's take a moment to consider the power of music to spread messages and hope!

June 25th is the last day of Solarpunk Aesthetic Week, and is the Day of the Seafarer! Day of the Seafarer aims to recognize the invaluable contribution of seafarers to the world economy, trade, and well-being of our people. The International Maritime Organization established this day in 2010, and is observed through various activities like ceremonies, celebrations, panel discussions, and workshops.

When it comes to thinking of Solarpunk societies, its important to consider our relationship with the sea and people who traverse it. In addition, the subsect Lunarpunk often has an association with communities living in close ties with the water--consider looking into it as we celebrate Solarpunk Aesthetic Week--there's all kinds of inspiring content out there, and we can always contribute more!

Is there more we're forgetting? Want to share the way you celebrate a particular event? Sound off and let us know--we'd love to hear about other related events and how you celebrate them!

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Archive ♦ Chat ♦ Forums ♦ Tumblr ♦ Dreamwidth ♦ Twitter ♦ Pillowfort

Ad Astra News - 6/11 - 6/17

State of the Archive

Our archive’s header has been updated thanks to enabling by @solarisone. >.> I don’t know anything about that.

In more serious news, we’ve had an incredibly busy week! As you can see below, we’ve had a lot of new people join us, bringing over stories to archive. We’ve had some new faces on our chat server starting with a D, too! I’ve added some community resources under the Community Toolbox FAQ. If you’re planning on joining us, please read the tagging/posting FAQs/Rules, as we are very much not AO3 about that.

All in all, the archive is running well. I’ve got kudos up and working correctly, finally, and while we still have some minor annoyances (the times/dates populating incorrectly on dashboards or browsing pages), everything’s running stable right now and should continue to indefinitely.

There is still a Review Hunt going on until the end of the month: A chance to win art or cash! Right now, Gibraltar and DavidFalkayn are the only participants, come give them a run for the money!

Weekly Challenge #9 - Juneteenth

Our writing challenge this week is in honor of Juneteenth and is therefore the celebration of Black Star Trek characters. So, write a piece between 100 and 700 words in honor of the holiday and the amazing Black characters we’ve gotten from Trek over the decades and add it to our archive collection!

Author Interview with @daraoakwise

Come and get to know our first victim interviewee, @daraoakwise, who currently writes in the AOS universe and has lots of interesting insight to share!

Stories Archived

Star Trek: Discovery

By @starryeyes2000

That Night in the Cave - T - Chris Pike & Sylvia Tilly, Saru/OFC, Ensemble

By TUNiU

Crazy-Assed Cosmonaut - Unrated - James T. Kirk/Spock, Michael Burnham, xover with TOS 🔒

There are Many Benefits to Being a Tardigrade Scientist - Unrated - Paul Stamets, Sylvia Tilly 🔒

The Water Bear Equation - Unrated - Hugh Culber/Paul Stamets, Sylvia Tilly 🔒

The Mountain of Diamond Remix - T - Hugh Culber/Paul Stamets, Michael Burnham 🔒

Star Trek: The Original Series

By @merfilly

Double Impediments - G - Number One

Discovering Boldly - G - James T. Kirk/Spock

Names Memories - G - Ael i-Mhiessan t'Rllaillieu

The Right Answer - G - Amanda Grayson, Sarek

Logical Choice - G - Saavik

Two Lies and a Truth - G - Spock, Leonard “Bones” McCoy

Honors in Family - G - Zar, Spock, Saavik

Contemplations, Eons Apart - G - Zar, Spock, James T. Kirk

Wandering Path - G - Saavik/Spock

Pandora’s Prodigy - T - Saavik, Spock, Amanda Grayson

Crucible Forged - G - Cleante al-Faisal/T'Shael, Aernath/Jean Czerny

Following the Fortunes of War - G - Piper/Sarda

Mutual Exploration - T - Cleante al-Faisal/T'Shael

Second Voyage - G - Leonard “Bones” McCoy, James T. Kirk, Spock

A Chosen Future - T - David Marcus/Saavik

A Gift Shared - G - Christine Chapel, Nyota Uhura

A Talented Opponent - G - Hikaru Sulu, Nyota Uhura

Incidental Touches - T - James T. Kirk/Spock

Improbable - G - James T. Kirk, Leonard “Bones” McCoy

Educated Rescuer - G - James T. Kirk, Nyota Uhura

By @sl-walker

Seamark - M - Spock/Montgomery “Scotty” Scott

The Last Love - T - Christopher Pike

Now - T - Montgomery “Scotty” Scott

Junkyard Dogs - T - Montgomery “Scotty” Scott, Jay McMillan

Star Trek: Alternate Original Series

By @daraoakwise

A Higher Power When You Look - M - Montgomery “Scotty” Scott (AOS) & Nyota Uhura (AOS), Nyota Uhura (AOS)/Spock (AOS)

Ideals - G - Spock (AOS)

Lightning - G - Montgomery “Scotty” Scott (AOS)

By @merfilly

Dammit Jim - T - Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS), James T. Kirk (AOS)

Grumpy Doc - G - James T. Kirk (AOS)/Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS)

Cold Logic Brings No Comfort - G - Spock

Alone - G - Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS)

5 Moments in a Friendship - G - Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS), Nyota Uhura (AOS)

Because He Knew - G - Spock, Saavik (AOS)

By @starryeyes2000

Trust Love One More Time - T - Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS)/Original Female Character

By VelvetMouse

Anchor in the Deep - T - Christine Chapel (AOS)/Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS)

The Little Things - G - Christine Chapel (AOS)/Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS)

Follow Through - G - James T. Kirk (AOS)/Janice Rand (AOS)

Secrets - G - James T. Kirk (AOS)/Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS)

No Choice At All - G - Christine Chapel (AOS)/Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS)

Tiny Pushes - T - Janice Rand (AOS)

Clean-up Duty - T - James T. Kirk (AOS), Spock (AOS), Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS), Nyota Uhura (AOS)

Home Before Dark - G - Christine Chapel (AOS)/Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS)

Lady-like - T - Christine Chapel (AOS), Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS), Roger Korby (AOS)

Taking Control - G - Christine Chapel (AOS) & Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS)

Morning Surprise - G - Christine Chapel (AOS) & Leonard “Bones” McCoy (AOS), James T. Kirk (AOS)

Paradise Lost - T - Christine Chapel (AOS)

Star Trek: The Next Generation

By @beatrice-otter

A Grief Shared - G - Guinan/Jean-Luc Picard, Jean-Luc Picard & Robert Picard

No Place Like Home - G - Amanda Rogers, Clark Kent | Kal-El | Superman, DC Crossover

