#Steven Sloman

Text

‘‘This is the essence of the illusion of explanatory depth. Before trying to explain something, people feel they have a reasonable level of understanding; after explaining, they don’t.’’

- Steven Sloman, Philip Fernbach

1 note

·

View note

Text

Steven Sloman - The Knowledge Illusion, Ch. 11

The discovery that they don’t understand often comes as a shock to the students who believe they read carefully. What shocks students is how poorly they do on comprehension tests. They study and study and feel like they have achieved a deep understanding, yet they can’t answer basic questions about the material. This phenomenon is so common that it has a name, the illusion of comprehension, reminiscent of the illusion of explanatory depth.

The illusion of comprehension arises because people confuse understanding with familiarity or recognition.

Comprehension requires processing text with some care and effort, in a deliberate manner. It requires thinking about the author’s intention. This apparently isn’t obvious to everyone. Many students confuse studying with light reading. Learning requires breaking common habits by processing information more deeply.

Besides, the idea that education should increase intellectual independence is a very narrow view of learning. It ignores the fact that knowledge depends on others. Learning therefore isn’t just about developing new knowledge and skills. It’s also about learning to collaborate with others, recognizing what knowledge we have to offer and what gaps we must rely on others to help us fill. We also have to learn how to make use of others’ knowledge and skills. In fact, that’s the key to success

0 notes

Text

Does Evidence Shape Our Views? Academic Minute

Does Evidence Shape Our Views? Academic Minute

Today on the Academic Minute, part of Brown University Week: Steven Sloman, professor of cognitive, linguistic and psychological sciences, explores if the people around us are the key to changing minds. Learn more about the Academic Minute here.

Is this diversity newsletter?:

Hide by line?:

Disable left side advertisement?:

Is this Career Advice newsletter?:

Trending:

Live…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Does Evidence Shape Our Views? Academic Minute

Does Evidence Shape Our Views? Academic Minute

Today on the Academic Minute, part of Brown University Week: Steven Sloman, professor of cognitive, linguistic and psychological sciences, explores if the people around us are the key to changing minds. Learn more about the Academic Minute here.

Is this diversity newsletter?:

Hide by line?:

Disable left side advertisement?:

Is this Career Advice newsletter?:

Trending:

Live…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Stephen Dubner:

“Easy question first: How do you get someone to change their mind?”

Steven Sloman:

“Well, first of all, there’s no silver bullet. It’s really hard.

But if you’re going to try, the first thing you should do is try to get them to change their own minds.

And you do that by simply asking them to assume your perspective and explain why you might be right.

If you can get people to step outside themselves and think about the issue — not even necessarily from your perspective, but from an objective perspective, from one that is detached from their own interests — people learn a lot.

So, given how hard it is for people to assume other people’s perspectives, you can see why I started my answer by saying it’s very hard.”

Stephen Dubner:

“One experiment Sloman has done is asking people to explain — not reason, as he pointed out, but to actually explain, at the nuts-and-bolts level — how something works.”

Steven Sloman:

“People don’t really like to engage in the kind of mechanistic analysis required for a causal explanation. (…)

And then they said, “Okay, how does it work? Explain in as much detail as you can how it works.”

And people struggled and struggled and realized they couldn’t.

And so when they were again asked how well they understood, their judgments tended to be lower.

In other words, people themselves admitted that they had been living in this illusion, that they understood how these things worked, when, in fact, they don’t.

We think the source of the illusion is that people fail to distinguish what they know from what others know.

We’re constantly depending on other people, and the actual processing that goes on is distributed among people in our community.

It’s as if the sense of understanding is contagious. When other people understand, you feel like you understand. (…)

I see the mind as something that’s shared with other people. I think the mind is actually something that exists within a community and not within a skull.

And so, when you’re changing your mind you’re doing one of two things: you’re either dissociating yourself from your community — and that’s really hard and not necessarily good for you — or you have to change the mind of the entire community.

And is that important? Well, the closer we are to truth, the more likely we are to succeed as individuals, as a species. But it’s hard.”

Source: Freakonomics Radio: 379. How to Change Your Mind

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I really do believe that our attitudes are shaped much more by our social groups than they are by facts on the ground. We are not great reasoners. Most people don’t like to think at all, or like to think as little as possible. And by most, I mean roughly 70 percent of the population. Even the rest seem to devote a lot of their resources to justifying beliefs that they want to hold, as opposed to forming credible beliefs based only on fact. . . . Think about if you were to utter a fact that contradicted the opinions of the majority of those in your social group. You pay a price for that. If I said I voted for Trump, most of my academic colleagues would think I’m crazy. They wouldn’t talk to me. That’s how social pressure influences our epistemological commitments, and it often does it in imperceptible ways.

Steven Sloman, professor of cognitive science at Brown University, in an intervew with Vox’s Sean Illing, June 15, 2018

#Steven Sloman#interviews#quote#critical thinking#self justification#beliefs#liberal academic bias#peer pressure#Vox

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why we can't remember everything

The Knowledge Illusion

Pg. 47

"Remembering everything gets in the way of focusing on the deeper principles that allow us to recognize how a new situation resembles past situations and what kinds of actions will be effective."

Finally there is an explanation for why we cannot remember so many things, all the useless details that are difficult to memorize, why we tend to just pick out the gist of what we understood instead of remembering every word someone said or something we read.

1 note

·

View note

Text

• Humpty Dumpty Elegy 9 | five books on 🤪STUPIDITY🧠 •

I'm a real dumb bitch

It may have all started when I threw that brick up in the air as high as I could, and it landed on my head. Or when I pulled my arms into my sleeves, and faceplanted right onto a sidewalk, losing my front teeth. Maybe it was when fell down a steep gravel driveway, and though I had perfectly good arms, I still bounced my face off the ground again, leaving me with a very cool lightning bolt scar over my left eye.

Those were just a few big memorable blows I took to the head. The rest came in the form of daily bonks and pratfalls to make my friends laugh.

I can't be sure why I hit my head every day. Might have been inspired by my dad, who was a textbook case of CTE. Not only did he have endless funny stories of catastrophic head injuries, from football and bar fights, he let the people he loved slap him in the head when he was being a silly little baka, which was always.

Coulda been The Three Stooges, a show my dad revered, with Curly Howard taking hit after hit to the dome. The fact that Curly obviously died from head trauma only made him seem more like a hero to him.

Or maybe it was the constant threat of special ed classes. Which may seem designed to help us dumb kids, but in my school it was OBVIOUSLY a disciplinary gesture, not a learning resource. The teacher of the Speds was Ms. Clarke, our school's version of Ms. Trunchbull, a sadistic old witch with owl eyes. Her only job was to teach kids to stare at the floor and keep their mouths permanently shut.

Being threatened with Ms. Clarke's presence was the equivalent of being threatened with The Chokey, or Guantanamo Bay. And until the end of grade six my parents were constantly in meetings to keep me out of her arthritic bumpy old bitchass claws. In between discussions with well dressed drug dealers, trying to get me hooked on the same pills they gave to god damn Kamikaze pilots.

The stress of all that was very painful, and I think my headbanging was plain old self-harm. The dissonance of being told I'm clever by people who love me, but mentally defective by the people teaching me was a dilute form of hell. I was like, "Ah well, never going to use this brain anyway [bonk]".

Humpty Dumpty and I had remarkably similar sounding upbringings. Only difference being (aside from his lack of head trauma), he had nobody advocating on his behalf. He had weak, ignorant parents, who just wanted their broken kid fixed, and they trusted goblins to do it. He did a full sentence in The Chokey, and took the whole suite of PILLS NOBODY SHOULD FUCKING GIVE TO KIDS.

