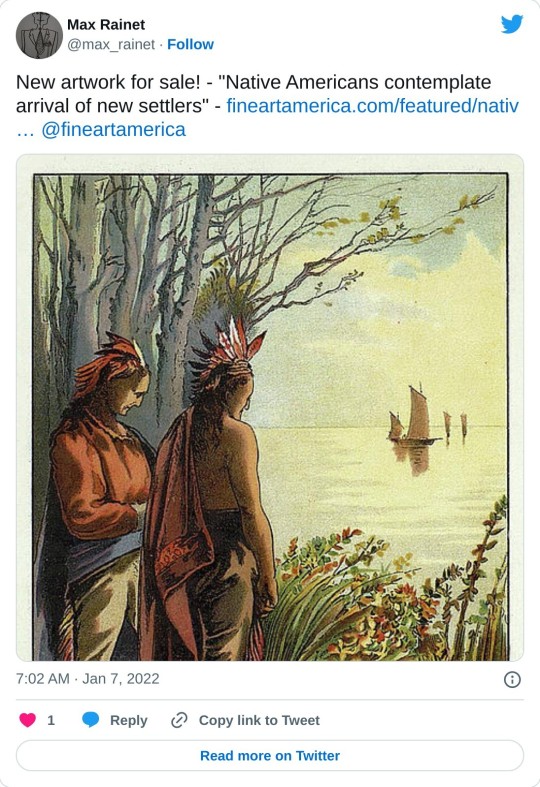

#Native Americans contemplate arrival of new settlers

Text

#Native Americans contemplate arrival of new settlers#Books#Art#Collectibles#For Sale#Max_Rainet at Ebay#bookshop#art dealer#retail guru#RT @max_rainet: New artwork for sale! - - https://t.co/r8xW5YtYmg @fineartamerica ht

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thanksgiving

Turkey, stuffing, and pumpkin pie! A time to be around the ones you love, give thanks, and celebrate the blessings in our lives.

Beloved in the United States, Thanksgiving is a holiday celebrated typically on the fourth Thursday of November. It’s a time to reflect on the year, be thankful, and celebrate with friends and family by enjoying a delicious meal together.

History of Thanksgiving

The origins of Thanksgiving can be traced back to the 1620s, when a group of English settlers, known as the Pilgrims, arrived in what is now Massachusetts. After a harsh winter, the Pilgrims were able to harvest a bountiful crop thanks to the help of the Wampanoag Native Americans. In gratitude, the Pilgrims held a feast to give thanks for their survival and the abundance of food. This event is often considered the first Thanksgiving in America.

Over the centuries, Thanksgiving evolved into a national holiday, officially recognized by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 as a day of national thanksgiving and praise. In 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved the holiday to the fourth Thursday of November, where it remains today. Thanksgiving has become a time to contemplate the blessings in our lives, be thankful for the bounty of food and the love of family and friends.

Thanksgiving Timeline

1621

The first Thanksgiving

The Pilgrims, a group of English settlers, hold a feast to give thanks for their survival and the abundance of food. They invite the Wampanoag Native Americans to join in the feast, which includes wild fowl, venison, and fish.

1863

Thanksgiving officially recognized

President Abraham Lincoln officially recognizes Thanksgiving as a national holiday by issuing a Proclamation of Thanksgiving, setting aside the last Thursday of November as a day of national thanksgiving and praise.

1939

Thanksgiving moved to fourth Thursday

President Franklin D. Roosevelt moves Thanksgiving to the fourth Thursday of November by issuing a Thanksgiving Proclamation, to extend the holiday shopping period and stimulate the economy.

1924

First Thanksgiving Day Parade

Organized by Gimbels Department Store, the first Thanksgiving Day Parade is held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The parade features floats, bands, and live animals, and it becomes an annual tradition.

How to Celebrate Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is celebrated on the fourth Thursday of November in the U.S. It is a time to gather with family and friends, be thankful for all of the good things, and enjoy Thanksgiving, so here are a few ways to celebrate:

Host a Thanksgiving Dinner

One of the most popular ways to celebrate Thanksgiving is by hosting a traditional Thanksgiving dinner. This includes inviting friends and family to gather around the table for a delicious feast of turkey, stuffing, and pumpkin pie. Add some of your own family’s traditional dishes to make it more personal. Don’t forget to set the table with autumn decorations to add a festive touch to the occasion.

Volunteer at a Local Shelter

Thanksgiving is a time to give back to our communities. Many shelters and food banks need volunteers to help serve meals to those in need on Thanksgiving Day, which is a wonderful way to make a difference in your community and to show gratitude for what we have by helping others. You can also donate non-perishable food items and clothing to the shelter in advance of Thanksgiving day.

Start a New Tradition

Thanksgiving is a time to create new memories with loved ones. Start a new tradition, such as a family football game or a pie-making competition.

This is a great way to bond with loved ones, and it will also make Thanksgiving more fun and memorable. You can also make Thanksgiving a day of service by participating in a community clean-up or by visiting a local nursing home to bring cheer to the residents.

Reflect on the Year

Take time to look back on the past year and all the things you are thankful for. This can be done by writing in a gratitude journal, by sharing with friends and family, or by joining a community gratitude event. Reflecting on the year can help us appreciate the good things in our lives and be more mindful of the present moment, and it also helps to set the tone for the upcoming holiday season.

Thanksgiving FAQs

What is Thanksgiving?

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated in the United States, on the fourth Thursday of November. It is a time to reflect on the year, and gather with loved ones to enjoy dinner together.

When is Thanksgiving celebrated?

Thanksgiving is celebrated on the fourth Thursday of November in the United States.

Who celebrates Thanksgiving?

Thanksgiving is celebrated by people in the United States.

How is Thanksgiving traditionally celebrated?

Thanksgiving is traditionally celebrated with a traditional meal of turkey, stuffing, and pumpkin pie, with family and friends.

When did Thanksgiving become a national holiday?

Thanksgiving officially became a national holiday in 1863 when President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed the last Thursday of November as a day of national thanksgiving and praise.

Source

#Port#Bailey's#Swiss Cheese#Lozärner Birrewegge#homemade stuffed turkey#white colonialism#23 November 2023#original photography#fourth Thursday in November#sparkling wine#Beringer Vineyards#Domaine Carneros#travel#USA#Jacobs & Co. Steakhouse#Toronto#vacation#food#restaurant#cream corn#Chardonnay#Napa Valley#Thanksgiving Day

0 notes

Link

It is hard to give up something you claim you never had. That is the difficulty Americans face with respect to their country’s empire. Since the era of Theodore Roosevelt, politicians, journalists, and even some historians have deployed euphemisms—“expansionism,” “the large policy,” “internationalism,” “global leadership”—to disguise America’s imperial ambitions. According to the exceptionalist creed embraced by both political parties and most of the press, imperialism was a European venture that involved seizing territories, extracting their resources, and dominating their (invariably dark-skinned) populations. Americans, we have been told, do things differently: they bestow self-determination on backward peoples who yearn for it. The refusal to acknowledge that Americans have pursued their own version of empire—with the same self-deceiving hubris as Europeans—makes it hard to see that the US empire might (like the others) have a limited lifespan. All empires eventually end, but maybe an exceptional force for global good could last forever—or so its champions seem to believe.

The refusal to contemplate the scaling back of empire shuts down what ought to be our most urgent foreign policy debate before it has even begun. That is why these two new books are so necessary, and so welcome: they are the most serious efforts since Chalmers Johnson’s Blowback series (2004–2010) to reopen the question of American empire by taking for granted that it exists. Victor Bulmer-Thomas’s Empire in Retreat maintains that America has harbored imperial ambitions since its founding, and argues that its focus shifted in the twentieth century, from acquiring territory to penetrating foreign countries and influencing their governments to support US strategic and economic interests. David Hendrickson’s Republic in Peril sees that shift as the result of a decisive embrace of interventionism, aimed at extending US power throughout the world.

