#internet princess

Text

Im 140 subs away from my sub goal on onlyfans! You can join now for only $3 :)

Onlyfans

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

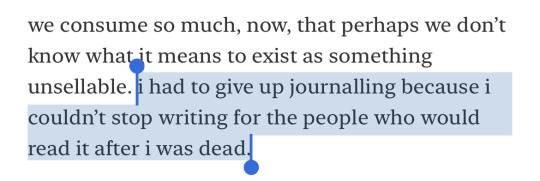

on the relationship between writer, reader, and text

rayne fisher-quann, standing on the shoulders of complex female characters | ellena savage, "yellow city" in blueberries | ellena savage, “houses” in blueberries

#the yellow city one is self-referential. she's having what can almost be considered a three-way conversation with herself#rayne fisher quann#standing on the shoulders of complex female characters#internet princess#ellena savage#blueberries#yellow city#currently reading#web weaving#parallels#rayne fisher-quann#i made this prematurely. the houses quote reminded me so much of rfq

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ur own personal pocket egirl :D

Do you want to see more of me? Click on the link above ☝️ or in my profile and write that you found me on tumblr to get a surprise!

#egirl#18+ only#alt girl#egirlhair#egirl aesthetic#egirl icons#egirloutfit#egirlsファンさんと繋がりたい#egirl style#sexy egirl#egirl makeup#egirl noods#cute egirl#hot egirls#im an egirl#am i an egirl yet#egirlvibes#e girls are ruining my life#hot as hell#internet princess#follow me uwu#uwugirl#twitch girls#big tiddy committee#pc gamer#gamergirl#kawaii girl#so cute uwu#so hot 🔥🔥🔥#soft pink

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

#2014 revival#tumblr 2014#2014 tumblr#2014 aesthetic#2014 nostalgia#i miss 2014#2014 vibes#bring back 2014#2014 grunge#2015 tumblr#tumblr 2015#2015 nostalgia#2015 aesthetic#tumblr 2016#2010s nostalgia#2016 aesthetic#2016 tumblr#2016 vibes#emoji#internet angel#internet princess

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

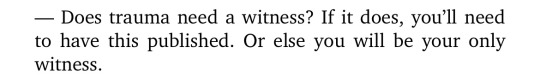

rayne fisher quann, notes from the end of summer

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

standing on the shoulders of complex female characters by rayne fisher-quann

internetprincess.substack.com

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

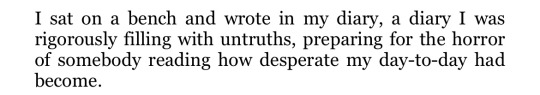

Rayne Fisher-Quann, after my own heart.

Subscribing to the Internet Princess substack has been one of the only decisions to subscribe that I have made that hasn't left me feeling empty, both in a spiritual and monetary way. It is worth every cent and the email reminding me of my payment doesn't provoke a groan the way receipts from Geoguessr do.

A quote from her newest post should persuade even the most reluctant internet citizen to bow before our Internet Princess;

(And yes I'm very aware that my cut and paste of this particular quote is incredibly contradictory to what she is about to say. But it struck me so strongly that I must do so anyways and can only encourage you to subscribe and read it yourself)

"I am fed Joan Didion and Cheryl Strayed and Ocean Vuong, Kafka and Bradbury and Carson, Jenny Slate, Sylvia Plath, Sarah Rose Etter — all in perfectly square morsels of visual text, single lines wrenched without mercy from their original artistic contexts, meant to help me microdose catharsis without having to stomach the full weight of anyone else’s grief. I open my mouth, dutifully, and swallow. I am still hungry."

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Somewhere between hyper-capitalist motivation videos, pseudo-spiritual tweets, and Instagram therapy infographics, a predominant mental-health narrative has emerged on the internet. It takes many forms, but is perhaps best defined by its penchant for isolation: it begs you to “focus on yourself,” to “protect your peace,” to sever relationships that don’t serve you and invest your newfound time and energy into self-improvement. Seductively, it whispers that you “don’t owe anyone anything.” It glamourizes — and moralizes — a life spent alone.

Sometimes, it’s dressed up in the aesthetics of corporate self-optimization: on Instagram and TikTok, viral inspirational videos collage high-contrast images of fit, light-skinned men and women studying (alone), working out (alone), going to therapy (alone), or sometimes positioned (alone, despite all contextual logic) in a party dress or tux on a New York City rooftop. As lives go, this one has a beautiful sales pitch. The videos paint a world without conflict, without pain, without uncertainty, without the tidal waves of emotion that often leave me bedridden or sobbing on the streetcar. Yes, these people may be setting up these shots by themselves, but they’re also beautiful and rich and seemingly content. The best thing about tripods, I’ve heard, is that they can’t hurt your feelings.

