#and that WHOLE process is inextricably connected to capitalism

Text

#it's important to be able to see this#that like. capitalism is not a person#it cannot ''teach'' because it isn't physical#but it's a system. it's society. it's education#like your parents were brought up to believe things and they taught them to you#and that WHOLE process is inextricably connected to capitalism

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

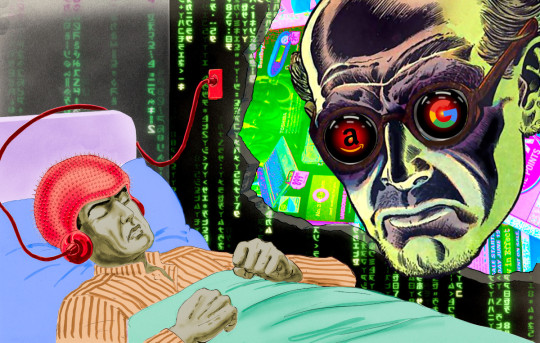

Big Tech’s “attention rents”

Tomorrow (Nov 4), I'm keynoting the Hackaday Supercon in Pasadena, CA.

The thing is, any feed or search result is "algorithmic." "Just show me the things posted by people I follow in reverse-chronological order" is an algorithm. "Just show me products that have this SKU" is an algorithm. "Alphabetical sort" is an algorithm. "Random sort" is an algorithm.

Any process that involves more information than you can take in at a glance or digest in a moment needs some kind of sense-making. It needs to be put in some kind of order. There's always gonna be an algorithm.

But that's not what we mean by "the algorithm" (TM). When we talk about "the algorithm," we mean a system for ordering information that uses complex criteria that are not precisely known to us, and than can't be easily divined through an examination of the ordering.

There's an idea that a "good" algorithm is one that does not seek to deceive or harm us. When you search for a specific part number, you want exact matches for that search at the top of the results. It's fine if those results include third-party parts that are compatible with the part you're searching for, so long as they're clearly labeled. There's room for argument about how to order those results – do highly rated third-party parts go above the OEM part? How should the algorithm trade off price and quality?

It's hard to come up with an objective standard to resolve these fine-grained differences, but search technologists have tried. Think of Google: they have a patent on "long clicks." A "long click" is when you search for something and then don't search for it again for quite some time, the implication being that you've found what you were looking for. Google Search ads operate a "pay per click" model, and there's an argument that this aligns Google's ad division's interests with search quality: if the ad division only gets paid when you click a link, they will militate for placing ads that users want to click on.

Platforms are inextricably bound up in this algorithmic information sorting business. Platforms have emerged as the endemic form of internet-based business, which is ironic, because a platform is just an intermediary – a company that connects different groups to each other. The internet's great promise was "disintermediation" – getting rid of intermediaries. We did that, and then we got a whole bunch of new intermediaries.

Usually, those groups can be sorted into two buckets: "business customers" (drivers, merchants, advertisers, publishers, creative workers, etc) and "end users" (riders, shoppers, consumers, audiences, etc). Platforms also sometimes connect end users to each other: think of dating sites, or interest-based forums on Reddit. Either way, a platform's job is to make these connections, and that means platforms are always in the algorithm business.

Whether that's matching a driver and a rider, or an advertiser and a consumer, or a reader and a mix of content from social feeds they're subscribed to and other sources of information on the service, the platform has to make a call as to what you're going to see or do.

These choices are enormously consequential. In the theory of Surveillance Capitalism, these choices take on an almost supernatural quality, where "Big Data" can be used to guess your response to all the different ways of pitching an idea or product to you, in order to select the optimal pitch that bypasses your critical faculties and actually controls your actions, robbing you of "the right to a future tense."

I don't think much of this hypothesis. Every claim to mind control – from Rasputin to MK Ultra to neurolinguistic programming to pick-up artists – has turned out to be bullshit. Besides, you don't need to believe in mind control to explain the ways that algorithms shape our beliefs and actions. When a single company dominates the information landscape – say, when Google controls 90% of your searches – then Google's sorting can deprive you of access to information without you knowing it.

If every "locksmith" listed on Google Maps is a fake referral business, you might conclude that there are no more reputable storefront locksmiths in existence. What's more, this belief is a form of self-fulfilling prophecy: if Google Maps never shows anyone a real locksmith, all the real locksmiths will eventually go bust.

If you never see a social media update from a news source you follow, you might forget that the source exists, or assume they've gone under. If you see a flood of viral videos of smash-and-grab shoplifter gangs and never see a news story about wage theft, you might assume that the former is common and the latter is rare (in reality, shoplifting hasn't risen appreciably, while wage-theft is off the charts).

In the theory of Surveillance Capitalism, the algorithm was invented to make advertisers richer, and then went on to pervert the news (by incentivizing "clickbait") and finally destroyed our politics when its persuasive powers were hijacked by Steve Bannon, Cambridge Analytica, and QAnon grifters to turn millions of vulnerable people into swivel-eyed loons, racists and conspiratorialists.

As I've written, I think this theory gives the ad-tech sector both too much and too little credit, and draws an artificial line between ad-tech and other platform businesses that obscures the connection between all forms of platform decay, from Uber to HBO to Google Search to Twitter to Apple and beyond:

https://pluralistic.net/HowToDestroySurveillanceCapitalism

As a counter to Surveillance Capitalism, I've proposed a theory of platform decay called enshittification, which identifies how the market power of monopoly platforms, combined with the flexibility of digital tools, combined with regulatory capture, allows platforms to abuse both business-customers and end-users, by depriving them of alternatives, then "twiddling" the knobs that determine the rules of the platform without fearing sanction under privacy, labor or consumer protection law, and finally, blocking digital self-help measures like ad-blockers, alternative clients, scrapers, reverse engineering, jailbreaking, and other tech guerrilla warfare tactics:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/#hey-guys

One important distinction between Surveillance Capitalism and enshittification is that enshittification posits that the platform is bad for everyone. Surveillance Capitalism starts from the assumption that surveillance advertising is devastatingly effective (which explains how your racist Facebook uncles got turned into Jan 6 QAnons), and concludes that advertisers must be well-served by the surveillance system.

But advertisers – and other business customers – are very poorly served by platforms. Procter and Gamble reduced its annual surveillance advertising budget from $100m//year to $0/year and saw a 0% reduction in sales. The supposed laser-focused targeting and superhuman message refinement just don't work very well – first, because the tech companies are run by bullshitters whose marketing copy is nonsense, and second because these companies are monopolies who can abuse their customers without losing money.

The point of enshittification is to lock end-users to the platform, then use those locked-in users as bait for business customers, who will also become locked to the platform. Once everyone is holding everyone else hostage, the platform uses the flexibility of digital services to play a variety of algorithmic games to shift value from everyone to the business's shareholders. This flexibility is supercharged by the failure of regulators to enforce privacy, labor and consumer protection standards against the companies, and by these companies' ability to insist that regulators punish end-users, competitors, tinkerers and other third parties to mod, reverse, hack or jailbreak their products and services to block their abuse.

Enshittification needs The Algorithm. When Uber wants to steal from its drivers, it can just do an old-fashioned wage theft, but eventually it will face the music for that kind of scam:

https://apnews.com/article/uber-lyft-new-york-city-wage-theft-9ae3f629cf32d3f2fb6c39b8ffcc6cc6

The best way to steal from drivers is with algorithmic wage discrimination. That's when Uber offers occassional, selective drivers higher rates than it gives to drivers who are fully locked to its platform and take every ride the app offers. The less selective a driver becomes, the lower the premium the app offers goes, but if a driver starts refusing rides, the wage offer climbs again. This isn't the mind-control of Surveillance Capitalism, it's just fraud, shaving fractional pennies off your paycheck in the hopes that you won't notice. The goal is to get drivers to abandon the other side-hustles that allow them to be so choosy about when they drive Uber, and then, once the driver is fully committed, to crank the wage-dial down to the lowest possible setting:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/12/algorithmic-wage-discrimination/#fishers-of-men

This is the same game that Facebook played with publishers on the way to its enshittification: when Facebook began aggressively courting publishers, any short snippet republished from the publisher's website to a Facebook feed was likely to be recommended to large numbers of readers. Facebook offered publishers a vast traffic funnel that drove millions of readers to their sites.

But as publishers became more dependent on that traffic, Facebook's algorithm started downranking short excerpts in favor of medium-length ones, building slowly to fulltext Facebook posts that were fully substitutive for the publisher's own web offerings. Like Uber's wage algorithm, Facebook's recommendation engine played its targets like fish on a line.

When publishers responded to declining reach for short excerpts by stepping back from Facebook, Facebook goosed the traffic for their existing posts, sending fresh floods of readers to the publisher's site. When the publisher returned to Facebook, the algorithm once again set to coaxing the publishers into posting ever-larger fractions of their work to Facebook, until, finally, the publisher was totally locked into Facebook. Facebook then started charging publishers for "boosting" – not just to be included in algorithmic recommendations, but to reach their own subscribers.

Enshittification is modern, high-tech enabled, monopolistic form of rent seeking. Rent-seeking is a subtle and important idea from economics, one that is increasingly relevant to our modern economy. For economists, a "rent" is income you get from owning a "factor of production" – something that someone else needs to make or do something.

Rents are not "profits." Profit is income you get from making or doing something. Rent is income you get from owning something needed to make a profit. People who earn their income from rents are called rentiers. If you make your income from profits, you're a "capitalist."

Capitalists and rentiers are in irreconcilable combat with each other. A capitalist wants access to their factors of production at the lowest possible price, whereas rentiers want those prices to be as high as possible. A phone manufacturer wants to be able to make phones as cheaply as possible, while a patent-troll wants to own a patent that the phone manufacturer needs to license in order to make phones. The manufacturer is a capitalism, the troll is a rentier.

