#eighteenth century paintings

Text

François Boucher, The Dovecote

0 notes

Text

Louise Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755-1842): Portrait of the Duchesse de Guiche, née Louise Françoise Gabrielle Aglaé de Polignac (1784) (via Sotheby’s)

#Louise Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun#Louise Elisabeth Vigee Le Brun#women artists#women painters#art#painting#eighteenth century#portrait#french painters#Duchesse de Guiche

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

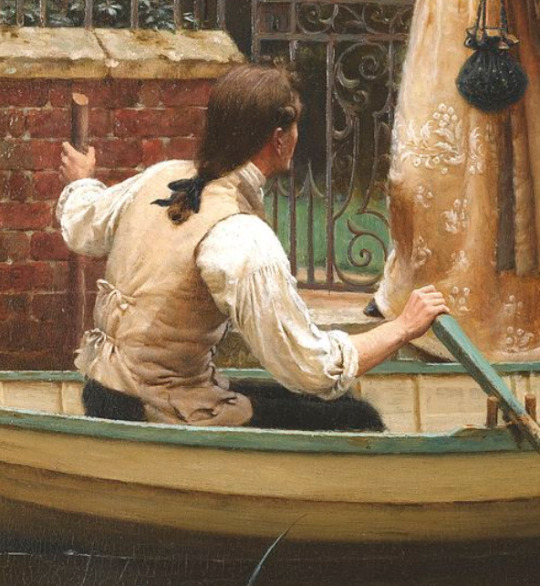

ideal gender: 1790s-1810s men in an edmund blair leighton painting...

#this guy paints knights just fine but these fellows are the real mvps#'specially the fellow on the right here...#while we are here I have Thoughts on the middle painting ('my next-door neighbour' 1894) beyond this too#the lady looks very much of the period it was painted on first glance while the gent is Solidly nineteenth-century-does-eighteenth-century#and with that and the way that she's in sunlight and pinks and golds while he's in shadows and grey made me think there was some kind of#ghost thing going on!! and I am still not entirely sure that there is not!#'courtship' 1903 (on the right) is definitely my favorite of these three (the golden light! the way he's hanging on the railing!)#but that middle one oh how I have Thoughts about it

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Delicate Matter: An excerpt

What is the relationship between the exquisite delicacy of art and the debased flimsiness of disposable commodities? Few people today would deny that a distinction exists between these two forms of perishability. The Louvre may sit atop an enormous mall, but no one would confuse the art in the galleries with the fashionable goods in the basement shops. A world of difference separates, for example, the delicate brushstrokes of Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s paintings from the latest season of trinkets and fragrances on display downstairs in the Fragonard perfumery. A painting by Fragonard such as The Warrior’s Dream of Love may, like perfume, conjure evanescent pleasure, but the museum ensures that we regard the fragility of the painting itself as much more than an expression of commercial ephemerality. When the museum’s informational brochure cautions us that “works of art are unique and fragile” and that “touching, even lightly” can cause irreparable harm, the warning makes no reference to market worth. The significance of art’s fragile materiality goes unspecified, but we are told that whatever unnamed essence it contains “must be preserved for future generations.” If the perishability of a commercial product reflects the fleetingness of fashion, then the fragility of art here stands for the opposite, representing something whose value transcends time.

This book is devoted to disputing such a neat division between the delicacy of art and the ephemerality of consumer goods. More specifically, it is a book about the fragile and decaying objects from eighteenth-century France that first prompted people to wish this slippery distinction into existence. The period witnessed an unprecedented proliferation of materially unstable art. Some artists made objects that were fragile by design, creating enormous pastel portraits that were vulnerable to the slightest touch, or constructing spectacularly breakable sculptures from attenuated pieces of clay. For other artists, impermanence was an unintended by-product of a search for novel and spontaneous effects. The Warrior’s Dream of Love provides a telling example from this second category. Until the painting’s restoration in 1987, it was considered unworthy of exhibition because it was in such poor condition. The painting’s decay stemmed from the process of its production: Fragonard employed an unusual quantity of a drying agent when painting it, which soon caused broad cracks to form across its surface. The use of these siccative oils was a notorious problem among painters at the time, so much so that the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture had issued warnings about it in the decades before Fragonard produced the picture. These ingredients allowed artists to work more quickly and to produce atmospheric effects, but they resulted in damage within a matter of years, rendering paintings nearly unrecognizable.

