#Miguel Angel Asturias

Text

However life treats you, as time goes by you always

get the feeling that you’ve lost life in the very living of it.

Miguel Ángel Asturias, Men of Maize 1949

Photograph by Rodney Smith

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Our Latin American literature has always been a committed, a responsible literature,” explained Guatemalan novelist Miguel Ángel Asturias in 1973.

The great works of our countries have been written in response to a vital need, a need of the people, and therefore almost all our literature is committed. Only as an exception do some of our writers isolate themselves and become uninterested in what is happening around them; such writers are concerned with psychological or egocentric subjects and the problems of a personality out of contact with surrounding reality.1

It is the bourgeois writers, he wants to say here, who ignore the looting of their resources by the rich behemoth to the north, which then turns around and redeploys those riches on death squads and dictators. It is no surprise, then, that Asturias’s landmark novel, Mr. President, confronts its readers with similar frankness. Mr. President examines widespread corruption around a fictional Guatemalan dictator. But its 1946 debut reflected a delay of more than a decade by the country’s real dictators, who disrupted the novel’s genesis and sent its author into exile. And in this act of suppression, Asturias’s censors and exilers were aided by the US, specifically the CIA.

READ MORE

#latin american literature#guatemala#cia#miguel angel asturias#librarians#shadow ban#soft censorship#cold war

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Somewhere nearby, a neighbor's playing a gramophone. I've never heard it before. I didn't know it existed. Always a first time. There's a dog in the house in back. Maybe two dogs. But someone has a gramophone. Just one. Between the trumpet blasting and the dogs in back obeying their master's voice is my house, my head, me. Being nearby and distant is what defines a neighbor.

— Miguel Ángel Asturias, Mr. President (trans. David Unger)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Achievements, happiness and the passage of time

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about time as ‘a giant wheel rotating through cycles of creation and destruction leading, over aeons, to the birth and death of entire worlds’ [see ‘Aeonian cycles of creation and destruction’ on October 18th, 2023]. I had written previously about Aristotle’s view of time as the measurement of change and how Newton believed that time passes even when nothing…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Link

Neither Gabriel García Márquez nor Mario Vargas Llosa had yet been born when the Guatemalan Miguel Ángel Asturias began to write his first novel, El Señor Presidente, in December 1922. He labored on it for a decade while living in self-imposed exile in Paris, then returned home when the Great Depression left him strapped for money, only to find that his work was unpublishable because the dictator whose reign it portrayed had given way to an even more cruel and oppressive one. When he finally self-published the novel in Mexico in 1946, it was riddled with typographical errors, and a definitive edition did not appear until 1952.

From the beginning, then, El Señor Presidente has been star-crossed. But it also ranks as one of the most important and influential works of modern Latin American literature, a kind of urtext for the celebrated generation of novelists that followed Asturias and gained global recognition in the 1960s and 1970s as members of “El Boom”: García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, Carlos Fuentes, José Donoso, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Julio Cortázar, Augusto Roa Bastos, and several others.

Even a cursory reading of David Unger’s new translation of Asturias’s novel establishes why it has had such an enormous impact. In its pages one can easily discern the origins of two phenomena that the rest of the world has come to associate with twentieth-century Latin American literature: the genre known as the dictator novel and the style called magical realism. In his introduction to Mr. President, Gerald Martin, the leading scholar of Asturias and his work in the English-speaking world, goes so far as to call it “the first page of the Boom” and claims that “it was not Gabriel García Márquez who invented magical realism; it was Miguel Ángel Asturias.” This may seem outlandish to those unfamiliar with Asturias, but it provokes very little argument in Latin America.

Mr. President takes place in an unnamed country tyrannized by an unnamed dictator, but both the place and the time are clearly implied: buried in the text are fleeting references to the quetzal, Guatemala’s national bird, and the World War I battle of Verdun. The identity of “the Constitutional President of the Republic, the Benefactor of Our Country, the Head of the Great Liberal Party, the Liberal Hearted Protector of Our Scholarly Youth” is just as readily deduced: he is modeled on Manuel Estrada Cabrera, who dominated Guatemala from 1898 to 1920 through a combination of intimidation, assassination, corruption, and fraudulent elections.

In dissecting the dictator and his despotic rule, Asturias, born the year after he took power, was writing from a privileged position. After being overthrown in 1920, following a congressional vote that deemed him mentally incompetent, Estrada Cabrera was arrested, tried, and sentenced to life in prison, where he died in 1924. Asturias took part in the popular uprising that led to his downfall and was briefly jailed; then, as a law student, he served as a secretary to the tribunal that judged Estrada Cabrera. In that position, Asturias committed to paper for the first time the horrifying stories of injustice, torture, and murder that he soon drew on for his novel; Martin says he also took a deposition from the fallen dictator in his jail cell.

In interviews near the end of his life, Asturias even credited Estrada Cabrera for his discovery of his vocation as a writer. “At 10:25 PM on 25 December 1917, an earthquake destroyed my city,” he explained in 1970.

I remember seeing something like an immense cloud covering the moon. I was in a cellar, a hole in the ground or a cave, or something like that. Right there and then I wrote my first poem, a goodbye song to Guatemala.

Later, as disaster relief from abroad poured in but went straight into the pockets of Estrada Cabrera and his cronies, “I was really angered by the circumstances under which the rubble was removed and by the social injustice that became really apparent then.” Eventually that prodded the aspiring writer into attempting a piece of narrative fiction, initially called “Political Beggars.”

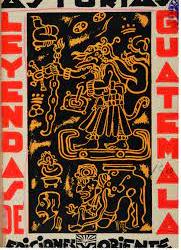

The decade Asturias spent in France, after a brief and evidently unsatisfying stopover to study economics in London, radically changed the nature of the book he set out to write. He had devoted his law school thesis to “The Social Problem of the Indian,” but he began to study ethnology at the Sorbonne under the scholar Georges Raynaud, who encouraged his interest in Mayan culture and mythology; when the fruit of that academic effort, a retelling of pre-Columbian folk narratives called Legends of Guatemala, was published in French in 1931, it came with a glowing foreword by Paul Valéry.

In Paris Asturias socialized with avant-garde literary types like the poets André Breton, Tristan Tzara, César Vallejo, Louis Aragon, and Robert Desnos, and became a committed Surrealist; he also gravitated toward Picasso, whom he would recall holding court at a Montparnasse café and proclaiming, “I deform the world because I do not like it.” So instead of writing the kind of realist social novel then in vogue in Latin America, Asturias ended up creating something much more ambitious, complex, and unconventional.

