#Which are all derived from imperialism in the global south

Text

You might ask, why?

Why this blog? Why these images? Why Japan?

I recently began attending Antioch College in Yellow Springs for a variety of reasons, but prime among them was the ability to go places and do things. They call it cooperative education. I call it the ability to experience life. This is the reflections from my first co-op trip, in which I've finally managed to get to Japan. The Land of the Rising Sun. The derivation not only of my favorite anime and video games, but also a place with a spirituality that resonates with my own. This blog, beyond being something that I already want to do, also serves as a record and journal of my experiences.

I am currently at Yamasa in Okazaki, working on learning some amount of Japanese to become more fluent and able to speak in it... somewhat. I'm only there for three weeks, and honestly I don't think it's going to take me to the fluency level that I'd like. Thankfully, we live in a world with Google Translate! After that, there's a WorkAway that I will be doing just south of Tokyo in Yokosuka involving assisting with a house renovation that is currently in the plans. After? I don't exactly know.

While in Yokosuka, I'm hoping to spend at least a day (if not more!) in Akihabara, being the global cultural center for all things otaku. Later, I would like to spend a couple weeks in Nara to learn more about the early history of Japan, then head to Kyoto for a week to visit the famous Kyoto Imperial Palace among countless other famous sites and shrines; later I would like to spend a weekend in Shirakawa which is both a UNESCO World Heritage Site as well as the setting for Higurashi no Naku Koro ni (which happens to be one of my favorite anime). If time and money permits, I have a bucket list of other places that I would love to check out - including, but not limited to, Shiretoko National Park, Ikeshima & Gunkanjima, Aokigahara, the Ise Grand Shrine... That said, the lack of a JR Rail pass puts a damper on those plans... for now, anyway. I'm hoping, once the next round of student loan money comes in, that I'll be able to afford one (or at least a trip on a shinkansen!)

One of my goals that will definitely require more work on my part is to become fluent enough in Japanese to work as a translator. For whom and on what is still to be decided, but I adore all things anime, manga, video games, and so on from here so the possibilities are pretty wide open.

I'm hoping that the collection of entries in this journal will suffice for my "Signature Assignment" for the course side of this expedition. If not, I'll update you soon on whatever plans may change!

Until next time~

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historical thread: from Manifest Destiny to today's global strife.

James Monroe gave a State of the Union address on December 2nd, 1823. Buried within it, was a warning to the powers of Europe; that any further expansion in the Americas might be perceived as an act of hostility.

By the late 19th century, the Monroe Doctrine combined with the rise of the concept of Manifest Destiny, gave the perfect combination for American expansion westward towards, and into the Pacific.

Monroe was the last "founding father" to serve as president. He attended the College of William and Mary, fought in the Continental Army, and practiced law in Virginia. He was an anti-federalist - a group involved in ratifying the U.S. Constitution. Furthermore, he served as minister to France from 1794 to 1796. He was also, partly responsible for the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

America started as groups of various European settlements whose affluent organized to create an independent, monarch-free empire. A monarchy of the rich with an illusion of public equality.

This was at a time when Europe was grappling with what powers their monarchs should have.

They originated as feudal systems in medieval times in Europe that developed from the mass enslavement of the poor in proto-capitalist societies.

The economic systems we live under today, if you live in the Western world, or a place under Western spheres of influence, derive from those systems.

In the 19th century, the Europeans and Americans could not allow for systems that existed outside capitalist control. The idea that people did not serve a state power, a monarch, or the various forms of landlords/capital owners, was unsettling and a threat to their legitimacy.

During colonial times, Guatemala was an administrative center in the Central American region. Today, it remains a religious center. Monroe-ism had a hand in eradicating most European control in that region. And instead imposing U.S. influence.

The influence is most pronounced in the Panama region, where the dollar is the current currency.

While the impact of Spanish, Portuguese, and other European conquest in Central and South America is still felt today, the current hand of the local conquistador, the U.S.A., is most today.

For the past 200 years, U.S. intervention in Latin America has become second nature. If a government in that region does something that the U.S. does not like, then that is grounds for a U.S.-backed coup, destabilization of government and society, and re-appointment of more U.S. corporate interest-friendly persons in the place of anyone the U.S. does not like. This started to translate elsewhere after Wilson took power. Like in the Koreas, Iraq (where the U.S. supported Saddam until they didn't) Israel, the GCC, Iran, heck even the Soviet Union and post-Soviet states - namely Yugoslavia.

Moral consistency be damned, you have to protect your foreign interests and ensure access to other people's natural resources! Right?

Nowadays, the times of Monroe and other early presidents are incredibly romanticized by U.S. Americans. Forgetting his actions towards Native Americans, and his presiding over the trail of tears.

This is not unlike the modern-day treatment of occupied indigenous populations elsewhere. But hey, white culture is better than any other, right? (Wrong, it isn't, it never was, it never will be.)

Looking at Palestine today, you can see where this amalgamation of Monroe-ism, Wilsonianism, post-modern imperialism and colonialism collide. And it all goes down to this white supremacist belief that their culture and way of life is best, which is infantilistic at best and narcissistic at worst.

Winston Churchill himself said of the colonization of Palestine;

"I do not admit that the dog in the manger has the final right to the manger, though he may have lain there for a very long time I do not admit that right. I do not admit for instance that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been to those people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race or at any rate a more worldly-wise race, to put it that way, has come in and taken their place. I do not admit it. I do not think the Red Indians had any right to say, 'American continent belongs to us and we are not going to have any of these European settlers coming in here'. They had not the right, nor had they the power."

Decades after the Monroe Doctrine State of the Union, Theodore Roosevelt used the Monroe Doctrine as a way to legitimize America's "international police power" around the world. And if we ask KRS-One about the police, they are an extension of the upkeep of white supremacy in the United States. According to Roosevelt, the Monroe Doctrine was a way for the U.S. to expand their overseer officers across the globe.

Roosevelt's antics in Venezuela, reflect the ideals of today's American government. Telling Henry Cabot Lodge, "I rather hope the fight will come soon. The clamor of the peace faction has convinced me that this country needs a war."

Today, Joe Biden, like most all presidents before, is keeping up this power. Protecting their interests everywhere at the expense of everyone else. As we see in the carte blanche given to Israel by its imperial benefactors to do whatever it wants, whenever it wants, to whomever it wants. Including committing genocide, enacting apartheid, controlling the world's largest concentration camp, and arresting 100s of children annually - without charge or judicial oversight - in military prisons, in a country that has become a safe haven for pedophiles according to its own media, amongst incalculable and unimaginable atrocities occurring daily against Palestinians across the territories.

This brings us to China and the Soviet Union, both of these nations are/were economic rivals of the U.S. The former two gaining power on the global stage is not good news for U.S. global control, as they provide alternatives to anything the U.S. can do, and it would be a great danger to U.S. and European satellite stateless, like Israel.

Cuba, being the antithesis of an American satellite state, remains a thorn in the side of U.S. foreign policy. A state, in its own 'sphere of influence', that isn't attached to the U.S. economically and socially? Worse, economically tied to the Soviets? What?!?!

Hell, the Monroe Doctrine was at the root of J.F. Kennedy's response during the 'Cuban Missile Crisis'.

And before you start to list the 'atrocities' of the Cuban state, I wish to redirect you to the concept of moral consistency! Look it up.

This is a catch-22 for both the U.S. and Israel. They both have internal issues that are bringing their power down on the global stage, and American support of Israel brings its power and influence down even further. Its power going down brings Israeli support down.

The final goal of anti-Monroe-vian visionaries should be to take away the veto powers of all who hold them on the UNSC, taking away any carte blanche powers that any state can hold, and the demand of moral consistency from all.

The Monroe Doctrine started out as a way to prevent European involvement in the Americas to ensure U.S. American economic influence in the Western Hemisphere. Later on, expanding that hemisphere to wherever natural resources and economic pathways may lay.

This motivated Europe to expedite the process of expanding east and south. A process that has been in the works, but it definitely allowed for more capability, time, and focus to be applied there than in the potential of expanding into the western hemisphere.

In today's world, Europe's colonial modus operandi is to settle its people elsewhere. While the U.S. modus is imposing a military and cultural presence that sought to command people's loyalties to what it saw as the moral high ground. Manifesting what once was titled the "white man's burden" - or in today's social power structure the "western-capitalist man's burden."