Both authors think withdrawal from overextended military commitments could strengthen America. Bulmer-Thomas, a British diplomat and scholar, recommends it as a pragmatic adjustment to shrinking support for US empire at home and abroad. Hendrickson, a political scientist at Colorado College, provides a theoretical rationale for it, exploring the possibility of what he calls a new internationalism, based on respect for the sovereignty of other nations. Yet even as they catalog the many signs of imperial decline (economic, political, cultural), neither is sanguine that American policymakers can manage a graceful retreat.

Bulmer-Thomas begins by recounting the rise of the US territorial empire. He shows that America’s relationship with the land it acquired during westward expansion resembled the relationship between European countries and their colonies abroad. The United States, like European colonial powers, subjugated (and nearly exterminated) aboriginal populations; used military occupation as a buffer between white settlers and rebellious natives; and established only limited representative governments in their occupied territories. One resident of America’s territories complained that they were treated like “mere colonies, occupying much the same relation to the General Government as the colonies did to the British government prior to the Revolution.”

Most textbooks date the beginning of America’s overseas expansion to 1898, when it acquired sovereignty over Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines after the conclusion of its war with Spain. Yet as Bulmer-Thomas shows, the US empire went offshore much earlier. During the 1810s and 1820s, Americans carved out the state of Liberia in West Africa, allegedly as a refuge for free American blacks; the country in fact functioned as an American colony and later as a protectorate of the Firestone Rubber Company. The US established an imperial presence in East Asia as early as 1844, when the Treaty of Wanghia gave it the same privileged access to Chinese ports as the British Empire, and went on to acquire dozens of “guano islands” in the Pacific, where abundant bird droppings provided a rich source of fertilizer.

During the 1890s, the American zeal for distant acquisitions slipped into high gear, as politicians realized they were arriving late to the imperial game. Led by Theodore Roosevelt and other advocates of expansion, they sought land through annexation and collaboration with American business interests (Hawaii) as well as through war with Spain. These acquisitions began as additions to the territorial empire but gradually acquired a more ambiguous character. They came to form the foundation of what Bulmer-Thomas calls America’s “semi-global empire,” built not on territorial acquisition but on the maintenance of client states and various other forms of international interference, including military bases that supported occasional armed interventions in local conflicts and multinational corporations run mostly by Americans.

The Philippines offers a case in point of America’s nonterritorial form of empire. The US declared war on Spain in 1898 with the avowed intention of ending Spanish rule in Cuba, but even before the declaration President William McKinley had dispatched the US Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey to Hong Kong in preparation for an assault on the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay. As soon as war was declared, Dewey moved quickly and crushed the Spanish forces. Their surrender emboldened the Filipino rebels, who erroneously assumed that the US had arrived to liberate them from their Spanish oppressors. The US military quickly disabused them of that delusion by embarking on a ferocious counterinsurgency campaign, which lasted for years and included the systematic torture and slaughter of Filipinos. As many as 250,000 died, but the US imperialists never doubted the sanctity of their cause. “Nothing can be more preposterous than the proposition that these men were entitled to receive from us sovereignty over the entire country which we were invading,” Secretary of War Elihu Root said in 1900 about the Filipino rebels. “As well the friendly Indians, who have helped us in our Indian wars, might have claimed the sovereignty of the West.”

Statehood was never considered during the debate over the Philippines: the only question was whether to establish a naval base at Manila and give the islands back to the Spanish or to annex the entire archipelago. The imperialists won the argument, and after the insurgents were finally suppressed the Philippines became a colony, from which investors in sugar, hemp, tobacco, and coconut oil could gain privileged access to US markets and Filipinos could emigrate to America in search of jobs. By the 1930s, congressional opposition to cheap exports as well as to cheap (and nonwhite) labor created support for Philippine independence, which was finally achieved in 1946. But it came with so many restrictions on trade and so much preferential treatment for American investors—not to mention continued maintenance of US military bases—that “it would be more accurate to describe the Philippines as becoming a US protectorate,” Bulmer-Thomas writes. “Thus, the end of colonialism in the Philippines did not mean the end of US imperial control.”

A similar pattern of indirect imperial control also applied to Central America and the Caribbean. The US dominated that region during the twentieth century through colonies (Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Panama Canal Zone), but more broadly by using its economic influence to interfere in domestic politics and maintain governments that would faithfully serve American interests (as was the case in Cuba until 1959), or by establishing asymmetrical bilateral treaties and customs receiverships—the collection of customs duties by US officials, who then used the money to pay off the debt service owed on American loans. This arrangement survived in the Dominican Republic until 1942 and in Haiti until 1947.

Military interventions underwrote economic domination. Sometimes this involved sending in the US Marines and leaving them in place for decades, as in Haiti from 1915 to 1934. Sometimes it required using military force to crush a rebellion and arranging for the emergence of a cooperative dictator, such as Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, whose brutalities the Americans tolerated as long as he respected US strategic interests in the region. This he did for thirty years, until his attempt in 1960 to overthrow the Venezuelan government cost him US support. Sensing an opportunity, his opponents assassinated him. But the US was still committed to maintaining the imperial relationship, and President Lyndon Johnson sent in the Marines in 1965 to prevent the left-of-center president Juan Bosch (who had been ousted by a military coup) from returning to power.

Johnson’s intervention recalled the conflicts of the early twentieth century, but during World War II and the cold war, US imperial strategies had begun to shift. As the USSR consolidated its power, the US scaled back its pursuit of territory abroad. Instead, it extended its imperial reach through the development of international institutions that would serve its interests but could not also be used against it. At Bretton Woods in 1944, the US initiated the creation of the IMF and the World Bank. Both institutions are headquartered in Washington, and the president of the World Bank has always been an American, by custom if not fiat.

The Point Four Program, drawn from Harry Truman’s inaugural address in 1949, linked the World Bank to the struggle with the Soviet Union for influence in the developing world, where the bank would make loans, with many political conditions attached, to governments and state-owned enterprises (later privately owned ones as well). The requirement that Congress approve these loans ensured that they would reflect what the US government considered its national interest. The United Nations, too, began as an American-dominated institution, though as its membership grew it became progressively harder for the US to control. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, and bilateral treaties worldwide also served American policy under the guise of “collective security” against the Soviet threat.

All these arrangements were fortified by the principle articulated in the Truman Doctrine of 1947—that aggression must be stopped everywhere. Such a commitment “assumes that foreign conflicts feature evil aggressors and innocent victims,” as Hendrickson writes. This unexamined assumption was endorsed and promoted by leaders from both political parties, who helped sustain an atmosphere of perpetual moral crisis during the cold war. The US, working through the CIA, helped to overthrow elected left-leaning governments in Iran, Guatemala, Congo, Brazil, and Chile. Interventions anywhere could always be rationalized as counterinterventions against the allegedly omnipresent Soviet threat.

When the cold war ended, the US’s geopolitical rationale for military interventionism—the need to contain communism—swiftly disappeared, as the country found itself in the heady position of being the world’s sole superpower. This was what is now viewed, with some nostalgia, as the unipolar moment. And yet even in the absence of its longtime ideological rival, the United States continued to conduct foreign policy with the same moral fervor that had informed its actions in the cold war, and with the same confidence that it was a force for global good.

Under the presidency of Bill Clinton, much of official Washington began to believe “that US empire would best be served by the promotion of democracy abroad—or at least an American version of democracy—on the grounds that US security, free market economies and democracies are mutually reenforcing,” as Bulmer-Thomas writes. The rationale for democracy promotion, in the words of Clinton’s first National Security Strategy, was that “democratic states are less likely to threaten our interests and more likely to cooperate with the US to meet security threats and promote sustainable development.” This formulation could work in some circumstances, but not all. Other nations could have good reasons to see democracy promotion as a form of aggression, as Russia did when Clinton sought to expand NATO eastward despite the promises made by his predecessors in the first Bush administration and the warnings of many seasoned diplomats, led by George Kennan.

