#it boggles the mind how many people really think vengeance was a thing

Text

Anders, not being used to his anger about oppression getting 100% understood and justified by another person, and also being a victim of religious guilt tripping that had led many other mages to intense self-hatred and even suicide: I corrupted Justice into Vengeance

Justice in the Fade: I am Justice.

And then 0 evidence of Vengeance existing is ever presented. Interesting..

#anders has trauma that's fucking him up#and he didn't exactly know what tf he was doing with justice#so things are a mess now#anders#justice#my posts#the narrative needed a corrupted justice to justify that the chantry getting what was coming was indeed bad#bc good people don't rebel and just die i guess#long live the violent status quo and centrism /s#yes I'm still angry about that#sorry I'm full of salt#it boggles the mind how many people really think vengeance was a thing

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

"House of Earth and Blood" by Sarah J. Maas

Oh my, Sarah J. Maas. I loved this book. I really, really loved this book. At 799 pages, it's the longest book on my "read" list this year, and it was worth every page.

"House of Earth and Blood" is set in a modern fantasy world and tells Bryce Quinlan's story of heartbreak, vengeance, understanding, acceptance, friendship, love, and redemption. Her story had everything, and I felt everything.

Bryce Quinlan, for the majority of "House of Earth and Blood," is a twenty-five year old half-human, half-Fae bastard daughter of the Autumn King of Luthanian. Her best friend is an Alpha wolf named Danika. Her brother is the crowned prince of the Fae, her mother and stepfather (who she considers her father) are human, and her lover turns out to be a fallen angel - "Fallen," because he was the commanding general in a failed rebellion that took place two hundred years prior to the events in this book. And if you think that's complicated... Just you wait.

Bryce is a hardened, stubborn, young woman just trying to live her life in her broken world. She's the stereotypical Maas female protaganist. And per usual, I found it super hard to relate to her. Maas portrays her female characters as secretly messed up, but tough, and wanting everyone to believe it by projecting sarcasm, selfishness, and mystery onto those they interact with. In my opinion, this makes them less fierce. Vulnerability, imagination, kindness - these are the things that read, to me, as being truly feminist. Not because women are dainty, passive creatures, but because we can be vulnerable and still be strong. We are sensitive AND resolute, imaginative AND mysterious, helpful AND capable. Bryce made me cringe with the way she acted towards people who were trying to help her and befriend her. The forced fierceness translated as petty angst. Granted, she was justified in her angst, but that merely made her average and sometimes even cruel, in my opinion. And I found it extremely hard to relate to her in the beginning of "House of Earth and Blood."

I was incredibly relieved when Hunt Anthalar, the Shadow of Death and Bryce's eventual shadow, finally put Bryce in her place by calling her out on her attitude. I get that she was hurting, and everything I disliked about her in the beginning was redeemed by the end of the book, but it still took me an unusually long time to actually start liking her. I also found it super hard to relate to her because of those damned heels that she insisted on wearing. Short, tight-fitting dresses and sky-high heels when you know you're in the middle of an intense investigation and at the mercy of an unexpected attack at any moment - it would definitely not have been my outfit of choice for every single day preparing to do everyday things.

Reading through Bryce and Hunt's interactions, though, made it so much easier to genuinely like our protaganists - both of them. They brought out the best in each other, and that was ultimately Bryce's redemption for me.

Moving on: There is so. much. to unpack in this entire story. There are so many characters, names, places, relics, rules, rulers, hierarchies, and stories within the main plot. It was incredibly confusing to try to keep up with everything during the first half of the book - especially because Maas stuck to her M.O. and used names that are not really names, but several letters put together to create something that might, in some world, resemble somewhat of a name. She also wasted no time in throwing all this information at the reader right at the beginning, so it was thoroughly mind-boggling and I forgot about half of it when that information actually became relevant - which it did later on in the book.

Thankfully, I had help in consolidating the information in the form of bookmarks, which I used at least once for every chapter - if not, every other chapter. I honestly don't know how I would've read this without going back to each part of the book where those things were mentioned to recap. If you read this, you will probably need to take notes to help guide you through all the backstories and histories of every character and place that's mentioned. Because it all does become relevant, and is not, in fact, random and extraneous information that I thought it to be in the beginning.

Also, if you read this, I would suggest practicing patience because there is a bit of back and forth in the book. I found myself getting so frustrated that the climax was being dragged about, and was furiously reading to finally arrive to it. I will say that the extra-long buildup was definitely worth the wait - and I was not expecting it at all, despite all the back and forth in every direction.

The ending of "House of Earth and Blood" was breathtaking, heartbreaking, and so, so powerful. I was in awe and shock, and I was sobbing before I even knew what was happening. I couldn't have imagined a better ending to this novel, and I'm still reeling over it two days later. So much so that I'm finding it hard to be interested in my current novel.

The ending, however, was also very open-ended. There was a lot there that was not addressed that I felt should have been immediately addressed. Like, where were all the other characters during and after that final, big scene? You know the scene I'm talking about. What happened to them? Where did they go? I still have no idea, but I'm hoping those answers will make it into the next book in the series...

Maas really did it in "House of Earth and Blood." She wrote an incredible story, and if I know her by her writing, this series is only going to get more interesting. I am completely blown away and so excited to get my hands on the next book, "House of Sky and Breath."

Before I leave this review, I do want to take time to note a couple of different things I noticed while reading, like Maas' use of the term "unearthly." Technically, everything on this planet (which is not earth) is unearthly and it was funny that the oversight was made. It wasn't a big deal, but it would've been nice for her to be a little more imaginative. There were also a lot of modern references and apparatuses that were used, including mobile phones, guns, and the types of clothing. This was an adjustment on my behalf because it was a new take on my normal fantasy reading, but I didn't dislike it once I got used to it.

I also want to mention that unlike Maas' other novels, this one lacked the steam that Maas is usually known for. There was barely one - not even one - whole sex scene in this entire novel. I was a bit perplexed because I was expecting, and hoping, for Hunt and Bryce to finally do the damn thing. Don't get me wrong, there were super intense moments where there was clearly something, but they never ended in anything.

Overall, yes. Just yes on this book. A resounding "YES!"

0 notes

Text

Crashing into you

Sooo, I have no idea where this concept came from but here is you and Harry surviving a plane crash only to find yourselves stranded on an island (featuring best friends to lovers and who knows what else). There is more to come after this part, I’m just really busy with uni at the moment, so smaller pieces at the time it is. Please leave some feedback if you have any, or tell me what you would like to see happen in future parts! Happy reading xx

It wasn’t supposed to happened.

None of it was. Not the birds. Not the fire. Not the nose-dive.

And you weren’t supposed to be there either. Weren’t supposed to find yourselves floating 35,000 feet over endless stretches of sea when it happened. Not you and certainly not Harry whose presence was only the result of his boundless generosity.

It was a last minute trip on your part, an emergency response to the calling of a friend back in London; they’d gotten hospitalized and you were their emergency contact, pretty simple maths. Your assistance was irremissible and since it was cutting your time short with Harry, he didn’t hesitate before offering both his support and an express flight aboard some kind of private jet. None of you knew it at the time, but that decision turned out to be a twisted expression of serendipity, a very sick jock that the universe wasn’t supposed to make.

Except it did happened and there was no escaping the cataclysm that ensued.

***

The cabin of the small plane is plunged in peaceful silence, the deep whir of its engines and the soft snores wafting through Harry’s nose the only white noises filling the space. There is no fussing toddler, no businessman talking loudly on the phone, no arguing couple; just you and Harry, one flight attendant and two pilots. Everything around you looks pristine and expensive, from the champagne you were offered but declined at the beginning of the flight, to the refined suede upholstery covering all the seats.

You’re not used to the luxury, and frankly, neither is Harry.

He doesn’t use private planes very often, doesn’t think it makes much sense to waste all that toxic kerosene when commercial flights do the job perfectly, and doesn't like how they make him feel like the diva some people mistakenly make him out to be. But for you he’d bend the rules. For you he’d bend over and backwards to assuage any of your pains and worries. You had been so on edge when you told him about your friend, so desperate to be there for them, he had just wanted to be there for you in turn.