Such techniques developed in tandem with broader changes in the artistic economy. The eighteenth century was a pivotal moment in the history of the art market: private collections grew in both number and size, art increasingly changed hands at auction, and art dealers acquired a new professional status. These commercial developments subjected art to competing temporal pressures. On the one hand, the commodification of art led to a new concern for issues of conservation. Collectors prized art’s materiality as the bearer of an artist’s autographic touch and as a source of sensory pleasure, which meant that art’s value became intertwined with its physical condition. On the other hand, the market created short-term incentives that were at odds with the expectation of durability. Artists had to work quickly to make a living and to keep up with trends in taste, which could lead them to take technical shortcuts. In addition, the demand for sensuous surfaces and novel techniques among collectors pushed artists to become more experimental, sometimes causing them to sacrifice permanence in the process. The painter Jean-Baptiste Oudry warned about this tendency in a 1752 lecture to the Academy, explaining that artists had been led astray in their search for beguiling surface effects: “The seduction that it achieves passes like a dream, and all this beautiful work turns yellow in no time at all.”

A Delicate Matter: Art, Fragility, and Consumption in Eighteenth-Century France is available for pre-order from Penn State University Press. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09528-8.html

#Painting#Art#Art History#Europe#European Art#Eighteenth Century#Eighteenth Century Art#18th Century#18th Century Art#Jean-Honoré Fragonard#Fragonard#French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture#The Warrior's Dream of Love#PSU Press#Penn State University Press

0 notes

Text

Had a pretty fun time reading this blog post about this eighteenth century painting!

0 notes

Text

Self Portrait in a Straw Hat

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755 - 1842)

1782

(Source: The National Gallery)

0 notes

Text

For the past few centuries, immigrants have brought with them their knowledge of European folk art painting to decorate furniture, walls, and accessories for various types. This particular type of decoration, called rosemaling, evolved in Scandinavia during the early part of the eighteenth century and is, perhaps, the most exuberant of all forms of folk art.

The Good Housekeeping Complete Guide to Traditional American Decorating, 1982

#vintage#vintage interior#1980s#80s#interior design#home decor#kitchen#dining room#wallpaper#stencil#rosemaling#Scandinavia#folk art#European#style#traditional#American#home#architecture

704 notes

·

View notes

Text

William Wood - Joanna de Silva (1792)

Painted at a time of rapidly expanding British colonialism, this is an exceptionally rare independent likeness of an identifiable Indian woman by an eighteenth-century English artist. As identified by her portrait’s inscription, Joanna de Silva was a native of Bengal, in eastern India, and was employed as a nursemaid in the family of an officer with the British East India Company. She later accompanied an orphaned daughter of the family to England, where she sat for this portrait. The sitter wears the delicate Indian textiles that were sought after around the globe in the 1700s. (source)

242 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day Dress

c.1872

France

The 1870s was a period of marked romanticism and whimsy in fashionable dress. Much like the picturesque paintings of Renoir that depict such confectionary creations, both day and evening gowns were highly ornamented and often executed in delicate, feminine textiles. Though eveningwear was marked by décolleté necklines and lavish silk satins and taffetas, day dresses were made more modest with austere fabrics like cotton or wool. While many women owned walking and traveling dresses which afforded slightly greater moveability, also quite common was the summer day dress that was to be worn to an afternoon tea or reception.

This garment, emblematic of warm weather day dresses of the period with its sheer printed cotton and delicate lace trim, is a particularly pristine example, and notable for its clear revival of eighteenth–century aesthetic sensibilites. The late nineteenth century, abetted by the luxury and progress of the Industrial Age, recalled distinctly, both in its textiles and in the etiquette that surrounded fashionable dress, the notorious material excesses of the third quarter of the eighteenth century. The wealthy classes of the late–nineteenth–century showed a particular respect for the formalities of fashion. While their garments were not nearly as ornamental and their entertaining circles not as elitist, the decorative effects of late nineteenth century afternoon reception dresses such as this one unarguably echoed the lavishness of the eighteenth–century gown, most notably here in the sleeve and neckline.