Establishing “US hegemony across the globe,” in Bulmer-Thomas’s words, was not only about promoting democracy abroad but also about maintaining military supremacy everywhere. In 2000, despite cuts in personnel and the closure of many US bases, the Defense Department committed itself to the pursuit of “full spectrum dominance.” This goal, outlined in Joint Vision 2020, the Department of Defense’s blueprint for the future, meant the worldwide control of land, sea, air, and space, including cyberspace.

The triumphalist mood following the end of the cold war also emboldened neoconservative ideologues. Two of them, William Kristol and Robert Kagan, founded the Project for the New American Century in 1997. Its “Statement of Principles” pledged to “rally support for American global leadership” through “a Reaganite policy of military strength and moral clarity.” This was nothing if not an exceptionalist, even unilateralist creed, based on faith in the uniqueness of America’s position as a global leader. It evoked Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s claim that the US was “the indispensable nation.”

The neoconservatives found their president in George W. Bush. Even before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Bush began to implement neoconservative policies, withdrawing from international organizations and agreements—including (in June 2002) the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty with Russia. This decision, according to Ivo Daalder of the Brookings Institution and other critics at the time, signaled a swerve in US nuclear strategy from deterrence to “war-fighting.”

The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon provided a new enemy, international terrorism, that was even more shadowy and elusive than international communism had been. Widespread panic among Americans and their allies was taken (especially in the US) to justify a permanent state of emergency, with damaging consequences for civil liberties and public debate at home, as well as for the many thousands of civilians who would become “collateral damage” in Iraq and Afghanistan.

After September 11, new rationales for military intervention abroad emerged—not only preventative war against terror (the false justification for invading Iraq) but also R2P (the Responsibility to Protect). As Hendrickson shows, R2P originated in the recommendation of a Canadian government commission and received a modified but contested acceptance by the UN in 2005. R2P provides a virtually blank check for using force on humanitarian grounds—an idea that has little support from non-Western nations. In practice it vitiates a central assumption of international law—that each state has the right to defend itself. In his second inaugural address, Bush spelled out the vision of universal empire behind R2P: “The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world.” This was the Truman Doctrine on steroids.

Hendrickson thinks American disregard for international law helps explain the incoherence of contemporary strategic thought. According to exceptionalist ideology, the US is the primary guardian of international law, on which global stability depends. Yet Hendrickson (like Bulmer-Thomas) makes clear that more often than not, the putative rule-maker has in fact broken rules and acted in ways that it would not tolerate from any other nation.

The American exceptionalist double standard is especially apparent in its current military operations overseas. Consider the battle-ready presence of the US Navy in the South China Sea. Imagine a rival power behaving as aggressively in the Caribbean, lecturing us on our misdeeds (as we have lectured the Chinese) and appointing itself a neutral umpire for the region. A retired Chinese admiral, quoted by Hendrickson, puts the matter succinctly: the US Navy in East Asia is like “a man with a criminal record ‘wandering just outside the gates of a family home.’”

Or take the confrontation emerging on the western border of Russia. The missile defense system installed by NATO on Russia’s doorstep, combined with NATO troops conducting military exercises, could not be more provocative. No great power, least of all the United States, would allow deployments so close to its borders without protest and (probably) retaliation.

While Bulmer-Thomas treats imperial expansion as a continuous feature of American history that has run afoul of historical circumstance, Hendrickson reconstructs an anti-imperial tradition in Anglophone thought, which he calls “liberal pluralism” and recommends reviving in view of our crumbling American empire. In his view, liberal pluralism was embodied in the system of European nation-states (the “Westphalian system”) that emerged from the Thirty Years’ War. It was also the worldview of America’s founders, uniting Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton, and Madison in their suspicion of military adventures abroad. From the liberal pluralist perspective, war is the summum malum of international affairs; respect for the sovereignty of other nations is the best way to avoid it. Sovereignty is the core of international law: every state has the right to defend itself from external attack; none has the right to interfere in the internal affairs of another.

The fact that liberal pluralism discourages interference does not, however, imply that it encourages nations to be passive bystanders in the face of immoral foreign policies, as contemporary political theorists who favor an interventionist approach like to claim. Liberal pluralism “does not,” Hendrickson insists, “dictate indifference to human rights”; it allows states to shelter dissidents and welcome refugees from oppression. “What it does not allow is coercive intervention in a foreign country to secure those rights.”

Hendrickson concentrates his criticisms on the reckless use of military force in foreign lands; he does not dismiss economic sanctions as an alternative. Nor does he rule out interference in extreme situations, such as the threat of genocide. But he insists that such interventions be—as far as possible—multilateral, peaceful, and respectful of international law. He proposes maintaining NATO, but with our nuclear guarantees to its members on a strictly “no-first-use” basis; preserving friendships with allies but also working out “rules of the road with putative adversaries.” He argues that fighting terrorism requires effective policing at home and the support of functioning governments abroad, not their overthrow. The liberal pluralist tradition, in his view, provides intellectual resources for reducing international tension and redirecting national wealth toward urgently necessary aims—rebuilding infrastructure, reviving the welfare state, and addressing the menace of climate change and oceanic catastrophe.

In recent years, popular support for imperial adventures has waned. Large majorities have opposed sending US troops to Libya, Syria, and Ukraine. The percentage of Americans who think it is “very important” that the US should “maintain superior military power worldwide” dropped from 68 percent in 2002 to 52 percent in 2014. And poll respondents ranked military supremacy sixth out of ten among foreign policy aims. The top-ranked goal was “protecting the jobs of American workers.”

The shift in public opinion is a response to a series of failed interventions: efforts at regime change in Iraq, Libya, and Syria have left behind chaos, failed states, terrorist recruits, and endless war. But whatever disagreements they may have had over policy details, all three presidents since September 11 have shared a commitment to US global military supremacy. No major policymaker wants to admit publicly what many suspect privately: that America’s imperial reach has begun to exceed its grasp. Barring a dramatic shift in public discourse, the American empire will not go gentle into that good night; more likely it will, as Dylan Thomas counseled the old, “burn and rave at close of day.”

No one burns and raves more flagrantly than Donald Trump. The failure of blank-check interventions fed the discontent he exploited in the 2016 campaign. Yet his chauvinist posturing has turned out to be little more than a belligerent, unhinged version of the militarized globalism he claimed to displace. So Trump lurches from one outrageous provocation to another while most of his critics repeat the stale formulas of global leadership. Neither side seems to notice that the rest of the world does not want to be led (though some countries may still want their security to be guaranteed by US power). More and more foreign countries are trying to go about their business on their own, even in areas once assumed to be vital to the US national interest—Latin America, the Middle East, the South China Sea, even the Korean peninsula, where the South Koreans have done what American leaders were unable or unwilling to do: initiate diplomacy with North Korea.

Other pillars of American power are also crumbling, as Bulmer-Thomas demonstrates in detail. Multinational corporations are no longer as dependent on American policies abroad for access to foreign markets; General Motors, for example, now sells more cars in China than anywhere else on earth, without benefit of a US presence there. Recent years have seen a steady fall in the US net investment ratio (gross investment less the consumption of fixed capital), both private and public. The consequence has been a decline in infrastructure (including public education), as well as a slowing of innovation and productivity. At the same time, neoliberal politicians in both parties, committed to cutting back the “entitlements” provided by the welfare state and privatizing the public sector, have underwritten the rise of inequality and social immobility. The effect has been to undermine the broad prosperity that was the domestic basis of the semi-global empire.

