#italian neorealism

Text

Proud of this one I hope people like it!

#uquiz#mine#film#film quiz#personality quiz#uquiz link#french new wave#Italian neorealism#Hong Kong new wave#japanese new wave#film movements#cinephile

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

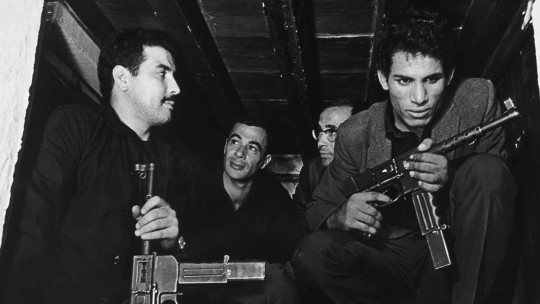

ITALIAN NEOREALIST CINEMA MEETS THE FERVENT SOCIO-POLICIAL CLIMATE OF '50s NORTH AFRICA.

FILM: "The Battle of Algiers" (1966)

CINEMATOGRAPHY: Marcello Gatti

DIRECTOR: Gillo Pontecorvo

SCREENPLAY: Franco Solinas

GILLO PONTECORVO: "The writings of Frantz Fanon were also very important for Franco Solinas, the screenwriter, and myself. We were there for a few months before the liberation and we saw everything, the hope and the joy, and we remember young people talking on the street all night. During the long months of preparation and of talking with the people, we saw that the struggle against colonialism diminished the mental state and the customs of the people. To fight colonialism they had to change themselves from what colonialism had made them."

Sources: www.proquest.com/docview/204845804, The New Arab, Los Angeles, Times, X (formerly Twitter), The New Review of Film & Television, various, etc...

#The Battle of Algiers#Maʿrakat al-Jazāʾir#The Battle of Algiers 1966#Italian Cinema#Italian Neorealism#1960s#Neorealism#Neorealist Cinema#Algerian#Cinema#معركة الجزائر#Foreign Films#Movie Stills#60s Cinema#Italian films#World Cinema#Italian-Algerian#Algerian Revolution#War Films#Film Stills#60s#Sixties#La battaglia di Algeri 1966#Algerian War#La battaglia di Algeri#Sixties Cinema#Gillo Pontecorvo#Cinematography#1966

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

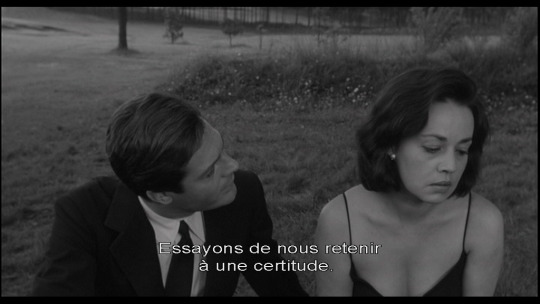

La Nuit/La notte (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1961)

#michelangelo antonioni#1960s movies#marcello mastroianni#jeanne moreau#iloveyou#i love you#subtitles#la notte#la nuit#néoréalisme#neorealismo#italian neorealism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

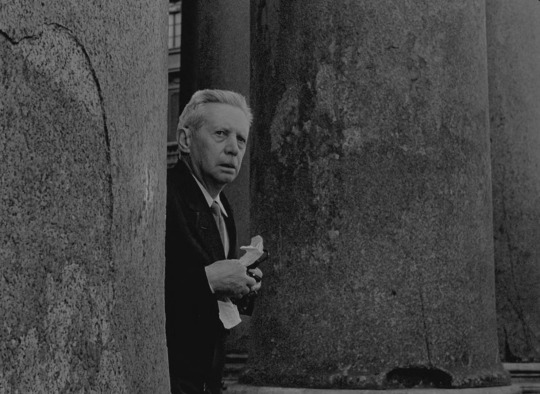

Umberto D. (1952) directed by Vittorio De Sica

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Accattone (1961)

A subset of postwar Italian cinema is defined by listlessness. Yet whereas something like Fellini’s Il bidone still finds rambunctious frivolity in these layabouts and ne’er-do-well youths, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s feature debut (how!?) looks at a blasted Rome with a bitter gaze. Aside from some tongue-in-cheek gallows humor of the opening scene, all laughter in this film is a scream into the void. Accattone’s posse laugh to keep from crying over a man mock-eating flowers as they starve, waiting for a meager plate of pasta to serve eight to finish cooking. Joining up with the local thief Balilla to earn a few lira, Accattone and the boss swap jabs at how bad henchman Cartagine’s feet smell because he hasn’t washed in a long time. Everyone laughs too hard, on the edge of hysterics. This small drama plays out in an outer Rome which resembles a trash heap: crumbling buildings dot neighborhoods, rubble litters the streets, and bottles that girls clean to earn some cash are stacked everywhere. The police exist to harass some people arbitrarily, miscarry justice, and pack away people seeking money illicitly because they feel there is no alternative. Spying on his estranged partner Ascenza, Accattone looks at her family through a hole in the wall of a derelict building: Roman ruins, but of a less storied chapter in Italian history than produced the Coliseum. And when one of Accattone’s associates prays mockingly to whatever patron saint may exist for starvation, the camera tilts reverently upward but only finds a blank and anonymous structure. These people have been abandoned in one sense or other.

