#Woodland pottery sherds

Text

Over 9,300 pottery sherds were collected during 2008 excavations at one of the sites in the Sand Lake Archaeological District, near Onalaska, Wisconsin. Of those, nearly 160 rims and decorated body sherds were categorized into likely ceramic wares and types based on their grit or shell temper, form, and decoration. But categories created by archaeologists today to make sense of what people made in the past cannot neatly cover everything. A small group of anomalous sherds, all from different excavation units, had distinctive characteristics but defied classification into types. One grit-tempered rim (upper left) flares to a flattened lip and has a cord marked exterior surface. Another cord roughened grit-tempered sherd (upper right) thins to a rounded lip. It may fit the local Middle Woodland type Shorewood Cord Roughened. A third rim has a cord impression over a folded lip (lower right). It is grit-tempered but might also contain shell temper, a possible mix of Terminal Late Woodland and Mississippian clay preparations. One grit-tempered body sherd has parallel tool trails (lower left). It could be from a Terminal Late Woodland type vessel or from a rare grit-tempered Oneota pot.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

THANA

.: iapygian deity associated with deer :.

[IMG TRANSCRIPTION (mirrored): Ψana. IMG SOURCE: F.G. D’Andria, Archeologia dei Messapi (Bari: Edipuglia, 1990), 232.]

.: :.

Inscriptions dedicated to Thana are found in several locations across Messapia. One inscription is on a pottery sherd found at the sanctuary of Scala di Furno, where deer bones were also found, and surrounding sherds can be reconstructed to form part of the image of a fawn.

A few scholars suggest that since she is clearly associated with deer, Thana was thus syncretized with Artemis. However, plenty of inscriptions devoted to Artemis (spelled Artamis in Messapic) are also found across Iapygia, so they seem to have been two separate deities in this time and place.

Thana is also the name of a goddess found in Illyria (nearby in the modern-day Western Balkans), where she is a goddess of forestry and hunting. Thana is often portrayed with different iconography from Roman Diana or Greek Artemis; in Illyria, she’s nearly always paired with the deity Vidasus, another woodlands god.

.: :.

Sources:

J.-L. Lamboley, Recherches sur les messapiens (Roma: École Française de Rome, 1996), 431-432.

Maria Teresa Laporta, “Divinità femminili e titoli sacerdotali nel Pantheon messapico,” in Studia di antichità linguistiche in memoria di Ciro Santoro (Bari: Cacucci, 2006), 217-242.

Ciro Santoro, “Il lessico del ‘divino’ e della religione messapica,” in Atti del IX Convegno dei Comuni Messapici, Peuceti e Dauni, Oria 24-25 novembre 1984 (Bari: Societa di Storia per la Puglia, 1989), 139-80.

#i decided to give each deity their own post rather than making several lists#i figure this way i can both post more frequently and also i can come back and reblog w additions#bc i’m still waiting on interlibrary loan for several books#thana deity#artemis deity#(except not really)#diana deity#vidasus deity#hellenic polytheism#helpol#religio romana#cultus deorum#religio iapygiorum#syncretism

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

🌻

Morgan, there's nothing I can tell you about me that you don't already know so here's an infodump about an archaeological site that's near and dear to my heart:

Yankeetown Site is a prehistoric settlement along the north shore of the Ohio river and was home to a terminal Late Woodland settlement occupied approximately from 700 to 1100 CE. It was discovered when artifacts began washing out of the banks of the Ohio river in the 1930s.

The site is highly stratified, meaning that there are thousands of years of occupation that you can see as you scale the tall riverbanks. Clovis era fire pits can be found at the very bottom (8000–6000 BCE) up to Late Woodland (Hopewell) culture.

Here's a pottery sherd from Yankeetown:

The flakey bits are "grog" , AKA the pottery is tempered with little broken up bits of old pots and other ceramic. This is important because this is common in the Mississippian culture (800-1600 CE).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Outdoor Education Center IHS Land Lab

Tulip Trail

Independence, OH 44131

The Independence Local Schools’ Outdoor Education Center in Independence, OH, was once a Nike missile base and now more than 50 acres of protected land in the Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation area, the land has been restored to its former unspoiled condition. All forms of native wildlife, plants and animals are given an opportunity to redevelop to their maximum vitality in an environment with minimal human disturbance, according to Dr. Tien Wei Yang, an ecologist who assisted in the early planning of the center, which opened in 1970.

The center is not just a bird sanctuary, a wildlife refuge, an arboretum or a live museum, Yang explained. More than that, it is a place where young and old, can learn to make accurate observations of this redevelopment and this resurgence of life, to record and to interpret these observations. Managed by the students of the Biology Society at Independence High School -- and more affectionately known as the land lab -- this outdoor nature classroom and wilderness tract has been under the direction of only two advisers in its lifetime.

Founder William Taylor and current adviser Scott Maretka, who teaches biology at the high school, both share the same vision of exposing students to the outdoors and learning the importance of taking care of their natural environment. The facilities are used throughout the school year not only by Maretka’s science classes, but by other area school groups. Maretka and his Biology Society students host various nature activities and field trips for students as young as preschool, which he said gave him the idea of creating an outdoor education class for his high school students.

Maretka said the land lab impacts the community around it by providing the right habitat for a wide diversity of living organisms. The small pond is a breeding pool for the spotted salamander. Every student that comes through Independence Schools has an opportunity to experience outdoor education at the land lab, according to Superintendent Ben Hegedish. This land acquired from the federal government in the late 1960s has been a treasure to the Independence Local Schools for generations. Hegedish understands the fierce passion to protect the land lab and he shares this passion, too.

