#crosspost from CRTaylorbooks.com

Text

By Our Love

One of my favorite words is liminal. It means those boundary places where we slip from one thing to another — beaches, twilight, dying. There are thin margins between those of us with ordinary means and those without. People without a place to live, without regular income.

We talk about freedom in this country. But freedom is an economic principle. We aren’t truly free unless we have the means to live. We aren’t free without the means to support ourselves, our families, the ones we love.

Life is complicated. People are complicated. Love is as complicated or as simple as we make it.

By Our Love was originally published on C R Taylor

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Enemy

Seventh Sunday after the Epiphany | Luke 6:27-38

Love your enemies. Do good to those who hate you. So who thought this was a good idea?

Do to others as you would have them do to you. Most of us are good with this one. We can wrap our minds around it, and it isn’t even specific to Christianity — there are other flavors of the golden rule floating around out there. We like the idea, until we realize that “others” includes everybody, including our enemies.

Loving our enemies? It makes no sense. It’s impractical and unproductive behavior. Unpatriotic, one might say. From people in the next booth at the Waffle House to military strategists, everyone will tell you that helping your enemies is not a sound principle.

What we all really want is to discourage, even punish, negative behavior — anything negative toward us, that is. Whether on a personal or a cultural or a national level, we want to intimidate our enemies. Nuke the bastards. Turn their houses into radioactive ash heaps, and you won’t have to put up with them anymore.

Art by Banksy. Stolen from his/her/their website.

And if we are a righteous, God-fearing people — we may substitute the name of our country, people group, or militant bridge club here — God is on our side, right? It isn’t about resentment or petty retribution. It’s now the judgment of a wrathful God upon our enemies. Right?

I confess that I have a list. There are people whom I’d like to see fall through an open manhole cover into a disease ridden sewer to land on the snout of the largest, most evil, ravenous, albino (because that’s weird and more frightening), man-eating, ebola-infected, urban crocodile ever imagined, with only prolonged and ragged screams ever emerging from that darkened pit.

Ok, maybe I’ve spent a little too much time thinking about it, but I’m not the only one.

The gospel message is that we ought not feed the darkness. To a degree, as with the Do Unto Others teaching, we can go along with it, but for most of us the notion that there is something worthwhile in every person loses steam in the face of certain individuals. Hitler is the classic example, but I’m sure we could all name less famous folk, some a great deal closer to us.

James Thurber wrote a story called The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. It’s a hilarious tale of an ordinary man who fantasizes about being extraordinary. A famous pilot. A brilliant surgeon. We laugh, until Mitty’s secret fantasies begin to hit home for us, and then we smile to cover our discomfort.

Most of us have pictured ourselves as heroes, destroying the bad guys. If we’re more passive, we imagine getting the phone call informing us that our enemy is humiliated, or ruined, or dead. And plenty of quiet grandmothers have imagined using a cast iron frying pan in non-culinary and extremely satisfying ways.

Most of us spend too much time thinking about the past. We drag up old resentments, slights, losses, injuries, and we make them into the central plot of the mental play of our lives. The movie plays in our heads relentlessly, and we keep watching, never imagining that we could change the channel.

Let’s be honest. We don’t want to love our enemies, even if we knew how. That’s the whole point of having them in the first place.

Paul, writing to early Christians in Rome, tried to put some spin on it — by doing good to our enemies, he wrote, we pour coals of fire on their heads. That sounds encouraging, and I can think of at least a dozen people who’d look great with their heads on fire. Unfortunately, Paul didn’t explain the mechanism by which it works, and we remain unconvinced.

Test yourself. Think of the worst person you know, the bottom (or top as it may be) of your list, and then imagine that you were given carte blanche. You could do anything you liked, and no one would ever know — no reprisal, punishment, or rocks to be thrown your way. What would you do?

Me, too. I wouldn’t even have to ponder it very long. It’s why so many of us secretly enjoy the Beatles’ Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.

So what do we do with this Love Your Enemies business? Most of the world’s inhabitants ignore it as dubious advice from a man who ended up crucified by his enemies. See where it got him?

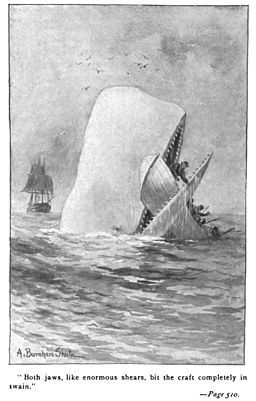

Moby Dick, illustration from 1892 edition

On the other hand, if we do have the inkling (let alone actual faith, but who has that?) that there is a God, or if we consider that we are all connected, or if we can accept that there is something greater than our own personal interests, then we’ve got to consider some possibilities.

For one thing, maybe doing good to our enemies introduces, activates, or confirms some value, worth, and possibly life changing power in their lives. Damn it. Maybe they are our enemies for reasons we do not see — in the movies playing in their heads, we are the ones who acted wrongly or who deserve their disdain. Or maybe they are truly loathsome people — some people are — but the nature of our response can undermine their world view. Maybe.

Another possibility is that doing good to our enemies adds intrinsic value to the universe. There may be other universes, other planes of existence, but here we are in this one. Making our universe a better place is our responsibility. Nobody is going to do that for us.

The best reason may be personal — doing good to our enemies has some intrinsic value for us. Yes, my imagination fails as well, but there it is. Helping another person, particularly when there is little question of reciprocity, has a greater effect on us than on them. It changes our estimation of their value as a person. It shifts the plot of the movie in our heads.

You don’t even have to be a Christian for these ideas to work. Compassion and forgiveness are embraced in many traditions, religious and non-religious ones. Compassion makes us better humans. Empathy and understanding make for more peaceful communities. And it is difficult to put out a fire by adding fuel.

The whole point is to stop thinking of ourselves as separate from everyone else. That’s hard to do, particularly in America, where our entire national mythos is built around the rugged individual.

This Gospel notion, though, isn’t for me, or you, or for that jerk over there. It’s for all of us. All inclusive. This Kingdom of God idea includes everybody, or at least invites everybody. No exceptions, no matter how much we’d like to submit a list of rejects. In Buddhism, the notion of connectedness hasn’t been diluted by western individualism, but Christianity has to reach for it.

We might even find that people we think are our enemies really aren’t. They may not even give us much thought. Of course, that isn’t always the case. There are dangerous people out there. Hate groups. Neo-nazis. Terrorists. Thinking that our response to our enemies is a purely personal act, as opposed to a broader cultural or national one, is also dangerous. It limits our possibilities, and it limits our understanding of our responsibilities. How we as individuals choose to act is important, but we are not relieved of responsibility as members of a community, a culture, a religion, a nation, a civilization.

What does it look like, this doing good to our enemies? A lot of it is obvious. Some of it isn’t.

If I see a person in need and do nothing, am I their enemy? If I see someone being harmed, oppressed, held down, injured by individuals or by society or by some groups in that society, and I do nothing, am I their enemy? Maybe I am.

And religion, particularly Christianity, doesn’t have a good track record on this one. Plenty of Christians used faith based arguments — wrongly, of course — to justify slavery. Today, plenty of Christians use faith based arguments against LGBTQ people — again, wrongly, although this would be an entire topic of its own. How is hatred and exclusion and intolerance furthering the kingdom of God? Even if Christians could manage to justify regarding some people as enemies of their faith, the gospel commands a response of love and of doing good.

Instead, Christianity has often become a bastion of exclusion, intolerance, and hatred disguised as religious observance. That’s not what the gospel preaches, people. I don’t know what label to put on the exclusionary and intolerant form of religion often practiced today, but it isn’t Christianity. It is something else, dressed up in the forms and language and symbolism of the Church.

To put it another way, Christianity has become its own worst enemy. Being excluded by Christians can be harmful, in real and in dangerous ways. Being within the Christian world can also be toxic — we may find that we are our own enemy. And it may be that loving our enemies begins uncomfortably close to home, maybe even inside our own heads.

When we love our enemies, we are reaching. And we’re remembering that we are not able to place ourselves in a different world than they occupy. We’re in this thing — love it or hate it — together, and we need to embrace it. And one another.

