#globalization

Text

I found some “Bones reacting to our century“ doodles I've completely forgot!

#Star trek#leonard mccoy#Bones#Socialism#Health care#Social security#Stoopid 21 century#Globalization#Capitalism#Dumb doodles#Fanart

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝗠𝝠𝗗 𝗣𝝠𝗡𝗗𝝠 𝗪𝗜𝗦𝗗𝝝𝝝𝗠 🐼 🏴☠️

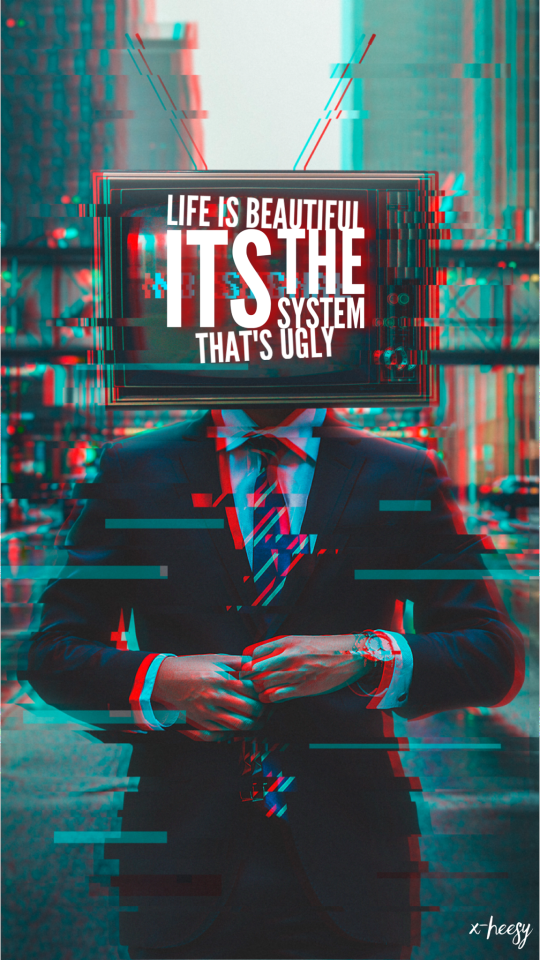

Life is BeAutiful: ITS THE SYSTEM THAT'S UGLY

𝗠𝝝𝝝𝗗 𝗕𝝝𝝠𝗥𝗗 / 𝗦𝗘𝗫𝗗𝗥𝗨𝗚𝗦𝝠𝗡𝗗𝗦𝝝𝗖𝗞𝗦𝗪𝗜𝗧𝗛𝗛𝝝𝗟𝗘𝗦 / 𝗣𝗨𝗡𝗞𝗦𝝠𝗥𝗘𝗡𝗧𝗗𝗘𝝠𝗗 / 𝗟𝝝𝗩𝗘 & 𝗟𝗘𝗧 𝗟𝝝𝗩𝗘 / 𝗟𝗜𝗩𝗘 & 𝗟𝗘𝗧 𝗟𝗜𝗩𝗘 / 𝗞𝗘𝗘𝗣 𝗜𝗧 𝗦𝗜𝗠𝗣𝗟𝗘 𝗞𝗘𝗘𝗣 𝗜𝗧 𝗥𝗘𝝠𝗟 / 𝗡𝝝 𝗚𝝝𝗗𝗦 𝗡𝝝 𝗠𝝠𝗦𝗧𝗘𝗥𝗦 / 𝗣𝗥𝝝 𝗟𝗜𝗙𝗘 𝗠𝗙𝗭 / 𝗣𝗛𝗨𝗖𝗞 𝗧𝗛𝝠 𝗦𝗬𝗦𝗧𝗘𝗠 / 𝗙𝗟𝗨𝗙𝗙 𝗬𝝝𝗨, 𝗬𝝝𝗨 𝗙𝗟𝗨𝗙𝗙𝗜𝗡 𝗙𝗟𝗨𝗙𝗙 / 𝗜 𝗗𝝝𝗡’𝗧 𝗚𝗜𝗩𝗘 𝝠 𝗣𝗛𝗨𝗖𝗞 / 𝗣𝗛𝗨𝗖𝗞𝗜𝗧𝟰𝗣𝗛𝗨𝗡 / 𝝠𝗡𝗗𝗥𝝝𝗜𝗗𝝝𝗚𝗥𝝠𝗣𝗛𝗬 / 𝗙𝝝𝝝𝗟𝗜𝗡𝗚𝝠𝗥𝝝𝗨𝗡𝗗 / 𝗧𝗥𝝠𝗦𝗛𝗠𝗘 / 𝗧𝗥𝝠𝗦𝗛𝗖𝝝𝗥𝗘 / 𝗘𝗘𝗞 𝗣𝗘𝝝𝗣𝗟𝗘 / 𝗕𝝠𝗟𝗖𝝝𝗡𝗬𝝠𝗥𝗧/ 𝗘𝗡𝗘𝗥𝗚𝗬𝗦𝗨𝗖𝗞𝗘𝗥𝗭 𝗡𝝝𝗧 𝗪𝗘𝗟(𝗟) 𝗖𝗨𝗠

