#Joseph Figliolia

Text

By: Joseph Figliolia

Published: Feb 1, 2024

More people are identifying as transgender and seeking medical care for gender dysphoria than ever before. Between 2018 and 2022, gender-dysphoria diagnoses increased considerably in every state in the U.S. except for South Dakota, according to Definitive Healthcare. Children’s share of dysphoria diagnoses rose from 17.5 percent to 20.4 percent in that same period. A JAMA paper noted a threefold increase in “gender-affirming” surgeries between 2016 and 2019.

The story that the “gender-affirming” camp tells itself about these developments is equal parts illuminating and frustrating. Proponents typically claim that transgender people, as we understand them today, have always existed, and that more people identify as trans because the public has become more aware and accepting of transgender identities. In other words, these activists believe that apparent increases in the trans-identifying population are not really increases at all; they merely reflect that the language, tools, and cultural climate are now in place to gauge more accurately the trans population’s size.

In a recent reported piece for The Hill, for example, Russ Toomey, a transgender professor at the University of Arizona, claimed that the alleged rise of transgender young people “is not an increase . . . we are seeing the numbers of people disclosing nonbinary and trans identity on a survey because we are asking people in more inclusive ways about their gender.” Shoshana Goldberg of the Human Rights Campaign similarly argued, “It is not that there are more people. It is that there are more people who are open and who are out. . . . The reality is that when you talk to the average person on the street, they are going to be more accepting and more affirming than they have ever been.” Of course, this observation cannot be reconciled with the pro-affirming camp’s claim that half of U.S. states are “anti-trans” and create a hostile environment for trans-identifying minors. Moreover, it seems unlikely that these explanations can solely account for the sheer size and scope of the increase in referrals over the last decade. For example, England’s Gender Identity Development Service saw a twentyfold increase in referrals for dysphoria between 2011 and 2021.

The pro-affirming side is willing to grant that social and cultural forces contribute to the documented rise in trans identification, but only in a narrow way. They allow that greater cultural visibility and acceptance leads to more people being comfortable sharing their “real” identities—but they won’t entertain the possibility that greater cultural visibility and acceptance has created cases of gender dysphoria and trans identification.

When confronted with statistical reality, this thinking yields absurd conclusions. A Williams Institute study from 2021, for example, noted the presence of 1.2 million “nonbinary” people in the United States, 75 percent of whom were below age 30. According to the pro-affirming camp, nonbinary people have always existed. But why are young people more likely than older people to adopt this identity? Why are nonbinary identities more common among girls and young women, specifically? And why didn’t this phenomenon seem to exist 30 years ago?

“You can’t identify as something if you don’t know what the word is,” counters Kay Simon, a professor who studies “queer” youth and their families. “From a very young age,” he adds, “I kind of realized I was gay . . . at the time, I probably could have told you that I felt different about my gender, but I didn’t have a word for it.”

Simon is right that discovering new terminology can sometimes help people describe elements of reality that they couldn’t previously describe. But language, and culture more broadly, can also create new social realities.

Certain material facts—our embodiment as sexed beings is one—exist independent of our cultural discourse about them. When you move beyond these natural phenomena and into the social realm, however, nature and culture can become hard to disentangle. Gender dysphoria, as a psychiatric condition, might have biological roots and in that sense be a biological phenomenon, though researchers have yet to confirm this. The idea that a person who has gender dysphoria is a different sex, however, and must be treated with hormones and surgeries is another claim altogether. It assumes that a person’s mind is the only thing that counts toward whether the individual is male or female (or something else). This is a cultural argument, not a discovery of natural fact.

Consider how our understanding of sex-reassignment surgeries has evolved. For most of the twentieth century, an adult who had surgical genital modifications would have been described as “transsexual,” not “transgender.” The popular scientific understanding of this person’s situation would be that he was suffering from a mental-health disorder and was opting to live socially as the opposite sex. Significantly, however, neither the scientific nor cultural understandings of this person’s situation would have included a metaphysical belief that the person really was the opposite sex (or another sex entirely). No shared cultural understanding existed that a male undergoing a procedure to create an artificial vagina was somehow already a female even before the procedure, though the concept of gender identity had been introduced.

In the older paradigm, the language of sex reassignment suggests that sex can be changed through surgery. Filtered through the prism of the gender-affirming paradigm, though, sex reassignment is a misnomer, since the procedure simply confirms the patient’s true “sex” as reflected by his or her gender identity. Of course, a third possibility is that it is impossible to change sex, and that these procedures are simply cosmetic.

As the philosopher Tomas Bogardus pointed out in Quillette, our language used to maintain a sex-gender distinction that acknowledged sexual dimorphism. “Sex” referred to being biologically male or female, while “gender” stood in for qualities that we associate with the sexes —like wearing makeup for girls or playing sports for boys—that are not intrinsic, definitionally, to being male or female. These gender qualities are mostly “socially constructed,” though they may be biologically predisposed. Notably, gender was also used by feminists as a synonym for sex, while gender identity was used by sexologists to refer to a person’s perception of being male or female. “Queer theorists” would later argue that the entire sex-gender distinction was artificial and that both categories were socially constructed. In this way, the terms “man” and “woman” also came to be associated with gender, suggesting that a man or woman was a social role or position that one occupied.

According to Bogardus, the flaw in what he calls the social-role view of gender is that not every person who wants to be recognized socially as a man or woman is perceived as one. To rectify this, the social-role view of gender morphed into the self-identification view. In the process, the sex-gender distinction collapsed, and the survivor was gender, not sex. In this brave new world, men who identify as women are female, and women who identify as men are male.

Gender-identity theory, then, is a strange amalgam of ideas. The theory asserts that we are imbued with an innate gendered essence, but it defines that essence by time- and culture-bound masculine and feminine stereotypes. It divorces our sex from biology, and redefines it by how we dress, behave, and express ourselves.

Even the “queer theorists,” often credited with developing gender ideology, arguably would not understand its current incarnation. For the godmother of queer theory, Judith Butler, sex is subsumed under gender, and gender exists only as a performance made intelligible through repetition. The notion that there is a “real” gender—or gender identity—behind the performance is not only false but is the very idea that queer theory aims to challenge. Those who borrow Butler’s jargon and concepts to argue that all humans have an innate gender identity, and that this innate identity needs social and medical “affirmation,” seem scarcely aware of—or concerned with—the deep contradiction in their position.

Whether social scientists admit it or not, gender discourse has consequences. As the writer and researcher Eliza Mondegreen recently pointed out, growth in trans identification is not just fueled by interpreting various kinds of distress as gender dysphoria. Trans identification can come first, followed by the experience of gender dysphoria.

Imagine a shy, sensitive boy who likes to cook and draw, and is uninterested in sports and rough-and-tumble play. In a different time, this would be unremarkable. But now, ubiquitous cultural messaging suggests that this boy’s personality and preferences are evidence that he is a girl and always has been. The boy’s self-understanding is made increasingly unstable, and his sense of self is increasingly dependent on the opinion of others. Do I sound enough like a girl? Do I look enough like one? Do others see me as the girl I know I am inside? He becomes increasingly distressed about the reality of his male body and the ever-growing chasm between it and true female embodiment. Alternatively, a part of him may understand that he is in fact male, and yet this reality is routinely denied by the gender-affirming people in his orbit. Either way, he develops gender dysphoria.

