#I was just trying to think if it's meeting the same standards as kotor

Text

Like, for all Cere saying “While you’re alive, you always have a choice” Cal doesn’t really seem to have much motivation to do all this beyond *shrug* *indistinct noise*. It’s not like the game gives him an option to go be a farmer, or something, and his goals seem pretty vague. Like, he’s going to gather potential Jedi, then ? restart the Order ?, then ??, and ???, ?????, then DEFEAT THE EMPIRE!

I know the story takes some twists and turns, found family, the journey you wanted was inside you all along, yada yada, but I wish he had something he was striving for beyond “I don’t know, didn’t have anything better to do, I guess”. Give him a separate mystery to solve, or a memory he wants to unlock, or something.

#jedi: fallen order#story criticism#it's still a likeable game#I'm not complaining about that#I was just trying to think if it's meeting the same standards as kotor#if kotor is Star Wars but an early-2000s rpg is Jedi: Fallen Order Star Wars but a late-2010s soulslike#and I don't think it quite meets that#not that kotor is perfect#it's dated#and janky#and is remembered with more heavily rose-tinted glasses than people realise#but I think it hits the feel of Star Wars the first one better than Fallen Order does#maybe because what a Star Wars movie is has changed a lot since 2003?#I think the legacy of that first movie has become a lot more muddied and dented than it used to be#in 2003 you could point to a prequel and go 'not that'#whereas now there's a lot more exhausting bullshit clumped up around Star Wars#a lot more weighty expectations#I guess the story does feel like a Star Wars knock off from the early 80s#but it does feel like a knock off#mimicking but not quite replicating#it's not a terrible thing but I would prefer some motivation#a case of more competent execution making a thing overall worse perhaps

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Natalie Jones and the Golden Ship

Part 1/? - A Meeting at the Palace

Part 2/? - Curry Talk

Part 3/? - Princess Sitamun

Part 4/? - Not At Rest

Part 5/? - Dead Men Tell no Tales

Part 6/? - Sitamun Rises Again

Part 7/? - The Curse of Madame Desrosiers

Part 8/? - Sabotage at Guedelon

Part 9/? - A Miracle

Part 10/? - Desrosiers’ Elixir

Part 11/? - Athens in October

Part 12/? - The Man in Black

Part 13/? - Mr. Neustadt

Part 14/? - The Other Side of the Story

Part 15/? - A Favour

Part 16/? - A Knock on the Window

Part 17/? - Sir Stephen and Buckeye

Part 18/? - Books of Alchemy

Part 19/? - The Answers

Part 20/? - A Gift Left Behind

Part 21/? - Santorini

Part 22/? - What the Doves Found

Part 23/? - A Thief in the Night

Part 24/? - Healing

Part 25/? - Newton’s Code

Part 26/? - Montenegro

Look who’s back!

The town of Kotor in Montenegro didn’t have many claims to fame. It had been reasonably important under the Venetian empire, but those days were long gone, and it was only just starting to find new life as a tourist attraction. In many ways it was the exact opposite of Santorini, which had been whitewashed villages clinging precariously to the edges of cliffs, with no trees. Kotor was dark stone and brick clustered at the bottom of a deep, fjord-like valley full of foliage. It was much more sheltered and cool than Santorini, and Natasha decided she would rather have spent a weekend here than on that barren volcanic island.

When they arrived, there was a cruise ship anchored in the bay.

“Wouldn’t it be funny if that were the same boat we saw at Santorini?” asked Clint.

Nat shielded her eyes from the low morning sun and squinted to see the image on the ship’s superstructure. “I think it is,” she said.

“Really?”

“Yeah.” As the sun went behind a cloud for a moment, the light changed and Nat was able to make out the circular logo. “There it is – Zodiac Cruise Lines, the Scorpio II. Same as in Santorini.”

“That’s… actually not funny at all,” Clint decided. “Think how much more fun we’d be having on our little tour of the Balkans if we were on a cruise ship!

“You’d have a way better selection of wines,” said Nat.

“Air conditioning,” Sam agreed.

“Lobsters to race,” said Jim.

“We’d have a way more expensive selection of wines,” Clint corrected. “Santorini was expensive enough. Speaking of which…” He checked his phone. “Laura says if I’m in Kotor I need to find her some smoked ham. Apparently that’s a thing.”

“All right,” said Nat. “We’ll save the world. You can shop for souvenirs.”

“I’m glad you guys trust me with the important stuff,” said Clint.