Alongside all the lifestyle porn is a slew of public-facing therapists and mental health influencers who promise to help you become the person you’ve always wanted to be. In her essay Less TikTok, More Screaming, Persinette writes that these e-therapists have turned healing into “a religion, a lifestyle, and above all, a brand” while promoting a culture of isolation and individual optimization. In this ecosystem, “...therapy has become a litmus test for social belonging and inherent goodness, a sign that one is aware of and has adapted to the newest standards of how to behave.”

The social standard this culture offers is one of controlled, placated solitude. Its narrative often insists that you’re surrounded by toxic people who are trying to hurt you, and the only way to ever become the person you’re meant to be is to cut them all off, retreat into a high-gloss cocoon of talk therapy and Notion templates, and emerge a non-emotive butterfly who will surely attract the relationships you’ve always deserved — relationships with other “healed” people, who don’t hurt you or depend on you or force you to feel difficult, taxing emotions. And finally, your life will be as frictionless and shiny as you, alone, have always deserved for it to be. (A frictionless life is your reward for hard work, by the way, and people who don’t work hard don’t deserve good things. DO NOT google Protestantism.)

I’m sure that the world of anti-social wellness culture is familiar to many of the readers of this essay; we’ve all seen the viral text-message templates and disturbing Reddit posts that typify the movement. For some of you, I’m sure this culture has also been relatively easy to reject. I, for one, have always found it almost too easy to look down on this movement, with its “Go To Therapy” t-shirts and its buzzword-laden infographics; it’s only recently that I realized I’ve spent my life indulging an eerily similar and far more insidious flavour of isolation.

Here’s the long and the short of it: I may have never felt the need to cut my friends out of my life in service of my own optimization, but I still don’t answer their texts. I can’t help but feel crushed by the weight of what I owe to my community, certain I’m going to hurt the people I’ve fooled into loving me, convinced that I’m doing them a favour by icing them out until I get my shit together. I am too loud, too self-involved, too insensitive, never caring enough or attentive enough or possessing enough natural kindness. I have made people I love feel alone when they needed me; I have been cruel to people I never wanted to hurt. Like many — dare I say, most — people in their early 20s, I find it hard to shake the feeling that my life is a pinball machine of relationships and opportunities that I’m hurtling through headfirst, knocking over bystanders and crashing into obstacles, unable to stop for long enough to figure out what I’m doing wrong. It is tempting, in this world of alarm-bells and flashing warning signs, to want to trap myself in a room where there’s nothing to bounce off of but myself.

The worst thing about this feeling is that it makes you a martyr. You may hate yourself, but you’re also a hero, bravely forgoing love and connection and community to protect the world from the car-bomb of your own instability. You sit in your room and tell yourself lies: that they don’t want to hear from you anyway; that you’ll wait here alone writing Notes app soliloquies until you become good enough to deserve other people; that it is a noble endeavour to punish yourself.

And so I ignore my friends’ texts. My motivations tend to skew self-destructive rather than ruthlessly self-optimizing, but I’m beginning to suspect that there’s hardly any difference worth writing about. Doesn’t aspiring to construct a perfect self imply a desire to destroy the current one, anyway?

Martyrdom feels entirely at odds with the self-optimizing solitude you see advertised by Instagram infographics and Twitter therapists — if you relate to one of the two phenomena, you likely feel completely repulsed by the other — but I think they are far more like mirror images than opposites. Both strategies rely on the fantasy that isolation can eliminate harm to yourself or others. They both use the idea of your own healing as a metric for the kind of relationships you deserve to experience. Both centre around the same fundamental belief that we have to be perfect in order for people to love us, or to be deserving of the love we’ve been given. Most damning of all, they are both infected by the same rotten premise: that it is possible, even ideal, to get better by yourself.

It’s an intoxicating idea in part because isolated healing is a study in false negatives. When relationships are made difficult by traumas, anxieties, and neuroses — and when those issues are triggered as you navigate complicated relationships — being alone really can feel a lot like being cured. Relationships with other complex, flawed people are beautiful and transformative and fulfilling, but they’re also inherently maddening, infuriating, hurtful, stressful, and yes, triggering. It is ideal, of course, for us to work to understand those conflicts and thereby make them less destructive to ourselves and others, but we can’t make those feelings disappear; nothing real can have contact without friction. If you’ve been encouraged to define a healthy life as a frictionless one, I think it may be inevitable that a life devoid of contact starts to feel like healing.