#photoart #photoartist #photoartwork #photoartistic #photoarts #blissfulphotoart #photoartistique #photoarte #photoartistry #contemporaryphotoart #photoartists #photoarty #photoartgallery #photoartmag #nyphotoart @frenchpsychiatrymuderedmycnut #photoartcrew #photoartspirit #photoartgram #urbanphotoart #darkphotoart #photooftheday #photographylovers #aesthetic #photographylover #ilovephotography #instaphotography #photographyart

Tweet Tweet Tweet by Sleaford Mods 🎧

#Punks aren’t dead#x-heesy#my art#artists on tumblr#8/2023#where are my hashtags fuckaz#wisdoom#our whole system is very very wrong 😑#text art#typography#artful quotes#fucking favorite#pro life mfz#question everything#rise rebel resist#capitalism#globalization#pop art#neo pop art#fuck the system#newcontemporary#new contemporary#new contemporary art#music and art#contemporaryart

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

On an international side note, I believe the denial regarding the genocide in Palestine is encouraging negationist speech all over the world.

Facists everywhere have learned they can deny one genocide and get away with it, so now they are applying that lesson in their local contexts.

#if denying one happening in front of our eyes is so easy for them#it's logical they will assume they can easily rewrite the history of their countries#tw: negationist speech#genocide#globalization#imperialism#free palestine

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The contradictions of China-bashing in the United States begin with how often it is flat-out untrue.

The Wall Street Journal reports that the “Chinese spy” balloon that President Joe Biden shot down with immense patriotic fanfare in February did not in fact transmit pictures or anything else to China.

White House economists have been trying to excuse persistent US inflation saying it is a global problem and inflation is worse elsewhere in the world. China’s inflation rate is 0.7% year on year.

Financial media outlets stress how China’s GDP growth rate is lower than it used to be. China now estimates that its 2023 GDP growth will be 5-5.5%. Estimates for the US GDP growth rate in 2023, meanwhile, vacillate around 1-2%.

China-bashing has intensified into denial and self-delusion – it is akin to pretending that the United States did not lose wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq and more.

The BRICS coalition (China and its allies) now has a significantly larger global economic footprint (higher total GDP) than the Group of Seven (the United States and its allies).

China is outgrowing the rest of the world in research and development expenditures.

The American empire (like its foundation, American capitalism) is not the dominating global force it once was right after World War II. The empire and the economy have shrunk in size, power and influence considerably since then. And they continue to do so.

Putting that genie back into the bottle is a battle against history that the United States is not likely to win.

The Russia delusion

Denial and self-delusion about the changing world economy have led to major strategic mistakes. US leaders predicted before and shortly after February 2022, when the Ukraine war began, for example, that Russia’s economy would crash from the effects of the “greatest of all sanctions,” led by the United States. Some US leaders still believe that the crash will take place (publicly, if not privately) despite there being no such indication.

Such predictions badly miscalculated the economic strength and potential of Russia’s allies in the BRICS. Led by China and India, the BRICS nations responded to Russia’s need for buyers of its oil and gas.

The United States made its European allies cut off purchasing Russian oil and gas as part of the sanctions war against the Kremlin over Ukraine. However, US pressure tactics used on China, India, and many other nations (inside and outside BRICS) likewise to stop buying Russian exports failed. They not only purchased oil and gas from Russia but then also re-exported some of it to European nations.

World power configurations had followed the changes in the world economy at the expense of the US position.

The military delusion

War games with allies, threats from US officials, and US warships off China’s coast may delude some to imagine that these moves intimidate China. The reality is that the military disparity between China and the United States is smaller now than it has ever been in modern China’s history.

China’s military alliances are the strongest they have ever been. Intimidation that did not work from the time of the Korean War and since then will certainly not be effective now.

Former president Donald Trump’s tariff and trade wars were meang, US officials said, to persuade China to change its “authoritarian” economic system. If so, that aim was not achieved. The United States simply lacks the power to force the matter.

American polls suggest that media outlets have been successful in a) portraying China’s advances economically and technologically as a threat, and b) using that threat to lobby against regulations of US high-tech industries.

The tech delusion

Of course, business opposition to government regulation predates China’s emergence. However, encouraging hostility toward China provides convenient additional cover for all sorts of business interests.