The troll might even decide that the best strategy for maximizing their rents is to exclusively license their patents to a single manufacturer and try to eliminate all other phones from the market. This will allow the chosen manufacturer to charge more and also allow the troll to get higher rents. Every capitalist except the chosen manufacturer loses. So do people who want to buy phones. Eventually, even the chosen manufacturer will lose, because the rentier can demand an ever-greater share of their profits in rent.

Digital technology enables all kinds of rent extraction. The more digitized an industry is, the more rent-seeking it becomes. Think of cars, which harvest your data, block third-party repair and parts, and force you to buy everything from acceleration to seat-heaters as a monthly subscription:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/07/24/rent-to-pwn/#kitt-is-a-demon

The cloud is especially prone to rent-seeking, as Yanis Varoufakis writes in his new book, Technofeudalism, where he explains how "cloudalists" have found ways to lock all kinds of productive enterprise into using cloud-based resources from which ever-increasing rents can be extracted:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/09/28/cloudalists/#cloud-capital

The endless malleability of digitization makes for endless variety in rent-seeking, and cataloging all the different forms of digital rent-extraction is a major project in this Age of Enshittification. "Algorithmic Attention Rents: A theory of digital platform market power," a new UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose paper by Tim O'Reilly, Ilan Strauss and Mariana Mazzucato, pins down one of these forms:

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/publications/2023/nov/algorithmic-attention-rents-theory-digital-platform-market-power

The "attention rents" referenced in the paper's title are bait-and-switch scams in which a platform deliberately enshittifies its recommendations, search results or feeds to show you things that are not the thing you asked to see, expect to see, or want to see. They don't do this out of sadism! The point is to extract rent – from you (wasted time, suboptimal outcomes) and from business customers (extracting rents for "boosting," jumbling good results in among scammy or low-quality results).

The authors cite several examples of these attention rents. Much of the paper is given over to Amazon's so-called "advertising" product, a $31b/year program that charges sellers to have their products placed above the items that Amazon's own search engine predicts you will want to buy:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/28/enshittification/#relentless-payola

This is a form of gladiatorial combat that pits sellers against each other, forcing them to surrender an ever-larger share of their profits in rent to Amazon for pride of place. Amazon uses a variety of deceptive labels ("Highly Rated – Sponsored") to get you to click on these products, but most of all, they rely two factors. First, Amazon has a long history of surfacing good results in response to queries, which makes buying whatever's at the top of a list a good bet. Second, there's just so many possible results that it takes a lot of work to sift through the probably-adequate stuff at the top of the listings and get to the actually-good stuff down below.

Amazon spent decades subsidizing its sellers' goods – an illegal practice known as "predatory pricing" that enforcers have increasingly turned a blind eye to since the Reagan administration. This has left it with few competitors:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/19/fake-it-till-you-make-it/#millennial-lifestyle-subsidy

The lack of competing retail outlets lets Amazon impose other rent-seeking conditions on its sellers. For example, Amazon has a "most favored nation" requirement that forces companies that raise their prices on Amazon to raise their prices everywhere else, which makes everything you buy more expensive, whether that's a Walmart, Target, a mom-and-pop store, or direct from the manufacturer:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/25/greedflation/#commissar-bezos

But everyone loses in this "two-sided market." Amazon used "junk ads" to juice its ad-revenue: these are ads that are objectively bad matches for your search, like showing you a Seattle Seahawks jersey in response to a search for LA Lakers merch:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-02/amazon-boosted-junk-ads-hid-messages-with-signal-ftc-says

The more of these junk ads Amazon showed, the more revenue it got from sellers – and the more the person selling a Lakers jersey had to pay to show up at the top of your search, and the more they had to charge you to cover those ad expenses, and the more they had to charge for it everywhere else, too.

The authors describe this process as a transformation between "attention rents" (misdirecting your attention) to "pecuniary rents" (making money). That's important: despite decades of rhetoric about the "attention economy," attention isn't money. As I wrote in my enshittification essay:

You can't use attention as a medium of exchange. You can't use it as a store of value. You can't use it as a unit of account. Attention is like cryptocurrency: a worthless token that is only valuable to the extent that you can trick or coerce someone into parting with "fiat" currency in exchange for it. You have to "monetize" it – that is, you have to exchange the fake money for real money.

The authors come up with some clever techniques for quantifying the ways that this scam harms users. For example, they count the number of places that an advertised product rises in search results, relative to where it would show up in an "organic" search. These quantifications are instructive, but they're also a kind of subtweet at the judiciary.

In 2018, SCOTUS's ruling in American Express v Ohio changed antitrust law for two-sided markets by insisting that so long as one side of a two-sided market was better off as the result of anticompetitive actions, there was no antitrust violation:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3346776

For platforms, that means that it's OK to screw over sellers, advertisers, performers and other business customers, so long as the end-users are better off: "Go ahead, cheat the Uber drivers, so long as you split the booty with Uber riders."

But in the absence of competition, regulation or self-help measures, platforms cheat everyone – that's the point of enshittification. The attention rents that Amazon's payola scheme extract from shoppers translate into higher prices, worse goods, and lower profits for platform sellers. In other words, Amazon's conduct is so sleazy that it even threads the infinitesimal needle that the Supremes created in American Express.

Here's another algorithmic pecuniary rent: Amazon figured out which of its major rivals used an automated price-matching algorithm, and then cataloged which products they had in common with those sellers. Then, under a program called Project Nessie, Amazon jacked up the prices of those products, knowing that as soon as they raised the prices on Amazon, the prices would go up everywhere else, so Amazon wouldn't lose customers to cheaper alternatives. That scam made Amazon at least a billion dollars:

https://gizmodo.com/ftc-alleges-amazon-used-price-gouging-algorithm-1850986303

This is a great example of how enshittification – rent-seeking on digital platforms – is different from analog rent-seeking. The speed and flexibility with which Amazon and its rivals altered their prices requires digitization. Digitization also let Amazon crank the price-gouging dial to zero whenever they worried that regulators were investigating the program.

So what do we do about it? After years of being made to look like fumblers and clowns by Big Tech, regulators and enforcers – and even lawmakers – have decided to get serious.

The neoliberal narrative of government helplessness and incompetence would have you believe that this will go nowhere. Governments aren't as powerful as giant corporations, and regulators aren't as smart as the supergeniuses of Big Tech. They don't stand a chance.

But that's a counsel of despair and a cheap trick. Weaker US governments have taken on stronger oligarchies and won – think of the defeat of JD Rockefeller and the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911. The people who pulled that off weren't wizards. They were just determined public servants, with political will behind them. There is a growing, forceful public will to end the rein of Big Tech, and there are some determined public servants surfing that will.

In this paper, the authors try to give those enforcers ammo to bring to court and to the public. For example, Amazon claims that its algorithm surfaces the products that make the public happy, without the need for competitive pressure to keep it sharp. But as the paper points out, the only successful new rival ecommerce platform – Tiktok – has found an audience for an entirely new category of goods: dupes, "lower-cost products that have the same or better features than higher cost branded products."

The authors also identify "dark patterns" that platforms use to trick users into consuming feeds that have a higher volume of things that the company profits from, and a lower volume of things that users want to see. For example, platforms routinely switch users from a "following" feed – consisting of things posted by people the user asked to hear from – with an algorithmic "For You" feed, filled with the things the company's shareholders wish the users had asked to see.

Calling this a "dark pattern" reveals just how hollow and self-aggrandizing that term is. "Dark pattern" usually means "fraud." If I ask to see posts from people I like, and you show me posts from people who'll pay you for my attention instead, that's not a sophisticated sleight of hand – it's just a scam. It's the social media equivalent of the eBay seller who sends you an iPhone box with a bunch of gravel inside it instead of an iPhone. Tech bros came up with "dark pattern" as a way of flattering themselves by draping themselves in the mantle of dopamine-hacking wizards, rather than unimaginative con-artists who use a computer to rip people off.

These For You algorithmic feeds aren't just a way to increase the load of sponsored posts in a feed – they're also part of the multi-sided ripoff of enshittified platforms. A For You feed allows platforms to trick publishers and performers into thinking that they are "good at the platform," which both convinces to optimize their production for that platform, and also turns them into Judas Goats who conspicuously brag about how great the platform is for people like them, which brings their peers in, too.

In Veena Dubal's essential paper on algorithmic wage discrimination, she describes how Uber drivers whom the algorithm has favored with (temporary) high per-ride rates brag on driver forums about their skill with the app, bringing in other drivers who blame their lower wages on their failure to "use the app right":

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4331080

As I wrote in my enshittification essay:

If you go down to the midway at your county fair, you'll spot some poor sucker walking around all day with a giant teddy bear that they won by throwing three balls in a peach basket.

The peach-basket is a rigged game. The carny can use a hidden switch to force the balls to bounce out of the basket. No one wins a giant teddy bear unless the carny wants them to win it. Why did the carny let the sucker win the giant teddy bear? So that he'd carry it around all day, convincing other suckers to put down five bucks for their chance to win one:

https://boingboing.net/2006/08/27/rigged-carny-game.html

The carny allocated a giant teddy bear to that poor sucker the way that platforms allocate surpluses to key performers – as a convincer in a "Big Store" con, a way to rope in other suckers who'll make content for the platform, anchoring themselves and their audiences to it.

