#because of the theme of performing womanhood and sense of self

Text

thinking about Themes and Motifs and how Tone can be conveyed through the layout of the page

#in other words:#thinking about dress rehearsals by Madison Godfrey#i want to say it’s really post modernist#in how it explores the self and how it conveys that with more than just prose#brilliant book if you ever feel like some poetry and prose that will rip you apart#i feel like rus and rowan would both enjoy it#many of the pieces are written in fractured lines which perfectly show in a visual way the feelings#photography teacher had us do an essay on wether art is defined by the artist or the audience#and i feel like godfrey does a really good job of telling you what they feel and mean by it#and then letting you decide what it makes you feel and means to you#so you get two definitions#the artists and the audiences#and each audience would have a different definition of it cause the stories it tell won’t apply to anyone#because of the theme of performing womanhood and sense of self#so some people will be looking through a window while reading it#while others are inside the room#which them makes me think of a room of one’s own essay/speech#which i need to reread#sorry for the essay in the notes#it’s cause i’m not confident about my own words to write and actual essay#en thinks thoughts#also this was supposed to be about how the work is typeset but i got so sidetracked#this is why my literature essays were never an a grade#i get too sidetracked

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Safe Place

TW/CW: Transphobia, Racism

As a child, my favourite book series was Lemony Snicket's "A Series of Unfortunate Events." Across 13 books and a small collection of extra material, including a pseudo autobiography, Lemony Snicket (or Daniel Handler) detailed the struggles and triumphs of three, hyper-intelligent, orphans, trying to navigate a wicked world. As they end up in rather compromising situations, the children hold onto the hope that they will find, as Handler writes, "the last safe place".

This so called "safe place" was collectively imagined by the children as a santuary nestled away in nature, away from all the injustice and morally corrupt people they've been encountering. There, they would be at peace and protected. However, as they reach this location, they realise by ignoring the treacheries of the world, they would be also trapped. They would be forced to passify their interest in bettering th world and to accept falsehoods as fact. In the end, they acknowledge that nothing can be simply packed into neat boxes -- things are more complex than they appear is the take away.

For a series I started reading in elementary school, and occasional revisit as an adult, I now recognise that these were some intense themes I was dealing with. I bring them up now, because I find myself accidentally in a similar idealistic thought bubble when it comes to "safety". To some extent, like Violet, Klaus, and Sunny -- I flattened the realities of the world we're living in into binaries of "safe" and "not safe". And in doing so, I left myself in quite a vulnerable position and I suppose this essay is how I am processing it.

It's been almost 8 years since I've come out as non-binary. It happened in a quite cliche way as I often joke -- with a mental breakdown and shaving all my hair off during my year abroad. With a buzzcut, I struggled a lot with my image and understanding of self. I realised I hid a lot of my frustrations and confusions about performing womanhood, woman-ness, and everything in between behind my long hair.

Growing up, both my parents were very militant in this way about femininity. My mother's insights felt more like a typical assertion of either my sister or I being in her image. I also think, as I grow older, it had a lot to do with her experience under the Khmer Rouge regime where they cut all her hair cut as an attempt of standardisation under communism plus a detterent for lice. Either way, long hair, specifically on me, meant a lot to my mother.

On the otherhand, it meant a lot to my father as well -- though in a more annoyingly patriarchal sense. Some gems he said to me a sa child, which now I realise were a part of my gender unraveling of sorts, include: "You're a girl, you need to have pretty long hair." "You're a princess, you can't be anything else." "You can't skate because you'll mess up your legs and men won't like that." What a guy.

One of my cousins was equally as culpable in my gender-unraveling. She used to bully me, my sister, and my other cousin using nicknames meant to harm us. She used to call me "boy" because she felt that I wasn't "girl" enough. Simplistic, enough. Straight to the point. I was definitively not-girl.

Regardless, and expectedly, I resented all of that. It took me 12 years of being out of the closet (knew I was a little fruity at 10 years old, but who wouldn't be after doing so much theatre and being around so many virbrant human beings?) and a handful of gender studies courses to realise I was, well, a bit different. I had my "moment". I shaved off all my hair, focused on performing adrogyny, and updated all my social media account bits where you could add pronouns. I had a very underwhelming conversation with my family members, who still occasionally misgender me to this day. I embraced my perpetual struggle with gender quite openly.

Throughout my graduate studies, I met many wonderful queer people who nourished and celebrated the essence of me that I was still figuring it out. I am grateful for that. However, this journey was not without issues. Upon moving to Italy I faced an impossible struggle with a gendered language and way of life. I found solice in queer-coded spaces like roller derby and rollerskating. Somewhere along that assimilation into my "Italian" layer of myself, I stopped being andrognyous. I stopped thinking that I had to care, because people were already getting EVERYTHING wrong about me because I wasn't fluent in Italian. My appearance of being brown and a migrant (who sucked at Italian) superceded my priority to be acknowledged and identified by my queerness. It was just another confusing layer for most people who weren't that close to me anyway.

It's not to say I have no friends in Italy, because that is factually untrue. It is simply to say that I acknowledge that in the midst of my actual combatative moments of racism, ableism, and arguable emotional trauma from certain authority figures, that I was not experiencing myself, and therefore my gender, in full. I was a shell of a person. I often reflect on this in relation to my romantic break-up with my ex. I think "Well do I blame him? I was a shell of a person during my PhD so why would I want to stay together while he turns into a shell?" Perhaps that just something I tell myself to sleep at night, but to be clear: I am very happy and I wish him all the best in his personal journey.

Anyways, when I received my first academic position, I decided I was going to re-assert my claim towards my gender. I openly explained I was non-binary, to everyone. I was not going to be supressed by the social structures around me, and quite frankly I think the Netherlands was quite supportive of that (or so I thought). In my eyes, I was reclaiming control of myself, after years of well, not being myself.

So far so good I thought. Nothing egregious happened. Somehow I was expecting people to be very actively transphobic, I mean transphobes are EVERYWHERE. What transpired next, is a bit more slow burn, and harmful in its own minute ways.

In class and to my peers I always emphasise that I don't "keep score" for misgendering. I don't. However what I curiously noticed is that by being open about being non-binary, there was a shift in "carefulness" and emotional labour. More times than not, I ended up consoling people for misgendering me, despite me being very open that it was a joint learning process. I had more people looking at me for validation that I personally judged them to not be a shitty person. I had to tiptoe around conversations about LGBTQ+ and "gender stuff" because everyone's eyes were bulging in my direction whenever it came up. In some way, it felt like they were trying to gauge "how far" I am on the radical-queer-human-political-spectrum. Um yeah, okay, we're all a monolith I guess.

As a lecturer it's very public-facing and intimate. My whole job is being on display for students to stare at, contest, and pick at. I am the first point of contact when they're pissed at course work, methods, or anything relating to their learning. I'm not afraid of this -- of course. As a performer in cabaret, drag, and an avid science communicator. I'm used to being in the spotlight. Also, as someone who has fought very ruthlessly to escape my marginalising contexts, I'm used to it. However, this does not mean I'm fully equipped to handle every situation nor be capable of enduring long spans of pain and suffering.

And yet here we are. I have recently come to face with situations which have caused me to critically reflect on, and genuinely feel pain about the dual responsibility that comes with being out, and open, as "the queer lecturer". Much of the criticism from the "far right" (whatever that could mean) is that we're in an age where "everyone is queer". This always makes me laugh, naturally. We have always existed. LBGTQ+ people have always existed! We were just actively ignored, oppressed, and murdered throughout history. Do you know how terrible that is? Imagine having the capacity to just acknowledge that you have the opportunity to exist without thread of being senselessly harmed, outright murdered, or a focal point of distress and shame for loved ones. Imagine being able to just be, without having your guard up. Imagine. Imagine the toll this has on LGBTQ+ people every second. I'm not here to fetishise my own sadness nor other LGBTQ+ people. I'm just here to ruminate a bit on the weight which many of us, carry internally.