China’s technological challenge flows from and depends on a massive educational effort based on training far more STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) students than the United States does. Yet US business does not support paying taxes to fund education equivalently.

The reporting by the media on this issue rarely covers that obvious contradiction and politicians mostly avoid it as dangerous to their electoral prospects.

Scapegoating China joins with scapegoating immigrants, BIPOCs (black and Indigenous people of color), and many of the other usual targets.

The broader decline of the US empire and capitalist economic system confronts the nation with the stark question: Whose standard of living will bear the burden of the impact of this decline? The answer to that question has been crystal clear: The US government will pursue austerity policies (cut vital public services) and will allow price inflation and then rising interest rates that reduce living standards and jobs.

Coming on top of 2020’s combined economic crash and Covid-19 pandemic, the middle- and-lower-income majority have so far borne most of the cost of the United States’ decline. That has been the pattern followed by declining empires throughout human history: Those who control wealth and power are best positioned to offload the costs of decline on to the general population.

The real sufferings of that population cause vulnerability to the political agendas of demagogues. They offer scapegoats to offset popular upset, bitterness and anger.

Leading capitalists and the politicians they own welcome or tolerate scapegoating as a distraction from those leaders’ responsibilities for mass suffering. Demagogic leaders scapegoat old and new targets: immigrants, BIPOCs, women, socialists, liberals, minorities of various kinds, and foreign threats.

The scapegoating usually does little more than hurt its intended victims. Its failure to solve any real problem keeps that problem alive and available for demagogues to exploit at a later stage (at least until scapegoating’s victims resist enough to end it).

The contradictions of scapegoating include the dangerous risk that it overflows its original purposes and causes capitalism more problems than it relieves.

If anti-immigrant agitation actually slows or stops immigration (as has happened recently in the United States), domestic labor shortages may appear or worsen, which may drive up wages, and thereby hurt profits.

If racism similarly leads to disruptive civil disturbances (as has happened recently in France), profits may be depressed.

If China-bashing leads the United States and Beijing to move further against US businesses investing in and trading with China, that could prove very costly to the US economy. That this may happen now is a dangerous consequence of China-bashing.

Working together (briefly)

Because they believed it would be in the US interest, then-president Richard Nixon resumed diplomatic and other relations with Beijing during his 1972 trip to the country. Chinese chairman Mao Zedong, premier Zhou Enlai, and Nixon started a period of economic growth, trade, investment and prosperity for both China and the United States.

The success of that period prompted China to seek to continue it. That same success prompted the United States in recent years to change its attitude and policies. More accurately, that success prompted US political leaders like Trump and Biden to now perceive China as the enemy whose economic development represents a threat. They demonize the Beijing leadership accordingly.

The majority of US mega-corporations disagree. They profited mightily from their access to the Chinese labor force and the rapidly growing Chinese market since the 1980s. That was a large part of what they meant when they celebrated “neoliberal globalization.” A significant part of the US business community, however, wants continued access to China.

The fight inside the United States now pits major parts of the US business community against Biden and his equally “neoconservative” foreign-policy advisers. The outcome of that fight depends on domestic economic conditions, the presidential election campaign, and the political fallout of the Ukraine war as well the ongoing twists and turns of the China-US relations.

The outcome also depends on how the masses of Chinese and US people understand and intervene in relations between these two countries. Will they see through the contradictions of China-bashing to prevent war, seek mutual accommodation, and thereby rebuild a new version of the joint prosperity that existed before Trump and Biden?

This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute, which provided it to Asia Times.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

#stockholm#lgbtq#lgbtq community#lesbian#nonbinary#lgbt pride#queer#lgbtqia#sapphic#nonbinary lesbian#gay girls#globaleducation#global issues#globalization#globalization four#muslim girl#black women#beautiful women#international women's day#womenswear#women#women's wrestling#women writers#ladies#females#prada belt women#beauty#shot#body paint

473 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watch "Within 30 Days THIS Will Change The World Forever…" on YouTube

youtube

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

“Edward Said's book ORIENTALISM has been profoundly influential in a diverse range of disciplines since its publication in 1978. In this engaging (and lavishly illustrated) interview he talks about the context within which the book was conceived, its main themes and how its original thesis relates to the contemporary understanding of "the Orient."

Said argues that the Western (especially American) understanding of the Middle East as a place full of villains and terrorists ruled by Islamic fundamentalism produces a deeply distorted image of the diversity and complexity of millions of Arab peoples.

Director: Sut Jhally, 1998.”