And here’s the thing about friction: it really does hurt. Isolationists have one very strong argument on their side — when you’re alone, there’s no one there to hurt you, even accidentally. There’s no one there to throw your own flaws into stark relief. There’s no one who you might hurt with bursts of uncontrollable emotion or human carelessness. It’s hard to be hurt, and perhaps even harder to hurt the people you love — why not cut the risk, lock the doors, and live a life of robotic, impersonal, action-oriented optimization?

The answer, of course, is that none of us are any good alone.

It is a cruel and fundamentally inhuman tragedy that the culture has convinced so many of us that we must be healed in isolation, because being surrounded by people — people who love us, or care for us, or are willing to sit in the same room with us while we clean up our messes — is about the only way that I, for one, have ever been able to get better. I am lucky enough to have been changed again and again and again by the people who have loved me or challenged me; I look back at the person I was at eighteen and I hardly recognize her, which feels like a miracle and a tragedy all at once. Standing between me and my younger self are a thousand different individual experiences of failure and growth and redemption, each a moment of excruciating vulnerability being witnessed by the very people I wish could only see me at my best. It’s driven me to isolate myself, convinced that ritualistic self-punishment and pathetic martyrdom were the only ways I could ever make myself worthy of other people. I realized, though, that I was being a coward. Being alone is hard, to be sure, but it’s also deceptively easy — it requires nothing of us.

People, on the other hand, challenge us. They infuse our life with stakes. You can hurt a friend or partner or lose them forever if you refuse vulnerability or reject growth — the same cannot be said of a therapist, for instance, which makes them far safer companions. Therapy, while genuinely beneficial in many forms, has started to become homogenized in the personal-wellness zeitgeist as a kind of resume-builder for the self; a box to check off on the way towards becoming a hyper-functional young professional in life and love. “I only date people who go to therapy” has become a nearly unavoidable refrain in dating app bios and viral tweets. Many of us conspicuously signal our enrollment in therapy in order to make ourselves more viable candidates for love and friendship — to show, again, that we are doing the work that will make us worthy of salvation. If you go once a week, pay $200 a session, scribble in the worksheets, have the tough conversations, and Do The Work, perhaps you can come out the other side clean and clear, unblemished by uncontrollable emotion or idiosyncrasy or errant needs. It’s a satisfying transaction, to be sure — one that gives people the quantifiable markers for success that form the fundamental currency of capitalist society.

I’m not trying to discount the genuine benefits that therapy can provide. A good therapist really can help you notice your blind spots, recognize and process your emotions, and build healthier relationships, and I know many people (including myself) who have reaped great benefits from therapy. My problem is the positioning of a one-size-fits-all solution as the only way to become a good, functional, whole person — and the idea that one must be “whole” in order to love or be loved.

It almost goes without saying that having mainstream therapy be a social prerequisite for community and connection is a deeply exclusionary practice: most therapy is prohibitively expensive, and the psychiatric institution can be a deeply traumatizing and destructive force in the lives of many mentally ill people. But even outside of the material barriers imposed by this kind of standard, I am troubled by its implication: it insists that healing is a mountain to be climbed alone, and that relationships are the reward we get once we’ve reached the summit. When we insist that we could only ever effectively love someone who’s been perfectly “healed” — who will not struggle, accidentally hurt us, trigger us, say the wrong thing, do the wrong thing, or participate in any other uncomfortable display of humanity — we are reinforcing, and perhaps projecting, our own beliefs that we have to be perfect in order to be loved.

There is one way to reject this: make the choice to love someone who is as flawed as you are. One of the most remarkable pleasures that love has to offer, in fact, is the feeling of meeting someone who is scarred and beat-up and bruised, too emotional or not emotional enough or oscillating wildly between the two, and offering to love them enough to help them get better (and, of course, to have them do the same to you). To grow beside a friend or lover, knowing that you will poke and prod at each other as you take shape but unafraid of the resulting scar tissue — this is the good stuff.

Call me conspiratorial, but when I see the brightly-coloured Instagram posts encouraging me to cut off my friends and focus on myself, I can’t help but notice a convenient side effect of isolation: it forces us to rely on paid relationships in order to grow. The relationship between you and your therapist is transactional and safe, free of the messiness of attachment or stakes or love. And there are times, to be sure, when that can be a very useful relationship to have. But a serious issue arises when professional, unattached relationships are positioned as a replacement (or a requirement) for fulfilling, challenging, passionate ones. When people say that one ought to go to therapy to become a perfectly stable, functional, “healed” individual before they dare try to experience love or community, they are imagining a world in which a fundamental purpose of human connection has been replaced with a capital exchange. Welcome to the ideal relationship: one between two perfectly realized individuals who would be totally fine alone but choose to hang out because they like splitting rent and watching Law and Order. No passion, no growth, no difficult conversations — that’s your therapist’s job.