The plot of Mr. President is deceptively simple, with most of the action taking place over a single week. When a half-crazed beggar accidentally kills a particularly brutal colonel in a fit of rage, the president decides to pin the blame on a general and his lawyer, whose political loyalty he has begun to doubt. This sets in motion a series of interlinked schemes and machinations that result in the imprisonment, torture, death, bondage, or general ruination of assorted government higher-ups, who suspect what is coming, and ordinary citizens, who do not. “We are a cursed country,” one prisoner laments. “Hundreds of men have had their brains blown away by murderous bullets on prison walls. The palace marbles are drenched in the blood of innocent people. Where can we look to find freedom?”

What makes Mr. President so revolutionary is the manner in which Asturias presents a story that contains many of the elements of classic Latin American melodrama, including a doomed love affair between the president’s closest adviser and the fallen general’s beautiful daughter, with “her slanted jade eyes” that “could make ships crash.” But he also repeatedly blurs or disassembles the barrier between reality and fantasy, dreams and waking, genuine and false, past and present, giving readers access to the confused perceptions, fears, and musings of a gallery of unfortunates and scoundrels.

“Half my body is a lie, the other half truth,” a songbird chirps from a pine tree during one of the beggar’s most extravagant hallucinations.

I am both rose and apple. I offer everyone a glass eye and a real eye. Those who see my glass eye see it because they dream; those who see my real eye do so because they can truly see. I am life, the Apple-Rose of the Bird of Paradise. I am the lie in every truth, the truth of all fiction.

As this passage suggests, the great insight that Asturias reached during his interlude in France—and applied to the writing of Mr. President—was that European Surrealism and Mayan mythology did not emerge from separate worlds. Rather, he said, both were generated by the unconscious and could thus be fused, “creating a mixture, and this is the magical part, that I have made use of and benefitted from in my stories.” In a collection of interviews published after his death, he expanded on that notion:

When the indigenous speak of what is unreal, such are the details of their dreams, of their hallucinations, that all of these details converge to make the dream and vision more real than reality itself. That is to say, one cannot speak of this “magical realism” without thinking of the primitive mentality of the Indian, of his manner of appraising manifestations of nature and in his profound ancestral beliefs.

Asturias originally intended to call his novel Tohil, which is the name of a powerful, demanding, and vengeful Mayan deity. In the Popol Vuh, the sacred creation narrative of the K’iche’ people, Tohil is the bringer of fire who, in return for offering warmth and sustenance, insists on absolute fealty from his grateful followers. “In truth, I am your god; so shall it be,” he tells them. “I am your lord; so shall it be.” To placate his jealous ego, he also demands human sacrifice and, when displeased, foments war. In short, Tohil is both an evocation of Estrada Cabrera and a metaphor for all the capricious dictators who have plagued Guatemala and the rest of Latin America since independence was achieved early in the nineteenth century.

In a late chapter of Mr. President entitled “Tohil’s Dance,” an obsequious poet extends that connection in a more modern direction when he proclaims, during a festive night at a bar attended by all the president’s admirers and flunkies, that the Tohil-like head of state is actually “Nietzsche’s prototype, the Superman” who “gives form to a new kind of government: the Super Democracy.” In a hilariously preposterous “Nocturne in C Major to the Super-Duperman,” an extended peroration severely curtailed in Unger’s translation, the poet explains that “Nitche” “genuinely sensed that from Father Cosmos and Mother Nature would be born in the heart of America the first Superman who has ever existed.”

Variations on this template, adapted to differing local circumstances, recur in almost every Latin American dictator novel written after Mr. President, especially those published at the peak of the Boom: Alejo Carpentier’s Reasons of State (1974), Roa Bastos’s I, the Supreme (1974), García Márquez’s The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975) and The General in His Labyrinth (1989), Luisa Valenzuela’s The Lizard’s Tail (1983), and Vargas Llosa’s The Feast of the Goat (2000), among many others. Even a late entry from a much younger, post-Boom writer, Roberto Bolaño’s Distant Star (1996), betrays the influence of Asturias, whom Bolaño once described as “a gigantic writer from a small, ill-fated country.”

Given its brilliance and influence, it continues to be a mystery why Mr. President remains less known in the English-speaking world than the many novels it inspired. One reason may be that more than fifteen years elapsed between its publication in Spanish and its appearance in English in 1963, with the same title it had in Spanish. Unger also points to deficiencies in that first translation, by the English writer Frances Marshall Partridge: “Although lyrical, it is somewhat dated, full of Anglicisms, mistranslations, occasional paragraph omissions, and an overdose of awkward Latinate constructions that may leave readers scratching their head.”

In Partridge’s defense, it should be noted that her enthusiasm for the novel was as vast as her connections to Latin America were tenuous. She is best known as part of the Bloomsbury group (having married Ralph Partridge after Dora Carrington’s ménage with him and Lytton Strachey fell apart) and is remembered mostly for her diaries and memoirs of life in that circle. As a translator, she focused on popular mainstream writers from Spain, such as the novelists Vicente Blasco Ibáñez and Mercedes Ballesteros and the philosopher José Luis López-Aranguren. With someone as inventive and innovative as Asturias, she was clearly in over her head. Whatever possessed her, for example, to translate Pelele, the nickname of the deranged beggar, as “the Zany,” when “the Dummy” would have been a much more appropriate choice?

Unger—who calls that character “the Dimwit”—is much more suited for the daunting task of taking on Asturias and his peculiar vocabulary and frequent shifts of tone. Though he writes in English, he was born in Guatemala, and his own novels, which include Life in the Damn Tropics (2002), The Price of Escape (2011), and The Mastermind (2016), often take place there. Unger has also translated the Popol Vuh and teaches at the City College of New York, including courses on translation. In 2014 he won Guatemala’s top cultural honor, the Miguel Ángel Asturias National Literature Prize, for his body of work. “As a self-proclaimed Guategringo,” he writes that “my work as a translator and fiction writer has been a lifelong attempt to return to my roots, to the land of my birth.”

Unger tells us that his translation of Mr. President aims to

establish, in the American vernacular, the proper relation among words, sentences, and paragraphs so that the author’s startling images, metaphors, and narrative verve may speak directly to the monolingual reader.