#Youtube#edward said#orientalism#colonialism#apartheid#genocide#military manipulation#imperialism#media#fear mongering#right and wrong#cognitive dissonance#world history#globalization#dominos#phoenix’s

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eighteen-Forties Friday: The Railway Dragon

An illustration by George Cruikshank in The Table Book, 1845 (The British Museum). The commentary in Richard A. Vogler's book Graphic Works of George Cruikshank adds that the accompanying text signed by Angus B. Reach and titled "The Natural History of the Panic" details "the way this monster has destroyed Englishmen by gobbling up their money."

Conveniently, another book from 1845 addresses the crises driven by financial speculation in railroads: The Railway Panic: Hints to Railroad Speculators, Together with the Influence Railroads Will Have Upon Society, Together with the Laws on the Subject, by Henry Wilson (Google Books). Although Wilson denounces "modern schemers" and speculation, he's very pro-railroad, and he even thinks that railway travel will break down class barriers:

In former times, each class of persons had their modes of travelling. There was for the rich, the post chaise; for the country gentleman, the mail; for the tradesman, the stage coach; and for the poor, the waggon; a man's respectability was established by the mode in which he travelled. The difference between railway and stage coach travelling is nearly all the difference between civilization and barbarism. The railways will, ultimately, reverse the picture; and the rich will be brought in contact and converse with the poor, sympathies are engendered between the various classes, and the manners of the higher class descend to the lower.

Karl Marx evidently thought something similar in 1848, according to William Scheuerman in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition): "Despite their ills as instruments of capitalist exploitation, Marx argued, new technologies that increased possibilities for human interaction across borders ultimately represented a progressive force in history."

It was Scheuerman's article on globalization that made me reflect on "the compression of territoriality," as he puts it, with new modes of travel making the world seem more accessible and smaller in the 1840s.

Writing in 1839, an English journalist commented on the implications of rail travel by anxiously postulating that as distance was “annihilated, the surface of our country would, as it were, shrivel in size until it became not much bigger than one immense city” (Harvey 1996, 242). A few years later, Heinrich Heine, the émigré German-Jewish poet, captured this same experience when he noted: “space is killed by the railways. I feel as if the mountains and forests of all countries were advancing on Paris. Even now, I can smell the German linden trees; the North Sea’s breakers are rolling against my door” (Schivelbusch 1978, 34)

Or maybe just a train monster in your kitchen

#Eighteen-Forties Friday#1840s#railways#railroads#age of steam#early victorian era#victorian#karl marx#george cruikshank#the railway panic#globalization#'in former times each class of persons had their modes of travelling'...imagine going backwards from 1845

66 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Globalization is key to maintaining the guy-in-a-robot-suit phenomenon. Globalization gives AI pitchmen access to millions of low-waged workers who can pretend to be software programs, allowing us to pretend to have transcended the capitalism's exploitation trap. This is also a very old pattern – just a couple decades after the Mechanical Turk toured Europe, Thomas Jefferson returned from the continent with the dumbwaiter. Jefferson refined and installed these marvels, announcing to his dinner guests that they allowed him to replace his "servants" (that is, his slaves). Dumbwaiters don't replace slaves, of course – they just keep them out of sight…

Cory Doctorow

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

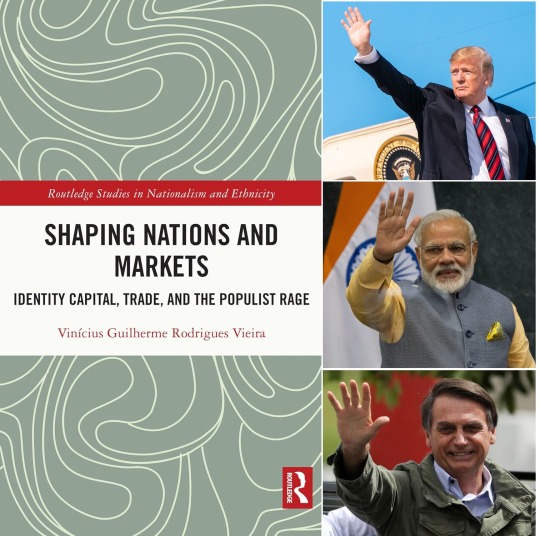

How the mobilisation of ethnic, racial and religious segments aiming at changing narratives of national identity induced nationalist populism and empowered certain economic sectors and social groups >>

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bates Littlehales

Private globalization.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The choice now is transparent. It is between a unity that allows for discussions, which seeks solidarity across difference on the one hand, and a unity that bulldozes all dissent into uniformity on the other ... One universalist but localized, the other negating the diversity[.]

Shiv Visvanathan, Foreword to the English translation of U.R. Ananthamurthy's Hindutva or Hind Swaraj

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

If you haven’t noticed already or are new to the world of art history and analysis (which, in that case, welcome!), aesthetics—whether they be architectural, industrial, sartorial, or music-related—are often inspired by the zeitgeist in which they arose.

