#church abbey ruins by moonlight

Text

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Even In Death" by Jonathan McFerran on INPRNT

#print#art#fine art#gothic#moon#midnight#grave#ruins#abbey#moonlight#overgrown#grey abbey#death#spooky#ancient#graveyard#church#halloween#ruin#evanescence#INPRNT"

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hold Me Tight Under The Moonlight

Summary: It's 1945 and the war with Germany is officially over. While all of Whitby has its own means of celebrating, Count Dracula has something a little bit more intimate planned for his night with Agatha. A surprise that surely will be memorable.

Chapters: 1/1 *Complete*

Pairing: Dracula/Agatha Van Helsing

A/N: Just a little, fluffy fic for you folks! Thank you again to my partner-in-crime, @mitsukatsu, who makes all of this possible! She is responsible for this glorious cover! Please go to her tumblr and check out all of the fantastic art she does! I hope you guys like it! Feedback is greatly loved and appreciated! -Jen

Read on FFN and AO3

It was well into the night and yet, the atmosphere in the old tavern, Prospect of Whitby, was only growing. Cheers and loud conversations intermingled, all sharing the same theme. The war was finally over. Hitler was dead. Germany had surrendered. And soon, loved ones, some separated for years, would be reunited. It was cause for celebration. Peace would once again find England.

"Can I get you anything, Miss?"

Agatha turned her head to see a young man standing before her. A soldier. Handsome, with a wide smile and the brightest green eyes she'd ever seen. His accent was clearly American. New York perhaps? She'd never sampled one before, as tempting as it always was. Unlike someone, impulse control and resisting temptations came easy to her. But even though she fought it, her throat always burned making it painfully aware of her true nature.

"Oh, I'm quite alright," she assured him with a soft smile. "I don't drink."

"It's the end of the war," the young man laughed. "Can't you make an exception? Why, I…"

"She said she doesn't drink," came a low voice.

The scent of fear knitted with the sweet aroma of the soldier's blood. Agatha didn't need to turn around to know who stood looming over her. She chewed on her lower lip, biting back a grin as Dracula glared menacingly at her suitor. So overprotective. Almost annoyingly so. But she'd be lying if she didn't admit that it was charming in its own way. Not that he ever had a reason to be so possessive. Her heart, though still for decades, belonged to him. Just as his centuries old one was her's.

"I'm sorry," the man stumbled over his words. "I didn't realize she…"

"Wasn't alone?" Dracula finished. "Far from it. Now I highly suggest that you run along. It's never good to stray away from a party. Especially when it's so late."

Agatha rolled her eyes and turned forward, listening as the human scuttled off. She pretended to be interested in a spot on the counter as the other vampire sat beside her. It was rather surprising that it took him this long to locate her.

"Well, I didn't expect to find you here," he commented. "When I invited you for a drink, I hadn't intended on going to a pub."

"I know," she replied, trying to feign disinterest. "I desired a change in scenery. The war is over. What a time it truly is to be alive."

"Yes, yes, I know," the other vampire waved dismissively. "But with such festivities, we are missing out on a great opportunity to savor the diverse nightlife." He always had quite a way to put things. Even making the idea of sucking blood from a helpless human appealing. A trait she both despised and desired in him. "Won't you join me?"

The former nun turned her body just enough so that she was facing the majority of the bar patrons. People watching was something that fascinated her. It still hadn't quite sunken in that she was immortal. That sooner or later, every single being in the room would die. It certainly showed that life shouldn't be taken for granted. An acknowledgement she always did her best to keep in mind.

"Look how happy they are," she mused. "It's good to see that around."

"Your sentimental nature is both alluring and bothersome," her mate huffed. "There will always be more wars, more victories, more celebrations...you'll grow tired of it eventually. Humans are rather predictable."

"Was I?" She questioned, finally meeting his gaze.

"You were...an anomaly," the Count smirked. "A rare specimen amongst a drab populace."

"How poetic of you," Agatha snorted. "I'm surprised it took you centuries to find someone who could stand you."

"Ah, and it's always reassuring to see that both your sarcasm and quick wit have survived far past our first introduction those many, many years back." Dracula grinned, leaning close so that their foreheads touched. "I'd begin to worry if they didn't."

"You have a very odd way of flirting." She remarked, cocking an eyebrow. "One might even find it a little endearing."

"And that someone being you?"

"Perhaps."

She smiled and pressed a chaste kiss to his mouth before pulling away-much to the other vampire's dismay. By dawn, many ships would be docked at the port awaiting to transport soldiers back home-whether that be the United States or elsewhere. But until the sun rose, they seemed more than content to spend their last hours in England here.

"Have you reconsidered my proposal?" Dracula ventured, breaking the silence. "About leaving this establishment and going somewhere more private?"

"Do your intentions involve the consumption of blood?"

"Originally," he admitted. "But I'm assuming that is no longer an option. In any case, I'd at least like to leave here. Go somewhere more fitting. If you'd be so kind as to humor me."

Agatha looked at him thoughtfully. "Where did you have in mind?"

The Count was smiling once more as he extended a hand towards his mate. "I believe it's best that I show rather than tell," he answered. "It'd ruin the surprise."

If she had known that they'd be taking a midnight stroll through the fields, Agatha would've certainly put on different shoes. Her heels sunk into the soft ground, still saturated from the morning's rain and she found herself gripping onto Dracula's forearm to keep from slipping out of them. They'd be ruined for sure, but she didn't mind that much. She'd never really been into material things-something the Count didn't exactly understand. So there wouldn't be any shock if he'd immediately replace them.

"So," the former nun began, cutting through the silence. "Can I at least ask how far we are from your destination?"

"Reasonably close," he answered. "Not much longer now."

They kept walking, the breeze picking up and bringing with it the salty smell of the ocean. It reminded her of home. Of Holland. Of when, as a child, her family would travel to the sea. Good memories she hoped would stay with her as the years passed. That's why she'd grown to love Whitby. Watching as the little seaside town developed over time.

"And here we are!"

It took Agatha a moment to register where they were. More so why than anything else. Before them stood the ruins of what used to be Whitby Abbey. She remembered very clearly when it was severely damaged in the Raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby in 1914. It had been the first time she'd witnessed war. Something that she would never forget.

"The Abbey…" She said slowly, looking at him in amusement. "Are you saying I should rejoin the Church?"

"I was going for the more ironic aspect of it," he smirked. "Though, you did wear that ridiculous habit of yours very well...even if you do look better without it or," and his eyes grew dark. "Without anything on."

"We didn't come up her for just sex did we?" Agatha snorted, arms folded over her chest. "While I'm quite fond of you, I'm not in the mood to roll around in the mud like some pig."

"A very beautiful pig," he added, earning him a smack on his arm. "What? I'm merely being honest."

"Flattery will get you nowhere, Count Dracula," the former nun grinned. "Especially when you're doing a terrible job at it."

"Very well," the vampire sighed. "But we shall be revisiting this subject later. For now, my main reason for bringing you here," he motioned forward. "Ladies first."

The abbey was one of the greatest highlights of Whitby, provided that it offered such a great view of the town and the ocean depending on where a person stood. Agatha stood in the very center of it, watching as lights twinkled in the windows of nearby houses. She felt Dracula join her by her side, his fingers lightly brushing against hers. It truly was a wonderful place.

"Gorgeous," he commented.

"It is, isn't it?" Agatha greed.

"I wasn't referring to the view."

The former nun turned and eyed the Count's crooked smile. Her own lips pursed as he tucked a lock of her hair behind her ear. They stood there silently, gazes locked on one another until a faint noise cut through the air. Music. Distant, most likely from one of the far off houses, but clear enough to be picked up by their heightened senses. Dracula once more held out his hand towards her.

"Might I have this dance?"

In the beginning, Agatha might as well have been born with two left feet with how poorly her skills on the dance floor were. She stumbled. Tripped. On more than one occasion stepped on Dracula's toes. It took months on his part to teach her to teach her to the point where one might consider her remotely decent. But it was worth it. She could now dance, on his lead of course, without feeling like a total fool. And so, with a small smile, Agatha took his hand.

"Are you surprised?"

Dracula watched her closely as they spun gracefully, careful to avoid pieces of stray stone that stuck up from the ground. Their dance floor was far from an ordinary ballroom, but they weren't exactly ordinary people.

"If I had known you planned to take me dancing, I would've dressed better for the occasion," she smirked, leaning into his chest. "Perhaps I was wrong about you lacking in the department of romance. This is rather nice."

"I try my best for you," he grinned. "Emphasis on try."

"And tonight you successed." Agatha complimented, gliding gracefully across the grass. "I'm impressed."

"Oh?" Dracula's movement changed to match the rhythm of the song. "Do I win an award?"