Platform can't run the giant teddy-bear con unless there's a For You feed. Some platforms – like Tiktok – tempt users into a For You feed by making it as useful as possible, then salting it with doses of enshittification:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/emilybaker-white/2023/01/20/tiktoks-secret-heating-button-can-make-anyone-go-viral/

Other platforms use the (ugh) "dark pattern" of simply flipping your preference from a "following" feed to a "For You" feed. Either way, the platform can't let anyone keep the giant teddy-bear. Once you've tempted, say, sports bros into piling into the platform with the promise of millions of free eyeballs, you need to withdraw the algorithm's favor for their content so you can give it to, say, astrologers. Of course, the more locked-in the users are, the more shit you can pile into that feed without worrying about them going elsewhere, and the more giant teddy-bears you can give away to more business users so you can lock them in and start extracting rent.

For regulators, the possibility of a "good" algorithmic feed presents a serious challenge: when a feed is bad, how can a regulator tell if its low quality is due to the platform's incompetence at blocking spammers or guessing what users want, or whether it's because the platform is extracting rents?

The paper includes a suite of recommendations, including one that I really liked:

Regulators, working with cooperative industry players, would define reportable metrics based on those that are actually used by the platforms themselves to manage search, social media, e-commerce, and other algorithmic relevancy and recommendation engines.

In other words: find out how the companies themselves measure their performance. Find out what KPIs executives have to hit in order to earn their annual bonuses and use those to figure out what the company's performance is – ad load, ratio of organic clicks to ad clicks, average click-through on the first organic result, etc.

They also recommend some hard rules, like reserving a portion of the top of the screen for "organic" search results, and requiring exact matches to show up as the top result.

I've proposed something similar, applicable across multiple kinds of digital businesses: an end-to-end principle for online services. The end-to-end principle is as old as the internet, and it decrees that the role of an intermediary should be to deliver data from willing senders to willing receivers as quickly and reliably as possible. When we apply this principle to your ISP, we call it Net Neutrality. For services, E2E would mean that if I subscribed to your feed, the service would have a duty to deliver it to me. If I hoisted your email out of my spam folder, none of your future emails should land there. If I search for your product and there's an exact match, that should be the top result:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/04/platforms-decay-lets-put-users-first

One interesting wrinkle to framing platform degradation as a failure to connect willing senders and receivers is that it places a whole host of conduct within the regulatory remit of the FTC. Section 5 of the FTC Act contains a broad prohibition against "unfair and deceptive" practices:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/10/the-courage-to-govern/#whos-in-charge

That means that the FTC doesn't need any further authorization from Congress to enforce an end to end rule: they can simply propose and pass that rule, on the grounds that telling someone that you'll show them the feeds that they ask for and then not doing so is "unfair and deceptive."

Some of the other proposals in the paper also fit neatly into Section 5 powers, like a "sticky" feed preference. If I tell a service to show me a feed of the people I follow and they switch it to a For You feed, that's plainly unfair and deceptive.

All of this raises the question of what a post-Big-Tech feed would look like. In "How To Break Up Amazon" for The Sling, Peter Carstensen and Darren Bush sketch out some visions for this:

https://www.thesling.org/how-to-break-up-amazon/

They imagine a "condo" model for Amazon, where the sellers collectively own the Amazon storefront, a model similar to capacity rights on natural gas pipelines, or to patent pools. They see two different ways that search-result order could be determined in such a system:

"specific premium placement could go to those vendors that value the placement the most [with revenue] shared among the owners of the condo"

or

"leave it to owners themselves to create joint ventures to promote products"

Note that both of these proposals are compatible with an end-to-end rule and the other regulatory proposals in the paper. Indeed, all these policies are easier to enforce against weaker companies that can't afford to maintain the pretense that they are headquartered in some distant regulatory haven, or pay massive salaries to ex-regulators to work the refs on their behalf:

https://www.thesling.org/in-public-discourse-and-congress-revolvers-defend-amazons-monopoly/

The re-emergence of intermediaries on the internet after its initial rush of disintermediation tells us something important about how we relate to one another. Some authors might be up for directly selling books to their audiences, and some drivers might be up for creating their own taxi service, and some merchants might want to run their own storefronts, but there's plenty of people with something they want to offer us who don't have the will or skill to do it all. Not everyone wants to be a sysadmin, a security auditor, a payment processor, a software engineer, a CFO, a tax-preparer and everything else that goes into running a business. Some people just want to sell you a book. Or find a date. Or teach an online class.

Intermediation isn't intrinsically wicked. Intermediaries fall into pits of enshitffication and other forms of rent-seeking when they aren't disciplined by competitors, by regulators, or by their own users' ability to block their bad conduct (with ad-blockers, say, or other self-help measures). We need intermediaries, and intermediaries don't have to turn into rent-seeking feudal warlords. That only happens if we let it happen.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/11/03/subprime-attention-rent-crisis/#euthanize-rentiers

Image:

Cryteria (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#rentiers#euthanize rentiers#subprime attention crisis#Mariana Mazzucato#tim oreilly#Ilan Strauss#scholarship#economics#two-sided markets#platform decay#algorithmic feeds#the algorithm tm#enshittification#monopoly#antitrust#section 5#ftc act#ftc#amazon. google#big tech#attention economy#attention rents#pecuniary rents#consumer welfare#end-to-end principle#remedyfest#giant teddy bears#project nessie#end-to-end

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

The rationalisation of space under capitalism is one facet of the ideology of progress which has had a profound impact on the spatial organisation of society in nature. Marxist geographer David Harvey writes that ‘capital accumulation and the production of urbanisation go hand in hand’. For Harvey, urbanisation is a physical manifestation of the drive to produce a ‘rational landscape’ in which barriers to the turnover time of capital accumulation are removed. In this sense then, letting space lie fallow introduced unacceptable friction into the capitalist system. Highlighting this shift, urban and environmental geographer Matthew Gandy notes that ‘the very idea of rest, and of resting space in particular – letting the earth sleep – counters the accelerative and all-encompassing momentum of late modernity’. The incongruity, however, isn’t just a question of an anxious space of late modernity. The instrumentalisation of space is already apparent in the mid-19th century, when Ildefons Cerdà’s opening statement for urbanisation sought to ‘fill the earth’. And by the early 20th century, this programmatic vision for design was fully institutionalised when Ebenezer Howard’s seminal Garden Cities project ‘sought to maximise functionality through territory saturated with activity’.

Time is also rationalised and subsumed under the growth imperative, which legitimates practices used to force people into reconfigured social relations. As critical urban theorist Alvaro Sevilla-Buitrago remarks, for example, ‘improvers couldn’t stand idleness, regardless of whether it referred to a quality of land or to poor commoners “wasting” productive time by contemplating their grazing livestock instead of embracing wage discipline as day labourers’. It was the capitalist project to proletarianise the population that transformed social relations connected more with ecological rhythms into the realm of the abstract rhythms of capitalism. Put another way, wresting productivity from humans – and non-humans – through labour discipline has always been a central feature of the project of capitalism, from the Enclosure Acts in England until today. Capturing ‘wasted time’ also had another social dimension: the production of new forms of citizenship meant to underpin the bourgeois vision of the modern metropolis. In New York City, for example, Sevilla-Buitrago interprets the construction of Central Park as a ‘special kind of enclosure … [that was meant to] shift behaviors from one regime of publicity to another’ in a battle that pitted the elite against the commoning practices of the New York City streetscape by recently arrived immigrants. While geographer Tony Weis has shown that the slow rhythms and periodic pauses of fallowing can influence social organisation in potentially progressive ways, we see above that the devaluation of idleness has instead promoted a capitalist subject synchronised to the rhythms of capitalist time.

Taken as a whole, the move to valuing progress over fallowing signalled a regime change that rationalised space and time, which, in turn, produced radical social, ecological and continuous urban transformations that, today, are felt on a planetary scale. Viewing the planet as a kind of perpetual growth machine with a core purpose of chasing profits, an ever-growing metabolism, is churning the earth in successive waves of creative destruction. This results in both acute and chronic pathologies of devalued human social relations, diminished diversity of the biosphere and a continually transformed urban fabric at ever larger scales. What impact has the growth imperative had on the design professions? Embedded in, and arguably a tool of, capital, the design professions have been criticised as largely geared towards solving the problems of wasted space to restore class relations and processes of accumulation. Can a design culture that sees itself as inextricably linked to growth retrain its analytical lens on social and ecological value production that exists outside capitalist sociospatial relations, rather than viewing moments of inactivity merely as opportunities to promote the next growth cycle?

