#franco arcalli

Text

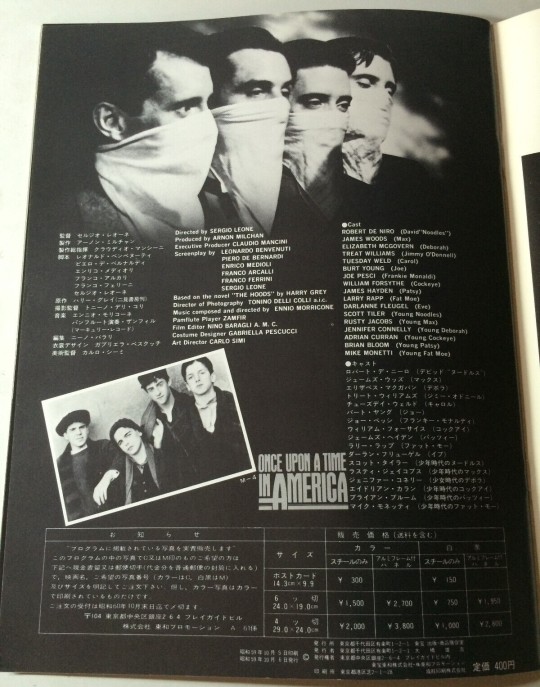

#Once Upon a Time in America#Sergio Leone#Harry Grey#Robert De Niro#James Woods#William Forsythe#Leonardo Benvenuti#Piero De Bernardi#Enrico Medioli#Franco Arcalli#Stuart Kaminsky#Ernesto Gastaldi#80s

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Novecento, 1976

#drama#history#novecento#1900#bernardo bertolucci#franco arcalli#giuseppe bertolucci#dominique sanda#gérard depardieu#bucolic

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

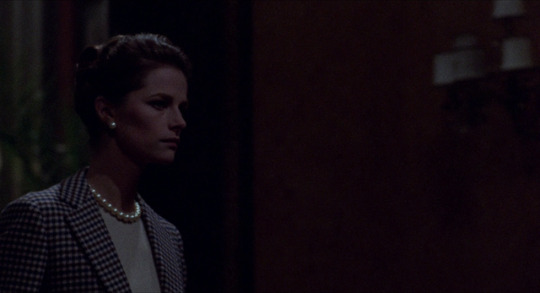

The Night Porter (Liliana Cavani, 1974).

#il portiere di notte#liliana cavani#charlotte rampling#dirk bogarde#alfio contini#franco arcalli#nedo azzini#jean marie simon#osvaldo desideri

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jane Fonda in Spirits of the Dead: Metzengerstein

Alain Delon in Spirits of the Dead: William Wilson

Terence Stamp in Spirits of the Dead: Toby Dammit

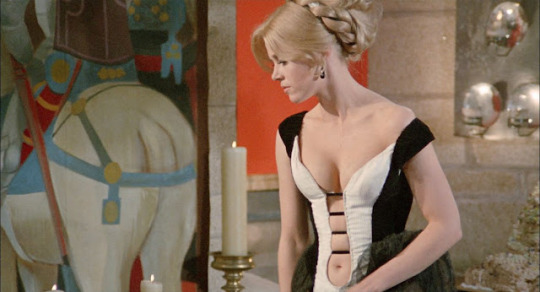

Spirits of the Dead (Roger Vadim, Louis Malle, Federico Fellini, 1968)

Metzengerstein

Cast: Jane Fonda, Peter Fonda, James Robertson Justice, Françoise Prévost. Screenplay: Roger Vadim, Pascal Cousin, based on a story by Edgar Allan Poe. Cinematography: Claude Renoir. Production design: Jean André. Film editing: Hélène Plemiannikov. Music: Jean Prodromidès

William Wilson

Cast: Alain Delon, Brigitte Bardot, Renzo Palmer. Screenplay: Louis Malle, Clement Biddle Wood, based on a story by Edgar Allan Poe. Cinematography: Tonino Delli Colli. Production design: Ghislain Uhry. Film editing: Franco Arcalli, Suzanne Baron. Music: Diego Masson.

Toby Dammit

Cast: Terence Stamp, Salvo Randone, Annie Tonietti, Marina Yaru. Screenplay: Federico Fellini, Bernardino Zapponi, based on a story by Edgar Allan Poe. Cinematography: Giuseppe Rotunno. Production design: Piero Tosi. Film editing: Ruggero Mastroianni. Music: Nino Rota.

Of the three short films based on Edgar Allan Poe stories collected here under the title Spirits of the Dead, only the third, Federico Fellini's Toby Dammit, a freewheeling version of Poe's "Never Bet the Devil Your Head," really works. Roger Vadim's Metzengerstein is simply cheesy, with his then-wife Jane Fonda sashaying around in supposedly period costumes that are designed to reveal as much flesh as possible. The casting of her brother, Peter, as the man she loves, is obviously there to elicit a frisson of some sort, but it doesn't. Louis Malle's William Wilson stuffs a little too much of Poe's doppelgänger fable into its confines, and despite the presence of a cigar-puffing Brigitte Bardot, manages to pull whatever punches the story may have had, ending up rather dull. But Toby Dammit is a small gem, a concentration of Fellini's usual grotesques and decadents into a bright satire on celebrity: It's almost impossible to watch another awards show without recalling Fellini's acid-bathed take on it. Only the conclusion of the film really retains much of Poe, which suggests that Vadim and Malle might have been better off devising contemporary riffs on the material, as Fellini does.

