#hanna brenner

Text

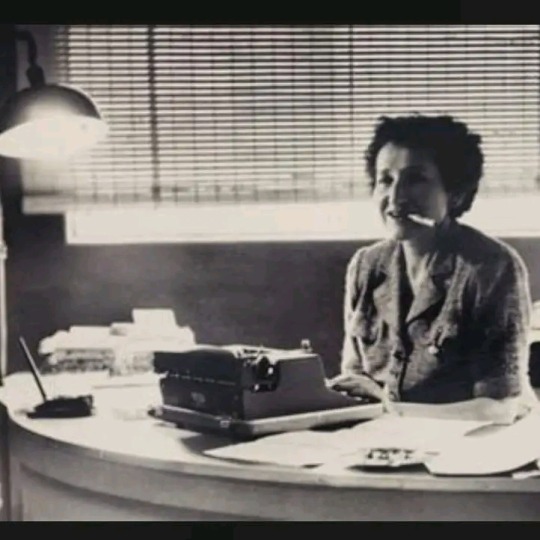

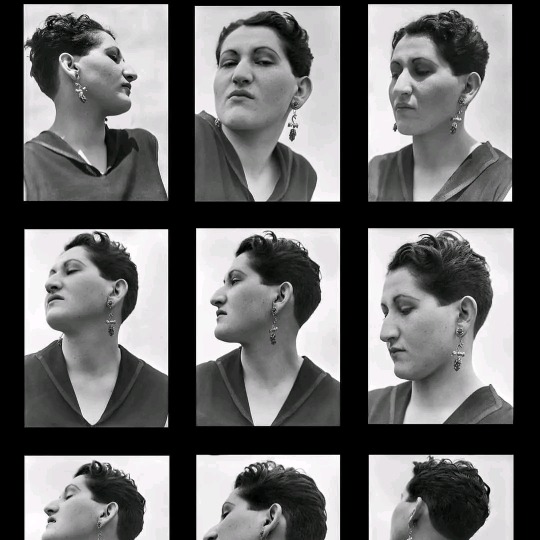

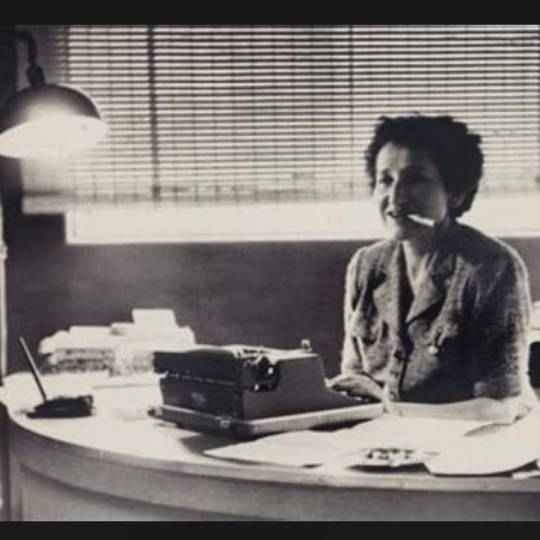

Tina Modotti :: Portrait of Anita Brenner, ca. 1925. | meisterdrucke

#portrait#Bildnis#anita brenner#writer#women artists#tina modotti#hanna brenner#anita glusker#headger#hat#Schriftstellerin

329 notes

·

View notes

Text

German tv shows with lgbt* characters

I think it can be quite hard to find queer german tv shows, so I thought I‘d compile a list with the ones that I have watched so far.

✪ = queerness is centered in this show

A-Z

1899 (2022) (mlm) | Netflix | international

Ángel (Miguel Bernardeau)

Ramiro (José Pimentão)

Krester (Lucas Lynggaard Tønnesen)

All you need (2021-) (mlm) | ZDF | ✪

Vince (Benito Bause)

Robbie (Frédéric Brossier)

Levo (Arash Marandi)

Tom (Mads Hjulmand)

Andreas (Tom Keune)

Barbaren (2020-) (mlm) | Netflix

Marbod (Murathan Muslu)

Flavus (Daniel Donsky)

Beat (2018) (mlm) | Prime Video

Beat (Jannis Niewöhner)

Becoming Charlie (2022-) (trans, mlm, wlw) | ZDF | ✪

Charlie (Lea Drinde)

Ronja (Sira-Anna Faal)

Mirko (Antonije Stankovic)

Blutige Anfänger (2020-) (mlm) | ZDF, YT

Michael Kelting (Werner Daehn)

Dr. Claas Steinebach (Martin Bretschneider)

Bruno Pérez (Martin Peñaloza Cecconi)

Phillip Schneider (Eric Cordes)

Charité (2017-) (wlw, mlm) | Netflix

Schwester Therese (Klara Deutschmann)

Otto Marquardt (Jannik Schümann)

Martin Schelling (Jacob Matschenz)

Dark (2017-2020) (wlw, mlm, trans) | Netflix

Peter Doppler (Stephan Kampwirth)

Bennie Wöller (Anton Rubtsov)

Doris Tiedemann (Tamar Pelzig/Luise Heyer)

Agnes Nielsen (Helena Pieske/Antje Trauer)

Deutschland 83/86/89 (2015-2020) (wlw, mlm) | Prime Video

Alex Edel (Ludwig Trepte)

Prof. Tobias Tischbier (Alexander Beyer)

Lenora Rauch (Maria Schrader)

Rose Seithathi (Florence Kasumba)

Dogs of Berlin (2018) (mlm) | Netflix

Erol Birkan (Fahri Yardim)

Guido Mack (Sebastian Achilles)

Dr. Klein (2014-2019) (mlm) | Netflix

Patrick Keller (Leander Lichti)

Kaan Gül (Karim Günes)

DRUCK (2018-) (wlw, mlm, trans) | YT | ✪

Fatou Jallow (Sira-Anna Faal)

Matteo Florenzi (Michelangelo Fortuzzi)

Zoe Machwitz (Madeleine Wagenitz)

Kieu My Vu (Nhung Hong)

Isi Inci (Eren M. Güvercin)

David Schreibner (Lukas von Horbatschewsky)

Yara Aimsakul (Elena Plyphalin Siepe)

Hans Brecht (Florian Appelius)

Eldorado KaDeWe – Jetzt ist unsere Zeit (2021-) (wlw) | ARD

Heidi Kron (Valerie Stoll)

Fritzi Jandorf (Lia von Blarer)

How to Sell Drugs Online (Fast) (2019-) (wlw) | Netflix

Fritzi (Leonie Wesselow)

Gerda (Luna Baptiste Schaller)

Kitz (2021) (mlm) | Netflix

Kosh Ziervogel (Zoran Pingel)

Hans Gassner (Ben Felipe)

Ku‘damm 56/59/63 (2016-2021) (mlm) | ZDF

Wolfgang von Boost (August Wittgenstein)

Hans Liebknecht (Andreas Pietschmann)