#palestine#manifest destiny#U.S. dimplomacy#israel#joe biden#genocide#united nations#gaza#politics#apartheid#israel palestine conflict#Monroe Doctrine#American Expansion#Manifest Destiny#Imperialism#US Foreign Policy#Global Politics#Colonial Legacy#Monroeism#Latin America#US Intervention#Western Capitalism#Modern Imperialism#Global Power Dynamics#American Empire#Global Influence

1 note

·

View note

Text

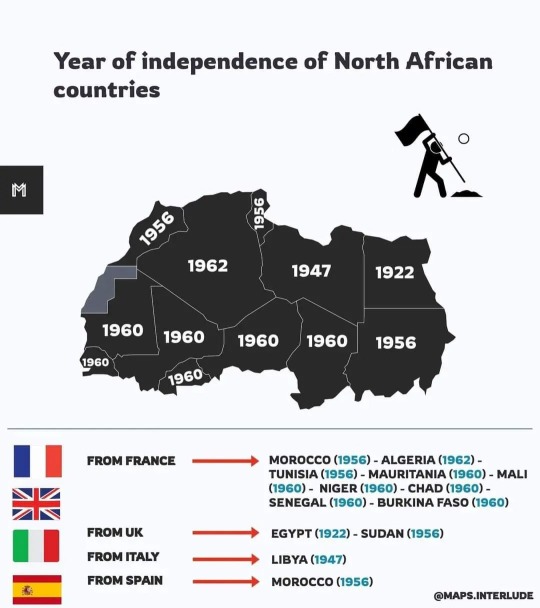

Year of independence of North African countries with map

Year of independence of North African countries

During the 1950s and 1960s, and into the 1970s, all of the North African states gained independence from their colonial European rulers, except for a few small Spanish colonies on the far northern tip of Morocco, and parts of the Sahara region, which went from Spanish to Moroccan rule.

According to study.com, these countries were, in chronological order of independence: Cameroon, Togo, Madagascar, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, Benin, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Chad, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Senegal, Mali, Nigeria, and Mauritania. Ghana was one of the first nations in the African continent to gain independence from colonial rule.

The year 1960 is known as the “Year of Africa,” when 17 countries across the continent celebrated the joy, excitement, and possibilities of independence. But liberation in Africa was more than this one moment in the global process of decolonization. Between March 1957, when Ghana declared independence from Great Britain, and July 1962, when Algeria wrested independence from France after a bloody war, 24 African nations freed themselves from their former colonial masters. In most former English and French colonies, independence came relatively peacefully.

Namibia became the world's newest nation when South Africa formally relinquished control shortly after midnight today (5 p.m. EST Tuesday). So ended an era of colonial rule on a continent once carved up and ruled by European powers hungry for imperial glory.

By 1914, the only independent African states were Liberia and Ethiopia. The area of West Africa that is now called the Democratic Republic of Congo is a good example of what happened to many African countries during the Scramble for Africa.

The West African country of Liberia shares special historical ties to the United States, dating back to its founding in 1822 by former slaves and free-born blacks from the United States under the sponsorship of the American Colonization Society (ACS). The Dutch established a colony in Africa before many other European countries. It is also the first colonial country which came to South Africa.

Why was Africa called Ethiopia?

Ethiopia derives from the classical Greek for “burnt-face” (possibly in contrast to the lighter-skinned inhabitants of Libya). It first appears in Homer's Iliad and was used by the historian Herodotus to denote those areas of Africa south of the Sahara part of the “Ecumene” (i.e. the inhabitable world).

Who named Africa? the Romans

All historians agree that it was the Roman use of the term 'Africa' for parts of Tunisia and Northern Algeria which ultimately, almost 2000 years later, gave the continent its name. There is, however, no consensus amongst scholars as to why the Romans decided to call these provinces 'Africa'.

Which country was not colonized in Africa?

Battle of Adowa (Ethiopia) As you have already learned, Ethiopia along with Liberia, were the only African countries that were not colonized by Europeans.

What are the 7 European countries that colonized Africa?

By 1900 a significant part of Africa had been colonized by mainly seven European powers—Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, and Italy. After the conquest of African decentralized and centralized states, the European powers set about establishing colonial state systems.

Most nations in Africa were colonized by European states in the early modern era, including a burst of colonization in the Scramble for Africa from 1880 to 1900. But this condition was reversed over the course of the next century by independence movements. Here are the dates of independence for African nations.

CountryIndependence DatePrior ruling countryLiberia, Republic ofJuly 26, 1847-South Africa, Republic ofMay 31, 1910BritainEgypt, Arab Republic ofFeb. 28, 1922BritainEthiopia, People's Democratic Republic ofMay 5, 1941ItalyLibya (Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya)Dec. 24, 1951BritainSudan, Democratic Republic ofJan. 1, 1956Britain/EgyptMorocco, Kingdom ofMarch 2, 1956FranceTunisia, Republic ofMarch 20, 1956FranceMorocco (Spanish Northern Zone, Marruecos)April 7, 1956SpainMorocco (International Zone, Tangiers)Oct. 29, 1956-Ghana, Republic ofMarch 6, 1957BritainMorocco (Spanish Southern Zone, Marruecos)April 27, 1958SpainGuinea, Republic ofOct. 2, 1958FranceCameroon, Republic ofJan. 1 1960FranceSenegal, Republic ofApril 4, 1960FranceTogo, Republic ofApril 27, 1960FranceMali, Republic ofSept. 22, 1960FranceMadagascar, Democratic Republic ofJune 26, 1960FranceCongo (Kinshasa), Democratic Republic of theJune 30, 1960BelgiumSomalia, Democratic Republic ofJuly 1, 1960BritainBenin, Republic ofAug. 1, 1960FranceNiger, Republic ofAug. 3, 1960FranceBurkina Faso, Popular Democratic Republic ofAug. 5, 1960FranceCôte d'Ivoire, Republic of (Ivory Coast)Aug. 7, 1960FranceChad, Republic ofAug. 11, 1960FranceCentral African RepublicAug. 13, 1960FranceCongo (Brazzaville), Republic of theAug. 15, 1960FranceGabon, Republic ofAug. 16, 1960FranceNigeria, Federal Republic ofOct. 1, 1960BritainMauritania, Islamic Republic ofNov. 28, 1960FranceSierra Leone, Republic ofApr. 27, 1961BritainNigeria (British Cameroon North)June 1, 1961BritainCameroon(British Cameroon South)Oct. 1, 1961BritainTanzania, United Republic ofDec. 9, 1961BritainBurundi, Republic ofJuly 1, 1962BelgiumRwanda, Republic ofJuly 1, 1962BelgiumAlgeria, Democratic and Popular Republic ofJuly 3, 1962FranceUganda, Republic ofOct. 9, 1962BritainKenya, Republic ofDec. 12, 1963BritainMalawi, Republic ofJuly 6, 1964BritainZambia, Republic ofOct. 24, 1964BritainGambia, Republic of TheFeb. 18, 1965BritainBotswana, Republic ofSept. 30, 1966BritainLesotho, Kingdom ofOct. 4, 1966BritainMauritius, State ofMarch 12, 1968BritainSwaziland, Kingdom ofSept. 6, 1968BritainEquatorial Guinea, Republic ofOct. 12, 1968SpainMorocco (Ifni)June 30, 1969SpainGuinea-Bissau, Republic ofSept. 24, 1973 (alt. Sept. 10, 1974)PortugalMozambique, Republic ofJune 25. 1975PortugalCape Verde, Republic ofJuly 5, 1975PortugalComoros, Federal Islamic Republic of theJuly 6, 1975FranceSão Tomé and Principe, Democratic Republic ofJuly 12, 1975PortugalAngola, People's Republic ofNov. 11, 1975PortugalWestern SaharaFeb. 28, 1976SpainSeychelles, Republic ofJune 29, 1976BritainDjibouti, Republic ofJune 27, 1977FranceZimbabwe, Republic ofApril 18, 1980BritainNamibia, Republic ofMarch 21, 1990South AfricaEritrea, State ofMay 24, 1993EthiopiaSouth Sudan, Republic ofJuly 9, 2011Republic of the Sudan

Notes:

- Ethiopia is usually considered to have never been colonized, but following the invasion by Italy in 1935-36 Italian settlers arrived. Emperor Haile Selassie was deposed and went into exile in the UK. He regained his throne on 5 May 1941 when he re-entered Addis Ababa with his troops. Italian resistance was not completely overcome until 27th November 1941.