International institutions, rather than reinforcing American hegemony, challenge it. The UN, the IMF, and the World Bank have all proven unreliable in promoting US interests. At the UN, the US is more isolated than ever on the Security Council, as the dramatic increase in American vetoes shows. Various countries have learned to avoid borrowing from the IMF, with the onerous conditions it imposes, by building up their foreign exchange reserves and paying off existing debts. The World Bank now has two significant rivals, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank (which represents the BRICS countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). The Organization of American States has been superseded, since 2011, by the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, which insisted on the inclusion of Cuba despite US opposition. China is creating its own version of the Trans-Pacific Partnership without US participation, as well as expanding into sub-Saharan Africa and cutting a deal with Nicaragua for another isthmian canal.

Yet Trump and his opponents in the Washington consensus still envision a unipolar world, where the United States can ignore the legitimate claims of rival nations and do pretty much whatever it wants, whether because of its sheer greatness (Trump) or its exceptional goodness (Clinton et al.). Obama was cautious about intervening in Syria and eager to negotiate with Iran, but his administration maintained or intensified commitments to global military supremacy, blanket surveillance, targeted drone assassinations, and modernization of nuclear weapons, as well as engagement in the Middle East and East Asia. Fundamental policies persisted despite Obama’s misgivings.

Neither Bulmer-Thomas nor Hendrickson believes these policies can continue without catastrophe. And it might, in any case, not be in the US’s interests for them to continue. As Bulmer-Thomas reminds us, “Imperial retreat is not the same as national decline, as many other countries can attest. Indeed, imperial retreat can strengthen the nation-state just as imperial expansion can weaken it.” Yet as Hendrickson concludes, “It is crystal clear that the empire is fully determined to stick around,” despite our desperate need to dismantle it. The drift of global events may eventually require the United States to acknowledge the reality of a multipolar world, but we cannot assume that the process will be peaceful. Still, Hendrickson has performed an urgently necessary service in reconstructing the liberal pluralist tradition. He reminds us that there is a humane alternative to contemporary orthodoxy, if we can only recognize it.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanksgiving

THE POPULAR THANKSGIVING STORY

On Thanksgiving Day in many American schools, children re-enact the events that took place during the “first Thanksgiving”. It is usually portrayed as a dinner party in celebration of the first successful harvest where the pilgrims “settlers” and the Native Americans who initially inhabited the land ate together in peace.

According to popular knowledge, these pilgrims were visitors from England, on a mission in 1620, to further explore the new world (West of Europe) and secure religious freedom.

There were about 100 men on the voyage, a mixture of different Europeans, and they journeyed for 65 days before getting to shore. They came and settled in Plymouth (Patuxets) and built a community there without the feared disturbances from the Native Americans.

Photo credit:https://fineartamerica.com/featured/1-pilgrims-first-winter-1620-granger.html

Their first winter the Pilgrims witnessed the death of over half of their men due to poor coverage and adverse health conditions. When winter was over and they were facing a damning period, they had a turn of fortune. They met a Native, Samoset, who could speak English alongside his friend, Squanto.

Squanto helped the pilgrims survive the rest of their stay in the land. He taught them how to tap maple tree sap, taught them to differentiate the medicinal trees from the poisonous ones, and educated them on planting corn and vegetables as well as teaching them to fish and hunt.

When October came, with the guidance of their new friend Squanto, the Pilgrims cultivated corn, fruits, vegetables, and fish to salt and store. It provided them with enough food to survive the winter.

In thanks and celebration, the pilgrims had a bountiful harvest that lasted three days. The native Americans joined them for this feast bringing their native dishes to share. They ate and danced.

Many people consider this the origin of Thanksgiving.

Some continue on with the story, claiming one summer two years later, the pilgrims held a day of fasting and praying to ask for rain and a bountiful harvest. When the rains came and the harvest was once more plentiful, they celebrated their thanks in a festival held on the 29th of November.

THE OMITTED STORY

The Native Americans had encountered the English before the pilgrim's voyage. Early arrivals of Europeans resulted in the deaths of 10- 30 million native Americans. These deaths span several centuries, from Christopher Columbus’ 1492 arrival through the late 19th century. The majority were victims of diseases brought by Europeans for which the native people had no immunity.

Prior to the Pilgrims’ arrival, the local tribe had already lost perhaps 90 percent of its people from possible transmission of bubonic plague by European fishermen.

Tisquantum “Squanto” was one Native American who had previously been in contact with the English. He was kidnapped and enslaved in 1614, only to return to his homeland in New England in 1629 to find his entire Patuxet tribe decimated by smallpox and the English living in their settlement.

It was as a slave that Squanto learned the English that allowed him to interpret for the natives and communicate with the Pilgrims who were living on the land his tribe once thrived on. He and a native named Samoset were able to help their Chief Massasoit negotiate a peace treaty that guaranteed the survival of the Wampanoag people. In exchange for peace, and a promise to fight together in the event of an attack from a warring tribe, or new settlers, the Wampanoag agreed to teach the Pilgrims how to survive on their land.

Schools teach that Pilgrims settled in the wilderness but this is far from the truth. The native people had built a lively settlement with clear fields and clean springs-- which the pilgrims settled in after the original inhabitants had been wiped out due to diseases brought by previous Europeans.

Many references, especially from the settlers journals, show that in their initial interactions, when the Natives went out during the day, the Pilgrims robbed their houses and took things varying from fruit and meat to tools and weapons. They raided their storage houses and their fields. Many were killed during skirmishes. Settlers also allegedly raided graveyards for things they could barter or sell back.

Their relationship was hostile and their peace was forged not assumed.

In fact, of the many diaries recovered, all but one--Winslow’s-- account said that during the infamous feast, the settlers in their exuberance fired gunshots in the air. And it was in response to these gunshots--which the Natives thought were distress calls, that they came upon the feast. There is no historical evidence proving the Native Americans were invited, or sat down and ate with the Pilgrims.

They did not live happily ever after, Their relations eventually deteriorated, culminating in a war between the tribe and colonial forces in 1675.

THE TIMELINE

Both Native American and European societies had been holding festivals to celebrate successful harvests for centuries before the pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock, and for centuries after.

The culmination of popularity with the English Thanksgiving festivals came when English soldiers held feasts to celebrate victorious battles and conquered villages and tribes.

In fact, many people believe that the first Thanksgiving stemmed from the feast held to commemorate the end of the Pequot war.

When the Pequot tribe of Connecticut gathered for their annual Green Corn Dance ceremony in 1637, mercenaries of the English and Dutch surrounded their village and attacked them; burning down everything and shooting whoever tried to escape. The next day, the Governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony declared: “A day of Thanksgiving, thanking God that they had eliminated over 700 men, women and children.” The massacre all but wiped out an entire tribe of people who had been thriving for over 1300 years. Those who escaped were later hunted

It is important to note, that the holiday itself wasn’t made official until 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln declared it as a ‘thank you’ for the Civil War victories in Vicksburg, Miss., and Gettysburg, Pa.

“Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be-- That we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks--for his kind care and protection of the People of this Country previous to their becoming a Nation--for the signal and manifold mercies, and the favorable interpositions of his Providence which we experienced in the course and conclusion of the late war--for the great degree of tranquility, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed”

--President Abraham Lincolns Thanksgiving Proclamation..

THE IMPLICATIONS

When one looks at the happenstances: the true experience of the relationship between the Native Americans and the pilgrims, it is not hard to see why Many Native Americans see it as a “day of mourning” due to its popularity during the raids and enslavement of Natives.

The modern-day thanksgiving celebration is a mix of confused traditions and historical stories, resulting in the rendering of a historical event that is more fiction than fact.