But despite these tragedies, make no mistake: Accattone is a rat bastard. He decries all gainful employment, abuses the women in his life, and claims that forcing them to work as prostitutes is his own work. Money is always squandered whenever he has it, and lamented when he doesn’t. As with others, he is disillusioned by the world around him, and he’s chosen to lash out in blind rage at all for it. His cruelty is apparent in twin tracking shots in which he pursues first Ascenza and then Stella, his new victim. They move toward the camera, this choice making him inescapable, and similar dynamics play out, if the aggression is at different temperatures. In portraying both his central character and the situation at large in alternately sympathetic and horrified manners, Pasolini indicts everything about this situation.

THE RULES

SIP

A Bach piece starts to play.

Someone makes a bet.

Someone starts to sing.

BIG DRINK

Someone says they are ruined.

A section of Rome is named.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Released on this day sixty years ago (22 September 1962): Mamma Roma, the highly politicised poet / provocateur and visionary Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini’s follow-up to his scorching debut Accattone (1961). It stars Italy’s fiercest actress, Anna Magnani and all the essential components of Magnani’s persona are represented in Mamma Roma: Earth mother. Feral she-wolf. Mother Courage. Mary Magdalene. Noble whore. Fallen woman. Monstre Sacrée. Gritty but kind-hearted ageing prostitute. Vital life force. Every Italian woman who ever wore a black slip and shouted at someone from her tenement balcony. Magnani portrays title character Mamma Roma (sometimes referred to as “Signora Roma; we hear her actual surname - Garofalo – just once). The name implies she’s meant to personify the earthy, sensual, battered but resilient essence of Rome itself. The movie represents a zenith in twentieth century European art cinema! I would have loved to commemorate this anniversary with a Lobotomy Room screening. Pictured: Magnani and Pasolini during production of Mamma Roma. These two are royalty!

#anna magnani#pier paolo pasolini#mamma roma#italian neorealism#italian cinema#italian actress#lobotomy room#she wolf#earth mother

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ermanno Olmi’s “Il Posto” September 13, 1961.

#Ermanno Olmi#Il Posto#1961#Sixties#Foreign#🇮🇹#Coming of Age#Italian Neorealism#Drama#Sandro Panseri#Loredana Detto#4/5

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#manifesto#julian rosefeldt#2015#cate blanchett#éloge de l’amour#werkzeugkasten der geschichte#obst & gemüse oder der kunde ist könig#fisher king#about photography#oberhausen#italian neorealism#do not trust art

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Il posto (Ermanno Olmi, 1961)

#Il posto#Ermanno Olmi#1960s movies#Italian cinema#Film#Italian neorealism#cheers#new year#old year#black-and-white film

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria Michi: Roma città aperta, dir. Roberto Rossellini, 1945

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bicycle Thieves/ Ladri di Biciclette (1948)

Even before you've probed into Ricci, the filmmaker makes sure you are rooting for him as soon as you hear him worrying about his pawned bicycle. You see his wise young son and the tiny baby and them having to do without bedsheets so that he can get the bicycle and start working. Future looks good for him until you remember the title of the film. Going by contemporary pace, the action is bound to go slow, but you are there with Bruno and Antonio every step of the fatiguing way as they look for the precious bicycle. Bruno's joy at the stretch of the mozzarella cheese makes you smile too and so does Maria's affectionate appraisal of Antonio when he dons his uniform the first morning of the work. I'll not dare to say that I know much about filmmaking, but what i watched was simple, real, heartfelt, and what if it is set in post-second world war Italy? You can still relate to it. You want Ricci to find the bicycle and be able to live the life he deserves to, but Italian neorealist filmmaker Vittorio de Sica will not give you the ending you wish for, because life is not like that, is it? You too find something pricking at your eyelashes when you see father and son walking away, ashamed, humiliated, despairing but still bound to live on.

#bicycle thieves#ladri de biciclette#vittoria de sica#italian neorealism#film#filmmaking#currently watching#impressions not reviews

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Scenes from movie ROCCO AND HIS BOTHERS. Directed by. LUCHINO VISCONTI.

Rocco e i suoi fratelli.

#Italy#movie#classic#luchino visconti#Alain Delon#Annie Girardot#Renato Salvatori#Drama#Boxe#1960's#Neorealistic#italian neorealism

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Class of 2023: My Favorite Movies

Frankenstein vs. Baragon

I kicked off this “academic year” (the period of time since my last update to the tally of my favorite films) with a literally once-in-a-lifetime movie-watching experience. Thai slow cinema master Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s latest, Memoria, was playing ever so briefly at the Sie FilmCenter in Denver as part of the movie’s uniquely bold “one theater at a time” world…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Italian Neorealism’s Influences on Goncharov

Winter is coming to Naples.