By @merfilly

One Lesson Learned - G - Lwaxana Troi

Mixed Regrets - G - William Riker

Encounters at Adulthood - G - Deanna Troi/William Riker, Lwaxana Troi

Appraisal - G - Lwaxana Troi

There Among the Stars - G - Beverly Crusher

Mother, Please! - T - Deanna Troi, Lwaxana Troi

Without Sight - M - Beverly Crusher/Deanna Troi

Complications of State - G - Deanna Troi

Breathlessly Spellbound - T - Beverly Crusher/Deanna Troi

Conflict of the Soul - G - Deanna Troi

Finding Experience - T - Guinan/Ro Laren

Flattery - G - Jean-Luc Picard/Beverly Crusher

A Little Snag - G - Deanna Troi/William Riker/Beverly Crusher

Joined - T - Beverly Crusher/Deanna Troi

Gumption - G - Q

Bouldevard Lounge - G - Deanna Troi/William Riker

Complimentary - G - Tasha Yar, Data

Coffee and Chocolate - G - Beverly Crusher/Deanna Troi

By VelvetMouse

An Extension of Myself - G - Jean-Luc Picard/Beverly Crusher, William Riker/Deanna Troi

The Triumph of Time (We Are Everywhere For Your Convenience Remix) - T - Jean-Luc Picard & Beverly Crusher

Fakers (The Get a Second Opinion Remix) - G - Beverly Crusher, Deanna Troi

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine

By @beatrice-otter

Schoolwork - G - \Jake Sisko & Kasidy Yates

By @merfilly

Won’t Turn Back - G - Kira Nerys

Womb Makes Three - G - Kira Nerys, Keiko O’Brien

The Return - T - Kira Nerys/Odo

Courting an Oblivious Person - G - Kira Nerys/Jadzia Dax

By nostalgia

In the Ranks of Death You’ll Find Him - M - Miles O’Brien/Julian Bashir

The Strange Glue That Held Us Together - T - Julian Bashir/Martok

The Chemistry Between Us - M - Ezri Dax/Julian Bashir

A Mutual Interest - T - Miles O’Brien & Julian Bashir, Leeta

By VelvetMouse

(G)hosts - G - Jadzia Dax

Star Trek: Voyager

By nostalgia

Captain - G - Chakotay/Kathryn Janeway

A Shape With Three Sides - T - Chakotay, Kathryn Janeway, Tuvok

The Worst Days - T - Kathryn Janeway/Chakotay

Star Trek: Picard

By Kennel_Boy

A Gift Between Moments - G - Elnor & Hugh | Third of Five - 🔒

More Alive To Tenderness - T - Elnor/Hugh | Third of Five - 🔒

Alternate Universes

By Trekfan

An Ideal Remembered - G - Rose Reilly, Anne Reilly

Expanded Universes

By DavidFalkayn

Interlude - M - Ensemble Cast, Raptor-verse

La Belladonna - M - Zsuzsanna (Zsa-Zsa) Rosza/Eliza Flores, Ensemble, Raptor-verse

The Gathering - M - Ensemble Cast, Raptor-verse

Reminiscences - M - Ensemble Cast, Raptor-verse

We're not in Kansas Any More - M - Ensemble cast, Raptor-verse

Compromises must be made - T - Morgan Bateson, Original Characters, Raptor-verse

Out with the Old in with the New - M - Ensemble cast, Raptor-verse

The Devil’s Playthings - M - Ensemble cast, Raptor-verse

The Gang's Kinda All Here - M - Ensemble cast, Raptor-verse

The Horror Below - M - Twesata Glex/Rana Thanoptis, Raptor-verse

Failure on Fehl Prime - M - Jane Shepard, Ensemble Cast

Time Trippin’ - M - Ensemble Cast, Raptor-verse

By Gibraltar

Passing the Torch - T - Donald Sandhurst, Pava Lar’ragos

The Penalties of Success - G - Donald Sandhurst

Life is Choices - G - Donald Sandhurst

By Mick

Welcome Aboard - T - Starship Excalibur

The Long Goodbye - Unrated - Starship Excalibur

Star Trek: Multiple Series

By LordRobertBruceScott

Star Trek Hunter - Rock of Ages - G - Original Characters

Nonfiction & Meta

By DavidFalkayn

Raptorverse Mass Effect Dramatis Personae - Unrated

#star trek discovery#star trek the original series#star trek the next generation#star trek picard#star trek voyager#star trek deep space nine#st:dsc#st:tos#st:tng#st:pic#st:voy#st:ds9#expanded universes#spirk#mckirk#ocs#chapel/mccoy#star trek fanfic#trekfic#ad astra fanfic#some really awesome stuff in this news post!#you should come check these out#and leave some comments!#anyway#please do signal boost!

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Easter and TDOV really just showed that people have a lot of shit to say but don't know what the everloving fuck they're talking about.

"Why do Trans people need a day you have a whole month already???" Trans Visibility Day is for Trans people, Pride month is for all Queer people. It's different. But also there are other national months that have a dedicated day in a different month.

Easter is a different day every year and sometimes it's going to land on a day that already has a holiday/nationally recognized day. You gonna be mad at stoners next year for daring to have a smoke with jesus?

Why do you think February is Black History Month? Or why May is AAPI month? Or why June is Pride month?

Do people think that national months happen by closing our eyes and pointing at a calendar? Do you think we just picked a month at random and claimed it ours? Significant moments and events in history happened during those months. And it often took years for those months to be nationally recognized. History is actually so fun to learn about please read something I'm begging.

• And if you're outside of the U.S and you have different national months/holidays please let me know I'd love to read about it!

(Also I only used History.com and one AmericanBar articles because other links weren't working but I encourage you to do research from other sources as well as read the articles I linked.)

In February Black History Month was Black History week for decades:

In March Women's History Month started as Women's History Week:

April is Arab American Heritage Month:

May is Asian American & Pacific Islander Month:

June is Pride Month:

Juneteenth:

July is Disability Pride Month:

September 15 to October 15 is Hispanic Heritage Month:

Indigenous Peoples' Day is the second Monday in October, and November is Native American Heritage Month:

#history#black history month#womens history month#arab american heritage month#asian american and pacific islander month#aapi month#pride month#stonewall#disability pride month#hispanic heritage month#Indigenous peoples day#native american heritage month#punk#trans day of visibility#lgbt#lgbtqia#lgbtq#queer#trans#american history#us history#easter#juneteenth#tdov#queer history