With regard to this, many non-natives who understand the cultural implications of the domination of the tradition and villages of welcoming Natives, do not celebrate Thanksgiving. Others celebrate the holiday in blissful ignorance. They use it as an excuse to give thanks for their yearly blessings, to spend the day with their family and friends, play games during the day and eat a popular Turkey dinner in the evening.

painting by Norman Rockwell

As time passes more people are contemplating the historical implications and wondering what exactly it is that they are celebrating, is it a commemoration of the land conquered? a familial gratitude for a successful harvest? a "thank you" to the specific people who ensured 2 victorious battles during the civil war? Or a national holiday that you partake in “just because”?

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Boxing: Knocking Out Racism and Inequality in America

Modern boxing is as antique as America. They grew up together, and prefer America herself, boxing is as majestic as it is brutal. It's as beautiful as it's far primal. From the bloody and outlawed "exhibitions" in New Orleans to the "bare-knuckle" brawls in the shantytowns out West, boxing came of age with America. It has been known as the "Sweet Science" and "the Manly Art of Self Defense," but in the end "boxing is a game of confrontation and combat, a weaponless war," pitting warriors towards each different to do battle within the squared circle Engagement Rings Perth We can trace the records of America's poor and disenfranchised thru the arc of boxing's beyond. Prizefighting is a prism thru which we can view the records and struggles of America's most disenfranchised. Its heroes of legend frequently exemplify the social problems of the day. In many approaches, the fight sport serves as a means of "socioeconomic" development. Author and boxing historian Jeffrey T. Simmons states in Beyond the Ring: The Role of Boxing in American Society: "The succession [of great fighters] had long gone from Irish to Jewish... To Italians, to [B]lacks, and to Latin[o]s, a sample that contemplated the socioeconomic ladder. As every group moved up, it pulled its youngsters out of prizefighting and pushed them into extra promising... Pursuits."

Two warring parties specifically epitomize the warfare in their humans: the brash Irishman John L. Sullivan, and "The Black Menace" Jack Johnson.

Boxing's Origins

Boxing has its origins in Ancient Greece, and was part of the Olympic Games in round 688 BC. Homer makes reference to boxing in the "Iliad." Boxing historian Michael Katz recollects the sports activities primitive origins:

Much just like the first American settlers, prizefighting made its manner to the New World from England. And just like the pilgrims, boxing's early days were often brutish and violent. Sammons states: "Like so many American cultural, social, political, and highbrow establishments, boxing originated in England. In the late 1700s, whilst the sport existed best in its crudest form, prizefighting in Britain assumed an air of class and acceptability.

The early Puritans and Republicans regularly related sport gambling with the oppressive monarchies of Europe, however as American warring parties of entertainment lost ground, the sport quickly started out to develop. In the 1820's and 1830's boxing, often known as pugilism, became a famous recreation among the American "immigrants who were unaccustomed to regulations upon amusements and video games."

As the game grew in reputation amongst the immigrants, so too did the parable of the person. For better or for worse, america is a state weaned on the parable of the character. This is the American Dream, that essential creed that we can all "pull our selves up by means of the bootstraps" and come to be wildly wealthy, outrageously successful, and madly fulfilled. For almost two hundred years the "Heavyweight Champion" turned into the crown jewel of the carrying global, and the physical embodiment of the American Dream. He became the toughest, "baddest guy" on earth, and commanded the world's appreciate.

Sammons states: "[T]he bodily man nevertheless stands for the capability of the person and the survival of the fittest. He is the embodiment of the American Dream, in which the lowliest of individuals rise to the top by means of their own initiative and perseverance. The elusiveness of that dream is immaterial; the that means of the dream is in its attractiveness, now not its fulfillment." During the 1880's, nobody embodied the physical guy, or the American Dream, greater than boxing's first remarkable heavyweight champion, John L. Sullivan.

John L. Sullivan and the Plight of the Irish

Sullivan, also referred to as "The Boston Strongboy," became the last of the "bare knuckle" champions. The son of poor Irish immigrants, he changed into a brash and hard-nosed guy who toured the "vaudeville circuit providing fifty dollars to every person who could last 4 rounds with him within the ring." Sullivan famously challenged his audiences by means of claiming, "I can lick any sonofabitch in the residence."

"The Boston Strongboy" became considered one of America's first sports legends whilst he snubbed millionaire Richard Kyle Fox, proprietor and owner of the National Police Gazette and the National Enquierer. Legend has it that one fateful evening in the spring of 1881 while at Harry Hill's Dace Hall and Boxing Emporium on New York's East Side, Fox become so inspired by means of one in every of Sullivan's boxing matches, that the newspaper mogul "invited him to his desk for a commercial enterprise talk, which Sullivan impolitely declined, gaining Fox's hatred."

Sammons states:

Fox was furious and vowed to interrupt Sullivan as well as manage the crown. He did neither; Sullivan beat all comers, together with some Fox hopefuls." Sullivan have become an global celeb and American icon "who had risen thru the ranks without searching down on others. Sullivan did greater than build a personal following, but; he helped elevate the game of boxing. The prize ring now spanned the gulf between decrease and top instructions."

Sullivan have become a image of hope and satisfaction for recent Irish immigrants dwelling in a brand new, antagonistic land. Nearly million Irish immigrants arrived in America among 1820 and 1860. Most arrived as indentured servants and were considered little extra than slaves inside the new u . S .. Of the ones million immigrants, more or less seventy five percentage arrived throughout the "The Potato Famine" of 1845-1852. The Irish fled from poverty, disorder, and English oppression. "The Potato Famine" had claimed the lives of almost 1,000,000 Irishmen.

Author Jim Kinsella states:

America have become their dream. Early immigrant letters described it as a land of abundance and urged others to follow them through the 'Golden Door.' These letters were examine at social activities encouraging the young to sign up for them on this brilliant new us of a. They left in droves on ships that have been so crowded, with conditions so terrible, that they have been called 'Coffin Ships.' (par. 1)

The Irish arrived in America destitute and frequently undesirable. An old saying summed up the disillusionment felt by means of American immigrants in the Nineteenth Century: "I got here to America because I heard the streets have been paved with gold. When I came, I determined out three things: First, the streets weren't paved with gold; 2nd, they weren't paved in any respect: and 0.33, I turned into anticipated to pave them."

Kinsella says:

Our immigrant ancestors had been no longer desired in America. Ads for employment were frequently followed by way of "no Irish need observe." They have been forced to live in cellars and shanties... With [no] plumbing and [no] walking water. These residing conditions bred illness and early death. It changed into predicted that 80 percentage of all toddlers born to Irish immigrants in New York City died... The Chicago Post wrote, "The Irish fill our prisons, our negative homes... Scratch a convict or a pauper and the possibilities are that [we] tickle the skin of an Irish Catholic. Putting them on a ship and sending them home could stop crime on this us of a.

But the Irish arrived in America throughout a time of need. Kinsella continues:

The us of a become growing and it needed men to do the heavy work of building bridges, canals, and railroads. It changed into tough, risky work. A common expression heard a few of the railroad people claimed "an Irishman turned into buried beneath each tie.

John L. Sullivan changed into the pleasure of the Irish during his legendary championship reign among 1882-1892).

Historian Benjamin Rader wrote:

The athletes as public heroes served as a compensatory cultural characteristic. They assisted the public in compensating for the passion of the conventional dream of achievement... And feelings of man or woman powerlessness. As the society became greater complicated and systematized and as fulfillment had to be received more and more in bureaucracies, the want for heroes who leaped to reputation and fortune out of doors the guidelines of the gadget regarded to grow.

During his decade lengthy reign as champion; no person captured the general public interest extra than "The Boston Strongboy." He destroyed Paddy Ryan in Mississippi City, Mississippi for the "Heavyweight Championship of America" in an illegal "boxing exhibition" on February 7, 1882. The championship belt was named the "the $10,000 Belt" and turned into "something healthy for a king." Sammons states: "It had a base of flat gold fifty inches long, and twelve inches extensive, with a center panel inclusive of Sullivan's call spelled out in diamonds; eight different frames eagles and Irish harps; an additional 397 diamonds studded the symbolic decoration."