It ended in sixth grade, when a friend of mine decided to not laugh anymore. I banged my head on the desk, then looked at him, he was stonefaced. Couple more bonks, nothing. Bonk bonk bonk... arms crossed, unimpressed. I bonked till I had a headache, for nothing. The message I was getting at the time from him was, "Not funny, dude." But as an adult, I picture the look on his face and hear, "Please, please stop hurting yourself."

I stopped, thank gosh, but now here I am, the kind of guy who acts like he has mild brain damage, all the time.

And I love it! My name is a reference to my lazy mumbling mushmouth, like "gibberish" or "gobbledygook". All my favorite people have brain damage! Roseanne Barr, Roald Dahl, Alex Jones, Mike Tyson, Steve Brule, Lady Gaga, Abe Lincoln, Harriet Tubman, etc. it's a glorious club to be a member of. Next on my bucket list? Trepanation.

Around the time I threw that brick, and ate that gum off the underside of a banister, I also discovered the power of words: My friend Newfie and I were in the midst of a huge crabapple fight. We were in the middle of the street, circling each other counterclockwise, hurling crabapples, missing literally every throw, until the fronts of our t-shirts ran out of ammo. A crowd had gathered to watch, as we scrambled over the lawns to reload. Getting tired, and knowing round two would be just as pathetic, I decided to stand there and just dance as the apples flew by. With my friend getting all winded, I stood tall, pointed at my him, and boomed in my tiny little boy voice:

"Newfie! You are a PENIS TOUCHDOWN!!"

I stole the whole show. The audience (of other stupid kids) hit the ground laughing, including Newfie. And I was the neighborhood wordsmith until I moved away. Kids thought I must have some connection to the muses, to come up with something as devastating and one-of-a-kind as "penis touchdown". Nothing was more impressive than the stupidest thing I had ever said in my life.

I've always had a weird relationship with stupidity. While my family insisted that I had a big brain, I had to ask, whothafuck are they? Aren't they just obligated to say that? My grandad was my biggest advocate, but that silly bitch also accidentally put a cigarette out in my fucking ear. My dad was an R-word, and my mom, for all her booksmarts, married at least two different R-words. So what do they know? A boy must wonder.

"R" stands for "renegade" of course.

I went from the clever kid with the oversized skull (some boys called me "Epcot Kid" because my head looked like the Epcot Ball), to the dopey asshole with an oversized dented skull, to a sped kid, to "gifted", to a highschool dropout, to a line cook working beside two people with masters degrees and two-foot flames jumping off their frying pans.

Intelligence and stupidity are my greatest fascinations. It's why book #1 in this series is You Are Not So Smart. I remember my mom shouting in the car about how dumb people are, and angrily gesturing at a fumbling driver. Then at some later point, she nearly ran into a woman at a stoplight, and I saw the lady silently ranting about my mom... to her kids in the back seat.

This is the first topic that got me into psychology books. As a non-recovering stupiholic, I wanted definitive answers about what "smart" meant. Here's what I discovered about even the smartest people you know:

They are 99.9% ignorant of how the world around them functions; their memory is tiny, brutally selective, editable, and temporary; believing is seeing, 10x more than seeing is believing; they confabulate, and self-justify in a matter of milliseconds, a thousand times a day; the span and depth of their attention is as pitiful as just about anyone else's, and getting worse by the year; as objective and rational as they pretend to be, most of their decisions are inevitably swift and subjective gut intuitions. Our brain is a biased, excuse-making, faith-based, dogmatic hunk of pig shit. Show animals more respect, and don't you ever pretend you're not one. ♥

Why did experts want to put me in special ed? Not because I was much dumber than my peers. I was just a giant asshole. And they justifiably didn't like me.

Socrates said self awareness is the basis of all wisdom. And what did he know about himself? That he didn't know shit.

This month, instead of passing over "Know thyself" and "I know nothing", as clichés people tattoo on their pubis, we're going to dig in deep. So that in the future, when you say "I'm an idiot", you can say it knowledgeably. Not as a fatalistic, nihilistic, irresponsible douchebag. But as a reflective, introspective, humble ape.

• #1 The Knowledge Illusion by Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach •

Can you draw a bicycle, from memory? Try it. Doesn't have to be beautiful, just functional.

Despite the fact that many people can ride a bike, or have at least seen hundreds of them, people fuck this challenge up royally.

Maybe you've got bikes figured out. How bout the flushing mechanism in your toilet, or the clicking mechanism of a pen? It's one thing to visualize the parts in your head, or even fix it when a piece comes loose, the question is can you put them together, in a causal chain, from beginning to end, so that they work?

For as many things that you can explain in depth, there are thousands more you can't. The list of known-knowns is infinitely smaller than all the unknown-unknowns. Even the simplest man-made things you can find are products of dozens, sometimes hundreds of different clueless participants. They specialize in one tiny thing and they work all day handling vague unanalyzed information. Then they blindly pass it off to someone else, who doesn't ask questions.

Astronomers don't have to go to school to learn how to melt or polish glass into lenses, or how to magnetize iron to make a compass. And the people who professionally make these instruments rarely get paid to use them.

How does a bike work? I get on that punk and pedal. Turning and leaning are basically the same joystick. Speed keeps you upright. The wheels suck dick without air. And don't slam on the front brake alone. Done. Bikes. 🚲🚲✔

But before you go feeling all inadequate about your inability to explain everything down to the gnat's ass, relax. Nobody likes to be reminded of the "illusion of explanatory depth". The point is, unless someone asks you to manufacture bikes, you have zero reason to look into it. Even if you did track that information down, you'd only be the holder of a handful of trivia. Not necessarily more intelligence.

When asked, "do you know X?" we substitute the question in our head for a new one, and hear, "could you find out about X, if need arose?" and say "yes." When the answer to the original question is, "no" the vast majority of the time.

The truth is, though, that's perfectly fine. Because individual intelligence is overrated. Intelligence doesn't exist in any one person's head; It exists in the collective mind. Sound spooky and ethereal? It is. Plato didn't fuck around.

What about geniuses like Isaac Newton? Newton had a library of books reaching back a thousand years before him. He's the one who famously said "If I have seen further than others, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants."

What about Genghis Khan? Man ejaculated all the way to the fucking moon, and he didn't start out his career, flipping through books. But he was a central node, in an innovatively built network of highly mobile people, sharing news and oral history all over the silk road.

Most of the greats have famous quotations, begging readers of history to give their contemporaries more credit. But hell naw. In the end, complexity reduction always wins.

It's not that we're just a bunch of children who want superheroes to worship, and we're too stupid to handle all the details. Not at all. We just evolved as oral historians, without literature. The most efficient way to immortalize a person, and hold on to their contributions for generations, is to turn them into myths. Something that can spread from campfire to campfire, or troubadour to troubadour. Also, if we couldn't reduce big ideas into basic ones, we'd never have the brain power to reach beyond, and discover even bigger things.

Some people are more reflective than others. Meaning they're more likely to ask themselves whether they really understand something. They probe their own illusions of explanatory depth, and enjoy attending to details. But even the most reflective people still avoid 99% of all explanations.

We specialize, and collaborate. Like Gladwell wrote about in The Tipping Point. Nobody winds up in the history books all by themselves. You got people specialists, thing specialists, and specialist specialists. But alone none are terribly special at all.

Have you ever been subjected to the "Why?" game? Typically played by kids, the rules are simple: Ask someone a why question, and when they answer it, ask, "why?" again, and again, and again... till the person being interrogated winds up at the Big Bang, and has to either shrug or sob at all "why?"s from there on out.

This is one of the many things that Humpty hates about kids.

Part of the shock of the "Why?" game is that as we get older, we get better at overlooking complexity, worse at probing ourselves, more certain, and we forget all about our ignorance. Kids with their fresh minds effortlessly throw it all back in our face.

So what does that mean? Collective intelligence? Basically individual intelligence is the info you can personally recall, ad noodle. Collective intelligence is info you know how to find. A friend with expertise. A bookshelf. Google.