For instance, Asturias, perhaps nostalgic in exile for the comforting sensuality of daily life in the tropics, wrote especially beautiful descriptions of both rural landscapes and the sounds and smells of urban life. Unger reproduces these passages magnificently, as at the start of a chapter that portrays the capital stirring to life after a long night:

Daybreak emerged, radiating April’s freshness—outlining roofs and fields with light and bringing the darkened streets back into view. Mules carrying clanking milk cans almost galloped, urged on by the shouts and whips of muleteers. The sunlight reached the cows milked in the entryways of wealthy homeowners and on the street corners where the poor lived. The customers—either energized or about to pass out with sleepy, glassy eyes—waited for milk from their favorite cow, tilting their bottles artfully to get more liquid and less froth. Women carrying fresh bread in baskets passed by, waists twisted, legs stiff, heads sunk into their chests. Their bare feet alternated between steady and slippery steps under the weight of the baskets, piled one on top of the other like pagodas. The fragrance of sweet sesame pastries trailed them.

One of the hallmarks of the novel is the way Asturias mixes these lyrical passages with hallucinatory episodes, some of which draw on Mayan myths. Unger successfully conveys that duality too, as well as the mordantly satirical tone of a chapter called “The President’s Report,” which consists of a series of memos in which ordinary citizens inform on and denounce each other in flat bureaucratic language. Set pieces, such as a vacation trip to the beach the general’s daughter takes with her cousins and a description of a train ride through the jungle, are so vivid that they almost seem to have come from a movie projector.

But Unger has some problems with dialogue. There are passages, especially those involving the president’s henchmen, that sound like exchanges from 1930s gangster films. When a member of the secret police, for instance, disappoints one of his lowlife friends by informing him that the job he wants has gone instead to the boss’s godson, the frustrated office-seeker is told as consolation: “Listen, man, don’t be so down in the mouth over this. I’ll let you know when another cushy job opens up. I swear, on my Mother’s life, something new comes up. There are more jobs than ants in an anthill.” And when the friend remains unsatisfied, the policeman retorts: “Hey, brother, you sure are touchy.”

Also debatable is Unger’s warning that “no contemporary reader of this novel will fail to shudder when encountering slurs against Jews, Arabs, Chinese, indigenous Guatemalans, and gay and transgender people that crop up from time to time.” I confess that I did not even blink, much less shudder, when I read the passages in question, and I am a member of one of the groups being disparaged. The insults are quite tame and indirect compared to what I heard daily on the streets of Chicago growing up, and as Unger acknowledges, they were “rampant during the period Asturias is depicting.” There is really no need to apologize or offer a trigger warning: it would make no more sense to sanitize El Señor Presidente than Huckleberry Finn.

As regards the dialogue, though, the problem may simply be that Mr. President confronts any translator with impossible choices and insoluble challenges. The novel is so full of idiosyncratically Guatemalan words and expressions that even Spanish-language editions come with a glossary of dozens of terms not used elsewhere in Latin America. Additionally, Asturias was trying to capture the flavor of Spanish as it was spoken in his country more than a century ago, during his youth. Imagine, then, the added difficulty of rendering these idioms into English while preserving both tone and multiple meanings.

For example, late in the novel, the unnamed president is drunk and, after he vomits all over his closest adviser, recalls the anger and humiliation he felt as a young attorney working in a “third-rate lawyer’s office, among whores, gamblers,” and what Asturias originally called cholojeras. These are the market women, almost always indigenous, who sell cow, pig, and lamb guts for consumption in soups or the Guatemalan version of chitterlings. Partridge renders this as “offal-sellers,” while Unger prefers “shit-sellers,” although “tripe-peddlers” would be more accurate. But I remember being told by Mayan Guatemalans of my acquaintance that cholojera is also a highly pejorative and often racist term, with almost a caste connotation redolent of India. How to convey all of that in a simple one-word translation?

After Mr. President, Asturias went on to have a distinguished career, both literary and political, serving in the Guatemalan Congress and as a diplomat. In 1949 he published Men of Maize, which Martin considers “even more audacious and visionary” in its blend of Surrealism and indigenous folklore, and during a rare decade of democracy (1944–1954) he was assigned to embassies in Latin America and France. After an American-organized coup put the military back in power, though, Asturias was stripped of his citizenship and forced into exile, where he completed The Banana Trilogy, a cycle of novels about the suffering of indigenous workers on the United Fruit Company’s Guatemalan plantations. He mostly remained abroad and continued to write novels, plays, and poems until his death in Madrid in 1974. In 1967 he became the first Latin American novelist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

So in spite of Mr. President’s long and difficult road to publication, Asturias ended up achieving critical and commercial success. Yet it is never too late to burnish his reputation. As Martin maintains:

Restoring Asturias’s novel to its rightful place in Latin American cultural development and focusing its achievement are long overdue, both as an act of justice and as a contribution to historical and literary truth.

Thanks to Unger’s translation, the anglophone reader can finally be let in on the secret that Latin Americans, especially their literary elite, have always known: El Señor Presidente is a canonical work, doomed to remain timely and topical until the conditions that generated it finally disappear.

0 notes

Link

Neither Gabriel García Márquez nor Mario Vargas Llosa had yet been born when the Guatemalan Miguel Ángel Asturias began to write his first novel, El Señor Presidente, in December 1922. He labored on it for a decade while living in self-imposed exile in Paris, then returned home when the Great Depression left him strapped for money, only to find that his work was unpublishable because the dictator whose reign it portrayed had given way to an even more cruel and oppressive one. When he finally self-published the novel in Mexico in 1946, it was riddled with typographical errors, and a definitive edition did not appear until 1952.

From the beginning, then, El Señor Presidente has been star-crossed. But it also ranks as one of the most important and influential works of modern Latin American literature, a kind of urtext for the celebrated generation of novelists that followed Asturias and gained global recognition in the 1960s and 1970s as members of “El Boom”: García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, Carlos Fuentes, José Donoso, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Julio Cortázar, Augusto Roa Bastos, and several others.

