#Kongo Class

Text

Japanese Battleship Kongō (金剛, Mount Kongō) is bracketed by 1,000 lb. bombs during an air strike on the Japanese task force off Panay Island, Philippines.

Photographed on October 26, 1944.

NARA: 193802518

#Japanese Battleship Kongō#Kongō#Japanese Battleship Kongo#Kongo#Kongo Class#Japanese Battleship#Battleship#warship#ship#boat#October#1944#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#World War II#World War 2#WWII#WW2#History#WWII History#my post#Kongō Class

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

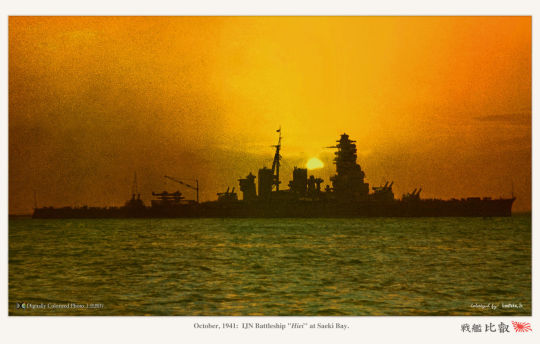

Croiseur de bataille Hiei de la Marine Impériale japonaise – Baie de Saeki – Japon – Octobre 1941

©Colorisation par...?

#WWII#Marine impériale japonaise#Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service#IJN#Marine militaire#Military navy#Navire de guerre#Warship#Croiseur de bataille#Battlecruiser#Classe Kongo#Kongo class#Hiei#Baie de Saeki#Saeki Bay#Japon#Japan#10/1941#1941

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fobos offshore naval battle opening video - Fan made Space Battleship Yamato video by Mackerel Miso EX- Kongo Class Battleship featured in this part of the video.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Japanese battleship Haruna conducting trials following her major reconstruction in 1934.

During her reconstruction, Haruna took on enough additional weaponry, armor, and other equipment that it required adding blisters to her hull (improving her stability while also increasing her protection against underwater threats). This led to an increase in her displacement by roughly 5,000 long tons. Her standard displacement grew from 27,500 long tons to 32,200 long tons. Her new full load displacement grew to roughly 36,600 long tons.

Despite the increase in tonnage and the widening of the beam from 92' (28m) to a new maximum of 101' 8" (31m), the speed of Haruna actually increased. This was due to a new powerplant, her sixteen coal-fired boilers (the result of a 1920s modernization that replaced her original thirty-six boilers) being replaced by eleven brand-new oil-fired models. This doubled her power from 64,000shp (her original output) to a new maximum of 136,000shp. The increase in power was also helped by grafting a new stern section to the hull, increasing her length by 26' (7.8m) and helping maintain her length-to-beam ratio even with the new blisters. This was enough to permit a new maximum speed of just over 30 knots.

Now, a lot of people would say this was all for naught, considering the armor was still relatively light by battleship standards. This certainly showed itself to be a problem when Kirishima was destroyed by American battleships. On the other hand, the Kongo class were far more likely to meet enemy destroyers or cruisers in combat. In this regard, the armor was sufficient.

I would go so far to say that the Kongo class were the most useful battleships in the Japanese Navy during World War 2. Their speed made them far more flexible and able to undertake a greater variety of roles.

The only major weakness of the rebuilt Kongo class was their lack of a truly modern anti-aircraft weapon system. Of course, this was a problem that affected Japan as a whole. Had the Kongo class had access to some improved anti-aircraft weapons, perhaps the 100mm heavy anti-aircraft weapons, they would have proved to be even better escorts in fleet actions.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese aircraft carrier Taiho at anchor, probably at Tawi-Tawi, Philippines. In the background are a Shokaku-class carrier and a Kongo-class battleship

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Traditional Hoodoo vs. "Marketeered" Hoodoo.

The culture and practice of Hoodoo was created by African Americans. Hoodoo includes reverence to ancestral spirits, animal sacrifice, herbal healing.

Holy Ghost shouting, praise houses, snake reverence, African American churches, Kongo cosmogram, graveyard conjure, the crossroads spirit, incorporating animal parts and the Bible is all apart of African American tradition.

During the twentieth century, white drugstore owners and mail-order companies owned by white Americans changed what African Americans created into there own version and culture of what they think is hoodoo. The hoodoo that we see practiced outside the African American community is not the hoodoo created by African Americans in the south. It is called "marketeered" hoodoo. This fake version of hoodoo is a commercialized version or tourist hoodoo.

Hoodoo was modified by whites and replaced with their practices and tools. While traditional hoodoo may not be practiced in secret. New this new hoodoo spread from southern African American community's into this product that's marketed on the internet uses.

There are a shit load of videos on the internet of people fabricating spells calling themselves Papa or root worker and others claiming to be experts on hoodoo and offering paid classes for the uneducated to writing books. As a result, people outside of the African American community think this marketeered hoodoo is authentic Hoodoo. Like the Luck Mojo company.

Now people thinks that this new Hoodoo is just spells and tricks. That Hoodoo is all about how to hex people and candle spells for love and money etc. Which is a problem. For example, High John is a black man maybe or not from Africa enslaved in the United States whose spirit resides in this practice (not the root) is how the story goes.

But It's crazy how white americans replaced root workers in African American communities, and began putting an image of a white man on their High John the Conqueror product labels. As a result, some people do not know the African American folk hero High John the Conqueror is a black man and goes as far as changing the story.

This is takes away our spiritual beliefs and makes white spiritual merchants the authority on hoodoo.