When my brother, Wednesday, and I wanted to experiment with drugs, I did 100% of the research on how to safely take them, find them, test them, etc. I learned contraindications, local laws, antidotes. I poured through best and worst case scenarios from trip reports on Erowid so I could reassure them if they're hesitant, or warn them if they're acting recklessly.

"We" know a whole lot about drugs, Brotherface, Wednesday, and I. I know, because I spent all of 2016 on Erowid, Bluelight, Reddit, WebMd, and beyond. They know because they know me, and we did drugs together. I'm their faster, more relatable Google, that loves them. I'm a big book on their shelf. That's how mavens do baby.

I forget who said it, but some dude on Sam Harris' podcast put it well when he said (roughly), "People aren't interesting based on what they say. They're interesting based on who they listen to."

Or as Aes puts it:

You fucking dorks ain't a source of the art. You can't be cooler than the places where you source all your parts. -- Aesop Rock, Dorks

Humpty Dumpty listens to bitter videogame critics on the internet, speedrun commentary, incel forums, fictional action heroes in movies or games, blackpill Doomer news, and people fighting on Twitter. That's his daily diet of mental stimulation; that's his brain. His working memory is stuffed with trash from sunup to sundown. He had two well-resourced and experienced dudes in his collective mind for more than a year, trying their hardest to redirect his focus to less nihilistic bullshit, and he absorbed not a single word from us.

This book kind of explains why. See, when we think someone is wrong, the natural, charitable view is to believe they merely have a deficit of information. So in order to change their mind, all one must do is make up for that deficit, fill them in, and they'll naturally come around.

That's called the "Deficit Model" of misunderstanding. But it's flawed the vast majority of the time. We don't believe things based on intelligence, rationality, or an understanding of causality. We believe based on emotions. Science isn't popularly believed in because intelligence is going up. Science is popular because of the glowing rectangle you're staring at right now. Its efficacy speaks for itself. Jesus didn't give us electricity and germ theory, so Jesus lost our faith.

Humpty didn't have a data deficit. He was just emotionally committed to despair. He didn't want anyone to change his mind, he just wanted people around. But we weren't looking for a decomposing nihilist. We thought we were helping someone along the same path we followed, towards emotional recovery and maturity.

He's just a pity addict. And the only way an addict recovers, is when they decide they're tired of their habit. He could have smartened up. It was always up to him. If he ever does get fed up with himself, these books will waiting patiently.

For everyone else, this book is amazing at demystifying personal intelligence, and drawing your focus to the far more important idea of collective intelligence. You don't need to be a supergenius to contribute to humanity's knowledge. Just start searching; Climb the first giant you see, and give the world a fresh look.

Don't discount your own curiosity. Don't idolize people; we're all peers. This universe can't observe itself without you. And as Isaac Asimov (tentatively) said:

The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not “Eureka!” (I found it!) but “That’s funny …”

• #2 The Forgetting Machine by Rodrigo Quian Quiroga •

If there's one thing my damaged brain does outstandingly well, it's forgetting. And no shit, that may be one of my greatest assets.

Until I get Alzheimer's, of course. But the only trick there is blowing my brains out before it really gets me. I'll wind up coming home with a grocery bag full of handguns, and look around to see the all the cupboards, drawers, and fruit bowls are full of the ones I keep forgetting to fellate.

But hey, by then, my incontinence and blabbering will be somebody else's problem, baybeee! 👨🦽👨🦼✔

It'll be their fault for not shooting me in the face anyway. Selfish prick. You want nostalgia? Diaper duty's on you.

How is there any advantage to forgetfulness? Well lets consider what happens to people who can't forget anything. "Hyperthymesia", is a rare disorder where a person can perfectly recall every single thing they've ever experienced. Pick a date, and they can walk you through it from dawn to dusk, with seemingly zero effort needed.

A disorder? Maybe that sounds awesome to you. But it comes at a huge cost. The most obvious one being the fact that some things are better left as forgotten as possible, like the sensation of breaking a bone, or kissing a sidewalk at 9 m/s. There's also the issue of how distracting such an intense perception of memory can be. And surprisingly, it destroys a person's ability to think creatively, or "platonically".

You could go to a party with 100 people there, and no matter how bad you think your memory is, I guarantee that with the right strategy, you could memorize all 100 people before the party ends. But here's the catch, you won't meet a single one of them. You have to abandon comprehension in favor of memorization. In this instance, you'd have to abandon all hope of making friends that night.

That's a key difference: Memorizing vs comprehending. Memorizing is cumbersome, and frankly it's the last thing your brain wants to do. Even if you did remember all 100 names, without any emotional salience attached to them it's only a matter of time till your recall evaporates.

Salience is like memory saliva. Just as we can't taste food in a dry mouth, we can't remember facts without answering the question, "why the fuck would I care?"

They don't seem to teach this fact to teachers. Can't tell you how many times I got in trouble with them just for asking "so what?" or "why does this matter to me or my life?". They take that question as a complete affront to the meaning of their existence. Meanwhile, if the question goes unanswered, the lesson that day goes totally unabsorbed.

Kids with "ADD" are just chronically averse to wrote memorization, in favor of comprehension. Their brains don't reward them for learning things the stupid way, so they quarrel with their rent-seeking dipshit teachers. It's not a disorder, it's a high-powered bullshit filter.

Plus, there's nothing more salient than money. Before leaving highschool, I would have told you I have the most hopeless memory of anyone you know. Then I dropped out, got a job at a Spirit Halloween store, landed an inventory manager position after the original guys suddenly quit, and by the end of the season I had the entire inventory memorized. Front and back of house, plus what's coming in the next shipment. If they had told me what my job involved up front, I would have laughed hysterically, and left waving my middle finger. But that money snuck up on me. When I left, the info vanished without a trace.

Just as Atomic Habits reminds us that there's no such thing as overcoming our laziness, this book applies that wisdom to forgetfulness. You can make it to 72 years old, receiving more than a terabyte of sensory data every single day, and by the time you reach the finish line, you'll have remembered... a generous 125mb of data. That includes all your memories, intuitions, opinions, sensations, etc. The rest, you'll have forgotten it with a zeal you never knew you had.

When you focus on memorization over comprehension, you inhibit your brains ability to boil information down, and make connections between associations.

This reducing process is where wisdom comes from. Our brain sifts through the waterfall of stimuli in our short-term working memory, picking out patterns, meaning, emotional salience, sensory data, etc. And then discards the rest when we go to bed.

Whatever is left, we work into our long-term memory by creating time and space saving "schemas". It's the quality of one's mental schemas that determines their intelligence, not the sheer volume of memorized factoids.

I think of learning sort of like duckboards. Duckboards are a clever solution to getting over swamps or quicksand. Or famously, in trench warfare, over a bombed-out wasteland. You drive wooden piles deep into the mud, which stay firmly in place. To get around, you need only two planks. First you lay plank A over two piles making a bridge, carry plank B over plank A, hook it up to the next pile, pick up plank A, carry it over plank B, make a bridge again, and so on. A plank to stand on, and a plank to reach ahead. You can go wherever the piles are driven in.

Some nerds overcomplicate things, and waste energy. They do the mental equivalent of laying down ten planks. So to move forward, they have to walk back over plank I, H, G, F, E, D, C, then B, to pick up A, then walk it aaaaall the way back to the end of J. They see all the effort as a testament to their mental horsepower, not their extreme inefficiency.

Or some deny the natural impermanence of planks in a soggy quagmire, and try nailing them to the piles. But then it rains, fungus gets to work, the mud shifts, nails rust. Suddenly the footpath they were so proud of last week has become a worthless strip of disconnected punkwood.