After receiving the "$10,000 Belt," Sullivan pried out the diamonds and sold it for $a hundred seventy five. He later went on to defeat his arch nemesis Jake Kilrain in the seventy-5th round, marking the very last "naked-knuckle" championship bout in boxing records. Sullivan reigned best till his knockout loss to a more youthful, quicker, extra skilled fighter named "Gentleman" Jim Corbett within the twenty-first round on September 7, 1892 in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Jack Johnson and Black Oppression

Boxing historian Bert Sugar as soon as stated: "Boxing is a ordinary, strange recreation. Bottom line, it's legalized attack, however it has given people at some point of history a danger to better themselves. [I]t has constantly been a game of the dispossessed and of the lowest rung on any ladder." Except for the Native Americans, no organization in American records has been as "dispossessed" as African Americans. They have been stolen from their homes in Africa, and transported beneath deplorable conditions to suffer a life of slavery in America. "From the 16th to 19th centuries, an anticipated 12 million Africans have been shipped as slaves to the Americas. Of these an anticipated 645,000 have been added to what's now the USA. [According to] the 1860 United States Census, the slave population within the United States had grown to 4 million.".

From the primary second they set foot on American soil, life became brutal for blacks in the New World. Although the black slaves received freedom after President Abraham Lincoln issued the "Emancipation Proclamation" on January 1, 1863, it'd be roughly a hundred years earlier than blacks finished complete equality in America. The twenty years between 1880 and 1900 were exceptionally hard ones for blacks in America. Congress handed a chain of anti-civil rights acts, culminating inside the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 ensuring 2nd-elegance citizenship for blacks, and marked the beginning of the Jim Crow generation in America.

Although there were many splendid black warring parties during this twenty-12 months duration, blacks were barred from combating for the heavyweight championship. Sammons writes: "By the 1880's the heavyweight boxing championship symbolized... America's upward thrust to global energy... The holder of the title stood as a shining example of American electricity and racial superiority."

But the retirement of the "granite jawed" and undefeated heavyweight champion James Jeffries in 1905 left a whole in the division. After a slew of uninspiring champions came and went boxing fanatics began to lose interest. By 1907 the time was ripe for the primary black heavyweight contender. The sportswriters of the day believed a black fighter might bring public hobby lower back into boxing, whilst additionally proving "white physical and highbrow superiority."

In 1908 a legend became born, and his call was Jack Johnson.

Jack Johnson, later known as "The Black Menace," changed into an unknown fighter from Galveston, Texas. He would end up one of the finest and most courageous athletes in the history of American sports. He changed into a huge man with a flashy smile and brilliant speed. In and out of the hoop, Johnson changed into large than lifestyles. Although he left school inside the 5th grade, Johnson was a clever and worldly guy. He performed the bow mess around, cherished opera and literature, idolized Napoleon Bonaparte, or even invented and patented a device used to restoration cars. He also cherished speedy cars, fancy fits, and white girls. Worse but, white women cherished him again. When one reporter witnessed a successive parade of ladies leaving Johnson's hotel room, he asked the champ for the secret to his "staying electricity." Johnson answered, "Eat jellied eels, and suppose distant thoughts."

Actor James Earl Jones, who performed the mythical Jack Johnson in the movie Great White Hope states: "He lived life by means of his own regulations together with his balls, his head, and his heart."

0 notes

Text

James Madison and James Monroe: the beginning

During the American Revolution, James Madison and James Monroe proved to be two completely divided individuals: Madison, the statesman and Monroe, the soldier. Each, equally attempting to commit a role to the revolution but working seperately.

By 1780, each procured a life-long friendship with Thomas Jefferson and Madison, at the Continental Congress, heard first word of James Monroe from Thomas Jefferson and another congressman, Joseph Jones. Joseph Jones, another representative from Virginia was the uncle of James Monroe, a heritage which brought the youthful Monroe from poverty at sixteen and into the College of William and Mary.

Edmund Pendleton, an elder Virginian statesman of whom Madison frequently corresponded with while in Congress, wrote to him of results from the legislative elections home. There would be many “new members, amongst others are Monroe and John Mercer, formerly officers, since fellow students in the law and said to be clever.” Twenty four year old Monroe would represent King George County in the upcoming 1782 session of the House of Delegates.

The first mention of James Madison in any letter of Monroe’s was penned to his best-friend John Mercer. Among the phrases he briefs upon one of Mercer’s colleagues, a man seen both by Monroe and his friend as somewhat of a role-model. “Mr. Madison I think hath acquired... reputation by a constant and laborious attendance upon Congress.”

On June 7th, 1783, James Monroe was selected by the legislature to replace James Madison in Congress. For a one year term, Monroe would join Joseph Jones, Thomas Jefferson and John Mercer in the city of Philadelphia. Still by 1783, there failed to be any type of political or personal alliance formed between the two men. Jefferson traveled to Philadelphia with Madison, writing to Monroe of this endeavor. While Madison was headed south, Monroe was headed north, arriving in Annapolis before December 6th.

Before departure to France in 1784, Thomas Jefferson gave both Madison and Monroe free use of his library at any time. The 1784 recess gave Monroe ample time to travel, first heading north, then to the west. At Fort Stanwix, Madison caught wind of Monroe’s journeys ahead of him; to Jefferson he let it be know that “Colonel Monroe has passed Oswego when last herd of and was likely to execute his plan.” In the Autumn of 1784, each man receiving strict urging from Jefferson to construct an ally ship, they both found a common cause and a sympathetic friend in other another.

Each, heard of the other often from near individuals; Jefferson even exuberent to persuade both to relocate their homes to line the Monticello property. Earlier that year, Jefferson suggested a confidential correspondence between the two men. Madison was very close to Monroe’s uncle, Joseph Jones and previously having corresponded with John Mercer, Monroe’s friend from college and war.

Madison and Monroe may even have met the previous June, while they were both members of the “Constitutional Society,”. If they did make another’s acquaintance as members of the Constitutional Society, records of such meeting have been lost. November 7th, 1784, arrived back from his nearly fatal trip west and awaiting a re-convening Congress in Trenton, Congressman James Monroe scribed the first letter to Delegate James Madison. The young man could not of known the future lay just in the palm of his hand, nor that this one letter would commence a political and personal friendship spanning over the next four decades.

“Dear sir, I enclose you a cipher which will put some cover on our correspondence.” By accident or avarice, I was not difficult for letters to fall into the wrong hands. The cipher sent by Monroe was on a separate document containing ninety-nine words, each distinguished to a digit. Before even receiving a reply, Monroe sent a second, far more detailed parchment. “I beg of you to write me weekly and give me your opinion on these and every other subject which you think worthy of my attention.” Seeking advice from a man seven years his senior. Monroe’s second letter told of an accident involving a high-ranking French diplomat strolling about his business on the street of Philadelphia. A French citizen, upset with decisions of their government, decided the best course of action to express his frustration was to approach the diplomat and punch him in the face. It also held information on Western defenses, Native American politics and lamented upon the Committee of the States.

A week after his first letter to Madison, Monroe gathered a reply expressing regret that the two men had been able to travel together from New York an congratulated him on surviving a close brush with death and returning unharmed to Trenton. Comically, Madison shrugged that his vacation had been “extended neither into the dangers nor gratification of yours.” Madison reported that a statewide tax to fund the teaching of Christianity, known as the general assessment, had been proposed in the House of Delegates. Ironically, Madison and Monroe were using the one effective service of the federal government to share their exasperation at the government’s many travails.

While waiting for Congress to act on his extradition proposal, Madison created a mirror resolution for Virginia. He applauded Monroe’s efforts to spearhead the issue on the federal level: “We are every day threatened by the eagerness of our disorderly citizens for Spanish plunder and Spanish blood.”