10 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Michelangelo Antonioni's Masterpiece ''Zabriskie Point'' 1970 Full Ending

TONINO GUERRA

Titolo originale

Zabriskie Point

Paese di produzione

Stati Uniti d'America

Anno

1970

Durata110 min

Rapporto

2,35:1

Genere

drammatico

Regia

Michelangelo Antonioni

Soggetto

Michelangelo Antonioni

Sceneggiatura

Michelangelo Antonioni

,

Tonino Guerra

,

Sam Shepard

,

Clare Peploe

,

Fred Gardner

Produttore

Carlo Ponti

Fotografia

Alfio Contini

Montaggio

Franco Arcalli

,

Michelangelo Antonioni

(non accreditato)

Musiche

Pink Floyd

,

Jerry Garcia

Scenografia

Dean Tavoularis

Interpreti

e

personaggi

Mark Frechette: Mark

Daria Halprin: Daria

Paul Fix: Proprietario del bar

G.D. Spradlin: Socio dell'avvocato Lee

Bill Garaway: Morty

Kathleen Cleaver: Kathleen

Rod Taylor: Avvocato Lee Allen

Lee Duncan: Poliziotto nel deserto (non citato nei titoli)

Harrison Ford: Studente del college (non citato nei titoli)

Jim Goldrup: Studente del college (non citato nei titoli)

0 notes

Text

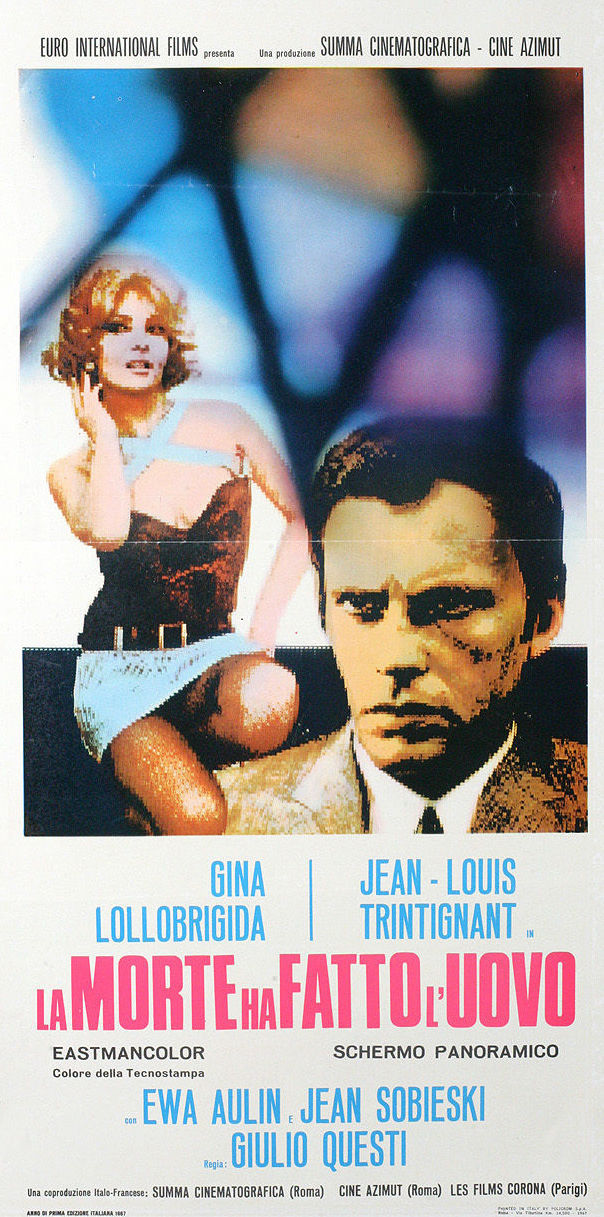

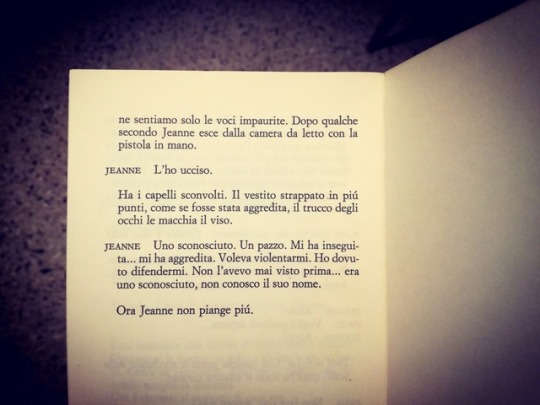

La morte ha fatto l'uovo (Death Laid an Egg, 1968)

"You want to run away? Since when? I thought you liked this life, with the three of us."

"You still don't know me. I'm looking for something definitive."

"You mean love?"

"Why not?"

"I don't think there's anything more undefined."

#La morte ha fatto l'uovo#death laid an egg#italian cinema#giulio questi#films i done watched#Franco Arcalli#Gina Lollobrigida#Jean Louis Trintignant#Ewa Aulin#Jean Sobieski#Renato Romano#Vittorio André#Giulio Donnini#Biagio Pelligra#Cleofe Del Cile#Aldo Bonamano#Ugo Adinolfi#Bruno Maderna#Ohhh delicious‚ delicious cinema‚ finally some good film. I mean don't get me wrong‚ this is a big ymmv case; I can well imagine some would#Hate this film (and the letterboxd reviews are very mixed). Those people are wrong. Take a hoary old thriller plot and the basis for an#Unassuming proto giallo‚ but then shoot it all in a beautifully delicate French new wave inspired style‚ fill the script with faux#Philosophical dialogue‚ and then throw in so many ideas and striking images; everything from anti mechanisation and pro worker sentiments#With a dash of pure science fiction‚ a searing streak of anti capitalist absurdism‚ some unlikely humour and all carried off with such#Sheer confidence‚ such breathless style. All set to a magnificent‚ bizarre score of jangling discordant keys and atonal bleeps and bloops.#Truly unique‚ a real one off. I can see why some might dislike it‚ I can even understand some of the accusations of pretentiousness or of#Incoherent excess; but if only every film could be so unique‚ could be so courageously strange and unapologetically.....itself.#Worth noting that this exists in multiple versions; a shorter‚ streamlined giallo cut may well make for a simpler genre picture but the#Reviews aren't exactly glowing. I watched the full directors cut (probably the same cut that was first released in Italy in 68) with nearly#20 minutes more exposition and weirdness‚ and I appreciated every second. I suspect (again from reading reviews) that the English dub may#Change some plot points quite significantly as well