Take the visual hallmarks of the 1980s in the west: gaudy maximalist fashion and the Memphis interior design style. Both can be attributed to the “greed is good” ethos of the era, because the dominant perception was that the economy was booming and life was good. This perception inspired people to decorate themselves or their homes in a more maximalist manner.

Meanwhile, people became more aware of the excess of the 80s in the 90s, which shifted the aesthetics. More industrial designers and artists embraced minimalism, while regular people branched out into different modes of expression, the biggest example being Gen X teens and young adults in Seattle who shunned consumerism and embraced a sartorial aesthetic more rooted in the ethos of the working class.

But the 90s had a lot more than minimalism and a dislike of the 80s going for it. It’s specifically remembered as a time of prosperity and world peace, and many people at the time believed that things would only get better as societies and cultures increasingly became interconnected due to free trade and technology. This attitude was reflected in the aesthetic sensibilities of the decade as well, from things like world-inspired clothing and cafes to futuristic music videos.

Hi, and welcome to Venusstadt. I’m Jiana. This is part one of a two part series on globalism and its aesthetics throughout the 90s.

Now, you might ask: why would you split this into two parts instead of doing one long deep dive as is en vogue nowadays? The answer is simple: I really don’t feel like editing a long video! I just can’t do it!

Okay, on to the actual content.

The 90s: America’s New Gilded Age

As far as globalization goes, there are many, many definitions that theorists can’t seem to agree upon. So I’m going with Manfred B. Steger’s concise definition of globalization as “the expansion and intensification of social relations and consciousness across world-time and world-space” (15).

Most people who discuss and critique globalization will point out that this phenomenon really isn’t unique to the late 20th century. There have always been interactions between people and cultures spread across vast swathes of geography (for example—the Silk Road, the Roman Empire, etc.); and technological advancement, such as in the form of the telegraph and the radio or trains, has always been a catalyst for these wanted or unwanted interactions (Steger 32-33).

One difference between the globalization of the 90s and the previous examples is the OBVIOUS jump in technology that had taken place. Like, sure, telegraphs are cool, but the Internet was and remains unmatched in its ability to connect people in totally different parts of the world.

ANOTHER difference is the concept of Western democracy. For a good forty-five years in the 20th century, the world was living under the shadow of the Cold War, the standoff between the Soviet Union and the United States that involved nuclear weapons and mutually assured death for everybody involved (History.com Editors).

Things finally changed between the late 80s and early 90s. The Soviet Union dissolved officially in 1991, but it was the fall of the Berlin Wall as part of the Revolutions of 1989 that really got that ball rolling (History.com Editors).

The fall of the Soviet Union left the U.S. as the world’s primary superpower (Bremmer) and led scholar Francis Fukuyama to declare the “end of history” (Fukuyama 3).

Basically, to Fukuyama, Western liberal democracy and capitalism were the end-all-be-all of humanity’s ideological evolution (Fukuyama 3), and things really couldn’t get any better than that afterward (Farago).

This concept was heavily criticized at the time and remains kind of odd and Western-centric in general. Nonetheless, there was a restlessness in the air as the West looked towards a future without its Big Bad.

Then came the Gulf War, which, thanks to advancements in media technology, was broadcasted directly into the living rooms of average people, allowing the U.S. government to show off the weapons they had developed during the Cold War in front of a live audience of millions (Brockmann 154; Lissner).

The spectacle of this digital war, the “targets, flashes, bulls-eye missiles taking off, homing in, exploding, all in the blue-ish glimmer of video light” (Brockmann 151), helped the U.S. government and military rid themselves of so-called Vietnam syndrome (Dionne) and helped the Western world feel like they were doing pretty alright.

While the 1980s tends to suck up all the attention for being a prosperous time thanks to its opulence, Weisburg notes that, despite the recession at the beginning of the decade, the United States’ poverty rate was lower throughout the Clinton-led 1990s than the Reagan-led 1980s (Weisberg).

There was also talk of a “New Economy,” in which white collar serviced-based jobs replaced traditional blue-collar industries (Alexander).

Generation X, despite being lambasted by those before them as aimless, passive, “overly sensitive at best and lazy at worst” (Gross and Scott), quickly adapted to the loss of factory jobs to outsourcing, since they were most college-educated generation in U.S. history up to that point (Gross and Scott).

Combined with a falling incarceration rate, there was the general idea that things were getting better in one way or another (Weisburg).

This sense of prosperity, technological progress, and interconnectedness did wonders to boost what scholar Steger calls the global imaginary, “people’s growing consciousness of belonging to a global community” (10).

There was a fear—or hope, if you were someone like Fukuyama—that globalization would lead to “sameness” and the endless spread of Western culture (Steger 75).