That’s why the two of you hopped in this small aircraft nearly four hours ago, with his hand drawing comforting shapes on your back. Now, you find yourself absentmindedly nipping at your nails, overthinking ever possible scenario that could unfold once you land and find your friend. In deep conversation with your conscience, you’ve been looking out the small window to your right, as if any of the two blue immensities painting the horizon knew all the secrets that you needed. They don’t; if anything, they bring their own mysteries to an already confusing world.

The atmosphere inside the plane is so inert, it feels like someone pressed the pause button. The flight attendant has remained quietly by her station, waiting for any signal that would indicate her presence required, and the pilots haven’t piped a word since their polite ‘have a lovely flight,’ when you first boarded the plane. The little company wouldn’t bother you so much, if Harry hadn’t fallen asleep thirty minutes in, leaving you to your own devices. You figure you can’t be too grumpy about it though, he did just rent a plane for your sake after all. Plus, his unconscious state has allowed you to ogle his sleepy figure for hours without being noticed, a treat you’re rarely privy to on top of being a nice distraction from your current troublesome thoughts.

Three years. Three years you’ve been a very dedicated friend to him and he to you. Three years of holding each other’s hand through any hardships and laughing till you’re blue in the face; three years of always supporting each other in your craziest undertakings and inspiring each other to be the best version of yourselves. You two are an indestructible pair and your friendship is the purest, most sacred thing you were given in this world.

Except, it’s also been three years of mind-boggling and consuming feelings that can’t be quelled and have no limits. Three years of secret glances when he’s too focused on something else to notice. Three years of talking yourself down from those feeling, but to no avail; they keep coming back full force and with a vengeance. It quickly became a full time job really, an art you mastered over time. At first because he was happily in a relationship, so there was no speculating whether your affections could be returned. Then once that ended, you were already so wired to ignore the skip of your heartbeats when he looks at you tenderly, or the soft and sometimes borderline ambiguous cuddles he gives you when he’s had one too many Margaritas; that the fantasy of him loving you the way you do was just unfathomable, you never even considered speaking up about it.

But these were your three years, not his.

You let out a deep sigh, as your musings once again circle back to your unrequited love. You wish you had more control over them, could limit them to sleepy fabulation sweetening your mind right before you surrender to unconsciousness. But alas, them come and go as they please, slip into your mind at any inopportune time, often betraying you by pigmenting your cheeks in cerise-colored bashfulness. Even now, in the stillness of the pressurized cabin, as your eyes settle back on his slouched form in the seat opposite yours, your skin can’t help but heat up in fondness.

Before you can get too lost in the soft eyelashes caressing his cheekbones, or the cupid bow shaping his pink supple lips, or the way a few of his mischievous curls are dandling in front of his face, slightly fluttering at each soft puff coming out of his mouth…yeah, before you get too lost in all that, you reach for the small bottle of water sitting on a small table.

You barely have the cap unscrewed before a massive tremor shakes the whole aircraft, spilling half of the bottle’s content on your lap. Your hand immediately white knuckles the armrest of your seat, your eyes widening in fear and frantically scoping the cabin for the flight attendant or anyone that could tell you what the hell is going on. Then the panic pumping through your veins prompts you to check on Harry and wake him back to alertness, but to your relief, he’s already groggily shaking the slumber from his limbs with a deep frown on his face. "Wha’s goin’ on?"

If dread wasn’t firing each of your nerve-endings, you’d find his grumpy look and slurred speech quite adorable, but the sight of the frazzled-looking stewardess coming towards you is sending a different kind of chills down your spine. These people are trained to maintain composure in all circumstances, so her trepidation can only mean one of two things: she’s either very new at her job or there is clearly a cause for concern.

"You two need to fasten your seat belts immediately," she speaks hurriedly.

"Sophia, what’s going on?" Harry reiterates his question with more alarm.

"We’ve collided with a flock of birds. We don’t know the extent of the damage yet, so I need you two to buckle in."

You and Harry share a worried look then, still confused about the situation. The plane has regain some semblance of stability, it seems, but Sophia’s anxious behavior doesn’t sooth your nerves one bit. She makes a quick exit back toward the cockpit, probably to discuss the ordeal further with the pilots. You gulp your uneasiness away, fidgeting on your seat as your hands blindly feel around for the safety belt, but the image greeting your eyes as they veer back to the window has your heart dropping to your knees.

Lambent orange and red flaring from the engines and lapping at the wing. Black smoke leaving an angry trail behind the plane and fogging up the windows.

"Harry," you barely manage to breath his name out and the urgency of your tone has him straighten up in his seat. "Harry the wing is on fire." You twist your head back towards him only to find him jumping from his seat to plop down next to you. The absolute gleam of terror swimming in your eyes makes his blood turn cold, so he quickly takes your hand in both of his before glancing at the carnage taking place outside. He gulps in apprehension before buckling his seatbelt and checking that yours is clasped in as well.

"Fuck, okay, it’s okay, love. Everything’s gonna be okay." It’s more prayers than reassurances tumbling out of his mouth, squeezing at your hand in plea, and a couple seconds after his utterance the tremors resume with greater intensity. You both can feel the aircraft slanting downward as everything around you start shaking as though you were caught in an earthquake. Except, you couldn’t be further from earth at the moment, and the shaking is not going to just pass after a while.

Objects start falling and rolling down all over, the tray of complimentary drinks tumbling down from the back of the plane to crash at the front. You and Harry are wrapped up in a protective embrace, tucking your faces in each others neck to avoid impact and because you’re both too afraid to look at the unfurling chaos. You can feel your seatbelt straining against your lower belly in a dire attempt to keep you in one place, but as the plane starts plummeting for good, top becomes bottom, right becomes left, and your bodies become masses thrown around at the hands of gravity just like everything else.

The last thing you hear before everything goes south is a defeated ‘brace for impact’ coming from the small intercom of the cabin. You feel the brutal shock of the plane hitting smooth surface if it weren’t for the speed of the collision, and then it’s just water.

Water everywhere. Water enveloping your body in a frigid clutch, water weighing you down as it imbibes every fiber of your clothes, water invading your retinas and blurring your vision. Water seeping through your mouth, pouring into your lungs when you feel the skin at your shin torn by sharp metal.

You vaguely hear your name being shouted, but the shortage of oxygen in your system makes you feel delirious. At this point you barely have enough energy to fight unconsciousness, much less the threat of your crumbling surroundings. That’s how you don’t feel the hand grasping at your shoulder and hosting you up on a floating piece of broken wing. Harry is holding onto it for dear life as well, muttering more prayers and encouraging words for you to please stay with him but soon you are both overthrown by your unconscious, slowly drifting away on the makeshift buoy.

***

When Harry regains consciousness, the first things he feels is hard grounds underneath him. His ears are ringing, his throat is sore and his mouth feels dry, not to mention the splitting headache jackhammering at his skull. Groaning and frowning at the pain, that’s when he realizes that the ground against the skin of his cheek isn’t completely hard, but rather granular at the touch. Slowly, he brings his hands higher near his face and flattens them to hoist himself up. Once on his knees, he finally blinks his eyes opened, squinting at the blinding luminosity of the sun. And then it’s just sand.

Sand everywhere. Sand stretching miles into the distance. Sand itching at the joints of his fingers, sand creeping inside his shoes and clothes, sand weaving through his hair. Sand obnoxiously lingering on his lips, and as he tries to brush it off with the back of his hand, he has to spit some out of his mouth after realizing that said hand is also covered in it.

How did he find himself stranded on a freaking island? How did this happen? How could he be one minute safely by your sides, helping you through a tough situation, and then the next, thrown into the deep end - quite literally - scrambling for his life because some dumb birds decided to crash in the engine of the plane? Why him, why-

It’s a jolt to his brain then, an electric shock firing his body up to a standing position when the thought of you clashes in his mind. His breathing picks up considerably as he recalls the last time he saw you, passed out on the broken part of the wrecked airplane. He’d passed out soon after you as well, but what had happened since then? Had you find your way on this desolate beach as well? Or had your unconscious body slipped back into the water and sank all the way to the ocean floor until you reached that hidden museum of all the things and beings that fell victim to the sea?

