#Tarr Béla I Used to Be a Filmmaker

Photo

Tarr Béla, I Used to Be a Filmmaker (2013)

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

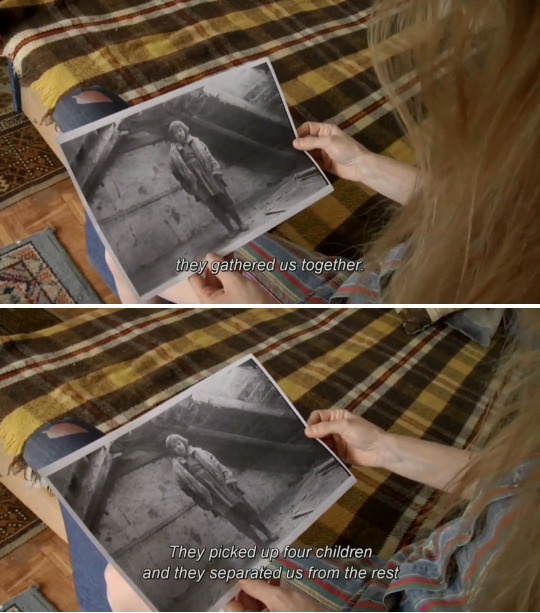

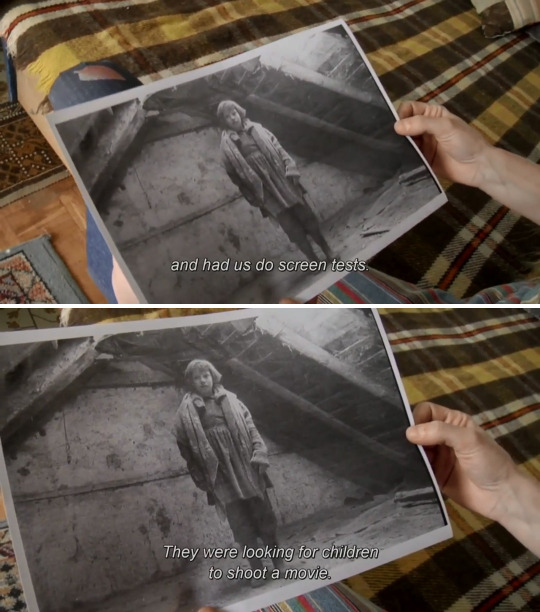

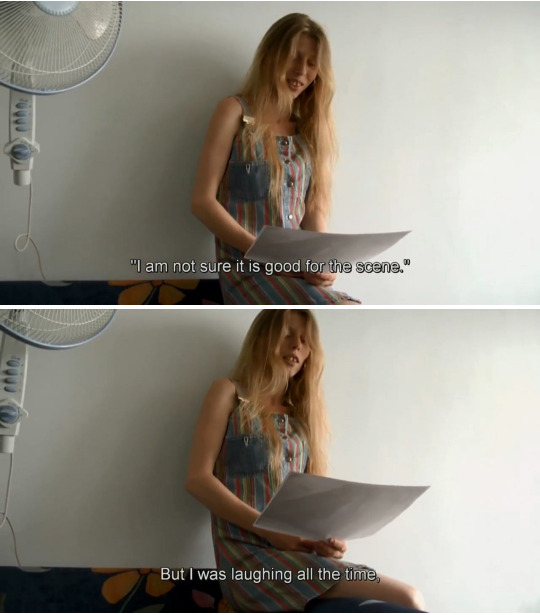

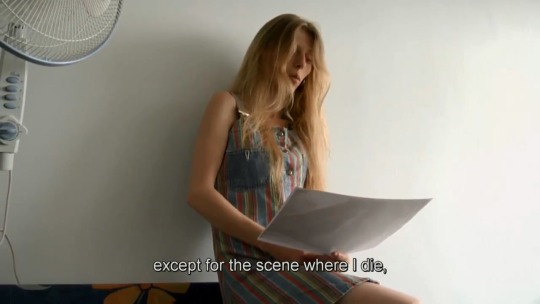

Erika Bók in Tarr Béla, I Used to Be a Filmmaker(2013) dir. Jean-Marc Lamoure, recounting her experiences of Sátántangó(1994)

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

• Mihály Vig •

Tarr Béla, I used to be a filmmaker (2013)

#Mihály Vig#béla tarr#Tarr Béla I used to be a filmmaker#movies#personal#silence#quotes#jean-marc lamoure#hungary#france#melancholy

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bela Tarr on the set of The Turin Horse (talking to lead actor János Derzsi) as featured in “Tarr Béla, I Used to Be a Filmmaker” (Jean-Marc Lamoure, 2013)

#bela tarr#the turin horse#film director#jános derzsi#documentary#jean-marc lamoure#Tarr Béla I Used to Be a Filmmaker

556 notes

·

View notes

Text

january 2022

*favorite

boys (1991, dir. tsai ming-liang)

past present (2013, dir. saw tiong guan)*

run away (1984, dir. wang toon)

the game they call sex (1987, dir. wang shaudi, roy chin, sylvia chang)

knives out (2019, dir. rian johnson)

drive my car (2021, dir. ryusuke hamaguchi)*

damnation (1988, dir. béla tarr)*

the ceremony (1971, dir. nagisa oshima)

armour of god (1986, dir. jackie chan & eric tsang)

memoria (2021, dir. apichatpong weerasethakul)*

---

so cool to have tsai's tv work and see how he could make great conventional narrative films too.

ive passively thought of tsai as a meek artist who is very lucky to have had the career he's had. but past present showed me how confident and independent he had to be to go to a foreign country (taiwan) and make a name for himself in the film/art industry. how the confidence and independence he developed was the result of having come from a very particular time and place.

between the two films i watched that tsai co-wrote for (run away and the game they call sex), two things struck me. one was the depiction of rape (in the former) and sexual assault (in the latter). maybe, in part, cheap sensationalist moves on the part of the filmmakers, but also evidently some sincere probing into human sexuality. because the other thing that struck me was how well written the films were (not that tsai gets all the credit for that). run away starts off like it may be a seven samurai clone but it turns out to be an incisive portrait of a disappearing way of life (banditry). and the game they call sex sounds like it's gonna be about sex lol but it's really an incisive portrait of women's experiences in a patriarchal, heteronormative society.

i always enjoy a rian johnson movie. i saw brick in high school, and last jedi was clearly the best of the newer star wars trilogy. knives out was also fun... a well done entertainment film can still bring me to the edge of my seat, but honestly the thrill is short lived as i am too well acquainted with the hollowness at the heart of such distractions. apparently, unfortunately, this is not what feeds my soul, so i must look elsewhere.

drive my car was about as good as they say. kitschy writing but the scenes really breathe. a breezy three hours, now that's a nice thing.

ive always been too impatient with movies, always thinking "how is there an hour left of this?" even though logically i know that's not so much time and much more time passes if i binge a tv show. nonetheless there was a knot in my mind, perhaps i was still not used to the flow of slower movies even after all this time. still looking for the wrong thing. looking at the looking in the wrong way. but i do feel now, finally, a bit of that tension loosen.

two hours is not so long. but a spell, but a dream.

so much racism and sexism to wade through just to see jackie chan do some cool jumps. unpalatable. 90 minutes is a long time when you have so little time.

memoria: joe's take on headless woman? another diptych. not a violent rain but a raining violence. right before the climax i had to pause and take a nap. i was so tired but didn't realize until the movie showed me.

what i like tells you too much about me. what i lack (courage), what i have (if anything). is what is "good" all the same? are the depths of my existence so narrow?

