#even if the prisons are estates rather than cells. like. especially when we are talking about 30+ years

Text

the historical comparison games with henry viii are so taxing....i hate twitter, lmfao

#i am not going defend any of the heinous and hell-deserving things he did but i am really not about pretending like comparatively his#successors and predecessors were morally superior ; or at least not by very much?#and YES even if we limit it to queens/kings of england#for fuck's sake; george i of england ordered the murder of his wife's lover#and was drowned with heavy stones#he then proceeded to divorce and arrest his former wife#she was never again allowed to see any of her children#and imprisoned her for the rest of her life#if life imprisonment is much better than judicial murder like...idt it is by very much?#and permanent child separation#even if the prisons are estates rather than cells. like. especially when we are talking about 30+ years#and i think this about juana of castile too#also the sons of francis i WERE actually kept in dank cells by charles v .#and they were CHILDREN??

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Candyman: How Bernard Rose and Clive Barker created the horror classic

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

In the winter of 1992, one word was enough to send a chill down the spine of horror fans far and wide: Candyman.

Released in October of that year, Candyman was a slasher movie with a killer hook – quite literally. A horror movie built around an urban legend claiming that if you say the word “Candyman” five times into a mirror, a murderous spirit with a hook for a hand would appear, with grave consequences for those who summoned him.

In a time before the internet and social media, the original Candyman’s lore was enough to spark discussion among curious moviegoers who asked each other: would you say the potentially deadly incantation?

It was a talking point the movie’s marketing leaned heavily into with taglines like “We dare you to say his name five times!” and “Candyman, Candyman, Candyman, Candyman… Don’t Say Again!”

Director Bernard Rose took inspiration for the idea from the urban legend of Bloody Mary, rather than the Clive Barker short story “The Forbidden,” which Candyman was adapted from.

According to the legend, Bloody Mary’s spectre could be summoned by chanting her name repeatedly into a mirror. One of Rose’s masterstrokes was to assimilate this folklore into the Candyman mythology, although it was not without its teething problems.

“In the original script, they were supposed to say Candyman 13 times, not five times, because in the Bloody Mary legend they say it 13 times,” Rose tells Den of Geek. “During the first read through they started going ‘Candyman, Candyman…’ and I was falling asleep. You can’t do it 13 times. It goes on too long. Five is about the largest number you can hear. It did come from Bloody Mary but I had seen Beetlejuice, so I’d have to say Beetlejuice should probably get some credit.”

Rose first hit upon the idea of adapting “The Forbidden” after he was approached about making a film out of another story from Barker’s lauded Books of Blood anthology, “In the Flesh.” But that story wasn’t quite suited to a cinematic adaptation.

“I thought it was really well written, but impossible to make because it’s about two prisoners in complete darkness in a cell,” he says. “And of course, the one thing you can’t represent in a movie is darkness, because if you are in a movie theater there’s nothing to see. It would make a great radio play but wasn’t really a great idea for a movie.”

It was during his initial research into the Books of Blood that Rose read “The Forbidden,” Barker’s short story about a university student who, while studying and photographing graffiti at a local housing estate, learns from locals about a string of murders attributed to a mythical killer known as Candyman.

A rising star at the time, Rose had already collaborated with Jim Henson on The Muppet Show and The Dark Crystal, as well as directing iconic music videos like the S&M themed promo for Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s “Relax,” which ended up being banned by MTV. His debut feature, the dream-like dark fantasy horror Paperhouse, had been released to widespread acclaim opening up a wealth of possibilities when it came to his next film.

Rose was immediately struck by Barker’s story and the way it played on “the idea of belief.”

“All of these people believe in the Candyman, which actually means the Candyman exists, whereas if they stop believing in him he disappears, like how the old deities, like the Roman gods, died because people stopped caring. The idea that if enough people believe something, they manifest it. That’s scary.”

By the time he read “The Forbidden,” Rose had already struck up a friendship with Barker, who he met at Pinewood Studios while the latter was working on Nightbreed, the follow-up to his wildly successful directorial debut Hellraiser.

It was a match made in heaven – or maybe that should be hell – and a bond that made securing the rights to the short story that would become Candyman “really easy” according to Rose, who simply called Barker up with the author agreeing to sign off on the deal and sign on as executive producer.

Rose credits Professor Jan Harold Brunvand’s book The Vanishing Hitchhiker as a major inspiration to his script. A folklore scholar, Brunvand’s book explored the origins of several notable urban legends and has been widely credited with igniting America’s obsession with the phenomenon.

“The whole urban legends thing hadn’t actually been addressed in a movie at that point, which is kind of extraordinary when you think about it,” Rose says. “It helped give the film this intellectual aspect, the idea of having an intellectual elite character studying the myth not from a sociological point of view, but from a semiotics point of view. Somebody who was intellectual and therefore naturally skeptical about something supernatural.”

While some authors have been known to be especially protective of their source material when it comes to adaptation, Rose recalls Barker encouraging him to “run free with it.”

“He liked the script very much. He was very behind it and at certain key moments, as much as anything, he was an enthusiast. Clive is wonderful. A really nice, smart guy.”

One thing they agreed on was that the story would need to be relocated from its original setting in Liverpool, England, for a very specific reason.

“At the time within genre films, there was there was a real problem with people understanding regional accents, and Clive had that problem on Hellraiser where they ended up having to loop (ADR) the whole movie and change it into a sort of weird unspecific setting, when it’s clearly some market town outside London,” he says. “If we were starting the film now, unquestionably we would have done it in Liverpool. It’s funny, things change, but back then, we wanted it to be somewhere specific. So I said, let’s make it specifically American. That seemed like the easiest thing to do.”

Rose hit upon the idea of setting the film in Chicago after noting similarities in the public housing found there and in the story’s original Liverpool setting.

The Illinois Film Commission took Rose on a tour of the city’s most troubled neighborhoods, which included Cabrini Green. “It wasn’t the worst place they showed us by any means, the Robert Taylor Homes on the South Side but Cabrini Green was right by downtown Chicago and was just spectacular.”

Rose recalls first being taken there in the company of a “full police escort.” Eager to see the neighborhood from a different perspective, he returned later on his own and befriended somebody who lived there.

“That’s the woman who the character of Anne Marie [the single mother who helps Helen with her investigation and whose infant son Anthony ends up being abducted by the Candyman] is based on,” Rose says.

Another crucial step in the development of Candyman came when the filmmaker began researching the history of Cabrini Green.

“I discovered old articles in the Chicago Reader about a series of murders that happened in Cabrini Green, including one where the killer came into the apartment through the medicine cabinet through a breeze block.”

One such article, by Steve Bogira, detailed the killing of 52-year-old Ruthie McCoy, whose pleas to a 911 caller explaining that intruders were breaking in through her bathroom cabinet went ignored.

“There was a weak spot that you could actually get into people’s medicine cabinets, which is basically inserting holes in the breeze block and you can just literally punch them out and get into somebody’s apartment.”

These articles ended up featuring in the film for real, during the scene where Helen (Virginia Madsen) began researching the Candyman myth. Another element that rang true to life was the fact that the nearby Sandburg Village was “architecturally identical” to Cabrini Green with the only difference being that the former was turned into condos while the latter became public housing. These elements all combined to inform Candyman’s biggest departure from the original short story: Candyman would be Black.

“I wanted to make the film grounded in reality and the whole racial subtext of the film came out of that,” he says. “It wasn’t part of the original story. That was about politics and class differences. The racial element was added to it by the specificity of the location.”

Rose also incorporated his own experience discovering much of this material into Helen’s narrative. “I think that’s why it still feels relevant and powerful now because it came out of something real.”

The filmmaker credits the architecture of Cabrini Green with adding a layer of dread to proceedings.

“The early 80s was the point where we were seeing how modernist architecture could really decay in the most frightening ways and be more scary than the old Gothic spaces that were always designed to be plain and simple.”

Rose felt the film offered an opportunity to draw parallels between the Candyman myth and the myths attached to life in Cabrini Green.