Ironically, what some activists call “gender liberation” arguably reinforces the same pressures to conform. For example, the Gender Liberation Resource Center describes liberation as “people understand[ing] themselves free of pressures to conform or limit who they can be based on their assigned sex.” “Gender liberation” in this sense may free us from the limits imposed on us by our “assigned sex,” but significantly, it imposes new limits, pressures to conform, and understandings of who we can be based on personality, preferences, and gender expression. What the activist camp fails to grasp is that in practice they encourage the same rigid adherence to social norms, and intolerance of nonconformity, that their supposedly liberatory project rejects. Where some see liberation, others see a rainbow-colored cage.

==

Regarding:

The notion that there is a “real” gender—or gender identity—behind the performance is not only false but is the very idea that queer theory aims to challenge.

This is what Judith Butler has to say:

In this sense, gender is in no way a stable identity or locus of agency from which various acts proceede; rather, it is an identity tenuously constituted in time -an identity instituted through a stylized repetition of acts. Further, gender is instituted through the stylization of the body and, hence, must be understood as the mundane way in which bodily gestures, movements, and enactments of various kinds constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self. This formulation moves the conception of gender off the ground of a substantial model of identity to one that requires a conception of a constituted social temporality. Significantly, if gender is instituted through acts which are internally discontinuous, then the appearance of substance is precisely that, a constructed identity, a performative accomplishment which the mundane social audience, including the actors themselves, come to believe and to perform in the mode of belief. If the ground of gender identity is the stylized repetition of acts through time, and not a seemingly seamless identity, then the possibilities of gender transformation are to be found in the arbitrary relation between such acts, in the possibility of a different sort of repeating, in the breaking or subversive repetition of that style.

-- Judith Butler, "Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory"

#Joseph Figliolia#gender ideology#queer theory#stereotypes#gender stereotypes#feminist theory#self ID#self identiifcation#social constructivism#religion is a mental illness

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Joseph Figliolia

Published: Dec 1, 2023

If you’ve followed the debate over treating gender-distressed youth, then you know that evidence-based policy changes, along with general public understanding, often lag the latest research. Such a gap might be less significant in other medical subfields, but it has incredibly high stakes in youth gender medicine. Given the nature of the treatments and their implications for the long-term physical and psychological well-being of underage patients, keeping up with the research is crucial—especially if the assumptions underpinning gender-dysphoria guidelines are proven false.

While the wheels of change move slowly, signs suggest that the Netherlands is beginning to grapple with the disconnect between its outdated gender-dysphoria guidelines from 2018 and new epidemiological data and other countries’ systematic reviews of evidence. While the Netherlands is only one country, it holds symbolic importance in the world of youth gender medicine. The country pioneered the use of medical interventions for gender-dysphoric youth (puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and “gender affirming” surgeries) in its original “Dutch protocol,” a document that established eligibility criteria for youth and a corresponding medical treatment pathway. Furthermore, the widespread adoption of youth gender-transition practices can be traced to the supposed success of the country’s original protocol. Dutch clinicians have also made extensive contributions to the World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s Standard of Care 8 (SOC8) as well as the Endocrine Society’s 2017 clinical-practice guidelines, which many professionals consider the definitive treatment framework for gender-distressed youth.

The Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine (SEGM) adeptly chronicles the Netherlands’s burgeoning national conversation over youth gender medicine, tracing its rise to three recent catalysts: a medical publication in a Dutch-language medical journal; a new paper in a Dutch legal journal arguing that the 2018 Dutch protocol would not hold up as a genuine “standard of care” in civil litigation; and a (liberal) Dutch public broadcaster’s release of a two-part documentary series featuring methodological experts who highlight the weaknesses of the original protocol.

The first trigger-point in the Netherlands’s trans discourse was a medical paper by researchers Jilles Smids and Patrik Vankrunkelsven. Smids and Vankrunkelsven penned the paper in response to a clinical lesson—an overview of the treatment process for trans-identifying youth, with case studies of three youth—published in the Dutch Journal of Medicine, which concedes that a surging number of patients have been referred for gender issues, that the more complex youth cases have involved adolescent-onset (rather than childhood-onset) dysphoria, and that patients often present with other psychiatric symptoms. Despite these concessions, the young people described in the clinical lesson were all ultimately treated with, or were awaiting, “gender-affirming” medical interventions. Specifically, two of the youth had gone on to take puberty blockers, while one was awaiting the start of a more targeted menarche-blocking medication.

This concession and the doctors’ treatment decisions are relevant because critics of affirmative-care practices in the Netherlands and elsewhere contend that today’s cohort of gender-distressed youth is clinically distinct from the population in the original Dutch protocol. Critics also charge that even the findings of the original Dutch studies for trans youth, which have more narrowly defined eligibility criteria (e.g., including only patients with childhood-onset dysphoria, without other psychiatric conditions, and with family support), don’t hold up under scrutiny.

In their critical paper, Smids and Vankrunkelsven take the clinical-lesson authors to task for painting an incomplete picture of the state of scientific knowledge on youth transition, and for sidestepping the international debate over what constitutes ethical care for gender-distressed youth. Smids and Vankrunkelsven seem perplexed that the clinical lesson’s authors would endorse puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones as the default treatment approach for youth when systematic reviews, including England’s NICE review, have concluded that the evidence for these interventions’ safety and effectiveness is weak. Smids and Vankrunkelsven added that if the authors used the same GRADE system used in many evidence reviews to arrive at treatment recommendations—a methodological framework for developing summaries of evidence and assessing their reliability for making clinical-practice guidelines—they would have been highly unlikely to recommend cross-sex hormones and puberty blockers as part of routine care, especially given the known cost-benefit breakdown: guaranteed fertility complications and sexual dysfunction, reductions in bone density, and possible hindrance of brain development, compared with largely inconclusive mental-health benefits and reductions in gender dysphoria.

Smids and Vankrunkelsven also criticized the clinical lesson for failing to distinguish between clinical presentations with adolescent-onset and childhood-onset dysphoria because the first group was notably not the target of the original Dutch treatment protocol, and the developmental course of this group’s dysphoria is essentially unknown. Moreover, the adolescent-onset cohort tends to have higher rates of comorbidities, which were exclusionary criteria in “the Dutch protocol.” This is crucial because trans identity and the desire for body alteration may be a maladaptive coping mechanism for underlying mental-health problems. Any clinician who would conflate these two populations is technically running a new, uncontrolled experiment.

Smids and Vankrunkelsven also noted that the true regret rate in the emergent cohort of adolescent-onset-dysphoria sufferers is unknown because some research suggests that regret can take up to eight to ten years to manifest. Yet, the clinical lesson’s authors say that 98 percent of youth who proceed from blockers to cross-sex hormones keep taking cross-sex hormones over “the long term”—quite a claim, considering that they followed up with natal males only as far out as 3.5 years, and with natal females at 2.3 years, after first intervention.