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

How I Letterboxd #3: Dave Vis

If you are one of the thousands of Letterboxd completists attempting to log every film on our official top 250, you have Dave Vis to thank for keeping that list current. He tells us why he adopted ownership of the list, how he felt when Parasite “dethroned” The Godfather, the curious case of A Dog’s Will, and several Dutch filmmakers worthy of discovery.

You wear your tenure proudly on your profile (“Member since 12/11/2011”). How did you come across Letterboxd way back then?

I joined in the beta days when I got an invitation in November 2011 from a good friend who knew I was into film. Up to this date, I have no idea how she got a beta invitation for a movie geek website from New Zealand, but I’m happy she did!

Here’s the $49 question: How do you Letterboxd?

I joined because I found it useful to keep track of everything I watched. At that point, I was probably still ticking off films from IMDb’s Top 250, and Letterboxd was a cool way to make other lists and see how I was progressing. When I started using the site more often, I also got to follow more users and enjoyed reading their takes on films. I don’t follow a lot of people, just a few that I know in real life and some other early adopters of the site whose opinions of film I got to value.

Talk us through your profile favorites. What spoke to you about these four films?

The pragmatic reason for these four is that they were the last films I watched that got full marks from me. So the four favorites on my profile keep changing as I come across more films that I think deserve five stars. About the current ones: Jaws, of course, is an absolute classic, maybe even Spielberg’s greatest. How he creates that much tension with minimal exposition is masterful. Blade Runner 2049 baffled me, especially on an aesthetic level. I love how the story slowly unravels in probably one of the best world-building efforts of the last couple of years. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring doesn’t need much explanation, I think. Peter Jackson did what was generally thought impossible and in a way that had me walking out of the cinema in awe of the spectacle and production design. Last but not least, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. I’m a huge fan of the Studio Ghibli films and this one, [as well as] being the studio’s unofficial first, is probably my favorite. You can just tell that they worked years to get Hayao Miyazaki’s life’s work to the big screen.

Let’s get down to brass tacks: for the past six and a half years, you’ve been running the Official Letterboxd Top 250, one of our most popular and important lists. What prompted you to start the list? Did you think you’d be keeping it going this long?

At least part of the credit goes to someone else on Letterboxd, because even my list is a cloned one! A great deal of thanks goes to a member called The Caker Baker, who sadly isn’t part of the community anymore, for having the idea of doing this list even before me. On the exact day Letterboxd introduced a sorting option by average rating on the Films page, he created the first top 250 list.

I decided to clone that list [Dave has archived it here], because I wanted to filter out the documentaries, shorts and miniseries. As long as I am interested in film and won’t have completed the list, I do see myself keeping it. I feel the overall quality of the list is outstanding and for my taste and film-watching experience it’s probably the best combination of blockbuster hits, timeless Hollywood classics, non-English spoken gems, and some pretty obscure entries.

What’s involved in keeping the top 250 up-to-date? What’s the hardest thing about it? Have you ever found the responsibility a burden—your ankle chained to Letterboxd each week? (We’re grateful!)

These days it isn’t much of a bother at all, actually. I’m still so grateful for you guys introducing the ability to sort lists by average rating when editing them a while back. That was a huge relief, I can tell you! And apart from the odd comment when I’m a bit late on my weekly update or when I’m on a well-deserved holiday (yes, even the ankle chain comes off once in a while), I don’t feel like it’s a burden at all.

Let’s unpack it a bit. What are the best films you’ve discovered because of the list? Shoutout to my choices: A Special Day, Harakiri and The Man Who Sleeps.

Harakiri is an excellent choice! If it wasn’t for Letterboxd’s top list, I would probably not even know about it today, although it also cracked IMDb’s top 250 last year. What a beautiful film. If I have to name two other, one would be The Cranes Are Flying. I’ve rarely seen a film about war being depicted so beautifully. The other is It’s Such a Beautiful Day, the animation by Don Hertzfeldt about a stick figure you get to care deeply about in a time span of just over an hour. Very different films that, without Letterboxd, the chances are next to zero that I would have checked either of them out. Joining a Kickstarter to finance my own Blu-ray edition of the latter was special too.

Béla Tarr’s 1994 masterpiece ‘Sátántangó’.

So, what’s your percentage-seen of the top 250? Which films rank highest on your list of shame? Are there any that you don’t think you’ll ever watch?

At this moment I’m at 175 of 250, so 70 percent. I rarely consider films as being on a ‘list of shame’, but as I scroll through the unseen ones, there are a few that stand out. La Dolce Vita and Sátántangó [Editor’s note: recently re-released in 4K, nudge nudge] are ones that I feel I should have watched by now. Both are magnum opuses from legendary foreign filmmakers. Don’t really know why I haven’t though, but all in good time. Any that I think I’ll never watch? There’s not much I wouldn’t watch, but some are just so daunting in their runtime, that I’m not sure if I will ever feel up to the task (yes, La Flor, I’m looking at you). Probably also the reason I never popped Sátántangó in.

Has the way Letterboxd’s membership has changed and grown affected what’s in the top 250 in any interesting or unexpected ways?

That’s not a very easy question to answer, because different people will be surprised about different things. However, you do see a trend—surprising or not—of traditional western cinema classics giving way to more non-English language films doing well on the list. Asian and Brazilian films have skyrocketed to great heights, often at the expense of western classics. Films that are traditionally doing great at IMDb, such as Pulp Fiction or The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, were in Letterboxd’s top ten for a long time, but have both dropped out of the top twenty. Beloved classics among film critics such as Citizen Kane, Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans and Casablanca aren’t even in the top 100 anymore.

We now have a top ten with three Japanese films, one Taiwanese, one Russian, one Brazilian and a South Korean film at the very top. The only English spoken films left there are the two Godfathers and 12 Angry Men. I do tend to suspect that the growing community causes more diversity while also fuelling the more traditional moviegoers to broaden their interests. I personally think that’s a great development.

How did you feel when Parasite overtook The Godfather to become Letterboxd’s highest-rated film of all time? Do you think it’ll ever sink at this point?

To say I was surprised is quite the understatement. For something to even come close to The Godfather’s record borders on sacrilege, let alone dethroning it. What you usually see is that new movies with overly positive reviews enter the list’s higher ranks with a bang, but when they are introduced to a bigger crowd, they slowly descend. For example, fellow acclaimed Best Picture nominees 12 Years A Slave, Her, Call Me By Your Name and Roma all peaked in the top twenty and only Call Me By Your Name is still in the list, at number 232 for now.

In these days of ready availability it is extremely hard to create something that has such a large following. That’s why this takeover by Parasite is so extraordinary. Seeing it rise day-by-day—even after the masses took it in—was something I didn’t think possible. I, for one, am very slow to watch new films, so when I got to watch it, it was already in first position. Safe to say my expectation level was through the roof, which probably wasn’t really fair. While I thought it was an excellent film, I personally wouldn’t rank it among my favorites. However, it’s not only the highest-ranked film on Letterboxd, but also the most popular one [a measure of the amount of activity for a film, regardless of rating]! So don’t expect to see it sink lower any time soon.

The top 250 is home to the largest comment section on the platform. Congrats! What’s monitoring that mammoth thread like?

Thank you! Although that’s hardly an achievement on my part. I have to be honest, I don’t read everything in the comments section anymore. I try to keep up as much as possible, in order to respond to people who have an actual question. However, when I sign in in the morning and see dozens of new notifications, most probably about A Dog’s Will being in the top ten or about recency bias or about objective quality versus subjective quality, I let it pass me by every so often.