Meanwhile, others saw the Internet as the “harbinger of a homogenized ‘technoculture’” (Steger 75).

As we know many years later, these fears or hopes did not materialize, and we experienced more of a hybridization between cultures than any total takeover (Steger 6), which is what brings us to the topic of global aesthetics.

Going Global

This next section comes courtesy of Evan Collins, Froyo Tam, and the rest of the curators and archivists over at Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute (CARI). Without their archival work, this video would’ve never been made.

For aesthetics that arose from the global imaginary, there are two camps they fall into: the “global village” aesthetics and the aesthetics of “eternity,” which, again, will be covered in the next part.

The “Global Village”

The Global Village aesthetic in this video is anything inspired by the interconnectivity that arose because of technology. These, as you will see, focus more on multiculturalism, cultural exchange, and notions of world peace rather than focusing on the actual technology as the next section of aesthetics do.

This section can further be split into two subsections: non-Western and Western.

Also note that CARI goes more in-depth on the individual aesthetics, but for ease of analysis I’m grouping them all together.

One important thing to note here is that Gen. X, the group of people who were going into the workforce and thus being marketed to, were notable at the time for being more likely to hold off on careers to travel, specifically to non-Western countries like Thailand and India and Tanzania, unlike previous generations who would just go to Europe (Gross and Scott).

David Gross and Sophfronia Scott who wrote the TIME article that defined Gen X notes that this was a way for them to differentiate themselves from the “self-centered, fickle, and impractical” Baby Boomers by gaining “cultural enrichment” through “[escaping] from Western society rather than [seeking] further refinement to smooth their entry into society” (Gross and Scott).

Gen X was also viewed as being more open to different cultures thanks to their supposed “lack of original youth culture” (Gross and Scott).

That last claim would be disproven in the next few years as things such as grunge and the Riot Grrrl movement appeared, but the point is that Gen X was super into multiculturalism, which was another reason the Global Village aesthetics were a big deal back then.

With these aesthetics, most of the motifs are pulled from different time periods: hieroglyphics, maps, compasses, simplistic humanoid figures, etc.

For the non-Western aesthetics, Western conceptions of the ‘East’ (aka Orientalism) are used most often, but there are also some hints of indigenous and African cultural motifs.

Before diving any deeper, let’s address the most obvious thing: a lot of this was cultural appropriation.

I think we’ve heard this term enough times to know why it’s bad, but an example from the 90s that comes to mind is within the world music genre, which as a whole just denotes any non-Western music style.

The French band Deep Forest, who are often dubbed ethnic electronica, had a song called “Sweet Lullaby” that used a recording of a woman from the Solomon Islands without permission from the woman or the ethnomusicologist who recorded it in the 1970s (Feld).

Deep Forest claimed their goal was a general desire to foster “the respect of this tradition which humanity should cherish as a treasure which marries world harmony” (Feld 155). Neither the ethnomusicologist nor the woman whose voice was used received a penny from the song, which would become a hit (Feld 157).

It’s worth mentioning that throughout history, textiles and art were often the first thing to be exchanged when new trade routes became available (Pozzo 3). But the cultural exchange that occurred through the Silk Road or even in the Roman Empire happened in a pre-white supremacist context and power dynamic that differed from the 90s, when a new sort of Western imperialism had begun thanks to outsourcing to ‘Third World’ countries and otherwise uninhibited neoliberal free trade (Collins, “Global Village Coffeehouse”). As Lucy Mulvaney mentions:

“Cultural appropriation cannot be divorced from the prevalent issues of institutional racism and discrimination. […] You can’t play dress-up with the reality of other people’s lives or what they consider sacred” (Pozzo 7).

Deep Forest’s debacle with “Sweet Lullaby” is also an example of the salvage paradigm. The term is used by anthropologists to critique the idea that non-Western people are too weak to preserve their own cultures from the sweeping changes of modernism (Gurney). Adding to that, Nicole Bennett, in her critique of Jean Paul Gaultier’s 1994 Global Village Chic collection, uses the term to refer to the idea that “most non-Western people are [perceived as] marginal to the advancing world system” (Bennett 35), thus rendering their aesthetics as “of the past” rather than able to continue fluidly into the present and future.