- Guinea-Bissau made a Unilateral Declaration of Independence on Sept. 24, 1973, now considered as Independence Day. However, independence was only recognized by Portugal on 10 September 1974 as a result of the Algiers Accord of Aug. 26, 1974.

- Western Sahara was immediately seized by Morocco, a move contested by Polisario (Popular Front for the Liberation of the Saguia el Hamra and Rio del Oro).

Read the full article

#AreanycountriesinAfricastillcolonized?#HowlongdidBritaincontrolAfrica?#HowmanyAfricancountriesachievedindependenceintheYearofAfrica?#HowmanyAfricancountriesareindependent?#HowmanyAfricancountriesdidtheBritishcolonized?#HowmanyAfricannationswereindependentbytheendofthe1960s?#What17Africancountriesgainedtheirindependencein1960?#What2Africanstatesremainedindependentandhow?#Whatarethe7EuropeancountriesthatcolonizedAfrica?#WhatcountrieskepttheirindependenceinAfricaby1914?#WhattwoAfricancountriesweretheonlycountriestokeeptheirindependence?#WhatwasSouthAfricacalledbefore1961?#WhatwasthefirstNorthAfricancountrytogainindependence?#WhatwasthelastcountryinAfricatogainindependence?#WhatwerethetwoindependentAfricancountriesin1913?#Whatyeardid17Africancountriesbecomeindependent?#WhendidAfricancountriesgainindependencefromBritain?#WhendidnorthernAfricagainindependence?#WhichAfricancountriesgainedindependencein1961?#WhichAfricancountrygainedindependencein1964?#WhichAfricannationsbecameindependentafter1965?#WhichcountrywasfirstcolonizedinAfrica?#WhichcountrywasnotcolonizedinAfrica?#Whichisthefirstcountrytogainindependence?#WhichthreeAfricancountriesgainedindependence?#WhonamedAfrica?#WhoownedmostofAfricain1914?#WhydidBritaingiveupAfrica?#Whyis1960calledtheYearofAfrica?#WhywasAfricacalledEthiopia?

0 notes

Text

Most of these people seem to understand white privilege doesn’t function through the action of individual white people going out and deliberately individually oppressing people of color with every action they take. They understand it’s a function of white people being given structurally more opportunities than people of color and being made out to be structurally more important than the people of color the government had historically exploited and continues to exploit. The same is true of US residents and countries in the global south. Idk why this is such a hard concept to grasp

#logxx#''How does a black person living in the US or spending US currency harm non-US residents'' I mean strictly speaking it doesn't#But every piece of modern American wealth was made off the exploitation of people in the global south#Ofc it was made off the exploitation of people of color and particularly black people within the US as well#But that doesn't negate the truth that there is no way to live as a US resident w out profiting off of slavery/imperialism#In the global south#That's not a moral quality! That's not something anyone chooses!#It's simply a fact of the world we live in#That American currency is worth so much and that English be such a treasured language is in itself evident of that#And while America's system does exist largely to oppress people of color and Black people in particular#That doesn't erase the structural features that define American infrastructure which every US resident interacts w#Which are all derived from imperialism in the global south

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Sir Francis Drake:

The Elizabethan sea captain, privateer and navigator, temains of course a figure of global fame, particularly in connection with the 1588 defeat of the Spanish Armada His connection with Devon is also well known, but less well known is his legendary status as a powerful magician, witch, and leader of Devonshire covens.

In c. 1540, Sir Francis Drake was born in the west Devon town of Tavistock. In 1580 he purchased Buckland Abbey, a seven hundred near Yelverton on the south-western edge of Dartmoor. Anyone who was seen to have made great achievements and remarkable feats, in the days when witchcraft was widely believed in, was likely to have their successes put down to magic, and some form of pact with spirits. Such was certainly the case with Drake, who was said to have sold his soul to the Devil in exchange for victory and success, and there are numerous tales and traditions of his magical powers and his working relationship with the spirit world. One such tale concerns his alterations to Buckland Abbey.

During the building work, the workmen would down their tools at the end of the day, only to return in the morning to find the previous day's work undone and interference from the spirit world was suspected. Drake decided to find out for himself what was happening and that he would spy on the culprits. As night fell, he climbed a great old tree overlooking the house, and waited. When midnight came, out of the darkness emerged a horde of marauding demons, gleefully clambering about over the house and dismantling all the stonework put up during year old manor house the day.

Loudly, Drake called out 'Cock-a-doodle-do!" in the manner of a cockerel, crowing in the dawn. The mischievous spirits suddenly stopped their shenanigans in confusion, and Drake lit up his smoking pipe. As they spotted the glowing light in the tree, the spirits believed the sun was coming up and departed back into the shadows from whence they came. Presumably, they were so embarrassed at having been so easily fooled that they never returned, and the building work continued unhindered.

Traditionally housed in Buckland Abbey, is Drake's legendary drum. Beautifully painted and decorated with ornate stud-work, the drum is popularly said to have accompanied sir Francis Drake on his voyages around the world. As he lay on his deathbed on his final voyage, it is said Drake ordered that his drum be returned to England and kept at Buckland Abbey, his home. Here, the drum should be beaten in times of national threat, and it will call forth his spirit to aid the country. Indeed, there have been numerous occasions when people have claimed to have heard Drake's drum beating, including during the English Civil War and the outbreak of the Frist World War.

In 1918, a celebratory drum roll was reported to have been heard aboard the HMS Royal Oak following the surrender of the Imperial German Navy. An investigation was carried out with the ship being thoroughly searched twice by officers and again by the captain. As neither a drum nor a drummer could be found, the matter was put down to Drake's legendary drum.

During World War II, much weight was added to the drum's legendary protective influence, particularly over the city of Plymouth which, it was said, would fall if the drum was ever removed from its home at the Abbey. When fire broke out at Buckland Abbey in 1938, the drum was removed to the safety of Buckfast Abbey.

Bombs first fell on Plymouth 1940, and again in 1941 in five raids which reduced much of the city to rubble. In 1172 civilians lost their lives in the 'Plymouth Blitz’. Drake's drum was returned to Buckland Abbey, and the City remained safe for the remainder of the war.

Like many reputed witches and magicians, Sir Francis Drake was said to possess a familiar spirit to aid him in his work. The presence and influence of this spirit turns up in the stories surrounding his marriage in Like 1585 to Elizabeth Sydenham, daughter of Sir George Sydenham the Sheriff of Somerset. Some sources that Elizabeth's parents we disapproving of the union due to Drake's reputed involvement in the black artes and that the marriage took place shortly before he departed for a long voyage. After no news had been heard from Drake for a number of years, Elizabeth's parents took the opportunity to persuade her to declare herself a widow. Another account states that Drake's departure for his voyage took place before the wedding. In both versions however, The Sydenhams arranged for their only child to be married instead to a wealthy son of the Wyndham family.

It is said that Drake had left his familiar spirit to keep watch over his beloved while he was away, and that the spirit made him aware of her planned wedding to another man. On the day of the wedding, there was a loud clap of thunder, and a meteorite came crashing through the roof of the church. Some said that this had been a cannonball shot from Drake's ship to halt the wedding. In any case, it was taken as a bad omen against the wedding between Elizabeth Sydenham and the son of the Wyndham family.

The meteorite itself, known as ‘Drake's Cannonball' has been housed at Combe Sydenham ever since.

Another popular legend featuring Drake's reputed and remarkable magical abilities concerns the creation of the Plymouth Leat. As Plymouth had suffered problematic water shortages through dry summer months, it is said that Drake took his horse and rode out onto Dartmoor to search for a water source. Upon finding a small spring, he uttered a magical charm over it and it burst forth from the rocks as a flowing stream. Drake galloped o on his steed, commanding the flowing waters has he die so to follow him back to the city. Today, the Plymouth Leat has its beginning at Sheepstor on the western side of Dartmoor and ends in a reservoir just outside the city.