What is your take on A Dog’s Will’s rise to Letterboxd stardom? (At the time of writing, the 2000 Brazilian film from director Guel Arraes holds the number eight spot in the top 250.)

Ah, there it is: the elephant in the room… My honest answer is a politically correct one, but also the truth: I haven’t seen it yet, so it’s impossible to pass judgment. However, from the comments section on the top 250, it seems clear that there are two camps: the Brazilians, who adore the film and continually claim the importance it in their cultural heritage. And there’s the other group, mostly non-Brazilians of course, who think it’s a fine film at best, but in their opinion not deserving of a top-ten spot. I’m quite impartial: if the statistics say that it is one of the best-rated films of the Letterboxd community, why would it not deserve to be there? I am curious though if more non-Brazilians will see it and if so, if that will have a significant effect on its rating. We can only wait and see.

Are there any films you’re surprised to have stayed in the list for so long? Conversely, what are some films that we’ll be surprised to hear have never made the list?

If I have to name one film that I’m surprised about, it’s one I haven’t seen yet: Paddington 2. Every time I scroll past it, I find myself asking: “wow, this one still in?” It’s probably because I haven’t seen it, but it always strikes me as an odd one. I really have to seek it out some time. Some films that might shock people never having made it… Well, if you look at IMDb’s list for reference, you could say it’s shocking that a film like Forrest Gump never made it onto the list, but that might not be as much of a shock to Letterboxd members. Other popular crowd pleasers that never made it include E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Gladiator, all of Disney’s non-Pixar animated classics, and one of the films that also sparked my interest in movies, The Usual Suspects.

Dave has not seen ‘Paddington 2’.

I’ve actually been working hard on completing the list during quarantine and I finished it yesterday. Has anyone else gotten to 100 percent yet or am I the first?

I have no idea, to be honest! There will probably be others who have, but I wouldn’t be able to name one. I suspect Jakk might have reached 100 percent at some point.

My completist streak will need a new avenue. What are your next most essential top lists?

If you ever feel up for a challenge, I recommend Top10er’s 1001 Greatest Movies of All Time. He combined the average ratings of critics and users from IMDb, Rotten Tomatoes, Metacritic and Letterboxd, and then weighted and tweaked the results with general film data from several services. I have no idea how, but it’s a terrific list. Also, the directors’ favorites lists that are on Letterboxd are awesome. Edgar Wright’s 1,000 favorites and Guillermo del Toro’s recommendations are especially worth your while.

The top 250 list is the tip of the iceberg for the lists on your account. What is it you enjoy about keeping ranked lists?

It’s a compulsion. I just really enjoy making lists, ranking films by certain directors, franchises or studios. Not really useful, mostly just fun to do! And I’m not the only one, it seems. Although, of course, lists like the Letterboxd Top 250 will always be an inspiration for finding well-rated films I haven’t seen yet.

Which films got you hooked on cinema?

I do have a few titles that were important in terms of my film-watching development. Films like Terminator 2: Judgment Day and Jurassic Park came out when I was an early teenager and those were the ones luring me to the cinema to see and experience things you just couldn’t in the real world, both with groundbreaking special effects—I’m a sucker for those. Not much later, titles like The Shawshank Redemption and Pulp Fiction were popular and that’s probably around the time that IMDb’s list got my attention. That top 250 gets a lot of criticism, but the overall quality is fine and for me it was the perfect step in broadening my film-watching.

So, for a long time I watched a lot of films on that list and went to the cinema for your usual blockbusters, probably until Letterboxd arrived. That’s when I started watching the artsier stuff and foreign cinema of which, of course, all classics eluded me up till then. It was films like Seven Samurai, Persona and Werckmeister Harmonies that sparked that particular period. Now I just watch everything that comes my way that seems interesting or entertaining, from the new Marvel instalment to classic Godard.

Tell us about the one and only movie you’ve given a half-star.

Ha, that’s an odd one… Once there was a challenge on the site that you could ask a fellow member to pick the next ten films for them to watch. I participated once and, of course, there would be underseen gems or personal favorites on that list, but also one or two that would be almost unwatchable. In my list that was Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny. If that title alone doesn’t give away how bad it was, watching the first five minutes will.

In your opinion, what’s the most underrated film according to Letterboxd average ratings?

One that comes to mind, which was in the top 250 once, but has dropped substantially in the last few years, is Gravity. I also have a list where I collect all the films that were once in Letterboxd’s top 250 and it’s at the very bottom there. For me, seeing that film in a theater is what cinema is all about—finding new ways to immerse your audience into a movie experience they have never had before. Oh, did I mention I’m a sucker for special effects?

Dave is a sucker for special effects, including those in Alfonso Cuarón‘s ‘Gravity’ (2013).

As a Dutchman, please educate us: what are the greatest Dutch films people should see?

The Netherlands doesn’t really have a thriving movie industry that brings its films across borders. If I have to give the essential tip, it would be Spoorloos, which was remade starring Kiefer Sutherland and Sandra Bullock and was not half as good. Other than that I would recommend Paul Verhoeven’s early work, such as Soldaat van Oranje and Turks Fruit, and the two Dutch films that won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, 1986’s De Aanslag and 1997’s Karakter. And to top it off, I want to mention two Dutch filmmakers worth your time, Alex van Warmerdam, director of De Noorderlingen, and Martin Koolhoven, director of Oorlogswinter.

What comfort movies are you watching whilst in quarantine? Are you working on any viewing projects?

I actually am in a viewing project at the moment. One of mine and my wife’s guilty pleasures is superhero movies! So currently we are, again, on a Marvel Cinematic Universe rewatch streak. They just provide a wonderful form of escapism and are definitely deserving of the term comfort movies. Some are better than others of course, but the perspective of rewatching The Avengers, Thor: Ragnarok or Guardians of the Galaxy after a while still tends to fill me with excitement. In a way, there’s still a bit of the twelve-year-old in me that was so thrilled to see T2 or Jurassic Park.

How do you plan on inducting your kids into the cinephile life?

Well, most important is that they just enjoy going to the movies like I did when I was young. Let’s hope we will be able to do so again in the near future. They are still young, but their access to screen time with Netflix, Disney+ and (mind-numbingly stupid clips on) YouTube is so different than the days when we were young. So having them watch some Ghibli classics is already quite a step. And then I think the rest should come naturally. If not, so be it.

Which, for you, are the most useful features on Letterboxd?

Did you know they have a list with the 250 best rated narrative feature films? That’s basically all you need to know… All kidding aside, just reading reviews once in a while by fellow members whose opinions I value is still the heart of the service to me. That and the statistics pages. And browsing other lists.

Does anyone in your real life know that your list is kind of a Letterboxd big deal?

Not really! Mostly because I don’t exactly feel that way about it. I mean: my wife knows, but other than that it’s pretty much still my pet project. To me, it’s still just a film enthusiast’s list that so happened to become the site’s official top 250. I do have to say that it is humbling to see the numbers of new followers every day—especially when Letterboxd mentions the list on her social accounts—and to realize that apparently almost 23,000 people around the globe have taken a liking to it.

Please name three other members you recommend we follow.

Fellow countryman and longtime member DirkH. He is not as active as he was before, but writes beautifully personal reviews, always with his trademark witty humor or sometimes cheeky sarcasm, not always to the liking of everyone. You all got to know Lise in the first How I Letterboxd, but I’d definitely also recommend following her other half Jonathan White. His reviews are great, he knows so much about film and is always willing to share his thoughts or answer questions. And damn, that man can rhyme. Then there’s Mook, if only for his franchise lists. Check out his MCU list, it’s my go-to place when I want to read up on anything Marvel.