Harry shudders at the thought. No. He’s not loosing you, now or ever, he convinces himself as he frantically jogs along the beach. Not when he never got his chance. His heart is lodged in his throat and threatening to escape at every passing second. Not when he still has unfinished, or rather, un-commenced business with you. Sweat drips down his face in searing droplet, a faint sting above his left eye barely registering in his frantic mind. Not before you know his last secret. His breathing is starting to get scarce until finally, finally his blurry eyes fall upon a figure stretched out on the sand, waves still licking at their feet. His job turns into a sprint as he begs for them to be you and for you to still be alive, desperate cries of your name echoing in the wilderness. "Please be okay, please be okay, fuck I need y-"

His relief is short lived once he takes in your passed out form, the blueish hue of your lips and the very lack of movement of your chest, twisting his guts in a painful knot. Harry abruptly falls to his knees next to you and brings his ear to your body hoping for any indication that you are still breathing. He fights the onslaught of hyperventilation that threatens to take over his body when he finds none and quickly checks your pulse at your carotid. His eyes pinch in brief respite: it’s faint but it’s there.

His brain almost goes into overdrive as he tries to recall everything he knows about CPR before his hands instinctively start pressing at your chest as though they already know what to do. It gives him time to absorb all the composure he can muster and think more clearly. He’s got to keep your heart going, that much he knows, and if you’re not breathing, it’s probably because you’ve got water in your lungs. Upon the realization he briefly stops the cardiac massage to pinch your nose and blow as much air as he can into your mouth.

For the next couple of minutes he does just that, alternating between insufflating oxygen through your mouth and pressing at your heart. His own breaks every time he pulls away from your lips and they still don’t pink back up to their usual lovely cherry color. Tears roll down his face in a constant flow, forcing him to wipe his face against the material of his shirt at his shoulder; there is no way in hell he is stopping his action for even a fraction of a second. He’ll die trying to save you before you die on him, and then he’d kick you ass from heaven down to hell for even thinking of leaving him behind.

All of a sudden you start coughing wet sounds from your throat, your body jolting from its spot on the sand. Harry’s never been so happy to hear someone choke (on water, that is) and as you turn your body sideways to let out all the excess of water clogging your chest, he closes his eyes and tilts his head back towards the sky in gratitude. "Thank you, thank you, thank you," he whispers out in relief, before regaining his breathing and focusing back on you. He draws soothing circle against your back as you cough the last bit of water out of your mouth, pushing your hair out of your face to give you space to breath. Lord knows you need it.

"It’s okay, pet. You’re okay, you’re alive. Fuck you’re alive, I can’t- please don’t ever do that to me ever again, you hear me?" He rambles at you as he cups your face with two trembling hands. He is in shamble in front of you, the high he was caught up in, in his order to save you finally dissolving and leaving only but shock and despair in its aftermath. You’d come this close to die in his arms, you both realize. This close from your life being highjacked from his in the middle of nowhere and the thought turns your blood even colder than it already is.

"‘kay, m’okay, Harry. We’re both okay," you reassure him too, and just hearing the sound of your hoarse voice is enough to calm him some. He brings you in a bear hug, tucking your face underneath his chin and draping is other arm over your back. You don’t hesitate before you return his embrace by wrapping your arms around his waist.

For a hot minute you remain intertwined in silence as you breath each other in and revel in the fact that you both survived the crash. Once your heartbeats have lowered down to healthier levels, you slightly part from each other and your eyes glisten as you lock them with his. "You saved my life, Harry," you whisper out to him with a tender caress at his cheeks, trying to ignore the small cut at his brow bone. "I just- thank you, thank you so much."

He answers with a small shake of his head, "don’t thank me, pet. I can’t imagine what I woulda done if y- if I couldn’t-" he struggles to let the words out and his face turns into a grimace at their implication. "M’just so relieved you’re alive, I’m the one thankful for that if anythin’," he ends up saying against the palm of your hand before leaving a small peck there.

As you move to stand up, you feel a sharp sting at your shin as soon as you apply pressure on your right leg. Looking down, you spot a gash at the skin, it’s not too profound that you won’t be able to walk, but it definitely needs tending to if you don’t want it to get infected. You let out a quiet ‘fuck’ in frustration before catching the look of concern of Harry’s face. "It’s fine," you brush it off, "just gonna need to clean it out. That cut on your face as well," you motion at his injury and he brings his hand up to feel out the cut in confusion. He hadn’t noticed the small wound, you realize. "Right, yeah," he answers after inspecting the patch of blood coating his fingers now.

Now that the shock of the situation is slowly dissipating and that reality is setting in, you both start thinking about the next course of action. You’re both alive and relatively unscathed, but now what? How do you get out form this place? Where even is this place? And how do you go home? It becomes increasingly obvious that you don’t have much resources and that you need some sort of plan if you want to survive.

"What about Sophia and the pilots? Do you know what happened to them?" you suddenly remember the rest of the crew. Perhaps they know more about how to proceed in such a situation. They might even know where you’re located, how far you are from home and what’s the procedure to ensure everyone’s survival and rescue.

"I dunno, love. Didn’t see them when we were in the water, I think they might have been on the other side of the plane," the somber look on his face betrays his pessimism as to their fate. They would be on the beach as well if they had survived. As the same reasoning courses through your mind, you look down in sadness at the vicious image of them struggling in the water before succumbing to the fatigue. Harry notices your pained expression and brings you back against his frame to leave a small comforting kiss at your hairline.

"Alright, it’s gonna be fine," you declare in pretend confidence. "People will start looking for us, right?" you try to make light of the conversation. "Hell, there’s probably going to be a whole unit created to find you as soon as we don’t show up in London and I’m sure they’ll find us fast." Hope is emulating in your belly where water had previously drown your vigor. You’re probably right; surely, if the one and only Harry Styles disappears in the middle of a plane crash, the response will be worthy of the man.

He doesn’t seem to quite share the sentiment however, if the small frown and nervous nipping at his lips suggest anything. "Love, I- Jeff’s the only one who knows we were going back to England. He might not notice right away." It’s his own fear talking, the idea that it might take more than a day for people to notice their unsettling absence.

On a normal schedule, him and Jeff would be in constant contact, sharing details for the next day’s agenda, planning tours, interviews, promotions and pitching in ideas for new projects, but be that as it may, Harry was currently on vacation. He’d taken a couple weeks off to relieve the pressure from the last busy months and catch up on some much needed time with you, and Jeff knew that meant a little less consistent contact for this break to be as rejuvenating as expected. Would he think much of the absence of texts from his friend? At some point definitely, but how long would it take for concern to replace dismissal?

Talk about rejuvenation.

"What about the plane company?" you ask, not ready to see your hopes dwindle down.

He seems surprised at the thought for a second before the anxious lines on his face smooth out some, iridescent eyes locking with your own in renewed faith. "You’re right, Jeff was the one who made the booking, so the company will have to contact him once they know about the crash." You let your lips quirk into a soft smile at his optimism before he adds, "we just have to survive until then."

"Right," you dial back on the heart-talking and dares your brain to recall any tips about survival behavior you’ve ever heard. "So we need find water asap and to make a fire before the night falls." You know water should be your priority, you have three days before you die of dehydration, maybe even less under this blazing sun. And despite behind surrounded by water, you know that the sea can’t help you with that. It’s quite ironic in a sense, you find yourself trapped by water, yet the biggest threat to you in that instance is the lack of water consumption. As for the fire, you also know temperature can drop very low at night in places like this and since you don’t have anything to bundle yourselves in, hypothermia is your second biggest threat.

Harry nods in approval before looking around. The beach is enclosed between the sea and endless stretch of luxuriant green tropical jungle. "Come on then, we should try and see if anything from the plane made it out on the beach. I think I saw some pieces earlier, maybe we’ll find something to store water." You think it’s a brilliant idea since you will need some kind of container should you be successful in your quest for water. And with that, you both start walking back towards the edge of the shore, Harry’s hand holding tightly to your shoulder keeping you close to him.