There are, of course, a number of traditions of magic and witchery surrounding Sir Francis Drake's defeat of the Spanish Armada. He is said to have presided as Man in Black' over a number of covens, and that during the threat of invasion, he and his covens assembled on the cliffs at Devil's Point to the south west of Plymouth. There they performed magical operations to conjure forth a terrible storm to destroy many of the Spanish ships. It is said that to this day that Devil's Point is haunted by Drake and his witches, still convening there in spirit form.

Another, more famous legend, tells of Sir Francis Drake playing a game of bowls on Plymouth Hoe when news was brought to him of the approach of the Spanish fleet. In one version he is said to have casually continued his game to its conclusion which, it has been suggested was a magical spell; with the bowls he was scattering with his drives representing the invading fleet. In another version, he stops his game to order a hatchet and a great log to be brought to the Hoe. He then proceeded to chop the wood into small wedges whilst uttering a magical charm over them as each one was thrown into the sea, and as each one hit the water they transformed into great fire ships; sailing out to burn the Armada.

The folklore surrounding Sir Francis Drake also includes his deep association with the Wild Hunt. Sometimes he is seen as leading the ghostly pack of Wisht Hounds', and at others he is the riding companion of the Hunt's more traditional leader; the Devil. In some Stories Drake rides in a spectral black coach, drawn by black, headless horses and followed by a great pack of black, otherworldly hounds with eyes burning red in the night. Sometimes his coach horses are seen with their heads, and have eyes blazing like hot coals.

One such story tells of a young maid, running desperately across the moors to escape an evil man on horseback she is being forced by her adoptive family to marry. Upon reaching a remote crossroads, and collapsing there in exhaustion, the ghostly pack of hounds and horse drawn coach approach from the darkness. Stopping at the crossroads, a man steps out of the coach, and the young woman recognises him to be the ghost of Sir Francis Drake.

He enquired of the young woman, why she was out on the moor alone and in a state of desperation and exhaustion, and she told him of her plight. Drake pulled from beneath his cloak a box and a cloth, and gave these to the young woman telling her to continue gently on her way, and not, under any circumstance, to look back.

The maid did as she was instructed, and when her pursuer reached the crossroads, he asked of the dark figure in the coach if he had seen a young maid passing by. Drake asked the man to step into his coach, and as he did, its door shut fast and the coach and hounds disappeared back into the darkness. The man was never to be seen again, and it is said that when morning came, his horse was found at the remote crossroads and had apparently died of fright.

According to research by the Devonshire cunning man Jack Daw, there is said to be a family line of Pellars, descended from the girl who encountered the spirit of Sir Francis Drake on the Moor. Their powers, it is claimed, are derived from the gift of the box and cloth he had given to her on that night.”

—

Silent as the Trees:

Devonshire Witchcract, Folklore & Magic

by Gemma Gary

#sir Francis drake#Gemma Gary#silent as the trees#Devonshire witchcraft#Devonshire magic#traditional withcraft#witchcraft#magic#quote

68 notes

·

View notes

Link

Over the past few years, anti-authoritarians on the left have been paying increasing attention to “tankies.”

A derogatory term, “tankies” was originally applied to members of the Communist Party of Great Britain who supported Moscow’s crushing of the 1956 Hungarian revolution, which was infamously carried out with the heavy deployment of Soviet tanks.

Today the word refers to leftists, primarily Western, who resort to all kinds of justifications for authoritarian regimes in the so-called “global south,” such as in Syria, Hong Kong, and Nicaragua, and/or in countries with an ambiguous status within “the West,” like Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia. These countries can be referred to collectively as countries of “the periphery,” to use Istanbul-based Mangal Media’s terminology, so as to emphasize the centrality of “the West” in tankie ideology.

On domestic issues such as the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, tankies tend to take progressive positions. This makes their politics on peripheral countries all the more confusing, especially for those of us on the receiving end of our governments’ brutalities. Tankies would thus condemn American cops yet praise Hong Kong cops, or condemn the Israeli military while praising the Russian army.

This contradiction at the heart of tankie logic derives from a simplistic interpretation of imperialism, and with it, of anti-imperialism. This “alt-imperialist” logic divides the world into two camps : those who are “pro-West” and those who are “anti-west.” In the words of the late theorist Moishe Postone, this is essentially a manifestation of the “dualistic political imaginary of the Cold War.” The Syrian writer Leila Al-Shami, meanwhile, called it “the anti-imperialism of idiots.”

Activists who are otherwise progressive and even revolutionary can therefore end up, at best, reproducing the narratives propagated by authoritarian governments in peripheral countries; at worst, they could be actively supporting brutal repression.

The broad scope of this brand of “anti-imperialism” has also allowed right-wing types to make their way into various left-wing circles in the West, as part of a broader phenomenon in which fascist movements co-opt left-wing talking points in support of illiberal regimes or ideologies. This is amply illustrated by programs on the Russian state-affiliated outlet RT or Fox News’ “Tucker Carlson Tonight,” both of which regularly feature far-right and left-wing “anti-imperialist” personalities.

In these news and social media circles, “anti-imperialist” rhetoric is often accompanied by a disregard for facts that has been increasingly visible in the aftermaths of the Brexit campaign and Donald Trump’s U.S. presidential victory in 2016.

Yet this phenomenon was already apparent in the conversations on Syria and Ukraine years before, as Russian military interventions in both countries were coupled with substantial online dis/misinformation campaigns. Such tactics have become the calling cards of authoritarian leaders around the globe, including Trump, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, China’s Xi Jinping, Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu, India’s Narendra Modi, and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro.

Having followed these trends for years, I anticipated a similar reaction from tankies during and after Lebanon’s October 2019 uprising; the government we have been opposing and charging with corruption is dominated by the vocally “anti-imperialist” Hezbollah and its allies, Amal and the Free Patriotic Movement. This dynamic has been worsened by the fact that the traditional sectarian parties that consider themselves to be Lebanon’s “opposition” are pro-West and pro-Gulf Arab states, and thus according to alt-imperialist logic, are inherently “pro-imperialist.”

This talking point has been further buttressed by both the Israeli and U.S. governments’ singling out of Hezbollah as the sole source of Lebanon’s evils. According to tankie logic, Lebanese anti-government protesters are in fact on the side of U.S. imperialism, despite the protestors’ vocal opposition to all the major political parties. Many Lebanese activists have also been puzzled by the online reactions of various prominent figures on the left, particularly Americans, who repeatedly ignored the activists’ lived experiences in service of their own “alt-imperialism.”

This distorted anti-imperialism exposed Lebanon’s protest movement to the usual accusations that they were being paid by foreign governments and were part of a global conspiracy against Hezbollah and the “Resistance” against Israel. Lebanese Shi’a protesters were particularly targeted by Hezbollah supporters, who smeared them as “embassy” Shi’as (i.e. paid by foreign embassies). This has since taken on dangerous dimensions such as death threats and physical assaults, with some activists opting for online anonymity or withdrawing from public life; many others are planning to leave Lebanon entirely.

[...]

Many left-wingers seem to be either unaware or in denial about the fact that fascist anti-imperialists exist as well. As a result, authoritarians are effectively given permission to accuse anti-authoritarians of being pro-West imperialists. Combined with the fact that activists in peripheral countries usually have more to risk and more to lose than Western tankies, this process ends up taking a heavy emotional and mental toll on the activists.The solution to this state of affairs is both straightforward and complex.

It is straightforward because opposing Russian or Chinese imperialism can be done in the same vein as opposing U.S. imperialism. Yet pressing this argument also requires tankies to decenter “the West” — where they are overwhelmingly located — from their analysis, and in doing so also requires them to decenter themselves. Only then would these “anti-imperialists” truly oppose that which they claim to oppose: destruction and injustice, regardless of who is committing them. Abandoning such binary camps in favor of truly transnational and anti-authoritarian principles would benefit these activists and their causes.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why UK Tobacco Companies Should Be in Your Retirement Portfolio

Tobacco companies have produced great returns for shareholders.

Many investors dismiss tobacco companies as "boring ".Others dismiss tobacco companies altogether on ethical grounds. However, by their very nature, tobacco companies are huge producers of cash.

Creating a killing

Many investors refuse steadfast to buy tobacco companies purely on ethical grounds. It's been proven that their main products - cigarettes and cigars - harm the health of a large proportion of its users.pepe tabak Smoking regularly usually takes a long period off a person's life expectancy.