To be clear, the idea that it’s not our job to “fix” one another is a piece of pop conventional wisdom that developed, at least in part, for understandable reasons. It’s undeniable that people (usually women) can be expected to manage a vastly unfair share of emotional labour in their relationships, often at great personal expense. We are encouraged to ignore abusive behaviour for the sake of our abusers or told that abuse can be prevented by becoming more generous, more loving, more permissive. This is both deeply damaging and patently false. It’s never your responsibility to make someone stop hurting you, whether they mean to or not — and I don’t think you can truly help someone while they’re hurting you, anyway. If we agree that our well-being is inexorably linked to the well-being of our communities, it becomes clear that nothing generative — nothing truly healing — can come from destroying yourself trying to save someone else.

Believing in the power of love and community as a redemptive force doesn’t mean that we should give ourselves endlessly to everyone around us. I’ve had to remove people from my life because their circumstances made it hard for them to stop hurting me in some way or another, and I’ve had people remove me from their lives for the same reason. These were sad and difficult times in which we all learned that it is often impossible for us as individuals to save someone we love from the sum of their suffering, especially so when you’re ignoring your own needs in the process. But to extrapolate that reality into the idea that we shouldn’t want to tend to our loved ones, to receive them as flawed and imperfect people and care for them anyway, is a grave miscorrection. We all exist to save each other. There is barely anything else worth living for.

Rather than being a gradual, non-linear journey towards realization and fulfillment, we’ve begun to imagine "healing" as a series of personal-discovery tasks that exist to make the self more comprehensible. We’re encouraged to enumerate our flaws, systemically comb through our childhoods for neat, pert little stories that can explain how each of them came to be, and then destroy them. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with wanting to understand ourselves.

But if going to therapy has taught me anything, it’s that nothing is actually solved by intellectualizing and pathologizing every part of what we feel — and when we try, we’re usually sort of wrong anyway. Your emotions, by and large, are not a problem to be fixed in service of producing a better, more manageable, more loveable self. They just want to be felt.

The process of becoming yourself is not a corporate desk job, and it is not homework, and it is not an unticked box languishing on a to-do list. You do not have to treat your flaws like action items that must be systematically targeted and eliminated in order to receive a return on investment. You have no supervisor; you should not be punished when you fail. Your job is not to lock the doors and chisel at yourself like a marble statue in the darkness until you feel quantifiably worthy of the world outside. Your job, really, is to find people who love you for reasons you hardly understand, and to love them back, and to try as hard as you can to make it all easier for each other.

It’s hard, certainly — it’s painful and exhausting and fundamentally terrifying to rip yourself open and leave the guts at the mercy of the people you choose to love. But if I know anything, I know this: It’s better than being alone.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

had to bring out the tattoo choker

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

want a sweet treat? 🍩

~ ♡ click big text to chat with and me get more noods :p and PM me ON FANSLY the word "tumblr" to get a free video (✧ω✧)

#egirl#18+ only#alt girl#egirlhair#egirl aesthetic#egirl icons#egirloutfit#egirlsファンさんと繋がりたい#egirl style#sexy egirl#egirl makeup#egirl noods#cute egirl#hot egirls#im an egirl#am i an egirl yet#egirlvibes#e girls are ruining my life#hot as hell#internet princess#follow me uwu#uwugirl#twitch girls#big tiddy committee#pc gamer#gamergirl#kawaii girl#so cute uwu#so hot 🔥🔥🔥#soft pink

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

in conversation with myself, rayne fisher-quann

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

wanna see what lies beneath these clothes?

Do you want to see more of me? Click on the link above ☝️ or in my profile and write that you found me on tumblr to get a surprise!

#egirl#18+ only#alt girl#egirlhair#egirl aesthetic#egirl icons#egirloutfit#egirlsファンさんと繋がりたい#egirl style#sexy egirl#egirl makeup#egirl noods#cute egirl#hot egirls#im an egirl#am i an egirl yet#egirlvibes#e girls are ruining my life#hot as hell#internet princess#follow me uwu#uwugirl#twitch girls#big tiddy committee#pc gamer#gamergirl#kawaii girl#so cute uwu#so hot 🔥🔥🔥#soft pink

37 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Your emotions, by and large, are not a problem to be fixed in service of producing a better, more manageable, more loveable self.

Rayne Fisher-Quann

#rayne fisher quann#internet princess#i just discovered her essays on substack today#and they are very good

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

This one really stuck out in my inbox today. Give it a read.

