#Rabotnitsa

Text

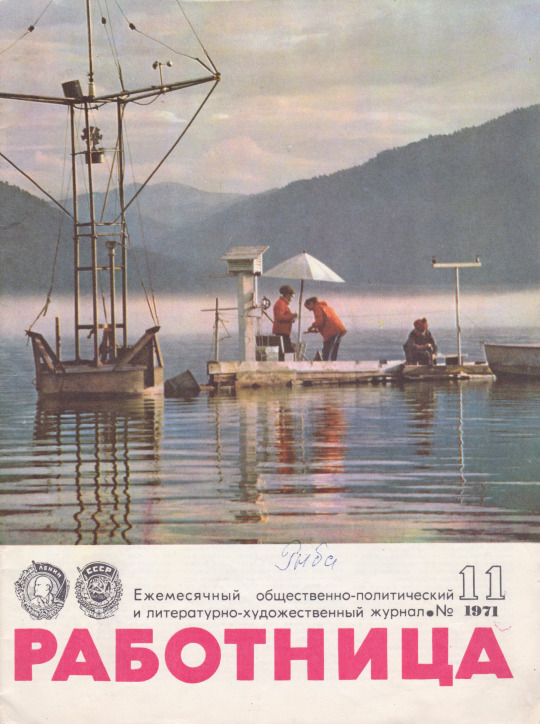

Cover of Rabotnitsa [Working Woman], November 1971

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“What makes a person happy?” Taken from the Janurary 1984 issue of Работница (Woman Worker)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Что покупали молодые родители в эпоху СССР?

What did young parents buy in the Soviet era? 👶🏻

🇷🇺Сейчас на Российском рынке можно найти любые виды товаров для детей, а также технику, которая помогает молодым родителям ухаживать за ребёнком.

Но это сейчас. А ещё 30 лет назад всё было соверше́нно по-другому.

Я хочу рассказать вам о том, что покупали для своих детей и чем пользовались молодые родители времен СССР.

🇬🇧Now on the Russian market you can find all kinds of goods for children, as well as equipment that can help young parents to take care of their child.

But this is now. 30 years ago everything was completely different.

I want to tell you about what the young parents of the Soviet era bought and used for their babies.

🍼Подгу́зники | Diapers

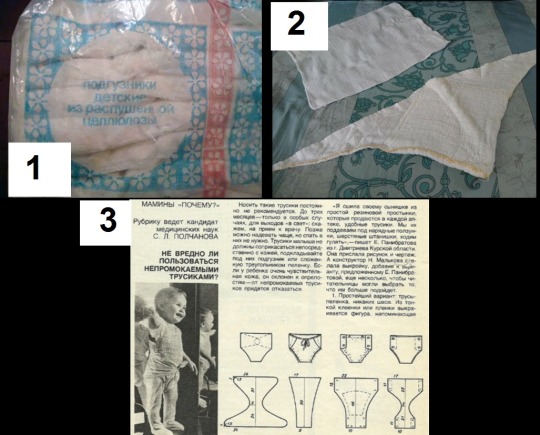

🇷🇺Первые однора́зовые подгу́зники появились в 60 годах в США. В СССР однора́зовые подгу́зники Pampers Huggies и Libero пришли лишь в начале 90х, но не все советские граждане могли их себе позво́лить. До прихода Pampers в СССР в 1980 -е и 1990-е выпуска́ли бумажные однора́зовые подгу́зники. (Фото 1)

🇬🇧The first disposable diapers appeared in the 60s in the USA. In the USSR, disposable diapers (Pampers Huggies and Libero) came only in the early 90s, but not all Soviet citizens could afford them. In 1980s - 90s (before Pampers came to us) the USSR factories were producing the disposable diapers. (Photo 1)

🇷🇺Они встречались редко, поэтому женщины предпочита́ли сами шить подгу́зники из марли или старого посте́льного белья́.

(Фото 2)

🇬🇧They were rare, so women preferred to sew diapers from a gauze or old bed linen. (Photo 1)

🇷🇺Женские журналы "Рабо́тница" и "Крестья́нка" помогали молодым родителям и печатали вы́кройки непромока́емых тру́сиков, которые можно было сшить из какого-нибудь материа́ла. (Фото 3)

🇬🇧The women's magazines "Rabotnitsa" and "Krestyanka" helped young parents and printed patterns of waterproof panties that could be sewn from any material.

(Photo 3)

🍼 Коля́ски - a baby strollers

🇷🇺Коля́ски в СССР стали появля́ться в 50-е годы и счита́лись большой ро́скошью (Фото 1). Как обходи́лись без них? Носили детей на руках. Зимой – ката́ли детей на са́нках. В 70-е годы коля́ски появи́лись у каждой молодой семьи. (Фото 2). Сове́тские коля́ски были очень тяжелыми и неудобными. Повезло тем, кто смог достать и́мпортную коляску, которые счита́лась большой ре́дкостью.

🇬🇧Strollers in the USSR began to appear in the 50s and were considered a great luxury (Photo 1). How did people manage without them? They carried children in their arms. In winter parents put children on sleds. In the 70s, strollers appeared in every young family (Photo 2). Soviet strollers were very heavy and uncomfortable. Lucky for those, who were able to get an import stroller, which was considered a rarity.

🇷🇺В СССР пыта́лись выпуска́ть де́тскую коля́ску- трансфо́рмер из пластма́ссы. (Фото 3) Такая коляска была опа́сной, так как она могла переверну́ться вместе с ребёнком, а ещё она часто лома́лась.

🇬🇧In the USSR, they tried to produce a plastic transformer stroller (Photo 3). This stroller was dangerous, as it could roll over with the child, and it also often broke.

🇷🇺В 80-х годах очень хорошие де́тские коля́ски начал выпуска́ть завод Лиепая. Завод выпуска́л разные виды коля́сок: для двойня́шек и даже тройня́шек, а также коляски для кукол.

🇬🇧In the 1980s, the Liepaja factory began to produce very good baby carriages. The factory produced different types of strollers: for twins and even triplets, as well as strollers for dolls.

🍼Санки | Sleds

🇷🇺Са́нки были отли́чной альтернати́вой коля́скам в зимний пери́од времени. Они были очень популярны в СССР. Ката́ние на са́нках было любимым зимним развлече́нием сове́тских дете́й.

🇬🇧Sleds were a great alternative to strollers in winter. They were very popular in the USSR. Sledding was a favorite winter pastime for Soviet children.

🍼Стира́льная доска и сове́тская стира́льная маши́нка | Washing board and Soviet washing machine

🇷🇺Когда в доме появля́ются дети, появля́ется и много гря́зного белья́,не правда ли?

Здесь на по́мощь сове́тским роди́телям приходили стира́льные до́ски и стира́льные маши́нки.

🇬🇧When children appear in the house, a lot of dirty laundry appears, doesn't it?

Here, washing boards and washing machines came to the aid of Soviet parents.

🇷🇺В Сове́тском Сою́зе было много ма́рок и модифика́ций стира́льных маши́н. Они создава́лись по зарубе́жным техноло́гиям.

Первые стира́льные маши́ны в СССР появи́лись в 1950 году. (Фото 1)

🇬🇧There were many brands and modifications of washing machines in the Soviet Union. They were created using foreign technologies.

The first washing machines in the USSR appeared in 1950. (Photo 1)

🇷🇺В 60-е годы появи́лись маши́нки-полуавтома́ты. Не́которые экземпля́ры этой стира́льной маши́ны дожи́ли и до наших дней. Сохрани́лись они в основно́м в домах пенсионе́ров. (Фото 2)

🇬🇧In the 60s, semi-automatic machines appeared. Some instances of this washing machine survived to the present day. They survived mainly in the homes of pensioners. (Photo 2)

🇷🇺Первая автомати́ческая стира́льная маши́на появи́лась в СССР в конце 70-х. (Фото 3)

The first automatic washing machine appeared in the USSR at the end of the 70s.

(Photo 3)

🇷🇺Ну а потом на рынок пришли за́падные производи́тели. Несмотря на разнообра́зие стира́льных машин, сове́тские люди всё ещё испо́льзовали стира́льные до́ски.

🇬🇧And then Western manufacturers came to the market. Despite the variety of washing machines, the Soviet people still used washing boards.

🍼Де́тские крова́тки | Baby cots

🇷🇺 В советское время выпускались простые, но очень удобные детские кроватки. Но многие предпочитали изгот��вливать кроватки самостоятельно.

🇬🇧 In Soviet times, simple but very comfortable baby cots were produced. But many people prefer to make baby cots by themselves.

🍼Детское пита́ние | Baby food.