The final two concerns that Smids and Vankrunkelsven raise involve puberty blockers. First, they challenge the lesson authors’ dubious assumption that puberty blockers provide a “pause button” and are part of the diagnostic phase, rather than the first step in transitioning. Only 1.4 percent–6 percent of Dutch youth prescribed puberty blockers for gender dysphoria stopped taking them; the overwhelming majority proceeded to take cross-sex hormones. In fact, interrupting puberty might hinder natural developmental processes that could allow kids’ dysphoria to resolve itself, while taking blockers might crystallize their cross-gender identities. Smids and Vankrunkelsven’s other concern is that the clinical lesson’s authors claimed no cognitive effects of taking puberty blockers—this despite a study of individuals with precocious puberty finding an IQ reduction of seven points after they spent two years on puberty blockers.

The second catalyst for the Netherlands’s recent reconsideration came from a Dutch legal journal, Nederlands Juristenblad, which published an article by Lodewijk Smeehuijzen, Jilles Smids, and Coen Hoekstra arguing that the country’s current national guidelines for treating gender-distressed youth—again, the 2018 Dutch protocol—fail to meet the legal definition of a standard of care. The authors note that case-law precedent has established that a standard of care must be evidence-based, follow a reproducible and properly designed methodology, and have a limited “ethical dimension.” By limited “ethical dimension,” the authors mean that a standard of care’s credibility comes from its medical expertise. If guidelines are primarily mediating questions of ethics that stand outside the bounds of their medical expertise, they are less credible.

The 2018 Dutch protocol did not follow national guidelines for developing an evidence-based standard of care, and it failed to commission a systematic review of existing evidence. Moreover, as SEGM notes in its analysis, the committee overseeing the development of the 2018 Dutch protocol failed to control for conflicts of interest; Transvisie, a Dutch patient-advocacy group, took public credit for lowering the eligibility age for a mastectomy to 16 and reducing the role of psychological assessment in patients’ ability to access gender-affirming care. The 2018 protocol is not based on an assessment of the existing research and is at odds with treatment recommendations in England, Finland, and Sweden, all of which completed their own systematic reviews.

As the article highlights, other changes made to the 2018 Dutch protocol were not based on evidence. These included removing childhood-onset gender dysphoria as a key eligibility criterion for accessing care; lowering the age of eligibility for cross-sex hormones to 15 and mastectomy to 16; allowing youth with “non-binary” gender identities (identities that fall outside of the man/woman binary) to medically transition; and adopting the ICD-11 diagnostic terminology of “gender-incongruence” over gender dysphoria, which no longer requires psychological distress as a prerequisite for receiving medical care for gender issues. The 2018 Dutch protocol thus radically diverges from the guidelines of the original Dutch protocol, which imposed strict limitations on who was eligible for care.

Smeehuijzen, Smids, and Hoekstra contend that at the heart of the debate over the 2018 Dutch protocol is a fundamentally ethical, rather than medical, question: What is the proper societal response to a gender-incongruent child? Given the very weak research supporting affirming-care interventions and concerns that puberty blockers might sustain dysphoria, questions about whether it’s better to intervene early with irreversible medical procedures or allow dysphoria to resolve itself naturally, and concerns about prepubertal minors’ ability to consent, the debate over best practices is as much about ethics—and philosophical anthropology—as it is about science. For these reasons, the authors argue, the Dutch Handbook of Health Law does not grant medical guidelines special authority to resolve ethical dilemmas that fall outside of the scope of medical expertise.

The final turning point in the Dutch trans debate was the release of the new two-part Dutch-language documentary, the Transgender Protocol (Parts 1 & 2, with English subtitles), which has drawn activist groups’ ire for criticizing the affirmative-care model. Part 1 covers the scientific origins of the original Dutch protocol; Part 2 focuses primarily on the impact of puberty blockers on brain development.

Part 1 challenges the safety and efficacy of the foundational Dutch studies and interviews five Dutch experts (four research methodologists and one professor of child psychology) who criticize the existing evidence. This segment also highlights the hostile intellectual climate surrounding gender-transition procedures, which stifles scientific debate. It includes commentary from experts in other European countries and stories from those who have detransitioned.

Part 2 underscores the puberty-blocker controversy and the unsettled science about the drugs’ impact on the developing brain. According to the documentary, Dutch researchers as early as 2006 acknowledged the role that puberty, and associated hormonal changes, play in brain development. Despite this concession, the researchers never engaged in robust follow-up work to understand better the cognitive impact of halting these developmental processes, in part out of fear that unwanted findings would bring an end to puberty-blocking interventions.

While it’s far from guaranteed that Dutch officials will make changes to the 2018 protocol, the documentary has thrust the controversy into the Dutch public consciousness. Concurrent calls from the Dutch medical and legal establishments to reform existing practices to align more closely with those of other European countries is also a step in the right direction.

Given the stakes, change will arrive too late for some. But late is better than never.

#Leor Sapir#Joseph Figliolia#gender ideology#queer theory#gender affirming care#gender affirming healthcare#affirmation model#medical scandal#medical malpractice#medical corruption#medical transition#religion is a mental illness

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Leor Sapir, Joseph Figliolia

Published: Nov 8, 2023

Fenway Community Health Center in Boston, the largest provider of transgender medicine in New England and one of the leading institutions of its kind in the United States, was named a defendant in a lawsuit filed last month. The plaintiff, a gay man who goes by the alias Shape Shifter, argues that by approving him for hormones and surgeries, Fenway Health subjected him to “gay conversion” practices, in violation of his civil rights. Carlan v. Fenway Community Health Center is the first lawsuit in the United States to argue that “gender-affirming care” can be a form of anti-gay discrimination.

The case underscores an important clinical reality: gender dysphoria has multiple developmental pathways, and many who experience it will turn out to be gay. Even the Endocrine Society concedes that many of the youth who outgrow their dysphoria by adolescence later identify as gay or bisexual. Decades of research confirm as much. Gender clinicians in the U.K. used to have a “dark joke . . . that there would be no gay people left at the rate [the Gender Identity Development Service] was going,” former BBC journalist Hannah Barnes reported. Rather than help young gay people to accept their bodies and their sexuality, what if “gender-affirming” clinicians are putting them on a pathway to irreversible harm?

Due partly to Shape’s lifelong difficulty in accepting himself as gay, his lawyers are not taking the usual approach to detransition litigation. Rather than state a straightforward claim of medical malpractice or fraud, they allege that Fenway Health has violated Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which bans discrimination “on the basis of sex” in health care. In 2020, the Supreme Court ruled in Bostock v. Clayton County that “discrimination because of . . . sex” includes discrimination based on homosexuality. Citing this and other precedents, Shape’s lawyers argue that federal law affords distinct protections to gay men and lesbians—upon which clinics that operate with a transgender bias are trampling.

Shape grew up in a Muslim country in Eastern Europe that he describes in an interview as “very traditional” and “homophobic.” His parents disapproved of his effeminate demeanor and interests as a child. They wouldn’t let him play with dolls, and his mother, he says, made him do stretches so that he would grow taller and appear more masculine.

At 11, Shape had his first of several sexual encounters with older men. “I was definitely groomed,” he recounts. Shape proceeded to develop a pattern of risky sexual behavior, according to his legal complaint. He told his medical team at Fenway Health about his childhood sexual experiences, calling them “consensual.” The Fenway providers never challenged him on this interpretation, he alleges. They never suggested that he might have experienced sexual trauma or, say, explored how these events might have shaped his feelings of dissociation. (The irony is that Fenway Health describes its model of care as “trauma-informed.”)