"Yes." A small smile played across her features. "You get to bask in my presence."

Her mate snorted, rolling his eyes. "You are quite the tease, Agatha Van Helsing."

"I am, as you put it, an anomaly." The woman replied, pushing herself onto the tips of her toes. "And you're very lucky to have me."

"I am."

Their lips met and though her blood no longer flowed in the way that a human's did, warmth spread throughout her. Dracula's arms wrapped around her waist as she allowed her eyes to close. There was no fiery passion, no animalistic hunger behind it. It was sweet. Endearing. One of her favorite moments to drink in and savor. Even when she pulled back, Agatha made sure not to break their embrace.

"Well, I suppose I should plan outings like this more often," he chuckled.

"I'm not one to object," Agatha replied, allowing her head to rest against his chest. "Thank you."

"Anything for my love," Dracula murmured, pressing a kiss to the top of her head. "Even if it means I must act mawkish."

"If it is any consolation, I think it's rather becoming," she responded playfully. "I quite enjoy this side of you."

Before Dracula could reply, there was a faint buzz of static before the music, wherever it was being played, switched. A new melody began to float through the air and Agatha's eyes gazed off into the distance. Off to where the horizon was still blanketed by the night.

"Come," she finally said, catching his stare. "You owe me at least another dance before sunrise and I quite like this song. Let's celebrate tonight and however many nights we'll have together to follow. We can both afford to be sappy for now."

Dracula chuckled, his dark brown eyes meeting the blues of hers. "If that's what you want," he smiled, touching his forehead to hers. "Then may I have this dance?"

"Always."

#Dracula#Dracula 2020#Agatha Van Helsing#Dragatha#Dracula x Agatha#Dracula fic#Hold Me Tight Under The Moonlight

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

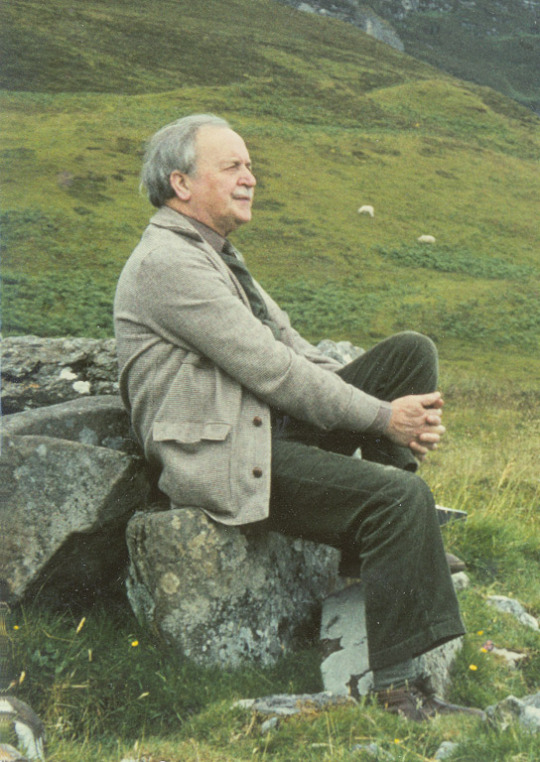

On October 26th 1911 the Gaelic poet, Sorley MacLean, was born on the island of Raasay, the same island my own ancestors originated.

Maclean was born at Osgaig on the island into a Gaelic speaking community. He was the second of five sons born to Malcolm and Christina MacLean. His brothers were John Maclean, a schoolteacher and later rector of Oban High School, who was also a piper, Calum Maclean, a noted folklorist and ethnographer; and Alasdair and Norman, who became GP's. His name in Gaelic was Somhairle MacGill-Eain.

At home, he was steeped in Gaelic culture and beul-aithris (the oral tradition), especially old songs. His mother, a Nicolson, had been raised near Portree, although her family was of Lochalsh origin her family had been involved in Highland Land League activism for tenant rights. His father, who owned a small croft and ran a tailoring business,[12]:16 had been raised on Raasay, but his family was originally from North Uist and, before that, Mull. Both sides of the family had been evicted during the Highland Clearances, of which many people in the community still had a clear recollection.

What MacLean learned of the history of the Gaels, especially of the Clearances, had a significant impact on his worldview and politics. Of especial note was MacLean's paternal grandmother, Mary Matheson, whose family had been evicted from the mainland in the 18th century. Until her death in 1923, she lived with the family and taught MacLean many traditional songs from Kintail and Lochalsh. As a child, MacLean enjoyed fishing trips with his aunt Peigi, who taught him other songs.[9] Unlike other members of his family, MacLean could not sing, a fact that he connected with his impetus to write poetry.

Sorley was brought up as a follower of the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland, now if you think the Wee Free are strict, these guys think that The Wee Free are too lenient, but Sorley says he gave up the religion for socialism at the age of twelve as he refused to accept that a majority of human beings were consigned to eternal damnation. He was educated at Raasay Primary School and Portree Secondary School. In 1929, he left home to attend the University of Edinburgh.

While studying at Edinburgh University he encountered Hugh Macdiarmid who inspired him to write poetry. However, Maclean chose the Gaelic of his childhood rather than Scots.

After fighting in North Africa during World War II he embarked on his life-long career as a school teacher - working in Mull, Edinburgh and Plockton.

Maclean was one of the finest writers of Gaelic in the 20th century. He drew upon its rich oral tradition to create innovative and beautiful poetry about the Scottish landscape and history. He was also an accomplished love poet. However, writing in Gaelic limited his audience so he began to translate his own work into English. In 1977 a bilingual edition of his selected poems appeared - followed by the collected poems in 1989.

His fame as a poet began to spread during the 1970s - helped by the appearance of his work in Gordon Wright's Four Points of a Saltire. Seamus Heaney, who first met Maclean at a poetry reading at the Abbey Theatre Dublin, was one of his greatest admirers and subsequently worked on translations of his work.

One of Maclean's most celebrated poems is Hallaig which concerns the enforced clearance of the inhabitants of the township of Hallaig (Raasay) to Australia. A film, Hallaig, was made in 1984 by Timothy Neat, including a discussion by MacLean of the dominant influences on his poetry, with commentary by Smith and Heaney, and substantial passages from the poem and other work, along with extracts of Gaelic song

In 1990 Maclean received the Queen's Gold Medal for poetry. He died in 1996 at the age of 85.‘.

Tha tìm, am fiadh, an coille Hallaig’

Tha bùird is tàirnean air an uinneig

trom faca mi an Àird Iar

’s tha mo ghaol aig Allt Hallaig

’na craoibh bheithe, ’s bha i riamh

eadar an t-Inbhir ’s Poll a’ Bhainne,

thall ’s a-bhos mu Bhaile Chùirn:

tha i ’na beithe, ’na calltainn,

’na caorann dhìrich sheang ùir.

Ann an Sgreapadal mo chinnidh,

far robh Tarmad ’s Eachann Mòr,

tha ’n nigheanan ’s am mic ’nan coille

a’ gabhail suas ri taobh an lòin.

Uaibreach a-nochd na coilich ghiuthais

a’ gairm air mullach Cnoc an Rà,

dìreach an druim ris a’ ghealaich –

chan iadsan coille mo ghràidh.

Fuirichidh mi ris a’ bheithe

gus an tig i mach an Càrn,

gus am bi am bearradh uile

o Bheinn na Lice fa sgàil.

Mura tig ’s ann theàrnas mi a Hallaig

a dh’ionnsaigh Sàbaid nam marbh,

far a bheil an sluagh a’ tathaich,

gach aon ghinealach a dh’fhalbh.

Tha iad fhathast ann a Hallaig,

Clann Ghill-Eain’s Clann MhicLeòid,

na bh’ ann ri linn Mhic Ghille Chaluim:

chunnacas na mairbh beò.

Na fir ’nan laighe air an lèanaig

aig ceann gach taighe a bh’ ann,

na h-igheanan ’nan coille bheithe,

dìreach an druim, crom an ceann.

Eadar an Leac is na Feàrnaibh

tha ’n rathad mòr fo chòinnich chiùin,

’s na h-igheanan ’nam badan sàmhach

a’ dol a Clachan mar o thus.

Agus a’ tilleadh às a’ Chlachan,

à Suidhisnis ’s à tir nam beò;

a chuile tè òg uallach

gun bhristeadh cridhe an sgeòil.

O Allt na Feàrnaibh gus an fhaoilinn

tha soilleir an dìomhaireachd nam beann

chan eil ach coitheanal nan nighean

a’ cumail na coiseachd gun cheann.