The Outdoor Education Center (OEC 1 Site), a Independence Board of Education building, is also an archaeological site of prehistoric people of the Whittlesey culture and earlier. It is located in Independence, Ohio, in a wooden nature preserve along the Cuyahoga River. Animal bones, Madison point stone tools, and Tuttle Hill decorated pottery sherds were attributed to the Whittlesey culture. The excavated items were found over a dispersed area in 1999 by a group led by Mark Kollecker, Supervisor of Archaeology Field Programs of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. From the several excavations, the village sat on two to four acres.

Kollecker led another Archaeology Field Experience program group in April and May 2000 and found several post molds and nine cooking and storage pits of prehistoric people. A Leimbach cord-marked vessel from about 500 B.C. is believed to be from the Early Woodland period, long before the Whittlesey culture would have lived at the site.[11] Brian G. Redmond led another group during the summer, where more post molds, storage pits, and trash pits were found. One of the storage pits was a large hold for maize 5.4 by 5.1 ft, diameter and depth, respectively. They also found cooking features, many stone tools and pottery, and a partially subterranean sweat lodge. Animals butchered at the site include small game animals, raccoon, wild turkey, elk and deer. They fished for freshwater mollusk and fish in the Cuyahoga River. Two artifacts may have been used for ceremonial purposes. One was an engrave slate gorget, the other is the skull of dog, which had been drilled with 14 symmetrically-placed holes, cut and ground.

0 notes

Text

Kyidyl Does Archaeology - Part 3

(As before, parts 1 & 2 can be found via the KyidylCL tag.)

THE PITS

So, we’ve got the info about the site and we’ve got the prep work done, so what next? Digging! But archaeologists don’t just randomly dig, we dig in very precise ways. There’s, generally speaking, two ways to make a hole for an archaeologist (and this *doesn’t* apply to burials. Burials are done differently.): a pit and a trench. A pit is usually a specific size and meant to uncover a small area. A trench is a long area that takes a cross section of a specific area and is meant for exposing lots of area. When you’re doing a whole settlement often a trench is used because of the volume. We’re doing a mixture, and we started with two 5ftx5ft pits (~1.5 meters for the non-americans in the crowd. Good rule of thumb for ft --> meters is that 3ft = 1 yard = 1 meter, approximately. It’s not exact but if you’re trying to imagine how big something is, it’s a good way of thinking about it.).

Pit one only had 1 interesting thing and I don’t have any pictures of it really so I’m just gonna tell you about it real quick. In pit 1 we found a feature, which is a spot where the dirt is a different color in an unnatural shape because humans did something. This particular feature was a post hole from a palisade wall. That’s interesting for two reasons: 1, the natives didn’t build palisades until they came into conflict with the colonizers. It isn’t that they didn’t need defenses previous to that, it’s that the people they were defending against didn’t have horses or guns. Once the colonizers arrived, they started copying their method of defense. 2, palisade walls are made of large trees. To cut them down they were first burned in the place where the cut was made to make cutting them easier. And this means CHARCOAL.

Archaeologists love charcoal. We can date that shit really easily. And this particular charcoal was sent out for dating. Came back as 1700s, which makes sense for this area. It took the colonizers a bit longer to push up into the mountains, so the dates for contact and treaties and that kind of thing are later than official first contact in the 1400s. So that’s the latest date we have for the site.

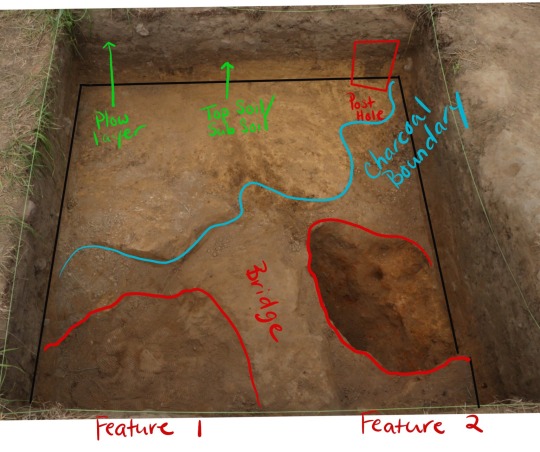

Now, pit 2. Pit 2 was, and still is, the most interesting pit on the site so far (we’ve opened a number of others, but it’s...lots of plow scars and jumbled artefacts.). Archaeologists, as I’ve mentioned, dig this kind of stuff in layers. So for our site (and I know a few of you following me are also archs, so I need you to know this was the site director’s choice not mine. >.<), we have a sod layer, layer 2 - the plow layer, and layer 3 the layer below the plow layer. General rule of thumb, at least the way I was taught is that you do it in increments or when the dirt changes color, whichever comes first. So layer 2 for us is pretty thick. Here’s what the pit looked like at the end of day 1 after we’d gotten the sod off and started bringing it down evenly:

The bucket is covering the test pit that’s at the center of it. The string is the boundaries of the pit, but also we attach what’s called a datum to it. A datum is a known spot above sea level that you use to make measurements as to how deep something is. It’s basically a string with a line level and you stretch it out until the line level reads, well, level...and then you use a ruler from there down to whatever depth you’re measuring. So when we find like...arrowheads and points and stuff (and this pit had several) we record where they were by saying “_____ inches BD”, or “below datum”.