As with the social environment they inhabited, Shape’s parents were “deeply homophobic,” he says. When Shape came out to his parents as gay at 15, they took him to a therapist, hoping that he would be “fixed.” But when he graduated high school at that same age, he moved to Bulgaria for college, and in 2007, at 17, he came to the United States for a summer program at the University of North Carolina. He later moved to Massachusetts to pursue an MBA at Clark University and immigrated to the U.S.

Though he had known about cross-dressers and transsexuals as a child (he had taken interest in Dana International, the famous Israeli transsexual who won the Eurovision Song Contest in 1998), it was only at Clark that he was introduced to the idea that some people are transgender. Other students began asking him about his pronouns and telling him about “gender identity.” After getting to know a “non-binary” person and a transgender woman, Shape started to make sense of his life retrospectively. As a boy going through puberty, he had developed larger-than-average breasts and was curvier than the other boys. It was hard for him to be accepted in the gay community, he told me, because gay men tend to value masculinity. His discomfort with social expectations about how men are supposed to look and behave, his sexual attraction to other men, his ongoing psychological and emotional distress: these were all signs, he learned from online forums, that he must have been “born in the wrong body.”

Shape quickly developed self-hatred and a strong desire to escape his body. When he started cross-dressing and presenting socially as a woman, things changed. It had been hard for him to win acceptance as an effeminate gay man, but he encountered far less hostility presenting as a woman. A subtle but important shift in his thinking took place.

“People wouldn’t take me seriously when I was a man who presented socially as a woman,” he says. “I had to actually be a woman.” Shape became immersed in online transgender culture, which told him that sex is a social construct, and that hormones and surgeries can actually turn him into a woman. As a result, Shape developed highly unrealistic expectations about what hormones and surgeries could do for him. An example noted in his legal filing: he stopped using condoms because he wanted to get pregnant.

Julie Thompson, a physician assistant and Medical Director of the Trans Health Program at Fenway Health, made no effort to perform differential diagnosis on Shape, his legal filing alleges. Shape told Thompson about his childhood sexual encounters, his troubled history of risky sexual activity, and his struggles with social and familial rejection on account of his homosexuality. Allegedly, she wrote these difficulties off as byproducts of society not accepting him as a “trans woman”—an approach known as “transgender minority stress.” Shape’s ongoing mental-health problems, it was determined, were due to “internalized transphobia.”

As Shape’s filing puts it, the Fenway clinic operated with a strong “transgender bias.” Every problem or counter-indication that came up was explained away as part of the stress that transgender people experience in an unwelcoming society. The clinicians at Fenway Health apparently assumed that sexual orientation and gender identity are two distinct and independent phenomena.

Shape was put on estrogen at age 23. According to his filing, he was not given “any explanation of the numerous potential adverse side effects of estrogen or its potentially unknown effects.” As Shape kept taking estrogen, he became even more emotional, depressed, and unstable. Notably, he did not dislike his male genitals—a fact that should have attracted more scrutiny from his clinicians—but seemed more distressed over his high sex drive and desire for intercourse with men. Though he says he frequently told his providers that he hoped “sex reassignment surgery” would reduce his sex drive, this statement did not cause them to reconsider whether estrogen was appropriate.

As the Fenway team allegedly saw it, Shape’s deterioration was evidence that he hadn’t gone far enough in his transition. They recommended that he attend First Event, a Boston-based conference held annually since 1980, where transgender people can meet one another, share ideas, interact with vendors, and find medical providers who will agree to perform procedures on them. Marci Bowers, the genital surgeon who is president of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, has attended the conference in the past. According to Shape, the point of going to First Event was to find a surgeon who would operate on him.

He did just that, and in 2014, at 24, Shape underwent facial feminization surgery and breast implantation. Less than a year later, a surgeon surgically castrated him and conducted what’s euphemistically called “bottom surgery.” It didn’t work. As a result, Shape had to undergo several additional surgeries, the last one borrowing tissue from his colon. Still, the problems persisted.

It took Shape a few years to realize that he had made a terrible mistake. The problem he had been trying to solve all his life was not “internalized transphobia” but failure to accept himself as an effeminate gay man. His legal filing states that he had what the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders called, at the time he made contact with the clinic, “ego-dystonic homosexuality.” Because they failed to detect this and other mental-health problems, the Fenway team, argue Shape’s lawyers, “outrageously, knowingly, recklessly, and callously” led him to believe that he was really a heterosexual woman whose problems could be solved by de-sexing himself as male.

Shape was promised “gender euphoria.” Instead, he told me that he now sees himself as “mutilated.” His treatments have left him with “osteoporosis and scoliosis” as well as “mental fog,” according to his legal filing. Shape is now “faced with the impossible choice of improving his cognitive state and suffering the psychological and physical effect of phantom penis, or taking estrogen and suffering mental fog and fatigue, but no phantom penis and low libido.” He has also endured fistulas as a complication of his genital surgery and “suffers from sexual dysfunction and is unable to enjoy sexual relations.” He experiences dangerous inflammation. And not getting the mental health therapy he needed very likely caused Shape’s mental health to deteriorate throughout the several years that he was a patient at Fenway Health.

Shape now wants to have his breast implants removed. But insurance does not cover the procedure because it is not technically “gender affirming.” And since he cannot afford the hefty price tag, Shape has no choice but to live with the implants.

Understandably, criticism of gender medicine has focused largely on its use in minors. Its use in adults, however, is not without controversy. In the past, when clinicians spoke of adult transgender medicine, they were referring mainly to adult men who sought to change their bodies in their forties. Many had already spent years in marriage and were fathers of children.

That is no longer the case. Though data are limited, the main patient demographic in adult transgender clinics today appear to be 18-24-year-olds. In Finland, for example, adult referrals rose approximately 750 percent between 2010 and 2018, with 70 percent of referrals being 18-22-year-olds.

Humans reach full cognitive maturity around age 25, which means that there is often little to distinguish a 20-year-old from a 17-year-old in terms of impulse control, emotional self-regulation, and the ability to set long-term goals and prioritize them over present desires. Citing “irrefutable evidence” that being under 25 means having “diminished capacity to comprehend the risk and consequences of [one’s] actions,” the progressive decarceration and racial-justice advocacy group The Sentencing Project argues that the idea that people are adults once they reach age 18 “is flawed.”

Shortly after its founding in 1971, Fenway Community Health Center was repurposed to support the unique needs of gay and lesbian residents of Boston. According to Katie Batza, a historian of the clinic, the hippies and antiwar activists who founded Fenway Health “quickly solidified its reputation as an important gay medical institution.” During the 1980s, the clinic helped tackle the AIDS epidemic. That it now maltreats gay men like Shape by converting them into trans women reflects a tectonic shift within the institution’s culture.

American medicine has always found itself balancing two competing tendencies: the paternalism of care by experts on one hand, and the relativism of nonjudgmental customer service on the other. What has happened over the course of Fenway Health’s five decades of existence is a gradual loss of that equilibrium. Fenway has long defined its mission in terms of responsiveness to the stated needs and desires of community members: the volunteers who ran the clinic and offered its services free of charge, Batza writes, “focused on providing care and building community among Fenway residents, caring less if a volunteer met outside standards of professional qualification, which were often set by the state or medical profession, that the clinic critiqued.”