A’ tilleadh a Hallaig anns an fheasgar,

anns a’ chamhanaich bhalbh bheò,

a’ lìonadh nan leathadan casa,

an gàireachdaich ‘nam chluais ’na ceò,

’s am bòidhche ’na sgleò air mo chridhe

mun tig an ciaradh air caoil,

’s nuair theàrnas grian air cùl Dhùn Cana

thig peilear dian à gunna Ghaoil;

’s buailear am fiadh a tha ’na thuaineal

a’ snòtach nan làraichean feòir;

thig reothadh air a shùil sa choille:

chan fhaighear lorg air fhuil rim bheò.

Hallaig

Translator: Sorley MacLean

‘Time, the deer, is in the wood of Hallaig’

The window is nailed and boarded

through which I saw the West

and my love is at the Burn of Hallaig,

a birch tree, and she has always been

between Inver and Milk Hollow,

here and there about Baile-chuirn:

she is a birch, a hazel,

a straight, slender young rowan.

In Screapadal of my people

where Norman and Big Hector were,

their daughters and their sons are a wood

going up beside the stream.

Proud tonight the pine cocks

crowing on the top of Cnoc an Ra,

straight their backs in the moonlight –

they are not the wood I love.

I will wait for the birch wood

until it comes up by the cairn,

until the whole ridge from Beinn na Lice

will be under its shade.

If it does not, I will go down to Hallaig,

to the Sabbath of the dead,

where the people are frequenting,

every single generation gone.

They are still in Hallaig,

MacLeans and MacLeods,

all who were there in the time of Mac Gille Chaluim:

the dead have been seen alive.

The men lying on the green

at the end of every house that was,

the girls a wood of birches,

straight their backs, bent their heads.

Between the Leac and Fearns

the road is under mild moss

and the girls in silent bands

go to Clachan as in the beginning,

and return from Clachan,

from Suisnish and the land of the living;

each one young and light-stepping,

without the heartbreak of the tale.

From the Burn of Fearns to the raised beach

that is clear in the mystery of the hills,

there is only the congregation of the girls

keeping up the endless walk,

coming back to Hallaig in the evening,

in the dumb living twilight,

filling the steep slopes,

their laughter a mist in my ears,

and their beauty a film on my heart

before the dimness comes on the kyles,

and when the sun goes down behind Dun Cana

a vehement bullet will come from the gun of Love;

and will strike the deer that goes dizzily,

sniffing at the grass-grown ruined homes;

his eye will freeze in the wood,

his blood will not be traced while I live.

)

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mina Murray's Journal

11 August, 3 a.m. -- Diary again. No sleep now, so I may as well write. I am too agitated to sleep. We have had such an adventure, such an agonising experience. I fell asleep as soon as I had closed my diary... Suddenly I became broad awake, and sat up, with a horrible sense of fear upon me, and of some feeling of emptiness around me. The room was dark, so I could not see Lucy's bed; I stole across and felt for her. The bed was empty. I lit a match and found that she was not in the room. The door was shut, but not locked, as I had left it. I feared to wake her mother, who has been more than usually ill lately, so threw on some clothes and got ready to look for her. As I was leaving the room it struck me that the clothes she wore might give me some clue to her dreaming intention. Dressing-gown would mean house; dress, outside. Dressing-gown and dress were both in their places. "Thank God," I said to myself, "she cannot be far, as she is only in her nightdress." I ran downstairs and looked in the sitting-room. Not there! Then I looked in all the other open rooms of the house, with an ever-growing fear chilling my heart. Finally I came to the hall door and found it open. It was not wide open, but the catch of the lock had not caught. The people of the house are careful to lock the door every night, so I feared that Lucy must have gone out as she was. There was no time to think of what might happen; a vague, overmastering fear obscured all details. I took a big, heavy shawl and ran out. The clock was striking one as I was in the Crescent, and there was not a soul in sight. I ran along the North Terrace, but could see no sign of the white figure which I expected. At the edge of the West Cliff above the pier I looked across the harbour to the East Cliff, in the hope or fear -- I don't know which -- of seeing Lucy in our favourite seat. There was a bright full moon, with heavy black, driving clouds, which threw the whole scene into a fleeting diorama of light and shade as they sailed across. For a moment or two I could see nothing, as the shadow of a cloud obscured St. Mary's Church and all around it. Then as the cloud passed I could see the ruins of the abbey coming into view; and as the edge of a narrow band of light as sharp as a sword-cut moved along, the church and the churchyard became gradually visible. Whatever my expectation was, it was not disappointed, for there, on our favourite seat, the silver light of the moon struck a half-reclining figure, snowy white. The coming of the cloud was too quick for me to see much, for shadow shut down on light almost immediately; but it seemed to me as though something dark stood behind the seat where the white figure shone, and bent over it. What it was, whether man or beast, I could not tell; I did not wait to catch another glance, but flew down the steep steps to the pier and along by the fish-market to the bridge, which was the only way to reach the East Cliff. The town seemed as dead, for not a soul did I see; I rejoiced that it was so, for I wanted no witness of poor Lucy's condition. The time and distance seemed endless, and my knees trembled and my breath came laboured as I toiled up the endless steps to the abbey. I must have gone fast, and yet it seemed to me as if my feet were weighted with lead, and as though every joint in my body were rusty. When I got almost to the top I could see the seat and the white figure, for I was now close enough to distinguish it even through the spells of shadow. There was undoubtedly something, long and black, bending over the half-reclining white figure. I called in fright, "Lucy! Lucy!" and something raised a head, and from where I was I could see a white face and red, gleaming eyes. Lucy did not answer, and I ran on to the entrance of the churchyard. As I entered, the church was between me and the seat, and for a minute or so I lost sight of her. When I came in view again the cloud had passed, and the moonlight struck so brilliantly that I could see Lucy half reclining with her head lying over the back of the seat. She was quite alone, and there was not a sign of any living thing about.

When I bent over her I could see that she was still asleep. Her lips were parted, and she was breathing -- not softly as usual with her, but in long, heavy gasps, as though striving to get her lungs full at every breath. As I came close, she put up her hand in her sleep and pulled the collar of her nightdress close around her throat. Whilst she did so there came a little shudder through her, as though she felt the cold. I flung the warm shawl over her, and drew the edges tight round her neck, for I dreaded lest she should get some deadly chill from the night air, unclad as she was. I feared to wake her all at once, so, in order to have my hands free that I might help her, I fastened the shawl at her throat with a big safety-pin; but I must have been clumsy in my anxiety and pinched or pricked her with it, for by-and-by, when her breathing became quieter, she put her hand to her throat again and moaned. When I had her carefully wrapped up I put my shoes on her feet and then began very gently to wake her. At first she did not respond; but gradually she became more and more uneasy in her sleep, moaning and sighing occasionally. At last, as time was passing fast, and, for many other reasons, I wished to get her home at once, I shook her more forcibly, till finally she opened her eyes and awoke. She did not seem surprised to see me, as, of course, she did not realise all at once where she was. Lucy always wakes prettily, and even at such a time, when her body must have been chilled with cold, and her mind somewhat appalled at waking unclad in a churchyard at night, she did not lose her grace. She trembled a little, and clung to me; when I told her to come at once with me home she rose without a word, with the obedience of a child. As we passed along, the gravel hurt my feet, and Lucy noticed me wince. She stopped and wanted to insist upon my taking my shoes; but I would not. However, when we got to the pathway outside the churchyard, where there was a puddle of water, remaining from the storm, I daubed my feet with mud, using each foot in turn on the other, so that as we went home, no one, in case we should meet any one, should notice my bare feet.

Fortune favoured us, and we got home without meeting a soul. Once we saw a man, who seemed not quite sober, passing along a street in front of us; but we hid in a door till he had disappeared up an opening such as there are here, steep little closes, or "wynds," as they call them in Scotland. My heart beat so loud all the time that sometimes I thought I should faint. I was filled with anxiety about Lucy, not only for her health, lest she should suffer from the exposure, but for her reputation in case the story should get wind. When we got in, and had washed our feet, and had said a prayer of thankfulness together, I tucked her into bed. Before falling asleep she asked -- even implored -- me not to say a word to any one, even her mother, about her sleep-walking adventure. I hesitated at first to promise; but on thinking of the state of her mother's health, and how the knowledge of such a thing would fret her, and thinking, too, of how such a story might become distorted -- nay, infallibly would -- in case it should leak out, I thought it wiser to do so. I hope I did right. I have locked the door, and the key is tied to my wrist, so perhaps I shall not be again disturbed. Lucy is sleeping soundly; the reflex of the dawn is high and far over the sea...

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpts from H. P. Lovecraft’s commonplace book.