I feel that one of my responsibilities is to be an example to my students, but also a resource for those who relate to me and my identities. I am a safe place for people like me. That's so much work isn't it? Not only am I bound to be a good educator, I'm also entangled in the micro-politics of being a "good" person to so many kinds of people. I'm a "box-checker" for crying out loud. I'm first generation American and university student. I'm brown. I'm queer. I'm disabled. I'm an immigrant. I'm from a working class background. My parents are refugees. I'm probably some sick "progressives" wet dream. These are the pains I carry, histories which shape the very foundation with how I see, engage with, and experience the world. It's so much.

It's impossible to please everyone. I know that. I'm sure everyone knows that to some degree. But all I wish, genuinely, as I lay here very sick with the weight of the stress I am feeling on my entire being that I could stop apologising to everyone for being human. Even when I am physically sick from stress and pressure, it is impossible for me to tear myself away from "work". This just links back to my reflections on burning out doesn't it. Have I begun to burn out again? Is this the initiation of another unraveling? The GENDER edition?

I'm not sure. I hope not. Because I learned nothing before, so what can I learn this go around? Pedro in his attempts to console me these last few days remarked "I'm sure you'll learn something at the end of this." Will I? Will I learn to be "stronger" perhaps? Why must I be hard when I am so effortlessly soft? I enjoy my tenderness within the world, it allows me make such meaningful connections with ideas, people, and things.

In this moment of concern I wanted to shave my hair again. My mom always told me that in Khmer culture, we shave our heads when there has been a great pain. People often do it as a part of funeral rites, for close family members. I watched my aunts, uncles, and cousins shave their heads when my grandpa passed away. When my mom went through a fissure in her relationship with a sibling, she shaved her head. It is how I guess, "my people" and I mourn and grieve. If I shave my head, will people stop misgendering me? If I shave my head will my students see me as a "stronger" resource or "safe place"? These are some of the thoughts that rattled my brain. I haven't cut my hair yet, but I'm still thinking about it.

0 notes

Text

hey btw I have two big questions about XG that prolly don't have an explicit answer but I don't really hear the fandom discussing:

1) like... how aware is the team/the members of what, to me and prolly most culturally western queers, comes off as queer dogwhistling? Are they intentionally courting that crowd or is some of it cultural ignorance? Is there enough of a distinction in korean/japanese culture from western culture to distinguish between queerbaiting and queer dogwhistling (the first being cowardly dodging committing to queer support, the second being intentionally dogwhistling to maintain a mainstream voice while supporting queerness when the mainstream otherwise wouldn't)

(I know thats more than one question, but its just clarifications on what would otherwise be a quick yes or no)

and 2) is this not talked about because its just a kpop thing I don't understand or are some of these symbols/actions just common in the kpop culture to the point where its cultural meaning is lost/different?

Like the TGIF MV has the very gender non-conforming but misguided bathroom sign that became a minor meme a while ago (m, f bathroom signs then a symbol mixing both, then an alien with related text) which fits the theme of "aliens" that they are going for but also feels like an escalation from their general vibe of "be free to be what you are, and be stronger for it"

This just seems the most obvious to point out. One thing that initially worried me with the group is their constant reassertion of "womanhood" (Mascara, GRL GVNG, lit every song) which sorta yells TERF energy alongside Mascara's specifically heteronormativity. To me, because of my lack of previous kpop/jpop/c-pop exposure, I forgave this is different steps of queer cultural acceptance and tried to set more lax expectations. Except as time went on, I noticed that beyond a few "gendered" references to their attractiveness (I look so lavish, dont be fooled by pretty faces, etc, all only arguably gendered in english) they don't specifically work to define womanhood in the way I would expect.

GRL GVNG is an easy to explain example. Despite the song constantly reaffirming that these are women, their crew are women, and "female empire" there isn't really some affirmation of what that is besides... just what they are calling themselves. To hammer in the point, exchange each gendered word for the male alternative and the song doesn't make any less sense. To me, this could still be an example of TERF energy, but it comes off as specifically intending to compare themselves to what is often viewed as a distinct genre - boy groups, and undermine the expectations of what a girl group is supposed to be.

It FEELS less like "women can be strong too" and more like "we are strong, sucks you would assume differently" and I wonder how intentional that distinction is?

Not to mention they've hosted clearly queer fans on their publicly released content, but this one I am less confident in pointing out since this could simply be the differences of cultural gender expressions making XG more ignorant and/or kpop at large doing the same thing without it being meaningful.

Maybe I am imagining it as well, but the most tenuous evidence is that they sometimes put a LOT of distinct emphasis on phrases like "Be your truest self" and "celebrate diversity" among other (perhaps dated) queer catchphrases with some really coy interactions between the girls that sit in the blurred line of platonic social behavior.

Ofc I WANT the performers I am invested in to be surprisingly queer friendly, and I am aware of confirmation bias. Worst case scenario is my instinct about TERF energy is correct but the middle ground would be that all of this is mostly accidental but not antithesis to what they want to convey.

I know young kpop groups are very intentionally private about their personal lives, especially regarding sex and dating (for kinda gross reasons, but tbh everyone is better off despite what I say next) but I am dying to find out if Jurin or Harvey are queer or not because it seems to me like the other girls are being coy about those two in some way (either together or individually) and I just want to confirm its that or not that god damnit.

#xg#this is just a personal rambling blog#but in this specific post I wouldn't mind the input of someone more immersed in their culture than I#but if you stumble on this I am just musing and not trying to make a declaration#but also if I said something out of left field here then I also welcome those comments#I dont wanna pretend I'm a competent dissector of queer discourse lmfao just my experiences being queer#and trying to be gentle in how I approach and appreciate aspects of a culture I am unfamiliar with

0 notes

Text

They’ve got a bad reputation (they’ll get a standing ovation) part 2

HI HAVE I, TOLD YOU, THAT, @nottesilhouette IS THE MOST FRIGGEN AMAZING WRITER IN THE WHOLE WORLD? God...why do we do this to ourselves, friggen 3400 word story in the span of 2 days...this is entirely exclusively my fault pay no mind Read part 1 here. Happy @felinettenovember y’all, time for slep!

...oh, dear gods, why is Felix here? The spotlight burns into his face like shame, regret bubbling up in his stomach. He doesn’t remember challenging Marinette but he has, apparently, and now everyone’s watching and he has to-- he has to-- fight. Defend himself.

Or breathe, if he can manage it.

One seems easier than the other. Well, here goes nothing. Felix steps forward and calls engarde.

“Ophelia did nothing but obey the men in her life!” He cries, stepping forward, gesticulating wildly. The crowd gasps, and Felix doesn’t understand why until he realizes he's still holding the sword prop, white-knuckled grip around its hilt. Marinette’s eyes go wide with surprise and Felix nearly blurts out an apology right there. But then a glint of something sharper flashes in her gaze, burning with determination and suddenly Felix isn’t feeling quite so confident. It’s too late to quail now. He steps forward and matches her, still talking. “She’s hardly enough of an independent person to qualify as a character.”

“What would she be, then?” Marinette’s voice is steady, calm, and Felix is wildly, irrationally envious of it. He can’t work out how to make his statements come out smooth, suave like she’s managed, so he goes for the next best weapon: rage.

“She’s little more than a symbol, a prop,” he spits, and the crowd reacts appropriately. Something in his chest loosens at the idea that he’s performed correctly. Something in his heart wrenches.

Marinette sends him a snide look. “You would know. You’re a model mannequin.”

They’re circling each other now: Felix is brash, forceful, cutting broad slashes through the air with each sweeping generalization he makes. Marinette is steady, precise, pulling apart the stitches of his defense with needle-fine precision. His pulse quickens; a glance at the audience shows she’s winning their favor. This isn’t the clever riposte and quick banter they expected, and Felix is coming across as dim-witted at best.

“Well, what is she then? You have so many judgements, it’s time you raised an opinion of your own-- or do you have no policy but to raze mine?” Felix pushes her back, scrambling for repost. He needs to be interesting, he needs to be clever, he needs to-- turn it back onto Marinette before the crowd realizes he’s faking, that he doesn’t want to be here, that he’s… scared.