In the 1990s, the clinic set up a dedicated transgender unit. At first, “things moved slowly,” recounts Marcy Gelman, a nurse practitioner who served as Fenway Health’s first dedicated provider for transgender patients, in a document published by the institute about the history of its program. She is now its associate director of clinical research. “Patients didn’t get hormones right away. We wanted to get to know them, and required them to see a therapist for several months . . . we wanted to be careful.” This process felt too restrictive for some patients, and “a few got really angry.” Fenway Health says its “commitment to ensure patient safety . . . led to some conflicts with patients and community members.”

In the 2000s, Fenway Health adopted a new model of care for its transgender-identified patients, which it called the “informed consent model.” This came in response to patients complaining about “needless gatekeeping” and concerns that the clinic’s “customer service training specific to transgender patients lagged behind the development of its clinical care.” Using funding from the Blue Cross/Blue Shield Foundation, Fenway Health made a number of new hires and expanded its program. It drew inspiration from another community health clinic, the Mazzoni Center in Philadelphia, which was smaller than Fenway but served four times as many patients. “One key to [the Mazzoni Center’s] success,” the Fenway document explains, “was the elimination of any requirement for counseling before hormones were provided.” Ruben Hopwood, a physician who joined the Fenway team in 2005, developed this model for Fenway; soon thereafter, the institution’s three-month counseling requirement gave way to “a single hormone readiness assessment visit.”

In 2012, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health published the seventh version of its Standards of Care. In the chapter on hormone therapy, WPATH recommended eligibility criteria for estrogen or testosterone, including “persistent, and well-documented gender dysphoria” and having ongoing “medical or mental health concerns . . . reasonably well-controlled.” However, WPATH also noted a newly emerging “informed consent model” and cited Fenway Health as one of three clinics that developed and practiced it.

The difference between the models, WPATH explained, was that SOC-7 put “greater emphasis on the important role that mental health professionals can play in alleviating gender dysphoria and facilitating changes in gender role and psychosocial adjustment. This may include a comprehensive mental health assessment and psychotherapy, when indicated.” By contrast, Fenway Health’s model emphasizes “obtaining informed consent as the threshold for the initiation of hormone therapy in a multidisciplinary, harm-reduction environment. Less emphasis is placed on the provision of mental-health care until the patient requests it, unless significant mental health concerns are identified that would need to be addressed before hormone prescription.” Despite the obvious differences, WPATH insisted the two models were “consistent” with each other.

Currently, Fenway Health offers hormones on the informed-consent model. “Criteria for accessing hormone therapy,” it states, “are informed by the WPATH (World Professional Association for Transgender Health) guidelines.” In other words, Fenway Health defers to WPATH, which adopted its recommendations from Fenway Health.

Shape and his lawyers deny that Fenway’s informed consent process is “a safe and effective replacement for assessment, diagnosis, and treatment provided by an appropriately trained and licensed healthcare professional.” Fenway’s model, they argue, “relies heavily on patients’ self-diagnosis, which may be a result of confusion or a misunderstanding of medically defined terms.” It does not take into account a patient’s expectations from medical treatment, which, as in Shape’s case, can be highly unrealistic. It “does not inform patients about the risk of iatrogenic effects of affirmation.” Nor does it take into account a patient’s “medical decision-making capacity,” which may be impaired in the presence of “significant emotional distress” and “undue influence from persons in position of authority and trust.”

A key charge in Shape’s lawsuit is that Fenway Health is driven by “market expansion goals and political demands of transgender activists.” Approval for hormones and surgery, the clinic’s staff wrote in 2015, should be a “routine part of primary care service delivery, not a psychological or psychiatric condition in need of treatment.” A leading advocate for the no-gatekeeping model, which rests on the assumption that mismatch between one’s actual and perceived sex is a normal human variation and not a pathological condition, argues that adults and adolescents should be free to turn their bodies into “gendered art pieces.”

From Shape’s story, we can infer that Fenway Health, which could not be reached for comment, has yielded to a barely constrained medical consumerism. In 1997, the institute had eight transgender customers. By 2015, it had over 1,700. “The rapid and sustained growth of Fenway Health’s transgender health care, research, education, training, and advocacy,” the institute’s doctors proudly declare, “might be succinctly summarized by the mantra from the movie Field of Dreams: If you build it, they will come.”

==

If you haven't met Shape Shifter, see the following interviews:

youtube

youtube

Literally "trans the gay away."

#Shape Shifter#Leor Sapir#Joseph Figliolia#Fenway Community Health Center#medical transition#gender ideology#queer theory#genderwang#medical malpractice#medical scandal#trans the gay away#trans away the gay#woke homophobia#homophobia 2.0#gay conversion therapy#conversion therapy#gender affirming care#gender affirmation#affirmation model#medical corruption#informed consent#bottom surgery#vaginoplasty#minority stress#religion is a mental illness#Youtube

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Joseph Figliolia

Published: Sep 5, 2023

In recent months, several red-state legislatures have sought to restrict gender-transition procedures for minors. Critics of these efforts often describe them as “anti-trans” or “anti-LGBTQIA+.” In a ruling striking down Florida’s prohibition against Medicaid coverage for “gender-affirming care,” U.S. district judge Robert Hinkle referred to Florida’s legislation as “purposeful discrimination against transgenders.” If language sets the terms for how the public thinks about politics, then these critics’ framings are sure to confuse.

Referring to legislation as “anti-trans” channels the language of civil rights. But while conceptualizing the gender-identity debate this way may be a powerful rhetorical strategy, it obscures the best practices for treating gender-distressed youth. Such a strategy implies that any critics of affirmative care must be motivated by prejudice against trans-identifying people, rather than by an evidence-based vision for how gender dysphoria should be conceptualized and treated.

Start with the contradictions of the pro-affirming side, where two competing visions of gender affirmation sit uneasily alongside one another. First is a medical understanding—according to which doctors are treating a diagnosable condition, gender dysphoria, which appears in multiple forms that people experience for various psychological and developmental reasons. Dysphoria can afflict people who do not identify as transgender, though gender dysphoria and transgenderism are often conflated. In this framework, affirmative care is a medical solution to a medical problem.

Second is the gender-diversity understanding, which decouples dysphoria and gender identity and maintains that all variations in gender identities are entirely natural and healthy. It also holds, crucially, that requiring a diagnosis of gender dysphoria to access affirmative medical care is a harmful form of gatekeeping, an argument advanced in the American Medical Association’s Journal of Ethics.

The gender-diversity paradigm values patient autonomy above all else. It holds that doctors are not treating a pathology as much as they are offering cosmetic procedures to help their patients become their “truest selves.” The goal is not necessarily to resolve dysphoria but to help patients achieve “gender euphoria.” On the AMA website, one physician-advocate, Aron Janssen, describes affirmative care as “patient led,” with “no single, objective outcome for somebody seeking a sense of identity.” The underlying logic of this treatment resonates with many people, intuitively aligning with America’s expressive-individualist culture.

Yet everything we know about the nature and persistence of gender dysphoria suggests that the civil rights framework is a category error. The “transgender child” exists only in relation to gender schemas that are themselves sociocultural phenomena. Gender dysphoria is real, but it is not a perfect proxy for a cross-gender identity. Moreover, gender-related distress is not one clinical entity; it can have varied presentations, etiologies, and subtypes.