Hoodoo should be examined from the Black American experience really southern black culture, and not from the fake crap that is found in books, online and published by people don't know the culture.

Like the people who built a big business in hoodoo and learn from books by Harry Hyatt. Now I'll tell ya those book are are mostly inaccurate and not complete.

Basically it's great to see anyone from any race who want to know about this practice and this culture. But learn the right way.

#marketeered hoodoo#Commercial Hoodoo#spiritual#google search#rootwork#traditional hoodoo#southern hoodoo#like and/or reblog!#follow my blog#update post#traditional rootwork#southern rootwork#Fake hoodoo

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The only class of battlecruiser/battleship of the IJN (not counting the Yamatos) that wasn't terribly hideous and ugly. Built by the British.... probably why. The Kongo class. No awful pagoda masts!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was tagged again by @eddiemunscns

Rules: Put your repeat playlist on shuffle and list the first ten songs that pop up, then tag ten people! (I’ll get as close to ten as I can).

1. Pirate Song by Ben Barnes

2. Song About You by The Band Camino

3. First Class by Jack Harlow

4. Overboard by Stay Outside

5. Cocaine by Eric Clapton

6. 1 Last Cigarette by The Band Camino

7. Last of the Real Ones by Fall Out Boy

8. Come With Me Now by KONGOS

9. Heaven by Niall Horan

10. Let Me Down Easy by Daisy Jones & The Six

Tagging: @catgrant @acabecca @sgtbuckyybarnes @starcrossedjedis @steve--harrington--gal @far-shores @cas-verse @dragonsbone

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

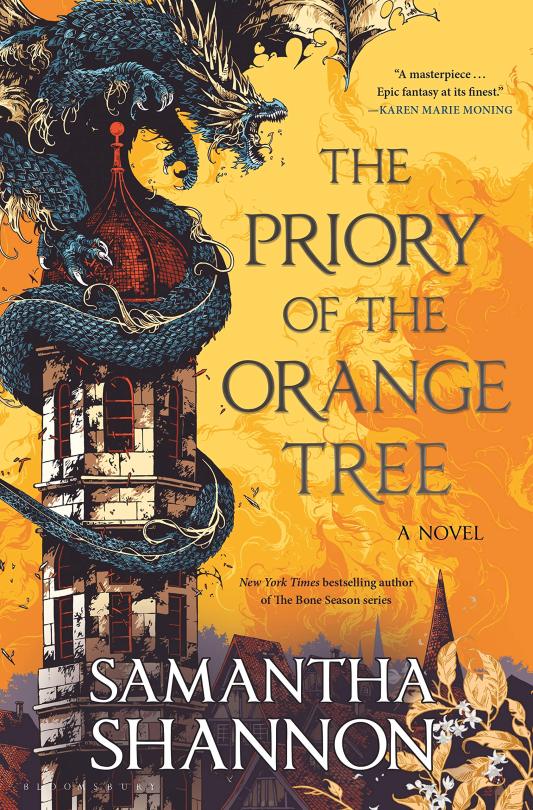

Thoughts on Priory of the Orange Tree (no big spoilers)

(so backstory is my friend is a huge SFF buff and recommended/gifted this book to me a year and a half ago (it’s gay! you like gay things!) but I’d only gotten around to reading physical books again recently, and finally dove into this one. And, when I mentioned I was reading it, a few fandom friends asked me to tell them what I thought about it. So. Here ya go.)

Over all, it's a very solid high fantasy novel and I enjoyed reading it. The story follows four protagonists as they weave paths around the known world while a humanity-threatening crisis (giant fire-breathing dragons) looms on the horizon.

Warning: I have a tendency to be like ‘I love this novel! Here are all the things wrong with it...’ so I will point out some of my gripes along with what I liked.

Worldbuilding

The worldbuilding is pretty strong, in that the author knew to highlight the portions of history she already knew well, while also doing a sufficient amount of research on areas she didn't, and moreover choosing points of view that wouldn't get into the nitty gritty in those latter cases.

It is a bit funny, though, how one of the opening pages says (direct quote), 'The fictional lands of The Priory of the Orange Tree are inspired by events and legends from various parts of the world. None is intended as a faithful representation of any one country or culture at any point in history,' and then, within three pages of the first chapter, being like 'ah yes, Edo Japan' xD

(Key going forward: Inys=England, Hróth=Scandinavia, Yscalin=Spain Mentendon=Netherlands, Lasia=Kongo (this was one I didn’t automatically know but saw while browsing the author’s tumblr), Ersyr=Persia, Seiiki=Japan, Empire of Twelve Lakes=China)

As for the magical system, I have to admit, it's a bit simplistic at core, and doesn't get delved into in a great amount of philosophical detail. It's basically just, there's earth magic (fire) and star magic (water/air), boom, that's it. What's infinitely more interesting is how the novel depicts different cultures in the world not fully understanding the entirety of the magical system and passing down myths and tales based on the fraction of it they experience, and moreover rejecting the entirety of the magical system's truth due to dogma built up over time. That's the real juicy aspect of the worldbuilding.

At core, the novel is about rejecting tribalism and breaking down such dogmas in order to work toward the survival and betterment of humanity. Imo the most interesting aspects of the novel involve characters with entrenched beliefs intersecting with characters possessing incompatible beliefs, or having their beliefs otherwise challenged.

Feminism & queer content

The feminist message in the novel is a classic sort of feminism ('a woman is more than a womb to be seeded')—all the more relevant nowadays with the current global reactionary trends regarding women's rights eh—and the setting is full of a wide variety of well rounded women in various different roles. Among them there are tenacious warriors, as well as delicate—yet equally tenacious—courtiers. Among them there are heroes, villains, and various shades in between. Women make up the prime movers and shakers of the narrative, but the narrative doesn't fall into the trap of imagining that the world would be a utopia if run by women. There is also a very nice nuanced understanding that the signifiers of liberation differ according to culture and status.