His tongue sours at the words, and he hates himself for saying them. Marinette shoots him a glare full of challenge, and for an instant he considers conceding right there. Marinette believes so strongly in her cause, and Felix is desperate to apologize, to reconcile, to just acknowledge the points she’s making. But he’s trapped now, caught in the reputation he’s built for this audience and his own pride, and he has nowhere to go but forward.

Or backwards, apparently, because with each point Marinette makes, crisp and concise and clear, Felix finds himself frantically retreating further and further.

“Ophelia is the only person in the play who recognizes that Hamlet needs help.”

“That’s not true--”

She cuts him off with a slice. “She’s the only person who notices and tries to stop him, who cares enough to call him out on his actions, to hold him accountable to the promises he made before his mad plan, to who he used to be.”

“The entire argument is milquetoast--” He stabs desperately.

“They speak of beauty and reputation, of expectations and the way one’s actions will never outweigh the image others have of them.”

“They speak of madness and prostitution!”

They’ve become locked in combat now, their blades darting in the scant space their words leave behind. The crowd presses forward, squeezes the stage almost to bursting. Nino presses his face to the camera lense, not wanting to miss an instant.

“The argument is framed against women but its themes are centered on Hamlet’s own realization of the position he’s found himself in. It breaks the adrenaline rush long enough to show him, in all his grief and desperation, the reality he’s constructed for himself. They speak of agency!”

“Ophelia has none!”

“Ophelia reminds him that he does!” Marinette’s voice finally raises. “Ophelia reminds Hamlet who he is, what he has, if only for a moment. Ophelia grieves for him, for his loss: of his father, of his sanity and dignity and agency. She acknowledges that he is a liar, but remembers the man he used to be, the person he put work into being.”

“She laments the loss of his attention, nothing more.”

“To write her statements off as such discounts the tone and the manner with which they are intended; she is returning his madman’s accusations with compassion and reason, she is the only person who has done so, who will ever do so.”

“Why should I take her seriously when no one else does?!” It’s a mad, desperate response as he finds himself teetering at the edge of the stage, and he’s unbalanced. He swings again, unhinged.

“None of the men in her life-- not her father, not her brother, not god himself-- take her seriously until she dies.”

“She trips into a river.” Finally, Felix is in charge of this conversation; this, Marinette cannot deny. It is his strongest point, and the only point that matters. He steadies himself, holds his sword like a shield to defend his statement.

“Her death is not an accident. Her death is the culmination of the climax. Her death is the reason anyone stops long enough to notice how far gone Hamlet is! Her death tethers Hamlet to the person he used to be, who loved her once, who remembered what it felt like to choose what he did and who he was.”

“That makes her nothing more than the physical manifestation and harbinger of Hamlet's descent into madness,” and Felix puts on a smirk because he knows he should.

Felix wishes he was being honest, passionate the way Marinette is being. Felix wishes her voice didn’t seem so far away, calling from a world he remembers existing in but can’t find his way back to anymore. Felix wishes he was talking to her in a realm even close to reality instead of the mirage he’s operating in, desperate not to fall through.

Instead, he steps forward from the edge of the stage and keeps his sword aloft. “She’s trapped in the societal confines of traditional womanhood. She’s nothing more than a woman in a world where that doesn’t matter.”

“You’re right.”

Marinette stops moving forward to meet him, drops her arm. Felix is thrilled, and sick and confused, doubly so when he notices the ferocity in her expression. It is not one of someone who has given up. It is one of someone who is about to pounce.

“You’re right, she is nothing more than a woman in a world where that doesn’t matter. No one cares what she has to say. So she makes it matter. She dies, and she is finally heard. You’re right, and she’s a genius for the way she wields it like a weapon.” Marinette smirks, matching his smugness with self-assured pride, and taps his wrist with her sword. His own slips easily out of his grasp, and he trembles; with what emotion, he cannot place. “Being able to do the work of all these men in 58 lines doesn’t make her less of a character, Felix. It makes her more of one, and more power to her for what she’s able to notice that no one else will. It’s not her fault men can’t manage it.”

Felix finally snaps. “My sense is not less than yours!”

Marinette pauses, and very very slowly, grins. It’s terrifying, predatorial. She rakes her gaze down his body, and he shivers. “I had thought to agree but this battle of wits has proven very much so the opposite. When she blows him a kiss and winks, Felix collapses where he stands.

It’s over. The tension the assembled students have been holding in their collective lungs for the last five minutes erupts into cheers and thunderous applause.

“Bravo, bravo.” says Nino, pushing through the crowd, most of whom are still frantically scribbling in their notebooks. Felix can scarcely bring himself to look up, his face burning with humiliation. The room around him is rapidly becoming a confusing blur of angry lights and prying eyes.

“You guys were amazing, I’ve never seen anything like that before! Honestly I should turn this in just like that.” Nino moves around to get a few more shots of their faces, lit up under the harsh theatre lights.

“No way!” shouts someone from the crowd, “I’m turning it in first!”

“--can’t believe how easily Marinette just eviscerated Felix! I thought he was good at literature but--”

“--she’s so clever, he could barely keep up--”

“--he’s not very good at this, is he--”

Someone else laughs and soon the whole crowd is bickering, arguing over who will lay claim to Marinette’s mental prowess and Felix’s mortification.

“Enough, ALL of you! That was completely uncalled for. This wasn’t for you to take advantage of. None of you-- none of you-- bothered to state your own position, your own opinion. All you did was encourage my attacks, which were honestly in poor form.” Marinette hardly stops to breathe. “And anyways, I’m only more coherent because I’ve done weeks of research on this character. Felix kept up to someone who wasn’t just thinking on her feet, and his points still had credibility-- do you know how many literary analyses I’ve read on his position just to try and work out how to defend mine?” Marinette leans over and offers Felix a gentle smile and an outstretched hand. He gratefully accepts.

Felix takes her hand and pulls himself up with it, and stands shoulder to shoulder with her, looking out at the sea of chastised faces. “And now you think you can turn in our work-- her work, really-- and our performance as your own as if you have any claim to it-- it’s disgusting. Marinette poured herself into caring about this, and… and I should’ve listened to her, but I don’t get to take credit for the work she’s done to be this person. I need to do the work myself. You’re manipulators and thieves if you think you deserve any part of what she’s done.”

“Hey, everyone is manipulated by something. Hamlet, Claudius, Horaito… you would know, right?” Marinette looks at him again, soft and shy and concerned through her lashes.

Felix swallows hard, glances at the cameras still rolling. Yeah, he would know.

“Thank you.” He says, stumbling and trying to hide the way his legs are shaking. “I, um… I guess I’d better put these swords away before someone stabs themselves.”

Nino slaps a hand on his shoulder so hard he nearly falls back down again. “Felix, my man! Get that grumpy black uniform off you!”

“Um… what?” Felix turns in confusion, head still spinning.

“You, my friend, are stage-hand no more! We’re still missing a Hamlet, and I know I’ve found the perfect one right here!”

“...WHAT?!?”

As the world around him starts to blur, Marinette slips her hand into his and squeezes, shooting him a fond, amused grin. “You’re going to do great, Felix. I’ll see you on stage.” She presses her lips to his cheek, soft, warm, and… the scene fades to black to the sound of cheering.

#felinette#battle of wits#felinette november#felinette month 2020#MusicFrenDoesWords#aaaaaaaa#nottesilhouette is just hamelton#but a good person

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taylor Swift And The End Of An Era

Love her or hate her, Taylor Swift embodied the contradictions of the decade in pop music

“I’m so sick of running as fast as I can,” Taylor Swift sings in the chorus of “The Man,” a song from her latest album, Lover. She chose the up-tempo tune to open her “Artist of the Decade” medley at the AMAs last month, and it’s a return to familiar Swiftian themes; she claps back at unspecified, sexist critics who fail to acknowledge her “good ideas and power moves.”

Whatever one might think of Swift’s underdog complex, it’s not surprising that the end of the 2010s finds her exhausted. Her transformation from tween country sensation to tabloid-friendly pop star to polarizing Twitter talking point and, finally, to celebrity supernova, required — at the very least — plenty of stamina.