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

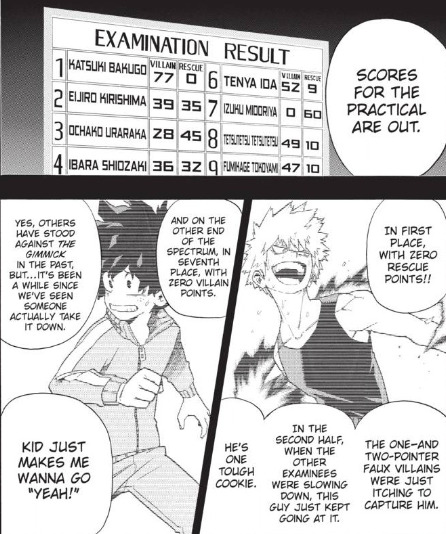

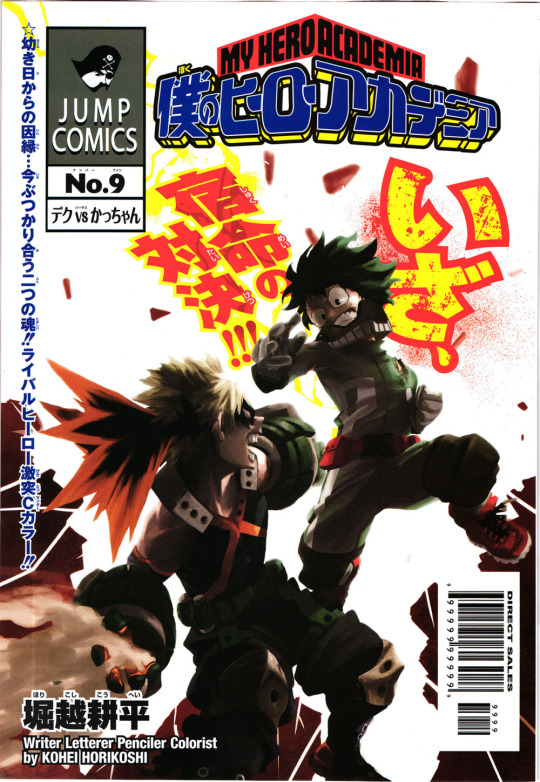

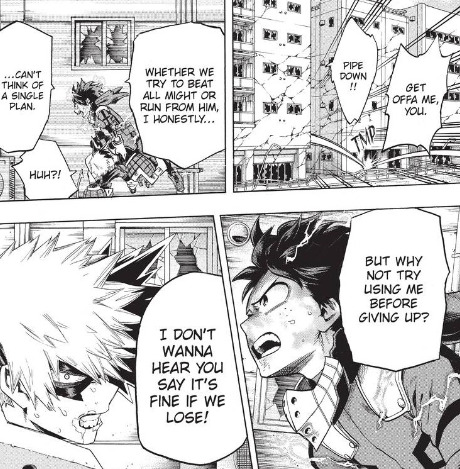

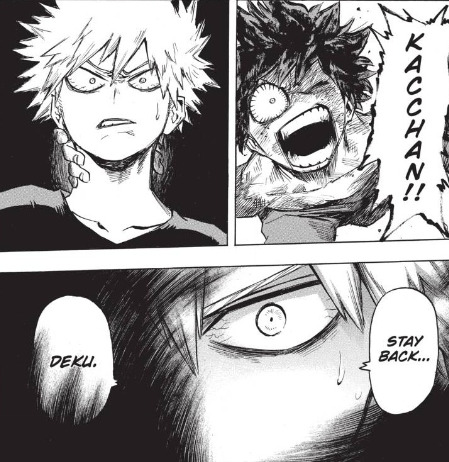

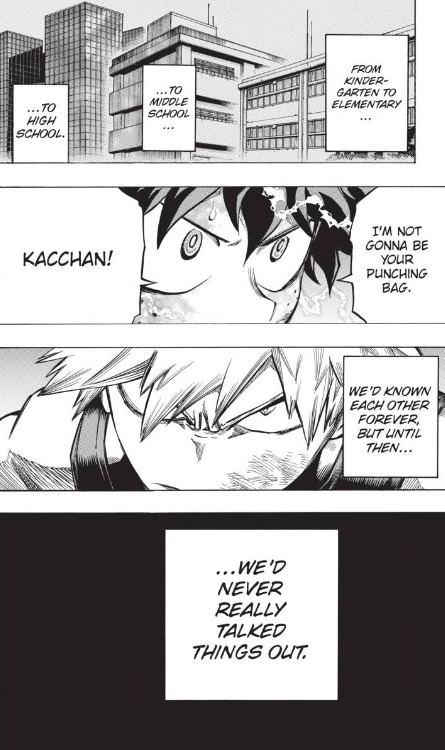

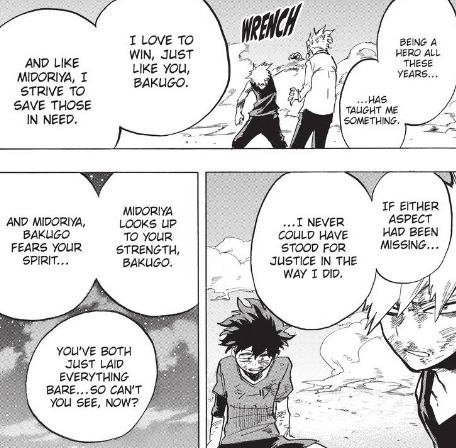

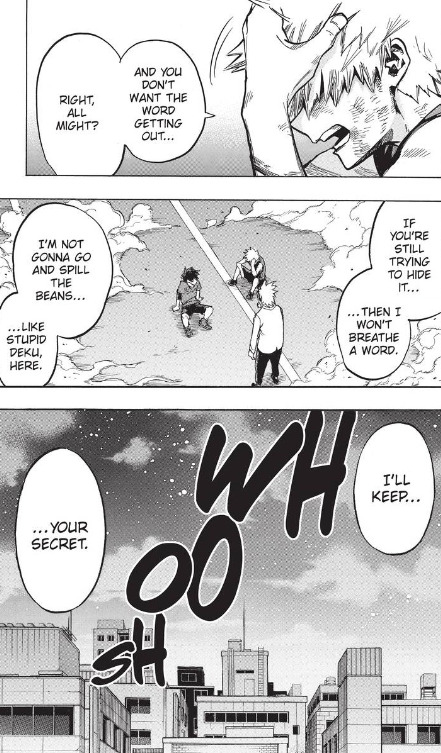

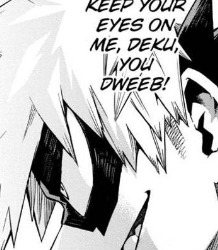

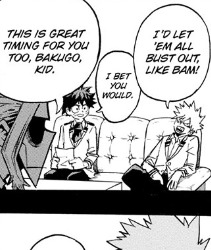

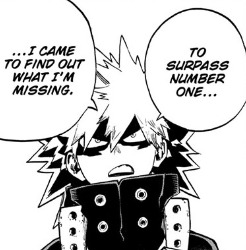

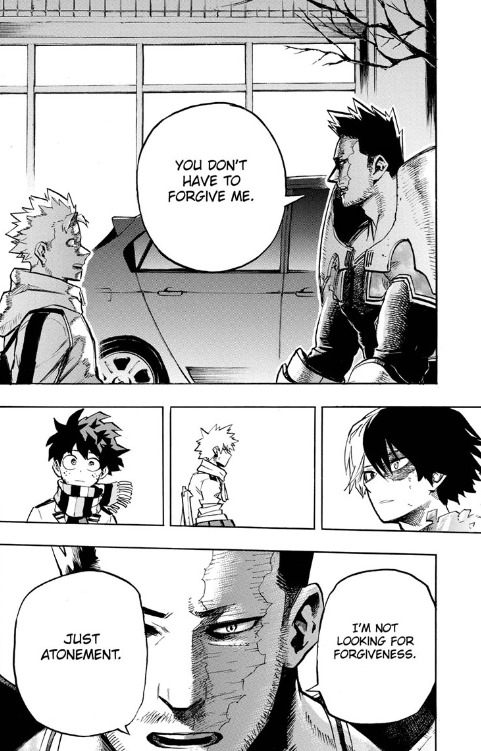

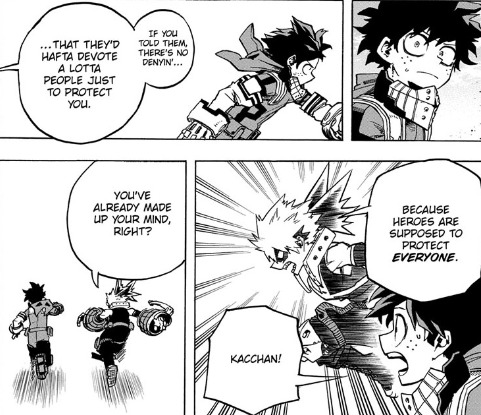

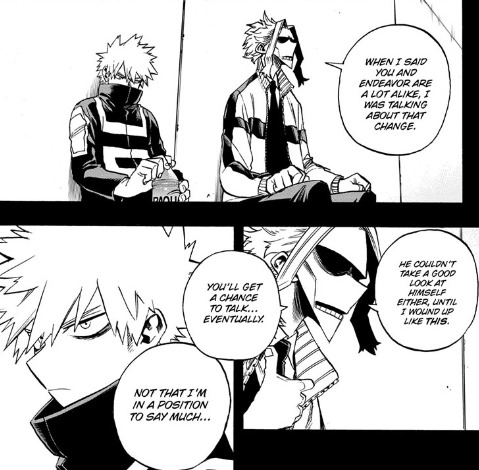

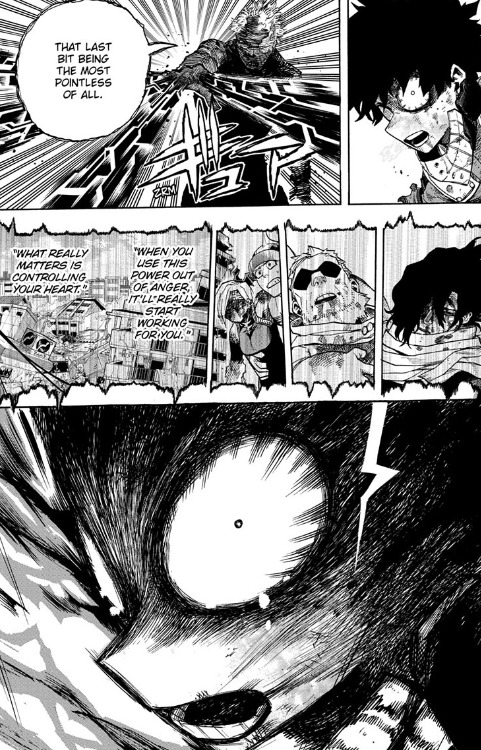

this is just a post listing all of the scenes in BnHA which underline Bakugou’s narrative importance and the way that it’s intrinsically connected to Deku and his storyline, because I really want to emphasize that the MORE THAN 300 CHAPTERS OF BUILD-UP just slightly outweigh the literal seven chapters in which he hasn’t played a major role just lately. recency bias is a thing guys, and we should all try to remember that.