Unfortunately, there are no (visible) trans characters.

There are a couple main queer relationships in the text. The world is one in which homophobia is nonexistent, however many queer themes are still explored through the rigidity of the class structure and pressure for the nobility to bear children, causing certain relationships (including straight ones) to be forbidden. The main relationship is between a queen and her bodyguard, so, very much getting into that ‘forbidden relationship’ territory (oddly not super flavorful here tho, imo)

As someone coming from danmei/baihe fandom, I would not recommend reading this novel for the romance, because it really is quite scant, and although there are some (non explicit) sex scenes, they generally follow that adage of 'sex scenes must justify themselves by advancing the narrative'. Sometimes I felt like the writing was afraid of losing dignity if the romance portions were written with too much passion—it often felt a bit clinical. In the first sex scene I found myself focusing more on the significance of the star imagery than being titillated. But that's fine, after all it's not a romance novel, I’m just used to reading BL/GL novels.

(For those who've read priest, I would also contrast the romance here to what people often talk about in priest's works—in priest's works the plot is very heavy, but because her works are character-based, the focus always comes back to the intertwining of the plot with the main characters' relationship—there's a certain interiority to it. In Priory, we're more zoomed out, and the plot is the main focus.)

Characters & plot

My personal gripe about the romance probably comes from this (perfectly fine, honestly just a difference in style and genre) plot-over-characters design itself. The characters are generally pretty well-rounded, but they often feel more like heroes/pawns/symbols than humans. The novel is very tight, and we don't get much downtime with them, other than maybe a flashback carefully placed in an attempt to make a loss more devastating (I say 'attempt' because all in all the novel never made me cry). This is actually a novel I could see being adapted well to a live action, where the actors might add a bit more of a human touch to the characters (granted, that would be in a perfect world where live adaptations aren't beholden to generic corporate tastes haha).

On the other hand, the thing that does really make the story for me is actually the 'pawn' aspect of the characters. Although I'm not made to feel sad for the characters, I am often invested in their arcs—there are a lot of moments where the tension is slowly, slowly ramped up, and you know something bad is going to happen to them, and you're dreading it a little, but at the same time you know that this loss they're experiencing is going to take them, physically and mentally, to the place the plot will need them to be. It's those movements of the characters about the board that are truly expertly fine-tuned, and kept me wanting to read on. The plot was truly well-crafted.

Is it time to talk about individual characters? It's time to talk about individual characters. Okay, so there are four main narrators:

Ead, a Lasian-Ersyri spy sent by a secret organization of (fire)dragonslayers/mages to protect Queen Sabran of Inys. 26-yo WOC, WLW. She gets the most screen time, and she is very driven and loyal, with a broad-mindedness deepened by her experience working to blend into the Inysh court. She’s pretty OP (in a good way).

Tané, a promising Seiikinese warrior training to become a (water)dragon rider. 19-yo WOC (though given that she's a fantasy!Japanese person in fantasy!Japan, calling her a WOC could be considered projecting a western mindset on race elsewhere in the world), unknown sexuality. She is incredibly ambitious and set in her ways, partially due to having to strive to prove herself all her life, having come from a dirt-poor peasant background. She is also pretty OP (also in a good way).

Loth, an Inysh courtier plotted against to go on a suicide mission to Yscalin, which has recently been taken over by recently-awakened (fire)dragons. 30-yo MOC (in that he's described with dark skin, however he’s essentially written in a colorblind way, he's basically a fantasy!English dude whose noble family goes way back to the founding of fantasy!England, who happens to have dark skin, fwiw), unknown sexuality, but I think probably demi-heteroromantic asexual. Loth is also set in his ways in the beginning, but he is extraordinarily kind, courageous, and noble, which allows him to face new circumstances with aplomb.

Niclays, a Mentish anatomist and alchemist exiled in Seiiki. 64-yo white man, MLM. Niclays begins in a significantly different place from the other characters—he's not young or full of ambition (beyond his fruitless search for an elixir of life). He's been mourning the death of his lover and drowning in drink for many years now, and many of his decisions are clouded in a fog of misery, simply informed by what is there in front of him, if not behind—everything he does is in some way informed by the memory of his dead lover.

—Just a taste of whose eyes we get to see through. In the beginning they're strewn across the known world, but as they begin to intersect more later on in the novel, that's when we really start cooking with gas.

Some other highlights:

Inysh court politics. Look I love me some court politics where you have to keep flipping to the character guide while getting acclimated and by the end you're in it. Also I was proud of myself for being able to predict a couple things correctly (cupbearer, [redacted] ancestry). I was a little surprised that by the time the characters got to the court of the Empire of Twelve Lakes they weren't plunged into a whole other backstabby world, but I guess maybe the court politics there were all happening in the background hehe.

KALYBA. Look. Okay. We all love our milves. Our evil milves. Our evil wicked witch milves who are the terrible root of all our [redacted] trauma and turned into [redacted] because the haters wouldn't give her any oranges. Just #girlboss things right? I wanted more of her. I wanted more from her. I can't say more because spoilers. I love her.

SAMANTHA SHANNON HOW DARE YOU PUT SEQUEL BAIT AT THE END AND NO SEQUEL AGHHHHHHH anyway I hope if there is a sequel and/or prequel there will be more Kalyba/Kalyba flashbacks. And Neporo and the butterflies?? What's up with that??? Tané???? Sweet water?????