Bernard of Clairvaux, in his work On Loving God, concluded that the best and strongest reason to love God is God — love is its own reward. In Luke’s gospel we hear that “the measure you give will be the measure you get back.”

Perhaps that is the reason to love our neighbors, our enemies, ourselves. The love we give is the love we get.

Art by Banksy. Stolen from his/her/their website.

The Enemy was originally published on C R Taylor

0 notes

Text

The Real Thing

Sixth Sunday after the Epiphany | Luke 6:17-26

Reading Luke’s beatitudes, we want to make them about spiritual things. Is that so wrong, to read a Sermon on the Mount passage, and to want it to be about spiritual things? Maybe. It’s wrong, if we pretend Jesus was not addressing practical things, because that lets us ignore what he said.

Blessed are you who are poor, we find in Luke’s Gospel. We prefer the other wording — blessed are the poor in spirit — but that is Matthew’s version, not Luke’s.

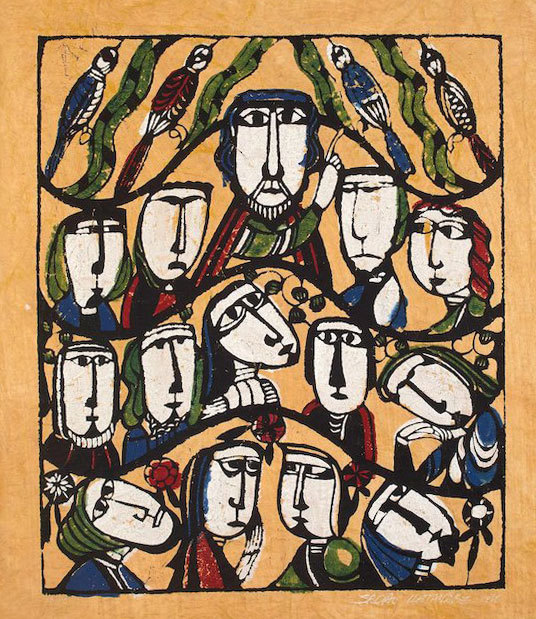

Sermon on the Mount. Print by Sadao Watanabe, 1968.

It’s our version, too, if we’re honest. Over the centuries, the church tends to quote Matthew for this material, not Luke, just as we tend to use the Lord’s Prayer as found in Matthew, not the shorter, more terse, prayer from Luke. In Matthew, all of this sounds better, and all of this sounds less practical, more other-worldly, more to do with heaven than with earth.

Blessed are you who are hungry, we read in Luke, but we want it to be a spiritual thing — by which we mean not a physical, human thing. Not real hunger. Not like a child who hasn’t eaten, not like those people fleeing the beaches of Africa in leaking boats, not like homeless people sleeping under garbage bags on the sidewalks of the richest nation on earth.

Blessed are those who weep, this gospel says, and we want the tears to be somewhere inside, unseen. Something spiritual that we can gloss over with words. Nothing that requires a tissue or a handkerchief, nothing that would let our tears wet our fingers. Nothing that would cause us to ask what was the matter and have to help make it right.

If you are truly poor, maybe reading this on a screen in a distant place, then I want to say thank you. Past that word of thanks, I am not sure I have anything else for you in my words. If there are blessings in hunger and in poverty and in being hated, you already know them. I am really addressing myself and people like me — we who have so much more than most of the world. Homes. Steady income. Plenty of food on hand. Clean clothes, air conditioning. Medical care.

In Matthew, when Jesus teaches the people to pray, he includes the phrase “on earth as it is in heaven.” Luke doesn’t.

Van Gogh’s The Sower at Sunset. Kröller-Müller Museum. June, 1888.

Maybe Matthew is thinking more of the spiritual life, or maybe the intent is to point out the gap between the here and now and the then and there. Maybe both gospels intend to point to the discrepancy between what we say and how we live, between the spiritual and the physical life, the widening chasm between heaven and earth. Maybe the idea is to close the gap that we ourselves have created. Luke knows that the reality of life is nothing like we imagine heaven to be. Not for the hungry, or the weeping, or the poor, the hated, the excluded.

We also like Matthew’s spiritual beatitudes because there are no woes listed, no negative pronouncements. We can fool ourselves into thinking that the woes of Luke do not apply to us.

Woe to you who are rich. Woe to you who are full. Woe to you when all speak well of you.

I have to admit that all three of those things apply to me. And I want to turn back to the kinder Matthean vision, a gospel where I can fool myself into believing that we are spiritually poor, spiritually hungry. Ironically, I am, but not in any sense that is going to let me escape those woes. I don’t get off cheaply — there is no cheap grace here. There is no cheap grace anywhere, not if it is real.

Of course, there is no line, no division between the physical and the spiritual, not really. Not if we are to be human. Many Christians complain that there is not enough attention paid to spiritual matters, spiritual truths. Usually, they mean rules of behavior and methods of controlling other people — one’s family, one’s friends, one’s society. Not surprisingly, if we followed the very practical advice of the New Testament letter of James — feed the hungry, find clothes for the poor, see to their very physical needs — we would be astonished to find that the spiritual lives of everyone involved were enriched. Healthier. More alive. And life on earth would be that much closer to the ideals of heaven.

The Real Thing was originally published on C R Taylor

0 notes

Text

Deep Water

Fifth Sunday after the Epiphany | Luke 5:1-11, Isaiah 6:1-13

We don’t know what Jesus told them. A story centered on Jesus sitting in a boat and teaching a crowd, and we don’t hear a word of what was said. That’s odd.

We do hear from Peter, a fisherman willing to let this wandering teacher use his boat as a platform, the water’s edge as an amphitheater. More than that, Peter is willing to take their nets, the ones they were washing out and putting away, and drop them back into the Sea of Galilee. (Yes, same place — Gennesaret, Galilee, Tiberias.) Whatever Jesus had been saying must have made an impression.

When tired fishermen pull in two boatloads of fish, that makes a bigger impression.

Peter’s reaction is the most interesting part. That is where this gospel story is focused — not on the teaching, not on the miraculous catch that’s so large we’re still telling the fish story 2,000 years later, but on how Peter responds.

If Peter had no depth of character, he would have asked Jesus to come back and repeat the miracle the next day. If he had been a religious man, Peter would have questioned Jesus, his claims of authority, this sign of his miraculous power. If Peter were a little bit more religious, he would have asked for blessings — not fish, but other gifts. Power. Something to be gained from the divine.

If Peter were extremely religious, carrying around the guilt that religious folk specialize in carrying around and handing out, he may even have asked for forgiveness. He doesn’t do any of that. Instead, he asks Jesus to leave.

“Go away from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man.”

Maybe that’s what Jesus sees in Peter. Not his sins, likely as plentiful as our own, but his heart. His lack of self-deception. His focus on what he himself lacks rather than on what someone else might do for him.

“In the year that King Uzziah died, I saw the Lord….” That is the beginning of the matched passage the lectionary gives us from Isaiah. King Uzziah had been king for over 50 years — since long before the prophet was born, it is thought. A father figure, a symbol of authority and stability, a personification of national identity, is dead. It’s a crossroad, a moment of change, and the prophet has a vision of God.

“Woe is me! I am lost, for I am a man of unclean lips, and I live among a people of unclean lips; yet my eyes have seen the King, the LORD of hosts!”

Sound familiar? It’s the same kind of heart. Peter might have said the same thing, given a better vocabulary.

Today, it’s popular to focus on the other person, but not in a good way — here’s why she’s wrong, why he’s not like us, what they should be giving us, why we think God is going to condemn them and love us. Peter and Isaiah are self-centered, but not in a bad way — here’s what keeps me humble, what makes me understand that the universe does not revolve around me.

Peter saw everything clearly, and he found it to be a humbling experience. May we learn from his example.

There were other similar stories in the gospels, of course. Here’s a re-telling of one set later in John. It’s from my novel, I,John.

I was left remembering all of it, at least I was left remembering those days. They were in my mind with the vividness of dreams, the ones that somehow seem more real than memory. Not that all of it was the same. Some moments stood out more than others, as with any memories, and not always the moments that I would have thought. One might think that the crucifixion was my most vivid memory, but it was not. Oh, I remembered that day, certainly, but it was not what haunted my dreams or crept into my waking thoughts. I remembered blind men, and Mary. I remembered Peter’s great bobbing head as he made his way through the crowds. I remembered the bread that Jesus gave us.