Before they did anything out, they found a room at the Hotel Vadar, just a moment’s walk from the gate in the old Venetian city walls. The hotel only had one available, due to a last-minute cancellation, and it only had one bed, but they would make do. It would definitely be better than camping out in a construction site on Santorini, or rock-hard mattresses on the creaking cargo boat.

If Neustadt had told them to go to Kotor as part of a trap, then it probably wouldn’t have mattered if they’d all stopped to take a nap first – a mousetrap wouldn’t spring until something touched the cheese. After their encounter with the thief on Santorini, however, they were worried that the alchemist might have decided to take matters into their own hands. On that assumption, they ate a quick lunch and set out for the monastery at once.

The Church and Monastery of the Holy Dove were outside the northwest corner of the town, a short but arduous hike up a very steep path on the mountainside. There were Catholic churches in Montenegro, but this one was Eastern Orthodox, identified by its domed roof and a steeple with three bells, one each for Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Square of the Holy Dove outside was thronged with tourists and with vendors selling trinkets to them. On the left side of the church steps was a man selling books of local history in several languages, and on the right were a pair of sisters busking, one with a guitar and the other singing English pop songs. Stray cats and dark-coloured pigeons ran around underfoot.

Trailing behind a tour group from the cruise ship, they climbed the steps to the church and went inside. The interior was unusually bare by Orthodox standards, which had inherited the Byzantine preference for colourful murals with lots of gold. The Holy Dove had once been decorated that way, but the plaster had fallen off the walls in an earthquake in the 1960’s, and since there was little hope of recreating the paintings in their former splendor, the walls had simply been left as bare red limestone. Only a few fragments of the paintings remained, and a corkboard displaying carefully colourized old photographs to suggest what it had once looked like. The austerity had the effect of making the wall of icons at the far end stand out all the more, their gilded surfaces glittering in the shafts of light from the high windows.

A monk was busy re-lighting candles in front of these holy pictures, murmuring a prayer as he did each one. Tourists were taking flash pictures of this, despite posted signs warning that the light might damage the remaining murals. The group respectfully waited until he was finished before approaching him.

“Excuse me,” said Nat. “Do you speak English?”

“Some,” the monk replied. “Do you have questions about the church?” He must be used to being approached by strangers.

“No,” said Natasha. “We’re here to see Brother Luka.”

The young monk went a little pale. “What do you want with Brother Luka?” he asked.

This was not going to go well, Nat could already tell. “He has something a man named Neustadt needs,” she said. “He was supposed to send it to him?”

“Wait here,” said the young monk.

He vanished through the back door of the church, leaving them to wait there a while and contemplate the crumbling paintings that remained on the insides of some of the supporting arches. These were mainly the faces of saints, with their names in Greek lettering next to them. By one was a man on a ladder, using some sort of glue to stabilize a bit that was about to fall apart.

The young monk returned, accompanied by the Abbot. This man was also younger than Nat would have pictured a monk, which she tended to think of as a bunch of old men clinging to a dying institution. He was no older than fifty, and clean-shaved, with a jowly face and a strong Eastern European nose. His expression was worried.

“Good morning,” he said to them. “I am Father Slavko of the Brothers of the Holy Dove.”

“Good morning,” Nat replied, and for the sake of looking legitimate, she pulled out her badge. “I’m Dr. Natalie Jones, of the Committee for the Appraisal of Archaeological Peril. We were told to come here and see Brother Luka. The man we spoke to didn’t give us much information.”

“You are the second group of people in as many days who have come for Brother Luka,” said the Abbot, and Nat’s heart sank – Neustadt must have already been here. “A man in a hat came yesterday morning and the two argued. The visitor left angry, and Brother Luka took ill shortly afterwards. He’s now in the hospital in Meljine. The doctors said it was a stroke.”

Something Neustadt had done on purpose, Nat wondered, or just an old man who’d gotten too angry for his own good? “What did they talk about?” she asked.

“I did not hear,” said the Abbot. “It was not my business.”

“Excuse me,” the younger monk said, “I did hear. They spoke about Aleksio the Heretic.”

Aleksio. That was the name from Newton’s notebooks, the one who said The Principle was in the monastery. “Who is Aleksio the Heretic?” she asked.

The Abbot looked over his shoulder at the crowded church and the tourists with their cameras, then moved closer to the group. “Come with me,” he said.