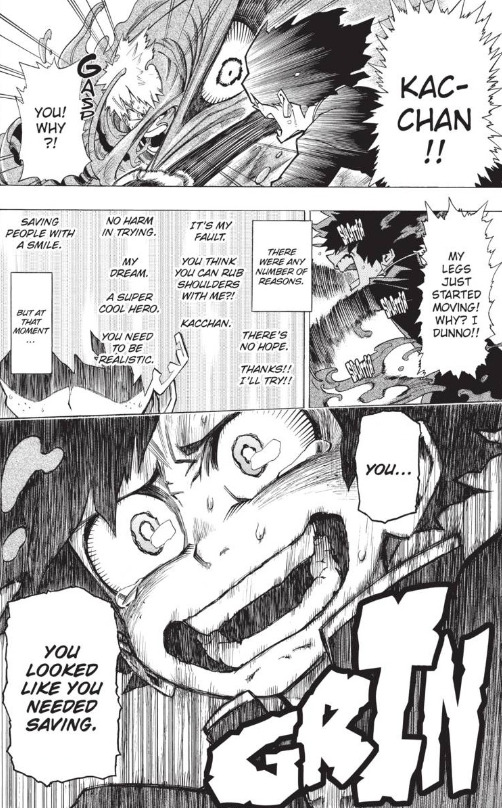

not Kacchan establishing his goal and ultimate endgame less than one page after his introduction.

not Kacchan being saved by Deku less than an hour after burning his notebook and telling him to jump off a roof, establishing the contradictory nature of their relationship right from the get-go, and changing Deku’s destiny forever as All Might witnesses this moment and realizes that Deku is more heroic than he ever could have imagined. “you looked like you needed saving.” that’s a line that’s already had at least one callback, and with Deku now struggling in the current manga the time could be ripe for an even more powerful one.

not “win and save” being established as the two cornerstones of the hero philosophy all the way back in chapter 5, with Deku and Kacchan each embodying one of these dual aspects, and being narratively primed to walk opposite paths in their respective hero journeys, only to meet at the middle when they reach the end.

not Deku and Kacchan having an iconic battle less than ten chapters into the series, during which their rivalry is further established and the complicated history of their childhood friendship is expanded on.

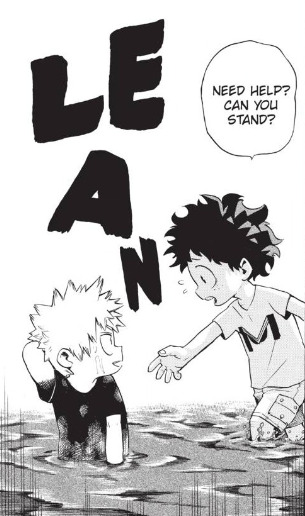

not Kacchan’s first childhood flashback revealing that the pivotal, character-defining event of his childhood was baby Deku reaching out his hand and asking if he was okay.

not Deku instinctively reaching out to Kacchan yet again all of two chapters later, making a fateful decision which will have massive ramifications down the line and which will eventually alter the course of Kacchan’s character development.

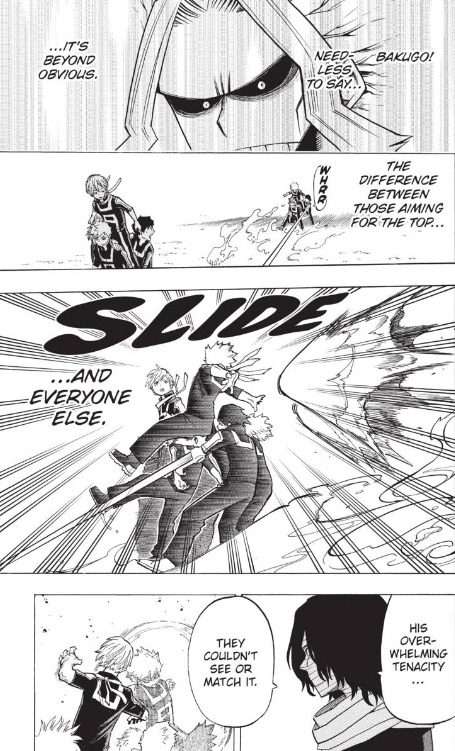

not Kacchan’s teachers thoughtfully praising his “overwhelming tenacity” and All Might noting his potential for greatness early on the series.

not Deku choosing a hero name originally given to him by Kacchan, but repurposing and reclaiming it, and possibly paving the way for another parallel that’s just waiting to be capitalized on. Kacchan feel free to tell us more about your own hero name’s meaning whenever you get a chance.

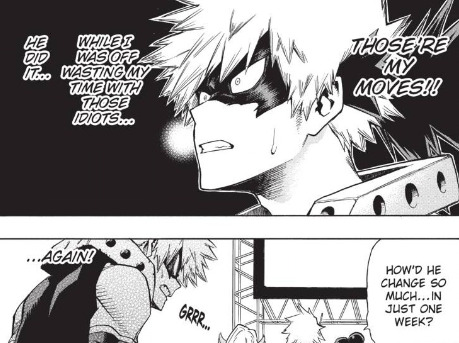

not Deku becoming stronger by learning from Kacchan (win to save).

not Deku and Kacchan deliberately being paired together for their final exam and Kacchan having a fucking meltdown until Deku literally knocks some sense into him, at which point he immediately gets his head back on straight because the two of them are capable of getting through to each other in a way that nobody else can.

not All Might being all “THIS FIGHT SURE IS SOME GREAT FORESHADOWING FOR THE TWO OF THEM TEAMING UP TOGETHER IN THE FUTURE AS FORETOLD BY DESTINY.”

not Kacchan becoming stronger by taking a page out of Deku’s book (save to win).

not Deku being the last person Kacchan sees before the LoV take him away, and the two of them locking eyes until the last possible second before Kacchan disappears and Deku literally falls to his knees screaming in the most dramatic breakdown of the entire series.

not the two of them being singled out in a crowd of hundreds and framed side by side desperately cheering on All Might in his darkest hour in the battle which will change the entire course of the series.

not Aizawa literally saying that class 1-A revolves around Bakugou and Deku.

not Deku and Kacchan having the most iconic battle of the entire series and being all “goddammit I can’t figure out why my entire life revolves around you and it’s driving me crazy” and being fully honest with each other for the first time in their lives, and then having All Might come over and tell them “you two need each other, and you need to learn from each other, because each of you intuitively understands part of what it means to be a great hero, and by working together you will both one day be able to rise to the top.”

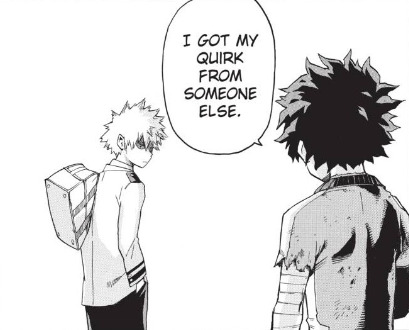

not Kacchan, and only Kacchan, being inducted into Club OFA a full two hundred chapters before anybody else.

not Kacchan and Deku obsessing over showing off for each other in the Joint Training arc while All Might looks on like a proud dad.

not Kacchan’s phenomenal progress in the JT arc being traced directly back to the lessons he learned from All Might and Deku.

not Deku being triggered into activating a wholeass new fucking quirk because someone said something mean about Kacchan.

not Horikoshi answering the question of “so what’s next for Kacchan’s character development?” with “he’s going to begin the slow burn process of realizing that he needs to make amends to Deku.”

not Kacchan being focused on Deku during Tomura’s attack on Jakku, and realizing what he’s about to do, and immediately moving in step beside him without the slightest hesitation because he’s determined to stay with him and protect him.

not All Might literally saying “THEY WILL GET A CHANCE TO TALK YOU GUYS SO JUST BE PATIENT.”

not Kacchan unconsciously emulating Deku when he’s focused on saving, and mimicking everything from his exact style of strategizing down to his speech patterns, in the exact same way that Deku starts unconsciously imitating Kacchan’s own mannerisms and speech when he’s focused on winning.

not Kacchan’s milestone “Rising” chapter being explicitly centered around this transcendent moment when he reacts without thinking in order to save Deku’s life.

not Deku activating a wholeass new fucking quirk AGAIN because someone insulted Kacchan AGAIN.

not Kacchan being all “Deku’s not the only one whose quirk goes through Awakenings when he sees that his childhood rivalfriend is in danger.”

not Kacchan having an entire character arc devoted solely to the importance of him choosing a hero name, which he has yet to reveal to Deku.

last but not least, not a whole entire montage of Horikoshi interview quotes with him talking about the thematic importance of “win to save, save to win” (it’s literally what heroism means to him), and talking about Bakugou’s future, and how he’s determined to write an even better ending than the one in Heroes Rising, and how the story will have a conclusion where all of the characters come together in the end.

so yeah. just in case it isn’t clear from all of this,

Bakugou and Deku’s destinies are intertwined in a way that runs deeper than any other connection in the series

the two of them have spurred on each other’s growth throughout the entirety of the manga

their character development has revolved around each other literally from the start

their journeys mirror and complement each other in a way that enriches the narrative

they each represent one half of All Might’s legacy

and their bond is at the center of the series’s emotional resonance

and Horikoshi is not just going to all of a sudden forget all of that and ignore it entirely in the series’s final act. I literally can’t understand why anyone would think that. it’s all right there you guys. 300 chapters’ worth of history and development. this is how it is, and this is how it has always been. like it or not, these two idiots are both in this together, and their respective endgames are inextricably tied to one another. win and save, you guys.