Even a cursory reading of David Unger’s new translation of Asturias’s novel establishes why it has had such an enormous impact. In its pages one can easily discern the origins of two phenomena that the rest of the world has come to associate with twentieth-century Latin American literature: the genre known as the dictator novel and the style called magical realism. In his introduction to Mr. President, Gerald Martin, the leading scholar of Asturias and his work in the English-speaking world, goes so far as to call it “the first page of the Boom” and claims that “it was not Gabriel García Márquez who invented magical realism; it was Miguel Ángel Asturias.” This may seem outlandish to those unfamiliar with Asturias, but it provokes very little argument in Latin America.

Mr. President takes place in an unnamed country tyrannized by an unnamed dictator, but both the place and the time are clearly implied: buried in the text are fleeting references to the quetzal, Guatemala’s national bird, and the World War I battle of Verdun. The identity of “the Constitutional President of the Republic, the Benefactor of Our Country, the Head of the Great Liberal Party, the Liberal Hearted Protector of Our Scholarly Youth” is just as readily deduced: he is modeled on Manuel Estrada Cabrera, who dominated Guatemala from 1898 to 1920 through a combination of intimidation, assassination, corruption, and fraudulent elections.

In dissecting the dictator and his despotic rule, Asturias, born the year after he took power, was writing from a privileged position. After being overthrown in 1920, following a congressional vote that deemed him mentally incompetent, Estrada Cabrera was arrested, tried, and sentenced to life in prison, where he died in 1924. Asturias took part in the popular uprising that led to his downfall and was briefly jailed; then, as a law student, he served as a secretary to the tribunal that judged Estrada Cabrera. In that position, Asturias committed to paper for the first time the horrifying stories of injustice, torture, and murder that he soon drew on for his novel; Martin says he also took a deposition from the fallen dictator in his jail cell.

In interviews near the end of his life, Asturias even credited Estrada Cabrera for his discovery of his vocation as a writer. “At 10:25 PM on 25 December 1917, an earthquake destroyed my city,” he explained in 1970.

I remember seeing something like an immense cloud covering the moon. I was in a cellar, a hole in the ground or a cave, or something like that. Right there and then I wrote my first poem, a goodbye song to Guatemala.

Later, as disaster relief from abroad poured in but went straight into the pockets of Estrada Cabrera and his cronies, “I was really angered by the circumstances under which the rubble was removed and by the social injustice that became really apparent then.” Eventually that prodded the aspiring writer into attempting a piece of narrative fiction, initially called “Political Beggars.”

The decade Asturias spent in France, after a brief and evidently unsatisfying stopover to study economics in London, radically changed the nature of the book he set out to write. He had devoted his law school thesis to “The Social Problem of the Indian,” but he began to study ethnology at the Sorbonne under the scholar Georges Raynaud, who encouraged his interest in Mayan culture and mythology; when the fruit of that academic effort, a retelling of pre-Columbian folk narratives called Legends of Guatemala, was published in French in 1931, it came with a glowing foreword by Paul Valéry.

In Paris Asturias socialized with avant-garde literary types like the poets André Breton, Tristan Tzara, César Vallejo, Louis Aragon, and Robert Desnos, and became a committed Surrealist; he also gravitated toward Picasso, whom he would recall holding court at a Montparnasse café and proclaiming, “I deform the world because I do not like it.” So instead of writing the kind of realist social novel then in vogue in Latin America, Asturias ended up creating something much more ambitious, complex, and unconventional.

The plot of Mr. President is deceptively simple, with most of the action taking place over a single week. When a half-crazed beggar accidentally kills a particularly brutal colonel in a fit of rage, the president decides to pin the blame on a general and his lawyer, whose political loyalty he has begun to doubt. This sets in motion a series of interlinked schemes and machinations that result in the imprisonment, torture, death, bondage, or general ruination of assorted government higher-ups, who suspect what is coming, and ordinary citizens, who do not. “We are a cursed country,” one prisoner laments. “Hundreds of men have had their brains blown away by murderous bullets on prison walls. The palace marbles are drenched in the blood of innocent people. Where can we look to find freedom?”

What makes Mr. President so revolutionary is the manner in which Asturias presents a story that contains many of the elements of classic Latin American melodrama, including a doomed love affair between the president’s closest adviser and the fallen general’s beautiful daughter, with “her slanted jade eyes” that “could make ships crash.” But he also repeatedly blurs or disassembles the barrier between reality and fantasy, dreams and waking, genuine and false, past and present, giving readers access to the confused perceptions, fears, and musings of a gallery of unfortunates and scoundrels.

“Half my body is a lie, the other half truth,” a songbird chirps from a pine tree during one of the beggar’s most extravagant hallucinations.

I am both rose and apple. I offer everyone a glass eye and a real eye. Those who see my glass eye see it because they dream; those who see my real eye do so because they can truly see. I am life, the Apple-Rose of the Bird of Paradise. I am the lie in every truth, the truth of all fiction.

As this passage suggests, the great insight that Asturias reached during his interlude in France—and applied to the writing of Mr. President—was that European Surrealism and Mayan mythology did not emerge from separate worlds. Rather, he said, both were generated by the unconscious and could thus be fused, “creating a mixture, and this is the magical part, that I have made use of and benefitted from in my stories.” In a collection of interviews published after his death, he expanded on that notion:

When the indigenous speak of what is unreal, such are the details of their dreams, of their hallucinations, that all of these details converge to make the dream and vision more real than reality itself. That is to say, one cannot speak of this “magical realism” without thinking of the primitive mentality of the Indian, of his manner of appraising manifestations of nature and in his profound ancestral beliefs.

Asturias originally intended to call his novel Tohil, which is the name of a powerful, demanding, and vengeful Mayan deity. In the Popol Vuh, the sacred creation narrative of the K’iche’ people, Tohil is the bringer of fire who, in return for offering warmth and sustenance, insists on absolute fealty from his grateful followers. “In truth, I am your god; so shall it be,” he tells them. “I am your lord; so shall it be.” To placate his jealous ego, he also demands human sacrifice and, when displeased, foments war. In short, Tohil is both an evocation of Estrada Cabrera and a metaphor for all the capricious dictators who have plagued Guatemala and the rest of Latin America since independence was achieved early in the nineteenth century.

In a late chapter of Mr. President entitled “Tohil’s Dance,” an obsequious poet extends that connection in a more modern direction when he proclaims, during a festive night at a bar attended by all the president’s admirers and flunkies, that the Tohil-like head of state is actually “Nietzsche’s prototype, the Superman” who “gives form to a new kind of government: the Super Democracy.” In a hilariously preposterous “Nocturne in C Major to the Super-Duperman,” an extended peroration severely curtailed in Unger’s translation, the poet explains that “Nitche” “genuinely sensed that from Father Cosmos and Mother Nature would be born in the heart of America the first Superman who has ever existed.”