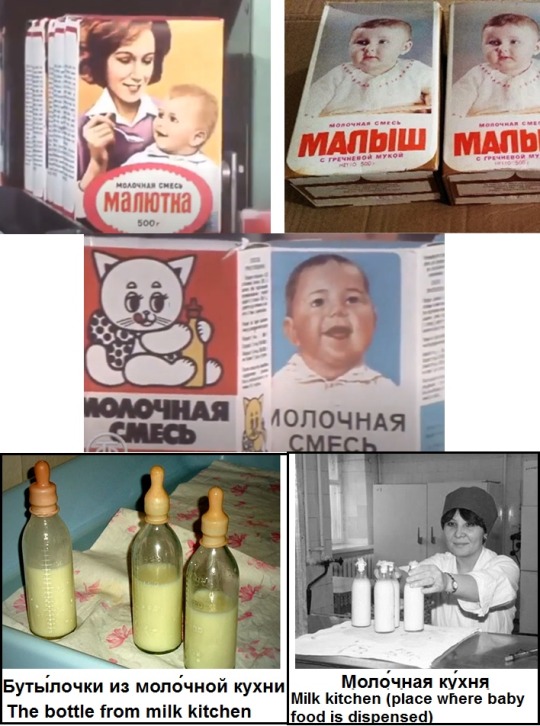

В 1950-е годы в СССР началось произво́дство де́тского пита́ния: консерви́рованных соков и пюре́, сухи́х молочных сме́сей (смесь), каш (каша)и киселе́й (кисе́ль).

🇬🇧In the 1950s, the production of baby food began in the USSR: canned juices and purees, dry milk mixtures, porridge and jelly.

🇷🇺«Малы́ш» и «Малю́тка" – одни из самых первых детских сухих молочных продуктов, которые появились в сове́тских магазинах.

🇬🇧"Malysh" and "Malyutka" are some of the very first dry milk products for children that appeared in Soviet stores.

🇷🇺В СССР были популярны моло́чные ку́хни. Там бесплатно выдава́ли родителям буты́лочки с молоком и другие молочные проду́кты для детей.

🇬🇧Milk kitchens were popular in the USSR. There, parents could get bottles of milk and other dairy products for their children for free.

🇷🇺В 70-е годы были постро́ены заводы, которые выпуска́ли жи́дкие сме́си для детей. Сначала сме́си продавали в стекля́нных ба́ночках, а потом стали продавать в карто́нных паке́тах.

🇬🇧In the 70s, factories that produced baby formula were built. At first, baby formula was sold in glass jars, and then it began to be sold in cardboard bags.

🇷🇺В 1990-е годы в сове́тских магазинах появи́лись мировы́е детские продукты - молочные сме́си, йогурт, хло́пья. Но досту́пны они были далеко не всем.

🇬🇧In the 1990s, world children's products appeared in Soviet stores - milk mixtures, yogurt, and cereals. But they were not available to everyone.

🍼Со́ски | Baby's pacifier

🇷🇺Детские молочные со́ски были нужны для кормле́ния - их надевали на буты́лочки с детской сме́сью. Производи́ли такие со́ски из пищево́й рези́ны. У них могла быть вы́тянутая или кру́глая форма.

🇬🇧Baby's pacifiers were needed for feeding - they were put on bottles with baby formula. They were made from food rubber. They could have an elongated or round shape.

Со́ска – пусты́шка (Фото 3) - baby's dummy (Photo 3)

Соски для молока и каши. (Фото 1, 2) - baby's pacifier for milk and porridge (Photo 1,2)

Ещё немного детских товаров времен СССР:

A few more children's goods from USSR:

🍼 1 - Электронагрева́тель для детского пита́ния «Малыш» | Electric heater for baby food "Malysh"

🍼 2- Клеёнка | Incontinence sheet (undersheet)

🇷🇺Это детская водонепроница́емая пелёнка, которую родители стели́ли ребёнку в крова́тку или коля́ску.

🇬🇧This is a waterproof baby napkin, which the parents put the baby in a crib or stroller.

🍼 3 - Погрему́шки | Rattles

🍼Слюня́вчик или детский нагру́дник | Bib

🇷🇺Это небольшой кусок ткани, который прикрыва́л грудь и живо́тик малыша́, защища́я одежду от попада́ния на неё детской слюны́ и пищи.

🇬🇧This is a small piece of fabric that covered the baby's chest and belly, protecting the clothes from baby saliva and food getting on it.

#ussr (former soviet union)#русский язык#learning russian#советскийсоюз#soviet union#история ссср#Россия#история России#russian language

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Inessa Armand was born Inessa Steffen in Paris on 26 April 1874, the illegitimate child of Theodore Steffen, a British opera singer, and Nathalie Vil’d, a French actress. She grew up speaking French and English and later learned Russian, German and Polish. After her father died in 1889, she moved to Russia to stay with relatives. In 1893, she married Alexander Evgen’evich Armand (died 1943), whose family were wealthy manufacturers of French origin. By 1903, Inessa Armand had given birth to four children (Alexander, Varvara, Inna and Vladimir). In 1902, she left her husband; in 1903, she married his younger brother Vladimir, who shared her radical political views and bore him her last child, Andrei.

In the summer of 1903, Vladimir and Inessa Armand went to Moscow to become professional revolutionaries. Under the influence of Marxism, Inessa regarded the women’s movement as merely the ‘female equivalent’ of the male workers’ struggle for liberation. She believed the ‘class criterion’ most always be taken into account when defining a revolutionary attitude to the struggle for women’s rights, since participants in that struggle from different social strata would have different social concerns. Under the threat of arrest, the Armand family emigrated for Paris. After her husband’s death from tuberculosis, Inessa Armand remained politically active, in spite of the everyday hardships she faced bringing up five children alone.

In 1904, Armand joined the Parti Socialiste Français (French Socialist Party). In the same year, she returned to Russia (Moscow) and became a member of the Rossiiskaia SocialDemokraticheskaia Rabochaia Partiia (Russian Social Democratic Labor Party). It was also in 1904 that the Moskovskoe Obshchestvo Uluchsheniia Uchasti Zhenshchin (Moscow Society for the Improvement of the Situation of Women), established in 1899, elected Armand Chair of its Commission on Education. With the outbreak of the 1905–1907 Russian Revolution, Armand began organizing Sunday schools for craftswomen, female workers, maids and housewives. The aim was to turn these units into centers for revolutionary propaganda, where women might be encouraged to discard their traditional views on the family.

On 7 February 1905, Armand was arrested in St Petersburg but released three months later. She immediately resumed revolutionary agitation among women workers and also made efforts to establish contacts between Russian and foreign socialist feminists, as part of efforts to unify the international women’s labor movement. The failed Revolution of 1905–1907 was followed by a wave of political reaction and Armand’s activities were noted by the authorities. In the fall of 1907, Armand managed to emigrate, again to France where she joined the most vigorous activists of the Presidium of the emigrant Bolshevik organization: “The Group for Assistance to the Party.”

In 1908, she traveled illegally to St Petersburg in order to participate in the First All-Russian Women’s Congress but did not play any active role in organizing the Congress or its sessions. (Her own views did not correspond with those of the liberal wing of the Russian women’s movement, which had initiated the Congress.) At the end of December 1909, in Paris, Armand met the leader of the Russian Social Democratic Party, Vladimir Ul’ianov (Lenin) (1870–1924). The beginning of their friendship dates from the spring of 1911, when the socialists succeeded in opening a party school in Longumeaux (near Paris) where Armand worked as a lecturer. Lenin found himself among one of the many unable to resist the beauty and charm of this remarkable feminist.

In the spring of 1912, socialist emigrants sent Armand to Russia to organize underground party activities. By this point Armand, along with other Russian and foreign colleagues, had become actively involved in setting up a foreign version (i.e. to be published abroad) of the new women’s magazine Rabotnitsa (Female worker)—initially intended for a Russian proletarian female readership. The first issue of this magazine came out on 8 March 1914 (International Women’s Day). Armand grew increasingly fascinated by socialist feminism. In January 1915, she composed a brief draft of an article on feminism and sent a draft version of a pamphlet on women’s rights to Lenin.

He sharply criticized Armand’s program for women’s liberation and recommended that she remove her demand for free love, since it seemed a bourgeois demand to him—an appeal to “freedom of adultery” and a threat to the emergent new communist society (Stites 1978, 260–261). It was always necessary, declared Lenin, “to take into account the objective logic of class relations in matters of love” (Margar’an 1962, 213–215). Armand chose not to agree. Armand represented Russian Social Democrats at several key international events: the International Socialist Women’s conference (1915), the International Conference of Youth (1916) and the Zimmerwald (1915) and Kintal (1916) conferences of the social democratic internationalists. From 1916, she lived in Paris.