➪ Masterlist

#harry styles one shot#harry styles writing#harry styles imagine#harry styles fic#harry styles fanfic#best friends to lovers#reader insert#creative writing#harry styles fluff#harry styles ou

72 notes

·

View notes

Note

It is impossible to decipher Jon's ending with the show as a guide. They whitewashed T so much, they hid the many aspects of dark D, it is impossible to have any clear idea where and how he ends up. I can believe Jon bending the knee to D bc he wants the dragons and T requires his dominion via Sansa, but the way they showed it? No. T is a villain and by ignoring it they messed with Jon's entire post S6 arc.

It really is. It feels like there are some distinct paths that could be taken to get to specific endpoints, but I don't see how the major beats/endpoints we have all mesh.

I don’t know how Martin can write a story in which the Starks are in power and Jon is sent back to the Watch without making it feel forced and really crappy. In the abstract I can understand “they’ll all make sacrifices for peace blah blah blah,” but when I think about book Jon…no. Even if his end is him self-exiling, I’ll still think it’s a shitty ending.

He has all this king foreshadowing and training on how to be a good leader for what? He’s dead rn, has to suffer through taking down the Targs and defeating the Others, and then he’s just sent away? An author who wants to defy expectations can think of that idea as compelling in theory. The hidden heir/secret prince finds out and instead of it being a good thing, it’s a curse and ruins his life, but thinking about the character, about what Jon’s life has been/will be...it’s soul crushing.

And it’s particularly insulting that Tyrion may not be punished, instead ends up in a position of power when he is a kinslayer too? After he participates in Dany coming to Westeros? When he married Sansa in order to take Winterfell??? It’s mind boggling to me how that’s not an absurd outcome in-world. And, paired with Jon’s (alleged) ending, it feels incongruous instead of in service of following the rules of the world.

I agree that Jon bending the knee to save his people is possible because of the reference to Torrhen, and while I understand that it isn’t nearly as exciting as going to war, yielding rather than fighting, securing peace rather than pursuing vengeance, that’s a sign of a good leader in Martin’s eyes. He’s repeatedly touched on it. That’s even brought up with Bran turning over Winterfell to Theon rather than allowing more people to die which, now that I mention it, I suppose must have been to contrast him with Robb? I just realized there are probably a lot of contrasts between them. 🤔 Anyway, when the show tried creating a “learn from Mance’s mistake” lesson in s7, it seemed totally reasonable to me that bending the knee was from Martin. Obviously doing it for love/wanting Dany to be the ruler is bs, but they continued to act like Jon’s decision was about the safety of the North in s8 so it isn’t hard for me to assume Jon will do it for the right reasons in the book. Actually, the knee bend in the books could even be insincere/a part of his assassination attempt for all we know. 🤷🏻♀️ That’s with the assumption that Jon is KitN and I typically work with that.

I have other asks about Sansa’s marriage to Tyrion, so eventually I’ll talk about that more, and I guess it’s possible that negotiations have to take place to get him to go along with the annulment, but how would he be in such a position to demand something like being hand? We’re really supposed to think he’d have that clout after everything? It isn’t a bad idea (in theory) to have a villain win, but it sounds like a mess of an ending to me.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

what makes namor such a fascinating character? i know his character development gets ignored a lot but what type of growth has he actually had and where should he go next?

What makes Namor such a fascinating character?

I think a lot of people have different things they like about him or reasons why they want to keep reading him, but I feel like Kris Anka really nailed a major reason why a lot of Namor fans love him that he once posted but I can't seem to find now because tumblr is a functioning hellsite 🙃

Anyways generalizing on what he said: "Namor is one of the most painfully honest characters in comics."

Namor doesn't have pretenses, he is isn't an open book but he will not hesitate to let people know where he stands on a matter, he isn't afraid to go against the popular opinion or point out what something is stupid/wrong. He has a set of morals that is very grey.

I think another reason that makes Namor so interesting is how he is in relation to other characters, who by default strive to protect humanity but Namor isn't humanity's savior, he's the Atlantean people's hero, which at times makes the humans his enemies because they are the villains in his story.

Namor has a lot of layers, but sadly too many people accept this weird fandom interpretation of him through Fantastic Four, X-Men, & Avengers comics where Namor is just a jackass/horny ocean guy (Yes, he is a horny ocean guy & a jackass but there is more than just two traits for a character). So they never look past that to see how Namor is actually a very salty sea bastard who's heart is a crusty marshmallow, he does have soft moments but it's usually reserved for times he is with people he likes/trusts. His story is of a character that walks the line between two worlds and fits into neither.

I know his character development gets ignored a lot but what type of growth has he actually had and where should he go next?

This is a bit trickier to answer simply because Namor has been around since literally the beginning of super hero comics, his character's genre has undergone everything from; fantasy, horror, pulp, romance, adventure, super heroics, eco politics, and war comics. He is much more versatile than writers and fans give the character credit for, there is literally so much one can do, and many different directions that one could take.

You want a high fantasy underwater royal court political drama? You can do that. You want a High fantasy that centers on sea monsters, Atlantis, etc.? A undersea horror? A romance between people of two different worlds? A statement about how humanity is killing the oceans? You want to take Namor on a road trip to space with a magic dude, a silver dude, and green giant, yeah that works too. There is so much one CAN do that it boggles the mind that Marvel chooses not to do anything at all.

Namor seems like a very rigid character, he is actually very versatile.

The type of growth one sees with Namor... as I said, it's tricky, but if I wanted to break it down:

Young biracial Prince raised in his mother's world with little connection to the other half of his heritage, goes on a misguided mission of vengeance to seek approval of his emotionally abusive grandfather > befriends and fights alongside people he had been taught his whole life were his enemies because there are worse people out there > Is worn down by his time in war, sees the best and worst of humanity > Is thrust into power at a young age (by Atlantean standards) and is expected to rule, yet now he can't condemn all of humanity because there are people, good people there, however showing weakness among his court always results in disaster > Deals with both sides of his people wanting to kill the other, and tries to navigate for some kind of balance.

You have his character, which was very carefree (as a Prince could be) becoming more hardened and closed off as time goes by yet he is a character that FEELS a lot, and is still very passionate no matter how hard the world grinds down on his soul.

#namor#namor mckenzie#namor the sub mariner#comic talk#imp answers#sorry i just tend to ramble on#someday I will have a coherent post about the fish man I swear?

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

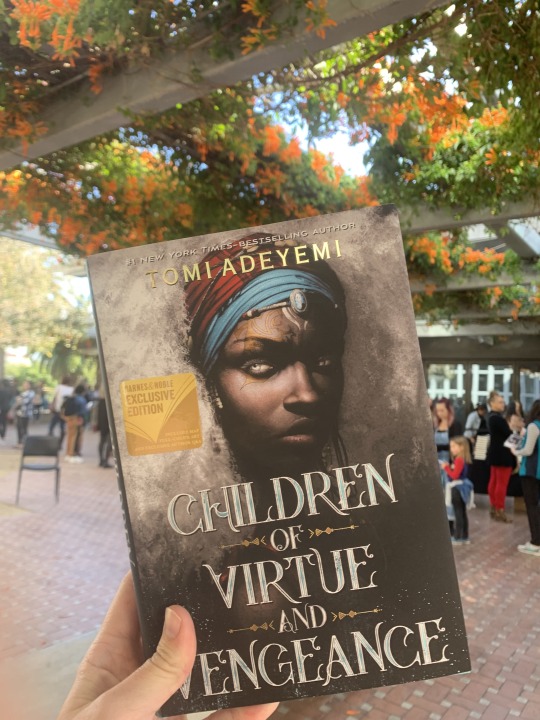

Children of Virtue and Vengeance Book Review

Children of Virtue and Vengeance Book Review by Tomi Adeyemi

I was so incredibly pumped for this book.

Key word: Was.

If you haven’t heard of Tomi Adeyemi you’ve been living under more than just a rock as she’s been dominating The New York Times Bestsellers List since her debut novel, Children of Blood and Bone, was published in 2018.

The sequel to this was released in December of 2019, and I was riding the waves of Tomi’s utter charisma and charm as well as the breathtaking characterization, fantasy, and poignant writing style that the first novel abundantly offered only to be unfortunately let down.