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

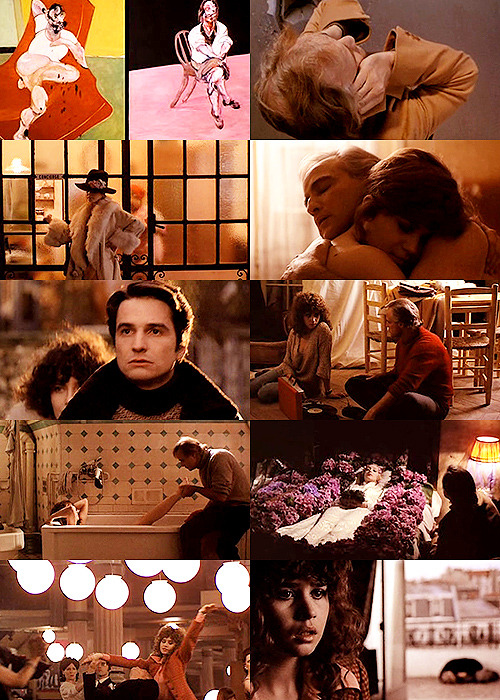

Last Tango in Paris (1972). A young Parisian woman meets a middle-aged American businessman who demands their clandestine relationship be based only on sex.

It’s honestly been a while since I watched a movie I loathed this much. It’s overwrought, cruel, and depicts violence in a way that’s titilating. It does nothing to give Jeanne any sort of interior life – something that’s only made all the worse when you hear of the lack of consent to certain scenes behind the camera. It’s an ugly, cliched film and lacks any sort of merit beyond letting the director live out a misogynistic fantasy. Yuck, yuck, yuck. 1/10.

#last tango in paris#1973#Oscars 46#Nom: Director#Nom: Actor#Bernardo Bertolucci#Franco Arcalli#Agnès Varda#marlon brando#Maria Schneider#Maria Michi#Giovanna Galletti#france#french#romance#drama#autumn-spring#rape#crime#1/10

11 notes

·

View notes

Video

NOVECENTO

Bernardo Bertolucci

TRAMA:

Quasi cinquant’anni di storia italiana (1901-1945), raccontati attraverso le vite di Alfredo e Olmo, amici separati dalla differenza di classe.

RECENSIONI:

È singolare che un film così dichiaratamente a tesi possa essere anche tanto spudoratamente divertente. Divertente, beninteso, se si ama la "macchina teatrale" in sé e per sé al punto da tollerare, in suo nome, oltre cinque ore di proiezione incentrate su una sola idea: quanto sono cattivi i padroni. Bertolucci è regista di notevole intelligenza e gusto (benché alcuni suoi film dimostrino il contrario), ma soprattutto è un artista divorato dall'ambizione (dagli esiti più o meno felici). In quest'opera tenta per così dire di salvare capra e cavoli (impegno e spettacolo, scegliete voi a che elemento della metafora abbinarli), raccontando mezzo secolo di vicende italiane, ma soprattutto di lotta di classe, in una cornice da melodramma, cinematografico e non (lo scenografo è Ezio Frigerio, nume del teatro lirico contemporaneo). Il film, dopo il flash forward del prologo, si apre con l'annuncio della morte di Verdi: ma la drammaturgia operistica (meglio, l'immagine enfatica e maliziosamente infedele che il senso comune si è costruito di essa) resta la cifra caratteristica dell'intera narrazione. Ben due personaggi al centro dell'intreccio (Alfredo e Attila) si chiamano come i protagonisti delle opere di Verdi, le musiche di Morricone si adeguano al clima di "intrattenimento culturale", tra sonorità stentoree e romantiche svenevolezze fuori tempo massimo, la fotografia di Storaro fa di tutto per sembrare uscita da una cartolina inizio secolo. Di fronte a questo circo equestre, fatto di masse oranti o minacciose, di contadini che ballano nel bosco mentre i signori lavorano nei campi, di massacri inspiegabili, di pause oniriche, si rimane per un po' sbalorditi, come bambini alla prima visione assoluta: almeno nella prima ora, Novecento è la dimostrazione pratica della potenza del cinema, oltre ogni contenuto e nonostante qualunque goffaggine o forzatura a livello di script. Ma poi ci si accorge che, dietro il trucco, il volto non è poi così intrigante: i personaggi sono tutti d'un pezzo, ottimi o pessimi (e, guarda caso, i pessimi fanno tutti una gran brutta fine), l'intreccio è risaputo, degno di un romanzetto rosa o di un testo scolastico edificante, il lusso della produzione è fastidiosamente ostentato, l'impaginazione data dalla regia un po' troppo leccata. Il vero problema di questo film non è l'inconciliabilità di spettacolo e idea, ma il dissidio insanabile tra pubblico e privato: mentre la politica, messa in scena secondo stilemi roboanti e pedestri (vedi il "Quarto Stato" sbattuto in primo piano all'inizio del primo atto e il "balletto rosso" del prefinale, tanto sgangherato da essere quasi un'involontaria icona dell'anticomunismo), lascia indifferenti o al massimo un po' irritati, l'amicizia che lega i due protagonisti, sottolineata dalla scena finale che letteralmente annulla il tempo e lo spazio, affascina e commuove. In mezzo a tante banalità, restano alcune trovate originali, realmente sovversive: vedi il nonno ed il nipote che "sparano" sugli altri membri della famiglia. Tra gli attori, solo alcuni riescono a non soccombere al ridicolo. De Niro, per una volta poco istrione, è perfetto, Laura Betti e Burt Lancaster, nonostante l'esilità delle rispettive parti, restano scolpiti nella memoria. Depardieu tutto sommato se la cava, Sutherland sfoggia un ghigno diabolico che lo rende spaventosamente simile all'imbranato Kiefer, la Sanda è una macchietta, la Sandrelli come al solito inascoltabile.