This book consists of ideas, images, & quotations hastily jotted down for possible future use in weird fiction. Very few are actually developed plots—for the most part they are merely suggestions or random impressions designed to set the memory or imagination working. Their sources are various—dreams, things read, casual incidents, idle conceptions, & so on.

—H. P. Lovecraft

-

4 Horror Story

Man dreams of falling—found on floor mangled as tho’ from falling from a vast height.

5 Narrator walks along unfamiliar country road,—comes to strange region of the unreal.

“Here we have fetter’d and manacled Time, who wou’d otherwise slay the Gods.”

7 Horror Story

The sculptured hand—or other artificial hand—which strangles its creator.

8 Hor. Sto.

Man makes appt. with old enemy. Dies—body keeps appt.

11 Odd nocturnal ritual. Beasts dance and march to musick.

12 Happenings in interval between preliminary sound and striking of clock—ending—

“it was the tones of the clock striking three”.

13 House and garden—old—associations. Scene takes on strange aspect.

14 Hideous sound in the dark.

15 Bridge and slimy black waters. [Fungi—The Canal]

17 Doors found mysteriously open and shut etc.—excite terror.

20 Man journeys into the past—or imaginative realm—leaving bodily shell behind.

21 A very ancient colossus in a very ancient desert. Face gone—no man hath seen it.

23 The man who would not sleep—dares not sleep—takes drugs to keep himself awake. Finally falls asleep—and something happens. Motto from Baudelaire p. 214. [Hypnos]

24 Dunsany—Go-By Street

Man stumbles on dream world—returns to earth—seeks to go back—succeeds, but finds dream world ancient and decayed as though by thousands of years.

1919

25 Man visits museum of antiquities—asks that it accept a bas-relief he has just made—old and learned curator laughs and says he cannot accept anything so modern. Man says that

‘dreams are older than brooding Egypt or the contemplative Sphinx or garden-girdled Babylonia’

and that he had fashioned the sculpture in his dreams. Curator bids him shew his product, and when he does so curator shews horror. Asks who the man may be. He tells modern name. “No—before that” says curator. Man does not remember except in dreams. Then curator offers high price, but man fears he means to destroy sculpture. Asks fabulous price—curator will consult directors.

Add good development and describe nature of bas-relief.

27 Life and Death

Death—its desolation and horror—bleak spaces—sea-bottom—dead cities. But Life—the greater horror! Vast unheard-of reptiles and leviathans—hideous beasts of prehistoric jungle—rank slimy vegetation—evil instincts of primal man—Life is more horrible than death.

28 The Cats of Ulthar

The cat is the soul of antique Ægyptus and bearer of tales from forgotten cities of Meroë and Ophir. He is the kin of the jungle’s lords, and heir to the secrets of hoary and sinister Africa. The Sphinx is his cousin, and he speaks her language; but he is more ancient than the Sphinx, and remembers that which she hath forgotten.

29 Dream of Seekonk—ebbing tide—bolt from sky—exodus from Providence—fall of Congregational dome.

30 Strange visit to a place at night—moonlight—castle of great magnificence etc. Daylight shews either abandonment or unrecognisable ruins—perhaps of vast antiquity.

31 Prehistoric man preserved in Siberian ice. (See Winchell—Walks and Talks in the Geological field—p. 156 et seq.)

32 As dinosaurs were once surpassed by mammals, so will man-mammal be surpassed by insect or bird—fall of man before the new race.

33 Determinism and prophecy.

34 Moving away from earth more swiftly than light—past gradually unfolded—horrible revelation.

37 Peculiar odour of a book of childhood induces repetition of childhood fancy.

38 Drowning sensations—undersea—cities—ships—souls of the dead. Drowning is a horrible death.

39 Sounds—possibly musical—heard in the night from other worlds or realms of being.

40 Warning that certain ground is sacred or accursed; that a house or city must not be built upon it—or must be abandoned or destroyed if built, under penalty of catastrophe.

41 The Italians call Fear La figlia della Morte—the daughter of Death.

42 Fear of mirrors—memory of dream in which scene is altered and climax is hideous surprise at seeing oneself in the water or a mirror. (Identity?)

44 Castle by pool or river—reflection fixed thro’ centuries—castle destroyed, reflection lives to avenge destroyers weirdly.

45 Race of immortal Pharaohs dwelling beneath pyramids in vast subterranean halls down black staircases.

Visitor from tomb—stranger at some publick concourse followed at midnight to graveyard where he descends into the earth.

47 From Arabia Encyc. Britan. II—255

Prehistoric fabulous tribes of Ad in the south, Thamood in the north, and Tasm and Jadis in the centre of the peninsula. “Very gorgeous are the descriptions given of Irem, the City of Pillars (as the Koran styles it) supposed to have been erected by Shedad, the latest despot of Ad, in the regions of Hadramaut, and which yet, after the annihilation of its tenants, remains entire, so Arabs say, invisible to ordinary eyes, but occasionally and at rare intervals, revealed to some heaven-favoured traveller.” // Rock excavations in N.W. Hejaz ascribed to Thamood tribe.

48 Cities wiped out by supernatural wrath.

49 AZATHOTH—hideous name.

50 Phleg′-e-thon—

a river of liquid fire in Hades.

51 Enchanted garden where moon casts shadow of object or ghost invisible to the human eye.

52 Calling on the dead—voice or familiar sound in adjacent room.

53 Hand of dead man writes.

54 Transposition of identity.

55 Man followed by invisible thing.

56 Book or MS. too horrible to read—warned against reading it—someone reads and is found dead. Haverhill incident.

57 Sailing or rowing on lake in moonlight—sailing into invisibility.

58 A queer village—in a valley, reached by a long road and visible from the crest of the hill from which that road descends—or close to a dense and antique forest.

59 Man in strange subterranean chamber—seeks to force door of bronze—overwhelmed by influx of waters.

60 Fisherman casts his net into the sea by moonlight—what he finds.

62 Live man buried in bridge masonry according to superstition—or black cat.

64 Identity—reconstruction of personality—man makes duplicate of himself.

65 Riley’s fear of undertakers—door locked on inside after death.

66 Catacombs discovered beneath a city (in America?).

67 An impression—city in peril—dead city—equestrian statue—men in closed room—clattering of hooves heard from outside—marvel disclosed on looking out—doubtful ending.

68 Murder discovered—body located—by psychological detective who pretends he has made walls of room transparent. Works on fear of murderer.

69 Man with unnatural face—oddity of speaking—found to be a mask—Revelation.

70 Tone of extreme phantasy

Man transformed to island or mountain.

71 Man has sold his soul to devil—returns to family from trip—life afterward—fear—culminating horror—novel length.

75 Black Mass under antique church.

76 Ancient cathedral—hideous gargoyle—man seeks to rob—found dead—gargoyle’s jaw bloody.

77 Unspeakable dance of the gargoyles—in morning several gargoyles on old cathedral found transposed.

78 Wandering thro’ labyrinth of narrow slum streets—come on distant light—unheard-of rites of swarming beggars—like Court of Miracles in Notre Dame de Paris.

79 Horrible secret in crypt of ancient castle—discovered by dweller.

80 Shapeless living thing forming nucleus of ancient building.

81 Marblehead—dream—burying hill—evening—unreality.

82 Power of wizard to influence dreams of others.

1920

83 Quotation

“. . . a defunct nightmare, which had perished in the midst of its wickedness, and left its flabby corpse on the breast of the tormented one, to be gotten rid of as it might.”—Hawthorne

84 Hideous cracked discords of bass musick from (ruin’d) organ in (abandon’d) abbey or cathedral.

85 “For has not Nature, too, her grotesques—the rent rock, the distorting lights of evening on lonely roads, the unveiled structure of man in the embryo, or the skeleton?”

Pater—Renaissance (da Vinci).

86 To find something horrible in a (perhaps familiar) book, and not to be able to find it again.

87 Borellus says, “that the Essential Salts of animals may be so prepared and preserved, that an ingenious man may have the whole ark of Noah in his own Study, and raise the fine shape of an animal out of its ashes at his pleasure; and that by the like method from the Essential Salts of humane dust, a Philosopher may, without any criminal necromancy, call up the shape of any dead ancestor from the dust whereinto his body has been incinerated.” [Charles Dexter Ward]

88 Lonely philosopher fond of cat. Hypnotises it—as it were—by repeatedly talking to it and looking at it. After his death the cat evinces signs of possessing his personality. N.B. He has trained cat, and leaves it to a friend, with instructions as to fitting a pen to its right fore paw by means of a harness. Later writes with deceased’s own handwriting.

89 Lone lagoons and swamps of Louisiana—death daemon—ancient house and gardens—moss-grown trees—festoons of Spanish moss.

1922?

92 Man’s body dies—but corpse retains life. Stalks about—tries to conceal odour of decay—detained somewhere—hideous climax.

93 A place one has been—a beautiful view of a village or farm-dotted valley in the sunset—which one cannot find again or locate in memory.

94 Change comes over the sun—shews objects in strange form, perhaps restoring landscape of the past.

95 Horrible Colonial farmhouse and overgrown garden on city hillside—overtaken by growth. Verse “The House” as basis of story.

96 Unknown fires seen across the hills at night.

97 Blind fear of a certain woodland hollow where streams writhe among crooked roots, and where on a buried altar terrible sacrifices have occur’d—Phosphorescence of dead trees. Ground bubbles.

98 Hideous old house on steep city hillside—Bowen St.—beckons in the night—black windows—horror unnam’d—cold touch and voice—the welcome of the dead.

1923

99 Salem story—the cottage of an aged witch—wherein after her death are found sundry terrible things.

100 Subterranean region beneath placid New England village, inhabited by (living or extinct) creatures of prehistoric antiquity and strangeness.

101 Hideous secret society—widespread—horrible rites in caverns under familiar scenes—one’s own neighbour may belong.

102 Corpse in room performs some act—prompted by discussion in its presence. Tears up or hides will, etc.

104 Old sea tavern now far inland from made land. Strange occurrences—sound of lapping of waves—

105 Vampire visits man in ancestral abode—is his own father.

106 A thing that sat on a sleeper’s chest. Gone in morning, but something left behind.

1923

107 Wall paper cracks off in sinister shape—man dies of fright.

110 Antediluvian—Cyclopean ruins on lonely Pacific island. Centre of earthwide subterranean witch cult.

112 Man lives near graveyard—how does he live? Eats no food.

113 Biological-hereditary memories of other worlds and universes. Butler—God Known and Unk. p. 59.

114 Death lights dancing over a salt marsh.

115 Ancient castle within sound of weird waterfall—sound ceases for a time under strange conditions.

116 Prowling at night around an unlighted castle amidst strange scenery.

117 A secret living thing kept and fed in an old house.

1924

118 Something seen at oriel window of forbidden room in ancient manor house.

120 Talking bird of great longevity—tells secret long afterward.

123 Dried-up man living for centuries in cataleptic state in ancient tomb.

124 Hideous secret assemblage at night in antique alley—disperse furtively one by one—one seen to drop something—a human hand—

125 Man abandon’d by ship—swimming in sea—pickt up hours later with strange story of undersea region he has visited—mad??

126 Castaways on island eat unknown vegetation and become strangely transformed.

127 Ancient and unknown ruins—strange and immortal bird who speaks in a language horrifying and revelatory to the explorers.

128 Individual, by some strange process, retraces the path of evolution and becomes amphibious.

Dr. insists that the particular amphibian from which man descends is not like any known to palaeontology. To prove it, indulges in (or relates) strange experiment.

1925

129 Marble Faun p. 346—strange and prehistorick Italian city of stone.

131 Phosphorescence of decaying wood—called in New England “fox-fire”.

132 Mad artist in ancient sinister house draws things. What were his models? Glimpse.

133 Man has miniature shapeless Siamese twin—exhib. in circus—twin surgically detached—disappears—does hideous things with malign life of his own.

134 Witches’ Hollow novel? Man hired as teacher in private school misses road on first trip—encounters dark hollow with unnaturally swollen trees and small cottage (light in window?). Reaches school and hears that boys are forbidden to visit hollow. One boy is strange—teacher sees him visit hollow—odd doings—mysterious disappearance or hideous fate.

135 Hideous world superimposed on visible world—gate through—power guides narrator to ancient and forbidden book with directions for access.

136 A secret language spoken by a very few old men in a wild country leads to hidden marvels and terrors still surviving.

137 Strange man seen in lonely mountain place talking with great winged thing which flies away as others approach.

138 Someone or something cries in fright at sight of the rising moon, as if it were something strange.

140 Explorer enters strange land where some atmospheric quality darkens the sky to virtual blackness—marvels therein.

1926

141 Footnote by Haggard or Lang in “The World’s Desire”

“Probably the mysterious and indecipherable ancient books, which were occasionally excavated in old Egypt, were written in this dead language of a more ancient and now forgotten people. Such was the book discovered at Coptos, in the ancient sanctuary there, by a priest of the Goddess. ‘The whole earth was dark, but the moon shone all about the Book.’ A scribe of the period of the Ramessids mentions another in indecipherable ancient writing. ‘Thou tellest me thou understandest no word of it, good or bad. There is, as it were, a wall about it that none may climb. Thou art instructed, yet thou knowest it not; this makes me afraid.’

“Birch Zeitschrift 1871 pp. 61–64 Papyrus Anastasi I pl. X, l.8, pl. X l.4. Maspero, Hist. Anc. pp. 66–67.”

142 Members of witch-cult were buried face downward. Man investigates ancestor in family tomb and finds disquieting condition.

143 Strange well in Arkham country—water gives out (or was never struck —hole kept tightly covered by a stone ever since dug)—no bottom—shunned and feared—what lay beneath (either unholy temple or other very ancient thing, or great cave-world).

144 Hideous book glimpsed in ancient shop—never seen again.

145 Horrible boarding house—closed door never opened.

146 Ancient lamp found in tomb—when filled and used, its light reveals strange world.

147 Any very ancient, unknown, or prehistoric object—its power of suggestion—forbidden memories.

148 Vampire dog.

149 Evil alley or enclosed court in ancient city—Union or Milligan St.

150 Visit to someone in wild and remote house—ride from station through the night—into the haunted hills—house by forest or water—terrible things live there.

151 Man forced to take shelter in strange house. Host has thick beard and dark glasses. Retires. In night guest rises and sees host’s clothes about—also mask which was the apparent face of whatever the host was. Flight.

1928

153 Black cat on hill near dark gulf of ancient inn yard. Mew hoarsely—invites artist to nighted mysteries beyond. Finally dies at advanced age. Haunts dreams of artist—lures him to follow—strange outcome (never wakes up? or makes bizarre discovery of an elder world outside 3-dimensioned space?)

155 Steepled town seen from afar at sunset—does not light up at night. Sail has been seen putting out to sea.

156 Adventures of a disembodied spirit—thro’ dim, half-familiar cities and over strange moors—thro’ space and time—other planets and universes in the end.

157 Vague lights, geometrical figures, etc., seen on retina when eyes are closed. Caus’d by rays from other dimensions acting on optick nerve? From other planets? Connected with a life or phase of being in which person could live if he only knew how to get there? Man afraid to shut eyes—he has been somewhere on a terrible pilgrimage and this fearsome seeing faculty remains.

158 Man has terrible wizard friend who gains influence over him. Kills him in defence of his soul—walls body up in ancient cellar—BUT—the dead wizard (who has said strange things about soul lingering in body) changes bodies with him . . . leaving him a conscious corpse in cellar.

159 Certain kind of deep-toned stately music of the style of the 1870’s or 1880’s recalls certain visions of that period—gas-litten parlours of the dead, moonlight on old floors, decaying business streets with gas lamps, etc.—under terrible circumstances.

160 Book which induces sleep on reading—cannot be read—determined man reads it—goes mad—precautions taken by aged initiate who knows—protection (as of author and translator) by incantation.

161 Time and space—past event—150 yrs ago—unexplained. Modern period—person intensely homesick for past says or does something which is psychically transmitted back and actually causes the past event.

162 Ultimate horror—grandfather returns from strange trip—mystery in house—wind and darkness—grandf. and mother engulfed—questions forbidden—somnolence—investigation—cataclysm—screams overheard—

163 Man whose money was obscurely made loses it. Tells his family he must go again to THE PLACE (horrible and sinister and extra-dimensional) where he got his gold. Hints of possible pursuers—or of his possible non-return. He goes—record of what happens to him—or what happens at his home when he returns. Perhaps connect with preceding topic. Give fantastic, quasi-Dunsanian treatment.

164 Man observed in a publick place with features (or ring or jewel) identified with those of man long (perhaps generations) buried.

165 Terrible trip to an ancient and forgotten tomb.

166 Hideous family living in shadow in ancient castle by edge of wood near black cliffs and monstrous waterfall.

167 Boy rear’d in atmosphere of considerable mystery. Believes father dead. Suddenly is told that father is about to return. Strange preparations—consequences.

168 Lonely bleak islands off N.E. coast. Horrors they harbour—outpost of cosmic influences.

169 What hatches from primordial egg.

170 Strange man in shadowy quarter of ancient city possesses something of immemorial archaic horror.

1930

172 Pre-human idol found in desert.

173 Idol in museum moves in a certain way.

175 Little green Celtic figures dug up in an ancient Irish bog.

176 Man blindfolded and taken in closed cab or car to some very ancient and secret place.

177 The dreams of one man actually create a strange half-mad world of quasi-material substance in another dimension. Another man, also a dreamer, blunders into this world in a dream. What he finds. Intelligence of denizens. Their dependence on the first dreamer. What happens at his death.

178 A very ancient tomb in the deep woods near where a 17th century Virginia manor-house used to be. The undecayed, bloated thing found within.

179 Appearance of an ancient god in a lonely and archaic place—prob. temple ruin. Atmosphere of beauty rather than horror. Subtle handling—presence revealed by faint sound or shadow. Landscape changes? Seen by child? Impossible to reach or identify locale again?

182 In ancient buried city a man finds a mouldering prehistoric document in English and in his own handwriting, telling an incredible tale. Voyage from present into past implied. Possible actualisation of this.

183 Reference in Egyptian papyrus to a secret of secrets under tomb of high-priest Ka-Nefer. Tomb finally found and identified—trap door in stone floor—staircase, and the illimitable black abyss.

184 Expedition lost in Antarctic or other weird place. Skeletons and effects found years later. Camera films used but undeveloped. Finders develop—and find strange horror.

185 Scene of an urban horror—Sous le Cap or Champlain Sts.—Quebec—rugged cliff-face—moss, mildew, dampness—houses half-burrowing into cliff.

186 Thing from sea—in dark house, man finds doorknobs etc. wet as from touch of something. He has been a sea-captain, and once found a strange temple on a volcanically risen island.

1931

187 Dream of awaking in vast hall of strange architecture, with sheet-covered forms on slabs—in positions similar to one’s own. Suggestions of disturbingly non-human outlines under sheets. One of the objects moves and throws off sheet—non-terrestrial being revealed. Sugg. that oneself is also such a being—mind has become transferred to body on other planet.

188 Desert of rock—prehistoric door in cliff, in the valley around which lie the bones of uncounted billions of animals both modern and prehistoric—some of them puzzlingly gnawed.

189 Ancient necropolis—bronze door in hillside which opens as the moonlight strikes it—focussed by ancient lens in pylon opposite?

1932

190 Primal mummy in museum—awakes and changes place with visitor.

191 An odd wound appears on a man’s hand suddenly and without apparent cause. Spreads. Consequences.

1933

192 Thibetan ROLANG—Sorcerer (or NGAGSPA) reanimates a corpse by holding it in a dark room—lying on it mouth to mouth and repeating a magic formula with all else banished from his mind. Corpse slowly comes to life and stands up. Tries to escape—leaps, bounds, and struggles—but sorcerer holds it. Continues with magic formula. Corpse sticks out tongue and sorcerer bites it off. Corpse then collapses. Tongue become a valuable magic talisman. If corpse escapes—hideous results and death to sorcerer.

193 Strange book of horror discovered in ancient library. Paragraphs of terrible significance copies. Later unable to find and verify text. Perhaps discover body or image or charm under floor, in secret cupboard, or elsewhere. Idea that book was merely hypnotic delusion induced by dead brain or ancient magic.

194 Man enters (supposedly) own house in pitch dark. Feels way to room and shuts door behind him. Strange horrors—or turns on lights and finds alien place or presence. Or finds past restored or future indicated.

195 Pane of peculiar-looking glass from a ruined monastery reputed to have harboured devil-worship set up in modern house at edge of wild country. Landscape looks vaguely and unplaceably wrong through it. It has some unknown time-distorting quality, and comes from a primal, lost civilisation. Finally, hideous things in other world seen through it.

196 Daemons, when desiring an human form for evil purposes, take to themselves the bodies of hanged men.

197 Loss of memory and entry into a cloudy world of strange sights and experiences after shock, accident, reading of strange book, participation in strange rite, draught of strange brew, etc. Things seen have vague and disquieting familiarity. Emergence. Inability to retrace course.

1934

198 Distant tower visible from hillside window. Bats cluster thickly around it at night. Observer fascinated. One night wakes to find self on unknown black circular staircase. In tower? Hideous goal.

199 Black winged thing flies into one’s house at night. Cannot be found or identified—but subtle developments ensue.

200 Invisible Thing felt—or seen to make prints—on mountain top or other height, inaccessible place.

201 Planets form’d of invisible matter.

202 A monstrous derelict—found and boarded by a castaway or shipwreck survivor.

203 A return to a place under dreamlike, horrible, and only dimly comprehended circumstances. Death and decay reigning—town fails to light up at night—Revelation.

204 Disturbing conviction that all life is only a deceptive dream with some dismal or sinister horror lurking behind.

205 Person gazes out window and finds city and world dark and dead (or oddly changed) outside.

206 Trying to identify and visit the distant scenes dimly seen from one’s window—bizarre consequences.

207 Something snatched away from one in the dark—in a lonely, ancient, and generally shunned place.

208 (Dream of) some vehicle—railway train, coach, etc.—which is boarded in a stupor or fever, and which is a fragment of some past or ultra-dimensional world—taking the passenger out of reality—into vague, age-crumbled regions or unbelievable gulfs of marvel.

1935

209 Special Correspondence of NY Times—March 3, 1935

“Halifax, N.S.—Etched deeply into the face of an island which rises from the Atlantic surges off the S. coast of Nova Scotia 20 m. from Halifax is the strangest rock phenomenon which Canada boasts. Storm, sea, and frost have graven into the solid cliff of what has come to be known as Virgin’s Island an almost perfect outline of the Madonna with the Christ Child in her arms.

The island has sheer and wave-bound sides, is a danger to ships, and is absolutely uninhabited. So far as is known, no human being has ever set foot on its shores.”

210 An ancient house with blackened pictures on the walls—so obscured that their subjects cannot be deciphered. Cleaning—and revelation.

213 Ancient winter woods—moss—great boles—twisted branches—dark—ribbed roots—always dripping. . . .

214 Talking rock of Africa—immemorially ancient oracle in desolate jungle ruins that speaks with a voice out of the aeons.

215 Man with lost memory in strange, imperfectly comprehended environment. Fears to regain memory—a glimpse. . . .

216 Man idly shapes a queer image—some power impels him to make it queerer than he understands. Throws it away in disgust—but something is abroad in the night.

217 Ancient (Roman? prehistoric?) stone bridge washed away by a (sudden and curious?) storm. Something liberated which had been sealed up in the masonry of years ago. Things happen.

218 Mirage in time—image of long-vanish’d pre-human city.

219 Fog or smoke—assumes shaped under incantations.

220 Bell of some ancient church or castle rung by some unknown hand—a thing . . . or an invisible Presence.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Abbey Church of Melrose Scotland (1879). #firstedition. Large format work bound in green decorative cloth and featuring gilt lettering on the front. The volume features nine, full-page #illustrated plates of #architecture designs by the #british #architect Frederick Pinches, who won a silver medal in 1870 for these #sketches from the Royal Institute of British Architects. DM or visit link in profile if interested ($200). #bookshop Melrose Abbey, the first Cistercian #Abbey in Scotland, was started in the 12th century and was known throughout Europe for the detail of its #Gothic architecture. Legend has it that the heart of Robert the Bruce is buried at the #church . The famous #poet Sir Walter Scott, financed by the Duke of Buccleuch, whom also oversaw the abbey's restoration, wrote of Melrose Abbey in his narrative poem, The ‘Lay of the Last Minstrel’. (From The Lay of the Last Minstrel) If thou wouldst view fair Melrose aright, Go visit it by the pale moonlight; For the gay beams of lightsome day Gild but to flout the ruins gray. When the broken arches are black in night, And each shafted oriel glimmers white; When the cold light’s uncertain shower Streams on the ruined central tower; When buttress and buttress, alternately, Seem framed of ebon and ivory; When silver edges the imagery, And the scrolls that teach thee to live and die; When distant Tweed is heard to rave, And the owlet to hoot o’er the dead man’s grave,— Then go—but go alone the while— Then view St. David’s ruined pile; And, home returning, soothly swear, Was never scene so sad and fair! . . . . . . . . . #bookaddict #booklover #bookoftheday #books #booksale #booksbooksbooks #bookseller #bookshelf #bookshop #bookslover #booksofinstagram #bookstagram #bookstagramfeature #bookstore #rarebooks #booksabovethebend #giftideas #booksmagazine #history #gothicarchitecture #scotland (at Scotland)

#illustrated#architecture#firstedition#gothic#bookaddict#booksofinstagram#bookstagramfeature#british#bookslover#sketches#books#scotland#gothicarchitecture#abbey#booksbooksbooks#bookstore#poet#rarebooks#bookstagram#booksmagazine#bookshelf#booklover#architect#giftideas#history#bookshop#bookoftheday#booksabovethebend#bookseller#church

0 notes

Text

MINA MURRAY'S JOURNAL

Same day, 11 o'clock P.M. - Oh, but I am tired! If it were not that I had made my diary a duty I should not open it tonight. We had a lovely walk. Lucy, after a while, was in gay spirits, owing, I think, to some dear cows who came nosing towards us in a field close to the lighthouse, and frightened the wits out of us. I believe we forgot everything, except of course, personal fear, and it seemed to wipe the slate clean and give us a fresh start. We had a capital `severe tea' at Robin Hood's Bay in a sweet little old-fashioned inn, with a bow window right over the seaweed-covered rocks of the strand. I believe we should have shocked the `New Woman' with our appetites. Men are more tolerant, bless them! Then we walked home with some, or rather many, stoppages to rest, and with our hearts full of a constant dread of wild bulls.