There’s no question that straight white femininity still occupies a privileged place in the cultural landscape, which helped pave the way for Swift’s rise and decade-long pop dominance — even as she became a zeitgeisty symbol of that privilege and a target for those seeking to contest it. Yet as many of her similarly situated peers have faltered, she has endured as one of the last pop behemoths of her kind.

Time and again Swift strategically read and rode the decade’s cultural waves, deciding not just which trends and genres to jump on but, perhaps more importantly, what to pass on. As pop music became feud-centric reality television, there was Taylor; as stan culture transformed the way listeners interacted with performers (and each other), there was Taylor; as artists’ rights in the streaming era entered the conversation, there was Taylor; as politics infiltrated music, there was (sort of, eventually) Taylor.

There are definitely plenty of other contenders for Artist of the Decade (a title both the AMAs and Billboard recently bestowed on Swift) — artists who have hugely impacted pop music over the past 10 years and managed to ride out the seismic, industry-wide shifts they’ve contained, from Beyoncé to Lady Gaga to Kanye West. But you don’t have to think Swift was the “best” or even most significant artist of the decade to acknowledge that her cultural domination, and her ability to pivot and reinvent herself, captured many of the defining tensions of pop music over the last decade.

It’s hard to remember (in internet years) that before 2010, Swift was just a teen pop star and not yet a cultural lightning rod. She was already taken seriously as a musician and had plenty of cultural capital coming into the decade; in 2009, having already won Artist of the Year at the AMAs, she was about to accept a Video Music Award for Female Video of the Year when Kanye infamously interrupted her speech. In early 2010, she won Album of the Year for Fearless at the Grammy Awards, beating out Beyoncé and Lady Gaga.

Her early stardom revolved mostly around the fact that she was a precocious young country artist who wrote her own songs, without the risqué edge or sexy-but-wholesome cognitive dissonance of someone like an early Britney Spears to worry white parents and inspire pearl-clutching tabloid magazine covers. And it wasn’t really until Speak Now — when Swift was already a mainstream star but still categorized as country — that she began teasing the media and her fans about the ways her autobiographical lyrics mapped onto her real life, especially regarding the men she was dating.

People are still wondering whether Alanis Morissette’s “You Oughta Know” is about Uncle Joey, so it was startling for a young woman songwriter and musical celebrity of her commercial reach to use her songs to consistently craft such intimate stories about such equally public men, including Joe Jonas, Taylor Lautner, and John Mayer. And there was something uniquely bold about the way Swift started using her confessional songwriting and melodic sensibility to “get the last word” on her relationships, as People magazine framed it in her first cover story.

People hardly batted an eye in 2018 when Ariana Grande’s first No. 1 hit, “Thank U, Next,” literally name-checked her list of ex-boyfriends, and that’s in no small part because of Swift. Because even as reality TV stars like the Kardashians and Real Housewives were figuring out how to create multiplatform storytelling through social media, Swift was already pioneering the strategy in the big pop machine. Yes, she opportunistically used this to shame exes, create fodder for talk shows, and garner magazine covers; and even then, it raised some hackles about the way she was using her power. But it was undeniably compelling theater, and even nonfans were watching.

That multiplatform mixture of music and drama wouldn’t have succeeded without the undeniably catchy earworms Swift’s diary entries were wrapped in, or without the devoted fanbase of Swifties that she cultivated online. This all helped her break chart records with her most explicitly pop albums, including 2012’s Red and 2014’s ’80s-inspired 1989. The latter garnered the biggest first-week sales for a pop album since Britney Spears in 2002, helping Swift keep the tradition of the monocultural pop star alive.

But as Swift’s music saturated airwaves, and her willingness to tease behind-the-scenes details of her life in her songs moved beyond ex-boyfriends like Harry Styles (“Style”) into swatting at other pop stars like Katy Perry (“Bad Blood”) the public began to sour on Swift’s strategic use of her personal life in her music. (To Swift’s credit as a performer, no other pop star could sing the lyrics “Band-Aids don’t fix bullet holes” about a dispute over a backup dancer with a straight face.)

Juxtaposed with Swift’s self-celebrating “girl squad” feminism, her opportunism — and seeming hypocrisy — started to rankle. By 2015, even racist sympathizer and critic Camille Paglia came out of the woodwork to anoint Swift a “Nazi barbie,” calling out her tendency to treat friends as props. And all these contradictions of Swift’s persona would come to a head when Swift’s seemingly buried feud with Kanye came roaring back the following year.

It makes sense that her clash with Kanye and Kim Kardashian West became the first time she experienced a real backlash. Unlike the drama around her dating life or with Perry, it was the first time Swift was up against equally savvy adversaries — celebrities who, like her, were professionals at merging their public and private lives.

The fight was a meta moment by design, inspired by West’s song “Famous,” where he raps: “I made that bitch famous.” In retrospect, it seems clear that West, as much a publicity-seeking pop diva as Swift, was trying to get the last word after going on an apology tour about the interruption heard round the world. Swift claimed to be annoyed over what she saw as the song’s credit-taking message, and she tried to make it part of her own narrative. “I want to say to all the young women out there,” she intoned in her speech accepting a Grammy for Album of the Year in February 2016, “there are going to be people along the way who will try to undercut your success or take credit for your accomplishments or your fame.”

In another era, Swift’s storyline might have won the day. Her publicist denied that she had approved the line in the song, despite Kanye’s claim that he had checked with her before releasing it. But celebrity narratives, to some degree, were no longer being decided just by white-dominated mainstream media. Black publications were the first to tease out the racial undertones of Swift’s lie in the ensuing “he said, she said,” specifically as a white woman playing on the ingrained sympathy and benefit of the doubt that white women are given in US culture.

Still, it wasn’t until Kim’s Snapchat leak that July — where Swift could be heard approving the song — that the Swift-as-victim narrative became a framework for understanding her entire career. Contemporary white pop stars like Grande and Miley Cyrus had faced musical appropriation backlashes, but this time it was Swift’s entire persona — not just her music — that were under scrutiny.

Swift’s memeable response to the leak — “I would very much like to be excluded from this narrative” — was followed by her own disappearance from the media landscape. By the time the 2016 election happened — amid the chatter about white women’s complicity in electing Trump — Swift’s refusal to take a political stand solidly cast her as a cultural villain, and her symbolism as an icon of toxic white womanhood was sealed.

If the clamor of social media (especially Twitter) was central to the Swift backlash, it was also central to her eventual resurgence. Over the past decade, social media (especially Instagram) has tipped the scales in celebrity coverage and helped celebrities tell their stories on their own terms, almost without intermediaries. Swift knew how to use that to her advantage and decided to play the long game.

By refusing interviews for 18 months, wiping her social media clean, and focusing on cultivating her Tumblr fanbase, Swift removed herself from the cultural conversation for a beat. This kind of brand management helped her keep an ear to the ground while in a self-imposed exile. But it’s as if the culture couldn’t stop conjuring her; rumors about her absence spread, including that she had traveled around inside a suitcase.

In August 2017, she wiped her social media clean and reappeared with a snake video — reclaiming the serpent emojis — in what was ultimately the announcement for her Reputation album, and which remains one of the most iconic social media rollouts ever. “Look What You Made Me Do,” the lead single, was endlessly memed — Swift couldn’t come to the phone, a perfect metaphor for her cultural disappearance and, perhaps, a kind of ghostly remake of the Kanye call. The album succeeded because it seemed as though Swift was finally open to owning her melodrama and messiness. She subsequently broke records with the tour and album sales.

Still, her political silence was affecting her image and music. By 2018, insipid corporate wokeness had become the order of the day, and Swift Inc. again pivoted musically and culturally. Swift came out for the Democratic candidates in the 2018 midterms, framing her support in terms of LGBTQ rights and racial justice. And this year, the second single from her latest album, Lover — “You Need to Calm Down” — was a perfect encapsulation of her politics of messiness, conflating anti-gay prejudice with Twitter drama. (And somehow turning the video into a celebration of pop queens supporting each other). This fall, she has made sure to include über-stan–turned–pop star (and video coproducer) Todrick Hall at her awards show moments, attempting to expand the range of racial and sexual identities included in what used to be her mostly straight white “girl squad” feminism.