Related content

Official Top 100 Documentary Feature Films

Official Top 100 Narrative Features by Women Directors

Letterboxd’s ‘Official’ Top 50 of 2020

Several of the films mentioned in this interview—Sátántangó, La Flor—are (at the time of writing) available for virtual screenings. The details are in our Art House Online list.

#letterboxd#how i letterboxd#top 250 films#letterboxd top 250#dave vis#cinephile#film lover#letterboxd members#letterboxd community

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three quotes about time/progress/development, from three things I read in the bath just now

From “A Storm Is Blowing from Paradise: Disco Elysium on the Past and Present” by Alastair Hadden

Like every CRPG before it, Disco Elysium contends that its player-character can improve with experience. Games are inherently optimistic this way: by accepting tasks and completing them, we steadily become more capable. There’s room to reshape ourselves, too; we can build ourselves better than the next cop, given time and effort and deliberation. That said, one of the game’s few middle fingers to the lineage of Dungeons & Dragons is its notion that a skill can be too developed; a detective can be too smart for their own good, too sensitive, too tough. And it’s noteworthy that almost all of the game’s Thought Cabinet projects and clothing bonuses come with debuffs and drawbacks, too. Progress requires trade-offs, the game wants to say. Everything in this world is compromised.

From “Béla Tarr Reflects on Making Seven-Hour ‘Sátántangó’ 25 Years Ago and Life as an ‘Ugly, Poor Filmmaker’”

Most films just tell the story,” he said, “action, fact, action, fact, I don’t fucking know what. For me, this is poisoning the cinema because the art form is pictures written in time.” He coughed hard between breaths, as if expel that sickness. “It’s not only a question of length,” he said, “it’s a question of heaviness. It’s a question of can you shake the people or not?”

So far as Tarr is concerned, Marvel movies aren’t the problem as much as they are the clearest symptom of a broader disease that has spread between genres. “Most shit today… they aren’t films, they’re just comics,” he said. “It’s just blub-blub-blub, a bubble of a sentence and then we go to the next section.” Forget about Netflix: “I’m just deeply sorry for somebody who is watching movies on this shit because they miss everything.”

Our problem, Tarr argued, is that most cinema leaves us stuck on the surface. “People just tell a fucking story and we believe that something is happening with us,” he said. “But nothing is happening with us. We are not really part of the story. We are just doing our time, and nobody gives a shit about what time is doing to us. It’s a huge mistake. I just did it a different way.”

From Missing Out: In Praise of the Unlived Life by Adam Phillips

Darwin showed us that everything in life is vulnerable, ephemeral and without design or God-given purpose. For disillusioned non-believers -- who, of course, pre-dated Darwin and created the conditions for his work and its reception -- belief in God (and providential design) was replaced by belief in the infinite untapped talents and ambitions of human beings (and in the limitless resources of the earth). It became the enduring project of our modern cultures of redemption -- cultures committed above all to science and progress -- to create societies in which people can realise their potential, in which “growth” and “productivity” and “opportunity” are the watchwords (it is essential to the myth of potential that scarcity is scarcely mentioned: and growth is always possible and expected).

#adam phillips#bella tarr#disco elysium#missing out#time#progress#development#films#games#philosophy#quotes

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aesthetic Strategy Within Fiction Filmmaking

Aesthetic strategy deals with the relationship between camera movement and the edit and how it can enhance the storytelling.

The average number of edits in an action films is 2000, slighltly more than a horror film as horror films rely more on tension and atmosphere. One idea of filming, used by many filmmakers to convey tension, was exemplified in Orson Wells’s ‘A Touch of Evil’. Wells used one long and continuous shot to open the film to add ambience and suspense for the audience. This was quite the feat of engineering at the time and was revolutionary. Werckmeister Harmonies is another film that uses a long continuous shot for similar effect. In fact this film has many long shots and contains only 39 edits. The beginning scene for this film, directed by Béla Tarr and Ágnes Hranitzky, also uses audio effects to emulate suspense. The film begins with a 7 minute introduction of men walking in unison and all we the viewers can hear is the footsteps, further on the men enter a hospital-like establishment and begin rushing into rooms and attacking people however it is eery as we aren't exposed to the cries of the men they are attacking, or to the shouts of the attackers despite being able to see that they are crying out. I believe this to be a very interesting way of adding suspense and a feeling of unease to the audience, an idea that I might find exciting to appropriate and adapt for my future films.

0 notes

Photo

боже мой...

My first sight of Yekaterina Golubeva was in Claire Denis’ J’ai pas sommeil (I Can’t Sleep, 1994). The film opens with the bracing image of her driving her beat-up car into Paris, cigarette held at a neat downward angle from her mouth, holding a stare of concentrated insolence. She played a young Lithuanian girl barely able to speak French who’s drawn to the city by the promise of work from a theatre director who had once seduced her.

In fact her story is almost a sideline to that of a series of murders of old ladies committed by a gang of gay men, all based on a real incident. But Golubeva’s defiant attitude and arresting looks (she wears overlarge men’s jackets with great style) created a thrilling screen presence. Particularly memorable were scenes in which she uncontrollably laughs out loud in a porno cinema, and in the midst of heavy traffic determinedly bashes the car in front being driven by the unresponsive director. Her resilience carries her through, but then as her eccentric aunt tells her, “When you don’t know how to do anything, beauty can be a real help.”

Golubeva (who usually appeared on credits as Katerina or Katia) was in fact born in St Petersburg when it was still Leningrad, and had come to attention through the films made by her husband, the Lithuanian Sharunas Bartas. First appearing in Three Days (1991), she plays one of a quartet of lost youths trying to find their way in the broken down city of Kalingrad. Bartas belongs to the minimalist, not to say miserabilist, school of filmmaking of whom the high priest is Béla Tarr. But his reliance on long takes allows the audience an intimate view of Golubeva’s extraordinary looks, her doe eyes and fleshy lips placing her somewhere between a Baltic Nastassja Kinski and a Balthus model. Seeing this film, maverick French filmmaker Leos Carax declared himself in love, switched muses from Juliette Binoche and cast Golubeva in the central female role in his ambitious and extravagant Hermann Melville adaptation, (1999).

Pola X dealt with a young author (Guillaume Depardieu) who abandons his exquisite country-chateau lifestyle to follow a mysterious, dowdily dressed young woman who claims to be his forgotten half-sister (Golubeva) into a forbidding Paris for a life in the gutter. Golubeva’s heavy accent and poverty-row attire are used to underline her presence as a symbol of suffering and the ravages of war, following in line the way she appeared in Bartas’s films. She also took part in a very explicit sex scene, played out in semi-darkness.

Her fearless attitude to self-exposure was again evident in Bruno Dumont’s misfire of a road movie Twenty Nine Palms (2005), in which she played one half of an ill-matched couple driving through the Californian desert on a journey into appalling violence. Dumont has said he cast Golubeva because she was so much the character, who in his eyes was a wildly temperamental young woman with a slight grasp of French and even less of English, and whose mood swings made her the girlfriend from hell. While gallantly performing scenes of highly vocal sex, nevertheless she seemed perhaps to be revealing how unhappy she was as a foreign actress playing out the fantasies of very singular French male directors.

Claire Denis cast Golubeva again in The Intruder (2005), as the mysterious woman who facilitates the black-market heart transplant of the film’s central character. Once more she was smoking cigarettes meaningfully and remaining apart from everyone else, but at least Denis allowed her to express humour and illuminated her beauty in a gentler fashion.