Der Kroatien Krimi/Split Homicide (2016-) (wlw) | ARD

Stascha Novak (Jasmin Gerat)

Loving Her (2021) (wlw) | ZDF | ✪

Hanna (Banafshe Hourmazdi)

Holly (Bineta Hansen)

Franzi (Lena Klenke)

Lara (Emma Drogunova)

Josephine (Karin Hanczewski)

Anouk (Larissa Sirah Herden)

Sarah (Soma Pysall)

Mord mit Aussicht (2018-2022) (wlw) | Netflix

Bärbel Schmied (Meike Droste)

Neumatt (2021-) (mlm) - Switzerland | Netflix

Michi Wyss (Julian Koechlin)

Joel Bachmann (Benito Bause)

Polizeiruf 110 (1971-) (queer/gnc) | ARD

Frankfurt/Świecko

Vincent Ross (Andre Kaczmarczyk)

SOKO Leipzig (2001-) (mlm) | ZDF

Moritz Brenner ( Johannes Hendrik Langer )

Tatort (1970-) (mlm, wlw) | ARD

Berlin

Robert Karow (Mark Waschke)

Hamburg

Julia Grosz (Franziska Weisz)

Saarbrücken

Esther Baumann (Brigitte Urhausen)

Wien

Meret Schande (Christina Scherrer)

Vorstadtweiber (2015-) (mlm) – Austria

Georg Schneider (Jürgen Maurer)

Joachim Schnitzler (Phillip Hochmair)

WIR (2021-) (wlw) | ZDF

Annika Baer (Eva Maria Jost)

Helena Kwiatkowski (Katharina Nesytowa)

Wendland (2023-) (wlw) | ZDF

Kira Engelmann (Paula Kalenberg)

Birthe (?)

Queer Eye Germany (2022) (mlm, nblm, trans) | Netflix

Avi Jakobs

Leni Bolt

Ayan Yuruk

Jan-Henrik Scheper-Stutke

Aljosha Muttardi

Notes: I may have forgotten to add some characters, because for most of the shows it has been some time since I last watched them. Please let me know if you want me to add a character or even show:)

#german#queer#lgbt#TV series#queer representation#lgbt representation#1899 netflix#all you need zdf#barbaren netflix#beat prime video#becoming charlie#blutige anfänger#charite#dark netflix#Deutschland 83#dogs of berlin#dr. klein#druck#eldorado kadewe#how to sell drugs online (fast)#kitz netflix#kudamm 56#deutschland 89#kroatien krimi#loving her zdf#mord mit aussicht#tatort#tatort saarbrücken#tatort berlin#polizeiruf 110

347 notes

·

View notes

Text

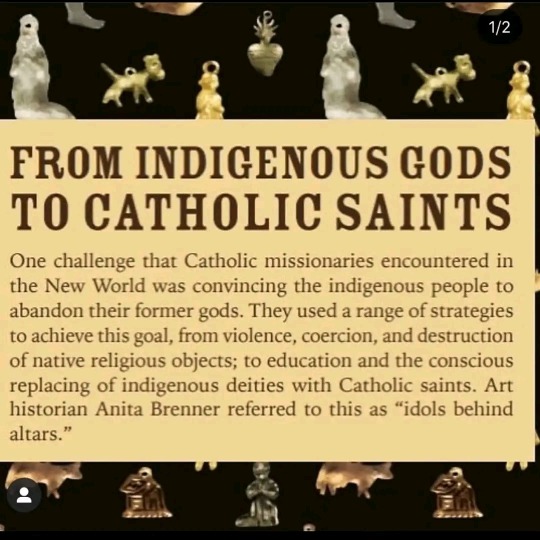

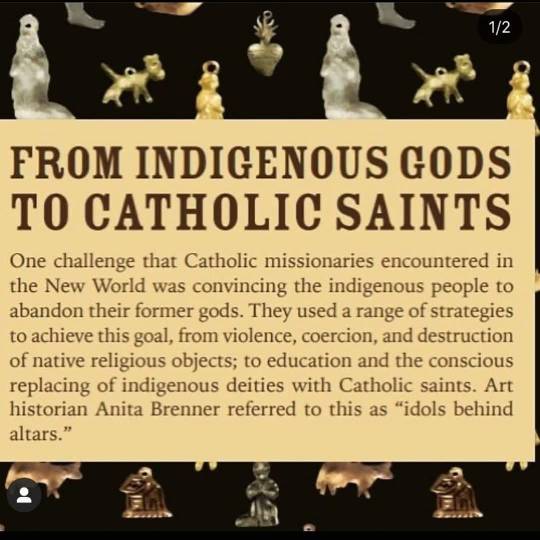

I think it's important to repost. First posted in August 2017 on Art by Women - Women in Arts

fb page: About Anita Brenner

The Revolutionary Mexican-Born, Jewish-American Woman Who Exposed Rivera, Kahlo, and Siqueiros to the World, BY Alan Grabinsky, 08.01.17

"As a journalist, an anthropologist, a cultural promoter and a traveler,

Anita helped position the cultural movement called the Mexican Renaissance in the United States.

Her hybrid identity allowed her to crisscross national boundaries, earning an important role as a type of cultural diplomat."

Orginal post

Anita Brenner (born Hanna Brenner; 13 August 1905 – 1 December 1974) was a transnational Jewish scholar and intellectual,

who wrote extensively in English about the art, culture, and history of Mexico.

She was born in Mexico, raised and educated in the U.S., and returned to Mexico in the 1920s following the Mexican Revolution.

She coined the term 'Mexican Renaissance', "to describe the cultural florescence [that] emerged from the revolution."

As a child of immigrants (Litva), Brenner's heritage caused her to experience both antisemitism and acceptance.

Fleeing discrimination in Texas, she found mentors and colleagues among the European Jewish diaspora living in both Mexico and New York, but Mexico, not the US or Europe, held her loyalty and enduring interest.

She was part of the post-Revolutionary art movement known for its indigenista ideology.

Legacy

Brenner remains an important figure in post-Revolutionary art and history in Mexico, an enthusiast for Mexican art and culture and an active advocate for its importance to a U.S. audience.

A prolific scholar and journalist herself, she has been the subject of studies by Mexicanist scholars.

The Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles plans an exhibition focusing on Brenner in 2017-18, entitled "Another Promised Land: Anita Brenner's Mexico."

.

.

.

#AnitaBrenner #HannaBrenner #herstory #MexicanArt #MexicanHerstory #womeninarts

#Revolutionary #MexicanBorn #JewishAmerican #JewishAmericanWoman #Siqueiros #anthropology #culturescience

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Editorial introductions January 2023: Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension

NOVEL THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES IN NEPHROLOGY AND HYPERTENSION

Editor(s): Barry M Brenner, Ekamol Tantisattamo, Ramy Hanna, Kam Kalantar-Zadeh https://journals.lww.com/co-nephrolhypertens/Fulltext/2023/01000/Editorial_introductions.1.aspx

0 notes

Text

And you thought the Hanna-Barbera Records label had some rather tacky releases ...