Sharing some of Lenin’s ideas—in particular the importance he placed on the role of women workers in preparing for socialist revolution—she translated many of his works into French. After the fall of the Russian Monarchy in February 1917, Armand returned to Russia via Germany. In April 1917, she was an elected delegate to the Sed’maia Vserossi-iskaia Konferenciia Rossiiskoi Social-Demokraticheskoi Rabochei Partii (Seventh AllRussian Conference of the RSDRP, Russian Social Democratic Party of Workers). After that she moved to Moscow to be with her children (her youngest son Andrej had become sick and there was a chance that he had tuberculosis). In Moscow, Armand set up courses for the education of agitators and propagandists; she wrote speeches for workers and participated in the work of the Moskovskogo Soveta Rabochih Deputatov (Moscow Deputies’ Council).

In the summer of 1917, she took her children to the south of Russia, returning to Moscow in the midst of the Revolution. After Soviet rule had been established, she took part in new Party activities. She had an incredible capacity for hard work, often working up to fourteen hours a day. She found herself among the most prominent party leaders and was an elected member of the Moskovskii Gubernskii Komitet Partii (Party Committee for the Province of Moscow); later, she became Chair of the Moskovskii Gubernskii Economicheskii Komitet (Moscow Economic Council). ‘The woman question’ continued to be regarded as an important aspect of social change. Even Vladimir Lenin, Armand’s idol, finally agreed (not without her influence) that now was the time to recognize that women had their special demands and needs, and that it was necessary to devise new working methods to improve women’s situation.

In the spring of 1918, Armand began organizing the “School of Soviet Work,” which was to have, for the first time, a special Zhenotdel (Women’s Bureau). It was at this time that Armand’s interest in the history and theory of ‘the woman question’ intensified and she became editor of a new magazine, Zhizn’ Rabotnitsy (The life of a woman worker). From 1918 to 1919, Armand was the head of the Zhenotdel at the Central Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Bolshevik Party, which held executive power. Back then she also worked—under the pseudonym Yelena Blonina—for another magazine, Kommunistka (Woman-communist). In 1919, Armand began working for the Second Communist International Congress, where she defended ideas of social equality between men and women.

She was concerned about the ways in which everyday life and family relations in Russia were to be practically restructured; in her view, the new Russia lacked the necessary resources to liberate women. In a society struggling for survival, the creation of facilities that could have freed women from daily chores (something often cited by male discussants of ‘the woman question’) seemed an impossible dream. One had to search for other ways of liberating women. Armand saw all the hardships her contemporaries endured and treated them as her own, prompting her to organize and lead the Pervaia Mezhdunarodnaia Konferenciia Zhenshchin-Kommunistok (First International Conference of Women Communists).

Years of overwork (including care for her children), fatigue and hunger all took their toll on Armand’s energy and strength. In the fall of 1920, she contracted cholera and died on 24 September 1920. The urn containing her ashes was buried in in the Kremlin wall. Soviet historiography has mostly paid attention to her Party activities and her work during the first years of the Soviet regime. The work of western historians has often dwelled on the relationship between Lenin and Armand. No publications have yet addressed her impact on the Russian feminist movement.”

- Natalie Pushkareva, “ARMAND, Inessa-Elizaveta Fiodorovna (1874–1920).” in Biographical Dictionary of Women’s Movements and Feminisms

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hmmmm, how about something off that second prompt list? No 27 - Ritual, for Garcy.

Hello! Thank you for this, and I think that this might be as close to fluff as I get.

*

It starts after they get back from the Rabotnitsa mission. Lucy’s teeth still ache and her ears still ring, and she wasn’t the one who jumped through a window. Something about Flynn’s breathing makes her think that he’s trying not to groan aloud.

(They have been sharing the narrow bed in the narrow room almost since Chinatown. At first, he had taken the couch. After two weeks, she told him not to be ridiculous. They had stayed up late, nodding over piles of books. She had bitten back the question Are you all right? four times, and then stopped counting. “I should…” she had begun, and been cut off by his “Stay.” And in the ringing, dreadful silence she had realized that if she slept alone, next to the Lifeboat, he would not have assurance that she was safe. So Lucy had nodded, and learned how to fit between the steel of the wall and the curve of his arm.)

So here they are, with Flynn’s heartbeat under her ear and his muscles still tense. “It’s hard,” says Lucy softly.

“Hmm?”

“To imagine what comes after.”

“Yes.”

Lucy swallows, and forces herself to breathe deeply before replying (he must not hear in her voice that she fears for him, that she aches for him though she has no right to do so, and that this is almost worse than thinking about her mother’s empty house.) “It’s one of the things I challenge my students to do,” she says. “To imagine what comes after they sit through Colonial and Revolutionary America. What do they want to have discovered? What do they want to do with that knowledge?”

Flynn hums softly; she hopes she’s right in thinking that he also relaxes slightly. “Have I mentioned recently that you’re a genius?”

“Thank you. I know it sounds cheesy,” says Lucy, “but I think we should do the same thing. Imagine what comes after. One thing we want — how does that sound?”

The silence is too long, this time. Unambiguous is the quickening of his pulse, the tight control he keeps over his breath. But: “All right,” says Flynn at last.

“Coffee,” says Lucy promptly. “I want coffee at my favorite coffee shop. I like yours,” she adds quickly. “And it’s far better than coffee made in an ancient drip machine from underground water has any right to be. But I want stupid latte art and stupid flavored lattes, specifically the seasonal one that has carrot and turmeric in it. There. Your turn.”

He takes a deep breath, and she has time to fear his answer. The unspoken rule is, of course, no families. She hadn’t mentioned Amy. But still.

“The Ash Wednesday service,” says Flynn at last.

“What?”

“The Ash Wednesday service,” he says, more steadily. “In my own language. I repent, my God, of all my sins, and my heart cries out, for I have grieved thee. But greater is thy mercy than my transgressions.”

Lucy tells herself that she should find words. And then she thinks that perhaps there are none. She covers his hand with her own, and like that, they fall asleep.

After the Titanic, she asks it still shivering. “Tell me what you want after this.”

He looks at her for a long moment, and then says: “Mountains. To hike up into the mountains, and to see the sea spread out below.”

“I want,” says Lucy, “to go out on the bay. Mom always scoffed at it. But I would like to go out on the water. It’s the opposite of being shut in, isn’t it? I’d like to be out on the bay at sunset.” She nudges him with her shoulder. “Close enough to land to swim back in an emergency.”

“And no icebergs,” observes Flynn, with perfect gravity; and she leans up, and kisses him.

*

“Lucy,” says Flynn after Antietam, “what do you want after this?”

For you never to get blown up ever again. Lucy takes a deep breath. “I think I would like,” she says, “to do a tour of some of the battlefields. Pennsylvania, Virginia, diner food, tourist tat, photos to use in my lecture slides… We could go in autumn, and do apple-picking at the same time. And I’ve never seen the leaves change properly. Typical Californian.” She realizes only belatedly that she has said we, has presumed he’ll be with her.

“That sounds nice,” says Flynn quietly.

He is silent for long enough that she says: “Your turn.”

“Music.”

“Music?”

“In a club. Not — not a modern club, but a place with good jazz, good whisky. That would be nice.”

“Yes,” agrees Lucy.

*

“I want,” says Lucy, after the 1910 mission, “for you to take me dancing.”

Lightly he kisses her hair. “Is it against the rules to wish for the same thing?”

“Mm, I think so.”

“May I wish to take you for dinner beforehand?”

“You may.”

“Thank you.”

*

She is lying on top of him, after Hanoi in 1955. “I want you to stay,” says Lucy. “I don’t care if I’m breaking the rules. I want you to stay. I want to go on bike rides with you, and I want you to laugh at my cooking, and I want…” She breaks off. She clutches his shirt with both hands, and allows herself to cry into it.

“Yes,” says Flynn simply. “Shall we have a tandem bicycle?”

She chokes on her laughter. “You don’t really want that. I’m not nearly coordinated enough. We’d fall over.”

“In that case,” says Flynn gravely, “I say only that I would like to try it once.”

“On your own head be it,” says Lucy, and he kisses her, and they speak no more that night.

*

“Two kids,” says Lucy, after they go to Savannah, in 1859. “Or three. I want to read them Winnie the Pooh and history books and Anne of Green Gables. Two kids. Or three.”

Flynn’s free hand finds its way into her hair. She can feel his breath quickening beneath her. “Fairy tales,” he says, “in all the languages I know. Živjeli su sretno do kraja života.”

“I hope that’s Croatian for ‘And they lived happily ever after.’”

“It means more than that,” says Flynn. “It means that they lived well.”

Lucy reaches for him in the dark. “Say it again,” she demands; and he does.

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We found another fabulous fashion design that was created in 1924. Enjoy!

Rabotnitsa, Issue no. 3, 1924

Klucis, Gustav, 1895-1938, Russian, Latvian [artist]

Russian

1924

HOLLIS number: 8001294915

#fashion#fashiondesign#fineartslibrary#harvardfineartslibrary#harvardfineartslib#Harvard#harvard library#russianfashion#publicdomain

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Facebook post (2021-12-03T22:02:42.000Z)

Am ended shared in my blog posts about cook,and health from press Rabotnitsa, am sure on holidays you can cook something from these posts and share with an other. Next, my posts about point massage and meridians.Feel free share any posts, print, search any on my blog too.