He led them out of the church by the back door, an ornately carved wooden one with big iron hinges that must have been centuries old, and into the area where the monks lived. Outside of the parts open to the public, the monastery was sparingly decorated and without electric lights. The Abbot stopped by a small table and took a flashlight out of a drawer, then produced an immense iron key and unlocked another door, which looked like it might lead to a medieval torture chamber – although the taller members of the CAAP had to duck to go through it, it was made of planks six inches thick, reinforced with heavy iron bands and nails like railroad spikes. When the Abbot opened the door, Nat could see that the nails were so long they went all the way through and protruded a few inches from the back, where they’d been hammered to the side to lie flat.

A very narrow flight of stone steps spiraled down into the darkness.

“Be careful,” said the Abbot. “They are often wet.”

Down they went, in single file. Sir Stephen and Sam, who were both very tall men, had to stoop. Jim bent at the knees, walking like the Missing Link, and Allen hugged his own shoulders, trying to keep from filling the entire space. Only Nat, the shortest, was able to stand up straight. Anybody wishing to go back up would probably have had to go backwards, and anybody behind him or her would have had to turn back, also.

At the bottom was an equally narrow corridor. It went a short way to another door, which the Abbot opened with a different key. The rusted hinges squealed as they moved, thunderously loud in the tiny, quiet space. Beyond was an underground chamber. A little bit of light and a slight draft came in through a set of tiny grates in the floor of the church overhead. Shadows passed by as the tourists wandered around. At the far end of the room was a table, with a little sandbox in which several candles had been set upright to burn, and an ornamental reliquary. In front of the table another monk was kneeling. He’d looked up at the sound of the hinges moving, but saw it was the Abbot, and returned to his silent praying.

“Have you heard of the Cathars?” asked the Abbot.

“They were a heretical group during the Middle Ages,” Natasha replied. “They believed that God and the Devil were equal in power, and the Earth was their battleground. Was Aleksio the Heretic a Cathar?”

“No,” said the Abbot. “His was a much more poisonous idea. He believed that the Devil could not truly be evil, because all the evil he does is in the service of God’s plan. He reasoned that evil would not exist unless God allowed it, and therefore evil can serve good purposes – he thought that Judas would go to Heaven for making Christ’s sacrifice possible, and that the Anti-Christ would be as divine as Christ himself.”

Nat had been hoping for something a little more alchemical. As far as she could tell, this was just theological semantics, and seemed irrelevant. “Neustadt said he had something called the Principle.”

The Abbot nodded. “That is in here. It’s our most holy relic.”

“So why is it hidden away, and not in a place where souls may benefit by it?” asked Sir Stephen.

“For a long time it was because of the Crusaders,” the Abbot said. “It was the sort of treasure they would stop at nothing to possess, and so we pretended it was only a myth. After centuries of that it was almost forgotten. Then we had to hide it away from the heathen Turks, who would have destroyed it if they’d found it – and then there was Aleksio, who said that the Antichrist would come for it on the day of judgment.” He looked up at the ceiling as another tourist’s shadow passed over it. “And don’t think I haven’t wondered if the man in the hat were he.”

“He’s not the Antichrist, he’s an alchemist,” said Natasha. Although she supposed it was possible that Aleksio had thought Newton was the Antichrist… in which case, in a mind that believed everything served God’s plan, Newton might actually be the good guy. “Is it gold?”

“No,” said the Abbot. “It is something infinitely more valuable than that.”

He touched the praying monk’s shoulder, and the man got up and stood aside. The Abbot took a chain from around his own neck and removed a small, tarnished key from it, and unlocked the reliquary on the table.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the things I think gamers haven’t adapted to is the patch system as it exists now.

Look, I’m never going to go all onboard the ‘since they’re gonna patch things anyway, no need to hold companies to standards on these things’ or anything like that, but... We’re at a point where these games are massive. Where there are enough places for things to go wrong that they can be fixing things still at the moment of release.

And like... Maybe my view is just colored by the fact that I lived through the debacle that was KOTOR 2, where Lucasfilm pushed that game out the door ahead of schedule and refused to let Obsidian release the patch they wanted, and feel that publishers do deserve a little leeway on the bugs and glitches that make it through the final process.

Like, with Andromeda, people are still using footage from the release to condemn it, citing bugs and glitches - not the game breaking ones, just the animations, the “my face is tired” bit, which was changed after the fifth patch - as the reason it failed. And, okay, I concede that it’s the kind of word of mouth in the early days that can affect the game, but THEY DID FIX IT. Maybe not instantly, but they addressed it. They did something about it.