(Okay I do know that sweet water was something the pirates picked up at port, so it's not some secret thing. Must have to do with Neporo somehow, or Kalyba's backstory with Neporo) (I assume this is way too vague to count as spoilers)

Okay one spoiler, don’t look if you haven’t read the novel:

I was so sure Kalyba was planning to cozy up to the Nameless One, specifically so she could slay him with Ascalon and supplant him as the dominant dragon and become the ultimate Big Bad. I was so sure of it! I really wanted that for her!! Kalyba you deserved better!!!

#priory of the orange tree#review#samantha shannon if you see this plz know I am but a mere danmei main to whom you need not pay heed; plz don't read my silly little thoughts

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A Kongo-class battleship (possibly Kongo herself, based on the searchlight positions) illuminates the night sky from a variety of tower, stack, and mast-mounted searchlight positions in this 1930s postcard. Searchlights were crucial for fighting at night before the advent of radar, and as a result the massive lamps could also, in some cases, be director controlled to stay on target. The unfortunate drawback of searchlights was that they provided a brilliant point of aim for the opponent, and their operation - plus the flashes from gun muzzles - tended to blind the operators temporarily. Nevertheless, Japan relied heavily on them well into the 2nd World War."

Caption is exclusive to Haze Grey History Facebook page (link) and was shared with the permission of Evan Dwyer. Click this link to read more of his works. Photo is public domain.

#Kongo Class#Battleship#Searchlight#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#interwar period#Kongō Class#Dreadnought#Warship#undated#my post

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

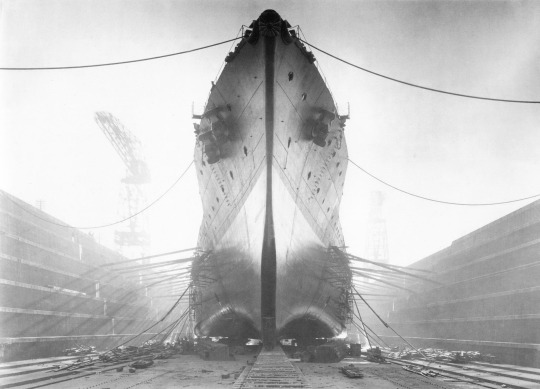

Le cuirassé Kongo de la Marine Impériale japonaise en cale sèche lors de la 1ère refonte du navire – Yokosuka – Japon – 1930

Le croiseur de bataille Kongo est entièrement refondu de septembre 1929 à mars 1931. A la sortie du chantier naval le 31 mars 1931 le navire est reclassé en cuirassé.

#WWII#avant-guerre#pre-war#marine impériale japonaise#imperial japanese navy#ijn#cuirassé#battleship#classe kongo#kongo-class#kongo#croiseur de bataille#battlecruiser#yokosuka#japon#japan#1930

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The Stage Is Set" As promised: our big post we hinted about yesterday, and it will be in two parts. 80 Years Ago - (Sunday) Nov 15th, 1942: For all the insanity happening in the Atlantic and North Africa, half a world away in the Solomon Islands, the island of Guadalcanal – and the waters around it – have become ground zero. It is the opening stage of the ground offensive to retake the Pacific, and men, supplies, planes, and ships from both sides are being hurled into it. Neither side can afford to lose it, and efforts from the Americans and the Imperial Japanese are exceeding beyond maximum. The day of the Battleship is waning, but that doesn’t mean that several dozen of these steel monsters still patrol the seas with their massive guns. Eclipsed by the aircraft carrier, the battlewagons still have plenty of life – and lethality – left in them. The Naval Battle Of Guadalcanal started on November 12th. I don’t have enough room in a hundred posts to cover it all, other than it is a wild, and horrifically savage fight that involves everything from destroyers to battleships. Both sides have been chewing away at each other for two days with no clear winner. The stage is set for one violent, brutal climax. Steaming in comes US Navy Task Force 54, with 6 ships, under Admiral Willis A. Lee. It comprises the battleships USS Washington (BB-56, North Carolina-Class, Photo 1) and USS South Dakota (BB-57, South Dakota-Class, Pic 2) and an escort of four destroyers: USS Walke, Preston, Benhim, and Gwin, respectively. Heading straight for them in the pitch dark is a Japanese task force under Admiral Nobutake Kondō. It has FOURTEEN ships: the battleship Kirishima (Kongo-Class, Photo 3), 2 heavy and 2 light cruisers and 9 destroyers. At less than 10 miles from one another, the battle opens. In short order, all four American destroyers are sunk or knocked out; Washington knocks out one Japanese destroyer. Things go right out the window when South Dakota suffers a catastrophic electric failure; she loses her radios, radar, and firing capability. Spotlighting her, the Japanese tear into South Dakota rake her with fire. Washington is now on her own. Stand by for Part 2! (at Fort Hancock, New Jersey) https://www.instagram.com/p/ClDBerItt8K/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hoodoo Heritage Month: Conjuring, Culture, And Community

Source: IMAGE COURTESY OF MADAME OMI KONGO / PINTEREST

October is Hoodoo Heritage Month! Hoodoo is an umbrella term to describe the conjuring, culture, and community of Black Americans. It’s often regarded as a Black spiritual tradition that focuses on nature and ancestral reverence.

Hoodoo Heritage Month started in 2019 when Hoodoo and Pre-Elder Mama Rueshared a post about African American spirituality on Facebook and proposed a Hoodoo Heritage Day. The Walking the Dikenga Collective extended the idea from a day to a month, and Hoodoo Heritage Month was born. What was originally a weekend event filled with teaching and classes is now a social media and community celebration of all things Hoodoo.