Most of all, I dreamed of that morning at the shore.

Smoke was rising from a small fire on the beach, and I saw him standing next to it. He was looking over the water toward us as we made our way to shore. I thought I knew him, even from that distance, but I couldn’t place him.

No one was talking. Peter’s boat was creaking, leaking slightly from having seen little use for the last three years. Maybe it was good that we had caught nothing. We probably would have torn the nets and sunk the boat with us in it. A fine bunch of fishermen we were. Perhaps we had forgotten how to fish, forgotten how to live like regular people, make a living.

Peter was mending a hole in the net. He dropped the netting shuttle, and I could hear him muttering and cursing as he felt around in the coils of rope for it. He had a curse for everything, all manner of language rearranged to suit the target. When his muttering died down, the only other sound was made by waves gurgling on the side of the hull.

“Friends, have you got any fish?”

I heard his voice over the water. Friends, he said. Something about the voice was like it was speaking inside me instead of from the beach, a crazy idea.

No, we told him. Nothing. No breakfast here. Go away.

“Throw the net on the right side of the boat, and you will catch some.”

All of us stared over the water at him, at the small fire, the smoke. That voice, I thought. We each turned and looked over the side of the boat. Nothing, no ripples, no flash from fish swimming in the morning light. We looked at our nets, piled in the bottom of the boat, wet and empty. Nobody spoke; we just started moving, pulling a net up, throwing it over the side.

The ropes pulled tight right away. We must have snagged something, I thought, and I leaned over the side to see into the water. Fish, schooling, a flashing churning shoal of fish, were filling the net, drawing it down. The others started pulling on the net ropes, straining against the weight. I was holding a mast tie, leaning out the other side of the boat for a counterweight, and I looked back to see him on the beach. He stood perfectly still, watching us, and I thought he smiled. That was when I knew him.

“It is the Lord,” I said, leaning out over the water. The boat lurched as Peter grabbed his tunic and jumped into the water, swimming for the shore. The rest of us struggled to get the net into the boat, fish piled gasping at our feet. As we made for shore I again held a mast tie and leaned out over the water, this time at the bow to listen and watch. It seemed to me that their voices murmured across the water, Peter and Jesus, but I could never tell what they said over the sounds of the oars and of the others talking in the boat before letting their words die as they also looked to the shore and to the one sitting with Peter on the beach.

There was a bump and the sound of sand dragging against the hull, and we were ashore. We left the boat and the fish, not bothering to cover them with our net or to wet them as was our wont. We stepped onto the sandy beach still unbelieving but wanting to believe, waiting for our vision to clear or the moment to resolve itself into something other than what we perceived.

Jesus was sitting by a fire, his arms around his knees as though simply sitting there was natural, was what he always did. He is dead, I thought to myself. I watched him die, slowly, crucified. Most of the others had run, not that I blamed them. I stayed. The women were there and somehow I could not leave them, could not leave him.

“Mother, behold your son,” he had said. I thought he meant himself. “Son, behold your mother,” he had added, and I knew he meant me, though at first I thought he meant to call me his son rather than Mary’s. Later I was not so sure he did not.

In years to come it was the sea that I thought of, blue green at the surface that day, black in the depths and shoaling with silver fish unseen from above.

Deep Water was originally published on C R Taylor

0 notes

Text

From the Inside Out

From the Inside Out | Matthew 9:35 – 10:8

Where are the miracle workers when you need them?

Then Jesus summoned his twelve disciples and gave them authority over unclean spirits, to cast them out, and to cure every disease and every sickness. (Matthew 10:1, NRSV)

If Christians went around with the ability to cure every disease and every sickness, people would pay attention. More people would become Christian, some because they had seen a miracle and it stirred their faith, others because they had seen a miracle and wanted one.

Instead, miracles are as scarce as they ever were, and fewer people are interested in Christianity.

The decline of Christianity may be due to the lack of miracles, but it is more likely due to the abundance of Christians, the loudest and meanest ones anyway. Every day I hear someone condemning other people—usually people who are different, in upbringing, orientation, geography, politics—in the name of Jesus. Forget the fringe groups who would hate everyone else regardless of their own religion. There’s plenty of hate and fear in the mainstream, and only the television charlatans claim to heal in the name of Jesus.

It’s enough to make me want to call myself anything but Christian. Most days Buddhism is looking pretty good. I can imagine Jesus embracing it.

So what do we do with passages like the one from Matthew’s Gospel, claiming that the followers of Jesus will work miracles? It says that Jesus gave his disciples the power to throw out “unclean spirits”—however we might understand that phrase today—and to heal every disease. Imagine it. Imagine being able to stroll through a children’s hospital and heal every kid in there.

Be healed in the name of Jesus. Regardless of your disease. Regardless of your sexual orientation, or faith background, or country of origin. Of all the people Jesus encounters in the gospel stories, he only questions the nationality of one—the gentile woman whose daughter is ill or possessed. It seems his question is pointed outside the gospel, pointed at us, we who listen to the story today, because he goes ahead and heals her daughter anyway.

So did the disciples have the ability to heal people? The gospels say so. The early Church reports it as so. (For example, see Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses, 2.32.4, written in the second century.) How do we understand the stories? Is it true, literally true, that they could heal the sick? Could Jesus? Did they perform these miracles? If so, why was there not a Pied Piper effect, a daily triumphant-entry-Palm-Sunday kind of parade?

Some people say our lack of miracles is due to our lack of faith. They may be right. I can’t contradict them, certainly not with the pitiful amount of faith I myself possess.

There are plenty of religious people eager to point to the modern lack of faith, or to some temporary dispensation of power to the early Christians not shared with us, we later poorer children, but we’re left feeling that the explanations don’t hold water or that we’d have to wear blinders to buy into them.

In the meanwhile, there are other ways to think about it.

Could these be symbolic stories, disease and unclean spirits as a metaphor? Fables or allegories? Simply stories with a meaning? Does that work? Could we think of them that way, and remain among the faithful?

Otherwise, we have no good explanations, but even without an explanation, there may be an application.

Albert Camus said this, though he wasn’t speaking to miracles—

We must mend what has been torn apart, make justice imaginable again in a world so obviously unjust, give happiness a meaning once more to peoples poisoned by the misery of the century.

The prophets put it this way:

He has told you, O mortal, what is good;

and what does the Lord require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness,

and to walk humbly with your God?

(Micah 6:8, NRSV)

Maybe we lack the power to walk into hospitals and heal the sick. That is a God-thing, and maybe it always was.

Maybe our work is the lesser miracles—mending what we have torn, restoring justice where we have failed, giving happiness to a child who has known nothing but war and hunger and fear. A home for the homeless. Food for the hungry. Clothes and education and peace for the poor. And medicines for the sick.

Those are pretty good miracles. We already know how to perform them. What is holding us back? Where are the miracle workers when you need them?

From the Inside Out was originally published on C R Taylor

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Magi

Epiphany | Matthew 2:1-12

A few years ago, I began writing posts, reflections matching the gospel passage for each Sunday in the Revised Common Lectionary. In January of 2016, Epiphany didn’t fall on a Sunday, and there was no need to write about it; this year, Epiphany does, and if I am going to complete the series, there needs to be a matching post.

I didn’t foresee, when I started the project, how tiresome it would get. Three years of Sundays. It’s been rewarding, certainly, but tiring just the same.

Magi, though. Magicians. Sorcerors. There’s something intriguing, something you don’t see every day.

They aren’t kings, you know. “We Three Kings” is one of my favorite carols — I love the minor keys, and darker songs vibrate sympathetically with something inside me. Still, the word is μάγοι, transliterated into English as “magi”, plural form of the word from which we get magic and magician. And not the kind with doves stuffed in their pockets or scarves shoved up their sleeves. This is the darker kind, or the more enlightened kind, depending on your viewpoint.

These are people who studied the stars, watched for signs. They paid attention to dreams, because the truth bubbles up in them. They sought knowledge. (They may have tried to change lead into gold, because let’s face it, who wouldn’t like to know the secret of that trick?) Today, they might be the three scientists.