All the non-Western global village aesthetics reinforced the idea that what is non-Western is non-normative and of the past while that which is Western is normal and current (Bennett 29). Here, Western culture is the default and a symbol of modernity and advancing civilization, while non-Western cultures are exotified for consumption and rendered endangered relics, even though actual people were still taking part in the visual aesthetics of their cultures. As David Byrne said of the label ‘world music’ in a 1999 New York Times article:

“It’s a none too subtle way of reasserting the hegemony of Western pop culture. It ghettoizes most of the world’s music. A bold and audacious move, White man!” (Byrne)

Despite the professed good intentions behind these displays of cultural plurality, they did little to improve perceptions of the cultures they displayed, and instead reinforced them as pre-modern and marginal. Bell Hooks in 1992 wrote that constructions of otherness such as these just reinforce inequality and social hierarchy (Bennett 36), saying that “the hope is that the desires for the ‘primitive’ or fantasies about the Other” can perpetuate “the idea that ‘there is pleasure to be found in the acknowledgement and enjoyment of racial difference” without the effort to challenge these structures (Bennett 36).

Basically, people felt like it was enough to feel enriched by this exposure to different cultures and never felt the need to question the Western hegemony or white supremacy that caused these cultural displays to be less common.

Which brings us to the graphic and interior design aesthetics, specifically Global Village Coffeehouse. This aesthetic also played up the idea of the non-Western as pre-modern by focusing on natural motifs and “primitive” imagery with its amalgamation of various ancient cultures from Egyptian to Aztec to, in some places, Greek (Collins, “Global Village Coffeehouse Aesthetic”).

Interestingly, as Evan Collins who coined the term points out, the Global Village Coffeehouse aesthetic also contains a lot of colonialist imagery a la the Age of Discovery, through things such as “Mercator globes, compasses, rigged ships, maritime wheels, [and] heraldic moons and suns” (Collins, “Global Village Coffeehouse Aesthetic”). Juxtaposed with the non-Western motifs, including these symbols is startling, since it could be a nod to the perceived evolution of Western society and thus an indirect reference to the snuffing of these non-Western cultures.

Then we have the Western global aesthetics, all of which are reflections of a Western past.

Evan Collins identifies about three which were still en vogue around the 90s: Neoclassical Postmodernism, Renaissance Revival, and two others that are based on the Mediterranean and the Age of Discovery.

Neoclassical aesthetics, which are based on Greco-Roman art and architecture, have always been popular and remain the most popular style of architecture throughout the Western world. Greek philosophy and the Roman empire are considered the foundations of Western civilization by many (King 3). Today you most often see this architectural style on things like museums or state buildings because of the ethos of stateliness or officiality it imparts.

Neoclassical Postmodernism as presented by Evan Collins popped up in the late 1970s. The reason it came about again in the 1970s seems to be a reaction to Modernist architecture after World War II, which architect Donald McMorran referred to as a “dictatorship of taste” (Denison). I’ll get into the exact implications of this later, but just know it’s an early example of that whole weird REJECT MODERNITY / EMBRACE TRADITION thing that conservative incels like to use.

At any rate, this became popular again when a conservative movement was building in the late 70s, went through the 80s when the conservative movement was at its peak, and lasted until at least the early 90s in this iteration. As you can see, some of these pictures are pretty ironic; you have these relics of the supposed great Western past juxtaposed with these hyper-consumerist images of, like, gift shops. .

Again, the Roman Empire was proto-globalist: it included many cultures, created roads for travel and communication, and helped lead to a relatively brief period of peace which enabled population growth, even more trade, and the eventual spread of Christianity (Fernandes)—which, again, makes it an important Western cornerstone.

Neoclassical PoMo likely isn’t a direct response to 90s multiculturalism considering how it predates the 90s, but it would be a mistake I feel to ignore the irony of these existing at the same time.

Yes, all these aesthetics are alike in that they reference a bygone temporal space, but ancient Greco-Roman culture and aesthetics have been used to delegitimize those of non-Western cultures since late 18th and 19th centuries (King 3). Misreadings of Greco-Roman concepts of the Other—they did not know whiteness and anyone who wasn’t Greek (for the Greek empire) or Roman (for the Roman empire) was a barbarian—informed a lot of race theory during and after the Age of Discovery (King 10). This would also shape Western constructions of modernity, in that race theorists justified colonialism and slavery as a good thing because it helped spread “superior Western values” to people deemed of a lower status (King 15).

Remember these concepts, because they’re important for what’s coming up.

Semi-Conclusion

BUT this is where I’ll be splitting the video. The next part, of course, will cover the aesthetics that are more aligned with the technological advancements of the 90s, most notably Y2K.

Until then, feel free to like this video and be sure to hit the subscribe button to be notified when the next part drops. I also make short-form videos on TikTok about women in arts, fashion, and culture. Feel free to also follow me on Twitter, where I reblog and post fun things. Thanks for watching!

•••

SOURCES

Alexander, Charles P. “The New Economy.” Time, 30 May 1983, https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,926013-10,00.html. Accessed 7 April 2023.