Embrace your forgetfulness. Pack light. Don't sink into the mud. Consider the idea that maybe you forgot something because it was truly irrelevant. Demand salience from things wishing to be remembered. And don't be too dazzled by people with powerful rote memorization skills, it's a gimmick.

Oh! And get a notebook! Jot down your good ideas. I know you're full of them. But the odds of you recalling them later is like one in one hundred. I've got a pile of banged up Moleskines and Field Notes with both the dumbest and smartest ideas I've ever come up with. Re-reading them is very fun, and always surprising.

Humpty loved to pretend like he valued all our fancy advice, but he was just too gosh darn forgetful to remember any of it. But to me, all I could hear when he claimed that was, "Yeah, that's nice. Didn't ask. Didn't listen. Don't care. Fuck you."

Just like me when I was a student. I might admire him for it if he was wasting someone else's time. But he wasted mine. Dasa nono.

• #3 Mistakes Were Made, But Not By Me by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson •

"Confabulate" from Latin, "con" meaning "together" and, "fabulari" meaning "to talk, chat"; where we get the word, "fable", and, "fabulous"

In the general sense of the word, "confabulating" describes two or more people chatting (whereas "conspiring" describes two people breathing, i.e. whispering). In the psychological sense, it means "making up stories in your head."

Some say Homo Sapiens should go by another name. As sapience might not be our defining trademark after all. Animals play games, but none are as sophisticated as ours, so perhaps "homo ludens" hits closer to the mark. Or maybe, "homo coquens" for our grasp of fire, and the ability to cook food. Or, "homo deus" for the fact that in many ways we can play god, editing genes, harnessing fission, manipulating weather, etc.

Well I say add to the list of nicknames, "homo confabulans". For the fact that we never stop telling stories. To others and most especially to ourselves.

You know why deer always get hit by cars? Because those stupid fucks aren't story tellers. If they could, they'd have turned our headlights into scary bedtime stories long ago. Bucks would clash with bumpers and fenders on their antlers like they're enchanted items of magical power.

If I split your brain in half, separating your verbal centers on the left from your visual centers on the right, then fed humorous images to your right side, your body would start laughing. However if I asked you to explain why you laughed, since the story teller in your brain wasn't there to see the joke, it makes up any random ass reason it can think of, in a matter of milliseconds. But it'll have nothing to do with what you saw.

"What's so funny? Well you scientists just ask such silly questions, they crack me up."

Nature abhors a vacuum, and our brains abhor ignorance. Its solution to gaps in perception or awareness is to simply fill them with whatever is in reach, within that day's working memory. It happens so quick, we don't feel confused at all.

Worse than uncertainty, our brains hate cognitive dissonance the most. When do we feel dissonance? Any time our thoughts, words, or actions become misaligned with each other. It's painful, and we often employ drastic measures just to squash the feeling.

It doesn't take a lot to feel it. You don't have to think something all your life, say something countless times, or repeat an action over and over, for you to keep these things consonant. A small change in behavior can wipe away a lifetime commitment to certain ideas. And a minor adjustment in personal narrative can completely transform the way you act.

You could be someone's sworn enemy for as long as you know. But if I could convince you to give them a gift, that animosity would begin to diminish. You'd think, "I don't give gifts to assholes. Maybe they're not as bad as I thought. Life would definitely be nicer with fewer enemies. God it takes so much energy. Glad I'm forgiving enough to see past our differences. We've been through so much together. Can't find a bond like ours easily." And so on.

Try it, it's called the "Benjamin Franklin effect". If you want a hater to like you, don't do them a favor, make them do you one instead. The cognitive dissonance it creates breaks down walls like roots through brickwork.

Conversely, harming someone makes you dislike them. If I could fool you into violating or insulting a random person, then asked you later what your opinion of them is, while logically your opinion should be neutral, chances are you'll have a whole story ready to go about the stranger's bad vibes to explain why you fucked them over. Because you didn't know I tricked you, and your brain won't tolerate explanatory gaps.

We all think we're decent people, doing our best. We like to think we're competent and reliable. On some level we need to believe these things, true or not. When we fuck up though, these beliefs get threatened, and the most natural response is to self-justify. It makes perfect sense from an evolutionary point of view, but it's not exactly the most sapient thing to do.

This self-justification response is lightning fast and unless we're deliberately vigilant it'll run the whole show. Counteracting it is a slow cumbersome process, but there's no such thing as being an intelligent person if you don't.

I said, "don't" not, "can't". Anyone can, it's just a question of time and effort. Unless you have some glaringly obvious neurological damage.

Some people self-justify more often than others. Strangely, it's people with the highest self-esteem who cook up the most excuses. This includes expert professionals; doctors, police, political leaders, researchers, etc.

Not during this pandemic, though. They did everything perfectly. Mistakes were not made. /s

Disturbingly, when a perpetrator harms a victim, the perp is more likely to victim blame the more helpless the victim is. Like if a soldier kills a man in a knife duel, he just says "Es lo que es; I did what I had to do. Him or me."

But if that soldier firebombs a village of innocent rice farmers, "They put a lower price on human life over there." He'll say, "There's just so many of them, they don't mind if you burn a few. They'd do it to us if they could." Things go from bad, to disgusting, to odious.

People with low self-esteem may be less likely to make excuses. But they're also more likely to discount any information that might improve their self-esteem. Since all thoughts words and actions are self-reinforcing, and we naturally confirm our biases, people with low self-esteem will argue in favor of themself being trash, and high-self-esteemers will argue in favor of themself being treasure.

Hump had no interest in hearing anything that would counter his self-loathing. He was remarkably lucid about the power of narratives. He never argued with me about it. But the second it was time to analyze his narrative, out came the yeah-but's, and the broken record would spin.

You don't need money, or religion, or drugs to get good people to do bad things. You just need to fool them once, then let self-justification run its natural course. Like siphoning gasoline. Get a sucker over the edge, and gravity will take it from there.

Self-justification is what gets otherwise ethical police officers to falsify evidence and throw innocent people in jail (NEVER TALK TO THE POLICE. Repeat after me: "I want a lawyer"). Or worse, ignore the bullet hole in your face for six hours, because they decided you're the perp, not the second victim of a shooter who's still at-large. It gets doctors and psychotherapists to keep people on harmful ineffective treatments, till a patient dies or harms someone else, rather than undermine their original assessment. It gets two people in a relationship to turn small incompatibilities into deal-breakers. It keeps blood feuds roaring for generations, and makes retaliation escalate exponentially. It creates nonsensical prejudices and keeps them in circulation, long after their supposed use has worn off. It makes change nearly impossible, and absolutely destroys the impact of an apology.

Btw, I'm amazing at apologies. I don't even have to say "sorry," here's the script:

"You're right to be upset. I think I would be too if I were in your position. The last thing I was hoping to do was harm you. If I'd have known better, I would have gladly done something entirely different. I don't ever want to put you in this uncomfortable position again, so here's exactly what I plan to do differently from now on:"

It's wordy, but it's comprehensive. Your victim will probably want to customize and edit your apology a tiny bit to feel completely heard. Take their adjustments graciously, then thank them. A+ apology. What guilt? Big caveat: it absolutely doesn't work if you don't actually change the way you said you would, so be very careful what you promise.

One of the most important takeaways from the book is this: we live in a culture that doesn't tolerate mistakes. We don't see errors as a necessary part of learning. We see them as damning character flaws. We hide our mistakes, judge others by terrible standards, and when things aren't instantly easy, we're more likely to just give up and play the sour-grapes card. Like, "I could learn to do X, but it's just not my jam." or, "I wasn't born to do that like some other people."

In cultures where mistakes are respected, kids make better students, leaders are less arrogant and dishonest, and I gotta assume that life is a pinch less stressful. They have more of that Evel Knievel spirit, like it's not about how many times you fall, but how many times you get back up.