Bonus that image referenced is one of my favorite paintings (that i saw again recently when it was visiting the Whitney in the Edward Hopper exhibit.)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does anyone know if rayne fisher-quann of tiktok and twitter fame has a tumblr?

#raynefq#rayne fisher quann#internet princess#twitter#tumblr#tiktok#just in case twitter dies#hopefully it won’t#but it might#also I’m not a twitter refugee btw#I have been here since the ye old days#this is just a new blog#does anyone know if rayne fisher quann has a tumblr

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

By now, the defamation trial between Johnny Depp and ex-wife Amber Heard over her allegations of domestic abuse has become virtually inescapable. With terrifying inertia, the trial has become a vicious battleground for a maelstrom of cultural forces: the hatred of women, the fear for men, the obsessive consumption of real-life tragedy, the aftershock of the MeToo movement, the influencer attention economy. The resulting political event is something akin to a cultural coup, and it’s also one of the most toxic and terrifying eruptions of cultural misogyny that I’ve seen in my lifetime.

Despite the now-popular push to condemn both Amber and Johnny as terrible people and wash your hands of the discourse, I’m not interested in refusing to “take a side”. I’m not the first person to point out that much of the reasonable criticism of this trial tries to have its cake and eat it too; it attempts to criticize the misogynistic, dehumanizing circus around the trial without taking a meaningful stance on the abuse itself. As Caroline Walsh-King writes in her excellent essay We Don’t Want To Believe, much of the popular progressive coverage around the case focuses on “scolding the public for our behaviour… because this will cause damage to “real” victims, without engaging with what it means to leave Heard’s victimhood status to be defined by a judge or jury.” Staying neutral is understandable — I can understand anyone wanting to avoid the wrath of the Depp death cult — but I think it misses the mark. We gain nothing by refusing to address the complexities of abuse. We lose everything by creating a dichotomy between Amber Heard’s story and the theoretical stories of good victims, better victims, “real” victims — while, in the process, implying that her sustained public degradation is only bad because of what it will do to less difficult women.

I have no interest in beating around that bush. I have a great deal to say here, but I want to say this clearest of all: I believe that Johnny Depp is a misogynist, abusive, serially violent wifebeater, and I believe that he owes his cultural victory to a combination of celebrity worship, targeted right-wing propaganda, and vicious, vitriolic misogyny.

One of the most frustrating aspects of the cultural response to the suit is the sheer volume of people now insisting that it’s both radical and necessary to declare that women can lie. “Women CAN do bad things,” proclaim the viral tweets and pseudo-philosophical TikToks, boldly assuming an affect of subversion despite occupying the same philosophical position as a sanitorium baron from 1955. If the never-ending barrage of amateur political punditry on the internet is to be believed, we need to be having this conversation, lest feminism go too far (nevermind the fact that women’s liberation is no nearer now than it was before #MeToo went viral on Twitter). The idea that the dominant culture has moved forward enough for the systemic distrust of women to be anything other than a default setting is somewhere between bizarre fantasy and bold-faced manipulation: in reality, everyone still thinks women are lying all the time, and they never stopped for a second.

The spectacle around the Depp trial is being called a large-scale backlash to the MeToo movement, and I don’t disagree — but this is uniquely terrifying because I don’t think the mainstream MeToo movement was ever actually materially effective in the first place. In Walter Benjamin’s essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, he writes that an oppressive structure “sees its salvation” in allowing the masses to express themselves freely in lieu of granting them their rights. Similarly, the mainstream MeToo movement offered temporary catharsis in place of systemic change; Hollywood play-acted a revolution so that its men could keep up their abuse unscathed. There is something phenomenally painful in watching a material backlash erupt in response to a movement that was never allowed to be anything more than aesthetic. Now that the state of discourse has moved forward without bringing women’s material conditions with it, men like Johnny Depp are able to benefit from violent systemic misogyny while posturing themselves as radical, anti-establishment activists. Recent events are not so much a pendulum swing as they are a pendulum being repeatedly beaten in one direction for fear it might one day gain a centimetre of ground. [...]

For the vast majority of casual spectators, the idea that Amber Heard might be a victim is unimaginable. Pro-Depp media has dominated the internet for the duration of the trial, and most of it represents very little of the valid evidence against him. The vast majority of it, too, is largely based in aggressive sexism and strategic right-wing rhetoric — The Daily Wire, Ben Shapiro’s conservative news outlet, spent tens of thousands of dollars promoting biased anti-Heard propaganda. The right-wing connection to the trial is expansive and terrifying in its own right: on the subreddits that serve as home base for Depp’s proponents, tens of thousands of relatively apolitical fans are abandoning mainstream media in favour of increasingly conservative pseudo-news sources that support their cause. Countless right-wing pundits and commentators have latched onto the pro-Depp movement as a gateway to new, young audiences, and even the official GOP Twitter account posted in support of Depp’s victory. [...]