Putting ethical concerns aside for an instant, who wouldn't wish to be selling something which will be legal and that folks are now actually addicted to, and for which there's no real substitute? Remember what multi-billionaire investor Warren Buffett once said about tobacco companies:

"I'll let you know why I such as the cigarette business. It costs a dollar to make. Sell it for a dollar. It's addictive. And there's fantastic brand loyalty ".

The tobacco companies'products is for thousands of people a'need to have'product rather than a'nice to own'product. They keep returning for more to feed their addiction. Sometimes they trade down to purchase cheaper brands, which are often produced by the same company.

Some customers quit the smoking habit but most just keep on buying, even though their income falls during a recession. Often, people reach for'fags and booze'when things turn grim economically.

Whatever the economic situation, tobacco companies'earnings remain strong as a result of perceived pricing power of these products which stems from the potency of their brands, and the diversity of these product range on offer.

Smoking politics earning big money

The largest risk with tobacco companies is political risk in developed countries. Tobacco related illnesses kill people and given its perceived cost to society, governments must be seen as doing something to prevent people from (starting to) smoking, such as for instance smoking bans in public areas places, limiting advertisements directed at younger people, restricting the freedom of the tobacco industry to introduce services, making tobacco products available in the same generic packaging, restrictions on point-of-sale advertising, etc.

However, critics of further anti-smoking legislation are quick to point out that both the US and UK governments are'addicted'to tobacco tax revenues. For example, the UK's tax take via duty and VAT, totaling some 10bn in 2008/2009 alone and is forecasted to be substantial higher in 2010 consequently of further tax hikes.

We must also not forget that, in the UK, smokers pay more in taxes than it costs the National Health Service to deal with smoking-related illnesses (the current figures are that roughly 2 of taxes is collected for every 1 spent on treatment). Smokers also "benefit" society because they do not collect the State Pension for as long as non-smokers. Additionally, smokers provide lots of jobs in healthcare and revenues for pharmaceutical companies.

Developing markets are the future

Nowadays, you will find four truly global suppliers, including two in the United Kingdom: British American Tobacco ("BAT") and Imperial Tobacco - both of which are in the FTSE 100 index - Philip Morris International and Japan Tobacco (the owner of Gallagher).

In the long term, the earnings of Western tobacco companies will soon be driven by increasing volumes in emerging markets. Lately, cigarette consumption in developing countries has increased by 1 - 3 per cent while it has declined 2 - 4 per cent in older markets such as for instance Western Europe and the USA. As emerging countries develop, increased discretionary income will ensure that tobacco products become more affordable

The long run growth of Western tobacco companies clearly depends on them spreading the smoking habit through the entire globe, particularly in the newly industrialising countries and the next world. Western companies like BAT and Imperial Tobacco have the advantage that their aspirational Western brands are highly valued in developing countries.

Growth by acquisition

While the days of the mega-mergers in the tobacco industry are likely to be over, in reality Philip Morris International itself was created as a spin off from Altria in 2008, both British American Tobacco along with Imperial Tobacco have recently increased their experience of faster growing developing countries by acquisition.

In June 2009, British American Tobacco acquired Bentoel which will be the fourth largest tobacco company in Indonesia. Following this acquisition, the Asia Pacific region accounts now for 25 per cent of BAT's sales volume. Per year earlier, BAT completed the purchase of Tekel in Turkey, boosting its position because country fivefold.

BAT nowadays claims that it's "the world's most international tobacco group" along with the world's second largest listed tobacco company. BAT's five most important markets, include Brazil, Russia, South Africa, Australia and Canada - all commodity-based economies, whilst it's also having significant experience of Latin America, Asia Pacific, Africa and the Middle East - all significant growth areas.

While Imperial Tobacco's "catching up" acquisition of Altadis of Spain, in early 2008, substantially expanded its presence in African and Eastern European emerging markets, which makes it the world's fourth largest listed tobacco company. However, over 75 per cent of Imperial's revenues remain derived from Europe, whilst controlling 45 per cent of the UK market.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Seabird Poop Is Worth More Than $1 Billion Annually

https://sciencespies.com/nature/seabird-poop-is-worth-more-than-1-billion-annually/

Seabird Poop Is Worth More Than $1 Billion Annually

When Don Lyons, director of the Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program visited a small inland valley in Japan, he found a local variety of rice colloquially called “cormorant rice.” The grain got its moniker not from its size or color or area of origin, but from the seabirds whose guano fertilized the paddies in the valley. The birds nested in the trees around the dammed ponds used to irrigate the rice fields, where they could feed on small fish stocked in the reservoirs. Their excrement, rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, washed into the water and eventually to the paddies, where it fertilized the crop.

The phenomenon that Lyons encountered is not a new one—references to the value of bird guano can be found even in the Bible, and an entire industry in South America grew around the harvesting of what many called “white gold.” What is new is that scientists have now calculated an exact value for seabird poop. This week, researchers published a study in Trends in Ecology and Evolution that estimates the value of seabird nutrient deposits at up to $1.1 billion annually. “I see that [many] people just think you care about something when it brings benefits, when they can see the benefits,” says Daniel Plazas-Jiménez, study author and researcher at the Universidade Federal de Goiás in Brazil. “So, I think that is the importance of communicating what seabirds do for humankind.”

Given that 30 percent of the species of seabirds included in the study are threatened, the authors argue that the benefits the birds provide—from fertilizing crops to boosting the health of coral reefs—should prompt global conservation efforts. Government and interested parties can help seabirds by reducing birds accidently caught during commercial fishing, reducing the human overfishing that depletes the birds’ primary food source and working to address climate change since rising seas erode the birds’ coastal habitats and warming waters cause the birds’ prey fish to move unpredictably.

To show the benefits seabirds provide, Plazas-Jiménez and his coauthor Marcus Cianciaruso, an ecologist at Goiás, set out to put a price tag on the animals’ poop. Scientists and economists lack sufficient data on the direct and indirect monetary gains from guano. So the ecologists had to get creative; they used a replacement cost approach. They estimated the value of the ecological function of bird poop as an organic fertilizer against the cost of replacing it with human-made chemical fertilizers.

Guano bags ready for distribution and sale in Lima, Peru

(Photo by Manuel Medir/Getty Images)

Not all seabirds produce guano, which is desiccated, or hardened, excrement with especially high nitrogen and phosphoric content, so the authors took a two-step process to figure out how much waste the birds produce. First, the authors calculated the potential amount of poop produced annually by guano-producing seabirds based on population size data. They valued the guano based on the mean international market price of Peruvian and Chilean guano, which represented the highest-grossing product. Next the scientists estimated the value produced by non-guano-producing seabirds, who also excrete nitrogen and phosphorus. The researchers valued the chemicals based on the cost of inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus traded on the international market. The primary value of the poop based on replacement costs was around $474 million.

The scientists then estimated that ten percent of coral reef stocks depend on nutrients from seabirds, a back of the envelope number that they admit needs more study. Since the annual economic return of commercial fisheries on Caribbean reefs, Southeast Asian reefs and the Great Barrier Reefs is $6.5 billion, the scientists estimated secondary economic benefits from seabird guano to be at least $650 million. That brought the estimated total benefit of guano up to $1.1 billion.

Still, that number, Lyons says, is likely a pretty significant underestimate since there are secondary benefits to not producing chemical fertilizers. “Another aspect of that is the replacement product, fertilizers, are generally derived from petroleum products,” says Lyons. “And so, there’s a climate angle to this—when we can use more natural nutrient cycling and not draw on earth reserves, that’s a definite bonus.”

Though the billion dollar-plus price on poop is impressive, it is likely much lower than the comparative value before seabird numbers declined over the past roughly 150 years. The richness of guano in South America, particularly on the nation’s Chincha Islands, has been documented for centuries. Birds nest along the island’s granite cliffs where their excrement builds up and the hot, dry climate keeps it from breaking down. At one point, an estimated 60 million birds—including guanay cormorants, boobies and pelicans—built 150-foot-high mounds of poop. The Incans were the first to recognize guano’s agricultural benefits, supposedly decreeing death to those who harmed the seabirds.