“There was always this kind of exaggerated fear of the place like you might get shot, which is ultimately a very powerful form of racism,” he says. “The real danger is probably very, very small unless you happen to be very unlucky.”

While the stories of murderers emerging through mirrored medicine cabinets tied into the Candyman mythology, mirrors played a wider thematic role in Rose’s film.

“The film has got a lot of mirroring in it, from the imagery to the mirrored apartment. The idea that Helen’s apartment is the same as the ones in Cabrini green. It’s just about what side of the road you are on.”

Even so, Rose refutes any suggestion of Candyman having any kind of deep agenda.

“The film was not done with a thesis in mind that I then went out to prove. It was more like I was interested in the setting we had and the story which is unchanged from the short story.”

Madsen ended up landing the role of Helen, the protagonist after Rose’s then-wife Alexandra Pigg, who had been cast in the role, was forced to drop out after discovering she was pregnant.

When it came to the Candyman himself, one rumor Rose immediately squashes is the notion that Eddie Murphy was ever considered or even interested in the part.

“If Eddie Murphy had wanted to do it in 1991, it wouldn’t have even been a discussion, it would have just happened,” he says. “Yeah, that’s not even a tiny bit true.”

Instead, Rose and the film’s producers only ever had eyes for Tony Todd.

“He pretty much just came in and was fabulous and that was that. He just had it in every sense of the word and it was pretty obvious. There wasn’t even a discussion about it.”

Securing the rights, finding a great location and landing a stellar cast had all proven relatively straightforward for Rose. One thing that definitely wasn’t straightforward, however, would be the film’s use of bees.

The film called for scenes in which Madsen would be covered in bees, while in one particularly memorable shot, the insects would be seen emerging from Todd’s mouth, as per Barker’s story, which took its inspiration from the Bible and the story of how Samson killed a young lion only to find bees and honey in its corpse. The imagery struck a chord with the author, who weaved it into the ever-expanding Candyman mythology.

Coming at a time before filmmakers could fall back on CGI, Rose was in need of an expert bee wrangler. He found one in apiarist Norman Gary.

“I saw him, he was on the Johnny Carson show playing the clarinet, covered in bees. He was quite a character,” Rose says. “He had synthesized queen bee pheromones and had hives of bees on the top of the studio and he was hatching them for the first 48 hours of their lives. Their stingers aren’t fully developed at that point so they’re not really that dangerous.”

Gary would supply the immature bees for the crucial scenes, using pheromones to have them cluster in the areas Rose required before gently vacuuming them up into a pouch when filming was complete.

Rose speaks in glowing terms about the bees themselves, describing them as “intelligent but also very predictable” which made filming the scenes somewhat pain free. Except in the most obvious sense of the word.

“Everybody got stung quite a bit and certainly when we were doing those scenes, there were quite a lot of crew members who just stopped turning up to work,” he says. “I think people didn’t want to go into a studio that was literally buzzing with bees all the time because you would get stung. I remember asking Norman ‘How do you prevent yourself from getting stung?’ and he said ‘You don’t. You just decide it doesn’t bother you.’”

Away from the sound of bees, Rose credits composer Philip Glass with delivering a pitch perfect score, that imbued the film with a sense of both the Gothic and the academically-minded analytical.

“I gave him a brief to just score it for organ, voices, and piano,” Rose says. “He loved that idea of it being very kind of minimal orchestration. So he wrote the suite basically of the music that’s in the film. I think he’s hands down the best living American composer. Very original.”

For all the praise the film and its score received, Candyman was not without its detractors including several notable Black film directors at the time.

Reginald Hudlin, who had directed Boomerang and House Party and would go on to serve as a producer on Django Unchained called it “worrisome” while fellow filmmaker Carl Franklin said the decision to made Candyman Black and move the story to Cabrini Green was “irresponsible and racist” for casting a Black man in the role of a killer.

“People were nervous before we made the film because of his ethnicity, but I always said I understand how horror villains work,” Rose says. “The bogeyman is the hero. That’s it. That’s how they function. And it’s certainly true in the case of Candyman in that Tony’s character becomes larger than the film’s other characters.”

Much of that was down to timing. “The most disappointing thing you can do in a movie is bring out the monster,” he says. “This is why The Exorcist is a masterpiece. You never see a monster. What you see is its effect on the little girl.”

In the case of the Candyman, Rose used the first half of the film to build a sense of dread tinged with a sense of tragedy with the character’s backstory which explained how he was killed in the late 19th century over his relationship with a white woman. Even as audiences catch their first glimpse of Todd in that striking leather, fur-lined coat, they are being told a story.

“The idea of the costume was to show that he was quite bourgeois, like he was on his way to the opera when he was killed. It was a reminder that he was successful and affluent yet none of that protected him.”

Rose took his cues from the Orson Welles classic The Third Man in holding back on the introduction of his titular killer.

“Every single conversation in the first half of The Third Man is about Harry Lime.” he says. “So when Orson Welles finally appears It’s one of the great entrances in film history because you’re just dying to hear what he’s got to say,”

The Candyman writer also points to an alternative reading of the film that adds a fascinating subtext to the role of race in the movie.

“It’s an entirely subjective movie told from the perspective of Helen,” Rose says. “So whatever happens in the film, it’s what she thought happened and isn’t necessarily objective. There is definitely an interpretation of the film where she committed the murders.”

The film, he says, offers up an extension of one of the original themes of Barker’s book which was the fear of poverty.

“Inequality and oppression creates fear among the oppressors, because they’re afraid of one day being called to account,” he says. “The film is about that in some ways, and that’s why it is still powerful. But I did not have any sort of agenda except to try to represent what I’d seen in Chicago as realistically as possible.”

Rose would not return for any of the sequels, with 1995’s Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh helmed by future Twilight Saga director Bill Condon. In his absence and despite the best efforts of Todd in the titular role, the franchise died out after a third film, 1999’s lamentable Candyman: Day of the Dead.

Rose puts these failures down to a mismanagement of the properties and a rush to get a follow-up out after the surprise runaway success of his film, which made $25 million from a modest $8 million budget.

“The temptation when making sequels is to just basically do the same thing again which actually doesn’t satisfy anyone,” he says. “You have to develop it and you have to make it more complex and make the story actually have a grander arc. I had ideas, but they wanted to make damn sure that they got them out of me as quickly as possible so they could get on with the serious business of fucking it up. But that’s fairly normal, unfortunately.”

However, he says he submitted a proposal for a sequel which was “pretty extreme.”

“One of the producers read it and said it was the most disgusting thing he’s ever read. All I can say about it is that it involved cannibalism and royalty.”

Though he remains coy on the finer details, he insists it would have made a “great movie” though it wouldn’t have been a straightforward sequel by any means.

“It was an expansion of the ideas in Candyman and also involved another short story of Clive’s that was actually made later by somebody else, ‘The Midnight Meat Train,’ which was set on the London Underground.”

That said, Rose remains fully supportive of Nia DaCosta’s new film, which has breathed life back into Candyman once again.

“Honestly, I think that sequel is probably better than anything I could have come up with,” he says. “It needed to be taken over by someone African-American, so it’s better that way because if I make the film again, it’s just going to be about the same thing as the first one.”

Ultimately, he feels “immense pride” at the idea that Candyman has earned a place as a horror icon to rival the likes of Michael Myers and Freddy Krueger though he sees that as “something separate to the movie in a weird way.”

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

“It was intended as a horror film, as a subjective, visceral experience. Obviously, if you write something and direct it, whatever you make is a reflection of your views on a myriad number of subjects. That’s one of the things that’s good about the film, the story is open to exploration.”

The post Candyman: How Bernard Rose and Clive Barker created the horror classic appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/39UfRdV

0 notes

Text

Life on the Grid

I’ve long been interested in the process by which new games turn into new gaming genres or sub-genres.

Most game designers know from the beginning that they will be working within the boundaries of an existing genre, whether due to their own predilections or to instructions handed down from above. A minority are brave and free enough to try something formally different from the norm, but few to none even of them, it seems safe to say, deliberately set out to create a new genre. Yet if the game they make turns into a success, it may be taken as the beginning of just that, even as — and this to me is the really fascinating part — design choices which were actually technological compromises with the Platonic ideal in the designer’s mind are taken as essential, positive parts of the final product.

A classic example of this process is a genre that’s near and dear to my heart: the text adventure. Neither of the creators of the original text adventure — they being Will Crowther and Don Woods — strikes me as a particularly literary sort. I suspect that, if they’d had the technology available to them to do it, they’d have happily made their game into a photorealistic 3D-rendered world to be explored using virtual-reality glasses. As it happened, though, all they had was a text-only screen and a keyboard connected to a time-shared DEC PDP-10. So, they made do, describing the environment in text and accepting input in the form of commands entered at the keyboard.

If we look at what happened over the ten to fifteen years following Adventure‘s arrival in 1977, we see a clear divide between practitioners of the form. Companies like Sierra saw the text-only format as exactly the technological compromise Crowther and Woods may also have seen, and ran away from it as quickly as possible. Others, however — most notably Infocom — embraced text, finding in it an expansive possibility space all its own, even running advertisements touting their lack of graphics as a virtue. The heirs to this legacy still maintain a small but vibrant ludic subculture to this day.

But it’s another, almost equally interesting example of this process that’s the real subject of our interest today: the case of the real-time grid-based dungeon crawler. After the release of Sir-Tech’s turn-based dungeon crawl Wizardry in 1981, it wasn’t hard to imagine what the ideal next step would be: a smooth-scrolling first-person 3D environment running in real time. Yet that was a tall order indeed for the hardware of the time — even for the next generation of 16-bit hardware that began to arrive in the mid-1980s, as exemplified by the Atari ST and the Commodore Amiga. So, when a tiny developer known as FTL decided the time had come to advance the state of the art over Wizardry, they compromised by going to real time but holding onto a discrete grid of locations inside the dungeon of Dungeon Master.

The British gaming press, who had quite the gift for slangy nomenclature, had already dubbed turn-based dungeon crawlers in the Wizardry mold “blobbers.” (The term arose from the way that these games typically “blobbed” together a party of four or six characters, moving them in lockstep and giving the player a single first-person — first-people? — view of the world.) The new lineage inadvertently spawned by Dungeon Master was promptly dubbed “real-time blobbers.”

By whatever name, this intermediate step between Wizardry and the free-scrolling ideal came equipped with its own unique set of gameplay affordances. Retaining the grid allowed you to do things that you simply couldn’t otherwise. For one thing, it allowed a game to combine the exciting immediacy of real time with what remains for some of us one of the foremost pleasures of the earlier, Wizardry style of dungeon crawl: the weirdly satisfying process of making your own maps — of slowly filling in the blank spaces on your graph paper, bringing order and understanding to what used to be the chaotic unknown.

This advertisement for the popular turn-based dungeon crawl Might and Magic makes abundantly clear how essential map-making was to the experience of these games. “Even more cartography than the bestselling fantasy game!” What a sales pitch…

But even if you weren’t among the apparent minority who enjoyed that sort of thing, the grid had its advantages. The fact was, much of the emergent interactivity of Dungeon Master‘s environment would have been impossible without it. Many of us still recall the eureka moment when we realized that we could kill monsters by luring them into a gate square and pushing a button to bash them on the heads with the thing as it tried to descend, over and over again. Without the neat order of the grid, where a gate occupying a square fills all of that square as it descends, there could have been no eureka.

So, within a couple of years of Dungeon Master‘s release in 1987, the real-time blobber was establishing itself in a positive way, as its own own sub-genre with its own personality, rather than the unsatisfactory compromise it may first have seemed. Today, I’d like to do a quick survey of this popular if fairly brief-lived style of game. We can’t hope to cover all of the real-time blobbers, but we can hit the most interesting highlights.

Bloodwych running in its unique two-player mode.

Most of the games that followed Dungeon Master rely on one or two gimmicks to separate themselves from their illustrious ancestor, while keeping almost everything else the same. Certainly this rule applied to the first big title of the post-Dungeon Master blobber generation, 1989’s Bloodwych. It copies from FTL’s game not only the real-time approach but also its innovative rune-based magic system, and even the conceit of the player selecting her party from a diverse group of heroes who have been frozen in amber. By way of completing the facsimile, Bloodwych eventually got a much more difficult expansion disk, similar to Dungeon Master‘s famously difficult Chaos Strikes Back.

The unique gimmick here is the possibility for two players to play together on the same machine, either cooperatively or competitively, as they choose. A second innovation of sorts is the fact that, in addition to the usual Amiga and Atari ST versions, Bloodwych was also made for the Commodore 64, Amtrad CPC, and Sinclair Spectrum, much more limited 8-bit computers which still owned a substantial chunk of the European market in 1989.

Bloodwych was the work of a two-man team, one handling the programming, the other the graphics. The programmer, one Anthony Taglioni, tells an origin story that’s exactly what you’d expect it to be:

Dungeon Master appeared on the ST and what a product it was! Three weeks later we’d played it to death, even taking just a party of short people. My own record is twelve hours with just two characters. I was talking with Mirrorsoft at the time and suggested that I could do a DM conversion for them on the C64. They ummed and arred a lot and Pete [the artist] carried on drawing screens until they finally said, “Yes!” and I said, “No! We’ve got a better design and it’ll be two-player-simultaneous.” They said, “Okay, but we want ST and Amiga as well.”

The two-player mode really is remarkable, especially considering that it works even on the lowly 8-bit systems. The screen is split horizontally, and both parties can roam about the dungeon freely in real time, even fighting one another if the players in control wish it. “An option allowing two players to connect via modem could only have boosted the game’s popularity,” noted Wizardry‘s designer Allen Greenberg in 1992, in a review of the belated Stateside MS-DOS release. But playing Bloodwych in-person with a friend had to be if anything even more fun.

Unfortunately, the game has little beyond its two-player mode and wider platform availability to recommend it over Dungeon Master. Ironically, many of its problems are down to the need to accommodate the two-player mode. In single-player mode, the display fills barely half of the available screen real estate, meaning that everything is smaller and harder to manipulate than in Dungeon Master. The dungeon design as well, while not being as punishing as some later entries in this field, is nowhere near as clever or creative as that of Dungeon Master, lacking the older game’s gradual, elegant progression in difficulty and complexity. As would soon become all too typical of the sub-genre, Bloodwych offered more levels — some forty of them in all, in contrast to Dungeon Master‘s twelve — in lieu of better ones.

So, played today, Bloodwych doesn’t really have a lot to offer. It was doubtless a more attractive proposition in its own time, when games were expensive and length was taken by many cash-strapped teenage gamers as a virtue unto itself. And of course the multiplayer mode was its wild card; it almost couldn’t help but be fun, at least in the short term. By capitalizing on that unique attribute and the fact that it was the first game out there able to satiate eager fans of Dungeon Master looking for more, Bloodwych did quite well for its publisher.

Captive has the familiar “paper doll” interface of Dungeon Master, but you’re controlling robots here. The five screens along the top will eventually be used for various kinds of telemetry and surveillance as you acquire new capabilities.

The sub-genre’s biggest hit of 1990 — albeit once again only in Europe — evinced more creativity in many respects than Bloodwych, even if its primary claim to fame once again came down to sheer length. Moving the action from a fantasy world into outer space, Captive is a mashup of Dungeon Master and Infocom’s Suspended, if you can imagine such a thing. As a prisoner accused of a crime he didn’t commit, you must free yourself from your cell using four robots which you control remotely. Unsurprisingly, the high-tech complexes they’ll need to explore bear many similarities to a fantasy dungeon.

The programmer, artist, and designer behind Captive was a lone-wolf Briton named Tony Crowther, who had cranked out almost thirty simple games for 8-bit computers before starting on this one, his first for the Amiga and Atari ST. Crowther created the entire game all by himself in about fourteen months, an impressive achievement by any standard.

More so even than for its setting and premise, Captive stands out for its reliance on procedurally-generated “dungeons.” In other words, it doesn’t even try to compete with Dungeon Master‘s masterful level design, but rather goes a different way completely. Each level is generated by the computer on the fly from a single seed number in about three seconds, meaning there’s no need to store any of the levels on disk. After completing the game the first time, the player is given the option of doing it all over again with a new and presumably more difficult set of complexes to explore. This can continue virtually indefinitely; the level generator can produce 65,535 unique levels in all. That should be enough, announced a proud Crowther, to keep someone playing his game for fifty years by his reckoning: “I wanted to create a role-playing game you wouldn’t get bored of — a game that never ends, so you can feasibly play it for years and years.”

Procedural generation tended to be particularly appealing to European developers like Tony Crowther, who worked in smaller groups with tighter budgets than their American counterparts, and whose target platforms generally lacked the hard drives that had become commonplace on American MS-DOS machines by 1990. Yet it’s never been a technique which I find very appealing as anything but a preliminary template generator for a human designer. In Captive as in most games that rely entirely on procedural generation, the process yields an endless progression of soulless levels which all too obviously lack the human touch of those found in a game like Dungeon Master. In our modern era, when brilliant games abound and can often be had for a song, there’s little reason to favor a game with near-infinite amounts of mediocre content over a shorter but more concentrated experience. In Captive‘s day, of course, the situation was very different, making it just one more example of an old game that was, for one reason or another, far more appealing in its own day than it is in ours.

This is the screen you’ll see most in Knightmare.

Tony Crowther followed up Captive some eighteen months later with Knightmare, a game based on a children’s reality show of sorts which ran on Britain’s ITV network from 1987 until 1994. The source material is actually far more interesting than this boxed-computer-game derivative. In an early nod toward embodied virtual reality, a team of four children were immersed in a computer-generated dungeon and tasked with finding their way out. It’s an intriguing cultural artifact of Britain’s early fascination with computers and the games they played, well worth a gander on YouTube.

The computer game of Knightmare, however, is less intriguing. Using the Captive engine, but featuring hand-crafted rather than procedurally-generated content this time around, it actually hews far closer to the Dungeon Master template than its predecessor. Indeed, like so many of its peers, it slavishly copies almost every aspect of its inspiration without managing to be quite as good — much less better — at any of it. This lineage has always had a reputation for difficulty, but Knightmare pushes that to the ragged edge, in terms of both its ridiculously convoluted environmental puzzles and the overpowered monsters you constantly face. Even the laddish staff of Amiga Format magazine, hardly a bastion of thoughtful design analyses, acknowledged that it “teeters on unplayably tough.” And even the modern blogger known as the CRPG Addict, whose name ought to say it all about his skill with these types of games, “questions whether it’s possible to win it without hints.”

Solo productions like this one, created in a vaccuum, with little to no play-testing except by a designer who’s intimately familiar with every aspect of his game’s systems, often wound up getting the difficulty balance markedly wrong. Yet Knightmare is an extreme case even by the standards of that breed. If Dungeon Master is an extended explication of the benefits of careful level design, complete with lots of iterative feedback from real players, this game is a cautionary tale about the opposite extreme. While it was apparently successful in its day, there’s no reason for anyone who isn’t a masochist to revisit it in ours.

Eye of the Beholder‘s dependence on Dungeon Master is, as the CRPG Addict puts it, “so stark that you wonder why there weren’t lawsuits involved.” What it does bring new to the table is a whole lot more story and lore. Multi-page story dumps like this one practically contain more text than the entirety of Dungeon Master.

None of the three games I’ve just described was available in North America prior to 1992. Dungeon Master, having been created by an American developer, was for sale there, but only for the Amiga and Atari ST, computers whose installed based in the country had never been overly large and whose star there dwindled rapidly after 1989. Thus the style of gameplay that Dungeon Master had introduced was either completely unknown or, at best, only vaguely known by most American gamers — this even as real-time blobbers had become a veritable gaming craze in Europe. But there was no reason to believe that American gamers wouldn’t take to them with the same enthusiasm as their European counterparts if they were only given the chance. There was simply a shortage of supply — and this, as any good capitalist knows, spells Opportunity.

The studio which finally walked through this open door is one I recently profiled in some detail: Westwood Associates. With a long background in real-time games already behind them, they were well-positioned to bring the real-time dungeon crawl to the American masses. Even better, thanks to a long-established relationship with the publisher SSI, they got the opportunity to do so under the biggest license in CRPGs, that of Dungeons & Dragons itself. With its larger development team and American-sized budget for art and sound, everything about Eye of the Beholder screamed hit, and upon its release in March of 1991 — more than half a year before Knightmare, actually — it didn’t disappoint.

It really is an impressive outing in many ways, the first example of its sub-genre that I can honestly imagine someone preferring to Dungeon Master. Granted, Westwood’s game lacks Dungeon Master‘s elegance: the turn-based Dungeons & Dragons rules are rather awkwardly kludged into real time; the environments still aren’t as organically interactive (amazingly, none of the heirs to Dungeon Master would ever quite live up to its example in this area); the controls can be a bit clumsy; the level design is nowhere near as fiendishly creative. But on the other hand, the level design isn’t pointlessly hard either, and the game is, literally and figuratively, a more colorful experience. In addition to the better graphics and sound, there’s far more story, steeped in the lore of the popular Dungeons & Dragons Forgotten Realms campaign setting. Personally, I still prefer Dungeon Master‘s minimalist aesthetic, as I do its cleaner rules set and superior level design. But then, I have no personal investment in the Forgotten Realms (or, for that matter, in elaborate fantasy world-building in general). Your mileage may vary.

Whatever my or your opinion of it today, Eye of the Beholder hit American gamers like a revelation back in the day, and Europe too got to join the fun via a Westwood-developed Amiga port which shipped there within a few months of the MS-DOS original’s American debut. It topped sales charts in both places, becoming the first game of its type to actually outsell Dungeon Master. In fact, it became almost certainly the best-selling single example of a real-time blobber ever; between North America and Europe, total sales likely reached 250,000 copies or more, huge numbers at a time when 100,000 copies was the line that marked a major hit.

Following the success of Eye of the Beholder, the dam well and truly burst in the United States. Before the end of 1991, Westwood had cranked out an Eye of the Beholder II, which is larger and somewhat more difficult than its predecessor, but otherwise shares the same strengths and weaknesses. In 1993, their publisher SSI took over to make an Eye of the Beholder III in-house; it’s generally less well-thought-of than the first two games. Meanwhile Bloodwych and Captive got MS-DOS ports and arrived Stateside. Even FTL, whose attitude toward making new products can most generously be described as “relaxed,” finally managed to complete and release their long-rumored MS-DOS port of Dungeon Master — whereupon its dated graphics were, predictably if a little unfairly, compared unfavorably with the more spectacular audiovisuals of Eye of the Beholder in the American gaming press.

Black Crypt‘s auto-map.

Another, somewhat more obscure title from this peak of the real-time blobber’s popularity was early 1992’s Black Crypt, the very first game from the American studio Raven Software, who would go on to a long and productive life. (As of this writing, they’re still active, having spent the last eight years or so making new entries in the Call of Duty franchise.) Although created by an American developer and published by the American Electronic Arts, one has to assume that Black Crypt was aimed primarily at European players, as it was made available only for the Amiga. Even in Europe, however, it failed to garner much attention in an increasingly saturated market; it looked a little better than Dungeon Master but not as good as Eye of the Beholder, and otherwise failed to stand out from the pack in terms of level design, interface, or mechanics.

With, that is, one exception. For the first time, Black Crypt added an auto-map to the formula. Unfortunately, it was needlessly painful to access, being available only through a mana-draining wizard’s spell. Soon, though, Westwood would take up and perfect Raven’s innovation, as the real-time blobber entered the final phase of its existence as a gaming staple.

Black Crypt may have been the first real-time blobber with an auto-map, but Lands of Lore perfected the concept. Like every other aspect of the game, the auto-map here looks pretty spectacular.

Released in late 1993, Westwood’s Lands of Lore: The Throne of Chaos was an attempt to drag the now long-established real-time-blobber format into the multimedia age, while also transforming it into a more streamlined and accessible experience. It comes very, very close to realizing its ambitions, but is let down a bit by some poor design choices as it wears on.

Having gone their separate ways from SSI and from the strictures of the Dungeons & Dragons license, Westwood got to enjoy at last the same freedom which had spawned the easy elegance of Dungeon Master; they were free to, as Westwood’s Louis Castle would later put it, create cleaner rules that “worked within the context of a digital environment,” making extensive use of higher-math functions that could never have been implemented in a tabletop game. These designers, however, took their newfound freedom in a very different direction from the hardcore logistical and tactical challenge that was FTL’s game. “We’re trying to make our games more accessible to everybody,” said Westwood’s Brett Sperry at the time, “and we feel that the game consoles offer a clue as to where we should go in terms of interface. You don’t really have to read a manual for a lot of games, the entertainment and enjoyment is immediate.”

Lands of Lore places you in control of just two or three characters at a time, who come in and out of your party as the fairly linear story line dictates. The magic system is similarly condensed down to just seven spells. In place of the tactical maneuvering and environmental exploitation that marks combat within the more interactive dungeons of Dungeon Master is a simple but satisfying rock-paper-scissors approach: monsters are more or less vulnerable to different sorts of attacks, requiring you adjust your spells and equipment accordingly. And, most tellingly of all, an auto-map is always at your fingertips, even automatically annotating hidden switches and secret doors you might have overlooked in the first-person view.

Whether all of this results in a game that’s better than Dungeon Master is very much — if you’ll excuse the pun! — in the eye of the beholder. The auto-map alone changes the personality of the game almost enough to make it feel like the beginning of a different sub-genre entirely. Yet Lands of Lore has an undeniable charm all its own as a less taxing, more light-hearted sort of fantasy romp.

One thing thing at least is certain: at the time of its release, Lands of Lore was by far the most attractive blobber the world had yet seen. Abandoning the stilted medieval conceits of most CRPGs, its atmosphere is more fairy tale than Tolkien, full of bright cartoon-like tableaux rendered by veteran Hanna-Barbara and Disney animators. The music and voice acting in the CD-ROM version are superb, with none other than Patrick Stewart of Star Trek: The Next Generation fame acting as narrator.

Sadly, though, the charm does begin to evaporate somewhat as the game wears on. There’s an infamous one-level difficulty spike in the mid-game that’s all but guaranteed to run off the very newbies and casual players Westwood was trying to attract. Worse, the last 25 percent or so is clearly unfinished, a tedious slog through empty corridors with nothing of interest beyond hordes of overpowered monsters. When you get near the end and the game suddenly takes away the auto-map you’ve been relying on, you’re left wondering how the designers could have so completely lost all sense of the game they started out making. More so than any of the other games I’ve written about today, Lands of Lore: The Throne of Chaos, despite enjoying considerable commercial success which would lead to two sequels, feels like a missed opportunity to make something truly great.

Real-time blobbers would continue to appear for a couple more years after Lands of Lore. The last remotely notable examples are two 1995 releases: FTL’s ridiculously belated and rather unimaginative Dungeon Master II, which was widely and justifiably panned by reviewers; and Interplay’s years-in-the-making Stonekeep, which briefly dazzled some reviewers with such extraneous bells and whistles as an introductory cinematic that by at least one employee’s account cost ten times as much as the underwhelming game behind it. (If any other anecdote more cogently illustrates the sheer madness of the industry’s drunk-on-CD-ROM “interactive movie” period, I don’t know what it is.) Needless to say, neither game outdoes the original Dungeon Master where it counts.

At this point, then, we have to confront the place where the example I used in opening this article — that of interactive fiction and its urtext of Adventure — begins to break down when applied to the real-time blobber. Adventure, whatever its own merits, really was the launching pad for a whole universe of possibilities involving parsers and text. But the real-time blobber never did manage to transcend its own urtext, as is illustrated by the long shadow the latter has cast over this very article. None of the real-time blobbers that came after Dungeon Master was clearly better than it; arguably, none was ever quite as good. Why should this be?

Any answer to that question must, first of all, pay due homage to just how fully-realized Dungeon Master was as a game system, as well as to how tight its level designs were. It presented everyone who tried to follow it with one heck of a high bar to clear. Beyond that obvious fact, though, we must also consider the nature of the comparison with the text adventure, which at the end of the day is something of an apples-and-oranges proposition. The real-time blobber is a more strictly demarcated category than the text adventure; this is why we tend to talk about real-time blobbers as a sub-genre and text adventures as a genre. Perhaps there’s only so much you can do with wandering through grid-based dungeons, making maps, solving mechanical puzzles, and killing monsters. And perhaps Dungeon Master had already done it all about as well as it could be done, making everything that came after superfluous to all but the fanatics and the completists.

And why, you ask, had game developers largely stopped even trying to better Dungeon Master by the middle of the 1990s?1 As it happens, there’s no mystery whatsoever about why the real-time blobber — or, for that matter, the blobber in general — disappeared from the marketplace. Even as the format was at its absolute peak of popularity in 1992, with Westwood’s Eye of the Beholder games selling like crazy and everything else rushing onto the bandwagon, an unassuming little outfit known as Blue Sky Productions gave notice to anyone who might have been paying attention that the blobber’s days were already numbered. This they did by taking a dungeon crawl off the grid. After that escalation in the gaming arms race, there was nothing for it but to finish whatever games in the old style were still in production and find a way to start making games in the new. Next time, then, we’ll turn our attention to the great leap forward that was Ultima Underworld.

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of April 1987, February 1991, June 1991, February 1992, March 1992, April 1992, November 1992, August 1993, November 1993, October 1994, October 1995, and February 1996; Amiga Format of December 1989, February 1992, March 1992, and May 1992; Questbusters of May 1991, March 1992, and December 1993; SynTax 22; The One of October 1990, August 1991, February 1992, October 1992, and February 1994. Online sources include Louis Castle’s interview for Soren Johnson’s Designer Notes podcast and Matt Barton’s interview with Peter Oliphant. Devotees of this sub-genre should also check out The CRPG Addict’s much more detailed takes on Bloodwych, Captive, Knightmare, Eye of the Beholder, Eye of the Beholder II, and Black Crypt.

The most playable of the games I’ve written about today, the Eye of the Beholder series and Lands of Lore: The Throne of Chaos, are available for purchase on GOG.com.)

If one takes the really long view, they didn’t, at least not forever. In 2012, as part of the general retro-revival that has resurrected any number of dead sub-genres over the past decade, a studio known as Almost Human released Legend of Grimrock, the first significant commercial game of this type to be seen in many years. It got positive reviews, and sold well enough to spawn a sequel in 2014. I’m afraid I haven’t played either of them, and so can’t speak to the question of whether either or both of them finally managed the elusive trick of outdoing Dungeon Master. ↩

source http://reposts.ciathyza.com/life-on-the-grid/

0 notes

Text

ANALYSIS -- PETER PARKER: SPIDER-MAN, VOL.2, #13 (January 2000)

SCRIPT: Howard Mackie

PENCILS: Lee Weeks

INKS: Robert Campanella

COLORS: Gregory Wright

LETTERS: Troy Peteri for RS & Comicraft

EDITORIAL: Ralph Macchio, Bob Harris (EIC)

PETER PARKER: SPIDER-MAN #13 is an interesting parallel to last week’s BATMAN: GOTHAM ADVENTURES #17. It was made at roughly the same time, and occupies a similar place in its series run (the series’ second years, after the look and feel of both books had been established). This leaves both issues to preform similar duties — not to open up new ground or bring everything to a close, but to keep the ongoing macronarrative afloat with exciting, well-made, meat and potatoes storytelling. Both series are secondary titles, rather that the AMAZING SPIDER-MAN or BATMAN books that serve as the flagship titles of their respective lines, and therefore they have a certain latitude to explore different stories those main books don’t or can’t. And like Scott Peterson, Tim Levins and Terry Beatty, Howard Mackie, Lee Weeks and Robert Campanella are lean, dynamic storytellers with intimate, hard-earned understanding of the technology of comics.

The differences are few, but significant. GOTHAM ADVENTURES is a publication explicitly targeted at younger readers, while PETER PARKER is aimed at the slightly older mainstream Marvel audience — its storytelling is meant to be denser and more interconnected to ongoing story threads. GOTHAM ADVENTURES is drawn from animation-informed character models, while PETER PARKER is drawn in the more illustrative Marvel house style. Which brings us to a final, somewhat abstract but sometimes very important, difference; GOTHAM ADVENTURES is a DC Comic, where PETER PARKER is very much a Marvel Comic.

With that, let’s get into 2000’s PETER PARKER: SPIDER-MAN #13 — “LIVING IN OBLIVION!”

And please, feel free to check me on any mistakes I might have made, add your own commentary, or share similar examples of good comics done well.

PETER PARKER: SPIDER-MAN #13 and all characters contained therein are property of Marvel Comics, reproduced here solely for educational purposes.

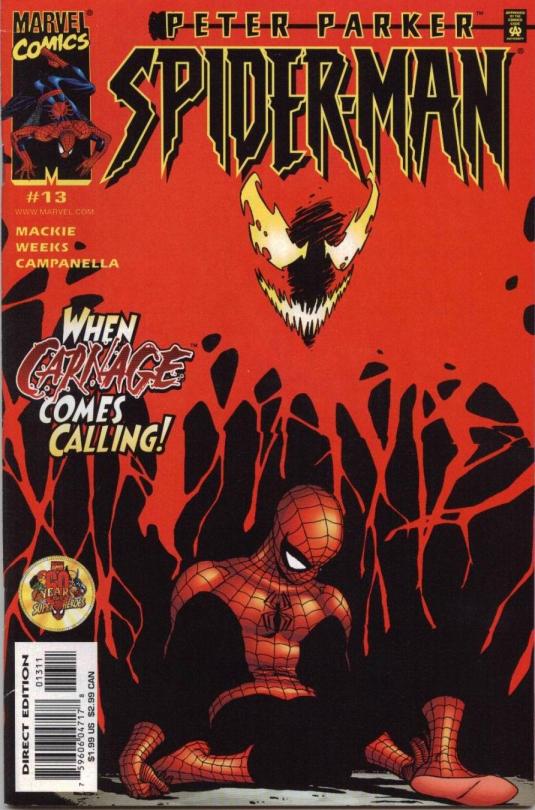

COVER

This cover is not only powerfully simple, it also sets us up for a gutpunch visual at the end of the issue. Note the great anatomy on the crumpled Spider-Man at the bottom, apparent even with half of his costume reduced to matte black. The sketchy black in the Carnage face is a little messy for my tastes, but the face would’ve been too insubstantial without it. Maybe if the Face had been expanded to huge, nightmarish Jack O’Lantern proportions, it could have stood better on its own.

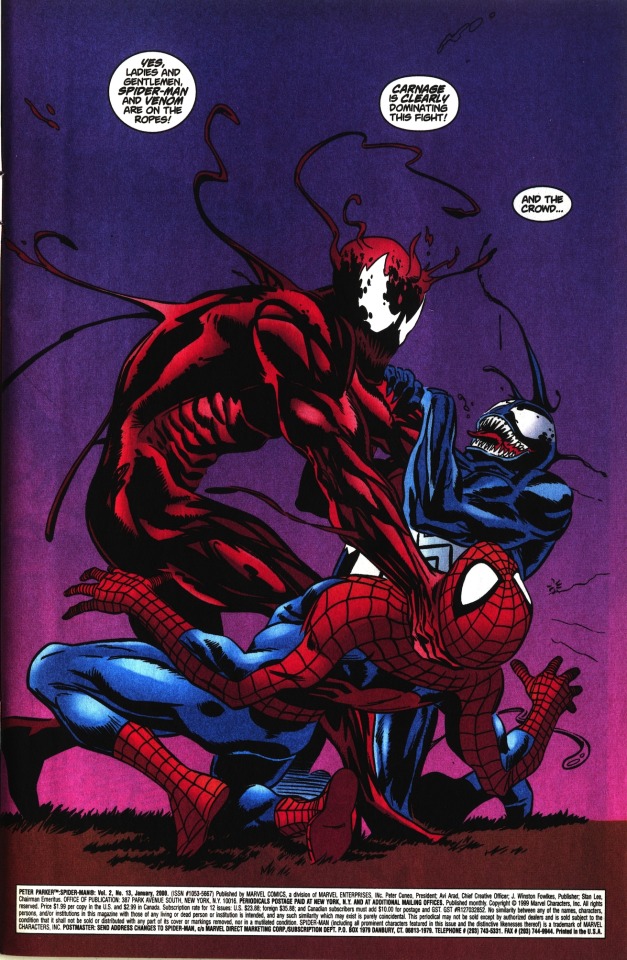

PAGE ONE

This opening splash is great. The dialogue clearly introduces all three characters by name, and the staging immediately shows how powerful Carnage is. The absence of background is compelling — we want to know who’s saying these things, and to see how Spider-Men gets out of this mess. The barely hinted-at grass they’re kneeling in give the scene just enough of a sense of place to make the it feel real.

PAGE TWO-THREE

POW! What a followup splash! Only it isn’t actually a splash, is it — it’s a five-panel page, expanded to twice its normal size by stretching it across the real estate of a double page splash. Such a power move... you can only pull this kind of thing off every once in a while before it gets gimmicky, and they decided to come out the gate swinging with it. The way this forces you to physically rotate the book even ads impact to Carnages laterally sweeping blow, which your eye immediately goes to, since it’s aligned with the fold of the page. Weeks made sure the blow wan’t QUITE centered on the page, however, since that would make it disappear into the fold, defeating the whole point. With one move, Carnage knocks Venom away from us while sending Spider-Man sprawling towards us, making him seem even stronger. The double-sized page also allows the scene-setting panels one and five, which would come across as tiny on a normal page, to seem wide and immersive. We also get our first close-up of the issue in panel two — Carnage, establishing this as HIS show.

The one weakness of the double-page format is actually evidenced in my scattered commentary above — because your eye is drawn immediately to the center of it, you end up reading the page in pieces rather than the top to bottom, left to right manner pages are drawn to facilitate. Fortunately, the action on this page is really less sequential than it is scene-setting, so nothing is really lost. This time.

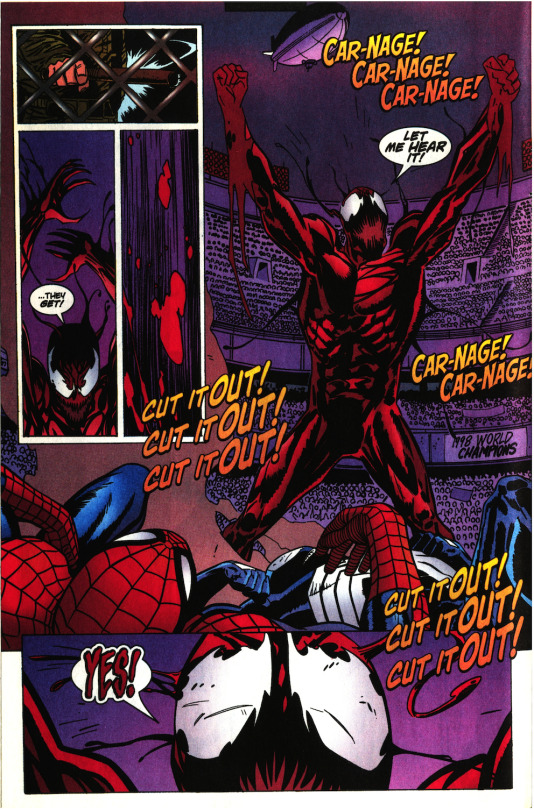

PAGE FOUR

I love the little circuit of panels one though three. Introducing the incongruous element of the baton hitting the fence in panel one sticks in your reading flow, twisting your understanding of the space and adding to the weird atmosphere of the scene. More glamour shots and close-ops of Carnage — we start getting the inkling that this might not be his show so much as his fantasy.

PAGE FIVE

Panel one repeats the pose of the close-up in the last panel of the previous page, indicating the shift from fantasy to reality. We now see the face was Carnage’s — aka Cletus Kasady’s — weird tech-inflected jail cell. Weeks consistently stages Cletus in the background, making him smaller (and implicitly weaker) than the guard at all times. This does a couple of things for us; 1) it shows us the cruelty of the guard in charge of Cletus, giving us a nice mini-boss for his part of the story. 2) It catches us up on why Cletus doesn’t have his alien costume anymore (and if you didn’t know what that was when you picked up the comic, you can intuit everything you need to know from what you saw in his fantasy). 3) It establishes an enmity between Carnage and Venom, which may come into play later. And finally, 4) even without his costume, Cletus Kasasy is clearly dangerous, unhinged, and patient.

PAGE SIX

This page is… muddy. Weeks and Campanella do a good job of setting up the geography of May’s apartment, but Wright’s colors make it difficult to delineate between middle and background. The BING of the elevator is way too dark, disappearing into a tangent with the ceiling. Jill and Arthur aren’t well established until we see them in panel five, which makes Jill’s crying seem even more sudden and forced, and the phone-drop in panel six is really over the top. It’s possible the script for this page was re-worked after the art came in for some reason or another, but the end result is just not that great. Totally kills the momentum from the previous pages.

Now, you shouldn’t point out a problem if you don’t have a solution, so here’s an easy, non-structural fix for at least some of this: put the phone in May’s hand in panel two, and then move May’s first two lines from panel three to panel two. In script form, it might look like this:

PANEL TWO — MAY answers the phone, glancing over at the door as she hears the elevator bing.

MAY: Hello! Parker Residence. May Parker Speaking.

MAY: Oh my… someone’s coming up in the elevator, too!

MAY: Could you hold on for one moment, please?

PANEL THREE — JILL and ARTHUR STACY enter the apartment. MAY looks over at them as they enter, covering the mouthpiece of the phone.

MAY: JILL and Arthur STACY! What a pleasant surprise. I’ll be with you in a second. I just answered the phone and—

I think this is more natural, and gives the vaguely useless panel two some activity. It also makes the whole point of panel three “Jill and Arthur enter the room,” which does a better job of introducing them.

PAGE SEVEN

Weeks employs one of my favorite tricks here — conveying the physical freedom of a character by having them slightly overlap the panel boarders. You can see it in Spider-Man’s figures in panel two and four. Four is especially effective — having Spidey partially outside the panel helps give us the feeling that he’s dropping into a scene in progress. Note also how Weeks slowly brings Spidey closer to us throughout panels one and three, ending in a nice juicy close-up. We’re nearly a third of the way through the issue and this is the first time we’ve actually met our hero, so this is a good way to get acquainted with him this late in the game. Some nice relatable internal thought also helps us get on the same page as the titular Peter Parker; imagine this scene without any lettering and see how cold and remote our faceless hero becomes.

PAGE EIGHT

Mackie give us a fun superhero take on the “daydreaming about your vacation at work” shtick. Weeks maintains a nice rightwards line of motion from Spidey’s dive in panel one, tearing off the door in panel two, the look over the shoulder and down the right-reaching arm in panel three, and then changing course by having Spidey run towards us in panel four, away from the rightward trajectory towards danger in the first three panels. An annotated version of the page to demonstrate what I’m talking about, just in case I’m describing it clumsily:

Spidey’s lean in the last panel is dynamic as hell.

PAGE NINE

The large black expanse of the bridge might seem like a waste of space at first, but it’s actually a way for Weeks and Campanella to stage the teetering bus high up in the panel and page, helping to sell the precarious verticality of the soon-to-fall vehicle. It’s kind of a static panel, which makes me think there might have been some more rubble and activity in the pencils that got lost in the inks. The ‘Department of Corrections’ label in panel four is a nice, natural way to establish the prisoner transport element of the scene without relying solely on the expository dialogue in panel five. It sets us up for the revelations of the rest of the scene and keeps the plot moving — another way in which this sequence is playing catch-up for being so relatively late in the issue. It’d be nice if Wright had used different colors between the uniforms of prisoners and the guards (established in the Kasady scene as grey and green, respectively).

PAGE TEN

The bus falling and exploding is a cool, kinetic way to put a button on this scene. I’ve been criticizing Wright’s colors so far, but he does dynamite work on this page. I love the blue figures in front of the brilliant blaze in panel three, as well as the glowing reverse angle on Spider-Man in panel four. Some heavy, but not too heavy, symbolism in panel five — the looming presence of Carnage hovering over a sleepy, unsuspecting city.

PAGE ELEVEN

This page is a fairly flat “people in a room talking in cliches” scene, but Weeks keeps it alive by changing up his camera angles, going from wide shots to close ups, and employing another favorite trick of mine by dropping out the background and panel borders in the panel three group shot. Note the use of the spiky houseplants as the visual shorthand for May’s apartment.

PAGE TWELVE

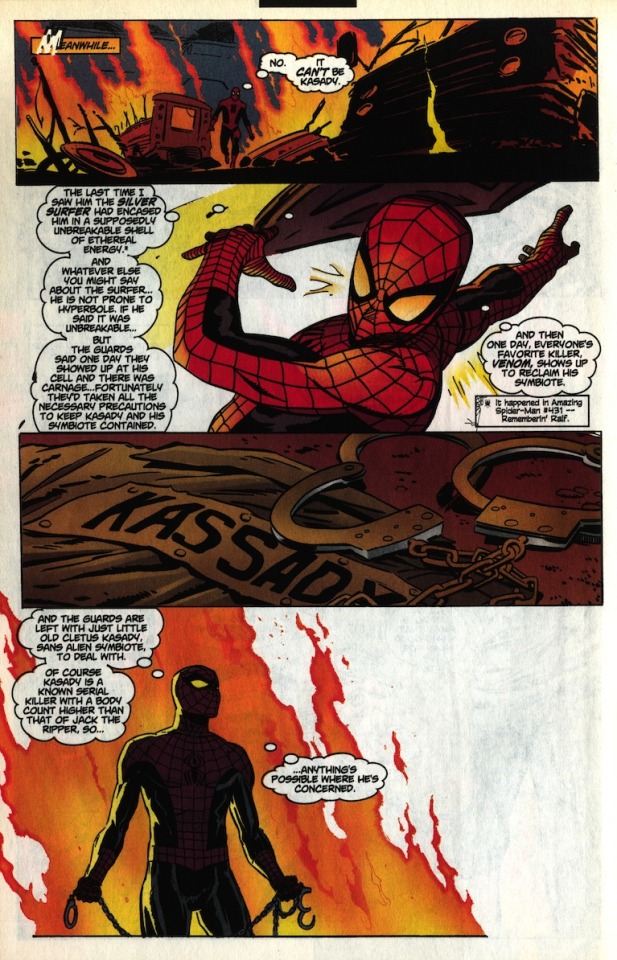

Weeks and Campanella dwarf Spidey with flaming wreckage in panel one, selling the pressure and anxiety he feels at the prospect of Kasady’s escape. We cut to a relatively close shot of Spidey in panel two to smooth the transition to an extreme close up of Kas(s)ady’s empty prison uniform and cuffs in panel three. Dropping out the background and panel boarder in panel four emphasizes the immensity of the danger Spider-Man, and New York by extension, now faces.

(Trivia: Jack the Ripper’s bodycount is generally accepted to be a horrible -- yet ultimately modest in the grand scope of comic book super villains -- five.)