I will be irritated about bugs at launch, but actively trying to do something - anything - about them goes a long way with me, because I know I couldn’t replicate even a fraction of these games on my own, so these games are surely not easy to make. Things slipping through the cracks are pretty much expected. We may be used to more polish on the games, but, especially with publishers being more demanding of what and how much goes out and overall just demands that everything explicitly always meet the exact deadline no exceptions or extensions... Yeah, I’m willing to be more forgiving about bugs.

Not because I think they should be given a pass, but because games are a major investment. And, especially with publishers like EA embracing the lootbox gambling model, being less forgiving of anything that’s not constantly generating more money for them, yeah, I’m willing to forgive the developers saying ‘this works enough for now, we’ll patch the rest of it after release, let’s get it out the door.’

I’ll put the problems of Andromeda on corporate mismanagement, of a smaller studio being in over their heads, but honestly? This should have been reason to CELEBRATE BioWare Montreal - not only did this small studio manage to put out this game that, if judged purely on its own merits, not in comparison to the trilogy (because holding one game up against three is NEVER fair under any circumstances - even holding it up against just ME1 is hard because we know where those plot threads lead to, we can’t fully distance ourselves from that fact)... It’s really not that bad. It’s got issues, it’s got flaws, the fact that it’s a b-team sequel is kinda obvious all the same... But they DID THIS. Against all odds, this tiny studio got this accomplished while pretty much having to build all the things they genuinely needed for this game on their own - Frostbite wasn’t BUILT for an RPG, it was built for a FPS. Even the problems, they sat down and were making efforts to fix it - they didn’t get to everything, but a majority of the major issues were addressed, down to Jaal being opened up as a romance option, something that resulted in the actors being brought back into the studio, and this was released as a PATCH, not DLC, like the Extended Cut for ME3.

And their reward was unending blame piled on unending blame followed by dissolution.

We should be looking at this as an underdog story, the deck stacked against BioWare Montreal, given a project too big for them, the Edmonton studio not able to provide aid, EA demanding more focus pulled over to Anthem at Andromeda’s expense, working with tools they had to stop and take time to build, and they still managed to put out this game AND try to shore up where it stumbled. Instead, so many people want to approach it as the death knell of Mass Effect as a franchise, BioWare as a studio, possibly even story-driven single player RPGs as a whole...

It’s ridiculous. And frankly, I think in a few years time, people are going to realize it. Hell, if Anthem crashes and burns (which, given the Battlefront release, and the fact that the EU managed to make the Pokemon games take out their gaming corners after Gen IV - Pokemon, one of the most popular video game franchises EVER, a behemoth if there ever was one, and that franchise was made to blink at the EU - and they’re the ones putting through an investigation about loot boxes as gambling... It’s entirely a valid possibility), assuming BioWare isn’t folded up out of existence, I think it’s reasonable to assume that people will return to Andromeda and say ‘this wasn’t so bad.’

Which is just gonna piss off those of us who have been saying so since it released.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Natalie Jones and the Golden Ship

Part 1/? - A Meeting at the Palace

Part 2/? - Curry Talk

Part 3/? - Princess Sitamun

Part 4/? - Not At Rest

Part 5/? - Dead Men Tell no Tales

Part 6/? - Sitamun Rises Again

Part 7/? - The Curse of Madame Desrosiers

Part 8/? - Sabotage at Guedelon

Part 9/? - A Miracle

Part 10/? - Desrosiers’ Elixir

Part 11/? - Athens in October

Part 12/? - The Man in Black

Part 13/? - Mr. Neustadt

Part 14/? - The Other Side of the Story

Part 15/? - A Favour

Part 16/? - A Knock on the Window

Nat and Sir Stephen follow Neustadt home in the hope of getting some clues.

Neustadt returned to the train station, and took transit southeast to the Neapoli district, an area of dense apartments and narrow streets below Mount Lycabettus. Natasha and Sir Stephen followed him, hiding behind newspapers or a group of young soccer fans, and watched as he descended a flight of steps from the sidewalk on Doxapatri to enter a building. Nat pulled her phone out, and made a note of their location, then sat down on the curb to wait.

“Are we not going inside?” asked Sir Stephen.

“We’re being spies, not warriors,” Nat told him. “We’ve learned everything we can from him verbally. Now we want to see what’s in his home. We’ll watch, and we’ll wait.”