By the early 1840s, guano became a full-blown industry; it was commercially mined, transported and sold in Germany, France, England and the United States. The 1856 Guano Islands Act authorized one of the United States’ earliest imperial land grabs outside of North America, stating that the nation could claim any island with seabird guano, as long as there were no other claims or inhabitants. This paved the way for major exploitation and the establishment of Caribbean, Polynesian and Chinese slave labor to work the “white gold” mines.

The industry crashed around 1880 and revived in the early 20th century. Today, interest in guano is resurgent as consumer demand for organic agriculture and food processing has risen. However, only an estimated 4 million seabirds now live on the Chincha islands, drastically reducing the amount of guano produced. This loss is part of a global trend. According to one study, the world’s monitored seabird populations have dropped 70 percent since the 1950s.

The decline of seabird populations, says Plazas-Jiménez, is devastating to local cultures that have used the organic fertilizers for generations, local economies that depend on fisheries, and the world’s biodiversity. One study found that guano nutrient run-off into the waters of the Indian Ocean increasing coral reef fish stocks by 48 percent. Another study found that dissolved values of phosphate on coral reefs in Oahu, Hawaii, were higher where seabird colonies were larger and helped to offset nutrient depletion in the water caused by human activities.

Improving the health of coral reefs is important. Roughly a quarter of ocean fish depend on nutrient-rich reefs to survive. And seabirds’ contributions to coral reef health provide ecosystem services beyond increasing fish stocks; they also drive revenue through tourism and coastline resilience. Coral reefs function as important natural bulkheads protecting remote island and coastal communities from storm erosion and rising water. “It’s really compelling to think in terms of billions of dollars, but this is also a phenomenon that happens very locally,” says Lyons. “And there are many examples of where unique places wouldn’t be that way without this nutrient cycling that seabirds bring.”

#Nature

1 note

·

View note

Text

Base Metal Mining Market Based On Development, Scope, Trends, Forecast By 2027

Introduction of Base Metal Mining Market :

The report covers all the trends and technologies playing a major role in the growth of the base metal mining market over the forecast period. It highlights the drivers, restraints, and opportunities expected to influence the market growth during this period.

Maximize Market Research report is a user-based library of a Base Metal Mining Market report database, delivers comprehensive reports with a detailed analysis of changing market trends, key segments, top investment organisations, value chain, regional landscape, and competitive scenario.

Each and every insights presented in the reports published by expert group of Maximize Market Research, which is derived from primary interviews with top officials from leading companies of the domain concerned. Report’s secondary data research methodology includes deep online and offline research and discussion with expert professionals and analysts in the industry. In report, Base Metal Mining Market reports, industry trends have been explained on the macro level, which is expected to help to finding outline market landscape and probable future issues.

Request for free sample:

https://www.maximizemarketresearch.com/request-sample/34133

COVID-19 Impact on Base Metal Mining Market :

The report has identified detailed impact of COVID-19 on Base Metal Mining Market in regions such as North America, Asia Pacific, Middle-East, Europe, and South America. The report provides Comprehensive analysis on alternatives, difficult conditions, and difficult scenarios of Base Metal Mining Market during this crisis. The report briefly elaborates the advantages as well as the difficulties in terms of finance and market growth attained during the COVID-19. In addition, report offers a set of concepts, which is expected to aid readers in deciding and planning a strategy for their business.

Ask your queries regarding the report:

https://www.maximizemarketresearch.com/market-report/global-base-metal-mining-market/34133/

Base Metal Mining Market Segmentation:

Base Metal Mining Market size is studied using various approaches and analyses in this research report to provide reliable and in-depth information about the industry. It is segmented into numerous segments to cover various aspects of the market for a better understanding.

Global Base Metal Mining Market, by Type

• Aluminum

• Copper

• Lead

• Nickel

• Zinc

• Others

Global Base Metal Mining Market, by End User

• Construction

• Automotive

• Electrical & Electronics

• Consumer

Base Metal Mining Market Regional Insights:

Asia-Pacific (Vietnam, China, Malaysia, Japan, Philippines, Korea, Thailand, India, Indonesia, and Australia)

Europe (Turkey, Germany, Russia UK, Italy, France, etc.)

North America (the United States, Mexico, and Canada.)

South America (Brazil etc.)

The Middle East and Africa (GCC Countries and Egypt.)

Key players:

The research report includes the current Base Metal Mining Market size of the market and its growth rates based on 5-year statistics and records with company summary of Key players:

• Alcoa Inc.

• Anglo American plc

• Antofagasta plc

• BHP Billiton Ltd.

• First Quantum Minerals Ltd.

• Freeport-McMoRan Inc.

• Glencore plc

• Kaiser Aluminum Corporation

• Rio Tinto plc

• Teck Resources Limited

• Vale SA.

• MMC Norilsk Nickel

• Bosai Minerals Group

• Glencore International

• Southern Copper Corp.

• United States Steel Corp.

• Royal Nickel Corporation

• Lundin Mining Corp.

• Hudbay Minerals Inc.

• Independence Group NL

• Nevsun Resources Ltd.

• Cliffs Natural Resources Inc.

• Ferrexpo Plc

• Western Areas NL

• Imperial Metals Corp.

• Metals X Ltd.

• Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc.

• Vedanta Resources Plc

Prime Reasons to purchase a Base Metal Mining Market research report:

The goal of this research report is to help consumers to gain a more information and clearer understanding of the industry. The Base Metal Mining Market growth analysis includes development trends, competitive landscape analysis, investment plan, business strategy, opportunity, and key regions development status for international markets.

The Base Metal Mining Market overview and the analysis of several affecting elements such as drivers, restraints, and opportunities.

Porter's Five Force Analysis and SWOT analysis are used to define, characterise, and analyse the market competition landscape, with a focus on key players.

Extensive analysis into the global Temperature Sensor competitive landscape

Identification and analysis of micro and macro elements that influence and will influence market growth.

A comprehensive list of major market players in the global Temperature Sensor industry.

In the Base Metal Mining Market , it provides a descriptive study of demand-supply chaining.

Statistical study of certain key economic statistics

Figures, charts, graphs, and illustrations are used to clearly describe the market.

About Us:

Maximize Market Research provides syndicate as well as custom made business and market research on 12,000+ high growth emerging technologies & opportunities in Chemical, Healthcare, Pharmaceuticals, Electronics & Communications, Internet of Things, Food and Beverages, Aerospace and Defense and other manufacturing sectors.

0 notes

Text

When Fred Halliday—scholar, activist, journalist and teacher—died two years ago at the too-early age of 64, obituaries and tributes swamped the British press; the New Statesman subtitled its remembrance “The death of a great internationalist.” Halliday was a truly original thinker, a combination of Hannah Arendt (in her concern for the connection between ethics and politics) and Isaac Deutscher (in his materialist yet supple approach to history). Halliday also knew a little something about the Middle East: he spoke Arabic, Farsi and at least seven other languages, and he traveled widely throughout the region, including in Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Palestine, Israel, Libya and Algeria. He is one of the very few writers who, after 9/11, understood the synthesis between fighting radical Islam and opposing the brutal inequities of the neoliberal global order. He was an uncategorizable independent, supporting, for instance, the communist government in Afghanistan and the US invasion of that country. He embodied the dialectic between utopianism and realism. In his scholarship and research, in his outspokenness and courtesy, in the complexity of his thinking, he was the model of a public intellectual. It is Halliday’s writings—not those of Noam Chomsky, Edward Said, Alexander Cockburn, Christopher Hitchens or Tariq Ali—that can elucidate the meaning of today’s most virulent conflicts; it is Halliday who represented radicalism with a human face. It says something sad, and discouraging, about intellectual life in our country that Halliday’s death—which is to say, his work—was ignored not only by mainstream publications like The New York Times but by their left-wing alternatives too (including this one).

It is cheering, then, that a selection of essays, written by Halliday for the website openDemocracy between 2004 and 2009, has just been published by Yale University Press. Called Political Journeys, it gives a taste—though only that—of the extraordinary range of Halliday’s interests; included here are analyses of communism , the cold war, Iran’s revolution, post-Saddam Iraq, violence and politics, radical Islam, the legacies of 1968 and feminism. The book gives a sense, too, of Halliday’s dry humor—he loved to recount irreverent political jokes from the countries he had visited—and his affection for lists, as in the essay “The World’s Twelve Worst Ideas” (No. 2: “The only thing ‘they’ understand is force”). But most of the articles, written as they were for the Internet, are comparatively short and represent a brief span in a long career; this necessarily sporadic volume will, one hopes, lead readers to some of Halliday’s two dozen other books and more extensive essays.