I made mistakes with Humpty. He was pitching, I was catching. I can say the guy throws like an inflatable tube man with cerebral palsy, but I also have to fully admit that my catching game was like Mr. Magoo trying to hunt mosquitos with a pair of chopsticks. This was a failure on my part. Period. I'm a shit therapist. I definitely figured I'd be better at this. But that's how the Dunning Kruger effect works.

(Unlike our boy Wednesday, who just graduated this week at the very top of his class. He's a bonafide therapist, not an ignorant wannabe prick like myself. Like I always say, Humpty's an anti-model, Wednesday's a role model.)

Or maybe I just hurled Humpty's ass into the air, and he landed on my stupid head.

Either way, he'd be better off ignoring all my criticism of his behavior, grabbing this book, and learning to do it himself.

• #4 The Shallows by Nicholas Carr •

Lets face it, ain't nobody reading no more books.

About 90% of all my "books" are in my Audible library. I write extensive notes but I'm also simultaneously playing something like The Long Dark or RDR2, or going on a walk while I listen. Sitting down with no distractions and flipping through a book for me is rare.

It just doesn't feel like an escape, because I'm constantly reading anyway, just like everyone else. I read as I scroll through my YouTube feed, social media notifications, comment sections and tweets, subtitles on foreign media, or flitting through aimless rabbit holes of hypertext. Powering straight through a fat wad of text from beginning to end is something my brain is just increasingly unwilling to do, no matter how much I beg or scold it.

I'm not alone.

Even famous galaxy-brains are admitting it. Long form, linear media consumption is disappearing; We're all developing attention deficit disorder wherever the internet exists. We want the Sesame Street version of absolutely everything.

Does that mean we're getting dumber? Not necessarily. Although it depends on who you ask. We're transforming into the kind of humans Socrates warned about, as people began to transition from an oral culture to a literate one.

He said it'd wipe out our capacity for memory, which is true. We can see this demonstrated in dyslexics, who have above-average memory abilities. When you have information stored in a page, you forget all the details, and simply remember where to find the page.

Practically speaking that's just fine. In fact it's far more efficient. But it has two drawbacks: if you lose the book, you lose the info. And we confuse knowledge in our hands or on a shelf with knowledge in our actual head, exacerbating our "illusion of explanatory depth" problem mentioned above.

The existence of books has expanded the whole human race's overall capacity for knowledge. But among individuals, they can make the reader a more shallow thinker, with greater pretenses to knowledge they don't actually posses. We couldn't have gotten to the moon, or invented insulin without literacy. But we also might be incapable of coming up with another Odyssey. If the computers all fry and the books all decompose, modern humans are going to vanish from history.

(Which is a major factor in me learning masonry. I want a mushroom cloud carved into stone, and I want people thousands of years from now to never forget that we harnessed the power of the fucking SUN.)

The internet has taken this to an extreme level. Books rewired human brains in an unprecedented way, and for the first time since those juicy Gutenbergers came hot off the grill, we've found a medium to displace or maybe even replace them.

We're trading intensity for extensity; breadth over depth. People give a web page twenty two seconds on average to determine if it's of use to them, before leaving. When they do stick around to read, they read only about eighteen percent before spotting the most promising blue hypertext and moving on. Everything is chopped up between notifications, refreshing news feeds, opening new tabs for later, etc.

"Learning" and, "multimedia" don't belong in the same sentence. Unless that sentence is, "Multimedia destroys a person's learning abilities."

Switching our focus like this incurs what are called "switching costs". Essentially, we lose the momentum of our focus, and it takes time to get it back.

Just as when someone loses their sight and the auditory centers of the brain annex the visual ones, the linear reading areas of our brain are being annexed by the non-linear crossword puzzle ones.

There's no resisting this, as far as I can tell. It's the direction the world is going in, thanks to the internet. It's the world I've been living in my whole life. I've been saying ADD is not a disorder since forever. It's only a disorder insofar as schools and certain institutions don't know how to cope with it. But now we're all learning to cope with it. Sweet, sweet vindication.

But maybe you want to keep those linear-focus circuits nice and sharp. Well, there's a bunch of options. The most obvious one is reading books, the old fashioned way. Less obvious is things like meditating, walking in nature, exercise, and generally making sure that you're having fun while learning.

Serotonin isn't just the best part about cocaine, it also plays a key role in learning and neuron growth. This all might explain why the only games I play if I'm listening to a book are ones rich with natural scenery, and zero dialogue.

So don't feel like a dumb-dumb. Everyone's attention is getting more shallow. Attention is not just some moral virtue, it's a sensitive balance going on in your brain's reward system, which can be altered by a number of surprising factors. The fact that humans became literate animals was weird enough already. This is just the next chapter humanity's never-ending weirdness.

Our capacity for abstract thought is going up though, in the meantime. Which is basically what IQ tests measure for. IQs are going up, attention span is going down. Like I said, "smart" is a puzzling concept.

• #5 Thinking, Fast And Slow by Daniel Kahneman •

Man, how the fuck am I supposed to sum this one up? This is a god damn jawbreaker of information.

This will now be the third time I've read it, and I would say I got three more reads to go before I'll ever claim to know how to draw this proverbial bike. There's always something new that stands out and finally sinks in.

But that's part of why it's considered a masterpiece. As thiccboi whizz-kid Nassim Taleb once tweeted:

1) Never read a book that can be adequately summarized

2) Never read a book you would not reread

3) No book that can be shortened survives

I love that quotation, because that means I can just phone these summaries in, and put all the onus on you to read them. I'm not summarizing, I'm propagandizing.

If you liked You Are Not So Smart and want more where that came from, or you read it and thought it was too basic, this is the book you're looking for. A huge chunk of David McRaney's work comes straight from this book right here. They share many sources.

Matter fact, this book prepares you to read nearly every single book in this series. After this chug, everything else feels like a sip.

First he lays out the general dynamic of "fast" vs "slow" thinking. For the sake of memorability, he personifies them as two characters in one story. Two different homunculi working simultaneously, piloting our actions.

Our fast mind ("System 1") is in charge of emotions, intuitions, instincts, sensations, things happening in the here and now. It's automatic, and often imperceptible. It follows the rule, "what you see is all there is." It doesn't problem-solve, it just reacts, and often has the first and last say in decisions we make.

Our slow mind ("System 2") is our beloved rational system. It crunches the numbers, handles logic and abstract info, manages memories, imagines the future and past, and weighs contradictory notions. It's cumbersome, energy intensive, and most importantly, LAZY.

For the longest time, economists followed the "homo economicus" model of human decision making. The idea was that humans are fundamentally rational beings, maximizing utility, and persuing wealth.

Now, Matthew Arnold puked all over that garbage in 1869, with his book Culture And Anarchy. He warned about that kind of mechanical, "Benthamistic", philistine gunk. But Arnold didn't have cognitive psychology to back him up. Just sass.

Not until the 1960s did we start to see what we now call "behavioral economics." Which is a fancy way of saying psychology caught up to all the bullshit coming out of the world of economic "science". If economists get a bad rap, it's due to the sins of its pre-psychology days, and the number of them that haven't yet caught up to 1960.

Cold, mathematical, rational decision making is the rarest kind. Your doctor, judge, professor, consultant, and every other type of expert you rely on, relies heavily on their emotions to decide things.

In fact, if I disabled your emotional responsiveness, you'd struggle to make even the simplest decisions. There are stories of people with that affliction, standing in the grocery store for an hour, staring at two different boxes of cereal, reading every last jot of writing on each box to decide which one to chose, including the numbers on the barcode, and making absolutely no progress. They just can't decide. Rationality is not what moves us to action, System 1 is.

Once the two systems are illustrated, then the book starts crunching on your brain, one chapter after another, applying this model to explain dozens of biases, illusions, and heuristics. It's not just a dorm room wall poster covered in logical fallacies to help you pwn noobs in a formal debate. It's the guide to checking oneself before wrecking oneself.