5 notes

·

View notes

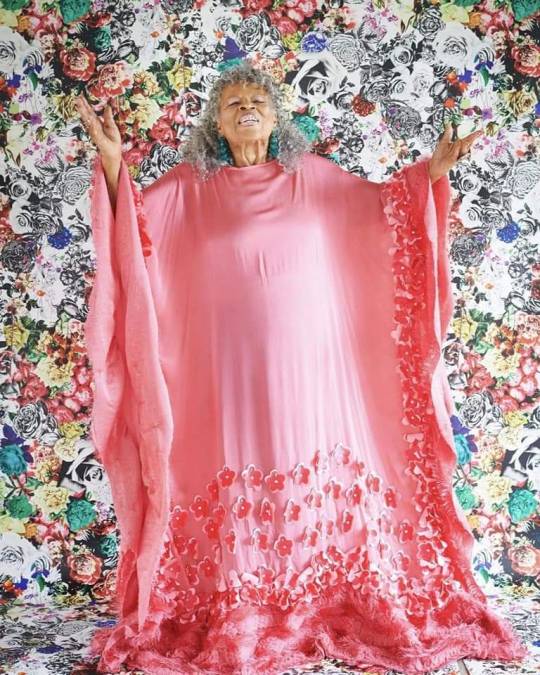

Text

Here’s to celebrating #Juneteenth with the swag and soul of Ms. Opal Lee. 🙌🏿💖 We owe deep respect to Ms. Opal Lee whose unwavering commitment is surely responsible for the Senate (finally!) passing a bill to make Juneteenth a federal holiday this week. I hope you’ll join me in thanking @TheRealOpalLee for her inspiring accomplishment, let alone at 94 years of age!

One more thing before I go: this national acknowledgment is imperative; however the real substantial change that must follow is ensuring education is introduced and safeguarded in schools on the significance of Juneteenth and Black people's experiences in and contributions to American society.

The oversight of these historical events blinds and misleads both our present and our future generations. It encourages willful ignorance and the touting of revisionist history. The mission started by Ms. Opal Lee is not yet accomplished, but rather a responsibility for each of us to carry forward.

Photo credit: @ElizabethMarylavin for @SouthernLivingMag

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The cottonfields of Georgia were once worked by the enslaved. REUTERS/Tom Lasseter

WASHINGTON

We sat in the pews of a Methodist church last summer, my family and I, heads bowed as the pastor began with a prayer. Grant us grace, she said, to “make no peace with oppression.”

Our church programs noted the date: June 19, or Juneteenth, the day on the federal calendar that celebrates the emancipation of Black Americans from slavery. The morning prayer was a cue.

The kids were ushered from the sanctuary to Sunday school. My sons – one 11, the other 8 at the time – shuffled off to lessons meant for younger ears.

The sermon, delivered by a white pastor to an almost entirely white congregation, was headed toward this country’s hardest history.

“We are a nation birthed in a moment that allowed some people to stand over others,” she said from the pulpit, light flooding through the stained glass behind her. “We’ve all been a part of taking what we wanted. White people, my community, my legacy, my heritage, has this history of taking land that did not belong to us and then forcing people to work that land that would never belong to them.”

The pastor did not know that I was months into a reporting project for Reuters about the legacy of slavery in America. It was an idea that came to me in June 2020, shortly after returning to the United States after almost two decades abroad as a foreign correspondent.

We had moved to Washington just 18 days after George Floyd was killed by a white police officer in Minneapolis, and in our first weeks back, I found myself drawn to the steady TV coverage of protests from coast to coast. I read about the dismantling of Confederate statues on public land – almost a hundred were taken down in 2020 alone. I thought about my own childhood, about growing up in Georgia. And I wondered: Had this country, which I had yet to introduce to my sons, ever truly reckoned with its history of slavery?

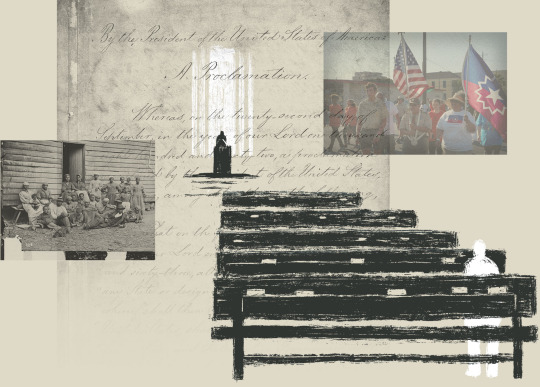

REUTERS/Photo illustration REUTERS/Photo illustration

I wondered, too, about our most powerful political leaders. How many had ancestors who enslaved people? Did they even know? I discussed the idea with my editors, who greenlighted a sweeping examination of the political elite’s ancestral ties to slavery. They also raised another question: What might uncovering that part of their family history mean to today’s leaders as they help shape America’s future?

A group of Reuters journalists began tracing the lineages of members of Congress, governors, Supreme Court justices and presidents – a complicated exercise in genealogical research that, given the combustibility of the topic, left no room for error.

Henry Louis Gates Jr, a professor at Harvard University who hosts the popular television genealogy show Finding Your Roots, told me that our effort would be “doing a great service for these individuals.”

“You have to start with the fact that most haven’t done genealogical research, so they honestly don’t know” their own family’s history, Gates said. “And what the service you’re providing is: Here are the facts. Now, how do you feel about those facts?”

And there was more to the project, something I needed to do, if only out of fairness. As a native of Mississippi who grew up in Georgia, I would examine my own family’s history. A passing remark made by my grandfather long ago gave me reason to believe my experience wouldn’t be as joyous as the advertisements I saw for online genealogy websites. Instead of finding serendipitous connections to faraway lands, I suspected I would find slavery on the red clay of Georgia.

But all of that was for work. It wasn’t for Sunday church, I thought, sitting next to my wife. My mind wandering, I looked down at the Rolex on my wrist.

This is the story that I tell myself: Those are things that I earned, paid for with hard work. I am a high school dropout. My mother is a high school dropout. My father is a high school dropout. My sister is a high school dropout. My first home was in a southern Mississippi trailer park. My mother was pregnant with me at the age of 19. My dad left our lives early.

I got my GED. I moved from a community college to the University of Georgia, working as a short-order cook while earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism.

For me, church is a place that offers a soothing sense of order, of ritual. That morning, I didn’t feel comfortable. I resented the pastor. I was there to listen to the choir and contemplate a Bible verse or two, not to be lectured. Especially about a subject I was grappling with personally and professionally.

“We would swear with our last breath that we do not have a racist bone in our bodies,” she continued. “But some of us were born in a lineage of people who take land that is not ours and enslave other people.”

Her words would come close to the facts that my reporting surfaced in the months ahead. Still, on this Juneteenth, I was done listening.

After the service, I walked to the car with my wife and sons. I didn’t talk with them about the sermon as we headed to our home on the outskirts of Washington. Ours is a street of rolling green lawns and shiny Cadillac Escalades. On the edge of the U.S. capital, a city where some 45% of the population is Black, the suburb where we live is about 7% Black. It was an inviting place for a white man to escape the pastor’s message.

That cocoon soon started to unravel. I had begun a journey that would take me back to places I held dear but had not truly known. What I would come to learn in researching my ancestors didn’t tarnish my love for family. At times, though, I did worry that I was betraying them.