Political Journeys is a well-chosen title for the collection. It alludes not just to Halliday’s travels but also to the ways his ideas—especially about revolution, imperialism and human rights—changed in reaction to tumultuous world events over the course of four decades. For this he has often been attacked, even posthumously. Earlier this year, Columbia University professor Joseph Massad opened a piece about Syria, published on the Al Jazeera website, by dismissing Halliday—along with his “Arab turncoat comrades”—as a “pro-imperial apologist.” (Massad also put forth the novel idea that Syria “has been…an agent of US imperialism,” which might be news to Bashar al-Assad and the leaders of Iran and Hezbollah, Syria’s allies in the so-called axis of resistance.) Yet it was precisely Halliday’s intellectual flexibility—his ability to derive theory from experience rather than shoehorn the latter into the former—that was one of his greatest strengths. Pace Massad,

Halliday didn’t move from Marxism into imperialism, neoconservatism, neoliberalism or “turncoatism”; rather, he developed a deeper, more humane and far sturdier kind of radicalism. It was one that refused to hide—much less celebrate—repression, carnage and virulent nationalism behind the banner of progress, world revolution, selfdetermination or anti-colonialism. Halliday sought not to reject the socialist tradition but to reconnect it to its heritage—derived from the Enlightenment, from 1789, from 1848— of reason, rights, secularism and freedom. He would also develop an unsparing critique of the anti-humanism that, he thought, was ineradicably embedded in the revolution of 1917 and its successors.

Halliday believed that the duty of committed intellectuals is to keep their eyes open, to learn from history, to be humble enough to be surprised (and to admit being wrong). The alternative was what he called “Rip van Winkle socialism.” He sometimes told his friends, “At my funeral the one thing no one must ever say is that ‘Comrade Halliday never wavered, never changed his mind.’”

* * *

Fred Halliday was born in 1946 in Dublin and raised in Dundalk, a town near the northern border that, he pointed out, The Rough Guide to Ireland advises tourists to avoid. The Irish “question” and Irish politics remained, for him, a touchstone—though more as a warning than an inspiration, especially when it came to Mideast politics. The unhappy lessons of Ireland, he wrote in 1996, included “the illusions and delusions of nationalism” and “the corrosive myths of deliverance through purely military struggle.” He added: “A good dose of contemporary Irish history makes one sceptical about much of the rhetoric that issues from dominant and dominated alike.… [A] critique of imperialism needs at the very least to be matched by some reserve about most of the strategies proclaimed for overcoming it.” Growing up in the midst of the Troubles, Halliday developed, among other things, a healthy aversion to histrionic nationalism and the repugnant concept of “progressive atrocities.”

Halliday graduated from Oxford in 1967 and then attended the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Later he would earn a PhD from the London School of Economics (LSE), where, for over two decades, he taught students from around the world and was a founder of its Centre for the Study of Human Rights. (The intellectual and governing classes of the Middle East are sprinkled with his graduates.) He was an early editor of the radical newspaper Black Dwarf and, from 1969 to 1983, a member of the editorial board of the New Left Review, a journal for which he occasionally wrote even after he broke with it over key political issues. He immersed himself in the revolutionary movements of his time and gathered an enviable range of friends, interlocutors and contacts along the way: traveling with Maoist Dhofari rebels in Oman; working at a student camp in Cuba; visiting Nasser’s Egypt, Ben Bella’s Algeria, Palestinian guerrillas in Jordan and Marxist Ethiopia and South Yemen (the subject of his dissertation). He wasn’t shy: he proposed a two-state solution to Ghassan Kanafani of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, infamous for its hijackings; argued with Iran’s foreign minister about the goals of an Islamic revolution; told Hezbollah’s Sheik Naim Qassem that the group’s use of Koranic verses denouncing Jews was racist—“a point,” Halliday dryly noted, “he evidently did not accept.”

Halliday received, and accepted, invitations to lecture in some of the Middle East’s most repressive countries, including Ahmadinejad’s Iran, Qaddafi’s Libya and Saddam’s Iraq, where a government official told him, without shame or embarrassment, that Amnesty International’s reports on the regime’s tortures and executions were correct. Clearly, he was no boycotter. But neither was he seduced by these visits: in 1990, he described Iraq as a “ferocious dictatorship, marked by terror and coercion unparalleled within the Arab world”; in 2009, he reported that the supposedly new, rehabilitated Libya was just like the old, outcast Libya: a “grotesque entity” and “protection racket” that was regarded as a joke throughout the Arab world. His moral compass remained intact: that year, he warned the LSE not to accept a £ 1.5 million donation from the so-called Charitable and Development Foundation of the dictator’s son, Saif el-Qaddafi. Alas, greed trumped principle, and Halliday’s arguments were rejected—which led, once the Arab Spring reached Libya, to the LSE’s public disgrace and the resignation of its director.

* * *

In May 1981, Halliday published an article on Israel and Palestine in MERIP Reports, a well-respected Washington journal that focuses on the Middle East and is closely identified with the Palestinian cause. It is an astonishing piece, especially in the context of its era, more than a decade before the Palestine Liberation Organization recognized Israel’s right to exist and the signing of the Oslo Accords. It is no exaggeration to say that, at the time, the vast majority of the left, Marxist and not, held anti-Israel positions of various degrees of ferocity; to do otherwise was to risk pariahdom.

While harshly critical of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians and of the occupation , Halliday proceeded to question—and forcefully rebuke—the bedrock beliefs of the left: that Israel was a colonial state comparable to South Africa; that Israelis were not a nation and had no right to self-determination; that Israel was a recently formed and therefore inauthentic country (most states in the Middle East—including, for that matter, Palestine— are modern creations of imperialist powers); that a binational state was desired by either Israelis or Palestinians and, therefore, could be a recipe for anything other than civil war and a harshly authoritarian government. (Halliday asked a question often ignored by revolutionaries: Why would anyone want to live under such a regime?)

Most of all, he challenged the irredentism of the Palestinian movement and its supporters. Partition, he presciently warned, is “the only just and the only practical way forward for the Palestinians. They will continue to pay a terrible price, verging on national annihilation, if they prefer to adopt easier but in fact less realizable substitutes, and if their allies and supposed friends continue to urge such a course upon them.” Halliday stressed that a truly revolutionary strategy cannot be “at variance with reality.” Solidarity without realism is a form of betrayal.

The reality principle, and its absence, was a theme Halliday would return to frequently, as in his reappraisal of the legacy of 1968. “It does not deserve the sneering, partisan dismissal,” he wrote in 2008. But nostalgic celebration was also unearned, for “the problem is that in many ways, we lost.” Despite triumphal rhetoric, the year of the barricades led not to worldwide revolution but to conservative governments in France, England and the United States (Richard Nixon). In the communist world, the situation was even worse: “It was not the emancipatory imagination but the cold calculation of party and state that was ‘seizing power.’” In Prague, socialist reform was crushed; in Beijing, the Cultural Revolution’s frenzy reached new heights.

Yet Halliday, like most of us, was sometimes guilty of letting wishful thinking cloud his vision too. In 2004, he called for the United Nations to assume authority in Iraq, which was then in free fall. This ignored the fact that Al Qaeda’s shocking bombings of the UN’s Baghdad mission the previous year—resulting in the death of Sergio de Mello, the secretary general’s special representative in Iraq, and so many others—had disposed, rather definitively, of that issue; the UN had withdrawn its staffers and, clearly, could not ask them to undertake another death mission. (Nor was there any indication that the UN’s member nations—many of whom opposed any intervention in Iraq—would have supported such a proposition.) And his claim, made in 2007, that “a set of common values is indeed shared across the world,” including a commitment to “democracy and human rights,” is hard to square with much of Halliday’s own reporting—such as his 1984 encounter with a longtime acquaintance named Muhammad, who had formerly been a member of the Iranian left. Now a supporter of the regime, Muhammad visits Halliday in London and explains, “We don’t give a damn for the United Nations.… We don’t give a damn for that bloody organisation, Amnesty International. We don’t give a damn what anyone in the world thinks.… We have made an Islamic Revolution and we are going to stick to it, even if it means a third world war.… We want none of the damn democracy of the West, or the socalled freedoms of the East.… You must understand the culture of martyrdom in our country.” Indeed, Halliday’s optimism of the intellect here is belied by even a casual look at any of the world’s major newspapers— whether from New York or Paris, Baghdad or Beirut—on any given day.