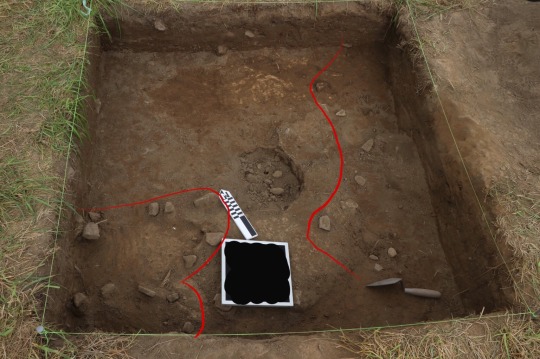

Anyway, you can see already where there are some rocks and differences in color of the dirt. It’s honestly not all that interesting but I figured you guys might like to see the progression. This is that same pit about 2-3 working days later, and this is where it started to get interesting:

Some of the difference in color there is because some soil is freshly exposed and some isn’t. The pit in the middle is the remains of the test pit. The lighter dirt at the bottom is sub-soil for this area, so it’s where the plow zone ends. The rocks may or may not have been added by people, so we record them just in case. How you deal with rocks depends entirely on where you are digging. In Florida, where I went to school, rocks are important because 99% of what they’ve got there is sand and shell. So if you find rocks they were probably put there by people. Here? Sometimes it’s just part of the ground and sometimes it’s people. It really depends on how far down you find them. This is about midway through the pit so it could go either way. So we do what’s called “pedestaling” where we dig around them and let them sit on a pedestal of dirt. You’ll see that in a lot of pics going forward. The reason that we’ve dug those upper corners differently is because we were starting to see soil color changes and we were investigating them separately. Good thing too, because they both turned out to be part of a large fire pit feature. Next slide!

So here you can see that the dirt in those two areas that we’ve dug is a distinctly different color - it’s reddish. Reddish dirt is a sign that the dirt has been heated, so we’re following the red dirt here. The digging changes from going in layers to following these features. And we’re really methodical about it so that we don’t remove too much or too little and lose the line of the feature. Here we were lucky, all the dirt inside those features was full of tiny specs of charcoal. And, in the upper left up there - which was my feature to dig - there were huge chunks of charcoal. Also a really nice piece of pottery. Well, I mean, comparatively. It’s still just a large sherd that I accidentally snapped in two while removing but like it counts. The square in the lower leftish is ust from like the foam I’d been sitting on. Getting into a pit - rather than digging it from the sides - is something you do NOT do without permission and a lot of care. Here, the ground is really solid so I wasn’t going to ruin anything by getting in there and the pit was getting too deep to effectively dig from the side, so I spent a lot of time in weird positions on the flat parts of this pit. So, anyway, here’s a close up of the feature so you can see what I mean about the charcoal:

Charcoal is very, very black so when you’re digging it stands out bc nothing else is that dark or that bright. Everything else is covered in dirt. But you can see it there in the top half - it’s those dark flecks and blobs. There was a ton of it, and when I say a ton, I mean we got I think almost 300g just that DAY. And y’all know how light charcoal is. This was the stuff we sent in for c14 testing along with the palisade charcoal and it came back, if I’m remembering right, mid-1300s. That’s a period called the late woodland. It matches up with the pottery and points we were finding, but I’ll get to that when I start in on the finds.

Now, I thought you might need some help with this next image so I brought it into procreate and drew on it. I know it looks like it came before the previous stage, but it didn’t. What happened is that we brought the whole pit down deeper to expose the edge of the large features. We also found a post hole in the process!

So I’ve marked the layers of dirt in the side wall for you so you can see what I mean when I’m talking about them. I’ve also marked out the bottom of the pit bc this angle made it a little hard to see. In the upper right you can clearly see the darker dirt of the post hole. A post hole is exactly what the name implies - someone dug a hole, stuck a post in it, and later the post was removed and filled with moar different dirt and now it’s a different color but in a distinctly unnatural shape. You can also see that we’ve long ago dug deeper than the test pit. The area I’ve marked “bridge” is an area of soil that didn’t have charcoal in it between the two pits that did. There was charcoal throughout that area - hence the blue boundary - but for the features themselves we were following the red dirt. And if that feature on the right looks deep to you it’s because it *is*. I dug it out and followed the charcoal and it went *under* the bridge.

Now you guys probably don’t realize this, but this is like...stupid deep to be finding this kind of stuff. We’re like 3ft below the surface here and still going down deeper. Around here the rate of topsoil accumulation is like...an inch every 600 years or so. The charcoal coming out of this pit is only 700 years old and it’s 3ft below the surface. So we’re likely looking at a hole that was dug by the natives for their own use. The thing that was confusing us was that we didn’t see the feature even start until we were almost at the bottom of the test pit so like...8 inches or so down. (about 16cm. 1inch is approx 2cm.) But then I was looking through some of my earlier images of the pit and I noticed this:

(north is the same direction in both pics)

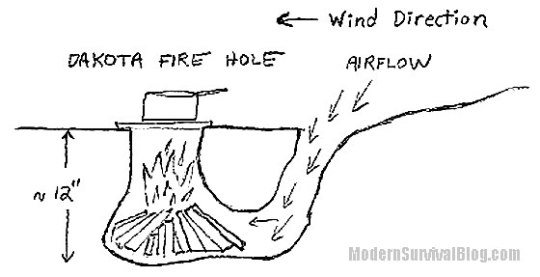

The rocks, the ones that could be either nature or people, approximately outlined the areas we’d found the fire pits. This is why you document shit. Even though this is still pretty deep to be finding this kind of thing, it at least makes more sense in the context of very disturbed site. So there might have been more evidence higher up, but it’s in the plow layer so we’ll never know. So what was the feature? Well, the two features were actually one feature (and you’ll have to wait till tomorrow’s post to find out how I know that.), and I think that might have been one of these:

(image credit)

Or something similar anyway, but I have to do more research about native cooking methods in this area of the country. But it would fit with the two holes and a bridge of dirt with no charcoal that we saw while digging.