Imagine, if you will, the prospect of an album of your favourite Hanna-Barbera characters doing a sampler of classic Broadway musical staples, designed as tribute to Joe Barbera's fondness for the stage and its traditions.

And picture some of the following unlikely possibilities for treatments of classic show tunes:

The Goofy Guards (Yippy, Yappy and Yahooey) doing a cover of "Everything's Coming Up Roses" from Gypsy

Snagglepuss doing Yul Brenner justice with his rendering "A Puzzlement" from The King and I

Andrew Lloyd Webber meets Mike Curb--the Cattanooga Cats bring a folk-rock/country fusion flavour to "Love Changes Everything" from Aspects of Love or "Any Dream Will Do" from Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat

Battle of wits between Penelope Pitstop and Sylvester Sneekly/The Hooded Claw in "Anything You Can Do (I Can Do Better)" from Annie Get Your Gun

Having one of the Laydeez of Hanna-Barbera doing "I Feel Pretty" from West Side Story

Hiw apropos: The Hair Bear Bunch doing the title number from Hair (what else?)

Can you think of a few other Hanna-Barbera characters, gentie reader and Hanna-Barberian, doing justice to the footlights and the floorboards (obviously by way of reblogging)?

#hanna barbera#broadway#great white way#musical theatre#joe barbera#broadway musicals#unlikely albums#unlikely concepts#hannabarberaforever

0 notes

Text

Work -w-

PHRASES

A phrase is a group of words that work together to perform a certain function in a sentence.

A phrase consists of a headword (the word that determines the function of the phrase) and any modifiers.

Phrases can contain other phrases. For example, a noun phrase may contain a prepositional phrase.

Noun Phrases

A noun phrase is a group of words that together function as a noun in a sentence. Noun phrases can go anywhere in a sentence that a single noun can go.

A noun phrase can function as the subject of a sentence.

Sample sentence: The old house on the hill is very large.

A noun phrase can function as the object of a sentence.

Sample sentence: I saw the old house on the hill.

In the sample sentences above, the word house is the headword of each noun phrase. The modifiers include an article (the), an adjective (old), and a prepositional phrase (on the hill).

Verb Phrases

A verb phrase consists of the main verb of a sentence plus any auxiliary verbs.

Sample sentences:

Khaleed might visit his aunt next week.

I have been racing go-karts for two years.

For more information on auxiliary verbs, go to the section on verbs.

Adjectival Phrases

An adjectival phrase is a group of words that together function as an adjective. An adjectival phrase modifies a noun or pronoun.

An adjectival phrase may consist of multiple adjectives.

Sample sentence: Hanna has a big orange cat.

An adjectival phrase may consist of an adjective and one or more modifiers, such as adverbs, adverbial phrases, or prepositional phrases.

Sample sentences:

I am extremely tired.

Tyler is always happy to help.

A participial phrase is an adjectival phrase consisting of a participle and any additional modifiers.

A participial phrase can be formed by using a present participle.

Sample sentence: Striding across the stage, the singer greeted her fans.

A participial phrase can be formed by using a past participle.

Sample sentence: Students interested in engineering should take classes in math and science.

If a participial phrase appears at the beginning of a sentence before the noun it modifies, it is set off from the rest of the sentence with a comma.

Sample sentence: Waving my hands in the air, I tried to get their attention.

If a participial phrase appears in the middle of a sentence, it should be set off by commas only if it is not essential to the meaning of the sentence. If the participial phrase is essential to the meaning of the sentence, it should not be set off by commas.

Sample sentences:

The Hawaiian Islands, formed by volcanoes, are a popular vacation spot.

The girl visiting me this week is my cousin.

For more information on participles, go to the section on participles.

Adverbial Phrases

An adverbial phrase is a group of words that together function as an adverb. An adverbial phrase can modify a verb, an adjective, or an adverb.

An adverbial phrase may consist of multiple adverbs.

Sample sentence: The children sang loudly and joyfully.

An adverbial phrase may consist of an adverb and one or more modifiers.

Sample sentence: Unfortunately for us, our team lost the championship.

Adverbial phrases often explain when, where, or how an action is performed.

Adverbial phrases of time answer the question "when?" Prepositional phrases often function as adverbial phrases of time.

Sample sentence: The ship will set sail in the morning.

Adverbial phrases of place answer the question "where?" Prepositional phrases often function as adverbial phrases of place.

Sample sentence: Karina rode along the bike path.

Adverbial phrases of manner answer the question "how?"

Sample sentences:

He very reluctantly gave up his seat on the train.

The hometown fans cheered more enthusiastically than their rivals.

Natalie cooks like a professional chef.

Prepositional Phrases

A prepositional phrase consists of a preposition, the noun or pronoun that follows the preposition, and any additional modifiers. The noun or pronoun that follows a preposition is called the object of the preposition.

Sample sentences:

Before dinner, we will take a walk.

The flowers in the small glass vase came from my garden.

Prepositional phrases often function as adverbial phrases in a sentence; they indicate when or where the action of a verb was performed.

Sample sentence: I saw Joanie at the museum on Tuesday.

The object of a preposition is never the subject of a sentence. In the following sentence, the word deck is the subject of the sentence, and it agrees with the singular verb is.

Sample sentence: A deck of cards is all you need to perform amazing magic tricks.

For more information on prepositions, go to the section on prepositions.

Appositive Phrases

An appositive is a noun or noun phrase that identifies or describes another noun in a sentence.

An appositive can appear in the beginning, middle, or end of a sentence, but it is always placed next to the noun it modifies.

Sample sentences:

A talented dancer, Nico will be performing with a local ballet company this summer.

The giant squid, a huge sea creature with many tentacles, lives deep in the ocean.

Deliver this note to Ms. Brenner's room, the classroom at the end of the hall.

If an appositive is essential to the meaning of a sentence, it is not set off with commas.

Sample sentence: The writer Maya Angelou received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011.

In the sentence above, the name Maya Angelou is essential information telling the reader who received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Without this information, it would be unclear which writer received the award.

If an appositive is not essential to the meaning of a sentence, it is set off from the rest of the sentence with commas.

Sample sentence: My dog, a three-year-old poodle, always meets me at the door when I get home from school.

Absolute Phrases

An absolute phrase modifies an entire sentence or clause, rather than a specific word. An absolute phrase usually consists of a noun and a participle, plus any additional modifiers.

Sample sentences:

We snuggled into our sleeping bags for the night, stars twinkling overhead.

Their manes decorated with ribbons, the ponies pranced around the ring.

In some absolute phrases, the participle being is implied but not written.

Sample sentences:

His thoughts with his daughter, Mr. Bashara found his seat at the dance recital.

The children laughed, eyes bright, as they watched the clown perform his tricks.