So that was what they did – and about an hour later Neustadt reappeared, dressed in a suit and tie that must have been hideously hot, even now that the sun was down. A taxi pulled up, and he got in. It headed south, and vanished around the corner.

“All right,” said Nat. “Now we go in.”

Like every other space in Athens, the apartment foyer – small and dim, with the tile floor cracking – was tiny and cramped by the standards of somebody who’d lived and worked in America. Europe was a small continent, and people there didn’t feel the freedom Americans did to spread out and take up space. There were no plants or furniture, since there wouldn’t have been room for any, and an ‘out of order’ sign on the door of the elevator. The only person in the room was a nine-year-old girl sitting on the bottom step of the staircase, playing a hand-held video game.

“Good evening,” Natasha said to her in Greek. “Did you see the man in the suit who just left?”

The girl nodded.

“Does he live here?” Nat asked.

The girl just shrugged.

“Have you seen him before?” Nat insisted.

“Sometimes,” the girl said. “Not very often. He visits the apartment across from my mother’s.”

Nat managed to get from the girl that her family lived on the third floor, and then thanked her and gave her a couple of Euros to buy herself a treat. Since the elevator was out of order, Nat and Sir Stephen had to climb the stairs to the third floor, which was not in any way pleasant. By the time they got there, Nat’s hair was stuck to the back of her neck from sweat, and even Sir Stephen, who was normally almost immune to environmental discomfort, flapped the front of his shirt in the effort to cool himself.

The apartment the man was supposed to have visited turned out to be number 304. Natasha knocked on the door.

There was no answer.

Nat knocked again, counted to twenty just to be sure, and then pulled out a paperclip and bent it open to pick the lock. The apartment beyond was a surprise – it was empty.

It was a tiny place, just three rooms: a bathroom, a kitchen, and a bedroom. Each had a couple of items placed in front of the windows to make it look as if somebody lived there – some jars or books, curtains, or a framed painting on the wall opposite. Beyond that, however, there was nothing. No dishes in the kitchen cupboard, no food in the fridge, no towels in the bathroom. In the closet a few sets of clothing were hung, and the shorts and t-shirt Neustadt had been wearing earlier were folded on the floor next to his flip-flops. This wasn’t his home, just a convenient place to change clothes.

On an empty kitchen cupboard was a pink post-it note, on which somebody – presumably Neustadt himself – had written the words, one atop the other:

MISSED

ME

IN

“Missed me in Athens?” Sir Stephen suggested.

“Maybe,” said Nat. Although if so, why hadn’t he cut the message short? Had somebody interrupted him? He hadn’t looked like he was in a huge hurry when he’d caught his taxi. Nat reached up to take the note, then changed her mind and took a picture of it instead. “It’s not for us. We didn’t miss him,” she observed. “It’s for somebody else… maybe Desrosiers.”

“We did indeed miss him,” Sir Stephen said, annoyed. “In that you wouldn’t enter until he’d left. What shall spies do next, then?”

“Search the place again,” Nat decided. “And be very careful to put everything back exactly where you found it. Bang on the walls, stomp on the floors, look for secret cupboards or hidden spaces, anywhere you could store something you don’t want anyone to find. And then we wait, because if he left this note then he must be expecting somebody to come here. If it’s Desrosiers, we need to talk to her, too.”

They searched the apartment from top to bottom, and found nothing. Natasha knocked on the doors of 303 and 305, both of which were inhabited by apparently normal people: 303 was home to an old man who lived alone with a small terrier, and 305 to a family in which both parents worked while also raising four school-age children. Neither could remember ever speaking to their neighbor in 304 but they were sure somebody lived there – or at the very least watered the plants on the balcony.

Nat rejoined Sir Stephen in the bedroom, which did not contain a bed – just a small bookshelf and chair in a place where they would be visible through the window curtains. The books were a random assortment of trashy best-sellers from about ten years back, of no interest at all. She’d flipped through them, and they were all real books, rather than hiding places.

“This is just a front,” she said, sitting down on the floor beside Sir Stephen. “It’s a place he can hide and maybe get his mail delivered to, but I don’t think he spends any more time here than necessary. Possibly he used to store stuff here.” There wasn’t much dust on the floor, which suggested it had either been recently cleaned or recently covered. “If he did, he’s taken it away now.”

“So we have learned nothing,” groused Sir Stephen.

“We’ve learned a lot,” Nat told him. “We’ve definitely learned enough to pretend we know more than we do, and we might be able to use that to get something out of Desrosiers.”