However, her fate was usually to be asked to perform roles that played more on her tortured, mournful side. From what little is known publicly of Golubeva’s private life, her move to Paris was never fully resolved. She had three children (the last of whom is being raised by Carax), and her death, which is rumoured to have been by her own hand, came only at the age of 44. But like a latter-day Louise Brooks, her iconic image will forever remain alive with us on the screen.

-David Thompson

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The tao of cinema

In France in the 1950s, it was completely normal for a cinephile to turn into a film critic and/or a filmmaker. Nowadays, however, professional opportunities in cinema are getting more and more limited, so cinephiles take alternative routes – for example, the last few years saw the rise of numerous VoD initiatives around the globe. One of them, tao films, has a very interesting story, as it was crowd-funded and launched by Nadin Mai who is a scholar and writer, known for her blog The Art(s) of Slow Cinema. See what she has to say about her beautiful and brave initiative in an interview with our editor Yoana Pavlova.

Yoana Pavlova: You have been championing the cause of slow cinema as a writer for years, where did the VoD idea come from? Did you feel like your blog has reached a critical mass of readers who would easily turn into viewers, or it was rather an urge to take things in your own hands?

Nadin Mai: The starting point for the VoD was a film I had received almost at the beginning of my work on The Art(s) of Slow Cinema. Zhengfan Yang sent me a screener for his film DISTANT / YUAN FANG (2013), which contains a mere 13 takes over the course of almost ninety minutes. It was a wonderful film, but I had not heard about the director at all up to that point.

I wrote about the film on my blog and published an interview with Zhengfan, after which I received many other films by directors who were struggling to find an audience for their films. They hoped The Art(s) of Slow Cinema could generate exposure. And it did. Viewers began to email me over the years to ask where they could see the films I had been reviewing. It has become pretty easy to access films by Béla Tarr, Tsai Ming-liang, Albert Serra, even increasingly by Lav Diaz. But what about those unknown, very young directors from around the world who had contacted me?

That was the beginning of tao films . It is an attempt at bringing directors and viewers together. It was a strike of luck, if you want to see it this way. Or maybe it wasn’t. Somehow I think that it was a natural development. Throughout my PhD research and my work on my blog I had noticed the demand for slow films. I am not even speaking of a great demand. tao films is and will remain a niche project for a niche market. But I find it important that talented filmmakers have the opportunity to show their films, and that viewers are given the chance to see those films.

YP: As we recently exchanged on Facebook on the topic of female film critics and the way the industry treats them (us), I would like to ask you also to what degree your decision to change the course of your career came from the experience of being a woman who wants to say something different about cinema, or to make a difference in cinema

NM: That is a very good question, and a timely one, as I never bothered about this male-female divide until I entered the PhD, and saw and felt just how little female academics are valued in new, emerging subjects (and surely in all other fields, too).

When I started my research into slow cinema in 2010, and began serious work on it in 2012, the subject was still low-key in scholarship. There were plenty blog posts and forum entries on slow films or slow-film directors, but academia was pretty slow (fitting choice of words here!) in picking up the subject. I have done a lot to advance the field through my blog.

Now, five years later, you find a lot of material on slow cinema in academia, but you won’t find my name anywhere. I have written about the subject on my blog from new and fresh angles but have been rejected by journal and book editors, who then merely recycled old, already known material instead of advancing the subject. Slow Cinema scholarship is a territory for male scholars who only quote one another. You find the same names wherever you go. I have come across two male scholars who took my work and presented it as theirs, without so much of a hint at where the material is really from. My work is out there, just not my name, and this is incredibly frustrating. Five years, and zero acknowledgment in academia. Absolutely zero. I am invisible.

You are right, I changed tracks in parts because of this. My work was cherished and welcomed by the “ordinary” people. They were grateful, got in touch, and I had wonderful and insightful discussions about the experience of slow cinema with my readers, something I had never experienced in academia. I am not in for the money, or for becoming a Professor of Slow Cinema at some university. But a little gratitude for my work would be nice, or would have been nice. I now focus on where my work can make a difference, and this is with tao films.

YP: Slow cinema is usually being associated with a very particular cinema-going culture, with the eventization of festivals and exhibition spaces. How do you think home viewing might change our approach to slow cinema? What would happen if we no longer consider it high-art and appropriate it in our everyday life?

NM: I would think that it is wrong to consider slow films as festival films only. Of course, you find many of them at festivals. But to me, there is another side to this, and this is the fact that only a minority of the viewers attends festivals. One could argue that especially the major festivals always have a high attendance. This is true. However, who are those festival goers? I would say that the majority are locals, or those who have the money to travel around the globe to attend film festivals. We must not forget that festivals are not cheap. I went to Locarno in 2014 and it broke my bank. The Berlinale in 2015 was very expensive even though I had free accommodation at my sister’s.

The issue with festivals is that a lot of them are for a selected circle of people, namely those with money. I do not want to say that festivals should be cheaper, more accessible, etc. I am merely stating a fact. Festivals cost money, that goes for everyone involved. So unless you have the money to travel around, you have to hope that a film you are dying to see comes to a festival near you. This waiting game is usually not very successful. So yes, slow films are shown at festivals, but who sees them? How many viewers does the average slow film – I am not speaking of films by the big directors like Tarr and Diaz – have at a festival?

I am aware that home viewing is not ideal. Film needs to be experienced on a big screen. I find that this is even more true when it comes to slow films, because the combination of a big screen and a dark room facilitates contemplation. But I believe that, for now, home viewing is the future for the next generation of slow-film directors. I hope that I can revise this statement in a couple of years, because I think that the films should be watched in a different environment. At the same time, distributors and exhibitors are still shying away from showing films that may not make the big bucks. But, you know, this is not only a debate about the economics of cinema, it also has a lot to do with ourselves and what we think cinema should be like.

YP: The majority of VoD channels that appeared recently (and enjoyed certain English-language publicity) are based in the US, mostly in New York, whereas EU seems to offer a huge variety of films, yet the market feels over-regulated. In France, for example, where we both happen to live right now, there is this public understanding that the state must fund everything related to arts and culture, but at the same time, as we know, these mechanisms are sluggish and demand good connections with the establishment. What is your take on this matter? Is this why you decided to resort to crowd-funding for tao films?

NM: I went for crowd-funding for a very simple reason: if it is difficult to have slow films shown anywhere (because they are too slow or too “boring”), then it would be difficult to find someone external to invest in this project. tao films was always meant to be a platform carried by filmmakers and viewers alike. I wanted these two groups of people to make this project happen, because it meant that I already had an audience for my films. If you help financing a slow-film VoD, you will definitely drop by and see a couple of films in future. If I had external funding and set up the platform just like this, I would have had little idea about the possible (moral) support of a slow film VoD out there. For me, crowd-funding was a more solid gathering of statistics, in a way, of how large the interest in a project like this is.

Another aspect that was important to me was that I wanted to be independent. Independent in two ways: an external funder can, because s/he invests money in your project, demand changes to your work. I wanted to avoid this. Again, tao films is a platform for filmmakers and viewers. They carry the platform, and I will try my best to protect this approach. Second, I see a lot of VoD platforms which are dependent on regular funding from culture ministries. We know that when governments need money, they cut it from the arts first. VoDs which run on government funding always have to worry that they will not make it into the next year. I do not know whether you have read the news that Trump is rumored to eliminate the National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities. This is only the most recent example that shows that if you have external funding, your work, your project, your baby, becomes a ball in a political match between parties. I didn’t and still don't want this to happen to tao films.

YP: As someone who often advocates about the importance of web 2.0 in the work of critics and researchers, I face plenty of skepticism, however, it is undeniable that social media is crucial in crowd-funding campaigns. What was your experience throughout the process?