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

Photo by A. Osipov, as seen in Rabotnitsa [Working Woman] from 1962.

206 notes

·

View notes

Text

WOMEN & THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION: HOW BOLSHEVIK WOMEN ORGANIZED FOR SOCIALISM & THEIR OWN EMANCIPATION

By Rozh Em

[International Working Women’s Day march, Petrograd, Russia. (8 March 1917) (Public Domain)]

It is important for us, as revolutionaries of this generation, to honour the crucial role women played in both building the revolution and shaping the politics of the Soviet Union in the years following.

One hundred years ago, on February 23rd 1917, 50,000 women poured out of factories and onto the streets, sparking the first revolution in Russia that eventually led to the downfall of the Czar. It was on International Women’s Day that textile workers organized a labour strike with a strong anti-war message to condemn the exploitative and oppressive conditions most people were subjected to during the Czarist era. Essentially, this movement not only brought women together, but also masses of people who simply called for bread and peace. It became the catalyst for one of biggest revolutions that historically changed the world. However, the role of women and the women’s movement during the Russian Revolution, and the years following, are often undermined by bourgeois historians who tend to frame the revolution as a ‘masculine’ movement. Some historians, such as Richard Piper, even go so far as to argue that the revolution was “a coup” by a small portion of radical, male intellectuals, rather than it being a mass working class movement.1 This is because bourgeois historians do not focus and emphasize enough that the working class was organizing for many years, demanding basic rights. Therefore, contrary to opinions that call the women’s movement and the protest of February 23rd ‘minor’ or ‘almost accidental,’ women workers were in fact crucial to the Revolution. They were organizing themselves, creating unions and getting ready to fight militantly to alleviate their hardships years before the 1917 Revolution. Furthermore, after the revolution, the role Bolshevik women took in shaping the Soviet Union is often overshadowed by the role men played. Revolutionary women, such as Alexandra Kollontai, Inessa Armand and Nadezhda Krupskaya were only some of the many influential women that both shaped the revolution and the Soviet Union in the years following. As such, women not only played an integral role in the Russian Revolution, but their fight for emancipation and social change became yet another revolutionary development in the Soviet Union. Bolshevik women fought hard within the Party to put women’s emancipation on the Soviet Union’s socialist agenda. This article will assess how revolutionary women in Russia, particularly those in the Bolshevik Party, began organizing the working class for a historic revolution that both improved their own conditions and changed the course of the world.

“Bolshevik women fought hard within the Party to put women’s emancipation on the Soviet Union’s socialist agenda.”

To start, it’s important to recognize that the increasing oppression working-class women were facing led them to get more involved in key labour movements. During the Czarist era, women were marked as ‘backwards’ segments of society, and this misogynistic ideology justified the hyper-exploitation of women in Russia, leaving many without opportunities to get an education or the training needed to become skilled workers. Women were also known to be the key laborers in the household — confined to childbearing and constantly providing for their husbands. In the book, Women and Work in Russia, Jane McDermid and Anna Hillyar mention that the economic changes after the abolition of serfdom in Russia resulted in many families facing growing impoverishment, which eventually increased the number of women workers.2 By the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, many women became textile workers or found jobs in domestic services. Between 1901-1913, the number of women working in factories had grown by 59%, whereas for men the increase was only 29%.3 Even in industries where women were predominant, such as the textile industry, they were still paid less than men. Thus, not only were working hours long and exhausting, but the wages women received were barely enough to make a living. Sexual assault and harassment by both foreman and male workers in the workplace was a common occurrence. In 1914, the Bolshevik newspaper for women workers, Rabotnitsa, complained about the brutal and sexually abrasive treatment of women by men within the workforce.4 Historians such as Rose Glickman tells us that the “peasant legacy of female subordination to men was perpetuated in the sexual division of labour at the factory.”5 Subsequently, she argues that gender was significant in the development of the Russian working class because women became one of the most exploited segments of society.6 However, while women in Russia faced increasing oppression and exploitation, they did not remain passive. They began mobilizing themselves for changes.

As industrialization and urbanization began changing the economic system of Russia, there was also a rise of Social Democratic forces, which were predominately made up of radical intellectuals at the time.7 They began stressing the importance of preparing workers to both learn about their exploitation and how to lead their own revolutionary movements. Raising working-class consciousness was key to some of the powerful labour movements in Russia. Therefore, “workers’ circles,” such as The Brusnev circles of 1889-1892, began taking a vital role in the movement to raise the consciousness of the working class.8 Women were joining these organizations in small numbers, and from there, they created their own women workers’ circles. Their organizations mostly concentrated on the industries that women had greater roles in, such as the textile industry.9 The women’s circles also set up literacy workshops, which provided a space for women to read more about their own oppression. By the end of 1890, there were at least twenty workers’ circles.10 Some of the women within these circles radicalized and joined the Bolsheviks as communists took leading roles within these organizations. For instance, Anna Boldyreva, a working-class woman from the Maxwell Textile Mill, later became a representative of the Bolsheviks in trade union struggles after working with them in workers’ circles.11

Essentially, these organizations not only increased the level of class consciousness within the working class, but also became vital tools that allowed workers to collectively organize rallies and strikes, such as the 1890 general strike of textile workers, who were organized under the Ivanovo-Voznesensk workers’ union.12 This strike lasted over two weeks and successfully forced concessions from employers. As Mcdermid and Hillyar mention, women workers “did not simply take spontaneous action,” but were organizers and instigators of the movement, and thus, since the dissatisfaction women felt continued to exist after these strikes, “women were once again prepared to take to the streets” a decade later.13 Therefore, while some historians believe that the Russian Revolution emerged spontaneously, it’s clear that the ways in which women workers organized themselves in the years prior to the revolution explain why they played such an influential role in the large mass movements that occurred in the early twentieth century. So it is important to stress how labour activists put in tremendous effort in the years before the revolution to increase the political consciousness of people and unite them under working class organizations and unions. Although women workers were less organized than men, many were still militantly leading strikes to combat poor conditions, which is why women’s struggles were often correlated with different mass movements in Russia. For instance, women even played an important role during the 1905 movements that started some of the biggest protests against the Czar.

“...while some historians believe that the Russian revolution emerged spontaneously, it’s clear that the ways in which women workers organized themselves in the years prior to the revolution explain why they played such an influential role...”

On “Bloody Sunday,” thousands of workers in St Petersburg marched to the Winter Palace and presented the Czar of Russia with a petition listing off their grievances. Because of the Czar’s violent response to the protesters, resulting in the death of several people, strikes and protests escalated throughout the country. The events of 1905 instigated more labour protests that carried on into 1907 — creating an atmosphere that made revolution possible. In fact, the events that occurred in 1905 led to another “wave of localized industrial unrest culminated in a general strike of Ivanovo workers,” which predominantly included women.14 This eventually led to the establishment of the very first Workers’ Soviet in the country. Among the 151 individuals elected to represent striking factory workers, 25 were women. While this doesn’t seem like a large number, it’s still a victory for women to be taking leadership roles in labour struggles during a time when they were not seen as full human beings. One of the factories, known as the Kashintsev Cotton Weaving Mill, even elected more women than men to the Workers’ Soviet.15 Seven out of the eight elected were women workers. Additionally, within these Workers’ Soviet, only 15.6% of the men belonged to the Bolshevik Party, while 62.5% of the women were part of the Bolsheviks.16

Ultimately, many of the Ivanovo women workers became interested in revolutionary politics and the Bolshevik Party as they got more involved with women’s circles. Despite there being a clash between the feminists of the time and the Bolsheviks, there were also correlations and connections being built between these two forces.17 Women were not simply “duped” by the Bolsheviks, but made the conscious choice of joining their ranks. In fact, women workers were both the forefront of strike actions and among the workers whom the Bolsheviks were building a base with to expand their party, and make it more relevant to the working class.18 Therefore, women’s involvement with the Bolsheviks was arguably part of the reason why the Party became so successful. In her book, Bolshevik Women, Barbara Clements concludes that “Marxism appealed to young women because of its systemic critique of patriarchy.”19 Marxism and revolutionary political groups stood out for women because they were the ones who were properly assessing the historical and structural ways in which women were oppressed. Historian Richard Stites says that the Russian feminists of the time did not have a “binding comprehensive ideology,” other than solidarity.20 He even mentions that the question of emancipation was not clearly “moulded out” by feminists, whereas Marxists had a “more or less complete theoretical framework” on the question of women’s oppression.21 Therefore, many working class women were drawn to the Bolsheviks and began to view socialism as a path towards their emancipation — demonstrating the growing connection between women’s struggles and the fight for socialism. And on the other hand, the international communist movement also began paying closer attention to women’s issues. As Rosa Luxemburg stated in one of her speeches, “women’s suffrage is one of the vital issues on the platform of Social Democracy.”22 The international communist movement’s growing interest in the “women’s question” also explains why women began taking bigger roles within the Bolshevik Party.

