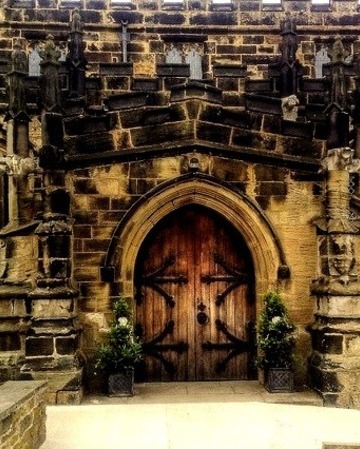

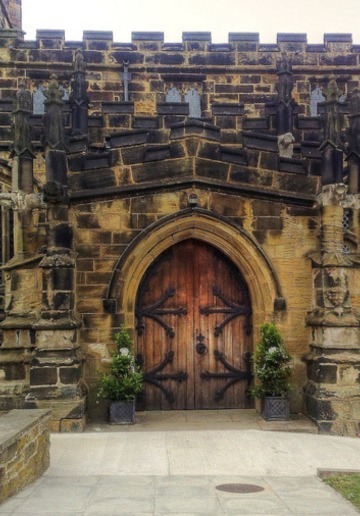

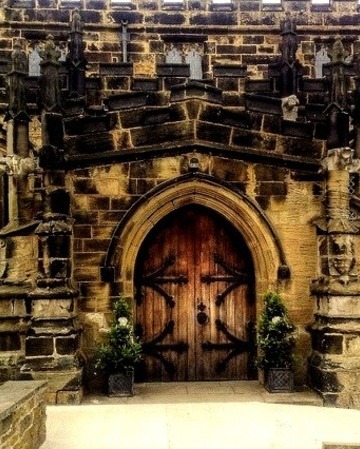

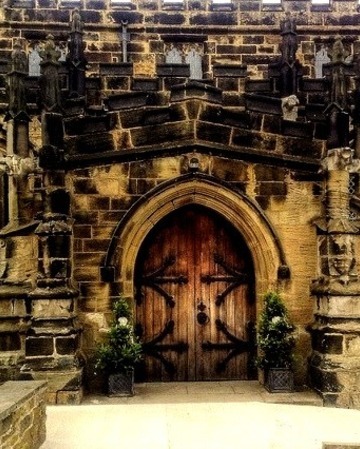

#Medieval Church Yorkshire England

Photo

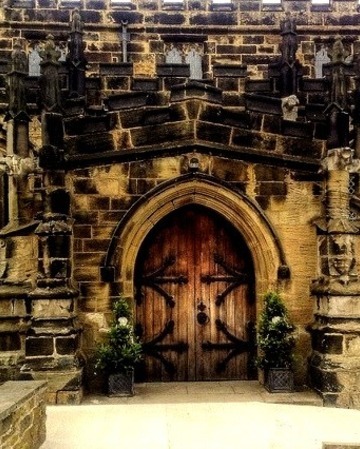

Medieval Church, Yorkshire, England

0 notes

Photo

Medieval Church, Yorkshire, England

0 notes

Text

Medieval Church, Yorkshire, England

0 notes

Text

A very private residence.

On this ancient site (York, England) traces have been found of Roman, Pagan and Christian Saxon occupation. The surviving 12th Century Norman Chapel belonged to St. Mary's Abbey throughout the middle ages.

Victims of the Black Death were buried here in 1349. Declared redundant in 1973 the building was restored as a private residence in 1981 with no public admittance allowed to the historic hall or grounds.

#Chapel#Church#Churches#Tower#Building#Structure#Architecture#History#Historic#Plague#Black Death#Dark Academia#Aesthetic#Medieval#Homes#Houses#Photography#UK#England#Yorkshire

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last year in riëvaux abbey

#rievaux abbey#old churches#old abbeys#christianity#architecture#history#heritage#Yorkshire#religon#medevil history#medevial#medieval architecture#norman conquest#Norman conquest of England#english#english heritage#English history#Normandy#selfie#couple#couple goals

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Medieval Church, Yorkshire, England

0 notes

Text

Medieval Church, Yorkshire, England

0 notes

Photo

Medieval Church, Yorkshire, England

0 notes

Photo

Medieval Church, Yorkshire, England

0 notes

Photo

Medieval Church, Yorkshire, England

0 notes

Photo

Medieval Church, Yorkshire, England

0 notes

Photo

Medieval Church, Yorkshire, England

0 notes

Photo

Medieval Church, Yorkshire, England

0 notes

Text

The Enigma of the Green Man

Symbol of life and nature:

The Celtic nature god Cernunnos from the Gundestrup Cauldron (1st Century BCE, now in the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen)

The Celtic nature god Cernunnos from the Gundestrup Cauldron (1st Century BCE, now in the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen)

The most common and perhaps obvious interpretation of the Green Man is that of a pagan nature spirit, a symbol of man’s reliance on and union with nature, a symbol of the underlying life-force, and of the renewed cycle of growth each spring. In this respect, it seems likely that he has evolved from older nature deities such as the Celtic Cernunnos and the Greek Pan and Dionysus.

Some have gone so far as to make the argument that the Green Man represents a male counterpart - or son or lover or guardian - to Gaia (or the Earth Mother, or Great Goddess), a figure which has appeared throughout history in almost all cultures. In the 16th Century Cathedral at St-Bertrand de Comminges in southern France, there is even an example of a representation of a winged Earth Mother apparently giving birth to a smiling Green Man.