Anyway I know this post is super long but I swear we’re almost done. When we finally finished digging the damned thing it looked like this:

(here I’m standing on the north side of the pit, so the top is the bottom in the other pics.)

We think that this might actually be part of another feature so it’s a little...ah...yeah it’s just weird. Those rocks were definitely from people, so maybe they were lining the bottom of the pit or something. If I could draw your attention to the black crud in the wall to the right of the pedestaled rocks, I’m gonna tell you one last story about this pit. That is a burned like...conglomerate of crud. It isn’t charcoal (charcoal is fuel for the fire, not what they were using the fire to make). Here’s what it looked like close up:

(aw yis macro lense)

See those circles? Those are *seeds*. I sent it to a former prof of mine who is an ethnobotanist for ID and she says she thinks it’s chenopodium AKA goosefoot, which was a staple food for the natives for a long time. One variety still is: quinoa. So basically, what we think we’re looking at is a 700 year old cooking accident. Or, as my professor put it:

So forgive the length, and I hope you all enjoyed this installment. =D

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seldom seen—archaeological textiles in the eastern United States

In my very first “Introduction to Anthropology” class, the professor, a cultural anthropologist, tried to steer us away from archaeology by telling us it was a childish pursuit for those who liked to play in the mud and hunt for treasure. That sounded like it was right up my alley. I ended up spending my summers and an internship term working in Plymouth, Massachusetts, doing historical archaeology. In addition, I also spent a lot of time in the collections of the college anthropology museum, found that I especially loved working with textiles and basketry, and eventually learned to weave both.

Working in the eastern United States, it’s hard to find archaeological textiles; the very world is against it. Acid soils and a temperate climate create conditions where little organic material survives to be studied, except in the rare instances of charred material or pieces in contact with copper, or still rarer, textiles deposited in dry caves. Even then the evidence is usually fragile and fragmentary.

What eastern archaeologists find is a lot of pottery, and luckily for us, much of it has been impressed with cordage or fabric. As part of the pottery making process, clay coils were consolidated by being beaten with a wooden paddle, a tool frequently wrapped with cordage or fabric. This technique may have initially developed to create decoration, but the resulting roughened surface also made for a better grip, and the increased surface area caused pots to heat quicker in cooking.

Archaeologists study the long-vanished textiles by making durable impressions of pottery surfaces with modeling clay or dental impression material. The information revealed through the thorough study of such impressions is not limited to the determination of just what type of cord or textile was used in making the original object.

The making of pottery impressions to look at textiles was first published by the pioneering archaeologist, W.H. Holmes, in “Prehistoric Textile Art of the Eastern United States”. Holmes started his scientific career as an illustrator, and included schematic drawings of the textile structures in his article.

Textile illustrations by Holmes.

When I worked at what is now the Florida Museum of Natural History, I got interested in the earliest pottery found in Florida, from what is known as the Orange culture. Dating from about 1500 BCE, these distinctive pieces were thick and very simply decorated. Their most interesting feature, at least to me, was that the clay pot bottoms had been pounded flat on matting, and the applied force made deep impressions. At least three different techniques were used, with variations and patterns within each, including several different matting materials.

Mat impressions from flat-bottomed pots, Tick Island, Volusia County, FL.

In one instance, a thick pot sherd had a smooth top surface, but a deep dent in the bottom; evidence the potter hadn’t removed a small pebble that was under the mat before the pot making.

Many studies have been done since W.H. Holmes, looking at such things as direction of the twist in cordage—a majority of right-handed or left-handed twist could indicate a culture-wide preference. Similar twist types in neighboring geographic areas might indicate related cultural or kin groups, while different twist types such areas could indicate a cultural boundary. The type of material used [soft fiber, hard rods, flat cane-like splints] may indicate cultural preference, or perhaps the materials available in the immediate environment.

One study by Dr Penelope Drooker, Mississippian Village Textiles at Wickliffe, introduced me both to some incredible textile impressions in pottery and the information that can be gleaned from them. Drooker’s work also analyzed and illustrated some textiles preserved in dry caves of eastern Tennessee, part of the Cherokee people’s ancestral lands. Among the materials she studied were skirts and bags from the Cliffty Creek Cave, artifacts now housed at the Smithsonian Institution. Working with the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in Cherokee, NC, I was able to re-introduce members of the tribe to one of the oldest weaving techniques of their ancestors. A few tribal members have visited the Smithsonian to photograph Cliffty Creek Cave pieces [as have I], and are now making skirts for use in festivals and pageants. Several are making decorated bags for their own use, and for sale.

Kara Martin McKinney wearing reproduction of Cliffty Creek Cave skirt, and reproduction woman’s feather cape. Image Credit: Scott McKie, reporter for the Cherokee One Feather weekly newspaper in Cherokee, NC.

One of the great things about textiles or pottery is that you could spend your entire life studying them, and still not learn all that these materials embody --techniques, cultural traditions, and art, all rolled into one. My grandfather, who kept his faculties up to his death in his mid-90s, said, “The day you stop learning is the day you start to die.” I try to live by that.