[Clara Zetkin (left) & Rosa Luxemburg (right) on their way to the SPD Congress. Magdeburg, 1910 (Public Domain)]

Historically, misogynistic tendencies persisted within the communist movement as well. Many were even afraid of permitting women to vote because of stereotypes that marked them as the most ‘backward’ segments of society.23 For some within the communist and socialist movement, this implied that women were more conservative and religious in comparison to men — meaning that they could potentially vote for right wing forces.24 Nevertheless, this was not the view of everyone inside the revolutionary movement. Within the Second International, Clara Zetkin, well known German revolutionary and one of the founders of International Women’s Day, pushed to make all socialist parties work for the liberation of both men and women. Russian revolutionaries, such as Alexandra Kollontai and Vladimir Lenin, supported Zetkins’s efforts, and also worked hard to bring women’s emancipation to the attention of the Second International. In fact, Russian communists were some of the first to recognize the need to fight for the liberation of women. While some parties were hesitant, there was eventually a formal acceptance by socialist parties of women’s right to work, and the need to create special organs within their parties for women’s political education. 25 Thus, the fight to incorporate the struggle of women into the socialist program led to revolutionary changes within the socialist movement itself.

Soon enough, Marxist literature on the oppression of women, such as the works of Zetkin, Engels and Bebel, was being translated into Russian and distributed to women that took an interest in revolutionary politics. Furthermore, in 1899, Lenin suggested adding “the establishment of full equality of rights of men and women” into the Party Program.26 At the Second Congress in 1903, this addition was officially added. Lenin also demanded that women have the right to maternity leave and claimed that they should be guaranteed work in safe conditions, even suggesting that factories should hire women inspectors to check and ensure that workplaces were not harmful or dangerous spaces.27 Meanwhile, in 1900, Nadezhda Krupskaya, a well-known revolutionary who is most notably referred to as Lenin’s wife, wrote an article called “The Woman Worker,” which was one of the first pieces that analyzed the conditions of Russian women through a Marxist lens.28 She wrote about the overworked and undernourished village woman and peasant women, the underpaid factory women who were often forced into sex-work, and pregnant working class women who did not have job security or the right to maternity leave. Krupskaya’s article was being distributed to women who began participating in labour strikes in hopes of turning these labour movements from economic to political struggles.29 Near the end of the nineteenth century, Krupskaya was involved in organizing underground Marxist study groups, which is where she eventually met Lenin. By 1905, she worked as the secretary of the Central Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Party, and the editorial secretary of the Party’s journal. For years, she exerted herself to teach masses of people who did not receive a proper education, which particularly, but not exclusively, included women. As such, Krupskaya wasn’t only known as “Lenin’s wife,” but as a true revolutionary who helped build the Party.

“By 1913, International Women’s Day was first introduced to [Russia]. To mobilize for this day, Bolshevik women set up city-wide women’s circles to push their anti-war line amongst women workers and the wives of soldiers...”

All the while, Alexandra Kollontai, another key revolutionary figure at the time, was also putting in an immense effort to bring working class women into the Party, or at the very least, to support its aims. She wrote major theoretical work on women’s rights and its relation to socialism. Additionally, she took a leading role in organizing women labour delegates, who had been elected from different factories to participate in trade union struggles. To avoid harassment from authorities, Kollontai disguised her meetings as “sewing circles” or “health talks on the harmfulness of corsets.”30 She would also participate in feminist meetings to draw women into the socialist movement. In addition, other Bolshevik women also headed unions. For instance, Sofia Goncharskaia was the head of the Union of Laundry Workers.31 In addition, Kollontai was one of the revolutionary women, along with other Bolsheviks like Konkordia Samoilova, who pushed to bring International Women’s Day to Russia.32 By 1913, International Women’s Day was first introduced to the country. To mobilize for this day, Bolshevik women set up city-wide women’s circles to push their anti-war line amongst women workers and the wives of the many soldiers who were forced to go to war. Moreover, women in the Bolshevik Party also took leading roles in organizing militant underground committees during the Revolution. Rozaliia Zemliachka and Elena Stasova were two Bolshevikichki who headed underground committees in Moscow and St. Petersburg.33 Elena Stasova ended up becoming the technical secretary of the St. Petersburg committee from 1901-1906.

Around the same time, the Bolsheviks launched Rabotniska, their first women’s magazine that was regularly distributed to women workers. This was one of the first attempts to create a Bolshevik women’s organ within the Party. Inessa Armand, another Bolshevik revolutionary, took a prominent role in creating this journal.34 Throughout her life, Inessa was always attentive to the poor conditions working class women were subjected to because she herself came from a poor working class background. Prior to getting involved with the Bolsheviks, she did charitable work for working class women within feminist circles, and even organized sex workers. Although she did tremendous work to build the Party, to some, Inessa was simply known as “Lenin’s close friend”.35 But the fact is, she was instrumental in making the Party focus more on women’s struggles. Her idea to create a women’s newspaper received strong support from Krupskaya, though other Party members in the Central Committee were initially skeptical of it. Ziva Galili’s article, “Women and the Russian Revolution,” explains how several women within the Bolshevik party worked hard to “convince the Party’s male leaders, in particular V.I. Lenin, to direct resources and energies to the organization of women workers. The centerpiece of that effort was the Bolshevik journal, Rabotniska.”36

History shows us that many women in the Bolshevik Party played key roles in the struggle for socialism. By 1907, 20% of the Party leadership were women, and of the 20%, more than 90% belonged to the Bolsheviks as opposed to the Mensheviks.37 One can even say that the work many Bolshevikichiki put into recruiting working class women led to the growth of the Party itself. However, some “critics of communism, as well as feminists”, view the pro-woman stance of the Party as simply a “ploy to mobilize support for the revolutionary regime.”38 While the Party didn’t explicitly declare that they were ‘feminists’, many women within it did genuinely aim to improve the conditions of women, and for them, their emancipation correlated with class struggle and liberation from capitalist exploitation. For these reasons, some historians refer to the entire 1905-1914 period as the time of the “proletarian women’s movement.”39

Essentially, the ways in which revolutionary women organized themselves was ground-breaking. It was truly an avant-garde movement, and different from many of the influential women’s movements occurring in other places at the time. Revolutionary women in Russia were taking leadership roles in trade unions, becoming head organizers for committees within the Bolshevik party, and writing innovative Marxist literature. Some revolutionary women were even taking part in armed struggle. Accordingly, these women often found themselves leading mass movements, which was radical for a time when women throughout different regions of the world were not even considered to be full citizens. Most importantly, the women’s fight for emancipation during the Russian Revolution led to material and systemic changes for working-class women — a development that was yet to occur anywhere else.

“By 1907, 20% of the Party leadership were women, and of the 20%, more than 90% belonged to the Bolsheviks as opposed to the Mensheviks”

After 1917, women’s emancipation was still on the Bolshevik agenda. The improvement to women’s conditions was arguably in and of itself one of the most revolutionary transformations in the world. In 1920, Lenin stated in Pravda that the “Soviet government is the first and only government in the world to have completely abolished all the old, despicable bourgeois laws which placed women in a position of inferiority to men, which placed men in a privileged position.”40 When the Bolshevik government took power, they implemented legislation that guaranteed the right of women to directly participate in social and political activity.41 Thus, they eradicated institutional barriers that prohibited women from engaging in politics. Only six weeks after the revolution, civil marriage was introduced to Soviet Russia.42 One year after this, in November 1918, Alexandra Kollontai and Inessa Armand organized the first conference of working women, which over a thousand women participated in.43 Eventually, this conference led to a variety of other changes in the country. There was a new civil code on marriage, which recognized equal legal status between husband and wife. In addition, the discrepancy between legitimate and illegitimate children was eliminated. Regulations around divorce were also minimized, making it much easier to go through the process. In January 1918, the Bolsheviks officially founded the department for the “protection of maternity and youth.” This department supported pregnant working class women and new mothers by ensuring a paid 16-week leave from work and setting firm safety regulations at workplaces. The Bolsheviks also created maternity clinics, which helped women raise their children. In the years following, the Soviet Union became the first country in the world to legalize abortion. Sex work was decriminalized in 1922. Sexual education programs were more openly available to youth, and there were health clinics that specifically treated sexually transmitted infections. As time went by, there was less stigma around sexual relations outside of wedlock. The Bolsheviks also created strong laws against sexual assault. Rape was finally defined as “non-consensual sexual intercourse using either physical or psychological force.”44

[Alexandra Kollontai (centre) with female deputies at the Conference of Communist Women of the Peoples of the East. (c. 1920) (Public Domain)]

One of the fundamental ways in which the Bolsheviks successfully transformed the lives of women was through changes they made to the “traditional family structure.” In 1920, Kollontai wrote an article called, “Communism and the Family,” which went as far as calling for ‘free love’ and questioning the traditional family structure.45 She argues that “housework ceases to be a necessity” under communism. She called for the creation of public restaurants and communal kitchens, and thought that children should primarily be supervised by experienced educators through public child care facilities and maternity homes. Above all, she believed in the withering away of the traditional family household, which she thought chained women to oppressive reproductive labour. Though her perspective on the emancipation of women was respected and publicized through women’s circles, Kollontai didn’t manage to influence the Bolsheviks as much as she wanted to. Nonetheless, the Bolsheviks still created more schools, kindergartens, day-cares, playgrounds, and public gardens, which helped working-class mothers by minimizing their work in the household. Because of her astounding commitment to the development of socialism in the Soviet Union, Kollontai eventually became the first ever woman ambassador.