Hess Love, Hoodoo Historian, Archivist, and Environmental Activist says that October is the perfect month because it correlates with the thinning of the veil between our physical world and the spiritual realm. For them, Hoodoo Heritage Month is “a wonderful month of celebration, exploration, history lessons, and connections and also people learning about how pragmatic this tradition is and dynamic it is at the same time.”

If you search the hashtag #HoodooHeritageMonth on social media, you’re sure to find many resources seeking to educate Black Americans about Hoodoo. The Walking the Dikenga Collective created certain dates to commemorate the great Hoodoo ancestors:

October 2: Nat Turner Day

October 6: Fannie Lou Hamer Day

October 21: Day of our Fathers

October 23: Day of our Children

October 25: Day of our Mothers

Third Thursday: John the Conqueror Day

October 31: Crossroads Day

Mama Rue spoke with MADAMENOIRE on the importance of sharing information about these ancestors. For John the Conqueror Day, she says,

“White-washed Hoodoo doesn’t even acknowledge John the Conqueror that much because he’s been white-washed to be the type of Spirit that helps men with their virility, help men get women, help gamblers get lucky, and he’s so much more than that, and you get to learn the truth about this Spirit and what this Spirit means to us and our people.”

This white-washing has extended to other Hoodoo spirits such as the Spirit of the Crossroads. While regionally and culturally the Spirit is treated differently, mainstream media has equated this spirit to a demonic force that grants wishes in exchange for your soul, such as with Robert Johnson. The Spirit of the Crossroads is actually a spirit that operates at the crossroads between the physical and spiritual realms.

Thankfully, Mama Rue, Hess Love, and other Hoodoos are sharing the truth of our tradition with other Black folks on social media.

Around the creation of Hoodoo Heritage Month, Mama Rue felt called by her Spirits to speak out against the culture of half-truths, misconceptions, and cultural appropriation surrounding Hoodoo. She says, “Hoodoo is often seen as the bastard stepchild of the ATRs (African Traditional Religions). Folks from that lens tend to say, ‘Hoodoo is just tricks. There is no spirit involved and there’s no initiation.’”

Hoodoo Heritage Month seeks to set the record straight.

Hoodoo, as a tradition, has waxed and waned in visibility in the United States. Mama Rue explains,

“During slavery, our ancestors were not allowed to express any sort of African traditional practices. There were repercussions. Our ancestors being so clever and being the geniuses that they were figured, ‘We can still do our work and work this crossroads because we didn’t make that and they can’t punish us for walking around it, and honoring our ancestors and honoring the spirits that our ancestors revere.’ We were able to sort of sneak our practice in without anyone watching or being truly aware of what was going on.”

These practices were hidden in various parts of Black culture, including the Black church, but in recent years Black folks have been turning away from the Black church.

Mama Rue shares,

“A lot of us were leaving our churches and were talking about abuse in church. Different types: financial abuse, sexual abuse, emotional and psychological abuse.”

She claims this mass exodus left many people feeling like spiritual orphans because they had a strong spiritual need with no way to channel it outside of the church structure.

While our ancestors had to hide their African spirituality, we’ve seen a shift in the past decade. Black celebrities such as Beyoncé and Solange, writers such as Tracy Deonn and Jesmyn Ward and even the Nap Bishop herself, Tricia Hersey openly celebrate Black spirituality in their work. This artistic movement coupled with the mass exodus from the church has led to a widespread reclamation of Hoodoo.

Both Mama Rue and Hess Love say that Hoodoo, and by extension, Hoodoo Heritage Month, is for descendants of enslaved Africans in the United States and descendants of free Black people during the time of enslavement. While many Black people have stepped away from the church, Mama Rue reminds us that church-going Black folks remain one of the biggest preservers of Hoodoo and are therefore always welcomed in the tradition.

Hess goes further and tells MN,

“It’s for Black folks who live and love and want to be part of an intentional Black community and also not running away from themselves. There are some Black people who have no desire and no intention of being in community with Black people in a particular way. It’s for Black people who love other Black people. It’s for Black folks who love their ancestors. It’s for Black people who may be displaced in their community but have a type of allyship with the land and the air.”

Hoodoo Heritage Month is now a celebration of many Black people returning to the tradition of our ancestors. It’s a time for Black people to honor our ancestors, community, the environment, and ourselves.

Mama Rue says,

“It’s a time for us to get in touch with the things that our ancestors brought to this land that were broken up, fragmented, lied on, etc. It’s our way to move toward complete liberation. It’s our way of righting certain wrongs especially in the practice of ancestor reverence.”

Ancestor reverence operates on the belief that our ancestors continue to exist long after they die. As spirits, we can honor them through learning about and sharing their stories, building an altar, giving them offerings, or simply talking with them. Through this relationship, the ancestors can help improve our lives, whether that’s spiritually, emotionally, financially or however we need them to.

For Black folks who are interested in Hoodoo, Hess suggests,

“If you’re curious about something and it peaks your interest, ask why does it peak your interest? If you see a Hoodoo talking about a particular ancestor, dive deeper about that. If you see someone talking about how to use plants and herbs and you still feel called to it, if you have memories from childhood where you used to talk to trees, dive into that.”

It’s through this exploratory process that we can begin to understand the work that our ancestors are calling us to do.

During this fourth annual Hoodoo Heritage Month, Mama Rue shares,

“I am so proud of what the younger people are doing with this information. I’m so proud of the journeys that they have the courage to plant their feet on and start taking those steps and manifesting and creating the life that they want for themselves, their families, and their community.”