Variations on this template, adapted to differing local circumstances, recur in almost every Latin American dictator novel written after Mr. President, especially those published at the peak of the Boom: Alejo Carpentier’s Reasons of State (1974), Roa Bastos’s I, the Supreme (1974), García Márquez’s The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975) and The General in His Labyrinth (1989), Luisa Valenzuela’s The Lizard’s Tail (1983), and Vargas Llosa’s The Feast of the Goat (2000), among many others. Even a late entry from a much younger, post-Boom writer, Roberto Bolaño’s Distant Star (1996), betrays the influence of Asturias, whom Bolaño once described as “a gigantic writer from a small, ill-fated country.”

Given its brilliance and influence, it continues to be a mystery why Mr. President remains less known in the English-speaking world than the many novels it inspired. One reason may be that more than fifteen years elapsed between its publication in Spanish and its appearance in English in 1963, with the same title it had in Spanish. Unger also points to deficiencies in that first translation, by the English writer Frances Marshall Partridge: “Although lyrical, it is somewhat dated, full of Anglicisms, mistranslations, occasional paragraph omissions, and an overdose of awkward Latinate constructions that may leave readers scratching their head.”

In Partridge’s defense, it should be noted that her enthusiasm for the novel was as vast as her connections to Latin America were tenuous. She is best known as part of the Bloomsbury group (having married Ralph Partridge after Dora Carrington’s ménage with him and Lytton Strachey fell apart) and is remembered mostly for her diaries and memoirs of life in that circle. As a translator, she focused on popular mainstream writers from Spain, such as the novelists Vicente Blasco Ibáñez and Mercedes Ballesteros and the philosopher José Luis López-Aranguren. With someone as inventive and innovative as Asturias, she was clearly in over her head. Whatever possessed her, for example, to translate Pelele, the nickname of the deranged beggar, as “the Zany,” when “the Dummy” would have been a much more appropriate choice?

Unger—who calls that character “the Dimwit”—is much more suited for the daunting task of taking on Asturias and his peculiar vocabulary and frequent shifts of tone. Though he writes in English, he was born in Guatemala, and his own novels, which include Life in the Damn Tropics (2002), The Price of Escape (2011), and The Mastermind (2016), often take place there. Unger has also translated the Popol Vuh and teaches at the City College of New York, including courses on translation. In 2014 he won Guatemala’s top cultural honor, the Miguel Ángel Asturias National Literature Prize, for his body of work. “As a self-proclaimed Guategringo,” he writes that “my work as a translator and fiction writer has been a lifelong attempt to return to my roots, to the land of my birth.”

Unger tells us that his translation of Mr. President aims to

establish, in the American vernacular, the proper relation among words, sentences, and paragraphs so that the author’s startling images, metaphors, and narrative verve may speak directly to the monolingual reader.

For instance, Asturias, perhaps nostalgic in exile for the comforting sensuality of daily life in the tropics, wrote especially beautiful descriptions of both rural landscapes and the sounds and smells of urban life. Unger reproduces these passages magnificently, as at the start of a chapter that portrays the capital stirring to life after a long night:

Daybreak emerged, radiating April’s freshness—outlining roofs and fields with light and bringing the darkened streets back into view. Mules carrying clanking milk cans almost galloped, urged on by the shouts and whips of muleteers. The sunlight reached the cows milked in the entryways of wealthy homeowners and on the street corners where the poor lived. The customers—either energized or about to pass out with sleepy, glassy eyes—waited for milk from their favorite cow, tilting their bottles artfully to get more liquid and less froth. Women carrying fresh bread in baskets passed by, waists twisted, legs stiff, heads sunk into their chests. Their bare feet alternated between steady and slippery steps under the weight of the baskets, piled one on top of the other like pagodas. The fragrance of sweet sesame pastries trailed them.

One of the hallmarks of the novel is the way Asturias mixes these lyrical passages with hallucinatory episodes, some of which draw on Mayan myths. Unger successfully conveys that duality too, as well as the mordantly satirical tone of a chapter called “The President’s Report,” which consists of a series of memos in which ordinary citizens inform on and denounce each other in flat bureaucratic language. Set pieces, such as a vacation trip to the beach the general’s daughter takes with her cousins and a description of a train ride through the jungle, are so vivid that they almost seem to have come from a movie projector.

But Unger has some problems with dialogue. There are passages, especially those involving the president’s henchmen, that sound like exchanges from 1930s gangster films. When a member of the secret police, for instance, disappoints one of his lowlife friends by informing him that the job he wants has gone instead to the boss’s godson, the frustrated office-seeker is told as consolation: “Listen, man, don’t be so down in the mouth over this. I’ll let you know when another cushy job opens up. I swear, on my Mother’s life, something new comes up. There are more jobs than ants in an anthill.” And when the friend remains unsatisfied, the policeman retorts: “Hey, brother, you sure are touchy.”

Also debatable is Unger’s warning that “no contemporary reader of this novel will fail to shudder when encountering slurs against Jews, Arabs, Chinese, indigenous Guatemalans, and gay and transgender people that crop up from time to time.” I confess that I did not even blink, much less shudder, when I read the passages in question, and I am a member of one of the groups being disparaged. The insults are quite tame and indirect compared to what I heard daily on the streets of Chicago growing up, and as Unger acknowledges, they were “rampant during the period Asturias is depicting.” There is really no need to apologize or offer a trigger warning: it would make no more sense to sanitize El Señor Presidente than Huckleberry Finn.

As regards the dialogue, though, the problem may simply be that Mr. President confronts any translator with impossible choices and insoluble challenges. The novel is so full of idiosyncratically Guatemalan words and expressions that even Spanish-language editions come with a glossary of dozens of terms not used elsewhere in Latin America. Additionally, Asturias was trying to capture the flavor of Spanish as it was spoken in his country more than a century ago, during his youth. Imagine, then, the added difficulty of rendering these idioms into English while preserving both tone and multiple meanings.