Furthermore, to bring more non-politicized women towards socialism, the Bolsheviks formed the Zhenotdel in 1919, an apparatus within the Party that focused on women’s issues.46 Kollontai and Armand became the directors of this women’s organization, while others, such as Klavdiia Nikolaeva, Konkordiia Samoilova and Nadezhda Krupskaya, also helped launch it. The Zhenotdel was open to any women interested, not just Party members, and it encouraged young women to think about their struggles for full emancipation. Accordingly, education and consciousness-raising were key programs of the Zhenotdel.47 Krupskaya played yet another major role in the revolution by leading education programs initiated by the Zhenotdel. Eventually, she helped initiate 30,000 adult education classes for factory workers and peasants across the Soviet Union.48 The Zhenotdel also published pamphlets and launched the Soviet journal, Kommunistka. In general, women in the Bolshevik party wanted every working-class woman to understand that “the victory of socialism is turning the women worker, like the man, into the conscious creator of her own life.”49 Within a short period, membership in the Zhenotdel grew. By 1922, there were 95,000 delegates, out of whom 24.2% were working class women, 58.5% were peasant women, 9.4% were office workers, and 7.7% were housewives.50 Thus, the Party itself grew and attained 30,434 women members by 1924.51

As time went by, certain obstacles halted some of the developments that were being made. While the Soviet Union progressed in many ways, leaving even Western powers shocked by all the changes made to women’s status in Russia, there were still many setbacks because of the Civil War and imperialist interventions in Russia—all in which put heavy strains on the country and slowed down the revolutionary progress that was taking place. For instance, the Civil War led to mass unemployment, leaving many women without work.52 Thanks to the Zhenotdel, vocational training courses were arranged for women, and more jobs were created for them.53 The Zhenotdel also provided women, particularly single mothers, with housing benefits.54 It became clear that despite these hardships, working class women’s needs were still being taken seriously by the Bolsheviks, who continued to fight for socialism while half the world tried to stop them.

Overall, women contributed immensely to building socialism in Russia. Even though bourgeois historians don’t often associate the Russian Revolution with the many militant women who led and started up some of the first mass protests in 1917, it is important for us, as revolutionaries of this generation, to honor the crucial role women played in both building the revolution and shaping the politics of the Soviet Union in the years following. We must remember that women’s participation and leadership in the labour movement and workers’ circles during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries strengthened both the working class struggle and the movement for women’s emancipation. We must remember that revolutionary women were the ones who organized an anti-war labour strike on International Women’s Day — a strike that became the initial outburst of the 1917 revolution.

Likewise, it would be profoundly incorrect to argue that Bolsheviks solely paid attention to issues pertaining to working-class men. Not only does this erase the tremendous amount of work revolutionary women took in developing a strong Party line on the question of women’s oppression, but also it erases the work many Bolshevik women put in towards their own emancipation. These women dedicated their lives to both socialism and women’s rights. While the Soviet Union was not perfect and more certainly could have been done, as Lenin states, a revolution can take “one step forward and two steps back.” Even though the struggle for women’s emancipation was not close to being over, the accomplishments that did occur in the Soviet Union were revolutionary and historic.

__________________

1. Piper, Richard. The Russian Revolution. New York: Vintage Books, 1990.

2. McDermid, Jane, and Anna Hillyar. Women and Work in Russia 1880-1930. London: Longman, 1998.

3. Ibid. P. 89

4. Rabotnitsa (23 Feb 1914) no. 1, p.11

5. Glickman, Rose. Russian Factory Women: Workplace and Society, 1880-1914. Berkley: University of California Press, 1986.

6. Glickman, Rose. Russian Factory Women: Workplace and Society, 1880-1914. Berkley: University of California Press, 1986.

7. McDermid, Jane, and Anna Hillyar. Women and Work in Russia 1880-1930. London: Longman, 1998.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid. P. 63

10. Ibid.

11. McDermid, Jane, and Anna Hillyar. Revolutionary Women in Russia, 1870-1917. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. P. 109

12. Ibid. P. 110

13. Ibid. P. 111

14. McDermid, Jane, and Anna Hillyar. Revolutionary Women in Russia, 1870-1917. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. P.111

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. Stites, Richard. The Women‘s Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism 1860-1930. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978. P. 289-305

18. McDermid, Jane, and Anna Hillyar. Revolutionary Women in Russia, 1870-1917. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. P. 110-114

19. Clements, Barbara E. Bolshevik Women. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. P. 51

20. Stites, Richard. The Women‘s Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism 1860-1930. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978. P. 233

21. Ibid.

22. Luxemburg, Rosa. Women’s Suffrage and Class Struggle. N.p.: Marxists Internet Archive, 2003. Accessed on April 16th, 2017.

23. McShane, Anne. Did the Russian Revolution Really Change? Film of a Public Form. London: Communist Party of Great Britain, 2012.

24. Ibid.

25. Stites, Richard. The Women‘s Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism 1860-1930. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978. P. 237

26.Stites, Richard. The Women‘s Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism 1860-1930. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978. P. 233-277

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid.

30. Stites, Richard. The Women‘s Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism 1860-1930. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978. P. 254

31. McDermid, Jane, and Anna Hillyar. Revolutionary Women in Russia, 1870-1917. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. P. 110-114

32. Clements, Barbara E. Bolshevik Women. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997

33. Clements, Barbara E. Bolshevik Women. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. P. 68-81

34. Elwood, Ralph C. Inessa Armand: Revolutionary and Feminist. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. P. 105

35. Ibid.

36. Galili, Ziva. “Women and the Russian Revolution.“ Dialectical Anthropology 15, no. 2/3 (1990): P. 121

37. Clements, Barbara E. Bolshevik Women. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. P.66

38. Galili, Ziva. “Women and the Russian Revolution.“ Dialectical Anthropology 15, no. 2/3 (1990): P.123

39. Stites, Richard. The Women‘s Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism 1860-1930. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978. P. 269

40. Lenin, V.I. To the Working Women (Pravda, No. 40. Feb. 21st 1920). Found in The Emancipation of Women: From the writings of V.I. Lenin. New York: International Publishers, 2011. P. 78

41. Ibid. P. 317-346

42. For improvements to women’s conditions see: Engel, Barbara A. Women in Russia 1700-2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. P. 120-143

43. Ibid. P. 143

44. Ibid. P. 145

45. Kollontai, Alexandra. “Communism and Family.“ Komunistka (1920).

46. Clements, Barbara E. Bolshevik Women. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. P. 262-267

47. Ibid.

48. Ibid. P. 215

49. Clements, Barbara E. Bolshevik Women. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. P. 211

50. Kozlova, Natalia. ‚Solving‘ the ‚woman question‘: the case of Zhenotdels in Tver province. Found in Book: Women and Transformation in Russia. New York: Routledge, 2014. P. 100

51. Ibid.

52. Kozlova, Natalia. ‘Solving‘ the ‚woman question‘: the case of Zhenotdels in Tver province. Found in Book: Women and Transformation in Russia. New York: Routledge, 2014. P.99

53. Ibid.

54. Ibid.

#Marxism#Leninism#Feminism#Socialism#October Revolution#Russian Revolution#Kollontai#Krupskaya#Luxemburg#zetkin

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Требуется продавец и работница на склад

В магазин женской одежды требуется продавец и работница на склад. Центр Праги. Оплата 21000 - 27000 чешских крон. Возможность работы с паспортом ЕС, ПМЖ, студентам.

https://gidra.eu/predlagayu-rabotu-v-evrope/trebuetsya-prodavets-i-rabotnitsa-na-sklad_i7600

0 notes

Text

A good Kollontai’s short bio

https://www.marxists.org/archive/kollonta/into.htm

Alexandra Kollontaiby Tom Condit

Alexandra Kollontai was a major figure in the Russian socialist movement from the turn of the century through the revolution and civil war. During periods of exile she was also active as a speaker and writer in Germany, Belgium, France, Britain, Scandinavia and the United States. Born into a wealthy family of Ukrainian, Russian and Finnish background, Kollontai was raised in both Russia and Finland, and acquired an early fluency in languages which not only served the revolutionary movement well, but later led to a career in the Soviet diplomatic service. She played a major role in forcing the Russian socialist movement to organize special work among women and in organizing mass movements of working-class women and peasants, and was the author of much of the social legislation of the early Soviet republic.