Sure, Goncharov is a Russian/Italian fusion movie partially because Italy has such a mafia presence, and that’s the main plot, but also because the combination of Italian and Russian cultures allows for such a great evolution of the Italian Neorealism art style.

While admittedly, Goncharov’s actors are not randos off the street (this whole saga has reminded me that Pacino has 2 Tony awards and De Niro has a Presidential Medal of Honor. wild!), the movie shares the Neorealistic focus of those on the down and out, or on the fringes. Sure, traditionally, it was more the ‘poverty’ side of the down and out, but if we look even farther back to, say, poetic realism, then we see a criminal element.

Scorsese is a man who loves an excellent almost Greek tragedy, a true fatalistic plot where no one gets out alive. No one exits the rooftop in his The Departed and Goncharov is an earlier look at his belief that everything comes to a head at ultimate bloodshed. Likewise, in the Italian Neorealism classic Bicycle Thieves, one of Scorsese’s favorite foreign films (https://www.huffpost.com/entry/martin-scorsese-foreign-film-list-colin-levy_n_1382131), there’s no escaping the savage destitute poverty.

Aesthetically, though, is where the Russian influence of Goncharov really elevates classic Italian Neorealism. It’s not only the cold but also the bleakness of the motherland that’s coming to Naples. Italy in 1973 much farther from Mussolini and its realistic period than Russia is from its continuing stagnation under Brezhnev. So we see those cold grey tones and dreadful sepia filters almost follow Goncharov and Andrey out of St Petersburg to reinforce, in the visuals, that decay, the lack of upward motion not available to our protagonists or the Italian ones of Bicycle Thieves.

The down and out, mean themes of Italian Neorealism iterated on with bleak Russian visuals. Chef’s kiss (pun intended)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

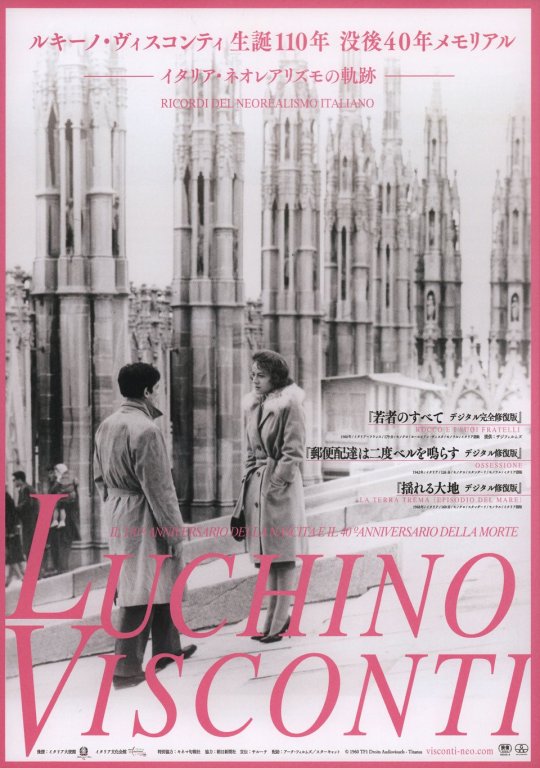

Rocco e i suoi fratelli (Rocco and His Brothers, 1960) Japanese poster

#rocco e i suoi fratelli#rocco and his brothers#alain delon#annie girardot#luchino visconti#italian neorealism

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Il bidone (1955)

Desperation and despair are common features of postwar Italian cinema and the neorealist movement that emerged from the ashes of Mussolini’s Italy. Disillusioned youths and desperados are nothing new, but Fellini’s character study here captures the self-sabotage of living a lie in order to support others you love. Carlo and Augusto both have tenuous connections to their family. Carlo dotes on his wife and daughter under the appearances of being a traveling salesman, and Augusto is estranged from his daughter but hopes to reenter her life. While they can use their ill-gotten gains to attempt so, both are found out to be liars and cheats of the worst sort. The film really builds this up, our central swindlers cheating the poor out of countless Lire be it in the guise of the clergy or as government housing workers. Fellini wields a double-edged blade here, vilifying the criminals themselves through their immediate actions, but also the Roman Catholic Church and the Italian government for their corruption and indifference and ineptitude in no particular order. These men are cruel, but they are operating in a vacuum of incompetence. And yet there is space for forgiveness and a sort of empathy. Carlo fully recognizes all too late just how futile his position is, how he has trapped himself as a sheep in wolf’s clothing, and Augusto is too far beyond the pale for redemption. He sees a chance with a young girl, attempting to tell her that she has it good in some form, but his turning point is marred by one last attempt at making it large by stealing the swindle from his cohorts. The greatest swindler of all can still be trapped.

THE RULES

SIP

Someone says 'Monsigniore'.

The group assume a new false persona.

Someone is caught in a lie.

BIG DRINK

Our swindlers don vestments.

Someone mentions a sum of money.

2 notes

·

View notes