* * *

Iran, which Halliday first visited in the 1960s as an undergraduate, was foundational to his political development; he analyzed, and re-analyzed, its revolution many times, as if it was a wound that could not stop hurting. (Iran is the only country to which Political Journeys devotes an entire section of essays.) His initial study of the country, Iran: Dictatorship and Development, was written just before the anti-Shah revolution of early 1979. Based on careful observation and research, the book scrupulously analyzed Iran’s class structure, economy, armed forces, government, opposition movements, foreign policy—everything, that is, but the role of religion, which Halliday seemed to regard as essentially a front for political demands, and which he vastly underestimated. The book’s last sentence reads, “It is quite possible that before too long the Iranian people will chase the Pahlavi dictator and his associates from power… and build a prosperous and socialist Iran.”

Events moved quickly. In August 1979, Halliday filed two terrifying dispatches from Tehran, published in the New Statesman, documenting the chaotic atmosphere of fear and xenophobia, the outlawing of newspapers and political parties, and the brutal crackdown on women, intellectuals, liberals, leftists and secularists. “It does not take one long to sense the ferocious right-wing Islamist fervour that grips much of Iran today,” he began. Later, he would write, “I have stood on the streets of Tehran and seen tens of thousands of people…shouting, ‘Marg bar liberalizm’ (‘Death to liberalism’). It was not a happy sight; among other things, they meant me.” A revolution, he realized, could be genuinely anti-imperialist and genuinely reactionary.

But the problem wasn’t only Iran or radical Islam. As the ’70s turned into the ’80s, it became clear—or should have—that most of the third world’s secular revolutions and coups (in Algeria, Syria, Libya, Ethiopia and, especially, Iraq) had failed to fulfill their emancipatory promises. Each became a one-party dictatorship based on repression, torture and murder; each stifled its citizens politically, intellectually, artistically, even sexually; each remained mired in inequality and underdevelopment. None of this could be explained, much less justified, by the legacy of colonialism or the crimes of imperialism, real as those are. These were among the central issues that led to Halliday’s rift with the New Left Review—and that continue to divide the left, both here and abroad. Indeed, it is precisely these issues that often underlie (and sometimes determine) the debates over humanitarian intervention, the meaning of solidarity, the US role as a global power, the centrality of human rights and of feminism, and the Israel-Palestine conflict. (In 2006, Halliday would sum up his points of contention with his former comrades, especially their support of death squads and jihadists in the Iraq War : “The position of the New Left Review is that the future of humanity lies in the back streets of Fallujah.”)

Halliday’s revised thinking—his emphasis on democracy and rights; his aversion to the particularist claims of tribe, nation, religion or identity politics; his unapologetic secularism; his questioning of imperialism as a purely regressive force—is evident in his enormously compelling book Islam and the Myth of Confrontation, published in 1996. (Halliday dedicated it to the memory of four Iranian friends, whom he lauded as “opponents of religiously sanctioned dictatorship.”) In this volume he took on two still prevalent, and still contested, concepts: the idea of human rights as a Western imposition on the third world, and the theory of “Orientalism.”

Halliday argued that, despite the assertions of covenants such as the 1981 Universal Islamic Declaration of Human Rights (which defines “God alone” as “the Source of all human rights”) and the 1990 Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam (which defines “all human beings” as “Allah’s subjects”), there is no such thing as Islamic human rights—or, indeed, of rights derived from any religious source. Such rights apply to everyone and, therefore, must be based on man-made, universalist principles or they are nothing: it is the “equality of humanity,” not the equality before God, that they assert. (That is why they are human rights.) Because rights are grounded in the dignity of the individual, not in any transcendent or divine authority, they can be neither granted nor rescinded by religious authorities, and no country, culture or region can claim exemption from them by appealing to holy texts, a history of oppression, revered traditions or because rights “somehow embody ‘Western’ prejudice and hegemony.”

In this light, the search for a kinder, gentler version of Islam—or, for that matter, of any religion—as the basis of rights is “doomed” to failure; for Halliday, the question of a religion’s content was entirely irrelevant. “Secularism is no guarantee of liberty or the protection of rights, as the very secular totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century have shown,” he argued. “However, it remains a precondition, because it enables the rights of the individual to be invoked against authority.… The central issue is not, therefore, one of finding some more liberal, or compatible, interpretation of Islamic thinking, but of removing the discussion of rights from the claims of religion itself.… It is this issue above all which those committed to a liberal interpretation of Islam seek to avoid.” The issues that Halliday raised in 1996 are by no means settled today, and they are anything but abstract; on the contrary, the Arab uprisings have forced them insistently to the fore. In Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, secularists and Islamists struggle over the role (if any) of Islam in writing new constitutions and legal codes; at the United Nations, new leaders such as Egypt’s Mohamed Morsi and Yemen’s Abed Rabbu Mansour Hadi argue that the right to free speech ends when it “blasphemes” against Islamic beliefs.

But more than a defense of secularism is at stake here. Halliday argued that the very idea of a unitary, reliably oppressive behemoth called the West—on which so much antiimperialist and “dependency” theory rested— was false. “Far from there having been, or being, a monolithic, imperialist and racist ‘West’ that produced human rights discourse, the ‘West’ itself is in several ways a diverse, conflictual entity,” he wrote. “The notion of human rights was not the creation of the states and ruling elites of France, the USA, or any other Western power, but emerged with the rise of social movements and associate ideologies that contested these states and elites.” The West embodied emancipation and oppression, equality and racism, abolitionism and slavery, universalism and colonialism. Political theories and practices that refuse to acknowledge this—proudly brandishing their “anti-Western” credentials—will be based on the shakiest foundations.

* * *

The argument between advocates of the concept of “Orientalism,” put forth most famously by Edward Said, and its critics—often associated with the scholar Bernard Lewis—was close to Halliday. Lewis had been a mentor of his at SOAS, and one he admired; Said, whom Halliday described as “a man of exemplary intellectual and political courage,” was a friend. (Though not forever: Said stopped talking to Halliday when the two disagreed on the first Gulf War.) Yet on closer look, Lewis and Said shared an orientation: both had rejected a materialist analysis of Arab (and colonial) history and politics in favor of a metadebate about literature. “For neither of them,” Halliday argued, “does the analysis of what actually happens in these societies, as distinct from what people say and write about them…come first.” Increasingly, Halliday would regard the Orientalist debate as one that deformed, and diverted, the discipline of Mideast studies and helped to foster a vituperative atmosphere.

Said had argued that, for several centuries, British and French writers, statesmen and others had created a static, mythical Middle East—sometimes romanticized, sometimes denigrated, always objectified— as part of an unwaveringly racist, imperialist project. (Indeed, Said’s book has turned the word “Orientalist,” which used to refer to scholars of the Muslim, Arab and Asian worlds, into a term of opprobrium.) With sobriety and respect, Halliday considered and, in the end, devastatingly refuted the theory’s major tenets. With its sweeping, all-encompassing claims, he argued, the concept of Orientalism was a form of fundamentalism: “We should be cautious about any critique which identifies such a widespread and pervasive single error at the core of a range of literature.” It was based on a widely held yet entirely unsubstantiated belief that Europe bore a particular hostility toward the Muslim world: “The thesis of some enduring, transhistorical hostility to the orient, the Arabs, the Islamic world, is a myth.” It was undialectical, ignoring not only the myths that Easterners projected against the West—ignorant stereotyping is, if nothing else, a busy two-way street—but the ways the East itself reproduced the tropes of Orientalism: “A few hours in the library with the Middle Eastern section of the Summary of World Broadcasts will do wonders for anyone who thinks reification and discursive interpellation are the prerogative of Western writers on the region.” In fact, Islamists can be among the greatest Orientalists, for many insist on an Islam that is eternal, opaque and monolithic.