This Hoodoo Heritage Month, it’s important to remember that there is no right or wrong way to practice Hoodoo. While different families and regions practice differently, Hoodoo is inclusive of all of our differences. Hoodoo is in our blood. It’s how we live, and it’s a reminder that we need our ancestors, community, and the Earth to truly thrive.

RELATED CONTENT: I Followed African Spirituality for A Year, Here’s How It Changed Me

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Female monarchs and Western civilization

Nowadays, there was a heated debated on how and why the European civilization gradually surpass other civilizations and dominated the world. When we come across this question, we may find different answers. We may find out that most of the largest and strongest European empires are highly associated with the rise of several female monarchs, including Isebella of Castile, whose marriage helps the union of modern Spanish nation and memorized for her contribution to the Reconquista and the ending of Moorish regimes in Iberia Peninsula and helping Christopher Columbus’s voyage by selling off her jewelry. We may also remember also think of Elizabeth I, who pacificated time-long religion conflicts in the England Kingdom, support British navy and pirates challenging Spain’s domination on sea, and pave the way to oversea colonization of the British Empire. We may also think of Catherine the Great, during her reign, Russian empire finally defeated Ottoman empire and gains the entirely north shore of Black Sea. She also participated in the Partition of Poland, ending the centuries-long superpower in Central Europe.

Actually, contradicted to general belief, female monarchs witness more wars than their male counterparts, and their countries are mor likely to see victories in wars with foreign countries and get territory expansion. On the contrary, female monarchs are less likely to experience civil unrests. The possible reasons may lay behind:

Firstly, although compared to most of Eurasian civilizations, European civilizations have more female monarchs, the total numbers of female monarchs and their ruling length are still quite limited, only accounts to at most 15% of record history in European countries. The most outstanding female monarchs usually witness more difficulties and experience a tough time during their young age, which greatly enhance their governing skills and toughness. What is more, these successful female monarchs usually take advantage of social class conflicts to gain their throne, and thus helps them to be more willing to compromise during their governance and prevent potential internal conflicts.

Secondly, female monarchs can get more help and advice from their partner. Their marriages can help expend their own kingdoms; examples abound. The marriage between Jadwiga of Poland and Władysław II Jagiełło paved the wave of Poland-Lithuanian Commonwealth’ creation, the marriage between Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon helps the two kingdoms gradually formed the Spain Kingdom and Margaret of Denmark’s relationships helps her to united Norway, Denmark and Sweden as a whole. What is more, the husband of queen reigns can rely more on their husbands, but Kings and Emperors seldom turn to their wives for help in military and political actions. But such hypothesis has a critical issue- not all female monarchs have a descent husband. Some, like Elizabeth I have never get married, others like Catherine the Great‘s husband, former Tsar Peter I ,was very unreliable.

Although these female monarchs seldom have the awareness of gender empowerment, their undeniable contribution to history have paved the way for future female monarchs and political leaders. After the regime of Isabelle of Castile, Spain, England and Scotland witness several outstanding female monarchs, including Johanna the Madness, Mary of England, Lady Grey, Mary of Scotland and the most famous one-Elizabeth I of England. Combing with European’s contact with indigenous people in the New World and Africa, during which female monarchs in Africa and Oceania, like the queens in Kongo, Madagascar, Ethiopia, Hawaii are more willing in learning from Western civilization, Christianized and are more tough toward colonist invasions, people gradually found that women can play a equal role in political platform.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I accidentally bought two zonbis in Haiti. My zonbis are not the walking dead but rather the common, everyday spirits of the recently dead, zonbi astral. The spirits were captured from a cemetery in a mystical ritual and then contained in an empty rum bottle. I did not do the capturing and containing; this feat was achieved by a man named St. Jean, who made his living (in the face of chronically high unemployment) as a bòkò, or sorcerer, in a neighborhood near the cemetery in downtown Port-au-Prince.

I had gone to interview the bòkò, and when I complimented a colorfully decorated bottle that sat on his altar, he asked if I would like to have one like it. In agreeing, I got much more than a decorated bottle. My encounter with the sorcerer turned into something far more complex than the commission of what I took to be an art object. When I returned to pick up the bottle, St. Jean performed a complex ritual that infused human life into the bottle and transformed the container into a living grave, housing a human–spirit hybrid entity.

The essence of the zonbis’ spirit life emanates from shaved bits of bone from two human skulls. The zonbis in the bottle cannot properly be understood as souls but rather as fragments of human soul, or spirit. In Afro-Haitian religious thought, part of the spirit goes immediately to God after death, while another part lingers near the grave for a time. It is this portion of the spirit that can be captured and made to work; let’s say, a form of “raw spirit life.” The bòkò performed a spontaneous ritual, which began when he popped a cassette tape into a player.

Our soundscape was a secret society ceremony to which he said he belonged. He put these skull shavings into the bottle, along with the ashes from a burned American dollar and a variety of herbs, perfumes, alcohols, and powders. Robert Farris Thompson spelled out the logic of this sort of “charm” in his work on minkisi (containers of spirit) from the Kongo culture, which are surely one of the cultural sources of the zonbi: The nkisi is believed to live with an inner life of its own. The basis of that life was a captured soul. . . . The owner of the charm could direct the spirit in the object to accomplish mystically certain things for him, either to enhance his luck or to sharpen his business sense. This miracle was achieved through two basic classes of medicine within the charm, spirit-embedding medicine (earths, often from a grave site, for cemetery earth is considered at one with the spirit of the dead) and spirit-admonishing objects (seeds, claws, miniature knives, stones, crystals, and so forth).