NM: I am not sure I could have managed the crowd-funding campaign without social media. I have to admit that social media, especially Facebook, stresses me out sometimes, and I need a break from time to time, where I shut down everything and just take it slow instead. But the truth is that if you do work like I do for tao films, for example, you are dependent on social media. Our viewers sit in all corners of the world. How would I reach them and bring them together if not with social media?

YP: How difficult was the technical part in setting up tao films as a fully working website and VoD service?

NM: I cannot tell you much about the technical parts behind tao films. My brother designed the website from scratch. He is an IT expert and worked for months and months on getting everything right. We have our own player on the website, because there are so many hacks now on how to grab films from Vimeo and YouTube. We could not use those players if we wanted to make the films we show a little safer from pirates. It was not easy, I can tell you this much, and I am very grateful for my brother’s work. People are enjoying the site and the films so far, so that is a good thing!

YP: Could you please elaborate on the first selected titles, what was your curatorial approach?

NM: I wanted tao films to offer films which share certain themes. For some reason, I could not find one for the first season. Maybe I tried too much. I knew that Scott Barley’s SLEEP HAS HER HOUSE (2016) needed to be in the first season, because he had just finished the film and we wanted to offer a world premiere. Then I went by personal preference, and thought that I should just offer a mix of films for the first season. It turned out that my laissez-faire attitude brought together six films which deal with memory in one way or another. I found it interesting just how different the approaches were.

You have one film that has no dialogue at all, the images are experimental, and you have to find your way through it (Scott Barley’s SLEEP HAS HER HOUSE). The opposite is METROPOLE (2015) by Ozal Emier and Virginie Le Borgne, in which a protagonist, a man, having emigrated, is haunted by his past, speaks on camera about it. We have a character we can identify with, we can see and feel his suffering. Sorayos Prapapan, a director from Thailand, does not allow us this access in A SOUVENIR FROM SWITZERLAND / KONG FAK JAK SWITZERLAND (2015). We hear the story of an Afghan filmmaker-turned-refugee through a voice-over. What is this "souvenir"? The memory of the director's encounter with his friend who is now a refugee? Or the drink Sorayos brought home for his friend? CENTAUR (2016) by Aleksandra Niemczyk, mentored by Béla Tarr, is perhaps not straight-forward a memory piece, but in her interview Aleksandra described the film as way to deal with her grandpa's memories of suffering from polio. Film becomes a way to "imagine" this difficult period, it is a means to voice her grandpa's suffering. And then there is OSMOSIS (2016) by Greek director Nasos Karabelas, of which I never quiet know what to say. The philosophical voice-over is heavy. It makes you think, it makes you dig into your past, our past. Again, this might not be overt at the beginning, and perhaps you need a while to see it just as I did. Perhaps, Liryc de la Cruz’s film THE EBB OF FORGETTING / SA PAGITAN NG PAGDALAW AT PAGLIMOT (2015) is the film that deals most evidently with the subject of memory, very much in the vein of Lav Diaz.

YP: When most VoD platforms appear, they try to create a shared cinephilia space for viewers, i.e. publish original features, interviews, and audiovisual essays to accompany the films. In the case of tao films, that space was there before the films. How do you see your role now, as a writer / critic / researcher?

NM: In a way, nothing is changing with tao films. I see my role still as a writer and researcher. All films we offer will be reviewed on The Art(s) of Slow Cinema in order to increase their exposure and attract more viewers. We do offer interviews with our directors on the tao films website already, and a brief introduction. But main reviews will appear on my blog. We want to keep the actual VoD website as simple and as zen as possible. No clutter! You are right, the space was there beforehand, and this is, I believe, what makes tao films a comparative success. I built up an audience over the last five years. The blog is still going strong with almost 4 000 views a month. I cannot drop it but will instead merge it with tao films. The blog is supposed to move later on and be integrated into the website. That was the original idea. Then again, who knows what will happen?

YP: Could you please tell me a bit about the first weeks of the service since the start on January 1st, the feedback you have received so far, your professional plans for the future?

NM: I am happy to say that we have almost 200 registered viewers, which, I think, is a success given that we are tending to a niche. Our viewers come from several countries, from the US, from Europe, and from Asia. I am very happy about that. As far as I can see, our platform makes for good weekend entertainment. We have more sales between Friday and Sunday than during the rest of the week. That means people take their time for the films, which is good. The feedback has been good so far. People enjoy the selection and the fact that they can finally see films that are not shown in their local cinemas. We have a few special themes planned, such as a focus on film.factory or a special on women directors. I hope people will join us on our slow way to slow film :)

#Nadin Mai#tao films#VoD#The Art(s) of Slow Cinema#crowd-funding#Locarno FF#Pardo#Berlinale#Donald Trump#film.factory#Béla Tarr#Lav Diaz#Zhengfan Yang#Distant#Scott Barley#Sleep Has Her House#Ozal Emier#Virginie Le Borgne#Metropole#Sorayos Prapapan#A Souvenir from Switzerland#Aleksandra Niemczyk#Centaur#Nasos Karabelas#Osmosis#Liryc de la Cruz#The Ebb of Forgetting#interview#Yoana Pavlova

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

INTERVIEW - BIENNALE COLLEGE - EMRE YEKSAN

By András Heilig (pics © Diego Aparicio)

Emre Yeksan, director of The Gulf, now presents his second feature, Yuva, at the Venice Film Festival. The entire film is set in a forest, and it plays a role just as important as the two brothers the story revolves around. The lack of spoken word is balanced with the beautiful images and composition, giving us the space and time to deliver meaning into the complex methaphores, that can either work in a spiritual or in a political way. Yuva is also one of the three selected films of this year’s Biennale College project.

Let’s start with the title. What does Yuva stand for?

In the beginning, we wanted to use the English version, ‘Home’, but the Turkish meaning is a little more complicated than that. ‘Yuva’ not only means home, but also nest or den. It is mostly used for animals but can also describe the feeling of home. ‘Home’ was too direct and evoked architectural associations, so we ended up using ‘Yuva’ as an enigmatic title for the film.

Watching the movie, it seemed that civilization was the villain. Do you agree with that? And if so, do you think that we can have hope for civilization?

It’s not civilization as a concept. Civilization can embrace a collaboration with nature. It is rather the late-capitalist society that appears as the antagonist in the film, in the form of an authoritarian force. It can be a government, a corporation etc. There is always a brute force we must fight against, I think. We can fight in the name of nature as we fight for other people, for other living beings. However, it’s kind of an arrogant thing to do. The protagonist is unique in the sense that he is being idealistic. He tries to be a part of nature, but on the other hand is arrogant enough to think that he alone can be its savior.

Can we read the film as a political statement?

Yes.

The protaginsts of the film are going through certain processes; they follow, let’s say, certain rituals. Why is this? What is the importance of ritualization?

These repetitive gestures transmit knowledge. Not in a formalized way but in a sensorial or insightful way. We learn about how things are done from our parents, from elders, from watching other people. And sometimes we learn things that we don’t know how we ended up learning. For example, we know how to open a door. These gestures carry knowledge, but not in the form of theory or in the form of formulated knowledge, such as modern positivist knowledge. Realizing that we have learnt something is a revelation for ourselves. For me thats the importance of rituals.

I don’t believe in the duality of body and spirit. I believe that they are the same thing, they work in the same way within the same entity. Through rituals we transmit this non-duality to one another. We can think of it as something spiritual or we can think it’s because of our history as animals. Animals learn in the same way.

Can you give us your own interpretation of the cave? How does it work? What is happening there?