Some absolute phrases use an infinitive instead of a participle.

Sample sentence: The young birds left their nest, some to return quickly, and searched for food.

1 note

·

View note

Text

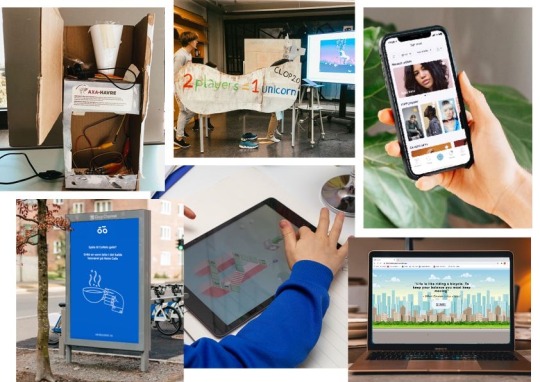

Brief 9: Interaktive læringsmidler

Refleksjon av kurset «interaktive produkter»

Da har vi kommet til enden av dette semesteret. Jeg tror helt ærlig at jeg aldri har lært og fått utforsket så mye forskjellig på så kort tid. Det har vært seks intensive og verdifulle måneder.

Jeg startet semesteret med å knapt vite hva begrepet interaksjon betydde. Jeg var veldig nysjerrig og spent, hadde egentlig ikke noe høye forventninger fordi jeg tenkte at det var noe jeg ikke kommer til å jobbe med uansett. Nå etter seks måneder har alt snudd seg, jeg merker virkelig at jeg brenner for interaksjonsdesign og håper på å kunne jobbe med det i nærmere fremtid.

Dette semesteret jobbet vi blant annet med koblingen mellom menneske og maskin, utarbeide en eksisterende app med en ny interface, kode vår egen nettside, bruke API data og frestille det visuellt, bruke cpx for å utforske elektronikk, jobbe med en eksisterende lego eske og legge til nye interaksjoner og sist men ikke minst lagde vi et digitalt læringsmidel for andre klassinger.

Det er vanskelig å si på hvilket prosjekt jeg lærte mest av fordi alt var så forskjellig. Men føler alikelevel at på Fmm, Lego og Aschehoug prosjektene fikk jeg mest utforsket og lært mest!

På Fmm prosjektet starta vi og lære oss Figma, og det er et verktøy jeg garantert kommer til å bruke fremover! Det var ekstremt gøy å utforske seg frem til forskjellige prototyper og interaksjoner! Det jeg syns var spesielt verdifullt under dette prosjektet var at jeg og @hanna hadde spissa oss inn mot noe og fokuserte kun på strukturering, filtrering og sortering av artistsøk i appen. Da fikk fikk vi tid til å utarbeide det grundig.

På lego prosjektet hadde jeg et ekstremt bra samarbeid med @olafdesign! Selvom vi noen ganger møtte på utfordringer, fant vi fort på en løsning sammen. Det var gøy å jobbe med noe eksisterende og utarbeide det med nye interaktive egenskaper.

Aschehoug prosjektet, som var med @henningnygaard og @hannahhovedesign gikk også veldig bra! Vi klarte å samarbeide og jobbe på hver vår måte. Selvom alle hadde forskjellige meninger kom vi frem til noe sammen og klarte å møtes på midten. Jeg likte veldig godt at vi måtte ha så nær kontakt med brukerene hele veien i prosjektet, det ga oss ny innsikt for hver gang vi itererte.

Det har vært noen intensive, lærerike, motiverende, engasjerende, utfordrende og innholdsrike prosjekter som jeg skal ta med meg videre i studiet!

Vi jobbet ikke bare i prosjekter men vi hadde også noen inspirerende forelesninger og workshops underveis. Jeg tror nok også at de hadde en påvikning på at jeg liker interkasjonsdesign så godt nå, jeg husker hvertfall når hun ene diplom studenten var innom og fortalte om sin studieopplevelse. En ting hun sa var blant annet at vi selvom vi får briefer underveis på studiet må vi huske på å velge hvordan og i hvilken retning vi vil tolke det, det er det som gjør oss til personlige designere og gir oss en sterkere utvikling. Dette er noe jeg skal tenke på videre i studiet.

Da er det over fra meg for denne gang og jeg gleder meg til å jobbe med interkasjons design igjen, om ikke på skolen så vil jeg hvertfall starte opp noen egne prosjekter på siden!

Takk for gode tips og utbytte mellom ulike prosjekteter av alle studenter i klassen og sist men ikke minst en stor takk til alle lærere og studentassistenter som ga så god veiledning og tips underveis.

Vi sees og takk for iår!

0 notes

Photo

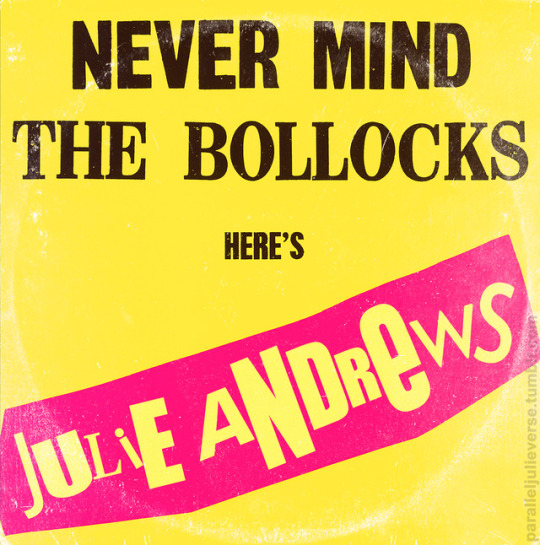

Julie Andrews Fantasy LPs #9

Super-cool-Dame-Julie-sings-the-punk-songs-of-Sid-Vicious!

Even though the sound of it is something quite suspicious,

If you play it loud enough you’ll always sound seditious,

Super-cool-Dame-Julie-sings-the-punk-songs-of-Sid-Vicious!

Um diddle diddle diddle, um diddle oi!

Um diddle diddle diddle, um diddle oi!

____________________________________

When Julie Andrews was honoured with a Special Lifetime Achievement Award at the 53rd Annual Grammys in 2011, media reports took considerable delight in the incongruous sight of the genteel Dame alongside fellow honorees, pioneering US punk band, The Ramones. Photos of Julie sandwiched between Tommy and Marky Ramone, the latter draping his bared, tattooed arm proudly around her shoulder, featured in online and print news stories around the world with commentaries typically drawing amused attention to the “diversity” of the year’s honorees.

Despite the apparent novelty of the odd juxtaposition of “Mary Poppins” and a hardcore punk rock band whose catalogue of hits include numbers like “I Wanna Sniff Some Glue”and “Gimme Gimme Shock Treatment,” there is in fact something of a history of associations between Julie and punk rock.