It also left me with two questions I have yet to answer. What do I tell my sons about what I found, and what does it say about their country?

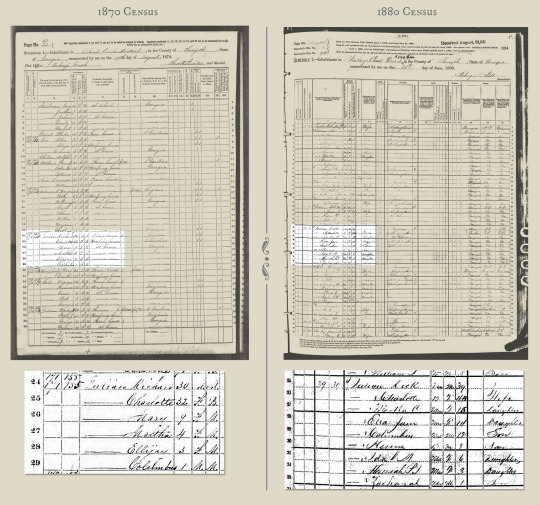

Introducing America

Throughout 2022, our reporting team assembled family trees for Congressional members. We connected one generation to the previous, like puzzle pieces snapping one to another, extending years before the end of the U.S. Civil War in 1865. We learned to decipher census documents written in sometimes bewildering cursive. Enlisting the help of board-certified genealogists, we became comfortable with the types of inconsistencies that surface in the old papers: names slightly misspelled, ages off by a few years, children who disappear from households as they die between censuses or marry young.

For months, my attention was drawn to the complexity of the task, and I scoured websites for documents that went beyond census records: certificates of birth, death and marriage, obituaries, military service forms, family Bibles.

The work was painstaking, and a welcome diversion. Each time I thought about building out my own family history, I winced at the subject coming close. Those were my people, my history.

Eventually, I knew I had to get started.

My wife and I were born in America. Both of us are journalists. We met in Baghdad, there to cover the war in Iraq. We married later while living in Russia, had our first son in China, our next in India. After two years in Singapore, we decided it was time to take the boys home to America, a land they’d visited on summer trips to their grandmothers’ houses in Georgia and Virginia but hardly knew.

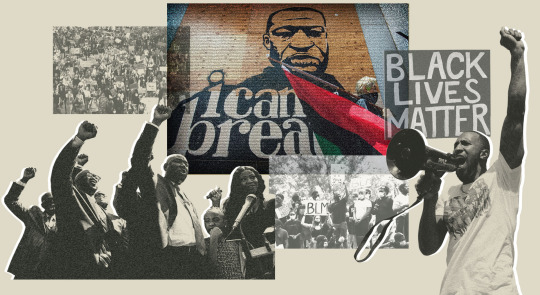

Their introduction began less than three weeks after the May 25 death of George Floyd, as soon as we rode in from the airport. As we approached shuttered stores and boarded-up windows in downtown Washington, our younger son looked at the graffiti and banners and asked what the letters BLM stood for. My wife and I spelled it out – Black Lives Matter – and told him about Floyd’s death. Six at the time, he had no idea what we were talking about. His older brother explained the protests were to help Black people. Then he reminded him that their uncle, my sister’s husband, is Black. Our little boy went quiet. In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, protesters took to the streets across America.

REUTERS/Photo illustration In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, protesters took to the streets across America. REUTERS/Photo illustration

Last spring I began to trace my family’s lineage in detail. I had gone through this process for dozens of members of Congress. Now I was looking at my own mom. As I started a family tree, I did not like typing her name – it felt like I was crossing a line. I opened the search page at Ancestry.com and entered the names of her parents, Harriet and Brice.

Brice was 69 or so when he visited us in Atlanta during the summer of 1994. I was a teenager. Joseph Brice James was my grandfather, but we just called him Brice. Like my own father, he hadn’t been part of our life. He lived in Chicago and had worked as a traveling salesman. The trip may have been one last effort by him to connect. He wasn’t well and would die about eight years later.

It would be that visit – really, just one line that Brice muttered – that came back to me in the summer of 2020 and started my own personal reckoning.

My Grandfather’s Words Joseph Brice James. (Courtesy: Tom Lasseter)

Here’s what I remember: Brice wanted to see the farm where his ancestors, our ancestors, lived. My mother drove, and my sister and I sat in the backseat of our family’s aged Toyota Corolla. The address Brice helped direct us to was about an hour out of Atlanta. My mother had been there before, too, but my ancestors had sold it off, parcel by parcel, starting around 1947. We pulled over in front of a clapboard farmhouse.

I wasn’t sure why we were there, or who might have once lived on the farm. Brice, a gaunt figure with closely cropped hair and large glasses, didn’t volunteer much. I walked alongside him in silence, across a field spotted with pine trees, on the edge of a lake. Then Brice paused, flicking his wrist toward an old well and said: “The slaves built that.” A moment passed and he kept walking, offering nothing further.

Those four words stayed with me, though, in the way that happens with some white families from the South: I now knew, if I wanted to, that somewhere in my history there was a connection to slavery. The farmhouse in Georgia, once owned by the ancestors of Reuters journalist Tom Lasseter.

REUTERS/Tom Lasseter

Where to begin? Before prying into Brice’s side, I decided to look somewhere more familiar. The census shows my mother’s maternal grandmother as Cornelia Benson. I grew up calling her Grandma Horseyfeather, a nickname given her by my mother’s generation, the product of a long-ago children’s tale.

Looking at the 1940 census, there was Cornelia Benson of Brooks County, Georgia. I knew Brooks County as a place of Spanish moss, where we caught turtles and lizards in my childhood. I loved Thanksgiving at 618 North Madison Street, where a dirt driveway led to the back stairs and then a kitchen with long rows of casseroles. Grandma Horseyfeather, born in 1898, spoke in a slow, deep drawl. She wore lace to church. I adored her and I adored Brooks County.

At home in Atlanta, I felt lost at times, my single, working-class mom stretching one paycheck to the next. But in Cornelia Benson’s house, I felt at ease. My identity was simple: I was a white kid descended from generations of white people from the deepest of south Georgia.

As a child, I did not ask what it meant to belong to a place like Brooks County. Now I wanted to know. Cornelia Benson with Tom Lasseter as infant (left); Tom Lasseter during a childhood visit to Quitman, Georgia. (Courtesy: Tom Lasseter)

A story came to mind. I was young, and the grownups were visiting at the dining table. Someone started to tell a story about life in Quitman, the town in Brooks County where Grandma Horseyfeather lived. It was about the Ku Klux Klan and its marches.

The Klan would saunter down the street, wearing hoods and sheets, thinking no one knew who they were. The story’s punchline: All the “colored boys” – meaning Black men – knew who was wearing those sheets. They could see the shoes the white men were wearing. And who do you think shined those shoes?