In my bottle, the spirit-embedding medicine includes cemetery earth, but also more to the point, the skull shavings. At some previous time, St. Jean had most likely prepared the skulls in a sort of spirit-extracting ritual, treating them with baths of dew, rain, and sunshine. The skulls had been given food (which they absorb mystically, as spirits in the invisible world generally do) and had been baptized with new, ritual names. Their names would have been cryptic phrases, such as je m’engage (I’m trying) or al chache (go look). Each skull would have been charged with a specific strength, job, or problem to treat.

Presumably, these skulls were activated with the ability to enhance luck, wealth, and health. “Spirit-admonishing medicines” instruct the zonbis in the work that they are being commanded to do on my behalf. Ingeniously, this technology of good luck zonbi-making involves dressing the zonbis in the very instructions and work directions the maker intends them to perform. The mirrors around the center of the bottle are its “eyes for seeing” and will identify any force coming at me with malevolent intent. The scissors lashed open under the bottleneck are like arms crossed in self-defense.

The dollar bill in the bottle instructs the zonbi spirits to attract wealth. The herbs are for the zonbis to heal me of sickness and disease, while the perfumes are to make me attractive and desirable. St. Jean created for them a magnetic force field by placing two industrial magnets as a kind of collar on the neck of the bottle. This object is now swirling with polarity, intention, and life. It is what Stephan Palmié has called “a life form constituted through ritual action.”

This zonbi bottle refuses the Western ontological distinction between people and things, and between life and death, as it is a hybrid of human and spirit, living and dead, individual and generic. In Afro-Creole thought, spirit can inhabit both natural and human-made things, and what is more, this force can be manipulated and used, often for healing and protection, sometimes for aggression or attack. When I later interviewed the bòkò, I learned about the deep moral ambiguity of the zonbi astral.

St. Jean told me that the zonbis were trapped in the bottle until the time when, as with every person, their spirits would go on to God. The bòkò instructed me to ask the zonbis for anything I wanted, because, captured and ritually transformed, they were working for him, and now, as if subcontracted, for me. I realized that I was effectively in the position of a spiritual slave owner. Besides being dismayed and upset, I found it puzzling that people would practice the enslavement of this “raw spirit life” considering that their ancestors suffered extreme brutality during colonial slavery in Haiti, where the life expectancy of an enslaved person on a plantation was only seven years.

Planters fed and inaugurated the modern system of Atlantic capitalism through dehumanization, starvation, and torture; these were the routine ways of extracting production value to fund the obscenely lucrative sugar trade. But, then again, the living take charge of their history when they mimetically perform master–slave relationships with spirits of the dead. The production of spiritual (and bodily) zonbis shows us how groups remember history and enact its consequences in embodied ritual arts.

The slave trade and colonial slavery—whose modus operandus was to cast living humans as commodities—are quite literally encoded and reenacted in this living object. Just as slavery depended on capturing, containing, and forcing the labor of thousands of people, so does this form of mystical work reenact the same process in local terms. It is, as Taussig famously put it, history as sorcery. Under slavery, Afro-Caribbeans were rendered nonhuman by being legally transposed into commodities.

Now, the enslaved dead hold a respected place within the religion. In what might seem counterintuitive, Randy Matory recently argued that in Afro-Latin religions, “instead of being the opposite of the desired personal or social state, the image and mimesis of slavery become highly flexible instruments of legally free people’s aspirations for themselves and for their loved ones.” He notes that in these religions, the slave is often considered the most efficacious spiritual actor.

The relationship between spirit worker and the dead is inherently unequal and exploitative, yet it is nuanced in fascinating ways that give the spirits of the dead some agency. Usually the dealings between people and the zonbis are just that—economic affairs, caught up in a system revolving around money, work, captivity, predation, and coercion. I did feed the zonbis a ritual meal of unsalted rice and beans, feeling somewhat sheepish the entire while. But I was determined to operate in as ethical a manner as I could toward this bottle, which its maker understood to be a living thing.

Who was I not to take care of my obligations to the zonbis? I was haunted by a comment made by the scholar Luminisa Bunseki Fu-Kiau at a conference. “When you put our ‘charms’ and ‘fetishes’ in your museums,” he said, “you are incarcerating our ancestors.” I did not want to get in trouble in any way, either with the living or the dead. I had been privy to a case of sorcery involving a malevolent zonbi. I watched while Papa Mondy, an expert healer in spirit work, diagnosed a teenager who had taken sick and was acting strange.

After extensive consultation and divination, Papa Mondy informed the boy’s mother that someone with bad intentions had voye zonbi (sent a zonbi) against the teen and had “sold” the boy mystically to a secret society. The teen had been captured mystically in the unseen world, and his life force was being “eaten.” In a family drama of sickness and healing, once again the transactions of slavery were at play. This diagnosis reenacted the capture, sale, and exploitation of the life of a person, here in the unseen world of everyday Haitian life.

The cure—and the teen was cured, at least in the semipublic neighborhood narrative—involved a complex process of ritual freeing, negotiating, and buying back: an unraveling and undoing of the spiritual enslavement. The director of this healing ceremony was Papa Gede Loray, himself a spirit of a former colonial slave—considered the best “worker” among the spirits—who came to possess the priest Mondy for most of the proceedings. The teen was ritually buried, lying down (up to his neck) beneath a light layer of earth in a symbolic grave, and the zonbi was tricked and forced to remain in the grave when the boy was lifted out.