Because by far the most common occurrences of the Green Man are stone and wood carvings in churches, chapels, abbeys and cathedrals in Europe (particularly in Britain and France), some have seen this as evidence of the vitality of pre-Christian traditions surviving alongside, and even within, the dominant Christian mainstream. Much has been made of the boldness with which the Green Man was exhibited in early Christian churches, often appearing over main doorways, and surprisingly often in close proximity to representations of the Christ figure.

Incorporating a Green Man into the design of a medieval church or cathedral may therefore be seen as a kind of small act of faith on the part of the carver that life and fresh crops will return to the soil each spring and that the harvest will be plentiful. Pre-Christian pagan traditions and superstitions, particularly those related to nature and trees, were still a significant influence in early medieval times, as exemplified by the planting of yew trees (a prominent pagan symbol) in churchyards, and the maintenance of ancient “sacred groves” of trees.

Tree worship goes back into the prehistory of many of the cultures that directly influenced the people of Western Europe, not least the Greco-Roman and the Celtic, which is no great surprise when one considers that much of the continent of Europe was covered with vast forests in antiquity. It is perhaps also understandable that there are concentrations of Green Men in the churches of regions where there were large stretches of relict forests in ancient times, such as in Devon and Somerset, Yorkshire and the Midlands in England. The human-like attributes of trees (trunk-body, branches-arms, twigs-fingers, sap-blood), as well as their strength, beauty and longevity, make them an obvious subject for ancient worship. The Green Man can be seen as a continuing symbol of such beliefs, in much the same way as the later May Day pageants of the Early Modern period, many of which were led by the related figure of Jack-in-the-Green.

Symbol of fertility:

Although the Green Man is most often associated with spring, May Day, etc, there are also several examples which exhibit a more autumnal cast to the figure. For example, some Green Men prominently incorporate pairs of acorns into their designs (there is a good example in King's College Chapel, Cambridge), a motif which clearly has no springtime associations. In the same way, hawthorn leaves frequently appear on English Green Men (such as the famous one at Sutton Benger), and they are often accompanied by autumn berries rather than spring flowers. The Green Man in the Chapelle de Bauffremont in Dijon (one of the few to retain its original paint coloration) shows quite clearly its leaves in their autumn colours.

This may have been simple artistic license. However, acorns, partly due to their shape, were also a common medieval fertility symbol, and hawthorn is another tree which was explicitly associated with sexuality, all of which perhaps suggests a stronger link with fertility, as well as with harvest-time.

Symbol of death and rebirth:

Green Man in the form of a skull on a gravestone in Shebbear, Devon, England (photo Simon Garbutt)

Green Man in the form of a skull on a gravestone in Shebbear, Devon, England

The disgorging Green Man, sprouting vegetation from his orifices, may also be seen as a memento mori, or a reminder of the death that await all men, as well as a Pagan representation of resurrection and rebirth, as new life naturally springs out of our human remains. The Greek and Roman god Dionysus/Bacchus, often suggested as an early precursor of the Green Man, was also associated with death and rebirth in his parallel guise as Okeanus.

Several of the ancient Celtic demigods, Bran the Blessed being one of the best known, become prophetic oracles once their heads had been cut off (another variant on the theme of death and resurrection) and, although these figures were not traditionally represented as decorated with leaves, there may be a link between them and the later stand-alone Green Man heads.

There are several examples of self-consciously skull-like Green Men, with vegetation sprouting from eye-sockets, although these are more likely to be found on tombstones than as decoration in churches (good examples can be seen at Shebbear and Black Torrington in Devon, England). Such images might be interpreted as either representing rebirth and resurrection (in that the new life is growing out of death), or they might represent death and corruption (with the leaves growing parasitically through the decaying body).

The Green Man by Talon Abraxas

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ruins of Whitby Abbey in North Yorkshire, England, completed by drone lighting.

📷 DRIFT / Cyberdrone

NOTE:

Whitby Abbey was a 7th-century Christian monastery that later became a Benedictine abbey.

The abbey church was situated overlooking the North Sea on the East Cliff above Whitby in North Yorkshire, England, a centre of the medieval Northumbrian kingdom.

The abbey and its possessions were confiscated by the crown under Henry VIII during the Dissolution of the Monasteries between 1536 and 1545.

#Whitby Abbey#North Yorkshire#England#DRIFT#Cyberdrone#drones#Henry VIII#Dissolution of the Monasteries

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

New episode, and it's our annual Halloween special! This one turned out well, I think.

----------

Happy Halloween! This season, we're covering some more spooky stories of the undead. So if you're looking to incorporate some real, historical depictions of how to deal with the undead in your next D&D game, don't delay! Learn the best kept secrets of How to Win Lawsuits against your Undead Neighbors and more in this episode.

Join our discord community! Support us on patreon! Check out our merch!

Socials: Website Twitter Instagram

Citations & References:

History of Hairshirts

Quest Friends

Poroniec

Caesarius of Heisterbach. The Dialogue On Miracles. Translated by H. von E. Scott and C. C. Swinton Bland, vol. 2. Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1929.

Grant, A. J. “Twelve Medieval Ghost Stories.” The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 363-79.

Map, Walter. De Nugis Curialium (Courtiers’ Trifles). Translated by Frederick Tupper and Marbury Bladen Ogle. Macmillan, 1924.

William of Newburgh. “The History of William of Newburgh.” The Church Historians of England, edited and translated by Joseph Stevenson, vol. 4. Seeleys, 1856.

#medieval#podcast#maniculum#medieval literature#ttrpg#medieval creatures#d&d#dnd#dungeons and dragons#medieval history#halloween#spooky season

11 notes

·

View notes