Just not kings. There was a word for that, βασιλέως, basileos, like Herod. (We get basilica from it — a building that would have been suitable for a king, στοά βασίλειος, stoa basileos, chamber of a king.)

They came from the East. As origin stories go, that one’s a little vague, the East being a big place. Still, we all have things in the past we don’t want to talk about.

And they followed a star. A moving, erratic, miraculous star that somehow led them to the exact house (maybe in Bethlehem although Matthew doesn’t quite say, not if you read closely, does it?) wherein they could find Mary with the young Jesus. No, not the manger. Read the story. And give up trying to make Matthew’s tale match Luke’s — it doesn’t. This is Matthew’s story, and it has different reasons, different themes.

These magic fellows came at a different time than Luke’s manger story, to a different place, when the child was nearly two. That’s when they told Herod the star appeared, two years prior, and that’s how old you had to be, if you were a baby in Bethlehem and didn’t want to be murdered by Herod’s henchmen, over two. It’s not a pretty story. Even if there is nothing outside of this Gospel to corroborate the tale of Herod murdering children, there’s plenty of proof that all of the Herod clan were unpleasant. Herod wasn’t a magician; he was a king, and that’s how tyrants roll.

So the magic star stopped, somehow indicating a single house (unless they checked around, and nothing indicates whether they did or didn’t), and the Magi found Jesus and Mary and honored them with gifts. Then the Magi, listening to their dreams, went back into the fabled East without a word to Herod.

What do we make of all of that? How does it matter?

We could go full evangelical on it and try to prove that the star was real, match it to some comet. We could get so lost insisting that the story is true that we miss the truth of it. That happens a lot these days. You don’t have to go far or question much to find an angry evangelical Christian, ready to yell at you or worse in the name of God.

The star doesn’t matter. The location of the house doesn’t matter. Where in the East these Magi came from doesn’t matter. The gifts they gave are not important (although the gold might go a long way toward explaining how an older Jesus seemed well enough funded right from the start that he could leave his day job and go walkabout.)

It matters that we remember to look around, to notice the signs around us. I don’t mean stars leading us, thought that would be nice. Ordinary things can keep us focused, if we pay attention. A word. A dark song. Geese honking across our sky. Anything that jars us awake, makes us pay attention to being alive. We sleep through our lives, and how few of us follow either our stars or our dreams?

Dream of the Magi

Dreams. There are several in Matthew. God speaks to Joseph four times in dreams, and he listens. God warns the Magi in their dreams, and so they traipse off into the night. In dreams, the barriers between what we allow our waking mind to think and what our unconscious mind knows can drop. We encounter our fears, our own truths. We should not dismiss the truth in the flight of birds, the beauty of the stars, the strangeness of the quiet voice in the backs of our minds and the depths of our dreams.

When we find something worthwhile, we should honor it. The Magi gave rare gifts of gold, frankincense, myrrh. We might give our time — it seems the thing we have the least of anymore. And let the finding be enough. The Magi didn’t try to move into Mary’s house. They didn’t overstay their welcome. And all they took away was the experience, which they knew was enough, and which is how we know they were wise, of course. We don’t have to own a thing, to hold onto it, for it to be part of us. A lion is more beautiful alive in Africa than dead on a trophy wall. The Magi knew that if this child was God, there was no place on earth they could go where God would not still be with them.

Epiphany. ἐπιφάνεια, epiphaneia — an appearance. A manifestation. Revelation. Literally the word means something like “a showing forth” or “a shining upon.” Today we use it when we have a moment of clarity, an ever more rare moment of understanding something that matters. Something that guides us. Something that resonates in our dreams.

Don’t be afraid of the dark. That’s the only place where we can see the stars.

And don’t be afraid of tyrants. Leave them in the dark, since they fear it.

And look around for something pointing the way to what matters. Look for those things that are true, and good, and pure. They are still in the world, pure and holy things, as simple and full of potential as a child, if we let ourselves find them.

And don’t forget to dream. The part that matters will stay with you when you wake, no matter how far you wander.

The Magi was originally published on C R Taylor

0 notes

Text

Not Very Nice

Mark 2:23-3:6 | Second Sunday after Pentecost

Why do so many people want to insist that Jesus was always nice? They like to talk about Jesus healing people, and they love to say that he suffered the little children to come unto him. (We can thank the King James for that fascination, I think.)

Mark is describing another sort of Jesus, an angry one.

Someone saw Jesus and his disciples picking ripe grain as they walked through a field. It’s an odd snack, but they were hungry. A group of religious men (and yes, we may be fairly sure they were all men) accused them of breaking the Sabbath, reaping on the day of rest, work that was by the letter of the law proscribed. Their accusation made Jesus angry.

The Reaper, by Vincent Van Gogh. 1889. Collection of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

To borrow a line from Sidney Poitier’s character in The Simple Life of Noah Dearborn, it’s ok to be angry. There are places and times when anger is the appropriate response. These days it isn’t difficult to find such a place or time.

The caution comes when we consider why Jesus was angry and who crossed him — religious people. If Christianity has it right, God Almighty incarnate was ticked off with some religious people.

There’s plenty of irony.

Rules. Rules can be a fine way to achieve an end. Rules can be tools, a method. Consider the rule of a monastery—some things laid aside, others picked up. Rising before sunrise to pray. Perhaps keeping silence. Obedience. Or consider keeping the Sabbath. Even today, observant Jews may find the rules of the Sabbath challenging, restraining, or they may find keeping the Sabbath to be liberating, freeing, restorative, which is the entire point, of course.†

The religious people complaining to Jesus wanted to bind God in rules for which they had forgotten the meaning. They were like men who set out on a journey but forgot their destination.

Rules aren’t the point. They’re just the method.

Here’s something else that is fascinating — Jesus answered them with a story, not an argument. He told them a story about David eating the bread of the Presence, bread reserved for the priests. It’s a story about one of God’s favorite people breaking the rules. (You can find it in 1 Samuel 21.) Maybe that’s one of the reasons God loved David: all those rules he left scattered behind him like broken pottery.

David is on the run, hungry, fleeing for his life from Saul, the unhinged, autocratic king. The priest Ahimelech gives David sacred bread to eat, and he also gives David the sword of Goliath that oddly enough had been kept in the sanctuary — holy food and an oversized weapon. When word reaches Saul of what the priest has done, Saul orders Ahimelech and his fellow priests to be slaughtered, along with their families. It’s not a pretty story.

The Harvest, by Vincent Van Gogh. 1888. Collection of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Jesus tells the religious folk who were objecting to hungry people picking grain on the Sabbath that the Sabbath day was made for humankind, not the other way around. Jesus is reminding them of the reason for the Torah, the law — to enrich the lives of people, to open a relationship with the Divine. They could not grasp it, having long before traded the law for their rules.

Their rules were easier. Focus on the Torah would have kept their eyes on God, which may have been wonderful or terrible, but never comfortable. Focusing on their rules let them divert their attention from the Divine. They subverted their own experience of faith.

We’re supposed to criticize the rule-keepers. At least, that seems to be the way of present day Christianity. Point at the ridiculous critics, shake our heads at their short-sightedness. Maybe that’s part of the reason that Jesus was angry. He knew that all these years later, we’d share one thing, at least, in common with the rule-keepers — we think that we are better at being good. And in focusing on behavioral delimiters, boundaries of acceptable Christian behavior, we loose track of our goal. Generally speaking, Christian ethics, like the ethics of every major religion, result in good behavior, good citizens, good neighbors, but that isn’t the point. You can achieve that same level of ethical behavior as an agnostic or an atheist, it’s just that the basis of your rules would be different.

One person may feed the hungry because that strengthens society, or because one day he may find himself hungry. The person of faith feeds the hungry because she sees the image of God in their faces.

There is a deeper point in the Torah, a more sublime meaning in doing unto others as we would have them do unto us. In loving our neighbor, we draw closer to the Divine. The closer to God, the fewer rules we need. And those first disciples walking with Jesus? It wasn’t a handful of grain that sustained them. It was the presence of God.

† For more along this line of thought, you may enjoy Surprised by God, by Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg. Here’s a link to her website and to more information about her book: DanyaRuttenberg.net/books/surprised-by-god

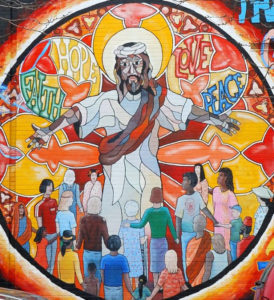

Jesus Mural of Faith, Hope, Love, and Peace, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN.

Not Very Nice was originally published on C R Taylor

1 note

·

View note

Text

Communion with the Divine

Third Sunday of Easter | John 21:1-19

Communion with the Divine

“The morning that we found Jesus on the beach stays in my mind. I have never understood why. It was not the most impressive day in my memory, but it has become one of the most persistent. Finding him on that beach was miraculous, or so we thought at the time. Now it haunts me…”

Habits are powerful things, and habits of thought are among the most powerful.

Take the simple notion that it is good to get up each day and get going, to do the work at hand — it is one of the simplest ideas we can have in our lives, but in the end it is the thought that helps get us through our most difficult days.

Sometimes our thought habits get in the way. We misremember events, tilting them in one direction or another, embellishing our worth or exaggerating an injury done to us. Conversely, we seldom revise our opinions of other people, even when they deserve a downgrade or have earned better.

Our habits of thought are wickedly pernicious in matters of faith. We believe what we believe, and that is that. Of course, such devotion to a set of ideas is not faith at all: it is idolatry. Little by little, we trade faith for certainty until we leave off worshipping God and begin worshipping our own ideas about God. Once we get there, our ideas seldom change.

Closed-mindedness is the death knell of spirituality. It’s the death knell of decency, of warmth, of humanity. God may not change, but our understanding of God must — or did we think we understood everything, right from the beginning? Perceiving the divine depends upon our willingness to be surprised. Nothing gets into a closed mind, not even God.

In John’s gospel, a few tired, disillusioned disciples nearly give up. Thinking their journey with the miraculous over, they return to fishing, a way of life some of them knew before Jesus’ arrest and the fiasco of his death. Even at that point, they were still willing to be surprised, willing to experience the divine in a meal of fish and bread, served by a person they thought never to see again.

When they expected never to hear the living voice of Jesus, he called to them across the water. Having watched him die, they opened their minds to the divine reality of seeing him alive.

God may be in the explosions of stars, the expanse of space. John’s gospel says that we may also find God in the smallness of a loaf of bread, if our minds are open to the possibility.

Imagine, communion with the divine.

Here is another version of the story from John’s Gospel, as I retold it for the opening chapter of I,John. Sometimes just hearing a story told differently can change the way we think about it. I hope you enjoy it.

John

The morning that we found Jesus on the beach stays in my mind. I have never understood why. It was not the most impressive day in my memory, but it has become one of the most persistent. Finding him on that beach was miraculous, or so we thought at the time. Now it haunts me.

I see angels, and I see other things that are not angels. At least I see and hear beings who are not like us but who think and act and move, without bodies like ours. A few of them are brilliant and astonishing. Some are dark and fearful. I think that they are different beings, but they might be differing versions of the same kind of thing. And there is Adriel, whom I have heard and seen every day since we found that empty tomb.

Seeing creatures and hearing voices doesn’t mean they are real. A great many people have seen things that did not exist outside their minds. Of course, even if I couldn’t see these beings, couldn’t hear their voices, it wouldn’t mean that they weren’t there.

In the beginning was the word. That is how it began, just words and a man who walked down the shore and found us in our father’s boat. That’s the truth of it. He walked around talking to anyone who would listen, and he found us. Why we got up and followed him, I wonder.

Look where it got us. Look where it got him.

My father’s boat—we spent so much of our childhood in it. I can barely remember what he looked like, my father, but I do remember his beard, his hands. And I remember his eyes, looking at me when Jesus called us to follow him—my father was staring at me like he was gauging the strength of a net. He nodded, I thought, at least it seemed to me later that he had nodded, had offered us that small blessing with the quick understanding of a father. He could read water, read the sky, read the fish swimming, and he read my brother and I, though he was looking at me. My brother James was always like a fish jumping for a light, holding back just for me and for our father to decide. James was the oldest, but while he often walked ahead of me, he somehow always seemed to be following me.

So our father, Zebedee, looked at me and nodded, and James and I put down the nets and walked away with Jesus. It was never the same afterward. Maybe that is why I remembered that moment. Something in me knew that it was important, that it marked a change. There are moments in our lives that matter, not that there are moments without value. It is just that some moments are like a point when we are touched by God. We are brought into contact with something greater than ourselves, outside ourselves, that resonates with the spirit within us. We never returned, not really, not to stay. Our father’s boats were finally given to the servants, and sometimes I felt regret and doubt for leaving that life. We had not understood when we walked away with Jesus that day that we would never return. I don’t know whether my father knew it, but we did not.

Maybe that is why I agreed to look after Mary in the end. I was an irresponsible son who walked away from my father and our family business, and looking after her offered me a sense of redemption. Not that I had any choice. He had found the strength to speak while hanging on that cross. “Behold your mother!” What was I going to say? No, thank you, I have other obligations? Maybe that was the reason he said it, made that effort as he hung there to place Mary in my care and me in hers. It was a gift, something that would heal the sense of guilt inside me that he knew I carried, though I never spoke of it. Perhaps he had known how much I missed my father just from my voice, or from the way I sometimes spoke to James, or perhaps Jesus simply knew.

I loved her, of course. Who could not love Mary? If James and I were marred by what we saw that day, watching him suffer, watching him die, then she was more so.

And he was certainly dead.

I am left remembering all of it, at least I am left remembering those days. They are in my mind with the vividness of dreams, the ones that somehow seem more real than memory. Not that all of it is the same. Some moments stand out more than others, as with any memories, and not always the moments that I would have thought. You would think that the crucifixion might be my most vivid memory, but it is not. Oh, I remember that day, certainly, but it is not what haunts my dreams or creeps into my waking thoughts. I remember blind men, and Mary. I remember Peter’s great bobbing head as he made his way through the crowds. I remember the bread that Jesus gave us.

Most of all, I dream of that morning at the shore.

Smoke was rising from a small fire on the beach, and I saw him standing next to it. He was looking over the water toward us as we made our way to shore. I thought I knew him, even from that distance, but I couldn’t place him.

No one was talking. Peter’s boat was creaking, leaking slightly from having seen little use for the last three years. Maybe it was good that we had caught nothing. We probably would have torn the nets and sunk the boat with us in it. A fine bunch of fishermen we were. Perhaps we had forgotten how to fish, forgotten how to live like regular people, make a living.

Peter was mending a hole in the net. He dropped the netting shuttle, and I could hear him muttering and cursing as he felt around in the coils of rope for it. He had a curse for everything, all manner of language rearranged to suit the target. When his muttering died down, the only other sound was made by waves gurgling on the side of the hull.

“Friends, have you got any fish?”

I heard his voice over the water. Friends, he said. Something about the voice was like it was speaking inside me instead of from the beach, a crazy idea.

No, we told him. Nothing. No breakfast here. Go away.

“Throw the net on the right side of the boat, and you will catch some.”

All of us stared over the water at him, at the small fire, the smoke. That voice, I thought. We each turned and looked over the side of the boat. Nothing, no ripples, no flash from fish swimming in the morning light. We looked at our nets, piled in the bottom of the boat, wet and empty. Nobody spoke; we just started moving, pulling a net up, throwing it over the side.

The ropes pulled tight right away. We must have snagged something, I thought, and I leaned over the side to see into the water. Fish, schooling, a flashing churning shoal of fish, were filling the net, drawing it down. The others started pulling on the net ropes, straining against the weight. I was holding a mast tie, leaning out the other side of the boat for a counterweight, and I looked back to see him on the beach. He stood perfectly still, watching us, and I thought he smiled. That was when I knew him.

“It is the Lord,” I said, leaning out over the water. The boat lurched as Peter grabbed his tunic and jumped into the water, swimming for the shore. The rest of us struggled to get the net into the boat, fish piled gasping at our feet. As we made for shore I again held a mast tie and leaned out over the water, this time at the bow to listen and watch. It seemed to me that their voices murmured across the water, Peter and Jesus, but I could never tell what they said over the sounds of the oars and of the others talking in the boat before letting their words die as they also looked to the shore and to the one sitting with Peter on the beach.

There was a bump and the sound of sand dragging against the hull, and we were ashore. We left the boat and the fish, not bothering to cover them with our net or to wet them as was our wont. We stepped onto the sandy beach still unbelieving but wanting to believe, waiting for our vision to clear or the moment to resolve itself into something other than what we perceived.

Jesus was sitting by a fire, his arms around his knees as though simply sitting there was natural, was what he always did. He is dead, I thought to myself. I watched him die, slowly, crucified. Most of the others had run, not that I blamed them. I stayed, the women were there and somehow I could not leave them, could not leave him.

“Mother, behold your son,” he had said. I thought he meant himself. “Son, behold your mother,” he had added, and I knew he meant me, though at first I thought he meant to call me his son rather than Mary’s. Later I was not so sure he did not.

In years to come it was the sea that I thought of, blue green at the surface that day, black in the depths and shoaling with silver fish unseen from above.

Communion with the Divine was originally published on C R Taylor

0 notes

Text

Ideas on the Way to Resurrection

Easter — Resurrection of the Lord | John 20:1-18 or Luke 24:1-12

Ideas on the Way to Resurrection

What if we don’t buy into this whole story about Jesus coming back to life? What if people made it up? Or what if we only believe it because of our upbringing, or fear of dying, or simply habit?

We wouldn’t be alone. There is plenty of precedent, maybe even including the original, odd, abrupt ending¹ of the first and oldest gospel, the Gospel of Mark. Women come to the tomb to add spices and perfumes to the body of Jesus, an embalming, only to find the tomb empty except for a stranger who tells them that Jesus has risen from the dead, and the women flee in fear and ecstasy. That’s it. No elaboration. No explanation.

Yet the early Christians (they called it the Way² — still a better name, I think, after all the centuries) flourished. They did it without a systematic theology or chocolate bunnies. They didn’t know that we would call this celebration Easter, the celebration of the story that Jesus died, was laid in a tomb, and rose again.

No painted eggs. No fake grass. No Easter egg hunt.

But what if we still can’t quite believe such a thing happened? What does God do with us, if there is a God?

God starts with us where we are, I think. Actually, if God is unbounded by the space-time fetters that define us, perhaps God starts with us where we are, where we have been, and where we will be, all at once.

And if we can’t quite accept that Jesus was resurrected, how about we just start with the idea of resurrection? It’s a pretty good idea — life where there was none, a new beginning, a fresh breath. Genesis.

What if we think of Christianity (the Way, if you like,) as faith in the idea of resurrection, a celebration of the notion that lives can begin again. Broken things can be mended. Lost things can be restored. New life can begin, and we don’t have to spend our lives shut away in some dark place, no matter whether we got there ourselves or were carried against our will.

Resurrection. That is something worth believing in, an idea worth holding onto. It’s reason enough to follow the Way.

And what of these astonishing claims that God was expressed in human form in this man Jesus, that this God-man allowed himself to die a cruel death at the hands of people like us, that afterward he rose from the dead? Surely if this happened, nothing stranger ever has?

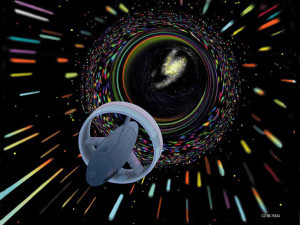

Wormhole, digital art by Les Bossinas, via NASA.gov

It is interesting, the things we believe. Take Sea-Monkeys, dessicated brine shrimp that somehow return to life after being dried to dust. We watch them return to life, swimming in little plastic aquariums we order from comic books, and marvel. For fishing bait, my grandfather collected Catalpa worms (we called them Catawba worms, but they are the larvae of the moth Ceratomia catalpae.) He kept them in a box in the freezer. You could take them out later, let them thaw, and sometimes the things would begin to move again. It was peculiar, and amazing, and creepy.

Consider black holes in space, points of such dense gravity that even light itself is pulled inside. Unbelievable. Then there is the idea of a wormhole. Nothing to do with fishing, the Einstein-Rosen bridge kind of wormhole forms a tunnel through space-time. Conceptually, they are out there, though hard to locate — sort of like Easter eggs in space. We hear of such notions and nod, marveling.

God, though? Resurrection? We find those things hard to believe in, but embracing science doesn’t mean we have to let go of the mystical — they serve two different purposes, two differing pursuits, two ways of trying to understand the universe, what it is, what it means.

Maybe for this Easter, even if we are not quite far enough along the Way to embrace such possibilities, we can at least look with wonder at notions of grace scattered like Easter eggs along our path. Redemption. Renewal. Resurrection. This Jesus who says, “Behold, I make all things new.”

Those are thoughts worth finding.

____________

¹ The earliest manuscripts of the Gospel of Mark end at verse 16:8 — “So they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.”

² See Acts 9:2

Ideas on the Way to Resurrection was originally published on C R Taylor

0 notes

Text

Killing Jesus, Part 1 — A Cliffhanger

Third Sunday after the Epiphany | Luke 4:14-30

Killing Jesus, Part 1 — A Cliffhanger

Everything started so well. Jesus stood in the synagogue of his childhood home, Nazareth, reading from the scroll of Isaiah.

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives

and recovering of sight to the blind,

to set at liberty those who are oppressed,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

All of this, all of these good things, have come to pass, Jesus tells them. So far, so good. If he had stopped there, things might have been ok. He could have gotten up and walked away, but no. He had to elaborate. He had to tell these people that grace extended to other folk. Different people. Foreigners.

Jesus Unrolls the Book in the Synagogue, by James Tissot

That’s when they dragged him out and threw him over a cliff. Well, almost.

They bum rushed Jesus, frog walked him to the edge of a cliff, and they made to throw him over. It didn’t take a lot of planning on their part. Nobody had to stand up and say, Hey, here’s what we can do to him. No, they just did it, as though they had done such a thing before this occasion, these religious folk with an inclination to violence.

It makes you wonder what one might have seen at the bottom, what kind of bones and rags were bleaching in the sun down there. Somehow their reaction feels modern, like something one might hear on the news, an incident involving a fringe religious group, except that the people in this story are not fringe lunatics. They are mainstream, church folk, salt of the earth.

Incidentally, the Lectionary gives the same passage of scripture to both the Third and Fourth Sundays after Epiphany, though the story is split between them. It’s a cliffhanger.

Mark, not Luke, is the Gospel known for using halves of one story to bookend another one. Still, it is worth considering where Luke places this story. Before Jesus visits the peculiarly violent congregation of Nazareth, he was in the wilderness, being tempted by Satan himself. After escaping from the mob, Jesus goes home to Capernaum and so to the synagogue there, only to be met by a man “who had the spirit of an unclean demon.”

It is an odd sandwich, with the faithful people in the middle and demons on either side. Jesus escapes his meetings with demons unscathed, but the religious folk nearly kill him. There is no peace, says the Lord, for the wicked. (Isaiah 48:22)

Temptation in the wilderness, violence in the church — it is no wonder that Jesus did most of his teaching while walking out in the open, along the seashore and in the streets, more like a Greek philosopher than a Jewish rabbi. The people he found there did not think themselves to be so special, so important, in the eyes of God. They knew the real thing when they saw it, and they knew they weren’t it. The congregation gathered on the pews were different than the congregation called together on the street, which leaves us with questions.

Why does one group get so angry so quickly, to the point that they try to throw Jesus off a cliff, unwittingly trying to kill God himself? And perhaps more to the point, to which congregation do we belong?

Next week — Killing Jesus, Part 2

Christ in the Synagogue in Capernaum

Killing Jesus, Part 1 — A Cliffhanger was originally published on C R Taylor

0 notes

Text

A Story About Ordinary Things

Second Sunday after the Epiphany | John 2:1-11

A Story About Ordinary Things

It was only wine and water, nothing unexpected at a wedding, nothing to grab your attention. The first great sign, the first astounding miracle Jesus performs, at least according to the gospel story as John tells it, is done with such ordinary things, changing water into wine, and for an audience who have already drunk enough to make their testimony unreliable.

Of course, nothing is ordinary. And ask any good defense attorney whether party people make good witnesses, or whether a jury will believe a mother testifying for her son.

The Marriage at Cana by Gerard David c.1450/1460

Still, in telling the simple story of a wedding, this Gospel opens our minds to the idea of God — the God of “Let there be light”— at work in the lives of ordinary people like ourselves. Thought about long enough, it is a little odd, a little unsettling. And none of us is ordinary.

Why do we get this story? Why all these stories at all, instead of just a list of assertions, ideas about God, rules about living, that sort of thing — believe these things, do these things? What is it about telling stories, even all these short stories stitched together, that makes the gospels so compelling?

If you tell people what you think, they can agree, or disagree, or perhaps ignore you altogether and forget about it. On the other hand, if you tell them a story, the story gets into their heads, and they are stuck with it.

Stories we hear, whether we believe them or not, have a way of getting past the firewalls of our minds. It’s what we’re hardwired for — ever since the first fires in the first caves, we’ve listened to stories, and we’ve retold them over and over, sometimes to other people, sometimes to ourselves.

So for this week, I’m going to cheat. Instead of writing a post, I’m going to tell you a story. In fact, I’m going to tell you the same story, just tell it a little differently from the way it comes out in the Gospel of John.

Here it is, from my novel I,John. I hope you enjoy it.

Water

I did not know the family, but we had been invited. We were gathered in the courtyard, a group within the group, although Peter was going around talking and laughing, his great shaggy head easy to spot. I was sitting near Jesus in the shade of a fig bush just tall enough to offer a screen from the sun, and I saw Mary making her way toward him before he saw her, although I was never sure what Jesus knew about his surroundings. He picked people from the crowd when I had not seen them, ignored others who were standing in front of him.

Mary could not be ignored. She waved at people across the courtyard and smiled at them, then came and knelt beside Jesus. She reached up and rubbed his shoulder, and I supposed she was happy to see her son. That’s when I noticed two servants had followed her from within the house.

“They are running out of wine,” she said.

Jesus sighed.

“What do you want me to do about that?” he said. “It is not my party, and it is not my time. This is their day. Their party.”

Mary ignored him and waved the servants over.

“Do what he tells you,” she said. Jesus just sighed again, looking around the courtyard. It was only a little theatrical, enough to say, ‘See how much I love her, even when she annoys me.’

He pointed at some large stone jars standing at the wall of the house.

“Go and fill them with water,” he told them. It was not a small task. Each jar would hold a number of buckets of water, and the process would be tiresome in the heat. The servants looked at him, then at Mary. She nodded and shooed them with her hand.

“Go ahead,” she said. “Do what he told you.”

They did not look happy, but they hurried over to a well and began pulling up buckets of water and carrying them to the stone jars. It was warm enough in the courtyard that the sound of the water was welcome. When they had filled all of the jars, they stood waiting to see what idiotic task they would have next. I knew that if this ended badly, we would be leaving quickly, but things never ended badly around Jesus, at least not until that very last thing. I sat still and quiet, waiting like the servants.

Jesus appeared to be lost in thought. Mary nudged him in the side, and he turned to look at the stone jars, wet with the water splashed on the sides and along the tiles near them.

“Draw some out, and take it to your steward,” he said.

They stood with backs straight, looking first at Jesus then across the courtyard at the head servant who already appeared displeased with all the water carrying. Then, dour and resigned, one of them took a dipper and filled it from a jar. Drops fell dark on the ground. With round eyes he stared at the liquid all the while that he walked across the courtyard. The head servant took it and tasted it, the disgust on his face shifting to surprise.

Quickly he sent the man back and told them both to draw more from the jars and to serve it to the guests. Some of them had been watching as well, and the rest certainly noticed when they began to drink the new wine. We would not be leaving quickly after all, it seemed. Mary was enormously pleased and went off to talk to someone, probably to say that she was the mother of the one who had brought the wine they were now tasting.

As I said, things tended not to end badly with Jesus, not until that very bad ending itself. That was a different sort of event anyway, more something that Jesus endured than something he did. This was like the people at the pool, the blind man who stared at my face in amazement. It was a sign, a sign for us, for Mary, and for as many of the people who realized what had happened. At the same time, it was ordinary, just wine being served at a wedding. What was miraculous about that? It was only a miracle if one saw it as a miracle.

Of course, that was always the case, I thought. Maybe those crippled men who got up and walked out of that pool weren’t really crippled, maybe they had been pretending for the sake of being able to beg money from those who worked for a living. It was possible that the blind man was the same, pretending, and when Jesus caught him in his pretense, he had to abandon it. Of course, that would have been a sort of miracle, some would argue, just not one that required the power of God. I think that changing the behavior of men like that would require more power, be the greater miracle. Changing the mind is a greater sign than healing the body.

But I saw that blind man, saw his eyes when he could not see me. And I saw the amazement on his face when he could see me, when I was suddenly the most beautiful thing in his world. I knew things that the people sitting here drinking wine did not know, and even when we told them, some would never believe.

I got up and walked along the row of jars, and I saw my face reflected in the new dark wine.

This post is part of an ongoing three year project based on the Sunday gospel passage from the Revised Common Lectionary. You can find more about the novel I,John here.

Marriage at Cana by Tintoretto, c.1560

A Story About Ordinary Things was originally published on C R Taylor

0 notes

Text

Leaping Toward Christmas

Fourth Sunday in Advent | Luke 1:39-55

Lectionary Project—Third year of weekly posts based on the Gospel reading from the Revised Common Lectionary

A baby kicks in the womb. That’s all that is happening in this story, really, just an ordinary thing. But it is the kind of small ordinary event to which we attribute meaning, a sign, or some superstitious belief from old wives’ tales. A broom falls. A palm itches. A child kicks in the womb.

That’s all it is.

Visitation by Domenico Ghirlandaio. Louvre, Paris.

In that simple kick, two women know portents of the future. They hear angels greeting them. They believe that the first Christmas is coming, before there is such a thing as Christmas. And they give praise to a God whom they have never seen, comfort one another in their faith that all will be well, simply because of a child’s restless dream in the warm darkness of his mother’s womb.

Two expectant mothers, one of them old, one of them young and as yet unwed, sit at the beginning of a new creation story. God is bringing about a new thing, and it starts in these two women who are not seen by anyone in their world as persons of greatness or importance.

There is a powerful dichotomy at work. The low are raised, and the rich and powerful are rejected. God’s value system is different than ours.

“My soul magnifies the Lord…” So begins the famous praise offered by Mary in Luke’s Gospel. The tension is plain in the text. Far from being a simple expression of faith, Mary’s words distill the message of the prophets. Her prophetic word to her world, and to ours, is that the proud shall be scattered, those who rule shall be torn from their thrones, and the rich shall go hungry. It is the gospel told as prophecy and as challenge—God shall favor the humble, empower the weak, feed the hungry. True power is not in governments or bank vaults or armies, the prophets are saying. True power, Mary tells us, is in the ability to create life, not destroy it. And we can see the face of God in every newborn child.

People speak of Mary’s humility, her willingness to submit to what she perceived as the will of God, and they are right to do so. We should also list her among the prophets, like Elijah and Isaiah. In her grace and her humility, Mary gave us words of power and of warning.

In this Advent season, we would do well to look for the dichotomy of the prophets, this tension Mary proclaims at the coming of the first Christmas. If we think ourselves clever, or powerful, or rich and well fed, then Mary is warning us.

Theotokos, they called her, God-bearer, but that was many years afterward, when enough time and enough words had passed to help the early Church see what had happened. When the Christ child was born and God in that moment began the making of a new creation, Mary was still in a stable, with straw for her bed, animals for her companions. In Bethlehem, she was a stranger who had travelled from far away. She was of low estate, no one of power, no one of wealth. And most blessed was she among us all.