Lucy was really tired, and we intended to creep off to bed as soon as we could. The young curate came in, however, and Mrs. Westenra asked him to stay for supper. Lucy and I had both a fight for it with the dusty miller. I know it was a hard fight on my part, and I am quite heroic. I think that some day the bishops must get together and see about breeding up a new class of curates, who don't take supper, no matter how hard they may be pressed to, and who will know when girls are tired.

Lucy is asleep and breathing softly. She has more color in her cheeks than usual, and looks, oh so sweet. If Mr. Holmwood fell in love with her seeing her only in the drawing room, I wonder what he would say if he saw her now. Some of the `New Women' writers will some day start an idea that men and women should be allowed to see each other asleep before proposing or accepting. But I suppose the `New Woman' won't condescend in future to accept. She will do the proposing herself. And a nice job she will make of it too! There's some consolation in that. I am so happy tonight, because dear Lucy seems better. I really believe she has turned the corner, and that we are over her troubles with dreaming. I should be quite happy if I only knew if Jonathan. . .God bless and keep him.

11 August. - Diary again. No sleep now, so I may as well write. I am too agitated to sleep. We have had such an adventure, such an agonizing experience. I fell asleep as soon as I had closed my diary. . . Suddenly I became broad awake, and sat up, with a horrible sense of fear upon me, and of some feeling of emptiness around me. The room was dark, so I could not see Lucy's bed. I stole across and felt for her. The bed was empty. I lit a match and found that she was not in the room. The door was shut, but not locked, as I had left it. I feared to wake her mother, who has been more than usually ill lately, so threw on some clothes and got ready to look for her. As I was leaving the room it struck me that the clothes she wore might give me some clue to her dreaming intention. Dressing-gown would mean house, dress outside. Dressing-gown and dress were both in their places. "Thank God," I said to myself, "she cannot be far, as she is only in her nightdress."

I ran downstairs and looked in the sitting room. Not there! Then I looked in all the other rooms of the house, with an ever-growing fear chilling my heart. Finally, I came to the hall door and found it open. It was not wide open, but the catch of the lock had not caught. The people of the house are careful to lock the door every night, so I feared that Lucy must have gone out as she was. There was no time to think of what might happen. A vague over-mastering fear obscured all details.

I took a big, heavy shawl and ran out. The clock was striking one as I was in the Crescent, and there was not a soul in sight. I ran along the North Terrace, but could see no sign of the white figure which I expected. At the edge of the West Cliff above the pier I looked across the harbour to the East Cliff, in the hope or fear, I don't know which, of seeing Lucy in our favorite seat.

There was a bright full moon, with heavy black, driving clouds, which threw the whole scene into a fleeting diorama of light and shade as they sailed across. For a moment or two I could see nothing, as the shadow of a cloud obscured St. Mary's Church and all around it. Then as the cloud passed I could see the ruins of the abbey coming into view, and as the edge of a narrow band of light as sharp as a sword-cut moved along, the church and churchyard became gradually visible. Whatever my expectation was, it was not disappointed, for there, on our favorite seat, the silver light of the moon struck a half-reclining figure, snowy white. The coming of the cloud was too quick for me to see much, for shadow shut down on light almost immediately, but it seemed to me as though something dark stood behind the seat where the white figure shone, and bent over it. What it was, whether man or beast, I could not tell.

I did not wait to catch another glance, but flew down the steep steps to the pier and along by the fish-market to the bridge, which was the only way to reach the East Cliff. The town seemed as dead, for not a soul did I see. I rejoiced that it was so, for I wanted no witness of poor Lucy's condition. The time and distance seemed endless, and my knees trembled and my breath came laboured as I toiled up the endless steps to the abbey. I must have gone fast, and yet it seemed to me as if my feet were weighted with lead, and as though every joint in my body were rusty.

When I got almost to the top I could see the seat and the white figure, for I was now close enough to distinguish it even through the spells of shadow. There was undoubtedly something, long and black, bending over the half-reclining white figure. I called in fright, "Lucy! Lucy!" and something raised a head, and from where I was I could see a white face and red, gleaming eyes.

Lucy did not answer, and I ran on to the entrance of the churchyard. As I entered, the church was between me and the seat, and for a minute or so I lost sight of her. When I came in view again the cloud had passed, and the moonlight struck so brilliantly that I could see Lucy half reclining with her head lying over the back of the seat. She was quite alone, and there was not a sign of any living thing about.

When I bent over her I could see that she was still asleep. Her lips were parted, and she was breathing, not softly as usual with her, but in long, heavy gasps, as though striving to get her lungs full at every breath. As I came close, she put up her hand in her sleep and pulled the collar of her nightdress close around her, as though she felt the cold. I flung the warm shawl over her, and drew the edges tight around her neck, for I dreaded lest she should get some deadly chill from the night air, unclad as she was. I feared to wake her all at once, so, in order to have my hands free to help her, I fastened the shawl at her throat with a big safety pin. But I must have been clumsy in my anxiety and pinched or pricked her with it, for by-and-by, when her breathing became quieter, she put her hand to her throat again and moaned. When I had her carefully wrapped up I put my shoes on her feet, and then began very gently to wake her.

At first she did not respond, but gradually she became more and more uneasy in her sleep, moaning and sighing occasionally. At last, as time was passing fast, and for many other reasons, I wished to get her home at once, I shook her forcibly, till finally she opened her eyes and awoke. She did not seem surprised to see me, as, of course, she did not realize all at once where she was.

Lucy always wakes prettily, and even at such a time, when her body must have been chilled with cold, and her mind somewhat appalled at waking unclad in a churchyard at night, she did not lose her grace. She trembled a little, and clung to me. When I told her to come at once with me home, she rose without a word, with the obedience of a child. As we passed along, the gravel hurt my feet, and Lucy noticed me wince. She stopped and wanted to insist upon my taking my shoes, but I would not. However, when we got to the pathway outside the chruchyard, where there was a puddle of water, remaining from the storm, I daubed my feet with mud, using each foot in turn on the other, so that as we went home, no one, in case we should meet any one, should notice my bare feet.

Fortune favoured us, and we got home without meeting a soul. Once we saw a man, who seemed not quite sober, passing along a street in front of us. But we hid in a door till he had disappeared up an opening such as there are here, steep little closes, or `wynds', as they call them in Scotland. My heart beat so loud all the time sometimes I thought I should faint. I was filled with anxiety about Lucy, not only for her health, lest she should suffer from the exposure, but for her reputation in case the story should get wind. When we got in, and had washed our feet, and had said a prayer of thankfulness together, I tucked her into bed. Before falling asleep she asked, even implored, me not to say a word to any one, even her mother, about her sleep-walking adventure.

I hesitated at first, to promise, but on thinking of the state of her mother's health, and how the knowledge of such a thing would fret her, and think too, of how such a story might become distorted, nay, infallibly would, in case it should leak out, I thought it wiser to do so. I hope I did right. I have locked the door, and the key is tied to my wrist, so perhaps I shall not be again disturbed. Lucy is sleeping soundly. The reflex of the dawn is high and far over the sea. . .

Same day, noon. - All goes well. Lucy slept till I woke her and seemed not to have even changed her side. The adventure of the night does not seem to have harmed her, on the contrary, it has benefited her, for she looks better this morning than she has done for weeks. I was sorry to notice that my clumsiness with the safety-pin hurt her. Indeed, it might have been serious, for the skin of her throat was pierced. I must have pinched up a piece of loose skin and have transfixed it, for there are two little red points like pin-pricks, and on the band of her nightdress was a drop of blood. When I apologised and was concerned about it, she laughed and petted me, and said she did not even feel it. Fortunately it cannot leave a scar, as it is so tiny.