Now, before I get into why I found the sequel so abysmally disappointing, I do want to say that I love Tomi like the nerdy fangirl I truly am. I was fortunate enough to go to her book signing in the middle of December in San Diego, and I was blown away by her.

She was so young! And funny! And talented! And humble! She liked anime and Avatar: The Last Airbender and Harry Potter, and I was smitten. I wanted so badly to be her best friend, and more than that, I wanted to be like her. Successful, intelligent, adored, published.

With all that in mind, the disappointment that I determined Children of Virtue and Vengeance to be was all the more bitter when I remember how inspiring and galvanizing I found Tomi. That being said, I’m still a huge infatuated supporter of Tomi; I’m just now left pondering...what happened?

Maybe I’m the only one who found this book confusing and disenchanting. Maybe everyone else loved it. Maybe I’m being too critical. All of this could be true.

However, I set out to make this blog a candid interpretation of my feelings on the books that I read, exaggeration and hyperbole aside. I wouldn’t be critical of this book if I didn't think it deserved it.

Along the same vein, you don’t have to agree with me. In fact, differing opinions make the world go round, so feel free to shout and snap your laptop closed.

But enough chitter-chatter. Why didn’t I like this book?

It was fucking confusing and shallow. Those are probably my two biggest criticisms.

The first book had so much going for it. All of the main characters were engaging and interesting (cue looking at my previous review of it here), the world building was winsome and detailed, the relationships were fraught with myriad feelings and complications, and everything had depth and stakes and emotions.

I personally felt like all of this was missing from book two. The main character, Zélie, was aggravating and irritating in this installment, Amari was ignorant and weak, Tzain was inconsequential, and Inan was disillusioned and whiny.

Everything that I had loved about these characters from book one seemed to have been replaced with these other characteristics that frankly made reading this book a chore. I truly didn’t like any of them.

It’s like getting to the fourth season of a show you previously loved and realizing that they’re doing everything wrong now because they’ve run out of ideas for the episodes. All the characters read as worse replicas of their previous personas, and that made getting through the book really challenging.

In addition, I felt despairingly lost about 90% of the time. I’ve made this critique before of other novels, but I'll say it again: It’s okay to make your readers interpret what’s going on in your novel and not spell everything out for them like they’re first-graders. It’s welcome to have to squirm a little. It’s deliciously challenging when there’s a learning curve in the beginning.

It’s infuriating when that learning “curve” is still happening ¾’s through the book.

The plot was as organized as the grocery store check-out line when Covid first

Started. That being-not at all. Tomi seemed to be making shit up left and right. Oh, Zélie can fly using her power? Why not! Oh, there is actually this whole underground sanctuary that an entire army can't seem to find? Believable. Oh, now there are people called cênters and light is pouring from Zélie’s mouth and eyes and that’s not concerning-why would it be? And oh! Let’s just bring people back from the dead! Hahahah!

It was exasperating.

Tomi just seemed to pull things out of thin air when the situation called for it, and that doesn’t make for a pleasurable reading experience-it makes for a diluted one. Also, just like my criticism in the Chain of Gold Review, Tomi throws so many new characters at you and expects you to care about what happens to them.

Why the hell would I care about a character you literally just introduced me to five seconds ago and that I know nothing about other than he has big ears? Who gives a shit.

When said character dies, I didn’t shed a single tear. That segment was well written, don’t get me wrong, but it lacked emotion and depth because I had met him fifty pages ago.

And you know why I didn’t put this character’s name? Because I don’t even remember it and I finished the book yesterday. That’s a problem. That’s a really big problem.

In the end, this book was too much and not enough simultaneously. I almost feel like Tomi had all the right ideas and a large starry plan for what was going to happen, but for some reason the writing was expedited and rushed and that made the book lackluster and dull overall. The lack of description for the things that mattered made me disconnected from the characters and more irritated with their behavior than empathetic.

The plot, while exciting, was riddled with so many holes and boggling epiphanies that it lacked consistency, logic, and structure.

Now, like any good YA book sequel, this one ended on a cliff-hanger. As is customary for this novel in particular, the cliff-hanger was more perplexing than it was anticipatory.

Instead of making me wonder Omg, what’s gonna happen next? It made me think what the fuck just happend and is it over now?

After this novel I truly am on the fence about getting the next one. Part of me wants to see this through for Tomi and all the time I’ve already put into it, but another part of me wants to pitch myself off a balcony at the thought of reading about Zélie and Amari again.

Only time will tell, my friends.

Recommendation: Hit up Tomi. That girl is a gift sent from the gods. I love her. I love her stanning of BTS and the fact that we share a hometown and that she’s truly making a strike on the YA world with her inclusion of diverse characters and African mythology and fostering discussions on race and representation. That being said, this novel was a dud. Read the first one and then watch all the interviews of Tomi you can find and save yourself the disappointment.

Score: 4/10

Here are some bonus pics of Tomi and then Tomi, her friend wearing antlers, and me!!!!

#children of virtue and vengeance#CHILDREN OF BLOOD AND BONE#tomi adeyemi#african mythology#fantasy#book blog#books#book review#book signing#Book Recommendations#ya fiction#YA literature#YA Books#zélie#amari#inan

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sansa being praised as a good victim and Sansa fans putting down other abuse victims part 2 (because people keep telling me this doesn’t happen)

Companion to this post.

http://secretlyatargaryen.tumblr.com/post/162004630567/im-so-glad-im-not-the-only-one-who-doesnt-like

i'm so glad i'm not the only one who doesn't like lyanna. tho tbh i hate rhaegar 1000x more. and i absolutely despise how much they're romanticized in the fandom. i still don't understand how 11yo sansa gets so much hate for her dreams and mistakes in the beginning, but not the older, "wiser" lyanna for supposedly running off with a MARRIED southern prince. i mean neither should entirely be at fault bc they were both young girls who imo were taken advantage of, but it's some food for thought.

For now I am not a Lyanna fan at all. I try to sympathize with her and I can’t. I try to find similarities between her and Sansa and forgive her actions but again I can’t. We don’t know a lot about Lyanna so maybe I will change my mind in the future but for now just the thought of her leaves a bad taste in my mouth.

What I don’t understand is how Lyanna gets almost no blame for what happened to her family even though a 11 year old Sansa gets blamed for her father’s death.

http://secretlyatargaryen.tumblr.com/post/70714078551/i-am-loyal-to-king-joffrey-my-one-true-love

Okay, but this is bullshit because Tyrion’s big mouth is always getting him into trouble. He can never shut his sass up. Thus and therefore, Sansa is approximately 1,568% better than ur fave….especially if it’s Tyrion. Ugh.

http://secretlyatargaryen.tumblr.com/post/53455177515/exitpursuedbyasloth-you-should-learn-to-ignore

“You should learn to ignore them.” -Sansa Stark, First of Her Name, the Queen of Survival, the Unbroken, More Alive Than All Your Faves, Protector of Lemoncakes, Patron Saint of Songs and Broken Men

Hey Tyrion, you might want to fucking listen to Sansa right now. Tyrion? Tyrion, are you listening to Sansa? Oh, no, you’re threatening Joffrey’s life right in front of his mother, Tywin, and Varys. Oh, wow, that’s going to end really well for you you are a clever one aren’t you I am sure there will be no unwanted repercussions from that no sir.

https://www.facebook.com/EverythingGameOfThrones/posts/610986598973846

Would you rather she behave like Cersei, or perhaps Margaery? But she is learning fast and is stronger than she appears. Would you be strong enough to keep a straight face when the enemy comes to tell you they slaughtered you mother and brother? Or to keep your mouth shut, not uttering a curse or threat as Joffrey is having you beat bloody? Or to treat him with kindness and respect after he threatens to rape you?

http://www.snarksquad.com/2014/04/game-of-thrones-s04-e03-this-fucking-episode.html

I do not think Arya would have lasted as long as Sansa, had she been caught before fleeing King's Landing. I think Arya would have had a hard time keeping her mouth shut and "behaving wisely" and I think she might've got herself killed or tortured by Joffrey.

https://www.accesshollywood.com/articles/game-of-thrones-qa-sophie-turner-on-sansas-escape-146456/

I think Sansa is one of the strongest people because the thing about this world that people don’t realize is that, yeah, there are these cool fighting badasses like Brienne and Arya, but the real easiest way to survive is to keep your mouth shut and do what people want you to do and Sansa’s like clicked on to this and that’s why she’s gone on for so long. People aren’t scared of her, people don’t suspect her. I think it’s a very brave and very intelligent thing to do.