I remember a tittering of laughter ripple around the table.

It was a vignette I sometimes trotted out when discussing the South. I’d shake my head and show a rueful half-frown that communicated disapproval, but not too much. My Brooks County relatives didn’t quite fit the pastor’s words. I knew they had some racist bones in their body. Still, these were my people. They didn’t mean any harm.

Reading back over the story after I wrote it down last year made me wonder what I didn’t know. So I did something that had never before occurred to me: I looked up the history of Brooks County, Georgia. It did not lead anywhere good.

In 1918, at least 13 Black people were killed in a rash of lynchings by mobs in Brooks that cemented its reputation for bloodshed. A flag that hung from the NAACP national headquarters in New York City, 1920-1928 (Source: NAACP via Library of Congress). Lynchings in Brooks County, Georgia, in the early 20th century cemented its reputation for racism and bloodshed.

REUTERS/Photo illustration

“There were more lynchings in Brooks than any county in Georgia” at the time, according to a 2006 paper examining lynchings in southern Georgia. Among the 1918 victims: Near the county line, a pregnant woman was tied to a tree and doused with gasoline before her belly was slit open with a knife and her unborn child tumbled to the dirt. The woman was shot hundreds of times, “until she was barely recognizable as a human being.” And then both her and her fetus’ burial spots were marked by a whiskey bottle with a cigar placed in its neck, according to the paper – “Killing Them by the Wholesale: A Lynching Rampage in South Georgia” – published in The Georgia Historical Quarterly.

I toggled my Internet browser to census records. Cornelia Benson and her husband weren’t yet living in Brooks County as of the 1920 census. They moved there between 1920 and 1930. I felt relieved, clean. I didn’t know any of that history. No one had told me.

But the more I learned, the more I played out the possibilities, the more troubled I felt about the Ku Klux Klan anecdote.

One morning in my home office, I pulled out a cell phone to record my thoughts about those memories. As I did, I heard the wood floorboards creaking. It was one of my sons walking outside the room. I waited for him to go downstairs before starting. When I later listened to my recounting of the Ku Klux Klan story, I noticed I’d used the phrase “Black people” rather than “Colored boys.” Without thinking, I’d cleaned the story up around the edges, making it easier to tell.

‘Mules, Oxen…and The Following Negroes’

Brice died in 2001. I never learned anything else from him about that well on the property our ancestors owned. Having read through the Brooks County material, it was time to see what I might find out about Brice’s side of my family.

I knew my grandfather was born in Canada, but that his side of the family was somehow connected to that land in Georgia. Using Ancestry.com, I found a 1948 border crossing document for him, with the names of his father and mother. I took those names and found his parents’ 1921 marriage license in Fergus County, Montana.

I noticed that his mother’s maiden name was Lila M. Brice, and that her parents were Ethel Julian and Joseph T. Brice. I looked for Ethel Brice. There she was, in the 1910 census. She was living with her daughter Lila in Forsyth County, Georgia, after a divorce – back in the household of her father, a man whose name I had never before heard: Abijah Julian.

The trip to the farm house in 1994 was in Forsyth County. The old clapboard house was built in the 1800s. And the well that Brice mentioned, the one that he said enslaved people built, sat right next to the house.

From one census to the next, I followed Abijah, a name from the Old Testament.

Information about the Julian family wasn’t hard to find once I started looking.

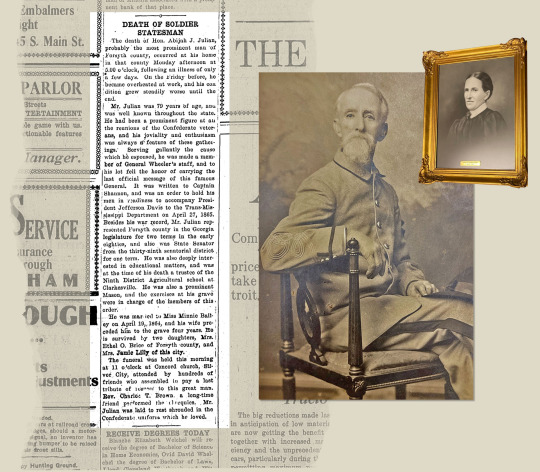

Working my way backwards, I learned Abijah Julian died in 1921. His passing was marked in The Gainesville News by an item headlined “DEATH OF SOLDIER STATESMAN.” Placed high in the article was the fact that Abijah Julian was part of a Confederate cavalry general’s staff during the Civil War, and that in his later years he “had been a prominent figure at all the reunions of the Confederate veterans.” The piece ended with these words: “Mr. Julian was laid to rest shrouded in the Confederate uniform which he loved.” Abijah Julian, seated, was buried in a Confederate uniform. In an account by his wife, Minnie Julian, she described him returning from war “broken in health and spirit. Negroes free, stock stolen and money – Confederate – valueless.” (Sources: Historical Society of Cumming/Forsyth County, Georgia. Newspaper clipping: The Gainesville News, June 1921)

He had served in Georgia’s state legislature for three terms. I looked for more details about him and his ancestors before the Civil War.

Abijah’s father, also a member of the state legislature, died in 1858 at home in Forsyth County, according to press reports. It was just a couple months before Abijah’s 16th birthday.

Some four years later, Abijah went to war against the United States. In 1864, a year before the Civil War ended, he married a woman in Alabama, the daughter of a doctor, who moved to the Julian farm. In an account by his wife, Minnie Julian, she described Abijah returning home after the war, “broken in health and spirit. Negroes free, stock stolen and money – Confederate – valueless.” In the very next sentence, however, she noted they still had 600 acres of land.

Her words signaled that Abijah had enslaved people. But I needed more proof.

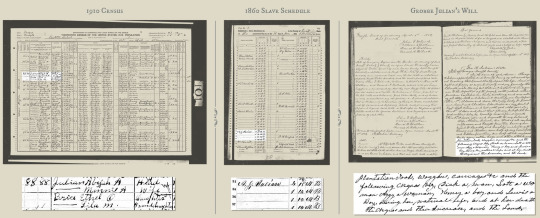

In addition to the usual household census forms, in 1850 and 1860 the U.S. government created a second document for the census takers to fill out in counties in states where slavery was legal. It’s referred to as a slave schedule, and it lists by name men and women who enslaved people, under the column “SLAVE OWNERS.” The form gives no names of the human beings they enslaved. Instead, it tabulates what the document refers to as “Slave Inhabitants” only by the person’s age, gender, color (B for Black or M for Mulatto, or mixed race) and whether they were “Deaf & dumb, blind, insane or idiotic.”