In the days before everything was set in marble, Madison’s letters to Monroe included matters ceremonial as well as substansive. Both were concerned with the uncertain course of their country. While Madison was attempting to overhaul the state court system and hold Virginia from seizing British property, Monroe was trying to prevent a war with Spain while maintaining the Mississippi River for America. Before Lafayette returned to France at the end of his tour in the 1780s, he wrote to Madison telling him, “Our friend Monroe, is very much beloved and respected in Congress.”

Monroe was in multiple ways Madison’s heir, picking up the unfinished works of the elder statesman. The two were also partners, working tandem and in complete agreement about what was desired to be completed to advance the national cause. When Madison in the House of Delegates passed an instruction to the Virginia delegation in Congress to create an ambassadorship to Spain to secure Mississippi, it was Monroe who chaired the committee. The younger southerner also sat upon in a committee which drafted “instructions to the U.S. Minister to Spain.” He was encouraged from his partner and predecessor in the role of the champion. “The use of Mississippi is given by nature to our western country, and no power on Earth can take it from them.”

Madison wrote to Monroe in April that Massachusetts was pushing Rhode Island to accept the impost. He was hungry for information from the national government, the location where his true interests lay. He pondered upon wether any of the state were paying their share. It became far more crystal that Madison valued Monroe’s friendship and their political connection. “I wish much to throw our correspondence into a more regular course,” Madison’s succeeding dispatch contained a more developed cipher, which Monroe had requested some time before.

Madison told Monroe of his ideas for promoting commerce. He brooded over the variety of currencies used in the thirteen states created barriers to trade. He was concerned about a lack of uniform standards for weights and measures. “Do not Congress think think of a remedy for these evils?” he inquired. Monroe replied with the news that Don Diego of Gardoqui, the Spanish ambassador who had been sent to negotiate the matter of the Mississippi, was expected to arrive in New York at any time. Benjamin Franklin was leaving his post as ambassador to France, and it was expected that Jefferson, already in Europe, would become his replacement. Monroe also notified of his success in moving Congress to recommend that the states of New York, Connecticut, New Jersey and Pennsylvania raise soldiers for the protection of settlers on the frontier. Monroe was making great strides in the issue of development of the West.

Madison was pleased to hear about Monroe’s work on Western policy. He wrote back that the Kentucky district of Virginia would soon be petitioning the legislature for a separation. On June 21st, Madison sent Monroe a copy of the Virginia religious establishment bull, and the two men discussed it while traveling together. True to form, Monroe was impulsive while Madison was extremely cautious. “The part of your letter which has engaged most of my attention is the postscripts which invited me to a ramble this fall. I have had it long in contemplation, to seize occasions as they may arise, of transversing the Atlantic states as well as of taking a taste of the western curiosities.” Madison always sounded as though he were the type to consider every possible objection to an idea. Such obstacles can be found in every situation, but Monroe was as quick to look past them as his friend was to view them.

Monroe wrote from Congress in July, still interested in the prospect of traveling with Madison, perhaps during the upcoming recess. “What say you to a trip to the Indian treaty to be held on the Ohio, sometime in August or September. I have thoughts of it and should be happy in your company.” On July 13th, he made a motion “for vesting the United States with power to regulate commerce between the United States and foreign nations and between the states themselves.” Interestingly, though Monroe would oppose the Constitution of 1787, he pointed to this motion in later years as “the first volume of the laws of the United States, among the preparatory acts leading to a change of the system.”

The two friends would not after all travel together during the 1785 recess. Madison journeyed to Philadelphia and up to New York, just missing Monroe, who'd by the time of Madison’s arrival had left to observe the treaty negotiations on the Wabash. Madison and Monroe, manning their respective stations in the Congress and state government, had done their best to keep America afloat. However, federal government under the Articles of Confederation was a leaky ship, taking the waves faster than they could bail it out. It was time for the two men to divert their attention to mending the flaws in their country’s fabric.

TO BE CONTINUED.

#this is terrible#but I tried my best#you'll get the rest today or in the next few days#madroe#james monroe#james madison#flood pressles box#sincerely anonymous#american history#us history#history#thomas jefferson#John mercer

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imperial Exceptionalism

Jackson Lears February 7, 2019 Issue

Empire in Retreat: The Past, Present, and Future of the United States

by Victor Bulmer-Thomas

Yale University Press, 459 pp., $32.50

Republic in Peril: American Empire and the Liberal Tradition

by David C. Hendrickson

Oxford University Press, 287 pp., $34.95

Theodore Roosevelt, center, during construction of the Panama Canal, 1906

It is hard to give up something you claim you never had. That is the difficulty Americans face with respect to their country’s empire. Since the era of Theodore Roosevelt, politicians, journalists, and even some historians have deployed euphemisms—“expansionism,” “the large policy,” “internationalism,” “global leadership”—to disguise America’s imperial ambitions. According to the exceptionalist creed embraced by both political parties and most of the press, imperialism was a European venture that involved seizing territories, extracting their resources, and dominating their (invariably dark-skinned) populations. Americans, we have been told, do things differently: they bestow self-determination on backward peoples who yearn for it. The refusal to acknowledge that Americans have pursued their own version of empire—with the same self-deceiving hubris as Europeans—makes it hard to see that the US empire might (like the others) have a limited lifespan. All empires eventually end, but maybe an exceptional force for global good could last forever—or so its champions seem to believe.

The refusal to contemplate the scaling back of empire shuts down what ought to be our most urgent foreign policy debate before it has even begun. That is why these two new books are so necessary, and so welcome: they are the most serious efforts since Chalmers Johnson’s Blowback series (2004–2010) to reopen the question of American empire by taking for granted that it exists. Victor Bulmer-Thomas’s Empire in Retreat maintains that America has harbored imperial ambitions since its founding, and argues that its focus shifted in the twentieth century, from acquiring territory to penetrating foreign countries and influencing their governments to support US strategic and economic interests. David Hendrickson’s Republic in Peril sees that shift as the result of a decisive embrace of interventionism, aimed at extending US power throughout the world.

Both authors think withdrawal from overextended military commitments could strengthen America. Bulmer-Thomas, a British diplomat and scholar, recommends it as a pragmatic adjustment to shrinking support for US empire at home and abroad. Hendrickson, a political scientist at Colorado College, provides a theoretical rationale for it, exploring the possibility of what he calls a new internationalism, based on respect for the sovereignty of other nations. Yet even as they catalog the many signs of imperial decline (economic, political, cultural), neither is sanguine that American policymakers can manage a graceful retreat.

Bulmer-Thomas begins by recounting the rise of the US territorial empire. He shows that America’s relationship with the land it acquired during westward expansion resembled the relationship between European countries and their colonies abroad. The United States, like European colonial powers, subjugated (and nearly exterminated) aboriginal populations; used military occupation as a buffer between white settlers and rebellious natives; and established only limited representative governments in their occupied territories. One resident of America’s territories complained that they were treated like “mere colonies, occupying much the same relation to the General Government as the colonies did to the British government prior to the Revolution.”

Most textbooks date the beginning of America’s overseas expansion to 1898, when it acquired sovereignty over Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines after the conclusion of its war with Spain. Yet as Bulmer-Thomas shows, the US empire went offshore much earlier. During the 1810s and 1820s, Americans carved out the state of Liberia in West Africa, allegedly as a refuge for free American blacks; the country in fact functioned as an American colony and later as a protectorate of the Firestone Rubber Company. The US established an imperial presence in East Asia as early as 1844, when the Treaty of Wanghia gave it the same privileged access to Chinese ports as the British Empire, and went on to acquire dozens of “guano islands” in the Pacific, where abundant bird droppings provided a rich source of fertilizer.