The cave is a different place for everybody. It was different for the Woman, for Veysel and Hasan. Everybody finds their own space inside of it. So, it’s a place where we retreat to ourselves. Working and writing is also a moment when you go into your cave. When you retreat into yourself, when you face your fears, your lack of confidence, when you fight your demons and you get better.

Maybe it’s the place where a person feels the loneliest.

Using the 4:3 aspect ratio is kind of a fashionable approach in today’s filmmaking. What motivated your choice to use it?

I’ve envisioned this film in this format since the beginning. We had some pictures taken and we saw that the forest is rather vertical space. When we used a wider format and tried to fix it on a human being, we lost a lot of the forest in the background. You mostly have the trunks but not the perspective of the forest. The forest is a character in the story, so we found this to be the best format. Also, this is a story that starts with a character and continues with a second one; this 4:3 format is very good for films with few characters; the character’s face fills the screen.

This is kind of a cheeky question. The dancing sequence at the end is part of the film or not?

[laughter] For me it’s in between. It depends on how the viewer wants to read it. I like this kind of dramaturgy or mise en scene in film which isn’t meant to lead you somewhere. You must derive the meaning for yourself. When I talk to people about it, I find that everyone has their own understanding of it. Within the film or outside the film: both can work. It can come across as a statement that this is nothing but a film. But it can also convey the meaning that even if they died, their journey continues.

Who is your ideal? Who are the directors you want to follow?

Among my many influences, there are three names that come up often as my inspiration: Lucretia Martel, Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Clair Denis. When I have a new idea, I check their works to find my path in developing the film. (I also like the films of Béla Tarr)

0 notes

Photo

-silhouette of Béla Tarr, from Tarr Béla, I Used to Be a Filmmaker(2013) dir. Jean-Marc Lamoure

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tarr Béla, I Used to Be a Filmmaker (Jean-Marc Lamoure, 2013)

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I was wondering, where did you fins "Béla Tarr: I used to be a filmmaker"? I've been searching for it but can't find it anywhere and I really want to watch it...

It’s on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Tarr-Bela-Used-Be-Filmmaker/dp/B00MBAYLNE/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1538677498&sr=8-1&keywords=i+used+to+be+a+filmmaker

Otherwise private trackers like Passthepopcorn or Karagarga ;)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“LFS is just this mixture of people that brings this energy which holds in its center cinema itself” - Jiajun (Oscar) Zhang

Jiajun (Oscar) Zhang (above third left) graduated from the MAF program this year and has recently taken part in the Asian Film Academy, which takes place every year in Busan in South Korea.

AFA, similar to the Berlinale Talent Campus and Serial Eyes programmes, is “an educational program hosted by Busan International Film Festival, Busan Film Commission and GKL Foundation to foster young Asian talents and build their networks throughout Asia.” Over the past 12 years, 289 alumni from 31 countries have taken part, along with world-renowned directors such as Béla Tarr, Jia Zhangke, Hou Hsiao-hsien and Lee Chang Dong, participating in a program which includes short film production, workshops and special lectures. The two short films completed by attendees are then officially presented at the Busan International Film Festival.

We spoke to Oscar having just completed the programme to find out how he found his way to London Film School, what he learnt from his time here and at AFA, and where he’s headed to next…

Sophie McVeigh: Could you tell me a little bit about your background before coming to LFS?

Oscar Zhang: I was born in China, in Shanghai. It’s a big city and I was interested in cinema since I was 14,15 years old. As a lonely teenager I naturally got drawn into cinema, like a lot of us! Then I studied at university, a media subject, and I started making short films at that point. That got me started... travelling to small festivals around the world, and I thought, wow, this is really a career that I could do. After that I started working as a commercial director, to make a living for about two years. I got really tired of it, so I thought maybe it was time to stop. By that time, I was working with a bunch of guys who had studied in London and came back to China, and they told me there was a good film school called the London Film School. They said if I wanted a change of atmosphere I should consider going there.

S.M: What made you want to come to Britain, over say the US or schools in Asia?

O.Z: I guess because a lot of my friends, they’d graduated from UK universities and they came back and worked in the industry. I was living with a bunch of older boys at the age of 18, 19, and they were telling me about life in the UK every day, so it seemed natural for me to go there.

S.M: How did you find adapting to life in London when you first arrived?

O.Z: It’s super different to Shanghai, the system and how everything works, and my English wasn’t perfect when I arrived. I couldn’t understand all of the classes at first. That’s what I most regret because I realised the stuff I missed could have been very important! But later on, it got better and better and I started to get the most out of it, lecture-wise and making friends.

S.M: Did you always want to specialise in directing?

O.Z: So, at LFS we have six terms and we make films each term, but you have to pitch to be a director. I was kind of lucky, I did five times directing out of six terms. I think I optimised my chances in school as a director! So, I think I can call myself a major in directing (laughs). I was always writing my own scripts too for all those terms.

S.M: Can you tell us a bit about your graduation film, which has been chosen to screen in the Showcase in December?

O.Z: It’s a film that’s actually inspired by one of my colleagues in my class. She’s from Taiwan and she’d been living in Shanghai all her life. The political situation between Taiwan and mainland China is kind of sensitive. There’s actually 800,000 immigrants in my city but they don’t have a proper identity. So, what I heard from this girl, she was complaining to me one day as we were walking in Covent Garden, just chatting. She said, “I don’t know what to do when I go back to China, because I grew up there, but they don’t really want me for any jobs when they see my identity as a Taiwanese. It’s hard for me to get a working certificate, but if I go back to Taipei I don’t have any friends there so it’s gonna be hard as well. I’m really in a state of limbo.” That inspired me to make a film focused on a character like that. So, my main character is a teenage Taiwanese girl working in Shanghai. She’s living with her family and there’s an emotional story around the relationship between her, a teacher and a younger boy. This was the film I submitted to get accepted to the AFA (Asian Film Academy).

S.M: Can you tell us a bit more about that?

O.Z: It’s a selective group that takes part for one month and it’s like a platform. You have the most prestigious directors in Asia. All the candidates are from Asian countries, it’s one or two candidates from each country, and they select 24 people and you make two short films there and attend a bunch of lectures. They will be in this sort of Busan Film Festival family from that moment, so you get to be part of it and to submit your film later. There’s also a pitching session to pitch our first feature script idea. Luckily, I got the first prize for that so they’re sending me to LA next year for further pitches to producers and stuff like that. The film I pitched was one of the ideas that I submitted with my application to LFS. It was an idea that had been in my head for a long time which focuses on contemporary Chinese society issues. One thing I liked the most about the experience was that it’s this dream like place, that gathers all the filmmakers from across the region. And the moment you leave the platform after spending almost a month with all these people sharing the same kind of dream… at one point, I felt like all of these people had been like a family before, you know - a filmmakers’ family just like the people I met at LFS. We belonged to the same unknown planet, and were sent to this world to create something. But then, after we die or before we were born, we would be always together, as a family, and we would meet each other in that place after death, a place that belongs to all worthy filmmakers. That’s the kind of crazy dream idea I got after this emotional experience there!

S[4] .M: Are the issues in contemporary Chinese society something that you’re focusing on at the moment in your filmmaking?

O.Z: Yeah, in a way I am doing that. But, at the same time, as I look at all the films that I’ve done, including the ones at LFS, I realise that most of them aren’t really about social issues that much. They are in the background, but I was mainly interested in relationships between people rather than the hardcore social issues.

S.M: What did you like about living in London?