— Stefano Selleri

Nazione: Italia

Anno Produzione: 1976

Genere: Drammatico

Durata: 301'

Interpreti: Gerard Depardieu, Robert De Niro, Burt Lancaster, Sterling Hayden, Dominique Sanda, Donald Sutherland, Alida Valli, Stefania Sandrelli, Romolo Valli, Laura Betti, Francesca Bertini.

Sceneggiatura: Franco Arcalli, Bernardo Bertolucci, Giuseppe Bertolucci.

Fotografia: Vittorio Storaro

Musiche: Ennio Morricone

#novecento#1900#stefano selleri#italia#dramma#gerard depardieu#robert de niro#burt lancaster#sterling hayden#dominique sanda#donald sutherland#alida valli#stefania sandrelli#romolo valli#laura betti#francesca bertini#franco arcalli#bernardo bertolucci#giuseppe bertolucci#vittorio storaro#ennio morricone

0 notes

Photo

Bernardo Bertolucci, Ultimo tango a Parigi

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Death Laid an Egg will be released on Blu-ray on October 13 via Cult Epics. The first 2,000 units include a a slipcase with fluorescent inks and reversible artwork with the Italian title, La morte ha fatto l'uovo.

The 1968 Italian giallo film is directed by Giulio Questi (Django Kill... If You Live, Shoot!) from a script he wrote with Franco Arcalli (Once Upon a Time in America). Gina Lollobrigida, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Ewa Aulin, and Jean Sobieski star.

Death Laid an Egg has been new restored in 2K from the original 35mm negative. It includes a the complete director's cut along with the shorter "giallo" cut, each presented in English and Italian. Special features are listed below.

Special features:

Reconstructed director’s cut of the film (104 minutes)

Giallo cut of the film (91 minutes)

Director’s cut audio commentary by film critics Troy Howarth and Nathaniel Thompson (new)

Review by Italian film critic Antonio Bruschini (new)

Director Giulio Questi’s final interview from 2010

Doctor Schizo and Mister Phrenic - 2002 short film directed by Giulio Questi

English and Italian trailers

Death Laid an Egg is an avant-garde giallo starring Jean-Louis Trintignant as a married man and suspected serial killer, Gina Lollobrigida as his delectable yet overly domineering careerist wife, and Ewa Aulin as his murderous double-crossing mistress in this mystery thriller.

#death laid an egg#giallo#italian horror#italian giallo#italian film#cult epics#dvd#gift#la morte ha fatto l'uovo#gina lollobrigida#jean louis trintignant#ewa aulin#guilio questi#60s horror#1960s horror

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Once Upon a Time in America#Sergio Leone#Robert De Niro#James Woods#Elizabeth McGovern#Jennifer Connelly#Treat Williams#William Forsythe#Scott Tiler#Rusty Jacobs#Brian Bloom#Adrian Curran#Harry Grey#Leonardo Benvenuti#Piero De Bernardi#Enrico Medioli#Franco Arcalli#Franco Ferrini#Stuart Kaminsky#Ernesto Gastaldi#80s

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Novecento, 1976

#novecento#1900#drama#history#bernardo bertolucci#franco arcalli#giuseppe bertolucci#donald sutherland#laura betti#bourgeois

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Il conformista (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1970).

#il conformista (1970)#bernardo bertolucci#jean-louis trintignant#stefania sandrelli#vittorio storaro#franco arcalli#ferdinando scarfiotti

213 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1900 (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1976)

Cast: Robert De Niro, Gérard Depardieu, Donald Sutherland, Dominique Sanda, Laura Betti, Burt Lancaster, Sterling Hayden, Stefania Sandrelli, Alida Valli, Romolo Valli, Paolo Pavesi, Roberto Maccanti. Screenplay: Franco Arcalli, Giuseppe Bertolucci, Bernardo Bertolucci. Cinematography: Vittorio Storaro. Production design: Maria Paola Maino, Gianni Quaranta. Film editing: Franco Arcalli. Music: Ennio Morricone.

In his attempt at an epic, Bernardo Bertolucci gives us many new and arresting things, but none perhaps more startling -- and ultimately more fatal to the film -- than Robert De Niro playing a passive weakling. The actor known for such aggressors as young Vito Corleone, for Travis Bickle, Jake LaMotta, even Rupert Pupkin seems crucially miscast as the padrone of an Italian estate who can't bring himself to take sides in the conflict between communists and fascists. The De Niro smirk is still there, but it doesn't seem to fit on the face of Alfredo Berlinghieri, who waffles even when his best friend, his boyhood companion Olmo Dalcò (Gérard Depardieu), is threatened by the fascist overseer Attila Mellanchini, played -- not to say overplayed -- by Donald Sutherland. Bertolucci crafts a relationship between Alfredo and Olmo that goes beyond bromance and somehow persists for a lifetime. They are nominally twins, born on the same day in 1901 as the legitimate son of the landowner and the bastard of a peasant on his estate. The film begins with the end of World War II and the routing of the fascists, then flashes back to their birth and boyhood, skips ahead to the end of World War I, the rise and fall of fascism, and concludes with a coda in which the elderly Alfredo and Olmo are still roughhousing. It's meant to be a capsule version of the 20th century -- the original Italian title, Novecento, means "nineteen hundreds." The film is never unwatchable, but its epic ambitions are undone, I think, by Bertolucci's instinct for melodrama at the expense of characterization. The villains, Attila and his companion Regina (Laura Betti), go so far over the top in their evil-doing -- Attila casually kills a small boy with the same coolness with which he slaughters a cat earlier in the film -- that they become almost comic. It's a striking turn in the wrong direction for the director who earlier gave us a subtly intricate look at the character of a fascist with Jean-Louis Trintignant's performance in The Conformist (1970). There are colorful cameos by Burt Lancaster and Sterling Hayden to be savored, and Vittorio Storaro's cinematography and Ennio Morricone's score help the film immeasurably, but the main impression left by 1900 is of a director who overreached himself.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