One of the earliest recorded instances is a parody piece from 1980 by British comedian Mel Smith, made in collaboration with Queen drummer, Roger Taylor. Titled “Mel Smith’s Greatest Hits”, the song is a comic pastiche of the angry male punk anthems of the time with Smith growling about wanting to “jump up and down to my favourite sound...Julie Andrews Greatest Hits.” Elsewhere in the song, he snarls:

Julie drives me frantic

Cos I'm a bit of an old romantic

And she sounds so nice and she's so precise

I'm in paradise with me Edelweiss

Released as a 7″ single, the front sleeve featured cover art of Smith dressed in full Adam Ant-style punk regalia, striking an air guitar pose in the middle of a bedroom bedecked with Julie Andrews memorabilia. The rear sleeve had a similar shot of Smith drooling in mock-lasciviousness over a poster of a beatifically smiling Julie. While clearly tongue-in-cheek, the Smith song signalled an irreverent collocation of Julie and punk culture that would find other, more authentic, expressions as well.

Indeed, in the very same year of 1980, a post-punk experimental outfit “The 49 Americans” released a self-titled EP with a brief track called, simply, “Julie Andrews (A Tribute)” (1980). Engineered by Andrew "Giblet" Brenner, “The 49 Americans” was a collaborative group that developed out of the London Musicians Collective in Camden (Reynolds, 187-188). Inspired by the DIY experimentalism of punk, the group placed a premium on unregulated improvisation with an open, fluid membership and a single rule that players had to swap instruments -- which could be anything from a piano to saucepan lids -- from number to number with the result that they’d often be performing with little or no technical proficiency. The “Julie Andrews” track was allegedly inspired after the group spent an evening watching tapes of Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music and consists of a discordant version of “Do Re Mi” played on a children’s xylophone with non-verbal vocals, (Masters, 112). It was re-released as part of the group’s debut 1982 LP, “Too Young To Be Ideal”, which was honoured in The Wire magazine’s list of “100 Records That Set the World on Fire (While No One Was Listening)” (Barker et al, 1998).

Other examples of Julie references in punk rock include: “Topless Mary Poppins”, recorded in 2004 by London-based Celtic punk group, Neck; the summarily titled “Julie Andrews” by the Liverpool pop-punk outfit, The Down and Outs, released as a limited run single in 2007; and, most recently, a 2017 release also called “Julie Andrews” by Noose, a self-described four piece rock punk band from Nottingham. Sporting lyrics like, “I wished my baby was like the girlies in the porno movies, But it turns out she was just like Julie Andrews from The Sound of Music,” these songs turn on a kind of shock tactic of mixing the sacred and the profane, arguably something of a stylistic signature of punk.

Dick Hebdige (1979) famously theorises punk as a “revolting style” whose subcultural disaffection was expressed through a spectacular “bricolage” of appropriated cultural “signs” (106-112). The disordered cacophony of punk music or the riotous mish-mash of punk fashion effect a representational rebellion of “semantic disorder,” he asserts, wherein categorical boundaries are dissolved and ordinarily discrete elements are thrown together in perverse combinations that contravene received “rules” of taste and decency (90). Like a portrait of the Queen with a safety pin through her lip, the family-friendly wholesomeness of Julie Andrews was a resonant symbol of mainstream culture ripe for punk subversion.

There is however another, possibly more interesting, reading of punk’s incorporation of Julie Andrews as other than a simple target for anti-establishment iconoclasm. In a fascinating article, Ruth Adams (2008) argues for punk, at least in its influential British forms, as part of a long history of populist English cultural dissent. In punk, she writes,“[b]its and pieces of both officially sanctioned and popular English culture, of politics and history were brought together in a chaotic, uneasy admixture...that arguably spot lit the very institutions that it nominally sought to destroy” (469-70). The Sex Pistols, in particular, are interpreted by Adams as “inheritors of the English music hall tradition -- the heirs to the crowns of Arthur Askey and Max Wall, operating outside the ‘legitimate theatre’ and characterized by clownish outfits, silly walks, smutty jokes and cocking a snook at the Establishment” (470).

Far from seeing them as antithetical opposites, this reading places punk and Julie Andrews on something of an artistic continuum -- albeit at divergent extremes -- with both drawing performative and professional energies from the riotous traditions of popular English carnivalesque and working-class musical theatre. Indeed, it’s instructive that the two music hall comics cited by Adams as historical precedents for the Sex Pistols -- Arthur Askey and Max Wall -- actually performed alongside Julie during her long juvenile career on the British variety circuit (Andrews, 150-51). Even after she made the leap to “legit” theatre and Hollywood stardom, the topsy-turvy irreverence of music hall continued to form an integral part of her oeuvre and persona, as evidenced from My Fair Lady to STAR! to Victor/Victoria, from Heartrending Ballads and Raucous Ditties to The Julie Andrews Hour to Julie and Dick at Covent Garden.

It’s possibly for this reason that, alongside the more predictable deployments of Julie as object of punk’s anarchic negationism, she also features as a subject of acknowledged admiration, even inspiration. This seems particularly true of female punk artists, many of whom regularly cite Julie as an important influence. Gina Birch, founding member of post-punk British band, The Raincoats, singles out Julie as a major formative inspiration (Reddington, 27), as does Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill (Juno, 89). In her memoir, Laurie Lindeen (2007), lead vocalist for 1990s grrl punk band, Zuzu’s Petals, even jokes:

“‘What women have influenced you?’ is a very broad question that we are asked every day.

We yawn the usual: ‘Patti Smith, Chrissie Hynde, Deborah Harry, and Exene,’ when I should say, “Louisa May Alcott, Julie Andrews, and Carly Simon’” (202)

Pop superstar, Gwen Stefani, who rose to fame as lead singer of ska-punk band, No Doubt, makes no bones about her lifelong adoration of Julie Andrews. She loudly proclaims The Sound of Music as “her one true love” and is said to have cried with joy when Julie granted permission for her to riff vocals from “The Lonely Goatherd” for the 2007 hit single, “Wind It Up” (Apter, 27). Another current pop superstar, Lady Gaga -- who though not directly punk certainly draws heavily from traditions of punk rock -- is equally fulsome in her enthusiasm for Julie, as profiled in an earlier post here in the Parallel Julieverse.

All of which ultimately suggests that this imaginary LP of Julie singing the songs of the Sex Pistols is possibly not as far-fetched as it might at first seem! Oi!

Sources:

Adams, Ruth, 'The Englishness of English Punk: Sex Pistols, Subcultures, and Nostalgia.” Popular Music and Society. 31: 4 (2008): 469–88.

Andrews, Julie. Home: A Memoir of My Early Years. New York: Hyperion, 2008.

Apter, Jeff. Gwen Stefani and No Doubt: Simple Kind of Life. London: Omnibus Press, 2007.

Barker, Steve et al. “100 Records That Set The World On Fire (While No One Was Listening).” The Wire. 175, September 1998: 22-40.

Hebdige, Dick. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London: Methuen, 1979.

Juno, Andrea, ed. Angry Women in Rock, Vol. 1. San Francisco: Juno Books: 1996.

Lindeen, Laurie. Petal Pusher: A Rock and Roll Cinderella Story. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007.

Masters, Marc. No Wave. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2007.

Reddington, Helen. The Lost Women of Rock Music: Female Musicians of the Punk Era. London: Ashgate, 2007.

Reynold, Simon. Rip it Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984. London: Faber and Faber, 2009.

© 2017, Brett Farmer. All Rights Reserved

#julie andrews#punk rock#post punk#sex pistols#never mind the bollocks#mock lp#julie andrews fantasy lps#the parallel julieverse

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gli invisibili. Cosa vedere al cinema dal 14 febbraio

Gli invisibili. Cosa vedere al cinema dal 14 febbraio

Cosa vedere al cinema dal 14 febbraio? Come ogni settimana arriva la nostra rubrica di cinema poco visibile. Vi segnaliamo e consigliamo i film in sala con una bassa distribuzione, le pellicole poco pubblicizzate che meriterebbero di essere conosciute. Correte a cercarli nella vostra città prima che vengano tolti, oppure se non li trovate, segnateveli per recuperarli in futuro.

Un Valzer tra gli…

View On WordPress

#Adina Pintilie#Andrea Tagliaferri#Andreas Leupold#Annette Bening#Antonio Banderas#Christian Bayerlein#Dan Fogelman#Franz Rogowski#Grit Uhlemann#Hanna Hofmann#Karole Di Tommaso#Laura Benson#Linda Caridi#Mandy Patinkin#Maria Roveran#Matthias Brenner#Olivia Cooke#Olivia Wilde#Oscar Isaac#Peter Kurth#Sandra Hüller#Silvia Gallerano#Stefano Sabelli#Thomas Stuber#Tómas Lemarquis

0 notes

Link

DESPITE MANY OTHER predictable changes to its source material, the opening sequence of Andy Muschietti’s wildly successful adaptation of Stephen King’s epic 1986 novel It reproduces the book’s inciting incident with meticulous loyalty. In the beginning of the novel, just before protagonist Bill Denbrough’s younger brother Georgie is killed by the monstrous clown Pennywise in a horrific realization of “stranger danger,” he must run down to his family’s basement to get paraffin for the newspaper boat Bill is building for him. It is an experience of unrelenting terror, despite his desperate attempts to reassure himself: “Stupid! There were no things with claws, all hairy and full of killing spite. Every now and then someone went crazy and killed a lot of people — sometimes Chet Huntley told about such things on the evening news — and of course there were Commies, but there was no weirdo monster living down in their cellar.” King’s powerful evocation of the nearly unbearable ordeal of a solo trip to the basement at age six reminds us of childhood’s blurred line between real and imagined fears.

For contemporary advocates of “free-range parenting” for whom the 1980s represents the last vestige of freedom before the descent of the helicopter parent, this is precisely why the unattended trip to the basement or the playground is vital: independently navigating those indistinct regions of the real and the imagined should help children learn to better delineate between the two. But the gruesome murder that sets King’s novel in motion sides instead with the logic of a famous quotation from Catch-22: “Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.” Georgie successfully conquers his fear of the basement, only to be dismembered down the street by a version of the very monster he’d convinced himself was only imaginary.

Critics have noted the It movie’s overlap with the hit Netflix series Stranger Things in their apparent celebration of autonomous childhood adventure, a possibility many believe to have vanished with the 1980s in which movie and show are both set. Do the parent-free exploits of the young “Losers’ Club” in King’s novel support the idea that parental overprotectiveness be dismissed as so much needless paranoia? The novel instead explores more complex and troubling questions inaugurated by Georgie’s death: Is the best and bravest way to treat our fears truly to tell ourselves that they don’t exist? Is it actually possible, or even advisable, to try to separate the real from the imagined?

From Michael Chabon’s wistful “The Wilderness of Childhood” to more polemical essays like Hanna Rosin’s “The Overprotected Kid” and Christina Schwarz’s “Leave Those Kids Alone” (both in The Atlantic), a proliferation of recent think pieces has lamented the loss of an American childhood in which unsupervised play and everyday encounters with moderate danger build independence, resilience, and creativity. In these views, today’s highly regulated kids not only lack fortitude but also tragically miss out on the risky fun and adventure of yesteryear’s childhoods.

Some of these pieces suggest that fictions can help today’s postlapsarian children imagine a different world, and remind parents that such a world could exist. One contemporary father watches the Spielberg-authored adventure The Goonies (dir. Richard Donner, 1985) with his children. Their sense of wonder is ignited simply by the image of a group of kids striking out on a quest on their own. “Where are their parents?” the author’s kids demand to know. “How are they allowed to do this?” In a New York Times op-ed titled “The ‘Stranger Things’ School of Parenting,” Anna North argues that the acclaimed television series offers more than a pleasurable nostalgia for 1980s kids’ adventure movies like The Goonies and E.T. North sees in the show a valuable corrective to the “hyper-parenting” approach of today (indeed, she goes so far as to suggest that the show’s villainous Dr. Martin Brenner is the only adult that fits the “helicopter parent” mold): “‘Stranger Things’ is a reminder of a kind of unstructured childhood wandering that — because of all the cellphones, the fear of child molesters, a move toward more involved parenting or a combination of all three — seems less possible than it once was.” Synthesizing the ideas of Rosin, Schwarz, et al., North asks us to view Stranger Things as a model for a loosened approach to parenting that acknowledges the world may hold dangers, but accepts that “bravery needs its own space to grow.”

There is general consensus among these essays that the 1980s marks a turning point away from older childhood freedoms. This characterization adds further poignancy to Stranger Things’s loving evocation of 1983–’84. The years following the 1982 release of Spielberg’s E.T., the movie with the strongest imprint on Stranger Things’s vision of its era, are also seen as the beginning of the end of a world in which such fantasies of childhood could seem grounded in a recognizable reality. In the present, the image of a group of unsupervised kids biking headlong into mystery and adventure can exist only as nostalgic evocation of past fictions. What happened in the 1980s to bring us to this point?

As Rosin explains, a series of child abductions and murders between 1979 and 1981 garnered a new level of media coverage for this type of crime. Perhaps most notoriously, the disappearance in 1979 of six-year-old Etan Patz, walking alone to his school bus in New York City, precipitated the widespread perception of a rise in kidnapping and child molestation. Rosin succinctly summarizes the cultural upshot of this infamous case: “[T]he fear drove a new parenting absolute. Children were never to talk to strangers.” Or walk to school, or anywhere else, alone. Simultaneously, high-profile lawsuits over children’s injuries led to a radical overhaul of playground design according to stringent new safety standards. In the views of some psychologists and educators, the removal of any sense of risk in the experience of play undermines the development of children’s ability to negotiate real-world fear or danger. Rosin describes an evolutionary psychologist’s critical perspective on these cultural shifts in the 1980s: facing moderate fear through unregulated exploration and play inoculates us against greater, more debilitating fears that may otherwise take hold. For Rosin and many other commentators, this inoculation is what we have lost.

Stephen King’s It, written between 1981 and 1985 as the fears and protective responses described by Rosin became culturally entrenched in what she terms “the era of the ubiquitous missing child,” might at first blush seem an opening salvo in defense of the childhood freedoms whose loss is lamented today. Indeed, King’s story of a group of outcast kids who band together to fight a protean monster in the fictional small town of Derry, Maine, in the 1950s was a major influence on the plot and themes of Stranger Things; the show originated in part because its writer-directors were turned down in their bid to helm the film adaptation of It. It is tempting to read King’s novel as a wellspring for the lesson North believes Stranger Things revives for our present moment: sometimes kids need to be left alone to confront monsters themselves, because “it’s only when the parents aren’t watching that a child can become a hero.”

If understood in these terms, as a paean to childhood freedoms, King’s novel makes a particularly bold statement for the time of its release. Just a few years after Etan Patz’s abduction cemented the rule against talking to strangers, It’s opening scene and inciting incident finds a boy exactly Etan’s age playing out in the street on his own. Lured to the edge of a storm drain by the seductive banter of Pennywise, Georgie hesitates, reciting the dictum actually much less ingrained in the 1950s of the book’s setting than in the 1980s of its writing: “I’m not supposed to take stuff from strangers. My dad said so.” And in this scene King makes it very clear that Georgie invites his own violent demise by eventually trusting the charming Pennywise and accepting his proffered balloon. If Georgie had run away when he first heard the voice coming from the storm drain, there might never have been occasion for Georgie’s older brother and his band of misfit friends to become heroes.

Stranger Things is King by way of Spielberg: It transferred to a 1980s of risk and wonder in which we never really fear for the main characters’ lives. Season one, after all, begins with a missing child, but unlike It, ends with that child’s safe return. Where the four boys of Stranger Things navigate pubescent romantic crushes and perils, King’s children confront actual sex and death. Georgie’s murder comes amid a wave of child disappearances and deaths in Derry that leads the police to impose an evening curfew. At an assembly, the police chief assures the town’s children that they will be safe so long as they never talk to (or accept rides from) strangers. Townspeople speculate about the presence of one or more sexual predators. The death count rises. 1950s Derry becomes a microcosm of “the era of the ubiquitous missing child” Rosin ascribes to the 1980s United States. And, like the science fiction plot cliché in which a character travels back in time to change the future, It’s 1950s imagines an opportunity to confront the fears of the 1980s in advance, before they become insurmountable.

This projection of 1980s anxieties backward to the 1950s is mirrored in the book’s dual time frame: the characters, grown to adulthood in the 1980s, must return to Derry to again confront the monster they thought they had defeated as children. Riding on the coat tails of its own imitator, Stranger Things, the 2017 It movie transfers the children’s story to a more marketable and mediagenic 1980s setting. This only renders its allegory for 1980s panic over missing children more palpable: here is the moment when kidnappings and murders suffuse the adult imagination, but children may still, for just a bit longer, ride their bikes across town alone. Though more horrific than Stranger Things, the It movie aligns with the TV show in lending itself to the view that the dangers the children face are a necessary and bearable price for the joys and glories of their adventures. Both texts can easily support Rosin’s and North’s claims that with increasingly supervised childhoods, kids — and we, as a society — have lost much more than we have gained.

The show and movie can resonate with this message in part because a central argument in most essays on the loss of childhood freedom is that the fears of the 1980s were imaginary all along. The authors of these pieces repeatedly invoke statistics to demonstrate that the rate of stranger abductions did not actually rise during the period in which fear of this act rose exponentially. Nor have they risen since then, and the overall rate of crimes against children has in fact declined since the 1990s. But for me, this common argument calls to mind a Jay Leno routine about how, after every spectacular disaster, the airline industry seeks to reassure the public with statistics. You are a thousand times more likely, authoritative pilots tell us in television spots, to die from a fall in the shower than in a plane crash. Fine, Leno says, but when I slip in the tub I’m not falling 30 thousand feet! Probabilities mean little to fear and horror. It is enough that the thing really exists. And this is what makes King’s novel resistant to being marshaled along with its movie adaptation and Stranger Things in the case for unsupervised childhood. The monster in It assumes many forms as it appears to each of the kids individually. But there is one consistent principle in its manifestations: “It” asserts the brutal reality of particular fears the children already hold but assume are only imaginary.

King emphasizes this point repeatedly: the unsupervised spaces of play and exploration in the novel’s small-town 1950s are sites of self-discovery and growth yet also of terror and violence. And this violence is enacted by a monster whose particular horror derives from its very insistence that fears are never just imagined. Significantly, King invokes horror fictions themselves in this logic: the monster sometimes appears in the form of figures from 1950s horror movies that the children have previously experienced as fun and cathartic entertainments — as a means of safely facing their fears. But It’s manifestations of the Wolfman, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, and so on, are far more grotesque and deadly than the fictions familiar to both the novel’s characters and the reader. Some children are violently murdered. Others escape It’s assaults, eventually banding together to fight back.

Despite firsthand experience of the monster, a major obstacle they must overcome is the ingrained belief that it cannot actually be real:

“You’re … not … real,” Eddie choked, but clouds of grayness were closing in now, and he realized faintly that it was real enough, this Creature. It was, after all, killing him. And yet some rationality remained, even until the end: as the Creature hooked its claws into the soft meat of his neck […] Eddie’s hands groped at the Creature’s back, feeling for a zipper.

This scene, in which minor character Eddie Corcoran is murdered in a town park by It’s version of the Creature from the Black Lagoon, exemplifies a central theme in the novel: although we may rationalize our fears as unbelievable, even ludicrous (a clown in the sewer? a man-sized fish creature?), this doesn’t change the fact that the most unimaginable things do actually happen.

Published at the peak of the “era of the ubiquitous missing child,” It offers a less reassuring message than North’s takeaway from Stranger Things, a bromide equally applicable to the It movie: “it’s only when the parents aren’t watching that a child can become a hero.” There is some of that celebration of heroism in King’s novel, for sure. But in at least equal measure, the book troubles the rationalization that fear is just in our heads. Even if stranger abduction is about as probable as a supernatural killer clown in a storm drain, the book turns the reassurances of probability on their head. What matters isn’t the statistical likelihood of these things happening, but the horrific magnitude of the things that sometimes do happen. It requires the passage of an entire generation for the novel’s characters to even begin to cope with what happened to Georgie and the others. And so, the novel proleptically answers today’s unsupervised childhood nostalgists with a challenging question: why shouldn’t it change everything when a six-year-old child is stolen by a monster?