O.Z: It was just party after party (laughs). I met a lot of people that I thought were strange at first, in terms of my culture, but as it went on I realised they were very interesting and inspiring. Not just people from Britain, actually, I was influenced by people from all over the world. It’s just this mixture of people that brings this energy which holds in its centre cinema itself. This kind of turned me into a hardcore cinephile! That was the most life-changing event that’s ever happened to me. And the BFI (British Film Institute) as well. The BFI is the place me and my cohort mostly slept (laughs). We went there very early in the morning and we came out after the last screening finished, when we didn’t have classes. You don’t have to buy tickets, it’s free. Me and my colleague actually collected the tickets and there were hundreds of them. I think we made our school fees back! The films they screened there were invaluable.

S.M: What was the most important thing that LFS taught you?

O.Z: I think I’d divide it into two parts. The tutors that I encountered were two or three of the most important in my life. They were there back in the day of the early British film movement. Their experience, their knowledge, the insights they gave me – they gave me a lot, and they opened me up, to put it simply. For example, one of the tutors would show Westerns films, like the films of John Ford that I would never have touched because Westerns are nothing to do with my culture, I was super not interested in Westerns! But he analysed the film and the way he turned it into a useful strategy for us to learn as directors was just very precious for me. The tutors were great. The other part is that I learnt the most from my colleagues at the school. I had the luck to have the best cohort I’ve ever seen! We were a big bunch, 36 or something of us from 30 different countries, but strangely we bonded very well together. They were all very passionate people. We would go for drinks and not stop talking about film. When we graduated some of us were still working together and making films together. After leaving I’ve visited three different countries to meet LFS colleagues. I guess I learnt my life’s lesson from these people.

S.M: Do you think that international influence has had an effect on your filmmaking?

O.Z: Absolutely. One of my colleagues, Keenen and I were talking about what the next wave is going to be – you know there was French New Wave, Italian Neo-Realism, all this. So, we were thinking, what’s gonna be the next one? And he told me what’s going to happen is that it’s not going to be regional waves anymore, it’s going to be a global one. As you can see, how the internet brings us together, how this school brings us together. We are really becoming a world family, this film society. And as we experienced in the school, when I make a film I would have 15 non-Chinese people on-board and we worked perfectly fine. So that enabled me to think about being a global filmmaker. My next feature project, I was thinking it will be collaborating in Korea, I’ve got something else that I’ll shoot in London, another in Malaysia… so that’s what the school brought me, the courage to become a filmmaker that will make films globally.

S.M: What are your plans for the coming year?

O.Z: Me and some other colleagues have decided to meet regularly somewhere and make small independent film that really don’t cost very much. The next one we’re going to do is in Seoul, South Korea, next year. At the same time, I will work on scripts both for indie films and the Chinese film industry. I’ll be in the US for a year at some point. At the moment, I’m really into super low-budget shoots. Anywhere I go, I have my camera and sound-recording equipment. We’ve got a cohort in the States, so we’ve been talking about working together there.

S.M: What advice would you give to someone who’s been accepted to LFS, to help them make the most of their time here?

O.Z: I think the reason why we were a very conscious cohort was that we had good tutors who told us the truth and kept us sober. My most critical advice is, in any circumstance, be aware of your work and always reflect on that. We are here in film school to learn. Open your heart to a lot of things. And also, don’t rush your career. In my experience it’s better to wait and perfect your skills than rush into stuff.

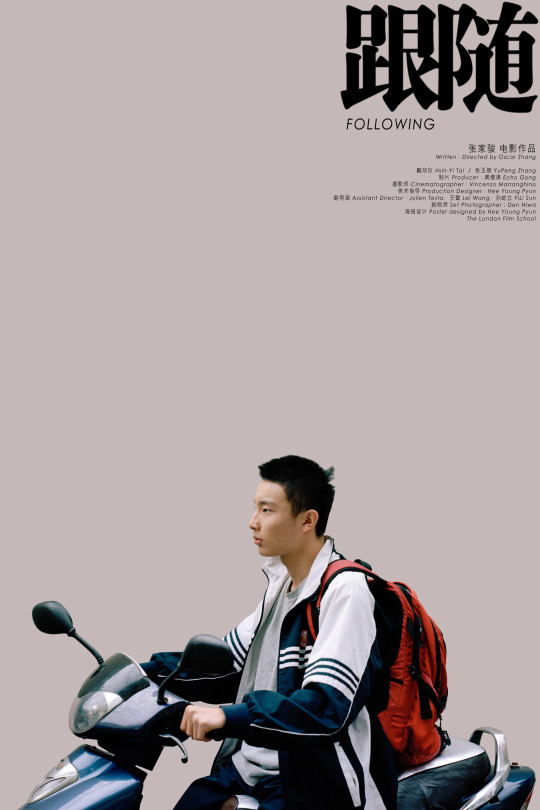

FOLLOWING (27:11 mins, 2017)

Writer-Director: Zhang, Jiajun

Producer: Gong, Yingqing

Production Designer: Pyun, Heeyoung

Cinematographer: Marranghino, Vincenzo

Assistant Director: Testa, Julien

Camera Assistant: Walsh, Paisley

Sound Editor: Chim, Terence

Interview: Sophie McVeigh | Photos: Annual Show by Katie Garner, Group Selfie by Putri Purnama Sugua, Film Poster of FOLLOWING

#bfi#french new wave#italian neo-realism#korean film#filmschool#busan film festival#afa#asian film academy#bela tarr#jia zhangke#hou hsiao-hsien#lee chang dong#chinese film market#hollywood#londonfilmschool#film directing#westerns#international

0 notes

Photo

Béla Tarr’s The Turin Horse

When I first watched The Turnin Horse, I really appreciated the cinematographic beauty that it held. Though it was a slow moving film with little dialogue, I appreciated its beauty and its heavily emotion driven story. The acting was a hugely important part of this film; the characters portrayed a lifetime of hardship and suffering in their faces, without telling the audience about it. The horse is a great character as well; the way the horse and the father struggle through the storm in the beggining of the film reallyn gives it a dramatic opening, that, despite its length, kept me watching. The camera seemed to be in love with the details of the movement of the horse and carriage. The black and white 35 mm film along with the dramatic and dark sounding music gave the film a desolate yet epic feel. Though the main pace of the lives of the father and daughter are slow, we see some outside characters that show up into their lives very suddenly. The first man who visits them stops by asking for some brandy. He proceeds to talk about how the village where he normally gets brandy has disappeared, and proceeds to have a one sided philosophical conversation about the nature of humans and their doom. At the end of his spiel, the father says something along the lines of "that's bullshit" and the man grumbles to himself and leaves. This encounter plays along with the theme of the film, a sort of reverse of Genesis as Taar explained to us. We also see a band of gypsies that taunt the father and daughter, perhaps representing the foolishness of man. Soon after this, their well runs dry and though they try to leave, they're forced to return shortly afterward. We see darkness and quiet descend over them, and they aren't able to light a lamp. At the time I wasn't sure what this represented or what was happening in the story, but after Taar explained the reverse Genesis theme it made a lot of sense and I really appreciated the way the two quietly faded out of existence. Talking with Bela Taar about his film definitely made me appreciate it more and understand it better. He was an interesting and blunt man who clearly had a vast experience of film. Talking about his younger days he seemed to have overcome a lot of hardship himself. It's clear that by giving his actors a lot of freedom and not much direction other than where to go and what to do, he achieves a very real and intense performance, particularly by the two actors in the Turnin Horse. The reason he gave for making the images so beautiful despite the intense poverty the characters were clearly living through, was that he didn't want to touch or take away human dignity and beauty. He also said that he believed that filmmaking was for the people and should be about their struggles, which I really appreciated.

~ maria

0 notes