Deborah Harding is the Collection Manager of the Section of Anthropology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

References and further reading:

Drooker, Penelope Ballard 1992 Mississippian village textiles at Wickliffe, University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa and London

Holmes, W. H. 1896 “Prehistoric Textile Art of the Eastern United States” Thirteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1891–1892, Government Printing Office Washington, pages 3–46.

Milanich, Jerald T. and Charles H. Fairbanks 1980 Florida Archaeology Academic Press: New York

Petersen, James B [editor] 1996 A most indispensable art: native fiber industries from Eastern North America, University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville

http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/archaeology/native-american/early-middle-woodland-period.html

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The field school season is underway at Mini-Wakan State Park in Dickinson County! Students began working with State Archaeologist, John Doershuk, last week. So far they've found this Prairie Lakes Woodland impact-damaged arrow point, and a basal pottery sherd that measures 22 mm thick!

#iowa#archaeology#spirit lake#iowa state parks#field school#archaeological field school#excavation#field work#lithics#arrow point#arrowhead#stone tools#late woodland

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Artifact of the week: This unique ceramic sherd was found in Jersey County, IL by @CAAKampsville and depicts a figure with both bird and human features. It dates to the Late Woodland period (ca. AD 1000). #archaeology #pottery #museum #storyofillinois http://bit.ly/2vvDXHC

0 notes

Photo

Artifact of the week: This unique ceramic sherd was found in Jersey County, IL by @CAAKampsville and depicts a figure with both bird and human features. It dates to the Late Woodland period (ca. AD 1000). #archaeology #pottery #museum #storyofillinois http://bit.ly/2vvDXHC

0 notes

Text

Russell Cave National Monument - Bridgeport, AL

Our oldest son, Remiel, wants to visit every national park in the country. We’re off to a good start having gone to Rocky Mountain, Yellowstone, Grand Teton, Arches, Zion, Bryce Canyon, Grand Canyon, and Petrified Forest National Parks. All of those were visited on an epic one-month road trip in the summer of 2012. Since then, we’ve also visited Great Smoky Mountain and Shenandoah National Parks, and the Chickamauga and Shiloh National Battlefields.

During our last Thanksgiving break, we decided to take a day trip down to Russell Cave National Monument. It’s not too far from our home in Lynchburg, sitting on the Alabama side of the Alabama-Tennessee border near Bridgeport, AL.

Our day started with a journey to Manchester, TN to stop at the Cracker Barrell restaurant to have breakfast. After getting loaded up, we jumped on Interstate 24 and headed south towards Chattanooga, TN. Chattanooga wouldn't be our destination as we would jump off the interstate at the South Pittsburg exit and take US Highway 73 south towards Bridgeport. After several miles, we followed the signs from highway 72 to county road 75 and then county road 98 which lead us to the entrance of the national monument. This is a pretty southern rural drive passing small towns and mountains of the southern Appalachian range.

Upon entering the park, our first stop was the Grosvenor Visitor Center. Here we learned a little about the park and some of the history of the inhabitants of Russell Cave.

First, the park is open almost all year round from about 8:00 am to 4:30 pm. The exceptions are Christmas and New Year's Day. There is no entrance fee to Russell Cave and the facilities are rather bare. There is a picnic area, the Visitor's Center and some hiking trails. This is a small, fairly unassuming park, consisting only of 310 acres, so don't expect big. Russell Cave is also listed on the National Register of Historic places being placed there on October 15, 1966.

At the visitor's center, we learned a little about the history of the park and its inhabitants. The cave itself was cut out of limestone by a stream that travels within. About 9,000 to 12,000 years ago, the collapse of a cavern roof beneath a hillside created a sinkhole and exposed Russell Cave. The stream still runs through part of the cave, but due to the severe drought experienced in the Southeast during the fall of 2016, it was not flowing during our visit.

Russell Cave provides the most thorough records of prehistoric culture in the Southeast. Archaeological field surveys have uncovered the records of the cave's occupants. Around two tons of artifacts have been recovered from the site. These discoveries include charcoal from fires, bones of animals (as remains of hunted game and as bone tools), spear and arrow points, sherds of pottery, and the remains of several adults and children buried at the site. The bodies, ranging in age from infant to 50 years, were buried in shallow pits in the cave floor and were not accompanied by artifacts.

The first relics were discovered in 1953 when four members from the Tennessee Archeological Society began digging in the cave. This first excavation reached a depth of six feet. When they realized the extent and importance of the site, the team contacted the Smithsonian Institution which conducted three seasons (1956–1958) of archeological digs in cooperation with the National Geographic Society reaching a depth of more than 32 feet. An additional excavation was performed in 1962 by the National Park Service to a depth of 10.5 feet.

The evidence uncovered during the excavations indicated that human habitation of the cave began around 10,000 years ago. These earliest inhabitants were most likely hunter-gatherers and probably did not occupy the cave year round. With constant temperature and shelter from north winds, Russel Cave was probably a decent place to stay during the winters. During the Woodland Period (about 1000 BCE to 50 CE), the first signs of pottery and rudimentary agriculture were discovered. Even with these changes (from use of the atlatl to bows and arrows), Russell Cave was probably still just a winter camp for a small band of people.

After the Woodland period, use of the cave as a semi-permanent dwelling began to abate. There were few signs of long-term usage after the original inhabitants departed around 1000 CE. Cherokee Indians and European settlers no doubt used the cave occasionally, but the major use had ended.