And if you think about it, Arya, if she had stayed in King’s Landing, she might not be alive, because she wouldn’t have been able to keep her mouth shut.

So Sansa is really the best person to be in that situation if you had to have one of the Starks there.

http://www.xojane.com/entertainment/sansa-stark-feminist-superhero?page=232

Because, while Sansa still initially falls into the problematic “traumatized woman” trope, she ends up breaking it by handling her trauma in a way that most characters like her do not. She doesn’t become a hardened warrior, or hide behind fire-tongued abrasiveness. How many female characters do we know that hide behind spunk, brashness, and typically “male” behaviors to cope with their feelings of hurt or abandonment?

http://artnalism.com/game-thrones-sansa-stark-apology/

Consider this though: Arya’s tendency to action and violence would have had her killed in King’s Landing. Sansa stayed alive because she knew there was no way to escape without help – and she’s not given enough (or any) credit for that. Sansa’s strength comes from her ability to survive.

http://asoiaf.westeros.org/index.php?/topic/124198-why-do-people-hate-the-kick-ass-character-that-is-arya-stark/

I’m not gonna root for [Arya] doing that while she is destroying her soul in the process

http://jaimebrienne.com/topic/30003647/88/

If any of the Starks are going to live, I think it probably will be Sansa. Unlike Arya who's main focus is revenge, she just does what it takes to survive.

http://asoiaf.westeros.org/index.php?/topic/126817-about-sansa-and-arya/

HOWEVER, I believe that Sansa's fate could be more tragic than any of those listed above. Sansa could die, and it may be because of Arya.

[...]

This would mirror innocent Lady being sacrificed in absence of the real culprit Nymeria.

https://www.quora.com/Would-Sansa-make-a-better-queen-than-Daenerys

Dany's arc is one in which a princess who's been brought low gradually rises higher, whereas Sansa's arc is one in which a privileged lady is brought low and must be resilient and creative in order to rise higher and rebuild herself. At this stage of the story, Dany has so much and yet also struggles so much that you might wonder just how much a person could need to finally move. If three dragons, a bunch of sellsword companies and the Unsullied aren't guarantors of stability, what is? If Dany can't figure her stuff out with all of that, then how talented is she? Whereas Sansa has been a prisoner since her father's death and has had to navigate a situation where she's not empowered at all, and while she hasn't completely climbed her way out yet, there are clear signs that she's poised to do so. In terms of direction and overall vision and sense of purpose, Dany has stumbled while having mind-boggling resources, and Sansa has succeeded despite having nothing but her own damn self.

[...]

Sansa is gentle and merciful, wanting everything to be music and lemon cakes like in the stories. Even when she's been wronged, she just wants people to be good to each other, rather than wanting revenge.

Dany has (justifiably or not) burned and crucified people, breaking contracts and seeking vengeance on people who wronged her. She has entered conflicts with no exit strategy, and she's very prideful.

[...]

Sansa would understand and forgive, and not cast them aside for one mistake that this person has already been trying to rectify ever since they realised they were wrong. And last but not least, Daenerys is actually quite evil

http://www.escapistmagazine.com/forums/read/18.855926-Game-of-Thrones-Sansa-vs-Daenerys

Daenerys on the other hand almost out the gate is a strong aggressive woman who knows what she wants and is eager to take it. However, this is actually not a point in Daenerys's favor. Sansa has room to develop and change. She can start out as a "stupid little girl" whose head is full of silly ideals such as chivalry and honor, and then she can become a badass political schemer who still holds a bit of a softer side. Where as Daenery's becomes the "mother of dragons" by the end of book one and is so full of piss and vinegar that some people suspect that the only place she can go is crazy town.

[...]

What does Daenerys lose? Kahl Drogo? Really? Khal Drogo was a barbarian warlord who used her as an arian f@#$ puppet. Sure they eventually obtain a more mutual relationship because she can do it cowgirl style, but she doesn't even speak his language for most of the time spent with him. Furthermore, by book 5 she seems totally over him. She is all over her sellsword boyfriend and is even getting freaky with some of her serving girls. Meanwhile, Sansa is being creeped on by a guy who was in love with her mother. Things go far too well for Daenerys.

[...]

Dany on the other hand, despite coming from similar circumstances, is everything wrong with an idealistic person and she only learns lessons and changes when it conveniences her. She's Joffrey's antipode in almost every way, but she's just as bad because she's as flawed as he is.

She isn't even a nice person in person because she's haughty and arrogant and mindful of her rank and her position on top.

https://winterfelland.tumblr.com/post/159370019542/the-pro-daenerys-and-pro-sansa-meta-no-one-asked

if you ever want to write something again with the delusion of not pissing off Sansa fans… don’t you EVER dare write down the fantasy of Daenerys Stockholm syndrome Targaryen who started randomly enjoying being raped every night giving sex advice to ‘poor Sansa (who) has not had a positive sexual experience yet.’

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by theory,

well-fed complacent leather-coated, dragging themselves through the

Caucasian campuses at dawn looking for an angry signifier.

The voices dissolved into the warm pre-dawn darkness as I watched vomit drip between the ferns and fallen leaves. Muttering consolations, my friend held my elbow. Only moments before we had been making impassioned if sloshy love in my single bed, while my 21st birthday party raged outside. Now I was hurling what seemed like a infinite fount of bile into the bushes behind my little room.

As my friend led me to bed, I thought: You really are 21 now. You got horribly drunk, dragged a guy to bed, and then got sick. Just like a made-for-TV movie. These thoughts were accompanied by an odd, abstracted rapture I have come to take for granted. For want of a better term, I'll call it the rapture of irony.

Halfway to my bed, I must have laughed out loud, because my friend asked, "What are you thinking about?"

"The narrative," was all I could manage. I wanted him to know that even in this humiliated, impaired state, I was fully cognizant of the mind boggling paradox of the situation. I may have been a walking cliché but at least I was self-conscious.

Carol Lloyd, I Was Michel Foucault’s Love Slave

As I drifted off into a tangle of dehydrated nightmares, I comforted myself with the thought that Theory had suffused my life so thoroughly that I couldn't get laid, get drunk and get sick without paying homage to Roland Barthes' notion of the "artifice of realism" or Baudrillard's "simulacra." Though now I live a practical life, with more actions and fewer theories, I still struggle with the convoluted mind-set of my higher education. Even after years of trying to acclimate myself to a more concrete world, this odd theology lives in me so much so that it is only recently that I have recognized it for what it is: a religious doctrine.

I am a child of Theory. I avoided this truth because I didn't want to confront the deep, strange river of pretentiousness that courses in my veins. But lately I've begun to think my predicament is less reflective of a private eccentricity than of a weird historical moment. The moment when the most arcane, elitist mental gymnastics Theory in all its hybrid forms was reborn as sexy, politically radical action. The moment when well-meaning liberal intellectuals who a decade before had dedicated themselves to activism, volunteerism and building social programs turned inward, tending to their private experiential gardens with obsessive diligence. Theory offered intellectuals the same escape from the public world that self-help and therapy offered the masses. But unlike self-help and therapy, which never claimed to be anything but psycho-spiritual Darwinism, Theory draped itself in revolutionary verbiage and pretended to be a political movement.

For those of us who got liberal educations in the wake of this shift, being radical meant little more than voting when it was convenient, reading the newspaper and thinking about doing charity work. The only thing that separated us from the ignorant masses was our intellectual opinions, which we shrouded in baroque revolutionary rhetoric. The "tyranny of grammar," the "subversion of sexual mores in extinct Native American tribes," and the "colonialism of the novel" these were our mantles of honor.