For everyone wishing K–12 schools would teach critical thinking classes, I've got terrible news: that's never going to happen. Dream of something more possible, like running an ice cream parlor on Venus, or catching a speeding bullet with a single pubic hair. But hypothetically, if that far-fetched fantasy class did ever exist, this would be one of its main text books.

Before this book came out, Kahneman was known as a guru figure to many of the greatest scientists and philosophers you know. Some, like Steven Pinker, call him the most influential psychologist alive today.

His point is not that humans are irrational. Just that they're not well described by the original rational agent model. We're unreliably intelligent, not reliably unintelligent. We can use our System 2 to refine and improve our System 1, but time is always of the essence, and we can always use more help making better decisions, and more accurate judgements. Most of our brain's shittyness is laziness and disorganized thinking.

I can't even poop on Humpty with this one. I mean Wednesday and I were always trying to explain this stuff to him. But it's all highly counterintuitive. It's stuff you really just need a bible about.

• End Bit •

Still stupid. Feeling even stupiderer this month. This put such a smoosh on my head I don't think I've spoken out loud to a friend all April.

Just tossing cheese curds into 2lb bags with a big scowl on my face, wondering how to arrange this wonky Venn diagram of information into five distinct summaries. Every one of these assholes quotes at least one other book in this entry, if not multiple, and tons of the same sources.

This was the month that really made me wonder how I managed to sign myself up for a year of this. Gotta be the wildest hair that ever found its way up my ass.

But I'm glad I did. Because as the Knowledge Illusion reminded me, it's easy to believe you can draw a bike, but can you actually draw it? It was easy to read dozens of books, but also easy to forget them and just say, "look, it's in my library." So this whole series, as well as being a petty act of spite, has been me going out of my way to shore up my explanatory depth.

Failing to have any impact on Humpty could just as easily reflect my lack of understanding of all these books. Which I can't abide. I've spent years now, proud of my library, and the first time I tried to pass on these ideas to someone else, absolutely nothing was gained.

I've already called Humpty a narcissist, a fake autist, a malingering Munchausen patient, and an empty shell. This month, lets just consider the fact that I'm an idiot. I'd feel worse about the way I speak about him if I thought I was a credible source.

But I don't have to be credible. I have 60 books to recommend, they have credibility. The ones I believe changed my life, and overhauled the way I look at the world. The idea that I had something good to share with Humpty brought real light into my life, and I hate him for not taking any of it seriously.

If my series convinces just one person to read just one of these books, the whole year of work was a success.

I was running around, with my head in the sand.

Looking for a pupil, in a new fan.

She told me before, baby do your own dance.

Stay off the highway. -- K-os, Born To Run

Next month! More books! Monkey brains?!

#the knowledge illusion#the forgetting machine#mistakes were made but not by me#the shallows#thinking fast and slow#steven sloman#philip fernbach#rodrigo quian quiroga#carol tavris#elliot aronson#nicholas carr#daniel kahneman#psychology#philosophy#self help#incels#stupidity#intelligence#bias#delusion#economics#forgetting#attention deficit disorder#book club#mental health#neuroscience#behavioral economics#Humpty Dumpty Elegy#GARBLEGOX

1 note

·

View note

Link

“As a rule, strong feelings about issues do not emerge from deep understanding,” Sloman and Fernbach write. And here our dependence on other minds reinforces the problem. If your position on, say, the Affordable Care Act is baseless and I rely on it, then my opinion is also baseless. When I talk to Tom and he decides he agrees with me, his opinion is also baseless, but now that the three of us concur we feel that much more smug about our views. If we all now dismiss as unconvincing any information that contradicts our opinion, you get, well, the Trump Administration.

“This is how a community of knowledge can become dangerous,” Sloman and Fernbach observe. The two have performed their own version of the toilet experiment, substituting public policy for household gadgets. In a study conducted in 2012, they asked people for their stance on questions like: Should there be a single-payer health-care system? Or merit-based pay for teachers? Participants were asked to rate their positions depending on how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the proposals. Next, they were instructed to explain, in as much detail as they could, the impacts of implementing each one. Most people at this point ran into trouble. Asked once again to rate their views, they ratcheted down the intensity, so that they either agreed or disagreed less vehemently.

Sloman and Fernbach see in this result a little candle for a dark world. If we—or our friends or the pundits on CNN—spent less time pontificating and more trying to work through the implications of policy proposals, we’d realize how clueless we are and moderate our views. This, they write, “may be the only form of thinking that will shatter the illusion of explanatory depth and change people’s attitudes.”

#riverhead#riverhead books#steven sloman#philip fernbach#the knowledge illusion#knowledge#learning#fake news#alternative facts#news

49 notes

·

View notes

Quote

la mente umana è, allo stesso tempo, geniale e patetica, brillante e stolta

L’illusione della conoscenza - Steven Sloman, Philip Fernbach

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Must-See TV (Episode 2)

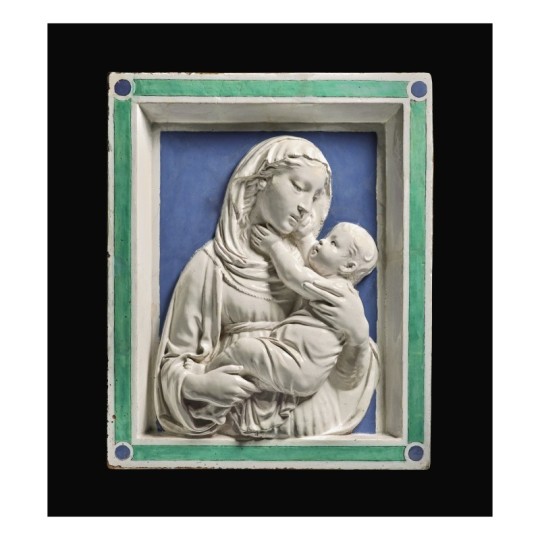

And now, for the art history.

Luca della Robbia (Italian, 1399-1482), Madonna and Child, ca. 1450, tin-glazed terracotta (18½ x 15¾ in.). Photo credit: Sothebys.com.

There were a number of items in Sotheby’s January 28 sale that caught my attention because of their association with Hyde pieces. The first was Lot 2, Luca della Robbi’s terracotta relief, Madonna and Child. Luca (1399-1482) founded a multi-generational family workshop that was famous for its terracotta sculptures covered in a gleaming, pure, white glaze—its formula, a closely-guarded family secret—that made the fired clay pieces impermeable to the elements and gave them the appearance of much more expensive marble. The reliefs were cast in molds, allowing for a degree of mass-production that expanded the clientele for such fine works of art to include the successful merchant and banking class of Renaissance Italy’s major cities.

Luca della Robbia (Italian, 1399-1482), Madonna of the Lilies, ca. 1450-1460, tin-glazed terracotta (20 1/4 × 16 1/8 in.) The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.99. Photography by Michael Fredericks.

Like The Hyde’s Madonna of the Lilies, the Sotheby’s relief was intended for the domestic market. It was undoubtedly used in the home as the focus of private, family devotion to the Virgin and Christ Child, and indeed, Sotheby’s expert Giancarlo Gentilini proposes that the relief was commissioned by Bosio I, Count of Santa Fiora in Tuscany for this wife Cecilia, sometime between 1439 and 1451.

It is striking how intimate the viewer’s relationship with the Madonna and Christ Child is, more so than in our terracotta. So high is the relief carving, the divine pair actually breaks out of their tightly constrained space into our world. The sculpture affirms the Christian belief that God was incarnate in Christ, here the robust child, tenderly held in his mother’s arms. His divinity and her purity are expressed through the terracotta’s unblemished white glaze.

