#grieving what we could have had (uther dead by season two)

Text

jesus can always reject his father

but he cannot escape his mother blood

he’ll laugh and say, you know i raised you better than this

then leave me hanging so they all can laugh at me

#arthur pendragon#uther pendragon#bbc merlin#grieving what we could have had (uther dead by season two)#i cannot make characters analysis#but i can make songs associations so spot on trust me#anyway fuck uther i hate him w a burning passion#uther loved his children and uther was an abusive neglecting asshole are two sentences that coexist#however i need him to suffer anyway#put me in bbc merlin and i’ll deal w it trust🗣️

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Folkloristics of Supernatural

So. Something interesting is happening in Season 14. I suspected that it was coming when they revealed in 12 that Jack’s name would be Jack. Jack as in “the Giant Killer” Jack. Jack like “Jack Tales.” Jack from all of the “Jack and the Devil” stories. This Jack. But Dabb is running a long mytharc, so last season was the set-up for this season-- priming the pump, if you will, for what the writers are doing now, and it came to fruition in the first few episodes.

As I said before, we got a hint of this theme in Jack’s name as well as in the way the season wrapped up with grieving Dean and Dead!Cas mirroring the last scene of despairing Cas and Possessed!Dean. Folklore brings with it the other thematic elements we’ve seen so far-- mirrors (oh my god the mirrors,) recursion and repetition, callbacks, sleep, and sleep-like death.

But why folklore *in particular*? And how is “folklore” as a theme in seasons 13 and 14 any different from the fact that this is a show *based* on folk tales?

This season, the writers are not only telling stories drawn from folklore, they are using folklore and folkloristics (the academic discipline) as a theme.

Andrew Dabb wrote a formulaic tale into the premiere, and I flipped my lid. A formula tale is one that relies on a set structure, such as the tale of Henny Penny, The Little Red Hen, or the Fisherman and his Wife, where challenges or episodes are repeated over and over until all the possibilities are exhausted or something breaks the chain. The story of Michael’s quest is a tale that relies on formula as well as on the structure of a “rule of three,” or two challenges that fail and one that succeeds. He asked a human and an angel what they wanted, before finding a monster whose desires he considered purest. Compare that structure to Goldilocks and the Three Bears, or The Three Little Pigs. I have a much more in-depth analysis of the “rule of three” that I will post later. This and other “folklore” elements in the next three episodes established this as an official “Thing on the Show.”

For now and for those of you new to the idea of the study of folklore, I’ll summarize the history of the academic discipline of folkloristics.

More than six hundred years ago, in post-Renaissance Europe, concerned scholars and bored aristocrats started doing something strange.

They started collecting folk stories from the lower classes.

This was strange because the disdain that the “upper class” (which included not just nobility and gentry but clergy and those squirrely scholars as well) felt for the emerging middle class and the peasantry can not be overstated. But perhaps because they were fascinated with that which they looked down upon, many learned men and women during the Age of Enlightenment began to study folkways and oral tales.

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, “fairy tales,” “wonder tales,” “Märchen,” and “Mother Goose” stories lit up courts (and later salons) all over Europe. People recorded them from a handy peasant, wrote them down with a judicious application of upper-class refinements, and later crafted original stories inspired by them. There are works that were preserved from an oral version, like Giambattista Basile’s “Sun, Moon, and Talia” (which is based on a Neapolitan folk tale but is considered a literary work rather than a transcription and if you read a faithful translation you’d get why that is, he very much polished it with literary allusions and asides) as well as those found in Grimms’ first edition (1812) of collected oral stories which included the bloody version of “Little Red Riding Hood,” then there are folk tales that were cleaned up and sanitized for your comfort, like every Grimm edition since that one, ha ha, and at last there are “literary” fairy tales, or stories that are “original content” but were constructed on a folkish scaffolding like, Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid” and Oscar Wilde’s “The Nightingale and the Rose.” Authors still use fairy tales to inform and inspire-- Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling edited several anthologies of contemporary fairy tales or retellings of old tales by modern authors, beginning with Snow White, Rose Red in 1993 and ending in 2000 with Black Heart, Ivory Bones which, if you enjoy trope subversion and walking around for days bearing a lingering sense of disquiet, are seriously worth reading.