After you find a slaveholder on the household census form, matching them to the slave schedule can be complicated. In some counties, multiple men of the same or similar name enslaved people. And of course, not every head of household in a county enslaved people, so fewer names are listed on the slave schedule than on the population census. Fortunately, the households on the two documents are typically listed in the order they were counted by the census-taker – meaning if you see the same residents’ names close by, in the same sequence, you’ve likely found the same person on the two forms.

In 1860, on a slave schedule in Forsyth, I found my ancestor listed on line 34 as A.J. Julian. He was 17-years-old at the time. There were four entries for his “Number of Slaves” column – four males, ages from 10 to 18.

There was more. When Abijah’s father, George Julian, died in 1858, he left a will.

One key to unlocking the identities of those who were enslaved is through the estate records of white families who claimed ownership of them. In many cases, wills give the first names of the Black men, women and children bequeathed from one white family member to another.

In his will, George listed property “with which a kind providence has blessed me.” To wife Adaline, George bequeathed “mules, oxen, cattle, hogs and other stock, and plantation tools, wagons, carriages and the following Negros…”

There were five enslaved people left to George’s wife, the will said, with the provision that “the negros and their increase” – that is, their children – would go to Abijah after his mother’s death. George Julian also left four enslaved children to Abijah, himself a teenager at the time.

And, in a separate item, Julian wrote that an enslaved woman and three children should “be sold” to pay his debts.

The will was difficult reading. Lumped in with oxen and kitchen furniture, plantation tools and wagons, were human beings. And “their increase.”

The will listed names of the enslaved kept by the family: Dick, Lott, Aggy, Henry, Lewis, Ellick, Jim, Josiah and Reuben.

The document was dated 1858 – close enough to emancipation that I might have a chance at tracing some of them forward, especially if they used the last name Julian. Perhaps there would be a chance of finding those same names in Forsyth in the 1870 census, when, finally free, Black people were listed by name and household.

Something kept happening, however, when I looked for those names. I’d see likely matches in one or two censuses, and then they disappeared after the 1910 census in Forsyth.

It took me a few minutes of research to figure out why I was losing track of the descendants of the people George Julian enslaved. It was a history drenched with blood, and it drew much closer to mine than I had realized.

The Search for Descendants of The Enslaved

ATLANTA

In 1912, Virginia native Woodrow Wilson became the first Southerner since the U.S. Civil War to be elected president. And the white residents of a county in Georgia, where my ancestors lived, unleashed a campaign of terror that included lynchings and the dynamiting of houses that drove out all but a few dozen of the more than 1,000 Black people who lived there.

The election was covered in the classrooms of the Georgia schools I attended. If the racial cleansing of Forsyth County was mentioned, I didn’t notice.

That history explains the difficulty I had looking for the descendents of the people enslaved by my ancestor Abijah. By 1920, their families and almost every other Black person had fled the county.

From left: The Forsyth County Courthouse in Cumming, pictured in 1907. Built in 1905, it was destroyed by fire in 1973. (via Digital Library of Georgia). The Atlanta Georgian newspaper reports on the lynching of Rob Edwards, September 10, 1912. (Source: Ancestry.com). U.S. President Woodrow Wilson.

They were forcibly expelled under threat of death after residents blamed a group of young Black men for killing an 18-year-old white woman in September 1912. A frenzied mob of white people pulled one of the accused from jail, a man named Rob Edwards, then brutalized his body and dragged his corpse around the town square in the county seat of Cumming. Two of the accused young Black men, both teenagers, were tried and convicted in a courtroom. They too died in public spectacle, hanged before a crowd that included thousands of white people.

There were also the night riders, white men on horseback who pulled Black people from their homes, leaving families scrambling and their houses aflame. The violence swept across the county, washing across Black enclaves not far from the farm where my ancestor, Abijah, lived at the time.

In 1910, the U.S. Census showed 1,098 Black people living in Forsyth. Ten years later, the 1920 census counted 30.

‘Night Marauders’

Until last year, I had never heard of this history. I had a dim memory of news reports about white residents in Forsyth attacking participants in a peaceful march for racial equality – not during the tumultuous Civil Rights era but in the 1980s. I watched video clips from an early episode of “The Oprah Show” – a telecast from 1987 when talkshow star Oprah Winfrey went to Forsyth to try to make sense of what was happening there. Some locals in the audience were unrepentant. Footage shows that crowds on the street and a man, to Oprah’s face, were not shy about using racial slurs on national television.

I learned about the 1912 violence in Forsyth after a genealogist who worked with Reuters sent me a note pointing out that my ancestor Abijah Julian appeared in Blood at the Root, a 2016 book that chronicled the bloodshed there. I already knew Abijah had enslaved people and adhered to the “Lost Cause” – the view that the South’s role in the Civil War was just and honorable.

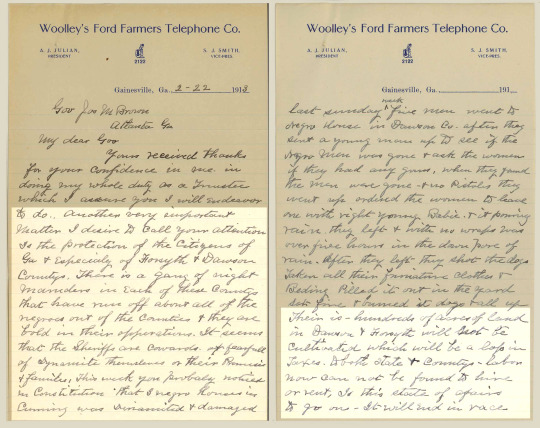

About four months after the terror in Forsyth began, Abijah wrote a letter to the governor of Georgia in February 1913. He was asking for help to quell the chaos unleashed by “night marauders” who had “run off about all of the negroes.” Here’s part of his letter: A letter Abijah Julian wrote to the governor of Georgia.

(Courtesy: Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.)

During that week alone, Julian wrote, “3 negro houses” in Cumming had been damaged by dynamite. The letter did not suggest any anguish for the Black people who’d been terrorized. What concerned Abijah Julian was his fields and who would farm them.

The Julian land stretched hundreds of acres across Forsyth and neighboring Dawson counties. Abijah told the governor that large swathes of land “will not be cultivated” because “labor now can not be found to hire...”

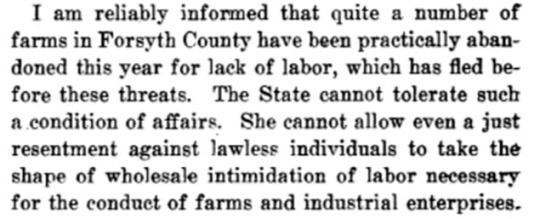

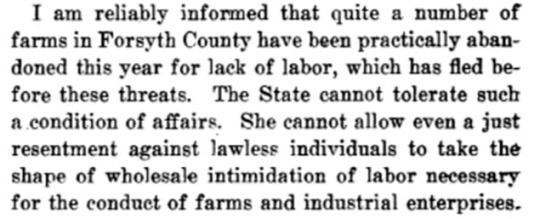

Gov. Joseph Mackey Brown referred to the situation Julian highlighted later in 1913, in a written message to members of the state senate:

After all, the governor continued, “there is no reason why farms should lose their productive power and why the white women of this State should be driven to the cook stoves and wash pots simply because certain people blindly strike down all of one class in retaliation for the nefarious deeds of individuals in that class.”