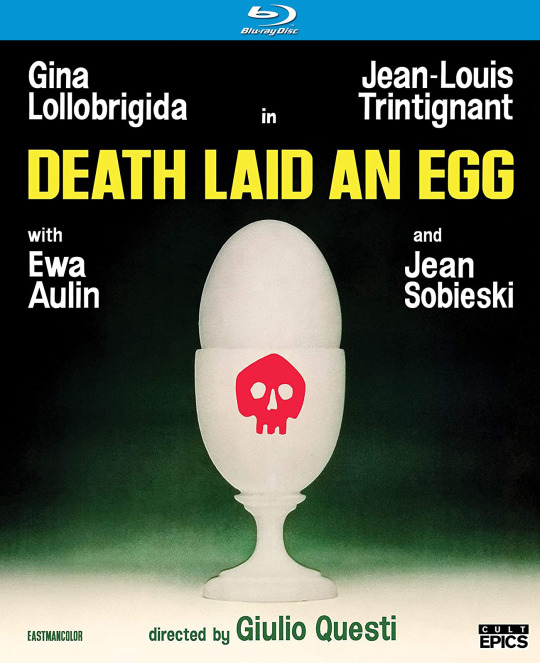

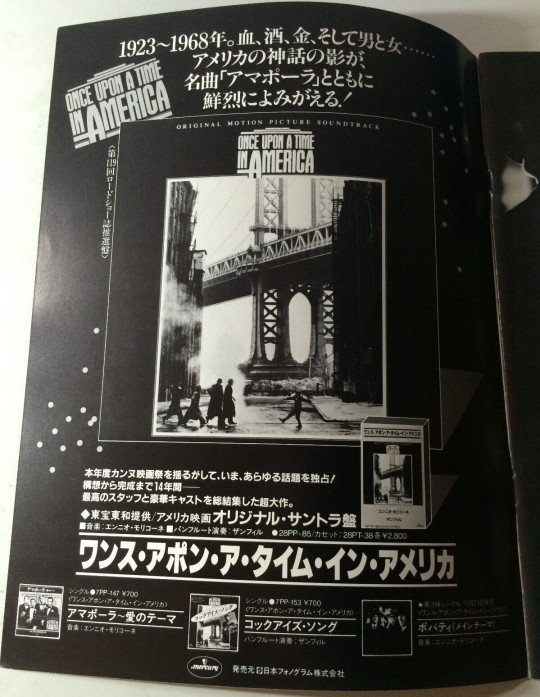

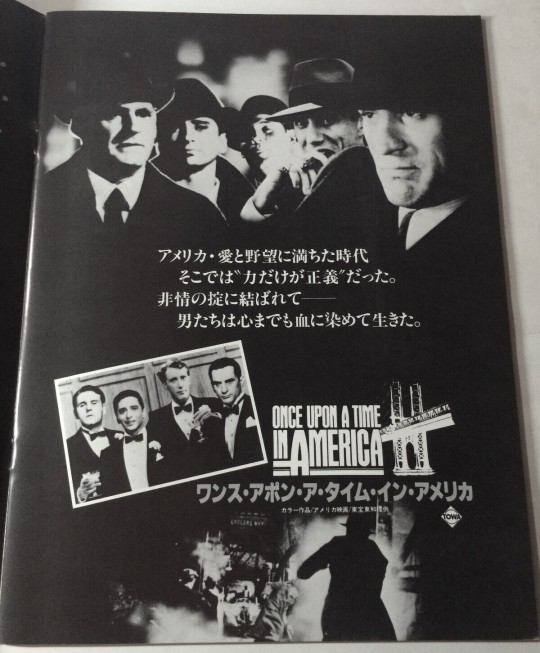

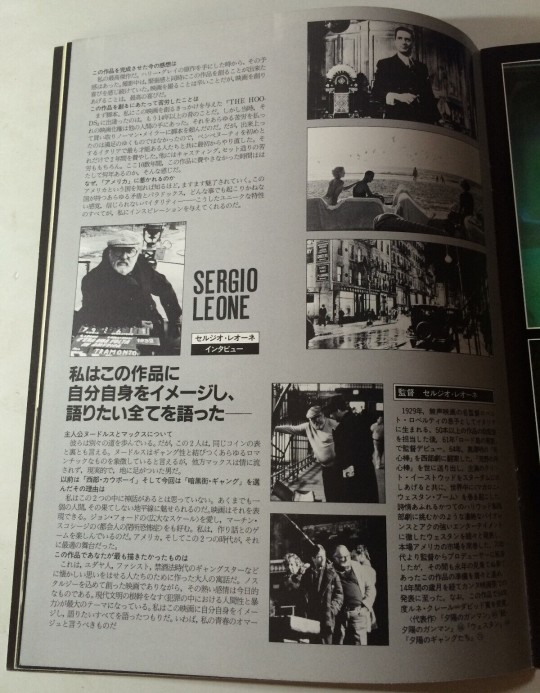

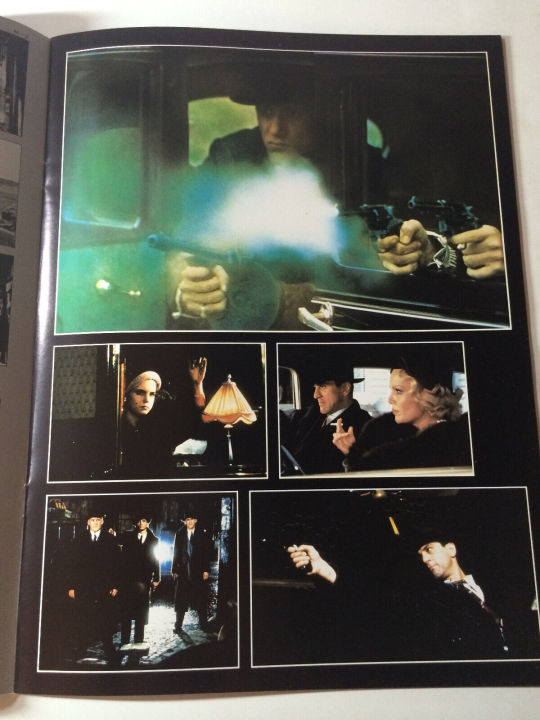

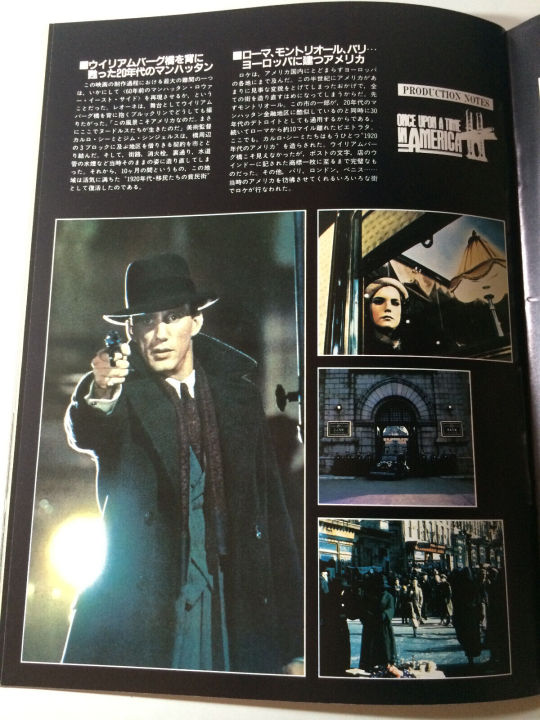

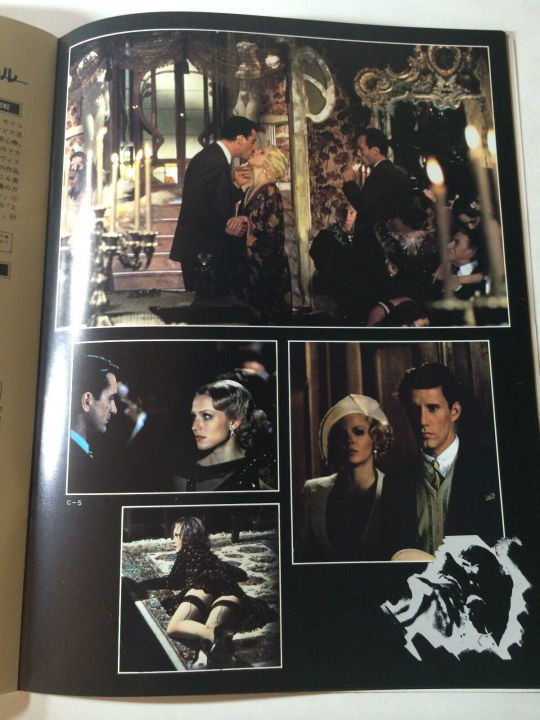

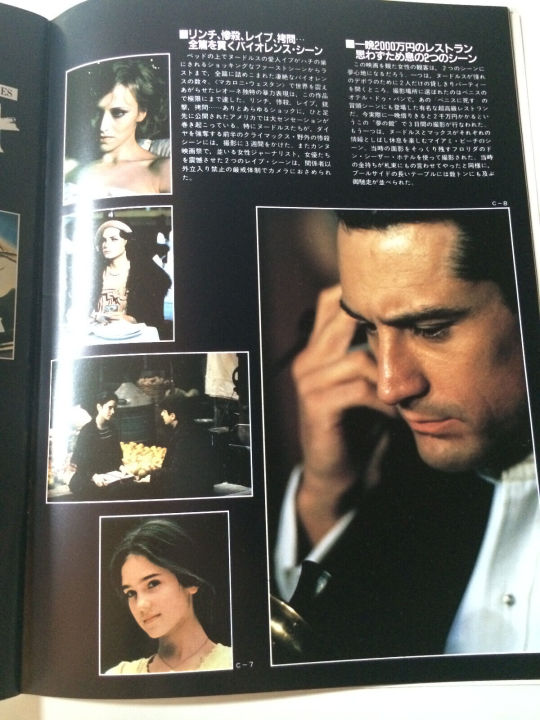

Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

Italian director Sergio Leone made a name for himself worldwide with the Dollars trilogy of Westerns starring Clint Eastwood as the Man with No Name. These movies, along with Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), had more stylized violence than the typical Hollywood Western, and audiences flocked to see what some waved off as pulp novelties. During this period, an idea had been reverberating in Leone’s mind; no longer could he ignore his imagination’s wills. Leone’s success led him to spend ten years working on this passion project, even declining an offer to direct The Godfather (1972). Based on The Hoods by Harry Grey, Once Upon a Time in America is a gangster epic filled with betrayal, crime, graphic violence, and regret. The film alternates between three time periods: the late 1910s/early ‘20s, the final three years of Prohibition from 1930-1933, and 1968. It is Leone’s most ambitious project after a thirteen-year absence from filmmaking, and his last.

In New York City’s Lower East Side, we follow a handful of young Jewish boys who engage in petty thievery, grow to complete contracts for organized crime, and later make their fortunes bootlegging during Prohibition. The film centers on David “Noodles” Aaronson (Robert De Niro as adult Noodles; Scott Tiler as a child). He is first seen in a Chinese opium den in 1933 after seeing three of his friends’ corpses – burnt beyond recognition – whisked away from a crime scene. A non-diegetic telephone rings during this wordless montage – a blaring, ceaseless ringing serving as an aural pang of guilt. That guilt will be gradually explained as the film progresses. Soon after this opium-induced retreat, Noodles will depart New York City for Buffalo. He will return decades later, his hair and soul fading, after receiving a suspicious invitation. Once Upon a Time in America’s first half concentrates on Noodles’ childhood, alternating with scenes from his 1968 return. The film’s second half intercuts between Prohibition and 1968.