#bnha meta#bakugou katsuki#midoriya izuku#bakudeku#bakugou meta#deku meta#bnha#boku no hero academia#bnha spoilers#mha spoilers#bnha manga spoilers#makeste reads bnha#fifty-one images in this post lol#tumblr you have such a good thing going on right now seriously#why would you want to change that#is it because people like me keep making gigantic posts with fifty images apiece#don't answer that

457 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I’ve read the book A Game Of Thrones...

...thus now I’ll inflict this post nobody asked on you because I am like that.

I’ll be honest, I had had the books in my possession for a few years, but, as you probably know, you don’t choose when you read a book, the book chooses the right time to be read. Especially in this case, it didn’t feel right to read the books while the show (which had I been following weekly since... season 5 maybe? I’m bad at keeping track of this stuff) was ongoing, ergo now the timing finally felt right. So I brought the first book with me on my vacation, and I’ve read it mostly on the beach.

(Yeah, the chapters about the north and winter are kind of weird to read while you’re happily roasting under the sun, sitting on a banana-shaped inflatable seat and floating on the water, but hey.)

It’s been a while since I watched the first seasons of the show so my memories of it are shaky, but from what I remember the first season followed the plot pretty closely, and the main differences are in tone (the show going kinda overboard with a pretty pointless crassness) and in a less “channeled” point of view for obvious medium reasons since GRRM tells the story strictly through the eyes of a pretty limited array of characters while a visual medium won’t do that. (I’m assuming the books progressively increase the number of point-of-view characters, considering just a few of them die, at least any soon?)

Before reading the book, I thought the younger age of the characters compared to the show would rub me the wrong way, but I’ve found it to be a non-issue, both because the “voice” of the younger characters is not overly unrealistic for kids their age (at least not too much to break my suspension of disbelief), because the story itself acknowledges that they’re young and makes a point of it (I’m thinking Robb having to be Lord Robb, for instance), but also because the tone of the book is not as exaggeratedly sexual as I remember the early seasons of the show to be.

I’ve only read the first book so I don’t know if the tone stays consistent, but I’m suspecting that most of the “grimdark” accusations that are moved to the series are from people who think they know what the series is like. It’s dark - no doubt about it - but it’s about people for whom life isn’t meaningless, for whom values and emotions and relationships aren’t meaningless. But okay.

The plot of the first book made me roll my eyes again at how the show handled its final portion - the story originally took form around the Stark-Lannister conflict, and of course a billion other players appeared on the board and that wasn’t the core of the plot forever, but still the show decided that Cersei who? also who cares about the idea of “noble families squabble pointlessly while these threats develop from north and south”, ta-da, let’s just put everything in a cauldron and cook a soup with no narrative structure. The show has its last conflict between Dany and a Cersei-shaped cardboard figure, and it has to climb glass in order to make it compelling at all (literally the two characters have no personal history, Missandei had to die because otherwise there was no reason for Dany to have a personal investment in defeating Cersei other than she was the random person sitting on the throne she claimed for herself... The conflict between them was hyper-rushed, nothing made sense but happened because the plot said so, meanwhile Arya Stark is just there and doesn’t even catch a glimpse of the one person she’s always meant to kill more than anyone else, Sansa Stark who is the character who had the closest connection to Cersei in the narrative outside of the other Lannisters is just in Winterfell sitting there and probably knitting a sweater or something while foreshadowing freezes outside, and everyone else just... is there. Okay.

On the other hand, I can very well believe that GRRM’s indications for Dany’s ending would be, you know, going “mad”, because I can see that that was his intention all along - obviously I don’t know how the story will end but the impression I’ve got from Dany’s arc in the first book is that the whole point is that it’s a tragedy, and, sure, it’s possible that she’ll break what is essentially a curse inside her, but I don’t think so. The feeling I’ve gotten especially from the last few Dany chapters is that the point of her story is that her transformation into a “dragon” (waking the dragon, if you prefer) is an actualization of a curse that ran in her blood and now takes a hold on her. Her rising from the fire is actually the beginning of her fall, or better, there is no rise or fall, there is just the dragon curse she could never escape because it was her destiny all along, and she never really had choices anyway. The birth of her son and his simultaneous death, the birth of the three dragons instead, and everything else, awoke the dragon in her, and dragons are no nice, benevolent creatures. Her personality might be loving and benevolent, and I know she’ll act on those traits in the future, but the Targaryen curse flows in her. Obviously the dragon madness is inextricably interlaced with grief, and indeed it’s all about death - Dany’s own, after all, because the girl dies and the dragon is born from the fire, and while she’s still herself and undoubtedly still carries qualities she had before, the curse that lied (almost) dormant in her has finally taken ahold of her. I wonder if she’ll break free of the curse eventually - but it seems unlikely given how the story starts, the very act that makes her acquire power is something that just grabs her more tightly inside what I can’t see but a curse from how the author describes it.

The first book was pretty much introductory for many characters (not Ned’s, bye Ned), Arya’s and Sansa’s journeys have just been set in motion, Bran’s is sort of on hold waiting for being truly set in motion, while Tyrion and Dany have sort of similar arcs, a journey of acquiring agency, although in very different ways, for Tyrion he literally becomes a prisoner and struggles to get back home (not literally but to his family and his “place”), for Dany she starts literally as an object sold from man to man and eventually finds her “place” with the dragons and her own khalasar, and both of their stories will basically re-start from there. I don’t really remember the narrative structure of Catelyn’s chapters, maybe that’s the point, she’s always in motion, almost like she’s spinning. Asfghjkl I forgot Jon. His arc is also an introductory one, at the end of which he embraces the Night’s Watch as his family and his place.

The most disturbing part in the book, for me, would be Tyrion’s farce trial in the Eyrie. I suppose that Lysa Arryn and Littlefinger murdered Jon Arryn in the books too (the foreshadowing is there) and that knowledge made the scene extra creepy. I suppose I feel strongly in general about narratives about a lack of a lawful judicial process, of characters being falsely accused of things and being denied actual trials, which is something for instance JK Rowling plays with a lot to create the most disturbing situations in the Harry Potter books (it works) and incidentally a reason why Captain America: Civil War could have been a powerful movie if they hadn’t fucked it up thoroughly. Had I been tasked with writing the Captain America 3 movie, my plot would have involved a farce trial for Bucky (and possibly other characters) masqueraded as perfectly fine, and the characters finding out that the authorities behind the whole thing are the wider Hydra network that didn’t come up in the internet leak. People in power abusing their authority makes for powerful narratives, but nooo, the real bad guys have nothing to do with the authorities or the government and also... Steve Rogers is a bad guy too, because fuck you. Long live capitalism and right-wing ideologies amiright.

I’ll take this detour away from the book as my clue to end the post, but please feel free to come chat with me or ask my thoughts about anything related to the book! 😊

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Objects of Ourselves

The fabricated commercial object is one that is easy to understand. They're often designed to read clearly, and packaged with a narrative around its values and history as a brand in order to sell. Compared to the somewhat murky and difficult task of defining an individual human identity, objects, and especially branded objects, are seductively straightforward. So it seems almost inescapable that with the rise of mass production and consumer culture originating in the United States following World War II, the object becomes inextricably wrapped up in matters of personal identity. During this time, a great volume of artistic work began to probe the complex ways these objects relate to identity, as well as create identities of their own. Sometimes these objects represent ideals of identity, and other times serve as a means to understanding and realizing identity itself.

It might seem a little bit jarring to talk about something as individual as identity as being heavily influenced by mass produced objects, whose very indistinguishability from one another might seem antithetical to the uniqueness implied in our conceptions of identity. And perhaps even more so tracing these connections back to the United States, with its cultural prioritization of the individual over the collective. Yet, this seems almost inescapable given the combination of new media technologies that could reach more people than ever before when combined with American capitalism. As stated by Marshall McLuhan in his essay "Understanding Media," "after more than a century of electric technology, we have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace... Rapidly, we approach the final phase of the extensions of man— the technological simulation of consciousness, when the creative process of knowing will be collectively and corporately extended to the whole of human society" (754). Consciousness became a collective experience with these new technologies, something McLuhan dubbed "the global village," and these societally shared experiences understandably lead to a sort of shared, common identity. And these communication technologies were immediately appropriated by corporations who, armed with them, could advertise to a larger audience than ever before and sell them all the same thing, and in selling them all the same exact product could take advantage of economies of scale to create higher profits than they'd ever made before. The most efficient context for American capitalism to run under, it became clear, was one in which uniformity of advertising lead to uniformity of desire, which in turn lead to uniformity goods purchased. And, as some of the artists in this exhibition will demonstrate, these purchased objects themselves provided a unifying effect in creating readymade identities.

In talking about these matters, it's necessary to talk about the art movement that was one of the first to directly concern itself with these matters of consumer culture: the pop art movement. Appropriating the style and imagery of advertising as well as the mass produced found objects of the 1950s and 60s, pop art challenged what could and couldn't be considered as high art, and in doing so questioned whether the sort of meaning and value found in fine art and its more rarefied and individual production could also be extended to the ubiquitous and cheap consumer objects of the era. Of course, the impact all of these objects and questions of their meaning on issues of identity wasn't lost on these artists. In response to mass media and a shared set of American brands, Andy Warhol in an interview with Gene Swenson provocatively declared "“I want everybody to think alike... Everybody looks alike and acts alike, and we’re getting more and more that way" (747). Whether or not Warhol actually believed these statements and how good of a thing these observed effects were, however, is less clear, and in doing so the space becomes much richer in the questions this ambiguity poses.