Depp’s propaganda machine has effectively obfuscated most of the valid evidence against him, as well as engaged in a large-scale smear campaign designed to paint Heard as a crazy, manipulative abuser determined to take him down at any cost. Even those who are critical of Depp often dismiss the case as an example of “mutual abuse”, wherein both parties were equally at fault and neither one can claim victimhood. In reality, the actual evidence around Heard’s case paints a very different story. In Michael Hobbes’ article The bleak spectacle of the Amber Heard-Johnny Depp trial, he goes through the facts in a way that makes the truth much clearer. I encourage you the read the whole thing. Much of the article draws from Heard’s testimony, but even if you’re critical of her word alone, there’s more than enough material evidence and eyewitness accounts to corroborate a story of long-term psychological and physical abuse that began when she was 23 and Depp was 46.

Numerous audio recordings show Depp admitting to explosive and violent behaviour, and some capture the outbursts themselves. In one recording, Heard says, “I cry in my bedroom after I dumped you a week prior after you beat the shit out of me.” Depp replies, “I made a huge mistake. I won’t do it again.” Texts show him using homophobic language and violently misogynistic slurs against Heard, who is bisexual: In texts to Paul Bettany, he said he wanted to drown her, burn her, and rape her dead body “to make sure she’s dead.” He also called her a “lesbian camp counsellor,” "ugly cunt," "worthless hooker" and "filthy whore”, and promised in a text message about Heard to “smack the ugly cunt around”.

Heard has a mountain of documentation to support her claims of over 10 counts of violent physical abuse, including photos of bruises, witnesses corroborating those bruises, several witnesses reporting seeing Heard with cuts and chunks of missing hair, recordings of Depp’s verbally violent outbursts, and texts throughout the entirety of their relationship confirming Heard’s accusations. “Both Heard’s and Depp’s texts from their relationship confirm her basic outline of events,” writes Hobbes. “From the earliest incident of violence, Heard told friends and family about his jealousy, his attacks, and his denials. The UK trial includes a text from Depp’s assistant after the private-jet blowup saying, “when I told him he hit you, he cried.”” Depp has an almost ridiculously well-documented multi-decade history of physical violence, rage-induced outbursts, destructive behaviour, and extreme misogyny; he is about to go on trial for another act of physical violence against a crew member.

Meanwhile, many of the popular talking points levied against Heard are questionable if not completely fabricated. As Hobbes writes, “At the center of this case is a wildly plausible, evidence-backed story of abuse.”

And again, this is not to say that Amber Heard is perfect. She was cruel. She was callous. She’s lied, just as Depp has. Most importantly, like many, many women trapped in long-term abusive relationships, she absolutely engaged in emotional toxicity and a degree of physical violence. For anyone familiar with cycles of domestic abuse, this is nothing new — reactive violence is an extremely common result of the psychological degradation and fear responses that come with sustained abuse. Of course, violence is never okay, but the complete dehumanization of women who behave imperfectly in torturous circumstances is just one half of a Catch-22 which conspires to keep all women silent. If you were abused and did nothing, they’ll say you weren’t abused at all, and so you’re a liar and therefore an abuser; if you were abused and you fought back, then it means you were the abuser to begin with.

Johnny Depp has used every weapon in his artillery to paint a detailed and specific picture: one of a crazy, scheming woman who spent over a third of her life crafting a conspiracy to bring down the thriving career of a beloved celebrity and boost her own in the process. It’s a familiar caricature, and one that’s been used to discredit and demonize women for hundreds of years.

Allow me to paint a more realistic one. Johnny Depp’s career has been fizzling out for years. He’s spent the 2010s putting out the lowest-rated performances of his career and watching his star power and cultural currency fade as he sunk further into bouts of addiction and self-destruction, while surrounding himself with misogynists and abusers at every turn. He’s accused Heard of dragging his name through the mud for attention, despite the fact that she never even used his name at all — instead, he instigated the public battle, had the trial be televised, and summoned the media circus. Now, he’s beloved again, and more popular than he’s been in over a decade.