While the Grimms’ work in collecting German folk tales is considered the “watershed” moment for European folk studies (the Chinese, in contrast, have been archiving oral poetry and stories for thousands of years and Arab Muslim scholars may have started collecting folk tales as early as the 10th century CE,) it wasn’t until about a hundred years had passed from the Grimms’ first publication that the discipline took a distinctly scientific turn.

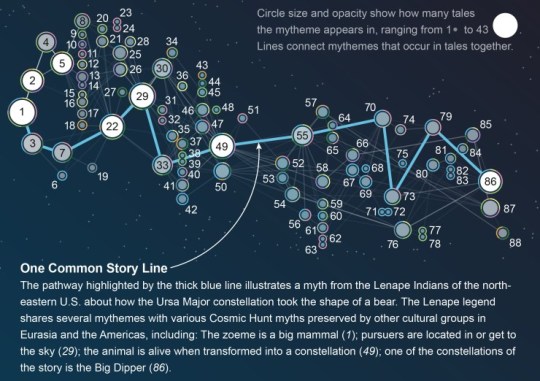

In 1910, a Finnish folklorist named Artti Aarne published a work entitled ‘Verzeichnis der Märchentypen,” or “Types of Folktales.” He had analyzed his own extensive collection of Scandinavian folk stories and realized that these tales often shared the same plots and elements—helpful animals, daring rescues, clever wives, and more-- albeit in different configurations. He broke the stories down to their essential components-- decoded their DNA, if you will-- and asserted that these story elements were used like beads on a string to construct a myriad of tales. He called these elements “Motive,” or motifs. In 1960, an American anthropologist named Stith Thompson translated Aarne’s work from the German and expanded upon it to include stories from a broader European sampling as well as Native American traditions. This became known as the Aarne-Thompson Motif Index. It is one cog in a larger academic movement during the 50’s and 60’s wherein researchers of all stripes endeavored to unearth the earliest roots of mankind—from the search for fossils of the earliest hominids, to tracing the very first languages, to reconstituting the ur-myths that shaped human culture. Academics and field researchers were determined to pinpoint the moment in time when we became more than just a bipedal primate (if we ever even have.) The Index revolutionized folkloristics as anthropologists and other scholars realized that they could trace these story motifs through time and across geography the way linguists were already doing with sounds and words to compile Proto-Indo-European, the language of Neolithic humans who settled India and Europe, and how geneticists today can trace human migrations out of Africa by studying human genomes.

The Index is a taxonomic classification system, like meteorology or the Dewey Decimal System. There are twenty-six parent categories, with subcategories and more subcategories. The Motif Index is organized alphabetically from A-Mythological Motifs (like creation myths) to Z-Miscellaneous Motifs (such as “Z210: Brothers as Heroes.”) There is an adjacent Index of Tale Types, as well, which works similarly. In the Tale Types Index, for instance, “Tales of Magic” comprise subcategories 300 to 799; one subcategory in “Tales of Magic” is “Supernatural or Enchanted Relatives,” which covers tale types 400-459. Tale type number AT 410 is “Sleeping Beauty.” The Basile tale “Sun, Moon, and Talia,” “Sleeping Beauty in the Woods” by Charles Perrault, as well as Grimms’ “Little Briar Rose” fall under this category. The two indices operate in tandem-- for instance, the Basile story and the tale collected by the Grimm brothers are the same kind of story, but they have unique motifs. Both Perrault’s princess and the German Briar Rose are the subjects of a dire prophecy-- motif M340-- and fall into a magic sleep, which is motif D1960. Other motifs are not shared among all three stories, like cannibalism. Yeah, that story is buck wild once you go back a few generations.

Anyway, in 2004, the Aarne-Thompson Tale Type Index was once again revised, this time by German scholar Hans-Jörg Uther, in an attempt to make the index more inclusive of other global folk traditions, and it was renamed the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Classification of Folktales.

The quest to uncover the proto-stories of our ancestors continues in this very decade in the work of Julien d’Huy, who uses computer modeling to make “phylogenetic maps” of stories from around the globe. He can then create diagrams of a universal story-- for instance the “Cosmic Hunt” (D’Huy 2014).

You can also see the concept of the AT motif index in computer-generated novels and scripts, which are “written” by AIs who have ingested and digested and then assimilated whatever weird-ass shit their creators feed it and from that we get gems like “There is more Italy than necessary” from an AI-scripted Olive-Garden commercial.