To speak of “trans kids,” in other words, is to presuppose that these kids are all part of one natural category that demands one kind of treatment approach. That’s not the case. When the pro-affirming side of the debate labels kids experiencing gender dysphoria as “trans,” it conflates two categories (gender dysphoria and transgender identification) and does these young people a grave disservice.

A minor undergoing gender dysphoria will probably not identify as transgender permanently. Research shows that such symptoms follow an unpredictable developmental course. Notably, even the clinical practice guidelines for treating gender dysphoria, authored by the pro-affirming Endocrine Society, concede that most children (roughly 80 percent) who present with gender dysphoria outgrow it by adolescence, and that a considerable number of these children turn out to be gay or bisexual. Most striking of all, however, is the clear acknowledgment that no clinical assessment exists to “predict the psychosexual outcome for any specific child.” In other words, there is no reliable mechanism to determine which young people will outgrow their dysphoria and which young people will persist.

This concession exists in irreconcilable tension with, say, the activist slogan that “trans kids know who they are.” If gender dysphoria is not permanent, then what is a “trans kid?” Rather than referring to a natural category, the American Psychological Association’s page on “Understanding transgender people, gender identity and gender expression” is a classic case of concept creep. According to the APA, “transgender” is an umbrella term for “persons whose gender identity, gender expression or behavior does not conform to that typically associated with the sex to which they were assigned at birth.” Under this definition, transgender persons include those who simply express themselves, or behave, in unconventional ways for their sex. Such a definition serves to reinforce stereotypical tropes about men and women, quietly policing the boundaries of acceptable gender expression for boys and girls.

Of course, some boys have what we would consider more feminine temperaments, and some girls have what we would consider more masculine temperaments. But allegedly progressive adherents of gender ideology insist that some personalities or forms of expression are the special province of men and women, exclusively. More significantly, they claim that these gendered attributes—not our sex—define us as men and women.

In reality, assuming that “gender identity” exists at all, surely it refers to a belief about how well one’s personality, preferences, and habits conform with cultural heuristics of masculinity and femininity. If a person has internalized the rigid schemas of gender ideology, then her interpretation of where she falls along an artificial masculine–feminine gender continuum will dictate her understanding of gender. If her view of gender changes, so will her self-appraisal and resulting gender identity. Indeed, in physician-scientist Lisa Littman’s study of detransitioners, nearly two in three female detransitioners cited a “change in their personal definition of male and female” as one of their reasons for detransitioning. These young women may have felt alienated by the sex-stereotypical definitions of women that gender ideology peddles and believed that they could reconcile themselves with their bodies only by expanding their definitions of womanhood to reflect their personalities.

Not every declaration of a cross-gender identity is the result of a gender schema influencing one’s self-appraisal. But in certain sub-populations, like the identity-confused population with comorbidities described by Kaltialia-Heino or Littman’s ROGD (rapid-onset gender dysphoria) sample, it would be irresponsible not to entertain the premise. It’s also irresponsible not to mention that the rise of dysphoria diagnoses in teen girls coincides with a teen mental-health crisis that is particularly dire among girls. During these challenging developmental years, is it any surprise that gender non-conforming, psychologically vulnerable girls might feel disconnected from their sex by the onslaught of gender messaging and become dysphoric as a result? Or, alternatively, should we be shocked if they see in public messaging an explanatory framework that explains their preexisting general distress as gender dysphoria?

If psychological evaluation involves exploring the underlying dynamics behind a patient’s problem, then “gender-affirming care” is the enemy of competent evaluation. When your only interpretive tool is a gender hammer, everything looks like a gender nail.

The framing of this debate matters. Rhetorically powerful language evoking civil rights and referring to “trans kids” demagogically obscures reality. Transgenderism is a constructed category containing a heterogeneous population of dysphoric and trans-identifying people, following a unique trajectory and possessing idiosyncratic needs. Ordinary Americans must understand what is at stake in this debate. They cannot do so if journalists, judges, and politicians obscure the truth.

#Joseph Figliolia#gender ideology#queer theory#genderwang#medical malpractice#medical transition#gender dysphoria#gender distress#cosmetic surgery#stereotypes#gender stereotypes#gender identity#gender thetans#religion is a mental illness

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Joseph Figliolia

Published: Jan 11, 2024

When I learned of the controversy over Lisa Littman’s seminal paper from 2018, which introduced the concept of rapid onset gender dysphoria (ROGD), I did not understand the nature of the backlash. Littman’s paper appeared in a respected journal, Plos One, and had passed through the peer-review process. Shortly after its publication, however, the dean of public health at Brown University, where Littman, a physician, worked, published a letter noting that the Brown community was concerned that “conclusions of the study could be used to discredit the efforts to support transgender youth and invalidate perspectives of members of the transgender community.”

The letter also claimed that Littman’s research design and methods were problematic, despite her paper’s surviving an unusual post-publication assessment by senior journal editors, academic editors, a stats reviewer, and an expert reviewer. Littman claims that, after the post-publication review, her methods and findings were left virtually intact in a republished version of the paper. Most of the changes involved highlighting how her data were collected from parent reports and the limitations of those reports.

But the dean’s letter and the backlash to Littman’s paper suggest that critics’ real concern was Littman’s tentative conclusion suggesting the emergence of a novel developmental pathway to gender dysphoria. In her study, Littman hypothesized that a new form of gender dysphoria, and trans-identification, was presenting among peer groups of adolescent girls typically immersed in online trans subcultures and who often had preexisting mental-health and developmental issues. Strikingly, most of these girls had no childhood history of gender dysphoria, or even gender nonconformity, and their newly announced identities seemed unexpected and caught their parents by surprise.

Littman speculated that gender dysphoria was becoming a catch-all interpretive framework for a range of phenomena, from normal pubertal angst to specific mental-health issues. She also speculated that, among youth with existing mental-health issues or unprocessed sexual trauma, a trans identity could serve as a maladaptive coping mechanism to avoid dealing with intense negative emotions. This notion was tentatively supported by her finding that 61.4 percent of parents surveyed reported that their trans-identifying children were easily “overwhelmed by strong emotions and go to great lengths to avoid experiencing them.”

Critics realized that Littman’s hypothesis directly challenged the tenets of gender-identity theory, which hold that people have a felt sense of gender that is both innate and immutable. That theory has become a central justification for hormonal and surgical body modification. Critics alleged that Littman’s method of surveying parents was unreliable, but Littman showed that her method was consistent with other papers that support “gender affirmation” and are widely accepted by the pro-affirming side.

Fast forward six years, and Littman’s academic critics seem more committed to their intellectual and ideological priors than pursuing truth. Their main argument against ROGD is that what appears to parents as the sudden onset of transgender identity is really a late disclosure of an identity that has existed since childhood, even if the adolescent hasn’t felt comfortable revealing it to family and friends.

In a recent letter to the editor published in the Archives of Sexual Behavior, the Manhattan Institute’s Leor Sapir, along with Lisa Littman and Michael Biggs, take on the latest iteration of this argument in a paper by researcher-activist Jack Turban and his colleagues. The paper, “Age of Realization and Disclosure of Gender Identity Among Transgender Adults,” purports to show evidence of the early-realization/late-disclosure explanation for the rise in ROGD. Sapir et al.’s letter not only indicts Turban et al.’s subpar research but also, by extension, the current state of academic publishing on matters pertaining to identity (exemplified by the “ethics guidance” released by the journal Nature Human Behaviour).