The zonbi was quickly covered up with earth then bound and tied to the spot with a rock and a rope. These Haitian spirit workers once again performed some of the actions famously used against the African enslaved— tricking, capturing, binding, and shackling—but this time the ritual actors were the present-day descendants of slaves, enacting the commodification and traffic in humans through the ritual vocabulary most salient to their history, in what Connerton called “the capacity to reproduce a certain performance.” The boy was freed of the zonbi, but he still needed to be “bought back” from the secret society.

Since it was unclear (as it often is) who sent this misfortune, the crucial redeeming deal had to be made with Bawon Samdi, the spirit-in-chief of the recently dead and the ultimate authority over the cemetery. We were going to buy the boy back from the cemetery, before the cemetery swallowed him up. We went, quite late at night by now, to an intersection of two roads where diplomatic spiritual protocol necessitated that the family make a payment to Met Kalfou, the spirit of the crossroads. Si kalfou pa bay, simitye pa pran, goes this important principle: “If the crossroads won’t give (way), the cemetery won’t take (accept).”

When we got to the cemetery, Papa Mondy set up shop next to the tomb of Bawon. An elaborate series of ritual exchanges ensued. Mondy gently ripped the boy’s clothes from his body until he wore only his underthings and then laid the boy on top of the tomb. To the accompaniment of prayers and prayer-songs, Mondy swept the boy with a broom to remove any remaining negativity. He entreated Bawon to buy back this boy from those who wanted to steal him and stood pleading with two arms outstretched while the rest of the small group sang behind him.

First he spoke to the afflicted boy, but really to us, to the dead, and to the evil-doer. “Now you are known by the cemetery. Now you are like one of the dead. How can you kill a dead man, mon cher? They can do nothing to you.” Next he addressed Bawon: “You are the one with power over death. You are the only one who can kill him,” said Mondy. “I sell this boy to you, and you alone are buying him. It is you who will determine the day he will die.” Papa Mondy knelt down and threw down a small package wrapped in brown paper, held together with pins. He deftly poured rum over the whole thing and lit a match.

A hungry blue flame engulfed the clothes, the brown paper, and the precious four hundred and twelve dollars that were inside. With this monetary sacrifice, Bawon was paid and the boy was bought. Mondy stood the boy atop the tomb and dressed him in clean white clothes. He told the boy he would no longer be under the influence of other humans or spirits who wished to harm him—only Bawon “owned” him. That night in the cemetery, the teen boy was literally, and with Haitian currency, sold to a moral and powerful guardian, in order to escape being owned by a malevolent and exploitative one.

In this case, selling a person was an act of redemption, a far cry from—and yet also an echo of—the Atlantic slave trade. One cannot help but notice the various profound ways that layers of historical events and conditions are remembered and mimetically enacted through ritual, from the slave trade to the current patronage system of politically powerful “big men” and their more vulnerable followers. This religious logic also bears a parallel to the Christian notion that Jesus pays the debt of sin for the believer, whose soul is bought and paid for through the blood of the crucifixion.

In both cases, a supernatural entity can buy the spirit (or soul) of a human and become that person’s mediator with the unseen world and the afterlife. Some Vodouists understand Jesus as the first zonbi. This myth holds that Jesus’s tomb was guarded by two Haitian soldiers, who unscrupulously stole the password God gave when He resurrected Jesus. The soldiers stole the password, sold it, and the stolen secret is now part of the secrets of sorcerers. If we examine the story carefully, we see that the buyer of people (Jesus) is victimized by people rebelling against him.

The ordinary folk—the soldiers—are stealing from God, who after all set the terms of all negotiations. In this story, the sorcerer acknowledges his opposition to (Roman Catholic) Christianity, which, in its affiliation with landowning elites, has not always served the interests of everyday Haitians. Yet insofar as being made a zonbi is a terrifying form of victimization, this story also sympathizes with Jesus. In a beautiful ironwork sculpture by Gabriel Bien-Aimé, cut and hammered from a recycled oil drum, Jesus with his crown of thorns is being taken down from the cross with a chain around his neck.

At the other end is the sorcerer controlling him. Like the colonial slave, or the oppressed worker, zonbis also possess the potential for out-and-out rebellion. There are plenty of stories of people who ask these “bought spirits” for wealth, land, or political promotion and who cannot provide the food demanded in return. Then the zonbis are said to rise up to attack their owners, consuming their life force as payment. Eating them through magic, the zonbi becomes more and more powerful as its master wastes away through sickness.

St. Jean himself was said to have been “eaten” in this manner, consumed by his own enslaved zonbi, turned cannibal in response to St. Jean’s voracious greed. Perhaps that process is what is described in this mural, painted on the interior wall of a Vodou temple. Here, a sorcerer (indicated as such by his red shirt and by the whip in his hand, a tool used to “heat up” ritual and activate spiritual energy) is attacked by hundreds of skeletal figures while facing a tomb.

Taussig, the Comaroffs, and others have written about the ways such sorcery narratives are provoked by, and are a rendering of, the basic mechanisms of capitalist production, that is, the creation of value for some through appropriating and consuming the energies of others. Haitian spirit workers have redescribed this aspect of capitalism in religious ritual.

Seen this way, zonbi-making is an example of a non-Western form of thought that diagnoses, theorizes, and responds mimetically to the long history of violently consumptive and dehumanizing capitalism in the Americas from the colonial period until the present. Zonbis can be understood as a religious, philosophical, and artistic response to the cannibalistic dynamics within capitalism and a harnessing of these principles through ritual.”

- Elizabeth McAlister, “Slaves, Cannibals, and Infected Hyper-Whites: The Race and Religion of Zombies.” in Zombie Theory: A Reader

1 note

·

View note