Bennett, Nicole. “Global Village Chic: ‘Multicultural Fashion’ and the Commodification of Pluralism.” Alternate Routes: A Journal of Critical Social Research, vol. 14, 1997, pp. 21-44.

Bremmer, Ian. “These are the 5 Reasons Why the U.S. Remains the World’s Only Superpower.” Time, 28 May 2015, https://time.com/3899972/us-superpower-status-military/. Accessed 26 April 2023.

Brockmann, Stephen. “The Cultural Meaning of the Gulf War.” Michigan Quarterly Review, vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 147-178, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.act2080.0031.002:02. Accessed 22 April 2023.

Byrne, David. “Crossing Music’s Borders in Search of Identity; ‘I Hate World Music.’” New York Times, 3 Oct. 1999, https://archive.nytimes.com/query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage-9901EED8163EF930A35753C1A96F958260.html. Accessed 10 April 2023.

Collins, Evans. “The Global Village Coffeehouse Aesthetic.” Are.na, 6 Sep. 2018, https://www.are.na/blog/the-global-village-coffeehouse-aesthetic. Accessed 5 April 2023.

Dionne, E. J. “Kicking the ‘Vietnam Syndrome.” Washington Post, 4 March 1991, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1991/03/04/kicking-the-vietnam-syndrome/b6180288-4b9e-4d5f-b303-befa2275524d/. Accessed 10 April 2023.

Farago, Jason. “The ‘90s: The Decade that Never Ended.” BBC News, 5 Feb. 2015, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20150205-the-1990s-never-ended. Accessed 5 April 2023.

Feld, Steven. “A Sweet Lullaby for World Music.” Public Culture, vol. 12, no. 1, 2000, pp. 145-71. http://artsites.ucsc.edu/faculty/abeal/4classes/lullaby:feld.pdf.

Fernandes, Fabio. “Wanderlust of the Ancients.” Aeon, 24 Nov. 2022, https://aeon.co/essays/the-roman-empire-was-a-cosmopolitan-network-of-adventurers. Accessed 7 April 2023.

Fukuyama, Francis. “The End of History?” The National Interest, no. 16, 1989, pp. 3-18, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24027184. Accessed 22 April 2023.

Gross, David M, and Sophronia Scott. “Proceeding With Caution.” Time, 16 July 1990, https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,970634-9,00.html. Accessed 7 April 2023.

Gurney, Jane. “The Salvage Paradigm.” Panya Clark Espinal, http://www.panya.ca/publication_salvage_paradigm_introduction.php. Accessed 11 April 2023.

History.com Editors, “Cold War History.” History, 6 Dec. 2022, https://www.history.com/topics/cold-war/cold-war-history. Accessed 22 April 2023.

King, Emily Anne. The (Mis-) Use of Greco-Roman History by Modern White Supremacy Groups: The Implications of the Classics in the Hands of White Supremacists. 2019. State University of New York, Honors Thesis.

Lissner, Rebecca F. “The Long Shadow of the Gulf War.” War on the Rocks, 22 Nov. 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/11/the-long-shadow-of-the-gulf-war-2/. Accessed 10 April 2023.

Pozzo, Barbara. “Fashion between Inspiration and Appropriation.” Laws, vol. 9, no. 5, 2020, pp. 1-26. doi:10.3390/laws9010005.

Steger, Manfred B. Globalism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Weisberg, Jacob. “In Defense of the ‘90s,” Slate, 1 Nov. 2001, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2001/11/in-defense-of-the-90s.html. Accessed 5 April 2023.

#global village coffeehouse#y2k#neoclassicism#globalism#globalization#aesthetics#aesthetic history#fashion#architecture#interior design#Youtube

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

#capitalism#imperialism#globalization#global south#third world#palestine#environment#indigenous#white supremacy#colonization

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zionism Is Not Judaism

#jews#judaism#jewish#zion#zionist#zionism#agenda 21#agenda 2030#event 201#id2020#covid 1984#plandemic#cashless society#cryptocurrency#one world government#the great reset#globalization

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Look at Japan. Earlier this month, the Bank of Japan announced that it is not going ahead with plans to implement a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) after all. And why not? Because the people don't want it, they don't need it and they won't use it, that's why.

Specifically, as the Asia Times reports, in the heavily cash-reliant Japanese economy, people understand that cash is safe, highly liquid and useful in emergencies. It also ensures equal access to services for the country's aging population, many of whom are not comfortable with digital payments. In fact, despite the widespread adoption of cashless payment services at various businesses in Japan over the past several years, cash usage has actually been rising. It seems more and more people are catching on to the technocrats' plans to use CBDCs as a tool of control and are running as fast as they can in the opposite direction.

James Corbett, “Technocracy Is Insane, Anti-Human and It WILL Fail” (July 31st 2022).

136 notes

·

View notes