Turban et al.’s argument is based on responses from the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, the largest of its kind to date, with a total of 27,715 respondents. USTS-15 asked adult participants to recall—and as critics have pointed out, recall itself is notoriously unreliable—at what age they “first felt their gender was different from their assigned birth sex” and at what age they “start to think they were trans (even if they did not know the word for it).” Turban and his coauthors took the answer to the first question rather than the second as the moment respondents first “realized they were transgender” and assessed the median time between realization and the disclosure of the identity to others. They divided participants into a “early realization” group (age ten or younger) and a “late realization” group (11 or older). Because a key premise of ROGD is that a trans identity develops rapidly within the context of adolescence, if the Turban study could show that a trans identity developed in childhood but was only disclosed later, it would undermine the ROGD hypothesis.

Yet, Turban and his colleagues seem uninterested in rigorously testing the ROGD hypothesis. Well-known for his mischaracterization of existing research, Turban made interpretive choices that strongly suggest he and his coauthors were avoiding any USTS-15 data that might undermine their broadside against ROGD.

Sapir et al.’s response is worth reading in full, but some examples of their findings should suffice here. First, to be eligible to participate in USTS-15, respondents had to identify currently as transgender. By definition, this means that anyone who identified as trans as adolescents but no longer did so as adults was excluded. Since this excluded group may include individuals whose dysphoria presentations match the ROGD phenomena, the USTS-15 sample is highly biased against ROGD hypothesis testing. Amazingly, Turban and another coauthor pointed out this limitation of the sample in a previous paper they published. Here, however, they simply ignore it.

Second, the ROGD phenomenon is hypothesized as an emergent phenomenon among a cohort of trans-identifying youth who came of age in the late 2000s or later—intersecting with widespread changes in social media, phone use, and the rise of the transgender social movement—which means that the phenomena would apply only to the 18–24 age group of the USTS-15. Despite this, Turban & colleagues analyzed the time period from realization to disclosure for the entire adult sample, and then only for those who said that they had early realization (age 10 or younger)—meaning not the cohort that would be relevant to ROGD.

Third, Turban and his coauthors chose as their proxy for age of realization a question put to participants about their age when they “felt that their gender was different than their birth sex”—instead of another question that asked them “at what age they first thought they were trans.” Asking people about their gender is more nebulous and less precise than asking them when they first thought they were trans. Not least, the problem of recall bias means that adult respondents—who, in this case, were recruited through transgender advocacy networks—could retroactively interpret reasons for “feeling different” through a gendered lens. In short, “feeling different” is a less reliable proxy for “realization” than an explicit question about the adoption of a transgender identity.

Turban et al. don’t explain this interpretive choice, but one suspects the reason: it produces a longer time from realization to disclosure. Because they take respondents’ answers about when they first “felt different” (which they code as “realized they are transgender”) at face value, they are left defending the absurd proposition that hundreds of USTS-15 respondents realized that they were transgender before their second birthday.

As Sapir’s letter notes, had the researchers analyzed data for the precise measure, they would have found that nearly 75 percent of the total sample reported late realization of a trans identity, compared with 40.8 percent originally reported. Moreover, data analyzed for the precise measure in the ROGD 18–24-year-old cohort reveals participants reported 83 percent late realization and only 17 percent early realization.

Of central importance, Turban and his coauthors claim to find that the median time from realization to disclosure was 11 years and the mode was 13 years. Had they analyzed the correct group (“late realization”), they would have found that both males and females had a mode of one year and a median of three years. In a follow-up reply to critics, Sapir and Littman point out that 2,127 respondents to the USTS-15 said that they went from “first feeling different” to disclosing a transgender identity to others in one year or less. The number of respondents who went from “first feeling they are transgender” to disclosing that identity to others within the same timeframe was 3,685. The denominator here (all 18–24-year-old respondents) was 5,880, which means that the data source Turban et al. themselves chose as reliable for testing ROGD shows that between one-third (if we’re being generous to Turban) and two-thirds (if we’re taking respondents’ report of “realizing they are transgender” at face value) meet the criteria for “rapid” development of transgender identity.

Additional features obscured in the Turban analysis also support the ROGD hypothesis. For example, ROGD is hypothesized to affect women more than men due to greater susceptibility to peer influence and because of the documented mental-health crisis among girls. While the Turban paper reports that 63.2 percent of the late-realization group was female, that percentage increases to 75.2 percent if only the relevant 18-24-year-old cohort is analyzed. Relatedly, data from the 18-24-year-old cohort also reveals that the younger cohort reported more psychological distress than older cohorts—lending more support to the ROGD hypothesis that trans-identification is a coping mechanism for preexisting psychological distress. This is consistent with research suggesting that comorbidities predate trans identification in this cohort.

Taken together, it is hard to see Turban et al.’s paper as anything but a sloppily engineered effort to discredit a hypothesis the authors disagree with for political reasons. That the Journal of Adolescent Health published their paper is yet more evidence of the ideological capture of medical journals. To add insult to injury, Sapir posted a thread on X regarding his letter to the editor and tagged the Journal of Adolescent Health, which promptly blocked him. This is behavior befitting a moody teenager, not the managers of a medical journal’s social media account.

==

Jack Turban is an activist, not a researcher, not a scientist. He just uses the language, but he doesn't even understand what "evidence-based medicine" means.

#Joseph Figliolia#ROGD#rapid onset gender dysphoria#Lisa Littman#gender ideology#queer theory#gender identity#medical corruption#ideological capture#medical fraud#trans identity#religion is a mental illness

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Joseph Figliolia

Published: Mar 1, 2024

A scan of the comments on Pamela Paul’s bombshell piece on detransitioners in the New York Times revealed that many readers were shocked at the reports of minors undergoing irreversible medical procedures for gender dysphoria without first receiving adequate psychological evaluations. They were especially horrified by the story of Kasey Emerick, whose gender distress, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation were ultimately rooted in her being sexually abused by a caregiver when she was a small child, along with internalized homophobia. While Kasey gained valuable insight into the nature of her identity struggles through the transition process, it came at the permanent cost of her breasts and the masculinizing effects of testosterone therapy.

Some readers interpreted Paul’s stories as tragic, one-off failures of oversight. But those who have studied so-called gender-affirming care know that these cases of apparent incompetence reflect built-in features of the treatment model. Gender medicine’s failures result not from a “few bad apples” but from its ideological foundations.