For example, late in the novel, the unnamed president is drunk and, after he vomits all over his closest adviser, recalls the anger and humiliation he felt as a young attorney working in a “third-rate lawyer’s office, among whores, gamblers,” and what Asturias originally called cholojeras. These are the market women, almost always indigenous, who sell cow, pig, and lamb guts for consumption in soups or the Guatemalan version of chitterlings. Partridge renders this as “offal-sellers,” while Unger prefers “shit-sellers,” although “tripe-peddlers” would be more accurate. But I remember being told by Mayan Guatemalans of my acquaintance that cholojera is also a highly pejorative and often racist term, with almost a caste connotation redolent of India. How to convey all of that in a simple one-word translation?

After Mr. President, Asturias went on to have a distinguished career, both literary and political, serving in the Guatemalan Congress and as a diplomat. In 1949 he published Men of Maize, which Martin considers “even more audacious and visionary” in its blend of Surrealism and indigenous folklore, and during a rare decade of democracy (1944–1954) he was assigned to embassies in Latin America and France. After an American-organized coup put the military back in power, though, Asturias was stripped of his citizenship and forced into exile, where he completed The Banana Trilogy, a cycle of novels about the suffering of indigenous workers on the United Fruit Company’s Guatemalan plantations. He mostly remained abroad and continued to write novels, plays, and poems until his death in Madrid in 1974. In 1967 he became the first Latin American novelist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

So in spite of Mr. President’s long and difficult road to publication, Asturias ended up achieving critical and commercial success. Yet it is never too late to burnish his reputation. As Martin maintains:

Restoring Asturias’s novel to its rightful place in Latin American cultural development and focusing its achievement are long overdue, both as an act of justice and as a contribution to historical and literary truth.

Thanks to Unger’s translation, the anglophone reader can finally be let in on the secret that Latin Americans, especially their literary elite, have always known: El Señor Presidente is a canonical work, doomed to remain timely and topical until the conditions that generated it finally disappear.

0 notes

Photo

Vento Forte

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

Global Reading Challenge: 109/200

A personal reading project, where I endeavour to read a book from each of the 193 United Nations member states plus 7 extra* ones. My main goal is to have fun and to learn, but I do have rules for myself:

The book should be fiction, and preferably a novel. I allow plays and poetry, but non-fiction only as the very last resort

The author should have the nationality of their country. If they have lived a good portion of their life there and genuinely represent the local culture, then it's ok if they've been born somewhere else

I want to read books that represent the local literary tradition. Preferably a "classic", a book that illustrates the local culture, or a book that is famous within the country. I avoid popular and contemporary fiction, and books that play outside of the country.

*Extra states have been determined based on UNESCO membership and personal interest where I want to read more books from. This is not a political statement.

The List

Afghanistan: Atiq Rahimi - Earth and Ashes

Albania:

Algeria: Albert Camus - The Stranger (FR)

Andorra: Teresa Colom - Mlle Keaton et autres creatures (FR)

Angola: José Eduardo Agualusa - The Book of Chameleons

Antigua and Barbuda

Argentina: JL Borges - Fictions

Armenia: Raffi - The Fool

Australia: Doris Pilkington/Nugi Garimara - Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence

Austria

Azerbaijan

Bahamas: Telcine Turner - Woman Take Two

Bahrain

Bangladesh

Barbados

Belarus: Uladzimir Karatkievich - King Stakh's Wild Hunt

Belgium

Belize: Zee Edgell - Beka Lamb

Benin

Bhutan

Bolivia

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Botswana: Bessie Head - Maru

Brazil: Paulo Coehlo - The Alchimist

Brunei Darussalam: K.H. Lim - Written in Black

Bulgaria: Elias Canetti - Komödie der Eitelkeit (GER)

Burkina Faso: Norbert Zongo - Le parachutage (FR)

Burundi: Samoya Kirura - La femme au regard triste (FR)

Cabo Verde: Germano Almeida - The Last Will & Testament of Senhor da Silva Araújo

Cambodia

Cameroon: Francis Bebey - King Albert

Canada: S. Alice Callahan - Wynema: A Child of the Forest

Central African Republic: Étienne Goyémidé - Le dernier Survivant de la caravane

Chad: Told by Starlight in Chad - Joseph Brahmin Seid

Chile

China

Colombia

Comoros: Ali Zamir - A Girl Called Eel

Congo

Cook Islands*: Kauraka Kauraka- Oral tradition in Manihiki

Costa Rica: Carlos Luis Fallas - Mamita Yunai (Die Grüne Hölle, GER)

Côte D’Ivoire

Croatia

Cuba

Cyprus: Kyriakos Charalambides - Selected Poems

Czech Republic: Jan Neruda - Prague Tales

DPRK (North Korea)

DRC

Denmark

Djibouti

Dominica: Jean Rhys - Wide Sargasso Sea

Dominican Republic

Ecuador

Egypt

El Salvador: Horacio Castellanos Moyà - Le bal des vipères (FR)

Equatorial Guinea: Trifonia Melibea Obono - La Bâtarde (FR)

Eritrea: Helen Berhane - Song of the Nightingale

Estonia

Eswatini: Malla Nunn - A Beautiful Place to Die

Ethiopia

Fiji: Rajni Mala Khelawan - Kalyana

Finland

France: Pierre Louys - Aphrodite: Ancient Manners

Gabon: Daniel M Mengara - Mema

Gambia

Georgia

Germany: Thomas Mann - Buddenbrooks

Ghana: Ayi Kwei Armah - The beautiful ones are not yet born

Greece

Greenland*: Knud Rasmussen - Eskimo Folktales

Grenada: Merle Collins - The Colour of Forgetting

Guatemala: Miguel Angel Asturias - Strong Wind

Guinea: Camara Laye - The Radiance of the King

Guinea Bissau: Abdulai Sila - The ultimate tragedy

Guyana Haiti

Honduras: Froylan Turcios - El Vampiro (SPA)

Hungary: Arthur Koestler - Darkness at Noon

Iceland

India: Rabindranath Tangore - The Home and the World

Indonesia

Iran: Sadegh Hedayat - The Blind Owl

Iraq: Andrew George - The epic of Gilgamesh

Ireland: James Joyce - Dubliners

Israel

Italy: Italo Calvino - If on a Winter's Night a Traveller

Jamaica: Andrew Salkey - Hurricane

Japan

Jordan: Amjad Nasser - L'ascension de l'amant (FR)