The MET (Accession Number: 2003.426a, b)

#fashion history#historical fashion#day dress#1870s#belle epoque#19th century#bustle era#1872#floral#summer#flower print#white#pink#france#the met#popular

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Julian to Alec

Dear Alec,

Hello from Chiswick! I’m sure Magnus has been keeping you up-to-date on the adventures we’ve been having here at Blackthorn Hall. We’ve been making progress, slow as it is, but the place still feels very far from being a house I or my family would want to live in. Except Dru, who claims she’d rather keep it cursed for the ambience (not that she’s been here yet.)

All of that is to say I suggest you thank the Angel every day that Tatiana Lightwood married a Blackthorn and this house is our problem and not yours. Anyway, you get the update this time instead of M.; you’ll see why soon.

Our search for the objects that hold the Curse of Tatiana continue! We’ve run out of objects that Rupert has any inkling about, which means we have gotten into the ley-line maps. I can hear Magnus groaning from here as you read this to him. Yes, Eighteenth-century ley-line maps, second only to ancient Babylonian star charts for their ease of reading and understanding. You can tell Magnus he can stop putting his coat on, though, because we got in touch with Ragnor Fell asked him to come from the Scholomance to help us. I suspect Ty harassed him until he agreed (though I have no proof) but he was polite enough about it. Polite for Ragnor, I mean.

The ley-lines suggested two possible locations where something important might be kept—a Downworlder gentleman’s club and a church, both in central London. We decided to start with the church, which is named St. Mary Abchurch. (Am I wrong or are British names weirdly silly sometimes? Emma immediately started calling it “St. Church von Church,” and now that’s the only way I can think of it.)

Anyway, St. Church the Churchiest is a not-huge red brick church on Abchurch Lane (funny how that works out). We took the train and then the Tube to get there, which may have been the most complex part of the day, just figuring out how to navigate the whole weird mundane system. The church was pretty quiet and empty—it was the middle of the afternoon and there were a handful of tourists, but I don’t think it’s well-known so we didn’t have to worry. We weren’t glamoured, but nobody paid any attention to us anyway. Tattoos are pretty common in London.

We walked the whole church, pretending to gaze thoughtfully at the memorials and the paintings on the inside of the dome and so on while waving the Sensor around as much as we could and waiting for it to respond.

And it was not responding. Covering the whole church didn’t take all that long; like I said, it’s not huge.

Emma pointed out that just because the church was on a ley-line in London didn’t mean Tatiana had necessarily left anything there, since there are way more ley-lines than objects we’re looking for. And she’s right—we’re assuming Tatiana didn’t break into some mundane’s house on the same ley-line and leave anything there, but I guess she might have. It would have been a very strange thing to do, but whatever else we’ve learned about Tatiana we do feel pretty confident she was a strange one.

We did get a break, though—just before we were about to leave Emma went to look at a display for visitors on the wall about the history of the church. There was a whole bit about how in the Second World War the dome of Abchurch St. Abchurch was hit by a bomb during the Blitz of London (Tessa was an nurse during the Blitz — did you know that?). Most of it was just about the dome and how it was broken and how long it took to fix and who fixed what, but at the end there was a bit about how for safekeeping a number of the church’s more valuable possessions were removed. There was an artist’s rendering of those possessions—I guess most of them didn’t end up coming back to the church—and now at last you get to find out why I’m writing to you and not Magnus!

Right at one end of the illustration was a pair of candlesticks and on the candlesticks, a very familiar symbol indeed. Flames—and not just flames, but the same flames you’ll find on that family ring of yours. And also a big script “L.”

So, any chance you or Isabelle recognize these? Did they get taken out of the church by a Lightwood, or returned to one? I know it’s a long shot but it seems like it would be too big a coincidence for a pair of Shadowhunter candlesticks to randomly be in St. Mary Abchurch. Let me know if the candlesticks ring any bells for you or Izzy and give our love to the kiddies!