Russell Cave was named after Colonel Thomas Russell, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War from North Carolina, who owned the property. The surrounding land called Doran's Cove is named after Major James Doran, the brother-in-law of Russell and the original owner of the land. The land was purchased by the National Geographic Society and donated to the American people. The area was designated as a National Monument in 1961 during the presidency of John F. Kennedy.

After spending some time at the Visitor's Center, we began the walk back to the Cave. The walkway is made up of a wooden boardwalk and is handicapped accessible.

The Cave is located at the base of a rather large mountain. The left side of the cave is where the stream would normally flow in wetter seasons, the right side of the cave is elevated and was used by the inhabitants as a living area.

Upon entering the cave proper, it was rather disappointing. Orange snow fencing is set up around some areas that are apparently in the process of excavation.

The living area of the cave is also surprisingly small. I doubt it would be able to hold more than two dozen inhabitants.

View from the cave mouth

After finishing the cave visit, we decided to take a stroll on some of the trails cut into the hillside above the cave. Our first stop was at a more recent sinkhole.

We continued our walk along the gentle trail until we found a good spot for some family pictures.

After picture time, Zachary was getting tired, so we decided to head back to the car and continue our day trip.

Remiel, on the other hand, was having a great time.

A few more pictures and we were back at the Visitor's Center.

Although the area is pretty and the cave unique, this was kind of a disappointing stop. Maybe coming back in the summer when there are more activities/staff might make a better stop. It was a pretty fall day in northern Alabama though.

If you want more information, you can visit Russell Cave's Facebook page or the National Park Service's web page.

via Blogger http://ift.tt/2jbCjmu

0 notes

Text

This intriguing feature was uncovered in 2009 during excavations in a former cultivated field in the Sand Lake Archaeological District near Onalaska. The soil within the feature was dark, like a storage or refuse pit, but the size and shape suggested it was something different--a semisubterranean, keyhole-shaped house. The feature measured about 5.4 by 3 meters (17.9 x 9.8 feet) and consisted of an oval main area and a “ramp” on the east side that extended to the north. It was 36 centimeters (just over 1 foot) deep. The dashed line shows the rough outline of the feature. Rodent disturbance had obscured part of the boundary.

Within the possible house, a deep basin-shaped feature along the west wall contained a small grit-tempered pottery sherd and two silicified sandstone flakes. Angelo Punctated and Madison Cord-Impressed pottery found within the house-like feature suggested a Late Woodland date, but few other artifacts were encountered as well. Some shell-tempered sherds were found at the top of the feature, but they might have come from a later, unrelated Oneota occupation. No postmolds were discovered in or around the feature, but if they were present, they could have been destroyed by a later occupation at the site or by plowing. A similar basin--possibly a winter house--related to the Late Woodland Effigy Mound culture was excavated in Vernon County in 1996. Link to Cade – Winter House Basin - https://www.uwlax.edu/mvac/past-cultures/specific-sites/site-snippets/?letter=c&term=248784.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Among the pottery sherds collected during a 1991 excavation at a Late Woodland habitation site in Oneida County, Wisconsin. Around a dozen pieces from two excavation units were refitted to form this partial vessel, which was interpreted as a possible Madison Cord Impressed variant. The lip top is scalloped, with a plain horizontal band beneath set off by cord impressions above and below. Underneath the band are alternating triangular and upside-down triangular panels with diagonal cord impressions followed below by a row of upside-down teardrop- to crescent-shaped punctates. Twelve other Madison Cord Impressed vessels were also identified. The pottery was thought to reflect a Lakes phase occupation dating to about AD 850-1200.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Woodland tradition pottery features a variety of designs incorporating stamps. These grit-tempered rims from a site in La Crosse County, Wisconsin, fall into a Middle Woodland type archaeologists call Naples Dentate Stamped. A notched tool, such as a carved stick, was pushed into the clay to create a pattern of shallow impressions. Because the tool had tooth-like notches, the stamp is called “dentate” (think “dental” or “dentist”). The sherd on the left has a row of stamp impressions near the rim made by a tool with one or more columns of notches. Below that is a row of circular punctates (holes from pushing a tool into but not completely through the clay) and then another row of stamps. The smaller sherd on the right shows similar stamping on the rim. This pottery was made about two thousand years ago.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pottery with collared rims, where the rim has been thickened to look as if a collar runs around it, is uncommon at Late Woodland sites in the La Crosse area. These three grit-tempered sherds from the Sand Lake Archaeological District near Onalaska have thickened rims that do not quite appear to be full collars, so the excavators called them “pseudo collared.” The pseudo collaring suggested that people in the area may have been experimenting with collaring techniques more common among groups in southeastern Wisconsin, north-central Illinois, and to a limited extent elsewhere in southwest Wisconsin.

For more information:

Boszhardt, Robert F.

2004 The Late Woodland and Middle Mississippian Component at the Iva Site (47Lc42), La Crosse County, Wisconsin, In the Driftless Area of the Upper Mississippi River Valley. The Minnesota Archaeologist 63:60–85.

Finney, Fred, and James Stoltman

1991 The Fred Edwards Site: A Case of Stirling Phase Culture Contact in Southwestern Wisconsin. In New Perspectives on Cahokia: Views from the Periphery, edited by James B. Stoltman, pp. 229–252. Monographs in World Archaeology No. 2. Prehistory Press, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kelly, John M.