During the 1890s, the American zeal for distant acquisitions slipped into high gear, as politicians realized they were arriving late to the imperial game. Led by Theodore Roosevelt and other advocates of expansion, they sought land through annexation and collaboration with American business interests (Hawaii) as well as through war with Spain. These acquisitions began as additions to the territorial empire but gradually acquired a more ambiguous character. They came to form the foundation of what Bulmer-Thomas calls America’s “semi-global empire,” built not on territorial acquisition but on the maintenance of client states and various other forms of international interference, including military bases that supported occasional armed interventions in local conflicts and multinational corporations run mostly by Americans.

The Philippines offers a case in point of America’s nonterritorial form of empire. The US declared war on Spain in 1898 with the avowed intention of ending Spanish rule in Cuba, but even before the declaration President William McKinley had dispatched the US Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey to Hong Kong in preparation for an assault on the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay. As soon as war was declared, Dewey moved quickly and crushed the Spanish forces. Their surrender emboldened the Filipino rebels, who erroneously assumed that the US had arrived to liberate them from their Spanish oppressors. The US military quickly disabused them of that delusion by embarking on a ferocious counterinsurgency campaign, which lasted for years and included the systematic torture and slaughter of Filipinos. As many as 250,000 died, but the US imperialists never doubted the sanctity of their cause. “Nothing can be more preposterous than the proposition that these men were entitled to receive from us sovereignty over the entire country which we were invading,” Secretary of War Elihu Root said in 1900 about the Filipino rebels. “As well the friendly Indians, who have helped us in our Indian wars, might have claimed the sovereignty of the West.”

Statehood was never considered during the debate over the Philippines: the only question was whether to establish a naval base at Manila and give the islands back to the Spanish or to annex the entire archipelago. The imperialists won the argument, and after the insurgents were finally suppressed the Philippines became a colony, from which investors in sugar, hemp, tobacco, and coconut oil could gain privileged access to US markets and Filipinos could emigrate to America in search of jobs. By the 1930s, congressional opposition to cheap exports as well as to cheap (and nonwhite) labor created support for Philippine independence, which was finally achieved in 1946. But it came with so many restrictions on trade and so much preferential treatment for American investors—not to mention continued maintenance of US military bases—that “it would be more accurate to describe the Philippines as becoming a US protectorate,” Bulmer-Thomas writes. “Thus, the end of colonialism in the Philippines did not mean the end of US imperial control.”

A similar pattern of indirect imperial control also applied to Central America and the Caribbean. The US dominated that region during the twentieth century through colonies (Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Panama Canal Zone), but more broadly by using its economic influence to interfere in domestic politics and maintain governments that would faithfully serve American interests (as was the case in Cuba until 1959), or by establishing asymmetrical bilateral treaties and customs receiverships—the collection of customs duties by US officials, who then used the money to pay off the debt service owed on American loans. This arrangement survived in the Dominican Republic until 1942 and in Haiti until 1947.

Military interventions underwrote economic domination. Sometimes this involved sending in the US Marines and leaving them in place for decades, as in Haiti from 1915 to 1934. Sometimes it required using military force to crush a rebellion and arranging for the emergence of a cooperative dictator, such as Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, whose brutalities the Americans tolerated as long as he respected US strategic interests in the region. This he did for thirty years, until his attempt in 1960 to overthrow the Venezuelan government cost him US support. Sensing an opportunity, his opponents assassinated him. But the US was still committed to maintaining the imperial relationship, and President Lyndon Johnson sent in the Marines in 1965 to prevent the left-of-center president Juan Bosch (who had been ousted by a military coup) from returning to power.

Johnson’s intervention recalled the conflicts of the early twentieth century, but during World War II and the cold war, US imperial strategies had begun to shift. As the USSR consolidated its power, the US scaled back its pursuit of territory abroad. Instead, it extended its imperial reach through the development of international institutions that would serve its interests but could not also be used against it. At Bretton Woods in 1944, the US initiated the creation of the IMF and the World Bank. Both institutions are headquartered in Washington, and the president of the World Bank has always been an American, by custom if not fiat.

The Point Four Program, drawn from Harry Truman’s inaugural address in 1949, linked the World Bank to the struggle with the Soviet Union for influence in the developing world, where the bank would make loans, with many political conditions attached, to governments and state-owned enterprises (later privately owned ones as well). The requirement that Congress approve these loans ensured that they would reflect what the US government considered its national interest. The United Nations, too, began as an American-dominated institution, though as its membership grew it became progressively harder for the US to control. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, and bilateral treaties worldwide also served American policy under the guise of “collective security” against the Soviet threat.

All these arrangements were fortified by the principle articulated in the Truman Doctrine of 1947—that aggression must be stopped everywhere. Such a commitment “assumes that foreign conflicts feature evil aggressors and innocent victims,” as Hendrickson writes. This unexamined assumption was endorsed and promoted by leaders from both political parties, who helped sustain an atmosphere of perpetual moral crisis during the cold war. The US, working through the CIA, helped to overthrow elected left-leaning governments in Iran, Guatemala, Congo, Brazil, and Chile. Interventions anywhere could always be rationalized as counterinterventions against the allegedly omnipresent Soviet threat.

When the cold war ended, the US’s geopolitical rationale for military interventionism—the need to contain communism—swiftly disappeared, as the country found itself in the heady position of being the world’s sole superpower. This was what is now viewed, with some nostalgia, as the unipolar moment. And yet even in the absence of its longtime ideological rival, the United States continued to conduct foreign policy with the same moral fervor that had informed its actions in the cold war, and with the same confidence that it was a force for global good.

Under the presidency of Bill Clinton, much of official Washington began to believe “that US empire would best be served by the promotion of democracy abroad—or at least an American version of democracy—on the grounds that US security, free market economies and democracies are mutually reenforcing,” as Bulmer-Thomas writes. The rationale for democracy promotion, in the words of Clinton’s first National Security Strategy, was that “democratic states are less likely to threaten our interests and more likely to cooperate with the US to meet security threats and promote sustainable development.” This formulation could work in some circumstances, but not all. Other nations could have good reasons to see democracy promotion as a form of aggression, as Russia did when Clinton sought to expand NATO eastward despite the promises made by his predecessors in the first Bush administration and the warnings of many seasoned diplomats, led by George Kennan.

Establishing “US hegemony across the globe,” in Bulmer-Thomas’s words, was not only about promoting democracy abroad but also about maintaining military supremacy everywhere. In 2000, despite cuts in personnel and the closure of many US bases, the Defense Department committed itself to the pursuit of “full spectrum dominance.” This goal, outlined in Joint Vision 2020, the Department of Defense’s blueprint for the future, meant the worldwide control of land, sea, air, and space, including cyberspace.

The triumphalist mood following the end of the cold war also emboldened neoconservative ideologues. Two of them, William Kristol and Robert Kagan, founded the Project for the New American Century in 1997. Its “Statement of Principles” pledged to “rally support for American global leadership” through “a Reaganite policy of military strength and moral clarity.” This was nothing if not an exceptionalist, even unilateralist creed, based on faith in the uniqueness of America’s position as a global leader. It evoked Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s claim that the US was “the indispensable nation.”

The neoconservatives found their president in George W. Bush. Even before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Bush began to implement neoconservative policies, withdrawing from international organizations and agreements—including (in June 2002) the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty with Russia. This decision, according to Ivo Daalder of the Brookings Institution and other critics at the time, signaled a swerve in US nuclear strategy from deterrence to “war-fighting.”

The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon provided a new enemy, international terrorism, that was even more shadowy and elusive than international communism had been. Widespread panic among Americans and their allies was taken (especially in the US) to justify a permanent state of emergency, with damaging consequences for civil liberties and public debate at home, as well as for the many thousands of civilians who would become “collateral damage” in Iraq and Afghanistan.