Kazakhstan

Kenya

Kiribati: Teresia Teaiwa & Vilsoni Hereniko - Last Virgin in paradise

Kosovo*

Kuwait

Kyrgyzstan: Chingiz Aitmatov - Jamila

Laos: Outhine Bounyavong - Mother's Beloved

Latvia

Lebanon

Lesotho

Liberia: Bai T. Moore - Murder in the Cassava Patch

Libya

Liechtenstein

Lithuania: Vingas Kreve - The Herdsman and the Linden Tree

Luxembourg: Norbert Jacques - Dr Mabuse der Spieler (GER)

Madagascar: Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo - Traduit de La nuit (FR)

Malawi

Malaysia

Maldives: Abdullah Sadiq - Dhon Hiyala and Ali Fulhu

Mali

Malta

Marshall Islands: Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner - Iep Jaltok: Poems from a Marshallese Daughter

Mauritania: Moussa Ould Ebnou - L'Amour Impossible (FR)

Mauritius

Mexico: Mario Bellatín - Beauty Salon

Micronesia: Emelihter Klieng - My Urohs

Monaco: Louis Notari - La légende de Sainte Dévote (FR)

Mongolia: Galsan Tschinag - Die Karawane (GER)

Montenegro: Petar II Petrovic Njegos - The Mountain Wreath

Morocco: Abdellatif Laâbi - Le bâpteme chacaliste (FR)

Mozambique

Myanmar

Namibia

Nauru: Nancy Viviani - Nauru, phosphate and political progress

Nepal

Netherlands

New Zealand: Witi Ihimaera - The Whale Rider

Nicaragua: Rubén Dario - Azul… (SPA/ENG)

Niger

Nigeria: Chinua Achebe - Things Fall Apart

Niue*: John Puhiatau Pule - The Bond of Time: An Epic Love Poem

North Macedonia

Norway: Henrik Ibsen - A Doll's House

Oman

Pakistan: Jamil Ahmad - The Wandering Falcon

Palau: Hermana Ramarui - The Palauan Perspective: a poetry book

Panama: Ricardo Miró - Las Noches de Babel (SPA)

Palestine*: Ibrahim Nasrallah - Prairies of Fever

Papua New Guinea: Vincent Eri - The Crocodile

Paraguay

Peru: Mario Vargas Llosa - In Praise of the Stepmother

Philippines

Poland

Portugal

Qatar

Republic of Korea

Republic of Moldova

Romania

Russian Federation: Leo Tolstoi - The Death of Ivan Ilyich

Rwanda

Saint Kitts and Nevis: Caryl Philips - Cambridge

Saint Lucia: Derek Walcott - Omeros

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Samoa: Albert Wendt - Leaves of the Banyan Tree

San Marino: J. Theodore Bent - A freak of Freedom: or, the Republic of San Marino

Sao Tome and Principe:

Saudi Arabia

Senegal

Serbia

Seychelles: Antoine Abel - Coco Sec (FR)

Sierra Leone

Singapore

Slovakia: Milan Rúfus - Strenges Brot

Slovenia: France Prešeren - Poems

Solomon Islands: John Saunana - Cruising Through the Reverie

Somalia: Hadraawi - The Poet and the Man

South Africa: JM Coetzee - Disgrace

South Sudan: Nyuol Lueth Tong - There is a country

Spain: Miguel de Unamuno - Abel Sanchez and Other Stories

Sri Lanka

Sudan

Suriname

Sweden: August Strindberg - The Red Room

Switzerland

Syrian Arab Republic: Ibn al-Nafis - Theologus Autodidactus

Taiwan*

Tajikistan: Shavkat Niyazi - At the Foot of Blue Mountains: Stories by Tajik Authors

Thailand

Timor-Leste: Xanana Gusmão - Mar Meu

Togo

Tonga: Epeli Hau'ofa - Tales of the Tikongs

Trinidad and Tobago

Tunisia: Albert Memmi - The Pillar of Salt

Turkey

Turkmenistan: Magtymguly - Poems from Turkmenistan

Tuvalu: Neil Lifuka - Logs in the current of the sea

Uganda: Okot p'Bitek - Song of Lawino & Song of Ocol

Ukraine: Andrey Kurkov - Death and the Penguin

United Arab Emirates

UK: Virginia Woolf - Mrs Dalloway

United Republic of Tanzania

USA: John Steinbeck - Grapes of Wrath

Uruguay

Uzbekistan: Abdullah Qoqiriy - Bygone Days

Vanuatu: Grace Molisa - Black Stone

Vatican City*: Andrew Graham-Dixon - Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel

Venezuela

Viet Nam

Yemen: Abdul-wali - They die strangers

Zambia

Zimbabwe

#booklr#currently reading#reading challenge#classic literature#literature#books#book recommendations#global reading#Sam reads#PLEASE let me know if the Read More breaks since this is a very longue post#I will link to my book reviews of the books I've read when I post them!!!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The meaning of happiness or despair can only be understood by those who have spelt it out in their minds …

Miguel Ángel Asturias El Señor Presidente (The President), 1946

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sopravvivere a tutti i mutamenti è il tuo destino.

Non v'è fretta né bisogno. Gli uomini non finiscono...

da Saggezza indigena

Miguel Angel Asturias

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Barella di foglie tinte di sangue.

(Miguel Angel, Asturias, Parma, Guanda, 1965).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mi Alma Aclama un Fuerte Abrazo | Pier Luigi Remigi

Motivacion #Pensamientos #Frases #Psicologia #Filosifia #Amor #Alma #Escritos #Poemas #Poeta #Poesia

Mi silencio se ahoga en un amargo llanto.

Mi alma aclama un fuerte abrazo.

Mis ojos piden ver unos labios.