Are these objects and their effects on identity actually a bad thing? Do mass produced objects sold by corporations take away individuality in their consumers, or is identity something more resilient than that? And how much individual meaning can be found in reproduced objects? Is it, like what's accepted to be true with fine art, something that is dependent on the viewer, and thus individual and unique even if the observed object is the same as what everyone else is viewing?

This exhibition looks at works beyond the pop art movement, spanning a range from the 1960s to the 2010s, as some other interesting developments in discussions of objecthood happened in other movements such as Minimalism. But, plenty of works in this exhibit have also been included where questions of objects and identity might not be at the forefront or explicit at all. These works have been included as they allow for a more nuanced and holistic interpretation of what we mean by objecthood; how to read objects and extend those readings to things that are less clearly or tangibly "objects," such as in Untitled Film Still #6; the relations between objects and various social and economic factors, such as in Soup Can and Sunset; and, perhaps most interestingly, how objects can be a source of empowerment, such as in The Liberation of Aunt Jemima; or even self reflection and mythologizing, as in My Bed and Narcissus Gardens. The works have been organized in a progression that starts from the most obvious consequence of these objects, their economic signifiers, and works its ways to how they relate to ourselves in the most intimate ways concerning matters of our purpose, permanence, and understanding of our self.

0 notes

Text

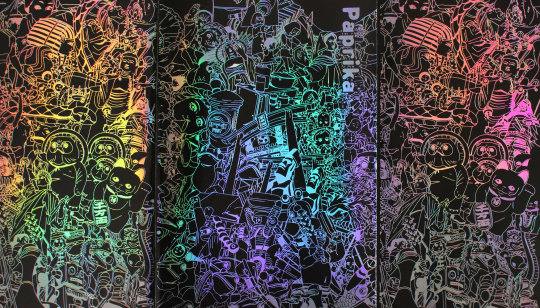

ESSAY: Globalization - Limits & Liminality as Explored in “Paprika”

Kon’s animated film Paprika, through symbolic and stylized means, serves as a critical frame for the phenomenon of globalization.

X-Posted at Pangaea Journal

Inspired by Yasutaka Tsutsui’s titular novel, Paprika begins much in the same fashion as it ends: in medias res, with a phantasmagorical montage of cultural iconography, quirky characters and surreal scenery interwoven at a frenzied pace, each scene jumping into the next with a fluidity that coalesces time and space itself into a distinctly Einsteinian continuum. Audiences are left dazed, disoriented, yet intrigued: there is no way to know whether the introductory sequence is chronicling a dream, or reality, or a freakish blend of both. This destabilizing visual narrative is fairly typical of Satoshi Kon’s craft, yet what calls for critical focus is the unique symbolism underpinning his work. Beneath its rich and densely-layered imagery, the film tackles a number of pertinent issues: from whether multimedia has warped from a benign platform into the jealous architect of our desires; to the tragic dissolution of individual ideas and complex cultures into a miasma of grotesque transnationalism; to whether the weakening friction-of-distance within a digitized world has brought us closer together, or merely distorted the very axes upon which time-space functions and is perceived. Indeed, at its crux, the film embraces a broad spectrum of issues uniquely linked to globalization, all while invoking relevant aspects of human fallacy and social degradation.

Central to Paprika, from the beginning, is its clear disdain for the linearity and two-dimensionalism of traditional narrative. Instead, like a hallucination, there appear to be no distinguishable boundaries between characters or places, no fixed destinations or rational coordinates. The most vivid example is the introductory sequence, where the eponymous protagonist, Paprika, leaps winsomely out of a man’s dreams and into the physical world: flitting from brightly-lit billboards as static eye-candy to a well-meaning sentry spying through computer screens to a godlike specter freezing busy traffic with a snap of her fingers to an ordinary girl chomping hamburgers at a diner to a stylized decal on a boy’s T-shirt to a motorcyclist careening through late-night streets (0:06:12-0:07:49).

Space and time are rendered meaningless – or, rather, are reshaped into something entirely novel and surreal. As Paprika navigates through a complex and dynamic mediascape, she effectively embodies the spilling-over of the virtual into the physical world – and, more significantly, of both the subtle and blatant permeation of media-based globalization in every step of our lives. Indeed, with its alternately fascinating and disturbing chaos of imagery, the very premise of Paprika blurs the boundaries between the inner and outer-worlds, conveying through both symbolic and subtextual allusions the phenomenon of globalization run riot – a dreamscape that unfolds with the benign promise of forging new connections, only to seep past the barriers of reality and engulf and reshape the world to the imperatives of dystopian homogeneity at best, and the subjugation and disintegration of individual autonomy at worst.

It can be argued, of course, that it is hypocritical for animation – in many ways the nexus of metamedia in its most intrinsically illusory form – to lambaste globalization. The media pivots on globalization in all its multifaceted vagaries, and vice versa. Renowned social theorist Marshall McLuhan, who coined the phrase ‘the global village’ in his groundbreaking work The Medium is the Message, was one of the first to point out that the form of a medium implants itself inextricably into whatever message it conveys in a synergistic relationship: “All media work us over completely. They are so pervasive in their personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical, and social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered (26).” That the media and the phenomenon of globalization go hand-in-hand, shaping and influencing one another, therefore goes without saying. However, what the imagery of Paprika draws attention to is how the multiplicity of media leads to unpredictable consequences and vicissitudes – which are not always quantifiable or even tangible. Much in the same way technology and global interconnectivity have narrowed – at times even erased – the demarcations of time and space, so too have they led to paradigm shifts of what it means to belong to a static, physical place as a cultural and individual identifier.

Globalization is often defined as fundamentally kaleidoscopic, with a dizzying mobility of ideological, economic, physical and cultural interchanges across a rhizomatous network – but one that is increasingly powered by its own unstable energies and its own besieged and untidy logic. Of particular interest is the ‘disembodied’ component of globalization, where the flow of information and capital is increasingly encoded and abstract, and thus increasingly more likely to permeate local spaces that may not always be open to such profound transformation, imposition and redefinition. In their work, The Quantum Society, Zohar and Marshall liken the chaotic, fractal nature of the modern world to quantum reality, stating that it

…has the potential to be both particle-like and wave-like. Particles are individuals, located and measurable in space and time. Waves are ‘nonlocal,’ they are spread out across all of space and time, and their instantaneous effects are everywhere. Waves extend themselves in every direction at once, they overlap and combine with other waves to form new realities, new emergent wholes (326).

Unarguably, the focal point in Paprika is globalization as a catalyst of “new realities.” But while these can be captivating and edifying, allowing us to create or explore new identities, or to grow more closely tethered together, they can also represent the sinister infiltration of exploitative elements within our most intimate lives. This is made chillingly evident through the plot of the film, which centers on the theft of the DC Mini – a futuristic device that allows two people to share the same dream. While intended as a tool to help treat patients’ latent neuroses and deep-seated pathologies, the film makes clear that, if misused, this prototype can not only allow an intruder to access and influence another’s dreams, but can unleash the collective dream-world into the sphere of reality itself. The DC Mini, on its own, would function as a tepid metaphor for the symbiotic dance between globalization and technology. But following its theft, the resultant chaos it invokes sets the riveting, psychedelic stage upon which the inner-world of dreams erupts out into mundane reality, a fantastical convergence that not only threatens the safety of the entire city, but also denies each citizen their own private realm of dreams, within which they have the freedom to nurture a true inner-self. As Dr. Chiba – the no-nonsense alter-ego of our dreamscape superheroine Paprika – remarks: the victims of the abused DC Mini have become mere “empty shells, invaded by collective dreams… Every dream [the stolen DC Mini] came into contact with was eaten up into one huge delusion.” The scene is made particularly memorable by its vivid visual symbolism: two droplets of rainwater on a car window merging into one, highlighting the irresistible flow between not only dreams and reality, but the liminality of globalization as a fluid force that cannot be bound by temporal or spatial delineations (0:52:12-0:52:37).

It is precisely this unpredictable fluidity that runs rampant across real-life Tokyo in the film, wreaking havoc in its wake. Of particular interest is the gorgeous riot of imagery employed to represent the collective ‘delusion:’ the recurring motif of a parade, in all its clamorous splendor, that unfurls through the city streets, infusing spectators with its own peculiar brand of madness. For its eye-popping and mind-bending details alone, the sequence warrants close examination. But accompanying the visual feast is the nightmarish gamut of cultural, technological, social and historical commentary embedded within its imagery. To the cheerful proclamations of, “It’s showtime!” a procession of Japanese salarymen leap with suicidal serenity off of rooftops; below, the bodies of drunkenly-staggering bar-hoppers morph into unbalanced musical instruments, while families frolicking through the parade transform into rotund golden Maneki-neko to disturbing chants of, “The dreams will grow and grow! Let’s grow the tree that blooms money!” Here, in a scathing political lampoon, politicians wrestle one another in their eagerness to climb to the top of a parade-float; there, a row of schoolgirls in sailor uniforms, with cellphones for heads, lift their skirts for the eager gazes of equally cellphone-headed males.