Julian

#Secrets of blackthorn hall#sobh#julian blackthorn#emma carstairs#alec lightwood#not magnus#The Blitz!#dru blackthorn

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, A Young Woman With a Birdcage

1 note

·

View note

Text

Marie Thérèse Vincent de Montpetit (French, 1774-1837): Portrait of Mademoiselle Lange (1794) (via Sotheby's)

#Marie Thérèse Vincent de Montpetit#Marie Therese Vincent de Montpetit#women artists#women painters#art#painting#eighteenth century#portrait#clothes#french painters

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fathers as nurturers during the Napoleonic era

Portrait of Monsieur Gaudry giving his daughter a geography lesson, 1812, Louis-Léopold Boilly

The Gaudry portrait is even more a portrayal of “the good father” than a lesson in political geography. The painting provides evidence of a reorientation of the father’s role within the family that had taken place from the eighteenth to the nineteenth centuries. In her study of archetypal family structures during the Revolutionary period, Lynn Hunt traces “the rise and fall of the good father” and his eventual replacement, as an ambivalent figure, by republican fathers “who were now officially depicted as friendly, supportive, and interested in their children.” While the gradual transformation of the king into a good father began before the Revolution (as manifested in the portrait of Louis XVI, and not a tutor, instructing his son in geography), it was not until the Napoleonic period that a positive image of paternalism was explicitly rehabilitated, as Boilly’s commission for a portrait of the yet-childless Napoleon as père de famille so clearly indicates. In the meanwhile, children assumed new importance as the affective center of gravity in representations of families, a shift that is indicated by the painting’s focus on the demure Mlle Gaudry. Rather than reading the Gaudry portrait in twentieth-century terms, as an expression of “unusual sensitivity and psychological insight,” Boilly’s portrayal of an affectionate and respectful relationship between father and daughter is better understood as conforming to a new social construction of the family that came to the fore during the Napoleonic period, in which fathers assumed new roles as nurturers or guides.

Source: The Art of Louis-Léopold Boilly: Modern Life in Napoleonic France, Susan Siegfried, pp, 115

#Louis-Léopold Boilly#Boilly#The Art of Louis-Léopold Boilly: Modern Life in Napoleonic France#Susan Siegfried#Siegfried#napoleon#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon bonaparte#first french empire#french empire#19th century#history#art#art history#history of art#social history#the geography lesson#geography#genre art#neoclassical#Neoclassicism#Monsieur Gaudry#France#french revolution#napoleonic France#French art#my pic#my pics

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coral today is an icon of environmental crisis, its disappearance from the world’s oceans an emblem for the richness of forms and habitats either lost to us or at risk. Yet, as Michelle Currie Navakas shows in her eloquent book, Coral Lives: Literature, Labor, and the Making of America, our accounts today of coral as beauty, loss, and precarious future depend on an inherited language from the nineteenth century. [...] Navakas traces how coral became the material with which writers, poets, and artists debated community, labor, and polity in the United States.

The coral reef produced a compelling teleological vision of the nation: just as the minute coral “insect,” working invisibly under the waves, built immense structures that accumulated through efforts of countless others, living and dead, so the nation’s developing form depended on the countless workers whose individuality was almost impossible to detect. This identification of coral with human communities, Navakas shows, was not only revisited but also revised and challenged throughout the century. Coral had a global biography, a history as currency and ornament that linked it to the violence of slavery. It was also already a talisman - readymade for a modern symbol [...]. Not least, for nineteenth-century readers in the United States, it was also an artifact of knowledge and discovery, with coral fans and branches brought back from the Pacific and Indian Oceans to sit in American parlors and museums. [...]

---

[W]ith material culture analysis, [...] [there are] three common early American coral artifacts, familiar objects that made coral as a substance much more familiar to the nineteenth century than today: red coral beads for jewelry, the coral teething toy, and the natural history specimen. This chapter is a visual tour de force, bringing together a fascinating range of representations of coral in nineteenth-century painting and sculptures.

With the material presence of coral firmly in place, Navakas returns us to its place in texts as metaphor for labor, with close readings of poetry and ephemeral literature up to the Civil War era. [...] [Navakas] includes an intriguing examination of the posthumous reputation of the eighteenth-century French naturalist Jean-André Peyssonnel who first claimed that coral should be classed as an animal (or “insect”), not plant. Navakas then [...] considers white reformers, both male and female, and Black authors and activists, including James McCune Smith and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and a singular Black charitable association in Cleveland, Ohio, at the end of the century, called the Coral Builders’ Society. [...]

---

Most strikingly, her attention to layered knowledge allows her to examine the subversions of coral imagery that arose [...]. Obviously, the mid-nineteenth-century poems that lauded coral as a metaphor for laboring men who raised solid structures for a collective future also sought to naturalize a system that kept some kinds of labor and some kinds of people firmly pressed beneath the surface. Coral’s biography, she notes, was “inseparable from colonial violence at almost every turn” (p. 7). Yet coral was also part of the material history of the Black Atlantic: red coral beads were currency [...].

Thus, a children’s Christmas story, “The Story of a Coral Bracelet” (1861), written by a West Indian writer, Sophy Moody, described the coral trade in the structure of a slave narrative. [...] In addition, coral’s protean shapes and ambiguity - rock, plant, or animal? - gave Americans a model for the difficulty of defining essential qualities from surface appearance, a message that troubled biological essentialists but attracted abolitionists. Navakas thus repeatedly brings into view the racialized and gendered meanings of coral [...].

---

Some readers from the blue humanities will want more attention, for example, to [...] different oceans [...]: Navakas’s gaze is clearly eastward to the Atlantic and Mediterranean and (to a degree) to the Caribbean. Many of her sources keep her to the northern and southeastern United States and its vision of America, even though much of the natural historical explorations, not to mention the missionary interest in coral islands, turns decidedly to the Pacific. [...] First, under my hat as a historian of science, I note [...] [that] [q]uestions about the structure of coral islands among naturalists for the rest of the century pitted supporters of Darwinian evolutionary theory against his opponents [...]. These disputes surely sustained the liveliness of coral - its teleology and its ambiguities - in popular American literature. [...]

My second desire, from the standpoint of Victorian studies, is for a more specific account of religious traditions and coral. While Navakas identifies many writers of coral poetry and fables, both British and American, as “evangelical,” she avoids detailed analysis of the theological context that would be relevant, such as the millennial fascination with chaos and reconstruction and the intense Anglo-American missionary interest in the Pacific. [...] [However] reasons for this move are quickly apparent. First, her focus on coral as an icon that enabled explicit discussion of labor and community means that she takes the more familiar arguments connecting natural history and Christianity in this period as a given. [...] Coral, she argues, is most significant as an object of/in translation, mediating across the Black Atlantic and between many particular cultures. These critical strategies are easy to understand and accept, and yet the word - the script, in her terms - that I kept waiting for her to take up was “monuments”: a favorite nineteenth-century description of coral.

Navakas does often refer to the awareness of coral “temporalities” - how coral served as metaphor for the bridges between past, present, and future. Yet the way that a coral reef was understood as a literal graveyard, in an age that made death practices and new forms of cemeteries so vital a part of social and civic bonds, seems to deserve a place in this study. These are a greedy reader’s questions, wanting more. As Navakas notes in a thoughtful coda, the method of the environmental humanities is to understand our present circumstances as framed by legacies from the past, legacies that are never smooth but point us to friction and complexity.

---

All text above by: Katharine Anderson. "Review of Navakas, Michele Currie, Coral Lives: Literature, Labor, and the Making of America." H-Environment, H-Net Reviews. December 2023. Published at: [networks.h-net.org/group/reviews/20017692/anderson-navakas-coral-lives-literature-labor-and-making-america] [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Headcannons about Yan Emperor

(Seventeenth Official Post)

(Name is Adonis Margold)

(Links to help you; 140 Shades of Purple Color With Names, Hex, RGB, CMYK Codes - Color Meanings , 134 Shades of Green Color With Names, Hex, RGB, CMYK Codes - Color Meanings , 140 Shades of Purple Color With Names, Hex, RGB, CMYK Codes - Color Meanings , eighteenth century | British Food: A History )

He hates it when he starts sweating, it makes his body feel all sticky and uncomfortable

He hates the color Harelquin green and despises the color Fuchsia purple, but loves the colors Chinese violet and tea green

He’s actually the son of a concubine/mistress and was quite close to his father (the late Emperor)

Despite this he has no intention of taking a concubine or mistress

His favorite food is filet mignon

His favorite dessert is smoking bishop (a British dessert from the 18th or 19th century)

He dreams about a domestic life with you (he’s even considered adopting/having a few kids)

He hated you when he first met you

He hates the Duke so much that he has a target dummy that has the duke’s painting on it and the emperor literally rips that thing apart with his sword/arrows

He’s been through 21 failed assassination attempts on his life, 33 failed assassination attempts on his mom’s life, 14 failed assassination attempts on his dad’s life, five failed assassination attempts on his siblings and 6 successful ones (he had a lot of siblings).