En los cuales mis oídos puedan escuchar, lo que mi conciencia debe decirle al corazón.

poema poemas de amor poemas poemas de amor para la mujer que amo poema de salvacion poemas para el día del padre poemas de amor para el hombre que amo poemas para enamorar poemas brindis poemas de reflexion poema 20 pablo neruda poema de amor poema para el día del padre poema del pedito poema al futbol poema de amor para la mujer que amo poema de salvacion pelicula completa en español poema de barrio poema del 0 y el 1 poema del alma manolo galvan poema a la caca poema amor poema al padre paco stanley poema a la madre poema a mi padre poema a papa poema a la madre de maradonio poema amor joan manuel serrat poema a mi hermano poema a julio jaramillo de fernando artieda poema al futbol quique wolff a poema day anabantha poema 20 al otro lado del sol con poema los temerarios a temporal con joan sebastian con poema amor prohibido bryndis poema analisis metrico de un poema alex ubago poema 20 pablo neruda amo el canto del zenzontle poema en nahuatl a la madre poema familia peluche anuel poema poema brindis poema bonito poema bronco poema buenos dias amor poema bolero poema besos de gabriela mistral poema bonito de amor poema bukis poema bonito para el día del padre poema bonito para el amor de mi vida buscando cosas viejas halle un poema brindis con poema bryndis te vas con el poema busca el tesoro segun las pistas del poema brindis entre tu y yo poema bronco con poema bryndis con poema borracho de tristeza los acosta con poema brindis del bohemio poema letra brindis habia una vez una pareja con poema poema camilo sesto poema corto poema cristiano poema cero poema corto para niños poema camilo sesto no sabes cuanto te quiero poema cristiano para el día del padre poema corto para papá poema corto de amor poema cancion como hacer un poema como declamar un poema contra el dragon los acosta con poema camilo sesto poema de amor como recitar un poema correctamente coco banegas poema al vino como un poema kazu como analizar un poema con mi sangre escribire un poema la mona como leer un poema poema del padre poema de amor joan manuel serrat poema de cumpleaños poema de camilo sesto poema de salvacion pablo olivares poema de amor verdadero pure negga desiderata poema declamar un poema dice adios tu mano al viento temerarios poema don che le tengo un poema dados eternos cesar vallejo poema dimelo con poema los temerarios diferencia entre poema y poesia decir adios los acosta con poema desiderata poema original dulce poema rossy war poema en el camino aprendi poema en ingles corto y facil de pronunciar poema el seminarista de los ojos negro poema el brindis del bohemio poema es el cantar de un pajarito poema enamorado poema en paz amado nervo poema en aleman poema el cuervo edgar allan poe poema el gato el poema del diablo el poema el poema del pedito el poema y la caja siddhartha el poema de la lluvia triste el poema se acabo lo que un dia fue amor el poema de tomino el poema dela caca el poema polo urias el poema es sacar a mi primo de la carcel poema futbol poema feliz cumpleaños poema funzo poema futbol quique wolff poema feliz cumpleaños mi amor poema faraon love shady poema fast poema free fire poema feliz aniversario mi amor poema feliz dia del padre familia peluche poema ala madre funzo y baby loud el poema fernando artieda poema a julio jaramillo fondo para poema fueron tus palabras temerarios con poema faltas tu temerarios poema faraon love shady poema feliz cumpleaños poema fue en aquel cafe los acosta poema francisco canaro poema poema got talent poema guatemala de miguel angel asturias poema gabriel garcia marquez poema grupo miramar poema grupo bryndis poema got talent cesar brandon poema gracias por llegar ami vida poema gracias señor poema goblin poema gracias got talent poema 0 y 1 grupo brindis poema

#poema#poemas de amor#poemas#poemas de amor para la mujer que amo#poema de salvacion#poemas para el día del padre#poemas de amor para el hombre que amo#poemas para enamorar#poemas brindis#poemas de reflexion#poema 20 pablo neruda#poema de amor#poema para el día del padre#poema del pedito#poema al futbol#poema de amor para la mujer que amo#poema de salvacion pelicula completa en español#poema de barrio#poema del 0 y el 1#poema del alma manolo galvan

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hice un video corto uwu

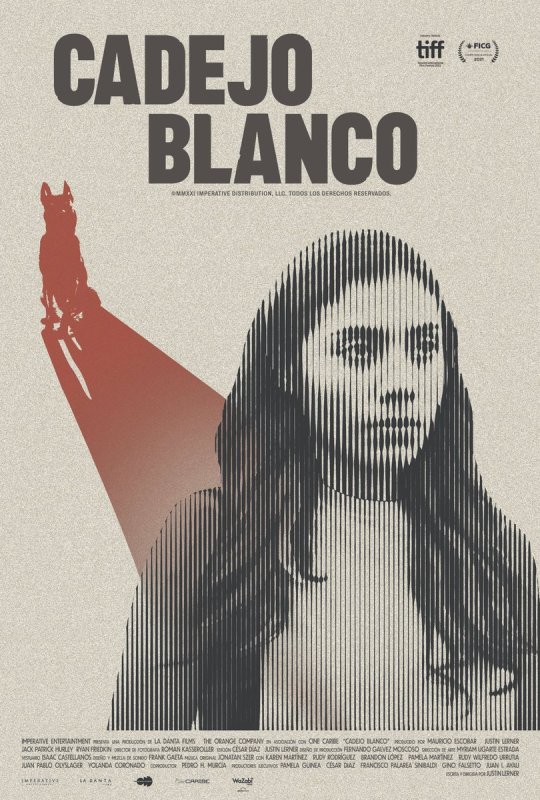

La leyenda del cadejo es una historia contada por latinoamerica (principalmente en Guatemala). Existen varias versiones de esta historia oral; pero es un hecho que el cadejo blanco es un ente que será el guardia de las personas bondadosas, mientras que el cadejo negro será la perdición de las malas.

En el video quería poner obras basadas en la leyenda, pero por cuestiones de copyright no se pudo >:I así que lo pondre a parte aquí:

En la literatura. "La leyenda del cadejo" del autor Miguel Angel Asturias.

En el cine. "Cadejo blanco" del director Justin Lerner.

En las caricaturas. En el episodio "Los cadejos" en "Víctor y Valentino" de Diego Molano.

como en los comics, como "El cadejo" del autor Juancho

se puede encontrar a esta grandiosa criatura :y

#leyenda#guatemala#latinoamerica#español#cadejo#canino#lectura#cultura#cultura pop#comic español#caricatura#stress

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photos: Civic Center of Guatemala (2023)

I wanted to take my own photographs of the Bank of Guatemala since 2018, when I quickly discovered the Guide to Modern Architecture of Guatemala City, with texts by Raúl Monterroso, Gemma Gil and photographs by Andrés Asturias. I couldn't imagine all the other buildings of heritage value that are in the surrounding area - and what better way to understand the complex designed by Jorge Montes, Roberto Aycinena, Raúl Minondo, Carlos Haeussler and Pelayo Llarena in the 50s and 60s from the top of the Miguel Angel Asturias Cultural Center.

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes