#is it primarily an aesthetic thing? is it a *danger is sexy* thing?

Text

Can somebody please explain to me what the appeal of vampires is.

#I'm genuinely curious#people seem to go absolutely feral over this concept and I want to KNOW I want to UNDERSTAND#and there are some really excellent vampire aus that I love and I want to love them MORE because I want to GET IT™#because all I see are like...societally conventionally attractive people with fangs. who maybe (depending on The Lore™)#can't go out in the sun. and that just...doesn't resonate with me?#like I understand metaphors for 'othering' and the concept of monstrosity but I feel like that gets a little lost if there isn't anything#actually UNPALATABLE about them. like if they just look like what we culturally have idealized in human appearance then how can#they serve as a metaphor for ostracization or being misunderstood?#is it primarily an aesthetic thing? is it a *danger is sexy* thing?#but ordinary humans can be plenty dangerous too (see: 90% of the female characters I'm obsessed with)#so is it in the sense of you can vicariously experience that danger and heightened emotion in a situation that's removed from reality#so it feels less overwhelming when you're watching/reading the piece of fiction???#like I have seen this used effectively as a metaphor for marginalization (undead murder farce) and an exploration of how society#defines a 'monster' (shiki) but that doesn't seem to be the way most people or works engage with this concept#is it just that people like when characters are covered in blood because I DO understand that one lmao#I just feel like vampires have been branded as a Key Aspect of Bisexual/Gay Culture and I feel like I am on a separate plane of existence#because It Is Not Clicking For Me#(tbh I feel like there are a lot of Quintessential Queer Experiences™ that don't apply to me but. that's a whole separate thing.)#ANYWAY would love to hear people's thoughts!#I am cooking up a Meta Post™ about fandom reaction to the concept of monstrosity and I want to gather as much information as possible

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Telling Lies In America 1985-1995: The Joe Eszterhas Era by Jessica Kiang

“Written by Joe Eszterhas” is a phrase that has not had much of a workout on US cinema screens in over twenty years—and it’s arguable whether the 1997, 19-screen nationwide release of certifiable shitshow Burn Hollywood Burn: An Alan Smithee Film exactly qualifies as “a workout.” But for those of us who had the parental training wheels come off our theatrical filmgoing in the late ‘80s or early ‘90s, there were few individuals more central to our cinematic coming-of-age. And with perhaps the sole exception of Shane Black, a different animal in any case, none of the others—the Spielbergs, Camerons, Tarantinos—were exclusively screenwriters. For over a decade, the Hungarian-born, Hollywood-minted superstar writer of Basic Instinct bestrode the adult-oriented commercial screenwriting mainstream like a smirking colossus in a tight dress wearing no underwear. And given that Hollywood is primarily how the USA, the most loudly, proudly self-created of nations, expresses itself to itself and to the rest of the world, by the man’s own bombastic standards it’s only a slight exaggeration to suggest that America, between the years of 1985 and 1995, was written by Joe Eszterhas.

But for all the dominance he exerted, the rules he rewrote and the sheer money he made, examining Eszterhas’ heyday today feels like an act of paleontology, even for those of us who lived through it. 1992 is not so very distant; in a variety of ways it is still with us. It was the year Quentin Tarantino, whose latest film is in theaters right now, broke out with his first, Reservoir Dogs. It was the year the current loathsome, racist, tinpot President of the United States made a cameo appearance in Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, back when he was merely a loathsome, racist, tinpot property tycoon. It was the year that the number one box office spot was taken by Disney’s animated Aladdin, which felt close enough in time that the live-action remake which—and I’ve checked my notes on this, apparently was a thing that happened to us in 2019—felt entirely too soon.

But it was also the year of Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct, the sine qua non of Eszterhas-penned films. And if Sharon Stone’s lascivious leg-cross (Verhoeven’s invention, incidentally, not Eszterhas’) provided posterity with the most iconic upskirt of a blonde in a white dress since Marilyn Monroe’s encounter with a subway grate, that is largely all that remains to us of it today. Well, that and the instantly forgotten sequel (sans Eszterhasian involvement) that already seemed wildly anachronistic in 2006. The original film, its writer, the erotic thriller genre it exemplified, the dunderheaded sexual politics it upheld while attempting to subvert, the whole idea of a mainstream screenwriter having a brand at all (even one as loosely defined as “writer of films you don’t tell your parents you snuck into”), all seem like ancient relics. These are the artifacts not only of a bygone age but of an extinct genus, a whole evolutionary branch that was nipped in the bud so comprehensively that even now scientists might argue over how closely the skeletons of certain bird species resemble the bones of Basic Instinct.

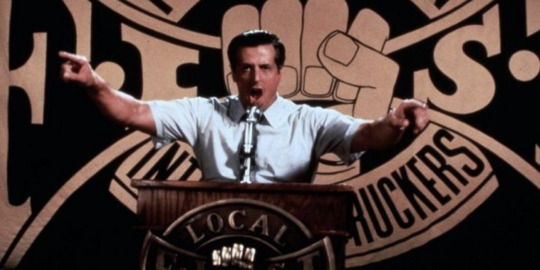

This containment, however, is what makes looking back at the Eszterhas era so fascinating. His brief Hollywood hegemony is a microcosmic event in cinematic history, one with a beginning, middle, and an end (barring some late-breaking epilogue, or a post fade-to-black pan down to an ice pick under the bed). And it didn’t start with his first produced screenplay, for the leaden Sylvester Stallone truckers-union drama F.I.S.T. (Norman Jewison, 1978), although the glimmer of future feats of financial alchemy was already present in the reported $400,000 he received for the novelization. Dawn really broke for Eszterhas, as it did for three of the only other people who could legitimately be termed his peers as purveyors of massively popular, high-concept, low-brow ‘80s sensationalism (producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, director Adrian Lyne), with 1983’s Flashdance.

It was an improbable success, less a film than an aerobics video occasionally interrupted by some awkward sassy banter and Jennifer Beals’ popping-flashbulb smile. Its vanishingly thin story, which Eszterhas co-wrote, is of an 18-year-old welder in a steel mill, who moonlights as an exotic dancer while aspiring to become a ballerina—a logline that sounds like a hoot of derision even as an unadorned description—and is full of Eszterhasian hallmarks. There’s the high degree of preposterousness. There’s the gym scene, during which the ladies of the cast grimace and lift weights in full makeup, and while here the frictionless unreality of Lyne’s TV-commerical aesthetic makes the sequence abstract, the peculiar faith in the erotic potential of a workout would recur in the squash sequence in Jagged Edge (Richard Marqund, 1985) and the ludicrous gym date in Sliver (Phillip Noyce, 1993).

And Flashdance also prefigures almost the entire Eszterhas oeuvre in being a story that centers on a woman’s experience and that laudably—if here laughably—positions her career ambitions as at least equal to her romantic aspirations in the mechanism of the plot. But, as elsewhere, it’s a view of women constructed by a proudly unreconstructed man, directed and photographed by men. (Eszterhas’ hard-drinking, womanizing, hellraising, Hunter S. Thompson-of-the-movies persona is enjoyably self-mythologized in his memoir Hollywood Animal.) If anything, what comes across most strongly in Eszterhas’ conception of a “strong woman” is his bafflement when tasked with imagining what such a woman might have going on inside her brain. His filmography may be full of female-fronted titles, and may contain the most famous mons venus in film history, but most of Eszterhas’ work could not be more male gaze-y f it were written from the point of view of an actual phallus, like the closing chapter of his 2000 book American Rhapsody, which is narrated by Bill Clinton's penis, Willard (I am not making this up).

This powerfully eroticized dissociation, this sexualized incomprehension of women as people with interior lives, is the animating idea behind the most Eszterhasian of Eszterhas scripts. But it’s a blank space in which directors, and especially actresses, could sometimes find room to create for themselves. Sharon Stone is genuinely, in-on-the-joke fantastic in Basic Instinct—who else could have delivered “What are you going to do, charge me with smoking?” as if it were an unreturnable Wildean riposte? Costa-Gavras’ Music Box (1989) is by some distance the sturdiest and least dated of Eszterhas movies, a lot due to its comparative sexlessness, but also because of a great, warm, real performance from an Oscar-nominated Jessica Lange. Debra Winger just about wins out in her more thankless role in Costa-Gavras’ first Eszterhas collaboration, Betrayed (1988). And Glenn Close imbues the heroine of the superior thriller Jagged Edge with such shrewdness that it’s almost a liability to the believability of the central deception.

But live by the sword, die by the sword, and when the director/actress combo fails to operate in similar sympathy we get Stone horribly miscast as a… sexy wallflower?… in Sliver, or Linda Fiorentino visibly flailing as a… downtrodden femme fatale?… in Jade, or poor Elizabeth Berkley thrashing wildly about in the neon-lit swimming pool of kitsch that is Showgirls. In these failures, the writer’s almost panicky vision of women as vast, dangerous cognitive black holes is best revealed. But then, mistrust of the opposite sex is only one aspect of the wider mystery that underpins even Eszterhas’ outlier titles: his entire output is preoccupied with how little any of us can ever know anyone.

In Eszterhas’ semi-autobiographical Telling Lies In America (Guy Ferland, 1997), a teenage Hungarian immigrant (Brad Renfro) is dazzled by Kevin Bacon's smooth-talking DJ, but blindly unable to work out if he is friend or fiend. Music Box details a lawyer’s dawning disillusionment over her adored father's murderous past—eerily mirroring Eszterhas’ discovery of his own father’s collaboration with the Hungarian Nazi regime. Betrayed has Winger’s FBI agent falling for Tom Berenger’s farmer only to discover he is, in fact, the neo-Nazi she insisted to her bosses he was not, in similar vein to Jagged Edge, in which Close’s lawyer discovers that the lover she successfully defended actually dunnit after all.

Oftentimes, the credulity-stretching ambivalence of these characters is all that powers the suspense, as in the is-she-gonna-kill-him-or-is-she-just-orgasming moments in Basic Instinct. In the misbegotten Nowhere to Run (Robert Harmon, 1993) Jean-Claude Van Damme plays a ruthless ex-con turned valiant protector, his blockish inertia apparently meant to signal that inner ambiguity. More often, it leads to final-act fake-out twists so unmoored to anything like recognizable motivation that they become weirdly weightless, as in Sliver when Stone’s Carly does not know if she’s killed the right man until the final four seconds of the film, and where, had the coin-flip gone the other way, it would still be equally (un)believable.

If it’s part of the egotistical remit of the writer to believe they have an insight into human psychology, it’s remarkable how much of Eszterhas’ oeuvre pivots around how fundamentally unknowable people are to one another. And while that schtick, by which you can’t tell if someone cares for you or is simply a talented sociopathic mimic, resonated briefly at the exact moment when the grasping, solipsistic ‘80s were segueing into the untrustworthy, PR-managed ‘90s, it proved not to have much long-game sustain. Critics had always been sniffy about Eszterhas, who clearly mopped up his tears with massive wads of 100 dollar bills. But when audiences started staying away, like in the Showgirls and Jade-blighted annus horribilis of 1995, the inflationary bubble that allowed Eszterhas to command millions for two-page outlines scribbled, one suspects, on the back of strip club napkins, abruptly burst. The idea of screenwriter-as-auteur, or rather as reliable bellwether of commercial success, proved a fallacy, an expensive experiment that began and ended with Joe Eszterhas, its earliest progenitor, luckiest beneficiary, and biggest casualty.

Glossy, vacuous, adult-themed thrillers were not the only thing going on in Hollywood, and Eszterhas was not the only big-name screenwriter. Shane Black, writer of Lethal Weapon, also commanded astronomical sums for his early ‘90s scripts, but the key difference is that Black wrote in the register of the franchise-able action-spectacular blockbuster that would eventually trounce all others as the Hollywood model for the future. Black has gone on to become part of the Marvel machine as a writer and director, while aside from one Hungarian-language period film, Children of Glory (Krisztina Goda, 2006), Eszterhas’ contribution to the pop cultural landscape post-2000 has been in the form of self-aggrandizing memoirs, or highly public fallings-out with celebrities, like Mel Gibson, of a similarly corked vintage.

The tastemaker point of view has historically been to consider Eszterhas among the worst things that ever happened to Hollywood—so much so that disdain-dripping sarcasm seems to be the fallback for critics summarizing his impact. But while no one is going to make the case for the man’s filmography as some sort of artistic landmark, the Eszterhas era did represent one of the last gasps of a Hollywood that believed, however misguidedly, in personality over product, when the idiosyncrasies, idiocies and ideologies of a single person—a writer at that—could, with studio backing and a 1,500 theater release strategy, influence the cinematic development of an entire generation. That might not have seemed like a good thing but retrospect, like cocaine, is a helluva drug and in 2019, with blandly anonymous, market-tested content churned out by mega-corporations bi-weekly to siphon your hard-earneds away, the kind of salacious tackiness Eszterhas represented feels oddly adorable, even quaint. Now that singular talents—even the obnoxious and objectionable ones—who could make decent returns on mid-budget, adult-oriented mainstream fare, have been steamrollered by infantilizing, monolithic billion-dollar mega-franchises, it’s hard not to be a little nostalgic for the vanished hiccup of time when Hollywood briefly uncrossed its legs for Joe Eszterhas, and Joe Eszterhas told us all what he saw.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’m normal now but i think i feel an itch for a writeup coming on so how normal am i. i was going to end it here but i think here’s the post in general.

general discussion of my continual disappointment with how riot handles themes and designs. isn’t really about who c is, because that doesn’t matter in the grander scheme of all of this actually. pretty jaded i must admit.

i just think that this whole thing is proof of the fact that even a lot of people invested in lore or whatever are invested in aesthetics rather than a complete and understandable narrative that doesn’t say/endorse some weird shit.

like, everyone hailing cait’s outfit as awesome and cool and her tactical outfit only being criticized for the thigh gap in the card, because hey her tits aren’t hanging out anymore! diversity win your woman is clothed!

and absolutely no one looking at caitlyn in full tactical gear with SWAT-esque armaments, ready to shoot to kill, and going “is this a good type of character to be held up as an uncritically Good And Cool Cop?” - same goes for all the other times caitlyn has been shown using force in newer canon. (i am not saying that old canon was immune to this. yordle snap traps and whatnot. but the fact that nothing has changed and has kinda gotten worse is concerning.) is it good for her to electrocute someone with her bola net (her e - which should drop anyone when fired out of a gun anyways, because bolas work just fine when hand-thrown - it is made electrified and thus more violent solely for the “cool tech factor”, i assume) in her color story and then gloat over their unconscious body? is it good for her to have flashbangs? in the wake of last summer, shouldn’t a company primarily headquartered on the west coast of the united states - whose writers tend to skew left, or at least america’s idea of the left, from what i’ve seen - at least consider what kind of message is sent when your Super Cool Cop Character repeatedly uses excessive force in her stories and is portrayed as “dangerously sexy”/”dangerously competent”? and of course vi is completely and utterly a police brutality joke. but caitlyn becoming more and more of one too, even as the issue of police brutality is in our mainstream consciousness, just makes it worse.

what kind of message is sent when, when you’re given a chance to write anything in your world that you’ve word-of-god’d to say has no homophobia and presumably has no racism (at least any akin to real-world bigotry. although xenophobia seems likely considering the everything) and you write... a cop that is just a glamorized and still sexualized (because putting more clothes on someone doesn’t necessarily make them sexualization immune!) version of the police of today? you don’t want to repeat the obvious issues of bigotry in the fantasy world, but you choose to repeat... excessively violent and corrupt cops that are complexly intertwined with those real-world issues? uncritically, too, because caitlyn is obviously held up as A Good And Efficient Cop Even If She Almost Shoots People While They’re Running Away (see the LoR teaser trailer for this set).

like... yeah. that’s a thing. but why think on that when the trigger-happy cop finally has a good outfit, yeah? that’s the real win to celebrate. or that she might have some lines to vi that you could interpret flirtatiously but probably won’t be undeniably so because it took over a decade for one canon wlw couple. is that the real win? look at our woke lgbt cops.

like yeah, i don’t expect a billion-dollar corp to criticize cops. but the least folks can do is not uncritically accept that because they’re distracted by the lower-hanging fruit of a more reasonable outfit for a female champ.

and of course the same goes for how riot handles aspects of noxus, handles aspects of viktor, handles the entirety of zaun (cait’s color story has zaunites appear as a mostly drunken crowd, by the by, which is a cool thing for your poor and downtrodden worker class that you’re supposed to be trying to make a class analogy with), handles... well, yeah, i could keep going.

but cait’s in the spotlight right now because she got a reasonable outfit and some Cool And Hot Girlboss Cop Lines, so this is about her.

yeah. i dunno. that’s the end. don’t get distracted by the pretty giftwrapping of a mediocre gift.

0 notes

Text

The Necessary Feminization of Heroes

The rise of superheroes is a phenomenon worth studying in its own right. The birth of heroes like Superman and Batman came at a time of great unrest in history. World war II was looming, and the threat of atomic annihilation was on everyone’s mind.

It’s no coincidence that the more recent popularity of superhero films began at a time of great economic unrest. We revived the old heroes, longing for a previous stability that had been lost.

The initial hype for the films was exciting, but most of that excitement seems to have fizzled off. Some blame the mediocrity of the films, but perhaps it’s because of a limited concept of what a hero can be.

They all seem to be cardboard cutouts of the same concept: a punchy do-gooder. Sometimes writers try to throw in some angst or romance to make it more interesting, but it doesn’t help much. There’s little character development, because we already know what the “hero” is supposed to be.

Their job is to be the lone ranger that punches the bad guys to save the victims. That’s all. Their work consists of punching and shooting. Nothing else.

The individuals they save play no role and have little identity besides being a helpless victim to be saved.

The plot becomes predictable because we know that no matter what, the hero is going to find a way to punch/shoot the bad guy. The villain will do nothing except get punched, the victim will do nothing but be saved.

That’s not always a bad thing. Sometime formulaic stories are enjoyable, like in detective dramas. I’m also not on an anti violence tirade. I’m just saying that interesting characters should have more, and a “hero” should have a wider definition.

One of the contributing factors of this homogeneity is the fact that most of our heroes bear masculine traits*, regardless of the individual character’s gender (more on that later). It’s possible, however, to have a hero that bears feminine traits, and it completely changes they way they relate to their world.

*When I mention the masculine and feminine, I don’t want to refer to stereotypes or some kind of idea that all men are/should be X or all women are/should be Y, nor am I talking about about gender identity. I’m speaking in the archetypal, conceptual sense, referring to a set of traits that have been traditionally labeled masculine or feminine. This is not indicative of individual, unique humans. This is purely conceptual.

The Masculine

The masculine hero is something nearly as old human civilization itself. One of the first heroic tales, The Epic of Gilgamesh, dates back to 6000 B.C. and describes a hero with the typical masculine traits that we still see today.

The typical masculine hero is:

- Individualistic (I can do it on my own, I don’t need others.)

- Brash, foolhardy, lots of dumb risks

- Brave in the face of danger

- Relies entirely on brute strength and audacity to make his way in the world

The usual endgame of the typical hero is a good deal of destruction (as long as we smashed the bad guy too, we’re good). They smash their way out of trouble and solve all their problem by punching, shooting, or blowing something up, usually through very stupid decisions.

There is an ongoing theme in a lot of superhero stories that being a hero is incredibly isolating and solidly detrimental to the individual’s relationships, though it’s not always clear why that is necessary. The hero tends to view him/herself as qualitatively separate from “victims” and does not delve much into their lives. They are merely there to be rescued.

Heroes (while in hero mode) seem to have little concept of how to interact with other people, and often switch into a hyper aggressive mode that can even turn heroes against each other.

Why is it that heroes are inescapably linked to aggression, to the point where studios are handing us films in which the heroes are fighting each other for seemingly no good reason?

Additionally, there’s no place for this kind of hero during peacetime. What do they have to offer when things are going well?

The long term outcome of this kind of heroism is not very effective. How is one man dressing up as a bat and beating on criminals going to change anything?

What if we had a hero that did not rely on rash, foolish decisions and brute strength? What if we had a hero who did not just rescue victims but empowered them to save themselves?

Suggestion: What if we had a feminine superhero?

The Feminine Hero.

The feminine hero is a nurturer. They conquer and defeat through cunning, planning and cultivation rather than brute strength.

Traits of a feminine hero:

- Does not isolate themselves. Their relationships with others are a key part of their work

- Saves through nurturing and empowering

- Relies on tact, intelligence and cunning rather than brute strength and rash decisions

- Unafraid to use violence or do hard things when necessary

- Continues to develop their community outside of crisis situations

My model for this concept is Carol from The Walking Dead. She’s managed to save the group and defeat the bad guys several times over, but never in the traditionally masculine way. She embodies the archetypal traits of a nurturing mother, while still managing to be a total badass.*

Case Study: The Walking Dead Season 6, episode 2: “JSS”

In beginning of this episode, the community is at peace. Carol can contribute and build up a community outside of a major crisis, but when a crisis comes, she knows what to do.

Murderous people invade the community while Carol is in the midst of baking a casserole and watching a baby. Instead of taking on a simple motherly role and protecting the baby from the invaders, she hands the more than capable teenage brother a semi automatic and leaves to go be a hero. The following is where the real distinction lies.