For all of Swift’s success at updating her persona, she’s never quite regained her massive radio dominance — but no pop star can depend on the success of singles for over a decade. In fact, Swift is one of the most interesting figures of the decade because her stardom is caught between the old-school era of album buying and our current streaming moment.

And, inevitably, Swift has turned her own industry issues around streaming and artistic ownership into a wider commentary on artists’ rights — which happens to work as a canny form of further brand management. She framed herself as an ethical businesswoman when she called out Apple for not paying artists, and she battled with Spotify over streaming royalties but without really pushing for wider systemic industry change.

Earlier this year, Swift started a new artist-versus-industry fight about her music masters being bought out from under her by nemesis Scooter Braun. It’s a complicated story, one that Swift has framed as being about “toxic male privilege,” and the fact that Braun mocked her during the Kanye era — once again blurring, in her trademark mode, the personal with the public and the systemic with the individual.

Instead of being seen as opportunistic, Swift seems to have succeeded in framing her campaign as a fight for unsigned and less powerful artists’ rights, which has resonated at a moment where content creators are all pitted against the 1% of the tech and corporate worlds. This time, even Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez — a squad member any star would envy — backed her up.

Swift’s response to being anointed Artist of the Decade by the AMAs and Billboard provides interesting insight into how she sees herself now and where she thinks the next decade is going. She chose Carole King, one of the preeminent symbols of pop music authenticity, to present her AMA, squarely placing herself in a genealogy of great women singer-songwriters. She also enlisted shiny next-gen pop stars Camila Cabello and Halsey to join her during her performance of old hits.

In her Billboard speech, Swift name-checked newer stars like Lizzo, Becky G, and Billie Eilish as the future of the industry. Tellingly, they are women who, so far, have not played into the tabloidy pop dramas that dominated the 2010s. If this decade has shown us anything, it’s that blurring public and private through music can reap big rewards, but it also opens up stars — especially the women of pop — to more intense scrutiny and a higher degree of personal accountability.

In a Billboard interview looking back on the decade, Swift spoke about her relationship to fame and learning to hold things back. “I didn’t quite know what exactly to ... share and what to protect. I think a lot of people go through that, especially in the last decade,” she said. “There was this phase where social media felt fun and casual and quirky and safe. And then it got to the point where everyone has to evaluate their relationship with social media. So I decided that the best thing I have to offer people is my music.”

Like Lana Del Rey denying she ever had a persona, or Lady Gaga stripping down with Joanne, there seems to come a point when white pop divas need to declare themselves authentic and all about the music — as if their ongoing narratives aren’t part of the show. But the way Swift used her image and the never-ending soap opera that swirled around her to make space for her music in an increasingly saturated attention economy was itself a kind of art. ●

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

LGBT asks: 2, 24, 25, 30 (Also, I like this new theme, I can read it much more easily!)

Ah, thank you! My unfortunate, TEMPORARY new username aside, I’m glad it’s much more legible, since it was really bothering me as well.

2. How did you discover your sexuality, tell your story?

It’s odd because it really IS one of those things that always been lurking in the background. Like, I very distinctly remember, when I was about 7, telling my highly conservative babysitter while we were driving someplace, “I don’t like boys. I wish I didn’t have to marry one. I wish I could marry a girl instead.” And her daughter mentioned something like “Sometimes people do” and, in hindsight, I remember a bit of a hush around it. Now, I kind of wonder how she did know, what she’d been taught about it. Because I KNOW that household was not a gay friendly environment. (I mean, they banned Harry Potter for endorsing witchcraft. And Wizards of Waverly Place.)

When I was in Middle School, the environment changed. People KNEW that you could be gay, but it was an insult. I used it as an insult and I had it used as an insult against me. I’m not PROUD of that, it’s something I feel more than a little sense of shame over, but it really was the culture of growing up in a small, conservative town in the Midwest where there’s such a HUGE pressure to conform. During that time, I really wasn’t sure where I stood, because on one hand, I wanted to fit in (at least with THAT, with everything else, I chose to stand out as much as I could because, well, why not? They’d hate me anyway.) I do remember some girls pestering me about “What are you?” and saying “I’m heterosexual” just to get them off my back (and because I got the delicious joy of watching them try to spell it.) To be honest, even when I said that, I wasn’t SURE, because it didn’t feel 100% right, but, well, it was a RESPONSE, and that’s what they needed.

After 7th grade, I had to move out of state, because the bullying had just gotten that intense (technically speaking, the move wasn’t JUST for that reason, but my family had already decided that they would scrounge up the money to send me to private school if needed, which means there’s a parallel universe where I had to figure out I’m queer in CATHOLIC SCHOOL). And I was homeschooled for years afterwards. I was just. Too traumatized to deal with other kids, after that. To this day, I still feel a certain amount of anxiety around teenage girls. Since my social interaction really was limited to a certain extent, I don’t think I REALLY had a lot of the formative interactions that a lot of queer people have to come into their own.

It was funny because sometime around when I was 14-15, my mom RUSHED into my room and was like “RACHELIWASGOINGTHROUGHYOUREMAILSANDJUSTKNOWTHATI’LLLOVEYOUNOMATTERWHAT” and I was just like “Mom...I still haven’t decided yet..let me sleep...” Turns out, she had, WITH MY PERMISSION, been looking through my emails for something I needed, saw that I was on GLSEN’s mailing list after participating in one of their anti-bullying campaigns (because I’ve ALWAYS been a firm advocate against bullying after what I endured), and jumped to the wrong-right conclusion, depending on how you look at it. And that was my Dramatic Coming Out-Not Coming Out.

I experimented with labels; for AGES I ID’d as a member of the ace community and to this day I would still ride or die for them because they were SO helpful as far as stressing “You can change your mind as time goes on/There’s nothing wrong with you/etc.” To this day, tbh, I’m not sure whether I fall on the asexual spectrum. In no small part because I’ve never. Actually. Dated anyone. Or kissed. Or held hands with. I had a former best friend who was interested, but there were MULTIPLE issues with that one, so. No. Which does kind of put a damper on the old ego, but oh well.

Around when I was around 18-19, I think it FINALLY clicked in for me that, actually, I just had no idea what sexual attraction WAS but that I definitely felt SOMETHING on occasion, and that’s when it really clicked. Watching Takarazuka shows since then’s actually been hugely helpful as far as figuring things out (look, it’s stereotypical, especially for the western fandom, but it’s true. And it’s not just the more openly suggestive scenes, but just....seeing EVERY role being played by a woman really does help open your mind as far as the possibilities.) It was around this time that I actually started developing CRUSHES which...hurt. A lot. Like, I used to make fun of all my friends who were going completely bananas in Middle School and then it came back to bite me HARD. I’ve never gone for a straight girl, thankfully, but just people who, for a variety of reasons, are utterly unattainable and who USUALLY end up in ridiculously happy relationships shortly after I realize I have a crush.

24. How do you self-identify your gender, and what does that mean to you?

It’s odd because on one hand I don’t REALLY identify with womanhood PER SE. I like dresses, I like looking at them, particularly in a historical context, I like certain ASPECTS of femininity, but I’m not particularly interested in performing them. I’m not interested in putting on makeup or shaving every single section of my body. Growing up, I DREADED developing boobs, because I did ! Not ! Want ! Them ! (I can definitely appreciate them on someone else, but NOT ME.) The constant radfem THING they do where they plaster vaginas all over the place just kind of creeps me out, tbh. I’m not interested in IDing as a man, either, and most pronouns don’t really fit me any more (or even less) than she/her does. I’m just....ME, you know? I don’t want to be defined by one of my LEAST. FAVORITE. PARTS. OF. MY. BODY. If I was going to actually apply a label to it, I would probably say that I lean towards agender, but at the same time, I don’t really....feel like it’s NECESSARY, in a sense? So, I stick with “Woman/she/her” for simplicity’s sake.