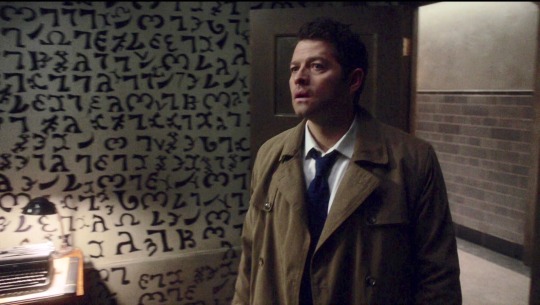

The website TV Tropes works very much like the motif index, although in a much less taxonomic fashion—for instance, one trope they describe is “Room Full of Crazy,” a “motif” if you will that tv writers often use as a way of indicating quickly to the audience that a character is off their rocker (or at least obsessive to the point of near-insanity) by showing them writing or drawing something over and over in a notebook, on their bodies, on walls, etc. Supernatural used this recently to let us know how very messed up Gabriel was after his time with Assmodeus in season 13 “Bring ‘Em Back Alive.”

But it is important to remember that Kripke has used this exact trope before, in “I Know What You Did Last Summer” to let us know that Anna was having visions and hearing what would later be known as “Angel Radio.”

To some extent, Room Full of Crazy was also used all the way back in season one in “Dead in the Water” to represent the little boy’s repressed trauma.

The repetition of tropes (or callbacks) that have already been used earlier in the series is another signal that telegraphed this shift into the realm of folk tales and mythology in a thematic sense.

Yes, Supernatural has always been about folk tales and myth. Native American stories like that of the wendigo, urban folklore like the story of the hook man and other perils of “parking,” shtrigas, skinwalkers, etc, have served as both monsters-of-the-week and Big Bads. The premise of the show draws, pishtaco-like, from world stories to survive. But we’re going to dig down and find not just the fairy tales of season 14, but the tale types and the motifs and discover what this kind of focused close-reading can tell us about this season’s values.

Lots of people point out that the Index is dry and strips away so much that you could literally tell a story just by listing the motifs in order (this comment from my folklore prof many, many years ago when we got into the motif index in class.) But that is not at all how the originators intended the index to be used. If anything, as evidenced by the “phenogenetic” tale typing of d’Huy, the presence of a folktale motif is more powerful than any literary allusion or pop-culture reference. If you realize that you’re watching a story that involves a “beat the Devil” premise, and you’ve read some of those tales, they should all light up like a constellation in your memory. You might even mentally replay the electric guitar riff from Charlie Daniels’ “The Devil Went Down to Georgia.” When we learned that the nephilim was going to be named Jack, and that his mother was hanging all of her hopes on him, you may have subconsciously thought of Jack and the Beanstalk or other Jack tales and made a prediction about the kind of story that we might see Jack feature in*. All the protagonists, all the challenges, all the outcomes of those stories will spread like beacons across a plain-- which is what comparative literature is all about in the first place. It is less about reducing a story to its DNA and more about finding that story’s family tree. And writers like Jane Yolen and the aforementioned Datlow and Windling use these bits of stories to write new ones. Oh and writers like Mr. Andrew Dabb, who used a most familiar formula (to his American audience at least) to start out the season. It’s wild, y’all.

So welcome to the folkloristics of Supernatural. As my favorite professor used to say, are there any thoughts, questions, miscellaneous abuse? My asks are open.

Here’s to a fantastic mideseason.

*allusion is not allegory, meaning you bring in an allusion to another text for depth; if you want to retell the story of Jesus and Christianity you write the Narnia Chronicles. However. Just because Jack was not the one to kill Lucifer does not mean Lucifer’s death was not foretold… the point of retelling these stories in a literary setting is to find the other values that the story can reveal, or to take a trope and twist it to reveal something that had not previously been considered.

Caveat: I’m NOT a prophet. None of us meta writers are. Nothing is stopping anyone involved in the show from making a decision that runs contrary to the story’s architecture, and it’s even been done before. I even have a post about trying to predict from the subtext or even text of a serial publication, like a tv series, that I’ll fit into this series. But anyway, use these posts to “prove” that destiel will be going canon at your own peril. And also I won’t be focusing only on “destiel” subtext. There’s stuff in these episodes for everyone, it’s chock full o’ nuts.

ALSO I have been deliberately staying away from a lot of meta while I compiled this, so if there’s more going on along these lines please feel free to tag me in :)

#the folklore of supernatural#folklore meta series#introductory post#the folkloristics of supernatural#spn meta

115 notes

·

View notes