Though I always believed that my upbringing was free of ideological trappings, I now see that the seed was planted long before I reached college. My eldest brother was a political activist in his teens, but with the onslaught of the '80s he threw away his ideals and pursued the good life: drinking from the corporate tit as an organizational consultant. After two years in Africa as Peace Corps volunteers, my parents shed their activist habits, moving to a resort town with the intention of getting rich building houses for retired millionaires. Aside from the little holes punched in their secret ballots and token checks made out to various nonprofit organizations, politically my family acted no differently than our blue-blood, conservative neighbors. They pursued the free market with a vengeance, bought as many nice things as possible and hobnobbed at the tennis club. But they still talked like the lefties they once had been. And how they talked.

At dinner we served up steaming topical cauldrons of death, child rearing, art and gender, then skewered them whole. We asked unanswerable questions and then imperiously proceeded to invent the answers. We had no interest in facts. Facts were just things you made up to win arguments. Once I brought home a boyfriend whose old-fashioned education and conservative family had taught him none of the liberal preference for ideas over facts. When the dinner conversation turned toward his hobby of California history and he began to speak in facts, my family paused to stare at him like he was sporting antennae. My mother hemmed; my father hawed; my brothers began to babble invented statistics. Through my family I learned to love ideas "for their own sake," which made me a kind of idiot savant (with emphasis on the idiot) and a prime victim for the God of Theory.

In 1978 my high school history teacher, a Harvard-educated, Jewish-turned-Catholic New Yorker, promised to give "extra credit" to anyone who read and did a book report on Paul de Man's "Blindness and Insight." (Though later exposed as a Nazi sympathizer, at that moment de Man still carried the mantle of "subversive" in the hippest sense.) Dutifully, I read every page understanding it the way a little boy understands the gurgles of his toad. I had no idea what it meant but the densely knotted language of ideas made my head implode and my body sing. For the rest of my high school years I would only have to read a paragraph or two of deconstruction's steamy prose to have a literary orgasm.

In his recent disavowal of literary criticism in Lingua Franca, Frank Lentricchia confesses that his "silent encounters with literature are ravishingly pleasurable, like erotic transport." My experiences with Theory were equally exalted delivering me into a paroxysm of overdetermined signs. In the blurry vertigo of those pages so full of incomprehensible printed matter I felt myself in the presence of a God: the God of complex questions, the God of language's mysteries, the God of meaning severed from the painful and demanding particularity of experience. In abstractions, I found absolution from a world in which I was utterly unprepared for any real responsibility or sacrifice. By surrendering myself to Theory, "reality" became a blank screen upon which I projected my political fantasies. My feelings of responsibility to a world that I had once recognized as both unjust and astoundingly concrete, slowly and painlessly seeped out of me until all that remained was the "consciousness" of the "complexity" of any "serious issue." I didn't need to fix anything, utterance was all, and all I needed were the words long and tentacled enough to entrap meaning for a slippery, textual moment.

Like any religion, Theory provided perks to the pious. In my freshman year, I took an upper-division class on the 17th century English novel. The books were long and difficult but I secured my standing in the class when I responded to the teacher's mention of deconstructive theory. "Yes, each idea undermines itself," I parroted, channeling the memory of my sophomore extra credit report. "Paul de Man says..." With that bit of arcane spittle, I hit pay dirt. The teacher gave me such a hyperbolic recommendation, I was able to transfer to a better school. Once there, I evaded undergraduate classes with their demanding finals and multiple writing assignments and insinuated myself into graduate theory seminars of all departments: anthropology, literature, political science, theater, history. With a host of other would-be intellectuals, I honed the fine art of thinking about thinking about ... What we were thinking about was always pretty irrelevant. I developed minor expertise in the representation of the hermaphrodite in psychiatric literature, the uncanny relationship between classical ballet and the absolutist state of Louis XIV and the woman as landscape in Robbe-Grillet's "Jealousy." Now I was just warming up, I told myself. Someday I would find an important issue worthy of all my well-exercised mental muscles and then watch out hegemony!

While I was being treated to the many joys of a great liberal education, I was also learning some rather insidious lessons. I discovered I didn't have to read the entire assigned book. After all, the "ideas" were what was important. Better to read the criticism about the book. Better yet, read the criticism of the criticism and my teachers would not only be impressed but a little intimidated. By extension, I learned not only a way of reading but a way of living. The more removed I was from a primary act, the more valuable it was. Why scoop soup at the homeless shelter when you could say something interesting about how naive it was to think that feeding people really helped them when really what was needed was structural change.

My friends now fall into two categories: ex-Theory nerds (like me) making a living off their late-learned pragmatism, and those who still live and breathe by Theory's fragrant vapors political theorists, literary critics, historians, eternal graduate students. I love talking to them and often I covet the little thrones their ideas get to perch on. Yet when I come away from a conversation that has swooped from the racist implications of early French embalming techniques to the "revolutionary interventions" in the margins of "Tristram Shandy" and ended with the appalling hypocrisy of the right wing, I often feel a strange discomfort. Because these are some of the smartest, kindest and most energetic people I know, I cannot resist the question: Is this the best way for them to spend their lives? If they acknowledged that they were largely engaged in the amoral endeavor of pure intellectual play, that would be one thing, but each of these people considers their work deeply, emphatically political.

Is this theory-heavy, fact-free education teaching people to preach one way and live another? Are we learning that political opinion, however finely crafted, is a legitimate substitute for action? Sometimes it seems that the increased political emphasis on language the controversies over "chairpersons," "people of color" and "youth-at-risk" did more than create a friendly linguistic landscape, it gave liberals something to do, to argue about, to write about, while the right wing took over the country, precinct by precinct. After all, in a world where each lousy word can stir up a raging debate, why worry about the hard, dull work of food distribution or waste management?

I know how high and mighty this sounds, and the side of me that appreciates subtlety and disdains brow-beating is wincing. Political moralism has fallen from fashion, leaving us to cobble together myopic philosophies from warmed-over New Age thinkers like Deepak Chopra or archaic scriptures like the Bible. If it's any consolation, I include myself in the most offending group of educated progressives who squandered their political power over white wine and words like "instantiation." Moreover, I'm not saying we're all a bunch of awful, selfish people. We learned to read, we learned to think critically and at least pay lip service to certain values of justice, egalitarianism and questioning authority. But I do wonder if we're handicapped, publicly impaired somehow.

Like most of my siblings of Theory, from time to time I have tried to get off my duff and do something concrete: protest, precinct walk, do volunteer work whatever but I always get impatient. I wasn't meant to chant annoying rhymes. I am trained to relish complexity, to never simplify a thought. I am trained to appreciate "difference" (between skin tones and truths), but I don't know how to organize a political meeting, create a strategy or make a long-term commitment to a social organization. As Wallace Shawn wrote in "The Fever," "The incredible history of my feelings and my thoughts could fill up a dozen leather-bound books. But the story of my life my behavior, my actions that's a slim volume and I've never read it."

Lentricchia argues that by politicizing the experience of reading, we ended up degrading its beauty and pleasure. In the same fell swoop, we also robbed concrete political action of its meaning. The progressive pragmatists studied political theory; the progressive idealists studied literary theory; and the eccentric radicals became conceptual artists and sold their work to millionaires. In any case, everyone bought the idea that they were engaged in political work. Having a radical opinion was tantamount to revolution.

Back in college, I remember going to a party at the home of one of my professors, who was a famous Marxist. The split-level house was decorated with rare antiques from all over the world, exclusive labels filled the wine cellar, the banquet table overflowed with delicacies. Like an anointed inner circle of acolytes, we students sat around as our professors argued that Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait was justified from the perspective of the underpaid Palestinian servants who worked in Kuwaiti homes. The following month, while I was house-sitting at the professor's house, his black gardener came to the door wanting to be paid. I discovered that my professor was paying the man minimum wage for less than a half day of self-employed work. That night as I plundered the refrigerator for the best cheeses that money could buy, I chided myself for not having doubled the man's wages. But that might have embarrassed him, no? It definitely would have embarrassed me. It would have been acting on a belief, and action makes me uncomfortable.