25. Are you interested in having children? Why or why not?

I’m not interested in childbirth. That is a no-go. There is no way that I am EVER going through that process, given that I was born to my mom very late in life, I very nearly died in the process, and I grew up seeing the scars. I know that not ALL childbirth’s like that, but I won’t put myself through that. The entire thought is a little nauseating, tbh. If my partner was interested in it, then I could spring for it, because I’m actually pretty good when it comes to HANDLING kids, though I would be terrified to accidentally traumatize them. My family doesn’t necessarily have the best track record when it comes to abuse and I can’t imagine accidentally hurting a tiny person, or being involved with someone who would hurt the tiny person.

30. Why are you proud to be lgbt+?

It’s a part of me, and it’s one that was heavily stigmatized in the past. I’m always VERY conscious of how relatively lucky I am to exist in the cultural context I exist in, because even though I push back HARD against the idea that LGBT+ people COULDN”T be happy pre-20th century, it was still...difficult given that the terminology wasn’t generally there, at least in Europe, and there was such a heavy stigma against women who didn’t produce childbirth via a “legitimate” marriage. It’s been a difficult road in some ways and an easier one in others, but it’s really fantastic to live in an age where there IS a community and you know that there are others LIKE you.

1 note

·

View note

Text

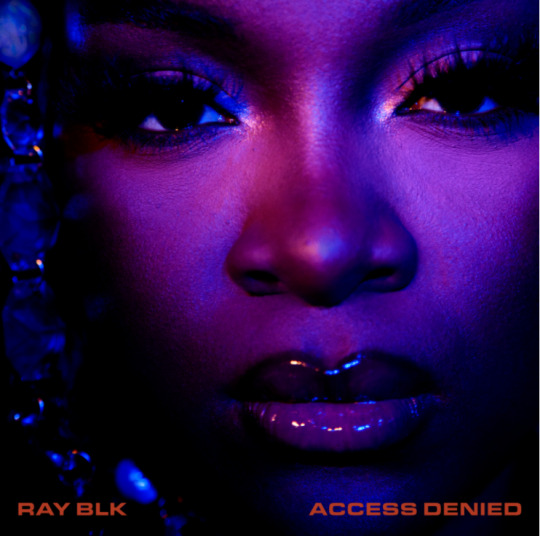

Ray BLK Album Review: Access Denied

(Island)

BY JORDAN MAINZER

For Ray BLK, pride and honesty go hand in hand. The British Nigerian singer-songwriter finally just released her debut studio album Access Denied, written and recorded during COVID-19 lockdown following years of self-releasing. Like on songs from her debut mixtape Havisham and mini-albums Durt and Empress, she details not just her insecurities and desires but how she’s worked to overcome and address them, respectively, all with self-assured and effortless sounding performance. “When I was younger, wanted to be the Black Madonna on stage,” she admits on opener “BLK MADONNA”, then clarifying, “But now that I’m older I can do anything I wanna.” Being herself isn’t just bucking the trends that show little representation for Black women in the music industry--it’s succeeding on top of that. “Weave laid, getting paid, slay in my lane,” Ray declares, proclaiming, “Every time I be on stage, they go ballistic.”

On Access Denied, Ray works with some of the biggest grime and R&B artists in the UK and provides a platform for up-and-comers. Growing up around grime in South London but decidedly not making grime rap, she’s always taken the most powerful aspects of the genre--hard-hitting beats, sociopolitical critiques, economic braggadocio--and molded them to her own style. She often sings like a rapper, occasionally in triplets, almost always over skittering beats or whipping snares. Early single “Lovesick” is bruising in theme, Ray taking control of her own agency after leaving a bad relationship, but chill in its flow. On the shuffling “Smoke”, she continues the sentiment of “BLK MADONNA”, able to do whatever she wants in music despite whatever others try to throw at her, statistical anomalies or role-based put-downs. The title track refers to her not allowing someone to ruin her newfound sense of self-care; that it starts with lo-fi chipmunked soul into synth bass before her trademark singing takes over is exemplary of Ray’s ability to conquer trends new and old.

Ray’s embrace of sexuality and womanhood comprise some of the best tracks on Access Denied, from her hilarious kiss-off of an unfaithful partner in “Lauren’s Skit” to “toxic sex” anthem “If I Die”. “You about to catch an essay,” she warns a ghosting partner on the latter, horny as hell. Best, to Ray, the dancefloor is both a place to express yourself and cathartically process things. On “Go-go Girl”, it’s Suburban Plaza giving Ray those strip club affirmations, “You earned that money, spend it...Don’t matter if they offended,” they chant before Ray’s powerful flow takes over. (“I’m the subject to their envy / Skin browner than this Henny / Ride him out like a Bentley,” she shouts.) On closer “Over You”, meanwhile, she declares to an ex, “I’m getting over you,” while on and perhaps because of the dancefloor, the song’s Diwali Riddim (specifically “Never Leave You (Uh Oooh, Uh Oooh)” by Lumidee) sample suggesting a crowd behind her, supporting her every step of the way.

What’s ultimately stunning about Access Denied is that Ray takes the pressure she’s under--some self-imposed, as on “25″, and some external, like on “Smoke”--and uses it to her advantage. “I try to redefine the hurt that made me hold my pride,” she sings on “Dark Skinned”, a perfect summation of the record. Over an upbeat snare bounce, she expresses pride in being a woman and pride in being Black and truly cements a strong sense of self.

youtube

#album review#ray blk#access denied#island#havisham#durt#empress#madonna#suburban plaza#lumidee#diwali riddim

1 note

·

View note

Text

I'm Not Like Other Girls, I'm Worse.

“Cool Girl. Men always use that, don’t they? As their defining compliment. She’s a cool girl. Cool Girl is hot. Cool Girl is game. Cool Girl is fun. Cool Girl never gets angry at her man. She only smiles in a chagrin, loving manner, and then presents her mouth for fucking. She likes what he likes, so, evidently he’s a vinyl hipster who loves fetish manga. If he likes “Girls Gone Wild,” she’s a mall babe who talks football and endures buffalo wings at Hooters...”

Delivered with an almost pathological ease, Rosamund Pike’s monologue in Gone Girl has provided fodder for discourse surrounding both surface and latent sexism since its 2014 theatrical release. The film is steeped in misogyny -- coloring the characters’ actions; defining their social interactions, relationships, and identities. It’s an insidious theme that presents itself most notably through “Amazing” Amy Dunne, our sharp-bobbed, sociopathic antiheroine whose disappearance acts as the catalyst for the plot.

“Nick loved a girl I was pretending to be.”

Amy is a self-professed “Cool Girl,” or rather, she was. She came to abhor the performance; resenting the act she had to put on for her husband. Although the diatribe quoted above lambasts this persona of male fantasy, Amy remains ensnared in the web of internalized misogyny. She loathes her adulterous husband, she loathes herself for becoming that which she detests, a woman scorned, but mostly, she loathes other women. Amy damns her own gender for carrying this charade of male devotion, believing herself to have reached a self-awareness apparently unfathomable to her female peers. Thus in eclipsing the “Cool Girl” moniker, Amy assumes a new persona -- one defined by the “I’m Not Like Other Girls” mentality.

“God, I’m so sick of other women! All they do is talk about drama, makeup, and boys. Why can’t I find any girls like me, who love chicken nuggets and getting dirty? Ugh, this is why I only hang out with guys -- they’re the only ones who understand me!” This is the manifesto of the girl who’s … different. She prides herself on never wearing makeup (and looks down on women who do). She prefers the company of men, because her own gender is just too dramatic. She doesn’t wear mini skirts, heels, or concern herself with stereotypically frivolous or overtly feminine contrivances… because that’s for Other Girls! This “Other Girl” is, you guessed it, a caricature -- a nameless/faceless entity to which people can ascribe their misogynistic narratives.