What happened in Forsyth was not unique. White people across the South had been pushing back against political and economic progress made by Black Americans after the end of slavery and would continue doing so.

In 1906, a white mob stormed downtown Atlanta, killing dozens of Black people and attacking Black businesses and homes. In 1921, a white mob destroyed a Black community in Tulsa, Oklahoma and, according to a government commission report, left nearly “10,000 innocent black citizens” homeless. The death toll was in the hundreds.

Once you begin to look, such violence stretches on and on, decade after decade.

Still hopeful that I might be able to somehow identify and locate living descendants of the people my family enslaved, I flew to Georgia last November.

‘Dick a Man, Lott a Woman’

While I was in Atlanta, I asked my mom and sister if they had time to talk about what I’d found. We sat one evening at the dining room table in my mother’s house, the same table on which we had once shared Thanksgiving dinners with Grandma Horseyfeather.

I had prepared two thick packets of documents that outlined our family tree, each with underlying records, to walk through the lineages of our slave-holding ancestors in three Georgia counties, including Forsyth.

I explained that my search began with a memory of walking with my mother’s father across some land our people used to own in Forsyth; and my grandfather casually remarking of the old well: “The slaves built that.”

“It added up from this one, just sort of little vague memory that I had of Brice gesturing at a well.”

The first question came from my sister, who is married to a Black man. Her voice was stretched thin with emotion. She asked: “Is there any possibility of doing the same for the people that our family enslaved?”

I’d found a man in Grandma Horseyfeather’s lineage who was a slaveholder and likely worked as an overseer in Jefferson County, Georgia. But neither I nor the genealogists we consulted could identify descendants of those he’d enslaved.

“So I’ve – I’ve tried,” I explained. “The issue is that the best details that we have are in Forsyth County, but in Forsyth County they forcibly expelled all of the Black people.”

There were, however, names of enslaved people who were bequeathed in the 1858 will of George Julian, Abijah’s father. At least two seemed to fit with a lineage I could trace.

Listed in the will as “Dick a man” and “Lott a woman,” they looked like a possible match for a couple living three households from Abijah Julian’s uncle in the 1870 census. Their names were listed as Richard Julian and Charlotte Julian. Was Dick short for Richard? And was Lott short for Charlotte?

I noticed that Richard Julian had an “M” in the column for Color. The M stood for Mulatto, someone of mixed race. Charlotte was 32 years old in 1870, an exact match for a 22-year-old enslaved woman listed on the 1860 slave schedule as belonging to George Julian’s widow. Richard was listed as 30 in 1870, which did not line up as neatly with an 18-year-old enslaved man next to Abijah Julian in the 1860 slave schedule.

A comparison of the 1870 census and the 1880 census reinforces that Reuters journalist Tom Lasseter is following the same family from one decade to the next. (Source: Ancestry.com)

Still, based on the mention of the names Dick and Lott in George Julian’s will, I followed the Black family’s lineage from one census to the next.

In 1880, Richard was listed as Dick. Lott was there, too, as Charlotte. And their ages were close to what they should have been – about 10 years older than in 1870. The children listed in each census gave me confidence I was following the same family. In 1870, four children were listed. There were three girls and a boy. In 1880, the oldest child was no longer there; she would have been 19 or 20 and may have married. But the boy and the two other girls were there, names and ages matching. The Julians had added four children to the family since the previous census, too, the eldest 8.

My sister’s first question after I traced our family tree that night lingered: “Is there any possibility of doing the same for the people that our family enslaved?”

One of the children in the 1880 census would provide the path.

The Shacks

The day I arrived in Atlanta, November 1, I chatted with my mom about Forsyth and our family’s history there. She’d mentioned something that took me aback.

“When we were talking about the farm, you said there was a slave shack, a slave shed?” I asked her the next day. “What was that?

It turns out my mother had visited the Julian farm when she was a kid. Someone had pointed her to a pair of shacks on the farm and explained that they were where the families of the enslaved used to live.

“It was a structure – by the time we came along it was still on the property but it was, like, a wooden structure that was falling apart.” Her voice became low for a moment. “And that’s what we were told that it was. And I think – I don’t know.” She paused. “I know my grandmother talked about teaching people how to read, or people in her family having taught some of the slaves how to read.”

My mom, a slight woman with a calm voice who works as a nurse with organ transplant patients, was uncertain about the details. “I’m not sure what the – it was just information that she was sharing, maybe to make it feel better that they had slaves. I don’t know.”

I went to dinner with my mom at a Thai restaurant the following evening. I’d been in Forsyth that morning, looking at some documents about the Julian family. She asked me if I learned anything new. I told her about two murders in the family – a pair of sisters slain by the husband of one – that had been covered in the newspapers in the 1880s.

That’s not what she was asking about. My mom looked up from her tofu dish and said, “I am uncomfortable with how little attention was paid to what that was.”

Under her breath, she continued: “The shed.” She meant the slave sheds on the Julian farm.

She said nothing for a few moments. And then she explained, “I was 11.” It was her way of saying she was young at the time. What could she have known about such things? It was the same age as my eldest son.

Why was I putting this at her feet? I thought.

What did she have to do with a white man, dead now for a century, who got rich and enslaved Black people? Where was that money? Not in her pocket. She was working late shifts and driving a beat up Toyota with a side mirror attached to the car by duct tape.

But the feeling of indignation was mine. My mother, a child of the 1960s who took us to downtown Atlanta for parades on Martin Luther King Jr Day, wasn’t being defensive. She was trying to work through what it all meant.

An Unexpected Meeting

Just before Thanksgiving last year, I reached out to a young research assistant at the Atlanta History Center. I’d heard she was tracing descendants of people who fled Forsyth.

Over the phone, I told Sophia Dodd that I was looking for people with the last name Julian. She said she had someone in mind. But first, Dodd would need to check with the person; we arranged to meet in Atlanta later in the month. There was a possibility the person would join us, she said, “but I also know they’re in the midst of traveling so that’s a little up in the air right now.”

I met Dodd at her office a few days before Thanksgiving, ready to ask her questions about Forsyth County.

And then another woman walked into the Atlanta History Center: Elon Osby. She wore a cranberry-colored top and glasses with red cat-eye frames. The 72-year-old Black woman with gray hair shook my hand and said, yes, she would gladly take me up on a cup of coffee.