Surprisingly, the two reliefs “met” once. They were both included in an exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1938 that was curated by William Valentiner, the museum’s director and Mrs. Hyde’s art advisor. Both sculptures have been praised by experts as being “autograph;” that is, they are so fine in their execution, even though other examples survive, that the hand of the master, Luca, has been discerned over that of his workshop assistants.

Lot 14, Sano di Pietro, Nativity.

Sano di Pietro (Italian, 1405-1481), Nativity, tempera and gold ground on panel (20 5/8 by 15 7/8 in.). Photo credit: Sothebys.com.

There is a clear resemblance between the form of Virgin Mary’s head in this depiction of the Nativity and that of the Archangel Gabriel’s in The Hyde’s panel that formed one half of an Annunciation scene.

Sano di Pietro (Italian, 1405 - 1481), Angel of the Annunciation, ca. 1450, tempera and gilding on panel (14 1/2 × 13 1/2 in.); The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.44. Photo credit: Mclaughlinphoto.com.

Sano di Pietro (1405-1481) was a leading painter in Siena in the first part of the fifteenth century. In the Sotheyb’s panel, we have the chance to examine his use of color and composition in constructing narrative scenes. The primary storyline, Christ’s birth in a stable, dominates the foreground. The secondary narrative, the annunciation to the shepherds, occurs in the middle distance. The principal figures, including the ox and ass, are modeled with evenly modulated light. They have a sense of early Renaissance volume and weight lacking in the rather flimsy Gothic architecture of the stable. A brightly colored choir of angels watches over the Christ Child, and God sends down the dove of the Holy Spirit in a shaft of divine light to illuminate the newborn, who lies in an aureole of straw and light that signals His divinity.

There is some debate as to whether this panel was part of a small chapel altarpiece or intended for use in a domestic setting. Last year, a student from Florence wrote to The Hyde asking for particular information about our panel. She thought she might know the altarpiece from which our Angel came. The piecing together of dismembered altarpieces, often by studying physical elements such as the thickness of the panel and the pattern of growth rings, is an emerging field of research. It educates art historians in the more practical and physical aspects of art production. I have tried to follow up, but, as of yet, still await news of her findings.

Lot 15. Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel.

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1444-1510), Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel, n.d., tempera on panel (23 x 15 ½ in.). Photo credit: Sothebys.com

This is the auction item that everyone is talking about. It sold for $80M (with commissions, etc., it came to $92,184,000).

There was little drama in the sale itself. The opening bid was $70M. The sale ended five bids later, in increments of $2M, at $80M. With commissions and fees, the work topped out at over $92M, the most ever spent for a Florentine Renaissance Master.

As in the della Robbia discussed above, the artist uses the architectural framing within the piece to push the figure forward. Through the illusion of a finger extending beyond the painted lower ledge, Botticelli suggests that the young man is real and actually standing in the viewer’s space. Elegance is the watchword for this painting. It is present in Botticelli’s use of line and form and in the artist’s self-assurance and that bestowed upon the figure and character of the sitter. These are qualities that we can sense in The Hyde’s small predella panel depicting the Annunciation.

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1444-1510), Annunciation, ca. 1492, tempera on panel (7 x 10 9/16 in.). The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.10. Photography by Joseph Levy.

Mary reacts in a graceful and demure manner as Gabriel glides in to the loggia where she was reading her devotional book. The angel’s robes flutter, perhaps a little fussily. Where our sadly abraded panel gives only a hint of Botticelli’s command of delicate shades and tones, the remarkably well-preserved Sotheby’s portrait gives ample evidence of Botticelli’s mastery of tempera painting.

The roundel the young man holds is a very peculiar detail. It is a separate work of art by the Sienese artist Bartolomeo Bulgarini from roughly a century earlier, and it has been pieced into Botticelli’s panel. Quite what Botticelli meant to signify by this is debated by scholars. Was he suggesting a genealogical link between the two, a shared character trait, or perhaps a strong devotion by the young man to the unidentified saint?

School of Haarlem (Dutch, 1600-1699), Portrait of a young man holding his gloves and wearing a tall hat, his arm akimbo, oil on panel, an oval, (10 by 7 ½ in.). Photo credit: Sothebys.com.

I was curious about the next lot, rather cautiously identified by Sotheby’s as “School of Haarlem, Portrait of a Young Man Holding his Gloves, circa 1615.” I thought immediately of the small oval portrait in Hyde House dining room that we now attribute to the Circle of Frans Hals.

Circle of Frans Hals, (Dutch, 1580-1666), Portrait of the Artist's Son, ca. 1630, oil on panel(7 7/16 × 6 1/2 in.). The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.21. Photography by Michael Fredericks.

Like ours, the Sotheby’s painting was once thought to be by Frans Hals himself. Hals (1580-1666) is famous for portraits that both in the manner of their execution and in the personality of their sitters, are full of dash and swagger. In the catalogue entry, Sotheby’s favored an attribution to a contemporary of Hals, Willem Buytewech (1591-1624). The market didn’t agree. Bidding started at $30,000 for this small oval work that measures 10 x 7½ inches. It finally came to a stop after helter-skelter bidding at $390,600 (with fees)! There were plenty of bidders, who evidently thought this to be by Frans Hals. Would someone care to reconsider our painting? Like the Sotheby’s piece, the Hyde portrait was authenticated as a Hals by William Valentiner, but subsequently downgraded by several scholars, among them Seymour Slive, who reattributed the Sotheby’s work to Buytewech.

Hubert Robert (French, 1733-1808), View of a Garden with a Large Fountain and View of a Walled Garden Courtyard, n.d., oil on canvas (99¼ x 56¼ in.). Photo credit: Sotheby’s.com

It was a detail in Lot 39, the eponymous fountain in Hubert Robert’s View of a Garden with a Large Fountain, that caught my attention. It recalled to mind the vertical jet fountain in The Hyde’s drawing, Château in the Bois de Boulogne, ca. 1780.

Hubert Robert (French, 1733-1808), Château in the Bois de Boulogne, ca. 1780, graphite on paper (9 3/16 x 15 3/4 in.). The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.103. Photography by Steven Sloman.

Such powerful vertical jets of water first became popular in French garden design at Versailles, where they symbolized the power of the Sun King. By the eighteenth-century, pleasure rather than power was the primary objective of art, architecture, and garden design. Robert was popular among the French aristocratic elite for painting large-scale decorative schemes for their grand houses. He often depicted pleasure gardens, bucolic scenes, and romantic ruins. In 1778, the painter was appointed designer of the king’s gardens. In the Sotheby’s piece the vertical jet of water makes a suitable compositional focal point in a panel that measure 8’ 3” in height.

A similar jet fountain appears in a decorative room panel signed and dated by Robert in 1773, executed for the financier Jean-François Bergeret de Frouville. Exhibited at the Salon of 1775, it was entitled The Portico of a Country Mansion, near Florence, and is now in the possession of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hubert Robert (French, 1733-1808), The Portico of a Country Mansion, near Florence, 1773, oil on canvas (80 3/4 x 48 1/4 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Lucy Work Hewitt, 1934, 35.40.2. Photo credit: Metmuseum.org.

In our drawing, Robert drew a actual fountain, one that dominated the parterre behind the Château de Bagatelle in the Bois de Boulogne, on the outskirts of Paris. The château was built by the Comte d’Artois, the brother of Louis XVI. Marie Antoinette had bet him that he could not build his little pleasure palace within three months. Designed by the architect Francois-Joseph Belanger (1744-1818) in the Neoclassical Style, the party house was constructed in just 63 days. Robert decorated its salle de bains with six panels that depicted the Italian countryside, classical buildings, and various forms of entertainment, like dancing, swinging, and bathing. These panels, too, now reside at the Met.