The plight of the modern woman exemplifies the ruinous effects of patriarchy -- a societal paradigm of male supremacy. In navigating this system, women are encouraged to despise the “Other Girl,” to avoid the “trappings” of femininity she emulates. We are meant to exist as monuments to the patriarch; condemning those who operate outside the realm of masculinity. This sexist ethos manifests as an internalisation of misogyny -- an insidious, socio-cultural phenomenon in which girls subconsciously project archaic ideals of sexism onto their own gender and even onto themselves. It’s inescapable, pervasive and, unfortunately, all women have fallen prey to its machinations. I, for one, would be remiss not to mention my own “I’m Not Like Other Girls” stage, as my 2014 Tumblr era was defined by a painfully exaggerated sense of self worth. I lauded myself for eschewing popular trends -- indulging only in the obscure and pretentious. I derided those who did not share my niche interests; judging girls who preferred The Last Song over Ruby Sparks; whose Taylor Swift was my Lorde. Looking back, I’ll readily admit that I was a pompous bitch. But can you blame me? Or the multitude of women who also underwent this embarrassing phase of “othering” ourselves? Since infancy, we’ve been inundated with rhetoric that dictates performances of femininity -- propaganda that was proliferated through television, classrooms, magazine covers, etcetera. Feminine pursuits were (and are) denigrated, and in renouncing girliness, our “reward” was male attention or approval.

Unfortunately, a scant scroll through TikTok exemplifies how internalized misogyny is prevalent even throughout the younger generations. A trend recently overtook the app in which girls introduced themselves as why other women supposedly hated them. The “reasons” varied, but almost always dealt with being conventionally attractive, having multiple guy friends, or simply being confident. This is merely a repackaging of the “I’m Not Like Other Girls” mentality, where, now, girls believe themselves to be envied and resented by their “bitter” female peers. Unlearning this manifestation of misogyny is no easy feat -- it’s an active, conscious process requiring awareness, introspection, and a willingness to go against the grain of societal norms. A continued reflection on how we uphold and preserve these misogynistic, curated conceptions of womanhood is thusly paramount for eradicating patriarchy from society. I, for one, am elated to proclaim that I’m exactly like other girls, and I truly would not have it any other way.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I told myself I wasn't gonna write another damn dissertation on my process relating to a character but I think Verah needs one. All of this, together, is why I'm seriously second guessing everything I do with her.

Warning for descriptions of transphobia / transmisogyny.

1. She's a nonbinary woman and it really hurts my heart to think about the kind of backlash she'd get if I wrote period-appropriate responses. Nick takes one look at her and goes "okay, got it, Woman with a list of bullet points attached that say Not Quite." Smartass describes her as "a self-made woman" in the sense of both owning her own business and his understanding being she literally made herself into one, which in her case is pretty much what happened. He thinks she's a fucking badass for undergoing a year-long process to hybridize into two Toon Kindoms, Mechanical and Plant, being in total control of her presentation and using that control to create her own unique looks. Never trying to blend in with the human crowd also earns her points with him.

Because they don't really have another frame of reference most people in Ground Zero veiw her as a drag queen who has no personal identification with womanhood outside performing femininity, or think of her change as a clever allegory or comparison to being transgender and she's like: "No, I'm actually trans. I went from being named genderless by my creators to coming into my own as a feminine entity." She's okay with others referring to her with masculine or neutral terms because misgendering pretty much just Doesn't Happen where she comes from, at least to start with she thinks they have the same nuanced understanding of her as Nick.

She also thinks it's weird that so many humans present either really masculine or really feminine but who is she to question someone's relationship with their gender without their asking for a conversation on it? You don't just walk up to someone and breech that subject uninvited. People she encounters don't do that because they're intimidated by the idea of a bad reaction.

Nick's standing there fuming, extremely frustrated, because... What do you do to in that situation. He wants to snark at them in her defense but that could very easily backfire towards her or other vulnerable people. He doesn't fit Ground Zero's strict idea of a traditional man even if it's not immediately obvious to the casual observer, and pointing that out as a gotcha, asking if they're going to take back their treatment of him as a "valid" man could just as easily get someone to admit that okay, maybe this whole thing is a little more complicated than I thought or make him a target, too.

Eddie was initially thrown by her but Nick seems like he knows exactly what to do, she responds positively to the way he acts so he follows that lead. It dawns on him that they're sitting on a powder keg but he doesn't really have an easy answer, either. Toons get some more leeway to play with gender but it's another thing that's not really taken seriously.

Yes, she's meant to be big and grand and larger than life. She's meant to have a fluid identity. She embodies the joyful and creative aspects of being transgender, the euphoric, the unapologetic. And I want so badly to keep that spirit alive, but I don't know how.

What does the human trans population think of their portrayal in either Toons that were created to be trans or be like them, or ones taking trans / gender nonconforming roles in cartoons? Who's considered the authority on the gender of a Toon, them, their creator, the studio they're signed with? What about alternate gendered versions of the same character? In what capacity does drag / ball culture exist? What about the leather / biker scene? What about the military, the navy?

2. She was too powerful. Volunary shapeshifting with next to no limits, heightened perception, regeneration and the ability to heal others with contact and brewed potions, really strong. I knocked her down a few pegs by changing it so the last climate she was hanging out in was a cold, wet place, she needs time to get used to the desert before she can really excersize her powers or she'll end up draining herself. She's having trouble integrating plant data from the landscape because their genetics are all kinds of fucked up and she can't get what she already has to mesh with the new information. Does she remake herself again or take the power cut?

3. Making her appear naive by comparison to Nick and Eddie in too many things. This was 'cause the beginning and end of the setting she came from was "high fantasy near-utopia" and I didn't really think about the points in #5, she was consistently confused and hurt by encountering things like bigotry, poverty, militant anti-intellectualism, et cetra.

4. Because I didn't, and kinda still don't know how to show her reacting negatively I ended up projecting a lot of her traits and themes onto other characters.

5. I put a Lot of colonialist / imperialist ideas into her. And not just surface level stuff, I mean like baked in. "Worker drone repurposed into reseacher that Explores Untamed Lands, finding samples of Resources and Bending Them to her will through Science Magic, using that Knowledge to Create Medicine and wondrous Products." More on that in the second part of this post.

Am I thinking way too hard about all this, considering the tone of the source material? Probably. Should I just stop with all of this? Maybe. I don't know.

#verah the hybrid automaton#transphobia mention#transmisogny mention#nonhuman trans character#misgendering#the fic#long post

0 notes

Text

The Sublime’s Effects in Gothic Fiction

With ghosts, spacious castles, and fainting heroes, Gothic fiction conveys both thrill and intrigue. Gothic literature is a combination of horror fiction and Romantic thought; Romantic thought encompasses awe toward nature. Essentially, Romanticism is a reaction against the Enlightenment, a time that revolutionized scientific thought, and emphasizes emotional response and intuition over clinical knowledge. Romantic literature elicits personal pleasure from natural beauty, and Gothic fiction takes this aesthetic reaction and subverts it by creating delight and confusion from terror. This use of terror is called the sublime, which is an important tool in these narratives. Examples of Gothic literature range from dark romances to supernatural mysteries.

In Gothic novels, no matter the setting or villain, the sublime exists as a different experience than appreciating natural beauty. In fact, this concept deals with how authors capture their characters’ trauma and fear. It is important to look at the sublime in the lens of both the characters’ experiences and the real world contexts that influence them.

Beyond identifying the sublime, a crucial part of looking at this technique is seeing how the fears present in Gothic literature factor into real life concerns, such as the enforced roles and restrictions faced by women. The use of terror illuminates how the marginalized, once given a voice, cope with their harrowing predicaments, and reading about these struggles helps foster comprehension and empathy.

Defining the Sublime

What separates experiencing the sublime from experiencing beauty is the disruption of harmony. As stated above, it shows elements of Romantic reactions to human experience while utilizing fear as well. According to Edmund Burke, the imagination experiences both thrill and fear through what is “dark, uncertain, and confused.” 1 In setting the sublime apart from beauty, the sublime creates more than a positive, appreciative response to an aesthetic, such as a beautiful painting or sunlit meadow. The sublime stems from potent awe and terror that stresses someone’s limits, surpassing all other responses and overloading the recipient in both their revulsion and fascination.