2003 Delineating the Spatial and Temporal Boundaries of Late Woodland Collared Wares from Wisconsin and Illinois. Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee. https://www.academia.edu/460476/Delineating_the_spatial_and_temporal_boundaries_of_Late_Woodland_collared_wares_from_Wisconsin_and_Illinois

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thanks to Jim Theler for this week’s post –

A LATE WOODLAND (EFFIGY MOUND CULTURE) WINTER HOUSE BASIN: Keeping Warm in Frigid Winter

December 2022 brought a true winter blizzard propelled by the weather phenomenon known as a “bomb cyclone.” Below-zero air temperatures and sustained winds of 20-40 mph dropped wind chills to -40 F. Prolonged outdoor exposure was life threatening. Most of us were fortunate to be cocooned in warm dwellings with a predictable heat source and good winter attire. Even so, it was a frightening situation--and for some people, a fatal one. Especially for people in rural settings, in an emergency, help might or might not be on the way.

So how did people survive harsh Midwestern winters centuries ago? The Cade 5 site in Vernon County, Wisconsin, offers an intriguing possibility. The site is attributed to the Effigy Mound culture, an archaeological term for peoples who constructed a stunning array of animal/spirit-shaped burial mounds in western Wisconsin and surrounding areas during Late Woodland times, ca. A.D. 750-1050. Archaeological studies have provided insights into daily lifeways of Effigy Mound related peoples. There is good evidence that they were heavily invested in hunting and gathering wild plant and animal resources (wild rice, fish, and deer) harvested on a seasonal cycle across the landscape. Corn horticulture appears to have developed rather late during this time, and corn is thought to have been a lightly used supplemental resource.

Effigy Mound related peoples sometimes used south- or east-facing rockshelters during cool-season deer harvests and camped along rivers or lakes during the warm season. They probably built houses similar to a traditional Ho-Chunk house type called a ciiporoke (pronounced chee-POE-doe-kay). These rounded, wigwam-style structures, made of bent saplings covered with bark sheets or cattail mats, would have been suitable for a wide range of conditions. (For a photo of a ciparoke, see https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM64092.)

A house basin found in 1996 at the Cade 5 site (47Ve643) in Vernon Co., Wisconsin, raises another possibility for winter— a covered, semi-subterranean house that might have served as an emergency shelter during severe cold snaps. An apparent house basin (Feature 3) found beneath the disturbed plowzone soil was 11.5 by 13 feet in area and 30 inches deep. The bottom had fire-cracked rocks, a projectile point, and a few pottery sherds attributable to the Effigy Mound culture. Several feet away was a large hearth (Feature 1), partially excavated in 1995, that contained 600 pounds of burned limestone (dolomite) rock lying on a bed of oak charcoal. Radiocarbon samples dated both Features 1 and 3 to about AD 1000.

The excavator (Jim Theler) was initially unsure about purpose of the basin, but he now thinks it was a winter house for extreme cold weather. It might have had a flat or low dome covering. Hot rocks brought in from the outside hearth would have warmed the interior without the smoke produced by an interior fire. Similar “winter” houses of a “keyhole” design, with long, narrow entryways, were excavated at Late Woodland sites in Dane County, Wisconsin, by the Wisconsin Historical Society.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyidyl Does Archaeology - Part 5

(as per usual, all these posts are collected under the KyidylCL tag)

Pottery and shErds

So, what are we talking about today? Well, I think the next thing is gonna be pottery. This is where we’re gonna talk about time, space, and dating a site. Because most people think that the only way to date an archaeological site is via C14. That’s not true, and actually we don’t always do it. C14 dating can have some problems, including that the wood used in the fire is likely older than the time in which it was cut down and burned. It also only goes back 50,000 years, so anything older than that won’t have any carbon isotopes (it’ll have all decayed), and we have to use other things that are more expensive. And c14 testing itself is expensive - we sent in 2 samples and it was around $500/sample so we spent about $1000 on testing. Instead, there are other ways to date a site and one of the most accurate is pottery.

See, like all other kinds of material culture (AKA, stuff people leave behind. Non-material culture is like...song and story and stuff like that.), pottery follows stylistic trends and trends in how it was made. And it does this both regionally and chronologically. Which is great, because if we find bits of one type of pottery we know is made in one place in a settlement in another place, then we know the two people traded with each other. But I have to explain something else so that determining a date from pottery makes sense.

Every area of the country has what’s called a “type site” for a given period of time. In undergrad I was lucky enough to actually get to work on the type site for the Safety Harbour period, which is Weedon Island....ironically enough there’s a Weedon Island period and Weedon Island isn’t the type site for that period so uuuhhh...yeah it’s weird lol. Anyway, a type site is a site that is considered stereotypical for a given time and place in history. Usually they’re large and well-preserved, and they’re often the first sites found in that time period/area (but not always, which is how the above weirdness happened.). And so what happens is we dig ‘em and analyze the finds and do testing on those finds. So now we know “hey, this kind of pottery comes from here and it is X years old”. Now you know when you find it in other places where and when it comes from. This is all a very generalized explanation, but I think any more is like extraneous detail you don’t need. Just know that things like type sites help us determine where and when stuff like pottery was made. Lots of literature usually exists for type sites, but I actually can’t remember the type site for this area for this time period.