Leaping Toward Christmas was originally published on C R Taylor

0 notes

Text

The Gospel of Doing

Third Sunday of Advent | Luke 3:7-18

Lectionary Project—Third year of weekly posts based on the Gospel reading from the Revised Common Lectionary

The Gospel of Doing

John the Baptist was the sort of man who would get extra attention at airport security. Wild, bearded, long haired, wearing odd clothes — he showed every sign of being outside mainstream society.

Of course, he was outside the mainstream. While Jesus would later walk the streets of the cities and sit to teach in the synagogues, even venture into the Temple itself, John left the company of society. He went out into the wilderness to the edge of his civilization. John believed, hoped, that someone else was coming, someone who would come from a world away, and maybe out there, away from the cities and the lights, it might be easier to keep watch on the horizon.

In the wild places near the murmur of the river, John began to catch the attention of anyone who passed, and he began to preach. It may have been what he said, or maybe how he said it, or maybe simply the appearance of this man who happened (that is the word the gospel accounts use — John ‘happened’ — a way of describing the acts of a prophet) somehow drew people to him. They left their towns and villages, left their familiar paths and streets, and they made their way into the wild places to see this wild man.

”What shall we do?” That was the question the crowds put to him when they found him.

His answers were remarkably simple. Share your food with the hungry. Share your clothes with the poor. Do not take what is not yours. John taught a practical theology.

Only his last answer was abstract. Be content, he told them, an injunction not so simple as the others. How should one be content? He didn’t give out instructions.

Perhaps we are content when we choose to be.

That is the implication behind John’s mandate. It is only reasonable to tell us to be content if it is possible for us to comply. We must be able to choose it.

Contentment, then, is not a feeling to be desired—that is a result, not a cause. Contentment must have more to do with how we see the world, what we choose to do in the world or apart from it.

John the Baptist never told anyone to believe certain tenets. The closest thing to dogma he taught was the need to change. The people who came already knowing how to pass a theology exam, those people he called snakes and vipers. It was not an endorsement of mainstream religion.

He didn’t preach what people should believe. He preached what they should do. Rather than admonishing people to be right, he urged them to do right. Perhaps he was confident that faith would follow action, or perhaps he saw no difference between the two.

John preached a gospel of expectation — God is coming into the world, always, perpetually. He preached a gospel of doing — feeding, clothing, sharing — and oddly enough, according to John, these are the things that make smooth the paths on which we might see God approaching. He told people to give. He told them to share. He didn’t tell them to love one another: he told them to act as though they did. He told them to live like Jesus was going to live.

He’s coming, John told them. Make a way.

The Gospel of Doing was originally published on C R Taylor

0 notes

Text

Anchored in Christmas

Second Sunday of Advent | Luke 3:1-6

Lectionary Project—Third year of weekly posts based on the Gospel reading from the Revised Common Lectionary

Anchored in Christmas

The passage from Luke insists on establishing the date, or at least that is what it appears to do. The author grounds what is to follow, anchors it in history, by listing the names and years of rulers—the fifteenth year of the Emperor Tiberius, during the governorship of Pontius Pilate, during the rule of Herod Antipas and of Herod Philip and of the otherwise unknown Lysanias of Abilene, during the priesthood of Annas and of Caiaphas.

In that time, according to Gospel of Luke, the word of God came to John the Baptist. Literally, we are told that the word of God “happened” to John, but one might suppose that the word of the Lord always happens to prophets.

So why start talking about John the Baptist? Why go to so much trouble to establish the historical setting of John’s ministry? After all, it’s the beginning of the story of Jesus. Why go to such trouble to anchor John in history instead?

It’s not about establishing a date for the events, or at least not just about pointing to the year. A date would be just a fact. The setting — the Gospel claims that these things happened in a real world, to real people not in any way that different from ourselves — is more than history or biography. The setting of the story is itself an expression of theology. It tells us something about God.

The story of Jesus is astonishing. In fact, the Christian claim that Jesus was God become human is nearly unbelievable, particularly to us reasonable, closed minded, modern folk—first one must accept the reality and existence of God, not a welcome idea in many circles, and then one must also accept that this God could and would become incarnate in human form. Of course, the notion was not new to the ancient world. The Romans, Greeks, Persians, and many other people before them, told stories of gods who walked on the earth as human beings. There were plenty of tales of the children of gods. One might even say that those ancient stories prepared the way for people to accept the possibility of a man who was also God in ways that would be unthinkable in our modern world.

If we, as Christians everywhere claim, accept the idea that God was doing something new, something never seen before or since, in the life and ministry of Jesus, we are also tempted to think of the Jesus story as an event outside of time, more akin to a meteor falling from space than to anything growing naturally on the earth.

Luke goes out of the way to make precisely the opposite claim. This is no act of God that comes falling like lightning from the sky. This is grounded. This is God growing the miracle of incarnation in a real world, in a particular moment of human history, surrounded by the joys and troubles of humanity.

In a real time and a real place, God called John, that wild and untamed man. In a particular time and place, God happened to John. In that real world, John set about the work he believed God called him to do — preparing a way, making a straight path to the minds and hearts of people who hoped for more out of their lives than work and taxes. John got their attention, even as he prepared the way for someone else to eclipse him.

In responding to God, John the Baptist was covered in the dust of the wilderness, surrounded by anxious people, bound by the laws of repressive Roman overlords and by the practice of his Jewish faith.

Romans. Local rulers. Taxes. Dust. It wasn’t an ideal situation, but it was his reality.

We can take comfort in the historical grounding of John’s call. If John could engage with the experience of God in such a place and time, then the same can be true for us in ours.

No need to wait for a perfect world in order to engage with God — in fact, that might be counterproductive. We do not need great opportunities, perfect connections; we do not need to be perfect people. Look at John. According to the other gospels, John the Baptist roamed the wilderness, ate locusts (the bugs, not the flowers) and dressed in camel hair — he was not what we might today call well adjusted. Even by first century standards, he wasn’t normal.

We begin great and wonderful things where we are, as we are. That is an important part of the good news, the gospel story. Great things may start in the wilderness, covered in dust.

Advent is about making a way, not about waiting for someone else to do it. The season of Advent is about straightening the paths we have, starting from our here and our now.

Christmas, like heaven, may seem to have more to do with one day and some day and the promised land, but it is anchored in the present — our present wilderness.

Advent begins wherever we are.

Anchored in Christmas was originally published on C R Taylor

0 notes

Text

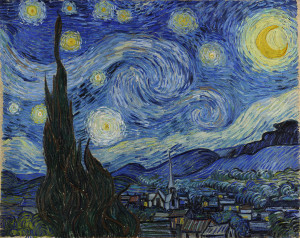

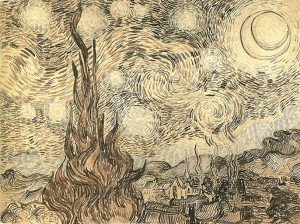

Faith, Religion, and Van Gogh's Starry Night

Reign of Christ | John 18:33-37

Lectionary Project—Part of an ongoing three year project of weekly posts based on the Gospel reading from the Revised Common Lectionary.

Faith, Religion, and Van Gogh’s Starry Night

Pilate was sick of religion. We can also tell, just from his portrayal in John’s Gospel, that Pilate was still bound by it.

“What is truth?” That is what he said when Jesus claimed to be the voice of truth. At least, that is the story that we have from the Gospel. We are not told who else was in the room, who might have reported the conversation. The Gospel claims that one of the disciples, not named, was known to the household of the high priest, that he got Peter and himself inside; perhaps that disciple or someone else was also known within the household of Pilate.

We do not know. Perhaps Pilate himself told the story of what happened between him and Jesus, thinking to absolve himself.

What is truth? It might be the answer of a man who knew the arguments of philosophers and theologians. It might also be the answer of a jaded politician, tired of the lies that surround anyone in power. Likely, it is both.

One of the most interesting points in John’s account is further down, in v.19:8 — Pilate is afraid when he hears accusations that Jesus claimed to be a son of God. It is an interesting response from a man with so much power. The Jewish leaders are angered by implications that Jesus is of God; Pilate is afraid. The Roman pantheon included many gods and many children of the gods. No doubt Pilate had heard the stories from an early age, and even this philosopher who could disparage the concept of truth still clung to his fear of gods.