PAGE THIRTEEN

The close-in anatomy shots across the first four panels builds to a good full-body reveal in panel five. I’m not sure who the uniformed guys on the ground are supposed to be; I guess they’re cops? I can’t see a hardware store having armed security on hand. It’s just weird to use dead cops solely as serial-killer-escape potpourri. It makes the scene feel fake. They don’t even need to be there — the fact that the knife blade is the only part of Kasady that isn’t red indicates he’s covered entirely in paint, not blood, and it’s not like he couldn’t just be ranting to himself. Personal peev, and anyway, it’s very well drawn. I can’t find any one person “J.P. Bradford” might be. Who knows? Maybe it’s Lee Week’s brother-in-law.

PAGE FOURTEEN

Man, maybe I’m missing some context from other Spider-Man comics of the time, but these Aunt May scenes sure feel like a whole lot of nothing. Waiting by the phone in a well-lit apartment is just about the least dynamic thing you can put on a page. She’s literally napping in this scene. That said, panel three is really well drawn, and Weeks nicely ratchets up the intimacy in the last two panels by sacrificing some real estate on either side.

(These Aunt May scenes are the exact reason for Wally Wood’s 22 Panels That Always Work.)

PAGE FIFTEEN

Weeks easily indicates that the vehicle Kasady jumps on in panel two is a limousine just by including those vertical ornaments in between the windows. Wright leaves the blue in his eyes, reminding us he’s just a crazy guy in paint right now, and not the alien death monster he’s still claiming to be. See also: the hair in his face, the wrinkles on his forehead, his toenails.

PAGE SIXTEEN

Probably just a coincidence, but Kasady’s slash in panel one follows the same motion as Carnage’s sweep on the page two-three double page. Very well-drawn Kingpin here, his intelligence indicated with subtle hand motions as opposed to Kasady and turtleneck goon’s broad pantomime.

PAGE SEVENTEEN

Panel two gives us another good look at the environment, making the following action feel more grounded and understandable. It’s generally a good idea to cut to a wide shot at the start of an action scene. Meanwhile, Weeks continues to be a stellar anatomist.

PAGE EIGHTEEN

Including some onlookers in panel one helps sell the moment of Spidey getting blindsided by Kasady. Bit odd that Spidey couldn’t evade a manhole cover when he usually dodges bullets, but that’s a nitpick. The creative team keeps the fight personal by cutting to the closeup in panel two — this sequence is closing out Kasady’s story from the opening of the issue, and this closeup helps keep it his story. For this page, at least.

PAGE NINETEEN

Now the tide turns against Kasady, as it must, and we switch back to Spider-Man’s internal thoughts. Spidey goes from a prop in Kasady’s story to Kasady becoming a prop in his.

I gotta say, Cletus’ short-lived reign of terror leaves me pretty cold. Despite the work done to establish his captivity and his enmity with the blonde guard on page five, we never get any real payoff on it. His escape happens in between pages, and the guard is never seen again (it’s possible he’s supposed to be the guard Spider-man talks to on page nine, but even that’s some poor followup). For all the great buildup of Cletus Kasady as an enemy to make Spider-Man quake in his webs, the confrontation we ultimately get fails to live up to it. It’s shame, because as far as the Carnage stuff went, up to page twelve we were really cooking.

The page ends with this gorgeous montage panel — Venom huge (and possibly even diegetic) in the foreground, while the Kingpin looms in the sky (definitely non-diegetic) like a malevolent blue moon. Spidey’s tiny form shows his childish declaration of independence to be just that; there’s larger forces in play than the desires of Peter Parker.

PAGE TWENTY

Speaking of Peter Parker, here he is at last. It may even be intentional that Peter’s been spending the whole issue as Spider-Man, unable to even end his thoughts without a crisis coming up. Weeks indicates Peter’s feeling of independence of personal empowerment by steadily increasing his size throughout the three panels, culminating in him literally clenching the Spider-Man mask in his hand, symbolically getting a hold of his life. Or so he thinks.

PAGE TWENTY ONE

Lot going on with this page, all of it good. Peter’s graceful, playful jump into the stairwell shows us his frame of mind as he heads into this heavy scene — knowing he’s in a good place will make his imminent descent into a bad place all the more crushing. As Peter enters the apartment, Wright does a good job of drawing our eye to Aunt May in the background with a warm yet menacing gold-orange light. Since we more or less know what Peter’s heading into, Weeks helps us feel the tension of his uncertainly by keeping us close to him in panel five. Great use of black negative space in panel six. Note that the action in the last three panels happens along the same axis, helping to build the tension further.

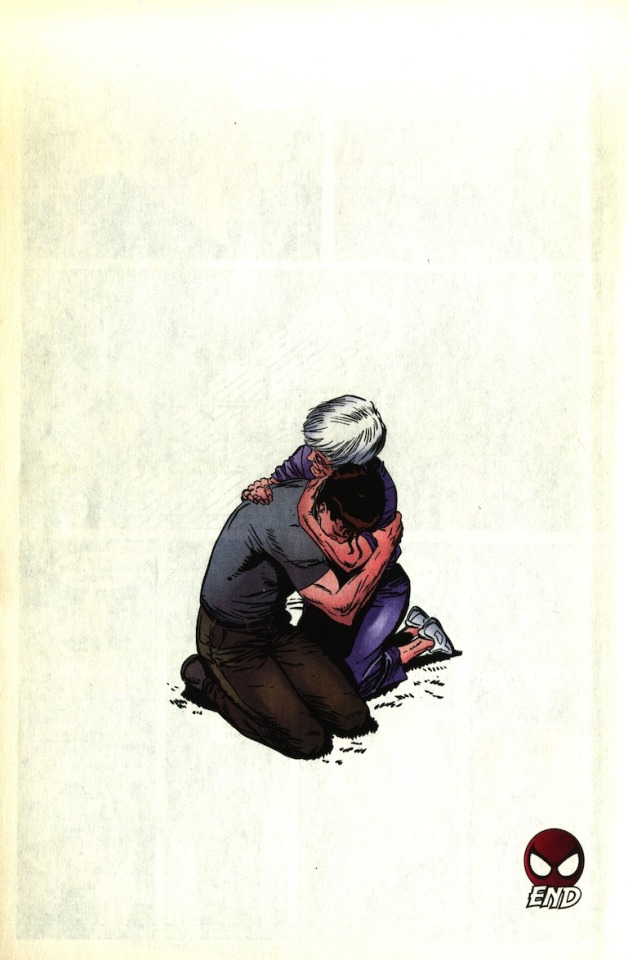

PAGE TWENTY TWO

Huge, empty splash page; they’re in shock, in pain, all alone, with only each other to hold onto. Like I said at the beginning, I think the cover thematically connects to this final splash page — the dark and bloody Spider-Man moment setting us up for the eventual sucker punch of the big empty Peter Parker moment.

Overall: A very well-drawn comic that suffers from a script that maybe relies a little too much on genre conventions and ultimately fails to pay off on its imaginative first half, as well as a few missed coloring opportunities. A lot to like from all parties involved, though.

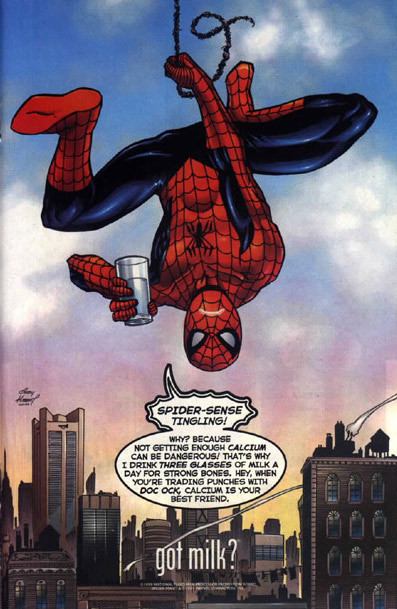

At the end of all this, I’d be remiss if I didn’t include the back cover, which is a stone cold comic book classic:

Unimpeachable.

0 notes