He doesn’t know how to ride a horse and wants you to teach him

He sleeps with a stuffed bear at night

He has a very comfy bed and often invites (commands) you to lay with him

He doesn’t hate the peasants, but he wants nothing to do with them and do he devised a plan to just take care of their needs, so they’ll stop bothering him

He absolutely despises any and all, except you, nobles, like he cannot stand being in a room with them for long than 20 minutes

His favorite flower is the Dawnrising flower, it only blooms at Dawn and he loves the way it looks.

It comes in two shades, one has a yellow center which fades into orange at the beginning of the petals which then fades into a light red and has splashes of light blue in it, and the tips of the petal are a dark shade of pink

The second version has a dark shade of purple center that fades into a light purple near the edges, then it fades into a pink as the petals bloom and the tips are a shade of blue

Although, Dawnrising flowers are quite rare and he’s only found a handful, all of which he’s kept alive and taken wonderful care of them

He doesn’t actually want to be the Emperor, but he’s the only one left in his blood line and he’s not one to forsake responsibility

He adores cute fuzzy animals and has a pet cat (it’s a tiger), it’s quite big though and has to be kept outside

Many women have tried to win the Emperor’s heart, but he has turned them away and will continue to do so.

This has caused speculation about the Emperor’s sexuality, some assume he’s into guys, but the truth is he doesn’t care about the gender as long as they have a respectable personality (also he just really wants to marry you)

He’s a very good dancer and favors the tango

When it comes to cuddles, he prefers to wrap his arms around whomever he’s cuddling and then lay on top of them (no idea why, of course this doesn’t mean he’s against being the little spoon when cuddled)

He gets bored rather easily and gets irritated just as quick

Despite his friendly personality, he’s actually quite cruel and temperamental. If someone bugs him too much or resists him too often, he’ll lash out and severely punish them

If the person he loves doesn’t reciprocate then he’ll wait a little for them to come to their sense, but if it takes too long then he’s not above kidnapping and murder

He has a reputation for being a monster on the battlefield, it’s said that he’s killed entire armies of opposing forces before (of course, his reputation could never live up to yours, you’ve got far more experience in battle then him)

He has a thing for really strong people and if the person he’s perusing has some muscles, well, let’s just say they should expect an onslaught of perversion and flirtatious remarks/touches

Although, if the one he loves Isn’t particularly strong, he doesn’t mind and will still love him

His favorite color is Liserian Pink

He likes watching the middle class performers do plays, actually he likes to watch plays in general and operas

He’s visited many places on Ilasatra and his favorite place to visit is Rais (the equivalent of china in this world)

He’s enjoys learning about other cultures and heritages, his own is a bit messy and he doesn’t like thinking about it

He hates his grandfather and doesn’t care for his grandmother

He never really cared for his siblings, except for a little boy named Frederick those two were quite close and up until little Fred died (at the age of twelve) Adonis spent a lot of time with him

He likes to read books on myths, particularly Terres myths (equivalent of Greek myths in this world)

He has a journal that he uses to write down every dream, every thought and everything about you, actually he has many, many journals. :)

(Hope you enjoy this and don’t forget to reblog/comment!)

(Also, please send in some asks/requests about my characters, I’m happy to answer them and it’ll give me the motivation necessary to continue posting!)

#yandere x reader#yandere oc#headcannons#my writing#yandere emperor x reader#Adonis my oc#Seventeenth Official Post#gender neautral reader#gn reader#Yander x gn reader

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Luis Meléndez (Spanish, 1716–1780) • The Afternoon Meal (La Merienda) • c. 1772 • Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Meléndez’s refined still life embodies an elegant, courtly mode of eighteenth-century Spanish painting. It dates from the moment that he received a commission of forty-four still lifes to decorate the royal palace and former hunting lodge of Aranjuez. This painting is exceptional, however, for its grand size and the inclusion of a luscious landscape. A picnic basket justifies the work’s traditional title, The Afternoon Meal (in Spanish, La Merienda), and evokes aristocratic excursions away from Madrid’s summer heat, while the local produce and traditional cookware deliberately ennoble Spanish culture. - Metropolitan Museum

#still life#art#painting#fine art#art history#luis meléndez#spanish artist#still life artist#painter#18th century european art#art lovers on tumblr#art blogs on tumblr#art of the still life blog#the metropolitan museum of art

37 notes

·

View notes