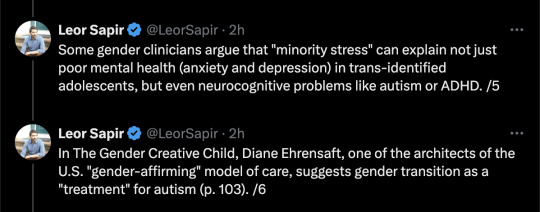

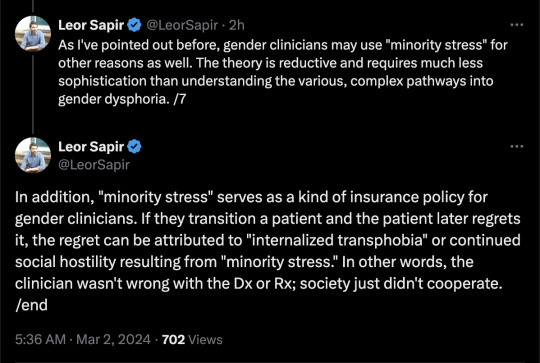

Proponents of the gender-affirmative model assume that cross-gender identities are innate, natural, and healthy. Though evidence is growing of multiple developmental pathways to gender dysphoria and trans identification, the gender-affirmative treatment model generally denies the possibility that preexisting psychological issues could contribute to dysphoria or the adoption of a trans identity. Despite the existence of a cohort of detransitioners who realize in retrospect that their trans identity was fueled by complex and untreated psychological issues, the gender-affirmative model assumes that the only reason trans-identifying people experience higher rates of mental illness is because they are a persecuted minority. Troublingly, the model also assumes that these comorbidities can be treated with medical interventions.

These claims, which constitute the crux of the “minority stress theory,” have become orthodoxy among leading gender-medical organizations and practitioners. While the World Professional Organization for Transgender Health (WPATH) recommends that clinicians conduct biopsychosocial assessments to screen for comorbidities, the organization’s own guidance assumes that psychiatric comorbidities in trans-identifying patients are often secondary to dysphoria, and attributes patients’ psychiatric issues to societal prejudice (i.e., minority stress). The chapter on adolescents in WPATH’s latest Standards of Care (SOC8), for example, suggests that elevated rates of depression, self-harm, suicidal ideation, eating disorders, and ADHD in trans-identifying populations are “often related to family/caregiver rejection, and non-affirming community environments.” Similarly, Tamara Pietztke, a whistleblower from the Mary Bridge Pediatric Gender Clinic, recalled her former supervisor’s claim that “there is not valid, evidence-based, peer-reviewed research that would indicate that gender dysphoria arises from anything other than gender (including trauma, autism, other mental health conditions, etc.).”

While the minority stress theory is widely touted by transgender activists, it has several compelling critics. Northwestern’s Michael Bailey, for example, offers a comprehensive challenge to the theory, arguing that reverse causation could be at work in the surveys that claim to document minority stress phenomena. Bailey claims that, instead of stigma and prejudice triggering psychiatric issues, people suffering from them may be more likely to report experiencing stigma and prejudice.

To explain this dynamic, Bailey draws attention to the psychological concept of “rejection sensitivity” (RS). He characterizes RS as a personality trait that emerges early in childhood and makes a person likelier to perceive others’ actions and words as “rejecting”—and to react with more distress—regardless of others’ intentions. Other researchers have found RS to be a potential risk factor for psychological issues beyond gender dysphoria.

While supporters of the minority stress theory also acknowledge the role RS might play, they often claim that it develops in early childhood after experiences of neglect or rejection from caregivers. In the case of trans-identified people, this presupposes that they were rejected as children because of their minority gender identity, which may not have emerged yet. Still, even supporters of the minority stress theory concede that having higher RS leads people to interpret certain social cues negatively.

This alternative hypothesis—that people with psychiatric issues, presumably high in rejection sensitivity, are more likely to interpret innocuous comments or remarks as being rooted in hostility and prejudice, and to report those experiences as discrimination when asked—is highly relevant, because the minority stress literature is primarily built on self-reported data. The studies in this area link mental-health issues to experiences of discrimination and prejudice by asking people whether they’ve experienced discrimination or prejudice because of their minority identity. This type of study design can’t prove that psychiatric issues are caused by stigma and prejudice and can only note associations between documented mental-health issues and self-reports of discrimination.

Another strike against the minority stress concept is implied by activists’ frequent claim that the rise in the number of trans-identifying people is the result of increased societal awareness and acceptance rather than social contagion. If we accept the claim that society is more accepting of “gender diversity,” how can we explain mental-health comorbidities that are attributed to societal prejudice? (In addition, a robust, countervailing research literature exists on psychological resilience in minority populations.)

Third, and most significantly, minority stress theory fails to explain why many studies indicate that today’s cohort of trans-identified youth often have psychiatric issues that presented before the development of a cross-gender identity. Many studies suggest that these youth have complex mental-health profiles that predate their gender dysphoria or gender-diverse identification. In Lisa Littman’s original rapid onset gender dysphoria sample, 62.5 percent of surveyed trans-identifying youth had at least one formal psychiatric diagnosis prior to the onset of their dysphoria. In Suzannah Diaz and J. Michael Bailey’s paper, 57 percent of youth had a “history of mental health issues” prior to their trans identification, while 42.5 percent had been given formal psychiatric diagnoses. A study by Tracy Becerra-Culqui and colleagues found psychiatric comorbidities present beforehand in nearly 75 percent of their sample of “transgender and gender-nonconforming” girls aged 10-17.

These studies dovetail with Littman and colleagues’ recent paper, which lends support to the notion that some portion of trans-identified youth misinterpret the symptoms of unrelated psychiatric issues as gender dysphoria. The researchers surveyed 78 detransitioners (the sample was 91 percent female) between the ages of 18 and 33 who had stopped identifying as transgender for at least the last six months. When asked to rate the importance of various psychosocial influences that could have potentially influenced their identity, participants’ highest-rated item was “interpreting feelings of trauma or a mental health condition as gender dysphoria.”

For children with gender dysphoria, surgical and hormonal treatment often don’t resolve their underlying mental-health issues. Studies suggest that patients with frequent psychiatric-care utilization pre-transition continue to have complex mental-health needs after transitioning. Finland’s Council for Choices in Health Care (COHERE) even declares that “since the reduction of psychiatric symptoms cannot be achieved with hormonal and surgical interventions, it is not a valid justification for gender reassignment.” This reality is made more troubling by new data suggesting that psychiatric issues themselves are most responsible for suicide mortality in trans populations. The authors of a new study conclude that “It is of utmost importance to identify and appropriately treat mental disorders in adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria to prevent suicide.”

Despite this plea, many youth seeking referrals to gender clinics are not properly assessed for psychiatric issues because of the ideological blinders of the affirmative model. And despite the lack of evidence that medical interventions can resolve psychiatric issues, many youth have internalized the idea that transitioning is a cure-all that can resolve their difficulties. Youth in researcher Riittakerttu Kaltiala’s clinic sample, for instance, reported high expectations that medical interventions would fix their other issues in social, academic, occupational, and mental health domains. The same was true for Littman’s ROGD sample.

Such results illustrate why the affirmative-care model is problematic. Its key assumptions—that gender identities are innate, that dysphoria has one cause and treatment pathway, and that comorbid psychiatric issues can be resolved by medical interventions—run contrary to the medical literature. Humanities departments can get away with such hyper-ideological frameworks, but they simply are not appropriate tools for the medical sciences. As Kasey Emerick knows too well, those ideologies come with a human cost that self-reported surveys cannot measure.

#Joseph Figliolia#Leor Sapir#minority stress#pseudoscience#gender identity ideology#queer theory#gender ideology#gender affirming care#gender affirming healthcare#gender affirmation#affirmation model#medical corruption#medical malpractice#medical scandal#religion is a mental illness

4 notes

·

View notes