“And what if we wait here all night and she never comes?” Sir Stephen asked. “We will have spent the night sitting around uselessly, while Neustadt flees!”

He might be right, but Nat wasn’t going to admit it as long as he was using that tone. “I’m going to call the others,” she decided.

Sharon answered the phone, and sounded relieved to hear from them. “Where are you two?” she asked. “We’ve been waiting at the hotel for hours.”

“We’re at an address in Neapoli,” said Nat. “I think Desrosiers may turn up here.” She explained what they’d seen, and how Neustadt had left. “Did you talk to Fury?”

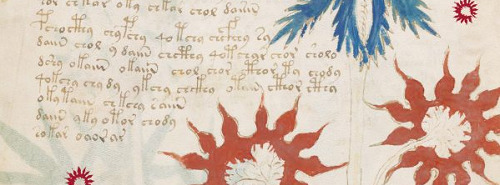

“Yes,” Sharon said. “He’s gonna see if he can get us a copy of the Voynich manuscript, although he’s not sure it’ll do us any good. The smartest cryptographers in the world have been trying to decode it for a hundred years, and nobody’s managed it yet.”

“I guess there might be something else in there we could use,” said Nat, although she wasn’t hopeful. It wasn’t just Americans who were interested in the manuscript – the Russians, too, had tested their best code-breakers on it and come up with nothing. “Anything else? What about the address in Australia? Or Kotor?”

“He’s going to call somebody in Australia to ask,” Sharon said, “but as far as we can tell from a quick check of Google Maps, it’s a shack in the middle of nowhere. As for Kotor, he says that’s a trap. I told him we know it’s a trap, we’re trying to figure out whether it’s worth springing it.”

“All right, let me know,” said Nat.

“One other thing,” Sharon added. “He says he’s got copies of those Newton writings, and he’ll courier them to us. We should expect the package at the hotel tomorrow morning.”

“Then call me when they get there,” Natasha said. “We’ll stay here, and if Desrosiers doesn’t turn up by the morning, we’ll come back.”

There was an air conditioner in the room, but it didn’t work. Nat and Sir Stephen, sitting in the middle of the bare floor, had to try to keep cool by fanning themselves with papers or their hands while they passed the time by playing a couple of games of Beat Your Neighbour. The cards were a pack bought from a souvenir vendor in the street – they had erotic scenes from ancient pottery on the backs, including a very improbable picture of a satyr balancing a cup of wine on its erect penis. Sir Stephen won both games, and then sat back and yawned.

“Sleepy?” asked Natasha.

“It’s this heat,” said Sir Stephen. “It makes one want to sleep at the same time as it is likely to render sleep impossible.”

“Having to sleep on the floor isn’t going to help,” Nat agreed. “So who takes first watch?” One of them would have to stay awake to see if Desrosiers, or somebody else, showed up. The question was who.

There was a rap on the window.

Nat jumped, and she could see that Sir Stephen did too. For a moment she thought it was intentional, then she remembered they were on the third floor… who’d be knocking on the window? Could it have been a bird? Then it happened again – three knocks. That was definitely somebody trying to get their attention.

She caught Sir Stephen’s eye. He took up a position next to the window, and picked up the wooden chair from under the bookshelf, to use as a weapon. Nat pulled the curtains back and raised her flashlight. There was a man on the balcony, blinking in the light and raising his hands to show that he was unarmed.

It was Jim, with his long hair and black t-shirt. He squinted to see who was holding the flashlight, then recognized her and looked surprised – had he, too, been expecting Neustadt? He knocked on the window again to be let in.

Nat undid the catch and let him inside.

“What are you doing here?” she asked.

“I’m not entirely sure,” Jim admitted. “I just knew this was the place to come.”

Maybe he’d been here before, and Neustadt had ordered him to forget about it, Nat thought. Or maybe he’d been told to come here but not why. Or maybe he did after all know more than what Neustadt had told him – maybe he’d somehow picked up some things Neustadt hadn’t meant to transmit.

“What do you want?” Nat asked. Behind her, Sir Stephen slowly set down the chair he was holding.

“I… I’m not sure of that, either,” Jim admitted. “I want help, but I don’t know if you can help me. I don’t know if anybody can help me – he says he can’t, but maybe Mrs. Flamel can… but I don’t know if she wants to.”

Nat had a good idea of what the problem might be, but she wanted to hear it from him. “Explain.”

4 notes

·

View notes