In regards to the Romantic view of the environment, the sublime can occur when natural grandeur overwhelms an individual to the point of causing fright or a feeling of helpless insignificance. Overall, approaching the sublime occurs when a sight or experience is “awesome” or ” awful” in the old meaning of both words: characterized by or inspiring awe, and awe is an emotion containing fear, wonder, and reverence. The sublime questions the stark dichotomy between pleasure and pain because a fear-invoking scene can also cause wonder, an odd sort of delight. In a contemporary sense, it could be viewed as watching a train wreck: horrifying, but captivating to the viewer.

Because of its potency and Burke’s gendered views, he viewed the Romantic or Gothic sublime as a more masculine and powerful experience than beauty, which he perceived as feminine, and therefore more fragile and superficial. However, Mary Wollstonecraft, an English writer and avid women’s rights advocate, argued against this perspective and its depiction of women as inherently weak and passive. For Wollstonecraft, the sublime dealt with the self and its subjective views of society and spectacular natural scenery.

Interestingly enough, Ann Radcliffe, the English writer who pioneered the Gothic novel (as well as the “Female Gothic” novel, Gothic literature for women, by women), maintained that horror and terror exist as separate entities, and that terror, not horror, creates the sublime because, while horror is definite, terror provokes ambiguous emotions, which in turn “expands the soul and awakens the faculties to a high degree of life.” 2Horror involves witnessing the monster, of seeing blood or a corpse, while terror burrows into an individual’s unclear psyche and entails multiple, conflicting emotions stirring at once.

Gender and Evoking the Sublime

Going off of Mary Wollstonecraft’s view of the sublime as a part of her relationship to society (and how 19th century Western culture treated women’s intelligence and education), the sublime, through overwrought sensory details, can reveal what scares the character based on real struggles. For women in Victorian England (1837-1901), the sublime is triggered through a fear of confinement and suppression based on societal expectations; an example of this fear appears in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre 3.

In the beginning, Jane experiences terror when her aunt locks her inside the red-room, the former chambers of her dead uncle. As her imprisonment lingers, the experience takes its toll on Jane, and she soon believes her uncle’s ghost, a patriarchal symbol, will rise and attack her. She states, “My heart beat thick, my head grew hot; a sound filled my ears, which I deemed the rushing of wings; something seemed near me; I was oppressed, suffocated; endurance broke down; I rushed to the door and shook the lock in desperate effort” (11).

Jane Eyre becomes enraptured in an experience that affects her on both a physical and emotional level, an experience that strains her, that challenges her and extends past the capacity of her imagination. The sublime creates hysteria, and the concept of “hysteria” derives from the archaic belief that cis women act in excess or have uncontrollable, irrational bouts of emotions when their uterus does not function properly. Considering the Victorian woman’s experience, as well as earlier ones (though published in the Victorian era, Bronte set the novel in the Georgian era) the red-room may be red for a variety of symbolic reasons: menstruation (Jane is ten at the novel’s beginning and will soon enter puberty); passion; torment; blood.

Furthermore, Jane’s imprisonment in the red-room stems from punishment for confronting her male cousin after he hits her and insults her because she is dependent on his family and because the books she reads are not her own. She suffers for rebelling, for educating herself and living in an environment where she does not possess her own independence, so the surreality of her break with reality emphasizes the terror of her experience as a girl approaching womanhood.

In Jane Eyre, this issue also manifests in the character of Bertha Mason, the wife of Jane’s love interest, who spends several years locked in an attic because of her mental instability. Because of society’s treatment of mental illness, especially in regards to Bertha’s gender and racial identity, Bertha becomes as trapped as Jane was at the start of the novel, and her ordeal culminates in a result that is both terrifying to witness but dazzling and gripping in its own terrible way: fire.

Frankenstein: Awe-Inspiring Feats and Standards of Beauty

5 The Sublime in Gothic fiction

Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein 4 deals with many complex themes while invoking the sublime. She considered the novel her own monster, with herself as the creator. While many of her male contemporaries mainly worked with poetry and operated in exclusive chats, Mary Shelley wrote a complex novel at a young age.

The narrative deals with the impact of nature. In fact, Frankensteinchallenges the aspect of nature itself as the titular character, Victor Frankenstein, researches both modern science and alchemy to defeat death. In terms of the environment, the Monster comes to life due to a violent storm. Before that, Victor speaks of feeling jubilation from a startling and intriguing natural event.

When I was about fifteen years old we had retired to our house near Belrive, when we witnessed a most violent and terrible thunderstorm. It advanced from behind the mountains of Jura, and the thunder burst at once with frightful loudness from various quarters of the heavens. I remained, while the storm lasted, watching its progress with curiosity and delight. As I stood at the door, on a sudden I beheld a stream of fire issue from an old and beautiful oak which stood about twenty yards from our house; and so soon as the dazzling light vanished, the oak had disappeared, and nothing remained but a blasted stump. When we visited it the next morning, we found the tree shattered in a singular manner. It was not splintered by the shock, but entirely reduced to thin ribbons of wood. I never beheld anything so utterly destroyed.

This scene not only shows the sublime, but foreshadows Victor’s ruination. Victor’s own accomplishment is an awe-inspiring feat; it is an action that incites inspiration and terror as the Monster becomes a strikingly intelligent living being, but suffers marginalization because he is the embodiment of the sublime and not beauty. The Monster is painful to look at, and therefore mistreated and accosted.

Victor becomes the modern Prometheus, the Titan who brought fire to humanity at a terrible cost. By mirroring the Titan’s fate, Victor performs a grand feat, fueled by knowledge and breaking boundaries, and suffers not only for his transgression, but for neglecting his grotesque creation, his child, for a superficial reason.

Though he initially seeks for his creation to be beautiful, the actual result elicits terror. Victor states, “No mortal could support the horror of that countenance.” When the living creature moves, it then “became a thing such as even Dante could not have conceive.” The situation, as miraculous and groundbreaking as it is, becomes Victor’s own personal hell. As his life unravels, the reader becomes the recipient of a sublime experience: as horrific as the downfall is to witness, the narrative propels the reader forward to the bleak and devastating conclusion.

One could also determine that this Gothic tragedy also displays elements of dissecting the fears of Victorian cis women, though the Monster’s creation and how people treat him have also become representations of brilliant but morally-questioned modern innovations (genetically modified food; cloning animals) and contemporary marginalization (issues of race, sexuality, transgender identity, disability, etc.).

Concerning the fears of Victorian cis women, Mary Shelley’s mother, the aforementioned Mary Wollstonecraft, died from a post-birth infection, and Shelley herself suffered from miscarriages and the deaths of infant children and dreamed of one of her babies returning to life. It is entirely possible that Frankenstein contains Shelley’s thoughts on both the wonder and trauma of childbirth, since Mary’s own birth caused her mother’s infection and death.

In the preface for Frankenstein, Mary Shelley writes, “And now, once again, I bid my hideous progeny go forth and prosper. I have an affection for it, for it was the offspring of happy days, when death and grief were but words, which found no true echo in my heart.” The Monster and his creation are not only representations of the sublime, but the novel itself, for it exists as both an entity of woe and happiness concerning the author’s past, present, and future misfortunes.

As an important part of Gothic works, the sublime helps readers uncover aspects of humanity. The commingling delight and terror deal with personal emotions and experiences for both the characters and the works’ authors, as well as the audience. It is essential to not only be able to define and find the sublime in Gothic literature, but to also determine the causes of fear in hopes that the reader can empathize with the complex, overwhelming struggles presented in various works. Though this is a 19th century concept, the pivotal issues presented in Gothic works such as Jane Eyreand Frankenstein reverberate in modern culture.

Works Cited

Burke, Edmund, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, Part I, Section VII. ↩

Bruhm, Steven. Gothic Bodies: The Politics of Pain in Romantic Fiction.Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994. ↩

Bronte, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. New York: Harper Collins, 2010. Print. ↩

Shelley, Mary W. Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. Project Gutenberg, 2 Mar. 2005. Web. 5 Dec. 2015. ↩

0 notes