Satoshi Kon does not bother with coy subtext; he announces the mind-degenerating effects of globalization on both dramatic and symbolic planes: a parade that swells into disorder and eventual destruction, headed by a clutter of sentient refrigerators, televisions, microwave ovens, vacuum cleaners, deck tapes and automobiles. Traditional Japanese kitsch competes with lurid Americana; cultural symbols like Godzilla and the Statue of Liberty waltz alongside such religious icons as the Virgin Mary, Vishnu and the Buddha, while disembodied torii arches and airplanes soar overhead to the discordant serenade of money toads and durama dolls. The effect is at once hypnotic and horrific; the vortex of collective dreams lures in countless spellbound bystanders, transforming them into just another mindless facet of the parade, from a robot to a toy to a centerpiece on a parade-palanquin. Witnessing the furor, one character dazedly asks, “Am I still dreaming?” and is informed, “Yes. The whole world is” (1:11:09-1:12:42)

In her book, Girlhood and the Plastic Image, Heather Warren-Crow remarks that Paprika “…proffers a visual theory of media convergence as not only an issue of technology, but also one of globalization… [Its] vision of media convergence is one in which boundaries between cultures, technologies, commodities and people are horrifyingly permeable… While our supergirl is eventually able to stop the parade… these multiple transgressions cause mass confusion, madness, injury and death (83).” If this seems a dark denouncement of globalization, one cannot deny that it is in many respects fitting. With the vanishing delineations between nations, cultures, ideas and people arises the phenomenon of “cultural odorlessness,” or mukokuseki. The term was first applied to rapid social transformations in Koichi Iwabuchi’s book Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism, although the phenomena can just as readily be applied to postmodernity in all its miscellaneous facets (28). While globalization has engendered new intimacies and easier connections (on the surface), this overwhelming grid of interconnected information has simultaneously become a web trapping human beings inside it. Individuality – on a national, local, or personal scale – has been pushed aside in favor of a real and virtual superhighway powered by pitiless self-commodification and voracious consumership, within which the cultivation of a true self no longer holds meaning. One particular scene in the film captures this with wistful succinctness. As a weary Dr. Chiba gazes out of the window of her office, her livelier alter-ego Paprika (real or imagined) appears superimposed before her reflection. “You look tired,” Paprika says, “Want me to look in on your dreams?” to which Chiba replies, “I haven’t been seeing any of my own lately.” Against Paprika’s winsome overtones, her own demeanor strikes a chord that is dismal in its flatness. Although Chiba’s profession is to dive through the colorful welter of others’ dreams, it is her grasp of her own self that proves the ultimate fatality in this venture (0:24:10-0:24:23).

Indeed, it has often been argued that as both the physical and disembodied aspects of globalization grow increasingly more pervasive, so too do diverse organs of surveillance – from institutionalized dogmas meant to restrict personal development by branding it as outdated or subversive, to internal and external disciplinary structures meant to monitor and subjugate a person’s ‘inner-self:’ the very stuff of his or her dreams. Such themes, while hardly novel, are nonetheless relevant, tethered as they are to such iconic works as George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, and Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, both of which – through literal and metaphorical means – examine societies wherein people are subject to relentless government scrutiny, mind-policing and the absolute denial and denigration of privacy. Foucault’s work, in particular, is useful for deconstructing social mechanisms. Utilizing a genealogical historical lens, Foucault traces the slow and oppressive transformation – as opposed to ‘evolution’, a phrase often touted by proponents of liberal reform – of the Western penal system. His main focus is to illustrate how, despite our self-congratulatory complacence at moving away from the barbaric model of medieval punishment, in favor of gentler and more civilized modes of discipline, we have in fact simply transferred the imperatives of controlling human beings – be they deviants or conformists – from their bodies to their souls. As Foucault states, “Physical pain, the pain of the body itself, is no longer the constituent element of the penalty. From being an art of unbearable sensations punishment has become an economy of suspended rights,” thus intimating that the organs of institutional control have not grown less harsh or restrictive, but simply less overt (11).

Certainly, by relying on a framework of internal rather than external constraints, it has become possible to erode the very modicum of individuality, reducing human beings to what Foucault describes as “docile” bodies complicit in their own exploitation. Foucault lays the blame for this phenomenon on a capitalist system whose economic and political trajectory has led society to a place of commodification and classification (“governmentality”), where the complexities of dynamic individuals are pared down into reductionist categories of ‘acceptable’ or ‘unacceptable.’ According to Foucault, surveillance and regimentation as a means of producing compliant individuals is the crux of modern economies, to the point where society has transformed into an industrial panopticon – a nightmarish perversion of Jeremy Bentham’s original ideal. As such, whether individuals live as offenders within a prison, or as free citizens, is irrelevant. The scant difference in both their constraints is measured by mere degrees (102-128).

In Paprika, these issues are not explicitly announced, but are instead woven through the story’s fabric in an alternately lulling and disquieting fashion. Noteworthy scenes – such as where Paprika, a captive chimera with butterfly-wings, is pinned to a table while a man literally peels away her skin to paw rapaciously at the prone body of Dr. Chiba, nestled pupae-like within, to the moment where Detective Toshimi Konakawa, harried by recurring nightmares, bittersweetly comes to terms with boyhood dreams he had suppressed in order to survive by the dictum of a cold and prescriptive adult world – are all reminders that it is our inviolate inner-space that makes us uniquely human. To allow it to be invaded, subjugated and erased is to reduce ourselves to passive automatons, our every desire governed, our every choice predetermined. In Paprika, this knowledge blossoms only when each character delves deep into themselves, to find at their core the dream-child that remains untouched by reality’s smothering hold, and to discover within that dream-child both untapped softness and strength. “She’s become true to herself, hasn’t she?” Paprika playfully remarks of the somber Dr. Chiba, when the latter finally comes to terms with her repressed affection for the bumbling genius Tokita (1:15:42).

For Paprika, it is evident that social or technological transformations cannot be powered by the erosion of individual dreams. To do so is to condemn the world to an eldritch darkness sustained only by greed. The film’s penultimate scene, where the egomaniacal chairman – the true thief of the DC Mini – looms as a monstrous giant over the despoiled city, proclaiming, “I am perfect! I can control dreams and even death!” could almost serve as the critical foreshadowing of globalization taken to its bleakest conclusion: the desecration of nature and humanity alike by a self-serving force that, in its thirst for absolute control, will cancel out the very diversity of dreams that once made globalization possible. It is only when Paprika – fusing with Dr. Chiba and Tokita – reemerges in the form of a baby to battle the chairman, is equilibrium restored. “Light and dark. Reality and dreams. Life and death. Man and woman. Then you add the missing spice [Paprika],” she recites, as if listing ingredients to a recipe (1:19:50-1:20:32). Yet, in keeping with theme of liminality and indeterminacy, the key to vanquishing the chairman is not in these binary oppositions, but in their capacity to combine together and shape the world into more than one thing at once. As Paprika swallows the chairman whole, reversing the shadowy post-apocalyptic city to its original state, battle-scarred but still intact, the audience is reminded of fluidity of the quantum world. Life and death, dreams and reality, destruction and rebirth, all coalesce within an ever-transforming continuum.

So too, as the film’s open-ended yet distinctly uplifting ending makes clear, is the process of globalization inherently free-flowing and malleable in its interaction with its environment. Rather than focusing on the split between globalization as a force of cultural erasure versus a celebration of differences, the film highlights the alternately delicate or brutal negotiations between the two: a friction that is necessary to keep the phenomenon in flux. Zygmunt Bauman’s book and selfsame concept of Liquid Modernity proves especially useful here, in that in order to comprehend the mutable nature of the modern world, it is necessary to look beyond traditional models and regimented perceptions. As he makes clear:

Ours is … an individualized, privatized version of modernity, with the burden of pattern-weaving and the responsibility for failure falling primarily on the individual’s shoulders… The patterns of dependency and interaction … are now malleable… but like all fluids they do not keep their shape for long. Shaping them is easier than keeping them in shape. Solids are cast once and for all. Keeping fluids in shape requires a lot of attention, constant vigilance and perpetual effort – and even then the success of the effort is anything but a foregone conclusion (8).

Of course, the exchange of images and ideas across a would-be deterritorialized realm does not mean that the myriad components within must lose their separate identities. Rather, those identities become more essential than ever, bringing with them their own consequences and questions – all of which must be understood through the dynamic lens of globalization, until we come to understand not only the frailties of the social order, but how they can improved, in order to make connections both genuine and mutually-beneficial for a polyphonic future. The answers lie not within the inherently-shifting structure of globalization, but rather in its creative use. In the film’s final segment, where Detective Toshimi Konakawa purchases tickets to the movie, Dreaming Kids, after decades of stultifying self-repression, speaks of the capacity of globalized multitudes to enthuse as well as to ensnare the individual’s dreams. Globalization does not exist in a vacuum; even as it threatens to engulf nations, localities and persons into a bilious swamp of depersonalized shells, so too can it be transformed by the nature of the worlds it encounters. The change is double-edged and double-sided; the effect is a living, breathing bricolage that grows and alters as we do – and how we do.

That said, it is evident that Satoshi Kon’s message is not one of a facile globalized utopia. Rather, it is about the dangers of losing ourselves within such a seductive phenomenon, whose effects can too easily be maneuvered toward mass surveillance and subjugation. For Paprika, the cross-flow of cultures, ideas, commodities and people is illustrated as an unceasing process, but one that we ourselves are responsible for shaping. If done right, there is the tantalizing promise of a happier, freer life, within which globalization may enhance rather than exploit our dreams. But if done wrong, Kon’s narrative is bleakly apocalyptic – a world fallen victim to a hostile and all-pervasive force that gnaws away its very humanity. While the film’s content-driven, as opposed to structural, formula can be mystifying and overly-abstract at times, there is no denying its visual ingenuity: a multimedia extravaganza that beautifully translates the welter of dreams into reality. With its alternately fascinating and disturbing chaos of imagery, Paprika blurs the boundaries between the inner and outer-worlds, conveying through symbolic and subtextual allusions the phenomenon of globalization run riot – a dreamscape that yields both brighter possibilities and special connections if we do not allow it to diminish us, yet also a sinister agency of mass domination and dystopian homogeneity if we fail to put it in its proper place.

Works Cited

Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge, UK, Polity Press, 2015.