Same day, night. - We passed a happy day. The air was clear, and the sun bright, and there was a cool breeze. We took our lunch to Mulgrave Woods, Mrs. Westenra driving by the road and Lucy and I walking by the cliff-path and joining her at the gate. I felt a little sad myself, for I could not but feel how absolutely happy it would have been had Jonathan been with me. But there! I must only be patient. In the evening we strolled in the Casino Terrace, and heard some good music by Spohr and Mackenzie, and went to bed early. Lucy seems more restful than she has been for some time, and fell asleep at once. I shall lock the door and secure the key the same as before, though I do not expect any trouble tonight.

12 August. - My expectations were wrong, for twice during the night I was wakened by Lucy trying to get out. She seemed, even in her sleep, to be a little impatient at finding the door shut, and went back to bed under a sort of protest. I woke with the dawn, and heard the birds chirping outside of the window. Lucy woke, too, and I was glad to see, was even better than on the previous morning. All her old gaiety of manner seemed to have come back, and she came and snuggled in beside me and told me all about Arthur. I told her how anxious I was about Jonathan, and then she tried to comfort me. Well, she succeeded somewhat, for, though sympathy can't alter facts, it can make them more bearable.

13 August. - Another quiet day, and to bed with the key on my wrist as before. Again I awoke in the night, and found Lucy sitting up in bed, still asleep, pointing to the window. I got up quietly, and pulling aside the blind, looked out. It was brilliant moonlight, and the soft effect of the light over the sea and sky, merged together in one great silent mystery, was beautiful beyond words. Between me and the moonlight flitted a great bat, coming and going in great whirling circles. Once or twice it came quite close, but was, I suppose, frightened at seeing me, and flitted away across the harbour towards the abbey. When I came back from the window Lucy had lain down again, and was sleeping peacefully. She did not stir again all night.

14 August. - On the East Cliff, reading and writing all day. Lucy seems to have become as much in love with the spot as I am, and it is hard to get her away from it when it is time to come home for lunch or tea or dinner. This afternoon she made a funny remark. We were coming home for dinner, and had come to the top of the steps up from the West Pier and stopped to look at the view, as we generally do. The setting sun, low down in the sky, was just dropping behind Kettleness. The red light was thrown over on the East Cliff and the old abbey, and seemed to bathe everything in a beautiful rosy glow. We were silent for a while, and suddenly Lucy murmured as if to herself. . .

"His red eyes again! They are just the same." It was such an odd expression, coming apropos of nothing, that it quite startled me. I slewed round a little, so as to see Lucy well without seeming to stare at her, and saw that she was in a half dreamy state, with an odd look on her face that I could not quite make out, so I said nothing, but followed her eyes. She appeared to be looking over at our own seat, whereon was a dark figure seated alone. I was quite a little startled myself, for it seemed for an instant as if the stranger had great eyes like burning flames, but a second look dispelled the illusion. The red sunlight was shining on the windows of St. Mary's Church behind our seat, and as the sun dipped there was just sufficient change in the refraction and reflection to make it appear as if the light moved. I called Lucy's attention to the peculiar effect, and she became herself with a start, but she looked sad all the same. It may have been that she was thinking of that terrible night up there. We never refer to it, so I said nothing, and we went home to dinner. Lucy had a headache and went early to bed. I saw her asleep, and went out for a little stroll myself.

I walked along the cliffs to the westward, and was full of sweet sadness, for I was thinking of Jonathan. When coming home, it was then bright moonlight, so bright that, though the front of our part of the Crescent was in shadow, everything could be well seen, I threw a glance up at our window, and saw Lucy's head leaning out. I opened my handkerchief and waved it. She did not notice or make any movement whatever. Just then, the moonlight crept round an angle of the building, and the light fell on the window. There distinctly was Lucy with her head lying up against the side of the window sill and her eyes shut. She was fast asleep, and by her, seated on the window sill, was something that looked like a good-sized bird. I was afraid she might get a chill, so I ran upstairs, but as I came into the room she was moving back to her bed, fast asleep, and breathing heavily. She was holding her hand to her throat, as though to protect if from the cold.

I did not wake her, but tucked her up warmly. I have taken care that the door is locked and the window securely fastened.

She looks so sweet as she sleeps, but she is paler than is her wont, and there is a drawn, haggard look under her eyes which I do not like. I fear she is fretting about something. I wish I could find out what it is.

15 August. - Rose later than usual. Lucy was languid and tired, and slept on after we had been called. We had a happy surprise at breakfast. Arthur's father is better, and wants the marriage to come off soon. Lucy is full of quiet joy, and her mother is glad and sorry at once. Later on in the day she told me the cause. She is grieved to lose Lucy as her very own, but she is rejoiced that she is soon to have some one to protect her. Poor dear, sweet lady! She confided to me that she has got her death warrant. She has not told Lucy, and made me promise secrecy. Her doctor told her that within a few months, at most, she must die, for her heart is weakening. At any time, even now, a sudden shock would be almost sure to kill her. Ah, we were wise to keep from her the affair of the dreadful night of Lucy's sleep-walking.

17 August. - No diary for two whole days. I have not had the heart to write. Some sort of shadowy pall seems to be coming over our happiness. No news from Jonathan, and Lucy seems to be growing weaker, whilst her mother's hours are numbering to a close. I do not understand Lucy's fading away as she is doing. She eats well and sleeps well, and enjoys the fresh air, but all the time the roses in her cheeks are fading, and she gets weaker and more languid day by day. At night I hear her gasping as if for air.

I keep the key of our door always fastened to my wrist at night, but she gets up and walks about the room, and sits at the open window. Last night I found her leaning out when I woke up, and when I tried to wake her I could not.

She was in a faint. When I managed to restore her, she was weak as water, and cried silently between long, painful struggles for breath. When I asked her how she came to be at the window she shook her head and turned away.

I trust her feeling ill may not be from that unlucky prick of the safety-pin. I looked at her throat just now as she lay asleep, and the tiny wounds seem not to have healed. They are still open, and, if anything, larger than before, and the edges of them are faintly white. They are like little white dots with red centres. Unless they heal within a day or two, I shall insist on the doctor seeing about them.

LETTER, SAMUEL F. BILLINGTON & SON, SOLICITORS WHITBY, TO MESSRS. CARTER, PATERSON & CO., LONDON.

17 August

"Dear Sirs, - "Herewith please receive invoice of goods sent by Great Northern Railway. Same are to be delivered at Carfax, near Purfleet, immediately on receipt at goods station King's Cross. The house is at present empty, but enclosed please find keys, all of which are labelled.

"You will please deposit the boxes, fifty in number, which form the consignment, in the partially ruined building forming part of the house and marked `A' on rough diagrams enclosed. Your agent will easily recognize the locality, as it is the ancient chapel of the mansion. The goods leave by the train at 9:30 tonight, and will be due at King's Cross at 4:30 tomorrow afternoon. As our client wishes the delivery made as soon as possible, we shall be obliged by your having teams ready at King's Cross at the time named and forthwith conveying the goods to destination. In order to obviate any delays possible through any routine requirements as to payment in your departments, we enclose cheque herewith for ten pounds, receipt of which please acknowledge. Should the charge be less than this amount, you can return balance, if greater, we shall at once send cheque for difference on hearing from you. You are to leave the keys on coming away in the main hall of the house, where the proprietor may get them on his entering the house by means of his duplicate key.

"Pray do not take us as exceeding the bounds of business courtesy in pressing you in all ways to use the utmost expedition.

"We are, dear Sirs, "Faithfully yours, "SAMUEL F. BILLINGTON & SON"

LETTER, MESSRS. CARTER, PATERSON & CO., LONDON, TO MESSRS. BILLINGTON & SON, WHITBY.

21 August.

"Dear Sirs, - "We beg to acknowledge 10 pounds received and to return cheque of 1 pound, 17s, 9d, amount of overplus, as shown in receipted account herewith. Goods are delivered in exact accordance with instructions, and keys left in parcel in main hall, as directed.

"We are, dear Sirs, "Yours respectfully, "Pro CARTER, PATERSON & CO."

MINA MURRAY'S JOURNAL.

18 August. - I am happy today, and write sitting on the seat in the churchyard. Lucy is ever so much better. Last night she slept well all night, and did not disturb me once.

The roses seem coming back already to her cheeks, though she is still sadly pale and wan-looking. If she were in any way anemic I could understand it, but she is not. She is in gay spirits and full of life and cheerfulness. All the morbid reticence seems to have passed from her, and she has just reminded me, as if I needed any reminding, of that night, and that it was here, on this very seat, I found her asleep.

As she told me she tapped playfully with the heel of her boot on the stone slab and said,

"My poor little feet didn't make much noise then! I daresay poor old Mr. Swales would have told me that it was because I didn't want to wake up Geordie."