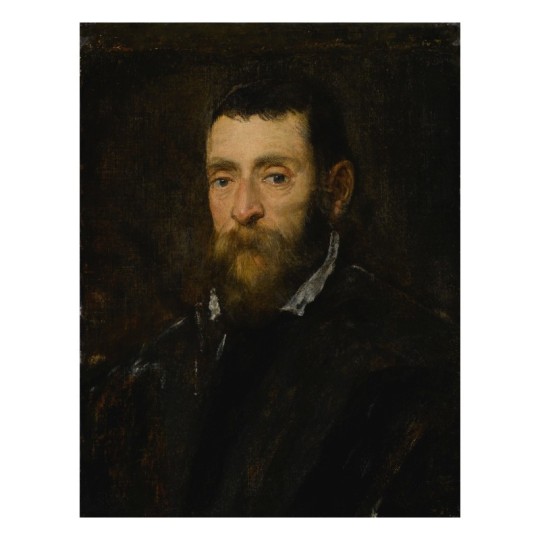

Jacopo Robusti, called Jacopo Tintoretto (Italian, 1518-1594), Portrait of a Bearded Man, 1560s, oil on canvas (23 3/8 x 18 in.). Photo credit: Sothebys.com.

Jacopo Robusti, called Jacopo Tintoretto (Italian, 1518-1594), Portrait of the Doge Alvise Mocenigo, ca. 1570, oil on canvas (21 1/2 x 15 1/2″); The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde,, 1971.49.

I have taken this last work out of turn, but I thought I would end with a comparison of hipster beards. Lot. 23 was Jacopo Tintoretto’s, Portrait of a Bearded Man. It was probably painted within a decade of The Hyde’s Portrait of the Doge Alvise Mocentigo (ca. 1570). The two share many traits. They are both portraits of self-possessed, wealthy men. Their dark somber clothing signals that. They dress according to the dictates of the style-setter for courtiers, Baldasare Castiglione (1478-1529), who wrote that “ the most agreeable color is black, and if not black, then at least something fairly dark.” Presented at only bust length, their torsos turned slightly away from the viewer but engaging directly with their eyes, these portraits convey a sense of intimacy and dialogue. The sitter’s face emerges from a dark background, its features modeled in warm lighting.

There are no known preparatory drawings by Tintoretto for portraits. He seems to have worked directly on the canvas before him. This would have appealed to his primarily male sitters because it undoubtedly reduced the number and length of sittings. As a side note, while it was acceptable for a man to sit or his portrait in a painter’s studio, it was not for a woman. Inconveniently for the portraitist and patron, the painter had to set up his easel and paint with oils in a female sitter’s house. Thus, the cost of a woman’s portrait was often more expensive. The conservative taste of the Venetian elite ensured that the compositional characteristics of this portrait had not changed in a generation. Where Tintoretto excelled was in the mastery and boldness of his brushstrokes and the accompanying speediness of execution. Notice, particularly in the Sotheby’s painting, the freedom and liveliness of the white brushstrokes with which he defines the shirt collar, distinguishes between the sitter’s beard and dark clothing, and spatially locates the different elements of the body within the otherwise ill-distinguished depth of the painting. Patrons valued Tintoretto’s masterly touches with the brush, the contrasts between areas of thickly applied paint and those where it is so thinly applied that one can discern the weave of the canvas. Working with accepted conventions, Tintoretto was able to convey something of what made his bearded male sitter unique.

There is always something of the wishful shopper, when I flip through a sales catalogue. But I am always excited when I discover something that relates to a work in our collection, and I ultimately never cease to marvel at the judicious purchases made by Louis and Charlotte Hyde.

#hydecollection#sotheby's#frans hals#sano di pietro#luca della robbia#botticelli#hubert robert#Tintoretto

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘‘The nature of thought is to seamlessly draw on knowledge wherever it can be found, inside and outside of our own heads. We live under the knowledge illusion because we fail to draw an accurate line between what is inside and outside our heads. And we fail because there is no sharp line. So we frequently don’t know what we don’t know.’’

- Steven Sloman, Philip Fernbach

0 notes

Quote

It's futile to try to teach everything to everyone. Instead, we should play to individuals' strengths, allowing people to blossom in the roles that they're best at playing. We should also value skills that enable people to work well with others, skills like empathy and the ability to listen. This also means teaching critical thinking skills, not focusing just on facts, to facilitate communication and an interchange of ideas. This is the value of a liberal education, as opposed to learning what you need to get a job.

The Knowledge Illusion by Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Questions are often more powerful than assertions. But which questions? We need to learn to ask the right kinds of questions, the ones that lead to productive conversations. In one experiment, Steven Sloman, professor of psychology at Brown University, and his colleagues found that, broadly speaking, asking people why they hold their beliefs leads to less humility and openness to conflicting views than asking them how their proposal works. The question of how cap and trade policies reduce global warning, for example, asks subjects to spell out a causal mechanism step-by-step. Subjects found it difficult to specify this mechanism, so they came to realise that they did not understand their own position well enough, and they became more moderate and open to alternative views. We can also ask ourselves similar questions. Questioning how our own plans are supposed to work will likely make us more humble and open-minded, because then we come to realise that we do not understand as much as we thought or as much as we need to.

Moreover, if we regularly ask others and ourselves such questions, then we will probably come to anticipate such questions in advance. Jennifer Lerner and Phillip Tetlock, psychologists at Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania, respectively, have shown that accountability - expecting to need to give reasons for claims - leads people to base their positions more on relevant facts than on personal likes and dislikes. A context that creates such expectations - including a culture that encourages asking such questions about reasons - could then help to foster humility, understanding, reasoning and arguments that give answers to questions about reasons.

The goal of questioning and humility is not to make one lose confidence in cases where confidence is justified. Proper humility does not require one to lose all self-confidence, to give up all beliefs, or to grovel or debase oneself. One can still hold one’s beliefs strongly while recognising that there are reasons to believe otherwise, that one might be wrong, and that one does not have the whole truth. Giving and expecting reasons along with asking and answering questions can help move us in this direction.

Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, Think Again: How to Reason and Argue

21 notes

·

View notes

Link

Due to #Technology anyone in the world can be a source of #News. Second, again because of #Technology, we are inundated by #Information. Finally, people have the freedom to tune into news sources that tell them what they want to hear. Steven Sloman on the #Psychology of #Fake #News. Interview by Tania Lombrozo. #NPR

#Technology#News#Information#Steven Sloman#Psychology#Fake News#Psychology of Fake News#Tania Lombrozo#NPR

0 notes

Text

MBTI & Ideas

Causal Models (Steven Sloman, 2005)

“One school of thought among philosophers is that probabilities are essentially representations of belief, that probabilities reflect nothing more than people’s degree of certainty in a statement. (...)

For this reason, philosophers who believe that probabilities are representations of belief are sometimes called subjectivists because they claim that probabilities are grounded in subjective states of belief.”

——

“If a subjectivist wants the probability that a particular horse will win the race to be high, then what is stopping him or her from simply believing and asserting that the probability is high?

The answer is that even a subjectivist’s probability judgments have to make sense.

They have to cohere with all their other judgments of probability, and they have to correspond with what is known about events in the world.

This is how Bayes’ rule helps; it prescribes how to take facts in the world into account in order to revise beliefs in light of new evidence.

That is, it dictates how to change your probability judgments in the face of new information— how to update your beliefs or, in other words, to learn—while maintaining a coherent set of beliefs, beliefs that obey the laws of probability.”

——

“We start with a degree-of-belief in the way the world is; we look at the world; if the world is consistent with our beliefs, then we increase our degree-of-belief. If it’s inconsistent, we decrease it.

In fact, if we do this long enough, if we have enough opportunity to let the world push our probabilities around, then we would all end up with the same probabilities by updating our beliefs this way.

Bayes’ rule is guaranteed to lead to the same beliefs in the long run, no matter what prior beliefs you start with.”

7 notes

·

View notes