Recently I went to a conference on "Women's Art and Activism." I found precious little of either. Instead I found a lot of Theory garbed in its many costumes. There was a lesbian conceptual artist talking about her work, triangular boxes that "undermined the patriarchy of shapes"; a "revolutionary" poet lecturing on her experience of biculturalism; and an "anarchist" performance artist discussing "strategies for subversion." And what fabulous haircuts! The keynote speaker was Orlon, a French performance artist whose work consists of having her entire face rebuilt by plastic surgery. After a very French explanation as to why she needed a third face lift, she answered questions from the packed house. "I think you're just incredible," said one woman. "You say your aim is to reconquer your body as signifier. How do you feel about letting a doctor touch your signifier? And how do you see your revolutionary techniques emancipating women from the prisons of their bodies as sign?"

Had I stumbled into a satanic ritual, I couldn't have felt a more chilling sensation of alienation. Once I would have smiled at these liturgies and savored their impenetrable truths. Now I only wanted to run away and do what? Dig a ditch? Perform open heart surgery? Administrate a charity? Even after all these years, I was still expecting Theory to visit me like the Virgin Mary and give me more than a sign.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

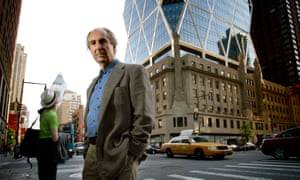

'Savagely funny and bitingly honest' – 14 writers on their favourite Philip Roth novels

New Post has been published on https://funnythingshere.xyz/savagely-funny-and-bitingly-honest-14-writers-on-their-favourite-philip-roth-novels/

'Savagely funny and bitingly honest' – 14 writers on their favourite Philip Roth novels

Emma Brockes on Goodbye, Columbus (1959)

I fell in love with Neil Klugman, forerunner to Portnoy and hero of Goodbye, Columbus, Philip Roth’s first novel, in my early 20s – 40 years after the novel was written. Descriptions of Roth’s writing often err towards violence; he is savagely funny, bitingly honest, filled with rage and thwarted desire. But although his first novel rehearses all the themes he would spend 60 years mining – sexual vanity, lower-middle-class consciousness (“for an instant Brenda reminded me of the pug-nosed little bastards from Montclair”), the crushing weight of family and, of course, American Jewish identity – what I loved about his first novel was its tenderness.

Goodbye, Columbus is steeped in the nostalgia only available to a 26-year-old man writing of himself in his earlier 20s, a greater psychological leap perhaps than between decades as they pass in later life. Neil is smart, inadequate, needy, competitive. He longs for Brenda and fears her rejection, tempering his desire with pre-emptive attack. All the things one recognises and does.

My mother told me that the first time she read Portnoy’s Complaint she wept and, at the time, I couldn’t understand why. It’s not a sad novel. But, of course, as I got older I understood. One cries not because it is sad but because it is true, and no matter how funny he is, reading Roth always leaves one a little devastated.

I picked up Goodbye, Columbus this morning and went back to Aunt Gladys, one of the most put-upon women in fiction, who didn’t serve pepper in her household because she had heard it was not absorbed by the body, and – the perfect Rothian line, wry, affectionate, with a nod to the infinite – “it was disturbing to Aunt Gladys to think that anything she served might pass through a gullet, stomach and bowel just for the pleasure of the trip”. How we’ll miss him.

Emma Brockes is a novelist and Guardian columnist

James Schamus on Goodbye, Columbus (1959)

Philip Roth was more than capable of the kind of formal patterning and closure that preoccupied the work of Henry James, with whom he now stands shoulder-to-shoulder in the American literary firmament. So yes, one can always choose a singular favourite – mine is the early story Goodbye, Columbus, though I know the capacious greatness of American Pastoral probably warrants favourite status. But celebrating a single Roth piece poses its own challenges, in that his life’s work was a kind of never-ending battle against the idea that the great work of fiction was anything but, well, work – work as action, creation; work not as noun but as verb; work as glorious as the glove-making so lovingly described in Pastoral, and as ludicrous as the fevered toil of imagination that subtends the masturbatory repetitions of Portnoy’s Complaint. Factual human beings are fiction workers – it’s the only way they can make actual sense of themselves and the people around them, by, as Roth put it in Pastoral, always “getting them wrong” – and Roth was to be among the most dedicated of all wrong-getters, his life’s work thus paradoxically a fight against the formal closure that gave shape to the many masterpieces he wrote. Hence the spillage of self, of characters real and imagined, of characters really imagining and of selves fictionally enacting, from work to work to work. So, here, Philip Roth, is to a job well done.

James Schamus is a film-maker who directed an adaptation of Indignation in 2016

I read it when I was about 18 – an off-piste literary choice in my sobersided studenty world. I had been earnestly dealing with the Cambridge English Faculty reading list and picked up Portnoy having frowned my way through George Eliot’s Romola. The bravura monologue of Alex Portnoy wasn’t just the most outrageously, continuously funny thing I had ever read; it was the nearest thing a novel has come to making me feel very drunk.

And this world-famously Jewish book spoke intensely to my timid home counties Wasp inexperience because, with magnificent candour, it crashed into the one and only subject – which Casanova, talking about sex, called the “subject of subjects” – jerking off. The description of everyone in the audience, young and old, wanking at a burlesque show, including an old man masturbating into his hat (“Ven der putz shteht! Ven der putz shteht! Into the hat that he wears on his head!”) was just mind-boggling. A vision of hell that was also insanely funny. Then there is his agonised epiphany at understanding the word longing in his thwarted desire for a blonde “shikse”. (Was I, a Wasp reader, entitled to admit I shared that stricken swoon of yearning? Only it was a Jewish girl I was in love with.) Portnoy’s Complaint had me in a cross between a chokehold and a tender embrace: this is what a great book does.

Peter Bradshaw is the Guardian’s film critic

William Boyd on Zuckerman Unbound (1981)

Looking back at Philip Roth’s long bibliography, I realise I’m a true fan of early- and middle-Roth. I read everything that appeared from Goodbye, Columbus (I was led to Roth by the excellent film) but then kind of fell by the wayside in the mid 1980s with The Counterlife. As with Anthony Burgess and John Updike, Roth’s astonishing prolixity exhausted even his most loyal readers.

But I always loved the Zuckerman novels, in which “Nathan Zuckerman” leads a parallel existence to that of his creator. Zuckerman Unbound (1981) is the second in the sequence, following The Ghost Writer, and provides a terrifying analysis of what it must have been like for Roth to deal with the overwhelming fame and hysterical contumely that Portnoy’s Complaint provoked, as well as looking at the famous Quiz Show scandals of the 1950s. Zuckerman’s “obscene” novel is called Carnovsky, but the disguise is flimsy. Zuckerman is Roth by any other name, despite the author’s regular denials and prevarications.

Maybe, in the end, the Zuckerman novels are novels for writers, or for readers who dream of being writers. They are very funny and very true and they join a rich genre of writers’ alter ego novels. Anthony Burgess’s Enderby, Updike’s Bech, Fernando Pessoa’s Bernardo Soares, Ernest Hemingway’s Nick Adams, Edward St Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose and so on – the list is surprisingly long. One of the secret joys of writing fictionally is writing about yourself through the lens of fiction. Not every writer does it, but I bet you every writer yearns to. And Roth did it, possibly more thoroughly than anyone else – hence the enduring allure of the Zuckerman novels. Is this what Roth really felt and did – or is it a fiction? Zuckerman remains endlessly tantalising.

William Boyd is a novelist and screenwriter

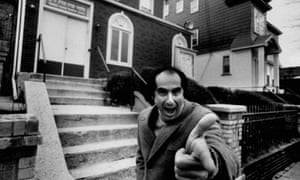

Roth outside the Hebrew school he probably attended as a boy. Photograph: Bob Peterson/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

David Baddiel on Sabbath’s Theater (1995)

Philip Roth is not my favourite writer; that would be John Updike. However, sometimes, on the back of Updike’s – and many other literary giants – books, one reads the word “funny”. In fact, often the words “hilarious”, “rip-roaring”, “hysterical”. This is never true. The only writer in the entire canon of very, very high literature – I’m talking should’ve-got-the-Nobel-prize high – who is properly funny, laugh-out-loud funny, Peep Show funny, is Philip Roth.