Kollontai began political work in 1894, when she was a new mother, by teaching evening classes for workers in St. Petersburg. Through that activity she was drawn into both public and clandestine work with the Political Red Cross, an organization set up to help political prisoners. In 1895, she read August Bebel's Woman and Socialism, which had a major influence on her future ideas and activity.

In 1896, Kollontai saw the open face of capitalist industry for the first time when she visited a large textile factory where her engineer husband was installing a ventilation system. Later that year, she became active in leafletting and fundraising in support of the mass textile strike which rocked the Petersburg area. For the rest of her political career, Kollontai retained her connections with the women textile workers of St. Petersburg. The 1896 strikes established the primacy of working-class revolution in Kollontai's mind.

By 1898, Kollontai was fully committed to Marxism, and left her husband and child to study in Zurich under the Marxist economist Heinrich Herkner. By the time she arrived, Herkner had become a "revisionist" and Kollontai spent much of her time at the university contesting his views. Upon her return to Russia, she wrote a polemic against Edouard Bernstein which was suppressed by the censors. In 1899, she began her underground work for the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP).

In 1900, Kollontai's first articles on Finland appeared. For the next 20 years, she was generally recognized as the RSDLP's foremost expert on the "Finnish question", writing two books and numerous articles, as well as serving as advisor to RSDLP members in the Tsarist Duma and liaison with Finnish revolutionaries. In 1908, she was forced into exile when a warrant for her arrest was issued for advocating the right of Finland to armed revolt against the Tsarist empire; in 1918, she resigned as Commissar of Social Welfare in the Soviet government as a result of her opposition to the delivery of Finland to the white terror under the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

Kollontai, like many Russian socialists, was neutral in the Bolshevik-Menshevik split of 1903. In 1904, she joined the Bolshevik faction and conducted classes on Marxism for it. In 1905, she joined with Leon Trotsky in pressing for a more positive attitude toward the newly-emerged Soviets and in pressing for unity of the party factions. She became treasurer of the St. Petersburg Social Democratic Committee. In 1906, she left the Bolsheviks over the question of boycotting elections to the Duma, an undemocratically-elected parliament of limited power in which she felt it was nevertheless possible for left deputies to raise demands and expose the government's machinations.

From 1905 through 1908, Kollontai led the campaign which has most clearly established her place in history – to organize the women workers of Russia to fight for their own interests, against employers, against bourgeois feminism, and where necessary (as it frequently was) against the conservatism and male chauvinism of the socialist organizations. Through interventions at meetings of the liberal Women's Union, strikes and protests, the foundations were laid for a mass movement.

At the end of 1908, after three months spent evading arrest, Kollontai was finally forced to flee into exile. From then until 1917, she remained outside Russia, although many of her works were published there. She worked as a fulltime agitator for the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), and travelled in England, Denmark, Sweden, Belgium and Switzerland in the period before World War I. In early 1911, she taught at a socialist school organized by Maxim Gorky in Italy.

In 1914 she organized in Germany and Austria against the coming war, and was arrested and imprisoned after it broke out. Released, she moved to Scandinavia and established contact with V. I. Lenin, then in exile in Switzerland. She was a primary organizer of the Zimmerwald Conference against the war in 1915, and her pamphlet "Who Needs War?," directed to front-line soldiers, was translated into several languages.

In 1915, she undertook a four and one-half month speaking tour of the United States to build support for the left-Zimmerwald position on the war (and to try to find a U.S. publisher for her English translation of Lenin's pamphlet "Socialism and War"). She attended a memorial rally for Joe Hill in Seattle and spoke from the same platform as Eugene Debs in Chicago. In all, she spoke at 123 meetings in four languages.

When the February revolution of 1917 broke out, Kollontai was in Norway. She delayed her return to Russia only long enough to receive Lenin's "Letters from Afar" so she could carry them to the Russian organization. From the moment of her arrival, she joined Alexander Shlyapnikov and V. M. Molotov in the fight for a clear policy of no support to the provisional government, against the opposition of Kamenev and Stalin. She was elected a member of the executive committee of the Petrograd Soviet (to which she had been elected as a delegate from an army unit). At a tumultuous meeting of social democrats on April 4, she was the only speaker other than Lenin to support the demand for "All Power to the Soviets."

For the rest of 1917, Kollontai was a constant agitator for revolution in Russia as a speaker, leaflet writer and worker on the Bolshevik women's paper Rabotnitsa. In June she was a Russian delegate to the 9th Congress of the Finnish Social Democratic Party and reported back to the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets on the national question and Finland. During this period she joined other women activists in pressing the Bolsheviks and the trade unions for more attention to organizing women workers, and helped lead a citywide laundry workers strike in Petrograd.

In October 1917, Kollontai participated in the decision to launch an armed uprising against the government and in the revolt itself. At the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, she was elected Commissar of Social Welfare in the new Soviet government. In 1918 she lead a delegation to Sweden, England and France to raise support for the new government. Upon her return, she argued against ratification of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and resigned from the government, feeling that the unity of the Commissariat would be jeopardized by having a member in opposition on such a crucial question. For the rest of 1918, she was active as an agitator and organizer, and played a key role in organizing the First All-Russian Congress of Working and Peasant Women (November 1918).

Throughout 1919, although ill with heart and kidney disease and suffering from typhus, Kollontai kept a grueling schedule of meetings, speeches and writing. She served as a delegate to the First Congress of the Communist International, President of the Political Department of the Crimean Republic, Commissar of Propaganda and Agitation for the Ukraine, and an activist in the newly-formed Women's Section of the Communist Party (the zhenskii otdel, or "Zhenotdel" for short), which she, Inessa Armand and Nadezhda Krupskaya had played major roles in founding.

Kollontai's illness continued through much of 1920, but by November she had become head of the Zhenotdel following the death of Inessa Armand, and at December 8th All-Russian Congress of Soviets she was elected a member of the Executive Committee. At that congress, she joined the "Workers' Opposition," an opposition tendency in the Bolshevik Party opposed to what they saw as the increasing bureaucratization of the Soviet state. The Workers' Opposition, which had majority support in the Metalworkers' Union and the Ukrainian Communist Party, was banned along with all other factions at the 10th party congress in March 1921, but its members continued to be active as leaders of both the Bolshevik Party and the Soviets. Kollontai was re-elected to the All-Russian executive committee of the Soviet in December. In 1922, she was one of the signers of the "Letter of the 22" to the Communist International protesting the banning of factions in Russia.

In 1922, Kollontai was appointed as advisor to the Soviet legation in Norway. From then until her retirement for health reasons in 1945, Kollontai was effectively in exile as a diplomat, and her views on the status of women were marginalized and trivialized in the USSR itself. As ambassador to Norway and Sweden, as a trade delegate to Mexico, as a delegate to the League of Nations, and as negotiator of the Finno-Soviet peace treaty of 1940, she served the USSR with what was generally regarded as great finesse. From 1946 until her death in 1952, she was an advisor to the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Tom Condit

0 notes

Note

Lucy and Flynn + I

This was fun! Disclaimer: I’m actually not sure that Poliksena Shishkina-Iavein was involved with Rabotnitsa, as early twentieth-century Russian feminism could be quite divided along class lines, but the idea was too good to pass up. (More on her and Russian feminism here, here, and here.)

All Lucy can think is, stupidly: that’s a bomb. “Don’t,” she says, and her lips tremble around the word, and her extended hand trembles. They’ve come too late; she wasn’t quick enough; she should have known where in Moscow to look for the Rabotnitsa offices, and now they’re too late. Lucy knows the newspaper doesn’t have long — a few issues before it’s shut down. But the woman currently staring down the bomb as though it’s a man with uninformed opinions has decades of work ahead of her. Or she should.

Lucy glances over at Flynn. He’s been translating for her, and is now addressing Poliksena Shishkina-Iavein in tense, impassioned Russian. The other woman’s jaw is set. Lucy has to admire Rittenhouse’s attention to detail. This is no high-tech, remote-controlled explosive. This is the kind of thing that anarchists terrified the political establishment of Europe with: homemade and crude, with nothing predictable about its workings, nothing to tell you whether or when it might go off. Lucy had hoped Flynn’s knowledge of explosives might give them some chance of escape she can’t yet see. But he meets her eyes, and simply shakes his head.