Unlike Depp (and many of his acolytes), I find no value in flattening the experiences or motivations of either party in this case to fit an easily consumable Marvel movie plotline. I’m not interested in buying into the dominant narrative that treats this trial like a soap opera, with characters that exist to be rooted for and against. Much of the popular discourse acts as though there are only two feasible options when it comes to Heard’s (and, really, any woman’s) innocence: either she’s an evil, psychotic manipulator who’s guilty on all counts, or she must have to be a perfectly innocent angel who’s never done anything wrong. I don’t think Amber Heard is a feminist hero, and I’m not saying this to make my support of her more palatable or to perform impartiality — I’m saying it because she shouldn’t have to be. I think it’s essential to a much larger point (and, in reality, far more controversial) to believe Amber Heard is a victim while also acknowledging her wrongdoings. Once you start pushing the idea that a woman has to be perfect in order to be believed, you head down a road that ends with the systemic exorcism of any woman too human to be a good victim.

Those who believe Amber Heard are often accused of ignoring the truth to capitulate to a convenient girl-power narrative. The obvious flaw in this argument is that absolutely nothing about Amber Heard’s victimhood is convenient. I’ve been told multiple times, point-blank, to leave the Amber Heard case alone and focus on picking an easier subject; it’s become a common pseudo-feminist diatribe to insist that Heard is “setting the movement back”. For decades, the dominant pop-feminist ethic has focused on boosting the stories of “good” victims — victims whose experiences with abuse seemed so cut-and-dry, whose innocence was so indisputable, that it seemed no sane person could disbelieve them. The trick, though, is that every woman stops being “good” once they decide to resist abuse, and so no victim could ever be good enough to avoid scrutiny. Even still, feminists have been encouraged to leave the stories of difficult women in the dust, lest they hurt our cause with their complexity — again, we’re fed the myth of the model victim and told to focus on defending the good girls. [...]

Heard’s story is a study in damnation, and it’s not a new one — when she didn’t have photographs of the abuse, it was proof she was lying. When she did, it means she faked them. When she had no witness accounts, it meant the violence never happened; when she did, it was proof she planned a grand conspiracy to bring Depp down. She was too loving at some points, too cruel at others; either so calm and collected that she must be lying or so distraught and uncertain that she must not know what she’s talking about. Amber Heard might not be a perfect victim, but she sure as hell is a typical one.

And still, the vast majority of participants in the zeitgeist purport to be defending victims even as they take part in Heard’s mass victimization. Even those who consider themselves progressive feminists insist that Amber Heard has no place in the movement against domestic violence. In the process, they’re crafting a blind, toothless framework for understanding abuse that will end up failing each and every woman who needs it.

This is a great contradiction of the internet age: the act of saying you’re a feminist and the act of engaging in feminism are two entirely disparate inclinations, sharing little in common when they’re not actively at odds with each other. Everyone thinks they’re a feminist now. Everyone thinks they believe women. Few actually are; few actually do. Believing women in theory is much easier than engaging with the messy realities of victimhood. The dissociation of political identity from material reality has become so essential to popular discourse that one can truly, genuinely believe they support victims of abuse while operating within a community that needs to be reminded via Jim-from-The-Office meme that not all women are lying psycho bitches.

Depp’s supporters wish death upon a woman whose husband went on the record saying he wanted to rape her lifeless body. They make half-jokes about hoping she starts stripping or gets on OnlyFans now that she is destitute at the hands of litigative and financial abuse (no matter how much men purport to hate a woman, by the way, they will still hunger to see her naked — in fact, their desire to fuck her is central to their hatred). They laugh at the photos of her bruises and memeify the makeup she used to cover them. And through it all, they still honestly insist that they’re on the side of all victims everywhere, despite the fact that most victims of abuse are made to look a lot more like Amber Heard than anyone wants to admit.

So if you’re one of the many people saying that you “believe victims, just not Amber Heard” — that you don’t think all women are psycho bitch liars, just Amber Heard — I sincerely regret to inform you that you are lying to yourself and others. Here’s the long and the short of it: if you can take an honest look at the evidence in front of you and not believe that Amber Heard is a victim of abuse, there are exceptionally few women who you actually would believe if they were to receive the same treatment.

For women, this truth is terrifying. I understand why it’s far easier to bury our heads in the sand and insist that Heard deserves what’s coming to her — this validates the pipe dream that there’s some level of respectability women can reach which will free us from the violence of patriarchy. Women align themselves with power because they think it means that when their backs are against the wall, power will align itself with them, too. I think that’s precisely why so many abuse survivors threw their support behind Depp so publicly. Time and time again, I saw women online insist that they were real victims, and they would never be so cruel, so angry, so manipulative, so dishonest. They would have more proof (never mind the fact that Heard had lots of it); they would have behaved better (because they’re good women, undeserving of abuse, and she’s a wicked one). I understand the impulse; I understand the fear. I hope it’s clear that I don’t say this with the intention of engaging in holier-than-thou judgement — rather, I say it as a desperate plea for women to understand that aspiring to perfect victimhood on the backs of imperfect women will fail them just as it has failed me.