I hadn’t expected her. I’d not even known her name – Dodd had protected her privacy while Osby decided whether to meet me. But there Osby was, looking at me expectantly. The three of us headed to Dodd’s office.

Without my census forms in hand, I felt exposed. Those family history packets – the ones I shared with my mother and sister – were a way to guide the conversation. And this conversation was with a stranger whose history with my family may have involved slavery. I told Osby that I regretted not having materials to give her.

Osby looked me over. She got to the point. “Is it that you feel that your ancestors were slaveowners of mine?” she asked.

Because I hadn’t done a family tree for her, I explained, I couldn’t be certain. During months of examining the lineages of American politicians, we had held to a firm standard: a slave-owning ancestor needed to be a direct, lineal ancestor – a grandfather or grandmother preceded by a long series of greats, as in great-great-great-grandfather.

As I built my own family lineage, I knew that the Julians were slaveholders. But when I worked with the genealogists on our team to trace the enslaved people named in George Julian’s will, they urged caution. What wasn’t entirely clear: Exactly who had enslaved Richard and Charlotte? Was it George, or was it George’s brother, Bailey?

I offered Osby the abridged version. If she were a direct descendant of Richard and Charlotte Julian, “they were enslaved either by my direct ancestor, George H. Julian” – Abijah’s father – “or his brother.”

As I finished my sentence, I realized the distinction may have been important to the journalist in me. But in this context, it was meaningless. What mattered wasn’t in question: Someone in my family had enslaved hers.

Osby turned to Dodd, the young white woman who’d been helping her research her family.

“First of all, let me ask this.” Osby said. “Do any of these names that he mentioned ring a bell with what you’ve done?”

Dodd answered quickly. “Yes, so I think that it’s definitely very possible that Charlotte and Richard were enslaved by George,” she said.

I asked Dodd if she had an account with Ancestry.com and whether she could print some documents. Together, we navigated to the 1858 will for George H. Julian and the 1870 census forms that showed Richard and Charlotte Julian.

Osby had explained that her grandmother’s name was Ida Julian. And Ida Julian’s parents were Richard and Charlotte Julian of Forsyth County.

Ida. Daughter of Richard and Charlotte. I would see it later. Not in the 1870 census, because Ida hadn’t yet been born. But there she was, listed in the 1880 census. Ida Julian, age 6. Ida Julian, listed in the 1880 census as a young child. (Source: Ancestry.com)

I later found a marriage certificate showing that Ida Julian married a man named WM Bagley in 1889. She was young, perhaps 15. By 1910, the census showed them living in Forsyth County, the parents of three girls and a boy.

The youngest of their children, not yet a year old, was a girl recorded as Willie M. She would go by Willie Mae Bagley, get married, and become Willie Mae Butts – the mother of Elon Butts Osby. The former Ida Julian, now Ida Bagley, in the 1910 census. Her daughter, listed as Willie M., would become Elon Osby’s mother. (Source: Ancestry.com)

After we had worked through the small pile of papers that Dodd had printed, I asked Osby what it meant to see some of those documents.

“It makes people real now. It just makes all of this more real. And it has started a journey for me,” she said, adding that there’s “no telling where it’s going to go.”

I asked her what her family said about Forsyth County when they discussed it with her as a girl. “They didn’t. They didn’t talk about it,” she said.

It wasn’t until around 1980, when Osby was about 30 years old, that she heard her mother tell a reporter the story of her ancestors fleeing the county by wagon because white people were attacking Black families.

“There wasn’t any conversation about it,” Osby said. “But she did talk about her grandfather had this long hair, straight hair, and they would comb it.” That was Richard Julian, Osby’s great-grandfather, the man listed as a “Mulatto” on the 1870 census.

She paused and stared at my face for a moment.

‘I Don’t Think You Can Get Justice’

When Elon Osby’s grandmother, Ida Bagley, and her family fled Forsyth, they left behind at least 60 acres of land, she said.

They made their way to Atlanta after 1912, the year of the carnage. There, in 1929, her grandfather, William Bagley, bought six lots of land in a settlement of formerly enslaved people known as Macedonia Park, according to the local historical society.

It was located in Buckhead, long among the most expensive neighborhoods in Atlanta. The Black residents of Macedonia Park worked as maids and chauffeurs for white families in the area, as golf caddies and gardeners.

Osby’s grandfather made money as a cobbler and local merchant. Her parents opened a store and a rib shack. Her father was also a butler for a wealthy white family, her mother a cook. The area became known as Bagley Park, and her grandfather, according to a historical marker now at the site, was considered the settlement’s unofficial mayor. William Bagley, Elon Osby’s grandfather, was known as the mayor of Bagley Park, a Black enclave in Atlanta that was later razed by the county.

(Courtesy: Elon Osby)

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, nearby white residents – members of a women’s social group – petitioned the county to condemn and raze Bagley Park, ostensibly for sanitary reasons. It had no running water or sewer system. The county, which had not provided those services, agreed, forcing the families to leave. They were compensated for the land, but it’s not clear how much, and in the process they lost real estate in what is a particularly affluent quarter of the city.

Osby’s family had again been pushed off its land. The settlement was demolished and replaced by a park, later named for a local little league umpire. Last November, the city of Atlanta restored the area’s name: Bagley Park.

In thinking about Osby’s family and my family, I found it was impossible not to compare them – and the role slavery played in our respective paths. In 1860, Osby’s ancestors were enslaved and working the fields of Forsyth County. In 1860, my ancestor Adaline Julian, widow of George and mother of Abijah, reported a combined estate value of $19,020. She was among the wealthiest 10% percent of all American households on the census that year. And that wealth didn’t include her son’s holdings. Then just a teenager, Abijah had a personal estate of $4,828, according to census records. That amount lay largely in the value of the enslaved people bequeathed to him by his father.

In 1870, Osby’s ancestor, Richard Julian – free for only about five years – was listed on the census as a farmhand, with no real estate or personal estate to report.

In 1870, Abijah Julian – despite having “lost” those he had enslaved – still had a combined estate of $4,655. That put him in the top 15% of all households in America, census records show.

Osby said her parents used the money they got from the government after being forced out of Bagley Park to buy land in a different part of Atlanta. They continued to work hard. Her father was hired as an electrician by Lockheed, and her mother ran a daycare business.

Osby spent a career working in administration. She said she started as secretary for the manager of the city’s main Tiffany & Co location in 1969, then worked in various city government offices, and now for the Atlanta Housing Authority.

After she’d finished telling me about her family and herself, I asked Osby whether she would mind me recording some video with my cell phone. I asked once again about her family’s reluctance to discuss Forsyth. She repeated that Black parents had long kept such things quiet. I noticed she added the words “rape” and “lynchings.”