A masculine hero (like Rick, the show’s male lead) would have whipped out a big gun and stormed the bad guys, killing them all and rescuing the poor victims cowering in their homes. Carol does not do this.

She refrains from drawing attention to herself, kills without remorse when she needs to,

and disguises herself so she can move freely without gunning her way through the village.

She has a plan, a goal, and is carrying it out with tact and precision: Give everyone their own guns.

Her goal is not to obtain the macguffin or blow up the key location, but to empower others. She reaches the armory, fills a tote with guns and hands them out to all the no-longer-cowering “victims”.

The invasion is ended very quickly by empowering those under threat to save themselves. It’s a primarily “motherly” action, to nurture and strengthen others to the point where they don’t need you anymore.

There is minimal damage to the community because there was no big firefight or show of brute force. Victims are no longer faceless and helpless, creating an entirely new dynamic between the “hero” and the “victims”.

This is my proposal for a feminine hero.

*My favorite part about Carol is that she isn’t a 22 year old stripper ninja. Her main purpose isn’t to appeal to men. She saves everyone’s life as best she can, and doesn’t have to be a sex object to do it.

How does this affect gender?

It’s important to note that the masculine hero is not limited to men. Women fill this role easily, but not always with the best results. The problem with most female heroes is that they are not allowed to be anything more than the typical brash, violent and sexy cliche (I like to call it the “bossy stripper ninja”). They are not given distinct personalities, or complex motivations. They are merely “punchy”.

Who needs a deep, rich inner life when she has guns?

There are some notable exceptions. Buffy, for one, was allowed to be human, complex, AND punchy.

Most that have come after her have not been given the same generosity. The problem is, after the writer decides that a woman is “punchy”, they give up. They give her nothing else. We are hard pressed to describe this character apart from her appearance and her weapons.

Conversely, there are a number of examples of men that are masculine in character but feminine in role. That is, the individual possesses masculine traits in their personality, but they interact with the world through feminine traits (cultivation, patience, planning, etc).

The problem is, most of these examples seem to be villains. We can make a man function in a feminine way, but somehow it usually makes him a bad guy. I’m having trouble coming up with a single example of a male hero that functions through feminine traits.

Villains seem to be the only ones with tact and precision, who cultivate a world into their own vision and develop others rather than just knocking them down. They have henchmen, converts, and their own little community. Unlike heroes, they don’t stop working when there’s nothing to smash.

Examples:

Loki has a good amount of feminine heroic traits, as do most villains whose goal involves something other than blowing up the world. He is cunning, patient, and has emotional depth.

The fact that he experiences emotion doesn’t diminish his strength or power in any way.

2. Another good example is Wilson Fisk (of Marvel’s Daredevil). He’s a large man who can easily be nothing but evil and punchy, and instead possesses a rich and complex inner life and a fantastic sense of aesthetic.

Although he has his physical rages and is incredibly physically strong, he succeeds through intelligence, subterfuge and subtlety and cares deeply for those around him (beyond the typical best friend and love interest).

He’s a very masculine character, but feminine in his villainy.

3. Frank Underwood is crafty, patient and ruthless. He is a terrifying villain, because of his ability to manipulate others, stay one step ahead of everyone, and think his way out of trouble.

Writers seems to be doing a very pretty good job in developing interesting (and feminine) villains, but haven’t given us much variety in heroes.

How many of us have questioned ourselves for being far more interested in the villains? It’s because they are genuinely more interesting!

Wouldn’t it be more interesting or effective if superheroes actually got to know those they were protecting? What if Bruce Wayne befriended those who were at risk of becoming villains? What if he educated each citizen of Gotham concerning every supervillain’s weakness?

This doesn’t even take into account other important issues surrounding heroic stories, like moral ambiguity, the objectification of women, and the lack of depth in heroic characters regardless of Masculine or Feminine traits. I’m just saying we could use some variety in character traits. As Carol shows, it doesn’t make for a less interesting story. The conflict is still there. It just gets a whole lot more nuanced. We’ll always need smashy punchy stories, but can we please develop a little variety?

#fandom#feminism#marvel#dc comics#superheroes#the walking dead#carol peletier#when you make a man feminine he automatically turns into a villain#its science#my meta

7 notes

·

View notes