Noodles’ boyhood friends are the protagonist’s de facto family. They include Patrick “Patsy” Goldberg (James Hayden as adult Patsy; Brian Bloom as a child), Philip “Cockeye” Stein (William Forsythe as an adult Cockeye; Adrian Curran as a child), Dominic (Noah Moazezi), and Maximillian “Max” Bercovicz (an excellent and up-and-coming James Woods as adult Max; Rusty Jacobs as a child). Fat Moe (Larry Rapp as an adult Moe; Mike Monetti as a child) is not part of the gang, but is nevertheless a friend who knows their secrets. The film also features Noodles’ young love interest, Deborah (Elizabeth McGovern as adult Deborah; a debuting Jennifer Connelly as a child) and friend/underage prostitute Peggy (Amy Ryder as adult Peggy; Julie Cohen as a child). Also appearing in the film are Joe Pesci (whose unclear role in the film is heavily downplayed in the European cut), Burt Young, Tuesday Weld, Treat Williams, and Danny Aiello. Louise Fletcher's cameo appears only in the most recent restoration.

Before continuing with this review, I want to note that there are multiple versions of Once Upon a Time in America available to viewers. Leone’s film debuted at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival with a runtime of 229 minutes (the “European cut”). For the American general release one week later, the film’s distributor (the Ladd Company, via Warner Bros.) cut the film to 139 minutes without Leone’s permission or input. The American theatrical cut – which was released on VHS in the 1980s and ‘90s and sometimes appears on television – rearranges scenes to play in a strictly chronological structure and removes essential plot details, essentially butchering Leone’s directorial intent. A 2014 Blu-ray release of Once Upon a Time in America includes additional footage bringing the runtime to 250 minutes, but the additional footage – due to the degradation of the original negative – appears worse for wear. This review is based on the European cut, which is the recommended print for all those seeing this film for the first time.

With a screenplay by Leone, Leonardo Benvenuti, Piero De Bernardi, Enrico Medioli, Franco Arcalli, and Franco Ferrini, Once Upon a Time in America is told through the lens of an unreliable narrator in Noodles. How one views the film changes radically depending on which period should be considered the “present”. If the viewer interprets Once Upon a Time in America as using the 1968 scenes as its anchor, the film is an old man’s reverie – where a lifetime of guilt is revisited and ghosts are confronted. In this interpretation, are Noodles’ memories of his childhood and young adulthood sanitized to spare him further pain? How does he square with all the pain he has been responsible for? Or perhaps one might view Once Upon a Time in America using 1933, as Noodles retreats to the opium den, as the anchor. Here, the 1968 scenes become an opium dream or a nightmare, a painful future that may have been. If indeed this is an opium-induced dream (which would make the 1968 scenes nothing but a hallucination), does that make the childhood scenes even less genuine than in the former interpretation? That Leone and his writers never force the viewer down either avenue speaks to its thoughtful screenplay.

No matter how one reads this film, it requires complete attention. Characters age over fifty years, friendships are formed and destroyed, and innocence is forever lost. Whether it is viewed as an old man occupied by his violent past or a young gangster attempting to smoke away his pain, Once Upon a Time is awash in regret. As much as viewers might sympathize with Noodles, Leone’s film portrays Noodles’ violence as the result of terrible choices influenced by his friends. Granted, there is one occasion where he kills in self-defense. But even that killing is laced with rage and revenge. Faced with the choice between his friends and the money involved with their operations and being with Deborah, Noodles will attempt to have both. Deborah’s disapproval of the gang’s behavior – her opposition becomes more tacit as she ages – assures that Noodles retain some semblance of a conscience as Max’s arrogance permeates through all their friends. Neither fully committing to the appeals from Deborah or his friends, Noodles will lose both.

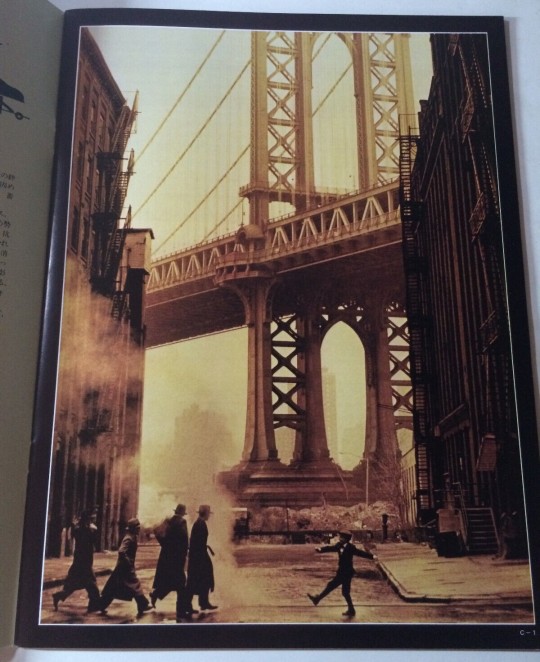

In the film, smoke or steam is usually present just before or during moments tinged of bittersweet memory. Whether emanating as puffs from an opium pipe, the steam billowing from New York City’s manholes on a frigid day, or discharges from a passenger train, it is a demarcation of an event that will irrevocably affect Noodles’ life. Potentially, due to the film’s openness to interpretation, smoke or steam may also herald moments where Noodles’ memories are most suspect – through conscious reframing of his story or opium-influenced phantasms. Either way, certain narrative threads are left incomplete, raising questions over whether those dangling characters and subplots were Leone’s original intention. Perhaps Leone here is acknowledging the voids in human memory – people and things half-forgotten. Unlike its genre counterparts, Once Upon a Time in America leaves little space for comic relief. Any levity in the film is snuffed out almost immediately due to monstrous lust, performative masculinity, or Noodles’ weariness. The elderly Noodles is stone-faced, wrapped into a world frozen in time the moment he boarded that train to Buffalo. His pain is omnipresent in Once Upon a Time in America. Even in the earliest scenes of his childhood, the years of rumination can be felt in the film’s deliberate pace. Robert De Niro and Scott Tiler, respectively, embody the older Noodles’ sorrow and the younger Noodles’ conflicted feelings.

Like American Western films, the gangster genre is rife with mythologizing and, at times, a glorification of their protagonists’ violent lives. Where Westerns over the last half-century have deconstructed their role in the American mythos, the gangster film – probably because gangster films were never as ubiquitous as Westerns at their respective pinnacles of popularity – has not done so nearly as much introspection. Before Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990) and especially The Irishman (2019), Once Upon a Time in America stood mostly alone among gangster films as a rueful examination of its protagonist’s violent lifestyle. The film consistently undermines its characters’ celebrations and successes with the consequences of their prior actions. Those consequences weigh on Noodles still.