This trial has conjured, in perfect, terrifying detail, a near-comprehensive list of reasons why any woman can be discredited, villainized, and crucified in the court of public opinion: if you ever dared to do anything but lie down and let yourself be hurt. If you’re mentally ill, or if you can reasonably be painted as mentally ill. (Womanhood is basically a symptom in and of itself, by the way — the psychiatrist who spot-diagnosed Amber Heard with histrionic personality disorder literally cited being “overly girly” as evidence.) If he's charming enough, handsome enough. Even if he's not handsome anymore — even if, hypothetically, he looks like a leathery skin sack gently deflating before our eyes as he leaks grease and prescription benzos — they will remember that he once was, and it will be enough. Whether it be with Johnny Depp or Brock Turner, the fantasy of a man’s illustrious past or bright future will always take priority over a woman’s present.

They’ll make him a folk hero. They’ll call him a feminist. He’ll sell fucking NFTs dedicated to furthering your humiliation and degradation. And despite it all, you will be the one called the attention-hungry slut desperate to manipulate your way to the top.

The cornerstone of Johnny Depp’s case is that Amber Heard fabricated the accusations against him in a carefully constructed plan to further her own career. He knows this is a lie, by the way, because the idea that any woman could get ahead in Hollywood by taking a vocal anti-abuse stance is a fabrication that only the most impressionable of celebrity sycophants could ever believe. Apparently, any woman who speaks a truth that threatens power is now at risk of being sued for defamation, so I’ll be strategic: I think Hollywood is run by rapists and womanbeaters. I think the commercial #MeToo movement served only to remove a few sacrificial lambs from the herd so the rest could continue business as usual unscathed, shaking their heads and tut-tutting at the few men who faced consequences before returning to business as usual. I think that women who speak out about sexual assault in Hollywood are immediately blacklisted from the industry with such swiftness and efficiency that we don’t even know (or remember) most of their names. And I know, deeply and ultimately, that the idea that any woman’s social standing within a violently patriarchal institution could possibly be improved by publicly fighting abuse is a collective fantasy-slash-delusion strategically sewn together by those in power.

I’ve been saying it since 2018: Powerful men don’t fear the consequences of committing sexual violence. They fear being one of the unlucky few who’s chosen to publicly face some degree of accountability so the rest can continue to violate women in peace. And now, the most influential among them don’t even fear that anymore, because Depp has proven that our culture will be far quicker to circle their wagons around a man whose image is under threat than to consider for a second that a woman might be telling the truth. There’s a reason why defamation suits in particular are becoming abusers’ first line of defence: a man’s reputation has always been considered more precious than a woman’s life.

Johnny Depp has created a new playbook for getting away with murder — which is to say he’s used the oldest playbook in the world to appeal to our cultural fear of a crazy, manipulative psycho bitch and craft a narrative in which it’s okay to beat her. It’s a playbook every man in Hollywood is preparing to adopt to get back at the women they’ve abused. It’s a playbook that will trickle down to the masses — if you’re a woman, it’s a playbook that may be used against you, if it hasn’t been already. If you’ve ever raised your voice, retaliated with cruelty, lost yourself in the depths of an unspeakably cruel and mind-twisting relationship, or, god forbid, hit back, this spectacle has proven that you, too, can be dehumanized within an inch of your life until the question is almost no longer whether or not you’ve been hurt, but whether or not you were insane enough to deserve it. Once the conversation gets to this point, by the way, the answer will always be yes.

What’s happening to Heard is no accident. It’s a cosmic punishment rained down from every aspect of the patriarchal establishment — mainstream Hollywood, right-wing media, the GOP — that’s intended not only to kick her down one last time for daring to stand back up in the first place, but to serve as a looming warning to every woman who might be considering doing the same.

I’ve seen many people in progressive circles question why we should care about the problems of a rich, white, beautiful celebrity. While I understand the exhaustion with what appears to be distracting tabloid drama, to me, the answer is clear: if this could happen to Amber Heard, it could happen to anybody. Any strategy that capitalizes on the cultural fear of an angry, aggressive, crazy woman to justify financial and legal abuse will be used a thousandfold on more marginalized women who don’t have access to Heard’s social, cultural, or monetary currency. And when you consider how quickly and effectively the right-wing institution monopolized this case, I would go so far as to say that’s exactly the point — by making a spectacle of the public humiliation and degradation of a rich, famous, beautiful white woman at the pinnacle of worldly privilege, the patriarchal establishment intends to make sure no woman feels safe resisting abuse ever again. That will certainly be the effect if we don’t fight it as swiftly and as strongly as we can.

4 notes

·

View notes