We also use a term called “diagnostic”, which is used much as it is in medicine. If we find a certain thing that was only made during a specific time period or in a certain place, then it’s diagnostic. IE, a certain kind of pottery is diagnostic of the late, middle, or early Woodland. The pottery we have at our site is diagnostic of the late Woodland. Some of the lithics we thought might be a bit earlier, but honestly I think that was just misidentification by the site director bc we were in the field at the time. Lastly, identifying pottery has a few components. Color and decoration I think are easy to understand (they didn’t have glazes, but you can make different colored pottery by varying the composition of the clay and the temperature at which it is fired.). Paste and temper are the other two. IDK how modern pottery is made, but old ass pottery is made with paste - the main body of the clay, the matrix that contains the temper - and temper. Temper is stuff they’d crush up and mix in to help it not break during firing and heating during normal use. So we combine these factors to ID the pottery and thus the age of the site and trading habits of the people in question. One last thing you need to understand about pottery - ancient people used pottery the way that we use disposable things. They didn’t think it was like an important thing that had to keep safe. They’d use it until it broke and then toss it in the garbage pit and make a new one. So it’s really common and we find it all over the place, but TBH in the future pottery *won’t* be diagnostic anymore because our ceramics come in such a wide variety that we couldn’t possibly hope to narrow down time or place.

Alright, so who wants pictures? You, of course. Who *doesn’t* want pictures? Here’s some of the pottery we found:

This is the larger shard that I found in the features I’ve talked about in previous installments. You can see where I accidentally broke it. >.> Anyway it’s kind of unique bc of the light color outside and the black inside. It’s like...idk, 4 or so inches long.

This is a rim piece that I happened to find two matching sherds of. I always check the rim pieces because the patterns on them usually make them easier to fit together. Honestly I’ve got hundreds of pot sherds from this site and I don’t have the sanity to try and make pots from them.

This is the outside and inside respectively of the largest piece we have. TBH taking this thing out of its box and handling it makes me nervous because of how large it is - about the size of my hand, but I did include my earbuds for scale. The black is charring from both firing and subsequent use, and it came out of the pit feature I’ve been talking about. And do you wanna know the cool thing about the inner surface of pottery? Because they didn’t use glazes, the surface was porous and retains the unique chemical traces of what was made in them. However, the vast majority of the time those kinds of tests aren’t done because archaeology as a whole is extremely underfunded and trace chemical analysis of pot residue is an expensive test requiring expensive equipment and expensive scientists. Funnily enough I probably could do some of this testing bc I used to be premed and so I’ve taken a lot of chemistry and know how to read a mass spec thing, but I don’t have access to the chemicals or tools to do these kinds of tests. Plus, they’re often destructive...which....I mean...there’s so much pottery that it doesn’t really matter if one piece gets destroyed but like you do still have to be careful *which* piece you destroy.

Anyway, you also can see the striations on the outside piece, and that’s decoration on the pot. It probably also helped with gripping it. This is a piece of Shepardware, which is diagnostic of the late Woodland period in the Shenandoah valley. Here’s some more cool pottery:

This is a random assortment of the kind of stuff we regularly pull out of the ground when it comes to pottery. The most common kind we have is the orange on one side black on the other (3 upper rt pieces), whiteish (upper left 2), orange on both sides (lower left 3) and totally black (lower right 3). All of ‘em are some variety of shepard or pageware. You can see the texture on a lot of them, too. We have a good mix of textured and untextured, and that’s why the composition of the pottery is more diagnostic than the decoration. Frankly, people can and will put whatever design they think looks cool. But they made that particular design by wrapping twine around the end of a flat stick and pressing it into the surface of the wet clay. I also chose those two upper right pieces because they have really visible temper. Here’s a side shot of one of them:

You can see how big the bits are compared to my fingers (yeah, there’s dirt under my nails....I haven’t taken some tweezers to them yet after working on the car.). And...wait, I WAS going to try to describe this to you but then I was like “no, they deserve better” and I broke out my DSLR and my macro lens and took some pics. Here are some macros of the temper:

The white balance is a little off on the top one...the bottom one is more true to color (they aren’t the same piece of pottery, but they are a similar color). So you can see that it’s crushed up limestone. Pardon the depth of field on those...I had to open the aperture pretty wide to get one that wasn’t blurry bc I don’t exactly have bright lights in my room.

Anyway....so that’s the pottery we’ve gotten at the site and what we can learn from it. It’s going to take some time before we can start determining patterns and whatnot in regards to style, but we do have some evidence of trading here because some of the pottery we have is from the piedmont culture....

...wait, let me explain what that means. When archaeologists need to describe a group of people who existed in a given place in a given time based on similarities in material culture regardless of ethnic and social grouping we call it a culture. This is different than the standard meaning of the world culture, or even the way a cultural anthropologist would use the word. So when I say the piedmont culture, I mean people that lived in the general area of the Piedmont plateau during the late woodland. They were of varying tribes, languages, etc. And we do this to describe the extant boundaries of cultural influence of particular trends in physical objects and not the social groupings of the humans in question. So, for example, lots of people are familiar with the Clovis culture. When archaeologists use this term we mean “these are the boundaries of the places we are finding physical objects in the group we’ve named Clovis” not “everyone in this area was a Clovis person”. Like no, obviously, they weren’t. There were tons of social groups, tribes, etc. that were all distinct and different. It’s a way of mapping cultural influence via physical objects to see how far they spread and who was using them.

So, we have some piedmont stuff despite not being in the piedmont area, so we know that they were trading with those natives. If you’re interested in more detail here, this is the VDHR resource I use for IDing pottery. It looks like it came to visit you from the late 1990s, but the info is good and it’s easy to use.

Anyway, that’s it for tonight. Tomorrow is gonna be rocks and weird stuff, depending on how much I end up saying about rocks. Probably not much bc we know how I feel about rocks. ;)

46 notes

·

View notes