But Leone is not entirely successful in this regard. Once Upon a Time in America has two overlong rape scenes – both of which turned my stomach the longer they went on – following a fruitful robbery (this one follows an unsettling submissive fantasy by its victim) and a glamorous date, respectively. The two rapes are committed by Noodles; both scenes serve to highlight his descent into depravity rather than express a minimal concern for the victim. Once Upon a Time in America, already uninterested in developing its female characters beyond sex objects, frames Noodles as a husk of a man because of the murders and robberies he has committed, not his treatment of women. Just because the film has adopted Noodles’ viewpoint – in his childhood and young adulthood, he cannot differentiate between objectification and love – does not mean Leone and his screenwriters can wave away his misogyny as secondary to his violent tendencies. His misogyny and criminality are distinguishable, but both were learned from the same people and environment. This dynamic persists even from the first moment that Jennifer Connelly appears as the young Deborah. There, Deborah sexually teases the young Noodles in a way that neither reflects her personality as a child or as an adult. Is that the result of the opium clouding Noodles’ memory or is it Noodles’ obsession with Deborah?

Once Upon a Time in America is beautifully shot by Tonino Delli Colli (1966’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, 1997’s Life Is Beautiful) and edited by Nino Baragli (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Once Upon a Time in the West). Like a photograph that has faded somewhat but still captures the likeness and character of its subjects, the brown environments and warmly-lit interiors capture the spirit of these neighborhoods of New York City’s Lowest East Side. Life is hardscrabble here, with those born into the prevalent poverty rarely escaping from it. Their Jewishness, verbally and visually, is strangely downplayed by Leone. The film’s long takes – several last over thirty seconds – without any cuts from Baragli allow the viewer to reflect on its changing characters, internalizing the film’s scope and depth of Noodles’ introspection. For the 1968 scenes, the browns are mostly replaced by overcast grays in exterior and interiors. The colors, no longer as warm or as diverse, help the film navigate its temporal and tonal transitions.

youtube

Ennio Morricone’s powerful score does even more to strengthen the film’s emotional power. The recently-passed composer, best known for his work on Leone’s Dollars trilogy, was a classically-raised/taught, jazz-loving experimenter whose sound could be bold and brash. Upending expectations for what the Western could sound like with anachronistic electronic elements and guitar, Morricone suspends any anachronisms for his Once Upon a Time in America score. The viewer will hear an odd pan flute (not Morricone’s decision) and diegetic/non-diegetic jazz music, but the defining aspect of the score is its romantic minimalism. One does not associate minimalism with grand emotions, but the score’s romantic minimalism – encapsulated by “Deborah’s Theme” – does not preclude the pathos it evokes. The rests in the lushly-orchestrated “Deborah’s Theme” (according to Morricone himself, despite the cue’s name, it can also be interpreted as the film’s main theme) reflect Noodles’ silent longing and remorse. Even at mezzo piano with no dialogue or sound effects present, Morricone’s cues pierce the soul. As longtime collaborators, Leone respected Morricone’s talents, allowing his friend and colleague’s music to be the star for long stretches. Leone allows Morricone to envelop the viewer in its textural splendor. The orchestral renditions of “Amapola” and The Beatles’ “Yesterday” are effective in placement and arrangement. Whether it is his theme for childhood and poverty, for the film at large, or for Deborah, Morricone’s score to Once Upon a Time in America is an essential part of his film scoring career – a career that spans so many titles, that most of it has not been heard outside of his native Italy.

Before and when making this film, Leone intended to direct two films running around 180 minutes each. Convinced by his producers to whittle Once Upon a Time in America to the 269-minute version that should be sought for a first viewing, Leone was horrified to hear that the Ladd Company – frightened by the runtime and (justifiably) the rape scenes – decided to eviscerate his film. When word eventually (and inevitably) reached Leone’s North American fans that they would not be receiving a version of Once Upon a Time in America that respected Leone’s authorial voice, the film bombed at the box office and was savaged by most anyone who saw it. To some critics including the Chicago Tribune’s Gene Siskel, Once Upon a Time in America’s American theatrical version was the worst film of 1984; in an about face for those same critics, the European cut was the best film of 1984. Eighteen minutes of footage for Once Upon a Time in America have still not seen the light of day due to continuing legal entanglements surrounding them. Leone’s ardent admirers remain hopeful for their eventual inclusion on a future print.

As he challenged the tropes of American Westerns, so too did Leone subvert what might be expected from a gangster film. Or, perhaps with a cynical grin, Leone is challenging the essence and veracity of cinematic narrative. Once Upon a Time in America is an underappreciated, imperfect movie whose reputation continues to grow the further removed it is from its botched release. America’s traditions of tall tales and melting pot storytelling make villains and bystanders of the unsavory characters contained within. Haunted by a past that cannot be changed, Noodles attempts to reclaim his life’s story from those who have written it. As the viewer, we project our anxieties and insecurities onto images spliced to make narrative sense. Authorship disputes and the struggle between legend and fact permeate cinema. Seldom do they converge as movingly as they do here.

My rating: 9.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#Once Upon a Time in America#Sergio Leone#Robert De Niro#James Woods#Elizabeth McGovern#Joe Pesci#Burt Young#Tuesday Weld#Danny Aiello#James Hayden#William Forsythe#Larry Rapp#Ennio Morricone#Tonino Delli Colli#Nino Baragli#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Novecento | Bernardo Bertolucci (1976)

The epic tale of a class struggle in twentieth century Italy, as seen through the eyes of two childhood friends on opposing sides.Director: Bernardo BertolucciWriters: Franco Arcalli (screenplay by), Giuseppe Bertolucci (screenplay by) | 1 more credit »Stars: Robert De Niro, Gérard Depardieu, Dominique Sanda

4 notes

·

View notes