I am not proposing an alternative to Anna North, an “It School of Parenting” predicated on the belief that Georgie should simply have stayed in his parents’ sight at all times. But nor should the portrait of childhood in the novel that inspired Stranger Things be assimilated to the romantic idealization of childhood before “the era of the ubiquitous missing child.” As Joshua Rothman reminds us in a recent New Yorker piece on It, the movie is unable to capture the novel’s vast, messy weirdness — the cosmic fever dream to which its conflicts eventually build. Indeed, the bizarre incoherence of the book’s resolution further illuminates its status as a missive from the trenches of the missing child era: the book’s inciting incident powerfully conveys the horror of real-life events, but its allegory becomes unruly — and eventually unmoored from its historical referents entirely — in its attempt to imagine what it might take to overcome the fears these events bring into the world.

¤

Jason Middleton is a professor of film and media studies at the University of Rochester.

The post Free-Range Horror appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://ift.tt/2C1WiNS

0 notes

Text

5 livros de Psicanálise

5 livros de Psicanálise

Livros recomendados:

– Noções básicas de psicanálise: introdução à psicologia psicanalítica (Charles Brenner)

– Psicanálise da criança: teoria e técnica (Arminda Aberastury)

– Introdução à obra de Melanie Klein (Hanna Segal)

– Fundamentos psicanalíticos: teoria, técnica e clínica (David E. Zimerman)

– Vocabulário contemporâneo de psicanálise (David E. Zimerman)

– Psicoterapia de orientação…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Gionata I.: 08.07.2017 - Brenner/Torbole

Der Wecker klingelt um 6.15 Uhr am Morgen und die Vorfreude, die sich gestern im Lauf des Tages durch die Vorbereitungen gesteigert hat, weckt mich sofort. Eigentlich ist die Idee recht früh loszufahren, aber die Müdigkeit lässt den Fahrer nicht aufstehen und ermöglicht mir dadurch ein stressfreies Verabschieden von Mama und Papa. ❤️ Nachdem Julian und ich frühstücken verstauen wir die letzten Dinge und der Kühlschrank wird nach einigen nervenaufreibenden Minuten angeschmissen. Es geht los! Um 10:32 schau ich beim Auffahren auf die Autobahn auf die Uhr. 2 Stunden später erreichen wir München (wo wir uns dezent verfahren, hehe). Erst beim Vigettenkauf machen wir eine kurze Pause und genießen die Aussicht. Mir gefällt es wahnsinnig gut durch die Alpen und Nordtirol zu fahren. In Innsbruck wird der letzte günstige Sprit getankt. Das alte Wohnmobil gefällt mir immer mehr und ich fühl mich schon richtig wohl auf meinem Platz. Trotzdem frage ich mich, ob wir auf dieser Reise auch wieder so viele Probleme mit irgendwelchen technischen Dingen bekommen. Wie heraufbeschworen zieht das WoMo nach dem Tanken kaum und wir müssen am Standstreifen halten. Julian schüttet Öl nach und schon fährt das WoMo wieder einwandfrei. Um eine stressfreie Fahrt vorzubeugen passiert dieses tolle Ereignis noch einmal, sodass wir überlegen müssen in Nordtirol zu schlafen, um eine Werkstatt aufzusuchen. Nachdem Julian doch fast einen Liter Öl nachlegt ist das Problem glücklicherweise wieder vergessen. Wir sind jetzt in Italien und werden mit einem schönen Ausblick belohnt. Sehr schön bei den Dolomiten und auch ganz oben an der Grenze (es erinnert mich hier ein bisschen an Bali mit den "Stufenfeldern"). Auch als wir uns unserem Ziel (um kurz vor 9) - Tolerone, nördlich am Gardasee - nähern geht gerade die Sonne unter und präsentiert den See sehr schön! Mit der Stellplatzsuche haben wir beim zweiten Versuch Glück und errichten wir unser Haus nah am See. In den springen wir nachts, um uns abzukühlen. Ich falle müde ins Bett und schlafe überraschenderweise richtig gut! Zur Fahrt: Stau hatten wir ab München eine Weile, aber sonst ging die Fahrt ganz gut. Wir hatten unseren Spaß mit viel Musik und dummen, aber ernst gemeinten Bemerkungen wie "Wofür steht LT?"-"Äh Lichtenau" (Julian); "Nein, das ist kein Schweizer, das sind Australier (wegen dem Kennzeichen A)!" (Hanna)

0 notes

Text

I think it's important to repost. First posted in August 2017 on Art by Women - Women in Arts

fb page: About Anita Brenner

The Revolutionary Mexican-Born, Jewish-American Woman Who Exposed Rivera, Kahlo, and Siqueiros to the World, BY Alan Grabinsky, 08.01.17

"As a journalist, an anthropologist, a cultural promoter and a traveler,

Anita helped position the cultural movement called the Mexican Renaissance in the United States.

Her hybrid identity allowed her to crisscross national boundaries, earning an important role as a type of cultural diplomat."

Orginal post: https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=1936174399984109&id=1767592126842338

Anita Brenner (born Hanna Brenner; 13 August 1905 – 1 December 1974) was a transnational Jewish scholar and intellectual,

who wrote extensively in English about the art, culture, and history of Mexico.

She was born in Mexico, raised and educated in the U.S., and returned to Mexico in the 1920s following the Mexican Revolution.

She coined the term 'Mexican Renaissance', "to describe the cultural florescence [that] emerged from the revolution."

As a child of immigrants (Litva), Brenner's heritage caused her to experience both antisemitism and acceptance.

Fleeing discrimination in Texas, she found mentors and colleagues among the European Jewish diaspora living in both Mexico and New York, but Mexico, not the US or Europe, held her loyalty and enduring interest.

She was part of the post-Revolutionary art movement known for its indigenista ideology.

Legacy

Brenner remains an important figure in post-Revolutionary art and history in Mexico, an enthusiast for Mexican art and culture and an active advocate for its importance to a U.S. audience.

A prolific scholar and journalist herself, she has been the subject of studies by Mexicanist scholars.

The Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles plans an exhibition focusing on Brenner in 2017-18, entitled "Another Promised Land: Anita Brenner's Mexico."

.

.

.

#AnitaBrenner #HannaBrenner #herstory #MexicanArt #MexicanHerstory #womeninarts

#Revolutionary #MexicanBorn #JewishAmerican #JewishAmericanWoman #Siqueiros #anthropology #culturescience

0 notes

Text

5 livros de Psicanálise

5 livros de Psicanálise

Livros recomendados:

– Noções básicas de psicanálise: introdução à psicologia psicanalítica (Charles Brenner)

– Psicanálise da criança: teoria e técnica (Arminda Aberastury)

– Introdução à obra de Melanie Klein (Hanna Segal)

– Fundamentos psicanalíticos: teoria, técnica e clínica (David E. Zimerman)

– Vocabulário contemporâneo de…

View On WordPress

0 notes