Lucy swallows, blinks away tears. This is it, then. This is how she’s going to die: on a beautiful spring day in 1914, alongside Russia’s first female gynecologist and the man who’s become her closest ally, her unlikeliest friend.

“Flynn,” says Lucy, “I…” Before she can finish the thought (I’m so sorry, I’m glad you’re here, I’m so sorry), he has taken Dr. Shishkina-Iavein around the midriff, and — it takes Lucy a moment to process — launched himself out the window. The next instant, she is standing alone with the ring of shattering glass, the cries from the street, and the ticking bomb. Well. With one backward glance at the explosive device on the table, Lucy grabs as many article proofs as she can, stuffs them into her shirtwaist, and begins to climb out of the window. She is grateful for the gloves that allow her to gingerly grasp the window frame, with its jagged edges. She still lands a little awkwardly on the pavement, but she doesn’t think her ankle is twisted. Thank goodness they were on the first floor.

“Lucy!” bellows Flynn, and she crouches against the wall, and the blast goes off.

Coughing and dazed and deafened, her next coherent thought is: at least it wasn’t a very good bomb. The front of the building is almost entirely intact. Out of the shattered window have flown pieces of furniture, scorched confetti that are all the remains of Rabotnitsa. Fluent Russian cursing tells Lucy how to orient herself. Poliksena Shishkina-Iavein is standing up, vigorously brushing herself off, and no less vigorously commenting on the state of things generally. Lucy stumbles a little, going forward. Is he…? Flynn is, it turns out, getting to his feet unaided, albeit more slowly than his companion and cargo. He staggers slightly when he gets there, but he meets Lucy’s eyes, and grins. Lucy lets out a breath.

“Ah,” says Poliksena Shishkina-Iavein, “ma chère mademoiselle…” and begins, rather astonishingly, to talk to Lucy in rapid if accented French about the goals of the feminist movement and the importance of international solidarity. As they head down the street arm in arm, Lucy reflects that this would be a surreal experience even if she weren’t still a little light-headed from, oh yes, nearly getting blown up.

“Il est un peu fou, celui-là,” says Dr. Shishkina-Iavein, “mais c’est un homme précieux.”

“Je suis complètement d’accord,” says Lucy, and it feels like a pale substitute for I couldn’t agree more. He has fallen a little behind them, now, doubtless checking to see if they are being followed, making sure that he can keep an eye on the road ahead of them for potential dangers.

At last they are at the hotel where Dr. Shishkina-Iavein insists that yes, she’ll be quite all right and quite safe, thank you, and it’s been a pleasure, Mademoiselle…?

“Docteur,” says Lucy, flushing slightly. “Docteur, er, Poulain.” Dr. Shishkina-Iavein shakes her hand still more vigorously, proceeds to do the same to Flynn — slightly tactless, Lucy thinks, in view of his cuts — and vanishes, her magnificent posture intact, into the tiled entryway. Flynn’s sigh of relief is audible.

“Well,” says Lucy a little weakly, “we managed it. And we’re French?”

“Yes,” says Flynn. “She — you mentioned that she’d emigrated to Paris after the war, so…” He starts to shrug, winces. “I thought I’d put in a good word. We’re like-minded activists.”

Lucy exhales. “Good.” She wonders how long it will be before she can stop reminding herself to breathe normally. “Are you…?”

“Bruised,” says Flynn wryly, “but I’ll recover.”

Lucy swallows, and steps towards him. “You look…” Tired. Like a criminal. Like a hero. “You look a mess.”

“I’m sure.”

Very carefully, she reaches up to brush broken glass from his shoulders, from his sleeves. He shivers slightly under her touch, and she wonders if it is only the aftermath of shock. “We should head back to the Lifeboat,” she says.

“Yes,” agrees Flynn; and so, arm in arm, they do.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lucy and Flynn + I

This was fun! Disclaimer: I’m actually not sure that Poliksena Shishkina-Iavein was involved with Rabotnitsa, as early twentieth-century Russian feminism could be quite divided along class lines, but the idea was too good to pass up. (More on her and Russian feminism here, here, and here.)

All Lucy can think is, stupidly: that’s a bomb. “Don’t,” she says, and her lips tremble around the word, and her extended hand trembles. They’ve come too late; she wasn’t quick enough; she should have known where in Moscow to look for the Rabotnitsa offices, and now they’re too late. Lucy knows the newspaper doesn’t have long — a few issues before it’s shut down. But the woman currently staring down the bomb as though it’s a man with uninformed opinions has decades of work ahead of her. Or she should.

Lucy glances over at Flynn. He’s been translating for her, and is now addressing Poliksena Shishkina-Iavein in tense, impassioned Russian. The other woman’s jaw is set. Lucy has to admire Rittenhouse’s attention to detail. This is no high-tech, remote-controlled explosive. This is the kind of thing that anarchists terrified the political establishment of Europe with: homemade and crude, with nothing predictable about its workings, nothing to tell you whether or when it might go off. Lucy had hoped Flynn’s knowledge of explosives might give them some chance of escape she can’t yet see. But he meets her eyes, and simply shakes his head.

Lucy swallows, blinks away tears. This is it, then. This is how she’s going to die: on a beautiful spring day in 1914, alongside Russia’s first female gynecologist and the man who’s become her closest ally, her unlikeliest friend.

“Flynn,” says Lucy, “I…” Before she can finish the thought (I’m so sorry, I’m glad you’re here, I’m so sorry), he has taken Dr. Shishkina-Iavein around the midriff, and — it takes Lucy a moment to process — launched himself out the window. The next instant, she is standing alone with the ring of shattering glass, the cries from the street, and the ticking bomb. Well. With one backward glance at the explosive device on the table, Lucy grabs as many article proofs as she can, stuffs them into her shirtwaist, and begins to climb out of the window. She is grateful for the gloves that allow her to gingerly grasp the window frame, with its jagged edges. She still lands a little awkwardly on the pavement, but she doesn’t think her ankle is twisted. Thank goodness they were on the first floor.

“Lucy!” bellows Flynn, and she crouches against the wall, and the blast goes off.

Coughing and dazed and deafened, her next coherent thought is: at least it wasn’t a very good bomb. The front of the building is almost entirely intact. Out of the shattered window have flown pieces of furniture, scorched confetti that are all the remains of Rabotnitsa. Fluent Russian cursing tells Lucy how to orient herself. Poliksena Shishkina-Iavein is standing up, vigorously brushing herself off, and no less vigorously commenting on the state of things generally. Lucy stumbles a little, going forward. Is he…? Flynn is, it turns out, getting to his feet unaided, albeit more slowly than his companion and cargo. He staggers slightly when he gets there, but he meets Lucy’s eyes, and grins. Lucy lets out a breath.

“Ah,” says Poliksena Shishkina-Iavein, “ma chère mademoiselle…” and begins, rather astonishingly, to talk to Lucy in rapid if accented French about the goals of the feminist movement and the importance of international solidarity. As they head down the street arm in arm, Lucy reflects that this would be a surreal experience even if she weren’t still a little light-headed from, oh yes, nearly getting blown up.

“Il est un peu fou, celui-là,” says Dr. Shishkina-Iavein, “mais c’est un homme précieux.”

“Je suis complètement d’accord,” says Lucy, and it feels like a pale substitute for I couldn’t agree more. He has fallen a little behind them, now, doubtless checking to see if they are being followed, making sure that he can keep an eye on the road ahead of them for potential dangers.

At last they are at the hotel where Dr. Shishkina-Iavein insists that yes, she’ll be quite all right and quite safe, thank you, and it’s been a pleasure, Mademoiselle…?

“Docteur,” says Lucy, flushing slightly. “Docteur, er, Poulain.” Dr. Shishkina-Iavein shakes her hand still more vigorously, proceeds to do the same to Flynn — slightly tactless, Lucy thinks, in view of his cuts — and vanishes, her magnificent posture intact, into the tiled entryway. Flynn’s sigh of relief is audible.

“Well,” says Lucy a little weakly, “we managed it. And we’re French?”

“Yes,” says Flynn. “She — you mentioned that she’d emigrated to Paris after the war, so…” He starts to shrug, winces. “I thought I’d put in a good word. We’re like-minded activists.”

Lucy exhales. “Good.” She wonders how long it will be before she can stop reminding herself to breathe normally. “Are you…?”

“Bruised,” says Flynn wryly, “but I’ll recover.”

Lucy swallows, and steps towards him. “You look…” Tired. Like a criminal. Like a hero. “You look a mess.”

“I’m sure.”

Very carefully, she reaches up to brush broken glass from his shoulders, from his sleeves. He shivers slightly under her touch, and she wonders if it is only the aftermath of shock. “We should head back to the Lifeboat,” she says.

“Yes,” agrees Flynn; and so, arm in arm, they do.

from 'RittenhouseTL' for all things Timeless https://ift.tt/2J5s0SC

via Istudy world

0 notes

Text